User login

Treating psoriasis with biologics: Recommendations from an expert

LAS VEGAS – If you’re considering adding biologics for psoriasis to your clinical practice, dermatologist Kristina C. Duffin, MD, has some advice: Don’t expect to just use one drug, focus on comorbidities, and embrace strategies to bypass the potential obstacle of prior-authorization approvals.

Here are some tips from Dr. Duffin, who spoke at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar:

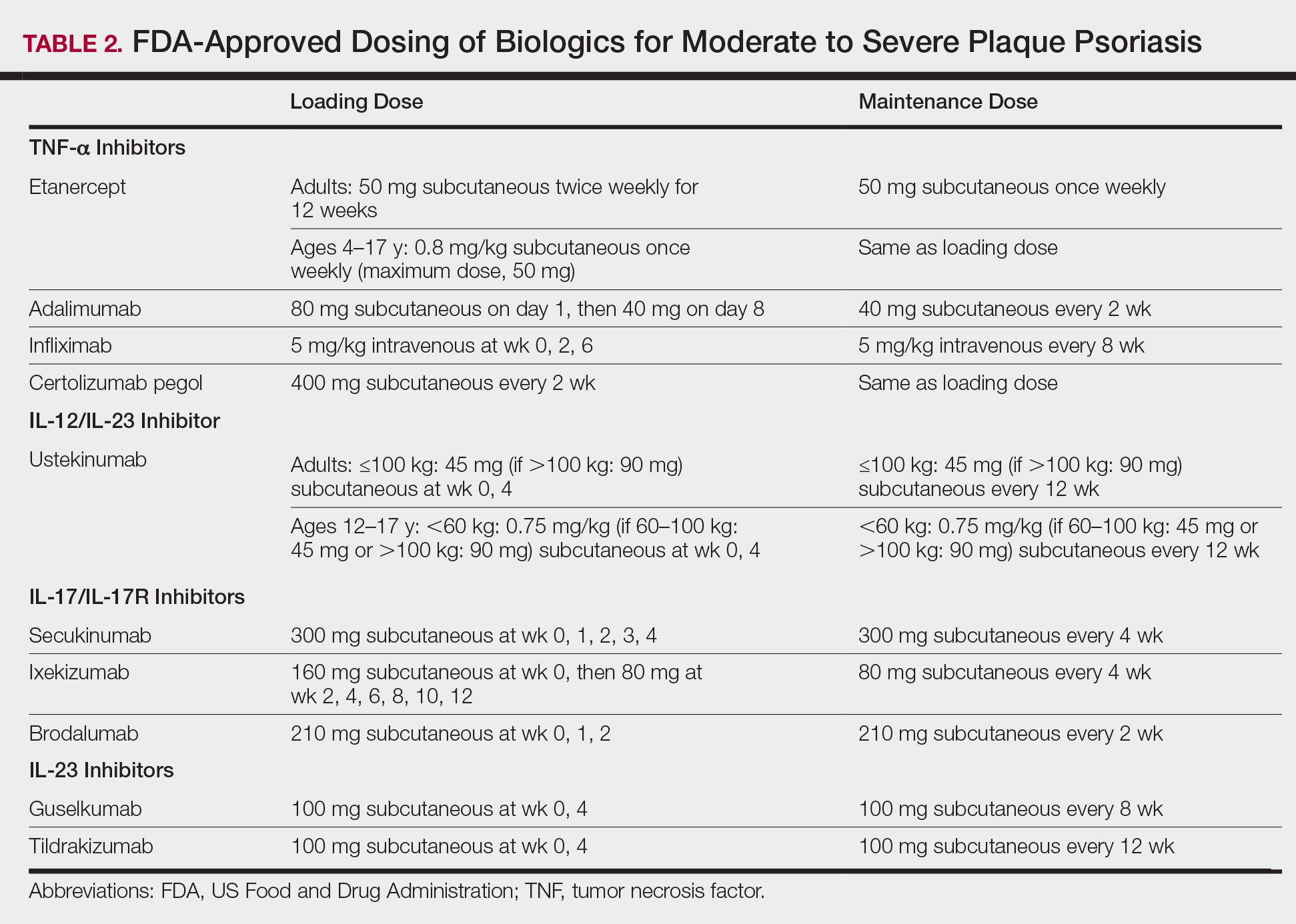

- Don’t expect a one-size-fits-all medication. “There is no one, single go-to drug,” said Dr. Duffin, who is cochair of the department of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “Maybe someday, we will have a biological personalized medicine marker to say this is the right drug, but for now we don’t.” More than 10 biologics are available to treat psoriasis, she said, and more are in the pipeline.

