User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Product News: 04 2017

Cutanea Life Sciences, Inc, launches Aktipak (erythromycin 3% and benzoyl peroxide 5%) Gel, a prescription combination therapy indicated for acne vulgaris. Aktipak is packaged in a pocket-sized, dual-chamber pouch that contains erythromycin and benzoyl peroxide in separate chambers to enable convenient on-the-go use. Immediately prior to use, the patient cuts or twists open the pouch, squeezes the 2 gels into the palm of the hand, mixes the gels together, and applies the mix to the area affected by acne. Aktipak has an 18-month shelf life and does not require refrigeration. Results can be seen within 8 weeks. For more information, visit www.aktipak.com.

Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser

Pierre Fabre Group introduces the Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser (4.5% encapsulated benzoyl peroxide [BPO]) with time-released technology to control the delivery of BPO and enhance penetration. The targeted delivery system adheres to the skin and penetrates the lipid layer while releasing the encapsulated BPO once warmed by the skin, providing optimal efficacy to inhibit the growth of acne-causing bacteria with minimal irritation. Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser is dispensed by physicians and can be used with other products in the Glytone acne product line for optimal results. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

Juvéderm Vollure XC

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Juvéderm Vollure XC for correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds such as the nasolabial folds in adults older than 21 years. It utilizes VYCROSS technology, which blends different weights of hyaluronic acid, contributing to the gel’s duration. Long-lasting results have been demonstrated up to 18 months. For more information, visit www.juvederm.com.

Neutrogena Light Therapy Acne Mask

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc presents the Neutrogena Light Therapy Acne Mask, an LED device utilizing red and blue light to treat acne at home. The mask contains 12 blue LED bulbs that kill Propionibacterium acnes bacteria and 9 red LED bulbs to penetrate deep into the skin to calm inflammation. The mask can be used for 10 minutes each night and shuts off automatically. Results have been seen in 1 week for mild to moderate acne. For more information, visit www.neutrogena.com.

3% Retinol Peel ProSystem

NeoStrata Company, Inc, introduces the 3% Retinol Peel ProSystem featuring Retinol Boosting Complex to exfoliate and improve the appearance of fine lines and winkles, help reduce acne, and improve skin laxity, while promoting a bright, even, and clear complexion. This physician-strength peel is applied in the office but is removed at home after 8 hours or overnight. This peel has demonstrated improvement in acne and skin texture as well as diminished pigmentation. For more information, visit www.neostrata.com.

Siliq

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of the Biologics License Application for Siliq (brodalumab) injection. Siliq, an IL-17 inhibitor, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and have failed to respond or have lost response to other systemic therapies. Siliq has a black box warning for patients with a history of suicidal thoughts or behavior and was approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy involving a one-time enrollment for physicians and one-time informed consent for patients. Sales and marketing in the United States will begin in the second half of 2017. For more information, visit www.valeant.com.

Thermi

Thermi, an Almirall company, announces “The Art of Thermi” campaign focusing on 2 Thermi devices: ThermiRF and Thermi250. ThermiRF is temperature-controlled radiofrequency technology that uses heat to produce aesthetic outcomes for soft tissue applications. Thermi250 is a high-powered, temperature-controlled radiofrequency system emitting at 470 kHz designed with a user-friendly interface to offer versatility for targeting cellulite. For more information, visit www.thermi.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Cutanea Life Sciences, Inc, launches Aktipak (erythromycin 3% and benzoyl peroxide 5%) Gel, a prescription combination therapy indicated for acne vulgaris. Aktipak is packaged in a pocket-sized, dual-chamber pouch that contains erythromycin and benzoyl peroxide in separate chambers to enable convenient on-the-go use. Immediately prior to use, the patient cuts or twists open the pouch, squeezes the 2 gels into the palm of the hand, mixes the gels together, and applies the mix to the area affected by acne. Aktipak has an 18-month shelf life and does not require refrigeration. Results can be seen within 8 weeks. For more information, visit www.aktipak.com.

Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser

Pierre Fabre Group introduces the Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser (4.5% encapsulated benzoyl peroxide [BPO]) with time-released technology to control the delivery of BPO and enhance penetration. The targeted delivery system adheres to the skin and penetrates the lipid layer while releasing the encapsulated BPO once warmed by the skin, providing optimal efficacy to inhibit the growth of acne-causing bacteria with minimal irritation. Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser is dispensed by physicians and can be used with other products in the Glytone acne product line for optimal results. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

Juvéderm Vollure XC

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Juvéderm Vollure XC for correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds such as the nasolabial folds in adults older than 21 years. It utilizes VYCROSS technology, which blends different weights of hyaluronic acid, contributing to the gel’s duration. Long-lasting results have been demonstrated up to 18 months. For more information, visit www.juvederm.com.

Neutrogena Light Therapy Acne Mask

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc presents the Neutrogena Light Therapy Acne Mask, an LED device utilizing red and blue light to treat acne at home. The mask contains 12 blue LED bulbs that kill Propionibacterium acnes bacteria and 9 red LED bulbs to penetrate deep into the skin to calm inflammation. The mask can be used for 10 minutes each night and shuts off automatically. Results have been seen in 1 week for mild to moderate acne. For more information, visit www.neutrogena.com.

3% Retinol Peel ProSystem

NeoStrata Company, Inc, introduces the 3% Retinol Peel ProSystem featuring Retinol Boosting Complex to exfoliate and improve the appearance of fine lines and winkles, help reduce acne, and improve skin laxity, while promoting a bright, even, and clear complexion. This physician-strength peel is applied in the office but is removed at home after 8 hours or overnight. This peel has demonstrated improvement in acne and skin texture as well as diminished pigmentation. For more information, visit www.neostrata.com.

Siliq

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of the Biologics License Application for Siliq (brodalumab) injection. Siliq, an IL-17 inhibitor, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and have failed to respond or have lost response to other systemic therapies. Siliq has a black box warning for patients with a history of suicidal thoughts or behavior and was approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy involving a one-time enrollment for physicians and one-time informed consent for patients. Sales and marketing in the United States will begin in the second half of 2017. For more information, visit www.valeant.com.

Thermi

Thermi, an Almirall company, announces “The Art of Thermi” campaign focusing on 2 Thermi devices: ThermiRF and Thermi250. ThermiRF is temperature-controlled radiofrequency technology that uses heat to produce aesthetic outcomes for soft tissue applications. Thermi250 is a high-powered, temperature-controlled radiofrequency system emitting at 470 kHz designed with a user-friendly interface to offer versatility for targeting cellulite. For more information, visit www.thermi.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Cutanea Life Sciences, Inc, launches Aktipak (erythromycin 3% and benzoyl peroxide 5%) Gel, a prescription combination therapy indicated for acne vulgaris. Aktipak is packaged in a pocket-sized, dual-chamber pouch that contains erythromycin and benzoyl peroxide in separate chambers to enable convenient on-the-go use. Immediately prior to use, the patient cuts or twists open the pouch, squeezes the 2 gels into the palm of the hand, mixes the gels together, and applies the mix to the area affected by acne. Aktipak has an 18-month shelf life and does not require refrigeration. Results can be seen within 8 weeks. For more information, visit www.aktipak.com.

Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser

Pierre Fabre Group introduces the Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser (4.5% encapsulated benzoyl peroxide [BPO]) with time-released technology to control the delivery of BPO and enhance penetration. The targeted delivery system adheres to the skin and penetrates the lipid layer while releasing the encapsulated BPO once warmed by the skin, providing optimal efficacy to inhibit the growth of acne-causing bacteria with minimal irritation. Glytone Acne BPO Clearing Cleanser is dispensed by physicians and can be used with other products in the Glytone acne product line for optimal results. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

Juvéderm Vollure XC

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Juvéderm Vollure XC for correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds such as the nasolabial folds in adults older than 21 years. It utilizes VYCROSS technology, which blends different weights of hyaluronic acid, contributing to the gel’s duration. Long-lasting results have been demonstrated up to 18 months. For more information, visit www.juvederm.com.

Neutrogena Light Therapy Acne Mask

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc presents the Neutrogena Light Therapy Acne Mask, an LED device utilizing red and blue light to treat acne at home. The mask contains 12 blue LED bulbs that kill Propionibacterium acnes bacteria and 9 red LED bulbs to penetrate deep into the skin to calm inflammation. The mask can be used for 10 minutes each night and shuts off automatically. Results have been seen in 1 week for mild to moderate acne. For more information, visit www.neutrogena.com.

3% Retinol Peel ProSystem

NeoStrata Company, Inc, introduces the 3% Retinol Peel ProSystem featuring Retinol Boosting Complex to exfoliate and improve the appearance of fine lines and winkles, help reduce acne, and improve skin laxity, while promoting a bright, even, and clear complexion. This physician-strength peel is applied in the office but is removed at home after 8 hours or overnight. This peel has demonstrated improvement in acne and skin texture as well as diminished pigmentation. For more information, visit www.neostrata.com.

Siliq

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of the Biologics License Application for Siliq (brodalumab) injection. Siliq, an IL-17 inhibitor, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and have failed to respond or have lost response to other systemic therapies. Siliq has a black box warning for patients with a history of suicidal thoughts or behavior and was approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy involving a one-time enrollment for physicians and one-time informed consent for patients. Sales and marketing in the United States will begin in the second half of 2017. For more information, visit www.valeant.com.

Thermi

Thermi, an Almirall company, announces “The Art of Thermi” campaign focusing on 2 Thermi devices: ThermiRF and Thermi250. ThermiRF is temperature-controlled radiofrequency technology that uses heat to produce aesthetic outcomes for soft tissue applications. Thermi250 is a high-powered, temperature-controlled radiofrequency system emitting at 470 kHz designed with a user-friendly interface to offer versatility for targeting cellulite. For more information, visit www.thermi.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Psoriasis on the Hands and Feet: How Patients Should Care for These Areas

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Patients with this condition need to avoid friction and excessive moisture. They should be counseled to use gloves for excessive wet work. I recommend they use cotton gloves on the hands, and then cover those with rubber gloves. Patients should use a hand emollient regularly, including after each time they wash their hands or have exposure to water. If the patient lifts weights, I recommend he/she use weight-lifting gloves to reduce friction.

What are your go to treatments? What are the side effects?

The first line of therapy for hand and foot psoriasis is a topical agent. I most often use a combination of topical steroids and a topical vitamin D analogue. If insurance is amenable, I may use a fixed combination of topical steroid and vitamin D analogue.

If topical therapies are not successful, I often consider using excimer laser therapy, which requires the patient to come to the office twice weekly, so it is important to determine if this therapy is compatible with the patient's schedule. Other options include oral and biological therapies. Apremilast is a reasonable first-line systemic therapy given that it is an oral therapy, requires no laboratory monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile. Alternatively, biologic agents can be utilized. There are several analyses available looking at the efficacy of different biologics in hand and foot psoriasis, but at this point there is no consensus first choice for a biologic in this condition. Many available biologics may have a notable impact though.

The side effects of therapies for psoriasis are well established. Topical therapies and excimer laser are relatively safe choices. Apremilast has been associated with early gastrointestinal tract side effects that tend to resolve over time. Each biologic has a unique safety profile, with a rare incidence of side effects that should be reviewed carefully with any prospective patients before starting therapy.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

It is important to reinforce gentle hand care and foot care. Patients need to understand that lack of compliance with treatment will lead to recurrence of disease.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

I try to educate them as best as possible, and ask them to return and reconsider therapy if they find that this condition affects their quality of life.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Patients with this condition need to avoid friction and excessive moisture. They should be counseled to use gloves for excessive wet work. I recommend they use cotton gloves on the hands, and then cover those with rubber gloves. Patients should use a hand emollient regularly, including after each time they wash their hands or have exposure to water. If the patient lifts weights, I recommend he/she use weight-lifting gloves to reduce friction.

