User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Melasma

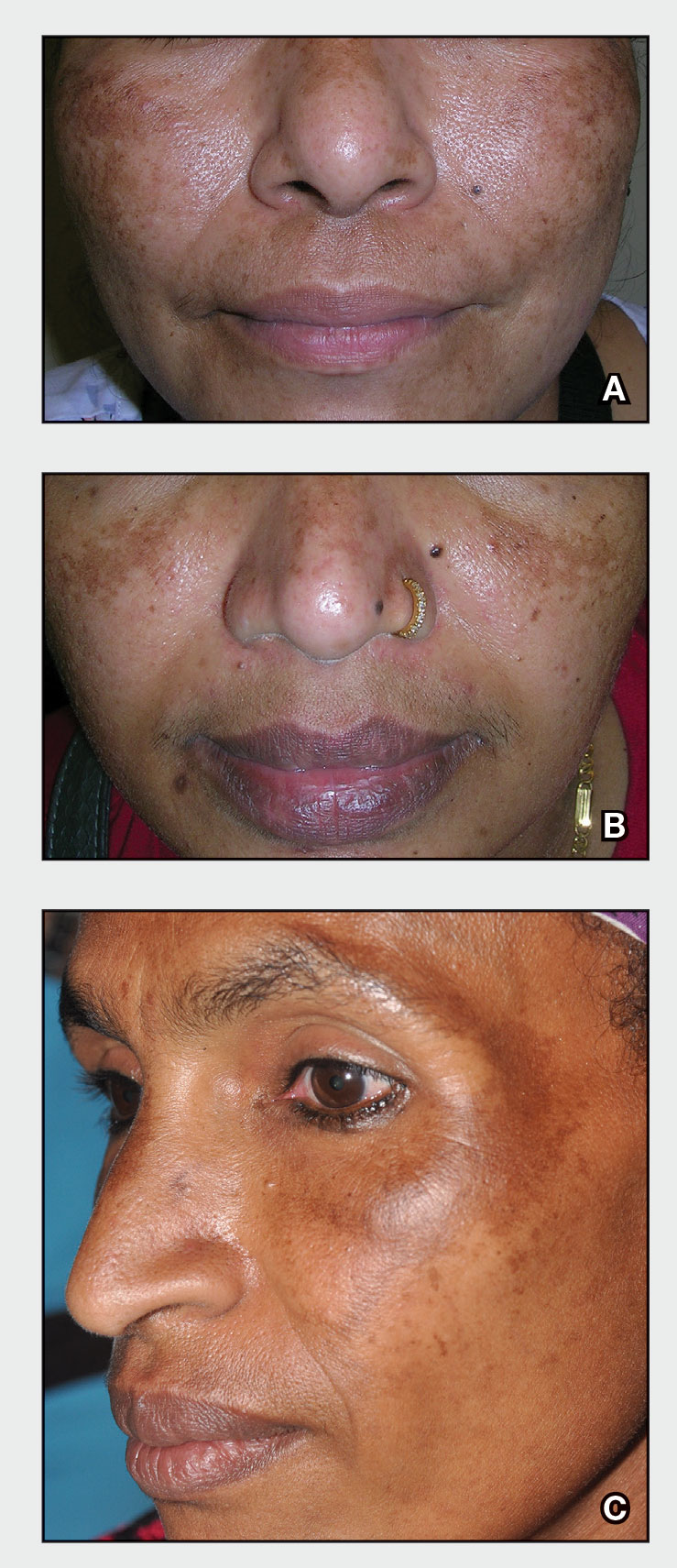

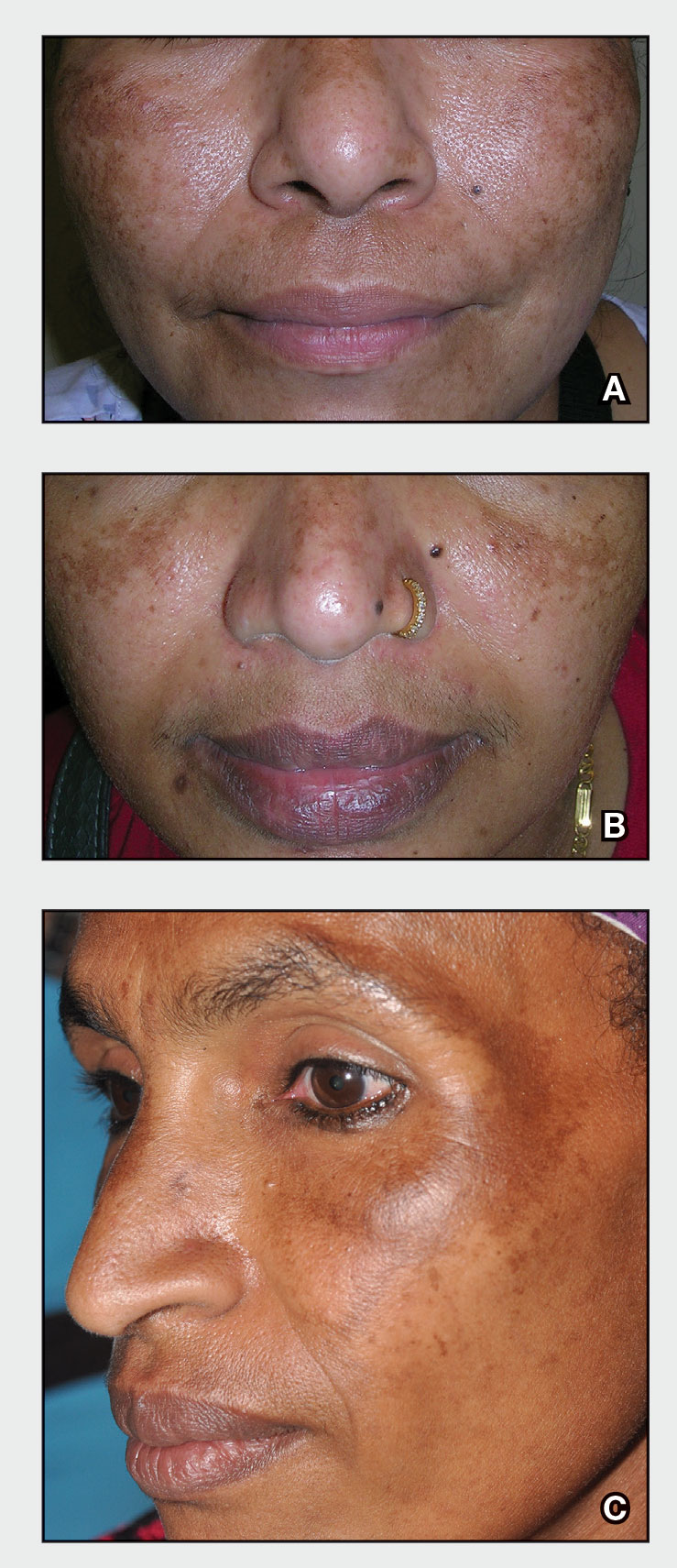

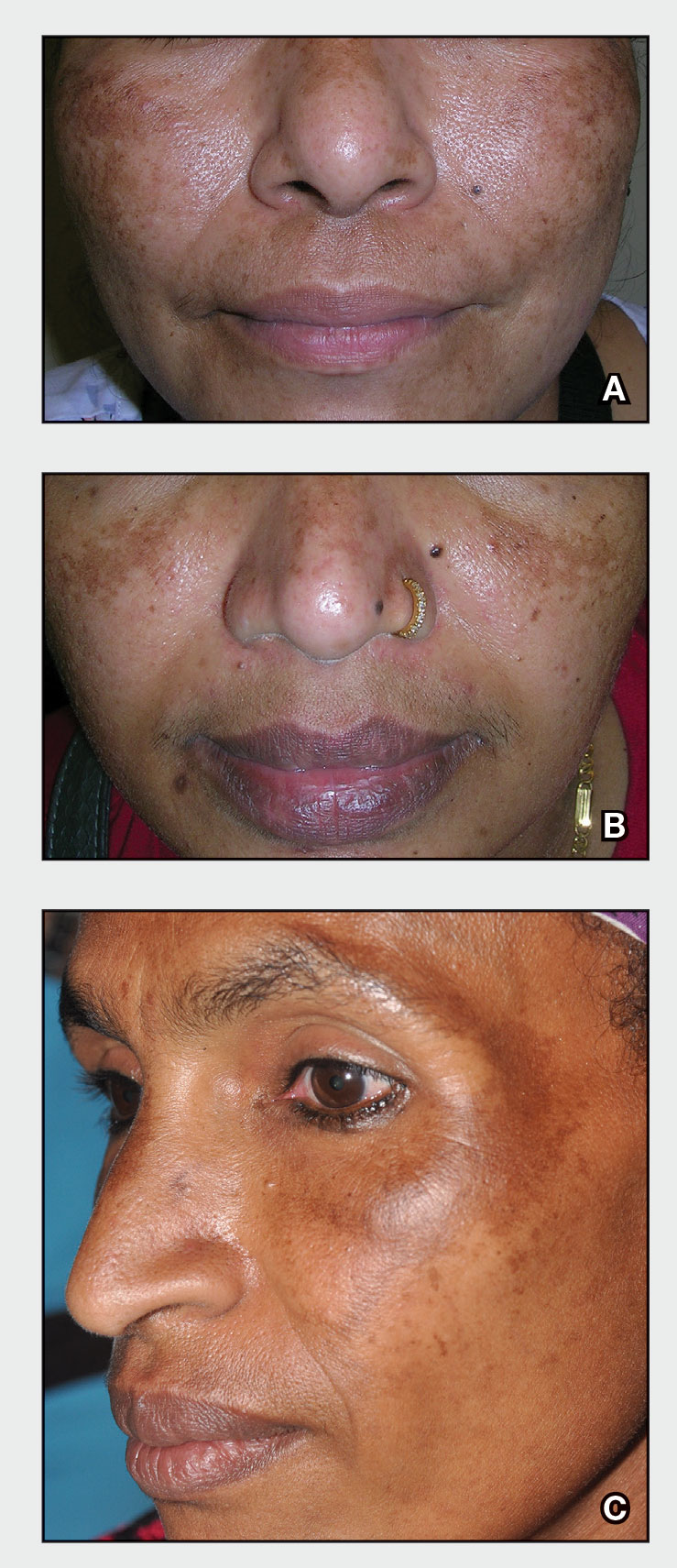

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

Recurrent Oral and Gluteal Cleft Erosions

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

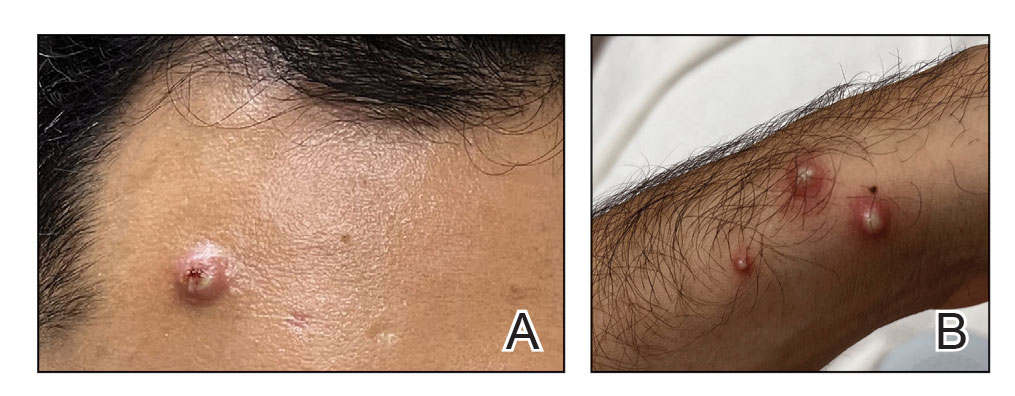

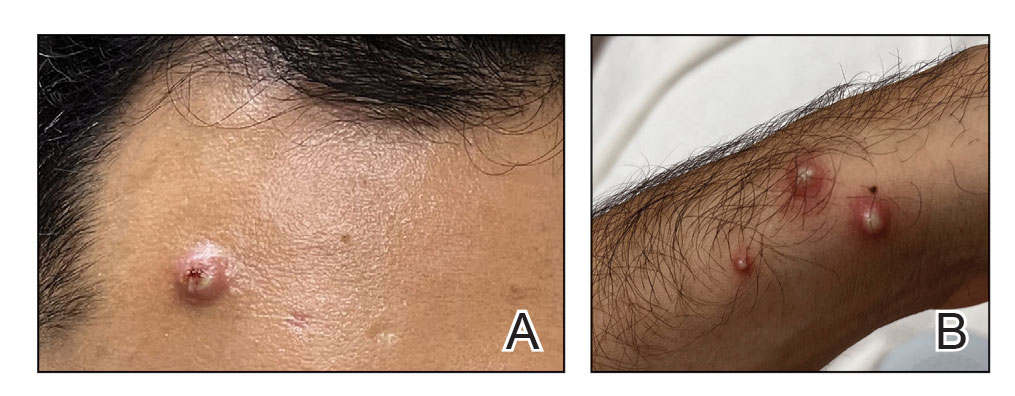

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

