User login

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has a devastating impact on individuals and society because of its high prevalence, its recurrent nature, its frequent comorbidity with other disorders, and the functional impairment it causes. Compared with other chronic diseases, such as arthritis, asthma, and diabetes, MDD produces the greatest decrement in health worldwide.1 The goals in treating MDD should be not just to reduce symptom severity but also to achieve continuing remission and lower the risk for relapse.2

Antidepressants are the most common treatment for depression.3 Among psychotherapies used to treat MDD, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been identified as an effective treatment.4 Collaborative care models have been reported to manage MDD more effectively.5 In this article, we review the evidence supporting the use of CBT as monotherapy and in combination with antidepressants for acute and long-term treatment of MDD.

Acute treatment: Not too soon for CBT

Mild to moderate depression

Research has indicated that for the treatment of mild MDD, antidepressants are unlikely to be more effective than placebo.6,7 Studies also have reported that response to antidepressants begins to outpace response to placebo only when symptoms are no longer mild. Using antidepressants for patients with mild depression could therefore place them at risk of overtreatment.8 In keeping with these findings, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has recommended the use of evidence-based psychotherapies, such as CBT, as an initial treatment choice for patients with mild to moderate MDD.9

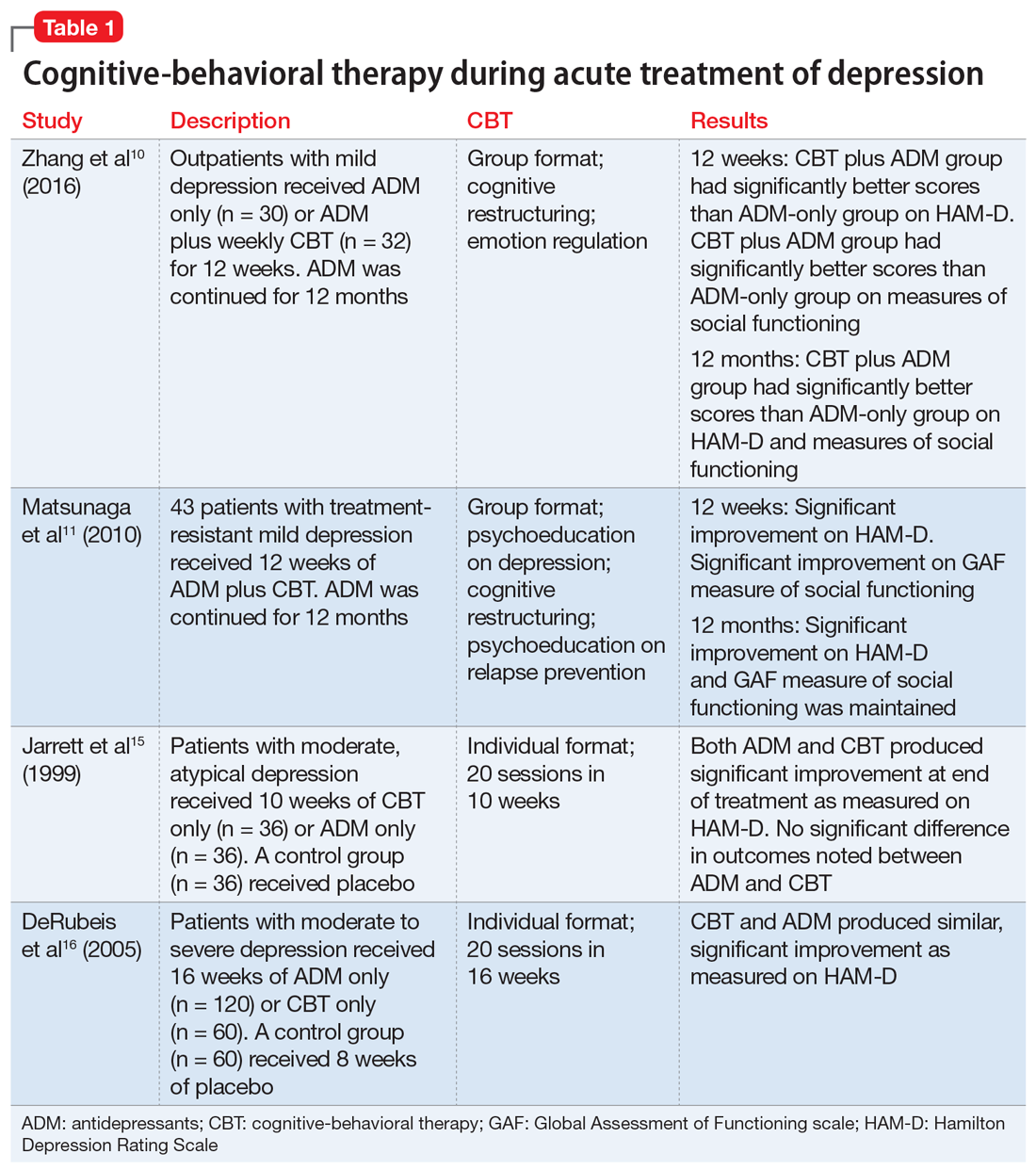

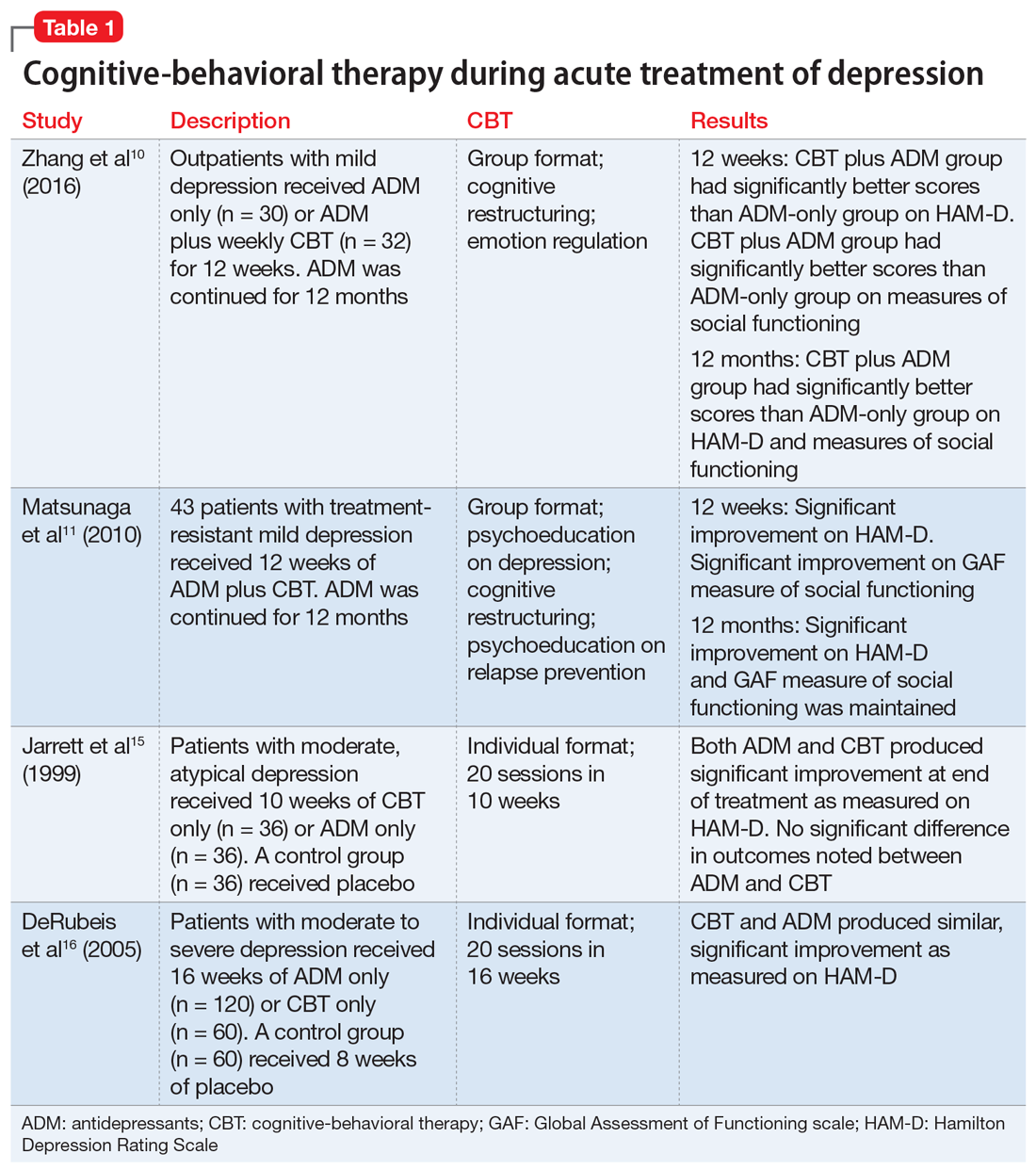

Two recent studies have suggested that the combination of CBT plus antidepressants could boost improvement in psychosocial functioning for patients with mild MDD.10,11 However, neither study included a group of patients who received only CBT to evaluate if CBT alone could have also produced similar effects. Other limitations include the lack of a control group in one study and small sample sizes in both studies. However, both studies had a long follow-up period and specifically studied the impact on psychosocial functioning.

Moderate to severe depression

Earlier depression treatment guidelines suggested that antidepressants should be used to treat more severe depression, while psychotherapy should be used mainly for mild depression.12 This recommendation was influenced by the well-known National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) that used a placebo control.13 In this study, CBT was compared with antidepressants and found to be no more