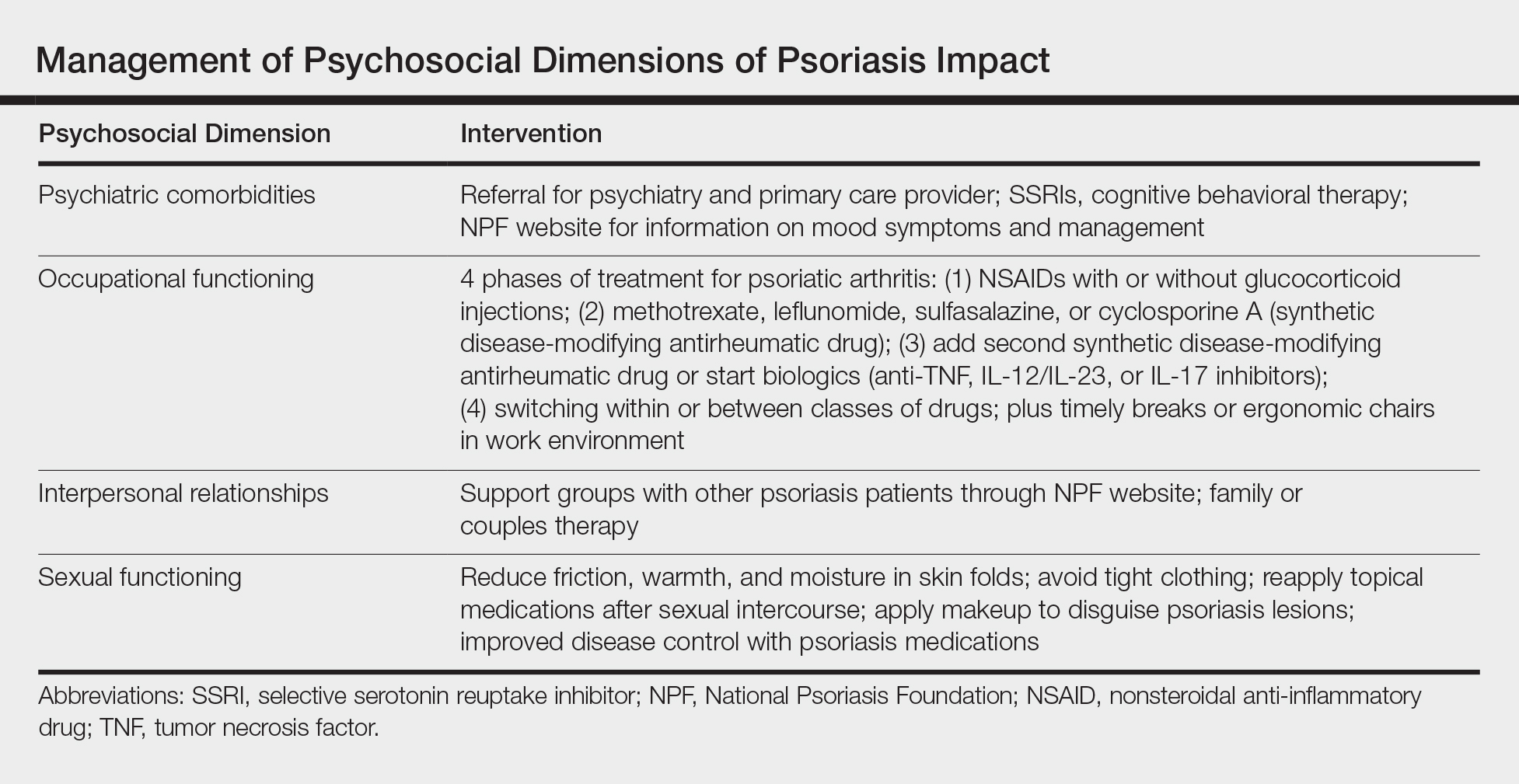

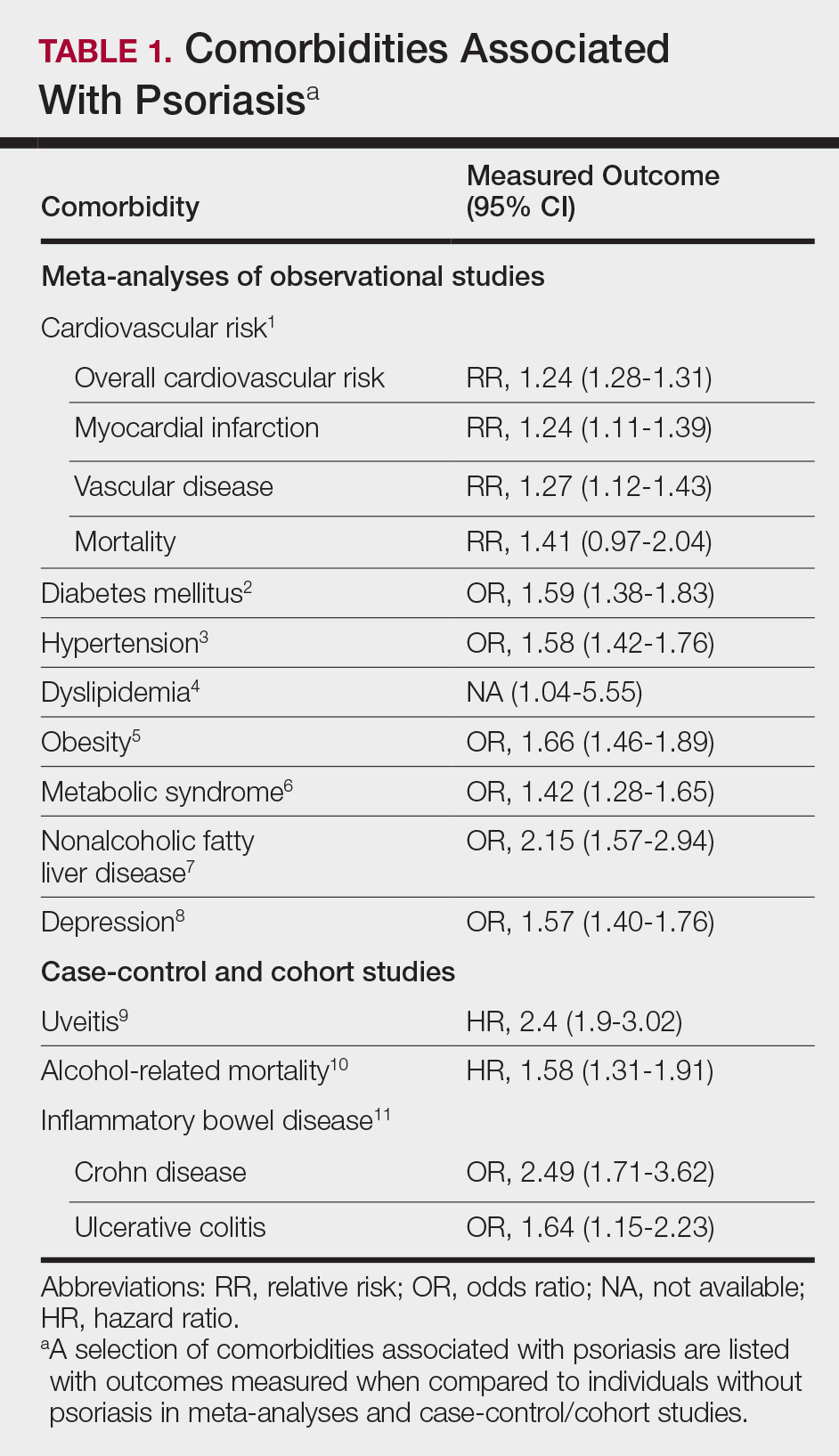

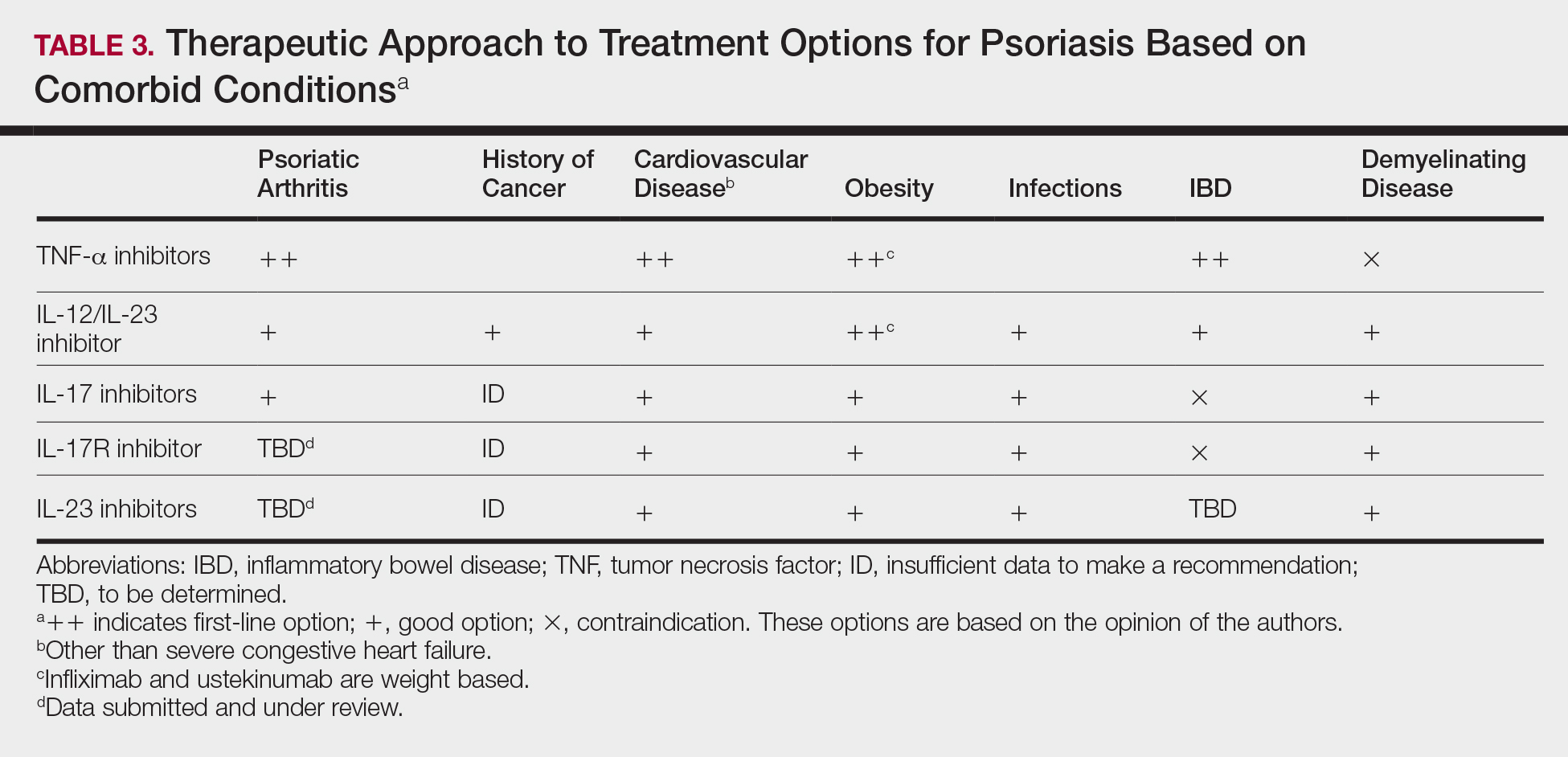

- Pay close attention to comorbidities. It’s important to “have a good grasp” of a patient’s comorbidities, which can help focus the choice of a biologic, Dr. Duffin said. She recommends starting with an anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents for patients with psoriatic arthritis. For patients with Crohn’s disease, she recommends anti-TNF (adalimumab, infliximab) and anti-interleukin–12/23 or anti-IL-23 agents (ustekinumab). Anti-TNF agents should be avoided in patients with multiple sclerosis, and anti-IL-17 agents shouldn’t be given to patients with recurrent candidiasis, she noted.

- Encourage patients to make prompt decisions. Dr. Duffin sits down with patients to discuss various biologic options, and she goes over information in handouts. She also focuses on their needs: “Are they interested in getting better fast? Do they want to be clear for their wedding in a month?” She prefers to not let patients go home to think about what they’d like to do. Instead, she advises patients to make choices while at the office visit.

- Order lab tests and be careful about vaccines. Dr. Duffin orders the following tests for all patients who are starting on biologics: CBC, comprehensive metabolic panel, hepatitis B and C, and tuberculosis. She orders HIV, Hba1c and lipid tests, if appropriate. She prefers that patients treated with biologics avoid live vaccines. She suggests other vaccines, if indicated, such as seasonal influenza and pneumonia vaccines, and for those aged 50 years and older, herpes zoster vaccine. She urges patients to call the office if they have an infection or need surgery because they may need to discuss putting a temporary hold on the biologics.

- Understand how to navigate formularies.“Getting drugs approved for patients with Medicare is a challenge,” Dr. Duffin said. It’s helpful to understand how insurers handle specific psoriasis drugs so you can choose one that’s likely to be covered if you’re unsure which one is best. The website www.covermymeds.com allows physicians to easily check insurer formularies, free of charge, she said.

- Documentation is crucial when you’re dealing with an insurer. Document body surface area, Psoriasis Area Severity Index scores, or physician global assessment measures, she advised. An app provided by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis, is a helpful in determining these measurements, she said. Also include information about failed treatments and the rationale behind why you chose a specific treatment, she said. “If denial happens, get the details,” she said. This may turn up a clerical error on the insurer’s part that incorrectly led to a denial.

- Escalate challenges to drug denials. If the preferred treatment is denied, one option is to appeal the denial. As a resource, Dr. Duffin pointed to sample letters for appealing denials for physicians and patients on the websites for the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation. Ask for a limited 6-month approval, she said, or have the patient write a letter to the insurer using one of the sample letter templates. Another option is to ask the insurer for a “peer-to-peer” review, she said. “Sometimes it’s really hard for insurance company folks to say no to you if you have a really good story,” she commented.

- Help your patients get financial assistance. Almost every biologic manufacturer has a patient assistance plan, which can also help with deductibles and copays, Dr. Duffin said.

