User login

A Review of Neurologic Complications of Biologic Therapy in Plaque Psoriasis

Biologic agents have provided patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with treatment alternatives that have improved systemic safety profiles and disease control1; however, case reports of associated neurologic complications have been emerging. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors have been associated with central and peripheral demyelinating disorders. Notably, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market for its association with fatal cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).2,3 It is imperative for dermatologists to be familiar with the clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnostic criteria of neurologic complications of biologic agents used in the treatment of psoriasis.

Leukoencephalopathy

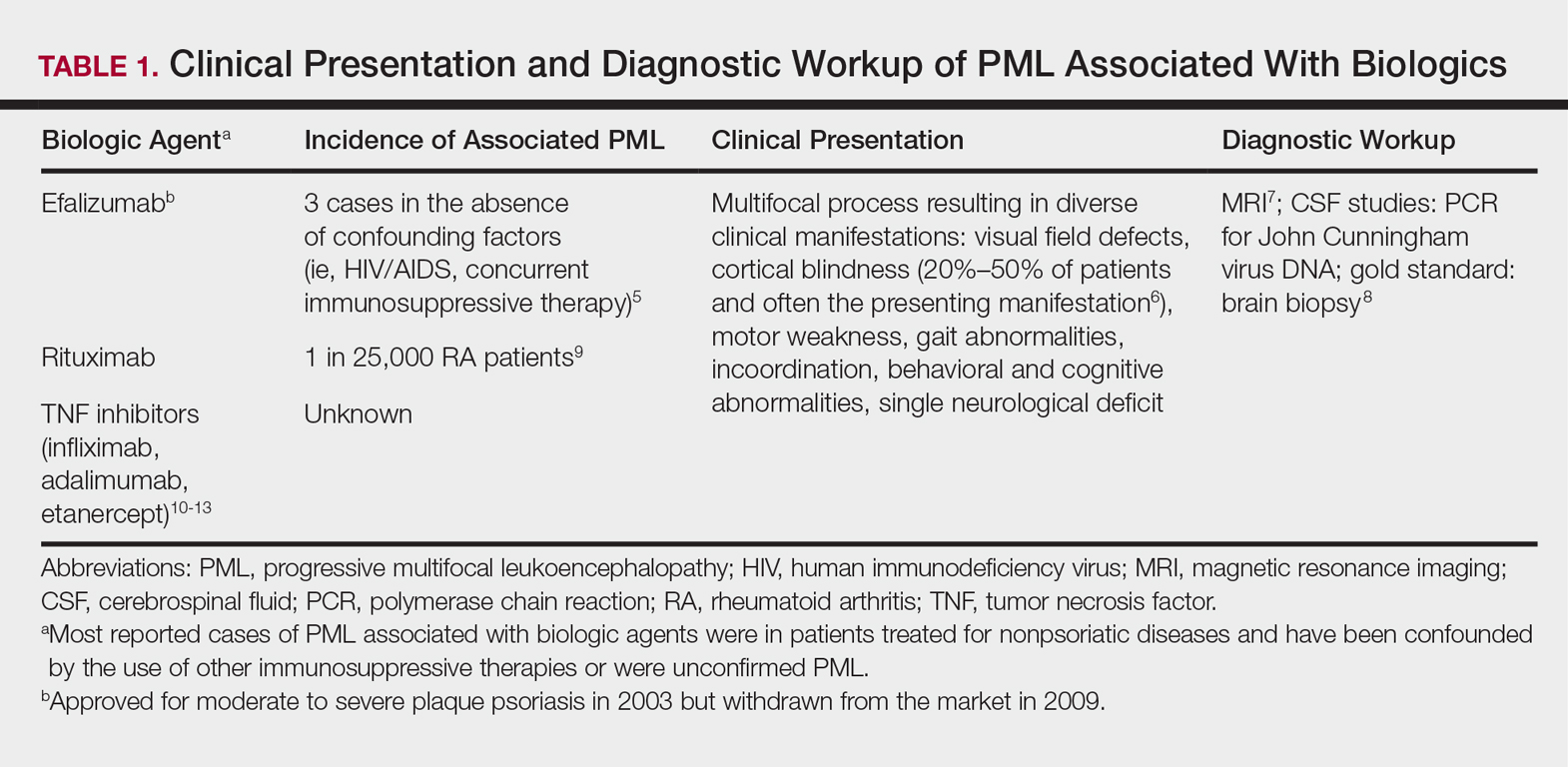

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a fatal demyelinating neurodegenerative disease caused by reactivation of the ubiquitous John Cunningham virus. Primary asymptomatic infection is thought to occur during childhood, then the virus remains latent. Reactivation usually occurs during severe immunosuppression and is classically described in human immunodeficiency virus infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and other forms of cancer.4 A summary of PML and its association with biologics is found in Table 1.5-13 Few case reports of TNF-α inhibitor–associated PML exist, mostly in the presence of confounding factors such as immunosuppression or underlying autoimmune disease.10-13 Presenting symptoms of PML often are subacute, rapidly progressive, and can be focal or multifocal and include motor, cognitive, and visual deficits. Of note, there are 2 reported cases of ustekinumab associated with reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, which is a hypertensive encephalopathy characterized by headache, altered mental status, vision abnormalities, and seizures.14,15 Fortunately, this disease is reversible with blood pressure control and removal of the immunosuppressive agent.16