What are your go to treatments? What are the side effects?

The first line of therapy for hand and foot psoriasis is a topical agent. I most often use a combination of topical steroids and a topical vitamin D analogue. If insurance is amenable, I may use a fixed combination of topical steroid and vitamin D analogue.

If topical therapies are not successful, I often consider using excimer laser therapy, which requires the patient to come to the office twice weekly, so it is important to determine if this therapy is compatible with the patient's schedule. Other options include oral and biological therapies. Apremilast is a reasonable first-line systemic therapy given that it is an oral therapy, requires no laboratory monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile. Alternatively, biologic agents can be utilized. There are several analyses available looking at the efficacy of different biologics in hand and foot psoriasis, but at this point there is no consensus first choice for a biologic in this condition. Many available biologics may have a notable impact though.

The side effects of therapies for psoriasis are well established. Topical therapies and excimer laser are relatively safe choices. Apremilast has been associated with early gastrointestinal tract side effects that tend to resolve over time. Each biologic has a unique safety profile, with a rare incidence of side effects that should be reviewed carefully with any prospective patients before starting therapy.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

It is important to reinforce gentle hand care and foot care. Patients need to understand that lack of compliance with treatment will lead to recurrence of disease.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

I try to educate them as best as possible, and ask them to return and reconsider therapy if they find that this condition affects their quality of life.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Patients with this condition need to avoid friction and excessive moisture. They should be counseled to use gloves for excessive wet work. I recommend they use cotton gloves on the hands, and then cover those with rubber gloves. Patients should use a hand emollient regularly, including after each time they wash their hands or have exposure to water. If the patient lifts weights, I recommend he/she use weight-lifting gloves to reduce friction.

What are your go to treatments? What are the side effects?

The first line of therapy for hand and foot psoriasis is a topical agent. I most often use a combination of topical steroids and a topical vitamin D analogue. If insurance is amenable, I may use a fixed combination of topical steroid and vitamin D analogue.

If topical therapies are not successful, I often consider using excimer laser therapy, which requires the patient to come to the office twice weekly, so it is important to determine if this therapy is compatible with the patient's schedule. Other options include oral and biological therapies. Apremilast is a reasonable first-line systemic therapy given that it is an oral therapy, requires no laboratory monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile. Alternatively, biologic agents can be utilized. There are several analyses available looking at the efficacy of different biologics in hand and foot psoriasis, but at this point there is no consensus first choice for a biologic in this condition. Many available biologics may have a notable impact though.

The side effects of therapies for psoriasis are well established. Topical therapies and excimer laser are relatively safe choices. Apremilast has been associated with early gastrointestinal tract side effects that tend to resolve over time. Each biologic has a unique safety profile, with a rare incidence of side effects that should be reviewed carefully with any prospective patients before starting therapy.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

It is important to reinforce gentle hand care and foot care. Patients need to understand that lack of compliance with treatment will lead to recurrence of disease.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

I try to educate them as best as possible, and ask them to return and reconsider therapy if they find that this condition affects their quality of life.

Microneedling Therapy With and Without Platelet-Rich Plasma

Microneedling therapy, also known as collagen induction therapy or percutaneous collagen induction, is an increasingly popular treatment modality for skin rejuvenation. The approach employs small needles to puncture the skin and stimulate local collagen production in a minimally invasive manner. Recently, clinicians have incorporated the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) with the aim of augmenting cosmetic outcomes. In this article, we examine the utility of this approach by reviewing comparison studies of microneedling therapy with and without the application of PRP.

Dr. Gary Goldenberg demonstrates microneedling with platelet-rich plasma in a procedural video available here.

Microneedling Therapy

The use of microneedling first gained attention in the 1990s. Initially, Camirand and Doucet1 described tattooing without pigment for the treatment of achromatic and hypertrophic scars. Fernandes2 evolved this concept and developed a drum-shaped device with fine protruding needles to puncture the skin. Microneedling devices have expanded in recent years and now include both cord- and battery-powered pens and rollers, with needles ranging in length from 0.25 to 3.0 mm.