Dr. Duffin discloses consulting for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sienna. She has received grant/contracted research support from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sienna, Stiefel, and UCB.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – If you’re considering adding biologics for psoriasis to your clinical practice, dermatologist Kristina C. Duffin, MD, has some advice: Don’t expect to just use one drug, focus on comorbidities, and embrace strategies to bypass the potential obstacle of prior-authorization approvals.

Here are some tips from Dr. Duffin, who spoke at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar:

- Don’t expect a one-size-fits-all medication. “There is no one, single go-to drug,” said Dr. Duffin, who is cochair of the department of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “Maybe someday, we will have a biological personalized medicine marker to say this is the right drug, but for now we don’t.” More than 10 biologics are available to treat psoriasis, she said, and more are in the pipeline.

- Pay close attention to comorbidities. It’s important to “have a good grasp” of a patient’s comorbidities, which can help focus the choice of a biologic, Dr. Duffin said. She recommends starting with an anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents for patients with psoriatic arthritis. For patients with Crohn’s disease, she recommends anti-TNF (adalimumab, infliximab) and anti-interleukin–12/23 or anti-IL-23 agents (ustekinumab). Anti-TNF agents should be avoided in patients with multiple sclerosis, and anti-IL-17 agents shouldn’t be given to patients with recurrent candidiasis, she noted.

- Encourage patients to make prompt decisions. Dr. Duffin sits down with patients to discuss various biologic options, and she goes over information in handouts. She also focuses on their needs: “Are they interested in getting better fast? Do they want to be clear for their wedding in a month?” She prefers to not let patients go home to think about what they’d like to do. Instead, she advises patients to make choices while at the office visit.

- Order lab tests and be careful about vaccines. Dr. Duffin orders the following tests for all patients who are starting on biologics: CBC, comprehensive metabolic panel, hepatitis B and C, and tuberculosis. She orders HIV, Hba1c and lipid tests, if appropriate. She prefers that patients treated with biologics avoid live vaccines. She suggests other vaccines, if indicated, such as seasonal influenza and pneumonia vaccines, and for those aged 50 years and older, herpes zoster vaccine. She urges patients to call the office if they have an infection or need surgery because they may need to discuss putting a temporary hold on the biologics.

- Understand how to navigate formularies.“Getting drugs approved for patients with Medicare is a challenge,” Dr. Duffin said. It’s helpful to understand how insurers handle specific psoriasis drugs so you can choose one that’s likely to be covered if you’re unsure which one is best. The website www.covermymeds.com allows physicians to easily check insurer formularies, free of charge, she said.

- Documentation is crucial when you’re dealing with an insurer. Document body surface area, Psoriasis Area Severity Index scores, or physician global assessment measures, she advised. An app provided by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis, is a helpful in determining these measurements, she said. Also include information about failed treatments and the rationale behind why you chose a specific treatment, she said. “If denial happens, get the details,” she said. This may turn up a clerical error on the insurer’s part that incorrectly led to a denial.

- Escalate challenges to drug denials. If the preferred treatment is denied, one option is to appeal the denial. As a resource, Dr. Duffin pointed to sample letters for appealing denials for physicians and patients on the websites for the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation. Ask for a limited 6-month approval, she said, or have the patient write a letter to the insurer using one of the sample letter templates. Another option is to ask the insurer for a “peer-to-peer” review, she said. “Sometimes it’s really hard for insurance company folks to say no to you if you have a really good story,” she commented.

- Help your patients get financial assistance. Almost every biologic manufacturer has a patient assistance plan, which can also help with deductibles and copays, Dr. Duffin said.

Dr. Duffin discloses consulting for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sienna. She has received grant/contracted research support from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sienna, Stiefel, and UCB.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – If you’re considering adding biologics for psoriasis to your clinical practice, dermatologist Kristina C. Duffin, MD, has some advice: Don’t expect to just use one drug, focus on comorbidities, and embrace strategies to bypass the potential obstacle of prior-authorization approvals.

Here are some tips from Dr. Duffin, who spoke at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar:

- Don’t expect a one-size-fits-all medication. “There is no one, single go-to drug,” said Dr. Duffin, who is cochair of the department of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “Maybe someday, we will have a biological personalized medicine marker to say this is the right drug, but for now we don’t.” More than 10 biologics are available to treat psoriasis, she said, and more are in the pipeline.

- Pay close attention to comorbidities. It’s important to “have a good grasp” of a patient’s comorbidities, which can help focus the choice of a biologic, Dr. Duffin said. She recommends starting with an anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents for patients with psoriatic arthritis. For patients with Crohn’s disease, she recommends anti-TNF (adalimumab, infliximab) and anti-interleukin–12/23 or anti-IL-23 agents (ustekinumab). Anti-TNF agents should be avoided in patients with multiple sclerosis, and anti-IL-17 agents shouldn’t be given to patients with recurrent candidiasis, she noted.

- Encourage patients to make prompt decisions. Dr. Duffin sits down with patients to discuss various biologic options, and she goes over information in handouts. She also focuses on their needs: “Are they interested in getting better fast? Do they want to be clear for their wedding in a month?” She prefers to not let patients go home to think about what they’d like to do. Instead, she advises patients to make choices while at the office visit.

- Order lab tests and be careful about vaccines. Dr. Duffin orders the following tests for all patients who are starting on biologics: CBC, comprehensive metabolic panel, hepatitis B and C, and tuberculosis. She orders HIV, Hba1c and lipid tests, if appropriate. She prefers that patients treated with biologics avoid live vaccines. She suggests other vaccines, if indicated, such as seasonal influenza and pneumonia vaccines, and for those aged 50 years and older, herpes zoster vaccine. She urges patients to call the office if they have an infection or need surgery because they may need to discuss putting a temporary hold on the biologics.

- Understand how to navigate formularies.“Getting drugs approved for patients with Medicare is a challenge,” Dr. Duffin said. It’s helpful to understand how insurers handle specific psoriasis drugs so you can choose one that’s likely to be covered if you’re unsure which one is best. The website www.covermymeds.com allows physicians to easily check insurer formularies, free of charge, she said.

- Documentation is crucial when you’re dealing with an insurer. Document body surface area, Psoriasis Area Severity Index scores, or physician global assessment measures, she advised. An app provided by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis, is a helpful in determining these measurements, she said. Also include information about failed treatments and the rationale behind why you chose a specific treatment, she said. “If denial happens, get the details,” she said. This may turn up a clerical error on the insurer’s part that incorrectly led to a denial.

- Escalate challenges to drug denials. If the preferred treatment is denied, one option is to appeal the denial. As a resource, Dr. Duffin pointed to sample letters for appealing denials for physicians and patients on the websites for the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation. Ask for a limited 6-month approval, she said, or have the patient write a letter to the insurer using one of the sample letter templates. Another option is to ask the insurer for a “peer-to-peer” review, she said. “Sometimes it’s really hard for insurance company folks to say no to you if you have a really good story,” she commented.

- Help your patients get financial assistance. Almost every biologic manufacturer has a patient assistance plan, which can also help with deductibles and copays, Dr. Duffin said.

Dr. Duffin discloses consulting for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sienna. She has received grant/contracted research support from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sienna, Stiefel, and UCB.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Comorbidities are important in psoriasis care

LAS VEGAS – Pay attention to comorbidities in your psoriasis patients because there may not be anyone else doing so.

“Many of our patients don’t have primary care physicians; many are untreated for psoriasis. They come to a clinical trial to get treated – some of them may not have insurance – so it is important for us to watch for these comorbidities,” Kristina C. Duffin, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

Yet, that does not seem to be happening consistently, according to Dr. Duffin, of the department of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. One in five dermatologists admitted to never screening or referring their psoriasis patients for management of cardiovascular risks in a 2015 survey (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.029).

Often patients at the start of biologic therapy are counseled about the risk for developing tuberculosis, yet the lifetime risk for doing so in the United States is 0.3%. Similarly, patients are often counseled on the risk for developing lymphoma, even though the excess risk for developing lymphoma that can be attributed to psoriasis treatment is 7.9 per 100,000 psoriasis patients per year. That screening seems to be driven by warnings issued in direct-to-consumer advertising, Dr. Duffin suggested.

“Although psoriasis patients have an increased relative risk of lymphoma, the absolute risk attributable to psoriasis is low,” Dr. Duffin pointed out.

Some of the comorbidities she advised dermatologists to watch for are described below.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is the most important psoriasis comorbidity, Dr. Duffin said. Between 20% and 30% of psoriasis patients will develop psoriatic arthritis.

In a study of 1,511 patients in 48 centers in Germany, 21% of psoriasis patients were diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis and of those, more than 95% had active arthritis and 53% had five or more affected joints (Br J Dermatol. 2009;160[5]:1040-7).

The GRAPPA app is an easy, free screening tool for psoriatic arthritis; patients who score 3 or more out of 5 items on the psoriasis epidemiology screening tool (PEST) are deemed positive for psoriatic arthritis, Dr. Duffin noted.

Cardiovascular disease

Psoriasis patients are at increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, Dr. Duffin said. In fact, CV risk from severe psoriasis is similar to the risk conferred by diabetes.

She added that there is epidemiologic evidence for CV risk modification with several of the biologics approved for psoriasis.