Demyelinating Disorders

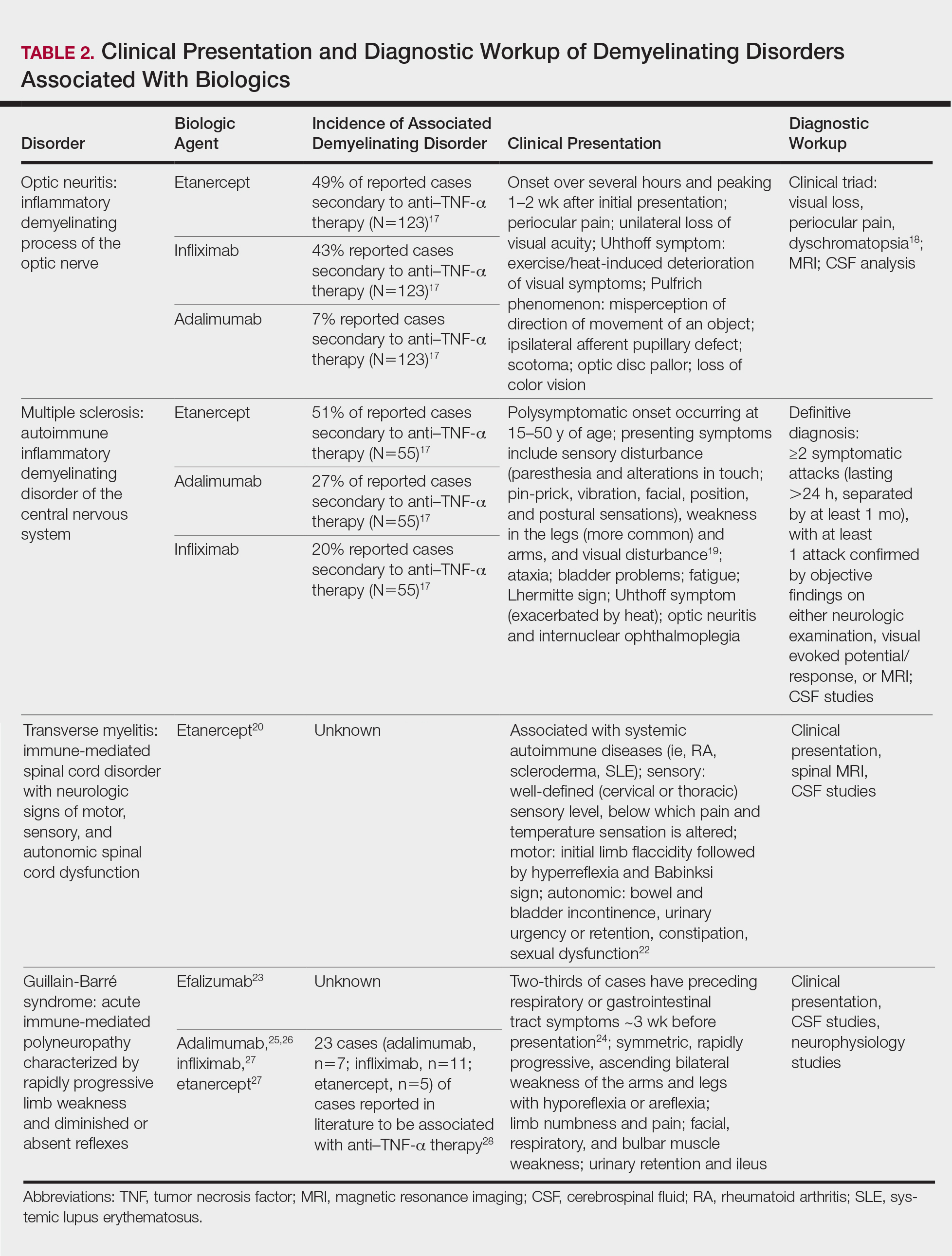

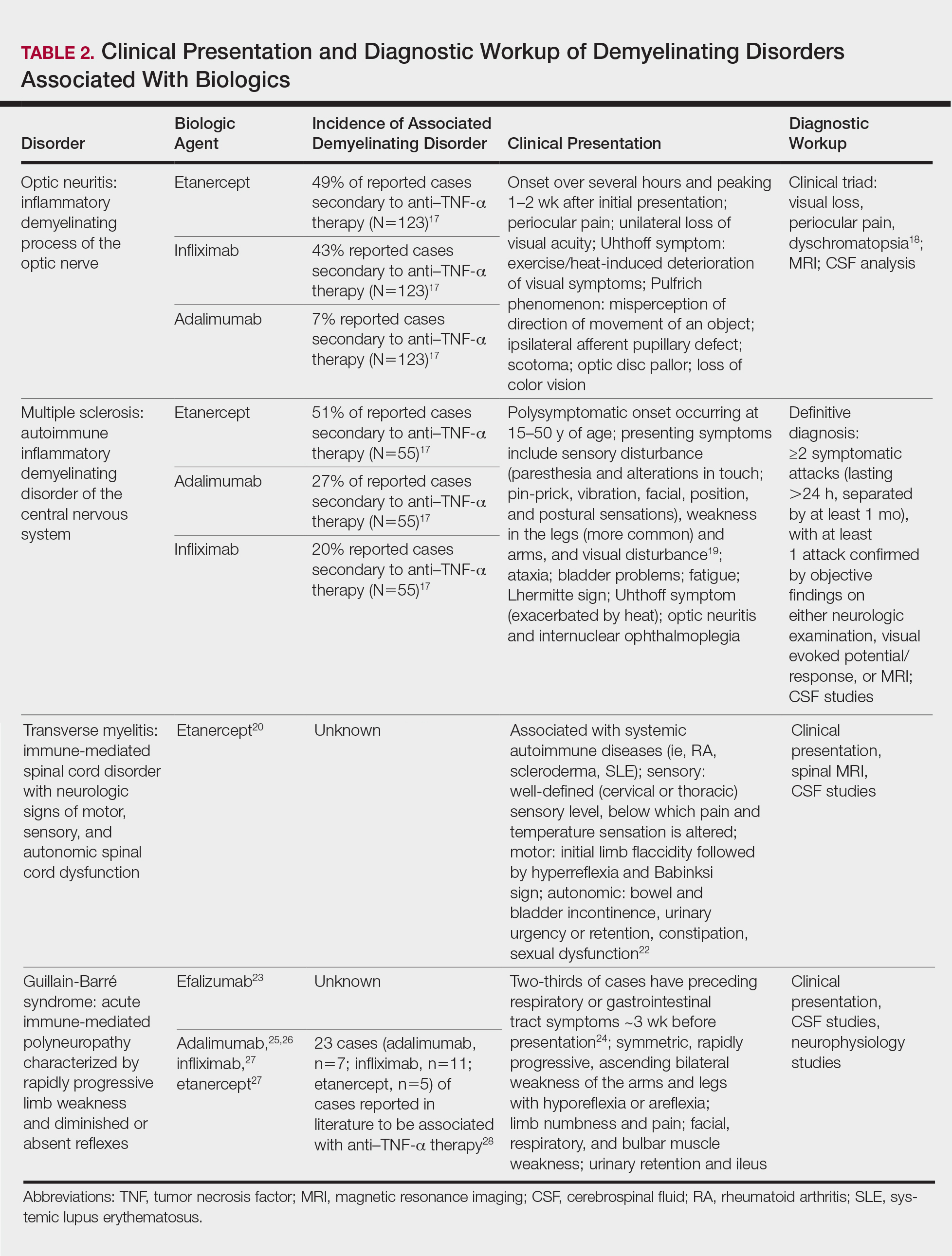

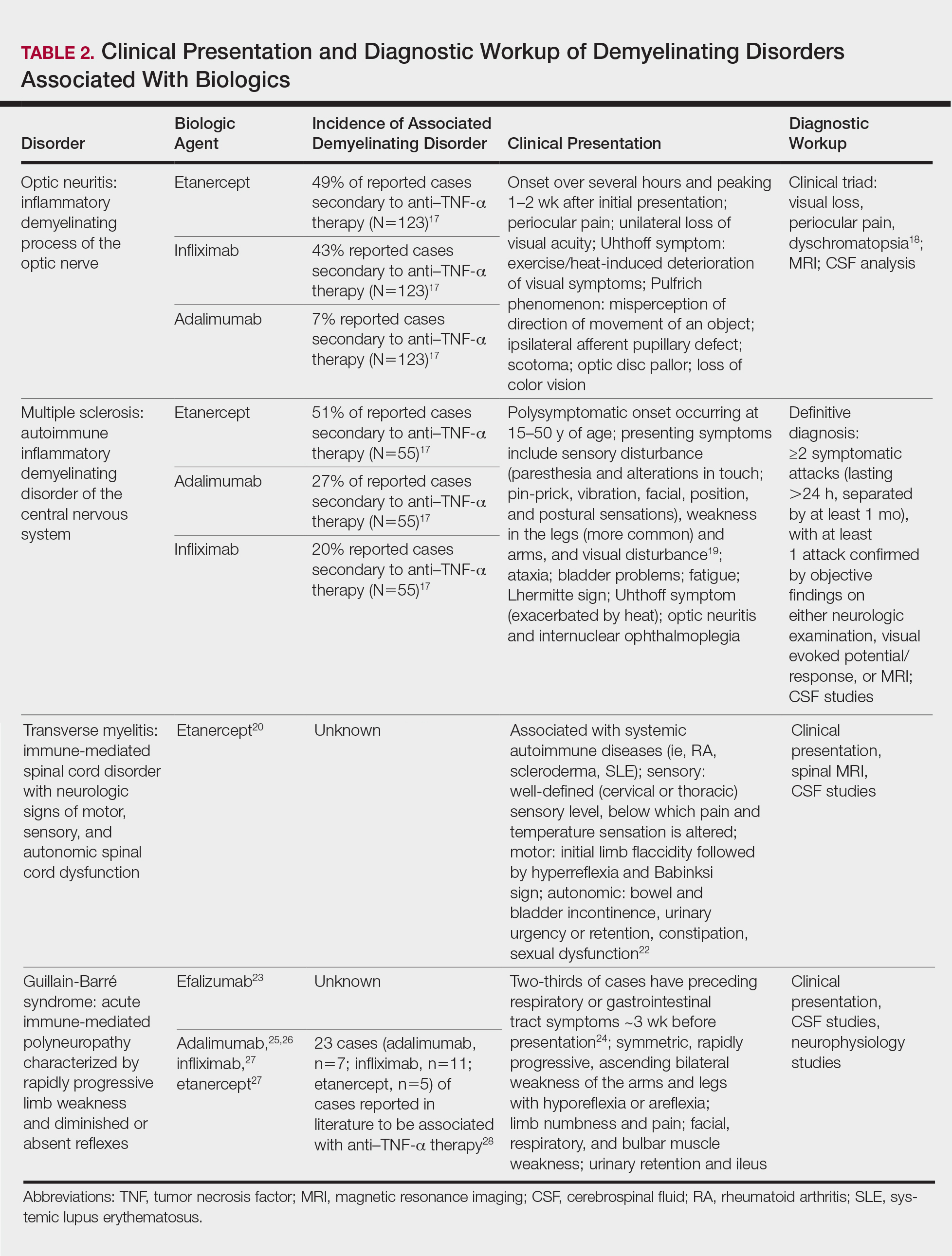

Clinical presentation of demyelinating events associated with biologic agents are varied but include optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, among others.17-28 These demyelinating disorders with their salient features and associated biologics are summarized in Table 2.17-20,22-28 Patients on biologic agents, especially TNF-α inhibitors, with new-onset visual, motor, or sensory changes warrant closer inspection. Currently, there are no data on any neurologic side effects occurring with the new biologic secukinumab.29

Conclusion

Biologic agents are effective in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but awareness of associated neurological adverse effects, though rare, is important to consider. Physicians need to be able to counsel patients concerning these risks and promote informed decision-making prior to initiating biologics. Patients with a personal or strong family history of demyelinating disease should be considered for alternative treatment options before initiating anti–TNF-α therapy. Since the withdrawal of efalizumab, no new cases of PML have been reported in patients who were previously on a long-term course. Dermatologists should be vigilant in detecting signs of neurological complications so that an expedited evaluation and neurology referral may prevent progression of disease.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- FDA Statement on the Voluntary Withdrawal of Raptiva From the U.S. Market. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrug-SafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm143347.htm. Published April 8, 2009. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:546-551.

