User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

If you reopen it, will they come?

On April 16, the White House released federal guidelines for reopening American businesses – followed 3 days later by specific recommendations from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for .

Depending on where you live, you may have already reopened (or even never closed), or you may be awaiting the relaxation of restrictions in your state. (As I write this on June 10, the stay-at-home order in my state, New Jersey, is being rescinded.)

The big question, of course, is whether patients can be convinced that it is safe to leave their homes and come to your office. The answer may depend on how well you time your reopening and adhere to the appropriate federal, state, and independent guidelines.

The federal guidelines have three sections: criteria, which outline conditions each region or state should satisfy before reopening; preparedness, which lists how states should prepare for reopening; and phase guidelines, which detail responsibilities of individuals and employers during distinct reopening phases.

You should pay the most attention to the “criteria” section. The key question to ask: “Has my state or region satisfied the basic criteria for reopening?”

Those criteria are as follows:

- Symptoms reported within a 14-day period should be on a downward trajectory.

- Cases documented (or positive tests as a percentage of total tests) within a 14-day period should also be on a downward trajectory.

- Hospitals should be treating all patients without crisis care. They should also have a robust testing program in place for at-risk health care workers.

If your area meets these criteria, you can proceed to the CMS recommendations. They cover general advice related to personal protective equipment (PPE), workforce availability, facility considerations, sanitation protocols, supplies, and testing capacity.

The key takeaway: As long as your area has the resources to quickly respond to a surge of COVID-19 cases, you can start offering care to non-COVID patients. Keep seeing patients via telehealth as often as possible, and prioritize surgical/procedural care and high-complexity chronic disease management before moving on to preventive and cosmetic services.

The American Medical Association has issued its own checklist of criteria for reopening your practice to supplement the federal guidelines. Highlights include the following:

- Sit down with a calendar and pick an expected reopening day. Ideally, this should include a “soft reopening.” Make a plan to stock necessary PPE and write down plans for cleaning and staffing if an employee or patient is diagnosed with COVID-19 after visiting your office.

- Take a stepwise approach so you can identify challenges early and address them. It’s important to figure out which visits can continue via telehealth, and begin with just a few in-person visits each day. Plan out a schedule and clearly communicate it to patients, clinicians, and staff.

- Patient safety is your top concern. Encourage patients to visit without companions whenever possible, and of course, all individuals who visit the office should wear a cloth face covering.

- Screen employees for fevers and other symptoms of COVID-19; remember that those records are subject to HIPAA rules and must be kept confidential. Minimize contact between employees as much as possible.

- Do your best to screen patients before in-person visits, to verify they don’t have symptoms of COVID-19. Consider creating a script that office staff can use to contact patients 24 hours before they come in. Use this as a chance to ask about symptoms, and explain any reopening logistics they should know about.

- Contact your malpractice insurance carrier to discuss whether you need to make any changes to your coverage.

This would also be a great time to review your confidentiality, privacy, and data security protocols. COVID-19 presents new challenges for data privacy – for example, if you must inform coworkers or patients that they have come into contact with someone who tested positive. Make a plan that follows HIPAA guidelines during COVID-19. Also, make sure you have a plan for handling issues like paid sick leave or reporting COVID-19 cases to your local health department.

Another useful resource is the Medical Group Management Association’s COVID-19 Medical Practice Reopening Checklist. You can use it to confirm that you are addressing all the important items, and that you haven’t missed anything.

As for me, I am advising patients who are reluctant to seek treatment that many medical problems pose more risk than COVID-19, faster treatment means better outcomes, and because we maintain strict disinfection protocols, they are far less likely to be infected with COVID-19 in my office than, say, at a grocery store.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

On April 16, the White House released federal guidelines for reopening American businesses – followed 3 days later by specific recommendations from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for .

