User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

New recommendations for hyperglycemia management

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

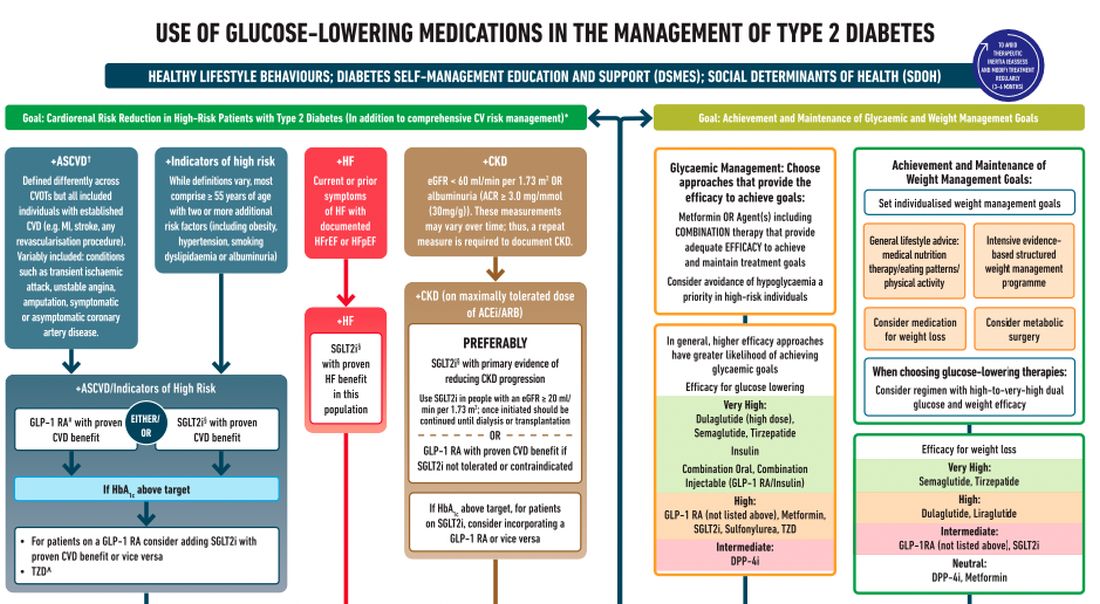

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

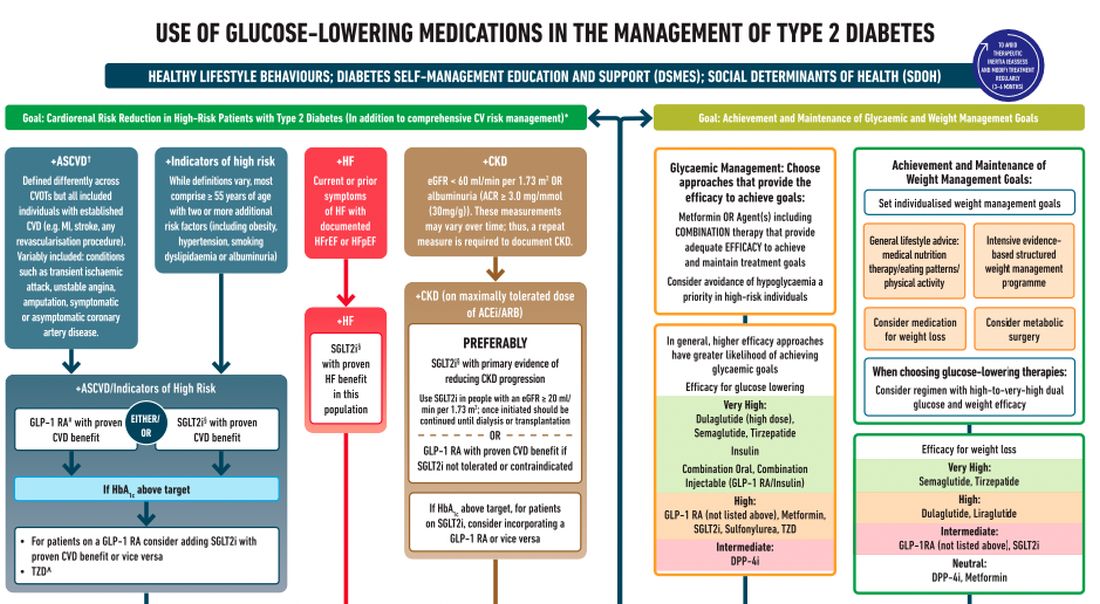

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

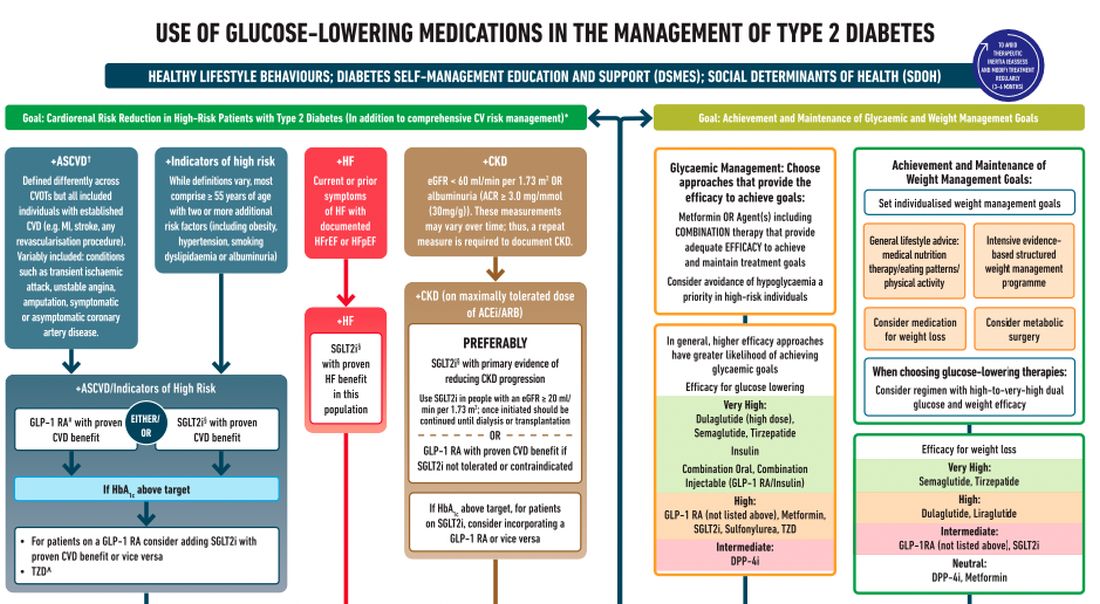

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients complain some obesity care startups offer pills, and not much else

Many Americans turn to the latest big idea to lose weight – fad diets, fitness crazes, dodgy herbs and pills, bariatric surgery, just to name a few. They’re rarely the magic solution people dream of.

