User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Evaluating Dermatology Apps for Patient Education

Debunking Acne Myths: Does Wearing Makeup Cause Acne?

Myth: Wearing makeup causes acne breakouts

Acne breakouts caused by makeup and other skin care products, known as acne cosmetica, typically resolve when patients stop using pore-clogging products; however, the overall impact of cosmetics on the development of acne lesions is considered to be negligible. Many cosmetics are not inherently comedogenic and can be used safely by patients in combination with proper skin care techniques.

Although dermatologists may be inclined to discourage makeup use during acne treatment or breakouts due to its potential to aggravate the patient’s condition, research has shown that treatment results and quality of life (QoL) scores associated with makeup use in acne patients may improve when patients receive instruction on how to use skin care products and cosmetics effectively. In one study of 50 female acne patients, 25 participants were instructed on how to use skin care products and cosmetics, and the other 25 participants received no specific instructions from dermatologists. After 4 weeks of treatment with conventional topical and/or oral acne medications, the investigators concluded that use of skin care products did not negatively impact acne treatment, and the group that received application instructions showed more notable improvements in QoL scores versus those who did not. In another study, the overall number of acne eruptions decreased over a 2- to 4-week period in female acne patients who were trained by a makeup artist to apply cosmetics while undergoing acne treatment. These results suggest that acne patients who wear makeup may benefit from a conversation with their dermatologist about what products and skin care techniques they can use to minimize exacerbation of or even improve their condition.

When choosing makeup that will not cause or exacerbate acne breakouts, patients should look for packaging that indicates the product will not clog pores and is oil-free, noncomedogenic, and/or nonacnegenic. Some makeup products are specifically formulated to help camouflage redness and pimples, which can help improve quality of life and self-esteem in acne patients who otherwise may be self-conscious about their appearance. Mineral-based cosmetics containing powdered formulas of silica, titanium dioxide, and zinc oxide can be used to absorb oil, camouflage redness, and prevent irritation. Anti-inflammatory ingredients and antioxidants also are used in some makeup products to reduce skin irritation and promote barrier repair. Additional cosmetic ingredients that can affect the mechanisms of acne pathogenesis and may contribute to a decrease in acne lesions include nicotinamide, lactic acid, triethyl acetate/ethyllineolate, and prebiotic plant extracts.

Makeup should be applied gently to avoid irritating the skin. It also is important to remind patients not to share their makeup brushes and applicators and to clean them weekly to ensure that bacteria, dead skin cells, and oil are not spread to the skin, which can lead to new breakouts. Although patients may be compelled to scrub the skin to remove makeup, a mild cleanser should be gently applied using the fingertips and rinsed off with lukewarm water to minimize skin irritation. Any makeup remaining on the skin after washing should be gently removed with an oil-free makeup remover.

Hayashi N, Imori M, Yanagisawa M, et al. Make-up improves the quality of life of acne patients without aggravating acne eruptions during treatments. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:284-287.

I have acne! is it okay to wear makeup? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/makeup-with-acne. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Korting HC, Borelli C, Schöllmann C. Acne vulgaris. role of cosmetics [in German]. 2010;61:126-131.

Matsuoka Y, Yoneda K, Sadahira C, et al. Effects of skin care and makeup under instructions from dermatologists on the quality of life of female patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2006;33:745-752.

Proper skin care lays the foundation for successful acne and rosacea treatment. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/proper-skin-care-lays-the-foundation-for-successful-acne-and-rosacea-treatment Published July 31, 2013. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Myth: Wearing makeup causes acne breakouts

Acne breakouts caused by makeup and other skin care products, known as acne cosmetica, typically resolve when patients stop using pore-clogging products; however, the overall impact of cosmetics on the development of acne lesions is considered to be negligible. Many cosmetics are not inherently comedogenic and can be used safely by patients in combination with proper skin care techniques.

Although dermatologists may be inclined to discourage makeup use during acne treatment or breakouts due to its potential to aggravate the patient’s condition, research has shown that treatment results and quality of life (QoL) scores associated with makeup use in acne patients may improve when patients receive instruction on how to use skin care products and cosmetics effectively. In one study of 50 female acne patients, 25 participants were instructed on how to use skin care products and cosmetics, and the other 25 participants received no specific instructions from dermatologists. After 4 weeks of treatment with conventional topical and/or oral acne medications, the investigators concluded that use of skin care products did not negatively impact acne treatment, and the group that received application instructions showed more notable improvements in QoL scores versus those who did not. In another study, the overall number of acne eruptions decreased over a 2- to 4-week period in female acne patients who were trained by a makeup artist to apply cosmetics while undergoing acne treatment. These results suggest that acne patients who wear makeup may benefit from a conversation with their dermatologist about what products and skin care techniques they can use to minimize exacerbation of or even improve their condition.