effective than placebo for more severely depressed patients.13 However, this finding was not consistent across the 3 sites where the study was conducted; at the site where CBT was provided by more experienced CBT therapists, patients with more severe depression who received CBT fared as well as patients treated with antidepressants.14 A later double-blind RCT that used experienced therapists found that CBT was as effective as antidepressants (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), and both treatments were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of atypical depression.15

Another placebo-controlled RCT conducted at 2 sites found that CBT was as effective as antidepressants in the treatment of moderately to severely depressed patients. As in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program trial,13 in this study, there were indications that the results were dependent on therapist experience.16 These findings suggest that the experience of the therapist is an important factor.

A recent meta-analysis of treatments of the acute phase of MDD compared 11 RCTs of CBT and second-generation antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and other medications with related mechanisms of action).17 It found that as a first-step treatment, CBT and antidepressants had a similar impact on symptom relief in patients with moderate to severe depression. Patients treated with antidepressants also had a higher risk of experiencing adverse events or discontinuing treatment because of adverse events. However, this meta-analysis included trials that had methodological shortcomings, which reduces the strength of these conclusions.

Continue to: Patients with MDD and comorbid personality disorders have been...

Patients with MDD and comorbid personality disorders have been reported to have poorer outcomes, regardless of the treatment used.18 Fournier et al19 examined the impact of antidepressants and CBT in moderately to severely depressed patients with and without a personality disorder. They found that a combination of antidepressants and CBT was suitable for patients with personality disorders because antidepressants would boost the initial response and CBT would help sustain improvement in the long term.

Presently, the APA suggests that the combination of psychotherapy and antidepressants may be used as an initial treatment for patients with moderate to severe MDD.9 As research brings to light other factors that affect treatment outcomes, these guidelines could change.

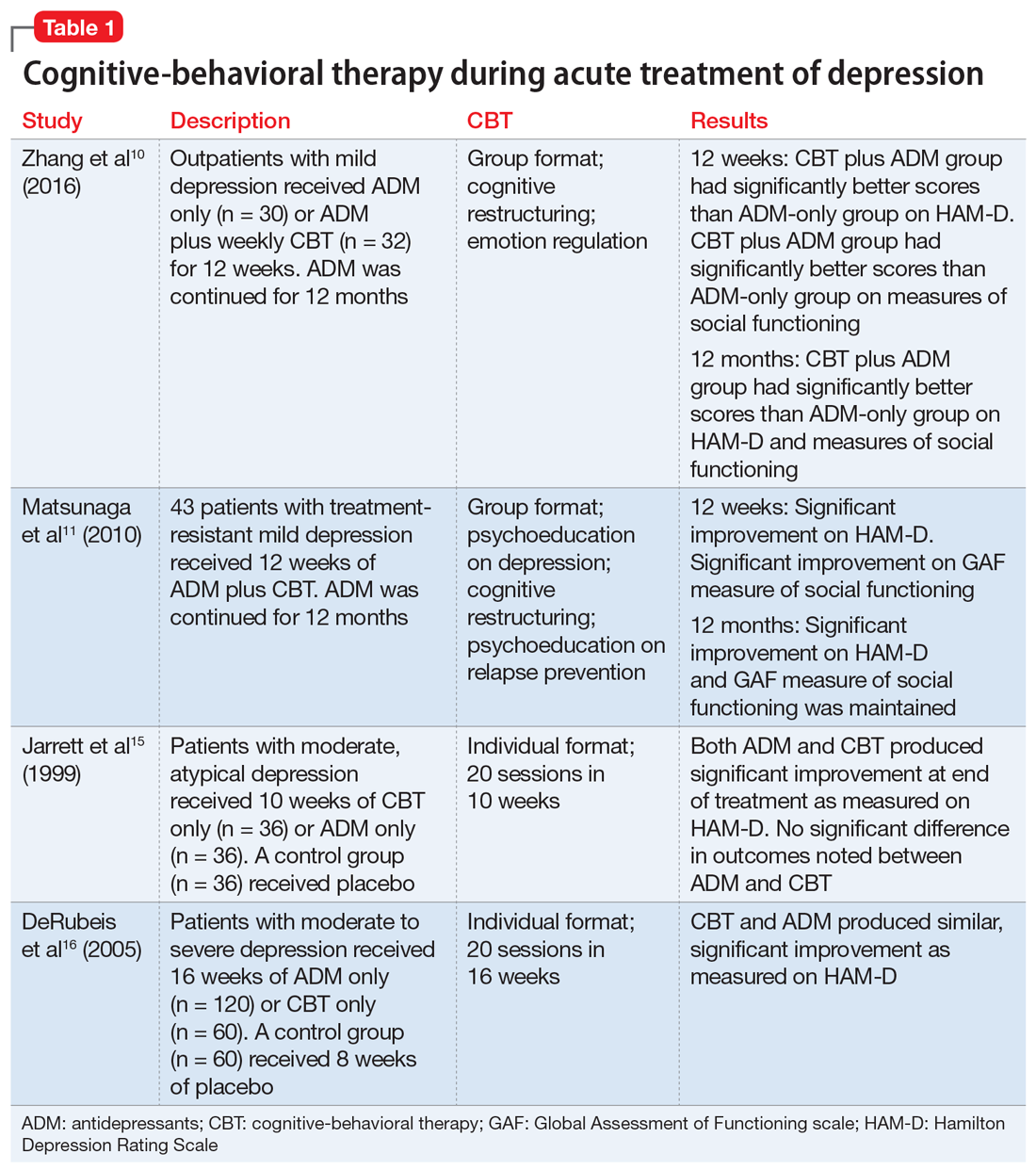

Table 110,11,15,16 summarizes the findings of select studies evaluating the use of CBT for the acute treatment of depression.

