User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Top U.S. hospitals for psychiatric care ranked

McLean Hospital claimed the top spot in the 2022-2023 ranking as well.

Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston holds the No. 2 spot in the 2023-2024 U.S. News ranking for best psychiatry hospitals, up from No. 3 in 2022-2023.

New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell sits at No. 3 in 2023-2024, up from No. 4 in 2022-2023, while Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore is ranked No. 4, down from No. 2.

Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at the University of California, Los Angeles, is ranked No. 5 in 2023-2024 (up from No. 6 in 2022-2023), while UCSF Health–UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco, dropped to No. 6 in 2023-2024 (from No. 5 in 2022-2023).

No. 7 in 2023-2024 is Menninger Clinic, Houston, which held the No. 10 spot in 2022-2023.

According to U.S. News, the psychiatry rating is based on the expert opinion of surveyed psychiatrists. The seven ranked hospitals in psychiatry or psychiatric care were recommended by at least 5% of the psychiatric specialists responding to the magazine’s surveys in 2021, 2022, and 2023 as a facility where they would refer their patients.

“Consumers want useful resources to help them assess which hospital can best meet their specific care needs,” Ben Harder, chief of health analysis and managing editor at U.S. News, said in a statement.

“The 2023-2024 Best Hospitals rankings offer patients and the physicians with whom they consult a data-driven source for comparing performance in outcomes, patient satisfaction, and other metrics that matter to them,” Mr. Harder said.

Honor roll

This year, as in prior years, U.S. News also recognized “honor roll” hospitals that have excelled across multiple areas of care. However, in 2023-2024, for the first time, there is no ordinal ranking of hospitals making the honor roll. Instead, they are listed in alphabetical order.

In a letter to hospital leaders, U.S. News explained that the major change in format came after months of deliberation, feedback from health care organizations and professionals, and an analysis of how consumers navigate the magazine’s website.

Ordinal ranking of hospitals that make the honor roll “obscures the fact that all of the Honor Roll hospitals have attained the highest standard of care in the nation,” the letter reads.

With the new format, honor roll hospitals are listed in alphabetical order. In 2023-2024 there are 22.

2023-2024 Honor Roll Hospitals

- Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- Cleveland Clinic

- Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Medicine, Philadelphia

- Houston Methodist Hospital

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell

- North Shore University Hospital at Northwell Health, Manhasset, N.Y.

- Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

- NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

- Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

- Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital

- UC San Diego Health–La Jolla and Hillcrest Hospitals

- UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

- UCSF Health–UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

- University of Michigan Health–Ann Arbor

- UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas

- Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

According to U.S. News, to keep pace with consumers’ needs and the ever-evolving landscape of health care, “several refinements” are reflected in the latest best hospitals rankings.

These include the introduction of outpatient outcomes in key specialty rankings and surgical ratings, the expanded inclusion of other outpatient data, an increased weight on objective quality measures, and a reduced weight on expert opinion.

In addition, hospital profiles on USNews.com feature refined health equity measures, including a new measure of racial disparities in outcomes.

The full report for best hospitals, best specialty hospitals, and methodology is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

McLean Hospital claimed the top spot in the 2022-2023 ranking as well.

Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston holds the No. 2 spot in the 2023-2024 U.S. News ranking for best psychiatry hospitals, up from No. 3 in 2022-2023.

New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell sits at No. 3 in 2023-2024, up from No. 4 in 2022-2023, while Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore is ranked No. 4, down from No. 2.

Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at the University of California, Los Angeles, is ranked No. 5 in 2023-2024 (up from No. 6 in 2022-2023), while UCSF Health–UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco, dropped to No. 6 in 2023-2024 (from No. 5 in 2022-2023).

No. 7 in 2023-2024 is Menninger Clinic, Houston, which held the No. 10 spot in 2022-2023.

According to U.S. News, the psychiatry rating is based on the expert opinion of surveyed psychiatrists. The seven ranked hospitals in psychiatry or psychiatric care were recommended by at least 5% of the psychiatric specialists responding to the magazine’s surveys in 2021, 2022, and 2023 as a facility where they would refer their patients.

“Consumers want useful resources to help them assess which hospital can best meet their specific care needs,” Ben Harder, chief of health analysis and managing editor at U.S. News, said in a statement.

“The 2023-2024 Best Hospitals rankings offer patients and the physicians with whom they consult a data-driven source for comparing performance in outcomes, patient satisfaction, and other metrics that matter to them,” Mr. Harder said.

Honor roll

This year, as in prior years, U.S. News also recognized “honor roll” hospitals that have excelled across multiple areas of care. However, in 2023-2024, for the first time, there is no ordinal ranking of hospitals making the honor roll. Instead, they are listed in alphabetical order.

