User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Overdose deaths mark another record year, but experts hopeful

, according to newly released figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overdose deaths in 2022 totaled an estimated 109,680 people, which is 2% more than the 107,573 deaths in 2021, according to the figures. But the 2022 total is still a record for the third straight year.

Public health officials are now in a hopeful position. If the 2022 data represents a peak, then the country will see deaths decline toward pre-pandemic levels. If overdose deaths instead have reached a plateau, it means that the United States will sustain the nearly 20% leap that came amid a deadly increase in drug use in 2020 and 2021.

“The fact that it does seem to be flattening out, at least at a national level, is encouraging,” Columbia University epidemiologist Katherine Keyes, PhD, MPH, told The Associated Press. “But these numbers are still extraordinarily high. We shouldn’t suggest the crisis is in any way over.”

The newly released figures from the CDC are considered estimates because some states may still send updated 2022 information later this year.

Although the number of deaths from 2021 to 2022 was stable on a national level, the picture varied more widely at the state level. More than half of U.S. states saw increases, while deaths in 23 states decreased, and just one – Iowa – had the same number of overdose deaths in 2021 and 2022.

The states with the highest counts in 2022 were:

- California: 11,978 deaths

- Florida: 8,032 deaths

- Texas: 5,607 deaths

- Pennsylvania: 5,222 deaths

- Ohio: 5,103 deaths

Synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl and tramadol, account for most drug overdose deaths, according to a December 2022 report from the CDC.

State officials told The AP that they believe the plateau in overdose deaths is in part due to educational campaigns to warn the public about the dangers of drug use, as well as from expanded addiction treatment and increased access to the overdose-reversal medicine naloxone.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to newly released figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overdose deaths in 2022 totaled an estimated 109,680 people, which is 2% more than the 107,573 deaths in 2021, according to the figures. But the 2022 total is still a record for the third straight year.

Public health officials are now in a hopeful position. If the 2022 data represents a peak, then the country will see deaths decline toward pre-pandemic levels. If overdose deaths instead have reached a plateau, it means that the United States will sustain the nearly 20% leap that came amid a deadly increase in drug use in 2020 and 2021.

“The fact that it does seem to be flattening out, at least at a national level, is encouraging,” Columbia University epidemiologist Katherine Keyes, PhD, MPH, told The Associated Press. “But these numbers are still extraordinarily high. We shouldn’t suggest the crisis is in any way over.”

The newly released figures from the CDC are considered estimates because some states may still send updated 2022 information later this year.

Although the number of deaths from 2021 to 2022 was stable on a national level, the picture varied more widely at the state level. More than half of U.S. states saw increases, while deaths in 23 states decreased, and just one – Iowa – had the same number of overdose deaths in 2021 and 2022.

The states with the highest counts in 2022 were:

- California: 11,978 deaths

- Florida: 8,032 deaths

- Texas: 5,607 deaths

- Pennsylvania: 5,222 deaths

- Ohio: 5,103 deaths

Synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl and tramadol, account for most drug overdose deaths, according to a December 2022 report from the CDC.

State officials told The AP that they believe the plateau in overdose deaths is in part due to educational campaigns to warn the public about the dangers of drug use, as well as from expanded addiction treatment and increased access to the overdose-reversal medicine naloxone.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to newly released figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overdose deaths in 2022 totaled an estimated 109,680 people, which is 2% more than the 107,573 deaths in 2021, according to the figures. But the 2022 total is still a record for the third straight year.

Public health officials are now in a hopeful position. If the 2022 data represents a peak, then the country will see deaths decline toward pre-pandemic levels. If overdose deaths instead have reached a plateau, it means that the United States will sustain the nearly 20% leap that came amid a deadly increase in drug use in 2020 and 2021.

“The fact that it does seem to be flattening out, at least at a national level, is encouraging,” Columbia University epidemiologist Katherine Keyes, PhD, MPH, told The Associated Press. “But these numbers are still extraordinarily high. We shouldn’t suggest the crisis is in any way over.”

The newly released figures from the CDC are considered estimates because some states may still send updated 2022 information later this year.

Although the number of deaths from 2021 to 2022 was stable on a national level, the picture varied more widely at the state level. More than half of U.S. states saw increases, while deaths in 23 states decreased, and just one – Iowa – had the same number of overdose deaths in 2021 and 2022.

The states with the highest counts in 2022 were:

- California: 11,978 deaths

- Florida: 8,032 deaths

- Texas: 5,607 deaths

- Pennsylvania: 5,222 deaths

- Ohio: 5,103 deaths

Synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl and tramadol, account for most drug overdose deaths, according to a December 2022 report from the CDC.

State officials told The AP that they believe the plateau in overdose deaths is in part due to educational campaigns to warn the public about the dangers of drug use, as well as from expanded addiction treatment and increased access to the overdose-reversal medicine naloxone.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Choosing our terms: The diagnostic words we use can be harmful

We are living in an era of increasing sensitivity to our diversity and the ways we interact, but also an era of growing resistance to change and accommodation. As clinicians, we hope to be among the sensitive and the progressive, open to improving our views and interactions. And as part of our respect for those we treat, we seek to speak clearly with them about our assessment of what is disrupting their lives and about their options.

Using the right words is crucial in that work. Well-chosen words can be heard and understood. Poorly chosen words can be confusing or off-putting; they may miscommunicate or be offensive. Careful choice of words is also important among colleagues, who may not always mean the same things when using the same words.

In psychiatry, consumer knowledge and access are growing. There are effective standard treatments and promising new ones. But our terminology is often antique and obscure. This is so despite a recognition that some terms we use may communicate poorly and some are deprecating.

A notable example is “schizophrenia.” Originally referring to cognitive phenomena that were not adequately coherent with reality or one another, it has gone through periods of describing most psychosis to particular subsets of psychoses. Debates persist on specific criteria for key symptoms and typical course. Even two clinicians trained in the same site may not agree on the defining criteria, and the public, mostly informed by books, movies, and newspapers, is even more confused, often believing schizophrenia is multiple-personality disorder. In addition, the press and public often associate schizophrenia with violent behavior and uniformly bad outcomes, and for those reasons, a diagnosis is not only frightening but also stigmatizing.1

Many papers have presented the case for retiring “schizophrenia.”2 And practical efforts to rename schizophrenia have been made. These efforts have occurred in countries in which English is not the primary language.3 In Japan, schizophrenia was replaced by “integration disorder.” In Hong Kong, “disorder of thought and perception” was implemented. Korea chose “attunement disorder.” A recent large survey of stakeholders, including clinicians, researchers, and consumers in the United States, explored alternatives in English.4 Terms receiving approval included: “psychosis spectrum syndrome,” “altered perception syndrome,” and “neuro-emotional integration disorder.”

