User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

Have you heard the one about the cow in the doctor’s office?

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Should you quit employment to open a practice? These docs share how they did it

“Everyone said private practice is dying,” said Omar Maniya, MD, an emergency physician who left his hospital job for family practice in New Jersey. “But I think it could be one of the best models we have to advance our health care system and prevent burnout – and bring joy back to the practice of medicine.”

But employment doesn’t necessarily mean happiness. In the Medscape “Employed Physicians: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy” ” report, more than 1,350 U.S. physicians employed by a health care organization, hospital, large group practice, or other medical group were surveyedabout their work. As the subtitle suggests, many are torn.

In the survey, employed doctors cited three main downsides to the lifestyle: They have less autonomy, more corporate rules than they’d like, and lower earning potential. Nearly one-third say they’re unhappy about their work-life balance, too, which raises the risk for burnout.

Some physicians find that employment has more cons than pros and turn to private practice instead.

A system skewed toward employment

In the mid-1990s, when James Milford, MD, completed his residency, going straight into private practice was the norm. The family physician bucked that trend by joining a large regional medical center in Wisconsin. He spent the next 20+ years working to establish a network of medical clinics.

“It was very satisfying,” Dr. Milford said. “When I started, I had a lot of input, a lot of control.”

Since then, the pendulum has been swinging toward employment. Brieanna Seefeldt, DO, a family physician outside Denver, completed her residency in 2012.

“I told the recruiter I wanted my own practice,” Dr. Seefeldt said, “They said if you’re not independently wealthy, there’s no way.”

Sonal G. Patel, MD, a pediatric neurologist in Bethesda, finished her residency the same year as Dr. Seefeldt. Dr. Patel never even considered private practice.

“I always thought I would have a certain amount of clinic time where I have my regular patients,” she said, “but I’d also be doing hospital rounds and reading EEG studies at the hospital.”

For Dr. Maniya, who completed his residency in 2021, the choice was simple. Growing up, he watched his immigrant parents, both doctors in private practice, struggle to keep up.

“I opted for a big, sophisticated health system,” he said. “I thought we’d be pushing the envelope of what was possible in medicine.”

Becoming disillusioned with employment

All four of these physicians are now in private practice and are much happier.

Within a few years of starting her job, Dr. Seefeldt was one of the top producers in her area but felt tremendous pressure to see more and more patients. The last straw came after an unpaid maternity leave.

“They told me I owed them for my maternity leave, for lack of productivity,” she said. “I was in practice for only 4 years, but already feeling the effects of burnout.”

Dr. Patel only lasted 2 years before realizing employment didn’t suit her.

“There was an excessive amount of hospital calls,” she said. “And there were bureaucratic issues that made it very difficult to practice the way I thought my practice would be.”

It took just 18 months for Dr. Maniya’s light-bulb moment. He was working at a hospital when COVID-19 hit.

“At my big health care system, it took 9 months to come up with a way to get COVID swabs for free,” he said. “At the same time, I was helping out the family business, a private practice. It took me two calls and 48 hours to get free swabs for not just the practice, not just our patients, but the entire city of Hamilton, New Jersey.”

Milford lasted the longest as an employee – nearly 25 years. The end came after a healthcare company with hospitals in 30 states bought out the medical center.

“My control gradually eroded,” he said. “It got to the point where I had no input regarding things like employees or processes we wanted to improve.”

Making the leap to private practice

Private practice can take different forms.

Dr. Seefeldt opted for direct primary care, a model in which her patients pay a set monthly fee for care whenever needed. Her practice doesn’t take any insurance besides Medicaid.

“Direct primary care is about working directly with the patient and cost-conscious, transparent care,” she said. “And I don’t have to deal with insurance.”

For Dr. Patel, working with an accountable care organization made the transition easier. She owns her practice solo but works with a company called Privia for administrative needs. Privia sent a consultant to set up her office in the company’s electronic medical record. Things were up and running within the first week.

Dr. Maniya joined his mother’s practice, easing his way in over 18 months.

And then there’s what Milford did, building a private practice from the ground up.

“We did a lot of Googling, a lot of meeting with accountants, meeting with small business development from the state of Wisconsin,” he said. “We asked people that were in business, ‘What are the things businesses fail on? Not medical practices, but businesses.’” All that research helped him launch successfully.

Making the dollars and cents add up

Moving from employment into private practice takes time, effort, and of course, money. How much of each varies depending on where you live, your specialty, whether you choose to rent or buy office space, staffing needs, and other factors.