- Tavazzi E, Ferrante P, Khalili K. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: an unexpected complication of modern therapeutic monoclonal antibody therapies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1776-1780.

- Korman BD, Tyler KL, Korman NJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, efalizumab, and immunosuppression: a cautionary tale for dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:937-942.

- Sudhakar P, Bachman DM, Mark AS, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: recent advances and a neuro-ophthalmological review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35:296-305.

- Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80:1430-1438.

- Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, et al. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52:253-260.

- Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1156-1164.

- Babi MA, Pendlebury W, Braff S, et al. JC virus PCR detection is not infallible: a fulminant case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with false-negative cerebrospinal fluid studies despite progressive clinical course and radiological findings [published online March 12, 2015]. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:643216.

- Ray M, Curtis JR, Baddley JW. A case report of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) associated with adalimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1429-1430.

- Kumar D, Bouldin TW, Berger RG. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3191-3195.

- Graff-Radford J, Robinson MT, Warsame RM, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with etanercept. Neurologist. 2012;18:85-87.

- Dickson L, Menter A. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS) in a psoriasis patient treated with ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:177-179.

- Gratton D, Szapary P, Goyal K, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in a patient treated with ustekinumab: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1197-1202.

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500.

- Ramos-Casals M, Roberto-Perez A, Diaz-Lagares C, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by biological agents: a double-edged sword? Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:188-193.

- Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:65-72.

- Richards RG, Sampson FC, Beard SM, et al. A review of the natural history and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: implications for resource allocation and health economic models. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1-73.

- Caracseghi F, Izquierdo-Blasco J, Sanchez-Montanez A, et al. Etanercept-induced myelopathy in a pediatric case of blau syndrome [published online January 15, 2012]. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2011;2011:134106.

- Fromont A, De Seze J, Fleury MC, et al. Inflammatory demyelinating events following treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor. Cytokine. 2009;45:55-57.

- Sellner J, Lüthi N, Schüpbach WM, et al. Diagnostic workup of patients with acute transverse myelitis: spectrum of clinical presentation, neuroimaging and laboratory findings. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:312-317.

- Turatti M, Tamburin S, Idone D, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after short-course efalizumab treatment. J Neurol. 2010;257:1404-1405.

- Koga M, Yuki N, Hirata K. Antecedent symptoms in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an important indicator for clinical and serological subgroups. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:278-287.

- Cesarini M, Angelucci E, Foglietta T, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after treatment with human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (adalimumab) in a Crohn’s disease patient: case report and literature review [published online July 28, 2011]. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:619-622.

- Soto-Cabrera E, Hernández-Martínez A, Yañez H, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Its association with alpha tumor necrosis factor [in Spanish]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2012;50:565-567.

- Shin IS, Baer AN, Kwon HJ, et al. Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes occurring with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1429-1434.

- Alvarez-Lario B, Prieto-Tejedo R, Colazo-Burlato M, et al. Severe Guillain-Barré syndrome in a patient receiving anti-TNF therapy. consequence or coincidence. a case-based review. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1407-1412.

- Garnock-Jones KP. Secukinumab: a review in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:323-330.

Biologic agents have provided patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with treatment alternatives that have improved systemic safety profiles and disease control1; however, case reports of associated neurologic complications have been emerging. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors have been associated with central and peripheral demyelinating disorders. Notably, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market for its association with fatal cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).2,3 It is imperative for dermatologists to be familiar with the clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnostic criteria of neurologic complications of biologic agents used in the treatment of psoriasis.

Leukoencephalopathy

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a fatal demyelinating neurodegenerative disease caused by reactivation of the ubiquitous John Cunningham virus. Primary asymptomatic infection is thought to occur during childhood, then the virus remains latent. Reactivation usually occurs during severe immunosuppression and is classically described in human immunodeficiency virus infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and other forms of cancer.4 A summary of PML and its association with biologics is found in Table 1.5-13 Few case reports of TNF-α inhibitor–associated PML exist, mostly in the presence of confounding factors such as immunosuppression or underlying autoimmune disease.10-13 Presenting symptoms of PML often are subacute, rapidly progressive, and can be focal or multifocal and include motor, cognitive, and visual deficits. Of note, there are 2 reported cases of ustekinumab associated with reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, which is a hypertensive encephalopathy characterized by headache, altered mental status, vision abnormalities, and seizures.14,15 Fortunately, this disease is reversible with blood pressure control and removal of the immunosuppressive agent.16

Demyelinating Disorders

Clinical presentation of demyelinating events associated with biologic agents are varied but include optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, among others.17-28 These demyelinating disorders with their salient features and associated biologics are summarized in Table 2.17-20,22-28 Patients on biologic agents, especially TNF-α inhibitors, with new-onset visual, motor, or sensory changes warrant closer inspection. Currently, there are no data on any neurologic side effects occurring with the new biologic secukinumab.29

Conclusion

Biologic agents are effective in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but awareness of associated neurological adverse effects, though rare, is important to consider. Physicians need to be able to counsel patients concerning these risks and promote informed decision-making prior to initiating biologics. Patients with a personal or strong family history of demyelinating disease should be considered for alternative treatment options before initiating anti–TNF-α therapy. Since the withdrawal of efalizumab, no new cases of PML have been reported in patients who were previously on a long-term course. Dermatologists should be vigilant in detecting signs of neurological complications so that an expedited evaluation and neurology referral may prevent progression of disease.

Biologic agents have provided patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with treatment alternatives that have improved systemic safety profiles and disease control1; however, case reports of associated neurologic complications have been emerging. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors have been associated with central and peripheral demyelinating disorders. Notably, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market for its association with fatal cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).2,3 It is imperative for dermatologists to be familiar with the clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnostic criteria of neurologic complications of biologic agents used in the treatment of psoriasis.

Leukoencephalopathy

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a fatal demyelinating neurodegenerative disease caused by reactivation of the ubiquitous John Cunningham virus. Primary asymptomatic infection is thought to occur during childhood, then the virus remains latent. Reactivation usually occurs during severe immunosuppression and is classically described in human immunodeficiency virus infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and other forms of cancer.4 A summary of PML and its association with biologics is found in Table 1.5-13 Few case reports of TNF-α inhibitor–associated PML exist, mostly in the presence of confounding factors such as immunosuppression or underlying autoimmune disease.10-13 Presenting symptoms of PML often are subacute, rapidly progressive, and can be focal or multifocal and include motor, cognitive, and visual deficits. Of note, there are 2 reported cases of ustekinumab associated with reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, which is a hypertensive encephalopathy characterized by headache, altered mental status, vision abnormalities, and seizures.14,15 Fortunately, this disease is reversible with blood pressure control and removal of the immunosuppressive agent.16

Demyelinating Disorders

Clinical presentation of demyelinating events associated with biologic agents are varied but include optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, among others.17-28 These demyelinating disorders with their salient features and associated biologics are summarized in Table 2.17-20,22-28 Patients on biologic agents, especially TNF-α inhibitors, with new-onset visual, motor, or sensory changes warrant closer inspection. Currently, there are no data on any neurologic side effects occurring with the new biologic secukinumab.29

Conclusion

Biologic agents are effective in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but awareness of associated neurological adverse effects, though rare, is important to consider. Physicians need to be able to counsel patients concerning these risks and promote informed decision-making prior to initiating biologics. Patients with a personal or strong family history of demyelinating disease should be considered for alternative treatment options before initiating anti–TNF-α therapy. Since the withdrawal of efalizumab, no new cases of PML have been reported in patients who were previously on a long-term course. Dermatologists should be vigilant in detecting signs of neurological complications so that an expedited evaluation and neurology referral may prevent progression of disease.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- FDA Statement on the Voluntary Withdrawal of Raptiva From the U.S. Market. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrug-SafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm143347.htm. Published April 8, 2009. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:546-551.

- Tavazzi E, Ferrante P, Khalili K. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: an unexpected complication of modern therapeutic monoclonal antibody therapies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1776-1780.

- Korman BD, Tyler KL, Korman NJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, efalizumab, and immunosuppression: a cautionary tale for dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:937-942.