In a letter to hospital leaders, U.S. News explained that the major change in format came after months of deliberation, feedback from health care organizations and professionals, and an analysis of how consumers navigate the magazine’s website.

Ordinal ranking of hospitals that make the honor roll “obscures the fact that all of the Honor Roll hospitals have attained the highest standard of care in the nation,” the letter reads.

With the new format, honor roll hospitals are listed in alphabetical order. In 2023-2024 there are 22.

2023-2024 Honor Roll Hospitals

- Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- Cleveland Clinic

- Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Medicine, Philadelphia

- Houston Methodist Hospital

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell

- North Shore University Hospital at Northwell Health, Manhasset, N.Y.

- Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

- NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

- Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

- Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital

- UC San Diego Health–La Jolla and Hillcrest Hospitals

- UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

- UCSF Health–UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

- University of Michigan Health–Ann Arbor

- UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas

- Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

According to U.S. News, to keep pace with consumers’ needs and the ever-evolving landscape of health care, “several refinements” are reflected in the latest best hospitals rankings.

These include the introduction of outpatient outcomes in key specialty rankings and surgical ratings, the expanded inclusion of other outpatient data, an increased weight on objective quality measures, and a reduced weight on expert opinion.

In addition, hospital profiles on USNews.com feature refined health equity measures, including a new measure of racial disparities in outcomes.

The full report for best hospitals, best specialty hospitals, and methodology is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

McLean Hospital claimed the top spot in the 2022-2023 ranking as well.

Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston holds the No. 2 spot in the 2023-2024 U.S. News ranking for best psychiatry hospitals, up from No. 3 in 2022-2023.

New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell sits at No. 3 in 2023-2024, up from No. 4 in 2022-2023, while Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore is ranked No. 4, down from No. 2.

Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at the University of California, Los Angeles, is ranked No. 5 in 2023-2024 (up from No. 6 in 2022-2023), while UCSF Health–UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco, dropped to No. 6 in 2023-2024 (from No. 5 in 2022-2023).

No. 7 in 2023-2024 is Menninger Clinic, Houston, which held the No. 10 spot in 2022-2023.

According to U.S. News, the psychiatry rating is based on the expert opinion of surveyed psychiatrists. The seven ranked hospitals in psychiatry or psychiatric care were recommended by at least 5% of the psychiatric specialists responding to the magazine’s surveys in 2021, 2022, and 2023 as a facility where they would refer their patients.

“Consumers want useful resources to help them assess which hospital can best meet their specific care needs,” Ben Harder, chief of health analysis and managing editor at U.S. News, said in a statement.

“The 2023-2024 Best Hospitals rankings offer patients and the physicians with whom they consult a data-driven source for comparing performance in outcomes, patient satisfaction, and other metrics that matter to them,” Mr. Harder said.

Honor roll

This year, as in prior years, U.S. News also recognized “honor roll” hospitals that have excelled across multiple areas of care. However, in 2023-2024, for the first time, there is no ordinal ranking of hospitals making the honor roll. Instead, they are listed in alphabetical order.

In a letter to hospital leaders, U.S. News explained that the major change in format came after months of deliberation, feedback from health care organizations and professionals, and an analysis of how consumers navigate the magazine’s website.

Ordinal ranking of hospitals that make the honor roll “obscures the fact that all of the Honor Roll hospitals have attained the highest standard of care in the nation,” the letter reads.

With the new format, honor roll hospitals are listed in alphabetical order. In 2023-2024 there are 22.

2023-2024 Honor Roll Hospitals

- Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- Cleveland Clinic

- Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Medicine, Philadelphia

- Houston Methodist Hospital

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell

- North Shore University Hospital at Northwell Health, Manhasset, N.Y.

- Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

- NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

- Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

- Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital

- UC San Diego Health–La Jolla and Hillcrest Hospitals

- UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

- UCSF Health–UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

- University of Michigan Health–Ann Arbor

- UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas

- Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

According to U.S. News, to keep pace with consumers’ needs and the ever-evolving landscape of health care, “several refinements” are reflected in the latest best hospitals rankings.

These include the introduction of outpatient outcomes in key specialty rankings and surgical ratings, the expanded inclusion of other outpatient data, an increased weight on objective quality measures, and a reduced weight on expert opinion.

In addition, hospital profiles on USNews.com feature refined health equity measures, including a new measure of racial disparities in outcomes.

The full report for best hospitals, best specialty hospitals, and methodology is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

OxyContin marketing push still exacting a deadly toll, study says

The uptick in rates of infectious diseases, namely, hepatitis and infective endocarditis, occurred after 2010, when OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin to make it harder to crush and snort. This led many people who were already addicted to the powerful pain pills to move on to injecting heroin or fentanyl, which fueled the spread of infectious disease.