Dr. Seefeldt, Dr. Patel, Dr. Milford, and Dr. Maniya illustrate the range.

- Dr. Seefeldt got a home equity loan of $50,000 to cover startup costs – and paid it back within 6 months.

- Purchasing EEG equipment added to Dr. Patel’s budget; she spent $130,000 of her own money to launch her practice in a temporary office and took out a $150,000 loan to finance the buildout of her final space. It took her 3 years to pay it back.

- When Dr. Milford left employment, he borrowed the buildout and startup costs for his practice from his father, a retired surgeon, to the tune of $500,000.

- Dr. Maniya assumed the largest risk. When he took over the family practice, he borrowed $1.5 million to modernize and build a new office. The practice has now quintupled in size. “It’s going great,” he said. “One of our questions is, should we pay back the loan at a faster pace rather than make the minimum payments?”

Several years in, Dr. Patel reports she’s easily making three to four times as much as she would have at a hospital. However, Dr. Maniya’s guaranteed compensation is 10% less than his old job.

“But as a partner in a private practice, if it succeeds, it could be 100%-150% more in a good year,” he said. On the flip side, if the practice runs into financial trouble, so does he. “Does the risk keep me up at night, give me heartburn? You betcha.”

Dr. Milford and Dr. Seefeldt have both chosen to take less compensation than they could, opting to reinvest in and nurture their practices.

“I love it,” said Dr. Milford. “I joke that I have half as much in my pocketbook, twice as much in my heart. But it’s not really half as much, 5 years in. If I weren’t growing the business, I’d be making more than before.”

Private practice is not without challenges

Being the big cheese does have drawbacks. In the current climate, staffing is a persistent issue for doctors in private practice – both maintaining a full staff and managing their employees.

And without the backing of a large corporation, doctors are sometimes called on to do less than pleasant tasks.

“If the toilet gets clogged and the plumber can’t come for a few hours, the patients still need a bathroom,” Dr. Maniya said. “I’ll go in with my $400 shoes and snake the toilet.”

Dr. Milford pointed out that when the buck stops with you, small mistakes can have enormous ramifications. “But with the bad comes the great potential for good. You have the ability to positively affect patients and healthcare, and to make a difference for people. It creates great personal satisfaction.”

Is running your own practice all it’s cracked up to be?

If it’s not yet apparent, all four doctors highly recommend moving from employment to private practice when possible. The autonomy and the improved work-life balance have helped them find the satisfaction they’d been missing while making burnout less likely.

“When you don’t have to spend 30% of your day apologizing to patients for how bad the health care system is, it reignites your passion for why you went into medicine in the first place,” said Dr. Maniya. In his practice, he’s made a conscious decision to pursue a mix of demographics. “Thirty percent of our patients are Medicaid. The vast majority are middle to low income.”

For physicians who are also parents, the ability to set their own schedules is life-changing.

“My son got an award ... and the teacher invited me to the assembly. In a corporate-based world, I’d struggle to be able to go,” said Dr. Seefeldt. As her own boss, she didn’t have to forgo this special event. Instead, she coordinated directly with her scheduled patient to make time for it.

In Medscape’s report, 61% of employed physicians indicated that they don’t have a say on key management decisions. However, doctors who launch private practices embrace the chance to set their own standards.

“We make sure from the minute someone calls they know they’re in good hands, we’re responsive, we address concerns right away. That’s the difference with private practice – the one-on-one connection is huge,” said Dr. Patel.

“This is exactly what I always wanted. It brings me joy knowing we’ve made a difference in these children’s lives, in their parents’ lives,” she concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Everyone said private practice is dying,” said Omar Maniya, MD, an emergency physician who left his hospital job for family practice in New Jersey. “But I think it could be one of the best models we have to advance our health care system and prevent burnout – and bring joy back to the practice of medicine.”

But employment doesn’t necessarily mean happiness. In the Medscape “Employed Physicians: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy” ” report, more than 1,350 U.S. physicians employed by a health care organization, hospital, large group practice, or other medical group were surveyedabout their work. As the subtitle suggests, many are torn.

In the survey, employed doctors cited three main downsides to the lifestyle: They have less autonomy, more corporate rules than they’d like, and lower earning potential. Nearly one-third say they’re unhappy about their work-life balance, too, which raises the risk for burnout.

Some physicians find that employment has more cons than pros and turn to private practice instead.