When choosing makeup that will not cause or exacerbate acne breakouts, patients should look for packaging that indicates the product will not clog pores and is oil-free, noncomedogenic, and/or nonacnegenic. Some makeup products are specifically formulated to help camouflage redness and pimples, which can help improve quality of life and self-esteem in acne patients who otherwise may be self-conscious about their appearance. Mineral-based cosmetics containing powdered formulas of silica, titanium dioxide, and zinc oxide can be used to absorb oil, camouflage redness, and prevent irritation. Anti-inflammatory ingredients and antioxidants also are used in some makeup products to reduce skin irritation and promote barrier repair. Additional cosmetic ingredients that can affect the mechanisms of acne pathogenesis and may contribute to a decrease in acne lesions include nicotinamide, lactic acid, triethyl acetate/ethyllineolate, and prebiotic plant extracts.

Makeup should be applied gently to avoid irritating the skin. It also is important to remind patients not to share their makeup brushes and applicators and to clean them weekly to ensure that bacteria, dead skin cells, and oil are not spread to the skin, which can lead to new breakouts. Although patients may be compelled to scrub the skin to remove makeup, a mild cleanser should be gently applied using the fingertips and rinsed off with lukewarm water to minimize skin irritation. Any makeup remaining on the skin after washing should be gently removed with an oil-free makeup remover.

Myth: Wearing makeup causes acne breakouts

Acne breakouts caused by makeup and other skin care products, known as acne cosmetica, typically resolve when patients stop using pore-clogging products; however, the overall impact of cosmetics on the development of acne lesions is considered to be negligible. Many cosmetics are not inherently comedogenic and can be used safely by patients in combination with proper skin care techniques.

Although dermatologists may be inclined to discourage makeup use during acne treatment or breakouts due to its potential to aggravate the patient’s condition, research has shown that treatment results and quality of life (QoL) scores associated with makeup use in acne patients may improve when patients receive instruction on how to use skin care products and cosmetics effectively. In one study of 50 female acne patients, 25 participants were instructed on how to use skin care products and cosmetics, and the other 25 participants received no specific instructions from dermatologists. After 4 weeks of treatment with conventional topical and/or oral acne medications, the investigators concluded that use of skin care products did not negatively impact acne treatment, and the group that received application instructions showed more notable improvements in QoL scores versus those who did not. In another study, the overall number of acne eruptions decreased over a 2- to 4-week period in female acne patients who were trained by a makeup artist to apply cosmetics while undergoing acne treatment. These results suggest that acne patients who wear makeup may benefit from a conversation with their dermatologist about what products and skin care techniques they can use to minimize exacerbation of or even improve their condition.

When choosing makeup that will not cause or exacerbate acne breakouts, patients should look for packaging that indicates the product will not clog pores and is oil-free, noncomedogenic, and/or nonacnegenic. Some makeup products are specifically formulated to help camouflage redness and pimples, which can help improve quality of life and self-esteem in acne patients who otherwise may be self-conscious about their appearance. Mineral-based cosmetics containing powdered formulas of silica, titanium dioxide, and zinc oxide can be used to absorb oil, camouflage redness, and prevent irritation. Anti-inflammatory ingredients and antioxidants also are used in some makeup products to reduce skin irritation and promote barrier repair. Additional cosmetic ingredients that can affect the mechanisms of acne pathogenesis and may contribute to a decrease in acne lesions include nicotinamide, lactic acid, triethyl acetate/ethyllineolate, and prebiotic plant extracts.

Makeup should be applied gently to avoid irritating the skin. It also is important to remind patients not to share their makeup brushes and applicators and to clean them weekly to ensure that bacteria, dead skin cells, and oil are not spread to the skin, which can lead to new breakouts. Although patients may be compelled to scrub the skin to remove makeup, a mild cleanser should be gently applied using the fingertips and rinsed off with lukewarm water to minimize skin irritation. Any makeup remaining on the skin after washing should be gently removed with an oil-free makeup remover.

Hayashi N, Imori M, Yanagisawa M, et al. Make-up improves the quality of life of acne patients without aggravating acne eruptions during treatments. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:284-287.

I have acne! is it okay to wear makeup? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/makeup-with-acne. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Korting HC, Borelli C, Schöllmann C. Acne vulgaris. role of cosmetics [in German]. 2010;61:126-131.

Matsuoka Y, Yoneda K, Sadahira C, et al. Effects of skin care and makeup under instructions from dermatologists on the quality of life of female patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2006;33:745-752.

Proper skin care lays the foundation for successful acne and rosacea treatment. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/proper-skin-care-lays-the-foundation-for-successful-acne-and-rosacea-treatment Published July 31, 2013. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Hayashi N, Imori M, Yanagisawa M, et al. Make-up improves the quality of life of acne patients without aggravating acne eruptions during treatments. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:284-287.

I have acne! is it okay to wear makeup? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/makeup-with-acne. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Korting HC, Borelli C, Schöllmann C. Acne vulgaris. role of cosmetics [in German]. 2010;61:126-131.

Matsuoka Y, Yoneda K, Sadahira C, et al. Effects of skin care and makeup under instructions from dermatologists on the quality of life of female patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2006;33:745-752.