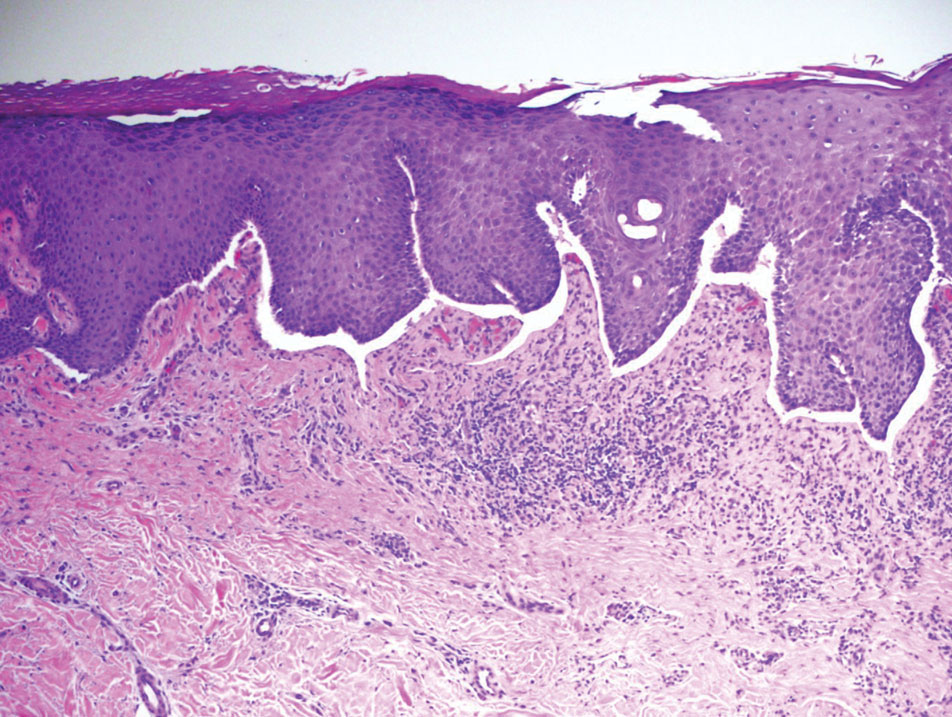

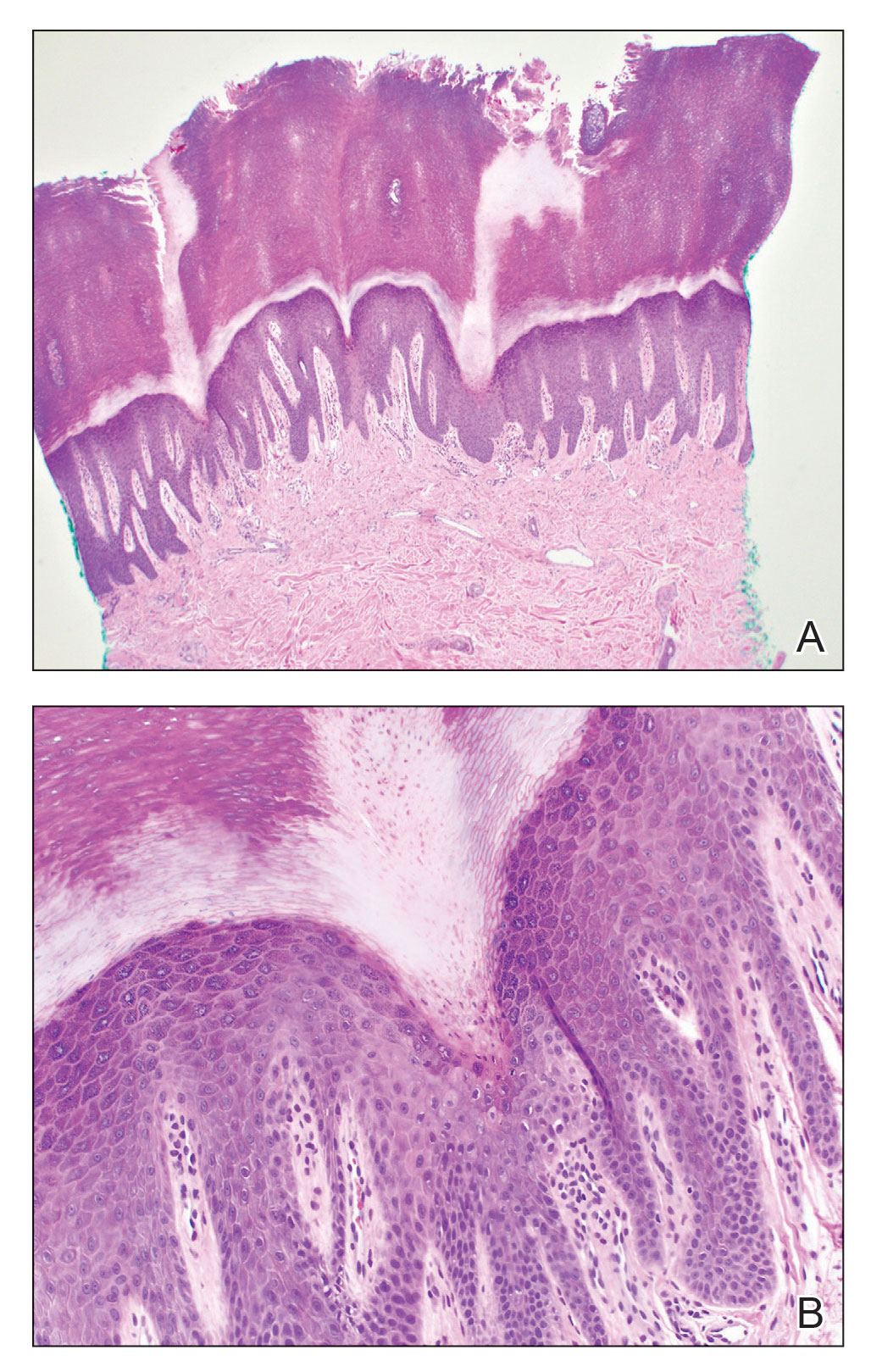

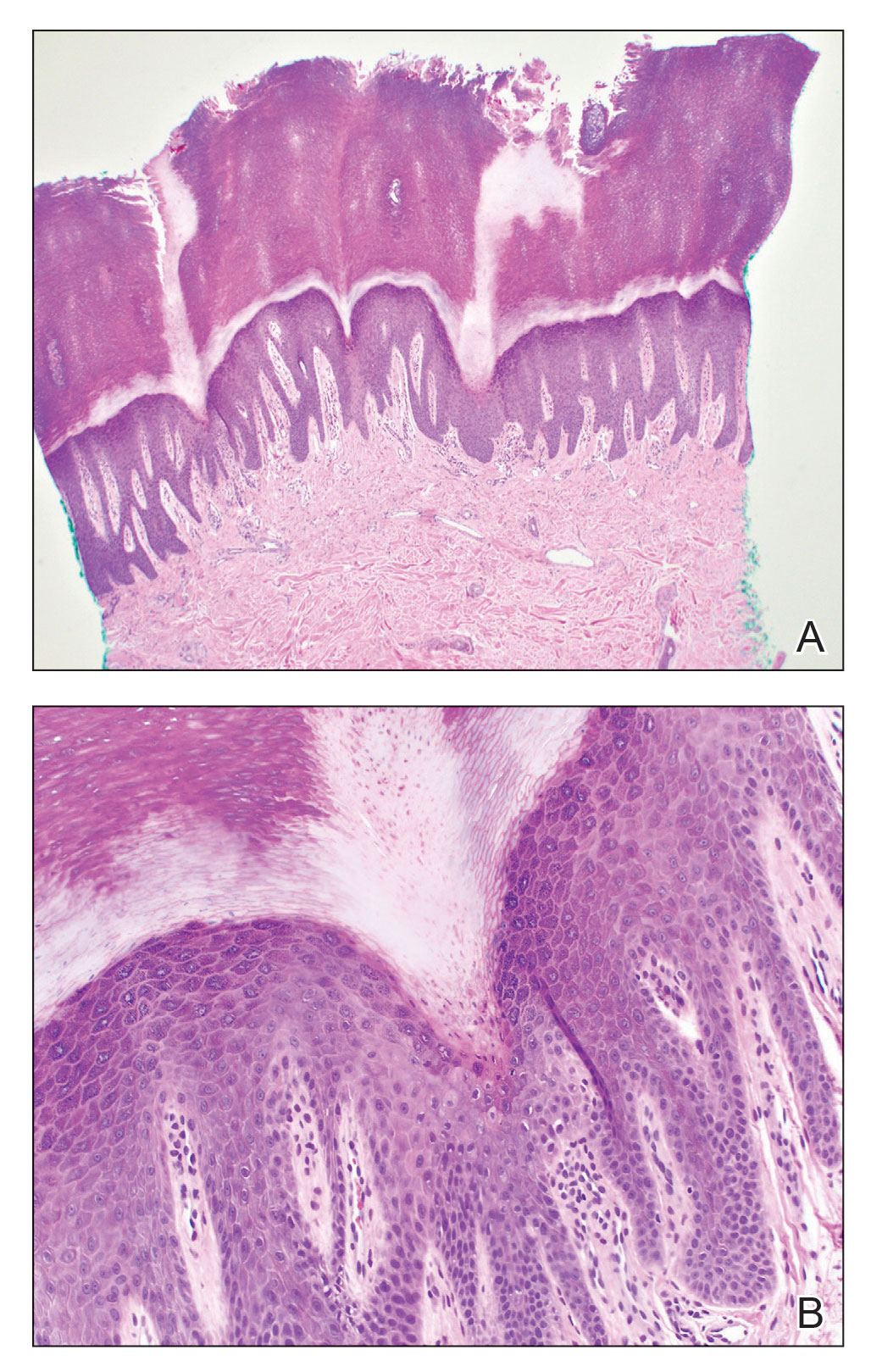

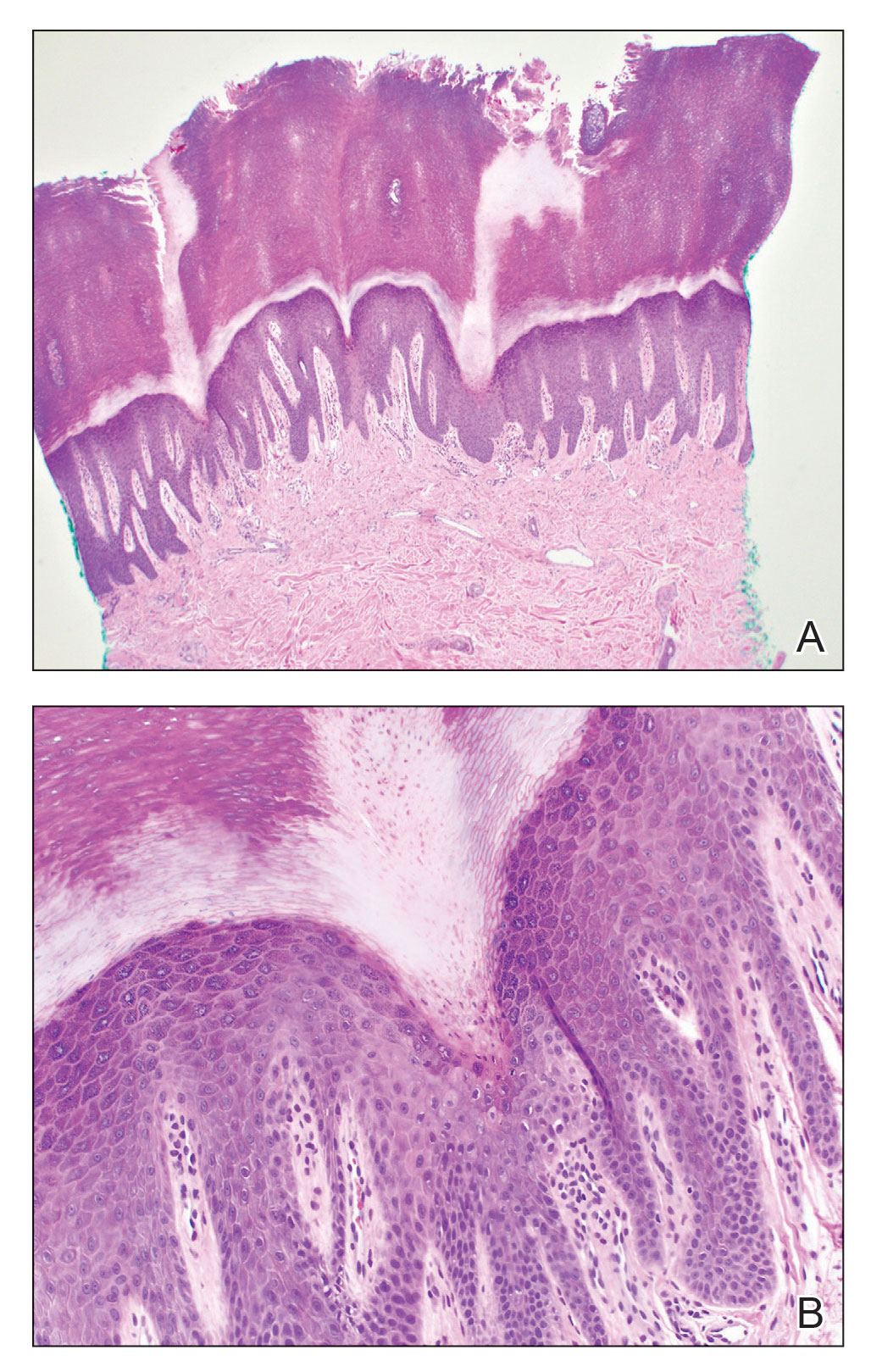

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

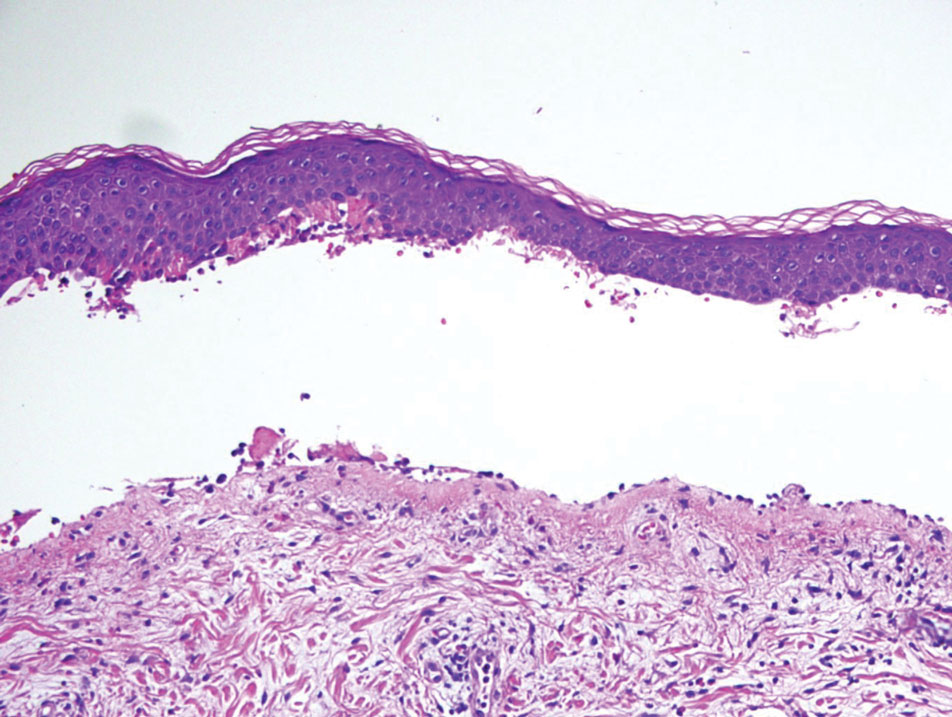

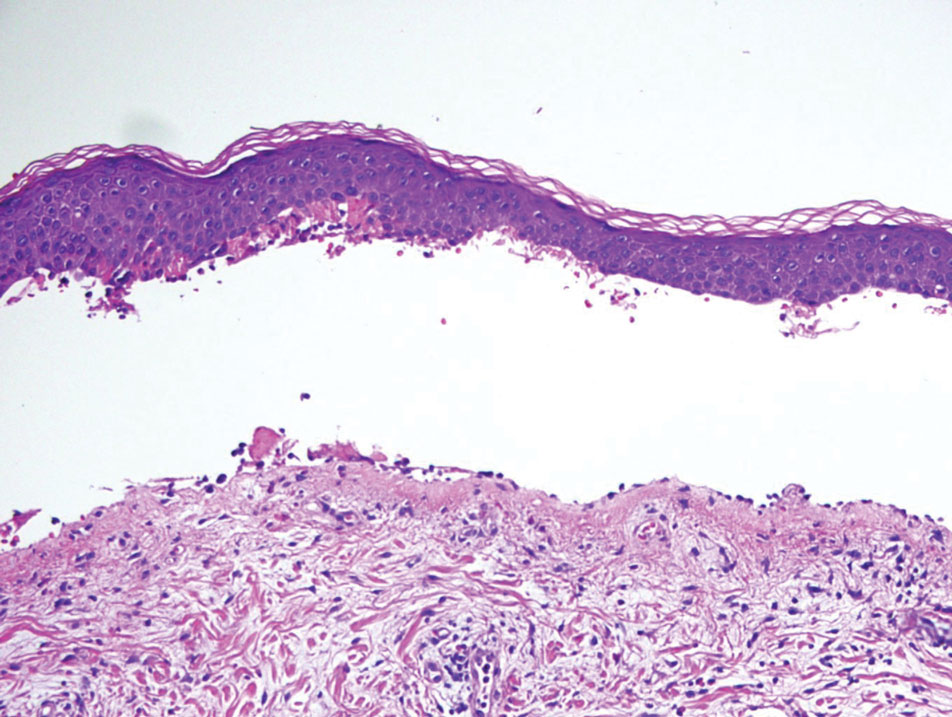

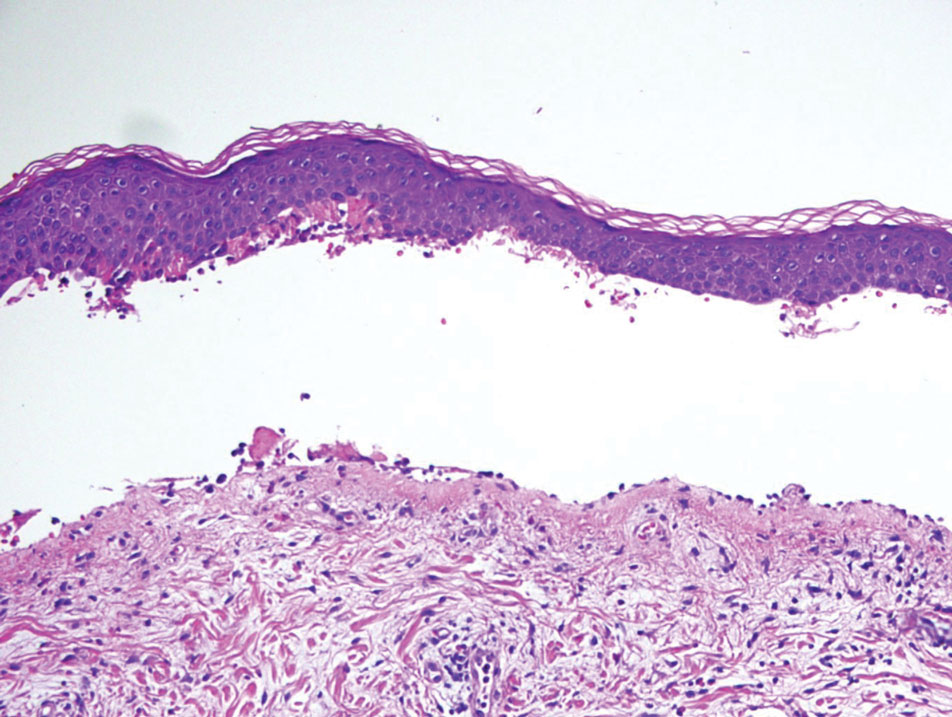

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

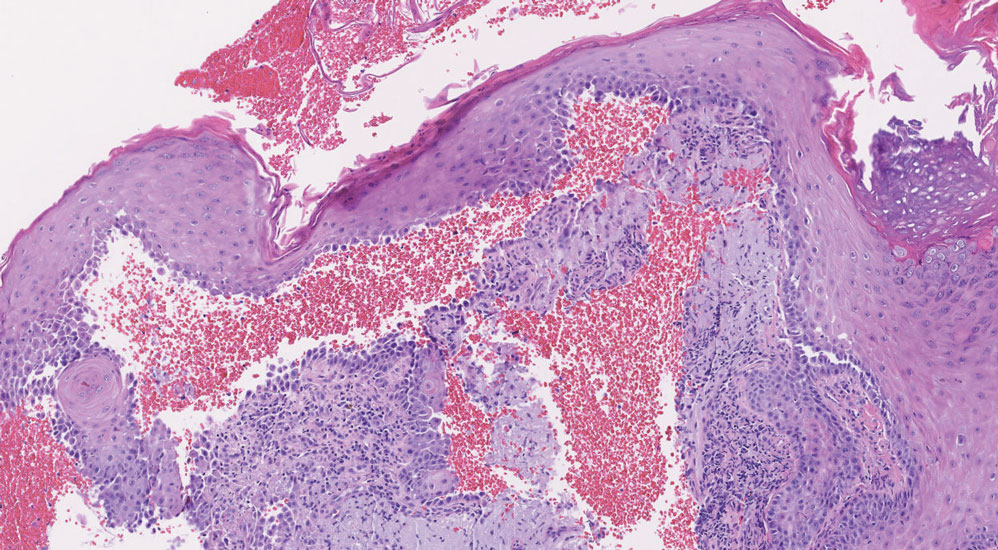

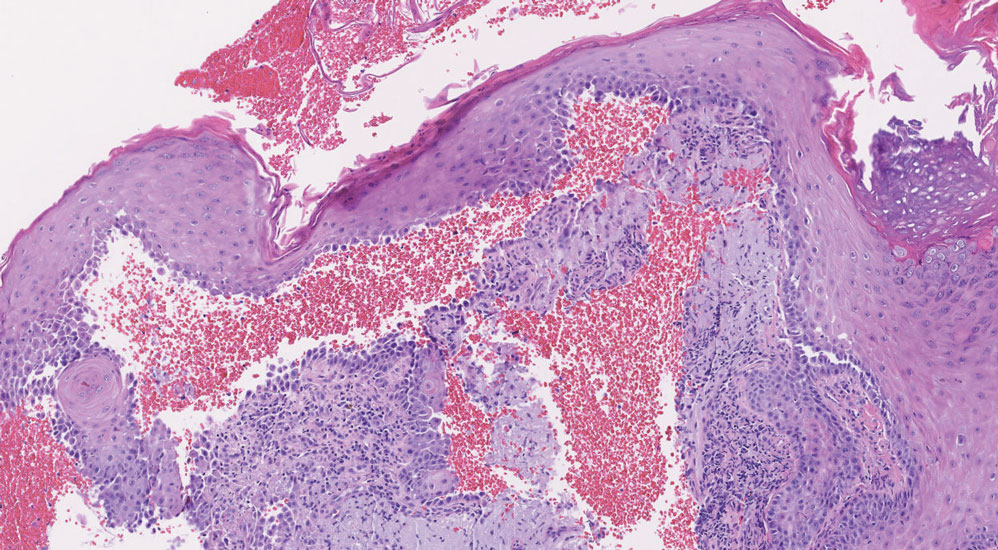

