User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

COVID cases rising in about half of states

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Study: Physical fitness in children linked with concentration, quality of life

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.

“I think the authors of this study attempted to ask an important question about the possible association between physical fitness and concentration among school aged children,” Dr. Weaver said in an interview. “But what is even more vital are studies demonstrating that a change in modifiable health factors like nutrition, physical fitness, or the built environment can improve quality of life. I was hoping the authors would show that an improvement in VO2max over time resulted in an improvement in concentration. Frustratingly, that is not what this article demonstrates.”

The investigators and Dr. Weaver reported no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.

“I think the authors of this study attempted to ask an important question about the possible association between physical fitness and concentration among school aged children,” Dr. Weaver said in an interview. “But what is even more vital are studies demonstrating that a change in modifiable health factors like nutrition, physical fitness, or the built environment can improve quality of life. I was hoping the authors would show that an improvement in VO2max over time resulted in an improvement in concentration. Frustratingly, that is not what this article demonstrates.”

The investigators and Dr. Weaver reported no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.

“I think the authors of this study attempted to ask an important question about the possible association between physical fitness and concentration among school aged children,” Dr. Weaver said in an interview. “But what is even more vital are studies demonstrating that a change in modifiable health factors like nutrition, physical fitness, or the built environment can improve quality of life. I was hoping the authors would show that an improvement in VO2max over time resulted in an improvement in concentration. Frustratingly, that is not what this article demonstrates.”

The investigators and Dr. Weaver reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MEDICINE

Surgeons in China ‘are the executioners,’ procuring organs before brain death

In a deep dive into obscure Chinese language transplant journals, a pair of researchers from Australia and Israel have added a new layer of horror to what’s already known about forced organ harvesting in China.

Searching for documentation that vital organs are being harvested from nonconsenting executed prisoners, a practice that the China Tribunal confirmed “beyond any reasonable doubt” in 2020, Jacob Lavee, MD, an Israeli heart transplant surgeon, and Matthew Roberston, a PhD student at Australian National University, uncovered something even more shocking: that vital organs are being explanted from patients who are still alive.

“We have shown for the first time that the transplant surgeons are the executioners – that the mode of execution is organ procurement. These are self-admissions of executing the patient,” Dr. Lavee told this news organization. “Up until now, there has been what we call circumstantial evidence of this, but our paper is what you’d call the smoking gun, because it’s in the words of the physicians themselves that they are doing it. In the words of these surgeons, intubation was done only after the beginning of surgery, which means the patients were breathing spontaneously up until the moment the operation started ... meaning they were not brain dead.”

The research, published in the American Journal of Transplantation, involved intricate analysis of thousands of Chinese language transplant articles and identified 71 articles in which transplant surgeons describe starting organ procurement surgery before declaring their patients brain dead.

“What we found were improper, illegitimate, nonexistent, or false declarations of brain death,” Mr. Robertson said in an interview. He explained that this violates what’s known as the dead donor rule, which is fundamental in transplant ethics. “The surgeons wrote that the donor was brain dead, but according to everything we know about medical science, they could not possibly have been brain dead because there was no apnea test performed. Brain death is not just something you say, there’s this whole battery of tests, and the key is the apnea test, [in which] the patient is already intubated and ventilated, they turn the machine off, and they’re looking for carbon dioxide in the blood above a certain level.”

Mr. Robertson and Dr. Lavee have painstakingly documented “incriminating sentences” in each of the 71 articles proving that brain death had not occurred before the organ explantation procedure began. “There were two criteria by which we claimed a problematic brain death declaration,” said Mr. Robertson, who translated the Chinese. “One was where the patient was not ventilated and was only intubated after they were declared brain dead; the other was that the intubation took place immediately prior to the surgery beginning.”

“It was mind-boggling,” said Dr. Lavee, from Tel Aviv University. “When I first started reading, my initial reaction is, ‘This can’t be.’ I read it once, and again, and I insisted that Matt get another independent translation of the Chinese just to be sure. I told him, ‘There’s no way a physician, a surgeon could write this – it doesn’t make sense.’ But the more of these papers we read, we saw it was a pattern – and they didn’t come out of a single medical center, they are spread all over China.”

For the analysis, Mr. Robertson wrote code and customized an algorithm to examine 124,770 medical articles from official Chinese databases between 1980 and 2020. The 71 articles revealing cases involving problematic brain death came from 56 hospitals (of which 12 were military) in 33 cities across 15 provinces, they report. In total, 348 surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, and other medical workers or researchers were listed as authors of these publications.

Why would these medical personnel write such self-incriminating evidence? The researchers say it’s unclear. “They don’t think anyone’s reading this stuff,” Mr. Robertson suggests. “Sometimes it’s revealed in just five or six characters in a paper of eight pages.” Dr. Lavee wonders if it’s also ignorance. “If this has been a practice for 20 or 30 years in China, I guess nobody at that time was aware they were doing something wrong, although how to declare brain death is something that is known in China. They’ve published a lot about it.”

The article is “evidence that this barbarity continues and is a very valuable contribution that continues to bring attention to an enormous human rights violation,” said Arthur Caplan, PhD, head of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine. “What they’ve reported has been going on for many, many years, the data are very clear that China’s doing many more transplants than they have cadaver organ donors,” he said, adding that the country’s well-documented and lucrative involvement in transplant tourism “means you have to have a donor ready when the would-be recipient appears; you have to have a matched organ available, and that’s hard to do waiting on a cadaver donor.”

Although the researchers found no incriminating publications after 2015, they speculate that this is likely due to growing awareness among Chinese surgeons that publishing the information would attract international condemnation. “We think these practices are continuing to go on,” said Dr. Lavee. He acknowledged that a voluntary organ donation program is slowly developing in parallel to this. He said, given China’s place as the world’s second largest transplant country behind the U.S., as well as its low rate of voluntary donation, it’s reasonable to conclude that the main source of organs remains prisoners on death row.

