User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Medicaid expansion boosts diabetes diagnoses and treatment rates

The expansion of Medicaid in certain states is associated with an increase in the number of individuals being diagnosed with diabetes and receiving early treatment, researchers say.

The number of Medicaid patients with newly diagnosed diabetes increased by 23% from 2013 to 2014 in the 26 states that expanded Medicaid, compared to 0.4% in the states that did not, judging from an analysis of data from a national private clinical laboratory database, encompassing 434,288 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes.

Across 50 states and the District of Columbia, there was an overall increase of 13% in the number of Medicaid-enrolled patients newly diagnosed with diabetes, which was similar regardless of age or gender, according to a paper published online in Diabetes Care.

“Beyond diabetes, the trends we observed in the current study are likely to affect diagnosis of other chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and chronic kidney disease,” wrote Dr. Harvey W. Kaufman of Quest Diagnostics, and his coauthors (Diabetes Care 2015;38:833-7 [doi:10.2337/dc14-2334]).

One author reported research support, consultancies, and lecture fees from private industry. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

The expansion of Medicaid in certain states is associated with an increase in the number of individuals being diagnosed with diabetes and receiving early treatment, researchers say.

The number of Medicaid patients with newly diagnosed diabetes increased by 23% from 2013 to 2014 in the 26 states that expanded Medicaid, compared to 0.4% in the states that did not, judging from an analysis of data from a national private clinical laboratory database, encompassing 434,288 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes.

Across 50 states and the District of Columbia, there was an overall increase of 13% in the number of Medicaid-enrolled patients newly diagnosed with diabetes, which was similar regardless of age or gender, according to a paper published online in Diabetes Care.

“Beyond diabetes, the trends we observed in the current study are likely to affect diagnosis of other chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and chronic kidney disease,” wrote Dr. Harvey W. Kaufman of Quest Diagnostics, and his coauthors (Diabetes Care 2015;38:833-7 [doi:10.2337/dc14-2334]).

One author reported research support, consultancies, and lecture fees from private industry. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

The expansion of Medicaid in certain states is associated with an increase in the number of individuals being diagnosed with diabetes and receiving early treatment, researchers say.

The number of Medicaid patients with newly diagnosed diabetes increased by 23% from 2013 to 2014 in the 26 states that expanded Medicaid, compared to 0.4% in the states that did not, judging from an analysis of data from a national private clinical laboratory database, encompassing 434,288 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes.

Across 50 states and the District of Columbia, there was an overall increase of 13% in the number of Medicaid-enrolled patients newly diagnosed with diabetes, which was similar regardless of age or gender, according to a paper published online in Diabetes Care.

“Beyond diabetes, the trends we observed in the current study are likely to affect diagnosis of other chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and chronic kidney disease,” wrote Dr. Harvey W. Kaufman of Quest Diagnostics, and his coauthors (Diabetes Care 2015;38:833-7 [doi:10.2337/dc14-2334]).

One author reported research support, consultancies, and lecture fees from private industry. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Key clinical point: The expansion of Medicaid in certain states is associated with an increase in the number of individuals being diagnosed with diabetes and receiving early treatment.

Major finding: The number of Medicaid-enrolled patients with newly diagnosed diabetes increased by 23% from 2013 to 2014 in the 26 states that expanded Medicaid, compared to 0.4% in the states that did not.

Data source: Analysis of private clinical laboratory data for 434,288 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes.

Disclosures: One author reported research support, consultancies, and lecture fees from private industry. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

VIDEO: NAFLD increasingly causing U.S. hepatocellular carcinomas

VIENNA – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) now stands as the second most common cause of U.S. cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, and with highly effective drug regimens now sharply dropping the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection, NAFLD – a complication of obesity – is poised to snag the top spot, Dr. Zobair Younossi said in a video interview at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

In an analysis that combined U.S. national cancer registry data collected by the National Cancer Institute and morbidity diagnostic codes collected by Medicare, Dr. Younossi calculated that, during 2004-2009 among U.S. adults covered by Medicare, 24% of patients newly diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) had NAFLD as their pre-existing chronic liver disease, compared with 48% who had hepatitis C virus infection as their trigger. The third most common cause of HCC was alcoholic liver disease (14%), followed by hepatitis B virus infection (8%).

Dr. Younossi’s analysis also included survival data for each HCC case in the first year following diagnosis, which showed that NAFLD-associated cases also were deadlier, linking with a statistically significant 20% increase in mortality compared with HCC associated with other causes. Quicker lethality of NAFLD-linked HCC is probably due to the more advanced stage at diagnosis, he said.

The findings highlight the need for improved surveillance in these patients, a process complicated by the challenge of imaging the liver in obese patients, said Dr. Younossi, chairman of medicine and head of the Center for Liver Diseases at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va.

Dr. Younossi has been a consultant to Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Intercept, and Salix.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIENNA – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) now stands as the second most common cause of U.S. cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, and with highly effective drug regimens now sharply dropping the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection, NAFLD – a complication of obesity – is poised to snag the top spot, Dr. Zobair Younossi said in a video interview at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

In an analysis that combined U.S. national cancer registry data collected by the National Cancer Institute and morbidity diagnostic codes collected by Medicare, Dr. Younossi calculated that, during 2004-2009 among U.S. adults covered by Medicare, 24% of patients newly diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) had NAFLD as their pre-existing chronic liver disease, compared with 48% who had hepatitis C virus infection as their trigger. The third most common cause of HCC was alcoholic liver disease (14%), followed by hepatitis B virus infection (8%).

Dr. Younossi’s analysis also included survival data for each HCC case in the first year following diagnosis, which showed that NAFLD-associated cases also were deadlier, linking with a statistically significant 20% increase in mortality compared with HCC associated with other causes. Quicker lethality of NAFLD-linked HCC is probably due to the more advanced stage at diagnosis, he said.

The findings highlight the need for improved surveillance in these patients, a process complicated by the challenge of imaging the liver in obese patients, said Dr. Younossi, chairman of medicine and head of the Center for Liver Diseases at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va.

Dr. Younossi has been a consultant to Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Intercept, and Salix.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIENNA – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) now stands as the second most common cause of U.S. cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, and with highly effective drug regimens now sharply dropping the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection, NAFLD – a complication of obesity – is poised to snag the top spot, Dr. Zobair Younossi said in a video interview at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

In an analysis that combined U.S. national cancer registry data collected by the National Cancer Institute and morbidity diagnostic codes collected by Medicare, Dr. Younossi calculated that, during 2004-2009 among U.S. adults covered by Medicare, 24% of patients newly diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) had NAFLD as their pre-existing chronic liver disease, compared with 48% who had hepatitis C virus infection as their trigger. The third most common cause of HCC was alcoholic liver disease (14%), followed by hepatitis B virus infection (8%).

Dr. Younossi’s analysis also included survival data for each HCC case in the first year following diagnosis, which showed that NAFLD-associated cases also were deadlier, linking with a statistically significant 20% increase in mortality compared with HCC associated with other causes. Quicker lethality of NAFLD-linked HCC is probably due to the more advanced stage at diagnosis, he said.

The findings highlight the need for improved surveillance in these patients, a process complicated by the challenge of imaging the liver in obese patients, said Dr. Younossi, chairman of medicine and head of the Center for Liver Diseases at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va.

Dr. Younossi has been a consultant to Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Intercept, and Salix.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

Metformin underprescribed in adults with prediabetes

Less than 4% of adults with prediabetes are prescribed metformin for diabetes prevention, despite the fact that the condition affects one in three Americans, researchers said.