Now a wave of startups offer access to a new category of drugs coupled with intensive behavioral coaching online. But already concerns are emerging.

These startups, spurred by hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from blue-chip venture capital firms, have signed up well over 100,000 patients and could reach millions more. These patients pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to access new drugs, called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists, along with online coaching to encourage healthy habits.

The startups initially positioned themselves in lofty terms. “This is the last weight-loss program you’ll try,” said a 2020 marketing analysis by startup Calibrate Health, in messaging designed to reach one of its target demographics, the “working mom.” (Company spokesperson Michelle Wellington said the document does not reflect Calibrate’s current marketing strategy.)

But while doctors and patients are intrigued by the new model, some customers complain online that reality is short of the buildup: They say they got canned advice and unresponsive clinicians – and some report they couldn’t get the newest drugs.

Calibrate Health, a New York City–based startup, reported earlier in 2022 it had served 20,000 people. Another startup, Found, headquartered in San Francisco, has served 135,000 patients since July 2020, CEO Sarah Jones Simmer said in an interview. Calibrate costs patients nearly $1,600 a year, not counting the price of drugs, which can hit nearly $1,500 monthly without insurance, according to drug price savings site GoodRx. (Insurers reimburse for GLP-1agonists in limited circumstances, patients said.) Found offers a 6-month plan for nearly $600, a company spokesperson said. (That price includes generic drugs, but not the newer GLP-1 agonists, like Wegovy.)

The two companies are beneficiaries of over $200 million in combined venture funding, according to tracking by Crunchbase, a repository of venture capital investments. The firms say they’re on the vanguard of weight care, both citing the influence of biology and other scientific factors as key ingredients to their approaches.

There’s potentially a big market for these startups. Just over 4 in 10 Americans are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, driving up their risk for cardiovascular conditions and type 2 diabetes. Effective medical treatments are elusive and hard to access.

Centers that provide this specialty care “are overwhelmed,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General in Boston, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard. Her own clinic has a wait list of 3,000.

Dr. Stanford, who said she has advised several of these telemedicine startups, is bullish on their potential.

Scott Butsch, MD, director of obesity medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said the startups can offer care with less judgment and stigma than in-person peers. They’re also more convenient.

Dr. Butsch, who learned about the model through consultancies, patients, and colleagues, wonders whether the startups are operating “to strategically find which patients respond to which drug.” He said they should coordinate well with behavioral specialists, as antidepressants or other medications may be driving weight gain. “Obesity is a complex disease and requires treatments that match its complexity. I think programs that do not have a multidisciplinary team are less comprehensive and, in the long term, less effective.”

The startups market a two-pronged product: first, the new class of GLP-1 agonists. While these medications are effective at provoking weight loss, Wegovy, one of two in this class specifically approved for this purpose, is in short supply because of manufacturing difficulties, according to its maker, Novo Nordisk. Others in the category can be prescribed off label. But doctors generally aren’t familiar with the medications, Stanford said. In theory, the startups can bridge some of those gaps: They offer more specialized, knowledgeable clinicians.

Then there’s the other prong: behavioral changes. The companies use televisits and online messaging with nutritionists or coaches to help patients incorporate new diet and exercise habits. The weight loss figures achieved by participants in clinical trials for the new drugs – up to 15% of body mass – were tied to such changes, according to Novo Nordisk.

Social media sites are bursting with these startups’ ads, everywhere from podcasts to Instagram. A search of Meta’s ad library finds 40,000 ads on Facebook and Instagram between the two firms.

The ads complement people’s own postings on social media: Numerous Facebook groups are devoted to the new type of drugs – some even focused on helping patients manage side effects, like changes in their bowel movements. The buzz is quantifiable: On TikTok, mentions of the new GLP-1 agonists tripled from last June to this June, according to an analysis by investment bankers at Morgan Stanley.

There’s now a feverish, expectant appetite for these medications among the startups’ clientele. Patients often complained that their friends had obtained a drug they weren’t offered, recalled Alexandra Coults, a former pharmacist consultant for Found. Ms. Coults said patients may have perceived some sort of bait-and-switch when in reality clinical reasons – like drug contraindications – guide prescribing decisions.

Patient expectations influence care, Ms. Coults said. Customers came in with ideas shaped by the culture of fad diets and New Year’s resolutions. “Quite a few people would sign up for 1 month and not continue.”

In interviews with KHN and in online complaints, patients also questioned the quality of care they received. Some said intake – which began by filling out a form and proceeded to an online visit with a doctor – was perfunctory. Once medication began, they said, requests for counseling about side effects were slow to be answered.

Jess Garrant, a Found patient, recalled that after she was prescribed zonisamide, a generic anticonvulsant that has shown some ability to help with weight loss, she felt “absolutely weird.”

“I was up all night and my thoughts were racing,” she wrote in a blog post. She developed sores in her mouth.

She sought advice and help from Found physicians, but their replies “weren’t quick.” Nonemergency communications are routed through the company’s portal.

It took a week to complete a switch of medications and have a new prescription arrive at her home, she said. Meanwhile, she said, she went to an urgent care clinic for the mouth sores.

Found frequently prescribes generic medications – often off label – rather than just the new GLP-1 agonists, company executives said in an interview. Found said older generics like zonisamide are more accessible than the GLP-1 agonists advertised on social media and their own website. Both Dr. Butsch and Dr. Stanford said they’ve prescribed zonisamide successfully. Dr. Butsch said ramping up dosage rapidly can increase the risk of side effects.

But Kim Boyd, MD, chief medical officer of competitor Calibrate, said the older drugs “just haven’t worked.”

Patients of both companies have critiqued online and in interviews the startups’ behavioral care – which experts across the board maintain is integral to successful weight loss treatment. But some patients felt they simply had canned advice.

Other patients said they had ups and downs with their coaches. Dana Crom, an attorney, said she had gone through many coaches with Calibrate. Some were good, effective cheerleaders; others, not so good. But when kinks in the program arose, she said, the coach wasn’t able to help her navigate them. While the coach can report trouble with medications or the app, it appears those reports are no more effective than messages sent through the portal, Ms. Crom said.

And what about when her yearlong subscription ends? Ms. Crom said she’d consider continuing with Calibrate.

Relationships with coaches, given the need to change behavior, are a critical element of the business models. Patients’ results depend “on how adherent they are to lifestyle changes,” said Found’s chief medical officer, Rehka Kumar, MD.

While the startups offer care to a larger geographic footprint, it’s not clear whether the demographics of their patient populations are different from those of the traditional bricks-and-mortar model. Calibrate’s patients are overwhelmingly White; over 8 in 10 have at least an undergraduate degree; and over 8 in 10 are women, according to the company.