Dr. Caplan and the researchers have called for academic institutions and medical journals to resume their previous boycotts of Chinese transplant publications and speakers, but as long as China denies the practices, economic and political leaders will turn a blind eye. “In the past, I don’t think the question of China’s medical professional involvement in the execution of donors has been taken as seriously as it should have,” said Mr. Robertson. “I certainly hope that with the publication of this paper in the leading journal in the field, this will change.”

The study was supported by the Google Cloud Research Credits program, the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. Mr. Robertson, Dr. Lavee, and Dr. Caplan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a deep dive into obscure Chinese language transplant journals, a pair of researchers from Australia and Israel have added a new layer of horror to what’s already known about forced organ harvesting in China.

Searching for documentation that vital organs are being harvested from nonconsenting executed prisoners, a practice that the China Tribunal confirmed “beyond any reasonable doubt” in 2020, Jacob Lavee, MD, an Israeli heart transplant surgeon, and Matthew Roberston, a PhD student at Australian National University, uncovered something even more shocking: that vital organs are being explanted from patients who are still alive.

“We have shown for the first time that the transplant surgeons are the executioners – that the mode of execution is organ procurement. These are self-admissions of executing the patient,” Dr. Lavee told this news organization. “Up until now, there has been what we call circumstantial evidence of this, but our paper is what you’d call the smoking gun, because it’s in the words of the physicians themselves that they are doing it. In the words of these surgeons, intubation was done only after the beginning of surgery, which means the patients were breathing spontaneously up until the moment the operation started ... meaning they were not brain dead.”

The research, published in the American Journal of Transplantation, involved intricate analysis of thousands of Chinese language transplant articles and identified 71 articles in which transplant surgeons describe starting organ procurement surgery before declaring their patients brain dead.

“What we found were improper, illegitimate, nonexistent, or false declarations of brain death,” Mr. Robertson said in an interview. He explained that this violates what’s known as the dead donor rule, which is fundamental in transplant ethics. “The surgeons wrote that the donor was brain dead, but according to everything we know about medical science, they could not possibly have been brain dead because there was no apnea test performed. Brain death is not just something you say, there’s this whole battery of tests, and the key is the apnea test, [in which] the patient is already intubated and ventilated, they turn the machine off, and they’re looking for carbon dioxide in the blood above a certain level.”

Mr. Robertson and Dr. Lavee have painstakingly documented “incriminating sentences” in each of the 71 articles proving that brain death had not occurred before the organ explantation procedure began. “There were two criteria by which we claimed a problematic brain death declaration,” said Mr. Robertson, who translated the Chinese. “One was where the patient was not ventilated and was only intubated after they were declared brain dead; the other was that the intubation took place immediately prior to the surgery beginning.”

“It was mind-boggling,” said Dr. Lavee, from Tel Aviv University. “When I first started reading, my initial reaction is, ‘This can’t be.’ I read it once, and again, and I insisted that Matt get another independent translation of the Chinese just to be sure. I told him, ‘There’s no way a physician, a surgeon could write this – it doesn’t make sense.’ But the more of these papers we read, we saw it was a pattern – and they didn’t come out of a single medical center, they are spread all over China.”

For the analysis, Mr. Robertson wrote code and customized an algorithm to examine 124,770 medical articles from official Chinese databases between 1980 and 2020. The 71 articles revealing cases involving problematic brain death came from 56 hospitals (of which 12 were military) in 33 cities across 15 provinces, they report. In total, 348 surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, and other medical workers or researchers were listed as authors of these publications.

Why would these medical personnel write such self-incriminating evidence? The researchers say it’s unclear. “They don’t think anyone’s reading this stuff,” Mr. Robertson suggests. “Sometimes it’s revealed in just five or six characters in a paper of eight pages.” Dr. Lavee wonders if it’s also ignorance. “If this has been a practice for 20 or 30 years in China, I guess nobody at that time was aware they were doing something wrong, although how to declare brain death is something that is known in China. They’ve published a lot about it.”

The article is “evidence that this barbarity continues and is a very valuable contribution that continues to bring attention to an enormous human rights violation,” said Arthur Caplan, PhD, head of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine. “What they’ve reported has been going on for many, many years, the data are very clear that China’s doing many more transplants than they have cadaver organ donors,” he said, adding that the country’s well-documented and lucrative involvement in transplant tourism “means you have to have a donor ready when the would-be recipient appears; you have to have a matched organ available, and that’s hard to do waiting on a cadaver donor.”

Although the researchers found no incriminating publications after 2015, they speculate that this is likely due to growing awareness among Chinese surgeons that publishing the information would attract international condemnation. “We think these practices are continuing to go on,” said Dr. Lavee. He acknowledged that a voluntary organ donation program is slowly developing in parallel to this. He said, given China’s place as the world’s second largest transplant country behind the U.S., as well as its low rate of voluntary donation, it’s reasonable to conclude that the main source of organs remains prisoners on death row.

Dr. Caplan and the researchers have called for academic institutions and medical journals to resume their previous boycotts of Chinese transplant publications and speakers, but as long as China denies the practices, economic and political leaders will turn a blind eye. “In the past, I don’t think the question of China’s medical professional involvement in the execution of donors has been taken as seriously as it should have,” said Mr. Robertson. “I certainly hope that with the publication of this paper in the leading journal in the field, this will change.”

The study was supported by the Google Cloud Research Credits program, the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. Mr. Robertson, Dr. Lavee, and Dr. Caplan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a deep dive into obscure Chinese language transplant journals, a pair of researchers from Australia and Israel have added a new layer of horror to what’s already known about forced organ harvesting in China.