A system skewed toward employment

In the mid-1990s, when James Milford, MD, completed his residency, going straight into private practice was the norm. The family physician bucked that trend by joining a large regional medical center in Wisconsin. He spent the next 20+ years working to establish a network of medical clinics.

“It was very satisfying,” Dr. Milford said. “When I started, I had a lot of input, a lot of control.”

Since then, the pendulum has been swinging toward employment. Brieanna Seefeldt, DO, a family physician outside Denver, completed her residency in 2012.

“I told the recruiter I wanted my own practice,” Dr. Seefeldt said, “They said if you’re not independently wealthy, there’s no way.”

Sonal G. Patel, MD, a pediatric neurologist in Bethesda, finished her residency the same year as Dr. Seefeldt. Dr. Patel never even considered private practice.

“I always thought I would have a certain amount of clinic time where I have my regular patients,” she said, “but I’d also be doing hospital rounds and reading EEG studies at the hospital.”

For Dr. Maniya, who completed his residency in 2021, the choice was simple. Growing up, he watched his immigrant parents, both doctors in private practice, struggle to keep up.

“I opted for a big, sophisticated health system,” he said. “I thought we’d be pushing the envelope of what was possible in medicine.”

Becoming disillusioned with employment

All four of these physicians are now in private practice and are much happier.

Within a few years of starting her job, Dr. Seefeldt was one of the top producers in her area but felt tremendous pressure to see more and more patients. The last straw came after an unpaid maternity leave.

“They told me I owed them for my maternity leave, for lack of productivity,” she said. “I was in practice for only 4 years, but already feeling the effects of burnout.”

Dr. Patel only lasted 2 years before realizing employment didn’t suit her.

“There was an excessive amount of hospital calls,” she said. “And there were bureaucratic issues that made it very difficult to practice the way I thought my practice would be.”

It took just 18 months for Dr. Maniya’s light-bulb moment. He was working at a hospital when COVID-19 hit.

“At my big health care system, it took 9 months to come up with a way to get COVID swabs for free,” he said. “At the same time, I was helping out the family business, a private practice. It took me two calls and 48 hours to get free swabs for not just the practice, not just our patients, but the entire city of Hamilton, New Jersey.”

Milford lasted the longest as an employee – nearly 25 years. The end came after a healthcare company with hospitals in 30 states bought out the medical center.

“My control gradually eroded,” he said. “It got to the point where I had no input regarding things like employees or processes we wanted to improve.”

Making the leap to private practice

Private practice can take different forms.

Dr. Seefeldt opted for direct primary care, a model in which her patients pay a set monthly fee for care whenever needed. Her practice doesn’t take any insurance besides Medicaid.

“Direct primary care is about working directly with the patient and cost-conscious, transparent care,” she said. “And I don’t have to deal with insurance.”

For Dr. Patel, working with an accountable care organization made the transition easier. She owns her practice solo but works with a company called Privia for administrative needs. Privia sent a consultant to set up her office in the company’s electronic medical record. Things were up and running within the first week.

Dr. Maniya joined his mother’s practice, easing his way in over 18 months.

And then there’s what Milford did, building a private practice from the ground up.

“We did a lot of Googling, a lot of meeting with accountants, meeting with small business development from the state of Wisconsin,” he said. “We asked people that were in business, ‘What are the things businesses fail on? Not medical practices, but businesses.’” All that research helped him launch successfully.

Making the dollars and cents add up

Moving from employment into private practice takes time, effort, and of course, money. How much of each varies depending on where you live, your specialty, whether you choose to rent or buy office space, staffing needs, and other factors.

Dr. Seefeldt, Dr. Patel, Dr. Milford, and Dr. Maniya illustrate the range.

- Dr. Seefeldt got a home equity loan of $50,000 to cover startup costs – and paid it back within 6 months.

- Purchasing EEG equipment added to Dr. Patel’s budget; she spent $130,000 of her own money to launch her practice in a temporary office and took out a $150,000 loan to finance the buildout of her final space. It took her 3 years to pay it back.

- When Dr. Milford left employment, he borrowed the buildout and startup costs for his practice from his father, a retired surgeon, to the tune of $500,000.

- Dr. Maniya assumed the largest risk. When he took over the family practice, he borrowed $1.5 million to modernize and build a new office. The practice has now quintupled in size. “It’s going great,” he said. “One of our questions is, should we pay back the loan at a faster pace rather than make the minimum payments?”