- Sudhakar P, Bachman DM, Mark AS, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: recent advances and a neuro-ophthalmological review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35:296-305.

- Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80:1430-1438.

- Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, et al. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52:253-260.

- Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1156-1164.

- Babi MA, Pendlebury W, Braff S, et al. JC virus PCR detection is not infallible: a fulminant case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with false-negative cerebrospinal fluid studies despite progressive clinical course and radiological findings [published online March 12, 2015]. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:643216.

- Ray M, Curtis JR, Baddley JW. A case report of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) associated with adalimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1429-1430.

- Kumar D, Bouldin TW, Berger RG. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3191-3195.

- Graff-Radford J, Robinson MT, Warsame RM, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with etanercept. Neurologist. 2012;18:85-87.

- Dickson L, Menter A. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS) in a psoriasis patient treated with ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:177-179.

- Gratton D, Szapary P, Goyal K, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in a patient treated with ustekinumab: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1197-1202.

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500.

- Ramos-Casals M, Roberto-Perez A, Diaz-Lagares C, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by biological agents: a double-edged sword? Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:188-193.

- Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:65-72.

- Richards RG, Sampson FC, Beard SM, et al. A review of the natural history and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: implications for resource allocation and health economic models. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1-73.

- Caracseghi F, Izquierdo-Blasco J, Sanchez-Montanez A, et al. Etanercept-induced myelopathy in a pediatric case of blau syndrome [published online January 15, 2012]. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2011;2011:134106.

- Fromont A, De Seze J, Fleury MC, et al. Inflammatory demyelinating events following treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor. Cytokine. 2009;45:55-57.

- Sellner J, Lüthi N, Schüpbach WM, et al. Diagnostic workup of patients with acute transverse myelitis: spectrum of clinical presentation, neuroimaging and laboratory findings. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:312-317.

- Turatti M, Tamburin S, Idone D, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after short-course efalizumab treatment. J Neurol. 2010;257:1404-1405.

- Koga M, Yuki N, Hirata K. Antecedent symptoms in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an important indicator for clinical and serological subgroups. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:278-287.

- Cesarini M, Angelucci E, Foglietta T, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after treatment with human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (adalimumab) in a Crohn’s disease patient: case report and literature review [published online July 28, 2011]. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:619-622.

- Soto-Cabrera E, Hernández-Martínez A, Yañez H, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Its association with alpha tumor necrosis factor [in Spanish]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2012;50:565-567.

- Shin IS, Baer AN, Kwon HJ, et al. Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes occurring with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1429-1434.

- Alvarez-Lario B, Prieto-Tejedo R, Colazo-Burlato M, et al. Severe Guillain-Barré syndrome in a patient receiving anti-TNF therapy. consequence or coincidence. a case-based review. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1407-1412.

- Garnock-Jones KP. Secukinumab: a review in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:323-330.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- FDA Statement on the Voluntary Withdrawal of Raptiva From the U.S. Market. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrug-SafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm143347.htm. Published April 8, 2009. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:546-551.

- Tavazzi E, Ferrante P, Khalili K. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: an unexpected complication of modern therapeutic monoclonal antibody therapies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1776-1780.

- Korman BD, Tyler KL, Korman NJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, efalizumab, and immunosuppression: a cautionary tale for dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:937-942.

- Sudhakar P, Bachman DM, Mark AS, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: recent advances and a neuro-ophthalmological review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35:296-305.

- Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80:1430-1438.

- Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, et al. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52:253-260.

- Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1156-1164.

- Babi MA, Pendlebury W, Braff S, et al. JC virus PCR detection is not infallible: a fulminant case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with false-negative cerebrospinal fluid studies despite progressive clinical course and radiological findings [published online March 12, 2015]. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:643216.

- Ray M, Curtis JR, Baddley JW. A case report of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) associated with adalimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1429-1430.

- Kumar D, Bouldin TW, Berger RG. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3191-3195.

- Graff-Radford J, Robinson MT, Warsame RM, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with etanercept. Neurologist. 2012;18:85-87.

- Dickson L, Menter A. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS) in a psoriasis patient treated with ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:177-179.

- Gratton D, Szapary P, Goyal K, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in a patient treated with ustekinumab: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1197-1202.

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500.

- Ramos-Casals M, Roberto-Perez A, Diaz-Lagares C, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by biological agents: a double-edged sword? Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:188-193.

- Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:65-72.

- Richards RG, Sampson FC, Beard SM, et al. A review of the natural history and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: implications for resource allocation and health economic models. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1-73.

- Caracseghi F, Izquierdo-Blasco J, Sanchez-Montanez A, et al. Etanercept-induced myelopathy in a pediatric case of blau syndrome [published online January 15, 2012]. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2011;2011:134106.

- Fromont A, De Seze J, Fleury MC, et al. Inflammatory demyelinating events following treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor. Cytokine. 2009;45:55-57.

- Sellner J, Lüthi N, Schüpbach WM, et al. Diagnostic workup of patients with acute transverse myelitis: spectrum of clinical presentation, neuroimaging and laboratory findings. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:312-317.

- Turatti M, Tamburin S, Idone D, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after short-course efalizumab treatment. J Neurol. 2010;257:1404-1405.

- Koga M, Yuki N, Hirata K. Antecedent symptoms in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an important indicator for clinical and serological subgroups. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:278-287.

- Cesarini M, Angelucci E, Foglietta T, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after treatment with human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (adalimumab) in a Crohn’s disease patient: case report and literature review [published online July 28, 2011]. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:619-622.

- Soto-Cabrera E, Hernández-Martínez A, Yañez H, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Its association with alpha tumor necrosis factor [in Spanish]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2012;50:565-567.

- Shin IS, Baer AN, Kwon HJ, et al. Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes occurring with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1429-1434.

- Alvarez-Lario B, Prieto-Tejedo R, Colazo-Burlato M, et al. Severe Guillain-Barré syndrome in a patient receiving anti-TNF therapy. consequence or coincidence. a case-based review. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1407-1412.

- Garnock-Jones KP. Secukinumab: a review in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:323-330.

Practice Points

- Patients with a personal or strong family history of demyelinating disease should be considered for alternative treatment options before initiating anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α therapy.

- Patients on biologic agents, especially TNF-α inhibitors, with subacute or rapidly progressive visual, motor, or sensory changes or a single neurologic deficit may warrant referral to neurology and/or neuroimaging.

Minorities less likely to seek treatment for psoriasis

Black, Asian, and other non-Hispanic Americans are less likely than are whites to seek treatment for psoriasis, according to data on 842 patients, reported Alexander H. Fischer, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his colleagues.

Data from previous studies have shown that racial and ethnic minorities have more severe psoriasis and a lower quality of life as a result of the disease, compared with white patients, the researchers noted in a study published as a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

A total of 51% of non-Hispanic whites with psoriasis sought treatment from a dermatologist, compared with 47% of Hispanic whites and 38% of non-Hispanic minorities (blacks, Asians, native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and others). In addition, non-Hispanic minorities had significantly fewer ambulatory visits for psoriasis per year than did whites (a mean of 1.30 visits vs. 2.69 visits). Black, Asian, and other non-Hispanic minorities were about 40% less likely than were non-Hispanic whites to seek care for psoriasis.

The number of psoriasis prescriptions obtained was not significantly different among the racial/ethnic groups, the researchers reported.

The study is important because of the lack of data on psoriasis in nonwhite populations, senior author Junko Takeshita, MD, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania, said in an interview.

“Based on a few existing studies, we know that psoriasis is less common among minorities, but minorities, particularly blacks, may have more severe disease,” she said. “Also, minorities report poorer quality of life due to psoriasis than whites, independent of psoriasis severity. Furthermore, we previously published a study among Medicare beneficiaries with psoriasis that revealed that blacks are about 70% less likely to receive biologic therapies than whites, independent of socioeconomic status and access to medical care,” she added.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that while psoriasis is less common among minorities than whites, minorities may suffer from a larger burden of disease, yet have fewer visits and are less likely to see a dermatologist for their psoriasis,” Dr. Takeshita said. “This disparity in health care utilization for psoriasis does not seem to be entirely explained by racial/ethnic differences in socioeconomic status and health insurance. It is yet unknown why this disparity exists, and I’m not sure that minority patients being ‘hesitant to pursue care’ is the entire answer, though it may be a contributing factor,” she noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the relatively small sample size and the use of self-reports.

Many factors could be contributing to the disparity, including patient, physician/other health care provider, and health care system factors, but “once we identify the major causes of the disparity, we can develop methods to address the causes and reduce the disparity,” said Dr. Takeshita, who is a dermatologist and an epidemiologist. In the meantime, she added, “some things I think that are important to ensure equitable care for psoriasis are making sure that clinicians/dermatologists are comfortable diagnosing and treating psoriasis in nonwhite individuals, and encouraging clinicians to help increase awareness of psoriasis by educating their minority patients that psoriasis is still a common skin disease among nonwhite individuals.”

