User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

When your patient is a physician: Overcoming the challenges

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Mobile apps and mental health: Using technology to quantify real-time clinical risk

In today’s global society, smartphones are ubiquitous, used by >2.5 billion people.1 They provide limitless availability of on-demand services and resources, unparalleled computing power by size, and the ability to connect with anyone in the world.

Digital applications and new mobile technologies can be used to change the nature of the psychiatrist–patient relationship. The future of clinical practice is changing with the help of smartphones and apps. Diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment will never look the same as we come to better understand and apply emerging technologies.2

Both Android and iOS—the 2 largest mobile operating systems by market share3—provide outlets for the dissemination of mobile applications. There are currently >10,000 mental health–related apps available for download.4 One particular use case of mental health–related apps is digital phenotyping.

In this article, we aim to:

- define digital phenotyping

- explore the potential advances in patient care afforded by emerging technology

- discuss the ethical dilemmas and future of mental health apps.

The possibilities of digital phenotyping

Digital phenotyping is capturing a patient’s real-time clinical state using digital technology to better understand the patient’s state outside of the clinic. While digital phenotyping may seem new, the concepts behind it are grounded in good clinical care.

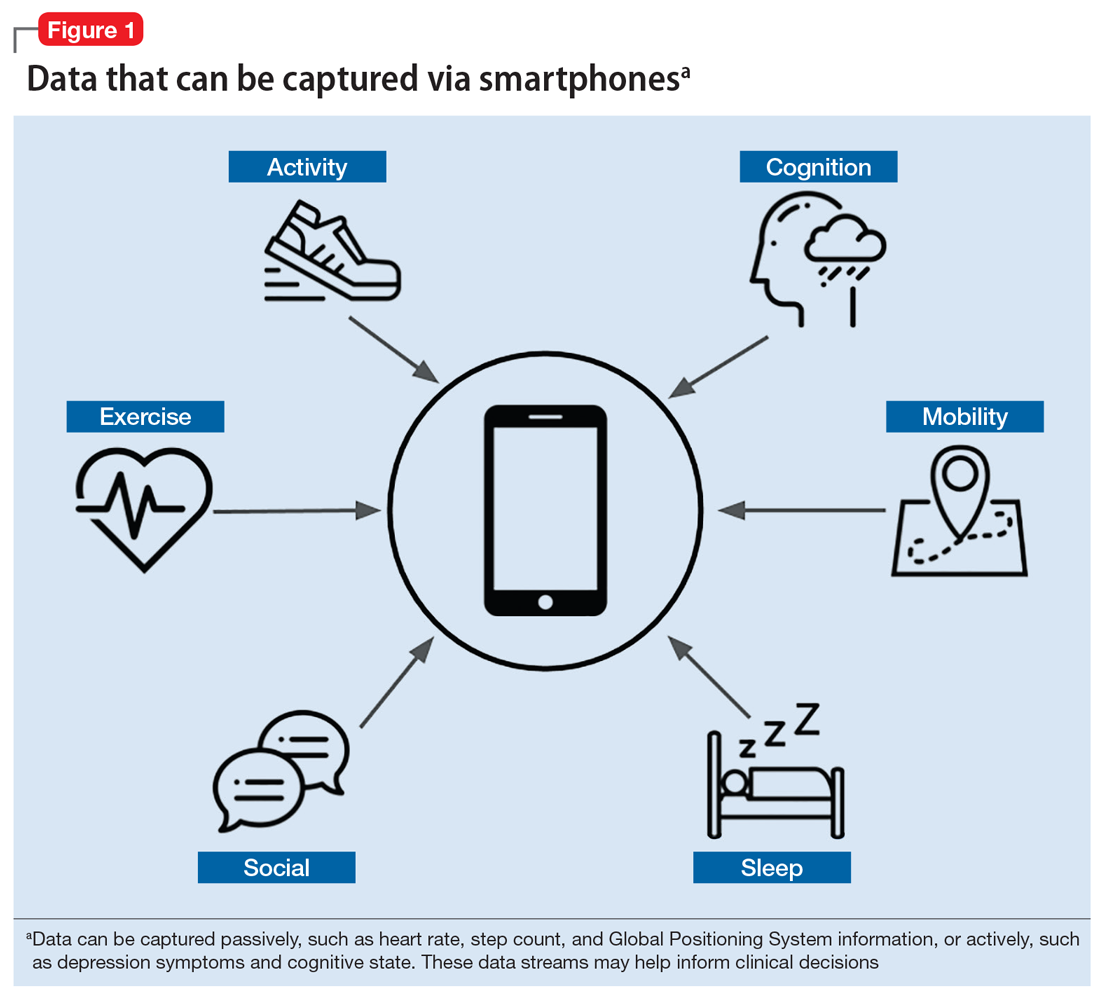

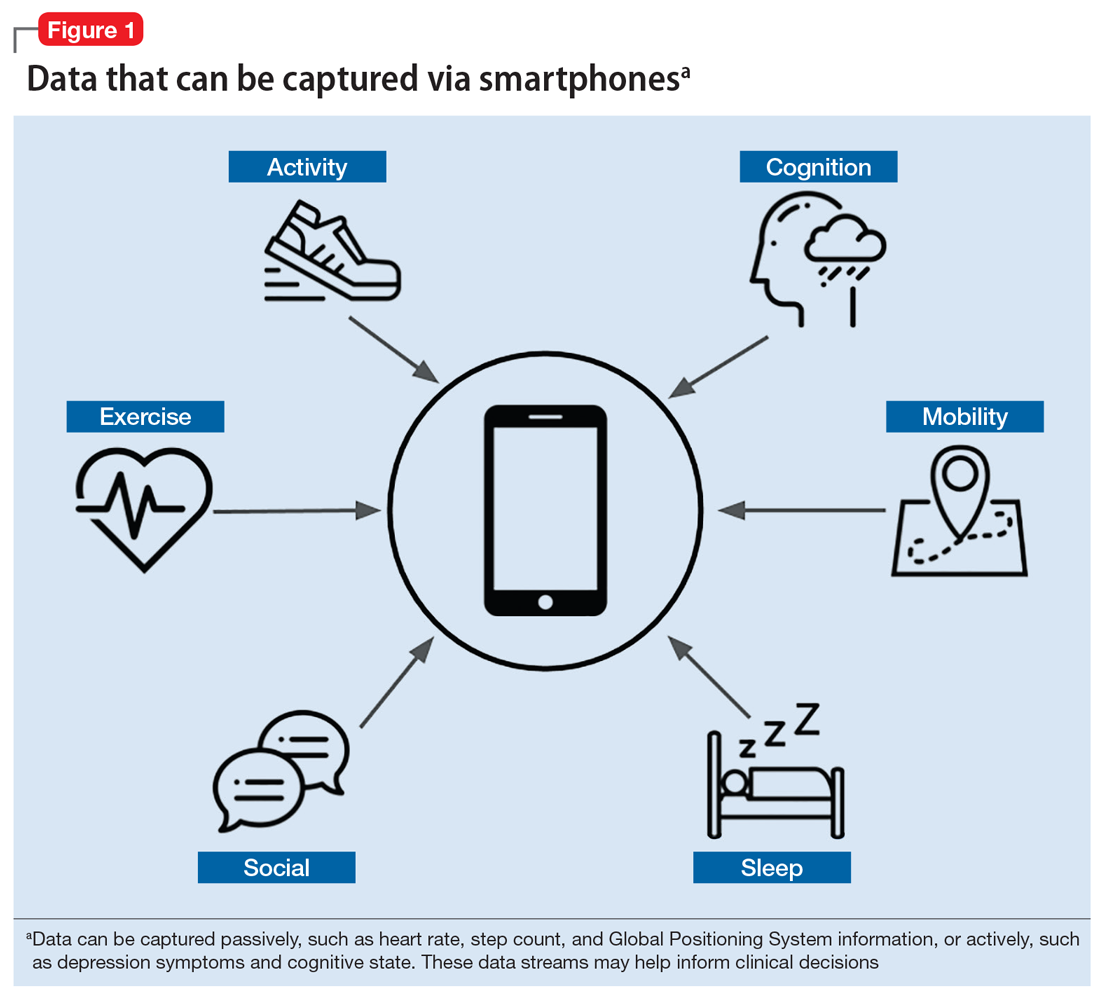

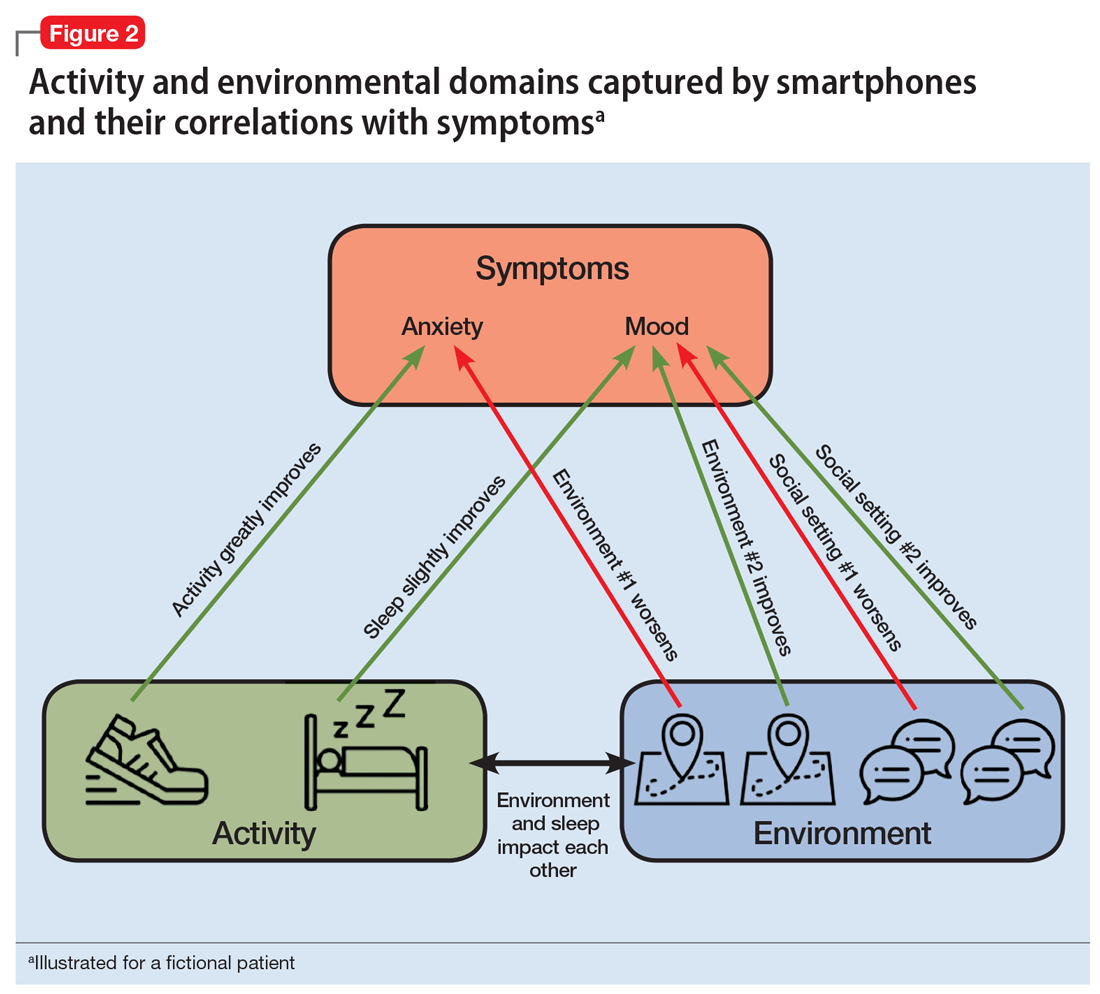

For example, it is important to assess sleep and physical activity for nearly all patients, regardless of diagnosis. However, the patient’s retrospective recollection of sleep, mood, and other clinically relevant metrics is often unreliable, especially when visits are months apart. With smartphones, it is possible to automatically collect metrics for sleep, activity, mood, and much more in real time from the convenience of our patients’ personal devices (Figure 1).