Searching for documentation that vital organs are being harvested from nonconsenting executed prisoners, a practice that the China Tribunal confirmed “beyond any reasonable doubt” in 2020, Jacob Lavee, MD, an Israeli heart transplant surgeon, and Matthew Roberston, a PhD student at Australian National University, uncovered something even more shocking: that vital organs are being explanted from patients who are still alive.

“We have shown for the first time that the transplant surgeons are the executioners – that the mode of execution is organ procurement. These are self-admissions of executing the patient,” Dr. Lavee told this news organization. “Up until now, there has been what we call circumstantial evidence of this, but our paper is what you’d call the smoking gun, because it’s in the words of the physicians themselves that they are doing it. In the words of these surgeons, intubation was done only after the beginning of surgery, which means the patients were breathing spontaneously up until the moment the operation started ... meaning they were not brain dead.”

The research, published in the American Journal of Transplantation, involved intricate analysis of thousands of Chinese language transplant articles and identified 71 articles in which transplant surgeons describe starting organ procurement surgery before declaring their patients brain dead.

“What we found were improper, illegitimate, nonexistent, or false declarations of brain death,” Mr. Robertson said in an interview. He explained that this violates what’s known as the dead donor rule, which is fundamental in transplant ethics. “The surgeons wrote that the donor was brain dead, but according to everything we know about medical science, they could not possibly have been brain dead because there was no apnea test performed. Brain death is not just something you say, there’s this whole battery of tests, and the key is the apnea test, [in which] the patient is already intubated and ventilated, they turn the machine off, and they’re looking for carbon dioxide in the blood above a certain level.”

Mr. Robertson and Dr. Lavee have painstakingly documented “incriminating sentences” in each of the 71 articles proving that brain death had not occurred before the organ explantation procedure began. “There were two criteria by which we claimed a problematic brain death declaration,” said Mr. Robertson, who translated the Chinese. “One was where the patient was not ventilated and was only intubated after they were declared brain dead; the other was that the intubation took place immediately prior to the surgery beginning.”

“It was mind-boggling,” said Dr. Lavee, from Tel Aviv University. “When I first started reading, my initial reaction is, ‘This can’t be.’ I read it once, and again, and I insisted that Matt get another independent translation of the Chinese just to be sure. I told him, ‘There’s no way a physician, a surgeon could write this – it doesn’t make sense.’ But the more of these papers we read, we saw it was a pattern – and they didn’t come out of a single medical center, they are spread all over China.”

For the analysis, Mr. Robertson wrote code and customized an algorithm to examine 124,770 medical articles from official Chinese databases between 1980 and 2020. The 71 articles revealing cases involving problematic brain death came from 56 hospitals (of which 12 were military) in 33 cities across 15 provinces, they report. In total, 348 surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, and other medical workers or researchers were listed as authors of these publications.

Why would these medical personnel write such self-incriminating evidence? The researchers say it’s unclear. “They don’t think anyone’s reading this stuff,” Mr. Robertson suggests. “Sometimes it’s revealed in just five or six characters in a paper of eight pages.” Dr. Lavee wonders if it’s also ignorance. “If this has been a practice for 20 or 30 years in China, I guess nobody at that time was aware they were doing something wrong, although how to declare brain death is something that is known in China. They’ve published a lot about it.”

The article is “evidence that this barbarity continues and is a very valuable contribution that continues to bring attention to an enormous human rights violation,” said Arthur Caplan, PhD, head of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine. “What they’ve reported has been going on for many, many years, the data are very clear that China’s doing many more transplants than they have cadaver organ donors,” he said, adding that the country’s well-documented and lucrative involvement in transplant tourism “means you have to have a donor ready when the would-be recipient appears; you have to have a matched organ available, and that’s hard to do waiting on a cadaver donor.”

Although the researchers found no incriminating publications after 2015, they speculate that this is likely due to growing awareness among Chinese surgeons that publishing the information would attract international condemnation. “We think these practices are continuing to go on,” said Dr. Lavee. He acknowledged that a voluntary organ donation program is slowly developing in parallel to this. He said, given China’s place as the world’s second largest transplant country behind the U.S., as well as its low rate of voluntary donation, it’s reasonable to conclude that the main source of organs remains prisoners on death row.

Dr. Caplan and the researchers have called for academic institutions and medical journals to resume their previous boycotts of Chinese transplant publications and speakers, but as long as China denies the practices, economic and political leaders will turn a blind eye. “In the past, I don’t think the question of China’s medical professional involvement in the execution of donors has been taken as seriously as it should have,” said Mr. Robertson. “I certainly hope that with the publication of this paper in the leading journal in the field, this will change.”

The study was supported by the Google Cloud Research Credits program, the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. Mr. Robertson, Dr. Lavee, and Dr. Caplan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