“Our results suggest that the mortality and morbidity consequences of OxyContin marketing continue to be salient more than 25 years later,” write Julia Dennett, PhD, and Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, with Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn.

Their study was published online in Health Affairs.

Long-term effects revealed

Until now, the long-term effects of widespread OxyContin marketing with regard to complications of injection drug use were unknown.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves evaluated the effects of OxyContin marketing on the long-term trajectories of various injection drug use–related outcomes. Using a difference-in-difference analysis, they compared states with high vs. low exposure to OxyContin marketing before and after the 2010 reformulation of the drug.

Before 2010, rates of infections associated with injection drug use and overdose deaths were similar in high- and low-marketing states, they found.

Those rates diverged after the 2010 reformulation, with more infections related to injection drug use in states exposed to more marketing.

Specifically, from 2010 until 2020, high-exposure states saw, on average, an additional 0.85 acute hepatitis B cases, 0.83 hepatitis C cases, and 0.62 cases of death from infective endocarditis per 100,000 residents.

High-exposure states also had 5.3 more deaths per 100,000 residents from synthetic opioid overdose.

“Prior to 2010, among these states, there were generally no statistically significant differences in these outcomes. After 2010, you saw them diverge dramatically,” Dr. Dennett said in a news release.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves say their findings support the view that the opioid epidemic is creating a converging public health crisis, as it is fueling a surge in infectious diseases, particularly hepatitis, infective endocarditis, and HIV.

“This study highlights a critical need for actions to address the spread of viral and bacterial infections and overdose associated with injection drug use, both in the states that were subject to Purdue’s promotional campaign and across the U.S. more broadly,” they add.

Purdue Pharma did not provide a comment on the study.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Disclosures for Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves were not available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The uptick in rates of infectious diseases, namely, hepatitis and infective endocarditis, occurred after 2010, when OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin to make it harder to crush and snort. This led many people who were already addicted to the powerful pain pills to move on to injecting heroin or fentanyl, which fueled the spread of infectious disease.

“Our results suggest that the mortality and morbidity consequences of OxyContin marketing continue to be salient more than 25 years later,” write Julia Dennett, PhD, and Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, with Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn.

Their study was published online in Health Affairs.

Long-term effects revealed

Until now, the long-term effects of widespread OxyContin marketing with regard to complications of injection drug use were unknown.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves evaluated the effects of OxyContin marketing on the long-term trajectories of various injection drug use–related outcomes. Using a difference-in-difference analysis, they compared states with high vs. low exposure to OxyContin marketing before and after the 2010 reformulation of the drug.

Before 2010, rates of infections associated with injection drug use and overdose deaths were similar in high- and low-marketing states, they found.

Those rates diverged after the 2010 reformulation, with more infections related to injection drug use in states exposed to more marketing.

Specifically, from 2010 until 2020, high-exposure states saw, on average, an additional 0.85 acute hepatitis B cases, 0.83 hepatitis C cases, and 0.62 cases of death from infective endocarditis per 100,000 residents.

High-exposure states also had 5.3 more deaths per 100,000 residents from synthetic opioid overdose.

“Prior to 2010, among these states, there were generally no statistically significant differences in these outcomes. After 2010, you saw them diverge dramatically,” Dr. Dennett said in a news release.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves say their findings support the view that the opioid epidemic is creating a converging public health crisis, as it is fueling a surge in infectious diseases, particularly hepatitis, infective endocarditis, and HIV.

“This study highlights a critical need for actions to address the spread of viral and bacterial infections and overdose associated with injection drug use, both in the states that were subject to Purdue’s promotional campaign and across the U.S. more broadly,” they add.

Purdue Pharma did not provide a comment on the study.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Disclosures for Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves were not available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The uptick in rates of infectious diseases, namely, hepatitis and infective endocarditis, occurred after 2010, when OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin to make it harder to crush and snort. This led many people who were already addicted to the powerful pain pills to move on to injecting heroin or fentanyl, which fueled the spread of infectious disease.

“Our results suggest that the mortality and morbidity consequences of OxyContin marketing continue to be salient more than 25 years later,” write Julia Dennett, PhD, and Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, with Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn.

Their study was published online in Health Affairs.

Long-term effects revealed

Until now, the long-term effects of widespread OxyContin marketing with regard to complications of injection drug use were unknown.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves evaluated the effects of OxyContin marketing on the long-term trajectories of various injection drug use–related outcomes. Using a difference-in-difference analysis, they compared states with high vs. low exposure to OxyContin marketing before and after the 2010 reformulation of the drug.

Before 2010, rates of infections associated with injection drug use and overdose deaths were similar in high- and low-marketing states, they found.

Those rates diverged after the 2010 reformulation, with more infections related to injection drug use in states exposed to more marketing.