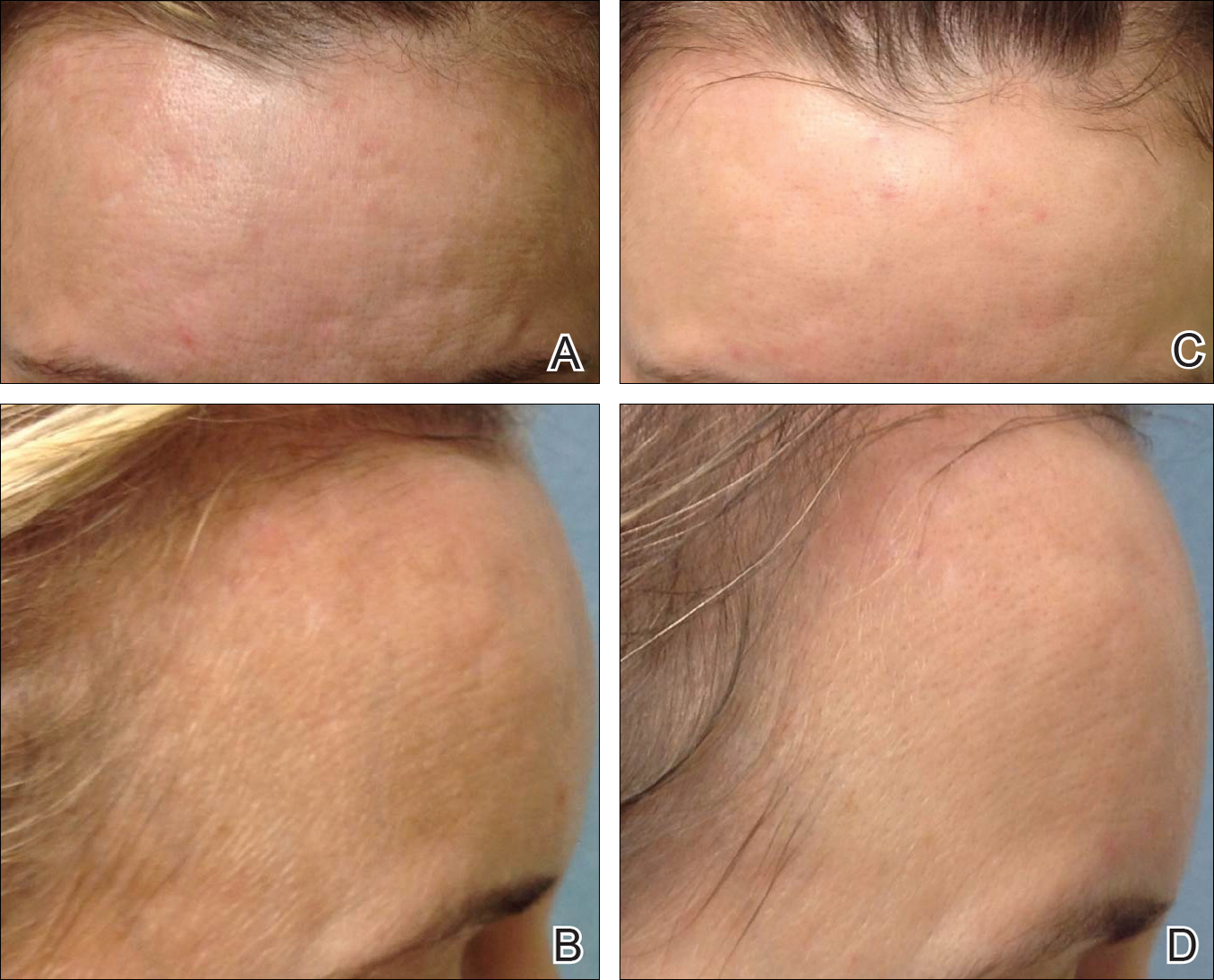

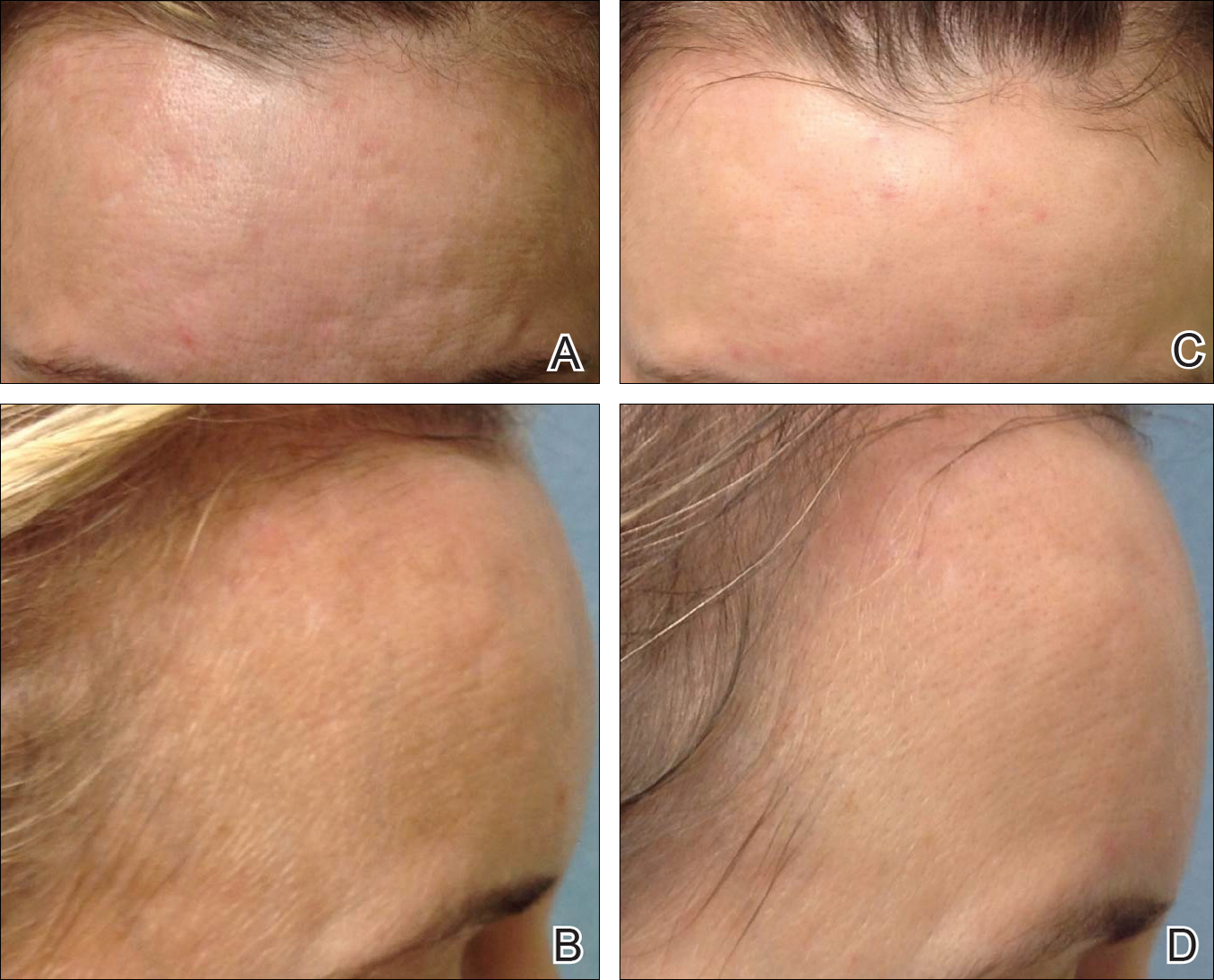

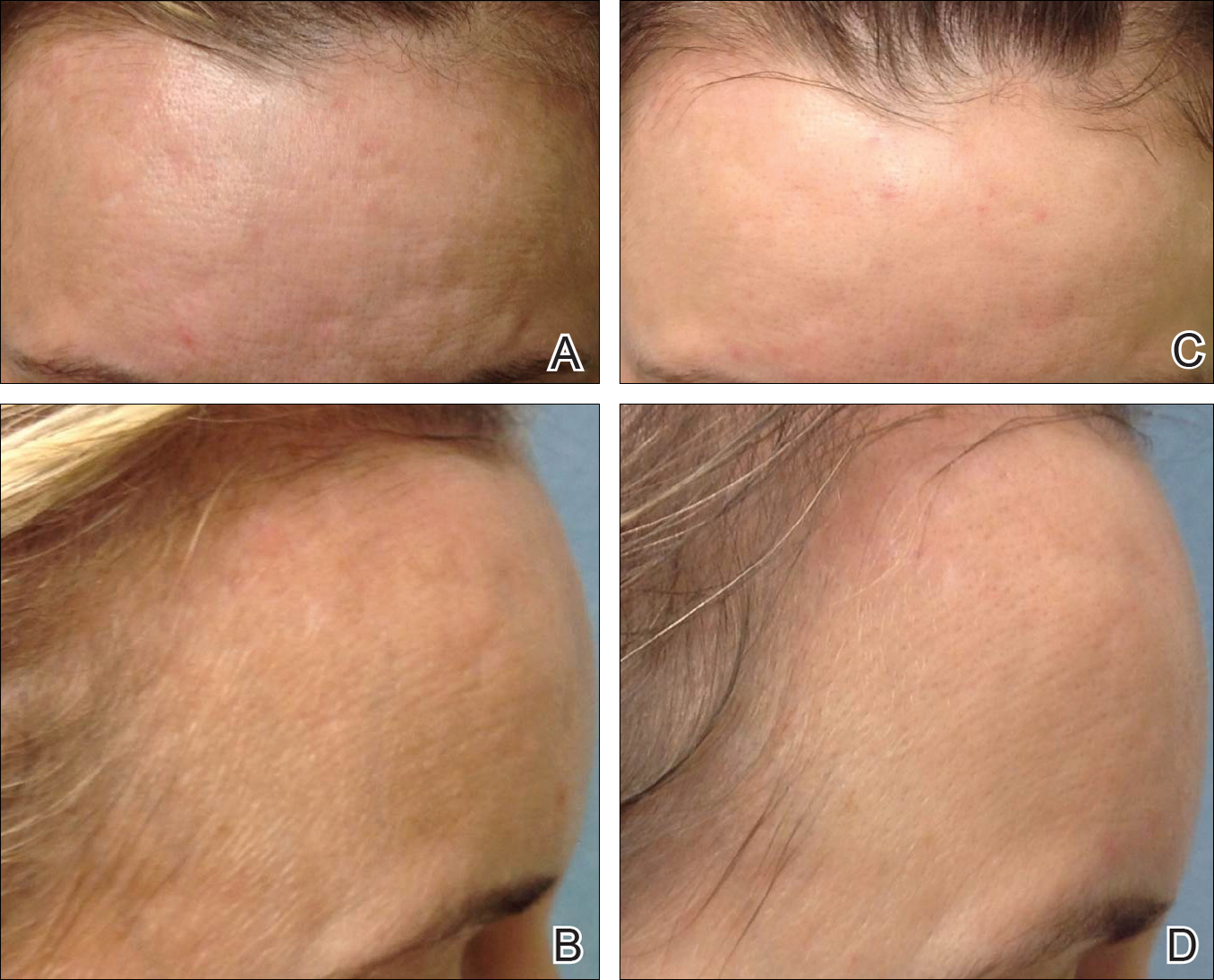

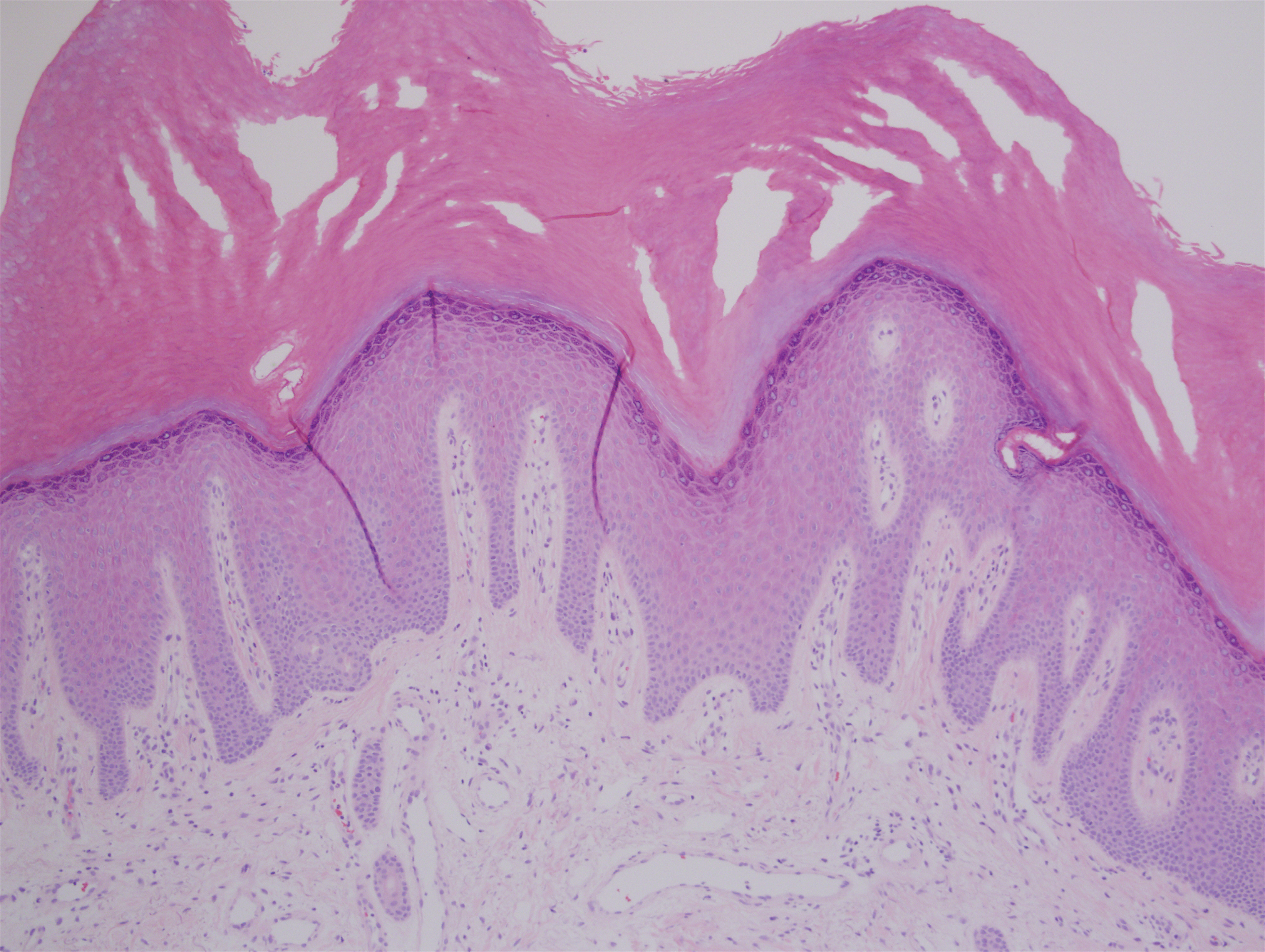

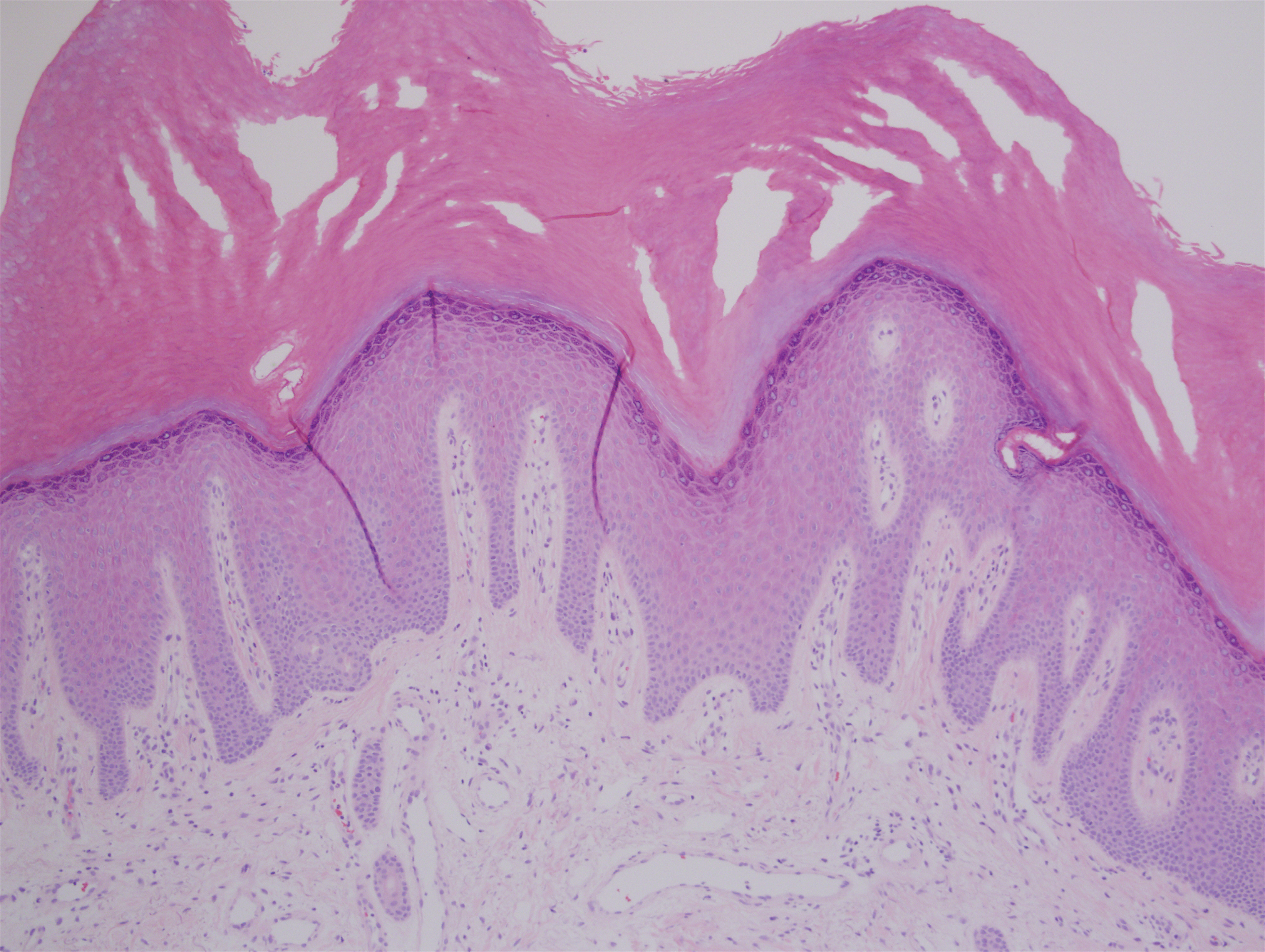

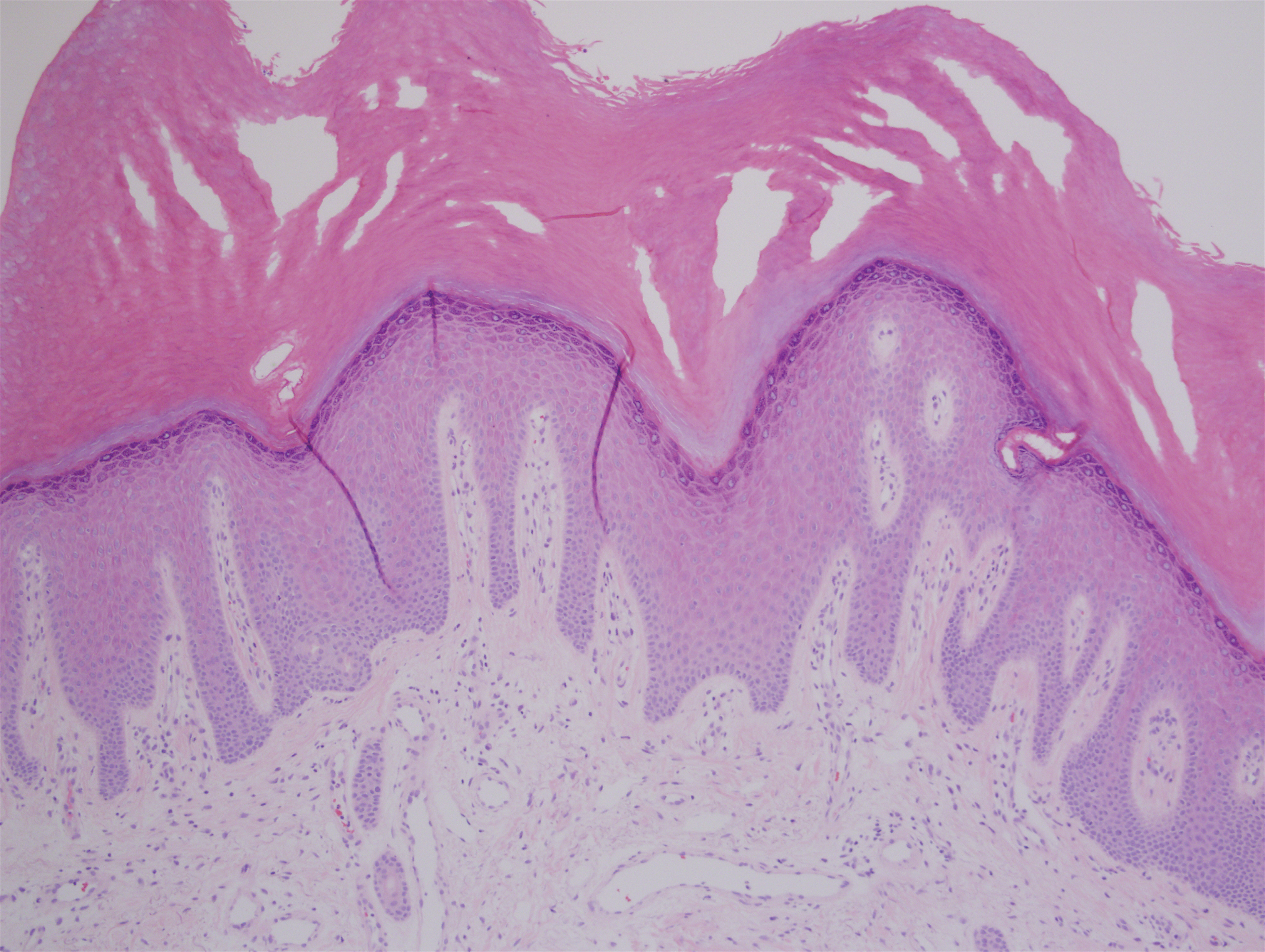

Treatment with microneedling promotes skin rejuvenation by creating small puncture wounds in the epidermis and dermis. This injury triggers the wound healing cascade and alters the modulation of growth factors to promote regenerative effects.3,4 Following microneedling therapy, increases occur in elastic fiber formation, collagen deposition, and dermal thickness (Figure).5 Of interesting histologic note, collagen is deposited in the normal lattice pattern following this treatment rather than in the parallel bundles typical of scars.6 Microneedling preserves the overall integrity of the epidermal layers and basement membrane, allowing the epidermis to heal without abnormality, verified on histology by a normal stratum corneum, enhanced stratum granulosum, and normal rete ridges.7

Microneedling has demonstrated several uses beyond general skin rejuvenation. In patients with atrophic acne scars, therapy can lead to improved scar appearance, skin texture, and patient satisfaction.8,9 Hypertrophic and dyspigmented burn scars on the body, face, arms, and legs have shown to be receptive to repeated treatments.10 Microneedling also has shown promise in treating androgenic alopecia, increasing hair regrowth in patients who previously showed poor response to conventional therapy with minoxidil and finasteride.11,12

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Platelet-rich plasma is developed by enriching blood with an autologous concentration of platelets. The preparation of PRP begins with whole blood, commonly obtained peripherally by venipuncture. Samples undergo centrifugation to allow separation of the blood into 3 layers: platelet-poor plasma, PRP, and erythrocytes.13 The typical platelet count of whole blood is approximately 200,000/µL; PRP aims to prepare a platelet count of at least 1,000,000/µL in a 5-mL volume.14

An attractive component of PRP is its high concentration of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and epithelial growth factor.15 Because of the regenerative effects of these proteins, PRP has been investigated as a modality to augment wound healing in a variety of clinical areas, such as maxillofacial surgery, orthopedics, cardiovascular surgery, and treatment of soft tissue ulcers.16