CBT’s role in long-term treatment

Recurrence and relapse are major problems associated with MDD. The large majority of individuals who experience an episode of depression go on to experience more episodes of depression,20 and the risk of recurrence increases after each successive episode.21

To reduce the risk of relapse and the return of symptoms, it is recommended that patients treated with antidepressants continue pharmacotherapy for 4 to 9 months after remission.9 Maintenance pharmacotherapy, which involves keeping patients on antidepressants beyond the point of recovery, is intended to reduce the risk of recurrence, and is standard treatment for patients with chronic or recurrent MDD.22 However, this preventive effect exists only while the patient continues to take the medication. Rates of symptom recurrence following medication withdrawal are often high regardless of how long patients have taken medications.23

Continue to: Studies examining CBT as a maintenance treatment...

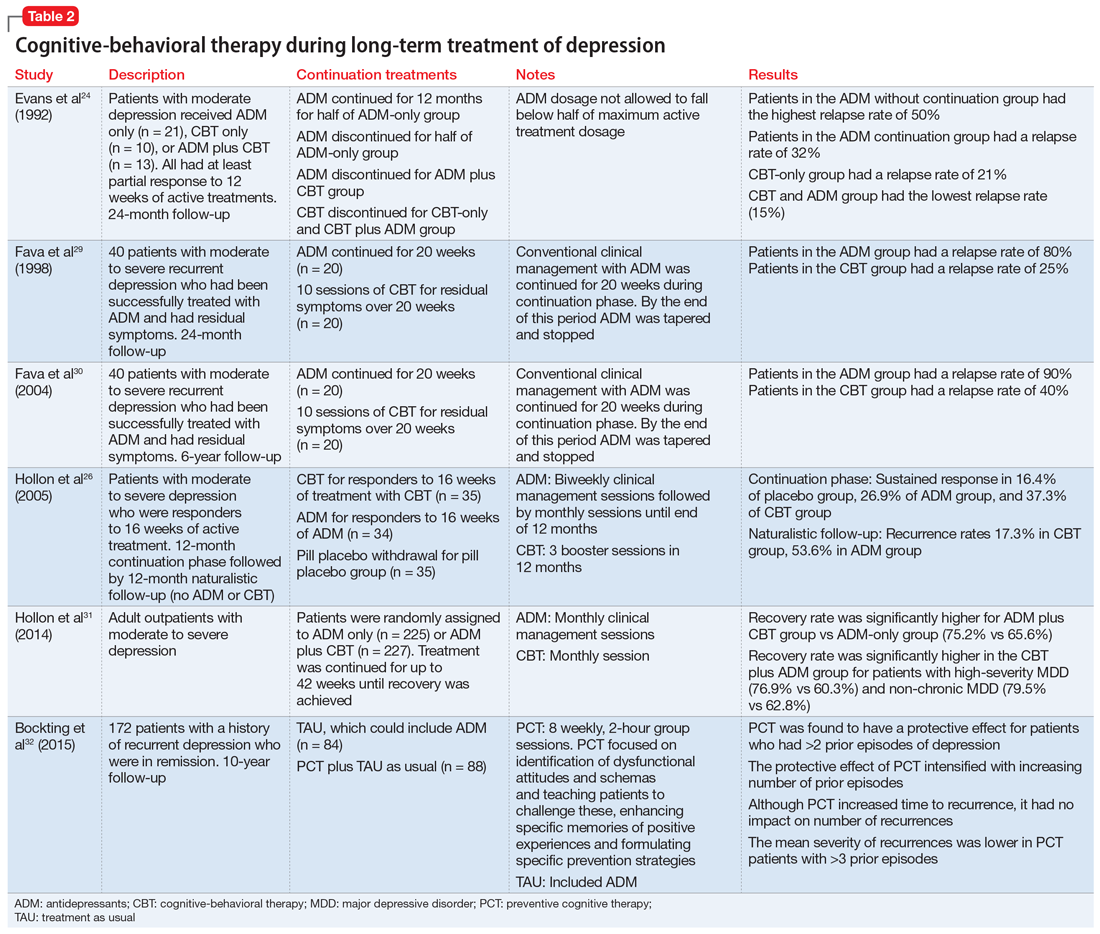

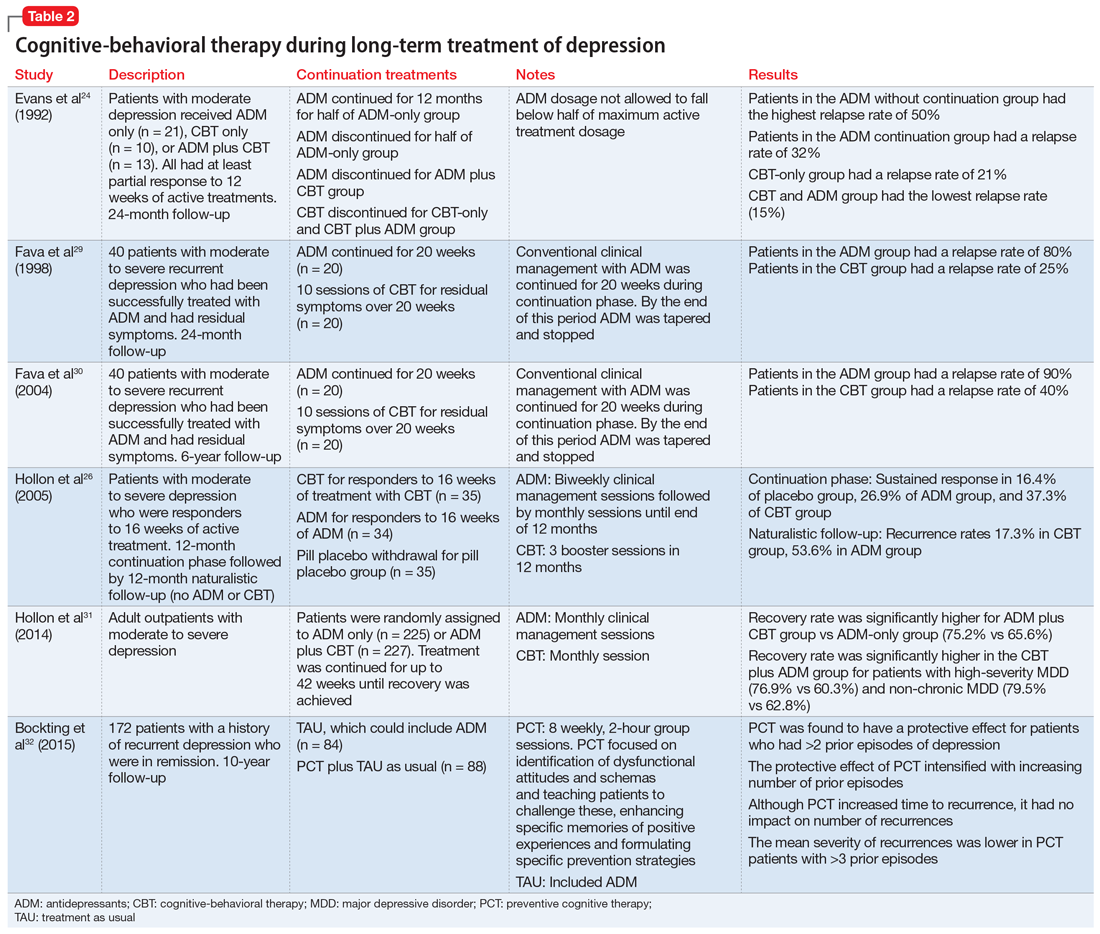

Studies examining CBT as a maintenance treatment—provided alone or in combination with or sequentially with antidepressants—have found it has an enduring effect that extends beyond the end of treatment and equals the impact of continuing antidepressants.24-27 A recent meta-analysis of 10 trials where CBT had been provided to patients after acute treatment found that the risk of relapse was reduced by 21% in the first year and by 28% in the first 2 years.28

Studies have compared the prophylactic impact of maintenance CBT and antidepressants. In an early study, 40 patients who had been successfully treated with antidepressants but had residual symptoms were randomly assigned to 20 weeks of CBT or to clinical management.29 By the end of 20 weeks, patients were tapered off their antidepressant. All patients were then followed for 2 years, during which time they received no treatment. At the 2-year follow-up, the CBT group had a relapse rate of 25%, compared with 80% in the antidepressant group.29 Weaknesses of this study include a small sample size, and the fact that a single therapist provided the CBT.

This study was extended to a 6-year follow-up; antidepressants were prescribed only to patients who relapsed. The CBT group continued to have a significantly lower relapse rate (40%) compared with the antidepressant group (90%).30