Smartphones can capture a seemingly endless number of data streams, from patient-interfacing active data, such as journal entries, messaging, and games, to data that is captured passively, such as screen time, Global Positioning System information, and step count. Clinicians can work with patients to customize which digital phenotyping data they would like to capture. In one study, researchers worked with 17 patients with schizophrenia by capturing self-reported surveys, anonymized phone call logs, and location data to see if they could predict relapse by observing variations in how patients interact with their smartphones.5 They observed that the rate of behavioral anomalies was 71% higher in the 2 weeks prior to relapse than during other periods. The data captured by the smartphone will depend on the patient and the clinical needs. Some clinicians may only want to collect data on step count and screen time to learn if a patient is overusing his or her smartphone, which might be related to becoming less physically active.

Continue to: One novel data stream...

One novel data stream offered by smartphone digital phenotyping is cognition. While we know that impaired cognition is a core symptom of schizophrenia, and that cognition is affected by depression and anxiety, cognitive symptoms are clinically challenging to quantify. Thus, the cognitive burden of mental illness and the cognitive effects of treatment are often overlooked. However, smartphones are beginning to offer a novel means of capturing a patient’s cognitive state through the use of common clinical tests. For example, the Trail Making Test measures visual attention and executive function by having participants connect dots that differ in number, color, or shape in an ascending pattern.6 By having patients perform this test on a smartphone, clinicians can utilize the touchscreen to capture the user’s discrete actions, such as time to completion and misclicks. These data can be used to build novel measures of cognitive performance that can account for learning bias and other confounding variables.7 While these digital cognitive biomarkers are still in active research, it is likely that they will quickly be developed for broad clinical use.

In addition to the novel data offered by digital phenotyping, another benefit is the low cost and ease of use. Unlike wearable devices such as smartwatches, which can also offer data on steps and sleep, smartphone-based digital phenotyping does not require patients to purchase or use additional devices. Running on patients’ smartphones, digital phenotyping offers the ability to capture rich and continuous health data without added effort or cost. Given that the average person interacts with their phone more than 2,600 times per day,8 smartphones are well suited for capturing large amounts of information that may provide insights into patients’ mental health.