And its earlier marketing strategies reflected that. The September 2020 “segmentation” document laid out three types of customers the company could hope to attract: perimenopausal or menopausal women, with income ranging from $75,000 to $150,000 a year; working mothers, with a similar income; and “men.”

Isabelle Kenyon, Calibrate’s CEO, said the company now hopes to expand its reach to partner with large employers, and that will help diversify its patients.

Patients will need to be convinced that the model – more affordable, more accessible – works for them. For her part, Ms. Garrant, who no longer is using Found, reflected on her experience, writing in her blog post that she was hoping for more follow-up and a more personal approach. “I don’t think it’s a helpful way to lose weight,” she said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Many Americans turn to the latest big idea to lose weight – fad diets, fitness crazes, dodgy herbs and pills, bariatric surgery, just to name a few. They’re rarely the magic solution people dream of.

Now a wave of startups offer access to a new category of drugs coupled with intensive behavioral coaching online. But already concerns are emerging.

These startups, spurred by hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from blue-chip venture capital firms, have signed up well over 100,000 patients and could reach millions more. These patients pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to access new drugs, called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists, along with online coaching to encourage healthy habits.

The startups initially positioned themselves in lofty terms. “This is the last weight-loss program you’ll try,” said a 2020 marketing analysis by startup Calibrate Health, in messaging designed to reach one of its target demographics, the “working mom.” (Company spokesperson Michelle Wellington said the document does not reflect Calibrate’s current marketing strategy.)

But while doctors and patients are intrigued by the new model, some customers complain online that reality is short of the buildup: They say they got canned advice and unresponsive clinicians – and some report they couldn’t get the newest drugs.

Calibrate Health, a New York City–based startup, reported earlier in 2022 it had served 20,000 people. Another startup, Found, headquartered in San Francisco, has served 135,000 patients since July 2020, CEO Sarah Jones Simmer said in an interview. Calibrate costs patients nearly $1,600 a year, not counting the price of drugs, which can hit nearly $1,500 monthly without insurance, according to drug price savings site GoodRx. (Insurers reimburse for GLP-1agonists in limited circumstances, patients said.) Found offers a 6-month plan for nearly $600, a company spokesperson said. (That price includes generic drugs, but not the newer GLP-1 agonists, like Wegovy.)

The two companies are beneficiaries of over $200 million in combined venture funding, according to tracking by Crunchbase, a repository of venture capital investments. The firms say they’re on the vanguard of weight care, both citing the influence of biology and other scientific factors as key ingredients to their approaches.

There’s potentially a big market for these startups. Just over 4 in 10 Americans are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, driving up their risk for cardiovascular conditions and type 2 diabetes. Effective medical treatments are elusive and hard to access.

Centers that provide this specialty care “are overwhelmed,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General in Boston, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard. Her own clinic has a wait list of 3,000.

Dr. Stanford, who said she has advised several of these telemedicine startups, is bullish on their potential.

Scott Butsch, MD, director of obesity medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said the startups can offer care with less judgment and stigma than in-person peers. They’re also more convenient.

Dr. Butsch, who learned about the model through consultancies, patients, and colleagues, wonders whether the startups are operating “to strategically find which patients respond to which drug.” He said they should coordinate well with behavioral specialists, as antidepressants or other medications may be driving weight gain. “Obesity is a complex disease and requires treatments that match its complexity. I think programs that do not have a multidisciplinary team are less comprehensive and, in the long term, less effective.”

The startups market a two-pronged product: first, the new class of GLP-1 agonists. While these medications are effective at provoking weight loss, Wegovy, one of two in this class specifically approved for this purpose, is in short supply because of manufacturing difficulties, according to its maker, Novo Nordisk. Others in the category can be prescribed off label. But doctors generally aren’t familiar with the medications, Stanford said. In theory, the startups can bridge some of those gaps: They offer more specialized, knowledgeable clinicians.

Then there’s the other prong: behavioral changes. The companies use televisits and online messaging with nutritionists or coaches to help patients incorporate new diet and exercise habits. The weight loss figures achieved by participants in clinical trials for the new drugs – up to 15% of body mass – were tied to such changes, according to Novo Nordisk.

Social media sites are bursting with these startups’ ads, everywhere from podcasts to Instagram. A search of Meta’s ad library finds 40,000 ads on Facebook and Instagram between the two firms.

The ads complement people’s own postings on social media: Numerous Facebook groups are devoted to the new type of drugs – some even focused on helping patients manage side effects, like changes in their bowel movements. The buzz is quantifiable: On TikTok, mentions of the new GLP-1 agonists tripled from last June to this June, according to an analysis by investment bankers at Morgan Stanley.

There’s now a feverish, expectant appetite for these medications among the startups’ clientele. Patients often complained that their friends had obtained a drug they weren’t offered, recalled Alexandra Coults, a former pharmacist consultant for Found. Ms. Coults said patients may have perceived some sort of bait-and-switch when in reality clinical reasons – like drug contraindications – guide prescribing decisions.

Patient expectations influence care, Ms. Coults said. Customers came in with ideas shaped by the culture of fad diets and New Year’s resolutions. “Quite a few people would sign up for 1 month and not continue.”

In interviews with KHN and in online complaints, patients also questioned the quality of care they received. Some said intake – which began by filling out a form and proceeded to an online visit with a doctor – was perfunctory. Once medication began, they said, requests for counseling about side effects were slow to be answered.

Jess Garrant, a Found patient, recalled that after she was prescribed zonisamide, a generic anticonvulsant that has shown some ability to help with weight loss, she felt “absolutely weird.”

“I was up all night and my thoughts were racing,” she wrote in a blog post. She developed sores in her mouth.

She sought advice and help from Found physicians, but their replies “weren’t quick.” Nonemergency communications are routed through the company’s portal.

It took a week to complete a switch of medications and have a new prescription arrive at her home, she said. Meanwhile, she said, she went to an urgent care clinic for the mouth sores.

Found frequently prescribes generic medications – often off label – rather than just the new GLP-1 agonists, company executives said in an interview. Found said older generics like zonisamide are more accessible than the GLP-1 agonists advertised on social media and their own website. Both Dr. Butsch and Dr. Stanford said they’ve prescribed zonisamide successfully. Dr. Butsch said ramping up dosage rapidly can increase the risk of side effects.

But Kim Boyd, MD, chief medical officer of competitor Calibrate, said the older drugs “just haven’t worked.”

Patients of both companies have critiqued online and in interviews the startups’ behavioral care – which experts across the board maintain is integral to successful weight loss treatment. But some patients felt they simply had canned advice.