Hypertension

Hypertension is prevalent and more severe in psoriasis patients, Dr. Duffin said, citing a 2011 case-control study of electronic medical records at the University of California, Davis. Psoriasis patients with hypertension were 5 times more likely than patients without psoriasis to be on one antihypertensive medication, 9.5 times more likely to be on two, and almost 20 times more likely to be on four antihypertensive medications (PLoS One. 2011 Mar 29;6[3]:e18227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018227).

Importantly, few primary care physicians and cardiologists are aware of the increased risk for hypertension in psoriasis patients.

Less than half (45%) of primary care physicians and 57% of cardiologists reported they were aware that psoriasis was associated with worse cardiovascular outcome, and only 43% of physicians reported screening psoriasis patients for hypertension starting at age 20 years, according to a 2012 survey of 251 physicians (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Sep;67[3]:357-62).

Dr. Duffin called on dermatologists to ensure that the primary care physicians they work with understand these increased risks.

“Commit to including a comment in consultation letters or letters back to primary care physicians that talks about the cardiovascular risks of the disease,” she said.

Dr. Duffin reported that she is a consultant and has received grant or contracted research support for many companies that manufacture dermatologic therapies.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Pay attention to comorbidities in your psoriasis patients because there may not be anyone else doing so.

“Many of our patients don’t have primary care physicians; many are untreated for psoriasis. They come to a clinical trial to get treated – some of them may not have insurance – so it is important for us to watch for these comorbidities,” Kristina C. Duffin, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

Yet, that does not seem to be happening consistently, according to Dr. Duffin, of the department of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. One in five dermatologists admitted to never screening or referring their psoriasis patients for management of cardiovascular risks in a 2015 survey (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.029).

Often patients at the start of biologic therapy are counseled about the risk for developing tuberculosis, yet the lifetime risk for doing so in the United States is 0.3%. Similarly, patients are often counseled on the risk for developing lymphoma, even though the excess risk for developing lymphoma that can be attributed to psoriasis treatment is 7.9 per 100,000 psoriasis patients per year. That screening seems to be driven by warnings issued in direct-to-consumer advertising, Dr. Duffin suggested.

“Although psoriasis patients have an increased relative risk of lymphoma, the absolute risk attributable to psoriasis is low,” Dr. Duffin pointed out.

Some of the comorbidities she advised dermatologists to watch for are described below.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is the most important psoriasis comorbidity, Dr. Duffin said. Between 20% and 30% of psoriasis patients will develop psoriatic arthritis.

In a study of 1,511 patients in 48 centers in Germany, 21% of psoriasis patients were diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis and of those, more than 95% had active arthritis and 53% had five or more affected joints (Br J Dermatol. 2009;160[5]:1040-7).

The GRAPPA app is an easy, free screening tool for psoriatic arthritis; patients who score 3 or more out of 5 items on the psoriasis epidemiology screening tool (PEST) are deemed positive for psoriatic arthritis, Dr. Duffin noted.

Cardiovascular disease

Psoriasis patients are at increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, Dr. Duffin said. In fact, CV risk from severe psoriasis is similar to the risk conferred by diabetes.

She added that there is epidemiologic evidence for CV risk modification with several of the biologics approved for psoriasis.

Hypertension

Hypertension is prevalent and more severe in psoriasis patients, Dr. Duffin said, citing a 2011 case-control study of electronic medical records at the University of California, Davis. Psoriasis patients with hypertension were 5 times more likely than patients without psoriasis to be on one antihypertensive medication, 9.5 times more likely to be on two, and almost 20 times more likely to be on four antihypertensive medications (PLoS One. 2011 Mar 29;6[3]:e18227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018227).

Importantly, few primary care physicians and cardiologists are aware of the increased risk for hypertension in psoriasis patients.

Less than half (45%) of primary care physicians and 57% of cardiologists reported they were aware that psoriasis was associated with worse cardiovascular outcome, and only 43% of physicians reported screening psoriasis patients for hypertension starting at age 20 years, according to a 2012 survey of 251 physicians (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Sep;67[3]:357-62).

Dr. Duffin called on dermatologists to ensure that the primary care physicians they work with understand these increased risks.

“Commit to including a comment in consultation letters or letters back to primary care physicians that talks about the cardiovascular risks of the disease,” she said.

Dr. Duffin reported that she is a consultant and has received grant or contracted research support for many companies that manufacture dermatologic therapies.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Pay attention to comorbidities in your psoriasis patients because there may not be anyone else doing so.

“Many of our patients don’t have primary care physicians; many are untreated for psoriasis. They come to a clinical trial to get treated – some of them may not have insurance – so it is important for us to watch for these comorbidities,” Kristina C. Duffin, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

Yet, that does not seem to be happening consistently, according to Dr. Duffin, of the department of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. One in five dermatologists admitted to never screening or referring their psoriasis patients for management of cardiovascular risks in a 2015 survey (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.029).

Often patients at the start of biologic therapy are counseled about the risk for developing tuberculosis, yet the lifetime risk for doing so in the United States is 0.3%. Similarly, patients are often counseled on the risk for developing lymphoma, even though the excess risk for developing lymphoma that can be attributed to psoriasis treatment is 7.9 per 100,000 psoriasis patients per year. That screening seems to be driven by warnings issued in direct-to-consumer advertising, Dr. Duffin suggested.

“Although psoriasis patients have an increased relative risk of lymphoma, the absolute risk attributable to psoriasis is low,” Dr. Duffin pointed out.

Some of the comorbidities she advised dermatologists to watch for are described below.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is the most important psoriasis comorbidity, Dr. Duffin said. Between 20% and 30% of psoriasis patients will develop psoriatic arthritis.

In a study of 1,511 patients in 48 centers in Germany, 21% of psoriasis patients were diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis and of those, more than 95% had active arthritis and 53% had five or more affected joints (Br J Dermatol. 2009;160[5]:1040-7).

The GRAPPA app is an easy, free screening tool for psoriatic arthritis; patients who score 3 or more out of 5 items on the psoriasis epidemiology screening tool (PEST) are deemed positive for psoriatic arthritis, Dr. Duffin noted.

Cardiovascular disease

Psoriasis patients are at increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, Dr. Duffin said. In fact, CV risk from severe psoriasis is similar to the risk conferred by diabetes.

She added that there is epidemiologic evidence for CV risk modification with several of the biologics approved for psoriasis.

Hypertension

Hypertension is prevalent and more severe in psoriasis patients, Dr. Duffin said, citing a 2011 case-control study of electronic medical records at the University of California, Davis. Psoriasis patients with hypertension were 5 times more likely than patients without psoriasis to be on one antihypertensive medication, 9.5 times more likely to be on two, and almost 20 times more likely to be on four antihypertensive medications (PLoS One. 2011 Mar 29;6[3]:e18227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018227).

Importantly, few primary care physicians and cardiologists are aware of the increased risk for hypertension in psoriasis patients.

Less than half (45%) of primary care physicians and 57% of cardiologists reported they were aware that psoriasis was associated with worse cardiovascular outcome, and only 43% of physicians reported screening psoriasis patients for hypertension starting at age 20 years, according to a 2012 survey of 251 physicians (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Sep;67[3]:357-62).

Dr. Duffin called on dermatologists to ensure that the primary care physicians they work with understand these increased risks.

“Commit to including a comment in consultation letters or letters back to primary care physicians that talks about the cardiovascular risks of the disease,” she said.

Dr. Duffin reported that she is a consultant and has received grant or contracted research support for many companies that manufacture dermatologic therapies.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Remove Psoriasis Scales Gently

Myth: Pick Psoriasis Scales to Remove Them

Patients may be inclined to pick psoriasis scales that appear in noticeable areas or on the scalp. However, they should be counseled to avoid this practice, which could cause an infection. Instead, Dr. Steven Feldman (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) suggests putting on an ointment or oil-like medication to soften the scale. “Almost any kind of moisturizer will change the reflective properties of the scale so that you don’t see the scale,” he advised. He also suggested descaling agents such as topical salicylic acid or lactic acid. His patient education video is available on the American Academy of Dermatology website should you wish to direct your patients to it.

Because salicylic acid is a keratolytic (or peeling agent), it works by causing the outer layer of skin to shed. When applied topically, it helps to soften and lift psoriasis scales. Coal tar over-the-counter products also can be used for the same purpose. The over-the-counter product guide from the National Psoriasis Foundation is a valuable resource to share with patients.

Expert Commentary

I agree that it is very important to treat scale very gently. In addition to risk for infection, picking and traumatizing scale can lead to worsening of the psoriasis. This is known as the Koebner phenomenon. The phenomenon was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1876 as the formation of psoriatic lesions in uninvolved skin of patients with psoriasis after cutaneous trauma. This isomorphic phenomenon is now known to involve numerous diseases, among them vitiligo, lichen planus, and Darier disease.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg, MD (New York, New York)

Feldman S. How should I remove psoriasis scale? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Accessed October 31, 2018.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Over-the-counter products. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Published June 2017. Accessed October 31, 2018.

Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

Myth: Pick Psoriasis Scales to Remove Them

Patients may be inclined to pick psoriasis scales that appear in noticeable areas or on the scalp. However, they should be counseled to avoid this practice, which could cause an infection. Instead, Dr. Steven Feldman (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) suggests putting on an ointment or oil-like medication to soften the scale. “Almost any kind of moisturizer will change the reflective properties of the scale so that you don’t see the scale,” he advised. He also suggested descaling agents such as topical salicylic acid or lactic acid. His patient education video is available on the American Academy of Dermatology website should you wish to direct your patients to it.