In another RCT, patients with depression who had recovered with CBT or medication continued with the same treatment during a maintenance phase.26 The CBT group received 3 booster sessions during the next year and antidepressant group received medication. At the end of the second year (without CBT or medication) CBT patients were less likely to relapse compared with patients receiving antidepressants. The adjusted relapse rates were 17.3% for CBT and 53.6% for antidepressants.26

An RCT that included 452 patients with severe depression used a long intervention period (up to 42 weeks) and a flexible treatment algorithm to more closely model the strategies used in clinical practice.31 Patients were randomly assigned to antidepressants only or in combination with CBT. At the end of 12 months, outcome assessment by blinded interviewers indicated that patients with more severe depression were more likely to benefit from the combination of antidepressants and CBT (76.9% vs 60.3%) and those with severe, non-chronic depression received the most benefit (79.5% vs 62.8%). The lack of a CBT-only group limits the generalizability of these findings. Neither patients nor clinicians were blinded to the treatment assignment, which is a common limitation in psychotherapy studies but could have contributed to the finding that combined treatment was more effective.

Continue to: Some evidence suggests...

Some evidence suggests that augmenting treatment as usual (TAU) with CBT can have a resilient protective impact that also intensifies with the number of depressive episodes experienced. In an RCT, 172 patients with depression in remission were randomly assigned to TAU or to TAU augmented with CBT.32 The time to recurrence was assessed over the course of 10 years. Augmenting TAU with CBT had a significant protective impact that was greater for patients who had >3 previous episodes.32

Another long-term study assessed the longitudinal course of 158 patients who received CBT, medication, and clinical management, or medication and clinical management alone.33 Patients were followed 6 years after randomization (4.5 years after completion of CBT). Researchers found the effects of CBT in preventing relapse and recurrence persisted for several years.33

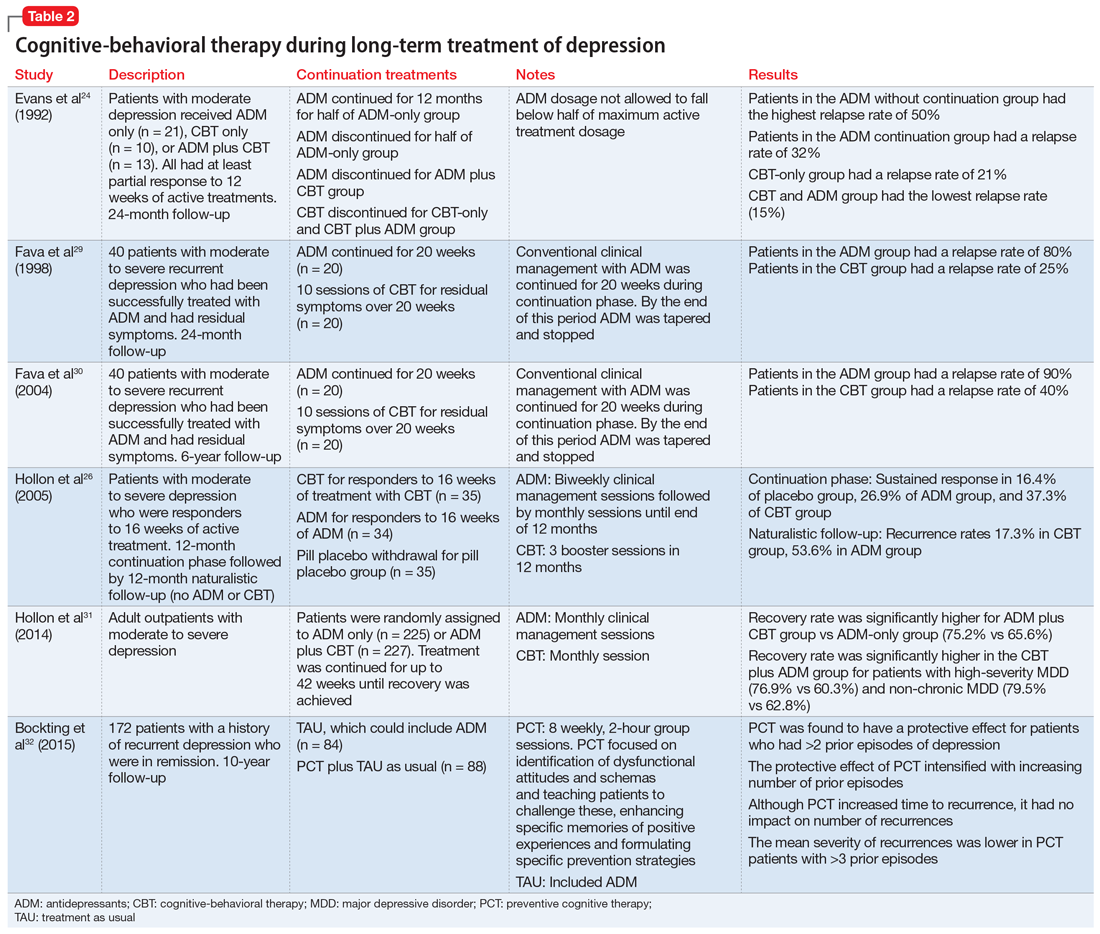

Table 224,26,29-32 summarizes the findings of select studies evaluating the use of CBT for the long-term treatment of depression.