Combination Use of Microneedling and PRP

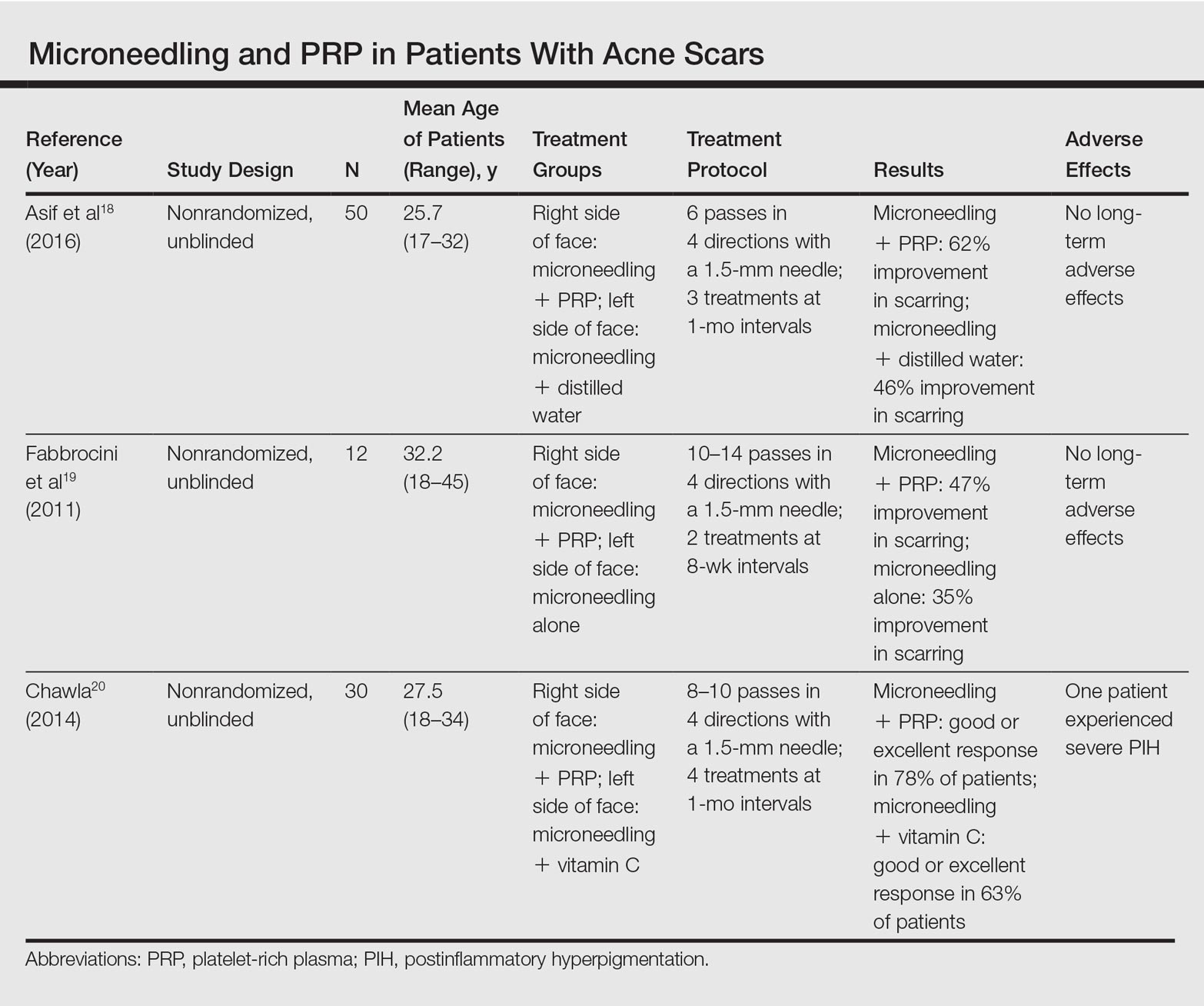

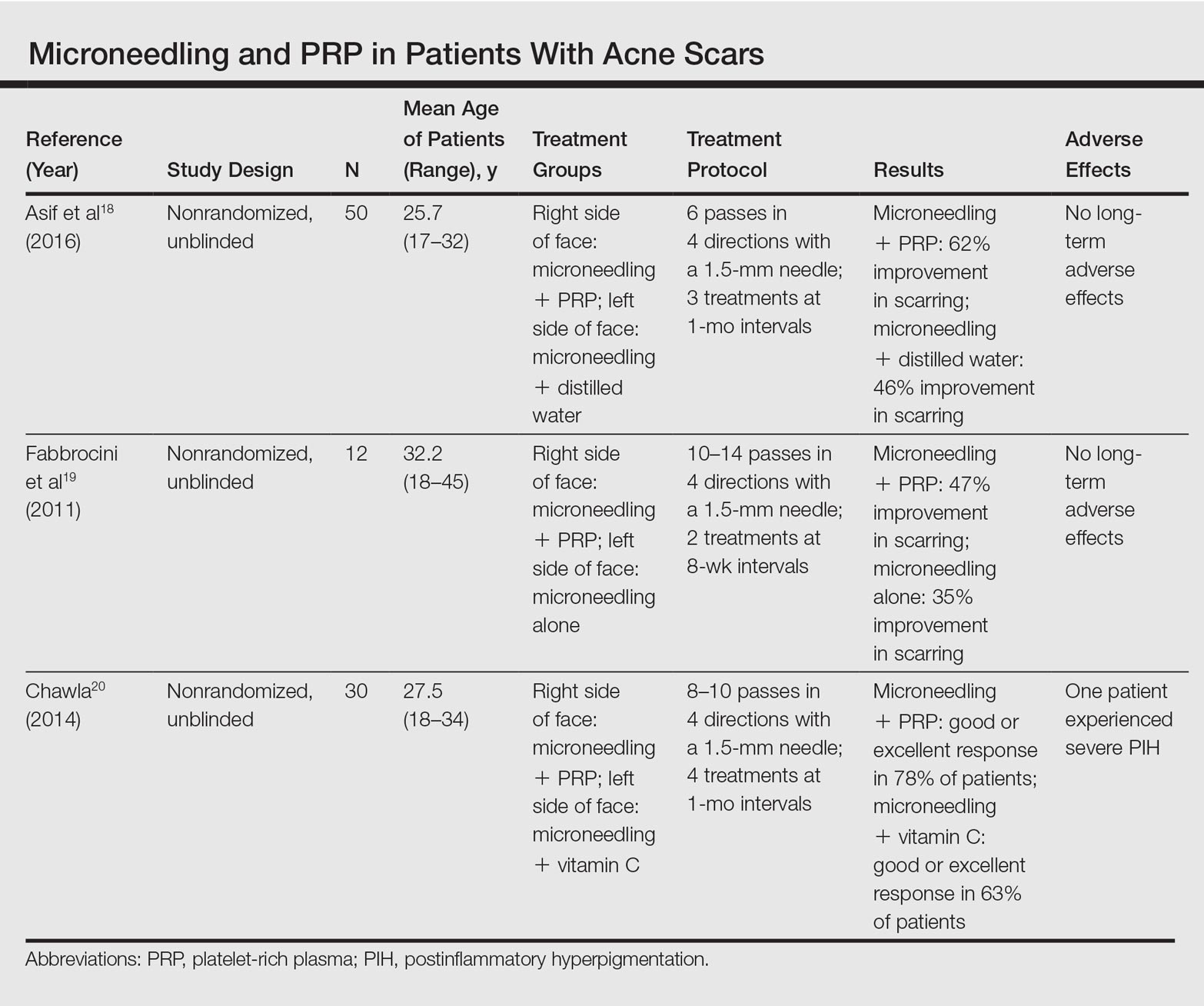

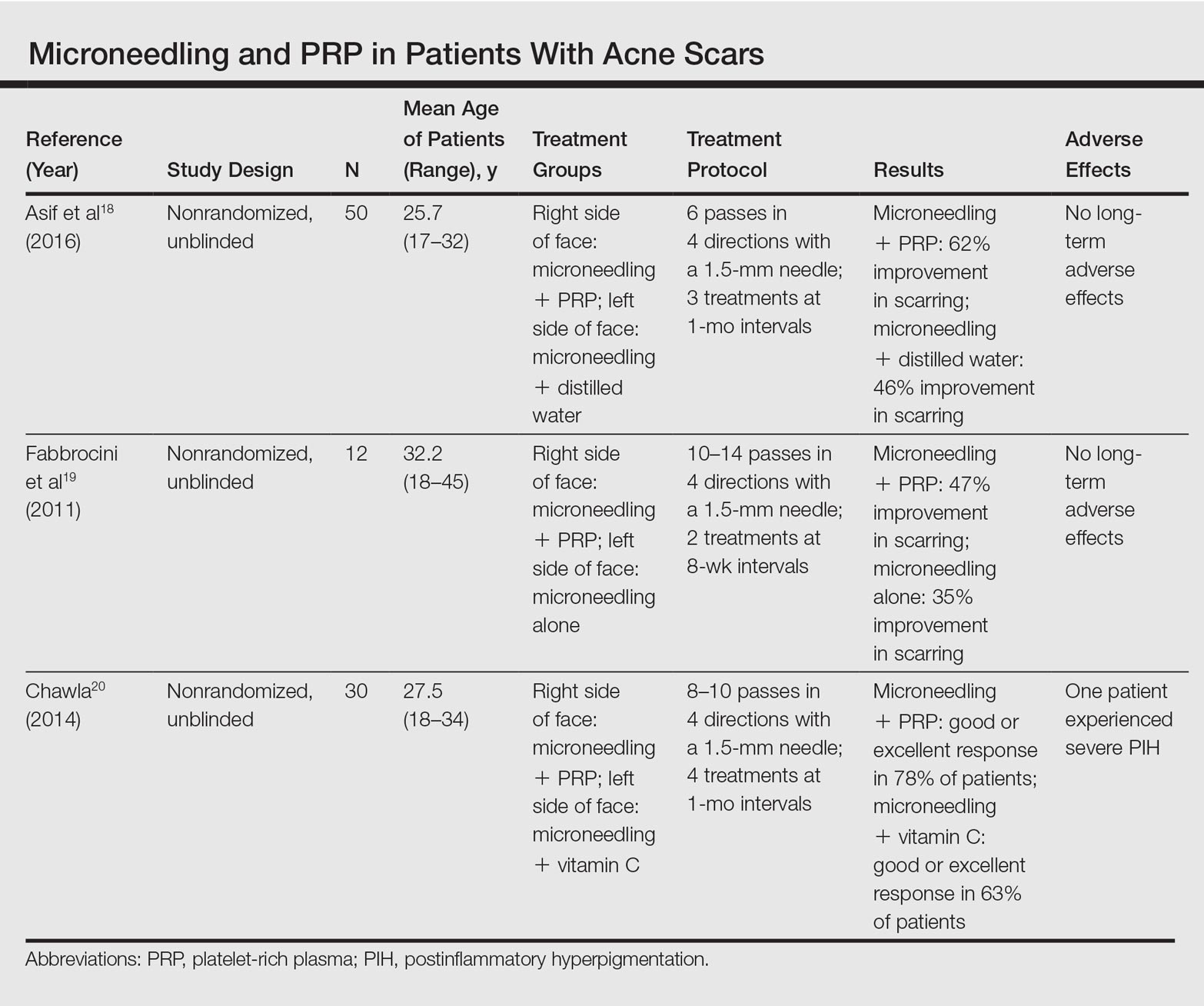

Several studies have compared the effects of microneedling with and without the application of PRP (Table).17-20 In an animal model, Akcal et al17 examined the effects of microneedling and PRP on skin flap survival. Eight rats were randomly divided into 5 groups: sham, control, microneedling alone, microneedling plus PRP, and microneedling plus platelet-poor plasma. Treatments were applied to skin flaps after 4 hours of induced ischemia. The surviving flap area was measured, with results demonstrating significantly higher viable areas in the microneedling plus PRP group relative to all other groups (P<.01). On histologic examination, the microneedling plus PRP group showed well-organized epidermal layers and a dermal integrity that matched the dermis of the sham group.17

Asif et al18 performed a split-face comparison study of 50 patients with atrophic acne scars. On the right side, microneedling was performed followed by intradermal injections and topical application of PRP. On the left side, microneedling was performed followed by intradermal injections of distilled water. The study included 3 treatment sessions with 1 month between each session. Scars were assessed using the Goodman and Baron scale,21 which is designed to grade the morphology of postacne scarring. Scars on the right side improved by 62.2% and scars on the left side improved by 45.8%; prior to treatment, both sides demonstrated similar severity scores, but final severity scores were significantly reduced in the microneedling plus PRP group relative to the microneedling plus distilled water group (P<.00001). No residual side effects from treatment were reported.18

Examining the degree of improvement more carefully, microneedling plus PRP yielded excellent improvement in 40% (20/50) of patients and good improvement in 60% (30/50).18 Microneedling plus distilled water led to excellent improvement in 10% (5/50) and good improvement in 84% (42/50). Given that microneedling plus distilled water still provided good to excellent results in 94% of patients, the addition of PRP was helpful though not necessary in achieving meaningful benefit.18

In another split-face study, Fabbrocini et al19 evaluated 12 adult patients with acne scars. The right side of the face received microneedling plus PRP, while the left side received microneedling alone. Two treatments were performed 8 weeks apart. Severity scores (0=no lesions; 10=maximum severity) were used to assess patient outcomes throughout the study. Acne scars improved on both sides of the face following the treatment period, but the reduction in scar severity with microneedling plus PRP (3.5 points) was significantly greater than with microneedling alone (2.6 points)(P<.05). Patients tended to experience2 to 3 days of mild swelling and erythema after treatment regardless of PRP addition. With only 12 patients, the study was limited by a small sample size. The 10-point grading system differed from the Goodman and Baron scale in that it lacked corresponding qualitative markers, likely decreasing reproducibility.19

Chawla20 compared the effectiveness of combination therapy with microneedling plus PRP versus microneedling and vitamin C application. In a split-face study of 30 patients with atrophic acne scars, the right side of the face was treated with microneedling plus PRP and the left side was treated with microneedling plus vitamin C. Four sessions were performed with an interval of 1 month in between treatments. The Goodman and Baron Scale was used to assess treatment efficacy. Overall, both treatments led to improved outcomes, but in categorizing patients who demonstrated poor responses, a significantly larger percentage existed in the microneedling plus vitamin C group (37% [10/27]) versus the microneedling plus PRP group (22% [6/27])(P=.021). Additionally, aggregate patient satisfaction scores were higher with microneedling plus PRP relative to microneedling plus vitamin C (P=.01). Of note, assessments of improvement were performed by the treating physician and patient satisfaction reports were completed with knowledge of the therapies and cost factor, which may have influenced results.20

Conclusion

Microneedling therapy continues to evolve with a range of applications now emerging in dermatology. As PRP has gained popularity, there has been increased interest in its utilization to amplify the regenerative effects of microneedling. Although the number of direct comparisons examining microneedling with and without PRP is limited, the available evidence indicates that the addition of PRP may improve cosmetic outcomes. These results have been demonstrated primarily in the management of acne scars, but favorable effects may extend to other indications. Continued study is warranted to further quantify the degree of these benefits and to elucidate optimal treatment schedules.

In addition, it is important to consider a cost-benefit analysis of PRP. The price of PRP varies depending on the clinical site but in certain cases may double the cost of a microneedling treatment session. Although studies have demonstrated a statistically significant benefit to PRP, the clinical significance of this supplementary treatment must be weighed against the increased expense. A discussion should take place with the consideration that microneedling alone can provide a satisfactory result for some patients.

- Camirand A, Doucet J. Needle dermabrasion. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:48-51.

- Fernandes D. Percutaneous collagen induction: an alternative to laser resurfacing. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22:307-309.

- Fabbrocini G, Fardella N, Monfrecola A, et al. Acne scarring treatment using skin needling. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:874-879.

- Zeitter S, Sikora Z, Jahn S, et al. Microneedling: matching the results of medical needling and repetitive treatments to maximize potential for skin regeneration [published online February 7, 2014]. Burns. 2014;40:966-973.

- Schwarz M, Laaff H. A prospective controlled assessment of microneedling with the Dermaroller device. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:E146-E148.

- Fernandes D, Signorini M. Combating photoaging with percutaneous collagen induction. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:192-199.