A 3-year retrospective cohort analysis of health insurance data from 17,352 working-age adults with prediabetes showed that only 3.7% had a prescription claim for metformin, although that figure rose to 7.8% among the subset of patients with a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2 or those with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Tannaz Moin and her associates defined prediabetes as either a hemoglobin A1c level of 5.7% to 6.4%, a fasting plasma glucose level of 5.55 to 6.94 mmol/L (100-125 mg/dL), or a 2-hour plasma glucose level of 7.77 to 11.04 mmol/L (140-199 mg/dL) on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Women were almost twice as likely to receive a metformin prescription as were men (4.8% versus 2.8%), while obese individuals and those with two or more comorbid conditions also were more likely to be prescribed metformin, according to findings published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162:542-8).

“Our findings indicate that metformin is rarely prescribed for diabetes prevention despite a strong evidence base in the literature for more than 10 years and inclusion in practice guidelines for more than 6 years,” wrote Dr. Moin of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates. “This is a potential gap in the approach to prediabetes management and a significant missed opportunity for diabetes prevention in patients at highest risk.”

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One of the study authors was an employee of UnitedHealthcare.

Less than 4% of adults with prediabetes are prescribed metformin for diabetes prevention, despite the fact that the condition affects one in three Americans, researchers said.

A 3-year retrospective cohort analysis of health insurance data from 17,352 working-age adults with prediabetes showed that only 3.7% had a prescription claim for metformin, although that figure rose to 7.8% among the subset of patients with a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2 or those with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Tannaz Moin and her associates defined prediabetes as either a hemoglobin A1c level of 5.7% to 6.4%, a fasting plasma glucose level of 5.55 to 6.94 mmol/L (100-125 mg/dL), or a 2-hour plasma glucose level of 7.77 to 11.04 mmol/L (140-199 mg/dL) on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Women were almost twice as likely to receive a metformin prescription as were men (4.8% versus 2.8%), while obese individuals and those with two or more comorbid conditions also were more likely to be prescribed metformin, according to findings published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162:542-8).

“Our findings indicate that metformin is rarely prescribed for diabetes prevention despite a strong evidence base in the literature for more than 10 years and inclusion in practice guidelines for more than 6 years,” wrote Dr. Moin of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates. “This is a potential gap in the approach to prediabetes management and a significant missed opportunity for diabetes prevention in patients at highest risk.”

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One of the study authors was an employee of UnitedHealthcare.

Less than 4% of adults with prediabetes are prescribed metformin for diabetes prevention, despite the fact that the condition affects one in three Americans, researchers said.

A 3-year retrospective cohort analysis of health insurance data from 17,352 working-age adults with prediabetes showed that only 3.7% had a prescription claim for metformin, although that figure rose to 7.8% among the subset of patients with a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2 or those with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Tannaz Moin and her associates defined prediabetes as either a hemoglobin A1c level of 5.7% to 6.4%, a fasting plasma glucose level of 5.55 to 6.94 mmol/L (100-125 mg/dL), or a 2-hour plasma glucose level of 7.77 to 11.04 mmol/L (140-199 mg/dL) on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Women were almost twice as likely to receive a metformin prescription as were men (4.8% versus 2.8%), while obese individuals and those with two or more comorbid conditions also were more likely to be prescribed metformin, according to findings published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162:542-8).

“Our findings indicate that metformin is rarely prescribed for diabetes prevention despite a strong evidence base in the literature for more than 10 years and inclusion in practice guidelines for more than 6 years,” wrote Dr. Moin of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates. “This is a potential gap in the approach to prediabetes management and a significant missed opportunity for diabetes prevention in patients at highest risk.”

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One of the study authors was an employee of UnitedHealthcare.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adults with prediabetes are unlikely to be prescribed metformin, though women and obese patients are more likely to receive a prescription.

Major finding: Only 3.7% of adults with prediabetes were prescribed metformin to prevent diabetes in a study from 2010 to 2012.

Data source: 3-year retrospective cohort analysis of health insurance data from 17,352 working-age adults with prediabetes.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One of the study authors was an employee of UnitedHealthcare.

Novel agent lowers LDL more than ezetimibe

SAN DIEGO– ETC-1002, an oral LDL-lowering drug with a novel mechanism of action, decreased LDL by up to 30% more than did ezetimibe in a large phase IIb study.

The 348-patient trial also showed that ETC-1002 and ezetimibe are additive in their LDL-lowering effects, with the combination reducing LDL levels by up to 48%, compared with baseline, Dr. Paul Thompson reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Importantly, the investigational drug and ezetimibe, which is marketed in the United States as Zetia, showed similarly favorable safety and tolerability profiles. And ETC-1002 proved equally effective at LDL-lowering in statin-intolerant and -tolerant patients, noted Dr. Thompson, director of cardiology at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Storrs.

ETC-1002 is a first-in-class oral modulator of the enzymes adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase and adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase. These dual mechanisms of action cause the liver to take up LDL cholesterol from the blood.

Asked how he sees the drug potentially fitting into the dyslipidemia treatment landscape, which could soon include the eagerly anticipated, super-potent LDL-lowering proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, Dr. Thompson pointed out that there have been no cardiovascular outcome studies of ETC-1002.

“Without outcomes data in terms of survival, I’d say ETC-1002 will be an additional drug in our armamentarium for treating high cholesterol levels. And so far, we’ve generally seen that reductions in LDL cholesterol result in reductions in clinical events. I would think that this drug would be a way to treat statin-intolerant or -tolerant patients in combination with ezetimibe or alone. And where it fits in will depend somewhat on the cost of the medication,” he said.

The double-blind, phase IIb study randomized 177 hypercholesterolemic patients with muscle-related statin intolerance and 171 without statin intolerance to 12 weeks of once-daily ETC-1002 at 120 mg or 180 mg, ezetimibe at 10 mg, the combination of ETC-1002 at 120 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg, or ETC-1002 at 180 and ezetimibe 10 mg.

ETC-1002 at the lower dose reduced LDL by a mean of 27% from a baseline of 165 mg/dL. The 180-mg dose decreased LDL by 30%. In contrast, ezetimibe monotherapy lowered LDL by 21%, a significantly lesser effect than with either dose of ETC-1002. The effects of combination therapy were additive: ETC-1002 at 120 mg plus ezetimibe reduced LDL by 43%, compared with baseline, while ETC-1002 at 180 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg lowered LDL by 48%.

ETC-1002 also improved other atherogenic lipids and markers of systemic inflammation. For example, apolipoprotein B decreased by 30% with ETC-1002 at 120 mg, 40% with ETC-1002 at 180 mg, and 10% with ezetimibe at 10 mg. Similarly, C-reactive protein levels fell by 30% and 40% with low- and higher-dose ETC-1002, compared with a 10% reduction with ezetimibe.

Muscle-related complaints were several-fold more common in the group with a history of statin intolerance as defined by the Food and Drug Administration – namely, muscle-related intolerance to at least two statins, including one at the lowest approved dose. However, rates of discontinuation from drug-related adverse events were similarly low at 3%-8% across the five treatment arms.

“I think the take-home message is that the safety profile of the drug looks good,” the cardiologist said.

No significant changes were seen in body weight, blood glucose levels, or blood pressure during the 12-week study.

Dr. Thompson reported receiving a research grant from Esperion Therapeutics, the study sponsor. He serves as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Sanofi-Aventis.

SAN DIEGO– ETC-1002, an oral LDL-lowering drug with a novel mechanism of action, decreased LDL by up to 30% more than did ezetimibe in a large phase IIb study.