Other patients said they had ups and downs with their coaches. Dana Crom, an attorney, said she had gone through many coaches with Calibrate. Some were good, effective cheerleaders; others, not so good. But when kinks in the program arose, she said, the coach wasn’t able to help her navigate them. While the coach can report trouble with medications or the app, it appears those reports are no more effective than messages sent through the portal, Ms. Crom said.

And what about when her yearlong subscription ends? Ms. Crom said she’d consider continuing with Calibrate.

Relationships with coaches, given the need to change behavior, are a critical element of the business models. Patients’ results depend “on how adherent they are to lifestyle changes,” said Found’s chief medical officer, Rehka Kumar, MD.

While the startups offer care to a larger geographic footprint, it’s not clear whether the demographics of their patient populations are different from those of the traditional bricks-and-mortar model. Calibrate’s patients are overwhelmingly White; over 8 in 10 have at least an undergraduate degree; and over 8 in 10 are women, according to the company.

And its earlier marketing strategies reflected that. The September 2020 “segmentation” document laid out three types of customers the company could hope to attract: perimenopausal or menopausal women, with income ranging from $75,000 to $150,000 a year; working mothers, with a similar income; and “men.”

Isabelle Kenyon, Calibrate’s CEO, said the company now hopes to expand its reach to partner with large employers, and that will help diversify its patients.

Patients will need to be convinced that the model – more affordable, more accessible – works for them. For her part, Ms. Garrant, who no longer is using Found, reflected on her experience, writing in her blog post that she was hoping for more follow-up and a more personal approach. “I don’t think it’s a helpful way to lose weight,” she said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Many Americans turn to the latest big idea to lose weight – fad diets, fitness crazes, dodgy herbs and pills, bariatric surgery, just to name a few. They’re rarely the magic solution people dream of.

Now a wave of startups offer access to a new category of drugs coupled with intensive behavioral coaching online. But already concerns are emerging.

These startups, spurred by hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from blue-chip venture capital firms, have signed up well over 100,000 patients and could reach millions more. These patients pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to access new drugs, called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists, along with online coaching to encourage healthy habits.

The startups initially positioned themselves in lofty terms. “This is the last weight-loss program you’ll try,” said a 2020 marketing analysis by startup Calibrate Health, in messaging designed to reach one of its target demographics, the “working mom.” (Company spokesperson Michelle Wellington said the document does not reflect Calibrate’s current marketing strategy.)

But while doctors and patients are intrigued by the new model, some customers complain online that reality is short of the buildup: They say they got canned advice and unresponsive clinicians – and some report they couldn’t get the newest drugs.

Calibrate Health, a New York City–based startup, reported earlier in 2022 it had served 20,000 people. Another startup, Found, headquartered in San Francisco, has served 135,000 patients since July 2020, CEO Sarah Jones Simmer said in an interview. Calibrate costs patients nearly $1,600 a year, not counting the price of drugs, which can hit nearly $1,500 monthly without insurance, according to drug price savings site GoodRx. (Insurers reimburse for GLP-1agonists in limited circumstances, patients said.) Found offers a 6-month plan for nearly $600, a company spokesperson said. (That price includes generic drugs, but not the newer GLP-1 agonists, like Wegovy.)

The two companies are beneficiaries of over $200 million in combined venture funding, according to tracking by Crunchbase, a repository of venture capital investments. The firms say they’re on the vanguard of weight care, both citing the influence of biology and other scientific factors as key ingredients to their approaches.

There’s potentially a big market for these startups. Just over 4 in 10 Americans are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, driving up their risk for cardiovascular conditions and type 2 diabetes. Effective medical treatments are elusive and hard to access.

Centers that provide this specialty care “are overwhelmed,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General in Boston, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard. Her own clinic has a wait list of 3,000.

Dr. Stanford, who said she has advised several of these telemedicine startups, is bullish on their potential.

Scott Butsch, MD, director of obesity medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said the startups can offer care with less judgment and stigma than in-person peers. They’re also more convenient.

Dr. Butsch, who learned about the model through consultancies, patients, and colleagues, wonders whether the startups are operating “to strategically find which patients respond to which drug.” He said they should coordinate well with behavioral specialists, as antidepressants or other medications may be driving weight gain. “Obesity is a complex disease and requires treatments that match its complexity. I think programs that do not have a multidisciplinary team are less comprehensive and, in the long term, less effective.”

The startups market a two-pronged product: first, the new class of GLP-1 agonists. While these medications are effective at provoking weight loss, Wegovy, one of two in this class specifically approved for this purpose, is in short supply because of manufacturing difficulties, according to its maker, Novo Nordisk. Others in the category can be prescribed off label. But doctors generally aren’t familiar with the medications, Stanford said. In theory, the startups can bridge some of those gaps: They offer more specialized, knowledgeable clinicians.

Then there’s the other prong: behavioral changes. The companies use televisits and online messaging with nutritionists or coaches to help patients incorporate new diet and exercise habits. The weight loss figures achieved by participants in clinical trials for the new drugs – up to 15% of body mass – were tied to such changes, according to Novo Nordisk.

Social media sites are bursting with these startups’ ads, everywhere from podcasts to Instagram. A search of Meta’s ad library finds 40,000 ads on Facebook and Instagram between the two firms.

The ads complement people’s own postings on social media: Numerous Facebook groups are devoted to the new type of drugs – some even focused on helping patients manage side effects, like changes in their bowel movements. The buzz is quantifiable: On TikTok, mentions of the new GLP-1 agonists tripled from last June to this June, according to an analysis by investment bankers at Morgan Stanley.

There’s now a feverish, expectant appetite for these medications among the startups’ clientele. Patients often complained that their friends had obtained a drug they weren’t offered, recalled Alexandra Coults, a former pharmacist consultant for Found. Ms. Coults said patients may have perceived some sort of bait-and-switch when in reality clinical reasons – like drug contraindications – guide prescribing decisions.

Patient expectations influence care, Ms. Coults said. Customers came in with ideas shaped by the culture of fad diets and New Year’s resolutions. “Quite a few people would sign up for 1 month and not continue.”

In interviews with KHN and in online complaints, patients also questioned the quality of care they received. Some said intake – which began by filling out a form and proceeded to an online visit with a doctor – was perfunctory. Once medication began, they said, requests for counseling about side effects were slow to be answered.

Jess Garrant, a Found patient, recalled that after she was prescribed zonisamide, a generic anticonvulsant that has shown some ability to help with weight loss, she felt “absolutely weird.”

“I was up all night and my thoughts were racing,” she wrote in a blog post. She developed sores in her mouth.

She sought advice and help from Found physicians, but their replies “weren’t quick.” Nonemergency communications are routed through the company’s portal.

It took a week to complete a switch of medications and have a new prescription arrive at her home, she said. Meanwhile, she said, she went to an urgent care clinic for the mouth sores.