Depending on where you live, you may have already reopened (or even never closed), or you may be awaiting the relaxation of restrictions in your state. (As I write this on June 10, the stay-at-home order in my state, New Jersey, is being rescinded.)

The big question, of course, is whether patients can be convinced that it is safe to leave their homes and come to your office. The answer may depend on how well you time your reopening and adhere to the appropriate federal, state, and independent guidelines.

The federal guidelines have three sections: criteria, which outline conditions each region or state should satisfy before reopening; preparedness, which lists how states should prepare for reopening; and phase guidelines, which detail responsibilities of individuals and employers during distinct reopening phases.

You should pay the most attention to the “criteria” section. The key question to ask: “Has my state or region satisfied the basic criteria for reopening?”

Those criteria are as follows:

- Symptoms reported within a 14-day period should be on a downward trajectory.

- Cases documented (or positive tests as a percentage of total tests) within a 14-day period should also be on a downward trajectory.

- Hospitals should be treating all patients without crisis care. They should also have a robust testing program in place for at-risk health care workers.

If your area meets these criteria, you can proceed to the CMS recommendations. They cover general advice related to personal protective equipment (PPE), workforce availability, facility considerations, sanitation protocols, supplies, and testing capacity.

The key takeaway: As long as your area has the resources to quickly respond to a surge of COVID-19 cases, you can start offering care to non-COVID patients. Keep seeing patients via telehealth as often as possible, and prioritize surgical/procedural care and high-complexity chronic disease management before moving on to preventive and cosmetic services.

The American Medical Association has issued its own checklist of criteria for reopening your practice to supplement the federal guidelines. Highlights include the following:

- Sit down with a calendar and pick an expected reopening day. Ideally, this should include a “soft reopening.” Make a plan to stock necessary PPE and write down plans for cleaning and staffing if an employee or patient is diagnosed with COVID-19 after visiting your office.

- Take a stepwise approach so you can identify challenges early and address them. It’s important to figure out which visits can continue via telehealth, and begin with just a few in-person visits each day. Plan out a schedule and clearly communicate it to patients, clinicians, and staff.

- Patient safety is your top concern. Encourage patients to visit without companions whenever possible, and of course, all individuals who visit the office should wear a cloth face covering.

- Screen employees for fevers and other symptoms of COVID-19; remember that those records are subject to HIPAA rules and must be kept confidential. Minimize contact between employees as much as possible.

- Do your best to screen patients before in-person visits, to verify they don’t have symptoms of COVID-19. Consider creating a script that office staff can use to contact patients 24 hours before they come in. Use this as a chance to ask about symptoms, and explain any reopening logistics they should know about.

- Contact your malpractice insurance carrier to discuss whether you need to make any changes to your coverage.

This would also be a great time to review your confidentiality, privacy, and data security protocols. COVID-19 presents new challenges for data privacy – for example, if you must inform coworkers or patients that they have come into contact with someone who tested positive. Make a plan that follows HIPAA guidelines during COVID-19. Also, make sure you have a plan for handling issues like paid sick leave or reporting COVID-19 cases to your local health department.

Another useful resource is the Medical Group Management Association’s COVID-19 Medical Practice Reopening Checklist. You can use it to confirm that you are addressing all the important items, and that you haven’t missed anything.

As for me, I am advising patients who are reluctant to seek treatment that many medical problems pose more risk than COVID-19, faster treatment means better outcomes, and because we maintain strict disinfection protocols, they are far less likely to be infected with COVID-19 in my office than, say, at a grocery store.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

On April 16, the White House released federal guidelines for reopening American businesses – followed 3 days later by specific recommendations from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for .

Depending on where you live, you may have already reopened (or even never closed), or you may be awaiting the relaxation of restrictions in your state. (As I write this on June 10, the stay-at-home order in my state, New Jersey, is being rescinded.)

The big question, of course, is whether patients can be convinced that it is safe to leave their homes and come to your office. The answer may depend on how well you time your reopening and adhere to the appropriate federal, state, and independent guidelines.