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Takeshita has received a research grant from Pfizer; she and another author, Joel Gelfand, MD, have received payment for psoriasis-related continuing medical education work supported indirectly by Eli Lilly; Dr. Gelfand’s other disclosures included serving as a consultant for, and having received research grants from, several other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Fischer, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, at the time of the research, and a fourth author had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fischer AH et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78[1]:200-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.052.

Black, Asian, and other non-Hispanic Americans are less likely than are whites to seek treatment for psoriasis, according to data on 842 patients, reported Alexander H. Fischer, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his colleagues.

Data from previous studies have shown that racial and ethnic minorities have more severe psoriasis and a lower quality of life as a result of the disease, compared with white patients, the researchers noted in a study published as a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

A total of 51% of non-Hispanic whites with psoriasis sought treatment from a dermatologist, compared with 47% of Hispanic whites and 38% of non-Hispanic minorities (blacks, Asians, native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and others). In addition, non-Hispanic minorities had significantly fewer ambulatory visits for psoriasis per year than did whites (a mean of 1.30 visits vs. 2.69 visits). Black, Asian, and other non-Hispanic minorities were about 40% less likely than were non-Hispanic whites to seek care for psoriasis.

The number of psoriasis prescriptions obtained was not significantly different among the racial/ethnic groups, the researchers reported.

The study is important because of the lack of data on psoriasis in nonwhite populations, senior author Junko Takeshita, MD, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania, said in an interview.

“Based on a few existing studies, we know that psoriasis is less common among minorities, but minorities, particularly blacks, may have more severe disease,” she said. “Also, minorities report poorer quality of life due to psoriasis than whites, independent of psoriasis severity. Furthermore, we previously published a study among Medicare beneficiaries with psoriasis that revealed that blacks are about 70% less likely to receive biologic therapies than whites, independent of socioeconomic status and access to medical care,” she added.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that while psoriasis is less common among minorities than whites, minorities may suffer from a larger burden of disease, yet have fewer visits and are less likely to see a dermatologist for their psoriasis,” Dr. Takeshita said. “This disparity in health care utilization for psoriasis does not seem to be entirely explained by racial/ethnic differences in socioeconomic status and health insurance. It is yet unknown why this disparity exists, and I’m not sure that minority patients being ‘hesitant to pursue care’ is the entire answer, though it may be a contributing factor,” she noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the relatively small sample size and the use of self-reports.

Many factors could be contributing to the disparity, including patient, physician/other health care provider, and health care system factors, but “once we identify the major causes of the disparity, we can develop methods to address the causes and reduce the disparity,” said Dr. Takeshita, who is a dermatologist and an epidemiologist. In the meantime, she added, “some things I think that are important to ensure equitable care for psoriasis are making sure that clinicians/dermatologists are comfortable diagnosing and treating psoriasis in nonwhite individuals, and encouraging clinicians to help increase awareness of psoriasis by educating their minority patients that psoriasis is still a common skin disease among nonwhite individuals.”

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Takeshita has received a research grant from Pfizer; she and another author, Joel Gelfand, MD, have received payment for psoriasis-related continuing medical education work supported indirectly by Eli Lilly; Dr. Gelfand’s other disclosures included serving as a consultant for, and having received research grants from, several other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Fischer, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, at the time of the research, and a fourth author had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fischer AH et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78[1]:200-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.052.

Black, Asian, and other non-Hispanic Americans are less likely than are whites to seek treatment for psoriasis, according to data on 842 patients, reported Alexander H. Fischer, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his colleagues.

Data from previous studies have shown that racial and ethnic minorities have more severe psoriasis and a lower quality of life as a result of the disease, compared with white patients, the researchers noted in a study published as a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

A total of 51% of non-Hispanic whites with psoriasis sought treatment from a dermatologist, compared with 47% of Hispanic whites and 38% of non-Hispanic minorities (blacks, Asians, native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and others). In addition, non-Hispanic minorities had significantly fewer ambulatory visits for psoriasis per year than did whites (a mean of 1.30 visits vs. 2.69 visits). Black, Asian, and other non-Hispanic minorities were about 40% less likely than were non-Hispanic whites to seek care for psoriasis.

The number of psoriasis prescriptions obtained was not significantly different among the racial/ethnic groups, the researchers reported.

The study is important because of the lack of data on psoriasis in nonwhite populations, senior author Junko Takeshita, MD, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania, said in an interview.

“Based on a few existing studies, we know that psoriasis is less common among minorities, but minorities, particularly blacks, may have more severe disease,” she said. “Also, minorities report poorer quality of life due to psoriasis than whites, independent of psoriasis severity. Furthermore, we previously published a study among Medicare beneficiaries with psoriasis that revealed that blacks are about 70% less likely to receive biologic therapies than whites, independent of socioeconomic status and access to medical care,” she added.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that while psoriasis is less common among minorities than whites, minorities may suffer from a larger burden of disease, yet have fewer visits and are less likely to see a dermatologist for their psoriasis,” Dr. Takeshita said. “This disparity in health care utilization for psoriasis does not seem to be entirely explained by racial/ethnic differences in socioeconomic status and health insurance. It is yet unknown why this disparity exists, and I’m not sure that minority patients being ‘hesitant to pursue care’ is the entire answer, though it may be a contributing factor,” she noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the relatively small sample size and the use of self-reports.

Many factors could be contributing to the disparity, including patient, physician/other health care provider, and health care system factors, but “once we identify the major causes of the disparity, we can develop methods to address the causes and reduce the disparity,” said Dr. Takeshita, who is a dermatologist and an epidemiologist. In the meantime, she added, “some things I think that are important to ensure equitable care for psoriasis are making sure that clinicians/dermatologists are comfortable diagnosing and treating psoriasis in nonwhite individuals, and encouraging clinicians to help increase awareness of psoriasis by educating their minority patients that psoriasis is still a common skin disease among nonwhite individuals.”

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Takeshita has received a research grant from Pfizer; she and another author, Joel Gelfand, MD, have received payment for psoriasis-related continuing medical education work supported indirectly by Eli Lilly; Dr. Gelfand’s other disclosures included serving as a consultant for, and having received research grants from, several other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Fischer, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, at the time of the research, and a fourth author had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fischer AH et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78[1]:200-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.052.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Black, Asian, and non-Hispanic patients with psoriasis often have more severe disease than do white patients but are significantly less likely to seek care.

Major finding:

Data source: A cohort study of data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey on 842 psoriasis patients in the United States.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Two of the four authors had no financial disclosures. One author has received a research grant from Pfizer and payment for psoriasis-related continuing medical education work supported indirectly by Eli Lilly; another author’s disclosures included the latter, as well serving as a consultant for, and having received research grants from, several other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Fischer AH et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78[1]:200-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.05

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: How to Help Patients Who Are Afraid of Injections

Myth: Patients Are Not Willing to Give Themselves Injections

Injectable biologics target specific parts of the immune system, making them popular treatment options for psoriasis patients, with ample research on their efficacy. Performing a self-injection can be daunting for patients trying a biologic for the first time, and clinicians should be aware of the dearth of patient education material. Although patients may be fearful of self-injections, especially the first few treatments, their worries can be assuaged with proper instruction and appropriate delivery method.

Abrouk et al sought to provide an online guide and video on biologic injections to increase the success of the therapy and compliance among patients. They created a printable guide that covers the supplies needed, procedure techniques, and plans for traveling with medications. Because pain is a common concern for patients, they suggest numbing the injection area with an ice pack first. They also offer tips on dealing with injection-site reactions such as redness or bruising.

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants can be used to give psoriasis patients more personalized attention regarding the fear of injections. They can explain the injection procedures and describe differences between administration techniques. Some patients may prefer using an autoinjector versus a prefilled syringe, which may impact the treatment administered. Taking photographs to show progress with therapy also may motivate patients to tolerate therapy.

The National Psoriasis Foundation provides the following tips to make it easier for patients to self-inject and reduce the chance of an injection-site reaction:

- Pick an easy injection site, such as the top of the rights, abdomen, or back of the arms.

- Rotate injection sites from right to left.

- Numb the area.

- Warm the pen up by taking it out of the refrigerator 1.5 hours before it is used.

- Be patient and avoid moving the injection pen before the needle is finished administering the drug.

By giving psoriasis patients educational materials, you can empower them to control their disease with injectable biologics.