The 348-patient trial also showed that ETC-1002 and ezetimibe are additive in their LDL-lowering effects, with the combination reducing LDL levels by up to 48%, compared with baseline, Dr. Paul Thompson reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Importantly, the investigational drug and ezetimibe, which is marketed in the United States as Zetia, showed similarly favorable safety and tolerability profiles. And ETC-1002 proved equally effective at LDL-lowering in statin-intolerant and -tolerant patients, noted Dr. Thompson, director of cardiology at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Storrs.

ETC-1002 is a first-in-class oral modulator of the enzymes adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase and adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase. These dual mechanisms of action cause the liver to take up LDL cholesterol from the blood.

Asked how he sees the drug potentially fitting into the dyslipidemia treatment landscape, which could soon include the eagerly anticipated, super-potent LDL-lowering proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, Dr. Thompson pointed out that there have been no cardiovascular outcome studies of ETC-1002.

“Without outcomes data in terms of survival, I’d say ETC-1002 will be an additional drug in our armamentarium for treating high cholesterol levels. And so far, we’ve generally seen that reductions in LDL cholesterol result in reductions in clinical events. I would think that this drug would be a way to treat statin-intolerant or -tolerant patients in combination with ezetimibe or alone. And where it fits in will depend somewhat on the cost of the medication,” he said.

The double-blind, phase IIb study randomized 177 hypercholesterolemic patients with muscle-related statin intolerance and 171 without statin intolerance to 12 weeks of once-daily ETC-1002 at 120 mg or 180 mg, ezetimibe at 10 mg, the combination of ETC-1002 at 120 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg, or ETC-1002 at 180 and ezetimibe 10 mg.

ETC-1002 at the lower dose reduced LDL by a mean of 27% from a baseline of 165 mg/dL. The 180-mg dose decreased LDL by 30%. In contrast, ezetimibe monotherapy lowered LDL by 21%, a significantly lesser effect than with either dose of ETC-1002. The effects of combination therapy were additive: ETC-1002 at 120 mg plus ezetimibe reduced LDL by 43%, compared with baseline, while ETC-1002 at 180 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg lowered LDL by 48%.

ETC-1002 also improved other atherogenic lipids and markers of systemic inflammation. For example, apolipoprotein B decreased by 30% with ETC-1002 at 120 mg, 40% with ETC-1002 at 180 mg, and 10% with ezetimibe at 10 mg. Similarly, C-reactive protein levels fell by 30% and 40% with low- and higher-dose ETC-1002, compared with a 10% reduction with ezetimibe.

Muscle-related complaints were several-fold more common in the group with a history of statin intolerance as defined by the Food and Drug Administration – namely, muscle-related intolerance to at least two statins, including one at the lowest approved dose. However, rates of discontinuation from drug-related adverse events were similarly low at 3%-8% across the five treatment arms.

“I think the take-home message is that the safety profile of the drug looks good,” the cardiologist said.

No significant changes were seen in body weight, blood glucose levels, or blood pressure during the 12-week study.

Dr. Thompson reported receiving a research grant from Esperion Therapeutics, the study sponsor. He serves as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Sanofi-Aventis.

SAN DIEGO– ETC-1002, an oral LDL-lowering drug with a novel mechanism of action, decreased LDL by up to 30% more than did ezetimibe in a large phase IIb study.

The 348-patient trial also showed that ETC-1002 and ezetimibe are additive in their LDL-lowering effects, with the combination reducing LDL levels by up to 48%, compared with baseline, Dr. Paul Thompson reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Importantly, the investigational drug and ezetimibe, which is marketed in the United States as Zetia, showed similarly favorable safety and tolerability profiles. And ETC-1002 proved equally effective at LDL-lowering in statin-intolerant and -tolerant patients, noted Dr. Thompson, director of cardiology at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Storrs.

ETC-1002 is a first-in-class oral modulator of the enzymes adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase and adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase. These dual mechanisms of action cause the liver to take up LDL cholesterol from the blood.

Asked how he sees the drug potentially fitting into the dyslipidemia treatment landscape, which could soon include the eagerly anticipated, super-potent LDL-lowering proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, Dr. Thompson pointed out that there have been no cardiovascular outcome studies of ETC-1002.

“Without outcomes data in terms of survival, I’d say ETC-1002 will be an additional drug in our armamentarium for treating high cholesterol levels. And so far, we’ve generally seen that reductions in LDL cholesterol result in reductions in clinical events. I would think that this drug would be a way to treat statin-intolerant or -tolerant patients in combination with ezetimibe or alone. And where it fits in will depend somewhat on the cost of the medication,” he said.

The double-blind, phase IIb study randomized 177 hypercholesterolemic patients with muscle-related statin intolerance and 171 without statin intolerance to 12 weeks of once-daily ETC-1002 at 120 mg or 180 mg, ezetimibe at 10 mg, the combination of ETC-1002 at 120 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg, or ETC-1002 at 180 and ezetimibe 10 mg.

ETC-1002 at the lower dose reduced LDL by a mean of 27% from a baseline of 165 mg/dL. The 180-mg dose decreased LDL by 30%. In contrast, ezetimibe monotherapy lowered LDL by 21%, a significantly lesser effect than with either dose of ETC-1002. The effects of combination therapy were additive: ETC-1002 at 120 mg plus ezetimibe reduced LDL by 43%, compared with baseline, while ETC-1002 at 180 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg lowered LDL by 48%.

ETC-1002 also improved other atherogenic lipids and markers of systemic inflammation. For example, apolipoprotein B decreased by 30% with ETC-1002 at 120 mg, 40% with ETC-1002 at 180 mg, and 10% with ezetimibe at 10 mg. Similarly, C-reactive protein levels fell by 30% and 40% with low- and higher-dose ETC-1002, compared with a 10% reduction with ezetimibe.

Muscle-related complaints were several-fold more common in the group with a history of statin intolerance as defined by the Food and Drug Administration – namely, muscle-related intolerance to at least two statins, including one at the lowest approved dose. However, rates of discontinuation from drug-related adverse events were similarly low at 3%-8% across the five treatment arms.

“I think the take-home message is that the safety profile of the drug looks good,” the cardiologist said.

No significant changes were seen in body weight, blood glucose levels, or blood pressure during the 12-week study.

Dr. Thompson reported receiving a research grant from Esperion Therapeutics, the study sponsor. He serves as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Sanofi-Aventis.

AT ACC 15

Key clinical point: A novel investigational LDL cholesterol–lowering agent showed greater lipid lowering than did ezetimibe along with similar safety and tolerability.

Major finding: ETC-1002 at 180 mg once daily lowered LDL by a mean of 30%, while ezetimibe at 10 mg/day decreased LDL by 21%.

Data source: This phase IIb, double-blind, randomized, 12-week trial included 348 hypercholesterolemic patients, roughly half with a history of statin intolerance.

Disclosures: The study presenter received a research grant from Esperion Therapeutics, which sponsored the trial.

AACR: Metformin survival benefit shaky in pancreatic cancer

A detailed survival analysis questions the rationale behind use of the diabetes drug metformin to improve pancreatic cancer survival.

Several epidemiologic studies have shown that metformin use reduces cancer mortality, leading the diabetes drug to be included in the treatment arm of 20 open clinical trials in recalcitrant cancers, Dr. Roongruedee Chaiteerakij reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The problem is that the epidemiologic studies commonly classified metformin use as simply “ever or never,” which may have introduced unintended biases.

To address these potential biases, Dr. Chaiteerakij and her colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., analyzed 1,360 patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and diabetes between 2000 and 2011 in the database of the Mayo Clinic Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Pancreatic Cancer. More than half (59%) were male; the average age was 67 years.