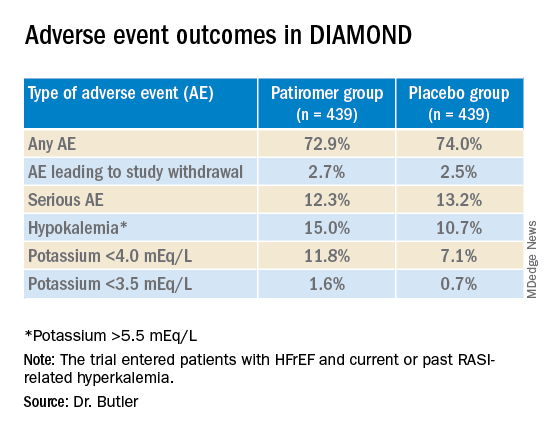

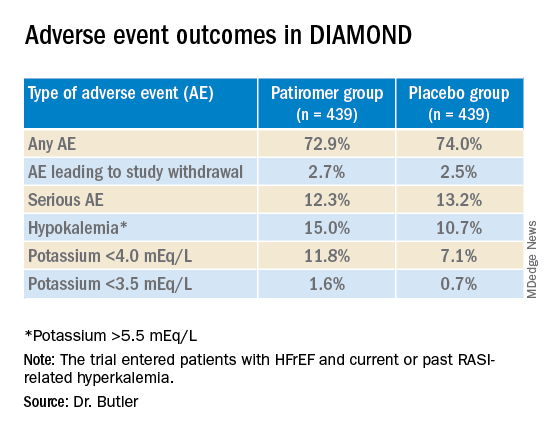

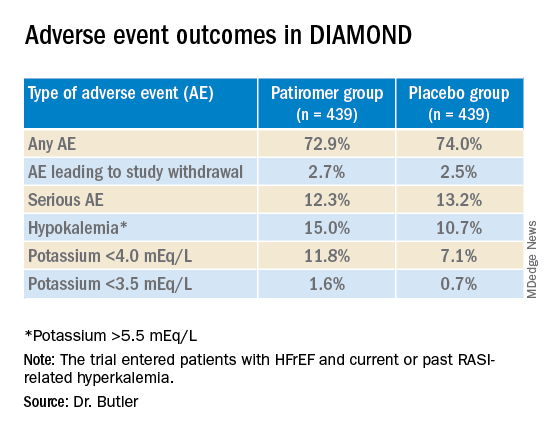

DIAMOND: Adding patiromer helps optimize HF meds, foils hyperkalemia

Several of the core medications for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) come with a well-known risk of causing hyperkalemia, to which many clinicians respond by pulling back on dosing or withdrawing the culprit drug.

But accompanying renin-angiotensin system–inhibiting agents with the potassium-sequestrant patiromer (Veltassa, Vifor Pharma) appears to shield patients against hyperkalemia enough that they can take more RASI medications at higher doses, suggests a randomized, a controlled study.

The DIAMOND trial’s HFrEF patients, who had current or a history of RASI-related hyperkalemia, added either patiromer or placebo to their guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), which includes, even emphasizes, the culprit medication. They include ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs).

Those taking patiromer tolerated more intense RASI therapy – including MRAs, which are especially prone to causing hyperkalemia – than the patients assigned to placebo. They also maintained lower potassium concentrations and experienced fewer clinically important hyperkalemia episodes, reported Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The apparent benefit from patiromer came in part from an advantage for a composite hyperkalemia-event endpoint that included mortality, Dr. Butler noted. That advantage seemed to hold regardless of age, sex, body mass index, HFrEF symptom severity, or initial natriuretic peptide levels.

Patients who took patiromer, compared with those who took placebo, showed a 37% reduction in risk for hyperkalemia (P = .006), defined as potassium levels exceeding 5.5 mEq/L, over a median follow-up of 27 weeks. They were 38% less likely to have their MRA dosage reduced to below target level (P = .006).

More patients in the patiromer group than in the control group attained at least 50% of target dosage for MRAs and ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or ARNIs (92% vs. 87%; P = .015).

Patients with HFrEF are unlikely to achieve best possible outcomes without GDMT optimization, but failure to optimize is often attributed to hyperkalemia concerns. DIAMOND, Dr. Butler said, suggests that, by adding the potassium sequestrant to GDMT, “you can simultaneously control potassium and optimize RASI therapy.” Many clinicians seem to believe they can achieve only one or the other.

DIAMOND was too underpowered to show whether preventing hyperkalemia with patiromer could improve clinical outcomes. But failure to optimize RASI medication in HFrEF can worsen risk for heart failure events and death. So “it stands to reason that optimization of RASI therapy without a concomitant risk of hyperkalemia may, in the long run, lead to better outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Butler said in an interview.

Given the drug’s ability to keep potassium levels in check during RASI therapy, Dr. Butler said, “hypokalemia should not be a reason for suboptimal therapy.”

Patiromer and other potassium sequestrants have been available in the United States and Europe for 4-6 years, but their value as adjuncts to RASI medication in HFrEF or other heart failure has been unclear.

“There’s a good opportunity to expand the use of the drug. The question is, in whom and when?” James L. Januzzi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

Some HFrEF patients on GDMT “should be treated with patiromer. The bigger question is, should we give someone who has a history of hyperkalemia another chance at GDMT before we treat them with patiromer? Because they may not necessarily develop hyperkalemia a second time,” said Dr. Januzzi, who was on the DIAMOND endpoint-adjudication committee.

Among the most notable findings of the trial, he said, is that the number of people who developed hyperkalemia on RASI medication, although significantly elevated, “wasn’t as high as they expected it would be,” he said. “The data from DIAMOND argue that if a really significant majority does not become hyperkalemic on rechallenge, jumping straight to a potassium-binding drug may be premature.”

Physicians across specialties can differ in how they interpret potassium-level elevation and can use various cut points to flag when to stop RASI medication or at least hold back on up-titration, Dr. Butler observed. “Cardiologists have a different threshold of potassium that they tolerate than say, for instance, a nephrologist.”

Useful, then, might be a way to tell which patients are most likely to develop hyperkalemia with RASI up-titration and so might benefit from a potassium-binding agent right away. But DIAMOND, Dr. Butler said, “does not necessarily define any patient phenotype or any potassium level where we would say that you should use a potassium binder.”

The trial entered 1,642 patients with HFrEF and current or past RASI-related hyperkalemia to a 12-week run-in phase for optimization of GDMT with patiromer. The trial was conducted at nearly 400 centers in 21 countries.

RASI medication could be optimized in 85% of the cohort, from which 878 patients were randomly assigned either to continue optimized GDMT with patiromer or to have the potassium-sequestrant replaced with a placebo.

The patients on patiromer showed a 0.03-mEq/L mean rise in serum potassium levels from randomization to the end of the study, the primary endpoint, compared with a 0.13 mEq/L mean increase for those in the control group (P < .001), Dr. Butler reported.