Limitations of long-term studies

Studies that have examined the efficacy of adding CBT to antidepressants in the continuation and maintenance treatment of patients with MDD have had some limitations. The definitions of relapse and recurrence have not always been clearly delineated in all studies. This is important because recurrence rates tend to be lower, and long-term follow-up would be needed to detect multiple recurrences so that their incidence is not underestimated. In addition, the types of CBT interventions utilized has varied across studies. Some studies have employed standard interventions such as cognitive restructuring, while others have added strategies that focus on enhancing memories for positive experiences or interventions to encourage medication adherence. Despite these limitations, research has shown promising results and suggests that adding CBT to the maintenance treatment of patients with depression—with or without antidepressants—is likely to reduce the rate of relapse and recurrence.

Consider CBT for all depressed patients

Research indicates that CBT can be the preferred treatment for patients with mild to moderate MDD. Antidepressants significantly reduce depressive symptoms in patients with moderate to severe MDD. Some research suggests that CBT can be as effective as antidepressants for moderate and severe MDD. However, as the severity and chronicity of depression increase, other moderating factors need to be considered. The expertise of the CBT therapist has an impact on outcomes. Treatment protocols that utilize CBT plus antidepressants are likely to be more effective than CBT or antidepressants alone. Incorporating CBT in the acute phase of depression treatment, with or without antidepressants, can have a long-term impact. For maintenance treatment, CBT alone and CBT plus antidepressants have been found to help sustain remission.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can be an effective treatment for patients with major depressive disorder, regardless of symptom severity. The expertise of the clinician who provides CBT has a substantial impact on outcomes. Combination treatment with CBT plus antidepressants is more likely to be effective than either treatment alone.

Related Resources

- Flynn HA, Warren R. Using CBT effectively for treating depression and anxiety. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(6):45-53.

- Ijaz S, Davies P, Williams CJ, et al. Psychological therapies for treatment-resistant depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD010558.

1. Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851-858.

2. Keller MB. Past, present, and future directions for defining optimal treatment outcome in depression: remission and beyond. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3152-3160.

3. Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265-1273.

4. Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685-716.

5. Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Schulberg HC. Evidence-based models of integrated management of depression in primary care. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28(4):1061-1077.

6. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47-53.

7. Paykel ES, Hollyman JA, Freeling P, et al. Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 1988;14(1):83-95

8. Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265-1273.

9. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

10. Zhang B, Ding X, Lu W, et al. Effect of group cognitive-behavioral therapy on the quality of life and social functioning of patients with mild depression. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):18-27.

11. Matsunaga M, Okamoto Y, Suzuki S et.al. Psychosocial functioning in patients with treatment-resistant depression after group cognitive behavioral therapy. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:22.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(suppl 4):1-26.

13. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-982; discussion 983.

14. Jacobson NS, Hollon SD. Prospects for future comparisons between drugs and psychotherapy: lessons from the CBT-versus-pharmacotherapy exchange. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):104-108.

15. Jarrett RB, Schaffer M, McIntire D, et al. Treatment of atypical depression with cognitive therapy or phenelzine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(5):431-437.

16. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409-416.

17. Amick HR, Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second generation antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapies in initial treatment of major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h6019. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6019.

18. Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T. Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(1):13-20.

19. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Antidepressant medications v. cognitive therapy in people with depression with or without personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):124-129.

20. Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, et al. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1000-1006.

21. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):229-233.

22. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):851-855.

23. Thase ME. Relapse and recurrence of depression: an updated practical approach for prevention. In: Palmer KJ, ed. Drug treatment issues in depression. Auckland, New Zealand: Adis International; 2000:35-52.

24. Evans MD, Hollon, SD, DeRubeis RJ, et al. Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):802-808.

25. Vittengal JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, et al. Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(3):475-488.

26. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):417-422.

27. Paykel ES, Scott J, Teasdale JD, et al. Prevention of relapse in residual depression by cognitive therapy: a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(9):829-835.

28. Clarke K, Mayo-Wilson E, Kenny J, et al. Can non-pharmacological interventions prevent relapse in adults who have recovered from depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:58-70.

29. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Grandi, S, et al. Prevention of recurrent depression with cognitive behavioral therapy: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(9):816-820.

30. Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, et al. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(10):1872-1876.

31. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Fawcett J, et al. Effect of cognitive therapy with antidepressant medications vs antidepressants alone on the rate of recovery in major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1157-1164.

32. Bockting CL, Smid NH, Koeter MW, et al. Enduring effects of preventive cognitive therapy in adults remitted from recurrent depression: a 10 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:188-194.

33. Paykel ES, Scott J, Cornwall PL, et al. Duration of relapse prevention after cognitive therapy in residual depression: follow-up of controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2005;35(1):59-68.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has a devastating impact on individuals and society because of its high prevalence, its recurrent nature, its frequent comorbidity with other disorders, and the functional impairment it causes. Compared with other chronic diseases, such as arthritis, asthma, and diabetes, MDD produces the greatest decrement in health worldwide.1 The goals in treating MDD should be not just to reduce symptom severity but also to achieve continuing remission and lower the risk for relapse.2

Antidepressants are the most common treatment for depression.3 Among psychotherapies used to treat MDD, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been identified as an effective treatment.4 Collaborative care models have been reported to manage MDD more effectively.5 In this article, we review the evidence supporting the use of CBT as monotherapy and in combination with antidepressants for acute and long-term treatment of MDD.

Acute treatment: Not too soon for CBT

Mild to moderate depression

Research has indicated that for the treatment of mild MDD, antidepressants are unlikely to be more effective than placebo.6,7 Studies also have reported that response to antidepressants begins to outpace response to placebo only when symptoms are no longer mild. Using antidepressants for patients with mild depression could therefore place them at risk of overtreatment.8 In keeping with these findings, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has recommended the use of evidence-based psychotherapies, such as CBT, as an initial treatment choice for patients with mild to moderate MDD.9

Two recent studies have suggested that the combination of CBT plus antidepressants could boost improvement in psychosocial functioning for patients with mild MDD.10,11 However, neither study included a group of patients who received only CBT to evaluate if CBT alone could have also produced similar effects. Other limitations include the lack of a control group in one study and small sample sizes in both studies. However, both studies had a long follow-up period and specifically studied the impact on psychosocial functioning.

Moderate to severe depression

Earlier depression treatment guidelines suggested that antidepressants should be used to treat more severe depression, while psychotherapy should be used mainly for mild depression.12 This recommendation was influenced by the well-known National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) that used a placebo control.13 In this study, CBT was compared with antidepressants and found to be no more effective than placebo for more severely depressed patients.13 However, this finding was not consistent across the 3 sites where the study was conducted; at the site where CBT was provided by more experienced CBT therapists, patients with more severe depression who received CBT fared as well as patients treated with antidepressants.14 A later double-blind RCT that used experienced therapists found that CBT was as effective as antidepressants (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), and both treatments were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of atypical depression.15

Another placebo-controlled RCT conducted at 2 sites found that CBT was as effective as antidepressants in the treatment of moderately to severely depressed patients. As in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program trial,13 in this study, there were indications that the results were dependent on therapist experience.16 These findings suggest that the experience of the therapist is an important factor.