A total of 380 patients were excluded for surgically induced diabetes, unknown diabetes duration, and PDAC diagnosis more than 90 days prior to the first Mayo visit. This left 980 patients in the final cohort.

An initial analysis using the ever vs. never classification suggested that metformin use was associated with marginally improved survival in patients with PDAC (median 9.9 months ever use vs. 8.9 months never use; unadjusted hazard ratio, 0.9; P = .08), Dr. Chaiteerakij said.

The association was most significant in locally advanced PDAC patients (10.2 months ever use vs. 8.1 months never use; unadjusted HR 0.7; P = .006).

The investigators then performed a subanalysis of locally advanced PDAC patients, this time stratified by timing of metformin initiation: never used (reference group), started more than 1 year before PDAC diagnosis, started within 1 year before PDAC diagnosis, started less than 30 days post PDAC diagnosis, and started more than 30 days post PDAC diagnosis.

Median survival was 8.1, 10.1, and 9.9 months in the first three groups, increasing to 11.4 months and 13.7 months in the two groups that started metformin after PDAC diagnosis, Dr. Chaiteerakij reported.

Hazard ratios for the four metformin groups were 0.7, 0.6, 0.9, and 0.5, after adjustment for age, sex, disease stage, body mass index, and diagnosis year.

The increased survival in patients who started metformin after PDAC diagnosis demonstrates the inherent survival bias in ever/never classification because these patients had lived long enough to receive the drug, she said.

The ever/never classification is commonly used because it can be difficult to extract detailed information on drug use, dose, or timing from retrospective medical records, she noted in a press briefing.

“Epidemiologic studies of medication exposure and cancer survival warrant very careful and detailed data collection and analysis to minimize biases,” Dr. Chaiteerakij concluded. “Researchers should exercise caution when initiating clinical trials based on retrospective epidemiologic studies.”

That said, 11 pancreatic cancer trials are currently listed on www.clinicaltrials.gov, she told reporters.

A simple search of the site for “cancer and metformin” yields no fewer than 230 trials.

It isn’t possible to say at this time whether the Mayo results are applicable to other nonrecalcitrant cancers, Dr. Chaiteerakij said.

On Twitter @pwendl

A detailed survival analysis questions the rationale behind use of the diabetes drug metformin to improve pancreatic cancer survival.

Several epidemiologic studies have shown that metformin use reduces cancer mortality, leading the diabetes drug to be included in the treatment arm of 20 open clinical trials in recalcitrant cancers, Dr. Roongruedee Chaiteerakij reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The problem is that the epidemiologic studies commonly classified metformin use as simply “ever or never,” which may have introduced unintended biases.

To address these potential biases, Dr. Chaiteerakij and her colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., analyzed 1,360 patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and diabetes between 2000 and 2011 in the database of the Mayo Clinic Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Pancreatic Cancer. More than half (59%) were male; the average age was 67 years.

A total of 380 patients were excluded for surgically induced diabetes, unknown diabetes duration, and PDAC diagnosis more than 90 days prior to the first Mayo visit. This left 980 patients in the final cohort.

An initial analysis using the ever vs. never classification suggested that metformin use was associated with marginally improved survival in patients with PDAC (median 9.9 months ever use vs. 8.9 months never use; unadjusted hazard ratio, 0.9; P = .08), Dr. Chaiteerakij said.

The association was most significant in locally advanced PDAC patients (10.2 months ever use vs. 8.1 months never use; unadjusted HR 0.7; P = .006).

The investigators then performed a subanalysis of locally advanced PDAC patients, this time stratified by timing of metformin initiation: never used (reference group), started more than 1 year before PDAC diagnosis, started within 1 year before PDAC diagnosis, started less than 30 days post PDAC diagnosis, and started more than 30 days post PDAC diagnosis.

Median survival was 8.1, 10.1, and 9.9 months in the first three groups, increasing to 11.4 months and 13.7 months in the two groups that started metformin after PDAC diagnosis, Dr. Chaiteerakij reported.

Hazard ratios for the four metformin groups were 0.7, 0.6, 0.9, and 0.5, after adjustment for age, sex, disease stage, body mass index, and diagnosis year.

The increased survival in patients who started metformin after PDAC diagnosis demonstrates the inherent survival bias in ever/never classification because these patients had lived long enough to receive the drug, she said.

The ever/never classification is commonly used because it can be difficult to extract detailed information on drug use, dose, or timing from retrospective medical records, she noted in a press briefing.

“Epidemiologic studies of medication exposure and cancer survival warrant very careful and detailed data collection and analysis to minimize biases,” Dr. Chaiteerakij concluded. “Researchers should exercise caution when initiating clinical trials based on retrospective epidemiologic studies.”

That said, 11 pancreatic cancer trials are currently listed on www.clinicaltrials.gov, she told reporters.

A simple search of the site for “cancer and metformin” yields no fewer than 230 trials.

It isn’t possible to say at this time whether the Mayo results are applicable to other nonrecalcitrant cancers, Dr. Chaiteerakij said.

On Twitter @pwendl

A detailed survival analysis questions the rationale behind use of the diabetes drug metformin to improve pancreatic cancer survival.

Several epidemiologic studies have shown that metformin use reduces cancer mortality, leading the diabetes drug to be included in the treatment arm of 20 open clinical trials in recalcitrant cancers, Dr. Roongruedee Chaiteerakij reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The problem is that the epidemiologic studies commonly classified metformin use as simply “ever or never,” which may have introduced unintended biases.

To address these potential biases, Dr. Chaiteerakij and her colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., analyzed 1,360 patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and diabetes between 2000 and 2011 in the database of the Mayo Clinic Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Pancreatic Cancer. More than half (59%) were male; the average age was 67 years.

A total of 380 patients were excluded for surgically induced diabetes, unknown diabetes duration, and PDAC diagnosis more than 90 days prior to the first Mayo visit. This left 980 patients in the final cohort.

An initial analysis using the ever vs. never classification suggested that metformin use was associated with marginally improved survival in patients with PDAC (median 9.9 months ever use vs. 8.9 months never use; unadjusted hazard ratio, 0.9; P = .08), Dr. Chaiteerakij said.

The association was most significant in locally advanced PDAC patients (10.2 months ever use vs. 8.1 months never use; unadjusted HR 0.7; P = .006).

The investigators then performed a subanalysis of locally advanced PDAC patients, this time stratified by timing of metformin initiation: never used (reference group), started more than 1 year before PDAC diagnosis, started within 1 year before PDAC diagnosis, started less than 30 days post PDAC diagnosis, and started more than 30 days post PDAC diagnosis.

Median survival was 8.1, 10.1, and 9.9 months in the first three groups, increasing to 11.4 months and 13.7 months in the two groups that started metformin after PDAC diagnosis, Dr. Chaiteerakij reported.

Hazard ratios for the four metformin groups were 0.7, 0.6, 0.9, and 0.5, after adjustment for age, sex, disease stage, body mass index, and diagnosis year.

The increased survival in patients who started metformin after PDAC diagnosis demonstrates the inherent survival bias in ever/never classification because these patients had lived long enough to receive the drug, she said.

The ever/never classification is commonly used because it can be difficult to extract detailed information on drug use, dose, or timing from retrospective medical records, she noted in a press briefing.

“Epidemiologic studies of medication exposure and cancer survival warrant very careful and detailed data collection and analysis to minimize biases,” Dr. Chaiteerakij concluded. “Researchers should exercise caution when initiating clinical trials based on retrospective epidemiologic studies.”

That said, 11 pancreatic cancer trials are currently listed on www.clinicaltrials.gov, she told reporters.