Despite these recommendations, the standard manuals of diagnosis, the ICD and DSM, have maintained the century-old term “schizophrenia” in their most recent editions, released in 2022. Aside from the inertia commonly associated with long-standing practices, it has been noted that many of the alternatives suggested or, in some places, implemented, are complex, somewhat vague, or too inclusive to distinguish different clinical presentations requiring different treatment approaches. They might not be compelling for use or optimal to guide caregiving.

Perhaps more concerning than “schizophrenia” are terms used to describe personality disorders.5 “Personality disorder” itself is problematic, implying a core and possibly unalterable fault in an individual. And among the personality disorders, words for the related group of disorders called “Cluster B” in the DSM raise issues. This includes the terms narcissistic, antisocial, histrionic, and borderline in DSM-5-TR. The first three terms are clearly pejorative. The last is unclear: What is the border between? Originally, it was bordering on psychosis, but as explained in DSM and ICD, borderline disorder is much more closely related to other personality disorders.

Notably, the “Cluster B” disorders run together in families, but men are more likely to be called antisocial and women borderline, even though the overlap in signs and symptoms is profound, suggesting marginally different manifestations of the same condition. The ICD has made changes to address the problems associated with some of these terms. ICD proposes personality “difficulty” to replace personality “disorder”; a modest change but less offensive. And it proposes seeing all, or at least most, personality disorders as being related to one another. Most share features of disturbances in sense-of-self and relationships with others. As descriptors, ICD kept “borderline pattern,” but replaced “antisocial” with “dissocial,” in an effort to be accurate but less demeaning. Other descriptors it proposes are negative affectivity, detachment, disinhibition, and anankastia, the last referring to compulsions.

These are notable advances. Can the field find even better terms to communicate hard to hear information, with words that are less problematic? In search of options, we surveyed clinicians at academic centers about the terms they preferred to avoid and the ones they prefer to use in talking with patients.6 Their practices may be informative.

Briefly summarized, these clinicians preferred not to use “schizophrenia” and very few used “antisocial,” “histrionic,” or “narcissistic.” Most avoided using “borderline” as well. Instead, they recommended discussing specific symptoms and manifestations of illness or dysfunctional behavior and relationships with their patients. They employed terms including “psychosis,” “hallucination,” “delusion,” “thinking disorder,” and “mood disorder.” They explained these terms, as needed, and found that patients understood them.

For Cluster B personality disorders, they spoke of personality traits and styles and specifically about “conduct,” “rule breaking,” “coping,” “self-focus,” “emotionality,” and “reactivity.” Those choices are not perfect, of course. Medical terms are often not standard words used in a conversational way. But the words chosen by these clinicians are generally straightforward and may communicate in a clear and acceptable fashion. It is also notable that the terms match how the clinicians assess and treat their patients, as observed in a separate study of their practices.7 That is, the clinicians advised that they look for and suggest treatments for the specific symptoms they see that most disrupt an individual’s life, such as delusions or mood instability. They are not much guided by diagnoses, like schizophrenia or borderline disorder. That makes the chosen terms not only less confusing or off-putting but also more practical.

Changing terminology in any field is difficult. We are trained to use standard terms. Clearly, however, many clinicians avoid some terms and use alternatives in their work. Asked why, they responded that they did so precisely to communicate more effectively and more respectfully. That is key to their treatment goals. Perhaps others will consider these choices useful in their work. And perhaps both the DSM and the ICD will not only continue to consider but will decide to implement alternatives for problematic terms in the years ahead, as they discuss their next revisions.

Dr. Cohen is director of the Program for Neuropsychiatric Research at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and Robertson-Steele Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

References

1. Lasalvia A et al. Renaming schizophrenia? A survey among psychiatrists, mental health service users and family members in Italy. Schizophr Res. 2021;228:502-9.

2. Gülöksüz S et al. Renaming schizophrenia: 5 x 5. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(3):254-7.

3. Sartorius N et al. Name change for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(2):255-8.

4. Mesholam-Gately RI et al. Are we ready for a name change for schizophrenia? A survey of multiple stakeholders. Schizophr Res. 2021;238:152-60.

5. Mulder R. The evolving nosology of personality disorder and its clinical utility. World Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;20(3):361-2.

6. Cohen BM et al. Diagnostic terms psychiatrists prefer to use for common psychotic and personality disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2022 Sep 5;155:226-31.

7. Cohen BM, et al. Use of DSM-5 diagnoses vs. other clinical information by US academic-affiliated psychiatrists in assessing and treating psychotic disorders. World Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;20(3):447-8.

We are living in an era of increasing sensitivity to our diversity and the ways we interact, but also an era of growing resistance to change and accommodation. As clinicians, we hope to be among the sensitive and the progressive, open to improving our views and interactions. And as part of our respect for those we treat, we seek to speak clearly with them about our assessment of what is disrupting their lives and about their options.

Using the right words is crucial in that work. Well-chosen words can be heard and understood. Poorly chosen words can be confusing or off-putting; they may miscommunicate or be offensive. Careful choice of words is also important among colleagues, who may not always mean the same things when using the same words.

In psychiatry, consumer knowledge and access are growing. There are effective standard treatments and promising new ones. But our terminology is often antique and obscure. This is so despite a recognition that some terms we use may communicate poorly and some are deprecating.

A notable example is “schizophrenia.” Originally referring to cognitive phenomena that were not adequately coherent with reality or one another, it has gone through periods of describing most psychosis to particular subsets of psychoses. Debates persist on specific criteria for key symptoms and typical course. Even two clinicians trained in the same site may not agree on the defining criteria, and the public, mostly informed by books, movies, and newspapers, is even more confused, often believing schizophrenia is multiple-personality disorder. In addition, the press and public often associate schizophrenia with violent behavior and uniformly bad outcomes, and for those reasons, a diagnosis is not only frightening but also stigmatizing.1

Many papers have presented the case for retiring “schizophrenia.”2 And practical efforts to rename schizophrenia have been made. These efforts have occurred in countries in which English is not the primary language.3 In Japan, schizophrenia was replaced by “integration disorder.” In Hong Kong, “disorder of thought and perception” was implemented. Korea chose “attunement disorder.” A recent large survey of stakeholders, including clinicians, researchers, and consumers in the United States, explored alternatives in English.4 Terms receiving approval included: “psychosis spectrum syndrome,” “altered perception syndrome,” and “neuro-emotional integration disorder.”

Despite these recommendations, the standard manuals of diagnosis, the ICD and DSM, have maintained the century-old term “schizophrenia” in their most recent editions, released in 2022. Aside from the inertia commonly associated with long-standing practices, it has been noted that many of the alternatives suggested or, in some places, implemented, are complex, somewhat vague, or too inclusive to distinguish different clinical presentations requiring different treatment approaches. They might not be compelling for use or optimal to guide caregiving.

Perhaps more concerning than “schizophrenia” are terms used to describe personality disorders.5 “Personality disorder” itself is problematic, implying a core and possibly unalterable fault in an individual. And among the personality disorders, words for the related group of disorders called “Cluster B” in the DSM raise issues. This includes the terms narcissistic, antisocial, histrionic, and borderline in DSM-5-TR. The first three terms are clearly pejorative. The last is unclear: What is the border between? Originally, it was bordering on psychosis, but as explained in DSM and ICD, borderline disorder is much more closely related to other personality disorders.