Specifically, from 2010 until 2020, high-exposure states saw, on average, an additional 0.85 acute hepatitis B cases, 0.83 hepatitis C cases, and 0.62 cases of death from infective endocarditis per 100,000 residents.

High-exposure states also had 5.3 more deaths per 100,000 residents from synthetic opioid overdose.

“Prior to 2010, among these states, there were generally no statistically significant differences in these outcomes. After 2010, you saw them diverge dramatically,” Dr. Dennett said in a news release.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves say their findings support the view that the opioid epidemic is creating a converging public health crisis, as it is fueling a surge in infectious diseases, particularly hepatitis, infective endocarditis, and HIV.

“This study highlights a critical need for actions to address the spread of viral and bacterial infections and overdose associated with injection drug use, both in the states that were subject to Purdue’s promotional campaign and across the U.S. more broadly,” they add.

Purdue Pharma did not provide a comment on the study.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Disclosures for Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves were not available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Cigna accused of using AI, not doctors, to deny claims: Lawsuit

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves first pill for postpartum depression

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bipolar disorder tied to a sixfold increased risk of early death

In addition, patients with BD are three times more likely to die prematurely of all causes, compared with the general population, with alcohol-related diseases contributing to more premature deaths than cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and cancer.

The study results emphasize the need for personalized approaches to risk prediction and prevention of premature cause-specific mortality over the life-course of individuals with BD, lead investigator Tapio Paljärvi, PhD, an epidemiologist at Niuvanniemi Hospital in Kuopio, Finland, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in BMJ Mental Health.

Alcohol a major contributor to early death

A number of studies have established that those with BD have twice the risk of dying prematurely, compared with those without the disorder.

To learn more about the factors contributing to early death in this patient population, the investigators analyzed data from nationwide Finnish medical and insurance registries. They identified and tracked the health of 47,000 patients, aged 15-64 years, with BD between 2004 and 2018.

The average age at the beginning of the monitoring period was 38 years, and 57% of the cohort were women.

To determine the excess deaths directly attributable to BD, the researchers compared the ratio of deaths observed over the monitoring period in those with BD to the number expected to die in the general population, also known as the standard mortality ratio.

Of the group with BD, 3,300 died during the monitoring period. The average age at death was 50, and almost two-thirds (65%, or 2,137) of those who died were men.

Investigators grouped excess deaths in BD patients into two categories – somatic and external.

Of those with BD who died from somatic or disease-related causes, alcohol caused the highest rate of death (29%). The second-leading cause was heart disease and stroke (27%), followed by cancer (22%), respiratory diseases (4%), and diabetes (2%).

Among the 595 patients with BD who died because of alcohol consumption, liver disease was the leading cause of death (48%). The second cause was accidental alcohol poisoning (28%), followed by alcohol dependence (10%).

The leading cause of death from external causes in BD patients was suicide (58%, or 740), nearly half of which (48%) were from an overdose with prescribed psychotropic medications.

Overall, 64%, or 2,104, of the deaths in BD patients from any cause were considered excess deaths, that is, the number of deaths above those expected for those without BD of comparable age and sex.

Most of the excess deaths from somatic illness were either from alcohol-related causes (40%) – a rate three times higher than that of the general population – CVD (26%), or cancer (10%).

High suicide rate

When the team examined excess deaths from external causes, they found that 61% (651) were attributable to suicide, a rate eight times higher than that of the general population.

“In terms of absolute numbers, somatic causes of death represented the majority of all deaths in BD, as also reported in previous research,” Dr. Paljärvi said.

“However, this finding reflects the fact that in many high-income countries most of the deaths are due to somatic causes; with CVD, cancers, and diseases of the nervous system as the leading causes of death in the older age groups,” he added.

Dr. Paljärvi advised that clinicians treating patients with BD balance therapeutic response with potentially serious long-term medication side effects, to prevent premature deaths.

A stronger emphasis on identifying and treating comorbid substance abuse is also warranted, he noted.

Dr. Paljärvi noted that the underlying causes of the excess somatic mortality in people with BD are not fully understood, but may result from the “complex interaction between various established risk factors, including tobacco use, alcohol abuse, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, obesity, hypertension, etc.”

Regarding the generalizability of the findings, he said many previous studies have been based only on inpatient data and noted that the current study included individuals from various sources including inpatient and outpatient registries as well as social insurance registries.

“While the reported excess all-cause mortality rates are strikingly similar across populations globally, there is a paucity of more detailed cause-specific analyses of excess mortality in BD,” said Dr. Paljärvi, adding that these findings should be replicated in other countries, including the United States.

Chronic inflammation

Commenting on the findings, Benjamin Goldstein, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, noted that there are clear disparities in access to, and quality of care among, patients with BD and other serious mental illnesses.