Proper skin care lays the foundation for successful acne and rosacea treatment. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/proper-skin-care-lays-the-foundation-for-successful-acne-and-rosacea-treatment Published July 31, 2013. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Hypopigmented Discoloration on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

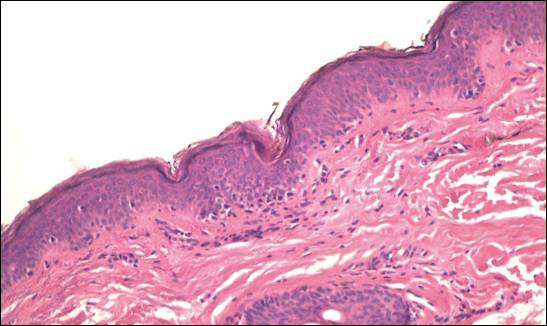

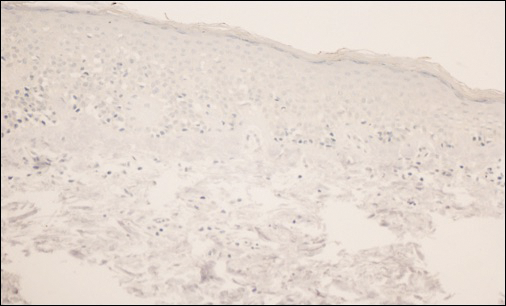

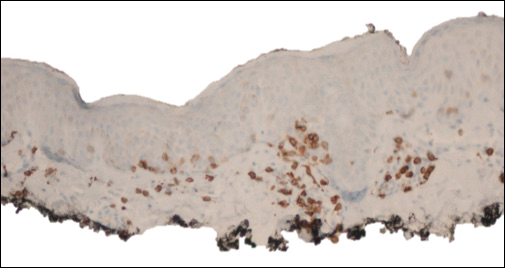

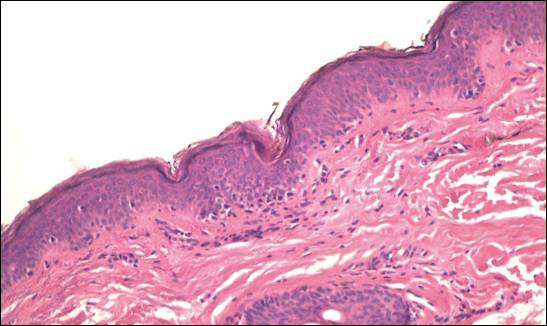

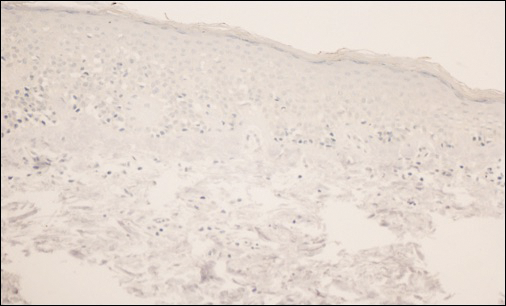

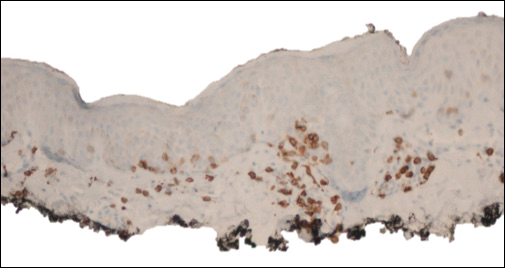

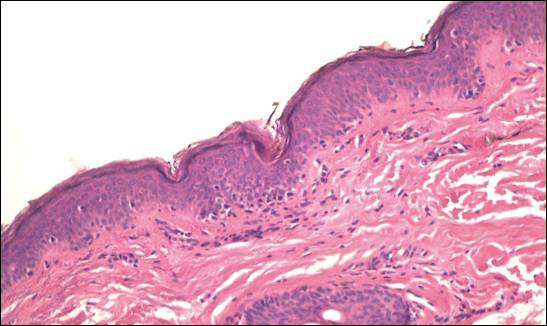

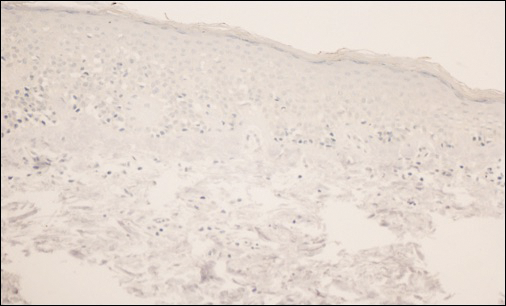

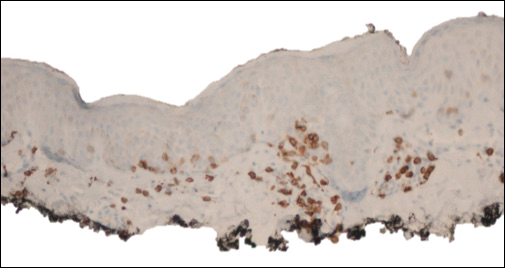

The patient was started on clobetasol dipropionate cream 0.05% twice daily, which she did not tolerate due to a burning sensation on application. She then was started on narrowband UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly, and the hypopigmented areas began to improve. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was discontinued after 7 weeks due to the high cost to the patient, but the hypopigmented patches on the left thigh appeared to remit, and the patient did not return to the clinic for 6 months. She returned when the areas on the left thigh reappeared, along with new areas on the right buttock and right medial upper arm. Serial biopsies of the new patches also revealed a CD8+ atypical lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with hypopigmented patch-stage mycosis fungoides (MF). She was started on halobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to affected areas, which she tolerated well. Complete blood count and peripheral blood smear were unremarkable, and the patient continued to deny systemic symptoms. Over the next year, the patient's cutaneous findings continued to wax and wane with topical treatment, and she was referred to a regional cancer treatment center for a second opinion from a hematopathologist. Hematopathologic and dermatopathologic review of the case, including hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining, was highly consistent with hypopigmented MF (Figures 1-3).

Mycosis fungoides is an uncommon disease characterized by atypical clonal T cells exhibiting epidermotropism. Most commonly, MF is characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate. Mycosis fungoides can be difficult to diagnose in its early stages, as it may resemble benign inflammatory conditions (eg, chronic atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema) and often requires biopsy and additional studies, such as immunohistochemistry, to secure a diagnosis. Hypopigmented MF is regarded as a subtype of MF, as it can exhibit different clinical and pathologic characteristics from classical MF. In particular, the lymphocytic phenotype in hypopigmented MF is more likely to be CD8+.

In general, the progression of MF is characterized as stage IA (patches or plaques involving less than 10% body surface area [BSA]), IB (patches or plaques involving ≥10% BSA without lymph node or visceral involvement), IIA (patches or plaques of any percentage of BSA with lymph node involvement), IIB (cutaneous tumors with or without lymph node involvement), III (erythroderma with low blood tumor burden), or IV (erythroderma with high blood tumor burden with or without visceral involvement). Hypopigmented MF generally presents in early patch stage and rarely progresses past stage IB, and thus generally has a favorable prognosis.1,2 Kim et al3 demonstrated that evolution from patch to plaque stage MF is accompanied by a shift in lymphocytes from the T helper 1 (Th1) to T