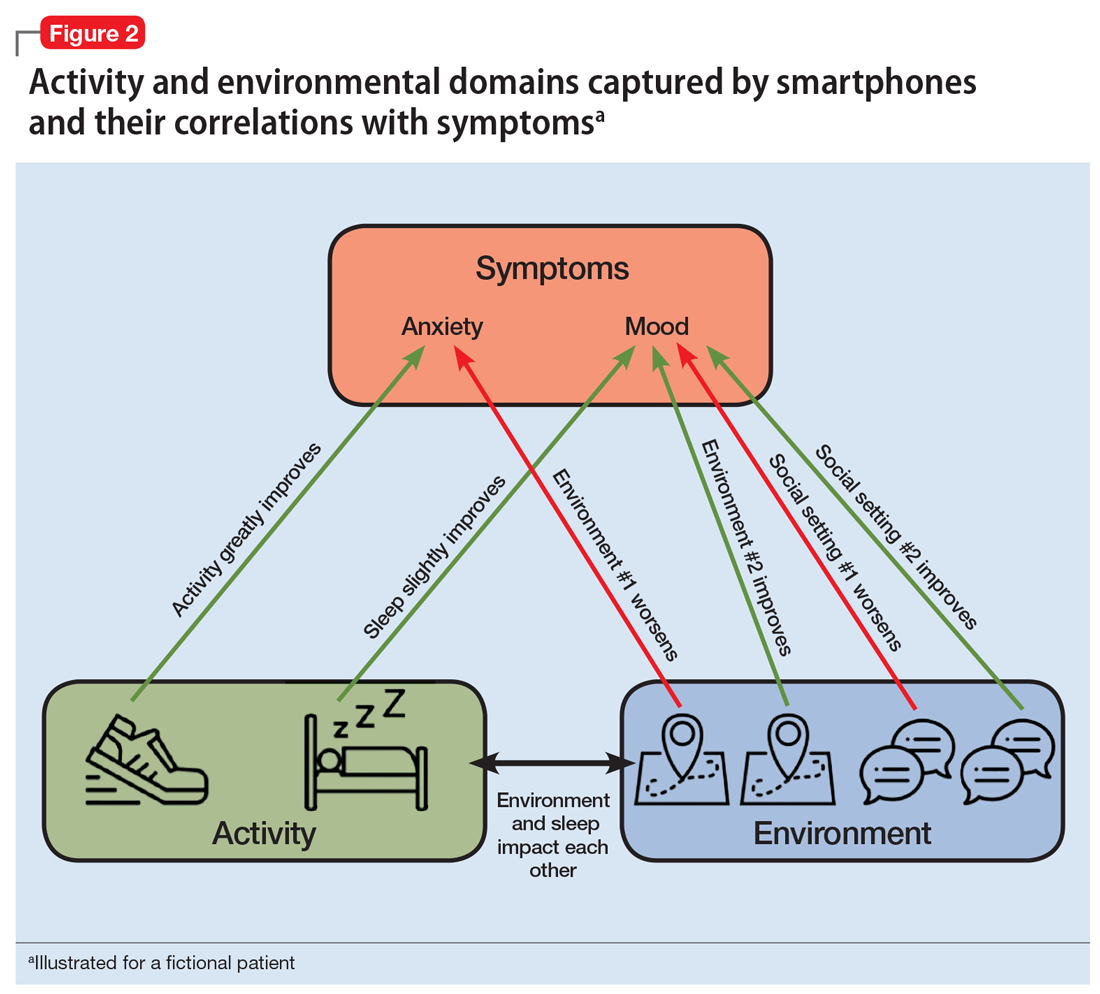

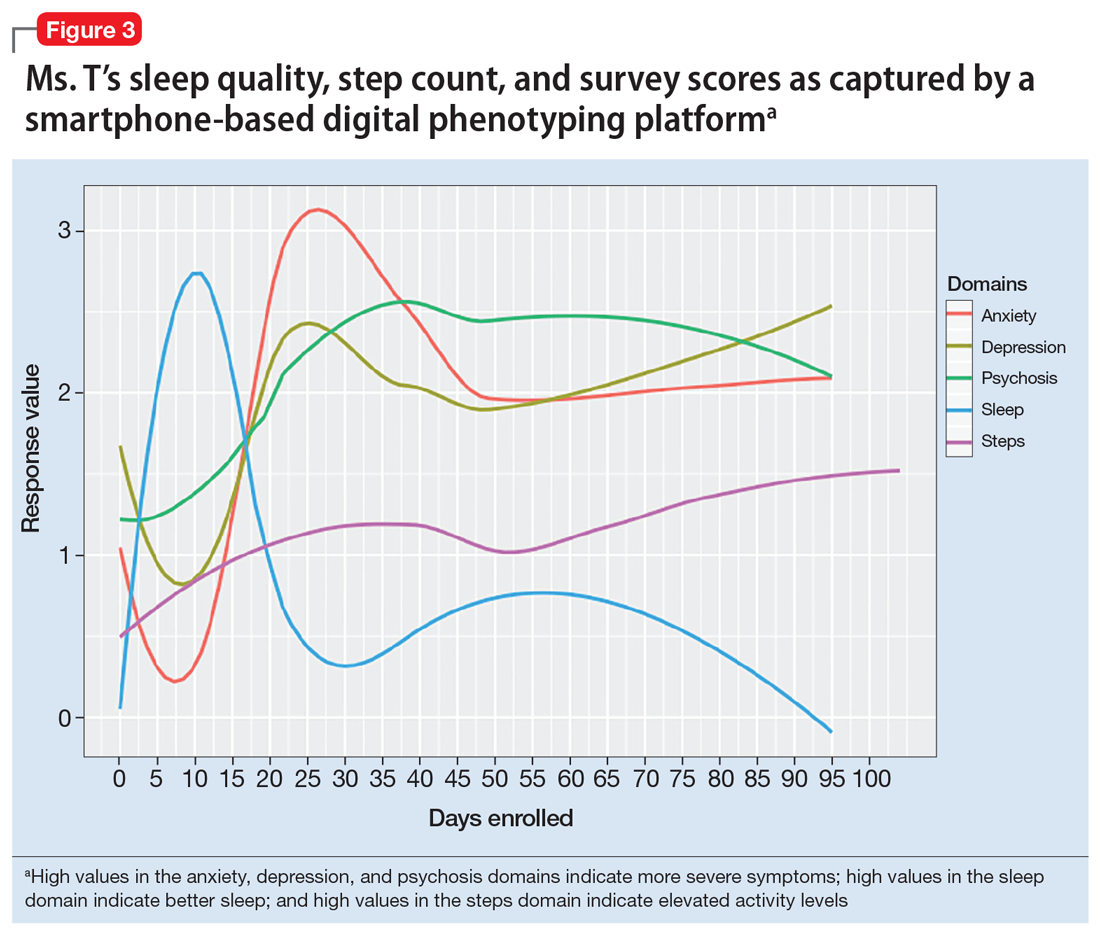

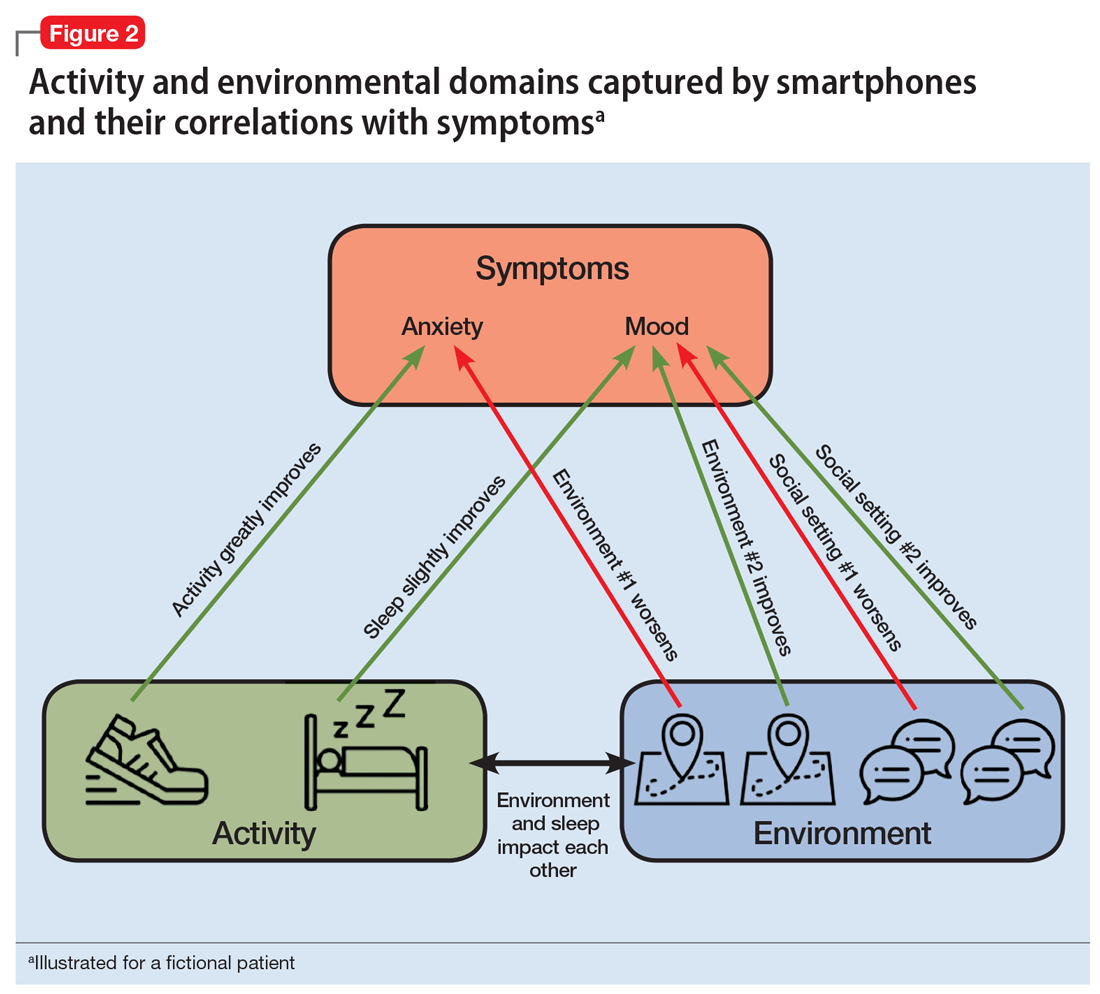

For illnesses such as depression and anxiety, the clinical relevance of digital phenotyping is in the ability to capture symptoms as they occur in context. Figure 2 provides a simplified example of how we can learn that for this fictitious patient, exercise greatly improves anxiety, whereas being in a certain environment worsens it. Other insights about sleep and social settings could also provide further information about the context of the patient’s symptoms. While these correlations alone will not lead to better clinical outcomes, it is easy to imagine how such data could help a patient and clinician start a conversation about making impactful changes.

Continue to: Case report...

Case report: Digital phenotyping

To illustrate how digital phenotyping could be put to clinical use, we created the following case report of a fictional patient who agrees to be monitored via her smartphone.