- Aust MC, Fernandes D, Kolokythas P, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for scars, wrinkles, and skin laxity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1421-1429.

- El-Domyati M, Barakat M, Awad S, et al. Microneedling therapy for atrophic acne scars: an objective evaluation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-42.

- Leheta T, El Tawdy A, Abdel Hay R, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction versus full-concentration trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:207-216.

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843.

- Dhurat R, Mathapati S. Response to microneedling treatment in men with androgenetic alopecia who failed to respond to conventional therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:260-263.

- Dhurat R, Sukesh M, Avhad G, et al. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:6-11.

- Wang HL, Avila G. Platelet rich plasma: myth or reality? Eur J Dent. 2007;1:192-194.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10:225-228.

- Lubkowska A, Dolegowska B, Banfi G. Growth factor content in PRP and their applicability in medicine. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26(2 suppl 1):3S-22S.

- Pietrzak WS, Eppley BL. Platelet rich plasma: biology and new technology. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:1043-1054.

- Akcal A, Savas SA, Gorgulu T, et al. The effect of platelete rich plasma combined with microneedling on full venous outflow compromise in a rat skin flap model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(4 suppl):71-72.

- Asif M, Kanodia S, Singh K. Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling verses microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a concurrent split-face study [published online January 8, 2016]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:434-443.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Combined use of skin needling and platelet-rich plasma in acne scarring treatment. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:177-183.

- Chawla S. Split face comparative study of microneedling with PRP versus microneedling with vitamin C in treating atrophic post acne scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:209-212.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458-1466.

Microneedling therapy, also known as collagen induction therapy or percutaneous collagen induction, is an increasingly popular treatment modality for skin rejuvenation. The approach employs small needles to puncture the skin and stimulate local collagen production in a minimally invasive manner. Recently, clinicians have incorporated the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) with the aim of augmenting cosmetic outcomes. In this article, we examine the utility of this approach by reviewing comparison studies of microneedling therapy with and without the application of PRP.

Dr. Gary Goldenberg demonstrates microneedling with platelet-rich plasma in a procedural video available here.

Microneedling Therapy

The use of microneedling first gained attention in the 1990s. Initially, Camirand and Doucet1 described tattooing without pigment for the treatment of achromatic and hypertrophic scars. Fernandes2 evolved this concept and developed a drum-shaped device with fine protruding needles to puncture the skin. Microneedling devices have expanded in recent years and now include both cord- and battery-powered pens and rollers, with needles ranging in length from 0.25 to 3.0 mm.

Treatment with microneedling promotes skin rejuvenation by creating small puncture wounds in the epidermis and dermis. This injury triggers the wound healing cascade and alters the modulation of growth factors to promote regenerative effects.3,4 Following microneedling therapy, increases occur in elastic fiber formation, collagen deposition, and dermal thickness (Figure).5 Of interesting histologic note, collagen is deposited in the normal lattice pattern following this treatment rather than in the parallel bundles typical of scars.6 Microneedling preserves the overall integrity of the epidermal layers and basement membrane, allowing the epidermis to heal without abnormality, verified on histology by a normal stratum corneum, enhanced stratum granulosum, and normal rete ridges.7

Microneedling has demonstrated several uses beyond general skin rejuvenation. In patients with atrophic acne scars, therapy can lead to improved scar appearance, skin texture, and patient satisfaction.8,9 Hypertrophic and dyspigmented burn scars on the body, face, arms, and legs have shown to be receptive to repeated treatments.10 Microneedling also has shown promise in treating androgenic alopecia, increasing hair regrowth in patients who previously showed poor response to conventional therapy with minoxidil and finasteride.11,12

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Platelet-rich plasma is developed by enriching blood with an autologous concentration of platelets. The preparation of PRP begins with whole blood, commonly obtained peripherally by venipuncture. Samples undergo centrifugation to allow separation of the blood into 3 layers: platelet-poor plasma, PRP, and erythrocytes.13 The typical platelet count of whole blood is approximately 200,000/µL; PRP aims to prepare a platelet count of at least 1,000,000/µL in a 5-mL volume.14

An attractive component of PRP is its high concentration of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and epithelial growth factor.15 Because of the regenerative effects of these proteins, PRP has been investigated as a modality to augment wound healing in a variety of clinical areas, such as maxillofacial surgery, orthopedics, cardiovascular surgery, and treatment of soft tissue ulcers.16

Combination Use of Microneedling and PRP

Several studies have compared the effects of microneedling with and without the application of PRP (Table).17-20 In an animal model, Akcal et al17 examined the effects of microneedling and PRP on skin flap survival. Eight rats were randomly divided into 5 groups: sham, control, microneedling alone, microneedling plus PRP, and microneedling plus platelet-poor plasma. Treatments were applied to skin flaps after 4 hours of induced ischemia. The surviving flap area was measured, with results demonstrating significantly higher viable areas in the microneedling plus PRP group relative to all other groups (P<.01). On histologic examination, the microneedling plus PRP group showed well-organized epidermal layers and a dermal integrity that matched the dermis of the sham group.17

Asif et al18 performed a split-face comparison study of 50 patients with atrophic acne scars. On the right side, microneedling was performed followed by intradermal injections and topical application of PRP. On the left side, microneedling was performed followed by intradermal injections of distilled water. The study included 3 treatment sessions with 1 month between each session. Scars were assessed using the Goodman and Baron scale,21 which is designed to grade the morphology of postacne scarring. Scars on the right side improved by 62.2% and scars on the left side improved by 45.8%; prior to treatment, both sides demonstrated similar severity scores, but final severity scores were significantly reduced in the microneedling plus PRP group relative to the microneedling plus distilled water group (P<.00001). No residual side effects from treatment were reported.18

Examining the degree of improvement more carefully, microneedling plus PRP yielded excellent improvement in 40% (20/50) of patients and good improvement in 60% (30/50).18 Microneedling plus distilled water led to excellent improvement in 10% (5/50) and good improvement in 84% (42/50). Given that microneedling plus distilled water still provided good to excellent results in 94% of patients, the addition of PRP was helpful though not necessary in achieving meaningful benefit.18

In another split-face study, Fabbrocini et al19 evaluated 12 adult patients with acne scars. The right side of the face received microneedling plus PRP, while the left side received microneedling alone. Two treatments were performed 8 weeks apart. Severity scores (0=no lesions; 10=maximum severity) were used to assess patient outcomes throughout the study. Acne scars improved on both sides of the face following the treatment period, but the reduction in scar severity with microneedling plus PRP (3.5 points) was significantly greater than with microneedling alone (2.6 points)(P<.05). Patients tended to experience2 to 3 days of mild swelling and erythema after treatment regardless of PRP addition. With only 12 patients, the study was limited by a small sample size. The 10-point grading system differed from the Goodman and Baron scale in that it lacked corresponding qualitative markers, likely decreasing reproducibility.19

Chawla20 compared the effectiveness of combination therapy with microneedling plus PRP versus microneedling and vitamin C application. In a split-face study of 30 patients with atrophic acne scars, the right side of the face was treated with microneedling plus PRP and the left side was treated with microneedling plus vitamin C. Four sessions were performed with an interval of 1 month in between treatments. The Goodman and Baron Scale was used to assess treatment efficacy. Overall, both treatments led to improved outcomes, but in categorizing patients who demonstrated poor responses, a significantly larger percentage existed in the microneedling plus vitamin C group (37% [10/27]) versus the microneedling plus PRP group (22% [6/27])(P=.021). Additionally, aggregate patient satisfaction scores were higher with microneedling plus PRP relative to microneedling plus vitamin C (P=.01). Of note, assessments of improvement were performed by the treating physician and patient satisfaction reports were completed with knowledge of the therapies and cost factor, which may have influenced results.20

Conclusion

Microneedling therapy continues to evolve with a range of applications now emerging in dermatology. As PRP has gained popularity, there has been increased interest in its utilization to amplify the regenerative effects of microneedling. Although the number of direct comparisons examining microneedling with and without PRP is limited, the available evidence indicates that the addition of PRP may improve cosmetic outcomes. These results have been demonstrated primarily in the management of acne scars, but favorable effects may extend to other indications. Continued study is warranted to further quantify the degree of these benefits and to elucidate optimal treatment schedules.

In addition, it is important to consider a cost-benefit analysis of PRP. The price of PRP varies depending on the clinical site but in certain cases may double the cost of a microneedling treatment session. Although studies have demonstrated a statistically significant benefit to PRP, the clinical significance of this supplementary treatment must be weighed against the increased expense. A discussion should take place with the consideration that microneedling alone can provide a satisfactory result for some patients.

Microneedling therapy, also known as collagen induction therapy or percutaneous collagen induction, is an increasingly popular treatment modality for skin rejuvenation. The approach employs small needles to puncture the skin and stimulate local collagen production in a minimally invasive manner. Recently, clinicians have incorporated the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) with the aim of augmenting cosmetic outcomes. In this article, we examine the utility of this approach by reviewing comparison studies of microneedling therapy with and without the application of PRP.

Dr. Gary Goldenberg demonstrates microneedling with platelet-rich plasma in a procedural video available here.

Microneedling Therapy

The use of microneedling first gained attention in the 1990s. Initially, Camirand and Doucet1 described tattooing without pigment for the treatment of achromatic and hypertrophic scars. Fernandes2 evolved this concept and developed a drum-shaped device with fine protruding needles to puncture the skin. Microneedling devices have expanded in recent years and now include both cord- and battery-powered pens and rollers, with needles ranging in length from 0.25 to 3.0 mm.

Treatment with microneedling promotes skin rejuvenation by creating small puncture wounds in the epidermis and dermis. This injury triggers the wound healing cascade and alters the modulation of growth factors to promote regenerative effects.3,4 Following microneedling therapy, increases occur in elastic fiber formation, collagen deposition, and dermal thickness (Figure).5 Of interesting histologic note, collagen is deposited in the normal lattice pattern following this treatment rather than in the parallel bundles typical of scars.6 Microneedling preserves the overall integrity of the epidermal layers and basement membrane, allowing the epidermis to heal without abnormality, verified on histology by a normal stratum corneum, enhanced stratum granulosum, and normal rete ridges.7

Microneedling has demonstrated several uses beyond general skin rejuvenation. In patients with atrophic acne scars, therapy can lead to improved scar appearance, skin texture, and patient satisfaction.8,9 Hypertrophic and dyspigmented burn scars on the body, face, arms, and legs have shown to be receptive to repeated treatments.10 Microneedling also has shown promise in treating androgenic alopecia, increasing hair regrowth in patients who previously showed poor response to conventional therapy with minoxidil and finasteride.11,12

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Platelet-rich plasma is developed by enriching blood with an autologous concentration of platelets. The preparation of PRP begins with whole blood, commonly obtained peripherally by venipuncture. Samples undergo centrifugation to allow separation of the blood into 3 layers: platelet-poor plasma, PRP, and erythrocytes.13 The typical platelet count of whole blood is approximately 200,000/µL; PRP aims to prepare a platelet count of at least 1,000,000/µL in a 5-mL volume.14

An attractive component of PRP is its high concentration of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and epithelial growth factor.15 Because of the regenerative effects of these proteins, PRP has been investigated as a modality to augment wound healing in a variety of clinical areas, such as maxillofacial surgery, orthopedics, cardiovascular surgery, and treatment of soft tissue ulcers.16

