User login

Dermatology departments in the United States have been facing challenges in recruiting and retaining dermatologists for academic positions. Accordingly, a survey study reported that academic dermatologists were more likely than those in private practice to state that their institutions were recruiting new associates.1 Several factors could explain this phenomenon. Salary differences between jobs in academic and nonacademic settings may contribute to difficulty in recruiting dermatologists into academia, which is exacerbated by a theoretical shortage of dermatologists, leading to graduates who receive and accept private practice job offers.1,2 Furthermore, a large survey study reported that challenges unique to academic dermatologists include longer patient wait times in addition to responsibilities such as research, hospital consultations, medical writing, and teaching. These patterns raise concerns for the future of teaching institutions because academic dermatologists not only train future physicians but also conduct clinical and basic science research necessary to advance the field and improve patient care.2 Thus, it is important to evaluate the factors that affect career decisions in dermatology and to determine if these factors can be addressed. We hypothesized that student loan burden influences career plans in dermatology and that physicians are not fully educated on loan repayment options. The aims of this preliminary study were to explore the influence of student loan burden on career plans in dermatology and to determine if the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program could potentially encourage more dermatologists to consider academic careers.

Methods

The study aimed to investigate the factors that influence career decisions in dermatology and to assess attitudes toward the PSLF program as an option for student loan repayment. The target population included dermatology residents and attending physicians in the United States. Survey questions were adapted from a previously published study3 and were modified based on feedback from reviewers in the University of California (UC) Irvine department of dermatology. The survey was voluntary and did not collect identifying information. This study was granted exemption from oversight by the UC Irvine institutional review board.

Recruitment materials informed potential participants of the nature of the study and provided a hyperlink to the electronic survey. The UC Irvine department of dermatology emailed US dermatology residency program coordinators, requesting that they forward this study to residents and attending physicians in their programs.