The win ratio for a RASI-use score hierarchically featuring cardiovascular death and CV hospitalization for hyperkalemia at several levels of severity was 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.564; P = .048), favoring the patiromer group. The win ratio solely for hyperkalemia-related events also favored patients on patiromer, at 1.53 (95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001).

Patiromer also seemed well tolerated, Dr. Butler said.

Hyperkalemia is “one of the most common excuses” from clinicians for failing to up-titrate RASI medicine in patients with heart failure, Dr. Januzzi said. DIAMOND was less about patiromer itself than about ways “to facilitate better GDMT, where we’re really falling short of the mark. During the run-in phase they were able to get the vast majority of individuals to target, which to me is a critically important point, and emblematic of the need for things that facilitate this kind of excellent care.”

DIAMOND was funded by Vifor Pharma. Dr. Butler disclosed receiving consulting fees from Abbott, Adrenomed, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, Array, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CVRx, G3 Pharma, Impulse Dynamics, Innolife, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Relypsa, Sequana Medical, and Vifor Pharma. Dr. Januzzi disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abbott Laboratories, Imbria, Jana Care, Novartis, Prevencio, and Roche Diagnostics; serving on a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Amgen, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Beyer, CVRx, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America; and receiving research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Janssen, and Vifor Pharma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several of the core medications for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) come with a well-known risk of causing hyperkalemia, to which many clinicians respond by pulling back on dosing or withdrawing the culprit drug.

But accompanying renin-angiotensin system–inhibiting agents with the potassium-sequestrant patiromer (Veltassa, Vifor Pharma) appears to shield patients against hyperkalemia enough that they can take more RASI medications at higher doses, suggests a randomized, a controlled study.

The DIAMOND trial’s HFrEF patients, who had current or a history of RASI-related hyperkalemia, added either patiromer or placebo to their guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), which includes, even emphasizes, the culprit medication. They include ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs).

Those taking patiromer tolerated more intense RASI therapy – including MRAs, which are especially prone to causing hyperkalemia – than the patients assigned to placebo. They also maintained lower potassium concentrations and experienced fewer clinically important hyperkalemia episodes, reported Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The apparent benefit from patiromer came in part from an advantage for a composite hyperkalemia-event endpoint that included mortality, Dr. Butler noted. That advantage seemed to hold regardless of age, sex, body mass index, HFrEF symptom severity, or initial natriuretic peptide levels.

Patients who took patiromer, compared with those who took placebo, showed a 37% reduction in risk for hyperkalemia (P = .006), defined as potassium levels exceeding 5.5 mEq/L, over a median follow-up of 27 weeks. They were 38% less likely to have their MRA dosage reduced to below target level (P = .006).

More patients in the patiromer group than in the control group attained at least 50% of target dosage for MRAs and ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or ARNIs (92% vs. 87%; P = .015).

Patients with HFrEF are unlikely to achieve best possible outcomes without GDMT optimization, but failure to optimize is often attributed to hyperkalemia concerns. DIAMOND, Dr. Butler said, suggests that, by adding the potassium sequestrant to GDMT, “you can simultaneously control potassium and optimize RASI therapy.” Many clinicians seem to believe they can achieve only one or the other.

DIAMOND was too underpowered to show whether preventing hyperkalemia with patiromer could improve clinical outcomes. But failure to optimize RASI medication in HFrEF can worsen risk for heart failure events and death. So “it stands to reason that optimization of RASI therapy without a concomitant risk of hyperkalemia may, in the long run, lead to better outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Butler said in an interview.

Given the drug’s ability to keep potassium levels in check during RASI therapy, Dr. Butler said, “hypokalemia should not be a reason for suboptimal therapy.”

Patiromer and other potassium sequestrants have been available in the United States and Europe for 4-6 years, but their value as adjuncts to RASI medication in HFrEF or other heart failure has been unclear.

“There’s a good opportunity to expand the use of the drug. The question is, in whom and when?” James L. Januzzi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

Some HFrEF patients on GDMT “should be treated with patiromer. The bigger question is, should we give someone who has a history of hyperkalemia another chance at GDMT before we treat them with patiromer? Because they may not necessarily develop hyperkalemia a second time,” said Dr. Januzzi, who was on the DIAMOND endpoint-adjudication committee.

Among the most notable findings of the trial, he said, is that the number of people who developed hyperkalemia on RASI medication, although significantly elevated, “wasn’t as high as they expected it would be,” he said. “The data from DIAMOND argue that if a really significant majority does not become hyperkalemic on rechallenge, jumping straight to a potassium-binding drug may be premature.”

Physicians across specialties can differ in how they interpret potassium-level elevation and can use various cut points to flag when to stop RASI medication or at least hold back on up-titration, Dr. Butler observed. “Cardiologists have a different threshold of potassium that they tolerate than say, for instance, a nephrologist.”

Useful, then, might be a way to tell which patients are most likely to develop hyperkalemia with RASI up-titration and so might benefit from a potassium-binding agent right away. But DIAMOND, Dr. Butler said, “does not necessarily define any patient phenotype or any potassium level where we would say that you should use a potassium binder.”

The trial entered 1,642 patients with HFrEF and current or past RASI-related hyperkalemia to a 12-week run-in phase for optimization of GDMT with patiromer. The trial was conducted at nearly 400 centers in 21 countries.

RASI medication could be optimized in 85% of the cohort, from which 878 patients were randomly assigned either to continue optimized GDMT with patiromer or to have the potassium-sequestrant replaced with a placebo.

The patients on patiromer showed a 0.03-mEq/L mean rise in serum potassium levels from randomization to the end of the study, the primary endpoint, compared with a 0.13 mEq/L mean increase for those in the control group (P < .001), Dr. Butler reported.