helper 2 phenotype; therefore the Th1 phenotype, CD8+ T cells are associated with lower risk for disease progression. Other investigators also have hypothesized that predominance of Th1 phenotype, CD8+ T cells may have an immunoregulatory effect, thus preventing evolution of disease from patch to plaque stage and explaining why hypopigmented MF, with a predominantly CD8+ phenotype, confers better prognosis with less chance for disease progression than classical MF.4,5 The patch- or plaque-stage lesions of classical MF have a predilection for non-sun exposed areas (eg, buttocks, medial thighs, breasts),2 whereas hypopigmented MF tends to present with hypopigmented or depigmented lesions mainly distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. These lesions may become more visible following sun exposure.1 The size of the hypopigmented lesions can vary, and patients may complain of pruritus with variable intensity.

Hypopigmented MF presents more commonly in younger populations, in contrast to classical MF.6-8 However, like classical MF, hypopigmented MF appears to more frequently affect individuals with darker Fitzpatrick skin types.1,9,10 Although it generally is accepted that hypopigmented MF does not favor either sex, some studies suggest that hypopigmented MF has a female predominance.6,10

Classical MF is characterized by an epidermotropic infiltrate of CD4+ T helper cells,10 whereas CD8+ epidermotropism is considered hallmark in hypopigmented MF.10-12 The other typical histopathologic features of hypopigmented MF generally are identical to those of classical MF, with solitary or small groups of atypical haloed lymphocytes within the basal layer, exocytosis of lymphocytes out of proportion to spongiosis, and papillary dermal fibrosis. Immunohistochemistry generally is helpful in distinguishing between classical MF and hypopigmented MF.

The clinical differential diagnosis for hypopigmented MF includes the early (inflammatory) stage of vitiligo, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, lichen sclerosus, pityriasis alba, and leprosy.

First-line treatment for hypopigmented MF consists of phototherapy/photochemotherapy and topical steroids.9,13 Narrowband UVB phototherapy has been used with good success in pediatric patients.14 However, narrowband UVB may not be as effective in darker-skinned individuals; it has been hypothesized that this lack of efficacy could be due to the protective effects of increased melanin in the skin.1 Other topical therapies may include topical carmustine and topical nitrogen mustard.

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Girardi M, Heald PW, Wilson LD. The pathogenesis of mycosis fungoides. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1978-1988.

- Kim EJ, Hess S, Richardson SK, et al. Immunopathogenesis and therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:798-812.

- Stone ML, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ, et al. Hypopigmented report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Cutis. 2001;67:133-138.

- Volkenandt M, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Molecular detection of clone-specific DNA in hypopigmented lesions of a patient with early evolving mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:423-428.

- Furlan FC, Pereira BA, Sotto MN, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides versus mycosis fungoides with concomitant hypopigmented lesions: same disease or different variants of mycosis fungoides? Dermatology. 2014;229:271-274.

- Ardigó M, Borroni G, Muscardin L, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Caucasian patients: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:264-270.