Results

Demographics

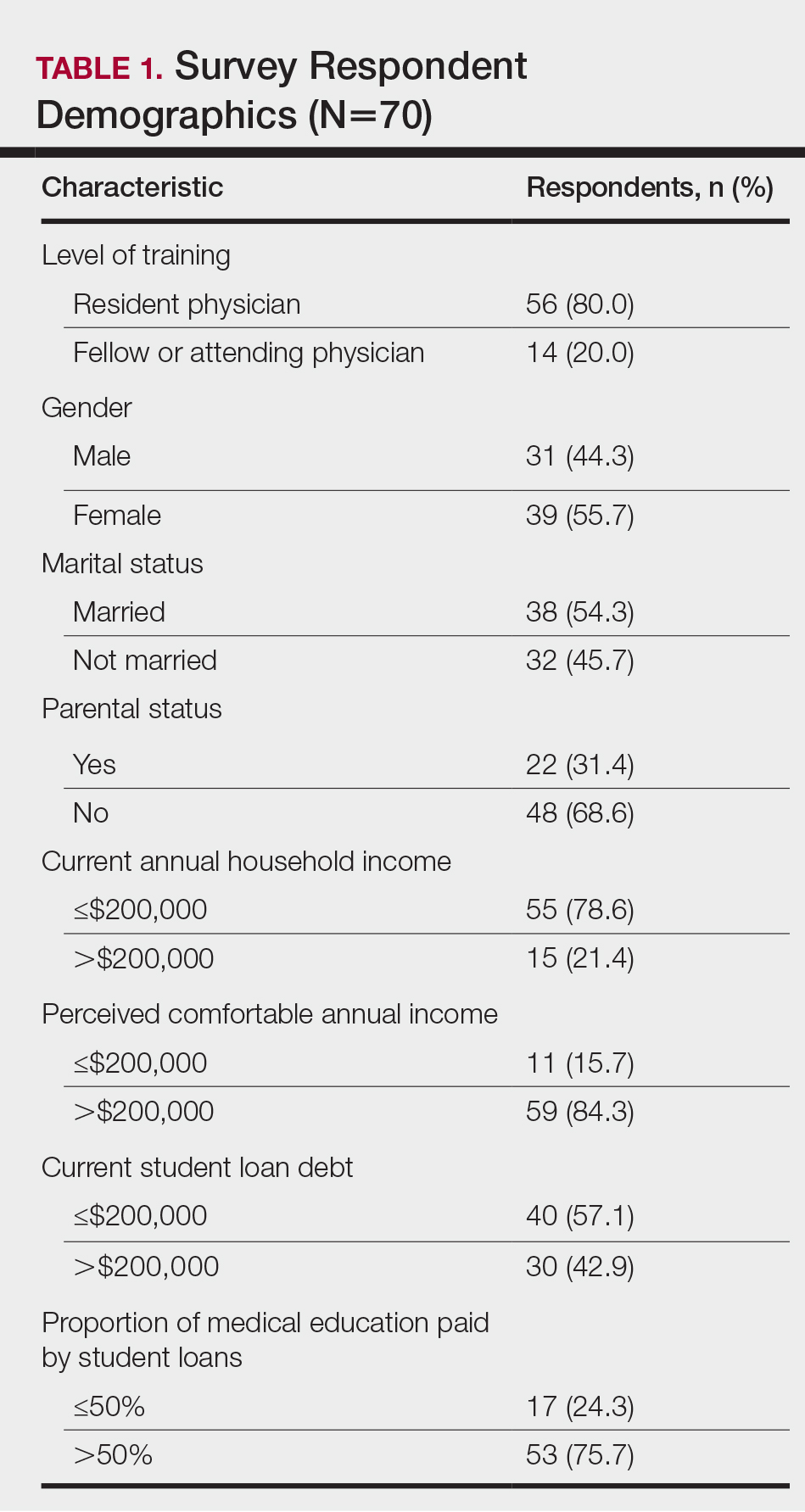

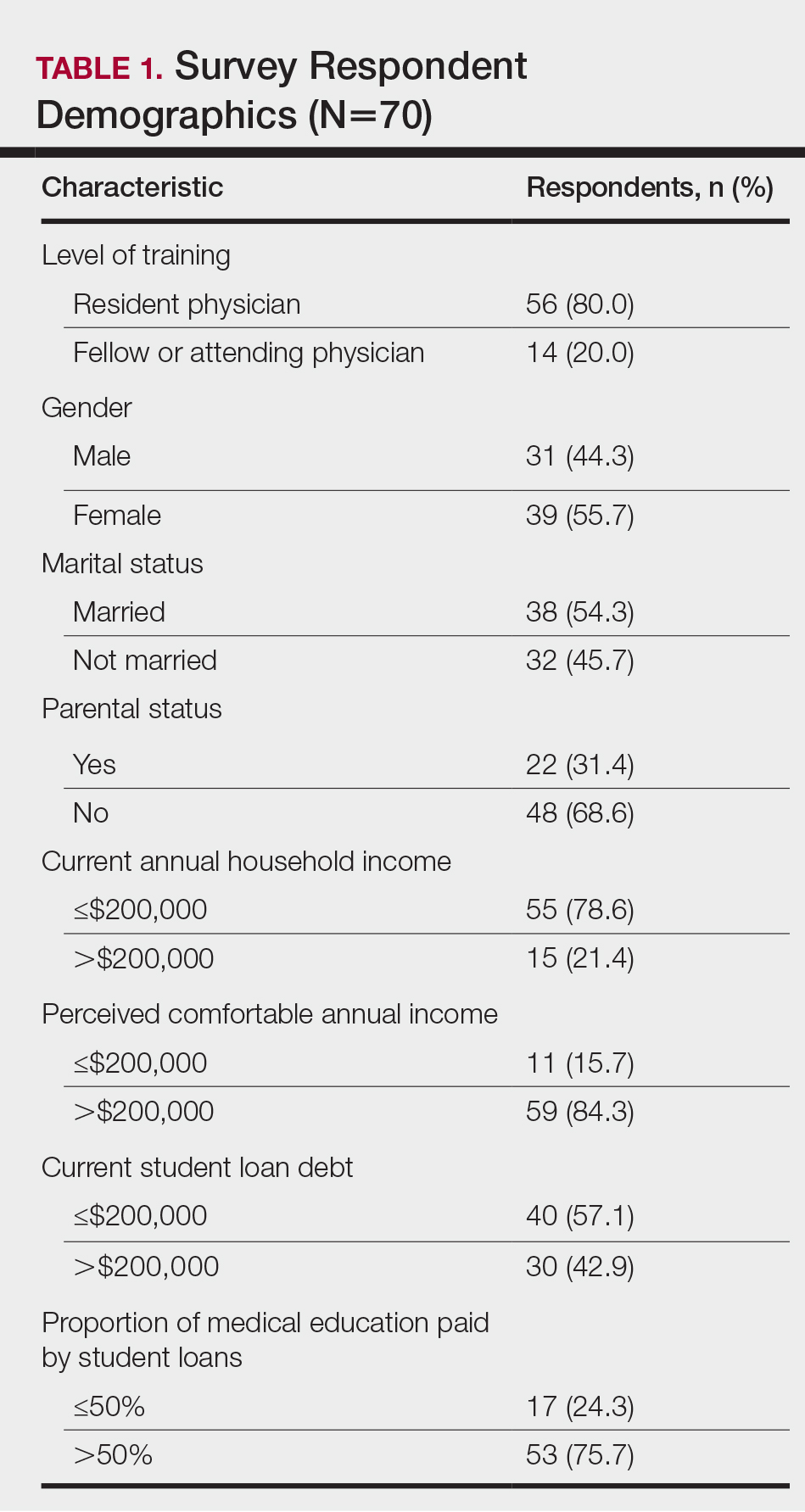

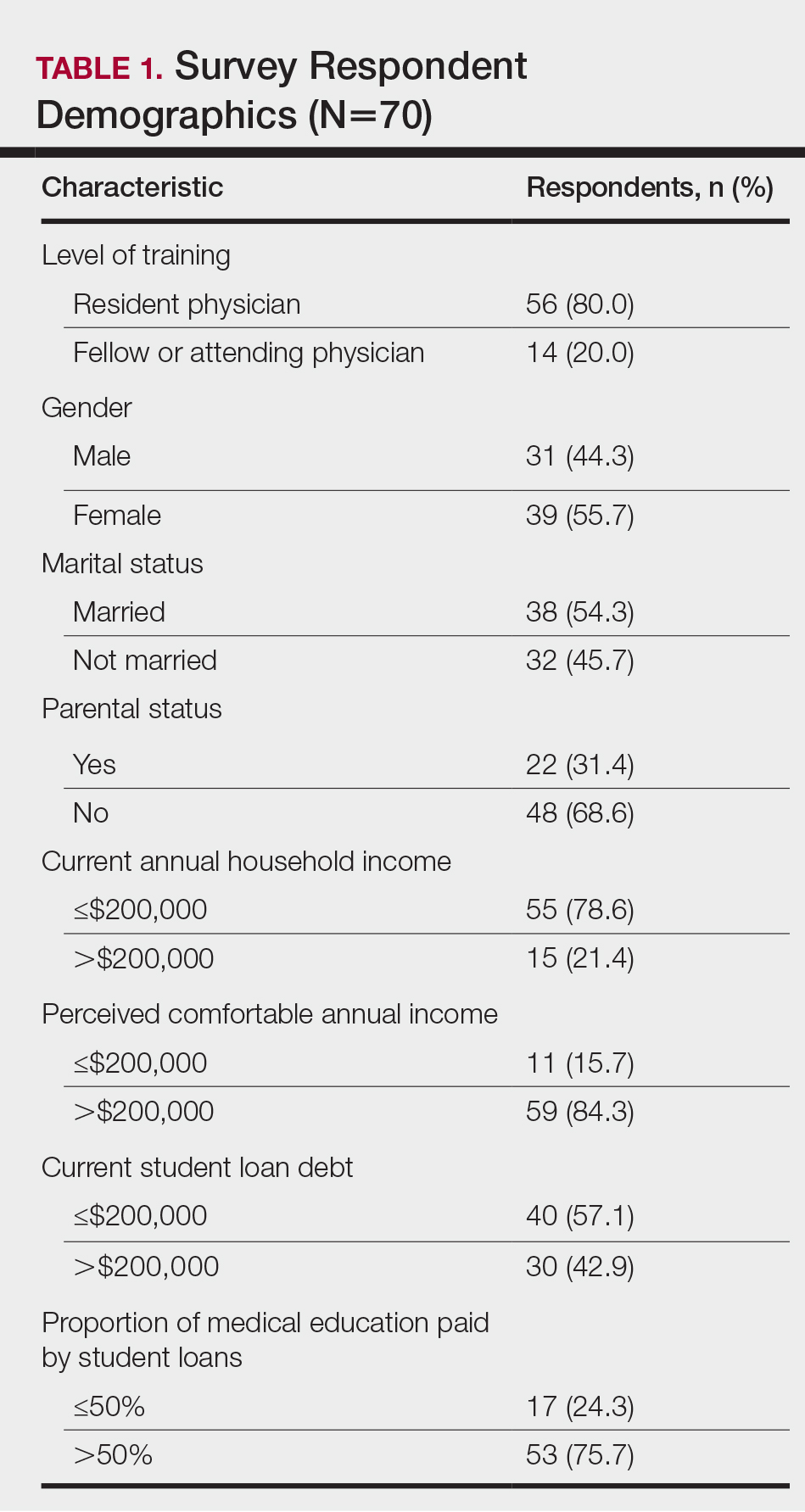

The survey had 70 respondents including residents (56 [80.0%]) and attending physicians (14 [20.0%]). The mean age (SD) of the respondents was 32.4 (6.1) years, with 31 (44.3%) men and 39 (55.7%) women. The majority were married (38 [54.3%]) and did not have children (48 [68.6%]). Most respondents reported an annual household income of $200,000 or less (55 [78.6%]) and perceived a comfortable annual household income as greater than $200,000 (59 [84.3%])(Table 1).

Financing Medical Education

Most respondents currently had $200,000 or less in student loan debt (40 [57.1%]) and financed more than half of their medical education with student loans (53 [75.7%]). A large majority (61 [87.1%]) indicated that some portion of their medical education was funded by student loans.

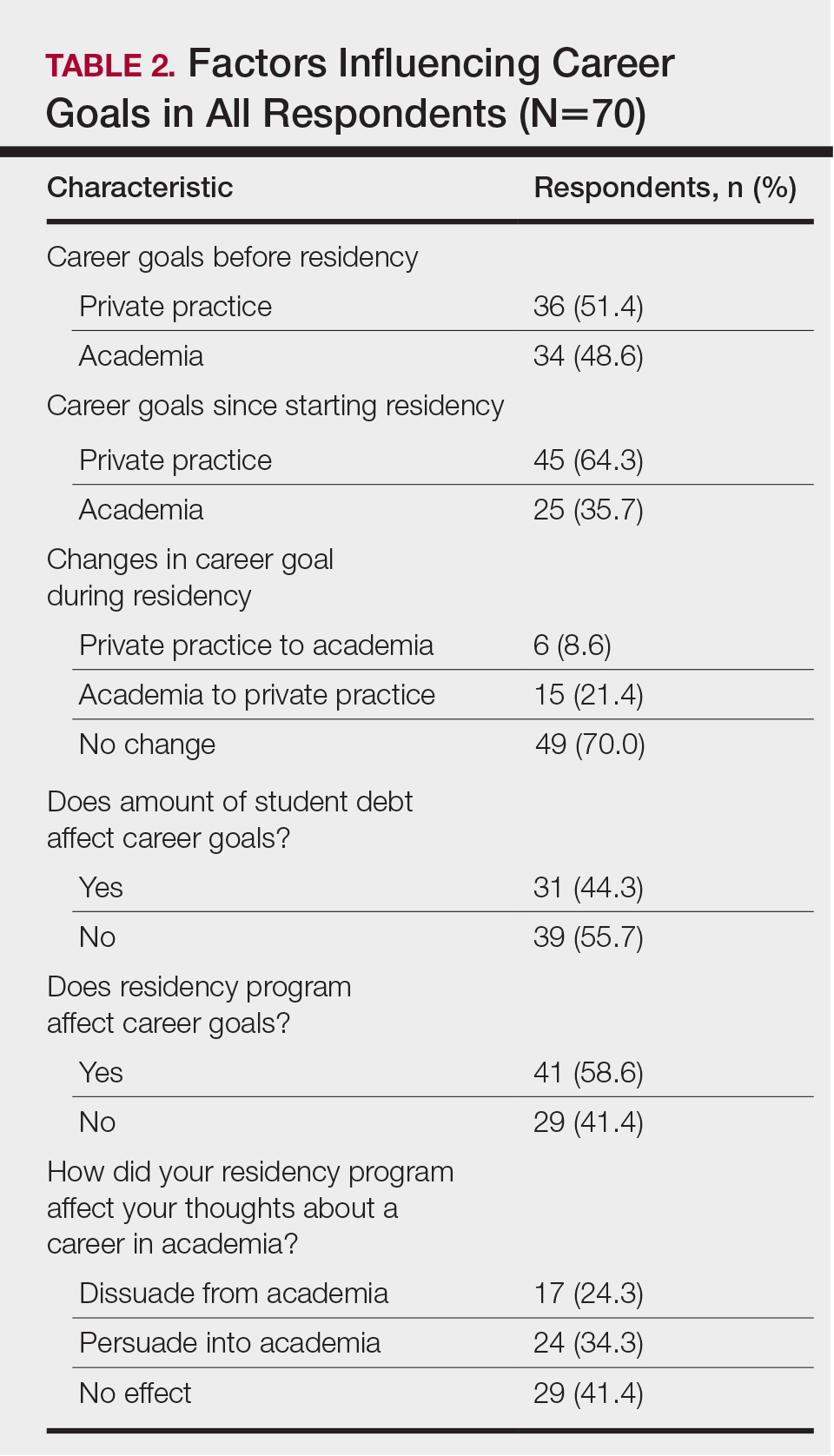

Career Goals in Dermatology and the Influence of Student Loans

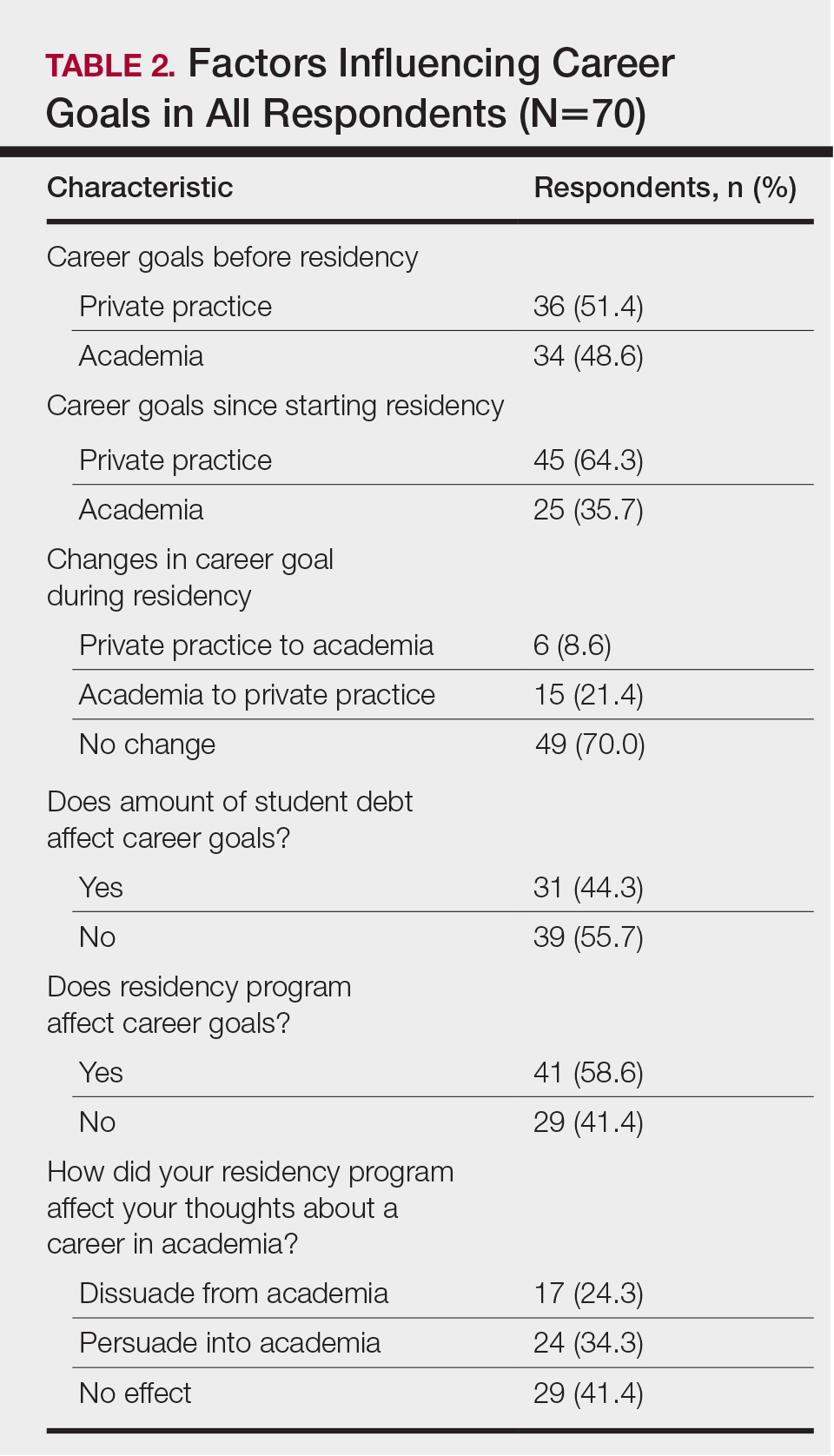

Respondents were asked to specify their career plans before versus after starting dermatology residency training (ie, current career plan). Prior to starting residency, 36 (51.4%) and 34 (48.6%) respondents indicated they were interested in private practice and academia, respectively. After starting residency, the number of respondents interested in private practice increased to 45 (64.3%), and the number of respondents interested in academia decreased to 25 (35.7%). Fifteen (21.4%) respondents changed career trajectories from academia to private practice, 6 (8.6%) changed from private practice to academia, and 49 (70.0%) did not change career goals.