A simple search of the site for “cancer and metformin” yields no fewer than 230 trials.

It isn’t possible to say at this time whether the Mayo results are applicable to other nonrecalcitrant cancers, Dr. Chaiteerakij said.

On Twitter @pwendl

FROM THE AACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Metformin use may not improve pancreatic cancer survival.

Major finding: Median survival was 8.1 months without metformin vs. 11.4 months if metformin started less than 30 days after cancer diagnosis and 13.7 months if started more than 30 days after diagnosis.

Data source: Retrospective cohort of 1,360 patients with pancreatic cancer and diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Chaiteerakij reported having nothing to disclose.

AACE diabetes guidelines address cancer risk, vaccines, and high-risk occupations

New diabetes mellitus practice guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists introduce recommendations on evaluating cancer risk, vaccinations, and special populations such as long-distance truck drivers who represent a high-risk occupational group in need of special attention in the diabetes population.

The guidelines, published in the April issue of Endocrine Practice (2015;21:1-87), expand on previous AACE recommendations on sleep disorders, breathing disorders, and depression in type 2 diabetes, and introduce more flexible and individualized targets not just for glucose and lipids but blood pressure and coagulation.

The 2015 guidelines replace those issued by AACE in 2011, and come with an updated diabetes management algorithm largely unchanged from the 2013 version. The new algorithm, like its predecessor, is not intended to substitute for a guideline but rather serves as a quick reference for management – “a sort of cookbook” – for clinicians, said Dr. Yehuda Handelsman, director of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif., and a cochair of the guidelines writing committee of the AACE task force.

The main changes to the algorithm were intended to reflect current Food and Drug Administration advice and a change in the warnings for the medications rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, and the two sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

The guideline, meanwhile, was significantly expanded. Among AACE’s new recommendations is that all patients with type 2 diabetes be vaccinated with influenza pneumococcal, and hepatitis B virus vaccine, tetanus-diphtheria boosters every 10 years, and other vaccines as recommended by their physicians.

The guidelines also recommend that people with diabetes be screened more rigorously for common cancers and cancers associated with obesity and metabolic disorders. Moreover, the guidelines recommend that while no specific antihyperglycemic agent has been definitively linked to cancer, “when a patient with DM has a history of a particular cancer, the physician may consider avoiding a medication that was initially considered disadvantageous to that cancer.”

Commercial drivers are identified as a group at high risk for developing obesity and diabetes. Moreover, “persons with DM engaged in various occupations including commercial drivers and pilots, anesthesiologists, and commercial or recreational divers have special management requirements, namely avoiding hypoglycemia. Treatment efforts for such patients should be focused on agents with reduced likelihood of hypoglycemia,” according to the guideline.

Dr. Handelsman said the recommendations on truck drivers came about “as we started to recognize that there are about 15 million commercial drivers in the United States, about 6 million of them transcontinental drivers. They are at huge risk for gaining weight and developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease. And a lot of states will not allow them to drive if they get insulin because they are considered at risk for hypoglycemia.” The guidelines recommend long-distance commercial drivers “would particularly benefit from improved healthcare access with a focus on measures to reduce obesity.”

The guidelines also promote individualizing hemoglobin A1ctargets to below 6.5% for most and above 6.5% for less-healthy individuals. Dr. Handelsman explained that “for people who are very sick with a lot of complications, very high hypoglycemia risk, and maybe short longevity, we might relax control on this group – maybe not even follow hemoglobin A1c but make sure the glucose is within a reasonable limit,” he said.

The guidelines apply the same principle to cardiovascular and weight targets, and aspirin. Lipid targets are also adjustable: “People in a very-high-risk group ought to have an appropriate goal. Those at lesser risk for complications can have a more intensive target, and if they have a lot of complications you may want to be more lax,” Dr. Handelsman said. For example, blood pressure, though ideally at less than 130/80 mm Hg for people with diabetes and kidney disease, should also be individualized on the basis of age, comorbidities, and duration of disease, the guidelines say.

“Recently, there were so many new guidelines and different targets were proposed for blood pressure and glucose yet many if not most had no relevance: The one-size-fits all approach is dead,” Dr. Handelsman said. “The concept of individualized care not only for the glucose but for the CV parameters is new this year and this is perhaps the only guideline on the market that to focus on comprehensive personalized management for people with diabetes and related cardiometabolic conditions.”

Dr. Handelsman reported fees, honoraria, or other forms of support from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Gilead, Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, Intarcia, Lexicon, Takeda, Halozyme, Amarin, Amylin, Janssen, and Vivus. Of the guideline’s 34 authors, all but 5 disclosed industry relationships.

New diabetes mellitus practice guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists introduce recommendations on evaluating cancer risk, vaccinations, and special populations such as long-distance truck drivers who represent a high-risk occupational group in need of special attention in the diabetes population.

The guidelines, published in the April issue of Endocrine Practice (2015;21:1-87), expand on previous AACE recommendations on sleep disorders, breathing disorders, and depression in type 2 diabetes, and introduce more flexible and individualized targets not just for glucose and lipids but blood pressure and coagulation.

The 2015 guidelines replace those issued by AACE in 2011, and come with an updated diabetes management algorithm largely unchanged from the 2013 version. The new algorithm, like its predecessor, is not intended to substitute for a guideline but rather serves as a quick reference for management – “a sort of cookbook” – for clinicians, said Dr. Yehuda Handelsman, director of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif., and a cochair of the guidelines writing committee of the AACE task force.

The main changes to the algorithm were intended to reflect current Food and Drug Administration advice and a change in the warnings for the medications rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, and the two sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

The guideline, meanwhile, was significantly expanded. Among AACE’s new recommendations is that all patients with type 2 diabetes be vaccinated with influenza pneumococcal, and hepatitis B virus vaccine, tetanus-diphtheria boosters every 10 years, and other vaccines as recommended by their physicians.

The guidelines also recommend that people with diabetes be screened more rigorously for common cancers and cancers associated with obesity and metabolic disorders. Moreover, the guidelines recommend that while no specific antihyperglycemic agent has been definitively linked to cancer, “when a patient with DM has a history of a particular cancer, the physician may consider avoiding a medication that was initially considered disadvantageous to that cancer.”

Commercial drivers are identified as a group at high risk for developing obesity and diabetes. Moreover, “persons with DM engaged in various occupations including commercial drivers and pilots, anesthesiologists, and commercial or recreational divers have special management requirements, namely avoiding hypoglycemia. Treatment efforts for such patients should be focused on agents with reduced likelihood of hypoglycemia,” according to the guideline.

Dr. Handelsman said the recommendations on truck drivers came about “as we started to recognize that there are about 15 million commercial drivers in the United States, about 6 million of them transcontinental drivers. They are at huge risk for gaining weight and developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease. And a lot of states will not allow them to drive if they get insulin because they are considered at risk for hypoglycemia.” The guidelines recommend long-distance commercial drivers “would particularly benefit from improved healthcare access with a focus on measures to reduce obesity.”

The guidelines also promote individualizing hemoglobin A1ctargets to below 6.5% for most and above 6.5% for less-healthy individuals. Dr. Handelsman explained that “for people who are very sick with a lot of complications, very high hypoglycemia risk, and maybe short longevity, we might relax control on this group – maybe not even follow hemoglobin A1c but make sure the glucose is within a reasonable limit,” he said.

The guidelines apply the same principle to cardiovascular and weight targets, and aspirin. Lipid targets are also adjustable: “People in a very-high-risk group ought to have an appropriate goal. Those at lesser risk for complications can have a more intensive target, and if they have a lot of complications you may want to be more lax,” Dr. Handelsman said. For example, blood pressure, though ideally at less than 130/80 mm Hg for people with diabetes and kidney disease, should also be individualized on the basis of age, comorbidities, and duration of disease, the guidelines say.