Notably, the “Cluster B” disorders run together in families, but men are more likely to be called antisocial and women borderline, even though the overlap in signs and symptoms is profound, suggesting marginally different manifestations of the same condition. The ICD has made changes to address the problems associated with some of these terms. ICD proposes personality “difficulty” to replace personality “disorder”; a modest change but less offensive. And it proposes seeing all, or at least most, personality disorders as being related to one another. Most share features of disturbances in sense-of-self and relationships with others. As descriptors, ICD kept “borderline pattern,” but replaced “antisocial” with “dissocial,” in an effort to be accurate but less demeaning. Other descriptors it proposes are negative affectivity, detachment, disinhibition, and anankastia, the last referring to compulsions.

These are notable advances. Can the field find even better terms to communicate hard to hear information, with words that are less problematic? In search of options, we surveyed clinicians at academic centers about the terms they preferred to avoid and the ones they prefer to use in talking with patients.6 Their practices may be informative.

Briefly summarized, these clinicians preferred not to use “schizophrenia” and very few used “antisocial,” “histrionic,” or “narcissistic.” Most avoided using “borderline” as well. Instead, they recommended discussing specific symptoms and manifestations of illness or dysfunctional behavior and relationships with their patients. They employed terms including “psychosis,” “hallucination,” “delusion,” “thinking disorder,” and “mood disorder.” They explained these terms, as needed, and found that patients understood them.

For Cluster B personality disorders, they spoke of personality traits and styles and specifically about “conduct,” “rule breaking,” “coping,” “self-focus,” “emotionality,” and “reactivity.” Those choices are not perfect, of course. Medical terms are often not standard words used in a conversational way. But the words chosen by these clinicians are generally straightforward and may communicate in a clear and acceptable fashion. It is also notable that the terms match how the clinicians assess and treat their patients, as observed in a separate study of their practices.7 That is, the clinicians advised that they look for and suggest treatments for the specific symptoms they see that most disrupt an individual’s life, such as delusions or mood instability. They are not much guided by diagnoses, like schizophrenia or borderline disorder. That makes the chosen terms not only less confusing or off-putting but also more practical.

Changing terminology in any field is difficult. We are trained to use standard terms. Clearly, however, many clinicians avoid some terms and use alternatives in their work. Asked why, they responded that they did so precisely to communicate more effectively and more respectfully. That is key to their treatment goals. Perhaps others will consider these choices useful in their work. And perhaps both the DSM and the ICD will not only continue to consider but will decide to implement alternatives for problematic terms in the years ahead, as they discuss their next revisions.

Dr. Cohen is director of the Program for Neuropsychiatric Research at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and Robertson-Steele Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

References

1. Lasalvia A et al. Renaming schizophrenia? A survey among psychiatrists, mental health service users and family members in Italy. Schizophr Res. 2021;228:502-9.

2. Gülöksüz S et al. Renaming schizophrenia: 5 x 5. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(3):254-7.

3. Sartorius N et al. Name change for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(2):255-8.

4. Mesholam-Gately RI et al. Are we ready for a name change for schizophrenia? A survey of multiple stakeholders. Schizophr Res. 2021;238:152-60.

5. Mulder R. The evolving nosology of personality disorder and its clinical utility. World Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;20(3):361-2.

6. Cohen BM et al. Diagnostic terms psychiatrists prefer to use for common psychotic and personality disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2022 Sep 5;155:226-31.

7. Cohen BM, et al. Use of DSM-5 diagnoses vs. other clinical information by US academic-affiliated psychiatrists in assessing and treating psychotic disorders. World Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;20(3):447-8.

We are living in an era of increasing sensitivity to our diversity and the ways we interact, but also an era of growing resistance to change and accommodation. As clinicians, we hope to be among the sensitive and the progressive, open to improving our views and interactions. And as part of our respect for those we treat, we seek to speak clearly with them about our assessment of what is disrupting their lives and about their options.

Using the right words is crucial in that work. Well-chosen words can be heard and understood. Poorly chosen words can be confusing or off-putting; they may miscommunicate or be offensive. Careful choice of words is also important among colleagues, who may not always mean the same things when using the same words.

In psychiatry, consumer knowledge and access are growing. There are effective standard treatments and promising new ones. But our terminology is often antique and obscure. This is so despite a recognition that some terms we use may communicate poorly and some are deprecating.

A notable example is “schizophrenia.” Originally referring to cognitive phenomena that were not adequately coherent with reality or one another, it has gone through periods of describing most psychosis to particular subsets of psychoses. Debates persist on specific criteria for key symptoms and typical course. Even two clinicians trained in the same site may not agree on the defining criteria, and the public, mostly informed by books, movies, and newspapers, is even more confused, often believing schizophrenia is multiple-personality disorder. In addition, the press and public often associate schizophrenia with violent behavior and uniformly bad outcomes, and for those reasons, a diagnosis is not only frightening but also stigmatizing.1

Many papers have presented the case for retiring “schizophrenia.”2 And practical efforts to rename schizophrenia have been made. These efforts have occurred in countries in which English is not the primary language.3 In Japan, schizophrenia was replaced by “integration disorder.” In Hong Kong, “disorder of thought and perception” was implemented. Korea chose “attunement disorder.” A recent large survey of stakeholders, including clinicians, researchers, and consumers in the United States, explored alternatives in English.4 Terms receiving approval included: “psychosis spectrum syndrome,” “altered perception syndrome,” and “neuro-emotional integration disorder.”

Despite these recommendations, the standard manuals of diagnosis, the ICD and DSM, have maintained the century-old term “schizophrenia” in their most recent editions, released in 2022. Aside from the inertia commonly associated with long-standing practices, it has been noted that many of the alternatives suggested or, in some places, implemented, are complex, somewhat vague, or too inclusive to distinguish different clinical presentations requiring different treatment approaches. They might not be compelling for use or optimal to guide caregiving.

Perhaps more concerning than “schizophrenia” are terms used to describe personality disorders.5 “Personality disorder” itself is problematic, implying a core and possibly unalterable fault in an individual. And among the personality disorders, words for the related group of disorders called “Cluster B” in the DSM raise issues. This includes the terms narcissistic, antisocial, histrionic, and borderline in DSM-5-TR. The first three terms are clearly pejorative. The last is unclear: What is the border between? Originally, it was bordering on psychosis, but as explained in DSM and ICD, borderline disorder is much more closely related to other personality disorders.