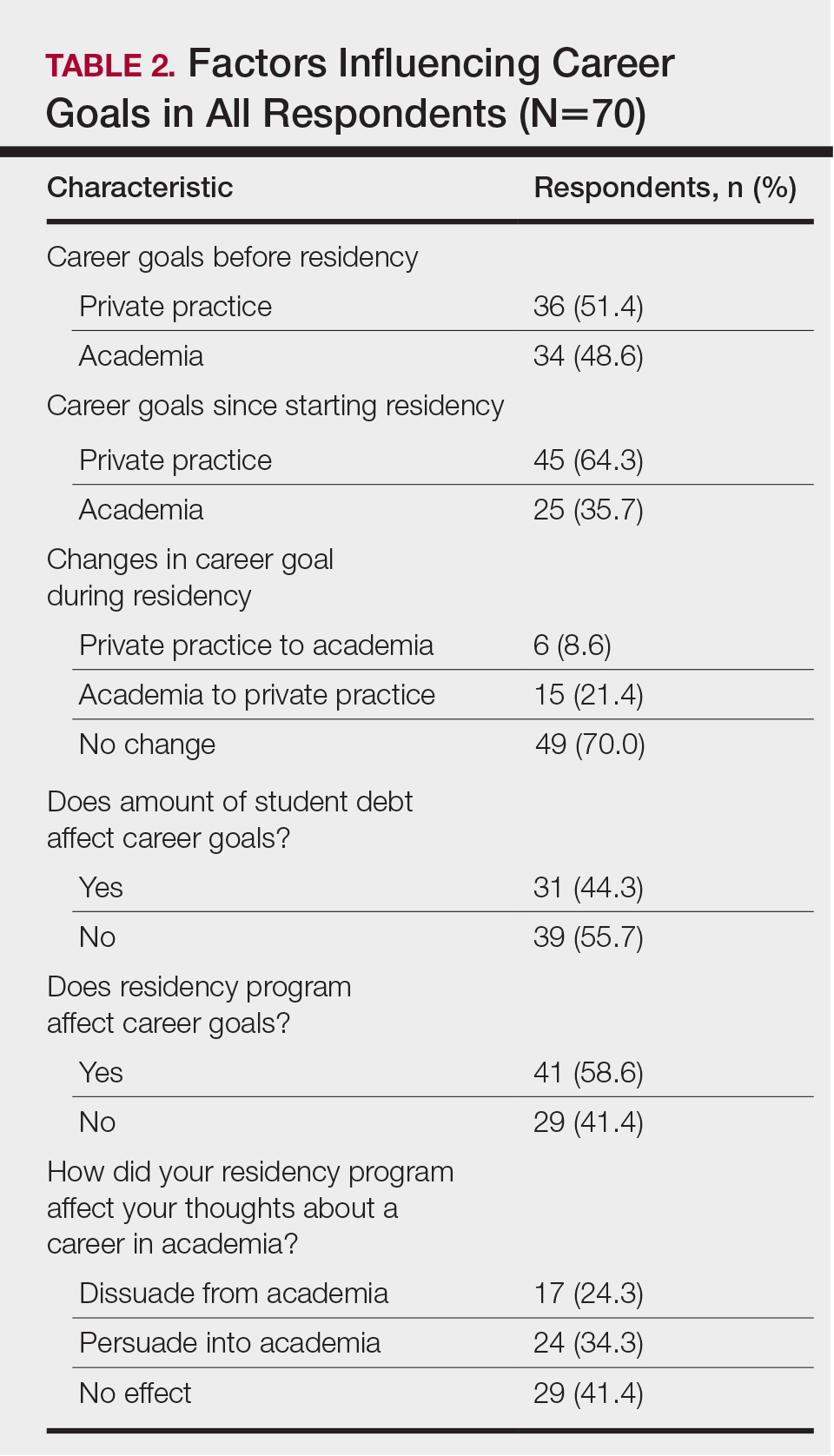

The majority of respondents (39 [55.7%]) indicated that the amount of their student loan debt did not influence their career goals (Table 2); however, those with more than $200,000 in debt were more likely to state that student loans impacted their career goals compared to those with $200,000 or less in debt (70.0% [21/30] vs 25.0% [10/40]; P<.001).