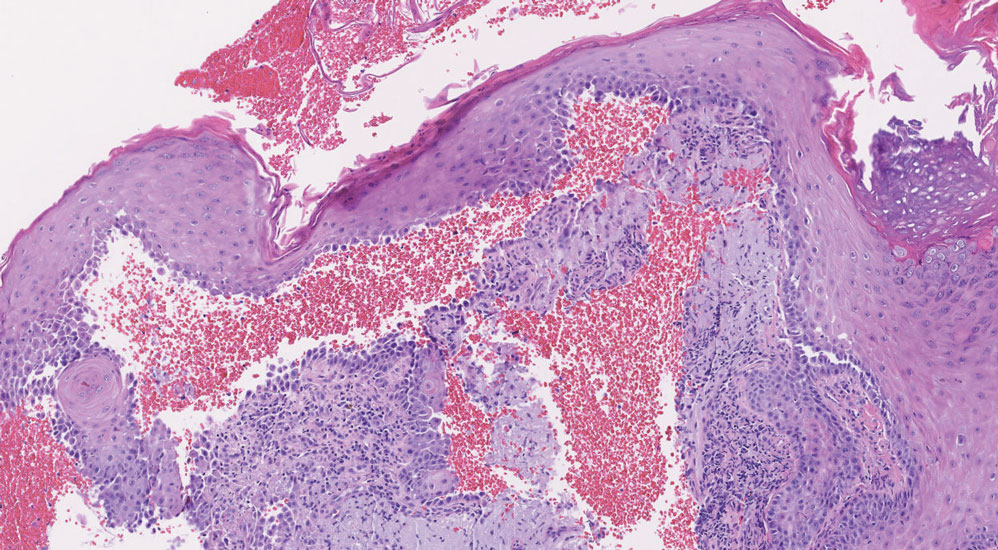

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

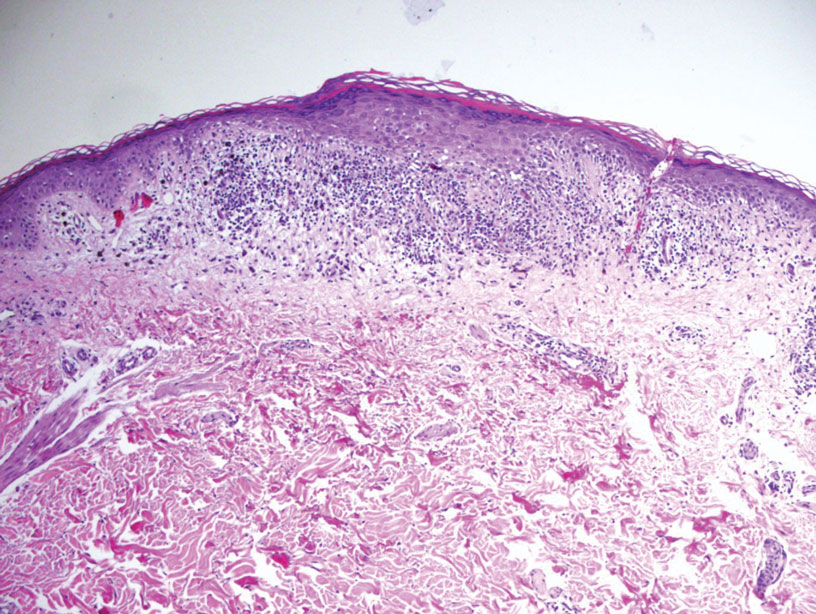

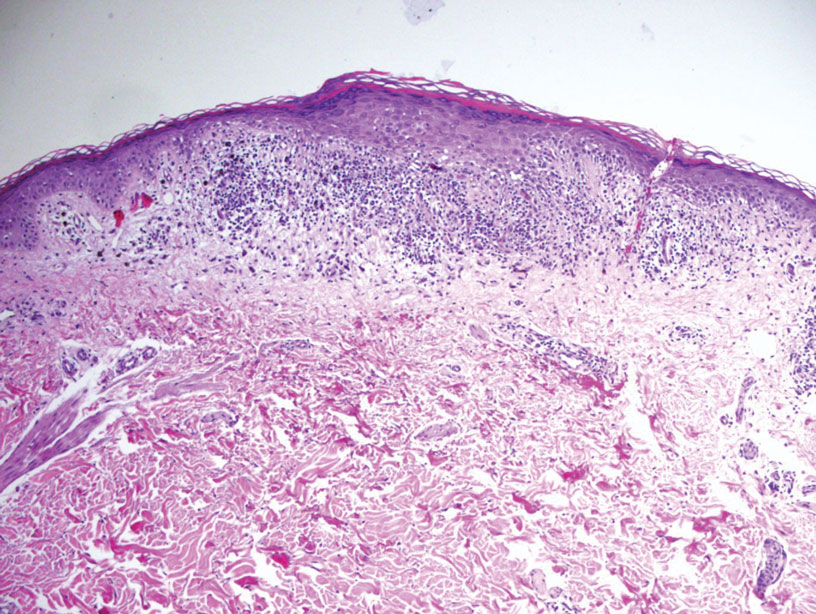

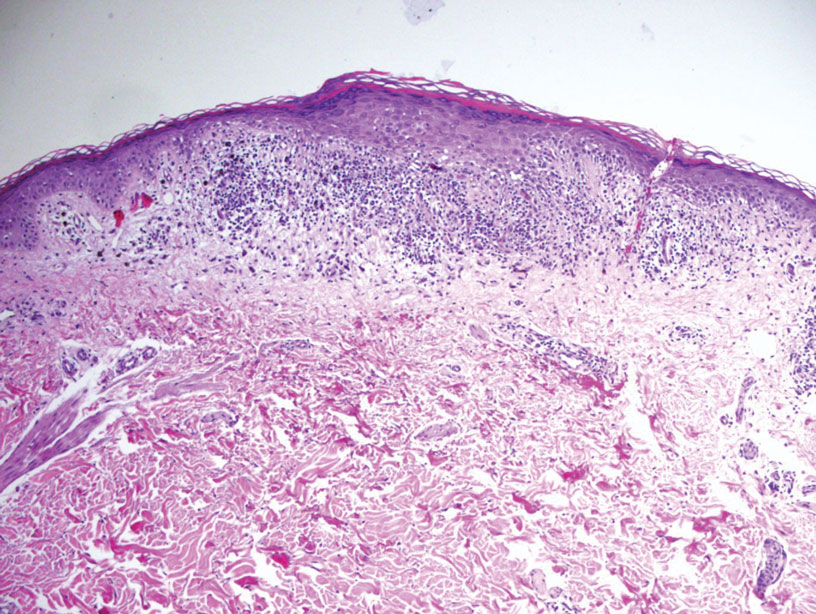

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

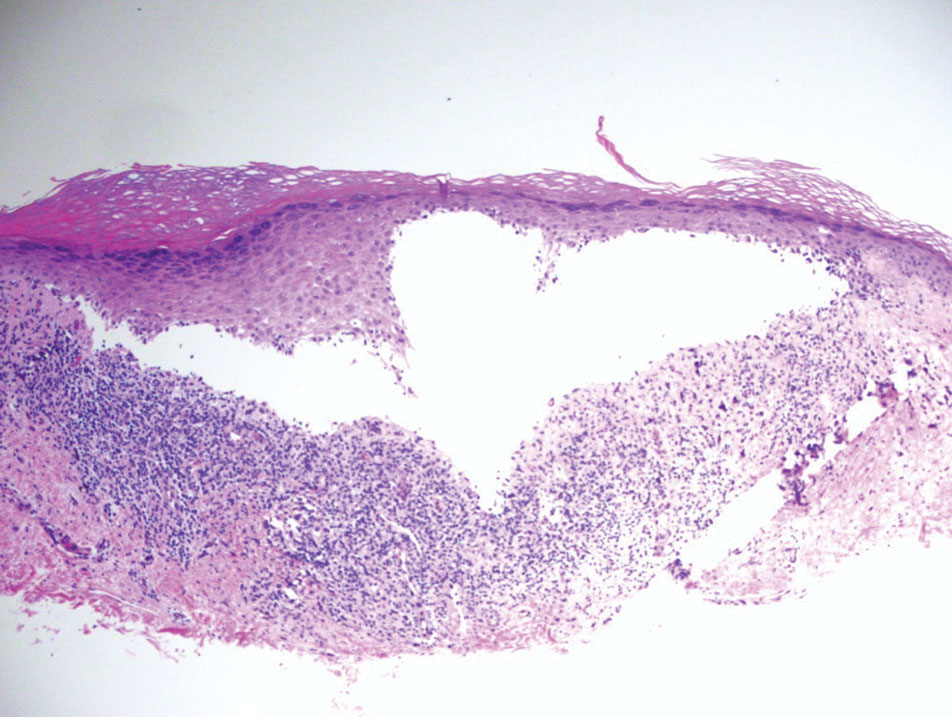

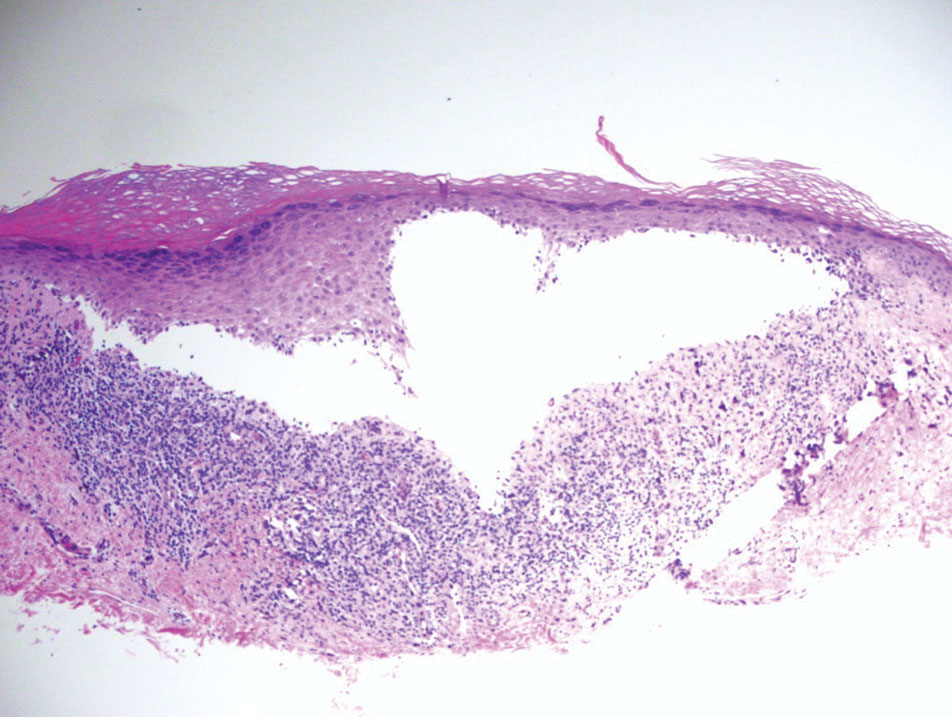

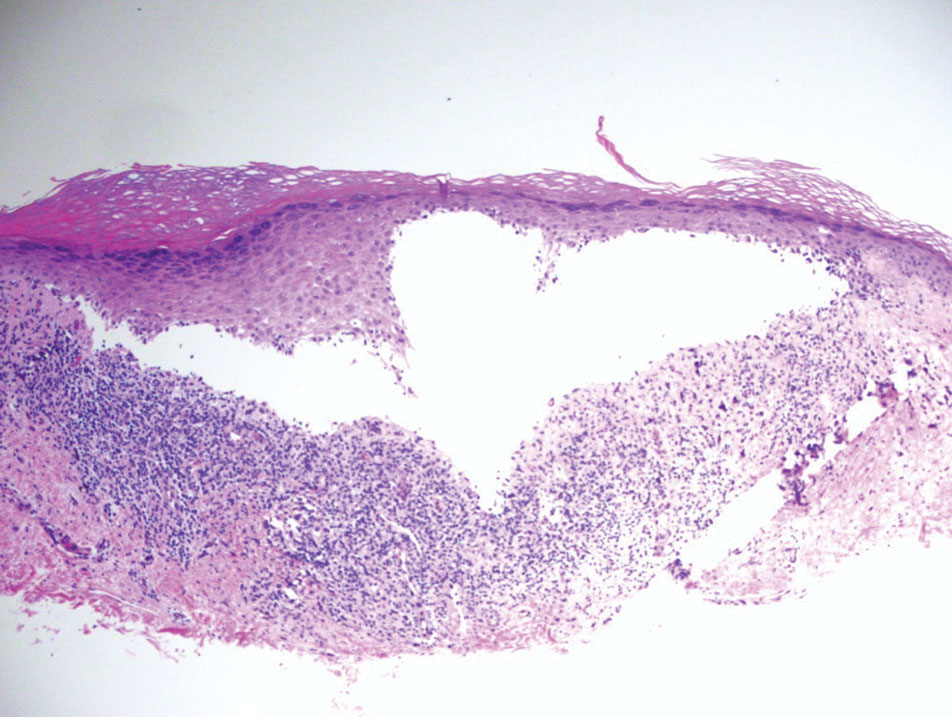

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

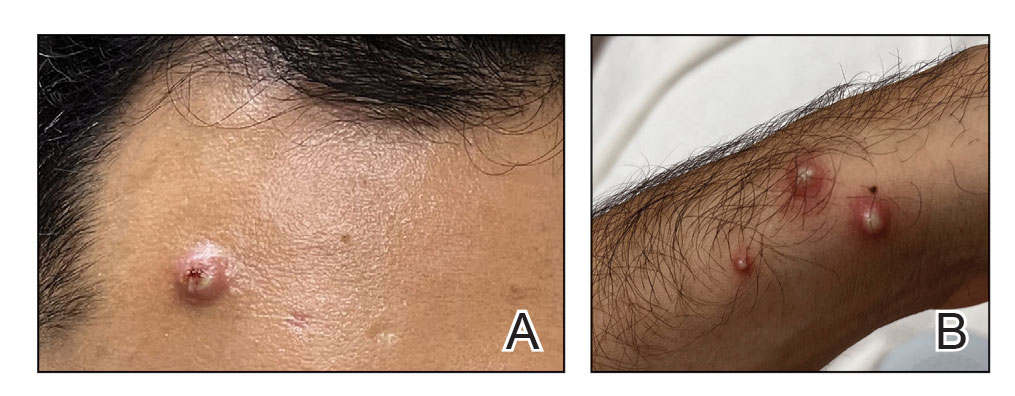

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

A 71-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented with recurrent painful erosions on the gingivae and gluteal cleft of 1 year’s duration. She previously was diagnosed by her periodontist with erosive lichen planus and was prescribed topical and oral steroids with minimal improvement. She denied fever, chills, weakness, fatigue, vision changes, eye pain, and sore throat. Dermatologic examination revealed edematous and erythematous upper and lower gingivae with mild erosions, as well as thin, eroded, erythematous plaques within the gluteal cleft. Indirect immunofluorescence revealed IgG with epidermal localization in a human split-skin substrate, and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed positive IgG to bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and negative IgG to BP230. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the gluteal cleft was performed.