A recent meta-analysis of treatments of the acute phase of MDD compared 11 RCTs of CBT and second-generation antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and other medications with related mechanisms of action).17 It found that as a first-step treatment, CBT and antidepressants had a similar impact on symptom relief in patients with moderate to severe depression. Patients treated with antidepressants also had a higher risk of experiencing adverse events or discontinuing treatment because of adverse events. However, this meta-analysis included trials that had methodological shortcomings, which reduces the strength of these conclusions.

Continue to: Patients with MDD and comorbid personality disorders have been...

Patients with MDD and comorbid personality disorders have been reported to have poorer outcomes, regardless of the treatment used.18 Fournier et al19 examined the impact of antidepressants and CBT in moderately to severely depressed patients with and without a personality disorder. They found that a combination of antidepressants and CBT was suitable for patients with personality disorders because antidepressants would boost the initial response and CBT would help sustain improvement in the long term.

Presently, the APA suggests that the combination of psychotherapy and antidepressants may be used as an initial treatment for patients with moderate to severe MDD.9 As research brings to light other factors that affect treatment outcomes, these guidelines could change.

Table 110,11,15,16 summarizes the findings of select studies evaluating the use of CBT for the acute treatment of depression.

CBT’s role in long-term treatment

Recurrence and relapse are major problems associated with MDD. The large majority of individuals who experience an episode of depression go on to experience more episodes of depression,20 and the risk of recurrence increases after each successive episode.21

To reduce the risk of relapse and the return of symptoms, it is recommended that patients treated with antidepressants continue pharmacotherapy for 4 to 9 months after remission.9 Maintenance pharmacotherapy, which involves keeping patients on antidepressants beyond the point of recovery, is intended to reduce the risk of recurrence, and is standard treatment for patients with chronic or recurrent MDD.22 However, this preventive effect exists only while the patient continues to take the medication. Rates of symptom recurrence following medication withdrawal are often high regardless of how long patients have taken medications.23

Continue to: Studies examining CBT as a maintenance treatment...

Studies examining CBT as a maintenance treatment—provided alone or in combination with or sequentially with antidepressants—have found it has an enduring effect that extends beyond the end of treatment and equals the impact of continuing antidepressants.24-27 A recent meta-analysis of 10 trials where CBT had been provided to patients after acute treatment found that the risk of relapse was reduced by 21% in the first year and by 28% in the first 2 years.28

Studies have compared the prophylactic impact of maintenance CBT and antidepressants. In an early study, 40 patients who had been successfully treated with antidepressants but had residual symptoms were randomly assigned to 20 weeks of CBT or to clinical management.29 By the end of 20 weeks, patients were tapered off their antidepressant. All patients were then followed for 2 years, during which time they received no treatment. At the 2-year follow-up, the CBT group had a relapse rate of 25%, compared with 80% in the antidepressant group.29 Weaknesses of this study include a small sample size, and the fact that a single therapist provided the CBT.

This study was extended to a 6-year follow-up; antidepressants were prescribed only to patients who relapsed. The CBT group continued to have a significantly lower relapse rate (40%) compared with the antidepressant group (90%).30

In another RCT, patients with depression who had recovered with CBT or medication continued with the same treatment during a maintenance phase.26 The CBT group received 3 booster sessions during the next year and antidepressant group received medication. At the end of the second year (without CBT or medication) CBT patients were less likely to relapse compared with patients receiving antidepressants. The adjusted relapse rates were 17.3% for CBT and 53.6% for antidepressants.26

An RCT that included 452 patients with severe depression used a long intervention period (up to 42 weeks) and a flexible treatment algorithm to more closely model the strategies used in clinical practice.31 Patients were randomly assigned to antidepressants only or in combination with CBT. At the end of 12 months, outcome assessment by blinded interviewers indicated that patients with more severe depression were more likely to benefit from the combination of antidepressants and CBT (76.9% vs 60.3%) and those with severe, non-chronic depression received the most benefit (79.5% vs 62.8%). The lack of a CBT-only group limits the generalizability of these findings. Neither patients nor clinicians were blinded to the treatment assignment, which is a common limitation in psychotherapy studies but could have contributed to the finding that combined treatment was more effective.

Continue to: Some evidence suggests...

Some evidence suggests that augmenting treatment as usual (TAU) with CBT can have a resilient protective impact that also intensifies with the number of depressive episodes experienced. In an RCT, 172 patients with depression in remission were randomly assigned to TAU or to TAU augmented with CBT.32 The time to recurrence was assessed over the course of 10 years. Augmenting TAU with CBT had a significant protective impact that was greater for patients who had >3 previous episodes.32

Another long-term study assessed the longitudinal course of 158 patients who received CBT, medication, and clinical management, or medication and clinical management alone.33 Patients were followed 6 years after randomization (4.5 years after completion of CBT). Researchers found the effects of CBT in preventing relapse and recurrence persisted for several years.33

Table 224,26,29-32 summarizes the findings of select studies evaluating the use of CBT for the long-term treatment of depression.

Limitations of long-term studies

Studies that have examined the efficacy of adding CBT to antidepressants in the continuation and maintenance treatment of patients with MDD have had some limitations. The definitions of relapse and recurrence have not always been clearly delineated in all studies. This is important because recurrence rates tend to be lower, and long-term follow-up would be needed to detect multiple recurrences so that their incidence is not underestimated. In addition, the types of CBT interventions utilized has varied across studies. Some studies have employed standard interventions such as cognitive restructuring, while others have added strategies that focus on enhancing memories for positive experiences or interventions to encourage medication adherence. Despite these limitations, research has shown promising results and suggests that adding CBT to the maintenance treatment of patients with depression—with or without antidepressants—is likely to reduce the rate of relapse and recurrence.

Consider CBT for all depressed patients

Research indicates that CBT can be the preferred treatment for patients with mild to moderate MDD. Antidepressants significantly reduce depressive symptoms in patients with moderate to severe MDD. Some research suggests that CBT can be as effective as antidepressants for moderate and severe MDD. However, as the severity and chronicity of depression increase, other moderating factors need to be considered. The expertise of the CBT therapist has an impact on outcomes. Treatment protocols that utilize CBT plus antidepressants are likely to be more effective than CBT or antidepressants alone. Incorporating CBT in the acute phase of depression treatment, with or without antidepressants, can have a long-term impact. For maintenance treatment, CBT alone and CBT plus antidepressants have been found to help sustain remission.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can be an effective treatment for patients with major depressive disorder, regardless of symptom severity. The expertise of the clinician who provides CBT has a substantial impact on outcomes. Combination treatment with CBT plus antidepressants is more likely to be effective than either treatment alone.

Related Resources

- Flynn HA, Warren R. Using CBT effectively for treating depression and anxiety. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(6):45-53.

- Ijaz S, Davies P, Williams CJ, et al. Psychological therapies for treatment-resistant depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD010558.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has a devastating impact on individuals and society because of its high prevalence, its recurrent nature, its frequent comorbidity with other disorders, and the functional impairment it causes. Compared with other chronic diseases, such as arthritis, asthma, and diabetes, MDD produces the greatest decrement in health worldwide.1 The goals in treating MDD should be not just to reduce symptom severity but also to achieve continuing remission and lower the risk for relapse.2

Antidepressants are the most common treatment for depression.3 Among psychotherapies used to treat MDD, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been identified as an effective treatment.4 Collaborative care models have been reported to manage MDD more effectively.5 In this article, we review the evidence supporting the use of CBT as monotherapy and in combination with antidepressants for acute and long-term treatment of MDD.