“Recently, there were so many new guidelines and different targets were proposed for blood pressure and glucose yet many if not most had no relevance: The one-size-fits all approach is dead,” Dr. Handelsman said. “The concept of individualized care not only for the glucose but for the CV parameters is new this year and this is perhaps the only guideline on the market that to focus on comprehensive personalized management for people with diabetes and related cardiometabolic conditions.”

Dr. Handelsman reported fees, honoraria, or other forms of support from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Gilead, Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, Intarcia, Lexicon, Takeda, Halozyme, Amarin, Amylin, Janssen, and Vivus. Of the guideline’s 34 authors, all but 5 disclosed industry relationships.

New diabetes mellitus practice guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists introduce recommendations on evaluating cancer risk, vaccinations, and special populations such as long-distance truck drivers who represent a high-risk occupational group in need of special attention in the diabetes population.

The guidelines, published in the April issue of Endocrine Practice (2015;21:1-87), expand on previous AACE recommendations on sleep disorders, breathing disorders, and depression in type 2 diabetes, and introduce more flexible and individualized targets not just for glucose and lipids but blood pressure and coagulation.

The 2015 guidelines replace those issued by AACE in 2011, and come with an updated diabetes management algorithm largely unchanged from the 2013 version. The new algorithm, like its predecessor, is not intended to substitute for a guideline but rather serves as a quick reference for management – “a sort of cookbook” – for clinicians, said Dr. Yehuda Handelsman, director of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif., and a cochair of the guidelines writing committee of the AACE task force.

The main changes to the algorithm were intended to reflect current Food and Drug Administration advice and a change in the warnings for the medications rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, and the two sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

The guideline, meanwhile, was significantly expanded. Among AACE’s new recommendations is that all patients with type 2 diabetes be vaccinated with influenza pneumococcal, and hepatitis B virus vaccine, tetanus-diphtheria boosters every 10 years, and other vaccines as recommended by their physicians.

The guidelines also recommend that people with diabetes be screened more rigorously for common cancers and cancers associated with obesity and metabolic disorders. Moreover, the guidelines recommend that while no specific antihyperglycemic agent has been definitively linked to cancer, “when a patient with DM has a history of a particular cancer, the physician may consider avoiding a medication that was initially considered disadvantageous to that cancer.”

Commercial drivers are identified as a group at high risk for developing obesity and diabetes. Moreover, “persons with DM engaged in various occupations including commercial drivers and pilots, anesthesiologists, and commercial or recreational divers have special management requirements, namely avoiding hypoglycemia. Treatment efforts for such patients should be focused on agents with reduced likelihood of hypoglycemia,” according to the guideline.

Dr. Handelsman said the recommendations on truck drivers came about “as we started to recognize that there are about 15 million commercial drivers in the United States, about 6 million of them transcontinental drivers. They are at huge risk for gaining weight and developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease. And a lot of states will not allow them to drive if they get insulin because they are considered at risk for hypoglycemia.” The guidelines recommend long-distance commercial drivers “would particularly benefit from improved healthcare access with a focus on measures to reduce obesity.”

The guidelines also promote individualizing hemoglobin A1ctargets to below 6.5% for most and above 6.5% for less-healthy individuals. Dr. Handelsman explained that “for people who are very sick with a lot of complications, very high hypoglycemia risk, and maybe short longevity, we might relax control on this group – maybe not even follow hemoglobin A1c but make sure the glucose is within a reasonable limit,” he said.

The guidelines apply the same principle to cardiovascular and weight targets, and aspirin. Lipid targets are also adjustable: “People in a very-high-risk group ought to have an appropriate goal. Those at lesser risk for complications can have a more intensive target, and if they have a lot of complications you may want to be more lax,” Dr. Handelsman said. For example, blood pressure, though ideally at less than 130/80 mm Hg for people with diabetes and kidney disease, should also be individualized on the basis of age, comorbidities, and duration of disease, the guidelines say.

“Recently, there were so many new guidelines and different targets were proposed for blood pressure and glucose yet many if not most had no relevance: The one-size-fits all approach is dead,” Dr. Handelsman said. “The concept of individualized care not only for the glucose but for the CV parameters is new this year and this is perhaps the only guideline on the market that to focus on comprehensive personalized management for people with diabetes and related cardiometabolic conditions.”

Dr. Handelsman reported fees, honoraria, or other forms of support from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Gilead, Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, Intarcia, Lexicon, Takeda, Halozyme, Amarin, Amylin, Janssen, and Vivus. Of the guideline’s 34 authors, all but 5 disclosed industry relationships.

Unrecognized diabetes common in acute MI

Ten percent of patients who presented with acute MI to 24 U.S. hospitals during a 3-year study had unrecognized diabetes, and only one-third of these cases were identified during the MI hospitalization, according to a report published online April 21 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

To determine the prevalence of underlying but undiagnosed diabetes among patients hospitalized with acute MI, investigators reviewed the records of 2,854 patients enrolled in an MI registry. They identified 287 patients (10.1%) whose records showed HbA1c levels of 6.5% or higher on routine laboratory testing and/or elevated fasting glucose levels at admission or during the typically 48- to 72-hour hospitalization.

Treating physicians recognized only 101 of these cases of diabetes (35%), as evidenced by their provision of diabetes education, prescription of glucose-lowering medication at discharge, or diagnosis code documentation in the patients’ charts, said Dr. Suzanne V. Arnold of Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., and her associates.

The routine use of HbA1c testing varied dramatically from one medical center to another, with some hospitals screening fewer than 10% of acute MI patients and others screening up to 82%. Incorporating universal HbA1c screening into standardized acute MI care would likely improve these rates, the investigators said (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2015 April 21 [doi:10.1161/circoutcomes.114.001452]).

Fully 20% of the patients with unrecognized diabetes had very high HbA1c values, ranging as high as 12.3%. Few of them received glucose-lowering medications during the 6 months after hospital discharge. “These data highlight a continued need to screen acute MI patients with HbA1c, to improve the rate of diabetes recognition during the hospitalization; this would not only guide initiation of glucose management interventions but also inform several key aspects of post-MI cardiovascular care,” such as the timing and type of revascularization procedures and the selection of ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, aldosterone inhibitors, and antiplatelet agents, they added.

Ten percent of patients who presented with acute MI to 24 U.S. hospitals during a 3-year study had unrecognized diabetes, and only one-third of these cases were identified during the MI hospitalization, according to a report published online April 21 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

To determine the prevalence of underlying but undiagnosed diabetes among patients hospitalized with acute MI, investigators reviewed the records of 2,854 patients enrolled in an MI registry. They identified 287 patients (10.1%) whose records showed HbA1c levels of 6.5% or higher on routine laboratory testing and/or elevated fasting glucose levels at admission or during the typically 48- to 72-hour hospitalization.

Treating physicians recognized only 101 of these cases of diabetes (35%), as evidenced by their provision of diabetes education, prescription of glucose-lowering medication at discharge, or diagnosis code documentation in the patients’ charts, said Dr. Suzanne V. Arnold of Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., and her associates.

The routine use of HbA1c testing varied dramatically from one medical center to another, with some hospitals screening fewer than 10% of acute MI patients and others screening up to 82%. Incorporating universal HbA1c screening into standardized acute MI care would likely improve these rates, the investigators said (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2015 April 21 [doi:10.1161/circoutcomes.114.001452]).