Because salicylic acid is a keratolytic (or peeling agent), it works by causing the outer layer of skin to shed. When applied topically, it helps to soften and lift psoriasis scales. Coal tar over-the-counter products also can be used for the same purpose. The over-the-counter product guide from the National Psoriasis Foundation is a valuable resource to share with patients.

Expert Commentary

I agree that it is very important to treat scale very gently. In addition to risk for infection, picking and traumatizing scale can lead to worsening of the psoriasis. This is known as the Koebner phenomenon. The phenomenon was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1876 as the formation of psoriatic lesions in uninvolved skin of patients with psoriasis after cutaneous trauma. This isomorphic phenomenon is now known to involve numerous diseases, among them vitiligo, lichen planus, and Darier disease.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg, MD (New York, New York)

Myth: Pick Psoriasis Scales to Remove Them

Patients may be inclined to pick psoriasis scales that appear in noticeable areas or on the scalp. However, they should be counseled to avoid this practice, which could cause an infection. Instead, Dr. Steven Feldman (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) suggests putting on an ointment or oil-like medication to soften the scale. “Almost any kind of moisturizer will change the reflective properties of the scale so that you don’t see the scale,” he advised. He also suggested descaling agents such as topical salicylic acid or lactic acid. His patient education video is available on the American Academy of Dermatology website should you wish to direct your patients to it.

Because salicylic acid is a keratolytic (or peeling agent), it works by causing the outer layer of skin to shed. When applied topically, it helps to soften and lift psoriasis scales. Coal tar over-the-counter products also can be used for the same purpose. The over-the-counter product guide from the National Psoriasis Foundation is a valuable resource to share with patients.

Expert Commentary

I agree that it is very important to treat scale very gently. In addition to risk for infection, picking and traumatizing scale can lead to worsening of the psoriasis. This is known as the Koebner phenomenon. The phenomenon was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1876 as the formation of psoriatic lesions in uninvolved skin of patients with psoriasis after cutaneous trauma. This isomorphic phenomenon is now known to involve numerous diseases, among them vitiligo, lichen planus, and Darier disease.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg, MD (New York, New York)

Feldman S. How should I remove psoriasis scale? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Accessed October 31, 2018.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Over-the-counter products. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Published June 2017. Accessed October 31, 2018.

Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

Feldman S. How should I remove psoriasis scale? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Accessed October 31, 2018.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Over-the-counter products. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Published June 2017. Accessed October 31, 2018.

Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

Over one-third of psoriasis patients have PsA

Over one-third of psoriasis patients have PsA

About two-thirds of patients with psoriasis in a national registry also had psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and/or psoriasis in at least one challenging-to-treat (CTT) area, and one-quarter had both, according to Kristina Callis Duffin, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and her associates.

Their analysis included 2,042 psoriasis patients who were enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry between April 2015 and May 2018 and initiated biologic treatment during that time. The mean age was 49.6 years, 80% of the patients were white, and 51% were obese. Mean disease duration was 19.9 years and 89.2% of the patients had moderate to severe disease. CTT areas include the scalp, nails, and palmoplantar areas.

A total of 784 people in the cohort (38.4%) had PsA, 778 (38.1%) had scalp psoriasis, 326 (16.0%) had nail psoriasis, 223 (10.9%) had palmoplantar psoriasis, and 535 (26.2%) had both PsA and psoriasis in at least two CTT areas. The most common combinations were PsA plus scalp psoriasis and PsA plus nail and scalp psoriasis.

“These results indicate a need to further characterize patients with psoriasis who have PsA and CTT areas and evaluate the impact of these factors to better understand their treatment needs,” the investigators noted.

The Corrona registry has been supported by numerous pharmaceutical companies, and the study authors reported numerous financial relationships with industry; two authors are Novartis employees.

Secukinumab effective for slowing radiographic progression in active PsA

Treatment with secukinumab significantly reduced radiographic progression in patients with active PsA, according to Désirée van der Heijde, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at Leiden University Medical Center, and her associates.

The results come from an analysis of the FUTURE 5 trial, a study of 996 patients with active PsA despite previous NSAID treatment, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment, or anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. Patients were randomized to receive 300 mg subcutaneous secukinumab with loading dose, 150 mg secukinumab with loading dose, 150 mg secukinumab without loading dose, or placebo, at baseline; weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4; then every 4 weeks.

After 24 weeks, the mean change in van der Heijde–modified Total Sharp Score for PsA was 0.08 for the 300-mg secukinumab group (P less than .01), 0.17 for the 150-mg secukinumab with loading dose group (P less than .05), a reduction of 0.09 for the 150-mg secukinumab without loading dose group (P less than .01), and 0.50 for the placebo group. Lower radiographic progression was seen regardless of prior anti-TNF or concomitant methotrexate treatment.

The study was funded by Novartis. The study authors reported financial disclosures with numerous companies; five authors are Novartis employees.

Tildrakizumab sustains efficacy in plaque psoriasis treatment after 1 year

Nearly all patients receiving the interleukin-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis maintained or improved their Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response rate after 52 weeks of treatment, compared with their response after 28 weeks.

The analysis, conducted by Boni E. Elewski, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and her associates, included 352 patients who received 100 mg tildrakizumab and 313 who received 200 mg tildrakizumab. Treatment was received at baseline, at 4 weeks, and then every 12 weeks afterward.

At week 28, the proportions of patients achieving PASI 100, PASI 90-99, PASI 75-89, and PASI 50-74 at week 28 were 25.9%, 38.4%, 25.3%, and 10.5%, respectively, among those treated with the 100-mg dose. The proportions were 24.6%, 24.3%, 19.5%, and 31.6%, respectively, among those treated with the 200-mg dose.

In patients who achieved at least PASI 90 on either dose at week 28, 88.9%-89.4% maintained that response at week 52. For patients with PASI 75-89, 39.3%-40.4% maintained that response and 33.7%-41.0% achieved a PASI 90 response. At week 52, in patients with PASI 50-74, 20.2%-29.7% achieved at least a PASI 90, 52.5%-64.9% achieved PASI 75, and only 2.6% of patients on either dose had fallen below PASI 50.

Four study authors reported being clinical investigators on studies sponsored by Merck and Sun Pharmaceuticals; five authors are employees of Sun Pharmaceuticals.

Halobetasol/tazarotene combination most effective for plaque psoriasis treatment

A fixed combination of halobetasol propionate 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045% lotion provided a synergistic effect over either component on its own for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and his associates.

The investigators performed a post hoc analysis of 212 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis randomized to receive either the halobetasol/tazarotene combination, halobetasol only, tazarotene only, or vehicle only for 8 weeks, with follow-up at 12 weeks. Treatment success was based on the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score, IGA scores of “clear” or “almost clear,” and percent change from baseline in IGA multiplied by Body Surface Area (BSA) composite score (IGAxBSA). “Synergy was calculated by summing up the contribution of the individual active ingredients (HP and TAZ) to overall efficacy and comparing to the efficacy achieved with HP/TAZ lotion relative to vehicle,” the authors explained.

Relative to vehicle, treatment success for halobetasol/tazarotene after 8 weeks was 42.8%, 23.6% for halobetasol alone, and 9.0% for tazarotene alone. After 12 weeks, the difference was 31.3%, 14.1%, and 5.9%, respectively. The percent change in IGAxBSA scores from baseline after 8 weeks, relative to vehicle, were 51.6%, 37.3%, and 3.3%, respectively. After 12 weeks, the change was 47.3%, 25.7%, and 8.6%, respectively.

After 8 weeks, the synergy ratio for treatment success and IGAxBSA scores for the halobetasol/tazarotene combination was 1.3. After 12 weeks, the synergy ratio for treatment success was 1.6 and the ratio for IGAxBSA scores was 1.4.

“By combining two agents into one once-daily formulation, this novel formulation reduces the number of product applications and may help patient adherence,” the study authors noted.

Dr. Kircik reported serving as a consultant and investigator for Valeant Pharmaceuticals. One study author is an employee of Bausch Health and Ortho Dermatologics, and another is an employee of Dow Pharmaceutical Sciences (a division of Valeant).

Brodalumab demonstrates low immunogenicity in moderate to severe psoriasis

The immunogenicity of brodalumab in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis was low and did not compromise the efficacy or safety profile of the drug, according to Kristian Reich, MD, of Dermatologikum Berlin and SCIderm Research Institute in Hamburg, Germany, and his associates.

Data from a 12-week, phase 2 trial with a 352-week, open-label extension and three 52-week phase 3 trials were included in the analysis. Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) were tested, and positive samples were further analyzed for neutralizing ADAs by a cell-based assay.

Out of the 4,461 patients who received brodalumab, 122 (2.7%) were positive for ADAs after starting brodalumab. The incidence rate ranged from 1.9% to 3.4% between all dosing groups (140 mg, 210 mg, variable dosing, and 210 mg of brodalumab after ustekinumab). In 58 (1.4%) of patients, ADAs were transient. No patients had neutralizing ADAs, and no evidence of altered pharmacokinetics, loss of efficacy, or changes in the safety profile of brodalumab in subjects positive for ADAs was seen.

No significant difference was seen in the incidence rate of hypersensitivity or injection site reactions in brodalumab, compared with placebo or ustekinumab. The most common injection site reactions were injection site pain, erythema, and bruising.

The study was supported by Amgen. The study authors reported numerous disclosures. Two authors are employees of Leo Pharma, one author is a former employee of the company.