Found frequently prescribes generic medications – often off label – rather than just the new GLP-1 agonists, company executives said in an interview. Found said older generics like zonisamide are more accessible than the GLP-1 agonists advertised on social media and their own website. Both Dr. Butsch and Dr. Stanford said they’ve prescribed zonisamide successfully. Dr. Butsch said ramping up dosage rapidly can increase the risk of side effects.

But Kim Boyd, MD, chief medical officer of competitor Calibrate, said the older drugs “just haven’t worked.”

Patients of both companies have critiqued online and in interviews the startups’ behavioral care – which experts across the board maintain is integral to successful weight loss treatment. But some patients felt they simply had canned advice.

Other patients said they had ups and downs with their coaches. Dana Crom, an attorney, said she had gone through many coaches with Calibrate. Some were good, effective cheerleaders; others, not so good. But when kinks in the program arose, she said, the coach wasn’t able to help her navigate them. While the coach can report trouble with medications or the app, it appears those reports are no more effective than messages sent through the portal, Ms. Crom said.

And what about when her yearlong subscription ends? Ms. Crom said she’d consider continuing with Calibrate.

Relationships with coaches, given the need to change behavior, are a critical element of the business models. Patients’ results depend “on how adherent they are to lifestyle changes,” said Found’s chief medical officer, Rehka Kumar, MD.

While the startups offer care to a larger geographic footprint, it’s not clear whether the demographics of their patient populations are different from those of the traditional bricks-and-mortar model. Calibrate’s patients are overwhelmingly White; over 8 in 10 have at least an undergraduate degree; and over 8 in 10 are women, according to the company.

And its earlier marketing strategies reflected that. The September 2020 “segmentation” document laid out three types of customers the company could hope to attract: perimenopausal or menopausal women, with income ranging from $75,000 to $150,000 a year; working mothers, with a similar income; and “men.”

Isabelle Kenyon, Calibrate’s CEO, said the company now hopes to expand its reach to partner with large employers, and that will help diversify its patients.

Patients will need to be convinced that the model – more affordable, more accessible – works for them. For her part, Ms. Garrant, who no longer is using Found, reflected on her experience, writing in her blog post that she was hoping for more follow-up and a more personal approach. “I don’t think it’s a helpful way to lose weight,” she said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Sham-controlled renal denervation trial for hypertension is a near miss

SPYRAL HTN–ON MED hits headwinds

CHICAGO – Renal denervation, relative to a sham procedure, was linked with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial, but several factors are likely to have worked in concert to prevent the study from meeting its primary endpoint.

Of these differences, probably none was more important than the substantially higher proportion of patients in the sham group that received additional BP-lowering medications over the course of the study, David E. Kandzari, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pivotal trial followed the previously completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pilot study, which did show a significant BP-lowering effect on antihypertensive medications followed radiofrequency denervation. In a recent update of the pilot study, the effect was persistent out to 3 years.

In the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED program, patients on their second screening visit were required to have a systolic pressure of between 140 and 170 mm Hg on 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) while taking up to three antihypertensive medications. Patients who entered the study were randomized to renal denervation or sham control while maintaining their baseline antihypertensive therapies.

The previously reported pilot study comprised 80 patients. The expansion pivotal trial added 257 more patients for a total cohort of 337 patients. The primary efficacy endpoint was based on a Bayesian analysis of change in 24-hour systolic ABPM at 6 months for those in the experimental arm versus those on medications alone. Participants from both the pilot and pivotal trials were included.

The prespecified definition of success for renal denervation was a 97.5% threshold for probability of superiority on the basis of this Bayesian analysis. However, the Bayesian analysis was distorted by differences in the pilot and expansion cohorts, which complicated the superiority calculation. As a result, the analysis only yielded a 51% probability of superiority, a level substantially below the predefined threshold.

Despite differences seen in BP control in favor of renal denervation, several factors were identified that likely contributed to the missed primary endpoint. One stood out.

“Significant differences in medication prescriptions were disproportionate in favor of the sham group,” reported Dr. Kandzari, chief of Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta. He said these differences, which were a violation of the protocol mandate, led to a “bias toward the null” for the primary outcome.

The failure to meet the primary outcome was particularly disappointing in the wake of the favorable pilot study and the SPYRAL HTN–OFF MED pivotal trial, which were both positive.

In the pilot study, which did not have a medication imbalance, a 7.3–mm Hg reduction (P = .004) in 24-hour ABPM was seen at 6 months. Relative reductions in office-based systolic pressure reductions for renal denervation versus sham were 6.6 mm Hg (P = .03) and 4.0 mm Hg (P = .03) for the pilot and expansions groups, respectively.

On the basis of a Win ratio derived from a hierarchical analysis of ABMP and medication burden reduction, the 1.50 advantage (P = .005) for the renal denervation arm in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was also compelling.

At study entry, the median number of medications was 1.9 in both the renal denervation and sham arms. At the end of 6 months, the median number of medications was unchanged in the experimental arm but rose to 2.1 (P = .01) in the sham group. Similarly, there was little change in the medication burden from the start to the end of the trial in the denervation group (2.8 vs. 3.0), but a statistically significant change in the sham group (2.9 vs. 3.5; P = .04).

Furthermore, the net percentage change of patients receiving medications favoring BP reduction over the course of the study did not differ between the experimental and control arms of the pilot cohort, but was more than 10 times higher among controls in the expansion group (1.9% vs. 21.8%; P < .0001).

Medication changes over the course of the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial were even greater in some specific subgroups. Among Black participants, for example, 14.2% of those randomized to renal denervation and 54.6% of those randomized to the sham group increased their antihypertensive therapies over the course of the study.

The COVID-19 epidemic is suspected of playing another role in the negative results, according to Dr. Kandzari. After a brief pause in enrollment, the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was resumed, but approximately 80% of the expansion cohort data were collected during this period. When compared, variances in office and 24-hour ABPM were observed for participants who were or were not evaluated during COVID.

“Significant differences in 24-hour ABPM patterns pre- and during COVID may reflect changes in patient behavior and lifestyle,” Dr. Kandzari speculated.

The data from this study differ from essentially all of the other studies in the SPYRAL HTN program as well as several other sham-controlled studies with renal denervation, according to Dr. Kandzari.

The AHA-invited discussant, Ajay J. Kirtane, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, largely agreed that several variables appeared to conspire against a positive result in this trial, but he zeroed in on the imbalance of antihypertensive medications.

“Any trial that attempts to show a difference between renal denervation and a sham procedure must insure that antihypertensive medications are the same in the two arms. They cannot be different,” he said.

As an active investigator in the field of renal denervation, Dr. Kirtane thinks the evidence does support a benefit from renal denervation, but he believes data are still needed to determine which patients are candidates.