Several years in, Dr. Patel reports she’s easily making three to four times as much as she would have at a hospital. However, Dr. Maniya’s guaranteed compensation is 10% less than his old job.

“But as a partner in a private practice, if it succeeds, it could be 100%-150% more in a good year,” he said. On the flip side, if the practice runs into financial trouble, so does he. “Does the risk keep me up at night, give me heartburn? You betcha.”

Dr. Milford and Dr. Seefeldt have both chosen to take less compensation than they could, opting to reinvest in and nurture their practices.

“I love it,” said Dr. Milford. “I joke that I have half as much in my pocketbook, twice as much in my heart. But it’s not really half as much, 5 years in. If I weren’t growing the business, I’d be making more than before.”

Private practice is not without challenges

Being the big cheese does have drawbacks. In the current climate, staffing is a persistent issue for doctors in private practice – both maintaining a full staff and managing their employees.

And without the backing of a large corporation, doctors are sometimes called on to do less than pleasant tasks.

“If the toilet gets clogged and the plumber can’t come for a few hours, the patients still need a bathroom,” Dr. Maniya said. “I’ll go in with my $400 shoes and snake the toilet.”

Dr. Milford pointed out that when the buck stops with you, small mistakes can have enormous ramifications. “But with the bad comes the great potential for good. You have the ability to positively affect patients and healthcare, and to make a difference for people. It creates great personal satisfaction.”

Is running your own practice all it’s cracked up to be?

If it’s not yet apparent, all four doctors highly recommend moving from employment to private practice when possible. The autonomy and the improved work-life balance have helped them find the satisfaction they’d been missing while making burnout less likely.

“When you don’t have to spend 30% of your day apologizing to patients for how bad the health care system is, it reignites your passion for why you went into medicine in the first place,” said Dr. Maniya. In his practice, he’s made a conscious decision to pursue a mix of demographics. “Thirty percent of our patients are Medicaid. The vast majority are middle to low income.”

For physicians who are also parents, the ability to set their own schedules is life-changing.

“My son got an award ... and the teacher invited me to the assembly. In a corporate-based world, I’d struggle to be able to go,” said Dr. Seefeldt. As her own boss, she didn’t have to forgo this special event. Instead, she coordinated directly with her scheduled patient to make time for it.

In Medscape’s report, 61% of employed physicians indicated that they don’t have a say on key management decisions. However, doctors who launch private practices embrace the chance to set their own standards.

“We make sure from the minute someone calls they know they’re in good hands, we’re responsive, we address concerns right away. That’s the difference with private practice – the one-on-one connection is huge,” said Dr. Patel.

“This is exactly what I always wanted. It brings me joy knowing we’ve made a difference in these children’s lives, in their parents’ lives,” she concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Everyone said private practice is dying,” said Omar Maniya, MD, an emergency physician who left his hospital job for family practice in New Jersey. “But I think it could be one of the best models we have to advance our health care system and prevent burnout – and bring joy back to the practice of medicine.”

But employment doesn’t necessarily mean happiness. In the Medscape “Employed Physicians: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy” ” report, more than 1,350 U.S. physicians employed by a health care organization, hospital, large group practice, or other medical group were surveyedabout their work. As the subtitle suggests, many are torn.

In the survey, employed doctors cited three main downsides to the lifestyle: They have less autonomy, more corporate rules than they’d like, and lower earning potential. Nearly one-third say they’re unhappy about their work-life balance, too, which raises the risk for burnout.

Some physicians find that employment has more cons than pros and turn to private practice instead.

A system skewed toward employment

In the mid-1990s, when James Milford, MD, completed his residency, going straight into private practice was the norm. The family physician bucked that trend by joining a large regional medical center in Wisconsin. He spent the next 20+ years working to establish a network of medical clinics.

“It was very satisfying,” Dr. Milford said. “When I started, I had a lot of input, a lot of control.”

Since then, the pendulum has been swinging toward employment. Brieanna Seefeldt, DO, a family physician outside Denver, completed her residency in 2012.

“I told the recruiter I wanted my own practice,” Dr. Seefeldt said, “They said if you’re not independently wealthy, there’s no way.”

Sonal G. Patel, MD, a pediatric neurologist in Bethesda, finished her residency the same year as Dr. Seefeldt. Dr. Patel never even considered private practice.

“I always thought I would have a certain amount of clinic time where I have my regular patients,” she said, “but I’d also be doing hospital rounds and reading EEG studies at the hospital.”