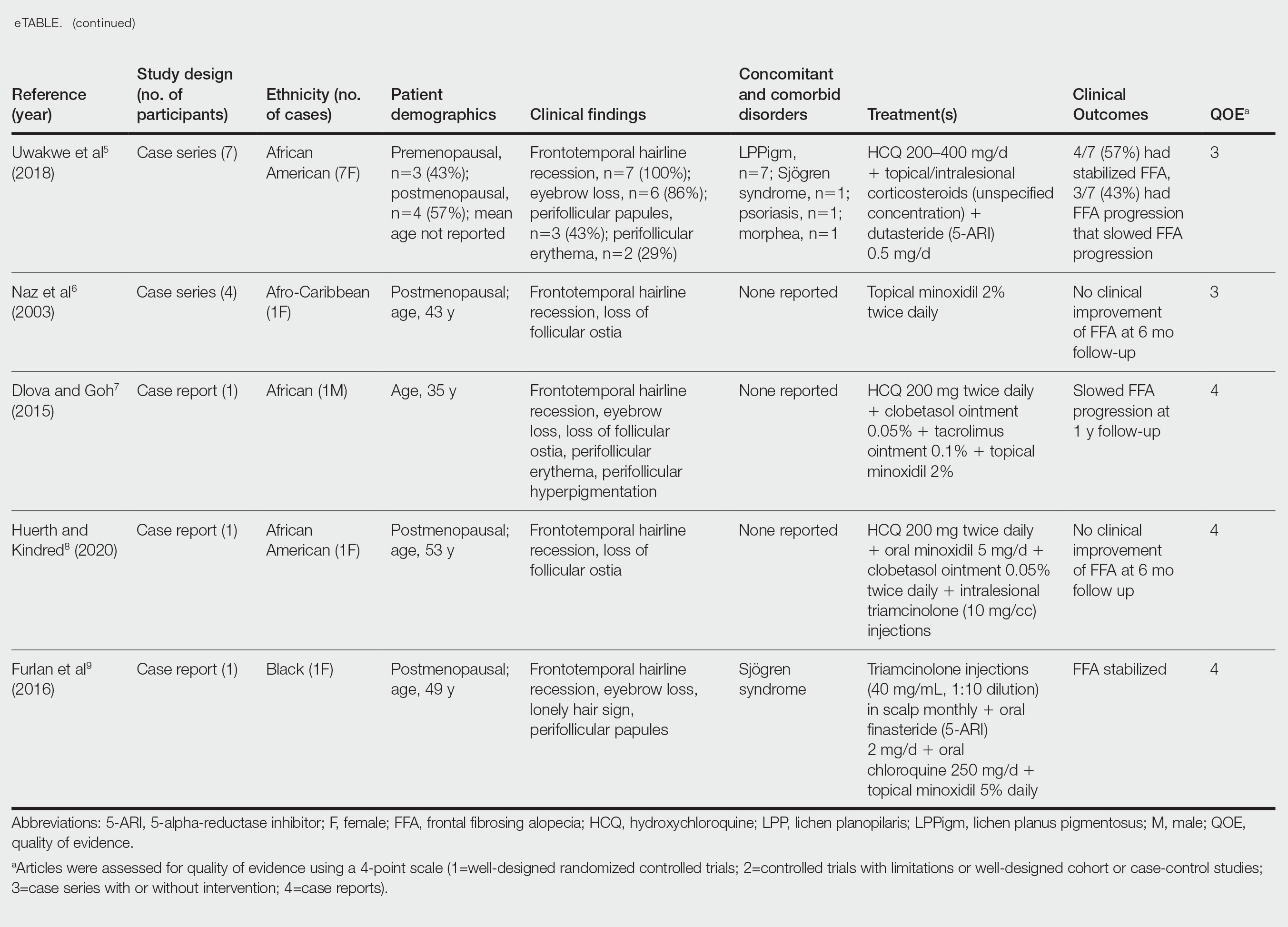

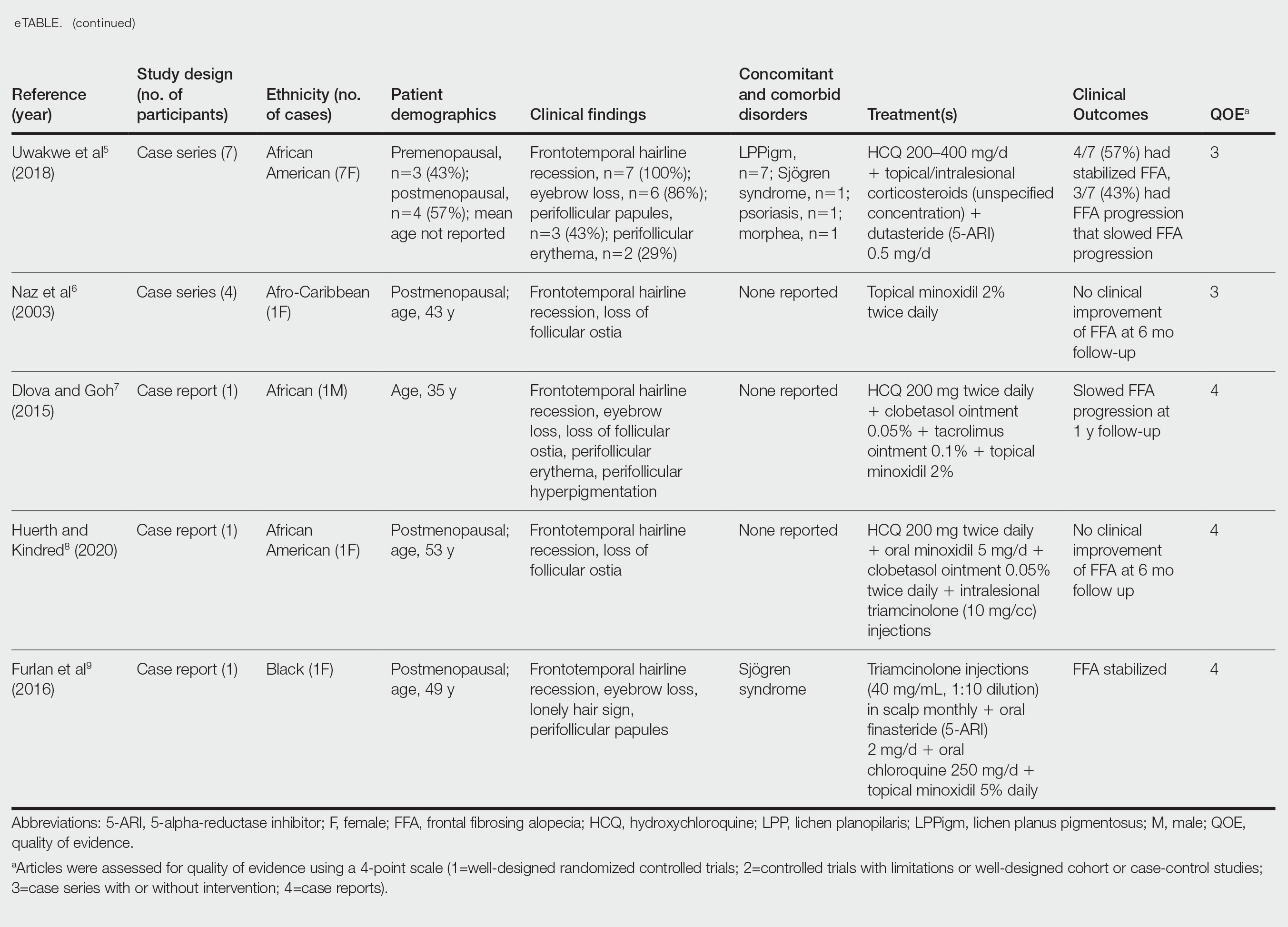

Treatment of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in Black Patients: A Systematic Review

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

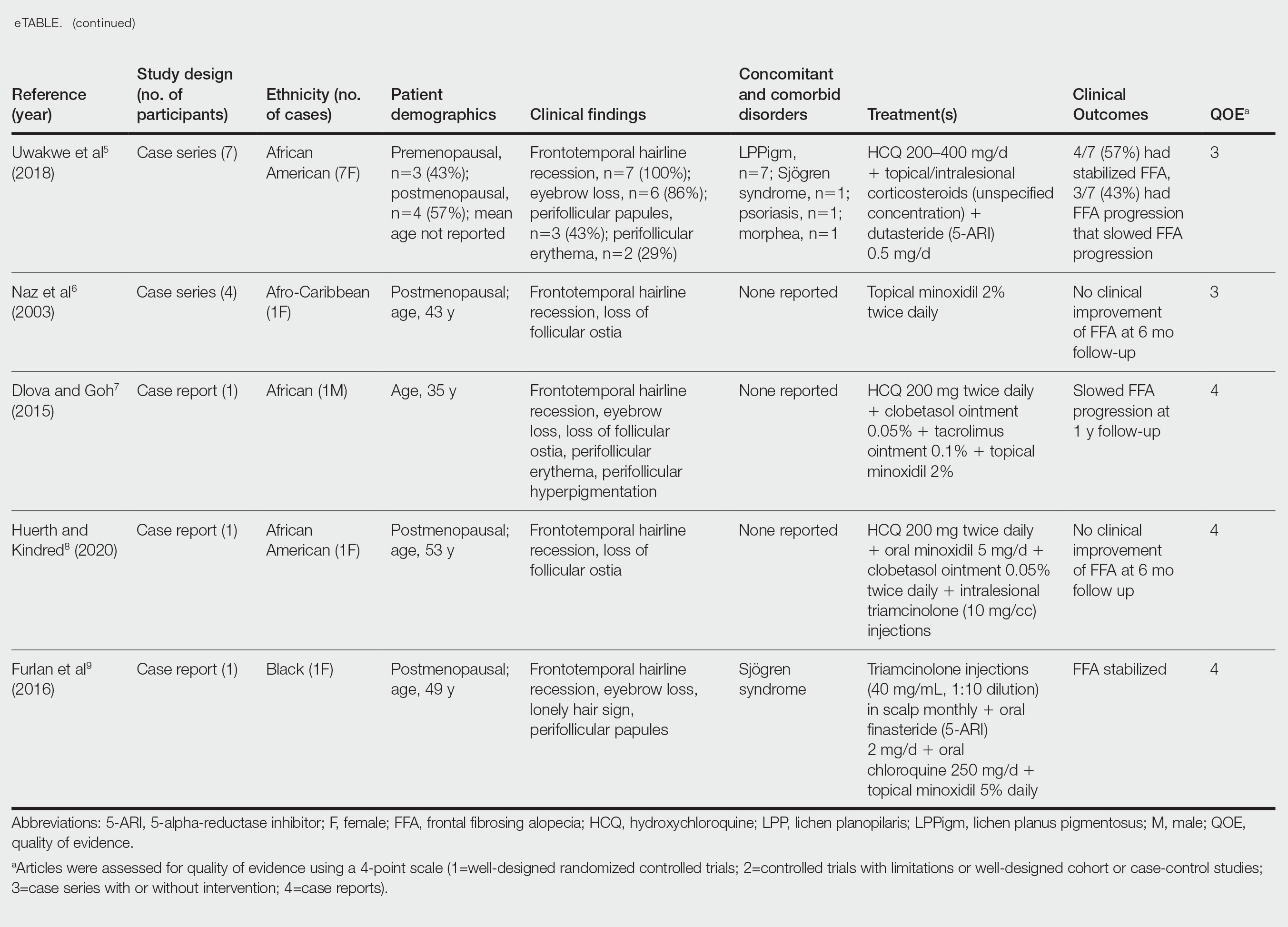

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.

Patients frequently presented with scalp pruritus (26/51 [51.0%]), perifollicular papules or pustules (9/51 [17.6%]), and perifollicular hyperpigmentation (9/51 [17.6%]). Other associated symptoms included perifollicular erythema (6/51 [11.8%]), scalp pain (5/51 [9.8%]), hyperkeratosis or flaking (3/51 [5.9%]), and facial papules (2/51 [3.9%]). Loss of follicular ostia, prominent follicular ostia, and the lonely hair sign (Figure 2) was described in 21 (41.2%), 5 (9.8%), and 15 (29.4%) of patients, respectively. Hairstyles that involve scalp traction (19/51 [37.3%]) and/or chemicals (28/51 [54.9%]), such as hair dye or chemical relaxers, commonly were reported in patients prior to the onset of FFA.

The most commonly reported dermatologic comorbidities included traction alopecia (17/51 [33.3%]), followed by lichen planus pigmentosus (LLPigm)(7/51 [13.7%]), LPP (2/51 [3.9%]), psoriasis (1/51 [2.0%]), and morphea (1/51 [2.0%]). Reported comorbid diseases included Sjögren syndrome (2/51 [3.9%]), hypothyroidism (2/51 [3.9%]), HIV (1/51 [2.0%]), and diabetes mellitus (1/51 [2.0%]).

Of available reports (n=32), the most common histologic findings included perifollicular fibrosis (23/32 [71.9%]), lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation (22/23 [95.7%]) primarily affecting the isthmus and infundibular areas of the follicles, and decreased follicular density (21/23 [91.3%]).