Expert Commentary

Most of my patients who use a biologic for the first time are undaunted by learning to inject themselves. I can think of just 1 of my ~300 biologic patients who has to come in every few weeks for their medicine to be injected by one of our nurses. Surprisingly, some patients (I'd estimate 5% of my biologic patients) actually prefer the syringe compared to the autoinjector, with some comments saying that the syringe is less painful and less abrupt. Needle phobia should not be a reason to not prescribe a biologic for a patient with severe psoriasis who needs it.

Abrouk M, Nakamura M, Zhu TH, et al. The patient’s guide to psoriasis treatment. part 3: biologic injectables. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:325-331.

Aldredge LM, Young MS. Providing guidance for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who are candidates for biologic therapy. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2016;8:14-26.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Self-injections 101. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/biologics/self-injections-101. Accessed January 2, 2018.

Myth: Patients Are Not Willing to Give Themselves Injections

Injectable biologics target specific parts of the immune system, making them popular treatment options for psoriasis patients, with ample research on their efficacy. Performing a self-injection can be daunting for patients trying a biologic for the first time, and clinicians should be aware of the dearth of patient education material. Although patients may be fearful of self-injections, especially the first few treatments, their worries can be assuaged with proper instruction and appropriate delivery method.

Abrouk et al sought to provide an online guide and video on biologic injections to increase the success of the therapy and compliance among patients. They created a printable guide that covers the supplies needed, procedure techniques, and plans for traveling with medications. Because pain is a common concern for patients, they suggest numbing the injection area with an ice pack first. They also offer tips on dealing with injection-site reactions such as redness or bruising.

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants can be used to give psoriasis patients more personalized attention regarding the fear of injections. They can explain the injection procedures and describe differences between administration techniques. Some patients may prefer using an autoinjector versus a prefilled syringe, which may impact the treatment administered. Taking photographs to show progress with therapy also may motivate patients to tolerate therapy.

The National Psoriasis Foundation provides the following tips to make it easier for patients to self-inject and reduce the chance of an injection-site reaction:

- Pick an easy injection site, such as the top of the rights, abdomen, or back of the arms.

- Rotate injection sites from right to left.

- Numb the area.

- Warm the pen up by taking it out of the refrigerator 1.5 hours before it is used.

- Be patient and avoid moving the injection pen before the needle is finished administering the drug.

By giving psoriasis patients educational materials, you can empower them to control their disease with injectable biologics.

Expert Commentary

Most of my patients who use a biologic for the first time are undaunted by learning to inject themselves. I can think of just 1 of my ~300 biologic patients who has to come in every few weeks for their medicine to be injected by one of our nurses. Surprisingly, some patients (I'd estimate 5% of my biologic patients) actually prefer the syringe compared to the autoinjector, with some comments saying that the syringe is less painful and less abrupt. Needle phobia should not be a reason to not prescribe a biologic for a patient with severe psoriasis who needs it.

Myth: Patients Are Not Willing to Give Themselves Injections

Injectable biologics target specific parts of the immune system, making them popular treatment options for psoriasis patients, with ample research on their efficacy. Performing a self-injection can be daunting for patients trying a biologic for the first time, and clinicians should be aware of the dearth of patient education material. Although patients may be fearful of self-injections, especially the first few treatments, their worries can be assuaged with proper instruction and appropriate delivery method.

Abrouk et al sought to provide an online guide and video on biologic injections to increase the success of the therapy and compliance among patients. They created a printable guide that covers the supplies needed, procedure techniques, and plans for traveling with medications. Because pain is a common concern for patients, they suggest numbing the injection area with an ice pack first. They also offer tips on dealing with injection-site reactions such as redness or bruising.

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants can be used to give psoriasis patients more personalized attention regarding the fear of injections. They can explain the injection procedures and describe differences between administration techniques. Some patients may prefer using an autoinjector versus a prefilled syringe, which may impact the treatment administered. Taking photographs to show progress with therapy also may motivate patients to tolerate therapy.

The National Psoriasis Foundation provides the following tips to make it easier for patients to self-inject and reduce the chance of an injection-site reaction:

- Pick an easy injection site, such as the top of the rights, abdomen, or back of the arms.

- Rotate injection sites from right to left.

- Numb the area.

- Warm the pen up by taking it out of the refrigerator 1.5 hours before it is used.

- Be patient and avoid moving the injection pen before the needle is finished administering the drug.

By giving psoriasis patients educational materials, you can empower them to control their disease with injectable biologics.

Expert Commentary

Most of my patients who use a biologic for the first time are undaunted by learning to inject themselves. I can think of just 1 of my ~300 biologic patients who has to come in every few weeks for their medicine to be injected by one of our nurses. Surprisingly, some patients (I'd estimate 5% of my biologic patients) actually prefer the syringe compared to the autoinjector, with some comments saying that the syringe is less painful and less abrupt. Needle phobia should not be a reason to not prescribe a biologic for a patient with severe psoriasis who needs it.

Abrouk M, Nakamura M, Zhu TH, et al. The patient’s guide to psoriasis treatment. part 3: biologic injectables. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:325-331.

Aldredge LM, Young MS. Providing guidance for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who are candidates for biologic therapy. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2016;8:14-26.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Self-injections 101. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/biologics/self-injections-101. Accessed January 2, 2018.

Abrouk M, Nakamura M, Zhu TH, et al. The patient’s guide to psoriasis treatment. part 3: biologic injectables. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:325-331.

Aldredge LM, Young MS. Providing guidance for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who are candidates for biologic therapy. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2016;8:14-26.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Self-injections 101. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/biologics/self-injections-101. Accessed January 2, 2018.

Guselkumab crushes skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients

GENEVA – The interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab generates the same impressive improvement in skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients as has been seen in psoriasis without joint disease, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

However, psoriatic arthritis patients’ improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores is less robust than in patients with psoriasis only, added Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

The psoriatic arthritis group as a whole had more severe psoriasis, with a baseline mean PASI score of 24.3 and involvement of 32.7% of their body surface area as compared with a PASI score of 21.2 and 27.2% BSA in psoriasis patients without arthritis. A total of 28% of the psoriatic arthritis patients had previously been on other biologics and 77% had been on nonbiologic systemic agents, compared with 19% and 60% of the psoriasis patients, respectively. The psoriatic arthritis group had a mean 19.2-year history of psoriasis, 1.9 years longer than the psoriasis-only group.

Participants were randomized to 100 mg of guselkumab administered subcutaneously at weeks 0, 4, 12, and 20; placebo through week 12, followed by a switch to adalimumab (Humira); or adalimumab at 80 mg at week 0, then 40 mg at week 2 and 40 mg again every 2 weeks until week 23.

The key findings:

The PASI 90 response rate – that is, at least a 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index – in guselkumab-treated patients at week 16 was 72% in patients with psoriatic arthritis and 71% in those without. At week 24, the PASI 90 rate was 74% in guselkumab-treated patients with psoriatic arthritis and similar at 78% in those without. In contrast, the PASI 90 rate at week 24 in patients on adalimumab was significantly lower: 48% in the psoriatic arthritis group and 55% in those with psoriasis only. The PASI 90 rate in placebo-treated controls was single digit.

At week 24, 82% of psoriatic arthritis patients on guselkumab had clear or almost clear skin as reflected in an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, as did 84% of psoriasis-only patients.

A DLQI score of 0 or 1, meaning the dermatologic disease had no impact on patient quality of life, was documented at week 16 in 46% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 55% of psoriasis-only patients, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. However, by week 24 the difference became significant, with a DLQI of 0 or 1 in 48% of the psoriatic arthritis patients, compared with 62% of psoriasis-only patients.

VOYAGE 1 and 2 were dermatologic studies that didn’t measure changes in joint symptom scores or other psoriatic arthritis outcomes. Guselkumab as a potential treatment for psoriatic arthritis is under investigation in other studies.

The VOYAGE trials and this analysis were sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

GENEVA – The interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab generates the same impressive improvement in skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients as has been seen in psoriasis without joint disease, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

However, psoriatic arthritis patients’ improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores is less robust than in patients with psoriasis only, added Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

The psoriatic arthritis group as a whole had more severe psoriasis, with a baseline mean PASI score of 24.3 and involvement of 32.7% of their body surface area as compared with a PASI score of 21.2 and 27.2% BSA in psoriasis patients without arthritis. A total of 28% of the psoriatic arthritis patients had previously been on other biologics and 77% had been on nonbiologic systemic agents, compared with 19% and 60% of the psoriasis patients, respectively. The psoriatic arthritis group had a mean 19.2-year history of psoriasis, 1.9 years longer than the psoriasis-only group.