The win ratio for a RASI-use score hierarchically featuring cardiovascular death and CV hospitalization for hyperkalemia at several levels of severity was 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.564; P = .048), favoring the patiromer group. The win ratio solely for hyperkalemia-related events also favored patients on patiromer, at 1.53 (95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001).

Patiromer also seemed well tolerated, Dr. Butler said.

Hyperkalemia is “one of the most common excuses” from clinicians for failing to up-titrate RASI medicine in patients with heart failure, Dr. Januzzi said. DIAMOND was less about patiromer itself than about ways “to facilitate better GDMT, where we’re really falling short of the mark. During the run-in phase they were able to get the vast majority of individuals to target, which to me is a critically important point, and emblematic of the need for things that facilitate this kind of excellent care.”

DIAMOND was funded by Vifor Pharma. Dr. Butler disclosed receiving consulting fees from Abbott, Adrenomed, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, Array, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CVRx, G3 Pharma, Impulse Dynamics, Innolife, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Relypsa, Sequana Medical, and Vifor Pharma. Dr. Januzzi disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abbott Laboratories, Imbria, Jana Care, Novartis, Prevencio, and Roche Diagnostics; serving on a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Amgen, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Beyer, CVRx, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America; and receiving research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Janssen, and Vifor Pharma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several of the core medications for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) come with a well-known risk of causing hyperkalemia, to which many clinicians respond by pulling back on dosing or withdrawing the culprit drug.

But accompanying renin-angiotensin system–inhibiting agents with the potassium-sequestrant patiromer (Veltassa, Vifor Pharma) appears to shield patients against hyperkalemia enough that they can take more RASI medications at higher doses, suggests a randomized, a controlled study.

The DIAMOND trial’s HFrEF patients, who had current or a history of RASI-related hyperkalemia, added either patiromer or placebo to their guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), which includes, even emphasizes, the culprit medication. They include ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs).

Those taking patiromer tolerated more intense RASI therapy – including MRAs, which are especially prone to causing hyperkalemia – than the patients assigned to placebo. They also maintained lower potassium concentrations and experienced fewer clinically important hyperkalemia episodes, reported Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The apparent benefit from patiromer came in part from an advantage for a composite hyperkalemia-event endpoint that included mortality, Dr. Butler noted. That advantage seemed to hold regardless of age, sex, body mass index, HFrEF symptom severity, or initial natriuretic peptide levels.

Patients who took patiromer, compared with those who took placebo, showed a 37% reduction in risk for hyperkalemia (P = .006), defined as potassium levels exceeding 5.5 mEq/L, over a median follow-up of 27 weeks. They were 38% less likely to have their MRA dosage reduced to below target level (P = .006).

More patients in the patiromer group than in the control group attained at least 50% of target dosage for MRAs and ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or ARNIs (92% vs. 87%; P = .015).

Patients with HFrEF are unlikely to achieve best possible outcomes without GDMT optimization, but failure to optimize is often attributed to hyperkalemia concerns. DIAMOND, Dr. Butler said, suggests that, by adding the potassium sequestrant to GDMT, “you can simultaneously control potassium and optimize RASI therapy.” Many clinicians seem to believe they can achieve only one or the other.

DIAMOND was too underpowered to show whether preventing hyperkalemia with patiromer could improve clinical outcomes. But failure to optimize RASI medication in HFrEF can worsen risk for heart failure events and death. So “it stands to reason that optimization of RASI therapy without a concomitant risk of hyperkalemia may, in the long run, lead to better outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Butler said in an interview.

Given the drug’s ability to keep potassium levels in check during RASI therapy, Dr. Butler said, “hypokalemia should not be a reason for suboptimal therapy.”

Patiromer and other potassium sequestrants have been available in the United States and Europe for 4-6 years, but their value as adjuncts to RASI medication in HFrEF or other heart failure has been unclear.

“There’s a good opportunity to expand the use of the drug. The question is, in whom and when?” James L. Januzzi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

Some HFrEF patients on GDMT “should be treated with patiromer. The bigger question is, should we give someone who has a history of hyperkalemia another chance at GDMT before we treat them with patiromer? Because they may not necessarily develop hyperkalemia a second time,” said Dr. Januzzi, who was on the DIAMOND endpoint-adjudication committee.

Among the most notable findings of the trial, he said, is that the number of people who developed hyperkalemia on RASI medication, although significantly elevated, “wasn’t as high as they expected it would be,” he said. “The data from DIAMOND argue that if a really significant majority does not become hyperkalemic on rechallenge, jumping straight to a potassium-binding drug may be premature.”

Physicians across specialties can differ in how they interpret potassium-level elevation and can use various cut points to flag when to stop RASI medication or at least hold back on up-titration, Dr. Butler observed. “Cardiologists have a different threshold of potassium that they tolerate than say, for instance, a nephrologist.”

Useful, then, might be a way to tell which patients are most likely to develop hyperkalemia with RASI up-titration and so might benefit from a potassium-binding agent right away. But DIAMOND, Dr. Butler said, “does not necessarily define any patient phenotype or any potassium level where we would say that you should use a potassium binder.”

The trial entered 1,642 patients with HFrEF and current or past RASI-related hyperkalemia to a 12-week run-in phase for optimization of GDMT with patiromer. The trial was conducted at nearly 400 centers in 21 countries.

RASI medication could be optimized in 85% of the cohort, from which 878 patients were randomly assigned either to continue optimized GDMT with patiromer or to have the potassium-sequestrant replaced with a placebo.

The patients on patiromer showed a 0.03-mEq/L mean rise in serum potassium levels from randomization to the end of the study, the primary endpoint, compared with a 0.13 mEq/L mean increase for those in the control group (P < .001), Dr. Butler reported.