For Dr. Maniya, who completed his residency in 2021, the choice was simple. Growing up, he watched his immigrant parents, both doctors in private practice, struggle to keep up.

“I opted for a big, sophisticated health system,” he said. “I thought we’d be pushing the envelope of what was possible in medicine.”

Becoming disillusioned with employment

All four of these physicians are now in private practice and are much happier.

Within a few years of starting her job, Dr. Seefeldt was one of the top producers in her area but felt tremendous pressure to see more and more patients. The last straw came after an unpaid maternity leave.

“They told me I owed them for my maternity leave, for lack of productivity,” she said. “I was in practice for only 4 years, but already feeling the effects of burnout.”

Dr. Patel only lasted 2 years before realizing employment didn’t suit her.

“There was an excessive amount of hospital calls,” she said. “And there were bureaucratic issues that made it very difficult to practice the way I thought my practice would be.”

It took just 18 months for Dr. Maniya’s light-bulb moment. He was working at a hospital when COVID-19 hit.

“At my big health care system, it took 9 months to come up with a way to get COVID swabs for free,” he said. “At the same time, I was helping out the family business, a private practice. It took me two calls and 48 hours to get free swabs for not just the practice, not just our patients, but the entire city of Hamilton, New Jersey.”

Milford lasted the longest as an employee – nearly 25 years. The end came after a healthcare company with hospitals in 30 states bought out the medical center.

“My control gradually eroded,” he said. “It got to the point where I had no input regarding things like employees or processes we wanted to improve.”

Making the leap to private practice

Private practice can take different forms.

Dr. Seefeldt opted for direct primary care, a model in which her patients pay a set monthly fee for care whenever needed. Her practice doesn’t take any insurance besides Medicaid.

“Direct primary care is about working directly with the patient and cost-conscious, transparent care,” she said. “And I don’t have to deal with insurance.”

For Dr. Patel, working with an accountable care organization made the transition easier. She owns her practice solo but works with a company called Privia for administrative needs. Privia sent a consultant to set up her office in the company’s electronic medical record. Things were up and running within the first week.

Dr. Maniya joined his mother’s practice, easing his way in over 18 months.

And then there’s what Milford did, building a private practice from the ground up.

“We did a lot of Googling, a lot of meeting with accountants, meeting with small business development from the state of Wisconsin,” he said. “We asked people that were in business, ‘What are the things businesses fail on? Not medical practices, but businesses.’” All that research helped him launch successfully.

Making the dollars and cents add up

Moving from employment into private practice takes time, effort, and of course, money. How much of each varies depending on where you live, your specialty, whether you choose to rent or buy office space, staffing needs, and other factors.

Dr. Seefeldt, Dr. Patel, Dr. Milford, and Dr. Maniya illustrate the range.

- Dr. Seefeldt got a home equity loan of $50,000 to cover startup costs – and paid it back within 6 months.

- Purchasing EEG equipment added to Dr. Patel’s budget; she spent $130,000 of her own money to launch her practice in a temporary office and took out a $150,000 loan to finance the buildout of her final space. It took her 3 years to pay it back.

- When Dr. Milford left employment, he borrowed the buildout and startup costs for his practice from his father, a retired surgeon, to the tune of $500,000.

- Dr. Maniya assumed the largest risk. When he took over the family practice, he borrowed $1.5 million to modernize and build a new office. The practice has now quintupled in size. “It’s going great,” he said. “One of our questions is, should we pay back the loan at a faster pace rather than make the minimum payments?”

Several years in, Dr. Patel reports she’s easily making three to four times as much as she would have at a hospital. However, Dr. Maniya’s guaranteed compensation is 10% less than his old job.

“But as a partner in a private practice, if it succeeds, it could be 100%-150% more in a good year,” he said. On the flip side, if the practice runs into financial trouble, so does he. “Does the risk keep me up at night, give me heartburn? You betcha.”

Dr. Milford and Dr. Seefeldt have both chosen to take less compensation than they could, opting to reinvest in and nurture their practices.

“I love it,” said Dr. Milford. “I joke that I have half as much in my pocketbook, twice as much in my heart. But it’s not really half as much, 5 years in. If I weren’t growing the business, I’d be making more than before.”

Private practice is not without challenges

Being the big cheese does have drawbacks. In the current climate, staffing is a persistent issue for doctors in private practice – both maintaining a full staff and managing their employees.

And without the backing of a large corporation, doctors are sometimes called on to do less than pleasant tasks.