Notably, the “Cluster B” disorders run together in families, but men are more likely to be called antisocial and women borderline, even though the overlap in signs and symptoms is profound, suggesting marginally different manifestations of the same condition. The ICD has made changes to address the problems associated with some of these terms. ICD proposes personality “difficulty” to replace personality “disorder”; a modest change but less offensive. And it proposes seeing all, or at least most, personality disorders as being related to one another. Most share features of disturbances in sense-of-self and relationships with others. As descriptors, ICD kept “borderline pattern,” but replaced “antisocial” with “dissocial,” in an effort to be accurate but less demeaning. Other descriptors it proposes are negative affectivity, detachment, disinhibition, and anankastia, the last referring to compulsions.

These are notable advances. Can the field find even better terms to communicate hard to hear information, with words that are less problematic? In search of options, we surveyed clinicians at academic centers about the terms they preferred to avoid and the ones they prefer to use in talking with patients.6 Their practices may be informative.

Briefly summarized, these clinicians preferred not to use “schizophrenia” and very few used “antisocial,” “histrionic,” or “narcissistic.” Most avoided using “borderline” as well. Instead, they recommended discussing specific symptoms and manifestations of illness or dysfunctional behavior and relationships with their patients. They employed terms including “psychosis,” “hallucination,” “delusion,” “thinking disorder,” and “mood disorder.” They explained these terms, as needed, and found that patients understood them.

For Cluster B personality disorders, they spoke of personality traits and styles and specifically about “conduct,” “rule breaking,” “coping,” “self-focus,” “emotionality,” and “reactivity.” Those choices are not perfect, of course. Medical terms are often not standard words used in a conversational way. But the words chosen by these clinicians are generally straightforward and may communicate in a clear and acceptable fashion. It is also notable that the terms match how the clinicians assess and treat their patients, as observed in a separate study of their practices.7 That is, the clinicians advised that they look for and suggest treatments for the specific symptoms they see that most disrupt an individual’s life, such as delusions or mood instability. They are not much guided by diagnoses, like schizophrenia or borderline disorder. That makes the chosen terms not only less confusing or off-putting but also more practical.

Changing terminology in any field is difficult. We are trained to use standard terms. Clearly, however, many clinicians avoid some terms and use alternatives in their work. Asked why, they responded that they did so precisely to communicate more effectively and more respectfully. That is key to their treatment goals. Perhaps others will consider these choices useful in their work. And perhaps both the DSM and the ICD will not only continue to consider but will decide to implement alternatives for problematic terms in the years ahead, as they discuss their next revisions.

Dr. Cohen is director of the Program for Neuropsychiatric Research at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and Robertson-Steele Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

References

1. Lasalvia A et al. Renaming schizophrenia? A survey among psychiatrists, mental health service users and family members in Italy. Schizophr Res. 2021;228:502-9.

2. Gülöksüz S et al. Renaming schizophrenia: 5 x 5. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(3):254-7.

3. Sartorius N et al. Name change for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(2):255-8.

4. Mesholam-Gately RI et al. Are we ready for a name change for schizophrenia? A survey of multiple stakeholders. Schizophr Res. 2021;238:152-60.

5. Mulder R. The evolving nosology of personality disorder and its clinical utility. World Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;20(3):361-2.

6. Cohen BM et al. Diagnostic terms psychiatrists prefer to use for common psychotic and personality disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2022 Sep 5;155:226-31.

7. Cohen BM, et al. Use of DSM-5 diagnoses vs. other clinical information by US academic-affiliated psychiatrists in assessing and treating psychotic disorders. World Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;20(3):447-8.

Internet use a modifiable dementia risk factor in older adults?

Investigators followed more than 18,000 older individuals and found that regular Internet use was associated with about a 50% reduction in dementia risk, compared with their counterparts who did not use the Internet regularly.

They also found that longer duration of regular Internet use was associated with a reduced risk of dementia, although excessive daily Internet usage appeared to adversely affect dementia risk.

“Online engagement can develop and maintain cognitive reserve – resiliency against physiological damage to the brain – and increased cognitive reserve can, in turn, compensate for brain aging and reduce the risk of dementia,” study investigator Gawon Cho, a doctoral candidate at New York University School of Global Public Health, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Unexamined benefits

Prior research has shown that older adult Internet users have “better overall cognitive performance, verbal reasoning, and memory,” compared with nonusers, the authors note.

However, because this body of research consists of cross-sectional analyses and longitudinal studies with brief follow-up periods, the long-term cognitive benefits of Internet usage remain “unexamined.”

In addition, despite “extensive evidence of a disproportionately high burden of dementia in people of color, individuals without higher education, and adults who experienced other socioeconomic hardships, little is known about whether the Internet has exacerbated population-level disparities in cognitive health,” the investigators add.

Another question concerns whether excessive Internet usage may actually be detrimental to neurocognitive outcomes. However, “existing evidence on the adverse effects of Internet usage is concentrated in younger populations whose brains are still undergoing maturation.”

Ms. Cho said the motivation for the study was the lack of longitudinal studies on this topic, especially those with sufficient follow-up periods. In addition, she said, there is insufficient evidence about how changes in Internet usage in older age are associated with prospective dementia risk.

For the study, investigators turned to participants in the Health and Retirement Study, an ongoing longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S.-based older adults (aged ≥ 50 years).

All participants (n = 18,154; 47.36% male; median age, 55.17 years) were dementia-free, community-dwelling older adults who completed a 2002 baseline cognitive assessment and were asked about Internet usage every 2 years thereafter.

Participants were followed from 2002 to 2018 for a maximum of 17.1 years (median, 7.9 years), which is the longest follow-up period to date. Of the total sample, 64.76% were regular Internet users.

The study’s primary outcome was incident dementia, based on performance on the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M), which was administered every 2 years.

The exposure examined in the study was cumulative Internet usage in late adulthood, defined as “the number of biennial waves where participants used the Internet regularly during the first three waves.”

In addition, participants were asked how many hours they spent using the Internet during the past week for activities other than viewing television shows or movies.

The researchers also investigated whether the link between Internet usage and dementia risk varied by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generational cohort.

Covariates included baseline TICS-M score, health, age, household income, marital status, and region of residence.

U-shaped curve

More than half of the sample (52.96%) showed no changes in Internet use from baseline during the study period, while one-fifth (20.54%) did show changes in use.

Investigators found a robust link between Internet usage and lower dementia risk (cause-specific hazard ratio, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46-0.71]) – a finding that remained even after adjusting for self-selection into baseline usage (csHR, 0.54 [0.41-0.72]) and signs of cognitive decline at baseline (csHR, 0.62 [0.46-0.85]).

Each additional wave of regular Internet usage was associated with a 21% decrease in the risk of dementia (95% CI, 13%-29%), wherein additional regular periods were associated with reduced dementia risk (csHR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]).

“The difference in risk between regular and nonregular users did not vary by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generation,” the investigators note.

A U-shaped association was found between daily hours of online engagement, wherein the lowest risk was observed in those with 0.1-2 hours of usage (compared with 0 hours of usage). The risk increased in a “monotonic fashion” after 2 hours, with 6.1-8 hours of usage showing the highest risk.