The federal guidelines have three sections: criteria, which outline conditions each region or state should satisfy before reopening; preparedness, which lists how states should prepare for reopening; and phase guidelines, which detail responsibilities of individuals and employers during distinct reopening phases.

You should pay the most attention to the “criteria” section. The key question to ask: “Has my state or region satisfied the basic criteria for reopening?”

Those criteria are as follows:

- Symptoms reported within a 14-day period should be on a downward trajectory.

- Cases documented (or positive tests as a percentage of total tests) within a 14-day period should also be on a downward trajectory.

- Hospitals should be treating all patients without crisis care. They should also have a robust testing program in place for at-risk health care workers.

If your area meets these criteria, you can proceed to the CMS recommendations. They cover general advice related to personal protective equipment (PPE), workforce availability, facility considerations, sanitation protocols, supplies, and testing capacity.

The key takeaway: As long as your area has the resources to quickly respond to a surge of COVID-19 cases, you can start offering care to non-COVID patients. Keep seeing patients via telehealth as often as possible, and prioritize surgical/procedural care and high-complexity chronic disease management before moving on to preventive and cosmetic services.

The American Medical Association has issued its own checklist of criteria for reopening your practice to supplement the federal guidelines. Highlights include the following:

- Sit down with a calendar and pick an expected reopening day. Ideally, this should include a “soft reopening.” Make a plan to stock necessary PPE and write down plans for cleaning and staffing if an employee or patient is diagnosed with COVID-19 after visiting your office.

- Take a stepwise approach so you can identify challenges early and address them. It’s important to figure out which visits can continue via telehealth, and begin with just a few in-person visits each day. Plan out a schedule and clearly communicate it to patients, clinicians, and staff.

- Patient safety is your top concern. Encourage patients to visit without companions whenever possible, and of course, all individuals who visit the office should wear a cloth face covering.

- Screen employees for fevers and other symptoms of COVID-19; remember that those records are subject to HIPAA rules and must be kept confidential. Minimize contact between employees as much as possible.

- Do your best to screen patients before in-person visits, to verify they don’t have symptoms of COVID-19. Consider creating a script that office staff can use to contact patients 24 hours before they come in. Use this as a chance to ask about symptoms, and explain any reopening logistics they should know about.

- Contact your malpractice insurance carrier to discuss whether you need to make any changes to your coverage.

This would also be a great time to review your confidentiality, privacy, and data security protocols. COVID-19 presents new challenges for data privacy – for example, if you must inform coworkers or patients that they have come into contact with someone who tested positive. Make a plan that follows HIPAA guidelines during COVID-19. Also, make sure you have a plan for handling issues like paid sick leave or reporting COVID-19 cases to your local health department.

Another useful resource is the Medical Group Management Association’s COVID-19 Medical Practice Reopening Checklist. You can use it to confirm that you are addressing all the important items, and that you haven’t missed anything.

As for me, I am advising patients who are reluctant to seek treatment that many medical problems pose more risk than COVID-19, faster treatment means better outcomes, and because we maintain strict disinfection protocols, they are far less likely to be infected with COVID-19 in my office than, say, at a grocery store.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