- Boulos S, Vaid R, Aladily TN, et al. Clinical presentation, immunopathology, and treatment of juvenile-onset mycosis fungoides: a case series of 34 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1117-1126.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Phelps R, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Cerroni L, Medeiros LJ, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Frequent expression of a CD8+ T-cell phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:450-457.

- Furlan FC, de Paula Pereira BA, da Silva LF, et al. Loss of melanocytes in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a study of 18 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:101-107.

- Tolkachjov SN, Comfere NI. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a clinical mimicker of vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:193-194.

- Duarte I, Bedrikow, R, Aoki S. Mycosis fungoides: epidemiologic study of 17 cases and evaluation of PUVA photochemotherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:40-45.

- Onsun N, Kural Y, Su O, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides associated with atopy in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:493-496.

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

The patient was started on clobetasol dipropionate cream 0.05% twice daily, which she did not tolerate due to a burning sensation on application. She then was started on narrowband UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly, and the hypopigmented areas began to improve. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was discontinued after 7 weeks due to the high cost to the patient, but the hypopigmented patches on the left thigh appeared to remit, and the patient did not return to the clinic for 6 months. She returned when the areas on the left thigh reappeared, along with new areas on the right buttock and right medial upper arm. Serial biopsies of the new patches also revealed a CD8+ atypical lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with hypopigmented patch-stage mycosis fungoides (MF). She was started on halobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to affected areas, which she tolerated well. Complete blood count and peripheral blood smear were unremarkable, and the patient continued to deny systemic symptoms. Over the next year, the patient's cutaneous findings continued to wax and wane with topical treatment, and she was referred to a regional cancer treatment center for a second opinion from a hematopathologist. Hematopathologic and dermatopathologic review of the case, including hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining, was highly consistent with hypopigmented MF (Figures 1-3).

Mycosis fungoides is an uncommon disease characterized by atypical clonal T cells exhibiting epidermotropism. Most commonly, MF is characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate. Mycosis fungoides can be difficult to diagnose in its early stages, as it may resemble benign inflammatory conditions (eg, chronic atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema) and often requires biopsy and additional studies, such as immunohistochemistry, to secure a diagnosis. Hypopigmented MF is regarded as a subtype of MF, as it can exhibit different clinical and pathologic characteristics from classical MF. In particular, the lymphocytic phenotype in hypopigmented MF is more likely to be CD8+.

In general, the progression of MF is characterized as stage IA (patches or plaques involving less than 10% body surface area [BSA]), IB (patches or plaques involving ≥10% BSA without lymph node or visceral involvement), IIA (patches or plaques of any percentage of BSA with lymph node involvement), IIB (cutaneous tumors with or without lymph node involvement), III (erythroderma with low blood tumor burden), or IV (erythroderma with high blood tumor burden with or without visceral involvement). Hypopigmented MF generally presents in early patch stage and rarely progresses past stage IB, and thus generally has a favorable prognosis.1,2 Kim et al3 demonstrated that evolution from patch to plaque stage MF is accompanied by a shift in lymphocytes from the T helper 1 (Th1) to T helper 2 phenotype; therefore the Th1 phenotype, CD8+ T cells are associated with lower risk for disease progression. Other investigators also have hypothesized that predominance of Th1 phenotype, CD8+ T cells may have an immunoregulatory effect, thus preventing evolution of disease from patch to plaque stage and explaining why hypopigmented MF, with a predominantly CD8+ phenotype, confers better prognosis with less chance for disease progression than classical MF.4,5 The patch- or plaque-stage lesions of classical MF have a predilection for non-sun exposed areas (eg, buttocks, medial thighs, breasts),2 whereas hypopigmented MF tends to present with hypopigmented or depigmented lesions mainly distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. These lesions may become more visible following sun exposure.1 The size of the hypopigmented lesions can vary, and patients may complain of pruritus with variable intensity.

Hypopigmented MF presents more commonly in younger populations, in contrast to classical MF.6-8 However, like classical MF, hypopigmented MF appears to more frequently affect individuals with darker Fitzpatrick skin types.1,9,10 Although it generally is accepted that hypopigmented MF does not favor either sex, some studies suggest that hypopigmented MF has a female predominance.6,10

Classical MF is characterized by an epidermotropic infiltrate of CD4+ T helper cells,10 whereas CD8+ epidermotropism is considered hallmark in hypopigmented MF.10-12 The other typical histopathologic features of hypopigmented MF generally are identical to those of classical MF, with solitary or small groups of atypical haloed lymphocytes within the basal layer, exocytosis of lymphocytes out of proportion to spongiosis, and papillary dermal fibrosis. Immunohistochemistry generally is helpful in distinguishing between classical MF and hypopigmented MF.

The clinical differential diagnosis for hypopigmented MF includes the early (inflammatory) stage of vitiligo, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, lichen sclerosus, pityriasis alba, and leprosy.

First-line treatment for hypopigmented MF consists of phototherapy/photochemotherapy and topical steroids.9,13 Narrowband UVB phototherapy has been used with good success in pediatric patients.14 However, narrowband UVB may not be as effective in darker-skinned individuals; it has been hypothesized that this lack of efficacy could be due to the protective effects of increased melanin in the skin.1 Other topical therapies may include topical carmustine and topical nitrogen mustard.