Comparison of Respondents Interested in Careers in Academia vs Private Practice

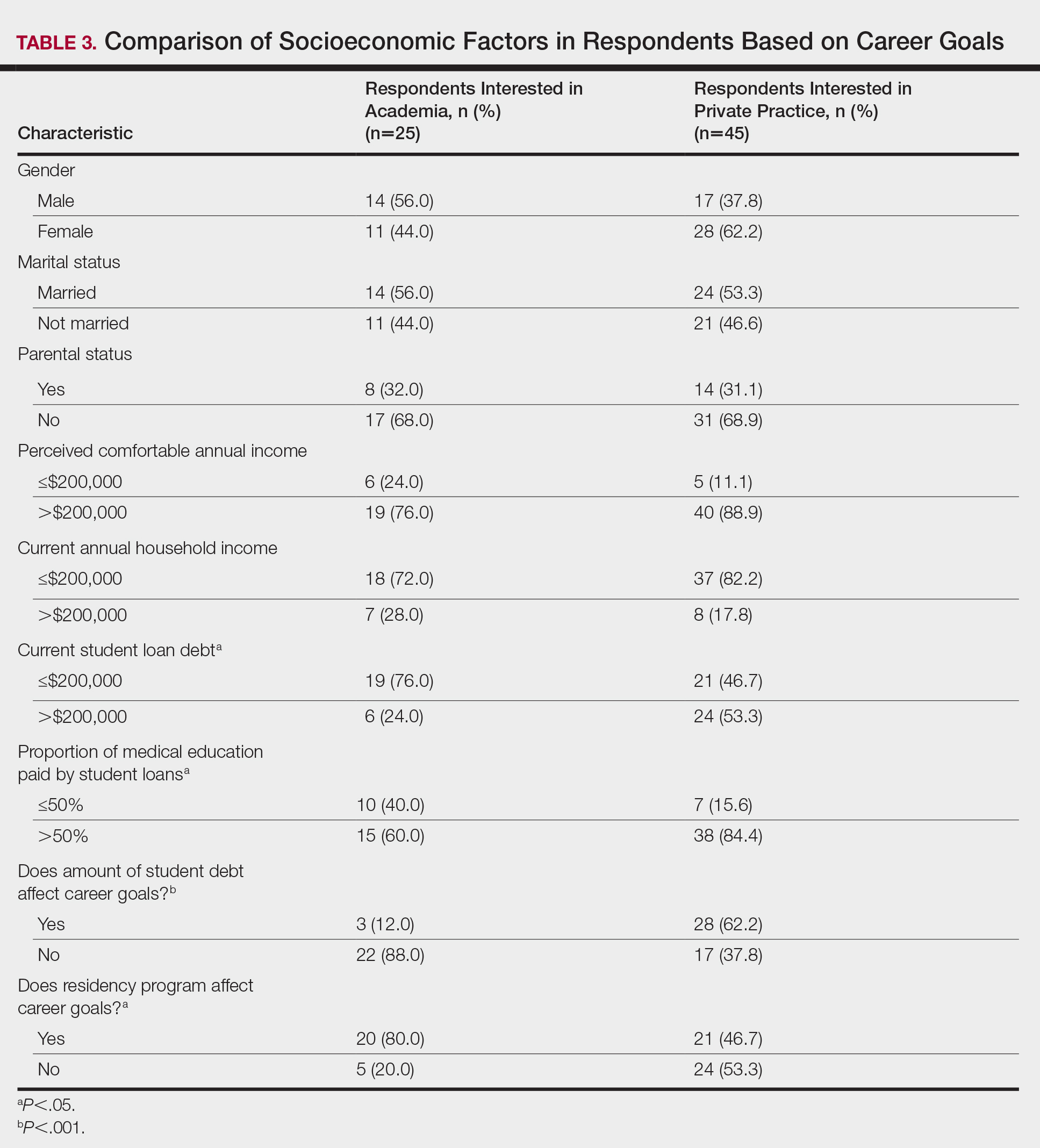

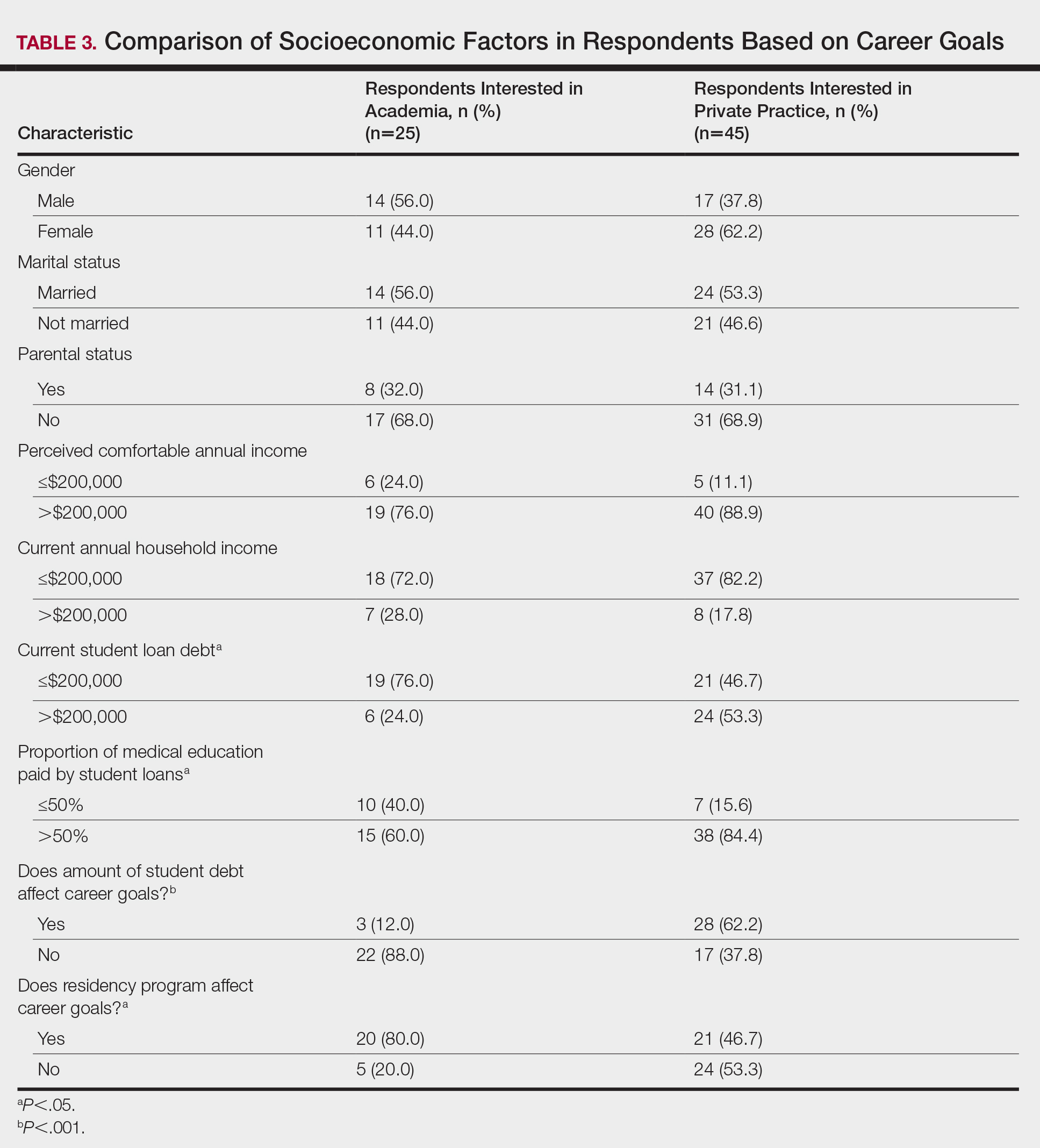

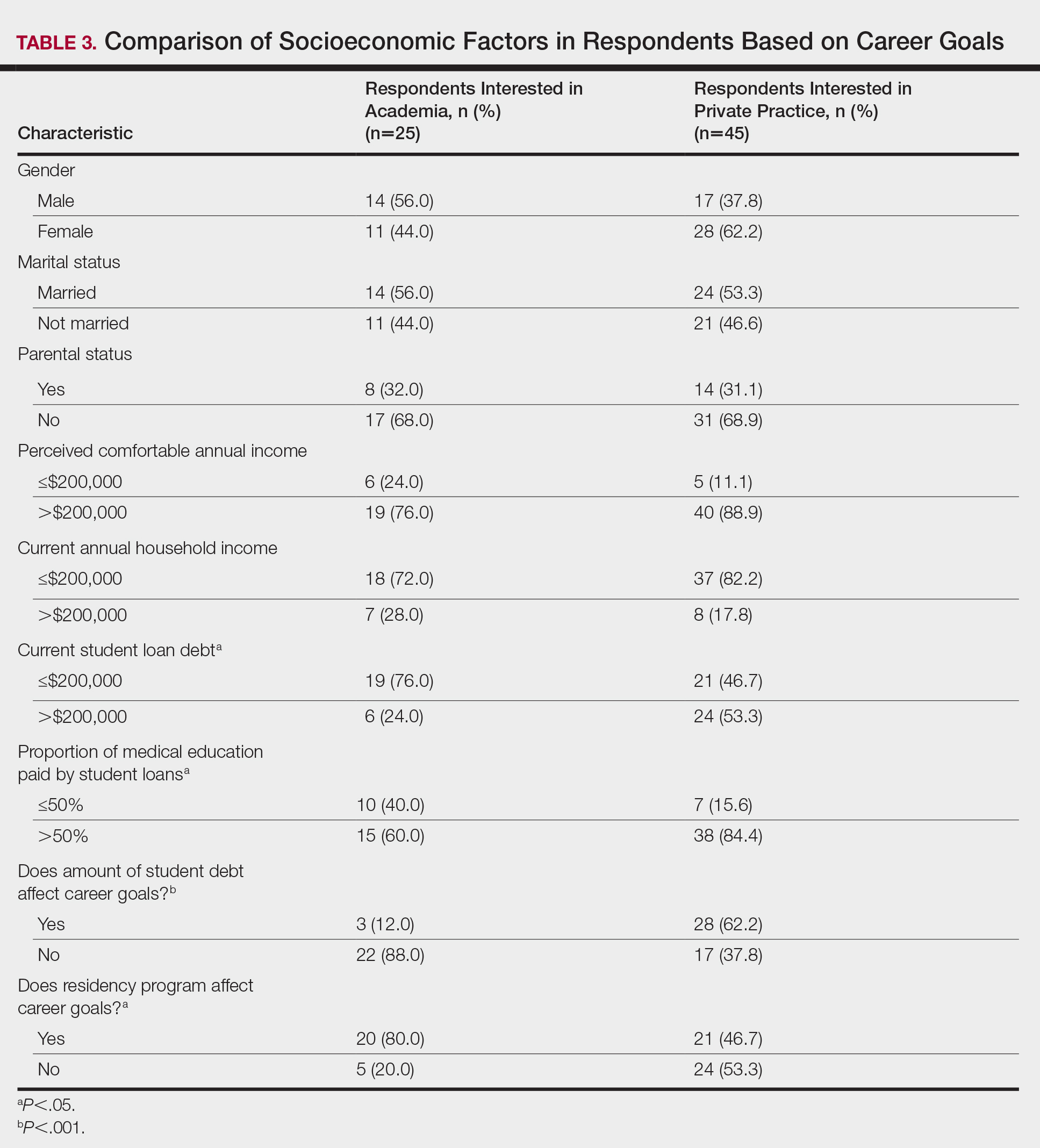

There were differences in financial circumstances between respondents interested in academia versus those interested in private practice. Compared to respondents interested in academia, those interested in private practice were more likely to have more than $200,000 in student loan debt (24 [53.3%] vs 6 [24.0%]; P<.05), have more than half of their education paid with student loans (38 [84.4%] vs 15 [60.0%]; P<.05), and state that student debt affected their career goals (28 [62.2%] vs 3 [12.0%]; P<.001)(Table 3). Demographic characteristics including gender, marital status, parental status, and current annual household income were not associated with a specific career goal.

Subgroup analysis was performed on respondents who were initially interested in academic careers but subsequently decided to pursue private practice (n=15).

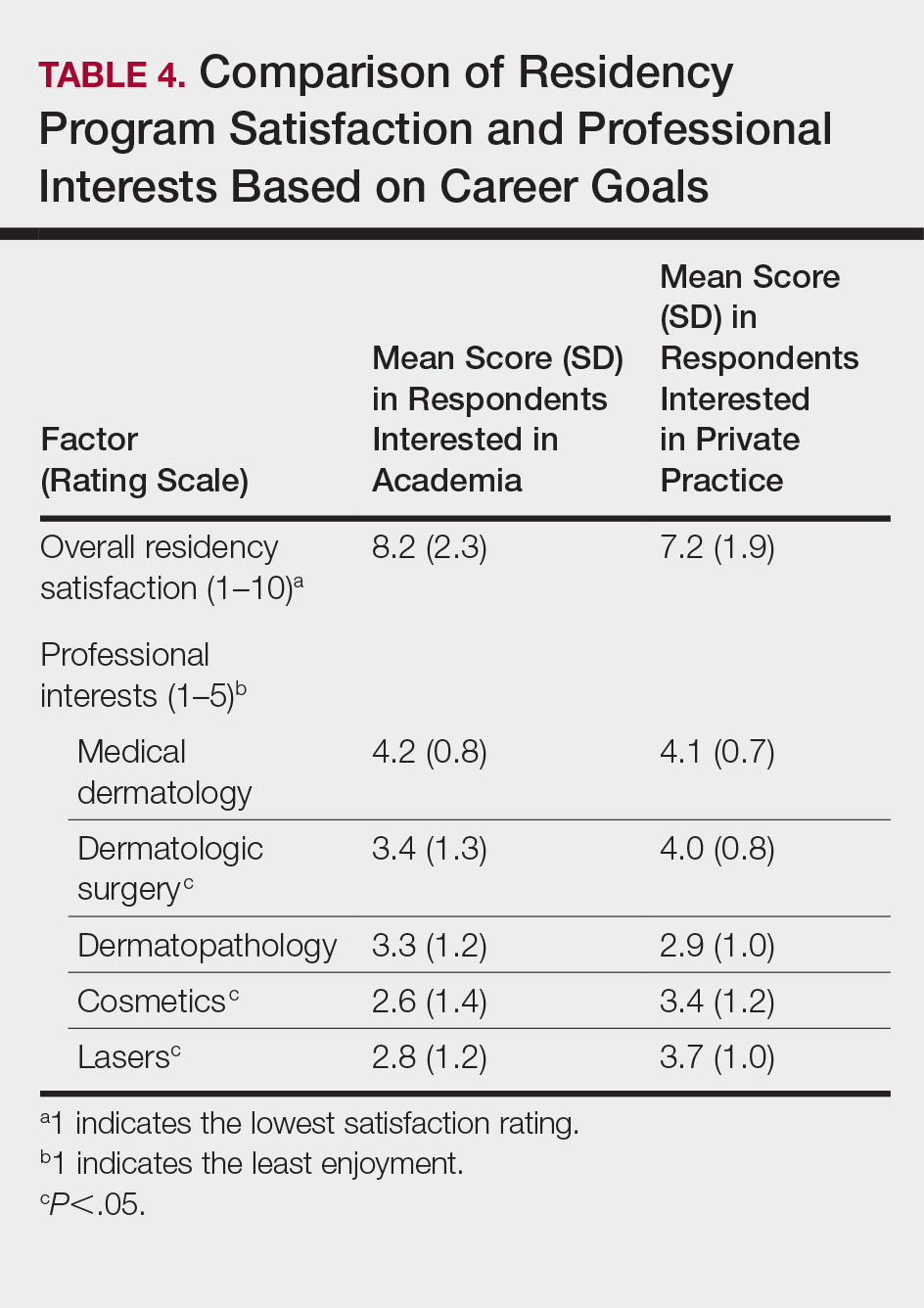

Residency program experience also may influence career trajectory. The majority (n=41 [58.6%]) of respondents indicated that their residency program experience affected their dermatology career goals. Of those, 41.7% and 58.5% stated that their residency program experiences dissuaded and persuaded them into academic positions, respectively. Those interested in academic dermatology were more likely to state that their residency program experience influenced their career goals (80.0% [20/25] vs 46.7% [21/45]; P<.05). Furthermore, those interested in academic positions responded with higher overall residency program satisfaction ratings on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 indicated the lowest satisfaction) than those interested in private practice, but the difference was not significant (mean [SD] score, 8.2 [2.3] vs 7.2 [1.9]; P=.07).