This finding was not considered statistically significant, but the “consistent U-shaped trend offers a preliminary suggestion that excessive online engagement may have adverse cognitive effects on older adults,” the investigators note.

“Among older adults, regular Internet users may experience a lower risk of dementia compared to nonregular users, and longer periods of regular Internet usage in late adulthood may help reduce the risks of subsequent dementia incidence,” said Ms. Cho. “Nonetheless, using the Internet excessively daily may negatively affect the risk of dementia in older adults.”

Bidirectional relationship?

Commenting for this article, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that some risk factors for Alzheimer’s or other dementias can’t be changed, while others are modifiable, “either at a personal or a population level.”

She called the current research “important” because it “identifies a potentially modifiable factor that may influence dementia risk.”

However, cautioned Dr. Sexton, who was not involved with the study, the findings cannot establish cause and effect. In fact, the relationship may be bidirectional.

“It may be that regular Internet usage is associated with increased cognitive stimulation, and in turn reduced risk of dementia; or it may be that individuals with lower risk of dementia are more likely to engage in regular Internet usage,” she said. Thus, “interventional studies are able to shed more light on causation.”

The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and is conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Ms. Cho, her coauthors, and Dr. Sexton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators followed more than 18,000 older individuals and found that regular Internet use was associated with about a 50% reduction in dementia risk, compared with their counterparts who did not use the Internet regularly.

They also found that longer duration of regular Internet use was associated with a reduced risk of dementia, although excessive daily Internet usage appeared to adversely affect dementia risk.

“Online engagement can develop and maintain cognitive reserve – resiliency against physiological damage to the brain – and increased cognitive reserve can, in turn, compensate for brain aging and reduce the risk of dementia,” study investigator Gawon Cho, a doctoral candidate at New York University School of Global Public Health, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Unexamined benefits

Prior research has shown that older adult Internet users have “better overall cognitive performance, verbal reasoning, and memory,” compared with nonusers, the authors note.

However, because this body of research consists of cross-sectional analyses and longitudinal studies with brief follow-up periods, the long-term cognitive benefits of Internet usage remain “unexamined.”

In addition, despite “extensive evidence of a disproportionately high burden of dementia in people of color, individuals without higher education, and adults who experienced other socioeconomic hardships, little is known about whether the Internet has exacerbated population-level disparities in cognitive health,” the investigators add.

Another question concerns whether excessive Internet usage may actually be detrimental to neurocognitive outcomes. However, “existing evidence on the adverse effects of Internet usage is concentrated in younger populations whose brains are still undergoing maturation.”

Ms. Cho said the motivation for the study was the lack of longitudinal studies on this topic, especially those with sufficient follow-up periods. In addition, she said, there is insufficient evidence about how changes in Internet usage in older age are associated with prospective dementia risk.

For the study, investigators turned to participants in the Health and Retirement Study, an ongoing longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S.-based older adults (aged ≥ 50 years).

All participants (n = 18,154; 47.36% male; median age, 55.17 years) were dementia-free, community-dwelling older adults who completed a 2002 baseline cognitive assessment and were asked about Internet usage every 2 years thereafter.

Participants were followed from 2002 to 2018 for a maximum of 17.1 years (median, 7.9 years), which is the longest follow-up period to date. Of the total sample, 64.76% were regular Internet users.

The study’s primary outcome was incident dementia, based on performance on the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M), which was administered every 2 years.

The exposure examined in the study was cumulative Internet usage in late adulthood, defined as “the number of biennial waves where participants used the Internet regularly during the first three waves.”

In addition, participants were asked how many hours they spent using the Internet during the past week for activities other than viewing television shows or movies.

The researchers also investigated whether the link between Internet usage and dementia risk varied by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generational cohort.

Covariates included baseline TICS-M score, health, age, household income, marital status, and region of residence.

U-shaped curve

More than half of the sample (52.96%) showed no changes in Internet use from baseline during the study period, while one-fifth (20.54%) did show changes in use.

Investigators found a robust link between Internet usage and lower dementia risk (cause-specific hazard ratio, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46-0.71]) – a finding that remained even after adjusting for self-selection into baseline usage (csHR, 0.54 [0.41-0.72]) and signs of cognitive decline at baseline (csHR, 0.62 [0.46-0.85]).

Each additional wave of regular Internet usage was associated with a 21% decrease in the risk of dementia (95% CI, 13%-29%), wherein additional regular periods were associated with reduced dementia risk (csHR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]).

“The difference in risk between regular and nonregular users did not vary by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generation,” the investigators note.

A U-shaped association was found between daily hours of online engagement, wherein the lowest risk was observed in those with 0.1-2 hours of usage (compared with 0 hours of usage). The risk increased in a “monotonic fashion” after 2 hours, with 6.1-8 hours of usage showing the highest risk.

This finding was not considered statistically significant, but the “consistent U-shaped trend offers a preliminary suggestion that excessive online engagement may have adverse cognitive effects on older adults,” the investigators note.

“Among older adults, regular Internet users may experience a lower risk of dementia compared to nonregular users, and longer periods of regular Internet usage in late adulthood may help reduce the risks of subsequent dementia incidence,” said Ms. Cho. “Nonetheless, using the Internet excessively daily may negatively affect the risk of dementia in older adults.”

Bidirectional relationship?

Commenting for this article, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that some risk factors for Alzheimer’s or other dementias can’t be changed, while others are modifiable, “either at a personal or a population level.”

She called the current research “important” because it “identifies a potentially modifiable factor that may influence dementia risk.”

However, cautioned Dr. Sexton, who was not involved with the study, the findings cannot establish cause and effect. In fact, the relationship may be bidirectional.

“It may be that regular Internet usage is associated with increased cognitive stimulation, and in turn reduced risk of dementia; or it may be that individuals with lower risk of dementia are more likely to engage in regular Internet usage,” she said. Thus, “interventional studies are able to shed more light on causation.”

The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and is conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Ms. Cho, her coauthors, and Dr. Sexton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators followed more than 18,000 older individuals and found that regular Internet use was associated with about a 50% reduction in dementia risk, compared with their counterparts who did not use the Internet regularly.

They also found that longer duration of regular Internet use was associated with a reduced risk of dementia, although excessive daily Internet usage appeared to adversely affect dementia risk.

“Online engagement can develop and maintain cognitive reserve – resiliency against physiological damage to the brain – and increased cognitive reserve can, in turn, compensate for brain aging and reduce the risk of dementia,” study investigator Gawon Cho, a doctoral candidate at New York University School of Global Public Health, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Unexamined benefits

Prior research has shown that older adult Internet users have “better overall cognitive performance, verbal reasoning, and memory,” compared with nonusers, the authors note.

However, because this body of research consists of cross-sectional analyses and longitudinal studies with brief follow-up periods, the long-term cognitive benefits of Internet usage remain “unexamined.”

In addition, despite “extensive evidence of a disproportionately high burden of dementia in people of color, individuals without higher education, and adults who experienced other socioeconomic hardships, little is known about whether the Internet has exacerbated population-level disparities in cognitive health,” the investigators add.