“Renal denervation is not going to be a replacement for previous established therapies, but it will be an adjunct,” he predicted. The preponderance of evidence supports clinically meaningful reductions in BP with this approach, “but we need to determine who to consider [for this therapy] and to have realistic expectations about the degree of benefit.”

Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Ablative Solutions, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, Medtronic Cardiovascular, OrbusNeich, and Teleflex. Dr. Kirtane reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Systems, Cathworks, Chiesi, Medtronic, Opens, Philipps, Regeneron, ReCor Medical, Siemens, Spectranetics, and Zoll.

SPYRAL HTN–ON MED hits headwinds

SPYRAL HTN–ON MED hits headwinds

CHICAGO – Renal denervation, relative to a sham procedure, was linked with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial, but several factors are likely to have worked in concert to prevent the study from meeting its primary endpoint.

Of these differences, probably none was more important than the substantially higher proportion of patients in the sham group that received additional BP-lowering medications over the course of the study, David E. Kandzari, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pivotal trial followed the previously completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pilot study, which did show a significant BP-lowering effect on antihypertensive medications followed radiofrequency denervation. In a recent update of the pilot study, the effect was persistent out to 3 years.

In the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED program, patients on their second screening visit were required to have a systolic pressure of between 140 and 170 mm Hg on 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) while taking up to three antihypertensive medications. Patients who entered the study were randomized to renal denervation or sham control while maintaining their baseline antihypertensive therapies.

The previously reported pilot study comprised 80 patients. The expansion pivotal trial added 257 more patients for a total cohort of 337 patients. The primary efficacy endpoint was based on a Bayesian analysis of change in 24-hour systolic ABPM at 6 months for those in the experimental arm versus those on medications alone. Participants from both the pilot and pivotal trials were included.

The prespecified definition of success for renal denervation was a 97.5% threshold for probability of superiority on the basis of this Bayesian analysis. However, the Bayesian analysis was distorted by differences in the pilot and expansion cohorts, which complicated the superiority calculation. As a result, the analysis only yielded a 51% probability of superiority, a level substantially below the predefined threshold.

Despite differences seen in BP control in favor of renal denervation, several factors were identified that likely contributed to the missed primary endpoint. One stood out.

“Significant differences in medication prescriptions were disproportionate in favor of the sham group,” reported Dr. Kandzari, chief of Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta. He said these differences, which were a violation of the protocol mandate, led to a “bias toward the null” for the primary outcome.

The failure to meet the primary outcome was particularly disappointing in the wake of the favorable pilot study and the SPYRAL HTN–OFF MED pivotal trial, which were both positive.

In the pilot study, which did not have a medication imbalance, a 7.3–mm Hg reduction (P = .004) in 24-hour ABPM was seen at 6 months. Relative reductions in office-based systolic pressure reductions for renal denervation versus sham were 6.6 mm Hg (P = .03) and 4.0 mm Hg (P = .03) for the pilot and expansions groups, respectively.

On the basis of a Win ratio derived from a hierarchical analysis of ABMP and medication burden reduction, the 1.50 advantage (P = .005) for the renal denervation arm in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was also compelling.

At study entry, the median number of medications was 1.9 in both the renal denervation and sham arms. At the end of 6 months, the median number of medications was unchanged in the experimental arm but rose to 2.1 (P = .01) in the sham group. Similarly, there was little change in the medication burden from the start to the end of the trial in the denervation group (2.8 vs. 3.0), but a statistically significant change in the sham group (2.9 vs. 3.5; P = .04).

Furthermore, the net percentage change of patients receiving medications favoring BP reduction over the course of the study did not differ between the experimental and control arms of the pilot cohort, but was more than 10 times higher among controls in the expansion group (1.9% vs. 21.8%; P < .0001).

Medication changes over the course of the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial were even greater in some specific subgroups. Among Black participants, for example, 14.2% of those randomized to renal denervation and 54.6% of those randomized to the sham group increased their antihypertensive therapies over the course of the study.

The COVID-19 epidemic is suspected of playing another role in the negative results, according to Dr. Kandzari. After a brief pause in enrollment, the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was resumed, but approximately 80% of the expansion cohort data were collected during this period. When compared, variances in office and 24-hour ABPM were observed for participants who were or were not evaluated during COVID.

“Significant differences in 24-hour ABPM patterns pre- and during COVID may reflect changes in patient behavior and lifestyle,” Dr. Kandzari speculated.

The data from this study differ from essentially all of the other studies in the SPYRAL HTN program as well as several other sham-controlled studies with renal denervation, according to Dr. Kandzari.

The AHA-invited discussant, Ajay J. Kirtane, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, largely agreed that several variables appeared to conspire against a positive result in this trial, but he zeroed in on the imbalance of antihypertensive medications.

“Any trial that attempts to show a difference between renal denervation and a sham procedure must insure that antihypertensive medications are the same in the two arms. They cannot be different,” he said.

As an active investigator in the field of renal denervation, Dr. Kirtane thinks the evidence does support a benefit from renal denervation, but he believes data are still needed to determine which patients are candidates.

“Renal denervation is not going to be a replacement for previous established therapies, but it will be an adjunct,” he predicted. The preponderance of evidence supports clinically meaningful reductions in BP with this approach, “but we need to determine who to consider [for this therapy] and to have realistic expectations about the degree of benefit.”

Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Ablative Solutions, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, Medtronic Cardiovascular, OrbusNeich, and Teleflex. Dr. Kirtane reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Systems, Cathworks, Chiesi, Medtronic, Opens, Philipps, Regeneron, ReCor Medical, Siemens, Spectranetics, and Zoll.

CHICAGO – Renal denervation, relative to a sham procedure, was linked with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial, but several factors are likely to have worked in concert to prevent the study from meeting its primary endpoint.

Of these differences, probably none was more important than the substantially higher proportion of patients in the sham group that received additional BP-lowering medications over the course of the study, David E. Kandzari, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pivotal trial followed the previously completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pilot study, which did show a significant BP-lowering effect on antihypertensive medications followed radiofrequency denervation. In a recent update of the pilot study, the effect was persistent out to 3 years.

In the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED program, patients on their second screening visit were required to have a systolic pressure of between 140 and 170 mm Hg on 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) while taking up to three antihypertensive medications. Patients who entered the study were randomized to renal denervation or sham control while maintaining their baseline antihypertensive therapies.

The previously reported pilot study comprised 80 patients. The expansion pivotal trial added 257 more patients for a total cohort of 337 patients. The primary efficacy endpoint was based on a Bayesian analysis of change in 24-hour systolic ABPM at 6 months for those in the experimental arm versus those on medications alone. Participants from both the pilot and pivotal trials were included.