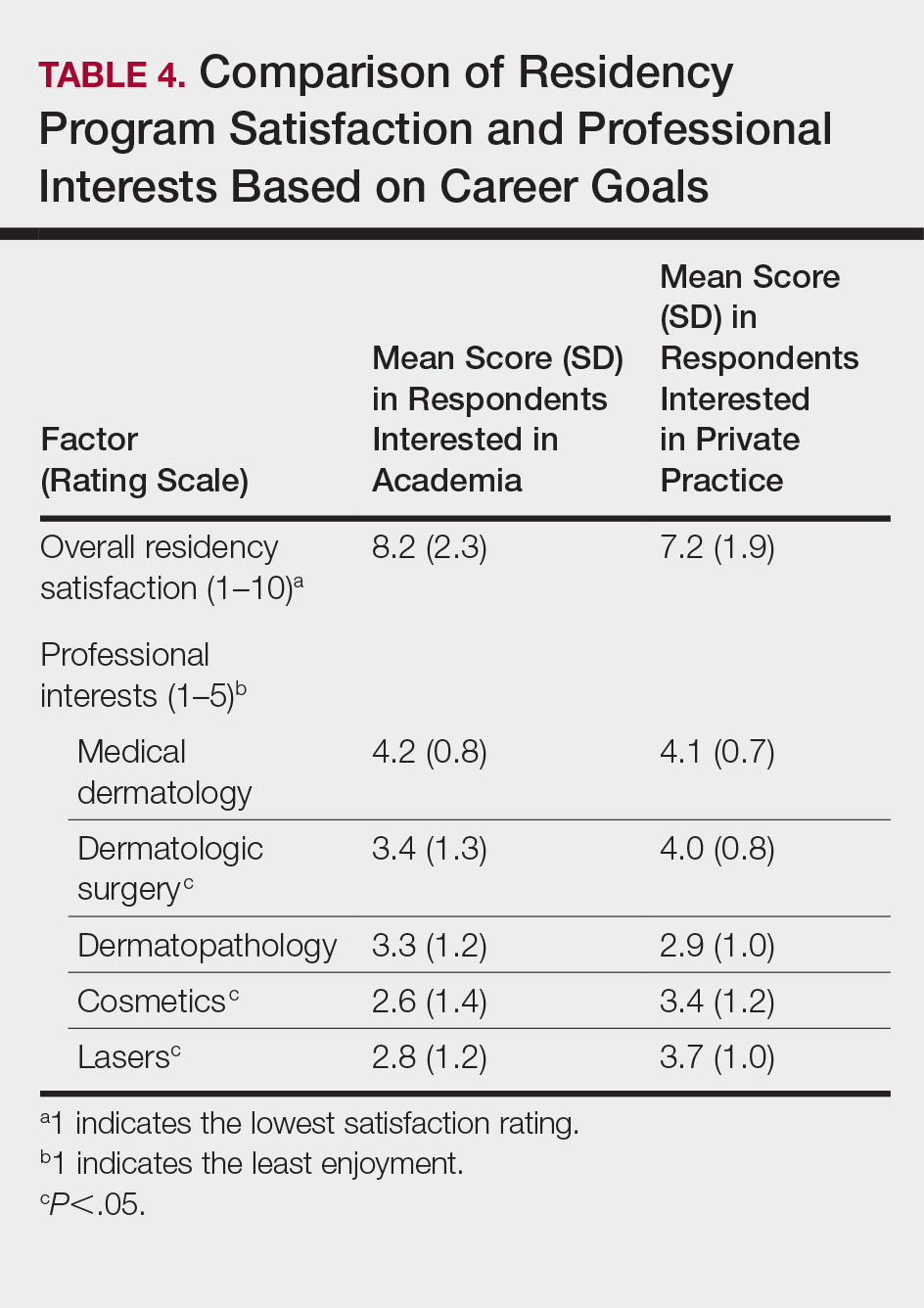

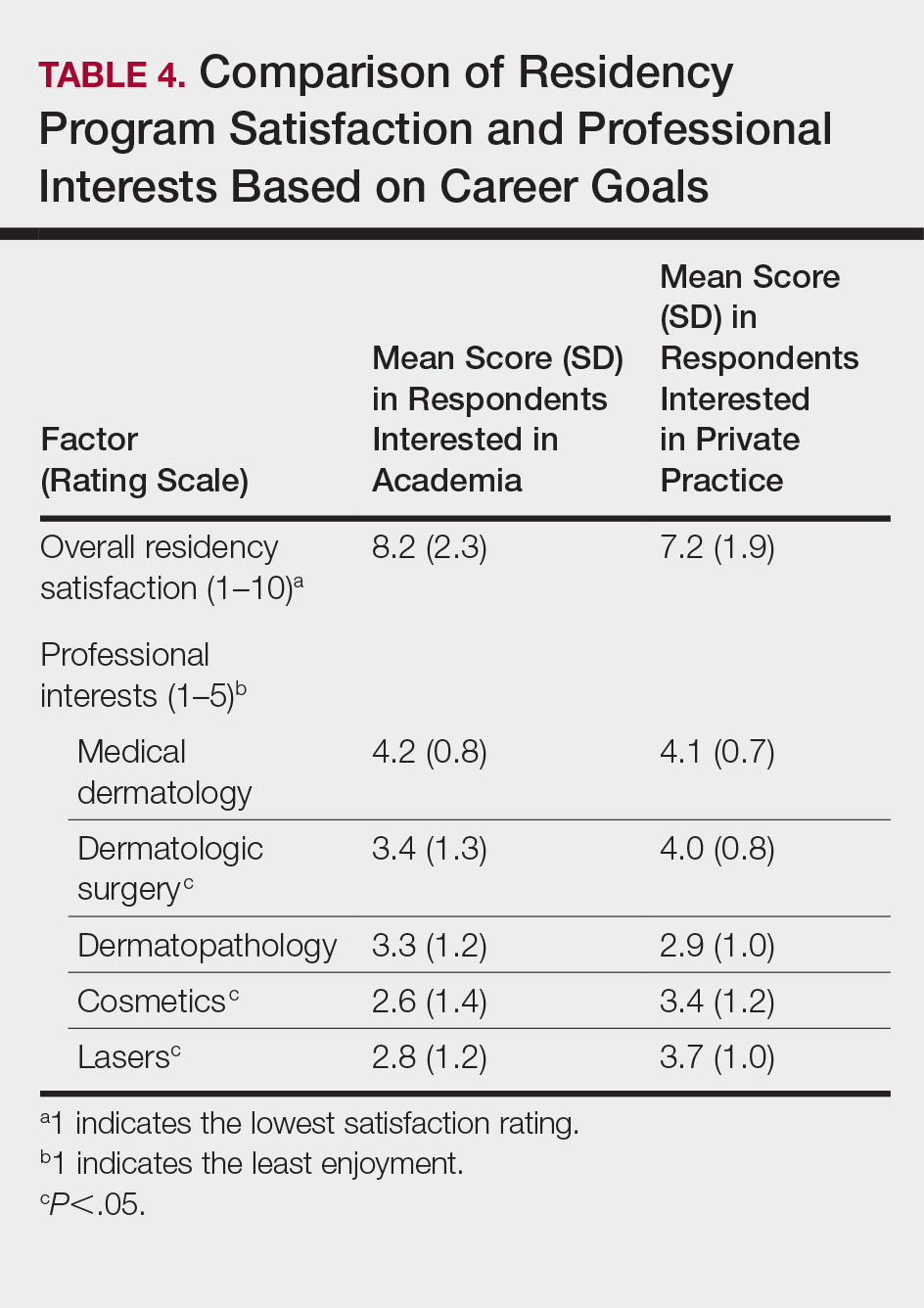

Respondents were asked to rate their interest in the following dermatology-related professional interests on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 indicated the least enjoyment): medical dermatology, dermatologic surgery, dermatopathology, cosmetics, and lasers. Those interested in private practice versus those interested in academic dermatology found more enjoyment in dermatologic surgery (mean [SD] score, 4.0 [0.8] vs 3.4 [1.3]; P<.05), cosmetics (3.4 [1.2] vs 2.6 [1.4]; P<.05), and lasers (3.7 [1.0] vs 2.8 [1.2]; P<.05)(Table 4).