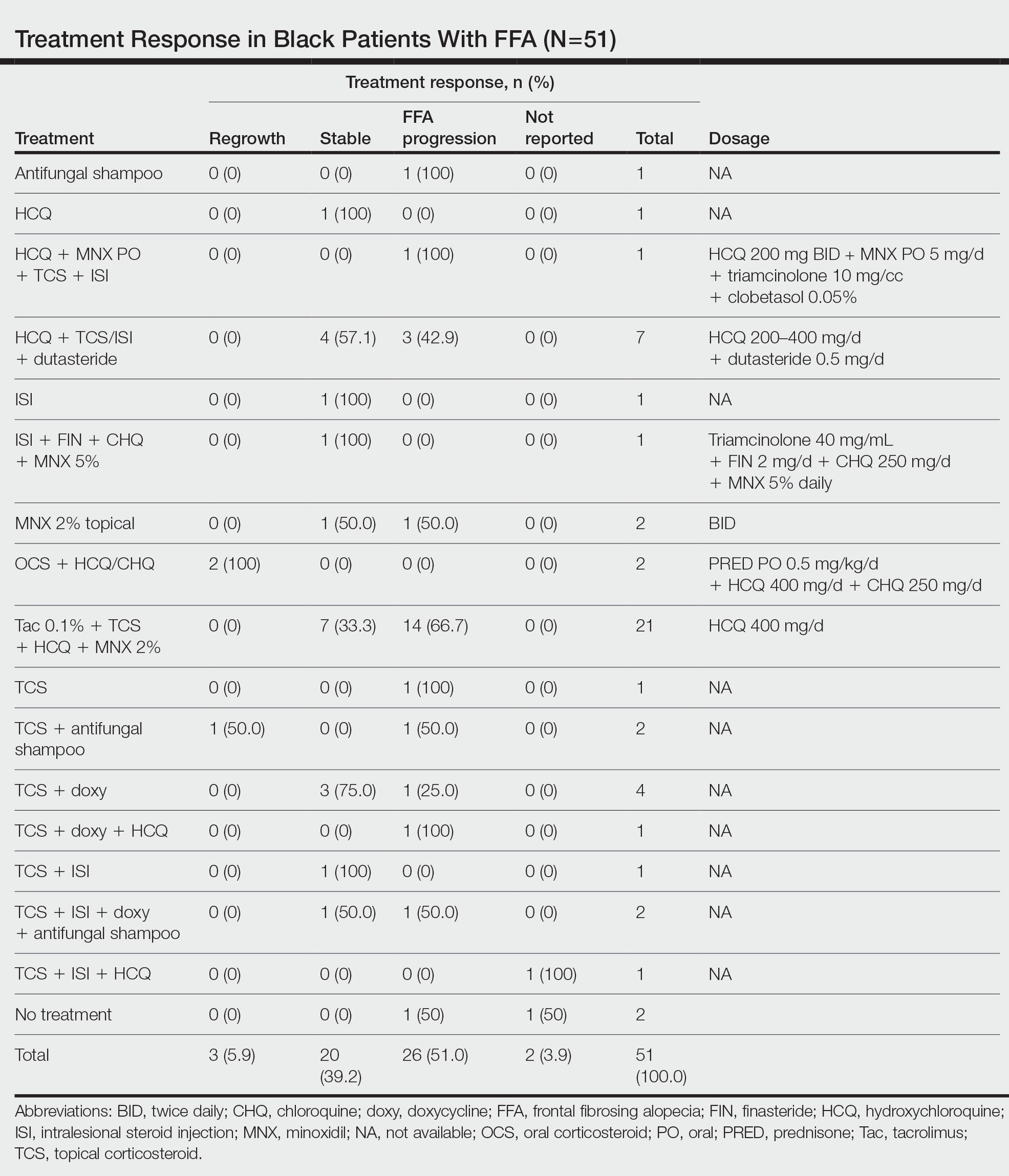

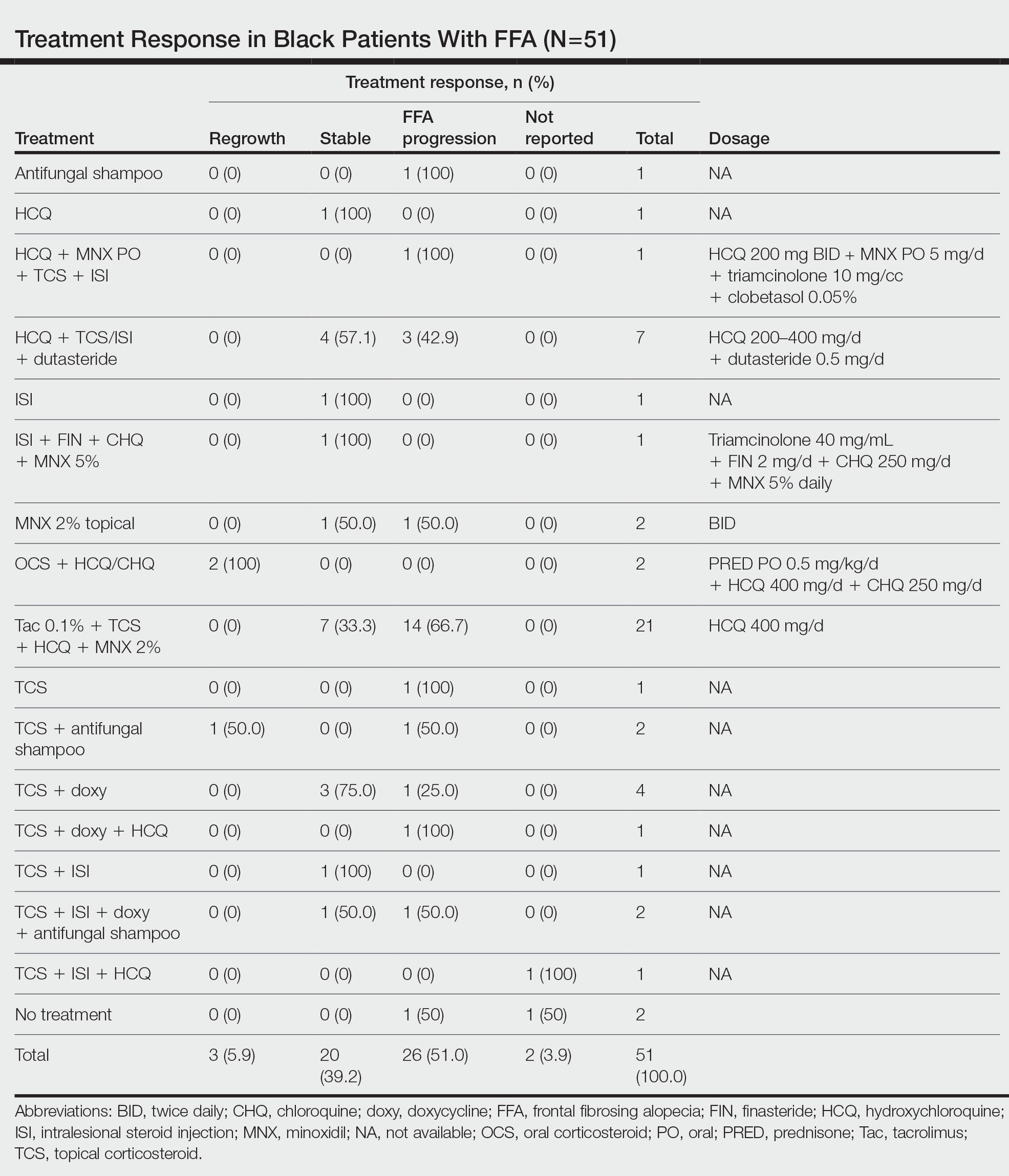

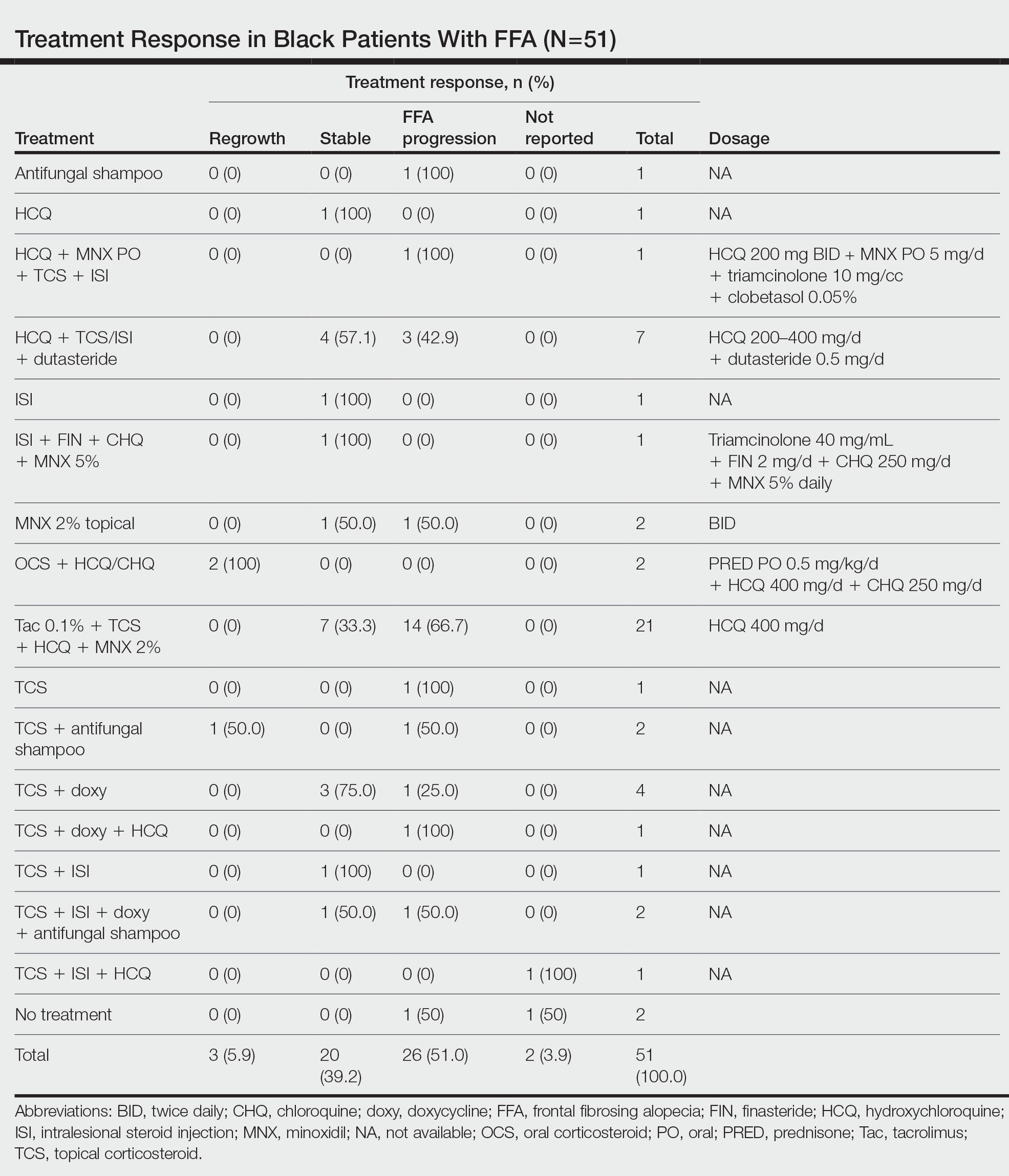

The average time interval from treatment initiation to treatment assessment in available reports (n=25) was 1.8 years (range, 0.5–2 years). Response to treatment included regrowth of hair in 5.9% (3/51) of patients, FFA stabilization in 39.2% (20/51), FFA progression in 51.0% (26/51), and not reported in 3.9% (2/51). Combination therapy was used in 84.3% (43/51) of patients, while monotherapy was used in 11.8% (6/51), and 3.9% (2/51) did not have any treatment reported. Response to treatment was highly variable among patients, as were the combinations of therapeutic agents used (Table). Regrowth of hair was rare, occurring in only 2 (100%) patients treated with oral prednisone plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CHQ), and in 1 (50.0%) patient treated with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal shampoo, while there was no response in the other patient treated with this combination.