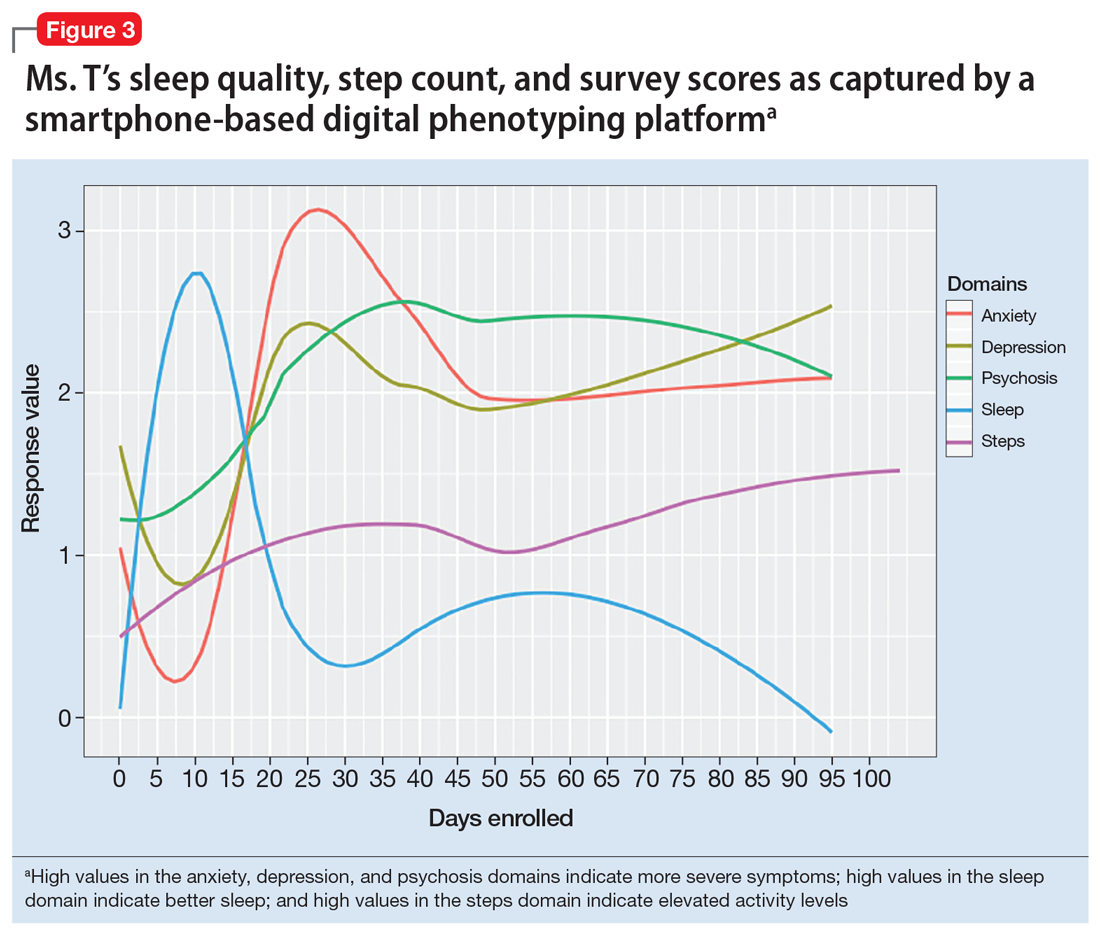

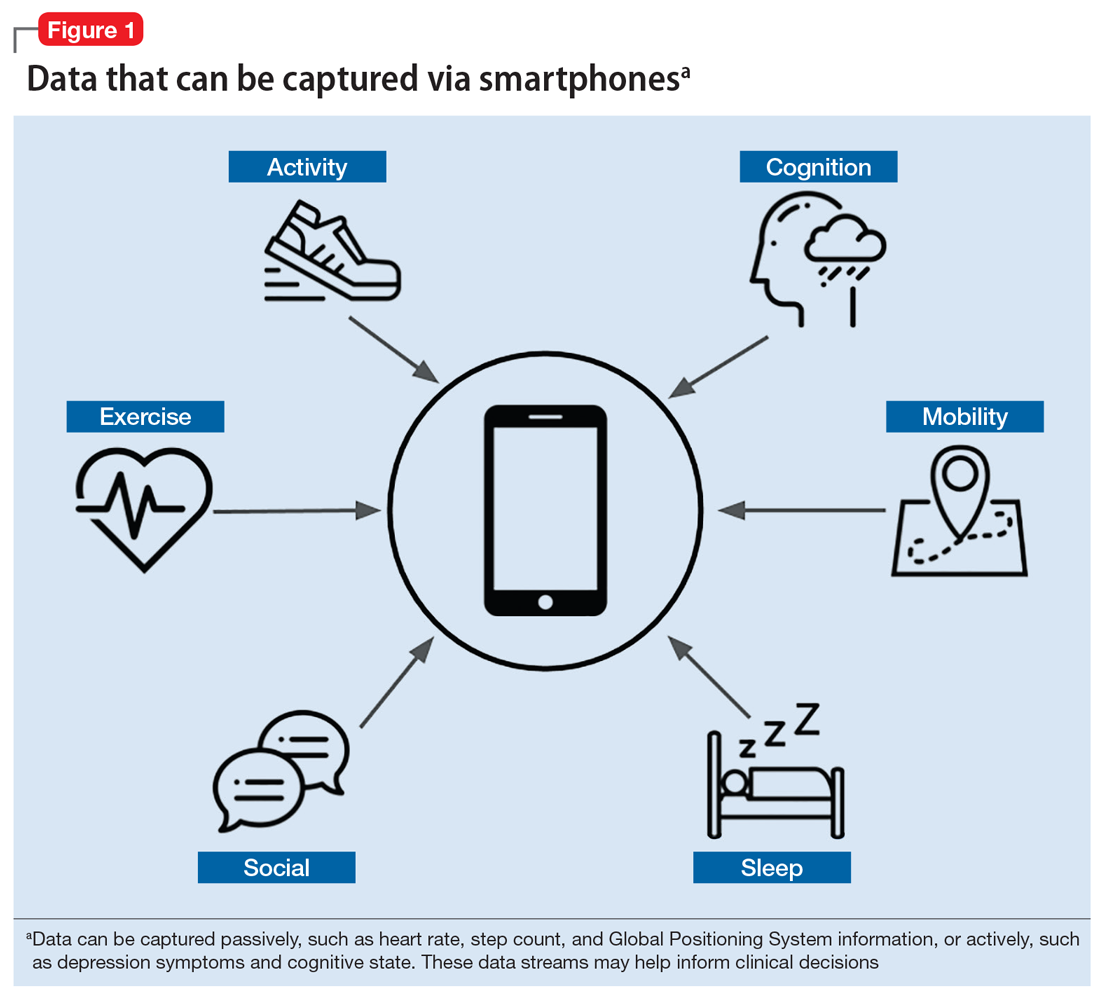

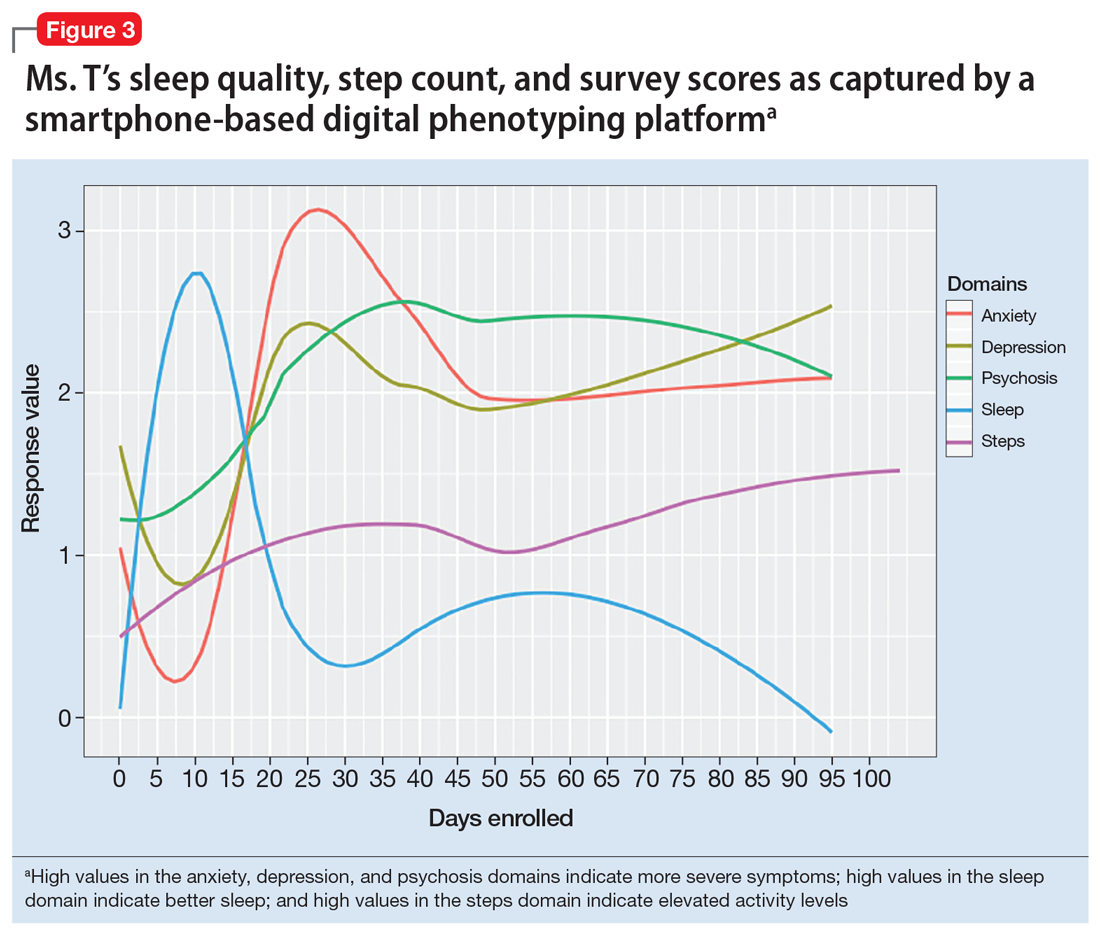

Consider a hypothetical patient we will call Ms. T who is in her mid-20s and has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. On a follow-up visit, she says she has insomnia. She also reports having a recent loss of appetite and higher levels of anxiety. After reviewing her smartphone data (Figure 3), the clinician sees an inversely proportional relationship between her sleep quality and symptoms of anxiety, psychosis, and depression, which suggests that these symptoms might be due to poor sleep. Her step count has been fairly stable, indicating that there is no significant correlation between physical activity and her other symptoms.

Continue to: The clinician shows...

The clinician shows Ms. T the data to help her understand why a trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, or at least improving sleep hygiene, may offer several benefits. The clinician advises her to continue to use the app to help assess her response to these interventions and monitor her progress in real time.

Dilemma: The ethics of continuous observation

The rich data captured by digital phenotyping afford many clinical opportunities, but also raise concerns. Among these are 3 significant ethical implications.

Firstly, the same data that may help a clinician learn about what environments are associated with less anxiety for the patient may also reveal personal details about where that patient has been or with whom they have interacted. In the wrong hands, such personal data could cause harm. And even in the hands of a trusted clinician, a breach in the patient’s privacy begs the question: “Should such information be anyone’s business at all?”

Secondly, many apps that offer digital phenotyping could also store patient data—something that currently pervades social media and causes reasonable discomfort for many people. You might have personally encountered this with social media platforms such as Facebook. When it comes to mobile mental health apps, clinicians should carefully understand the data usage agreement of any digital phenotyping app they wish to use and then share this information with their patients.

Finally, while it is possible to collect the types of data outlined in this article, less is known about how to use it directly in clinical care. Understanding for each patient which data streams are most meaningful and which data streams are noise that should be ignored is an area of ongoing research. A good first step may be to begin with data streams that are known to be clinically relevant and valuable, such as sleep and physical activity.9-11

Continue to: Discussion...

Discussion: Genomic sequencing and digital phenotyping

Although smartphones can gather a wide range of active and passive data, other data streams hold potential for predicting relapse and performing other clinically relevant actions. One data stream that could be of clinical use is genomic sequencing.12 The genotyping of patients provides a wealth of information about the underlying biology, and genomic sequencing has never been cheaper.13

Combining the data gathered via digital phenotyping with that of genotyping could help elucidate the mechanisms by which specific diseases and symptoms occur. This could be very promising to better understand and treat our patients. However, as is the case with genomics, digital phenotyping has important ethical implications. If used in the proper way to benefit our patients, the future for this new method is bright.

1. Statista. Number of smartphone users worldwide from 2014 to 2020 (in billions). https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/. Accessed April 29, 2019.