“If the toilet gets clogged and the plumber can’t come for a few hours, the patients still need a bathroom,” Dr. Maniya said. “I’ll go in with my $400 shoes and snake the toilet.”

Dr. Milford pointed out that when the buck stops with you, small mistakes can have enormous ramifications. “But with the bad comes the great potential for good. You have the ability to positively affect patients and healthcare, and to make a difference for people. It creates great personal satisfaction.”

Is running your own practice all it’s cracked up to be?

If it’s not yet apparent, all four doctors highly recommend moving from employment to private practice when possible. The autonomy and the improved work-life balance have helped them find the satisfaction they’d been missing while making burnout less likely.

“When you don’t have to spend 30% of your day apologizing to patients for how bad the health care system is, it reignites your passion for why you went into medicine in the first place,” said Dr. Maniya. In his practice, he’s made a conscious decision to pursue a mix of demographics. “Thirty percent of our patients are Medicaid. The vast majority are middle to low income.”

For physicians who are also parents, the ability to set their own schedules is life-changing.

“My son got an award ... and the teacher invited me to the assembly. In a corporate-based world, I’d struggle to be able to go,” said Dr. Seefeldt. As her own boss, she didn’t have to forgo this special event. Instead, she coordinated directly with her scheduled patient to make time for it.

In Medscape’s report, 61% of employed physicians indicated that they don’t have a say on key management decisions. However, doctors who launch private practices embrace the chance to set their own standards.

“We make sure from the minute someone calls they know they’re in good hands, we’re responsive, we address concerns right away. That’s the difference with private practice – the one-on-one connection is huge,” said Dr. Patel.

“This is exactly what I always wanted. It brings me joy knowing we’ve made a difference in these children’s lives, in their parents’ lives,” she concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 17-year-old male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a year-long rash

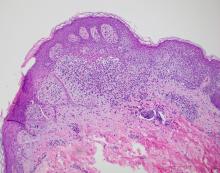

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A 17-year-old healthy male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a rash on the skin which has been present on and off for a year. During the initial presentation, the lesions were clustered on the back, were slightly itchy, and resolved after 3 months. Several new lesions have developed on the neck, torso, and extremities, leaving hypopigmented marks on the skin. He has previously been treated with topical antifungal creams, oral fluconazole, and triamcinolone ointment without resolution of the lesions.

He is not involved in any contact sports, he has not traveled outside the country, and is not taking any other medications. He is not sexually active. He also has a diagnosis of mild acne that he is currently treating with over-the-counter medications.

On physical exam he had several annular plaques with central atrophic centers and no scale. He also had some hypo- and hyperpigmented macules at the sites of prior skin lesions

Cardiologist sues hospital, claims he was fired in retaliation

alleging that he was fired and maligned after raising concerns about poorly performed surgeries and poor ethical practices at the hospital.

Dr. Zelman, from Barnstable, Mass., has been affiliated with Cape Cod Hospital in Hyannis, Mass., for more than 30 years. He helped found the hospital’s Heart and Vascular Institute and has served as its medical director since 2018.

In his lawsuit filed Dec. 6, Dr. Zelman alleges that the defendants, under Mr. Lauf’s leadership, “placed profit above all else, including by prioritizing revenue generation over patient safety and public health.”

Dr. Zelman says the defendants supported him “to the extent his actions were profitable.”

Yet, when he raised patient safety concerns that harmed that bottom line, Dr. Zelman says the defendants retaliated against him, including by threatening his career and reputation and unlawfully terminating his employment with the hospital.

The complaint notes Dr. Zelman is bringing this action “to recover damages for violations of the Massachusetts Healthcare Provider Whistleblower Statute ... as well as for breach of contract and common law claims.”

Dr. Zelman’s complaint alleges the defendants refused to adequately address the “dangerous care and violations of the professional standards of practice” that he reported, “resulting in harmful and tragic consequences.”

It also alleges Mr. Lauf restricted the use of a cerebral protection device used in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR) deemed to be at high risk for periprocedural stroke to only those patients whose insurance reimbursed at higher rates.

Dr. Zelman says he objected to this prohibition “in accordance with his contractual and ethical obligations to ensure treatment of patients without regard to their ability to pay.”

Dr. Zelman’s lawsuit further alleges that Mr. Lauf launched a “trumped-up” and “baseless, biased, and retaliatory sham” investigation against him.

In a statement sent to the Boston Globe, Cape Cod Hospital denied Dr. Zelman’s claims that the cardiologist was retaliated against for raising patient safety issues, or that the hospital didn’t take action to improve cardiac care at the facility.