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

The patient was started on clobetasol dipropionate cream 0.05% twice daily, which she did not tolerate due to a burning sensation on application. She then was started on narrowband UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly, and the hypopigmented areas began to improve. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was discontinued after 7 weeks due to the high cost to the patient, but the hypopigmented patches on the left thigh appeared to remit, and the patient did not return to the clinic for 6 months. She returned when the areas on the left thigh reappeared, along with new areas on the right buttock and right medial upper arm. Serial biopsies of the new patches also revealed a CD8+ atypical lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with hypopigmented patch-stage mycosis fungoides (MF). She was started on halobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to affected areas, which she tolerated well. Complete blood count and peripheral blood smear were unremarkable, and the patient continued to deny systemic symptoms. Over the next year, the patient's cutaneous findings continued to wax and wane with topical treatment, and she was referred to a regional cancer treatment center for a second opinion from a hematopathologist. Hematopathologic and dermatopathologic review of the case, including hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining, was highly consistent with hypopigmented MF (Figures 1-3).

Mycosis fungoides is an uncommon disease characterized by atypical clonal T cells exhibiting epidermotropism. Most commonly, MF is characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate. Mycosis fungoides can be difficult to diagnose in its early stages, as it may resemble benign inflammatory conditions (eg, chronic atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema) and often requires biopsy and additional studies, such as immunohistochemistry, to secure a diagnosis. Hypopigmented MF is regarded as a subtype of MF, as it can exhibit different clinical and pathologic characteristics from classical MF. In particular, the lymphocytic phenotype in hypopigmented MF is more likely to be CD8+.

In general, the progression of MF is characterized as stage IA (patches or plaques involving less than 10% body surface area [BSA]), IB (patches or plaques involving ≥10% BSA without lymph node or visceral involvement), IIA (patches or plaques of any percentage of BSA with lymph node involvement), IIB (cutaneous tumors with or without lymph node involvement), III (erythroderma with low blood tumor burden), or IV (erythroderma with high blood tumor burden with or without visceral involvement). Hypopigmented MF generally presents in early patch stage and rarely progresses past stage IB, and thus generally has a favorable prognosis.1,2 Kim et al3 demonstrated that evolution from patch to plaque stage MF is accompanied by a shift in lymphocytes from the T helper 1 (Th1) to T helper 2 phenotype; therefore the Th1 phenotype, CD8+ T cells are associated with lower risk for disease progression. Other investigators also have hypothesized that predominance of Th1 phenotype, CD8+ T cells may have an immunoregulatory effect, thus preventing evolution of disease from patch to plaque stage and explaining why hypopigmented MF, with a predominantly CD8+ phenotype, confers better prognosis with less chance for disease progression than classical MF.4,5 The patch- or plaque-stage lesions of classical MF have a predilection for non-sun exposed areas (eg, buttocks, medial thighs, breasts),2 whereas hypopigmented MF tends to present with hypopigmented or depigmented lesions mainly distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. These lesions may become more visible following sun exposure.1 The size of the hypopigmented lesions can vary, and patients may complain of pruritus with variable intensity.

Hypopigmented MF presents more commonly in younger populations, in contrast to classical MF.6-8 However, like classical MF, hypopigmented MF appears to more frequently affect individuals with darker Fitzpatrick skin types.1,9,10 Although it generally is accepted that hypopigmented MF does not favor either sex, some studies suggest that hypopigmented MF has a female predominance.6,10

Classical MF is characterized by an epidermotropic infiltrate of CD4+ T helper cells,10 whereas CD8+ epidermotropism is considered hallmark in hypopigmented MF.10-12 The other typical histopathologic features of hypopigmented MF generally are identical to those of classical MF, with solitary or small groups of atypical haloed lymphocytes within the basal layer, exocytosis of lymphocytes out of proportion to spongiosis, and papillary dermal fibrosis. Immunohistochemistry generally is helpful in distinguishing between classical MF and hypopigmented MF.

The clinical differential diagnosis for hypopigmented MF includes the early (inflammatory) stage of vitiligo, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, lichen sclerosus, pityriasis alba, and leprosy.

First-line treatment for hypopigmented MF consists of phototherapy/photochemotherapy and topical steroids.9,13 Narrowband UVB phototherapy has been used with good success in pediatric patients.14 However, narrowband UVB may not be as effective in darker-skinned individuals; it has been hypothesized that this lack of efficacy could be due to the protective effects of increased melanin in the skin.1 Other topical therapies may include topical carmustine and topical nitrogen mustard.

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Girardi M, Heald PW, Wilson LD. The pathogenesis of mycosis fungoides. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1978-1988.

- Kim EJ, Hess S, Richardson SK, et al. Immunopathogenesis and therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:798-812.

- Stone ML, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ, et al. Hypopigmented report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Cutis. 2001;67:133-138.

- Volkenandt M, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Molecular detection of clone-specific DNA in hypopigmented lesions of a patient with early evolving mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:423-428.