2. Thibaut F. Digital applications: the future in psychiatry? Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18(2):123.

3. Statista. Global market share held by the leading smartphone operating systems in sales to end users from 1st quarter 2009 to 2nd quarter 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/266136/global-market-share-held-by-smartphone-operating-systems/. Accessed April 19, 2019.

4. Torous J, Roberts L. Needed innovation in digital health and smartphone applications for mental health: transparency and trust. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):437-438.

5. Barnett I, Torous J, Staples P, et al. Relapse prediction in schizophrenia through digital phenotyping: a pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(8):1660-1666.

6. Arnett JA, Labovitz SS. Effect of physical layout in performance of the Trail Making Test. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(2):220-221.

7. Brouillette RM, Foil H, Fontenot S, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of a smartphone based application for the assessment of cognitive function in the elderly. PloS One. 2013;8(6):e65925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065925.

8. Winnick W. Putting a finger on our phone obsession. dscout. https://blog.dscout.com/mobile-touches. Published June 16, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2019.

9. Waite F, Myers E, Harvey AG, et al. Treating sleep problems in patients with schizophrenia. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2016;44(3):273-287.

10. Mcgurk SR, Mueser KT, Xie H, et al. (2015). Cognitive enhancement treatment for people with mental illness who do not respond to supported employment: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):852-861.

11. Firth J, Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognitive functioning in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(3):546-556.

12. Manolio TA, Chisholm RL, Ozenberger B, et al. Implementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is here. Genet Med. 2013;15(4):258-267.

13. National Human Genome Research Institute. The cost of sequencing a human genome. https://www.genome.gov/27565109/the-cost-of-sequencing-a-human-genome/. Updated July 6, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2019.

In today’s global society, smartphones are ubiquitous, used by >2.5 billion people.1 They provide limitless availability of on-demand services and resources, unparalleled computing power by size, and the ability to connect with anyone in the world.

Digital applications and new mobile technologies can be used to change the nature of the psychiatrist–patient relationship. The future of clinical practice is changing with the help of smartphones and apps. Diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment will never look the same as we come to better understand and apply emerging technologies.2

Both Android and iOS—the 2 largest mobile operating systems by market share3—provide outlets for the dissemination of mobile applications. There are currently >10,000 mental health–related apps available for download.4 One particular use case of mental health–related apps is digital phenotyping.

In this article, we aim to:

- define digital phenotyping

- explore the potential advances in patient care afforded by emerging technology

- discuss the ethical dilemmas and future of mental health apps.

The possibilities of digital phenotyping

Digital phenotyping is capturing a patient’s real-time clinical state using digital technology to better understand the patient’s state outside of the clinic. While digital phenotyping may seem new, the concepts behind it are grounded in good clinical care.

For example, it is important to assess sleep and physical activity for nearly all patients, regardless of diagnosis. However, the patient’s retrospective recollection of sleep, mood, and other clinically relevant metrics is often unreliable, especially when visits are months apart. With smartphones, it is possible to automatically collect metrics for sleep, activity, mood, and much more in real time from the convenience of our patients’ personal devices (Figure 1).

Smartphones can capture a seemingly endless number of data streams, from patient-interfacing active data, such as journal entries, messaging, and games, to data that is captured passively, such as screen time, Global Positioning System information, and step count. Clinicians can work with patients to customize which digital phenotyping data they would like to capture. In one study, researchers worked with 17 patients with schizophrenia by capturing self-reported surveys, anonymized phone call logs, and location data to see if they could predict relapse by observing variations in how patients interact with their smartphones.5 They observed that the rate of behavioral anomalies was 71% higher in the 2 weeks prior to relapse than during other periods. The data captured by the smartphone will depend on the patient and the clinical needs. Some clinicians may only want to collect data on step count and screen time to learn if a patient is overusing his or her smartphone, which might be related to becoming less physically active.

Continue to: One novel data stream...

One novel data stream offered by smartphone digital phenotyping is cognition. While we know that impaired cognition is a core symptom of schizophrenia, and that cognition is affected by depression and anxiety, cognitive symptoms are clinically challenging to quantify. Thus, the cognitive burden of mental illness and the cognitive effects of treatment are often overlooked. However, smartphones are beginning to offer a novel means of capturing a patient’s cognitive state through the use of common clinical tests. For example, the Trail Making Test measures visual attention and executive function by having participants connect dots that differ in number, color, or shape in an ascending pattern.6 By having patients perform this test on a smartphone, clinicians can utilize the touchscreen to capture the user’s discrete actions, such as time to completion and misclicks. These data can be used to build novel measures of cognitive performance that can account for learning bias and other confounding variables.7 While these digital cognitive biomarkers are still in active research, it is likely that they will quickly be developed for broad clinical use.

In addition to the novel data offered by digital phenotyping, another benefit is the low cost and ease of use. Unlike wearable devices such as smartwatches, which can also offer data on steps and sleep, smartphone-based digital phenotyping does not require patients to purchase or use additional devices. Running on patients’ smartphones, digital phenotyping offers the ability to capture rich and continuous health data without added effort or cost. Given that the average person interacts with their phone more than 2,600 times per day,8 smartphones are well suited for capturing large amounts of information that may provide insights into patients’ mental health.

For illnesses such as depression and anxiety, the clinical relevance of digital phenotyping is in the ability to capture symptoms as they occur in context. Figure 2 provides a simplified example of how we can learn that for this fictitious patient, exercise greatly improves anxiety, whereas being in a certain environment worsens it. Other insights about sleep and social settings could also provide further information about the context of the patient’s symptoms. While these correlations alone will not lead to better clinical outcomes, it is easy to imagine how such data could help a patient and clinician start a conversation about making impactful changes.

Continue to: Case report...

Case report: Digital phenotyping

To illustrate how digital phenotyping could be put to clinical use, we created the following case report of a fictional patient who agrees to be monitored via her smartphone.

Consider a hypothetical patient we will call Ms. T who is in her mid-20s and has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. On a follow-up visit, she says she has insomnia. She also reports having a recent loss of appetite and higher levels of anxiety. After reviewing her smartphone data (Figure 3), the clinician sees an inversely proportional relationship between her sleep quality and symptoms of anxiety, psychosis, and depression, which suggests that these symptoms might be due to poor sleep. Her step count has been fairly stable, indicating that there is no significant correlation between physical activity and her other symptoms.

Continue to: The clinician shows...

The clinician shows Ms. T the data to help her understand why a trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, or at least improving sleep hygiene, may offer several benefits. The clinician advises her to continue to use the app to help assess her response to these interventions and monitor her progress in real time.

Dilemma: The ethics of continuous observation

The rich data captured by digital phenotyping afford many clinical opportunities, but also raise concerns. Among these are 3 significant ethical implications.

Firstly, the same data that may help a clinician learn about what environments are associated with less anxiety for the patient may also reveal personal details about where that patient has been or with whom they have interacted. In the wrong hands, such personal data could cause harm. And even in the hands of a trusted clinician, a breach in the patient’s privacy begs the question: “Should such information be anyone’s business at all?”

Secondly, many apps that offer digital phenotyping could also store patient data—something that currently pervades social media and causes reasonable discomfort for many people. You might have personally encountered this with social media platforms such as Facebook. When it comes to mobile mental health apps, clinicians should carefully understand the data usage agreement of any digital phenotyping app they wish to use and then share this information with their patients.

Finally, while it is possible to collect the types of data outlined in this article, less is known about how to use it directly in clinical care. Understanding for each patient which data streams are most meaningful and which data streams are noise that should be ignored is an area of ongoing research. A good first step may be to begin with data streams that are known to be clinically relevant and valuable, such as sleep and physical activity.9-11

Continue to: Discussion...

Discussion: Genomic sequencing and digital phenotyping

Although smartphones can gather a wide range of active and passive data, other data streams hold potential for predicting relapse and performing other clinically relevant actions. One data stream that could be of clinical use is genomic sequencing.12 The genotyping of patients provides a wealth of information about the underlying biology, and genomic sequencing has never been cheaper.13

Combining the data gathered via digital phenotyping with that of genotyping could help elucidate the mechanisms by which specific diseases and symptoms occur. This could be very promising to better understand and treat our patients. However, as is the case with genomics, digital phenotyping has important ethical implications. If used in the proper way to benefit our patients, the future for this new method is bright.

In today’s global society, smartphones are ubiquitous, used by >2.5 billion people.1 They provide limitless availability of on-demand services and resources, unparalleled computing power by size, and the ability to connect with anyone in the world.

Digital applications and new mobile technologies can be used to change the nature of the psychiatrist–patient relationship. The future of clinical practice is changing with the help of smartphones and apps. Diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment will never look the same as we come to better understand and apply emerging technologies.2

Both Android and iOS—the 2 largest mobile operating systems by market share3—provide outlets for the dissemination of mobile applications. There are currently >10,000 mental health–related apps available for download.4 One particular use case of mental health–related apps is digital phenotyping.

In this article, we aim to:

- define digital phenotyping

- explore the potential advances in patient care afforded by emerging technology

- discuss the ethical dilemmas and future of mental health apps.

The possibilities of digital phenotyping

Digital phenotyping is capturing a patient’s real-time clinical state using digital technology to better understand the patient’s state outside of the clinic. While digital phenotyping may seem new, the concepts behind it are grounded in good clinical care.

For example, it is important to assess sleep and physical activity for nearly all patients, regardless of diagnosis. However, the patient’s retrospective recollection of sleep, mood, and other clinically relevant metrics is often unreliable, especially when visits are months apart. With smartphones, it is possible to automatically collect metrics for sleep, activity, mood, and much more in real time from the convenience of our patients’ personal devices (Figure 1).