Another question concerns whether excessive Internet usage may actually be detrimental to neurocognitive outcomes. However, “existing evidence on the adverse effects of Internet usage is concentrated in younger populations whose brains are still undergoing maturation.”

Ms. Cho said the motivation for the study was the lack of longitudinal studies on this topic, especially those with sufficient follow-up periods. In addition, she said, there is insufficient evidence about how changes in Internet usage in older age are associated with prospective dementia risk.

For the study, investigators turned to participants in the Health and Retirement Study, an ongoing longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S.-based older adults (aged ≥ 50 years).

All participants (n = 18,154; 47.36% male; median age, 55.17 years) were dementia-free, community-dwelling older adults who completed a 2002 baseline cognitive assessment and were asked about Internet usage every 2 years thereafter.

Participants were followed from 2002 to 2018 for a maximum of 17.1 years (median, 7.9 years), which is the longest follow-up period to date. Of the total sample, 64.76% were regular Internet users.

The study’s primary outcome was incident dementia, based on performance on the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M), which was administered every 2 years.

The exposure examined in the study was cumulative Internet usage in late adulthood, defined as “the number of biennial waves where participants used the Internet regularly during the first three waves.”

In addition, participants were asked how many hours they spent using the Internet during the past week for activities other than viewing television shows or movies.

The researchers also investigated whether the link between Internet usage and dementia risk varied by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generational cohort.

Covariates included baseline TICS-M score, health, age, household income, marital status, and region of residence.

U-shaped curve

More than half of the sample (52.96%) showed no changes in Internet use from baseline during the study period, while one-fifth (20.54%) did show changes in use.

Investigators found a robust link between Internet usage and lower dementia risk (cause-specific hazard ratio, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46-0.71]) – a finding that remained even after adjusting for self-selection into baseline usage (csHR, 0.54 [0.41-0.72]) and signs of cognitive decline at baseline (csHR, 0.62 [0.46-0.85]).

Each additional wave of regular Internet usage was associated with a 21% decrease in the risk of dementia (95% CI, 13%-29%), wherein additional regular periods were associated with reduced dementia risk (csHR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]).

“The difference in risk between regular and nonregular users did not vary by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generation,” the investigators note.

A U-shaped association was found between daily hours of online engagement, wherein the lowest risk was observed in those with 0.1-2 hours of usage (compared with 0 hours of usage). The risk increased in a “monotonic fashion” after 2 hours, with 6.1-8 hours of usage showing the highest risk.

This finding was not considered statistically significant, but the “consistent U-shaped trend offers a preliminary suggestion that excessive online engagement may have adverse cognitive effects on older adults,” the investigators note.

“Among older adults, regular Internet users may experience a lower risk of dementia compared to nonregular users, and longer periods of regular Internet usage in late adulthood may help reduce the risks of subsequent dementia incidence,” said Ms. Cho. “Nonetheless, using the Internet excessively daily may negatively affect the risk of dementia in older adults.”

Bidirectional relationship?

Commenting for this article, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that some risk factors for Alzheimer’s or other dementias can’t be changed, while others are modifiable, “either at a personal or a population level.”

She called the current research “important” because it “identifies a potentially modifiable factor that may influence dementia risk.”

However, cautioned Dr. Sexton, who was not involved with the study, the findings cannot establish cause and effect. In fact, the relationship may be bidirectional.

“It may be that regular Internet usage is associated with increased cognitive stimulation, and in turn reduced risk of dementia; or it may be that individuals with lower risk of dementia are more likely to engage in regular Internet usage,” she said. Thus, “interventional studies are able to shed more light on causation.”

The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and is conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Ms. Cho, her coauthors, and Dr. Sexton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN GERIATRICS SOCIETY

Will a mindfulness approach to depression boost recovery rates, reduce costs?

Self-help mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT-SH) produced better outcomes for participants with depression and was more cost-effective than CBT-SH.

Practitioner-supported self-help therapy regimens are growing in popularity as a way to expand access to mental health services and to address the shortage of mental health professionals.

Generally, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy aims to increase awareness of the depression maintenance cycle while fostering a nonjudgmental attitude toward present-moment experiences, the investigators note.

In contrast, CBT aims to challenge negative and unrealistic thought patterns that may perpetuate depression, replacing them with more realistic and objective thoughts.

“Practitioner-supported MBCT-SH should be routinely offered as an intervention for mild to moderate depression alongside practitioner-supported CBT-SH,” the investigators note.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Better recovery rates?

CBT-SH traditionally had been associated with high attrition rates, and alternative forms of self-help therapy are becoming increasingly necessary to fill this treatment gap, the researchers note. To compare the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of both treatment types, the researchers recruited 410 participants with mild to moderate depression at 10 sites in the United Kingdom. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either MBCT-SH or CBT-SH between November 2017 and January 2020. A total of 204 participants received MBCT-SH, and 206 received CBT-SH.

All participants were given specific self-help workbooks, depending on the study group to which they were assigned. Those who received MBCT-SH used “The Mindful Way Workbook: An 8-Week Program to Free Yourself From Depression and Emotional Distress,” while those who received CBT-SH used “Overcoming Depression and Low Mood: A Five Areas Approach, 3rd Edition.”

Investigators asked all participants to guide themselves through six 30- to 45-minute sessions, using the information in the workbooks. Trained psychological well-being practitioners supported participants as they moved through the workbooks during the six sessions.

Participants were assessed at baseline with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised at 16 weeks and 24 weeks.

At 16 weeks post randomization, results showed that practitioner-supported MBCT-SH led to significantly greater reductions in depression symptom severity, compared with practitioner-supported CBT-SH (mean [standard deviation] PHQ-9 score, 7.2 [4.8] points vs. 8.6 [5.5] points; between-group difference, –1.5 points; 95% confidence interval, –2.6 to –0.4; P = .009).

Results also showed that on average, the CBT-SH intervention cost $631 more per participant than the MBCT-SH intervention over the 42-week follow-up.

The investigators explain that “a substantial proportion of this additional cost was accounted for by additional face-to-face individual psychological therapy accessed by CBT-SH participants outside of the study intervention.

“In conclusion, this study found that a novel intervention, practitioner-supported MBCT-SH, was clinically superior in targeting depressive symptom severity at postintervention and cost-effective, compared with the criterion standard of practitioner-supported CBT-SH for adults experiencing mild to moderate depression,” the investigators write.

“If study findings are translated into routine practice, this would see many more people recovering from depression while costing health services less money,” they add.

Clinically meaningful?

Commenting on the study for this article, Lauren Bylsma, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, cast doubt on the ability of such a short trial to determine meaningful change.

She said that the extra costs incurred by participants in the CBT-SH arm of the study are likely, since it is “difficult to do CBT alone – you need an objective person to guide you as you practice.”