Acute treatment: Not too soon for CBT

Mild to moderate depression

Research has indicated that for the treatment of mild MDD, antidepressants are unlikely to be more effective than placebo.6,7 Studies also have reported that response to antidepressants begins to outpace response to placebo only when symptoms are no longer mild. Using antidepressants for patients with mild depression could therefore place them at risk of overtreatment.8 In keeping with these findings, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has recommended the use of evidence-based psychotherapies, such as CBT, as an initial treatment choice for patients with mild to moderate MDD.9

Two recent studies have suggested that the combination of CBT plus antidepressants could boost improvement in psychosocial functioning for patients with mild MDD.10,11 However, neither study included a group of patients who received only CBT to evaluate if CBT alone could have also produced similar effects. Other limitations include the lack of a control group in one study and small sample sizes in both studies. However, both studies had a long follow-up period and specifically studied the impact on psychosocial functioning.

Moderate to severe depression

Earlier depression treatment guidelines suggested that antidepressants should be used to treat more severe depression, while psychotherapy should be used mainly for mild depression.12 This recommendation was influenced by the well-known National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) that used a placebo control.13 In this study, CBT was compared with antidepressants and found to be no more effective than placebo for more severely depressed patients.13 However, this finding was not consistent across the 3 sites where the study was conducted; at the site where CBT was provided by more experienced CBT therapists, patients with more severe depression who received CBT fared as well as patients treated with antidepressants.14 A later double-blind RCT that used experienced therapists found that CBT was as effective as antidepressants (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), and both treatments were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of atypical depression.15

Another placebo-controlled RCT conducted at 2 sites found that CBT was as effective as antidepressants in the treatment of moderately to severely depressed patients. As in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program trial,13 in this study, there were indications that the results were dependent on therapist experience.16 These findings suggest that the experience of the therapist is an important factor.

A recent meta-analysis of treatments of the acute phase of MDD compared 11 RCTs of CBT and second-generation antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and other medications with related mechanisms of action).17 It found that as a first-step treatment, CBT and antidepressants had a similar impact on symptom relief in patients with moderate to severe depression. Patients treated with antidepressants also had a higher risk of experiencing adverse events or discontinuing treatment because of adverse events. However, this meta-analysis included trials that had methodological shortcomings, which reduces the strength of these conclusions.

Continue to: Patients with MDD and comorbid personality disorders have been...

Patients with MDD and comorbid personality disorders have been reported to have poorer outcomes, regardless of the treatment used.18 Fournier et al19 examined the impact of antidepressants and CBT in moderately to severely depressed patients with and without a personality disorder. They found that a combination of antidepressants and CBT was suitable for patients with personality disorders because antidepressants would boost the initial response and CBT would help sustain improvement in the long term.

Presently, the APA suggests that the combination of psychotherapy and antidepressants may be used as an initial treatment for patients with moderate to severe MDD.9 As research brings to light other factors that affect treatment outcomes, these guidelines could change.

Table 110,11,15,16 summarizes the findings of select studies evaluating the use of CBT for the acute treatment of depression.

CBT’s role in long-term treatment

Recurrence and relapse are major problems associated with MDD. The large majority of individuals who experience an episode of depression go on to experience more episodes of depression,20 and the risk of recurrence increases after each successive episode.21

To reduce the risk of relapse and the return of symptoms, it is recommended that patients treated with antidepressants continue pharmacotherapy for 4 to 9 months after remission.9 Maintenance pharmacotherapy, which involves keeping patients on antidepressants beyond the point of recovery, is intended to reduce the risk of recurrence, and is standard treatment for patients with chronic or recurrent MDD.22 However, this preventive effect exists only while the patient continues to take the medication. Rates of symptom recurrence following medication withdrawal are often high regardless of how long patients have taken medications.23

Continue to: Studies examining CBT as a maintenance treatment...

Studies examining CBT as a maintenance treatment—provided alone or in combination with or sequentially with antidepressants—have found it has an enduring effect that extends beyond the end of treatment and equals the impact of continuing antidepressants.24-27 A recent meta-analysis of 10 trials where CBT had been provided to patients after acute treatment found that the risk of relapse was reduced by 21% in the first year and by 28% in the first 2 years.28

Studies have compared the prophylactic impact of maintenance CBT and antidepressants. In an early study, 40 patients who had been successfully treated with antidepressants but had residual symptoms were randomly assigned to 20 weeks of CBT or to clinical management.29 By the end of 20 weeks, patients were tapered off their antidepressant. All patients were then followed for 2 years, during which time they received no treatment. At the 2-year follow-up, the CBT group had a relapse rate of 25%, compared with 80% in the antidepressant group.29 Weaknesses of this study include a small sample size, and the fact that a single therapist provided the CBT.

This study was extended to a 6-year follow-up; antidepressants were prescribed only to patients who relapsed. The CBT group continued to have a significantly lower relapse rate (40%) compared with the antidepressant group (90%).30

In another RCT, patients with depression who had recovered with CBT or medication continued with the same treatment during a maintenance phase.26 The CBT group received 3 booster sessions during the next year and antidepressant group received medication. At the end of the second year (without CBT or medication) CBT patients were less likely to relapse compared with patients receiving antidepressants. The adjusted relapse rates were 17.3% for CBT and 53.6% for antidepressants.26

An RCT that included 452 patients with severe depression used a long intervention period (up to 42 weeks) and a flexible treatment algorithm to more closely model the strategies used in clinical practice.31 Patients were randomly assigned to antidepressants only or in combination with CBT. At the end of 12 months, outcome assessment by blinded interviewers indicated that patients with more severe depression were more likely to benefit from the combination of antidepressants and CBT (76.9% vs 60.3%) and those with severe, non-chronic depression received the most benefit (79.5% vs 62.8%). The lack of a CBT-only group limits the generalizability of these findings. Neither patients nor clinicians were blinded to the treatment assignment, which is a common limitation in psychotherapy studies but could have contributed to the finding that combined treatment was more effective.

Continue to: Some evidence suggests...

Some evidence suggests that augmenting treatment as usual (TAU) with CBT can have a resilient protective impact that also intensifies with the number of depressive episodes experienced. In an RCT, 172 patients with depression in remission were randomly assigned to TAU or to TAU augmented with CBT.32 The time to recurrence was assessed over the course of 10 years. Augmenting TAU with CBT had a significant protective impact that was greater for patients who had >3 previous episodes.32

Another long-term study assessed the longitudinal course of 158 patients who received CBT, medication, and clinical management, or medication and clinical management alone.33 Patients were followed 6 years after randomization (4.5 years after completion of CBT). Researchers found the effects of CBT in preventing relapse and recurrence persisted for several years.33

Table 224,26,29-32 summarizes the findings of select studies evaluating the use of CBT for the long-term treatment of depression.