Secukinumab improves patient-reported outcomes in CTT psoriasis

Treatment with secukinumab significantly improved patient-reported outcomes such as fatigue, itch, pain, and quality of life measures in patients with CTT psoriasis after 6 months, according to Jerry Bagel, MD, of the Psoriasis Treatment Center of Central New Jersey, East Windsor, and his associates.

A total of 68 patients with psoriasis localized to at least one CTT area who were enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry from April 15, 2015, through May 10, 2018, and were receiving secukinumab for the entirety of the 6-month study period were included in the analysis. Patient-reported outcomes included in the analysis were fatigue, itch, pain, Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI) score, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) scale.

The mean age at enrollment was 51.2 years and almost 80% of patients were white. Mean psoriasis duration was 21.8 years and nearly half had PsA.

Visual analog scale scores improved over baseline for fatigue (mean, 23.2 vs. 33.2; P = .01), itch (20.9 vs. 49.6; P less than .0001), and pain (12.1 vs. 33.8; P less than .0001). DLQI scores also improved (2.9 vs. 8.1; P less than .0001), and the proportion of patients who reported that psoriasis had at least a moderate effect on their life was reduced after 6 months (22.1% vs. 59.7%; P less than .0001).

Based on WPAI results, patients experienced significant improvements in the percentage of daily activities impaired (mean, 9.5% vs 17.5%; P = .0075); of the 42 patients who were employed, both impairment percentage (3.7% vs. 11.2%; P = .0148) and percentage of work hours affected (4.9% vs. 11.9%; P = .0486) were reduced from baseline.

“These results are consistent with previous reports from secukinumab clinical trials; however, additional real-world studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of secukinumab for improving [patient-reported outcomes] in patients with psoriasis in CTT areas,” the authors noted.

The Corrona registry has been supported by numerous pharmaceutical companies, and several study authors reported various disclosures with industry. Two authors are Novartis employees. The study was supported by Novartis; the company participated in the interpretation of data and review and approval of the abstract.

These posters were presented at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Over one-third of psoriasis patients have PsA

About two-thirds of patients with psoriasis in a national registry also had psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and/or psoriasis in at least one challenging-to-treat (CTT) area, and one-quarter had both, according to Kristina Callis Duffin, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and her associates.

Their analysis included 2,042 psoriasis patients who were enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry between April 2015 and May 2018 and initiated biologic treatment during that time. The mean age was 49.6 years, 80% of the patients were white, and 51% were obese. Mean disease duration was 19.9 years and 89.2% of the patients had moderate to severe disease. CTT areas include the scalp, nails, and palmoplantar areas.

A total of 784 people in the cohort (38.4%) had PsA, 778 (38.1%) had scalp psoriasis, 326 (16.0%) had nail psoriasis, 223 (10.9%) had palmoplantar psoriasis, and 535 (26.2%) had both PsA and psoriasis in at least two CTT areas. The most common combinations were PsA plus scalp psoriasis and PsA plus nail and scalp psoriasis.

“These results indicate a need to further characterize patients with psoriasis who have PsA and CTT areas and evaluate the impact of these factors to better understand their treatment needs,” the investigators noted.

The Corrona registry has been supported by numerous pharmaceutical companies, and the study authors reported numerous financial relationships with industry; two authors are Novartis employees.

Secukinumab effective for slowing radiographic progression in active PsA

Treatment with secukinumab significantly reduced radiographic progression in patients with active PsA, according to Désirée van der Heijde, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at Leiden University Medical Center, and her associates.

The results come from an analysis of the FUTURE 5 trial, a study of 996 patients with active PsA despite previous NSAID treatment, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment, or anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. Patients were randomized to receive 300 mg subcutaneous secukinumab with loading dose, 150 mg secukinumab with loading dose, 150 mg secukinumab without loading dose, or placebo, at baseline; weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4; then every 4 weeks.

After 24 weeks, the mean change in van der Heijde–modified Total Sharp Score for PsA was 0.08 for the 300-mg secukinumab group (P less than .01), 0.17 for the 150-mg secukinumab with loading dose group (P less than .05), a reduction of 0.09 for the 150-mg secukinumab without loading dose group (P less than .01), and 0.50 for the placebo group. Lower radiographic progression was seen regardless of prior anti-TNF or concomitant methotrexate treatment.

The study was funded by Novartis. The study authors reported financial disclosures with numerous companies; five authors are Novartis employees.

Tildrakizumab sustains efficacy in plaque psoriasis treatment after 1 year

Nearly all patients receiving the interleukin-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis maintained or improved their Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response rate after 52 weeks of treatment, compared with their response after 28 weeks.

The analysis, conducted by Boni E. Elewski, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and her associates, included 352 patients who received 100 mg tildrakizumab and 313 who received 200 mg tildrakizumab. Treatment was received at baseline, at 4 weeks, and then every 12 weeks afterward.

At week 28, the proportions of patients achieving PASI 100, PASI 90-99, PASI 75-89, and PASI 50-74 at week 28 were 25.9%, 38.4%, 25.3%, and 10.5%, respectively, among those treated with the 100-mg dose. The proportions were 24.6%, 24.3%, 19.5%, and 31.6%, respectively, among those treated with the 200-mg dose.

In patients who achieved at least PASI 90 on either dose at week 28, 88.9%-89.4% maintained that response at week 52. For patients with PASI 75-89, 39.3%-40.4% maintained that response and 33.7%-41.0% achieved a PASI 90 response. At week 52, in patients with PASI 50-74, 20.2%-29.7% achieved at least a PASI 90, 52.5%-64.9% achieved PASI 75, and only 2.6% of patients on either dose had fallen below PASI 50.

Four study authors reported being clinical investigators on studies sponsored by Merck and Sun Pharmaceuticals; five authors are employees of Sun Pharmaceuticals.

Halobetasol/tazarotene combination most effective for plaque psoriasis treatment

A fixed combination of halobetasol propionate 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045% lotion provided a synergistic effect over either component on its own for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and his associates.

The investigators performed a post hoc analysis of 212 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis randomized to receive either the halobetasol/tazarotene combination, halobetasol only, tazarotene only, or vehicle only for 8 weeks, with follow-up at 12 weeks. Treatment success was based on the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score, IGA scores of “clear” or “almost clear,” and percent change from baseline in IGA multiplied by Body Surface Area (BSA) composite score (IGAxBSA). “Synergy was calculated by summing up the contribution of the individual active ingredients (HP and TAZ) to overall efficacy and comparing to the efficacy achieved with HP/TAZ lotion relative to vehicle,” the authors explained.

Relative to vehicle, treatment success for halobetasol/tazarotene after 8 weeks was 42.8%, 23.6% for halobetasol alone, and 9.0% for tazarotene alone. After 12 weeks, the difference was 31.3%, 14.1%, and 5.9%, respectively. The percent change in IGAxBSA scores from baseline after 8 weeks, relative to vehicle, were 51.6%, 37.3%, and 3.3%, respectively. After 12 weeks, the change was 47.3%, 25.7%, and 8.6%, respectively.

After 8 weeks, the synergy ratio for treatment success and IGAxBSA scores for the halobetasol/tazarotene combination was 1.3. After 12 weeks, the synergy ratio for treatment success was 1.6 and the ratio for IGAxBSA scores was 1.4.

“By combining two agents into one once-daily formulation, this novel formulation reduces the number of product applications and may help patient adherence,” the study authors noted.

Dr. Kircik reported serving as a consultant and investigator for Valeant Pharmaceuticals. One study author is an employee of Bausch Health and Ortho Dermatologics, and another is an employee of Dow Pharmaceutical Sciences (a division of Valeant).

Brodalumab demonstrates low immunogenicity in moderate to severe psoriasis

The immunogenicity of brodalumab in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis was low and did not compromise the efficacy or safety profile of the drug, according to Kristian Reich, MD, of Dermatologikum Berlin and SCIderm Research Institute in Hamburg, Germany, and his associates.

Data from a 12-week, phase 2 trial with a 352-week, open-label extension and three 52-week phase 3 trials were included in the analysis. Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) were tested, and positive samples were further analyzed for neutralizing ADAs by a cell-based assay.

Out of the 4,461 patients who received brodalumab, 122 (2.7%) were positive for ADAs after starting brodalumab. The incidence rate ranged from 1.9% to 3.4% between all dosing groups (140 mg, 210 mg, variable dosing, and 210 mg of brodalumab after ustekinumab). In 58 (1.4%) of patients, ADAs were transient. No patients had neutralizing ADAs, and no evidence of altered pharmacokinetics, loss of efficacy, or changes in the safety profile of brodalumab in subjects positive for ADAs was seen.

No significant difference was seen in the incidence rate of hypersensitivity or injection site reactions in brodalumab, compared with placebo or ustekinumab. The most common injection site reactions were injection site pain, erythema, and bruising.

The study was supported by Amgen. The study authors reported numerous disclosures. Two authors are employees of Leo Pharma, one author is a former employee of the company.

Secukinumab improves patient-reported outcomes in CTT psoriasis

Treatment with secukinumab significantly improved patient-reported outcomes such as fatigue, itch, pain, and quality of life measures in patients with CTT psoriasis after 6 months, according to Jerry Bagel, MD, of the Psoriasis Treatment Center of Central New Jersey, East Windsor, and his associates.

A total of 68 patients with psoriasis localized to at least one CTT area who were enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry from April 15, 2015, through May 10, 2018, and were receiving secukinumab for the entirety of the 6-month study period were included in the analysis. Patient-reported outcomes included in the analysis were fatigue, itch, pain, Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI) score, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) scale.