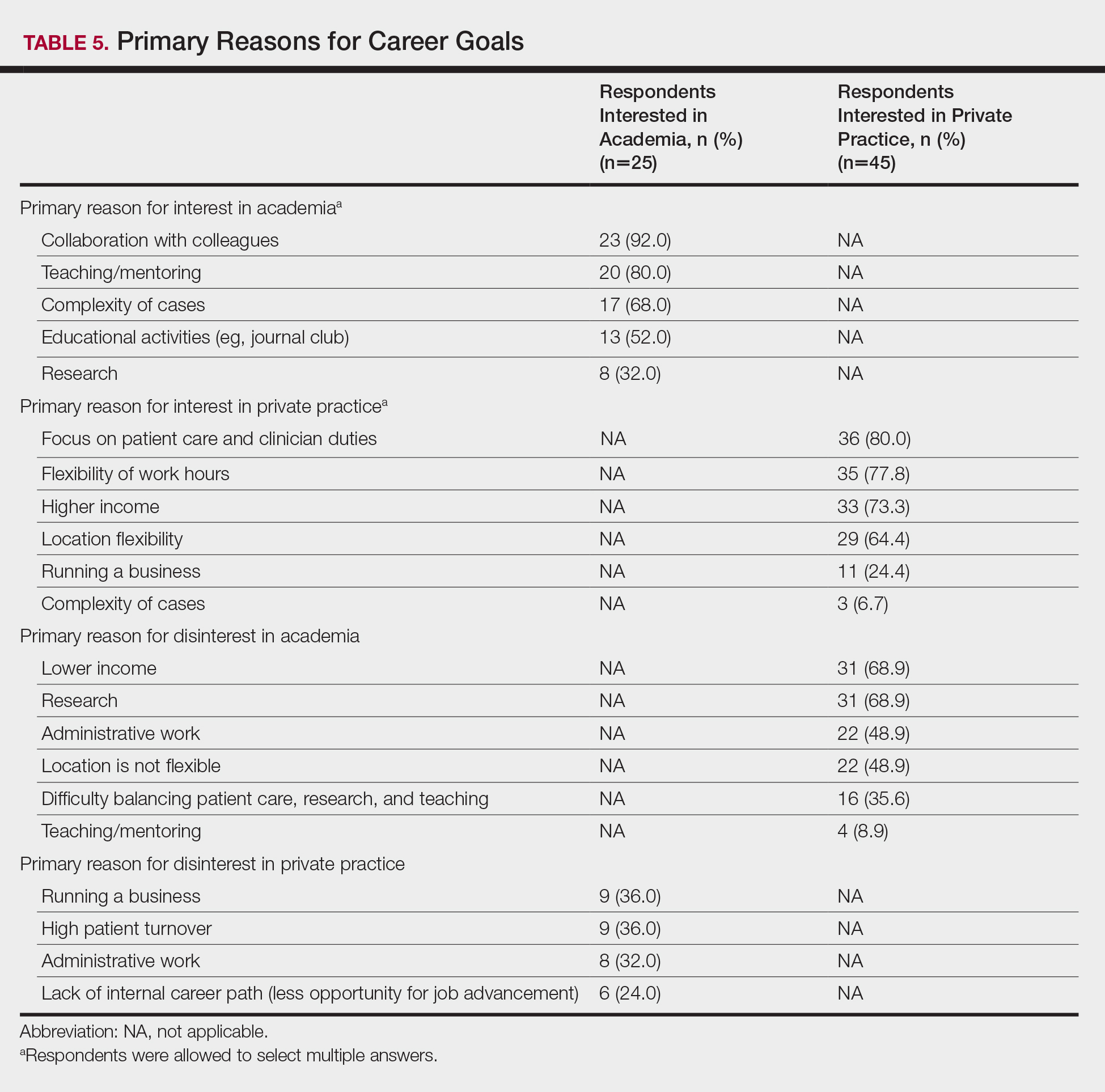

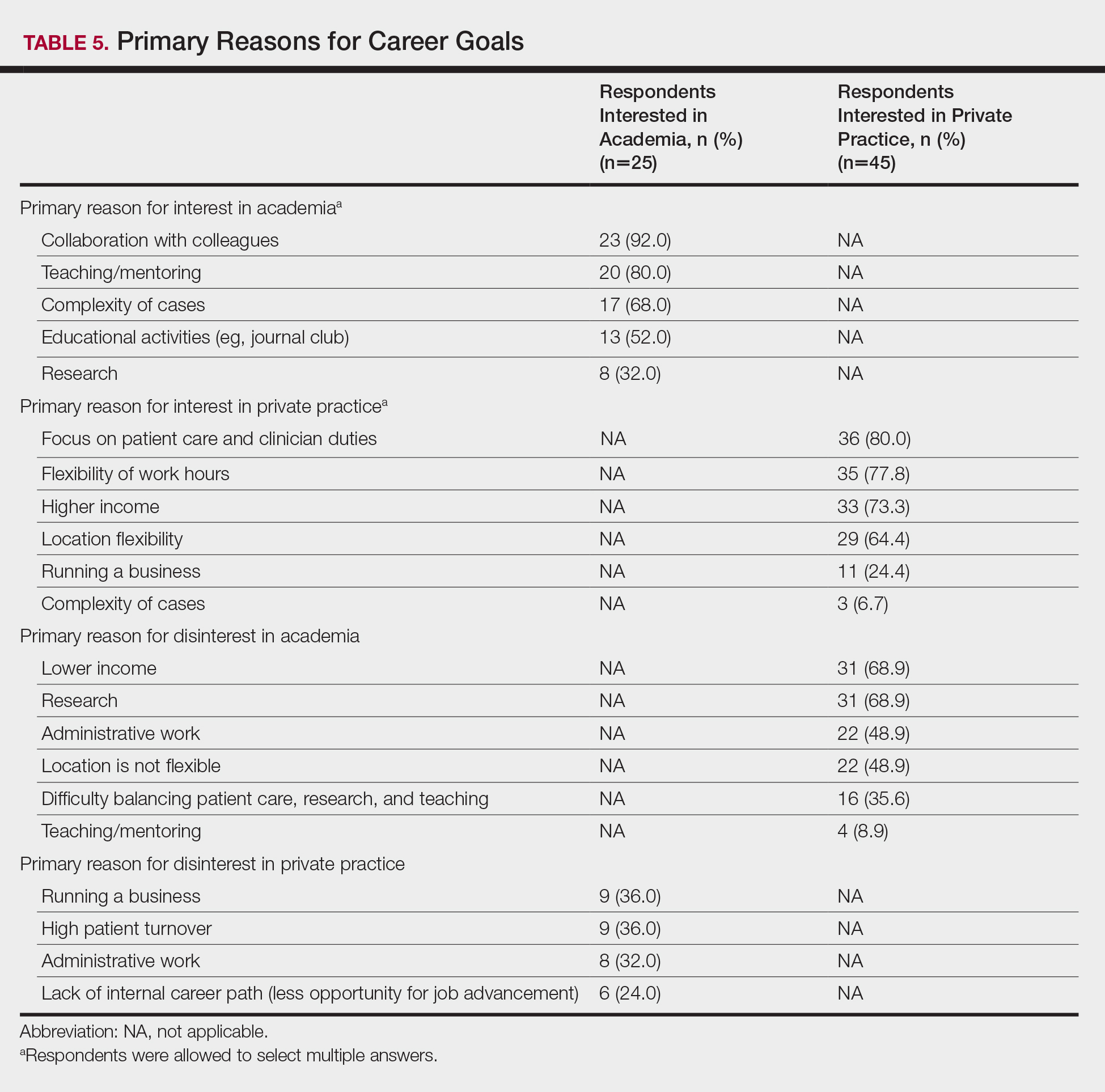

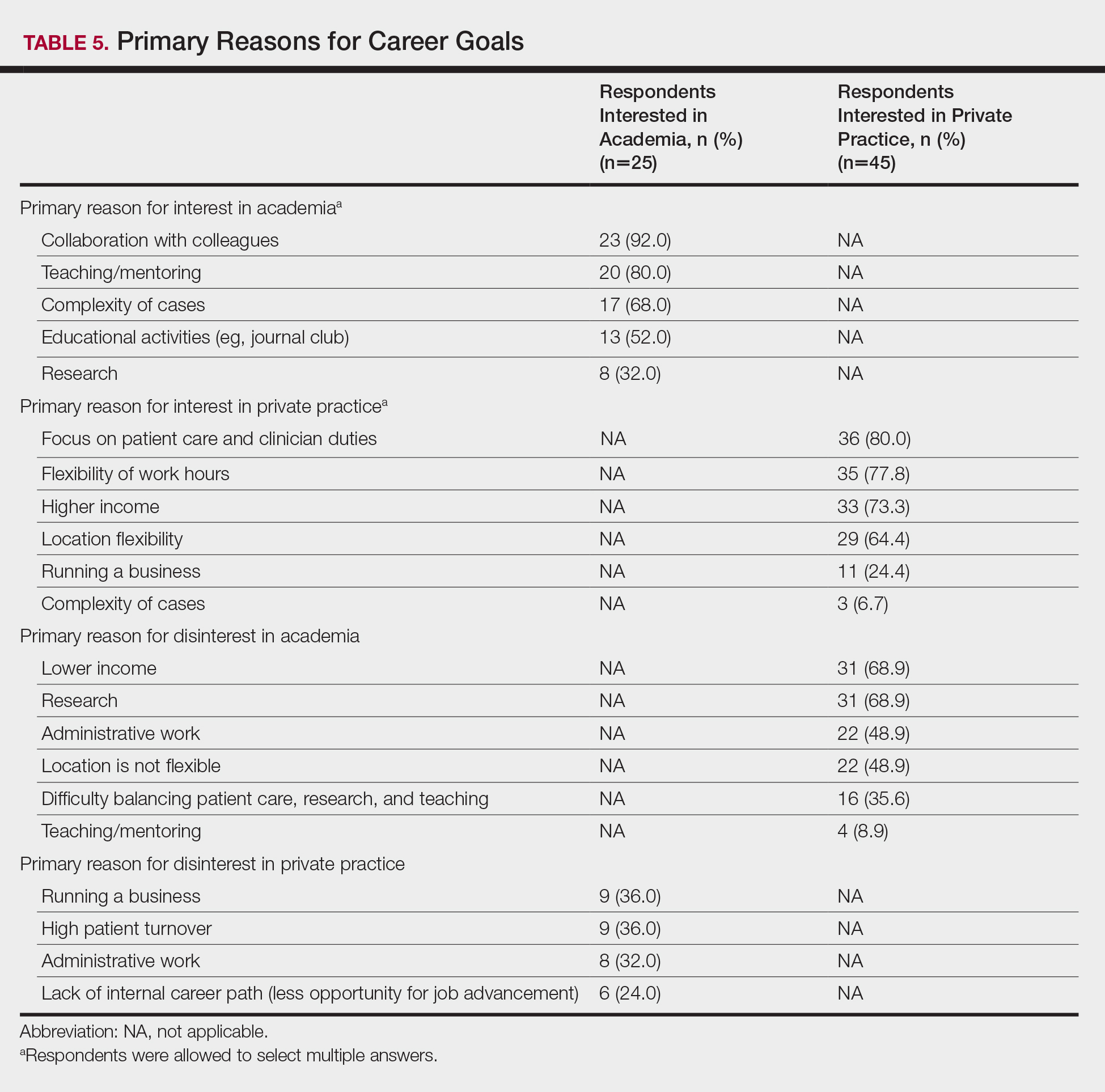

Respondents also were asked to select primary motivating factors for their career goals (ie, academia or private practice) and to indicate reasons for not choosing the alternative. The majority of those pursuing academia were motivated by opportunities to collaborate with colleagues (23 [92.0%]), teach and mentor (20 [80%]), and manage complex cases (17 [68.0%]). Most of the respondents who were pursing private practice were motivated by focus on patient care and clinician duties (36 [80.0%]), flexible work hours (35 [77.8%]), higher income (33 [73.3%]), and location flexibility (29 [64.4%]). Among those interested in academic dermatology, the top factors for disinterest in private practice were running a business (9 [36.0%]) and high patient turnover (9 [36.0%]). Most of those interested in private practice indicated that they were not interested in an academic position because of lower income (31 [68.9%]) and research duties (31 [68.9%])(Table 5).

Awareness of and Attitudes Toward the PSLF Program

The majority of respondents were aware of PSLF (53 [75.7%]); however, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to use PSLF for loan repayment. Respondents were asked how likely they would be to pursue an academic position if given the option to have their student loans forgiven by the PSLF program. Overall, 44.6% (n=25) of respondents indicated that this option would have no effect or would unlikely convince them to pursue an academic position, and 55.4% (n=31) of respondents indicated that they were somewhat likely, likely, or very likely to pursue academia if PSLF was an option. Of those who stated that they would consider enrolling in PSLF, 64.5% (20/31) of individuals were pursuing careers in private practice. Neither current student loan burden nor career goal was associated with likelihood of enrolling in the PSLF.

Comment

In 2015, 76% of medical school graduates in the United States accrued educational debt, with an average of $189,165, a number that has continued to increase over the years.4 In addition to the increasing cost of medical education, higher interest rates on federal student loans contribute to debt burden. Over the last 2 decades, some research has posited that debt may influence medical specialty selection, with most studies focusing on primary care.5-9 However, there is limited information on the effect of student loan debt on career decisions within dermatology.

The results of our study suggest that financial factors including income and amount of educational debt may influence career decisions in dermatology. There is a known income gap between academic and nonacademic settings.

The PSLF can potentially address this issue and be used as a recruiting tool for dermatology positions in academia. Under PSLF, borrowers can have the remainder of their loan balances forgiven after making 120 monthly payments while employed full time by public service employers, including some academic medical institutions. In our study, a large majority of respondents indicated that they are aware of the PSLF, and more than half said they would consider pursuing positions in academia if their loans could be forgiven through the program; however, when asked about plans for loan repayment, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to enroll in PSLF. Thus, despite high interest in PSLF among the survey respondents, few had actual plans to use the service, suggesting that perhaps dermatologists are not provided enough information about PSLF to motivate enrollment. In the same way, almost a quarter of respondents were not familiar with the PSLF as a repayment option, further signifying that distribution of information about financial planning may be inadequate. If student loan burden is a notable factor in career decisions in dermatology, it is important that academic institutions provide sufficient information about repayment to encourage informed decisions. As such, it is possible that educating physicians about options such as PSLF can potentially recruit more dermatologists to academic positions.

Aside from financial reasons, residency program experience and differences in practices in academic and nonacademic settings may impact career trajectories. The majority of respondents stated their residency program experience influenced their career decisions; however, the majority of respondents did not change their minds about career goals since starting residency, suggesting that residency program experience may reinforce but not necessarily alter these choices. Interests in specific focuses within dermatology also may influence career decisions. This study suggests that those pursuing private practice positions are more interested in dermatologic surgery, lasers, and cosmetics.

In this study, we did not find an association between gender and career plans in dermatology. In 2013, more than 60% of dermatology resident physicians were female.12 However, a recent study suggested that women face challenges in academic dermatology, including a downtrend in the number of female investigators with grants from the National Institutes of Health.13

This preliminary study has several limitations. First, the small sample size limited generalizability to all dermatologists. Second, responder bias was possible, as those who have stronger opinions about this topic may have been more inclined to participate in this voluntary survey. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the factors that influence career decisions within dermatology and to determine if there are additional means to increase recruitment into academia.

Conclusion

It is recognized that there are challenges in recruiting dermatologists into academic positions. This study suggests that student loan burden influences career decisions in dermatology. Dermatologists may not be fully educated on options for student loan repayment. With increased awareness, the PSLF can potentially be used as a recruitment tool for positions in academic dermatology.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Resneck JS Jr, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216.

- Lanzon J, Edwards SP, Inglehart MR. Choosing academia versus private practice: factors affecting oral maxillofacial surgery residents’ career choices. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1751-1761.

- AAMC Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2016_Debt_Fact_Card.pdf. Published October 2016. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH. The impact of U.S. medical students’ debt on their choice of primary care careers: an analysis of data from the 2002 medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2005;80:815-819.

- Woodworth PA, Chang FC, Helmer SD. Debt and other influences on career choices among surgical and primary care residents in a community-based hospital system. Am J Surg. 2000;180:570-575; discussion 575-576.

- Phillips RL Jr, Dodoo MS, Petterson S, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? Robert Graham Center website. http://www.graham-center.org/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/monographs-books/Specialty-geography-compressed.pdf. Published March 2, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Rosenthal MP, Marquette PA, Diamond JJ. Trends along the debt-income axis: implications for medical students’ selections of family practice careers. Acad Med. 1996;71:675-677.

- McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, et al. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:416-420.