- Furlan FC, Pereira BA, Sotto MN, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides versus mycosis fungoides with concomitant hypopigmented lesions: same disease or different variants of mycosis fungoides? Dermatology. 2014;229:271-274.

- Ardigó M, Borroni G, Muscardin L, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Caucasian patients: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:264-270.

- Boulos S, Vaid R, Aladily TN, et al. Clinical presentation, immunopathology, and treatment of juvenile-onset mycosis fungoides: a case series of 34 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1117-1126.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Phelps R, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Cerroni L, Medeiros LJ, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Frequent expression of a CD8+ T-cell phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:450-457.

- Furlan FC, de Paula Pereira BA, da Silva LF, et al. Loss of melanocytes in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a study of 18 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:101-107.

- Tolkachjov SN, Comfere NI. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a clinical mimicker of vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:193-194.

- Duarte I, Bedrikow, R, Aoki S. Mycosis fungoides: epidemiologic study of 17 cases and evaluation of PUVA photochemotherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:40-45.

- Onsun N, Kural Y, Su O, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides associated with atopy in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:493-496.

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Girardi M, Heald PW, Wilson LD. The pathogenesis of mycosis fungoides. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1978-1988.

- Kim EJ, Hess S, Richardson SK, et al. Immunopathogenesis and therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:798-812.

- Stone ML, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ, et al. Hypopigmented report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Cutis. 2001;67:133-138.

- Volkenandt M, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Molecular detection of clone-specific DNA in hypopigmented lesions of a patient with early evolving mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:423-428.

- Furlan FC, Pereira BA, Sotto MN, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides versus mycosis fungoides with concomitant hypopigmented lesions: same disease or different variants of mycosis fungoides? Dermatology. 2014;229:271-274.

- Ardigó M, Borroni G, Muscardin L, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Caucasian patients: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:264-270.

- Boulos S, Vaid R, Aladily TN, et al. Clinical presentation, immunopathology, and treatment of juvenile-onset mycosis fungoides: a case series of 34 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1117-1126.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Phelps R, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Cerroni L, Medeiros LJ, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Frequent expression of a CD8+ T-cell phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:450-457.

- Furlan FC, de Paula Pereira BA, da Silva LF, et al. Loss of melanocytes in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a study of 18 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:101-107.

- Tolkachjov SN, Comfere NI. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a clinical mimicker of vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:193-194.

- Duarte I, Bedrikow, R, Aoki S. Mycosis fungoides: epidemiologic study of 17 cases and evaluation of PUVA photochemotherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:40-45.

- Onsun N, Kural Y, Su O, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides associated with atopy in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:493-496.

A 39-year-old woman presented with 2 areas of hypopigmented discoloration on the left thigh of 6 months' duration. The hypopigmentation was more visible following sun exposure because the areas did not tan. The patient had not sought prior treatment for the discoloration and denied any previous rash or trauma to the area. Her medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism associated with mild and transient alopecia, acne, and xerosis. Her daily medications included oral contraceptive pills (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol), oral levothyroxine/liothyronine, and sulfacetamide lotion 10%. She denied any allergies, and the remainder of her medical, surgical, social, and family history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative for enlarged lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, and fatigue. Physical examination revealed 2 subtle hypopigmented patches with fine, atrophic, cigarette paper-like wrinkling distributed on the left medial and posterior upper thigh. Initial biopsy of the hypopigmented patches revealed a CD8+ lymphocytic infiltrate with an atypical interface.

National Health Council to Host Workshop for Patient Organizations

The National Health Council will host a free workshop in Washington, DC, for patient advocacy organizations on Feb. 15, 2018 on engaging in quality measurement and research. More.

The National Health Council will host a free workshop in Washington, DC, for patient advocacy organizations on Feb. 15, 2018 on engaging in quality measurement and research. More.

The National Health Council will host a free workshop in Washington, DC, for patient advocacy organizations on Feb. 15, 2018 on engaging in quality measurement and research. More.

NORD Call for Abstracts Reopened

Grants are available through the NORD Research Program for the study of cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. View the RFPs here.

Grants are available through the NORD Research Program for the study of cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. View the RFPs here.

Grants are available through the NORD Research Program for the study of cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. View the RFPs here.

NORD Submits Comments to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

NORD has been, and will continue to be, engaged in a number of activities to protect access to quality health care coverage for Medicaid beneficiaries. Most recently, NORD has submitted comments to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regarding Kansas’ effort to implement work requirements and a lifetime limit in its Medicaid program. Read the comments.

NORD has been, and will continue to be, engaged in a number of activities to protect access to quality health care coverage for Medicaid beneficiaries. Most recently, NORD has submitted comments to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regarding Kansas’ effort to implement work requirements and a lifetime limit in its Medicaid program. Read the comments.

NORD has been, and will continue to be, engaged in a number of activities to protect access to quality health care coverage for Medicaid beneficiaries. Most recently, NORD has submitted comments to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regarding Kansas’ effort to implement work requirements and a lifetime limit in its Medicaid program. Read the comments.