The prespecified definition of success for renal denervation was a 97.5% threshold for probability of superiority on the basis of this Bayesian analysis. However, the Bayesian analysis was distorted by differences in the pilot and expansion cohorts, which complicated the superiority calculation. As a result, the analysis only yielded a 51% probability of superiority, a level substantially below the predefined threshold.

Despite differences seen in BP control in favor of renal denervation, several factors were identified that likely contributed to the missed primary endpoint. One stood out.

“Significant differences in medication prescriptions were disproportionate in favor of the sham group,” reported Dr. Kandzari, chief of Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta. He said these differences, which were a violation of the protocol mandate, led to a “bias toward the null” for the primary outcome.

The failure to meet the primary outcome was particularly disappointing in the wake of the favorable pilot study and the SPYRAL HTN–OFF MED pivotal trial, which were both positive.

In the pilot study, which did not have a medication imbalance, a 7.3–mm Hg reduction (P = .004) in 24-hour ABPM was seen at 6 months. Relative reductions in office-based systolic pressure reductions for renal denervation versus sham were 6.6 mm Hg (P = .03) and 4.0 mm Hg (P = .03) for the pilot and expansions groups, respectively.

On the basis of a Win ratio derived from a hierarchical analysis of ABMP and medication burden reduction, the 1.50 advantage (P = .005) for the renal denervation arm in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was also compelling.

At study entry, the median number of medications was 1.9 in both the renal denervation and sham arms. At the end of 6 months, the median number of medications was unchanged in the experimental arm but rose to 2.1 (P = .01) in the sham group. Similarly, there was little change in the medication burden from the start to the end of the trial in the denervation group (2.8 vs. 3.0), but a statistically significant change in the sham group (2.9 vs. 3.5; P = .04).

Furthermore, the net percentage change of patients receiving medications favoring BP reduction over the course of the study did not differ between the experimental and control arms of the pilot cohort, but was more than 10 times higher among controls in the expansion group (1.9% vs. 21.8%; P < .0001).

Medication changes over the course of the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial were even greater in some specific subgroups. Among Black participants, for example, 14.2% of those randomized to renal denervation and 54.6% of those randomized to the sham group increased their antihypertensive therapies over the course of the study.

The COVID-19 epidemic is suspected of playing another role in the negative results, according to Dr. Kandzari. After a brief pause in enrollment, the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was resumed, but approximately 80% of the expansion cohort data were collected during this period. When compared, variances in office and 24-hour ABPM were observed for participants who were or were not evaluated during COVID.

“Significant differences in 24-hour ABPM patterns pre- and during COVID may reflect changes in patient behavior and lifestyle,” Dr. Kandzari speculated.

The data from this study differ from essentially all of the other studies in the SPYRAL HTN program as well as several other sham-controlled studies with renal denervation, according to Dr. Kandzari.

The AHA-invited discussant, Ajay J. Kirtane, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, largely agreed that several variables appeared to conspire against a positive result in this trial, but he zeroed in on the imbalance of antihypertensive medications.

“Any trial that attempts to show a difference between renal denervation and a sham procedure must insure that antihypertensive medications are the same in the two arms. They cannot be different,” he said.

As an active investigator in the field of renal denervation, Dr. Kirtane thinks the evidence does support a benefit from renal denervation, but he believes data are still needed to determine which patients are candidates.

“Renal denervation is not going to be a replacement for previous established therapies, but it will be an adjunct,” he predicted. The preponderance of evidence supports clinically meaningful reductions in BP with this approach, “but we need to determine who to consider [for this therapy] and to have realistic expectations about the degree of benefit.”

Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Ablative Solutions, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, Medtronic Cardiovascular, OrbusNeich, and Teleflex. Dr. Kirtane reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Systems, Cathworks, Chiesi, Medtronic, Opens, Philipps, Regeneron, ReCor Medical, Siemens, Spectranetics, and Zoll.

AT AHA 2022

Starting a podcast

In my last column, I discussed . At this writing (November 2022), more than 600 million blogs are online, compared with about 2 million podcasts, and relatively few of them are run by physicians. With podcasts, you have a better chance of standing out in a crowded online world.

Starting a podcast is not difficult, but there are several steps you need to go through before launching one.

As with blogging, start by outlining a long-range plan. Your general topic will probably be your specialty, but you will need to narrow your focus to a few specific subjects, such as the problems you see most often, or a subspecialty that you concentrate on. You can always expand your topic later, as you get more popular. Choose a name for your podcast, and purchase a domain name that accurately describes it.

You will also need to choose a hosting service. Numerous inexpensive hosting platforms are available, and a simple Google search will find them for you. Many of them provide free learning materials, helpful creative tools, and customer support to get you through the confusing technical aspects. They can also help you choose a music introduction (to add a bit of polish), and help you piece together your audio segments. Buzzsprout, RSS.com, and Podbean get good reviews on many sites. (As always, I have no financial interest in any company or service mentioned herein.)

Hosting services can assist you in creating a template – a framework that you can reuse each time you record an episode – containing your intro and exit music, tracks for your conversations, etc. This will make your podcasts instantly recognizable each time your listeners tune in.

Many podcasting experts recommend recruiting a co-host. This can be an associate within your practice, a friend who practices elsewhere, or perhaps a resident in an academic setting. You will be able to spread the workload of creating, editing, and promoting. Plus, it is much easier to generate interesting content when two people are having a conversation, rather than one person lecturing from a prepared script. You might also consider having multiple co-hosts, either to expand episodes into group discussions, or to take turns working with you in covering different subjects.

How long you make your podcast is entirely up to you. Some consultants recommend specific time frames, such as 5 minutes (because that’s an average attention span), or 28 minutes (because that’s the average driving commute time). There are short podcasts and long ones; whatever works for you is fine, as long as you don’t drift off the topic. Furthermore, no one says they must all be the same length; when you are finished talking, you are done. And no one says you must stick with one subject throughout. Combining several short segments might hold more listeners’ interest and will make it easier to share small clips on social media.

Content guidelines are similar to those for blogs. Give people content that will be of interest or benefit to them. Talk about subjects – medical and otherwise – that are relevant to your practice or are prominent in the news.

As with blogs, try to avoid polarizing political discussions, and while it’s fine to discuss treatments and procedures that you offer, aggressive solicitation tends to make viewers look elsewhere. Keep any medical advice in general terms; don’t portray any specific patients as examples.

When your podcast is ready, your hosting platform will show you how to submit it to iTunes, and how to submit your podcast RSS feed to other podcast directories. As you upload new episodes, your host will automatically update your RSS feed, so that any directory you are listed on will receive the new episode.

Once you are uploaded, you can use your host’s social sharing tools to spread the word. As with blogs, use social media, such as your practice’s Facebook page, to push podcast updates into patients’ feeds and track relevant Twitter hashtags to find online communities that might be interested in your subject matter. You should also find your episode embed code (which your host will have) and place it in a prominent place on your website so patients can listen directly from there.