Limitations of long-term studies

Studies that have examined the efficacy of adding CBT to antidepressants in the continuation and maintenance treatment of patients with MDD have had some limitations. The definitions of relapse and recurrence have not always been clearly delineated in all studies. This is important because recurrence rates tend to be lower, and long-term follow-up would be needed to detect multiple recurrences so that their incidence is not underestimated. In addition, the types of CBT interventions utilized has varied across studies. Some studies have employed standard interventions such as cognitive restructuring, while others have added strategies that focus on enhancing memories for positive experiences or interventions to encourage medication adherence. Despite these limitations, research has shown promising results and suggests that adding CBT to the maintenance treatment of patients with depression—with or without antidepressants—is likely to reduce the rate of relapse and recurrence.

Consider CBT for all depressed patients

Research indicates that CBT can be the preferred treatment for patients with mild to moderate MDD. Antidepressants significantly reduce depressive symptoms in patients with moderate to severe MDD. Some research suggests that CBT can be as effective as antidepressants for moderate and severe MDD. However, as the severity and chronicity of depression increase, other moderating factors need to be considered. The expertise of the CBT therapist has an impact on outcomes. Treatment protocols that utilize CBT plus antidepressants are likely to be more effective than CBT or antidepressants alone. Incorporating CBT in the acute phase of depression treatment, with or without antidepressants, can have a long-term impact. For maintenance treatment, CBT alone and CBT plus antidepressants have been found to help sustain remission.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can be an effective treatment for patients with major depressive disorder, regardless of symptom severity. The expertise of the clinician who provides CBT has a substantial impact on outcomes. Combination treatment with CBT plus antidepressants is more likely to be effective than either treatment alone.

Related Resources

- Flynn HA, Warren R. Using CBT effectively for treating depression and anxiety. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(6):45-53.

- Ijaz S, Davies P, Williams CJ, et al. Psychological therapies for treatment-resistant depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD010558.

1. Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851-858.

2. Keller MB. Past, present, and future directions for defining optimal treatment outcome in depression: remission and beyond. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3152-3160.

3. Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265-1273.

4. Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685-716.

5. Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Schulberg HC. Evidence-based models of integrated management of depression in primary care. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28(4):1061-1077.

6. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47-53.

7. Paykel ES, Hollyman JA, Freeling P, et al. Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 1988;14(1):83-95

8. Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265-1273.

9. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

10. Zhang B, Ding X, Lu W, et al. Effect of group cognitive-behavioral therapy on the quality of life and social functioning of patients with mild depression. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):18-27.

11. Matsunaga M, Okamoto Y, Suzuki S et.al. Psychosocial functioning in patients with treatment-resistant depression after group cognitive behavioral therapy. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:22.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(suppl 4):1-26.

13. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-982; discussion 983.

14. Jacobson NS, Hollon SD. Prospects for future comparisons between drugs and psychotherapy: lessons from the CBT-versus-pharmacotherapy exchange. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):104-108.

15. Jarrett RB, Schaffer M, McIntire D, et al. Treatment of atypical depression with cognitive therapy or phenelzine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(5):431-437.

16. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409-416.

17. Amick HR, Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second generation antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapies in initial treatment of major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h6019. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6019.

18. Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T. Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(1):13-20.

19. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Antidepressant medications v. cognitive therapy in people with depression with or without personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):124-129.

20. Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, et al. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1000-1006.

21. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):229-233.

22. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):851-855.

23. Thase ME. Relapse and recurrence of depression: an updated practical approach for prevention. In: Palmer KJ, ed. Drug treatment issues in depression. Auckland, New Zealand: Adis International; 2000:35-52.

24. Evans MD, Hollon, SD, DeRubeis RJ, et al. Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):802-808.

25. Vittengal JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, et al. Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(3):475-488.

26. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):417-422.

27. Paykel ES, Scott J, Teasdale JD, et al. Prevention of relapse in residual depression by cognitive therapy: a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(9):829-835.

28. Clarke K, Mayo-Wilson E, Kenny J, et al. Can non-pharmacological interventions prevent relapse in adults who have recovered from depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:58-70.

29. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Grandi, S, et al. Prevention of recurrent depression with cognitive behavioral therapy: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(9):816-820.

30. Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, et al. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(10):1872-1876.

31. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Fawcett J, et al. Effect of cognitive therapy with antidepressant medications vs antidepressants alone on the rate of recovery in major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1157-1164.

32. Bockting CL, Smid NH, Koeter MW, et al. Enduring effects of preventive cognitive therapy in adults remitted from recurrent depression: a 10 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:188-194.

33. Paykel ES, Scott J, Cornwall PL, et al. Duration of relapse prevention after cognitive therapy in residual depression: follow-up of controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2005;35(1):59-68.

1. Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851-858.

2. Keller MB. Past, present, and future directions for defining optimal treatment outcome in depression: remission and beyond. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3152-3160.

3. Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265-1273.

4. Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685-716.

5. Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Schulberg HC. Evidence-based models of integrated management of depression in primary care. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28(4):1061-1077.

6. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47-53.

7. Paykel ES, Hollyman JA, Freeling P, et al. Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 1988;14(1):83-95

8. Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265-1273.

9. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

10. Zhang B, Ding X, Lu W, et al. Effect of group cognitive-behavioral therapy on the quality of life and social functioning of patients with mild depression. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):18-27.

11. Matsunaga M, Okamoto Y, Suzuki S et.al. Psychosocial functioning in patients with treatment-resistant depression after group cognitive behavioral therapy. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:22.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(suppl 4):1-26.

13. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-982; discussion 983.

14. Jacobson NS, Hollon SD. Prospects for future comparisons between drugs and psychotherapy: lessons from the CBT-versus-pharmacotherapy exchange. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):104-108.

15. Jarrett RB, Schaffer M, McIntire D, et al. Treatment of atypical depression with cognitive therapy or phenelzine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(5):431-437.

16. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409-416.

17. Amick HR, Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second generation antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapies in initial treatment of major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h6019. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6019.

18. Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T. Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(1):13-20.

19. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Antidepressant medications v. cognitive therapy in people with depression with or without personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):124-129.

20. Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, et al. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1000-1006.

21. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):229-233.

22. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):851-855.

23. Thase ME. Relapse and recurrence of depression: an updated practical approach for prevention. In: Palmer KJ, ed. Drug treatment issues in depression. Auckland, New Zealand: Adis International; 2000:35-52.

24. Evans MD, Hollon, SD, DeRubeis RJ, et al. Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):802-808.

25. Vittengal JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, et al. Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(3):475-488.

26. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):417-422.

27. Paykel ES, Scott J, Teasdale JD, et al. Prevention of relapse in residual depression by cognitive therapy: a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(9):829-835.

28. Clarke K, Mayo-Wilson E, Kenny J, et al. Can non-pharmacological interventions prevent relapse in adults who have recovered from depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:58-70.

29. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Grandi, S, et al. Prevention of recurrent depression with cognitive behavioral therapy: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(9):816-820.

30. Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, et al. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(10):1872-1876.

31. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Fawcett J, et al. Effect of cognitive therapy with antidepressant medications vs antidepressants alone on the rate of recovery in major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1157-1164.

32. Bockting CL, Smid NH, Koeter MW, et al. Enduring effects of preventive cognitive therapy in adults remitted from recurrent depression: a 10 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:188-194.

33. Paykel ES, Scott J, Cornwall PL, et al. Duration of relapse prevention after cognitive therapy in residual depression: follow-up of controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2005;35(1):59-68.