Fully 20% of the patients with unrecognized diabetes had very high HbA1c values, ranging as high as 12.3%. Few of them received glucose-lowering medications during the 6 months after hospital discharge. “These data highlight a continued need to screen acute MI patients with HbA1c, to improve the rate of diabetes recognition during the hospitalization; this would not only guide initiation of glucose management interventions but also inform several key aspects of post-MI cardiovascular care,” such as the timing and type of revascularization procedures and the selection of ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, aldosterone inhibitors, and antiplatelet agents, they added.

Ten percent of patients who presented with acute MI to 24 U.S. hospitals during a 3-year study had unrecognized diabetes, and only one-third of these cases were identified during the MI hospitalization, according to a report published online April 21 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

To determine the prevalence of underlying but undiagnosed diabetes among patients hospitalized with acute MI, investigators reviewed the records of 2,854 patients enrolled in an MI registry. They identified 287 patients (10.1%) whose records showed HbA1c levels of 6.5% or higher on routine laboratory testing and/or elevated fasting glucose levels at admission or during the typically 48- to 72-hour hospitalization.

Treating physicians recognized only 101 of these cases of diabetes (35%), as evidenced by their provision of diabetes education, prescription of glucose-lowering medication at discharge, or diagnosis code documentation in the patients’ charts, said Dr. Suzanne V. Arnold of Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., and her associates.

The routine use of HbA1c testing varied dramatically from one medical center to another, with some hospitals screening fewer than 10% of acute MI patients and others screening up to 82%. Incorporating universal HbA1c screening into standardized acute MI care would likely improve these rates, the investigators said (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2015 April 21 [doi:10.1161/circoutcomes.114.001452]).

Fully 20% of the patients with unrecognized diabetes had very high HbA1c values, ranging as high as 12.3%. Few of them received glucose-lowering medications during the 6 months after hospital discharge. “These data highlight a continued need to screen acute MI patients with HbA1c, to improve the rate of diabetes recognition during the hospitalization; this would not only guide initiation of glucose management interventions but also inform several key aspects of post-MI cardiovascular care,” such as the timing and type of revascularization procedures and the selection of ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, aldosterone inhibitors, and antiplatelet agents, they added.

FROM CIRCULATION: CARDIOVASCULAR QUALITY AND OUTCOMES

Key clinical point: Many patients presenting with acute MI had unrecognized diabetes and, in most cases, that DM remained undiagnosed, untreated, and unrecorded.

Major finding: Of 2,854 (10%) patients enrolled in an MI registry, 287 had HbA1c levels of 6.5% or higher on routine laboratory testing during hospitalization for acute MI, but treating physicians recognized only 101 of these cases of diabetes (35%).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 2,854 adults presenting with acute MI to 24 U.S. medical centers during a 3.5-year period.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and supported by a research grant from Genentech. Dr. Arnold reported receiving honoraria from Novartis; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Metabolic syndrome more prevalent in bipolar disorder

Metabolic syndrome was significantly more prevalent in patients with bipolar disorder than in those with major depressive disorder or in controls, Barbora Silarova, Ph.D., and her coauthors reported.

In a study of 2,431 patients the investigators found that those with bipolar disorder had a significantly higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, compared with patients with major depressive disorder and nonpsychiatric controls (28.4% vs. 20.2% and 16.5%, respectively; P < .001). This difference was consistent when adjusted for sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, Dr. Silarova and her colleagues said in the paper.

“Clinically, it might be relevant to apply individualized treatment for [bipolar disorder] patients that also includes assessment of metabolic risk factors, psychoeducation, weight loss intervention, and improvement of health-related behaviors,” the authors said.

Read the full article in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research here.

Metabolic syndrome was significantly more prevalent in patients with bipolar disorder than in those with major depressive disorder or in controls, Barbora Silarova, Ph.D., and her coauthors reported.

In a study of 2,431 patients the investigators found that those with bipolar disorder had a significantly higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, compared with patients with major depressive disorder and nonpsychiatric controls (28.4% vs. 20.2% and 16.5%, respectively; P < .001). This difference was consistent when adjusted for sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, Dr. Silarova and her colleagues said in the paper.

“Clinically, it might be relevant to apply individualized treatment for [bipolar disorder] patients that also includes assessment of metabolic risk factors, psychoeducation, weight loss intervention, and improvement of health-related behaviors,” the authors said.

Read the full article in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research here.

Metabolic syndrome was significantly more prevalent in patients with bipolar disorder than in those with major depressive disorder or in controls, Barbora Silarova, Ph.D., and her coauthors reported.

In a study of 2,431 patients the investigators found that those with bipolar disorder had a significantly higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, compared with patients with major depressive disorder and nonpsychiatric controls (28.4% vs. 20.2% and 16.5%, respectively; P < .001). This difference was consistent when adjusted for sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, Dr. Silarova and her colleagues said in the paper.

“Clinically, it might be relevant to apply individualized treatment for [bipolar disorder] patients that also includes assessment of metabolic risk factors, psychoeducation, weight loss intervention, and improvement of health-related behaviors,” the authors said.

Read the full article in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research here.

How to forestall heart failure by 15 years

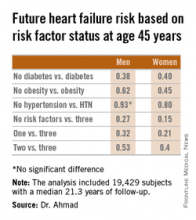

SAN DIEGO– Men and women who are able to prevent or delay onset of hypertension, obesity, and diabetes beyond age 45 years can expect to reap a major benefit: living for 11-15 years longer without heart failure, according to a novel study featuring more than 500,000 person-years of follow-up.

“We’re interested in thinking about risk in a different way. Traditionally, risk has been thought of in terms of how different risk factors lead to increased chances for heart failure. Instead, we’re interested in thinking about how preventing the development of risk factors leads to increased longevity and extension of heart failure–free survival. It’s a much more powerful message when you’re talking to patients in their 30s or 40s to say that they’ll be able to live 11-15 years longer without heart failure if they can avoid developing these three risk factors,” Dr. Faraz S. Ahmad explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented an analysis of pooled data from four large studies with adjudicated heart failure outcomes. The analysis, conducted as part of the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project, included a total of 19,429 subjects with a median 21.3 years of follow-up, during which 1,677 participants were diagnosed with incident heart failure.

This analysis quantified the association between prevalent hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity with heart failure–free and overall survival, beginning at age 45 years and with 50 years of subsequent follow-up, noted Dr. Ahmad, a cardiology fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Among men with none of the three key risk factors at age 45 years, the multivariate-adjusted risk of subsequently developing heart failure was reduced by 73%, compared with that of men with all three risk factors present. Women with none of the three risk factors enjoyed an 85% relative risk reduction.

Among men who developed heart failure, those with diabetes by age 45 years were diagnosed with heart failure 8.6 years earlier than were those without diabetes at age 45 years. Among women with diabetes at age 45 years, heart failure was diagnosed when they were 10.6 years younger than in those without diabetes were.

These data take on added weight in light of projections regarding the future of heart failure in the United States. At present, there are an estimated 825,000 new cases of heart failure per year. The disease prevalence is 5.1 million. The annual cost is $31 billion and is expected to climb by 126% over the next 20 years, Dr. Ahmad said.

The four studies upon which this lifetime risk analysis was based were the Framingham Heart Study, the Framingham Offspring Study, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, and the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Together they included 509,650 person-years of follow-up. All four studies were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, as was this analysis. Dr. Ahmad reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO– Men and women who are able to prevent or delay onset of hypertension, obesity, and diabetes beyond age 45 years can expect to reap a major benefit: living for 11-15 years longer without heart failure, according to a novel study featuring more than 500,000 person-years of follow-up.