The mean age at enrollment was 51.2 years and almost 80% of patients were white. Mean psoriasis duration was 21.8 years and nearly half had PsA.

Visual analog scale scores improved over baseline for fatigue (mean, 23.2 vs. 33.2; P = .01), itch (20.9 vs. 49.6; P less than .0001), and pain (12.1 vs. 33.8; P less than .0001). DLQI scores also improved (2.9 vs. 8.1; P less than .0001), and the proportion of patients who reported that psoriasis had at least a moderate effect on their life was reduced after 6 months (22.1% vs. 59.7%; P less than .0001).

Based on WPAI results, patients experienced significant improvements in the percentage of daily activities impaired (mean, 9.5% vs 17.5%; P = .0075); of the 42 patients who were employed, both impairment percentage (3.7% vs. 11.2%; P = .0148) and percentage of work hours affected (4.9% vs. 11.9%; P = .0486) were reduced from baseline.

“These results are consistent with previous reports from secukinumab clinical trials; however, additional real-world studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of secukinumab for improving [patient-reported outcomes] in patients with psoriasis in CTT areas,” the authors noted.

The Corrona registry has been supported by numerous pharmaceutical companies, and several study authors reported various disclosures with industry. Two authors are Novartis employees. The study was supported by Novartis; the company participated in the interpretation of data and review and approval of the abstract.

These posters were presented at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Over one-third of psoriasis patients have PsA

About two-thirds of patients with psoriasis in a national registry also had psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and/or psoriasis in at least one challenging-to-treat (CTT) area, and one-quarter had both, according to Kristina Callis Duffin, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and her associates.

Their analysis included 2,042 psoriasis patients who were enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry between April 2015 and May 2018 and initiated biologic treatment during that time. The mean age was 49.6 years, 80% of the patients were white, and 51% were obese. Mean disease duration was 19.9 years and 89.2% of the patients had moderate to severe disease. CTT areas include the scalp, nails, and palmoplantar areas.

A total of 784 people in the cohort (38.4%) had PsA, 778 (38.1%) had scalp psoriasis, 326 (16.0%) had nail psoriasis, 223 (10.9%) had palmoplantar psoriasis, and 535 (26.2%) had both PsA and psoriasis in at least two CTT areas. The most common combinations were PsA plus scalp psoriasis and PsA plus nail and scalp psoriasis.

“These results indicate a need to further characterize patients with psoriasis who have PsA and CTT areas and evaluate the impact of these factors to better understand their treatment needs,” the investigators noted.

The Corrona registry has been supported by numerous pharmaceutical companies, and the study authors reported numerous financial relationships with industry; two authors are Novartis employees.

Secukinumab effective for slowing radiographic progression in active PsA

Treatment with secukinumab significantly reduced radiographic progression in patients with active PsA, according to Désirée van der Heijde, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at Leiden University Medical Center, and her associates.

The results come from an analysis of the FUTURE 5 trial, a study of 996 patients with active PsA despite previous NSAID treatment, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment, or anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. Patients were randomized to receive 300 mg subcutaneous secukinumab with loading dose, 150 mg secukinumab with loading dose, 150 mg secukinumab without loading dose, or placebo, at baseline; weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4; then every 4 weeks.

After 24 weeks, the mean change in van der Heijde–modified Total Sharp Score for PsA was 0.08 for the 300-mg secukinumab group (P less than .01), 0.17 for the 150-mg secukinumab with loading dose group (P less than .05), a reduction of 0.09 for the 150-mg secukinumab without loading dose group (P less than .01), and 0.50 for the placebo group. Lower radiographic progression was seen regardless of prior anti-TNF or concomitant methotrexate treatment.

The study was funded by Novartis. The study authors reported financial disclosures with numerous companies; five authors are Novartis employees.

Tildrakizumab sustains efficacy in plaque psoriasis treatment after 1 year

Nearly all patients receiving the interleukin-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis maintained or improved their Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response rate after 52 weeks of treatment, compared with their response after 28 weeks.

The analysis, conducted by Boni E. Elewski, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and her associates, included 352 patients who received 100 mg tildrakizumab and 313 who received 200 mg tildrakizumab. Treatment was received at baseline, at 4 weeks, and then every 12 weeks afterward.

At week 28, the proportions of patients achieving PASI 100, PASI 90-99, PASI 75-89, and PASI 50-74 at week 28 were 25.9%, 38.4%, 25.3%, and 10.5%, respectively, among those treated with the 100-mg dose. The proportions were 24.6%, 24.3%, 19.5%, and 31.6%, respectively, among those treated with the 200-mg dose.

In patients who achieved at least PASI 90 on either dose at week 28, 88.9%-89.4% maintained that response at week 52. For patients with PASI 75-89, 39.3%-40.4% maintained that response and 33.7%-41.0% achieved a PASI 90 response. At week 52, in patients with PASI 50-74, 20.2%-29.7% achieved at least a PASI 90, 52.5%-64.9% achieved PASI 75, and only 2.6% of patients on either dose had fallen below PASI 50.

Four study authors reported being clinical investigators on studies sponsored by Merck and Sun Pharmaceuticals; five authors are employees of Sun Pharmaceuticals.

Halobetasol/tazarotene combination most effective for plaque psoriasis treatment

A fixed combination of halobetasol propionate 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045% lotion provided a synergistic effect over either component on its own for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and his associates.

The investigators performed a post hoc analysis of 212 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis randomized to receive either the halobetasol/tazarotene combination, halobetasol only, tazarotene only, or vehicle only for 8 weeks, with follow-up at 12 weeks. Treatment success was based on the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score, IGA scores of “clear” or “almost clear,” and percent change from baseline in IGA multiplied by Body Surface Area (BSA) composite score (IGAxBSA). “Synergy was calculated by summing up the contribution of the individual active ingredients (HP and TAZ) to overall efficacy and comparing to the efficacy achieved with HP/TAZ lotion relative to vehicle,” the authors explained.

Relative to vehicle, treatment success for halobetasol/tazarotene after 8 weeks was 42.8%, 23.6% for halobetasol alone, and 9.0% for tazarotene alone. After 12 weeks, the difference was 31.3%, 14.1%, and 5.9%, respectively. The percent change in IGAxBSA scores from baseline after 8 weeks, relative to vehicle, were 51.6%, 37.3%, and 3.3%, respectively. After 12 weeks, the change was 47.3%, 25.7%, and 8.6%, respectively.

After 8 weeks, the synergy ratio for treatment success and IGAxBSA scores for the halobetasol/tazarotene combination was 1.3. After 12 weeks, the synergy ratio for treatment success was 1.6 and the ratio for IGAxBSA scores was 1.4.

“By combining two agents into one once-daily formulation, this novel formulation reduces the number of product applications and may help patient adherence,” the study authors noted.

Dr. Kircik reported serving as a consultant and investigator for Valeant Pharmaceuticals. One study author is an employee of Bausch Health and Ortho Dermatologics, and another is an employee of Dow Pharmaceutical Sciences (a division of Valeant).

Brodalumab demonstrates low immunogenicity in moderate to severe psoriasis

The immunogenicity of brodalumab in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis was low and did not compromise the efficacy or safety profile of the drug, according to Kristian Reich, MD, of Dermatologikum Berlin and SCIderm Research Institute in Hamburg, Germany, and his associates.

Data from a 12-week, phase 2 trial with a 352-week, open-label extension and three 52-week phase 3 trials were included in the analysis. Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) were tested, and positive samples were further analyzed for neutralizing ADAs by a cell-based assay.

Out of the 4,461 patients who received brodalumab, 122 (2.7%) were positive for ADAs after starting brodalumab. The incidence rate ranged from 1.9% to 3.4% between all dosing groups (140 mg, 210 mg, variable dosing, and 210 mg of brodalumab after ustekinumab). In 58 (1.4%) of patients, ADAs were transient. No patients had neutralizing ADAs, and no evidence of altered pharmacokinetics, loss of efficacy, or changes in the safety profile of brodalumab in subjects positive for ADAs was seen.

No significant difference was seen in the incidence rate of hypersensitivity or injection site reactions in brodalumab, compared with placebo or ustekinumab. The most common injection site reactions were injection site pain, erythema, and bruising.

The study was supported by Amgen. The study authors reported numerous disclosures. Two authors are employees of Leo Pharma, one author is a former employee of the company.

Secukinumab improves patient-reported outcomes in CTT psoriasis

Treatment with secukinumab significantly improved patient-reported outcomes such as fatigue, itch, pain, and quality of life measures in patients with CTT psoriasis after 6 months, according to Jerry Bagel, MD, of the Psoriasis Treatment Center of Central New Jersey, East Windsor, and his associates.

A total of 68 patients with psoriasis localized to at least one CTT area who were enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry from April 15, 2015, through May 10, 2018, and were receiving secukinumab for the entirety of the 6-month study period were included in the analysis. Patient-reported outcomes included in the analysis were fatigue, itch, pain, Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI) score, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) scale.

The mean age at enrollment was 51.2 years and almost 80% of patients were white. Mean psoriasis duration was 21.8 years and nearly half had PsA.

Visual analog scale scores improved over baseline for fatigue (mean, 23.2 vs. 33.2; P = .01), itch (20.9 vs. 49.6; P less than .0001), and pain (12.1 vs. 33.8; P less than .0001). DLQI scores also improved (2.9 vs. 8.1; P less than .0001), and the proportion of patients who reported that psoriasis had at least a moderate effect on their life was reduced after 6 months (22.1% vs. 59.7%; P less than .0001).