New long-term data for antipsychotic in pediatric bipolar depression

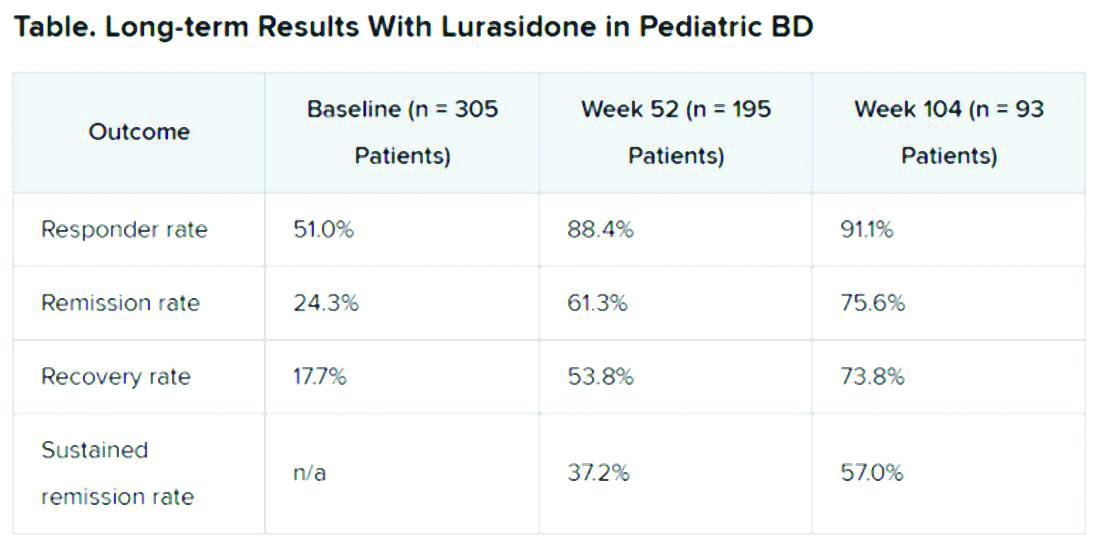

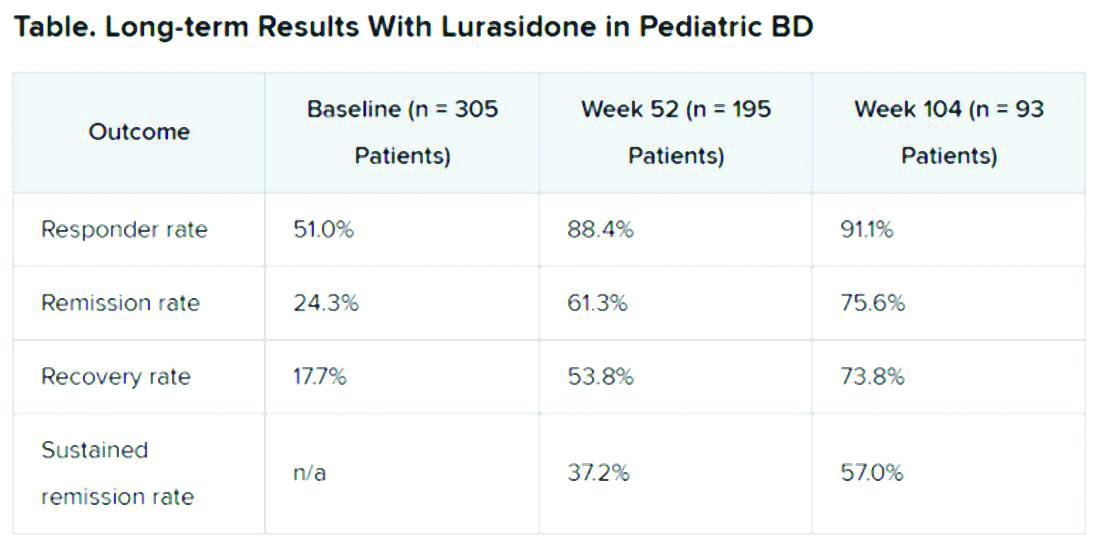

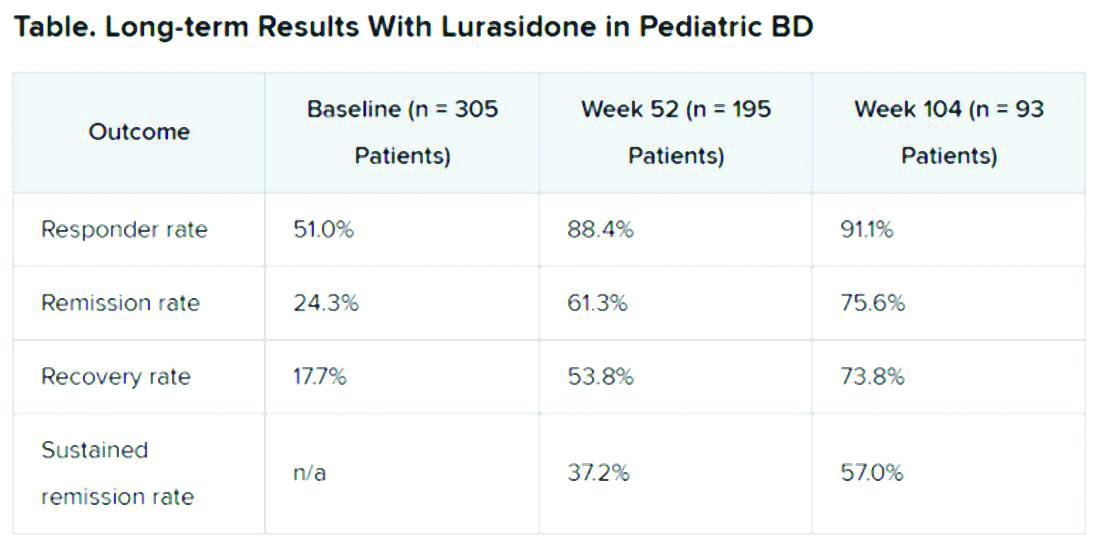

The antipsychotic lurasidone (Latuda, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals) has long-term efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression (BD) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

In an open-label extension study involving patients aged 10-17 years, up to 2 years of treatment with lurasidone was associated with continued improvement in depressive symptoms. There were progressively higher rates of remission, recovery, and sustained remission.

Coinvestigator Manpreet K. Singh, MD, director of the Stanford Pediatric Mood Disorders Program, Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that early onset of BD is common. Although in pediatric populations, prevalence has been fairly stable at around 1.8%, these patients have “a very limited number of treatment options available for the depressed phases of BD,” which is often predominant and can be difficult to identify.

“A lot of youths who are experiencing depressive symptoms in the context of having had a manic episode will often have a relapsing and remitting course, even after the acute phase of treatment, so because kids can be on medications for long periods of time, a better understanding of what works ... is very important,” Dr. Singh said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 annual meeting.

Long-term Efficacy