“Taking heart disease as an example, disparities exist at virtually every point of contact, ranging from the point of preventive care to the time it takes to be assessed in the ER, to the likelihood of receiving cardiac catheterization, to the quality of postdischarge care,” said Dr. Goldstein.

He also noted that CVD occurs in patients with BD, on average, 10-15 years earlier than the general population. However, he added, “there is important evidence that when people with BD receive the same standard of care as those without BD their cardiovascular outcomes are similar.”

Dr. Goldstein also noted that inflammation, which is a driver of cardiovascular risk, is elevated among patients with BD, particularly during mania and depression.

“Given that the average person with BD has some degree of mood symptoms about 40% of the time, chronically elevated inflammation likely contributes in part to the excess risk of heart disease in bipolar disorder,” he said.

Dr. Goldstein’s team’s research focuses on microvessels. “We have found that microvessel function in both the heart and the brain, determined by MRI, is reduced among teens with BD,” he said.

His team has also found that endothelial function in fingertip microvessels, an indicator of future heart disease risk, varies according to mood states.

“Collectively, these findings suggest the microvascular problems may explain, in part, the extra risk of heart disease beyond traditional risk factors in BD,” he added.

The study was funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Research Fellowship and by the Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Paljärvi and Dr. Goldstein report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, patients with BD are three times more likely to die prematurely of all causes, compared with the general population, with alcohol-related diseases contributing to more premature deaths than cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and cancer.

The study results emphasize the need for personalized approaches to risk prediction and prevention of premature cause-specific mortality over the life-course of individuals with BD, lead investigator Tapio Paljärvi, PhD, an epidemiologist at Niuvanniemi Hospital in Kuopio, Finland, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in BMJ Mental Health.

Alcohol a major contributor to early death

A number of studies have established that those with BD have twice the risk of dying prematurely, compared with those without the disorder.

To learn more about the factors contributing to early death in this patient population, the investigators analyzed data from nationwide Finnish medical and insurance registries. They identified and tracked the health of 47,000 patients, aged 15-64 years, with BD between 2004 and 2018.

The average age at the beginning of the monitoring period was 38 years, and 57% of the cohort were women.

To determine the excess deaths directly attributable to BD, the researchers compared the ratio of deaths observed over the monitoring period in those with BD to the number expected to die in the general population, also known as the standard mortality ratio.

Of the group with BD, 3,300 died during the monitoring period. The average age at death was 50, and almost two-thirds (65%, or 2,137) of those who died were men.

Investigators grouped excess deaths in BD patients into two categories – somatic and external.

Of those with BD who died from somatic or disease-related causes, alcohol caused the highest rate of death (29%). The second-leading cause was heart disease and stroke (27%), followed by cancer (22%), respiratory diseases (4%), and diabetes (2%).

Among the 595 patients with BD who died because of alcohol consumption, liver disease was the leading cause of death (48%). The second cause was accidental alcohol poisoning (28%), followed by alcohol dependence (10%).

The leading cause of death from external causes in BD patients was suicide (58%, or 740), nearly half of which (48%) were from an overdose with prescribed psychotropic medications.

Overall, 64%, or 2,104, of the deaths in BD patients from any cause were considered excess deaths, that is, the number of deaths above those expected for those without BD of comparable age and sex.

Most of the excess deaths from somatic illness were either from alcohol-related causes (40%) – a rate three times higher than that of the general population – CVD (26%), or cancer (10%).

High suicide rate

When the team examined excess deaths from external causes, they found that 61% (651) were attributable to suicide, a rate eight times higher than that of the general population.

“In terms of absolute numbers, somatic causes of death represented the majority of all deaths in BD, as also reported in previous research,” Dr. Paljärvi said.

“However, this finding reflects the fact that in many high-income countries most of the deaths are due to somatic causes; with CVD, cancers, and diseases of the nervous system as the leading causes of death in the older age groups,” he added.

Dr. Paljärvi advised that clinicians treating patients with BD balance therapeutic response with potentially serious long-term medication side effects, to prevent premature deaths.

A stronger emphasis on identifying and treating comorbid substance abuse is also warranted, he noted.

Dr. Paljärvi noted that the underlying causes of the excess somatic mortality in people with BD are not fully understood, but may result from the “complex interaction between various established risk factors, including tobacco use, alcohol abuse, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, obesity, hypertension, etc.”

Regarding the generalizability of the findings, he said many previous studies have been based only on inpatient data and noted that the current study included individuals from various sources including inpatient and outpatient registries as well as social insurance registries.

“While the reported excess all-cause mortality rates are strikingly similar across populations globally, there is a paucity of more detailed cause-specific analyses of excess mortality in BD,” said Dr. Paljärvi, adding that these findings should be replicated in other countries, including the United States.