Participants were randomized to 100 mg of guselkumab administered subcutaneously at weeks 0, 4, 12, and 20; placebo through week 12, followed by a switch to adalimumab (Humira); or adalimumab at 80 mg at week 0, then 40 mg at week 2 and 40 mg again every 2 weeks until week 23.

The key findings:

The PASI 90 response rate – that is, at least a 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index – in guselkumab-treated patients at week 16 was 72% in patients with psoriatic arthritis and 71% in those without. At week 24, the PASI 90 rate was 74% in guselkumab-treated patients with psoriatic arthritis and similar at 78% in those without. In contrast, the PASI 90 rate at week 24 in patients on adalimumab was significantly lower: 48% in the psoriatic arthritis group and 55% in those with psoriasis only. The PASI 90 rate in placebo-treated controls was single digit.

At week 24, 82% of psoriatic arthritis patients on guselkumab had clear or almost clear skin as reflected in an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, as did 84% of psoriasis-only patients.

A DLQI score of 0 or 1, meaning the dermatologic disease had no impact on patient quality of life, was documented at week 16 in 46% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 55% of psoriasis-only patients, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. However, by week 24 the difference became significant, with a DLQI of 0 or 1 in 48% of the psoriatic arthritis patients, compared with 62% of psoriasis-only patients.

VOYAGE 1 and 2 were dermatologic studies that didn’t measure changes in joint symptom scores or other psoriatic arthritis outcomes. Guselkumab as a potential treatment for psoriatic arthritis is under investigation in other studies.

The VOYAGE trials and this analysis were sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

GENEVA – The interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab generates the same impressive improvement in skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients as has been seen in psoriasis without joint disease, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

However, psoriatic arthritis patients’ improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores is less robust than in patients with psoriasis only, added Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

The psoriatic arthritis group as a whole had more severe psoriasis, with a baseline mean PASI score of 24.3 and involvement of 32.7% of their body surface area as compared with a PASI score of 21.2 and 27.2% BSA in psoriasis patients without arthritis. A total of 28% of the psoriatic arthritis patients had previously been on other biologics and 77% had been on nonbiologic systemic agents, compared with 19% and 60% of the psoriasis patients, respectively. The psoriatic arthritis group had a mean 19.2-year history of psoriasis, 1.9 years longer than the psoriasis-only group.

Participants were randomized to 100 mg of guselkumab administered subcutaneously at weeks 0, 4, 12, and 20; placebo through week 12, followed by a switch to adalimumab (Humira); or adalimumab at 80 mg at week 0, then 40 mg at week 2 and 40 mg again every 2 weeks until week 23.

The key findings:

The PASI 90 response rate – that is, at least a 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index – in guselkumab-treated patients at week 16 was 72% in patients with psoriatic arthritis and 71% in those without. At week 24, the PASI 90 rate was 74% in guselkumab-treated patients with psoriatic arthritis and similar at 78% in those without. In contrast, the PASI 90 rate at week 24 in patients on adalimumab was significantly lower: 48% in the psoriatic arthritis group and 55% in those with psoriasis only. The PASI 90 rate in placebo-treated controls was single digit.

At week 24, 82% of psoriatic arthritis patients on guselkumab had clear or almost clear skin as reflected in an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, as did 84% of psoriasis-only patients.

A DLQI score of 0 or 1, meaning the dermatologic disease had no impact on patient quality of life, was documented at week 16 in 46% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 55% of psoriasis-only patients, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. However, by week 24 the difference became significant, with a DLQI of 0 or 1 in 48% of the psoriatic arthritis patients, compared with 62% of psoriasis-only patients.

VOYAGE 1 and 2 were dermatologic studies that didn’t measure changes in joint symptom scores or other psoriatic arthritis outcomes. Guselkumab as a potential treatment for psoriatic arthritis is under investigation in other studies.

The VOYAGE trials and this analysis were sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After 16 weeks on guselkumab, 72% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 71% with psoriasis-only had a PASI 90 response.

Study details: This was a comparison of skin and DLQI outcomes in 335 patients with psoriatic arthritis and 1,494 with psoriasis only who participated in two randomized, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trials.

Disclosures: Janssen sponsored the study. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/.

FDA approves infliximab biosimilar Ixifi for all of Remicade’s indications

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Ixifi (infliximab-qbtx), a biosimilar of Remicade, the original infliximab product. Ixifi is the third infliximab biosimilar to be approved by the FDA, and it is approved for all the same indications as Remicade, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, Pfizer.

Ixifi and Remicade are approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in combination with methotrexate, Crohn’s disease, pediatric Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis.

The most common adverse events associated with Ixifi are upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, pharyngitis, infusion-related reactions, headache, and abdominal pain.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Ixifi (infliximab-qbtx), a biosimilar of Remicade, the original infliximab product. Ixifi is the third infliximab biosimilar to be approved by the FDA, and it is approved for all the same indications as Remicade, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, Pfizer.

Ixifi and Remicade are approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in combination with methotrexate, Crohn’s disease, pediatric Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis.

The most common adverse events associated with Ixifi are upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, pharyngitis, infusion-related reactions, headache, and abdominal pain.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Ixifi (infliximab-qbtx), a biosimilar of Remicade, the original infliximab product. Ixifi is the third infliximab biosimilar to be approved by the FDA, and it is approved for all the same indications as Remicade, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, Pfizer.

Ixifi and Remicade are approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in combination with methotrexate, Crohn’s disease, pediatric Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis.

The most common adverse events associated with Ixifi are upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, pharyngitis, infusion-related reactions, headache, and abdominal pain.

Interleukin-23 inhibition for psoriasis shows ‘wow’ factor

GENEVA – The merits of addressing interleukin-23 as a novel therapeutic target in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were abundantly displayed in 2-year outcomes data for two anti–IL-23 monoclonal antibodies – guselkumab and tildrakizumab – in studies presented back to back at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

These long-term, open-label extensions of previously reported phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trials provided evidence of multiple advantages for IL-23 inhibition. The story was similar for both agents: After 2 years of use in the extension studies, the two biologics demonstrated stellar treatment response rates that would have been unimaginable only a few years ago, maintenance of efficacy without drop-off over time, exceedingly low dropout rates, and a safety picture that remains reassuring as experience accumulates. Also, the subcutaneously administered IL-23 inhibitors are attractive from a patient convenience standpoint in that maintenance guselkumab is dosed at 100 mg once every 8 weeks, and tildrakizumab is given once every 12 weeks.

Still, there are differences between the two drugs, most notably in apparent effectiveness. While more than half of guselkumab-treated patients had a Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) 100 response – that is, totally clear skin – at 2 years, that was the case for only one-quarter to one-third of patients on tildrakizumab.

Guselkumab (Tremfya) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in July 2017 for treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Tildrakizumab remains investigational.

Guselkumab

The 2-year, open-label extension of the phase 3 VOYAGE 1 trial included 735 patients who were either on guselkumab continuously, crossed from adalimumab (Humira) to guselkumab after 48 weeks, or switched from placebo after 16 weeks.

PASI 100 rates at 2 years were 49%-55% in the three patient groups. Of the patients in these groups, 54%-59% achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0. IGA scores of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear skin, were present in 82%-85% of patients at 2 years.

“Dropout rate is an important consideration in long-term studies,” observed Dr. Blauvelt, a dermatologist and president of Oregon Medical Research Center in Portland. “For patients on continuous guselkumab there was a 6% dropout rate in the first year and 6% in the second year, so 88% of patients that started guselkumab were still on guselkumab 2 years later. That’s impressive. In the other two groups, the dropout rate was 2% per year.”

A Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score of 0 or 1, meaning no disease effects on quality of life, was recorded in 62.5% of the continuous guselkumab group at 48 weeks and 71.1% at 2 years.

“The interesting thing here is that, even though the efficacy numbers are fairly constant between year 1 and year 2, the DLQI goes up and up. Surprising? Maybe not. I think it shows patients are getting happier and happier over time with their disease control,” Dr. Blauvelt continued.

Rates of serious adverse events remained low and stable, with no negative surprises during year 2. The serious infection rate was 1.02 cases/100 patient-years in year 1 and 0.84 cases/100 patient-years in year 2. No cases of tuberculosis, opportunistic infections, or serious hypersensitivity reactions occurred during 2 years of treatment.

Tildrakizumab

Two-year results from the ongoing 5-year extension of the phase 3 reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 trials were presented by Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, president of Probity Medical Research, Waterloo, Ont. This presentation of 2-year outcomes for 1,237 study participants was a feat, considering that the 12-week results of the trials had been published less than 3 months earlier (Lancet. 2017 Jul 15;390[10091]:276-88).