The Food and Drug Administration approved lurasidone as monotherapy for BD in children and adolescents in 2018. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the drug’s long-term efficacy in achieving response or remission in this population.

A total of 305 children who completed an initial 6-week double-blind study of lurasidone versus placebo entered the 2-year, open-label extension study. In the extension, they either continued taking lurasidone or were switched from placebo to lurasidone 20-80 mg/day. Of this group, 195 children completed 52 weeks of treatment, and 93 completed 104 weeks of treatment.

Efficacy was measured with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) and the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar Depression Severity scale (CGI-BP-S). Functioning was evaluated with the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS); on that scale, a score of 70 or higher indicates no clinically meaningful functional impairment.

Remission criteria were met if a patient achieved a CDRS-R total score of 28 or less, a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score of 8 or less, and a CGI-BP-S depression score of 3 or less.

Recovery criteria were met if a patient achieved remission and had a CGAS score of at least 70.

Sustained remission, a more stringent outcome, required that the patient meet remission criteria for at least 24 consecutive weeks.

In addition, there was a strong inverse correlation (r = –0.71) between depression severity, as measured by CDRS-R total score, and functioning, as measured by the CGAS.

“That’s the cool thing: As the depression symptoms and severity came down, the overall functioning in these kids improved,” Dr. Singh noted.