NORD Advocates for Iowa Co-pay Choice Bill

NORD has been advocating for the Iowa Co-pay Choice Bill (SSB 3004). This legislation would help with rising out-of-pocket costs. Specifically, SSB 3004 gives choice and co-pay predictability to Iowa families by requiring that insurance providers offer a minimum number of plans that provide a traditional co-pay option, as opposed to co-insurance. NORD will continue to advocate for this legislation throughout February.

NORD has been advocating for the Iowa Co-pay Choice Bill (SSB 3004). This legislation would help with rising out-of-pocket costs. Specifically, SSB 3004 gives choice and co-pay predictability to Iowa families by requiring that insurance providers offer a minimum number of plans that provide a traditional co-pay option, as opposed to co-insurance. NORD will continue to advocate for this legislation throughout February.

NORD has been advocating for the Iowa Co-pay Choice Bill (SSB 3004). This legislation would help with rising out-of-pocket costs. Specifically, SSB 3004 gives choice and co-pay predictability to Iowa families by requiring that insurance providers offer a minimum number of plans that provide a traditional co-pay option, as opposed to co-insurance. NORD will continue to advocate for this legislation throughout February.

Letter to Congress: NORD and Others Oppose “Right to Try”

NORD and 40 other patient organizations and professional societies have sent a letter to the leadership of the US House of Representatives explaining why they oppose “Right to Try” legislation currently being considered by Congress. Signers of the letter include the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, American Lung Association, and National Health Council. The organizations say they support patients being given access to unapproved therapies but believe the bills under consideration will not increase patient access.

NORD and 40 other patient organizations and professional societies have sent a letter to the leadership of the US House of Representatives explaining why they oppose “Right to Try” legislation currently being considered by Congress. Signers of the letter include the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, American Lung Association, and National Health Council. The organizations say they support patients being given access to unapproved therapies but believe the bills under consideration will not increase patient access.

NORD and 40 other patient organizations and professional societies have sent a letter to the leadership of the US House of Representatives explaining why they oppose “Right to Try” legislation currently being considered by Congress. Signers of the letter include the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, American Lung Association, and National Health Council. The organizations say they support patients being given access to unapproved therapies but believe the bills under consideration will not increase patient access.

Rare Disease Day Events Planned for Campuses, Hospitals, and State Legislatures

On February 28, 2018, Rare Disease Day will be observed around the world. This annual observance is intended to promote awareness of the 7,000 diseases considered rare in the US, the need for research and clinical guidelines, and the challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of life for patients. Educational events are planned at numerous hospitals, universities, schools, and community centers across the US. NORD will be hosting “State House Events” with patient advocates in more than 30 states to educate state legislators on issues related to state policy. Visit the national website hosted by NORD. Visit the international website.

On February 28, 2018, Rare Disease Day will be observed around the world. This annual observance is intended to promote awareness of the 7,000 diseases considered rare in the US, the need for research and clinical guidelines, and the challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of life for patients. Educational events are planned at numerous hospitals, universities, schools, and community centers across the US. NORD will be hosting “State House Events” with patient advocates in more than 30 states to educate state legislators on issues related to state policy. Visit the national website hosted by NORD. Visit the international website.

On February 28, 2018, Rare Disease Day will be observed around the world. This annual observance is intended to promote awareness of the 7,000 diseases considered rare in the US, the need for research and clinical guidelines, and the challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of life for patients. Educational events are planned at numerous hospitals, universities, schools, and community centers across the US. NORD will be hosting “State House Events” with patient advocates in more than 30 states to educate state legislators on issues related to state policy. Visit the national website hosted by NORD. Visit the international website.

NORD to Moderate Panel at NIH Rare Disease Day Event

NORD Board Chair Marshall Summar, MD, of Children’s National Health System, will moderate a panel on the importance of collaborating with patient organizations in rare disease research at the annual National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Disease Day event on March 1, 2018. The event is open to the public and will be webcast. Other speakers will include NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD; representatives of the Rare Disease Congressional Caucus; NIH researchers; and leaders of patient organizations. Topics will include gene therapy, gene editing, and engaging the next generation of the rare diseases community. For information or to register, visit the NIH web page.

NORD Board Chair Marshall Summar, MD, of Children’s National Health System, will moderate a panel on the importance of collaborating with patient organizations in rare disease research at the annual National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Disease Day event on March 1, 2018. The event is open to the public and will be webcast. Other speakers will include NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD; representatives of the Rare Disease Congressional Caucus; NIH researchers; and leaders of patient organizations. Topics will include gene therapy, gene editing, and engaging the next generation of the rare diseases community. For information or to register, visit the NIH web page.

NORD Board Chair Marshall Summar, MD, of Children’s National Health System, will moderate a panel on the importance of collaborating with patient organizations in rare disease research at the annual National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Disease Day event on March 1, 2018. The event is open to the public and will be webcast. Other speakers will include NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD; representatives of the Rare Disease Congressional Caucus; NIH researchers; and leaders of patient organizations. Topics will include gene therapy, gene editing, and engaging the next generation of the rare diseases community. For information or to register, visit the NIH web page.