Dr. Bylsma noted that ultimately, more real-world studies of therapy are needed, given the great need for mental health.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research. The original article contains a full list of the authors’ relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Self-help mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT-SH) produced better outcomes for participants with depression and was more cost-effective than CBT-SH.

Practitioner-supported self-help therapy regimens are growing in popularity as a way to expand access to mental health services and to address the shortage of mental health professionals.

Generally, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy aims to increase awareness of the depression maintenance cycle while fostering a nonjudgmental attitude toward present-moment experiences, the investigators note.

In contrast, CBT aims to challenge negative and unrealistic thought patterns that may perpetuate depression, replacing them with more realistic and objective thoughts.

“Practitioner-supported MBCT-SH should be routinely offered as an intervention for mild to moderate depression alongside practitioner-supported CBT-SH,” the investigators note.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Better recovery rates?

CBT-SH traditionally had been associated with high attrition rates, and alternative forms of self-help therapy are becoming increasingly necessary to fill this treatment gap, the researchers note. To compare the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of both treatment types, the researchers recruited 410 participants with mild to moderate depression at 10 sites in the United Kingdom. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either MBCT-SH or CBT-SH between November 2017 and January 2020. A total of 204 participants received MBCT-SH, and 206 received CBT-SH.

All participants were given specific self-help workbooks, depending on the study group to which they were assigned. Those who received MBCT-SH used “The Mindful Way Workbook: An 8-Week Program to Free Yourself From Depression and Emotional Distress,” while those who received CBT-SH used “Overcoming Depression and Low Mood: A Five Areas Approach, 3rd Edition.”

Investigators asked all participants to guide themselves through six 30- to 45-minute sessions, using the information in the workbooks. Trained psychological well-being practitioners supported participants as they moved through the workbooks during the six sessions.

Participants were assessed at baseline with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised at 16 weeks and 24 weeks.

At 16 weeks post randomization, results showed that practitioner-supported MBCT-SH led to significantly greater reductions in depression symptom severity, compared with practitioner-supported CBT-SH (mean [standard deviation] PHQ-9 score, 7.2 [4.8] points vs. 8.6 [5.5] points; between-group difference, –1.5 points; 95% confidence interval, –2.6 to –0.4; P = .009).

Results also showed that on average, the CBT-SH intervention cost $631 more per participant than the MBCT-SH intervention over the 42-week follow-up.

The investigators explain that “a substantial proportion of this additional cost was accounted for by additional face-to-face individual psychological therapy accessed by CBT-SH participants outside of the study intervention.

“In conclusion, this study found that a novel intervention, practitioner-supported MBCT-SH, was clinically superior in targeting depressive symptom severity at postintervention and cost-effective, compared with the criterion standard of practitioner-supported CBT-SH for adults experiencing mild to moderate depression,” the investigators write.

“If study findings are translated into routine practice, this would see many more people recovering from depression while costing health services less money,” they add.

Clinically meaningful?

Commenting on the study for this article, Lauren Bylsma, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, cast doubt on the ability of such a short trial to determine meaningful change.

She said that the extra costs incurred by participants in the CBT-SH arm of the study are likely, since it is “difficult to do CBT alone – you need an objective person to guide you as you practice.”

Dr. Bylsma noted that ultimately, more real-world studies of therapy are needed, given the great need for mental health.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research. The original article contains a full list of the authors’ relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Self-help mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT-SH) produced better outcomes for participants with depression and was more cost-effective than CBT-SH.

Practitioner-supported self-help therapy regimens are growing in popularity as a way to expand access to mental health services and to address the shortage of mental health professionals.

Generally, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy aims to increase awareness of the depression maintenance cycle while fostering a nonjudgmental attitude toward present-moment experiences, the investigators note.

In contrast, CBT aims to challenge negative and unrealistic thought patterns that may perpetuate depression, replacing them with more realistic and objective thoughts.

“Practitioner-supported MBCT-SH should be routinely offered as an intervention for mild to moderate depression alongside practitioner-supported CBT-SH,” the investigators note.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Better recovery rates?

CBT-SH traditionally had been associated with high attrition rates, and alternative forms of self-help therapy are becoming increasingly necessary to fill this treatment gap, the researchers note. To compare the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of both treatment types, the researchers recruited 410 participants with mild to moderate depression at 10 sites in the United Kingdom. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either MBCT-SH or CBT-SH between November 2017 and January 2020. A total of 204 participants received MBCT-SH, and 206 received CBT-SH.

All participants were given specific self-help workbooks, depending on the study group to which they were assigned. Those who received MBCT-SH used “The Mindful Way Workbook: An 8-Week Program to Free Yourself From Depression and Emotional Distress,” while those who received CBT-SH used “Overcoming Depression and Low Mood: A Five Areas Approach, 3rd Edition.”

Investigators asked all participants to guide themselves through six 30- to 45-minute sessions, using the information in the workbooks. Trained psychological well-being practitioners supported participants as they moved through the workbooks during the six sessions.

Participants were assessed at baseline with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised at 16 weeks and 24 weeks.

At 16 weeks post randomization, results showed that practitioner-supported MBCT-SH led to significantly greater reductions in depression symptom severity, compared with practitioner-supported CBT-SH (mean [standard deviation] PHQ-9 score, 7.2 [4.8] points vs. 8.6 [5.5] points; between-group difference, –1.5 points; 95% confidence interval, –2.6 to –0.4; P = .009).

Results also showed that on average, the CBT-SH intervention cost $631 more per participant than the MBCT-SH intervention over the 42-week follow-up.

The investigators explain that “a substantial proportion of this additional cost was accounted for by additional face-to-face individual psychological therapy accessed by CBT-SH participants outside of the study intervention.

“In conclusion, this study found that a novel intervention, practitioner-supported MBCT-SH, was clinically superior in targeting depressive symptom severity at postintervention and cost-effective, compared with the criterion standard of practitioner-supported CBT-SH for adults experiencing mild to moderate depression,” the investigators write.

“If study findings are translated into routine practice, this would see many more people recovering from depression while costing health services less money,” they add.

Clinically meaningful?

Commenting on the study for this article, Lauren Bylsma, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, cast doubt on the ability of such a short trial to determine meaningful change.

She said that the extra costs incurred by participants in the CBT-SH arm of the study are likely, since it is “difficult to do CBT alone – you need an objective person to guide you as you practice.”

Dr. Bylsma noted that ultimately, more real-world studies of therapy are needed, given the great need for mental health.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research. The original article contains a full list of the authors’ relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

U.S. adults report depression at record rates: Survey

In a survey, 29% of adults said they had been diagnosed with depression during their lifetime, and 18% said they currently have depression or are being treated for it. Those rates are up from the baseline 2015 rates of 20% of people ever having depression and 11% of people with a current diagnosis.

Depression had been steadily rising before the pandemic, and the Gallup analysts wrote that “social isolation, loneliness, fear of infection, psychological exhaustion (particularly among frontline responders such as health care workers), elevated substance abuse, and disruptions in mental health services have all likely played a role” in the increase.