Smartphones can capture a seemingly endless number of data streams, from patient-interfacing active data, such as journal entries, messaging, and games, to data that is captured passively, such as screen time, Global Positioning System information, and step count. Clinicians can work with patients to customize which digital phenotyping data they would like to capture. In one study, researchers worked with 17 patients with schizophrenia by capturing self-reported surveys, anonymized phone call logs, and location data to see if they could predict relapse by observing variations in how patients interact with their smartphones.5 They observed that the rate of behavioral anomalies was 71% higher in the 2 weeks prior to relapse than during other periods. The data captured by the smartphone will depend on the patient and the clinical needs. Some clinicians may only want to collect data on step count and screen time to learn if a patient is overusing his or her smartphone, which might be related to becoming less physically active.

Continue to: One novel data stream...

One novel data stream offered by smartphone digital phenotyping is cognition. While we know that impaired cognition is a core symptom of schizophrenia, and that cognition is affected by depression and anxiety, cognitive symptoms are clinically challenging to quantify. Thus, the cognitive burden of mental illness and the cognitive effects of treatment are often overlooked. However, smartphones are beginning to offer a novel means of capturing a patient’s cognitive state through the use of common clinical tests. For example, the Trail Making Test measures visual attention and executive function by having participants connect dots that differ in number, color, or shape in an ascending pattern.6 By having patients perform this test on a smartphone, clinicians can utilize the touchscreen to capture the user’s discrete actions, such as time to completion and misclicks. These data can be used to build novel measures of cognitive performance that can account for learning bias and other confounding variables.7 While these digital cognitive biomarkers are still in active research, it is likely that they will quickly be developed for broad clinical use.

In addition to the novel data offered by digital phenotyping, another benefit is the low cost and ease of use. Unlike wearable devices such as smartwatches, which can also offer data on steps and sleep, smartphone-based digital phenotyping does not require patients to purchase or use additional devices. Running on patients’ smartphones, digital phenotyping offers the ability to capture rich and continuous health data without added effort or cost. Given that the average person interacts with their phone more than 2,600 times per day,8 smartphones are well suited for capturing large amounts of information that may provide insights into patients’ mental health.

For illnesses such as depression and anxiety, the clinical relevance of digital phenotyping is in the ability to capture symptoms as they occur in context. Figure 2 provides a simplified example of how we can learn that for this fictitious patient, exercise greatly improves anxiety, whereas being in a certain environment worsens it. Other insights about sleep and social settings could also provide further information about the context of the patient’s symptoms. While these correlations alone will not lead to better clinical outcomes, it is easy to imagine how such data could help a patient and clinician start a conversation about making impactful changes.

Continue to: Case report...

Case report: Digital phenotyping

To illustrate how digital phenotyping could be put to clinical use, we created the following case report of a fictional patient who agrees to be monitored via her smartphone.

Consider a hypothetical patient we will call Ms. T who is in her mid-20s and has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. On a follow-up visit, she says she has insomnia. She also reports having a recent loss of appetite and higher levels of anxiety. After reviewing her smartphone data (Figure 3), the clinician sees an inversely proportional relationship between her sleep quality and symptoms of anxiety, psychosis, and depression, which suggests that these symptoms might be due to poor sleep. Her step count has been fairly stable, indicating that there is no significant correlation between physical activity and her other symptoms.

Continue to: The clinician shows...

The clinician shows Ms. T the data to help her understand why a trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, or at least improving sleep hygiene, may offer several benefits. The clinician advises her to continue to use the app to help assess her response to these interventions and monitor her progress in real time.

Dilemma: The ethics of continuous observation

The rich data captured by digital phenotyping afford many clinical opportunities, but also raise concerns. Among these are 3 significant ethical implications.

Firstly, the same data that may help a clinician learn about what environments are associated with less anxiety for the patient may also reveal personal details about where that patient has been or with whom they have interacted. In the wrong hands, such personal data could cause harm. And even in the hands of a trusted clinician, a breach in the patient’s privacy begs the question: “Should such information be anyone’s business at all?”

Secondly, many apps that offer digital phenotyping could also store patient data—something that currently pervades social media and causes reasonable discomfort for many people. You might have personally encountered this with social media platforms such as Facebook. When it comes to mobile mental health apps, clinicians should carefully understand the data usage agreement of any digital phenotyping app they wish to use and then share this information with their patients.

Finally, while it is possible to collect the types of data outlined in this article, less is known about how to use it directly in clinical care. Understanding for each patient which data streams are most meaningful and which data streams are noise that should be ignored is an area of ongoing research. A good first step may be to begin with data streams that are known to be clinically relevant and valuable, such as sleep and physical activity.9-11

Continue to: Discussion...

Discussion: Genomic sequencing and digital phenotyping

Although smartphones can gather a wide range of active and passive data, other data streams hold potential for predicting relapse and performing other clinically relevant actions. One data stream that could be of clinical use is genomic sequencing.12 The genotyping of patients provides a wealth of information about the underlying biology, and genomic sequencing has never been cheaper.13

Combining the data gathered via digital phenotyping with that of genotyping could help elucidate the mechanisms by which specific diseases and symptoms occur. This could be very promising to better understand and treat our patients. However, as is the case with genomics, digital phenotyping has important ethical implications. If used in the proper way to benefit our patients, the future for this new method is bright.

1. Statista. Number of smartphone users worldwide from 2014 to 2020 (in billions). https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/. Accessed April 29, 2019.

2. Thibaut F. Digital applications: the future in psychiatry? Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18(2):123.

3. Statista. Global market share held by the leading smartphone operating systems in sales to end users from 1st quarter 2009 to 2nd quarter 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/266136/global-market-share-held-by-smartphone-operating-systems/. Accessed April 19, 2019.

4. Torous J, Roberts L. Needed innovation in digital health and smartphone applications for mental health: transparency and trust. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):437-438.

5. Barnett I, Torous J, Staples P, et al. Relapse prediction in schizophrenia through digital phenotyping: a pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(8):1660-1666.

6. Arnett JA, Labovitz SS. Effect of physical layout in performance of the Trail Making Test. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(2):220-221.

7. Brouillette RM, Foil H, Fontenot S, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of a smartphone based application for the assessment of cognitive function in the elderly. PloS One. 2013;8(6):e65925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065925.

8. Winnick W. Putting a finger on our phone obsession. dscout. https://blog.dscout.com/mobile-touches. Published June 16, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2019.

9. Waite F, Myers E, Harvey AG, et al. Treating sleep problems in patients with schizophrenia. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2016;44(3):273-287.

10. Mcgurk SR, Mueser KT, Xie H, et al. (2015). Cognitive enhancement treatment for people with mental illness who do not respond to supported employment: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):852-861.

11. Firth J, Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognitive functioning in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(3):546-556.

12. Manolio TA, Chisholm RL, Ozenberger B, et al. Implementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is here. Genet Med. 2013;15(4):258-267.

13. National Human Genome Research Institute. The cost of sequencing a human genome. https://www.genome.gov/27565109/the-cost-of-sequencing-a-human-genome/. Updated July 6, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2019.

1. Statista. Number of smartphone users worldwide from 2014 to 2020 (in billions). https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/. Accessed April 29, 2019.

2. Thibaut F. Digital applications: the future in psychiatry? Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18(2):123.

3. Statista. Global market share held by the leading smartphone operating systems in sales to end users from 1st quarter 2009 to 2nd quarter 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/266136/global-market-share-held-by-smartphone-operating-systems/. Accessed April 19, 2019.

4. Torous J, Roberts L. Needed innovation in digital health and smartphone applications for mental health: transparency and trust. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):437-438.

5. Barnett I, Torous J, Staples P, et al. Relapse prediction in schizophrenia through digital phenotyping: a pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(8):1660-1666.

6. Arnett JA, Labovitz SS. Effect of physical layout in performance of the Trail Making Test. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(2):220-221.

7. Brouillette RM, Foil H, Fontenot S, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of a smartphone based application for the assessment of cognitive function in the elderly. PloS One. 2013;8(6):e65925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065925.

8. Winnick W. Putting a finger on our phone obsession. dscout. https://blog.dscout.com/mobile-touches. Published June 16, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2019.

9. Waite F, Myers E, Harvey AG, et al. Treating sleep problems in patients with schizophrenia. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2016;44(3):273-287.

10. Mcgurk SR, Mueser KT, Xie H, et al. (2015). Cognitive enhancement treatment for people with mental illness who do not respond to supported employment: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):852-861.

11. Firth J, Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognitive functioning in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(3):546-556.

12. Manolio TA, Chisholm RL, Ozenberger B, et al. Implementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is here. Genet Med. 2013;15(4):258-267.

13. National Human Genome Research Institute. The cost of sequencing a human genome. https://www.genome.gov/27565109/the-cost-of-sequencing-a-human-genome/. Updated July 6, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2019.