Based on WPAI results, patients experienced significant improvements in the percentage of daily activities impaired (mean, 9.5% vs 17.5%; P = .0075); of the 42 patients who were employed, both impairment percentage (3.7% vs. 11.2%; P = .0148) and percentage of work hours affected (4.9% vs. 11.9%; P = .0486) were reduced from baseline.

“These results are consistent with previous reports from secukinumab clinical trials; however, additional real-world studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of secukinumab for improving [patient-reported outcomes] in patients with psoriasis in CTT areas,” the authors noted.

The Corrona registry has been supported by numerous pharmaceutical companies, and several study authors reported various disclosures with industry. Two authors are Novartis employees. The study was supported by Novartis; the company participated in the interpretation of data and review and approval of the abstract.

These posters were presented at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

FDA approves adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) for a variety of conditions, according to Sandoz, the drug’s manufacturer and a division of Novartis.

FDA approval for Hyrimoz is based on a randomized, double-blind, three-arm, parallel biosimilarity study that demonstrated equivalence for all primary pharmacokinetic parameters, according to the press release. A second study confirmed these results in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with Hyrimoz having a safety profile similar to that of adalimumab. Hyrimoz was approved in Europe in July 2018.

Hyrimoz has been approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patients aged 4 years and older, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The most common adverse events associated with the drug, according to the label, are infections, injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

Hyrimoz is the third adalimumab biosimilar approved by the FDA.

“Biosimilars can help people suffering from chronic, debilitating conditions gain expanded access to important medicines that may change the outcome of their disease. With the FDA approval of Hyrimoz, Sandoz is one step closer to offering U.S. patients with autoimmune diseases the same critical access already available in Europe,” Stefan Hendriks, global head of biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Novartis website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) for a variety of conditions, according to Sandoz, the drug’s manufacturer and a division of Novartis.

FDA approval for Hyrimoz is based on a randomized, double-blind, three-arm, parallel biosimilarity study that demonstrated equivalence for all primary pharmacokinetic parameters, according to the press release. A second study confirmed these results in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with Hyrimoz having a safety profile similar to that of adalimumab. Hyrimoz was approved in Europe in July 2018.

Hyrimoz has been approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patients aged 4 years and older, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The most common adverse events associated with the drug, according to the label, are infections, injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

Hyrimoz is the third adalimumab biosimilar approved by the FDA.

“Biosimilars can help people suffering from chronic, debilitating conditions gain expanded access to important medicines that may change the outcome of their disease. With the FDA approval of Hyrimoz, Sandoz is one step closer to offering U.S. patients with autoimmune diseases the same critical access already available in Europe,” Stefan Hendriks, global head of biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Novartis website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) for a variety of conditions, according to Sandoz, the drug’s manufacturer and a division of Novartis.

FDA approval for Hyrimoz is based on a randomized, double-blind, three-arm, parallel biosimilarity study that demonstrated equivalence for all primary pharmacokinetic parameters, according to the press release. A second study confirmed these results in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with Hyrimoz having a safety profile similar to that of adalimumab. Hyrimoz was approved in Europe in July 2018.

Hyrimoz has been approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patients aged 4 years and older, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The most common adverse events associated with the drug, according to the label, are infections, injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

Hyrimoz is the third adalimumab biosimilar approved by the FDA.

“Biosimilars can help people suffering from chronic, debilitating conditions gain expanded access to important medicines that may change the outcome of their disease. With the FDA approval of Hyrimoz, Sandoz is one step closer to offering U.S. patients with autoimmune diseases the same critical access already available in Europe,” Stefan Hendriks, global head of biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Novartis website.

Psoriasis adds to increased risk of cardiovascular procedures, surgery in patients with hypertension

compared with patients with hypertension alone.

“The results suggested that hypertensive patients with concurrent psoriasis experienced an earlier and more aggressive disease progression of hypertension, compared with general hypertensive patients,” Hsien-Yi Chiu, MD, PhD, from the department of dermatology at the National Taiwan University Hospital in Hsinchu, Taiwan, and his colleagues wrote in the Journal of Dermatology. “Thus, patients with hypertension and psoriasis should be considered for more aggressive strategies for prevention of primary [cardiovascular disease] and more intense assessments for cardiovascular interventions needed to improve [cardiovascular disease] outcome in these patients.”

They performed a nationwide cohort study of patients in the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database with new onset hypertension from 2005 to 2006. Those with psoriasis (4,039 patients) were matched by age and sex to patients in the database who were diagnosed with hypertension but not psoriasis; the mean follow-up was 5.62 years. Their mean age was 58 years and about 31% of the psoriasis cohort were female. They were divided into groups based on psoriasis severity (mild and severe psoriasis) and type (psoriasis with and without arthritis). Researchers noted patients with both psoriasis and hypertension also had higher rates of cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus during the year prior to the study.

The outcome measured was having a cardiovascular procedure (percutaneous coronary intervention with/without stenting or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and transcatheter radiofrequency ablation for arrhythmia) and cardiovascular surgery (coronary artery bypass grafting and other surgery for heart valves, arrhythmia, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vessels, and the aorta).

Patients with both psoriasis and hypertension were at an increased risk for having a cardiovascular procedure and surgery (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.53), compared with patients with only hypertension. The risk of this outcome was also increased among patients with severe psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, compared with patients who had mild psoriasis (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.98-1.51) and with patients with psoriasis but not arthritis (aHR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.84-1.58); however, the results did not reach statistical significance after adjustment, which the researchers attributed to the small subgroup size.

“Another possible explanation was that the observed increased requirement for cardiovascular procedure and surgery in patients with severe psoriasis was mediated by a complex interplay among inflammation, traditional risk factors for [cardiovascular disease], and antirheumatic drugs, which probably attenuate the effects conferred by psoriasis,” the authors wrote.

Limitations in the study included reliance on administrative claims data for psoriasis diagnosis, unavailability of some details of the cardiovascular procedures and surgery, lack of blood pressure data to identify hypertension severity, as well as unmeasured factors and confounders. Further, “comparative occurrence of a requirement for cardiovascular procedure and surgery in the two groups may be influenced by a competing risk for death,” the researchers noted.

This study was supported in part through grants by the National Taiwan University Hospital, Asia-Pacific La Roche–Posay Foundation 2014, and the Ministry of Science and Technology. Dr. Chiu is on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Another author has conducted clinical trials for or received fees for being a consultant or speaker for companies that include Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Celgene. The remaining authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Chiu H-Y et al. J Dermatol. 2018 Oct 16. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14654.

compared with patients with hypertension alone.

“The results suggested that hypertensive patients with concurrent psoriasis experienced an earlier and more aggressive disease progression of hypertension, compared with general hypertensive patients,” Hsien-Yi Chiu, MD, PhD, from the department of dermatology at the National Taiwan University Hospital in Hsinchu, Taiwan, and his colleagues wrote in the Journal of Dermatology. “Thus, patients with hypertension and psoriasis should be considered for more aggressive strategies for prevention of primary [cardiovascular disease] and more intense assessments for cardiovascular interventions needed to improve [cardiovascular disease] outcome in these patients.”

They performed a nationwide cohort study of patients in the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database with new onset hypertension from 2005 to 2006. Those with psoriasis (4,039 patients) were matched by age and sex to patients in the database who were diagnosed with hypertension but not psoriasis; the mean follow-up was 5.62 years. Their mean age was 58 years and about 31% of the psoriasis cohort were female. They were divided into groups based on psoriasis severity (mild and severe psoriasis) and type (psoriasis with and without arthritis). Researchers noted patients with both psoriasis and hypertension also had higher rates of cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus during the year prior to the study.

The outcome measured was having a cardiovascular procedure (percutaneous coronary intervention with/without stenting or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and transcatheter radiofrequency ablation for arrhythmia) and cardiovascular surgery (coronary artery bypass grafting and other surgery for heart valves, arrhythmia, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vessels, and the aorta).

Patients with both psoriasis and hypertension were at an increased risk for having a cardiovascular procedure and surgery (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.53), compared with patients with only hypertension. The risk of this outcome was also increased among patients with severe psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, compared with patients who had mild psoriasis (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.98-1.51) and with patients with psoriasis but not arthritis (aHR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.84-1.58); however, the results did not reach statistical significance after adjustment, which the researchers attributed to the small subgroup size.

“Another possible explanation was that the observed increased requirement for cardiovascular procedure and surgery in patients with severe psoriasis was mediated by a complex interplay among inflammation, traditional risk factors for [cardiovascular disease], and antirheumatic drugs, which probably attenuate the effects conferred by psoriasis,” the authors wrote.

Limitations in the study included reliance on administrative claims data for psoriasis diagnosis, unavailability of some details of the cardiovascular procedures and surgery, lack of blood pressure data to identify hypertension severity, as well as unmeasured factors and confounders. Further, “comparative occurrence of a requirement for cardiovascular procedure and surgery in the two groups may be influenced by a competing risk for death,” the researchers noted.

This study was supported in part through grants by the National Taiwan University Hospital, Asia-Pacific La Roche–Posay Foundation 2014, and the Ministry of Science and Technology. Dr. Chiu is on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Another author has conducted clinical trials for or received fees for being a consultant or speaker for companies that include Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Celgene. The remaining authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Chiu H-Y et al. J Dermatol. 2018 Oct 16. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14654.

compared with patients with hypertension alone.