The win ratio for a RASI-use score hierarchically featuring cardiovascular death and CV hospitalization for hyperkalemia at several levels of severity was 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.564; P = .048), favoring the patiromer group. The win ratio solely for hyperkalemia-related events also favored patients on patiromer, at 1.53 (95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001).

Patiromer also seemed well tolerated, Dr. Butler said.

Hyperkalemia is “one of the most common excuses” from clinicians for failing to up-titrate RASI medicine in patients with heart failure, Dr. Januzzi said. DIAMOND was less about patiromer itself than about ways “to facilitate better GDMT, where we’re really falling short of the mark. During the run-in phase they were able to get the vast majority of individuals to target, which to me is a critically important point, and emblematic of the need for things that facilitate this kind of excellent care.”

DIAMOND was funded by Vifor Pharma. Dr. Butler disclosed receiving consulting fees from Abbott, Adrenomed, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, Array, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CVRx, G3 Pharma, Impulse Dynamics, Innolife, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Relypsa, Sequana Medical, and Vifor Pharma. Dr. Januzzi disclosed receiving consultant fees or honoraria from Abbott Laboratories, Imbria, Jana Care, Novartis, Prevencio, and Roche Diagnostics; serving on a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Amgen, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Beyer, CVRx, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America; and receiving research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Janssen, and Vifor Pharma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACC 2022

Apremilast has neutral effect on vascular inflammation in psoriasis study

BOSTON – Treatment with , and glucose metabolism, in a study presented at the 2022 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

In the phase 4, open-label, single arm trial, participants also lost subcutaneous and visceral fat after 16 weeks on the oral medication, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, and maintained that loss at 52 weeks.

People with psoriasis have an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular events. Patients with more significant psoriasis “tend to die about 5 years younger than they should, based on their risk factors for mortality,” Joel Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor of dermatology and epidemiology and vice chair of clinical research in dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

He led the research and presented the findings at the AAD meeting March 26. “As a result, there has been a keen interest in understanding how psoriasis therapies impact cardiovascular risk, the idea being that by controlling inflammation, you may lower the risk of these patients developing cardiovascular disease over time,” he said.

Previous trials looking at the effect of psoriasis therapies on vascular inflammation “have been, for the most part, inconclusive,” Michael Garshick, MD, a cardiologist at NYU Langone Health, told this news organization. Dr. Garshick was not involved with the research. A 2021 systematic review of psoriasis clinicals trials reported that the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker adalimumab (Humira) and phototherapy had the greatest effect on cardiometabolic markers, while ustekinumab (Stelara), an interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 antagonist, was the only treatment that improved vascular inflammation. These variable findings make this area “ripe for study,” noted Dr. Garshick.

To observe how apremilast, which is approved by the FDA for treating psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, affected vascular inflammation, adiposity, and blood-based cardiometabolic markers, Dr. Gelfand organized an open-label study in adults with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. All participants were 18 years or older, had psoriasis for at least 6 months, and were candidates for systemic therapy. All patients underwent FDG PET/CT scans to assess aortic vascular inflammation and had blood work at baseline. Of the 70 patients originally enrolled in the study, 60 remained in the study at week 16, including 57 who underwent imaging for the second time. Thirty-nine participants remained in the study until week 52, and all except one had another scan.

The average age of participants was 47 years, and their mean BMI was 30. More than 80% of participants were White (83%) and 77% were male. The study population had lived with psoriasis for an average of 16 years and 8 patients also had psoriatic arthritis. At baseline, on average, participants had a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 18.62, a dermatology life quality index (DLQI) score of 11.60, and 22% of participants’ BSA (body surface area) were affected. The mean TBRmax, the marker for vascular inflammation, was 1.61.

Treatment responses were as expected for apremilast, with 35% of patients achieving PASI 75 and 65% of participants reporting DLQI scores of 5 or less by 16 weeks. At 52 weeks, 31% of the cohort had achieved PASI 75, and 67% reported DLQI score of 5 or higher. All psoriasis endpoints had improved since baseline (P = .001).

Throughout the study period, there was no significant change in TBRmax. However, in a sensitivity analysis, the 16 patients with a baseline TBRmax of 1.6 or higher had an absolute reduction of 0.21 in TBR by week 52. “That suggests that maybe a subset of people who have higher levels of aortic inflammation at baseline may experience some reduction that portend, potentially, some health benefits over time,” Dr. Gelfand said. “Ultimately, I wouldn’t hang my hat on the finding,” he said, noting that additional research comparing the treatment to placebo is necessary.

Both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue (VAT and SAT) decreased by week 16, and this reduction was maintained through week 52. In the first 16 weeks of the study, VAT decreased by 5.32% (P = .0009), and SAT decreased by 5.53% (P = .0005). From baseline to 52 weeks, VAT decreased by 5.52% (P = .0148), and SAT decreased by 5.50% (P = .0096). There were no significant differences between week 16 and week 52 in VAT or SAT.

Of the 68 blood biomarkers analyzed, there were significant decreases in the inflammatory markers ferritin (P = .015) and IL-beta (P = .006), the lipid metabolism biomarker HDL-cholesterol efflux (P = .008), and ketone bodies (P = .006). There were also increases in the inflammatory marker IL-8 (P = .003), the lipid metabolism marker ApoA (P = .05), and insulin (P = .05). Ferritin was the only biomarker that was reduced on both week 16 and week 52.

“If you want to be a purist, this was a negative trial,” said Dr. Garshick, because apremilast was not found to decrease vascular inflammation; however, he noted that the biomarker changes “were hopeful secondary endpoints.” It could be, he said, that another outcome measure may be better able to show changes in vascular inflammation compared with FDG. “It’s always hard to figure out what a good surrogate endpoint is in cardiovascular trials,” he noted, “so it may be that FDG/PET is too noisy or not reliable enough to see the outcome that we want to see.”