- Careers in Medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/cim/specialty/exploreoptions/list/us/336836/dermatology.html. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Youngclaus JA, Koehler PA, Kotlikoff LJ, et al. Can medical students afford to choose primary care? an economic analysis of physician education debt repayment. Acad Med. 2013;88:16-25.

- Physician specialty data book 2014. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Physician Specialty Databook 2014.pdf. Published November 2014. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in National Institutes of Health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888.

Dermatology departments in the United States have been facing challenges in recruiting and retaining dermatologists for academic positions. Accordingly, a survey study reported that academic dermatologists were more likely than those in private practice to state that their institutions were recruiting new associates.1 Several factors could explain this phenomenon. Salary differences between jobs in academic and nonacademic settings may contribute to difficulty in recruiting dermatologists into academia, which is exacerbated by a theoretical shortage of dermatologists, leading to graduates who receive and accept private practice job offers.1,2 Furthermore, a large survey study reported that challenges unique to academic dermatologists include longer patient wait times in addition to responsibilities such as research, hospital consultations, medical writing, and teaching. These patterns raise concerns for the future of teaching institutions because academic dermatologists not only train future physicians but also conduct clinical and basic science research necessary to advance the field and improve patient care.2 Thus, it is important to evaluate the factors that affect career decisions in dermatology and to determine if these factors can be addressed. We hypothesized that student loan burden influences career plans in dermatology and that physicians are not fully educated on loan repayment options. The aims of this preliminary study were to explore the influence of student loan burden on career plans in dermatology and to determine if the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program could potentially encourage more dermatologists to consider academic careers.

Methods

The study aimed to investigate the factors that influence career decisions in dermatology and to assess attitudes toward the PSLF program as an option for student loan repayment. The target population included dermatology residents and attending physicians in the United States. Survey questions were adapted from a previously published study3 and were modified based on feedback from reviewers in the University of California (UC) Irvine department of dermatology. The survey was voluntary and did not collect identifying information. This study was granted exemption from oversight by the UC Irvine institutional review board.

Recruitment materials informed potential participants of the nature of the study and provided a hyperlink to the electronic survey. The UC Irvine department of dermatology emailed US dermatology residency program coordinators, requesting that they forward this study to residents and attending physicians in their programs.

Results

Demographics

The survey had 70 respondents including residents (56 [80.0%]) and attending physicians (14 [20.0%]). The mean age (SD) of the respondents was 32.4 (6.1) years, with 31 (44.3%) men and 39 (55.7%) women. The majority were married (38 [54.3%]) and did not have children (48 [68.6%]). Most respondents reported an annual household income of $200,000 or less (55 [78.6%]) and perceived a comfortable annual household income as greater than $200,000 (59 [84.3%])(Table 1).

Financing Medical Education

Most respondents currently had $200,000 or less in student loan debt (40 [57.1%]) and financed more than half of their medical education with student loans (53 [75.7%]). A large majority (61 [87.1%]) indicated that some portion of their medical education was funded by student loans.

Career Goals in Dermatology and the Influence of Student Loans

Respondents were asked to specify their career plans before versus after starting dermatology residency training (ie, current career plan). Prior to starting residency, 36 (51.4%) and 34 (48.6%) respondents indicated they were interested in private practice and academia, respectively. After starting residency, the number of respondents interested in private practice increased to 45 (64.3%), and the number of respondents interested in academia decreased to 25 (35.7%). Fifteen (21.4%) respondents changed career trajectories from academia to private practice, 6 (8.6%) changed from private practice to academia, and 49 (70.0%) did not change career goals.

The majority of respondents (39 [55.7%]) indicated that the amount of their student loan debt did not influence their career goals (Table 2); however, those with more than $200,000 in debt were more likely to state that student loans impacted their career goals compared to those with $200,000 or less in debt (70.0% [21/30] vs 25.0% [10/40]; P<.001).

Comparison of Respondents Interested in Careers in Academia vs Private Practice

There were differences in financial circumstances between respondents interested in academia versus those interested in private practice. Compared to respondents interested in academia, those interested in private practice were more likely to have more than $200,000 in student loan debt (24 [53.3%] vs 6 [24.0%]; P<.05), have more than half of their education paid with student loans (38 [84.4%] vs 15 [60.0%]; P<.05), and state that student debt affected their career goals (28 [62.2%] vs 3 [12.0%]; P<.001)(Table 3). Demographic characteristics including gender, marital status, parental status, and current annual household income were not associated with a specific career goal.

Subgroup analysis was performed on respondents who were initially interested in academic careers but subsequently decided to pursue private practice (n=15).

Residency program experience also may influence career trajectory. The majority (n=41 [58.6%]) of respondents indicated that their residency program experience affected their dermatology career goals. Of those, 41.7% and 58.5% stated that their residency program experiences dissuaded and persuaded them into academic positions, respectively. Those interested in academic dermatology were more likely to state that their residency program experience influenced their career goals (80.0% [20/25] vs 46.7% [21/45]; P<.05). Furthermore, those interested in academic positions responded with higher overall residency program satisfaction ratings on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 indicated the lowest satisfaction) than those interested in private practice, but the difference was not significant (mean [SD] score, 8.2 [2.3] vs 7.2 [1.9]; P=.07).

Respondents were asked to rate their interest in the following dermatology-related professional interests on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 indicated the least enjoyment): medical dermatology, dermatologic surgery, dermatopathology, cosmetics, and lasers. Those interested in private practice versus those interested in academic dermatology found more enjoyment in dermatologic surgery (mean [SD] score, 4.0 [0.8] vs 3.4 [1.3]; P<.05), cosmetics (3.4 [1.2] vs 2.6 [1.4]; P<.05), and lasers (3.7 [1.0] vs 2.8 [1.2]; P<.05)(Table 4).

Respondents also were asked to select primary motivating factors for their career goals (ie, academia or private practice) and to indicate reasons for not choosing the alternative. The majority of those pursuing academia were motivated by opportunities to collaborate with colleagues (23 [92.0%]), teach and mentor (20 [80%]), and manage complex cases (17 [68.0%]). Most of the respondents who were pursing private practice were motivated by focus on patient care and clinician duties (36 [80.0%]), flexible work hours (35 [77.8%]), higher income (33 [73.3%]), and location flexibility (29 [64.4%]). Among those interested in academic dermatology, the top factors for disinterest in private practice were running a business (9 [36.0%]) and high patient turnover (9 [36.0%]). Most of those interested in private practice indicated that they were not interested in an academic position because of lower income (31 [68.9%]) and research duties (31 [68.9%])(Table 5).

Awareness of and Attitudes Toward the PSLF Program

The majority of respondents were aware of PSLF (53 [75.7%]); however, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to use PSLF for loan repayment. Respondents were asked how likely they would be to pursue an academic position if given the option to have their student loans forgiven by the PSLF program. Overall, 44.6% (n=25) of respondents indicated that this option would have no effect or would unlikely convince them to pursue an academic position, and 55.4% (n=31) of respondents indicated that they were somewhat likely, likely, or very likely to pursue academia if PSLF was an option. Of those who stated that they would consider enrolling in PSLF, 64.5% (20/31) of individuals were pursuing careers in private practice. Neither current student loan burden nor career goal was associated with likelihood of enrolling in the PSLF.

Comment

In 2015, 76% of medical school graduates in the United States accrued educational debt, with an average of $189,165, a number that has continued to increase over the years.4 In addition to the increasing cost of medical education, higher interest rates on federal student loans contribute to debt burden. Over the last 2 decades, some research has posited that debt may influence medical specialty selection, with most studies focusing on primary care.5-9 However, there is limited information on the effect of student loan debt on career decisions within dermatology.

The results of our study suggest that financial factors including income and amount of educational debt may influence career decisions in dermatology. There is a known income gap between academic and nonacademic settings.

The PSLF can potentially address this issue and be used as a recruiting tool for dermatology positions in academia. Under PSLF, borrowers can have the remainder of their loan balances forgiven after making 120 monthly payments while employed full time by public service employers, including some academic medical institutions. In our study, a large majority of respondents indicated that they are aware of the PSLF, and more than half said they would consider pursuing positions in academia if their loans could be forgiven through the program; however, when asked about plans for loan repayment, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to enroll in PSLF. Thus, despite high interest in PSLF among the survey respondents, few had actual plans to use the service, suggesting that perhaps dermatologists are not provided enough information about PSLF to motivate enrollment. In the same way, almost a quarter of respondents were not familiar with the PSLF as a repayment option, further signifying that distribution of information about financial planning may be inadequate. If student loan burden is a notable factor in career decisions in dermatology, it is important that academic institutions provide sufficient information about repayment to encourage informed decisions. As such, it is possible that educating physicians about options such as PSLF can potentially recruit more dermatologists to academic positions.

Aside from financial reasons, residency program experience and differences in practices in academic and nonacademic settings may impact career trajectories. The majority of respondents stated their residency program experience influenced their career decisions; however, the majority of respondents did not change their minds about career goals since starting residency, suggesting that residency program experience may reinforce but not necessarily alter these choices. Interests in specific focuses within dermatology also may influence career decisions. This study suggests that those pursuing private practice positions are more interested in dermatologic surgery, lasers, and cosmetics.

In this study, we did not find an association between gender and career plans in dermatology. In 2013, more than 60% of dermatology resident physicians were female.12 However, a recent study suggested that women face challenges in academic dermatology, including a downtrend in the number of female investigators with grants from the National Institutes of Health.13

This preliminary study has several limitations. First, the small sample size limited generalizability to all dermatologists. Second, responder bias was possible, as those who have stronger opinions about this topic may have been more inclined to participate in this voluntary survey. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the factors that influence career decisions within dermatology and to determine if there are additional means to increase recruitment into academia.

Conclusion

It is recognized that there are challenges in recruiting dermatologists into academic positions. This study suggests that student loan burden influences career decisions in dermatology. Dermatologists may not be fully educated on options for student loan repayment. With increased awareness, the PSLF can potentially be used as a recruitment tool for positions in academic dermatology.

Dermatology departments in the United States have been facing challenges in recruiting and retaining dermatologists for academic positions. Accordingly, a survey study reported that academic dermatologists were more likely than those in private practice to state that their institutions were recruiting new associates.1 Several factors could explain this phenomenon. Salary differences between jobs in academic and nonacademic settings may contribute to difficulty in recruiting dermatologists into academia, which is exacerbated by a theoretical shortage of dermatologists, leading to graduates who receive and accept private practice job offers.1,2 Furthermore, a large survey study reported that challenges unique to academic dermatologists include longer patient wait times in addition to responsibilities such as research, hospital consultations, medical writing, and teaching. These patterns raise concerns for the future of teaching institutions because academic dermatologists not only train future physicians but also conduct clinical and basic science research necessary to advance the field and improve patient care.2 Thus, it is important to evaluate the factors that affect career decisions in dermatology and to determine if these factors can be addressed. We hypothesized that student loan burden influences career plans in dermatology and that physicians are not fully educated on loan repayment options. The aims of this preliminary study were to explore the influence of student loan burden on career plans in dermatology and to determine if the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program could potentially encourage more dermatologists to consider academic careers.

Methods

The study aimed to investigate the factors that influence career decisions in dermatology and to assess attitudes toward the PSLF program as an option for student loan repayment. The target population included dermatology residents and attending physicians in the United States. Survey questions were adapted from a previously published study3 and were modified based on feedback from reviewers in the University of California (UC) Irvine department of dermatology. The survey was voluntary and did not collect identifying information. This study was granted exemption from oversight by the UC Irvine institutional review board.