It’s time to implement measurement-based care in psychiatric practice

In an editorial published in Current Psychiatry 10 years ago, I cited a stunning fact based on a readers’ survey: 98% of psychiatrists did not use any of the 4 clinical rating scales that are routinely used in the clinical trials required for FDA approval of medications for psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders.1

As a follow-up, Ahmed Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and I would like to report on the state of measurement-based care (MBC), a term coined by Trivedi in 2006 and defined by Fortney as “the systematic administration of symptom rating scales and use of the results to drive clinical decision making at the level of the individual patient.”2

We will start with the creator of modern rating scales, Father Thomas Verner Moore (1877-1969), who is considered one of the most underrecognized legends in the history of modern psychiatry. Moore was a psychologist and psychiatrist who can lay claim to 3 major achievements in psychiatry: the creation of rating scales in psychiatry, the use of factor analysis to deconstruct psychosis, and the formulation of specific definitions for symptoms and signs of psychopathology. Moore’s 1933 book described the rating scales used in his research.3

Since that time, researchers have continued to invent clinician-rated scales, self-report scales, and other measures in psychiatry. The Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, which was published in 2000 by the American Psychiatric Association Task Force chaired by AJ Rush Jr., includes >240 measures covering adult and child psychiatric disorders.4

Recent research has shown the superiority of MBC compared with usual standard care (USC) in improving patient outcomes.2,5-7 A recent well-designed, blind-rater, randomized trial by Guo et al8 showed that MBC is more effective than USC both in achieving response and remission, and reducing the time to response and remission. Given the evidence of the benefits of MBC in improving patient outcomes, and the plethora of reliable and validated rating scales, an important question arises: Why has MBC not yet been established as the standard of care in psychiatric clinical practice? There are many barriers to implementing MBC,9 including:

- time constraints (most commonly cited reason by psychiatrists)

- mismatch between clinical needs and the content of the measure (ie, rating scales are designed for research and not for clinicians’ use)

- measurements produced by rating scales may not always be clinically relevant

- administering rating scales may interfere with establishing rapport with patients

- some measures, such as standardized diagnostic interviews, can be cumbersome, unwieldy, and complicated

- the lack of formal training for most clinicians (among the top barriers for residents and faculty)

- lack of availability of training manuals and protocols.

Clinician researchers have started to adapt and invent instruments that can be used in clinical settings. For more than 20 years, Mark Zimmerman, MD, has been the principal investigator of the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project, aimed at integrating the assessment methods of researchers into routine clinical practice.10 Zimmerman has developed self-report scales and outcome measures such as the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ), the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS), the Standardized Clinical Outcome Rating for Depression (SCOR-D), the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale (CUXOS), the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ), and the Clinically Useful Patient Satisfaction Scale (CUPSS).11-18

We have been critical of the utility of the existing diagnostic interviews and rating scales. I (AA) developed the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) as a MBC tool that addresses the most common barriers that clinicians face.9,19-23 The SCIP includes 18 clinician-rated scales for the following symptom domains: generalized anxiety, obsessions, compulsions, posttraumatic stress, depression, mania, delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thoughts, aggression, negative symptoms, alcohol use, drug use, attention deficit, hyperactivity, anorexia, binge-eating, and bulimia. The SCIP rating scales meet the criteria for MBC because they are efficient, reliable, and valid. They reflect how clinicians assess psychiatric disorders, and are relevant to decision-making. Both self-report and clinician-rated scales are important MBC tools and complementary to each other. The choice to use self-report scales, clinician-rated scales, or both depends on several factors, including the clinical setting (inpatient or outpatient), psychiatric diagnoses, and patient characteristics. No measure or scale will ever replace a seasoned and experienced clinician who has been evaluating and treating real-world patients for years. Just as thermometers, stethoscopes, and laboratories help other types of physicians to reach accurate diagnoses and provide appropriate management, the use of MBC by psychiatrists will enhance the accuracy of diagnoses and improve the outcomes of care.

Continue to: On a positive note...

On a positive note, I (AA) have completed a MBC curriculum for training psychiatry residents that includes 11 videotaped interviews with actual patients covering the major adult psychiatric disorders: generalized anxiety, panic, depressive, posttraumatic stress, bipolar, psychotic, eating, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity. The interviews show and teach how to rate psychopathology items, how to score the dimensions, and how to evaluate the severity of the disorder(s). All of the SCIP’s 18 scales have been uploaded into the Epic electronic health record (EHR) system at West Virginia University hospitals. A pilot project for implementing MBC in the treatment of adult psychiatric disorders at the West Virginia University residency program and other programs is underway. If we instruct residents in MBC during their psychiatric training, they will likely practice it for the rest of their clinical careers. Except for a minority of clinicians who are involved in clinical trials and who use rating scales in practice, most practicing clinicians were never trained to use scales. For more information about the MBC curriculum and videotapes, contact Dr. Aboraya at [email protected] or visit www.scip-psychiatry.com.

Today, some of the barriers that impede the implementation of MBC in psychiatric practice have been resolved, but much more work remains. Now is the time to implement MBC and provide an answer to AJ Rush, who asked, “Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice?”24 The 3 main ingredients for MBC implementation—useful measures, integration of EHR, and health information technologies—exist today. We strongly encourage psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health professionals to adopt MBC in their daily practice.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Nasrallah HA. Long overdue: measurement-based psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(4):14-16.

2. Fortney JC, Unutzer J, Wrenn G, et al. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;68(2):179-188.

3. Moore TV. The essential psychoses and their fundamental syndromes. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1933.

4. Rush AJ. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

5. Scott K, Lewis CC. Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(1):49-59.

6. Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 2):S61-S71.

7. Harding KJ, Rush AJ, Arbuckle M, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: a policy framework for implementation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1136-1143.

8. Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, et al. Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):1004-1013.

9. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick D, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatry: past, present and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

10. Zimmerman M. A review of 20 years of research on overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(2):71-79.

11. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The reliability and validity of a screening questionnaire for 13 DSM-IV Axis I disorders (the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire) in psychiatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(10):677-683.

12. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: development, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(3):175-189.

13. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, McGlinchey JB, et al. A clinically useful depression outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):131-140.

14. Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, Chelminski I, et al. Standardized clinical outcome rating scale for depression for use in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22(1):36-40.

15. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D, et al. A clinically useful anxiety outcome scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):534-542.

16. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Attiullah N, et al. Depressed patients’ perspectives of 2 measures of outcome: the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) and the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ). Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2011;23(3):208-212.

17. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Attiullah N, et al. The remission from depression questionnaire as an outcome measure in the treatment of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(6):533-538.

18. Zimmerman M, Gazarian D, Multach M, et al. A clinically useful self-report measure of psychiatric patients’ satisfaction with the initial evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2017;252:38-44.

19. Aboraya A. The validity results of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP). Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015;41(Suppl 1):S103-S104.

20. Aboraya A. Instruction manual for the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP). http://innovationscns.com/wp-content/uploads/SCIP_Instruction_Manual.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2019.

21. Aboraya A, El-Missiry A, Barlowe J, et al. The reliability of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional and numeric output. Schizophr Res. 2014;156(2-3):174-183.

22. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Muvvala S, et al. The Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional, and numeric output-conceptual development, design, and description of the SCIP. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(5-6):31-77.

23. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA. Perspectives on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): Use, misuse, drawbacks, and a new alternative for schizophrenia research. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(2):125-131.

24. Rush AJ. Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice? Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):934-936.

In an editorial published in Current Psychiatry 10 years ago, I cited a stunning fact based on a readers’ survey: 98% of psychiatrists did not use any of the 4 clinical rating scales that are routinely used in the clinical trials required for FDA approval of medications for psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders.1

As a follow-up, Ahmed Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and I would like to report on the state of measurement-based care (MBC), a term coined by Trivedi in 2006 and defined by Fortney as “the systematic administration of symptom rating scales and use of the results to drive clinical decision making at the level of the individual patient.”2

We will start with the creator of modern rating scales, Father Thomas Verner Moore (1877-1969), who is considered one of the most underrecognized legends in the history of modern psychiatry. Moore was a psychologist and psychiatrist who can lay claim to 3 major achievements in psychiatry: the creation of rating scales in psychiatry, the use of factor analysis to deconstruct psychosis, and the formulation of specific definitions for symptoms and signs of psychopathology. Moore’s 1933 book described the rating scales used in his research.3

Since that time, researchers have continued to invent clinician-rated scales, self-report scales, and other measures in psychiatry. The Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, which was published in 2000 by the American Psychiatric Association Task Force chaired by AJ Rush Jr., includes >240 measures covering adult and child psychiatric disorders.4

Recent research has shown the superiority of MBC compared with usual standard care (USC) in improving patient outcomes.2,5-7 A recent well-designed, blind-rater, randomized trial by Guo et al8 showed that MBC is more effective than USC both in achieving response and remission, and reducing the time to response and remission. Given the evidence of the benefits of MBC in improving patient outcomes, and the plethora of reliable and validated rating scales, an important question arises: Why has MBC not yet been established as the standard of care in psychiatric clinical practice? There are many barriers to implementing MBC,9 including:

- time constraints (most commonly cited reason by psychiatrists)

- mismatch between clinical needs and the content of the measure (ie, rating scales are designed for research and not for clinicians’ use)

- measurements produced by rating scales may not always be clinically relevant

- administering rating scales may interfere with establishing rapport with patients

- some measures, such as standardized diagnostic interviews, can be cumbersome, unwieldy, and complicated

- the lack of formal training for most clinicians (among the top barriers for residents and faculty)

- lack of availability of training manuals and protocols.