Improvement in hair loss, defined as having at least slowed progression of FFA, was observed in 100% (2/2) of patients who had oral steroids as part of their treatment regimen, followed by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs)(finasteride and dutasteride; 62.5% [5/8]), intralesional steroids (57.1% [8/14]), HCQ/CHQ (42.9% [15/35]), topical steroids (41.5% [17/41]), antifungal shampoo (40.0% [2/5]), topical/oral minoxidil (36.0% [9/25]), and tacrolimus (33.3% [7/21]).

Comment

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a progressive scarring alopecia and a clinical variant of LPP. First described in 1994 by Kossard,1 it initially was thought to be a disease of postmenopausal White women. Although still most prevalent in White individuals, there has been a growing number of reports describing FFA in patients with SOC, including Black individuals.10 Despite the increasing number of cases over the years, studies on the treatment of FFA remain sparse. Without expert guidelines, treatments usually are chosen based on clinician preferences. Few observational studies on these treatment modalities and their clinical outcomes exist, and the cohorts largely are composed of White patients.10-12 However, Black individuals may respond differently to these treatments, just as they have been shown to exhibit unique features of FFA.3

Demographics of Patients With FFA—Consistent with our findings, prior studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be younger and premenopausal at FFA onset than their White counterparts.13-15 Among the Black individuals included in our review, the majority were premenopausal (53%) with an average age of FFA onset of 46.7 years. Conversely, only 5% of 60 White females with FFA reported in a retrospective review were premenopausal and had an older mean age of FFA onset of 64 years,1 substantiating prior reports.

Clinical Findings in Patients With FFA—The clinical findings observed in our cohort were consistent with what has previously been described in Black patients, including loss of follicular ostia (41.2%), lonely hair sign (29.4%), perifollicular erythema (11.8%), perifollicular papules (17.6%), and hyperkeratosis or flaking (5.9%). In comparing these findings with a review of 932 patients, 86% of whom were White, the observed frequencies of follicular ostia loss (38.3%) and lonely hair sign (26.7%) were similar; however, perifollicular erythema (44.2%), and hyperkeratosis (44.4%) were more prevalent in this group, while perifollicular papules (6.2%) were less common compared to our Black cohort.16 An explanation for this discrepancy in perifollicular erythema may be the increased skin pigmentation diminishing the appearance of erythema in Black individuals. Our cohort of Black individuals noted the presence of follicular hyperpigmentation (17.6%) and a high prevalence of scalp pruritus (51.0%), which appear to be more common in Black patients.3,17 Although it is unclear why these differences in FFA presentation exist, it may be helpful for clinicians to be aware of these unique features when examining Black patients with suspected FFA.

Concomitant Cutaneous Disorders—A notable proportion of our cohort also had concomitant traction alopecia, which presents with frontotemporal alopecia, similar to FFA, making the diagnosis more challenging; however, the presence of perifollicular hyperpigmentation and facial hyperpigmentation in FFA may aid in differentiating these 2 entities.3 Other concomitant conditions noted in our review included androgenic alopecia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, hypothyroidism, morphea, and HIV, suggesting a potential interplay between autoimmune, genetic, hormonal, and environmental components in the etiology of FFA. In fact, a recent study found that a persistent inflammatory response, loss of immune privilege, and a genetic susceptibility are some of the key processes in the pathogenesis of FFA.18 Although the authors speculated that there may be other triggers in initiating the onset of FFA, such as steroid hormones, sun exposure, and topical allergens, more evidence and controlled studies are needed

Additionally, concomitant LPPigm occurred in 13.7% of our FFA cohort, which appears to be more common in patients with darker skin types.5,19-21 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a rare variant of LPP, and previous reports suggest that it may be associated with FFA.5 Similar to FFA, the pathogenesis of LPPigm also is unclear, and its treatment may be just as difficult.22 Because LPPigm may occur before, during, or after onset of FFA,23 it may be helpful for clinicians to search for the signs of LPPigm in patients with darker skin types patients presenting with hair loss both as a diagnostic clue and so that treatment may be tailored to both conditions.

Response to Treatment—Similar to the varying clinical pictures, the response to treatment also can vary between patients of different ethnicities. For Black patients, treatment outcomes did not seem as successful as they did for other patients with SOC described in the literature. A retrospective cohort of 58 Asian individuals with FFA found that up to 90% had improvement or stabilization of FFA after treatment,23 while only 45.1% (23/51) of the Black patients included in our study had improvement or stabilization. One reason may be that a greater proportion of Black patients are premenopausal at FFA onset (53%) compared to what is reported in Asian patients (28%),23 and women who are premenopausal at FFA onset often face more severe disease.15 Although there may be additional explanations for these differences in treatment outcomes between ethnic groups, further investigation is needed.

All patients included in our study received either monotherapy or combination therapy of topical/intralesional/oral steroids, HCQ or CHQ, 5-ARIs, topical/oral minoxidil, antifungal shampoo, and/or a calcineurin inhibitor; however, most patients (51.0%) did not see a response to treatment, while only 45.1% showed slowed or halted progression of FFA. Hair regrowth was rare, occurring in only 3 (5.9%) patients; 2 of them were the only patients treated with oral prednisone, making for a potentially promising therapeutic for Black patients that should be further investigated in larger controlled cohort studies. In a prior study, intramuscular steroids (40 mg every 3 weeks) plus topical minoxidil were unsuccessful in slowing the progression of FFA in 3 postmenopausal women,24 which may be explained by the racial differences in the response to FFA treatments and perhaps also menopausal status. Although not included in any of the regimens in our review, isotretinoin was shown to be effective in an ethnically unspecified group of patients (n=16) and also may be efficacious in Black individuals.25 Although FFA may stabilize with time,26 this was not observed in any of the patients included in our study; however, we only included patients who were treated, making it impossible to discern whether resolution was idiopathic or due to treatment.

Future Research—Research on treatments for FFA is lacking, especially in patients with SOC. Although we observed that there may be differences in the treatment response among Black individuals compared to other patients with SOC, additional studies are needed to delineate these racial differences, which can help guide management. More randomized controlled trials evaluating the various treatment regimens also are required to establish treatment guidelines. Frontal fibrosing alopecia likely is underdiagnosed in Black individuals, contributing to the lack of research in this group. Darker skin can obscure some of the clinical and dermoscopic features that are more visible in fair skin. Furthermore, it may be challenging to distinguish clinical features of FFA in the setting of concomitant traction alopecia, which is more common in Black patients.27 Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting in Black women also is less likely to be biopsied, contributing to the tendency to miss FFA in favor of traction or androgenic alopecia, which often are assumed to be more common in this population.2,27 Therefore, histologic evaluation through biopsy is paramount in securing an accurate diagnosis for Black patients with frontotemporal alopecia.

Study Limitations—The studies included in our review were limited by a lack of control comparison groups, especially among the retrospective cohort studies. Additionally, some of the studies included cases refractory to prior treatment modalities, possibly leading to a selection bias of more severe cases that were not representative of FFA in the general population. Thus, further studies involving larger populations of those with SOC are needed to fully evaluate the clinical utility of the current treatment modalities in this group.

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

- Dlova NC, Jordaan HF, Skenjane A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 20 black patients from South Africa. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:939-941. doi:10.1111/bjd.12424

- Callender VD, Reid SD, Obayan O, et al. Diagnostic clues to frontal fibrosing alopecia in patients of African descent. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:45-51.

- Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, et al. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424-1427. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.321

- Uwakwe LN, Cardwell LA, Dothard EH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and concomitant lichen planus pigmentosus: a case series of seven African American women. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:397-400.

- Naz E, Vidaurrázaga C, Hernández-Cano N, et al. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:25-27. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01131.x

- Dlova NC, Goh CL. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in an African man. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:81-83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05821.x

- Huerth K, Kindred C. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting as androgenetic alopecia in an African American woman. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:794-795. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4682

- Furlan KC, Kakizaki P, Chartuni JC, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in association with Sjögren’s syndrome: more than a simple coincidence. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):14-16. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164526

- Zhang M, Zhang L, Rosman IS, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia demographics: a survey of 29 patients. Cutis. 2019;103:E16-E22.

- MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955-961. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.038

- Starace M, Brandi N, Alessandrini A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case series of 65 patients seen in a single Italian centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:433-438. doi:10.1111/jdv.15372

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439-442. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11146.x

- Petrof G, Cuell A, Rajkomar VV, et al. Retrospective review of 18 British South Asian women with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:490-491. doi:10.1111/ijd.13929

- Mervis JS, Borda LJ, Miteva M. Facial and extrafacial lesions in an ethnically diverse series of 91 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia followed at a single center. Dermatology. 2019;235:112-119. doi:10.1159/000494603

- Valesky EM, Maier MD, Kippenberger S, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia - review of recent case reports and case series in PubMed. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. Aug 2018;16:992-999. doi:10.1111/ddg.13601

- Adotama P, Callender V, Kolla A, et al. Comparing the clinical differences in white and black women with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1074-1076. doi:10.1111/bjd.20605

- Miao YJ, Jing J, Du XF, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of disease pathogenesis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:911944. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.911944

- Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387-1390. doi:10.1111/bjd.14722

- Berliner JG, McCalmont TH, Price VH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E26-E27. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.031

- Romiti R, Biancardi Gavioli CF, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings of frontal fibrosing alopecia-associated lichen planus pigmentosus. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:59-63. doi:10.1159/000456038

- Mulinari-Brenner FA, Guilherme MR, Peretti MC, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: diagnosis and therapeutic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 suppl 1):79-81. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175833

- Panchaprateep R, Ruxrungtham P, Chancheewa B, et al. Clinical characteristics, trichoscopy, histopathology and treatment outcomes of frontal fibrosing alopecia in an Asian population: a retro-prospective cohort study. J Dermatol. 2020;47:1301-1311. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15517

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in postmenopausal women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:55-60. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.014

- Rokni GR, Emadi SN, Dabbaghzade A, et al. Evaluating the combined efficacy of oral isotretinoin and topical tacrolimus versus oral finasteride and topical tacrolimus in frontal fibrosing alopecia—a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:613-619. doi:10.1111/jocd.15232

- Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59-66. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8

- Miteva M, Whiting D, Harries M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in black patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:208-210. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10809.x