Transcriptions are another excellent promotional tool. Search engines will “read” your podcasts and list them in searches. Some podcast hosts will do transcribing for a fee, but there are independent transcription services as well.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In my last column, I discussed . At this writing (November 2022), more than 600 million blogs are online, compared with about 2 million podcasts, and relatively few of them are run by physicians. With podcasts, you have a better chance of standing out in a crowded online world.

Starting a podcast is not difficult, but there are several steps you need to go through before launching one.

As with blogging, start by outlining a long-range plan. Your general topic will probably be your specialty, but you will need to narrow your focus to a few specific subjects, such as the problems you see most often, or a subspecialty that you concentrate on. You can always expand your topic later, as you get more popular. Choose a name for your podcast, and purchase a domain name that accurately describes it.

You will also need to choose a hosting service. Numerous inexpensive hosting platforms are available, and a simple Google search will find them for you. Many of them provide free learning materials, helpful creative tools, and customer support to get you through the confusing technical aspects. They can also help you choose a music introduction (to add a bit of polish), and help you piece together your audio segments. Buzzsprout, RSS.com, and Podbean get good reviews on many sites. (As always, I have no financial interest in any company or service mentioned herein.)

Hosting services can assist you in creating a template – a framework that you can reuse each time you record an episode – containing your intro and exit music, tracks for your conversations, etc. This will make your podcasts instantly recognizable each time your listeners tune in.

Many podcasting experts recommend recruiting a co-host. This can be an associate within your practice, a friend who practices elsewhere, or perhaps a resident in an academic setting. You will be able to spread the workload of creating, editing, and promoting. Plus, it is much easier to generate interesting content when two people are having a conversation, rather than one person lecturing from a prepared script. You might also consider having multiple co-hosts, either to expand episodes into group discussions, or to take turns working with you in covering different subjects.

How long you make your podcast is entirely up to you. Some consultants recommend specific time frames, such as 5 minutes (because that’s an average attention span), or 28 minutes (because that’s the average driving commute time). There are short podcasts and long ones; whatever works for you is fine, as long as you don’t drift off the topic. Furthermore, no one says they must all be the same length; when you are finished talking, you are done. And no one says you must stick with one subject throughout. Combining several short segments might hold more listeners’ interest and will make it easier to share small clips on social media.

Content guidelines are similar to those for blogs. Give people content that will be of interest or benefit to them. Talk about subjects – medical and otherwise – that are relevant to your practice or are prominent in the news.

As with blogs, try to avoid polarizing political discussions, and while it’s fine to discuss treatments and procedures that you offer, aggressive solicitation tends to make viewers look elsewhere. Keep any medical advice in general terms; don’t portray any specific patients as examples.

When your podcast is ready, your hosting platform will show you how to submit it to iTunes, and how to submit your podcast RSS feed to other podcast directories. As you upload new episodes, your host will automatically update your RSS feed, so that any directory you are listed on will receive the new episode.

Once you are uploaded, you can use your host’s social sharing tools to spread the word. As with blogs, use social media, such as your practice’s Facebook page, to push podcast updates into patients’ feeds and track relevant Twitter hashtags to find online communities that might be interested in your subject matter. You should also find your episode embed code (which your host will have) and place it in a prominent place on your website so patients can listen directly from there.

Transcriptions are another excellent promotional tool. Search engines will “read” your podcasts and list them in searches. Some podcast hosts will do transcribing for a fee, but there are independent transcription services as well.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In my last column, I discussed . At this writing (November 2022), more than 600 million blogs are online, compared with about 2 million podcasts, and relatively few of them are run by physicians. With podcasts, you have a better chance of standing out in a crowded online world.

Starting a podcast is not difficult, but there are several steps you need to go through before launching one.

As with blogging, start by outlining a long-range plan. Your general topic will probably be your specialty, but you will need to narrow your focus to a few specific subjects, such as the problems you see most often, or a subspecialty that you concentrate on. You can always expand your topic later, as you get more popular. Choose a name for your podcast, and purchase a domain name that accurately describes it.

You will also need to choose a hosting service. Numerous inexpensive hosting platforms are available, and a simple Google search will find them for you. Many of them provide free learning materials, helpful creative tools, and customer support to get you through the confusing technical aspects. They can also help you choose a music introduction (to add a bit of polish), and help you piece together your audio segments. Buzzsprout, RSS.com, and Podbean get good reviews on many sites. (As always, I have no financial interest in any company or service mentioned herein.)

Hosting services can assist you in creating a template – a framework that you can reuse each time you record an episode – containing your intro and exit music, tracks for your conversations, etc. This will make your podcasts instantly recognizable each time your listeners tune in.

Many podcasting experts recommend recruiting a co-host. This can be an associate within your practice, a friend who practices elsewhere, or perhaps a resident in an academic setting. You will be able to spread the workload of creating, editing, and promoting. Plus, it is much easier to generate interesting content when two people are having a conversation, rather than one person lecturing from a prepared script. You might also consider having multiple co-hosts, either to expand episodes into group discussions, or to take turns working with you in covering different subjects.

How long you make your podcast is entirely up to you. Some consultants recommend specific time frames, such as 5 minutes (because that’s an average attention span), or 28 minutes (because that’s the average driving commute time). There are short podcasts and long ones; whatever works for you is fine, as long as you don’t drift off the topic. Furthermore, no one says they must all be the same length; when you are finished talking, you are done. And no one says you must stick with one subject throughout. Combining several short segments might hold more listeners’ interest and will make it easier to share small clips on social media.

Content guidelines are similar to those for blogs. Give people content that will be of interest or benefit to them. Talk about subjects – medical and otherwise – that are relevant to your practice or are prominent in the news.

As with blogs, try to avoid polarizing political discussions, and while it’s fine to discuss treatments and procedures that you offer, aggressive solicitation tends to make viewers look elsewhere. Keep any medical advice in general terms; don’t portray any specific patients as examples.

When your podcast is ready, your hosting platform will show you how to submit it to iTunes, and how to submit your podcast RSS feed to other podcast directories. As you upload new episodes, your host will automatically update your RSS feed, so that any directory you are listed on will receive the new episode.

Once you are uploaded, you can use your host’s social sharing tools to spread the word. As with blogs, use social media, such as your practice’s Facebook page, to push podcast updates into patients’ feeds and track relevant Twitter hashtags to find online communities that might be interested in your subject matter. You should also find your episode embed code (which your host will have) and place it in a prominent place on your website so patients can listen directly from there.

Transcriptions are another excellent promotional tool. Search engines will “read” your podcasts and list them in searches. Some podcast hosts will do transcribing for a fee, but there are independent transcription services as well.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

‘Key cause’ of type 2 diabetes identified