Chronic inflammation

Commenting on the findings, Benjamin Goldstein, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, noted that there are clear disparities in access to, and quality of care among, patients with BD and other serious mental illnesses.

“Taking heart disease as an example, disparities exist at virtually every point of contact, ranging from the point of preventive care to the time it takes to be assessed in the ER, to the likelihood of receiving cardiac catheterization, to the quality of postdischarge care,” said Dr. Goldstein.

He also noted that CVD occurs in patients with BD, on average, 10-15 years earlier than the general population. However, he added, “there is important evidence that when people with BD receive the same standard of care as those without BD their cardiovascular outcomes are similar.”

Dr. Goldstein also noted that inflammation, which is a driver of cardiovascular risk, is elevated among patients with BD, particularly during mania and depression.

“Given that the average person with BD has some degree of mood symptoms about 40% of the time, chronically elevated inflammation likely contributes in part to the excess risk of heart disease in bipolar disorder,” he said.

Dr. Goldstein’s team’s research focuses on microvessels. “We have found that microvessel function in both the heart and the brain, determined by MRI, is reduced among teens with BD,” he said.

His team has also found that endothelial function in fingertip microvessels, an indicator of future heart disease risk, varies according to mood states.

“Collectively, these findings suggest the microvascular problems may explain, in part, the extra risk of heart disease beyond traditional risk factors in BD,” he added.

The study was funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Research Fellowship and by the Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Paljärvi and Dr. Goldstein report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, patients with BD are three times more likely to die prematurely of all causes, compared with the general population, with alcohol-related diseases contributing to more premature deaths than cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and cancer.

The study results emphasize the need for personalized approaches to risk prediction and prevention of premature cause-specific mortality over the life-course of individuals with BD, lead investigator Tapio Paljärvi, PhD, an epidemiologist at Niuvanniemi Hospital in Kuopio, Finland, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in BMJ Mental Health.

Alcohol a major contributor to early death

A number of studies have established that those with BD have twice the risk of dying prematurely, compared with those without the disorder.

To learn more about the factors contributing to early death in this patient population, the investigators analyzed data from nationwide Finnish medical and insurance registries. They identified and tracked the health of 47,000 patients, aged 15-64 years, with BD between 2004 and 2018.

The average age at the beginning of the monitoring period was 38 years, and 57% of the cohort were women.

To determine the excess deaths directly attributable to BD, the researchers compared the ratio of deaths observed over the monitoring period in those with BD to the number expected to die in the general population, also known as the standard mortality ratio.

Of the group with BD, 3,300 died during the monitoring period. The average age at death was 50, and almost two-thirds (65%, or 2,137) of those who died were men.

Investigators grouped excess deaths in BD patients into two categories – somatic and external.

Of those with BD who died from somatic or disease-related causes, alcohol caused the highest rate of death (29%). The second-leading cause was heart disease and stroke (27%), followed by cancer (22%), respiratory diseases (4%), and diabetes (2%).

Among the 595 patients with BD who died because of alcohol consumption, liver disease was the leading cause of death (48%). The second cause was accidental alcohol poisoning (28%), followed by alcohol dependence (10%).

The leading cause of death from external causes in BD patients was suicide (58%, or 740), nearly half of which (48%) were from an overdose with prescribed psychotropic medications.

Overall, 64%, or 2,104, of the deaths in BD patients from any cause were considered excess deaths, that is, the number of deaths above those expected for those without BD of comparable age and sex.

Most of the excess deaths from somatic illness were either from alcohol-related causes (40%) – a rate three times higher than that of the general population – CVD (26%), or cancer (10%).

High suicide rate

When the team examined excess deaths from external causes, they found that 61% (651) were attributable to suicide, a rate eight times higher than that of the general population.

“In terms of absolute numbers, somatic causes of death represented the majority of all deaths in BD, as also reported in previous research,” Dr. Paljärvi said.

“However, this finding reflects the fact that in many high-income countries most of the deaths are due to somatic causes; with CVD, cancers, and diseases of the nervous system as the leading causes of death in the older age groups,” he added.

Dr. Paljärvi advised that clinicians treating patients with BD balance therapeutic response with potentially serious long-term medication side effects, to prevent premature deaths.

A stronger emphasis on identifying and treating comorbid substance abuse is also warranted, he noted.

Dr. Paljärvi noted that the underlying causes of the excess somatic mortality in people with BD are not fully understood, but may result from the “complex interaction between various established risk factors, including tobacco use, alcohol abuse, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, obesity, hypertension, etc.”

Regarding the generalizability of the findings, he said many previous studies have been based only on inpatient data and noted that the current study included individuals from various sources including inpatient and outpatient registries as well as social insurance registries.