Dr. Gelfand reports consulting fees/grants from Amgen, AbbVie, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, Pfizer, and UCB (DSMB). He serves as the Deputy Editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology and the Chief Medical Editor at Healio Psoriatic Disease and receives honoraria for both roles. Dr. Garshick has received consulting fees from AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – Treatment with , and glucose metabolism, in a study presented at the 2022 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

In the phase 4, open-label, single arm trial, participants also lost subcutaneous and visceral fat after 16 weeks on the oral medication, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, and maintained that loss at 52 weeks.

People with psoriasis have an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular events. Patients with more significant psoriasis “tend to die about 5 years younger than they should, based on their risk factors for mortality,” Joel Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor of dermatology and epidemiology and vice chair of clinical research in dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

He led the research and presented the findings at the AAD meeting March 26. “As a result, there has been a keen interest in understanding how psoriasis therapies impact cardiovascular risk, the idea being that by controlling inflammation, you may lower the risk of these patients developing cardiovascular disease over time,” he said.

Previous trials looking at the effect of psoriasis therapies on vascular inflammation “have been, for the most part, inconclusive,” Michael Garshick, MD, a cardiologist at NYU Langone Health, told this news organization. Dr. Garshick was not involved with the research. A 2021 systematic review of psoriasis clinicals trials reported that the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker adalimumab (Humira) and phototherapy had the greatest effect on cardiometabolic markers, while ustekinumab (Stelara), an interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 antagonist, was the only treatment that improved vascular inflammation. These variable findings make this area “ripe for study,” noted Dr. Garshick.

To observe how apremilast, which is approved by the FDA for treating psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, affected vascular inflammation, adiposity, and blood-based cardiometabolic markers, Dr. Gelfand organized an open-label study in adults with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. All participants were 18 years or older, had psoriasis for at least 6 months, and were candidates for systemic therapy. All patients underwent FDG PET/CT scans to assess aortic vascular inflammation and had blood work at baseline. Of the 70 patients originally enrolled in the study, 60 remained in the study at week 16, including 57 who underwent imaging for the second time. Thirty-nine participants remained in the study until week 52, and all except one had another scan.

The average age of participants was 47 years, and their mean BMI was 30. More than 80% of participants were White (83%) and 77% were male. The study population had lived with psoriasis for an average of 16 years and 8 patients also had psoriatic arthritis. At baseline, on average, participants had a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 18.62, a dermatology life quality index (DLQI) score of 11.60, and 22% of participants’ BSA (body surface area) were affected. The mean TBRmax, the marker for vascular inflammation, was 1.61.

Treatment responses were as expected for apremilast, with 35% of patients achieving PASI 75 and 65% of participants reporting DLQI scores of 5 or less by 16 weeks. At 52 weeks, 31% of the cohort had achieved PASI 75, and 67% reported DLQI score of 5 or higher. All psoriasis endpoints had improved since baseline (P = .001).

Throughout the study period, there was no significant change in TBRmax. However, in a sensitivity analysis, the 16 patients with a baseline TBRmax of 1.6 or higher had an absolute reduction of 0.21 in TBR by week 52. “That suggests that maybe a subset of people who have higher levels of aortic inflammation at baseline may experience some reduction that portend, potentially, some health benefits over time,” Dr. Gelfand said. “Ultimately, I wouldn’t hang my hat on the finding,” he said, noting that additional research comparing the treatment to placebo is necessary.

Both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue (VAT and SAT) decreased by week 16, and this reduction was maintained through week 52. In the first 16 weeks of the study, VAT decreased by 5.32% (P = .0009), and SAT decreased by 5.53% (P = .0005). From baseline to 52 weeks, VAT decreased by 5.52% (P = .0148), and SAT decreased by 5.50% (P = .0096). There were no significant differences between week 16 and week 52 in VAT or SAT.

Of the 68 blood biomarkers analyzed, there were significant decreases in the inflammatory markers ferritin (P = .015) and IL-beta (P = .006), the lipid metabolism biomarker HDL-cholesterol efflux (P = .008), and ketone bodies (P = .006). There were also increases in the inflammatory marker IL-8 (P = .003), the lipid metabolism marker ApoA (P = .05), and insulin (P = .05). Ferritin was the only biomarker that was reduced on both week 16 and week 52.

“If you want to be a purist, this was a negative trial,” said Dr. Garshick, because apremilast was not found to decrease vascular inflammation; however, he noted that the biomarker changes “were hopeful secondary endpoints.” It could be, he said, that another outcome measure may be better able to show changes in vascular inflammation compared with FDG. “It’s always hard to figure out what a good surrogate endpoint is in cardiovascular trials,” he noted, “so it may be that FDG/PET is too noisy or not reliable enough to see the outcome that we want to see.”

Dr. Gelfand reports consulting fees/grants from Amgen, AbbVie, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, Pfizer, and UCB (DSMB). He serves as the Deputy Editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology and the Chief Medical Editor at Healio Psoriatic Disease and receives honoraria for both roles. Dr. Garshick has received consulting fees from AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – Treatment with , and glucose metabolism, in a study presented at the 2022 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

In the phase 4, open-label, single arm trial, participants also lost subcutaneous and visceral fat after 16 weeks on the oral medication, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, and maintained that loss at 52 weeks.

People with psoriasis have an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular events. Patients with more significant psoriasis “tend to die about 5 years younger than they should, based on their risk factors for mortality,” Joel Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor of dermatology and epidemiology and vice chair of clinical research in dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

He led the research and presented the findings at the AAD meeting March 26. “As a result, there has been a keen interest in understanding how psoriasis therapies impact cardiovascular risk, the idea being that by controlling inflammation, you may lower the risk of these patients developing cardiovascular disease over time,” he said.