“I think these data are very compelling that the loss of response over time is minimal,” according to the dermatologist. “We’ve also seen that safety over 2 years has no surprises; in fact, it’s remarkably quiet. The rate of severe infections, which is important to look at for any treatment suppressing the immune system, is low and occurs almost independent of dose, which is very hopeful. It’s a promising sign.”

Indeed, the serious infection rate was 0.8 cases/100 patient-years regardless of whether subjects were on tildrakizumab at 100 mg or 200 mg.

Controversy over how to report long-term outcomes

A hot topic among clinical trialists in dermatology concerns how to report study results. The traditional method in studies funded by pharmaceutical companies is known as the “last observation carried forward” analysis. It casts the study drug results in the most favorable possible light because, when a subject drops out of a trial for any reason, their last measured value for response to treatment is carried forward as though the patient completed the study. Thus, psoriasis patients who drop out because they couldn’t tolerate a therapy or developed a serious side effect dictating discontinuation will be scored on the basis of their last PASI response, creating a bias in favor of active treatment.

A more conservative analytic method is known as the “nonresponder imputation” analysis. By this method, a patient who drops out of a trial is automatically categorized as a treatment failure, even if the reason was that the patient moved and could no longer make visits to the study center.

The prespecified guselkumab analysis presented by Dr. Blauvelt involved nonresponder imputation through year 1 and imputation based on the reason for discontinuation in the second year. In contrast, the 2-year tildrakizumab analysis presented by Dr. Papp used the far more common last observation carried forward method.

To help the audience appreciate the importance of looking at the analytic methods used in a studies and help them understand the clinical significance of the results, Dr. Blauvelt provided a reanalysis of the 2-year guselkumab data using the last observation carried forward method. Across the board, the numbers became more favorable. For example, the PASI 75 rate of 95.7% using the prespecified nonresponder imputation analysis crept up to 96.8% under the last observation carried forward method; for comparison, the PASI 75 rates were 81%-84% in the tildrakizumab analysis.

“If you wanted to compare apples to apples with some other drugs, you would use these numbers – the as-observed analysis numbers used by most other companies with other drugs. If you wanted to determine what the true-life numbers are, they’d probably be something between the nonresponder imputation and as-observed numbers,” said to Dr. Blauvelt.

Dr. Papp was untroubled by the use of the last observation carried forward method in the particular case of the tildrakizumab long-term extension study.

“There is reason to believe the as-observed analysis doesn’t affect the integrity of the data because the dropout rate is extraordinarily low,” he said.

The guselkumab analysis was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceutica; the tildrakizumab analysis was sponsored by Merck and by Sun Pharma. Dr. Blauvelt and Dr. Papp were paid investigators in both studies and serve as scientific advisers to virtually all companies invested in the psoriasis therapy developmental pipeline.

GENEVA – The merits of addressing interleukin-23 as a novel therapeutic target in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were abundantly displayed in 2-year outcomes data for two anti–IL-23 monoclonal antibodies – guselkumab and tildrakizumab – in studies presented back to back at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

These long-term, open-label extensions of previously reported phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trials provided evidence of multiple advantages for IL-23 inhibition. The story was similar for both agents: After 2 years of use in the extension studies, the two biologics demonstrated stellar treatment response rates that would have been unimaginable only a few years ago, maintenance of efficacy without drop-off over time, exceedingly low dropout rates, and a safety picture that remains reassuring as experience accumulates. Also, the subcutaneously administered IL-23 inhibitors are attractive from a patient convenience standpoint in that maintenance guselkumab is dosed at 100 mg once every 8 weeks, and tildrakizumab is given once every 12 weeks.

Still, there are differences between the two drugs, most notably in apparent effectiveness. While more than half of guselkumab-treated patients had a Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) 100 response – that is, totally clear skin – at 2 years, that was the case for only one-quarter to one-third of patients on tildrakizumab.

Guselkumab (Tremfya) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in July 2017 for treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Tildrakizumab remains investigational.

Guselkumab

The 2-year, open-label extension of the phase 3 VOYAGE 1 trial included 735 patients who were either on guselkumab continuously, crossed from adalimumab (Humira) to guselkumab after 48 weeks, or switched from placebo after 16 weeks.

PASI 100 rates at 2 years were 49%-55% in the three patient groups. Of the patients in these groups, 54%-59% achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0. IGA scores of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear skin, were present in 82%-85% of patients at 2 years.

“Dropout rate is an important consideration in long-term studies,” observed Dr. Blauvelt, a dermatologist and president of Oregon Medical Research Center in Portland. “For patients on continuous guselkumab there was a 6% dropout rate in the first year and 6% in the second year, so 88% of patients that started guselkumab were still on guselkumab 2 years later. That’s impressive. In the other two groups, the dropout rate was 2% per year.”

A Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score of 0 or 1, meaning no disease effects on quality of life, was recorded in 62.5% of the continuous guselkumab group at 48 weeks and 71.1% at 2 years.

“The interesting thing here is that, even though the efficacy numbers are fairly constant between year 1 and year 2, the DLQI goes up and up. Surprising? Maybe not. I think it shows patients are getting happier and happier over time with their disease control,” Dr. Blauvelt continued.

Rates of serious adverse events remained low and stable, with no negative surprises during year 2. The serious infection rate was 1.02 cases/100 patient-years in year 1 and 0.84 cases/100 patient-years in year 2. No cases of tuberculosis, opportunistic infections, or serious hypersensitivity reactions occurred during 2 years of treatment.

Tildrakizumab

Two-year results from the ongoing 5-year extension of the phase 3 reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2 trials were presented by Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, president of Probity Medical Research, Waterloo, Ont. This presentation of 2-year outcomes for 1,237 study participants was a feat, considering that the 12-week results of the trials had been published less than 3 months earlier (Lancet. 2017 Jul 15;390[10091]:276-88).

“I think these data are very compelling that the loss of response over time is minimal,” according to the dermatologist. “We’ve also seen that safety over 2 years has no surprises; in fact, it’s remarkably quiet. The rate of severe infections, which is important to look at for any treatment suppressing the immune system, is low and occurs almost independent of dose, which is very hopeful. It’s a promising sign.”

Indeed, the serious infection rate was 0.8 cases/100 patient-years regardless of whether subjects were on tildrakizumab at 100 mg or 200 mg.

Controversy over how to report long-term outcomes

A hot topic among clinical trialists in dermatology concerns how to report study results. The traditional method in studies funded by pharmaceutical companies is known as the “last observation carried forward” analysis. It casts the study drug results in the most favorable possible light because, when a subject drops out of a trial for any reason, their last measured value for response to treatment is carried forward as though the patient completed the study. Thus, psoriasis patients who drop out because they couldn’t tolerate a therapy or developed a serious side effect dictating discontinuation will be scored on the basis of their last PASI response, creating a bias in favor of active treatment.

A more conservative analytic method is known as the “nonresponder imputation” analysis. By this method, a patient who drops out of a trial is automatically categorized as a treatment failure, even if the reason was that the patient moved and could no longer make visits to the study center.

The prespecified guselkumab analysis presented by Dr. Blauvelt involved nonresponder imputation through year 1 and imputation based on the reason for discontinuation in the second year. In contrast, the 2-year tildrakizumab analysis presented by Dr. Papp used the far more common last observation carried forward method.

To help the audience appreciate the importance of looking at the analytic methods used in a studies and help them understand the clinical significance of the results, Dr. Blauvelt provided a reanalysis of the 2-year guselkumab data using the last observation carried forward method. Across the board, the numbers became more favorable. For example, the PASI 75 rate of 95.7% using the prespecified nonresponder imputation analysis crept up to 96.8% under the last observation carried forward method; for comparison, the PASI 75 rates were 81%-84% in the tildrakizumab analysis.

“If you wanted to compare apples to apples with some other drugs, you would use these numbers – the as-observed analysis numbers used by most other companies with other drugs. If you wanted to determine what the true-life numbers are, they’d probably be something between the nonresponder imputation and as-observed numbers,” said to Dr. Blauvelt.

Dr. Papp was untroubled by the use of the last observation carried forward method in the particular case of the tildrakizumab long-term extension study.

“There is reason to believe the as-observed analysis doesn’t affect the integrity of the data because the dropout rate is extraordinarily low,” he said.

The guselkumab analysis was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceutica; the tildrakizumab analysis was sponsored by Merck and by Sun Pharma. Dr. Blauvelt and Dr. Papp were paid investigators in both studies and serve as scientific advisers to virtually all companies invested in the psoriasis therapy developmental pipeline.

GENEVA – The merits of addressing interleukin-23 as a novel therapeutic target in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were abundantly displayed in 2-year outcomes data for two anti–IL-23 monoclonal antibodies – guselkumab and tildrakizumab – in studies presented back to back at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.