Voiced concerns

In a statement sent to this news organization, Dr. Zelman, now in private practice, said, “Over the past 25 years, I have been instrumental in bringing advanced cardiac care to Cape Cod. My commitment has always been to delivering the same quality outcomes and safety as the academic centers in Boston.

“Unfortunately, over the past 5 years, there has been inadequate oversight by the hospital administration and problems have occurred that in my opinion have led to serious patient consequences,” Dr. Zelman stated.

He said he has “voiced concerns over several years and they have been ignored.”

He added that Cape Cod Hospital offered him a million-dollar contract as long as he agreed to immediately issue a written statement endorsing the quality and safety of the cardiac surgical program that no longer exists.

“No amount of money was going to buy my silence,” Dr. Zelman told this news organization.

In his lawsuit, Dr. Zelman is seeking an undisclosed amount in damages, including back and front pay, lost benefits, physical and emotional distress, and attorneys’ fees.

This news organization reached out to Cape Cod Hospital for comment but has not yet received a response.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

alleging that he was fired and maligned after raising concerns about poorly performed surgeries and poor ethical practices at the hospital.

Dr. Zelman, from Barnstable, Mass., has been affiliated with Cape Cod Hospital in Hyannis, Mass., for more than 30 years. He helped found the hospital’s Heart and Vascular Institute and has served as its medical director since 2018.

In his lawsuit filed Dec. 6, Dr. Zelman alleges that the defendants, under Mr. Lauf’s leadership, “placed profit above all else, including by prioritizing revenue generation over patient safety and public health.”

Dr. Zelman says the defendants supported him “to the extent his actions were profitable.”

Yet, when he raised patient safety concerns that harmed that bottom line, Dr. Zelman says the defendants retaliated against him, including by threatening his career and reputation and unlawfully terminating his employment with the hospital.

The complaint notes Dr. Zelman is bringing this action “to recover damages for violations of the Massachusetts Healthcare Provider Whistleblower Statute ... as well as for breach of contract and common law claims.”

Dr. Zelman’s complaint alleges the defendants refused to adequately address the “dangerous care and violations of the professional standards of practice” that he reported, “resulting in harmful and tragic consequences.”

It also alleges Mr. Lauf restricted the use of a cerebral protection device used in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR) deemed to be at high risk for periprocedural stroke to only those patients whose insurance reimbursed at higher rates.

Dr. Zelman says he objected to this prohibition “in accordance with his contractual and ethical obligations to ensure treatment of patients without regard to their ability to pay.”

Dr. Zelman’s lawsuit further alleges that Mr. Lauf launched a “trumped-up” and “baseless, biased, and retaliatory sham” investigation against him.

In a statement sent to the Boston Globe, Cape Cod Hospital denied Dr. Zelman’s claims that the cardiologist was retaliated against for raising patient safety issues, or that the hospital didn’t take action to improve cardiac care at the facility.

Voiced concerns

In a statement sent to this news organization, Dr. Zelman, now in private practice, said, “Over the past 25 years, I have been instrumental in bringing advanced cardiac care to Cape Cod. My commitment has always been to delivering the same quality outcomes and safety as the academic centers in Boston.

“Unfortunately, over the past 5 years, there has been inadequate oversight by the hospital administration and problems have occurred that in my opinion have led to serious patient consequences,” Dr. Zelman stated.

He said he has “voiced concerns over several years and they have been ignored.”

He added that Cape Cod Hospital offered him a million-dollar contract as long as he agreed to immediately issue a written statement endorsing the quality and safety of the cardiac surgical program that no longer exists.

“No amount of money was going to buy my silence,” Dr. Zelman told this news organization.

In his lawsuit, Dr. Zelman is seeking an undisclosed amount in damages, including back and front pay, lost benefits, physical and emotional distress, and attorneys’ fees.

This news organization reached out to Cape Cod Hospital for comment but has not yet received a response.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

alleging that he was fired and maligned after raising concerns about poorly performed surgeries and poor ethical practices at the hospital.

Dr. Zelman, from Barnstable, Mass., has been affiliated with Cape Cod Hospital in Hyannis, Mass., for more than 30 years. He helped found the hospital’s Heart and Vascular Institute and has served as its medical director since 2018.

In his lawsuit filed Dec. 6, Dr. Zelman alleges that the defendants, under Mr. Lauf’s leadership, “placed profit above all else, including by prioritizing revenue generation over patient safety and public health.”