“We’re interested in thinking about risk in a different way. Traditionally, risk has been thought of in terms of how different risk factors lead to increased chances for heart failure. Instead, we’re interested in thinking about how preventing the development of risk factors leads to increased longevity and extension of heart failure–free survival. It’s a much more powerful message when you’re talking to patients in their 30s or 40s to say that they’ll be able to live 11-15 years longer without heart failure if they can avoid developing these three risk factors,” Dr. Faraz S. Ahmad explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented an analysis of pooled data from four large studies with adjudicated heart failure outcomes. The analysis, conducted as part of the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project, included a total of 19,429 subjects with a median 21.3 years of follow-up, during which 1,677 participants were diagnosed with incident heart failure.

This analysis quantified the association between prevalent hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity with heart failure–free and overall survival, beginning at age 45 years and with 50 years of subsequent follow-up, noted Dr. Ahmad, a cardiology fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Among men with none of the three key risk factors at age 45 years, the multivariate-adjusted risk of subsequently developing heart failure was reduced by 73%, compared with that of men with all three risk factors present. Women with none of the three risk factors enjoyed an 85% relative risk reduction.

Among men who developed heart failure, those with diabetes by age 45 years were diagnosed with heart failure 8.6 years earlier than were those without diabetes at age 45 years. Among women with diabetes at age 45 years, heart failure was diagnosed when they were 10.6 years younger than in those without diabetes were.

These data take on added weight in light of projections regarding the future of heart failure in the United States. At present, there are an estimated 825,000 new cases of heart failure per year. The disease prevalence is 5.1 million. The annual cost is $31 billion and is expected to climb by 126% over the next 20 years, Dr. Ahmad said.

The four studies upon which this lifetime risk analysis was based were the Framingham Heart Study, the Framingham Offspring Study, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, and the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Together they included 509,650 person-years of follow-up. All four studies were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, as was this analysis. Dr. Ahmad reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO– Men and women who are able to prevent or delay onset of hypertension, obesity, and diabetes beyond age 45 years can expect to reap a major benefit: living for 11-15 years longer without heart failure, according to a novel study featuring more than 500,000 person-years of follow-up.

“We’re interested in thinking about risk in a different way. Traditionally, risk has been thought of in terms of how different risk factors lead to increased chances for heart failure. Instead, we’re interested in thinking about how preventing the development of risk factors leads to increased longevity and extension of heart failure–free survival. It’s a much more powerful message when you’re talking to patients in their 30s or 40s to say that they’ll be able to live 11-15 years longer without heart failure if they can avoid developing these three risk factors,” Dr. Faraz S. Ahmad explained at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented an analysis of pooled data from four large studies with adjudicated heart failure outcomes. The analysis, conducted as part of the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project, included a total of 19,429 subjects with a median 21.3 years of follow-up, during which 1,677 participants were diagnosed with incident heart failure.

This analysis quantified the association between prevalent hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity with heart failure–free and overall survival, beginning at age 45 years and with 50 years of subsequent follow-up, noted Dr. Ahmad, a cardiology fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Among men with none of the three key risk factors at age 45 years, the multivariate-adjusted risk of subsequently developing heart failure was reduced by 73%, compared with that of men with all three risk factors present. Women with none of the three risk factors enjoyed an 85% relative risk reduction.

Among men who developed heart failure, those with diabetes by age 45 years were diagnosed with heart failure 8.6 years earlier than were those without diabetes at age 45 years. Among women with diabetes at age 45 years, heart failure was diagnosed when they were 10.6 years younger than in those without diabetes were.

These data take on added weight in light of projections regarding the future of heart failure in the United States. At present, there are an estimated 825,000 new cases of heart failure per year. The disease prevalence is 5.1 million. The annual cost is $31 billion and is expected to climb by 126% over the next 20 years, Dr. Ahmad said.

The four studies upon which this lifetime risk analysis was based were the Framingham Heart Study, the Framingham Offspring Study, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, and the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Together they included 509,650 person-years of follow-up. All four studies were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, as was this analysis. Dr. Ahmad reported having no financial conflicts.

AT ACC 15

Key clinical point: Individuals who remain free of hypertension, obesity, and diabetes at age 45 years can expect to enjoy an extra 11-15 years of heart failure–free survival.

Major finding: The lifetime risk of developing heart failure in men without hypertension, obesity, and diabetes at age 45 years was reduced by 73%, compared with the risk in men having all three risk factors at that age. In women free of the three risk factors at age 45 years, the relative risk reduction was 85%.

Data source: This pooled analysis of data from four major studies included 19,429 subjects with 509,650 person-years of follow-up, during which 1,677 participants were newly diagnosed with heart failure.

Disclosures: This analysis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Stenting before CABG linked to higher mortality for diabetic patients

Since the debut of drug-eluting stents, more high-risk patient groups, namely diabetic patients, have undergone coronary stenting as opposed to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) as an option to open blocked arteries; however, diabetic patients with stents who go on to have CABG have significantly higher 5-year death rates than do unstented diabetics who undergo CABG, according to a study published in the May issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

A review of 7,005 CABG procedures performed from 1996 to 2007 at Mercy St. Vincent Medical Center in Toledo, Ohio, found that diabetic patients with triple-vessel disease and a prior percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting (PCI-S) who underwent CABG had a 39% greater risk of death within 5 years of the operation. The findings are significant, according to Dr. Victor Nauffal and his colleagues at the American University of Beirut, because increasing numbers of patients with coronary stents are referred for CABG (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.01.051).

Previous studies have linked prior stenting to an increased risk of bleeding and stent thrombosis during CABG, so having a better understanding of anticoagulation during the operation and the timing of the surgery after stenting could decrease complications. Investigations of the long-term outcomes of patients with stents who have CABG, however, have been lacking. This study investigated the premise that diabetics with triple-vessel disease and a stent had poorer outcomes because of endothelial dysfunction and the increased strain that triple-vessel disease places on the heart.

After exclusions, the final study population comprised 1,583 diabetic patients with concomitant triple-vessel disease, 202 (12.8%) of whom had coronary stents. The study defined triple-vessel disease as blockages of 50% or more in all three native coronary vessels or left main artery plus right coronary artery disease.

Early mortality rates – death within 30 days of the procedure – were similar between the two groups: 3.3% overall, 3% in the prior-PCI group, and 3.3% in the no-PCI group; therefore, prior PCI was not a predictor of early mortality.

Five-year cumulative survival was 78.5% in the no-PCI group, compared with 74.8% in the PCI group. When adjusting for a variety of clinical variables before CABG, stenting was associated with a 39% greater mortality at 5 years. The investigators accounted for the emergence of drug-eluting stents during the 10-year study period but found that they did not contribute significantly to overall outcomes.

The cause of death was known for 81.7% (282 of 345) of the deaths in the overall cohort, with 5-year cardiac deaths higher in the PCI-S group: 8.4% vs. 7.5% for the no-PCI group. “Notably, 100% of PCI-S cardiac mortality was categorized as coronary heart disease related compared to 89.3% (92/103) of cardiac mortality in the no-PCI group,” Dr. Nauffal and his associates said.

Careful patient selection for CABG is in order for diabetics with triple-vessel disease, particularly those with a prior stent, the authors advised. “An early team-based approach including a cardiologist and cardiac surgeon should be implemented for optimal revascularization strategy selection in diabetics with triple-vessel disease and for close medical follow-up of those higher risk CABG patients with history of intracoronary stents,” Dr. Nauffal and his colleagues concluded.

The Johns Hopkins Murex Research Award supported Dr. Nauffal. The authors had no other relevant disclosures.