Combination Use of Microneedling and PRP

Several studies have compared the effects of microneedling with and without the application of PRP (Table).17-20 In an animal model, Akcal et al17 examined the effects of microneedling and PRP on skin flap survival. Eight rats were randomly divided into 5 groups: sham, control, microneedling alone, microneedling plus PRP, and microneedling plus platelet-poor plasma. Treatments were applied to skin flaps after 4 hours of induced ischemia. The surviving flap area was measured, with results demonstrating significantly higher viable areas in the microneedling plus PRP group relative to all other groups (P<.01). On histologic examination, the microneedling plus PRP group showed well-organized epidermal layers and a dermal integrity that matched the dermis of the sham group.17

Asif et al18 performed a split-face comparison study of 50 patients with atrophic acne scars. On the right side, microneedling was performed followed by intradermal injections and topical application of PRP. On the left side, microneedling was performed followed by intradermal injections of distilled water. The study included 3 treatment sessions with 1 month between each session. Scars were assessed using the Goodman and Baron scale,21 which is designed to grade the morphology of postacne scarring. Scars on the right side improved by 62.2% and scars on the left side improved by 45.8%; prior to treatment, both sides demonstrated similar severity scores, but final severity scores were significantly reduced in the microneedling plus PRP group relative to the microneedling plus distilled water group (P<.00001). No residual side effects from treatment were reported.18

Examining the degree of improvement more carefully, microneedling plus PRP yielded excellent improvement in 40% (20/50) of patients and good improvement in 60% (30/50).18 Microneedling plus distilled water led to excellent improvement in 10% (5/50) and good improvement in 84% (42/50). Given that microneedling plus distilled water still provided good to excellent results in 94% of patients, the addition of PRP was helpful though not necessary in achieving meaningful benefit.18

In another split-face study, Fabbrocini et al19 evaluated 12 adult patients with acne scars. The right side of the face received microneedling plus PRP, while the left side received microneedling alone. Two treatments were performed 8 weeks apart. Severity scores (0=no lesions; 10=maximum severity) were used to assess patient outcomes throughout the study. Acne scars improved on both sides of the face following the treatment period, but the reduction in scar severity with microneedling plus PRP (3.5 points) was significantly greater than with microneedling alone (2.6 points)(P<.05). Patients tended to experience2 to 3 days of mild swelling and erythema after treatment regardless of PRP addition. With only 12 patients, the study was limited by a small sample size. The 10-point grading system differed from the Goodman and Baron scale in that it lacked corresponding qualitative markers, likely decreasing reproducibility.19

Chawla20 compared the effectiveness of combination therapy with microneedling plus PRP versus microneedling and vitamin C application. In a split-face study of 30 patients with atrophic acne scars, the right side of the face was treated with microneedling plus PRP and the left side was treated with microneedling plus vitamin C. Four sessions were performed with an interval of 1 month in between treatments. The Goodman and Baron Scale was used to assess treatment efficacy. Overall, both treatments led to improved outcomes, but in categorizing patients who demonstrated poor responses, a significantly larger percentage existed in the microneedling plus vitamin C group (37% [10/27]) versus the microneedling plus PRP group (22% [6/27])(P=.021). Additionally, aggregate patient satisfaction scores were higher with microneedling plus PRP relative to microneedling plus vitamin C (P=.01). Of note, assessments of improvement were performed by the treating physician and patient satisfaction reports were completed with knowledge of the therapies and cost factor, which may have influenced results.20

Conclusion

Microneedling therapy continues to evolve with a range of applications now emerging in dermatology. As PRP has gained popularity, there has been increased interest in its utilization to amplify the regenerative effects of microneedling. Although the number of direct comparisons examining microneedling with and without PRP is limited, the available evidence indicates that the addition of PRP may improve cosmetic outcomes. These results have been demonstrated primarily in the management of acne scars, but favorable effects may extend to other indications. Continued study is warranted to further quantify the degree of these benefits and to elucidate optimal treatment schedules.

In addition, it is important to consider a cost-benefit analysis of PRP. The price of PRP varies depending on the clinical site but in certain cases may double the cost of a microneedling treatment session. Although studies have demonstrated a statistically significant benefit to PRP, the clinical significance of this supplementary treatment must be weighed against the increased expense. A discussion should take place with the consideration that microneedling alone can provide a satisfactory result for some patients.

- Camirand A, Doucet J. Needle dermabrasion. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:48-51.

- Fernandes D. Percutaneous collagen induction: an alternative to laser resurfacing. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22:307-309.

- Fabbrocini G, Fardella N, Monfrecola A, et al. Acne scarring treatment using skin needling. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:874-879.

- Zeitter S, Sikora Z, Jahn S, et al. Microneedling: matching the results of medical needling and repetitive treatments to maximize potential for skin regeneration [published online February 7, 2014]. Burns. 2014;40:966-973.

- Schwarz M, Laaff H. A prospective controlled assessment of microneedling with the Dermaroller device. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:E146-E148.

- Fernandes D, Signorini M. Combating photoaging with percutaneous collagen induction. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:192-199.

- Aust MC, Fernandes D, Kolokythas P, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for scars, wrinkles, and skin laxity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1421-1429.

- El-Domyati M, Barakat M, Awad S, et al. Microneedling therapy for atrophic acne scars: an objective evaluation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-42.

- Leheta T, El Tawdy A, Abdel Hay R, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction versus full-concentration trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:207-216.

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843.

- Dhurat R, Mathapati S. Response to microneedling treatment in men with androgenetic alopecia who failed to respond to conventional therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:260-263.

- Dhurat R, Sukesh M, Avhad G, et al. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:6-11.

- Wang HL, Avila G. Platelet rich plasma: myth or reality? Eur J Dent. 2007;1:192-194.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10:225-228.

- Lubkowska A, Dolegowska B, Banfi G. Growth factor content in PRP and their applicability in medicine. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26(2 suppl 1):3S-22S.

- Pietrzak WS, Eppley BL. Platelet rich plasma: biology and new technology. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:1043-1054.

- Akcal A, Savas SA, Gorgulu T, et al. The effect of platelete rich plasma combined with microneedling on full venous outflow compromise in a rat skin flap model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(4 suppl):71-72.

- Asif M, Kanodia S, Singh K. Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling verses microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a concurrent split-face study [published online January 8, 2016]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:434-443.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Combined use of skin needling and platelet-rich plasma in acne scarring treatment. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:177-183.

- Chawla S. Split face comparative study of microneedling with PRP versus microneedling with vitamin C in treating atrophic post acne scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:209-212.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458-1466.

- Camirand A, Doucet J. Needle dermabrasion. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:48-51.

- Fernandes D. Percutaneous collagen induction: an alternative to laser resurfacing. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22:307-309.

- Fabbrocini G, Fardella N, Monfrecola A, et al. Acne scarring treatment using skin needling. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:874-879.

- Zeitter S, Sikora Z, Jahn S, et al. Microneedling: matching the results of medical needling and repetitive treatments to maximize potential for skin regeneration [published online February 7, 2014]. Burns. 2014;40:966-973.

- Schwarz M, Laaff H. A prospective controlled assessment of microneedling with the Dermaroller device. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:E146-E148.

- Fernandes D, Signorini M. Combating photoaging with percutaneous collagen induction. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:192-199.

- Aust MC, Fernandes D, Kolokythas P, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for scars, wrinkles, and skin laxity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1421-1429.

- El-Domyati M, Barakat M, Awad S, et al. Microneedling therapy for atrophic acne scars: an objective evaluation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-42.

- Leheta T, El Tawdy A, Abdel Hay R, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction versus full-concentration trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:207-216.

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843.

- Dhurat R, Mathapati S. Response to microneedling treatment in men with androgenetic alopecia who failed to respond to conventional therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:260-263.

- Dhurat R, Sukesh M, Avhad G, et al. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:6-11.

- Wang HL, Avila G. Platelet rich plasma: myth or reality? Eur J Dent. 2007;1:192-194.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10:225-228.

- Lubkowska A, Dolegowska B, Banfi G. Growth factor content in PRP and their applicability in medicine. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26(2 suppl 1):3S-22S.

- Pietrzak WS, Eppley BL. Platelet rich plasma: biology and new technology. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:1043-1054.

- Akcal A, Savas SA, Gorgulu T, et al. The effect of platelete rich plasma combined with microneedling on full venous outflow compromise in a rat skin flap model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(4 suppl):71-72.

- Asif M, Kanodia S, Singh K. Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling verses microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a concurrent split-face study [published online January 8, 2016]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:434-443.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Combined use of skin needling and platelet-rich plasma in acne scarring treatment. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:177-183.

- Chawla S. Split face comparative study of microneedling with PRP versus microneedling with vitamin C in treating atrophic post acne scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:209-212.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458-1466.

Practice Points

- Microneedling is an effective therapy for skin rejuvenation.

- Preliminary evidence indicates that the addition of platelet-rich plasma to microneedling improves cosmetic outcomes.

LGBT Access to Health Care: A Dermatologist’s Role in Building a Therapeutic Relationship

The last decade has been a period of advancement for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community for legal protections and visibility. Although the journey to acceptance and equality is far from over, this progress has appropriately extended to medical academia as physicians search for ways to become more inclusive and effective care providers for their LGBT patients.1 In a recent cross-sectional study, Ginsberg et al2 examined the role for dermatologists in the care of transgender patients. The investigators concluded that dermatologists should play a larger role in a transgender patient’s physical transformation.2 It is our opinion that dermatologists need to be comfortable building rapport with LGBT patients and to become attuned to their specific needs to provide effective care.

When forging a relationship with an LGBT patient, assumptions can damage rapport. Two assumptions that should be avoided include presuming heterosexuality or, on the other hand, assuming risk for disease based on known LGBT status. A dermatologist who takes a cursory sexual history, or none at all, assuming his/her patient is heterosexual creates an environment in which a nonheterosexual patient feels uncomfortable being honest and open. Although there is enough literature to support the claim that some sexual minority groups have increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs),3 it is dangerous to assume a patient’s risk based solely on sexual orientation. An abstinent patient or a patient in a long-term, monogamous, same-sex relationship, for instance, may feel stereotyped by a dermatologist who wants to screen him/her for an STI. The best step in building a therapeutic relationship is to cast out these assumptions and allow LGBT patients to be open about themselves and their sexual practices. Sexual histories should be asked in nonjudgmental ways that are related to the health of the patient, leading to relevant and useful information for their care. For example, ask patients, “Do you have sex with men, women, or both?” This question should be delivered in a matter-of-fact tone, which conveys to the patient that the provider merely wants an answer to guide patient care.

Dermatologists can tailor their encounters to the specific needs of sexual minority patients. The medical literature is rich with examples of conditions that occur at greater frequency in specific sexual minority groups. Sexually transmitted infections, particularly human immunodeficiency virus, are important causes of morbidity and mortality among sexual minorities, especially men who have sex with men (MSM).3,4 Anal and penile human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-associated anal carcinoma risk are increased in MSM.5,6 The literature has remained inconclusive on the use of anal Papanicolaou tests for diagnosis; however, dermatologists have a duty to at least examine the perianal and genital area of any patient at risk for HPV-related disease or STIs.7,8 For younger patients, the HPV vaccine can help prevent certain types of HPV infection and likely reduce a patient’s risk for condyloma acuminatum and other sequelae of the virus. Guidelines have been expanded to include men aged 13 to 21 years and up to 26 years.9 More research is needed to determine if detection and prevention of these types of HPV infection using the vaccine in MSM actually leads to a decreased incidence of anal carcinoma.