Dr. Zelman says the defendants supported him “to the extent his actions were profitable.”

Yet, when he raised patient safety concerns that harmed that bottom line, Dr. Zelman says the defendants retaliated against him, including by threatening his career and reputation and unlawfully terminating his employment with the hospital.

The complaint notes Dr. Zelman is bringing this action “to recover damages for violations of the Massachusetts Healthcare Provider Whistleblower Statute ... as well as for breach of contract and common law claims.”

Dr. Zelman’s complaint alleges the defendants refused to adequately address the “dangerous care and violations of the professional standards of practice” that he reported, “resulting in harmful and tragic consequences.”

It also alleges Mr. Lauf restricted the use of a cerebral protection device used in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR) deemed to be at high risk for periprocedural stroke to only those patients whose insurance reimbursed at higher rates.

Dr. Zelman says he objected to this prohibition “in accordance with his contractual and ethical obligations to ensure treatment of patients without regard to their ability to pay.”

Dr. Zelman’s lawsuit further alleges that Mr. Lauf launched a “trumped-up” and “baseless, biased, and retaliatory sham” investigation against him.

In a statement sent to the Boston Globe, Cape Cod Hospital denied Dr. Zelman’s claims that the cardiologist was retaliated against for raising patient safety issues, or that the hospital didn’t take action to improve cardiac care at the facility.

Voiced concerns

In a statement sent to this news organization, Dr. Zelman, now in private practice, said, “Over the past 25 years, I have been instrumental in bringing advanced cardiac care to Cape Cod. My commitment has always been to delivering the same quality outcomes and safety as the academic centers in Boston.

“Unfortunately, over the past 5 years, there has been inadequate oversight by the hospital administration and problems have occurred that in my opinion have led to serious patient consequences,” Dr. Zelman stated.

He said he has “voiced concerns over several years and they have been ignored.”

He added that Cape Cod Hospital offered him a million-dollar contract as long as he agreed to immediately issue a written statement endorsing the quality and safety of the cardiac surgical program that no longer exists.

“No amount of money was going to buy my silence,” Dr. Zelman told this news organization.

In his lawsuit, Dr. Zelman is seeking an undisclosed amount in damages, including back and front pay, lost benefits, physical and emotional distress, and attorneys’ fees.

This news organization reached out to Cape Cod Hospital for comment but has not yet received a response.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why doctors are losing trust in patients; what should be done?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?

I think we have to really start to push administrators and people in positions of power to teach doctors and nurses how to defuse situations and how to make people more comfortable when they come in and the doctor suspects that they might be under the influence, impaired, or angry because of things they’ve seen on social media, whatever those might be – including concerns about racism, bigotry, and bias, which some patients are bringing into the clinic and the hospital setting.

We need more training. We’ve got to address this as a serious issue. What can we do to defuse situations where the doctor or the nurse rightly thinks that they can’t control or they can’t trust what the patient is thinking or how the patient might behave?

It’s also the case that I think we need more backup and quick access to security so that people feel safe and comfortable in providing care. We have to make sure that if you need someone to restrain a patient or to get somebody out of a situation, that they can get there quickly and respond rapidly, and that they know what to do to deescalate a situation.

It’s sad to say, but security in today’s health care world has to be something that we really test and check – not because we’re worried, as many places are, about a shooter entering the premises, which is its own bit of concern – but I’m just talking about when the doctor or the nurse says that this patient might be acting up, could get violent, or is someone I can’t trust.

My coauthors are basically saying that it’s not a one-way street. Yes, we have to figure out ways to make sure that our patients can trust what we say. Trust is absolutely the lubricant that makes health care flow. If patients don’t trust their doctors, they’re not going to do what they say. They’re not going to get their prescriptions filled. They’re not going to be compliant. They’re not going to try to lose weight or control their diabetes.

It also goes the other way. The doctor or the nurse has to trust the patient. They have to believe that they’re safe. They have to believe that the patient is capable of controlling themselves. They have to believe that the patient is capable of listening and hearing what they’re saying, and that they’re competent to follow up on instructions, including to come back if that’s what’s required.

Everybody has to feel secure in the environment in which they’re working. Security, sadly, has to be a priority if we’re going to have a health care workforce that really feels safe and comfortable dealing with a patient population that is increasingly aggressive and perhaps not as trustworthy.

That’s not news I like to read when my colleagues write it up, but it’s important and we have to take it seriously.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?