“The fact that Americans are more depressed and struggling after this time of incredible stress and isolation is perhaps not surprising,” American Psychiatric Association president Rebecca Brendel, MD, told CNN. “There are lingering effects on our health, especially our mental health, from the past 3 years that disrupted everything we knew.”

The new estimates are based on online survey responses collected in February from 5,167 adults in the United States who answered the questions:

- Has a doctor or nurse ever told you that you have depression?

- Do you currently have or are you currently being treated for depression?

Depression, which is also called major depressive disorder, is a treatable illness that negatively affects how someone feels, thinks, and acts. The symptoms can be both emotional (such as sadness or loss of interest in activities) and physical (such as fatigue or slowed movements or speech).

The latest study found that depression rates increased the most among women, young adults, Black people, and Hispanic people. For the first time, more Black and Hispanic people than White people reported ever being diagnosed with depression. The lifetime depression rate among Black people was 34%, compared with 31% for Hispanic people and 29% for White people.

The rate of lifetime depression among women jumped 10 percentage points in the past 5 years, to 37%, in February, the survey results showed. About 1 in 4 women said they currently had depression or were being treated for it, up 6 percentage points compared with 5 years ago.

When responses were analyzed by age, those 18-44 years old were the most likely to report ever being diagnosed with depression or currently having the illness. About one-third of younger adults have ever been diagnosed, and more than 1 in 5 said they currently have depression.

Dr. Brendel said awareness and reduced stigma could be adding to the rising rates of depression.

“We’re making it easier to talk about mental health and looking at it as part of our overall wellness, just like physical health,” she said. “People are aware of depression, and people are seeking help for it.”

If you or someone you know needs help, dial 988 for support from the national Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. It’s free, confidential, and available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. You can also visit 988lifeline.org and choose the chat feature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a survey, 29% of adults said they had been diagnosed with depression during their lifetime, and 18% said they currently have depression or are being treated for it. Those rates are up from the baseline 2015 rates of 20% of people ever having depression and 11% of people with a current diagnosis.

Depression had been steadily rising before the pandemic, and the Gallup analysts wrote that “social isolation, loneliness, fear of infection, psychological exhaustion (particularly among frontline responders such as health care workers), elevated substance abuse, and disruptions in mental health services have all likely played a role” in the increase.

“The fact that Americans are more depressed and struggling after this time of incredible stress and isolation is perhaps not surprising,” American Psychiatric Association president Rebecca Brendel, MD, told CNN. “There are lingering effects on our health, especially our mental health, from the past 3 years that disrupted everything we knew.”

The new estimates are based on online survey responses collected in February from 5,167 adults in the United States who answered the questions:

- Has a doctor or nurse ever told you that you have depression?

- Do you currently have or are you currently being treated for depression?

Depression, which is also called major depressive disorder, is a treatable illness that negatively affects how someone feels, thinks, and acts. The symptoms can be both emotional (such as sadness or loss of interest in activities) and physical (such as fatigue or slowed movements or speech).

The latest study found that depression rates increased the most among women, young adults, Black people, and Hispanic people. For the first time, more Black and Hispanic people than White people reported ever being diagnosed with depression. The lifetime depression rate among Black people was 34%, compared with 31% for Hispanic people and 29% for White people.

The rate of lifetime depression among women jumped 10 percentage points in the past 5 years, to 37%, in February, the survey results showed. About 1 in 4 women said they currently had depression or were being treated for it, up 6 percentage points compared with 5 years ago.

When responses were analyzed by age, those 18-44 years old were the most likely to report ever being diagnosed with depression or currently having the illness. About one-third of younger adults have ever been diagnosed, and more than 1 in 5 said they currently have depression.

Dr. Brendel said awareness and reduced stigma could be adding to the rising rates of depression.

“We’re making it easier to talk about mental health and looking at it as part of our overall wellness, just like physical health,” she said. “People are aware of depression, and people are seeking help for it.”

If you or someone you know needs help, dial 988 for support from the national Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. It’s free, confidential, and available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. You can also visit 988lifeline.org and choose the chat feature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a survey, 29% of adults said they had been diagnosed with depression during their lifetime, and 18% said they currently have depression or are being treated for it. Those rates are up from the baseline 2015 rates of 20% of people ever having depression and 11% of people with a current diagnosis.

Depression had been steadily rising before the pandemic, and the Gallup analysts wrote that “social isolation, loneliness, fear of infection, psychological exhaustion (particularly among frontline responders such as health care workers), elevated substance abuse, and disruptions in mental health services have all likely played a role” in the increase.

“The fact that Americans are more depressed and struggling after this time of incredible stress and isolation is perhaps not surprising,” American Psychiatric Association president Rebecca Brendel, MD, told CNN. “There are lingering effects on our health, especially our mental health, from the past 3 years that disrupted everything we knew.”

The new estimates are based on online survey responses collected in February from 5,167 adults in the United States who answered the questions:

- Has a doctor or nurse ever told you that you have depression?

- Do you currently have or are you currently being treated for depression?

Depression, which is also called major depressive disorder, is a treatable illness that negatively affects how someone feels, thinks, and acts. The symptoms can be both emotional (such as sadness or loss of interest in activities) and physical (such as fatigue or slowed movements or speech).

The latest study found that depression rates increased the most among women, young adults, Black people, and Hispanic people. For the first time, more Black and Hispanic people than White people reported ever being diagnosed with depression. The lifetime depression rate among Black people was 34%, compared with 31% for Hispanic people and 29% for White people.

The rate of lifetime depression among women jumped 10 percentage points in the past 5 years, to 37%, in February, the survey results showed. About 1 in 4 women said they currently had depression or were being treated for it, up 6 percentage points compared with 5 years ago.

When responses were analyzed by age, those 18-44 years old were the most likely to report ever being diagnosed with depression or currently having the illness. About one-third of younger adults have ever been diagnosed, and more than 1 in 5 said they currently have depression.

Dr. Brendel said awareness and reduced stigma could be adding to the rising rates of depression.

“We’re making it easier to talk about mental health and looking at it as part of our overall wellness, just like physical health,” she said. “People are aware of depression, and people are seeking help for it.”

If you or someone you know needs help, dial 988 for support from the national Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. It’s free, confidential, and available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. You can also visit 988lifeline.org and choose the chat feature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The antimicrobial peptide that even Pharma can love

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

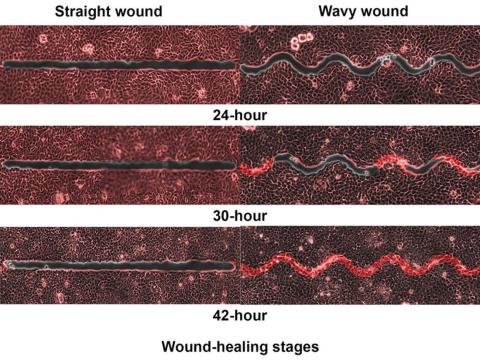

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.