Certain LGBT groups may benefit from a dermatologist’s care outside the realm of infectious diseases. One study found that increased indoor tanning use in MSM correlated with increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.10 Lesbians have been found to be less likely to pursue preventative health examinations in general, including skin checks.11 Finally, transgender patients can utilize dermatologists for help with transformative procedures and side effects of hormonal treatment such as androgenic acne.1,4

Cutaneous and beyond, the future of LGBT health care in the United States is affected by the institutions that train future physicians. There is a trend toward incorporating formal LGBT curricula into medical schools and academic centers.12 The Penn Medicine Program for LGBT Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is a pilot program geared toward both educating future clinicians and providing equal and unbiased care to LGBT patients.12 Programs such as this one give rise to a new generation of physicians who feel comfortable and aware of the needs of their LGBT patients.

In a time when LGBT patients are becoming more comfortable claiming their sexual and gender identities openly, there is a need for dermatologists to provide individualized unbiased care, which can best be achieved by building rapport through assumption-free history taking, performing thorough physical examinations that include the genital and perianal area, and passing these good practices on to trainees.

- Snyder JE. Trend analysis of medical publications about LGBT persons: 1950-2007. J Homosex. 2011;58:164-188.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Gee R. Primary care health issues among men who have sex with men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:144-153.

- Katz KA, Furnish TJ. Dermatology-related epidemiologic and clinical concerns of men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and transgender individuals. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1303-1310.

- Fenkl EA, Jones SG, Schochet E, et al. HPV and anal cancer knowledge among HIV-infected and non-infected men who have sex with men [published online December 11, 2015]. LGBT Health. 2016;3:42-48. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0086.

- Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, et al. Age-related prevalence of anal cancer precursors in homosexual men: the EXPLORE Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:896-905.

- Schofield AM, Sadler L, Nelson L, et al. A prospective study of anal cancer screening in HIV-positive and negative MSM. AIDS. 2016;30:1375-1383.

- Katz MH, Katz KA, Bernestein KT, et al. We need data on anal screening effectiveness before focusing on increasing it [published online September 23, 2010]. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2016.

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-Valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:300-304.

- Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, et al. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1308-1316.

- Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953-1960.

- Yehia BR, Calder D, Flesch JD, et al. Advancing LGBT health at an academic medical center: a case study. LGBT Health. 2015;2:362-366.

The last decade has been a period of advancement for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community for legal protections and visibility. Although the journey to acceptance and equality is far from over, this progress has appropriately extended to medical academia as physicians search for ways to become more inclusive and effective care providers for their LGBT patients.1 In a recent cross-sectional study, Ginsberg et al2 examined the role for dermatologists in the care of transgender patients. The investigators concluded that dermatologists should play a larger role in a transgender patient’s physical transformation.2 It is our opinion that dermatologists need to be comfortable building rapport with LGBT patients and to become attuned to their specific needs to provide effective care.

When forging a relationship with an LGBT patient, assumptions can damage rapport. Two assumptions that should be avoided include presuming heterosexuality or, on the other hand, assuming risk for disease based on known LGBT status. A dermatologist who takes a cursory sexual history, or none at all, assuming his/her patient is heterosexual creates an environment in which a nonheterosexual patient feels uncomfortable being honest and open. Although there is enough literature to support the claim that some sexual minority groups have increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs),3 it is dangerous to assume a patient’s risk based solely on sexual orientation. An abstinent patient or a patient in a long-term, monogamous, same-sex relationship, for instance, may feel stereotyped by a dermatologist who wants to screen him/her for an STI. The best step in building a therapeutic relationship is to cast out these assumptions and allow LGBT patients to be open about themselves and their sexual practices. Sexual histories should be asked in nonjudgmental ways that are related to the health of the patient, leading to relevant and useful information for their care. For example, ask patients, “Do you have sex with men, women, or both?” This question should be delivered in a matter-of-fact tone, which conveys to the patient that the provider merely wants an answer to guide patient care.

Dermatologists can tailor their encounters to the specific needs of sexual minority patients. The medical literature is rich with examples of conditions that occur at greater frequency in specific sexual minority groups. Sexually transmitted infections, particularly human immunodeficiency virus, are important causes of morbidity and mortality among sexual minorities, especially men who have sex with men (MSM).3,4 Anal and penile human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-associated anal carcinoma risk are increased in MSM.5,6 The literature has remained inconclusive on the use of anal Papanicolaou tests for diagnosis; however, dermatologists have a duty to at least examine the perianal and genital area of any patient at risk for HPV-related disease or STIs.7,8 For younger patients, the HPV vaccine can help prevent certain types of HPV infection and likely reduce a patient’s risk for condyloma acuminatum and other sequelae of the virus. Guidelines have been expanded to include men aged 13 to 21 years and up to 26 years.9 More research is needed to determine if detection and prevention of these types of HPV infection using the vaccine in MSM actually leads to a decreased incidence of anal carcinoma.

Certain LGBT groups may benefit from a dermatologist’s care outside the realm of infectious diseases. One study found that increased indoor tanning use in MSM correlated with increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.10 Lesbians have been found to be less likely to pursue preventative health examinations in general, including skin checks.11 Finally, transgender patients can utilize dermatologists for help with transformative procedures and side effects of hormonal treatment such as androgenic acne.1,4

Cutaneous and beyond, the future of LGBT health care in the United States is affected by the institutions that train future physicians. There is a trend toward incorporating formal LGBT curricula into medical schools and academic centers.12 The Penn Medicine Program for LGBT Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is a pilot program geared toward both educating future clinicians and providing equal and unbiased care to LGBT patients.12 Programs such as this one give rise to a new generation of physicians who feel comfortable and aware of the needs of their LGBT patients.

In a time when LGBT patients are becoming more comfortable claiming their sexual and gender identities openly, there is a need for dermatologists to provide individualized unbiased care, which can best be achieved by building rapport through assumption-free history taking, performing thorough physical examinations that include the genital and perianal area, and passing these good practices on to trainees.

The last decade has been a period of advancement for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community for legal protections and visibility. Although the journey to acceptance and equality is far from over, this progress has appropriately extended to medical academia as physicians search for ways to become more inclusive and effective care providers for their LGBT patients.1 In a recent cross-sectional study, Ginsberg et al2 examined the role for dermatologists in the care of transgender patients. The investigators concluded that dermatologists should play a larger role in a transgender patient’s physical transformation.2 It is our opinion that dermatologists need to be comfortable building rapport with LGBT patients and to become attuned to their specific needs to provide effective care.

When forging a relationship with an LGBT patient, assumptions can damage rapport. Two assumptions that should be avoided include presuming heterosexuality or, on the other hand, assuming risk for disease based on known LGBT status. A dermatologist who takes a cursory sexual history, or none at all, assuming his/her patient is heterosexual creates an environment in which a nonheterosexual patient feels uncomfortable being honest and open. Although there is enough literature to support the claim that some sexual minority groups have increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs),3 it is dangerous to assume a patient’s risk based solely on sexual orientation. An abstinent patient or a patient in a long-term, monogamous, same-sex relationship, for instance, may feel stereotyped by a dermatologist who wants to screen him/her for an STI. The best step in building a therapeutic relationship is to cast out these assumptions and allow LGBT patients to be open about themselves and their sexual practices. Sexual histories should be asked in nonjudgmental ways that are related to the health of the patient, leading to relevant and useful information for their care. For example, ask patients, “Do you have sex with men, women, or both?” This question should be delivered in a matter-of-fact tone, which conveys to the patient that the provider merely wants an answer to guide patient care.

Dermatologists can tailor their encounters to the specific needs of sexual minority patients. The medical literature is rich with examples of conditions that occur at greater frequency in specific sexual minority groups. Sexually transmitted infections, particularly human immunodeficiency virus, are important causes of morbidity and mortality among sexual minorities, especially men who have sex with men (MSM).3,4 Anal and penile human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-associated anal carcinoma risk are increased in MSM.5,6 The literature has remained inconclusive on the use of anal Papanicolaou tests for diagnosis; however, dermatologists have a duty to at least examine the perianal and genital area of any patient at risk for HPV-related disease or STIs.7,8 For younger patients, the HPV vaccine can help prevent certain types of HPV infection and likely reduce a patient’s risk for condyloma acuminatum and other sequelae of the virus. Guidelines have been expanded to include men aged 13 to 21 years and up to 26 years.9 More research is needed to determine if detection and prevention of these types of HPV infection using the vaccine in MSM actually leads to a decreased incidence of anal carcinoma.

Certain LGBT groups may benefit from a dermatologist’s care outside the realm of infectious diseases. One study found that increased indoor tanning use in MSM correlated with increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.10 Lesbians have been found to be less likely to pursue preventative health examinations in general, including skin checks.11 Finally, transgender patients can utilize dermatologists for help with transformative procedures and side effects of hormonal treatment such as androgenic acne.1,4

Cutaneous and beyond, the future of LGBT health care in the United States is affected by the institutions that train future physicians. There is a trend toward incorporating formal LGBT curricula into medical schools and academic centers.12 The Penn Medicine Program for LGBT Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is a pilot program geared toward both educating future clinicians and providing equal and unbiased care to LGBT patients.12 Programs such as this one give rise to a new generation of physicians who feel comfortable and aware of the needs of their LGBT patients.

In a time when LGBT patients are becoming more comfortable claiming their sexual and gender identities openly, there is a need for dermatologists to provide individualized unbiased care, which can best be achieved by building rapport through assumption-free history taking, performing thorough physical examinations that include the genital and perianal area, and passing these good practices on to trainees.

- Snyder JE. Trend analysis of medical publications about LGBT persons: 1950-2007. J Homosex. 2011;58:164-188.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Gee R. Primary care health issues among men who have sex with men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:144-153.

- Katz KA, Furnish TJ. Dermatology-related epidemiologic and clinical concerns of men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and transgender individuals. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1303-1310.

- Fenkl EA, Jones SG, Schochet E, et al. HPV and anal cancer knowledge among HIV-infected and non-infected men who have sex with men [published online December 11, 2015]. LGBT Health. 2016;3:42-48. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0086.

- Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, et al. Age-related prevalence of anal cancer precursors in homosexual men: the EXPLORE Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:896-905.

- Schofield AM, Sadler L, Nelson L, et al. A prospective study of anal cancer screening in HIV-positive and negative MSM. AIDS. 2016;30:1375-1383.

- Katz MH, Katz KA, Bernestein KT, et al. We need data on anal screening effectiveness before focusing on increasing it [published online September 23, 2010]. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2016.

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-Valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:300-304.

- Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, et al. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1308-1316.

- Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953-1960.

- Yehia BR, Calder D, Flesch JD, et al. Advancing LGBT health at an academic medical center: a case study. LGBT Health. 2015;2:362-366.

- Snyder JE. Trend analysis of medical publications about LGBT persons: 1950-2007. J Homosex. 2011;58:164-188.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Gee R. Primary care health issues among men who have sex with men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:144-153.

- Katz KA, Furnish TJ. Dermatology-related epidemiologic and clinical concerns of men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and transgender individuals. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1303-1310.

- Fenkl EA, Jones SG, Schochet E, et al. HPV and anal cancer knowledge among HIV-infected and non-infected men who have sex with men [published online December 11, 2015]. LGBT Health. 2016;3:42-48. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0086.