Clinician researchers have started to adapt and invent instruments that can be used in clinical settings. For more than 20 years, Mark Zimmerman, MD, has been the principal investigator of the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project, aimed at integrating the assessment methods of researchers into routine clinical practice.10 Zimmerman has developed self-report scales and outcome measures such as the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ), the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS), the Standardized Clinical Outcome Rating for Depression (SCOR-D), the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale (CUXOS), the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ), and the Clinically Useful Patient Satisfaction Scale (CUPSS).11-18

We have been critical of the utility of the existing diagnostic interviews and rating scales. I (AA) developed the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) as a MBC tool that addresses the most common barriers that clinicians face.9,19-23 The SCIP includes 18 clinician-rated scales for the following symptom domains: generalized anxiety, obsessions, compulsions, posttraumatic stress, depression, mania, delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thoughts, aggression, negative symptoms, alcohol use, drug use, attention deficit, hyperactivity, anorexia, binge-eating, and bulimia. The SCIP rating scales meet the criteria for MBC because they are efficient, reliable, and valid. They reflect how clinicians assess psychiatric disorders, and are relevant to decision-making. Both self-report and clinician-rated scales are important MBC tools and complementary to each other. The choice to use self-report scales, clinician-rated scales, or both depends on several factors, including the clinical setting (inpatient or outpatient), psychiatric diagnoses, and patient characteristics. No measure or scale will ever replace a seasoned and experienced clinician who has been evaluating and treating real-world patients for years. Just as thermometers, stethoscopes, and laboratories help other types of physicians to reach accurate diagnoses and provide appropriate management, the use of MBC by psychiatrists will enhance the accuracy of diagnoses and improve the outcomes of care.

Continue to: On a positive note...

On a positive note, I (AA) have completed a MBC curriculum for training psychiatry residents that includes 11 videotaped interviews with actual patients covering the major adult psychiatric disorders: generalized anxiety, panic, depressive, posttraumatic stress, bipolar, psychotic, eating, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity. The interviews show and teach how to rate psychopathology items, how to score the dimensions, and how to evaluate the severity of the disorder(s). All of the SCIP’s 18 scales have been uploaded into the Epic electronic health record (EHR) system at West Virginia University hospitals. A pilot project for implementing MBC in the treatment of adult psychiatric disorders at the West Virginia University residency program and other programs is underway. If we instruct residents in MBC during their psychiatric training, they will likely practice it for the rest of their clinical careers. Except for a minority of clinicians who are involved in clinical trials and who use rating scales in practice, most practicing clinicians were never trained to use scales. For more information about the MBC curriculum and videotapes, contact Dr. Aboraya at [email protected] or visit www.scip-psychiatry.com.

Today, some of the barriers that impede the implementation of MBC in psychiatric practice have been resolved, but much more work remains. Now is the time to implement MBC and provide an answer to AJ Rush, who asked, “Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice?”24 The 3 main ingredients for MBC implementation—useful measures, integration of EHR, and health information technologies—exist today. We strongly encourage psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health professionals to adopt MBC in their daily practice.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

In an editorial published in Current Psychiatry 10 years ago, I cited a stunning fact based on a readers’ survey: 98% of psychiatrists did not use any of the 4 clinical rating scales that are routinely used in the clinical trials required for FDA approval of medications for psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders.1

As a follow-up, Ahmed Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and I would like to report on the state of measurement-based care (MBC), a term coined by Trivedi in 2006 and defined by Fortney as “the systematic administration of symptom rating scales and use of the results to drive clinical decision making at the level of the individual patient.”2

We will start with the creator of modern rating scales, Father Thomas Verner Moore (1877-1969), who is considered one of the most underrecognized legends in the history of modern psychiatry. Moore was a psychologist and psychiatrist who can lay claim to 3 major achievements in psychiatry: the creation of rating scales in psychiatry, the use of factor analysis to deconstruct psychosis, and the formulation of specific definitions for symptoms and signs of psychopathology. Moore’s 1933 book described the rating scales used in his research.3

Since that time, researchers have continued to invent clinician-rated scales, self-report scales, and other measures in psychiatry. The Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, which was published in 2000 by the American Psychiatric Association Task Force chaired by AJ Rush Jr., includes >240 measures covering adult and child psychiatric disorders.4

Recent research has shown the superiority of MBC compared with usual standard care (USC) in improving patient outcomes.2,5-7 A recent well-designed, blind-rater, randomized trial by Guo et al8 showed that MBC is more effective than USC both in achieving response and remission, and reducing the time to response and remission. Given the evidence of the benefits of MBC in improving patient outcomes, and the plethora of reliable and validated rating scales, an important question arises: Why has MBC not yet been established as the standard of care in psychiatric clinical practice? There are many barriers to implementing MBC,9 including:

- time constraints (most commonly cited reason by psychiatrists)

- mismatch between clinical needs and the content of the measure (ie, rating scales are designed for research and not for clinicians’ use)

- measurements produced by rating scales may not always be clinically relevant

- administering rating scales may interfere with establishing rapport with patients

- some measures, such as standardized diagnostic interviews, can be cumbersome, unwieldy, and complicated

- the lack of formal training for most clinicians (among the top barriers for residents and faculty)

- lack of availability of training manuals and protocols.

Clinician researchers have started to adapt and invent instruments that can be used in clinical settings. For more than 20 years, Mark Zimmerman, MD, has been the principal investigator of the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project, aimed at integrating the assessment methods of researchers into routine clinical practice.10 Zimmerman has developed self-report scales and outcome measures such as the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ), the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS), the Standardized Clinical Outcome Rating for Depression (SCOR-D), the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale (CUXOS), the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ), and the Clinically Useful Patient Satisfaction Scale (CUPSS).11-18

We have been critical of the utility of the existing diagnostic interviews and rating scales. I (AA) developed the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) as a MBC tool that addresses the most common barriers that clinicians face.9,19-23 The SCIP includes 18 clinician-rated scales for the following symptom domains: generalized anxiety, obsessions, compulsions, posttraumatic stress, depression, mania, delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thoughts, aggression, negative symptoms, alcohol use, drug use, attention deficit, hyperactivity, anorexia, binge-eating, and bulimia. The SCIP rating scales meet the criteria for MBC because they are efficient, reliable, and valid. They reflect how clinicians assess psychiatric disorders, and are relevant to decision-making. Both self-report and clinician-rated scales are important MBC tools and complementary to each other. The choice to use self-report scales, clinician-rated scales, or both depends on several factors, including the clinical setting (inpatient or outpatient), psychiatric diagnoses, and patient characteristics. No measure or scale will ever replace a seasoned and experienced clinician who has been evaluating and treating real-world patients for years. Just as thermometers, stethoscopes, and laboratories help other types of physicians to reach accurate diagnoses and provide appropriate management, the use of MBC by psychiatrists will enhance the accuracy of diagnoses and improve the outcomes of care.

Continue to: On a positive note...

On a positive note, I (AA) have completed a MBC curriculum for training psychiatry residents that includes 11 videotaped interviews with actual patients covering the major adult psychiatric disorders: generalized anxiety, panic, depressive, posttraumatic stress, bipolar, psychotic, eating, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity. The interviews show and teach how to rate psychopathology items, how to score the dimensions, and how to evaluate the severity of the disorder(s). All of the SCIP’s 18 scales have been uploaded into the Epic electronic health record (EHR) system at West Virginia University hospitals. A pilot project for implementing MBC in the treatment of adult psychiatric disorders at the West Virginia University residency program and other programs is underway. If we instruct residents in MBC during their psychiatric training, they will likely practice it for the rest of their clinical careers. Except for a minority of clinicians who are involved in clinical trials and who use rating scales in practice, most practicing clinicians were never trained to use scales. For more information about the MBC curriculum and videotapes, contact Dr. Aboraya at [email protected] or visit www.scip-psychiatry.com.

Today, some of the barriers that impede the implementation of MBC in psychiatric practice have been resolved, but much more work remains. Now is the time to implement MBC and provide an answer to AJ Rush, who asked, “Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice?”24 The 3 main ingredients for MBC implementation—useful measures, integration of EHR, and health information technologies—exist today. We strongly encourage psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health professionals to adopt MBC in their daily practice.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Nasrallah HA. Long overdue: measurement-based psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(4):14-16.

2. Fortney JC, Unutzer J, Wrenn G, et al. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;68(2):179-188.

3. Moore TV. The essential psychoses and their fundamental syndromes. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1933.

4. Rush AJ. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

5. Scott K, Lewis CC. Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(1):49-59.

6. Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 2):S61-S71.

7. Harding KJ, Rush AJ, Arbuckle M, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: a policy framework for implementation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1136-1143.

8. Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, et al. Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):1004-1013.

9. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick D, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatry: past, present and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

10. Zimmerman M. A review of 20 years of research on overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(2):71-79.

11. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The reliability and validity of a screening questionnaire for 13 DSM-IV Axis I disorders (the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire) in psychiatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(10):677-683.

12. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: development, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(3):175-189.

13. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, McGlinchey JB, et al. A clinically useful depression outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):131-140.

14. Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, Chelminski I, et al. Standardized clinical outcome rating scale for depression for use in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22(1):36-40.

15. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D, et al. A clinically useful anxiety outcome scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):534-542.

16. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Attiullah N, et al. Depressed patients’ perspectives of 2 measures of outcome: the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) and the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ). Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2011;23(3):208-212.

17. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Attiullah N, et al. The remission from depression questionnaire as an outcome measure in the treatment of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(6):533-538.

18. Zimmerman M, Gazarian D, Multach M, et al. A clinically useful self-report measure of psychiatric patients’ satisfaction with the initial evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2017;252:38-44.

19. Aboraya A. The validity results of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP). Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015;41(Suppl 1):S103-S104.

20. Aboraya A. Instruction manual for the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP). http://innovationscns.com/wp-content/uploads/SCIP_Instruction_Manual.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2019.

21. Aboraya A, El-Missiry A, Barlowe J, et al. The reliability of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional and numeric output. Schizophr Res. 2014;156(2-3):174-183.

22. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Muvvala S, et al. The Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional, and numeric output-conceptual development, design, and description of the SCIP. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(5-6):31-77.

23. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA. Perspectives on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): Use, misuse, drawbacks, and a new alternative for schizophrenia research. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(2):125-131.

24. Rush AJ. Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice? Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):934-936.