Recruitment materials informed potential participants of the nature of the study and provided a hyperlink to the electronic survey. The UC Irvine department of dermatology emailed US dermatology residency program coordinators, requesting that they forward this study to residents and attending physicians in their programs.

Results

Demographics

The survey had 70 respondents including residents (56 [80.0%]) and attending physicians (14 [20.0%]). The mean age (SD) of the respondents was 32.4 (6.1) years, with 31 (44.3%) men and 39 (55.7%) women. The majority were married (38 [54.3%]) and did not have children (48 [68.6%]). Most respondents reported an annual household income of $200,000 or less (55 [78.6%]) and perceived a comfortable annual household income as greater than $200,000 (59 [84.3%])(Table 1).

Financing Medical Education

Most respondents currently had $200,000 or less in student loan debt (40 [57.1%]) and financed more than half of their medical education with student loans (53 [75.7%]). A large majority (61 [87.1%]) indicated that some portion of their medical education was funded by student loans.

Career Goals in Dermatology and the Influence of Student Loans

Respondents were asked to specify their career plans before versus after starting dermatology residency training (ie, current career plan). Prior to starting residency, 36 (51.4%) and 34 (48.6%) respondents indicated they were interested in private practice and academia, respectively. After starting residency, the number of respondents interested in private practice increased to 45 (64.3%), and the number of respondents interested in academia decreased to 25 (35.7%). Fifteen (21.4%) respondents changed career trajectories from academia to private practice, 6 (8.6%) changed from private practice to academia, and 49 (70.0%) did not change career goals.

The majority of respondents (39 [55.7%]) indicated that the amount of their student loan debt did not influence their career goals (Table 2); however, those with more than $200,000 in debt were more likely to state that student loans impacted their career goals compared to those with $200,000 or less in debt (70.0% [21/30] vs 25.0% [10/40]; P<.001).

Comparison of Respondents Interested in Careers in Academia vs Private Practice

There were differences in financial circumstances between respondents interested in academia versus those interested in private practice. Compared to respondents interested in academia, those interested in private practice were more likely to have more than $200,000 in student loan debt (24 [53.3%] vs 6 [24.0%]; P<.05), have more than half of their education paid with student loans (38 [84.4%] vs 15 [60.0%]; P<.05), and state that student debt affected their career goals (28 [62.2%] vs 3 [12.0%]; P<.001)(Table 3). Demographic characteristics including gender, marital status, parental status, and current annual household income were not associated with a specific career goal.

Subgroup analysis was performed on respondents who were initially interested in academic careers but subsequently decided to pursue private practice (n=15).

Residency program experience also may influence career trajectory. The majority (n=41 [58.6%]) of respondents indicated that their residency program experience affected their dermatology career goals. Of those, 41.7% and 58.5% stated that their residency program experiences dissuaded and persuaded them into academic positions, respectively. Those interested in academic dermatology were more likely to state that their residency program experience influenced their career goals (80.0% [20/25] vs 46.7% [21/45]; P<.05). Furthermore, those interested in academic positions responded with higher overall residency program satisfaction ratings on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 indicated the lowest satisfaction) than those interested in private practice, but the difference was not significant (mean [SD] score, 8.2 [2.3] vs 7.2 [1.9]; P=.07).

Respondents were asked to rate their interest in the following dermatology-related professional interests on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 indicated the least enjoyment): medical dermatology, dermatologic surgery, dermatopathology, cosmetics, and lasers. Those interested in private practice versus those interested in academic dermatology found more enjoyment in dermatologic surgery (mean [SD] score, 4.0 [0.8] vs 3.4 [1.3]; P<.05), cosmetics (3.4 [1.2] vs 2.6 [1.4]; P<.05), and lasers (3.7 [1.0] vs 2.8 [1.2]; P<.05)(Table 4).

Respondents also were asked to select primary motivating factors for their career goals (ie, academia or private practice) and to indicate reasons for not choosing the alternative. The majority of those pursuing academia were motivated by opportunities to collaborate with colleagues (23 [92.0%]), teach and mentor (20 [80%]), and manage complex cases (17 [68.0%]). Most of the respondents who were pursing private practice were motivated by focus on patient care and clinician duties (36 [80.0%]), flexible work hours (35 [77.8%]), higher income (33 [73.3%]), and location flexibility (29 [64.4%]). Among those interested in academic dermatology, the top factors for disinterest in private practice were running a business (9 [36.0%]) and high patient turnover (9 [36.0%]). Most of those interested in private practice indicated that they were not interested in an academic position because of lower income (31 [68.9%]) and research duties (31 [68.9%])(Table 5).

Awareness of and Attitudes Toward the PSLF Program

The majority of respondents were aware of PSLF (53 [75.7%]); however, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to use PSLF for loan repayment. Respondents were asked how likely they would be to pursue an academic position if given the option to have their student loans forgiven by the PSLF program. Overall, 44.6% (n=25) of respondents indicated that this option would have no effect or would unlikely convince them to pursue an academic position, and 55.4% (n=31) of respondents indicated that they were somewhat likely, likely, or very likely to pursue academia if PSLF was an option. Of those who stated that they would consider enrolling in PSLF, 64.5% (20/31) of individuals were pursuing careers in private practice. Neither current student loan burden nor career goal was associated with likelihood of enrolling in the PSLF.

Comment

In 2015, 76% of medical school graduates in the United States accrued educational debt, with an average of $189,165, a number that has continued to increase over the years.4 In addition to the increasing cost of medical education, higher interest rates on federal student loans contribute to debt burden. Over the last 2 decades, some research has posited that debt may influence medical specialty selection, with most studies focusing on primary care.5-9 However, there is limited information on the effect of student loan debt on career decisions within dermatology.

The results of our study suggest that financial factors including income and amount of educational debt may influence career decisions in dermatology. There is a known income gap between academic and nonacademic settings.

The PSLF can potentially address this issue and be used as a recruiting tool for dermatology positions in academia. Under PSLF, borrowers can have the remainder of their loan balances forgiven after making 120 monthly payments while employed full time by public service employers, including some academic medical institutions. In our study, a large majority of respondents indicated that they are aware of the PSLF, and more than half said they would consider pursuing positions in academia if their loans could be forgiven through the program; however, when asked about plans for loan repayment, only 1 respondent endorsed current plans to enroll in PSLF. Thus, despite high interest in PSLF among the survey respondents, few had actual plans to use the service, suggesting that perhaps dermatologists are not provided enough information about PSLF to motivate enrollment. In the same way, almost a quarter of respondents were not familiar with the PSLF as a repayment option, further signifying that distribution of information about financial planning may be inadequate. If student loan burden is a notable factor in career decisions in dermatology, it is important that academic institutions provide sufficient information about repayment to encourage informed decisions. As such, it is possible that educating physicians about options such as PSLF can potentially recruit more dermatologists to academic positions.

Aside from financial reasons, residency program experience and differences in practices in academic and nonacademic settings may impact career trajectories. The majority of respondents stated their residency program experience influenced their career decisions; however, the majority of respondents did not change their minds about career goals since starting residency, suggesting that residency program experience may reinforce but not necessarily alter these choices. Interests in specific focuses within dermatology also may influence career decisions. This study suggests that those pursuing private practice positions are more interested in dermatologic surgery, lasers, and cosmetics.

In this study, we did not find an association between gender and career plans in dermatology. In 2013, more than 60% of dermatology resident physicians were female.12 However, a recent study suggested that women face challenges in academic dermatology, including a downtrend in the number of female investigators with grants from the National Institutes of Health.13

This preliminary study has several limitations. First, the small sample size limited generalizability to all dermatologists. Second, responder bias was possible, as those who have stronger opinions about this topic may have been more inclined to participate in this voluntary survey. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the factors that influence career decisions within dermatology and to determine if there are additional means to increase recruitment into academia.

Conclusion

It is recognized that there are challenges in recruiting dermatologists into academic positions. This study suggests that student loan burden influences career decisions in dermatology. Dermatologists may not be fully educated on options for student loan repayment. With increased awareness, the PSLF can potentially be used as a recruitment tool for positions in academic dermatology.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Resneck JS Jr, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216.

- Lanzon J, Edwards SP, Inglehart MR. Choosing academia versus private practice: factors affecting oral maxillofacial surgery residents’ career choices. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1751-1761.

- AAMC Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2016_Debt_Fact_Card.pdf. Published October 2016. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH. The impact of U.S. medical students’ debt on their choice of primary care careers: an analysis of data from the 2002 medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2005;80:815-819.

- Woodworth PA, Chang FC, Helmer SD. Debt and other influences on career choices among surgical and primary care residents in a community-based hospital system. Am J Surg. 2000;180:570-575; discussion 575-576.

- Phillips RL Jr, Dodoo MS, Petterson S, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? Robert Graham Center website. http://www.graham-center.org/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/monographs-books/Specialty-geography-compressed.pdf. Published March 2, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Rosenthal MP, Marquette PA, Diamond JJ. Trends along the debt-income axis: implications for medical students’ selections of family practice careers. Acad Med. 1996;71:675-677.

- McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, et al. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:416-420.

- Careers in Medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/cim/specialty/exploreoptions/list/us/336836/dermatology.html. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Youngclaus JA, Koehler PA, Kotlikoff LJ, et al. Can medical students afford to choose primary care? an economic analysis of physician education debt repayment. Acad Med. 2013;88:16-25.

- Physician specialty data book 2014. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Physician Specialty Databook 2014.pdf. Published November 2014. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in National Institutes of Health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Resneck JS Jr, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216.

- Lanzon J, Edwards SP, Inglehart MR. Choosing academia versus private practice: factors affecting oral maxillofacial surgery residents’ career choices. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1751-1761.

- AAMC Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2016_Debt_Fact_Card.pdf. Published October 2016. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH. The impact of U.S. medical students’ debt on their choice of primary care careers: an analysis of data from the 2002 medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2005;80:815-819.

- Woodworth PA, Chang FC, Helmer SD. Debt and other influences on career choices among surgical and primary care residents in a community-based hospital system. Am J Surg. 2000;180:570-575; discussion 575-576.

- Phillips RL Jr, Dodoo MS, Petterson S, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? Robert Graham Center website. http://www.graham-center.org/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/monographs-books/Specialty-geography-compressed.pdf. Published March 2, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Rosenthal MP, Marquette PA, Diamond JJ. Trends along the debt-income axis: implications for medical students’ selections of family practice careers. Acad Med. 1996;71:675-677.

- McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, et al. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:416-420.

- Careers in Medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/cim/specialty/exploreoptions/list/us/336836/dermatology.html. Accessed November 18, 2017.

- Youngclaus JA, Koehler PA, Kotlikoff LJ, et al. Can medical students afford to choose primary care? an economic analysis of physician education debt repayment. Acad Med. 2013;88:16-25.

- Physician specialty data book 2014. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Physician Specialty Databook 2014.pdf. Published November 2014. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed November 17, 2017.

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in National Institutes of Health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888.

Practice Points

- Academic dermatology departments are facing challenges in recruiting physicians, raising concerns for the future of dermatology education and research.

- Large amounts of student loan burden may influence career plans in dermatology.

- Dermatologists may not be fully knowledgeable of loan repayment options; thus, education on this topic should be prioritized by dermatology training programs.