“While the reported excess all-cause mortality rates are strikingly similar across populations globally, there is a paucity of more detailed cause-specific analyses of excess mortality in BD,” said Dr. Paljärvi, adding that these findings should be replicated in other countries, including the United States.

Chronic inflammation

Commenting on the findings, Benjamin Goldstein, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, noted that there are clear disparities in access to, and quality of care among, patients with BD and other serious mental illnesses.

“Taking heart disease as an example, disparities exist at virtually every point of contact, ranging from the point of preventive care to the time it takes to be assessed in the ER, to the likelihood of receiving cardiac catheterization, to the quality of postdischarge care,” said Dr. Goldstein.

He also noted that CVD occurs in patients with BD, on average, 10-15 years earlier than the general population. However, he added, “there is important evidence that when people with BD receive the same standard of care as those without BD their cardiovascular outcomes are similar.”

Dr. Goldstein also noted that inflammation, which is a driver of cardiovascular risk, is elevated among patients with BD, particularly during mania and depression.

“Given that the average person with BD has some degree of mood symptoms about 40% of the time, chronically elevated inflammation likely contributes in part to the excess risk of heart disease in bipolar disorder,” he said.

Dr. Goldstein’s team’s research focuses on microvessels. “We have found that microvessel function in both the heart and the brain, determined by MRI, is reduced among teens with BD,” he said.

His team has also found that endothelial function in fingertip microvessels, an indicator of future heart disease risk, varies according to mood states.

“Collectively, these findings suggest the microvascular problems may explain, in part, the extra risk of heart disease beyond traditional risk factors in BD,” he added.

The study was funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Research Fellowship and by the Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Paljärvi and Dr. Goldstein report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ MENTAL HEALTH

A new and completely different pain medicine

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

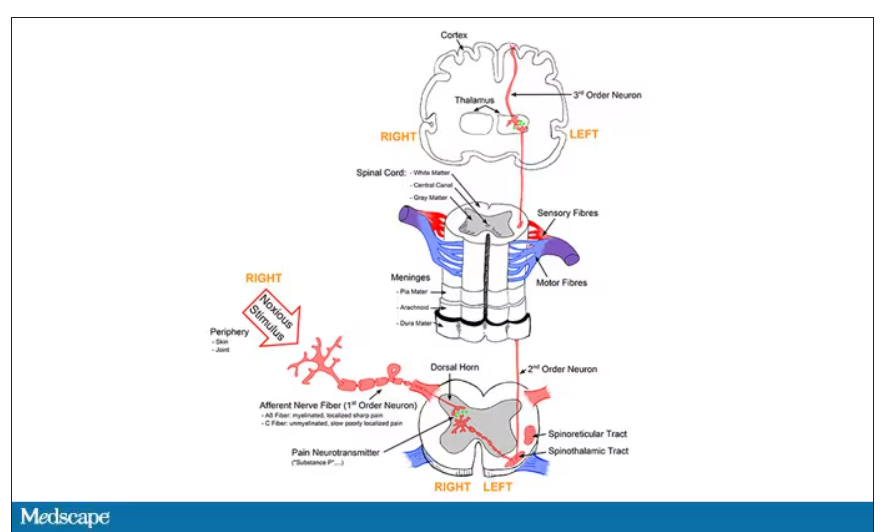

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

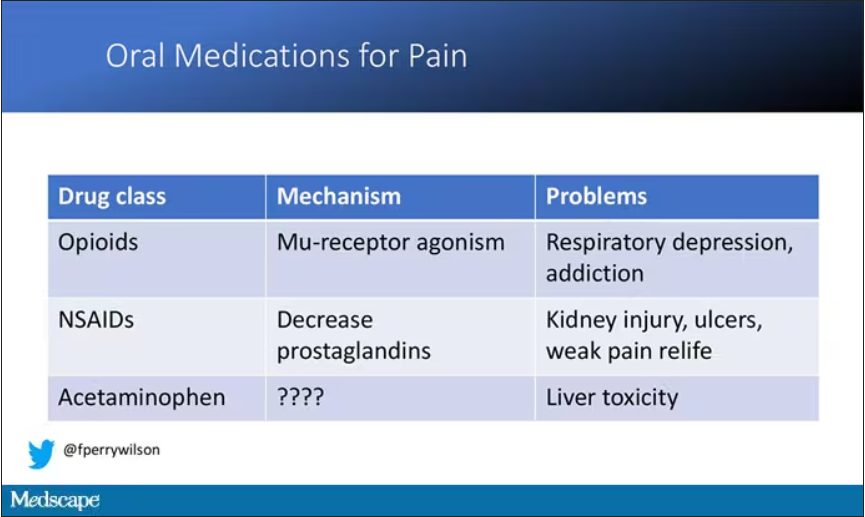

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

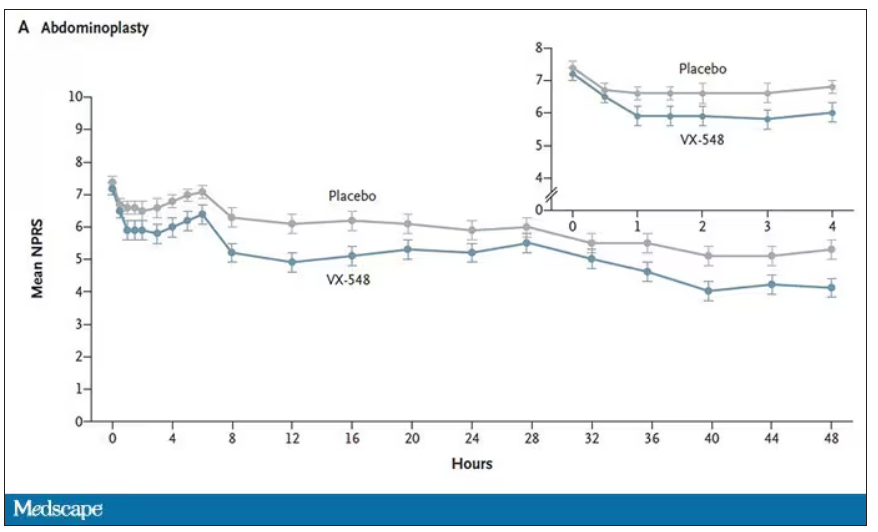

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

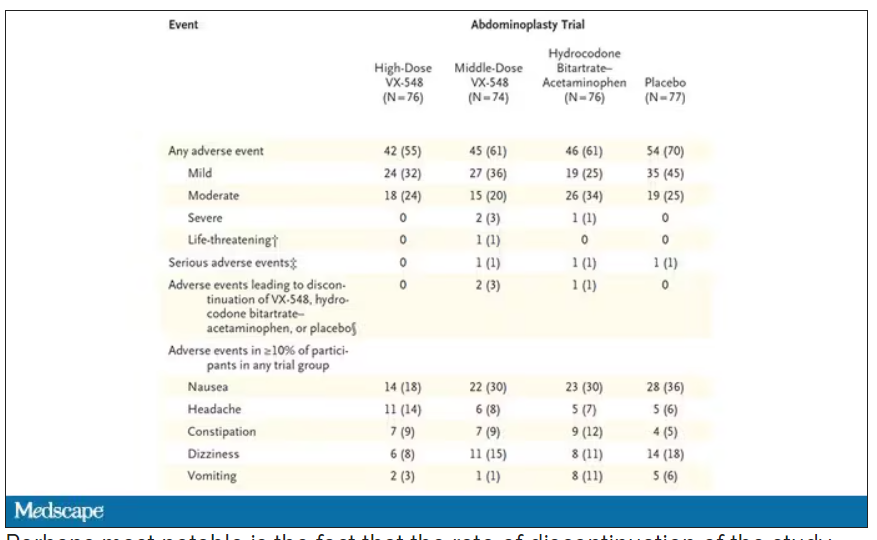

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

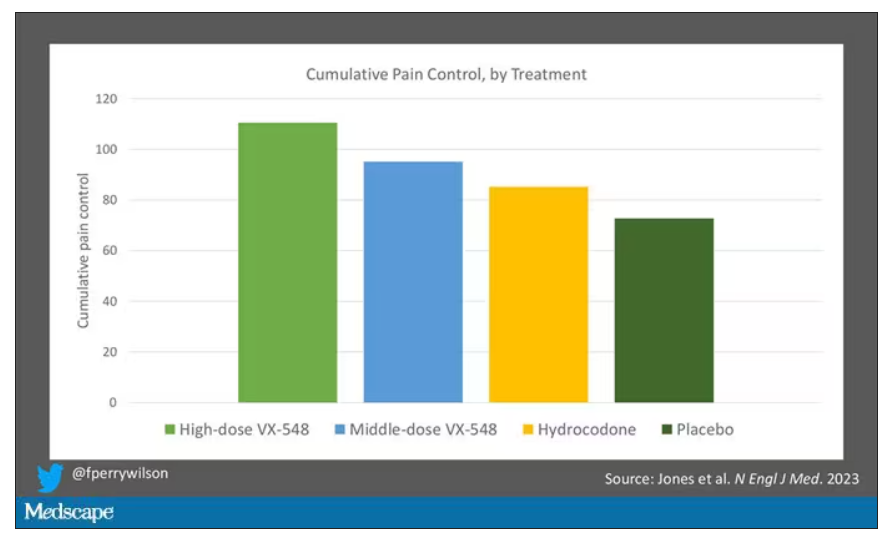

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.