“This improvement in functioning ends up being much more clinically relevant and useful to clinicians than just showing an improvement in a set of symptoms because what brings a kid – or even an adult, for that matter – to see a clinician to get treatment is because something about their symptoms is causing significant functional impairment,” she said.

“So this is the take-home message: You can see that lurasidone ... demonstrates not just recovery from depressive symptoms but that this reduction in depressive symptoms corresponds to an improvement in functioning for these youths,” she added.

Potential Limitations

Commenting on the study, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, Charite Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany, noted that BD is difficult to treat, especially for patients who are going through “a developmentally vulnerable phase of their lives.”

“Lurasidone is the only monotherapy approved for bipolar depression in youth and is fairly well tolerated,” said Dr. Correll, who was not part of the research. He added that the long-term effectiveness data on response and remission “add relevant information” to the field.

However, he noted that it is not clear whether the high and increasing rates of response and remission were based on the reporting of observed cases or on last-observation-carried-forward analyses. “Given the naturally high dropout rate in such a long-term study and the potential for a survival bias, this is a relevant methodological question that affects the interpretation of the data,” he said.

“Nevertheless, the very favorable results for cumulative response, remission, and sustained remission add to the evidence that lurasidone is an effective treatment for youth with bipolar depression. Since efficacy cannot be interpreted in isolation, data describing the tolerability, including long-term cardiometabolic effects, will be important complementary data to consider,” Dr. Correll said.

The study was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Singh is on the advisory board for Sunovion, is a consultant for Google X and Limbix, and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing. She has also received research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Department of Psychiatry, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, PCORI, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Correll has been a consultant or adviser to and has received honoraria from Sunovion, as well as Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The antipsychotic lurasidone (Latuda, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals) has long-term efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression (BD) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

In an open-label extension study involving patients aged 10-17 years, up to 2 years of treatment with lurasidone was associated with continued improvement in depressive symptoms. There were progressively higher rates of remission, recovery, and sustained remission.

Coinvestigator Manpreet K. Singh, MD, director of the Stanford Pediatric Mood Disorders Program, Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that early onset of BD is common. Although in pediatric populations, prevalence has been fairly stable at around 1.8%, these patients have “a very limited number of treatment options available for the depressed phases of BD,” which is often predominant and can be difficult to identify.

“A lot of youths who are experiencing depressive symptoms in the context of having had a manic episode will often have a relapsing and remitting course, even after the acute phase of treatment, so because kids can be on medications for long periods of time, a better understanding of what works ... is very important,” Dr. Singh said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 annual meeting.

Long-term Efficacy

The Food and Drug Administration approved lurasidone as monotherapy for BD in children and adolescents in 2018. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the drug’s long-term efficacy in achieving response or remission in this population.

A total of 305 children who completed an initial 6-week double-blind study of lurasidone versus placebo entered the 2-year, open-label extension study. In the extension, they either continued taking lurasidone or were switched from placebo to lurasidone 20-80 mg/day. Of this group, 195 children completed 52 weeks of treatment, and 93 completed 104 weeks of treatment.

Efficacy was measured with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) and the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar Depression Severity scale (CGI-BP-S). Functioning was evaluated with the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS); on that scale, a score of 70 or higher indicates no clinically meaningful functional impairment.

Remission criteria were met if a patient achieved a CDRS-R total score of 28 or less, a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score of 8 or less, and a CGI-BP-S depression score of 3 or less.

Recovery criteria were met if a patient achieved remission and had a CGAS score of at least 70.

Sustained remission, a more stringent outcome, required that the patient meet remission criteria for at least 24 consecutive weeks.

In addition, there was a strong inverse correlation (r = –0.71) between depression severity, as measured by CDRS-R total score, and functioning, as measured by the CGAS.

“That’s the cool thing: As the depression symptoms and severity came down, the overall functioning in these kids improved,” Dr. Singh noted.

“This improvement in functioning ends up being much more clinically relevant and useful to clinicians than just showing an improvement in a set of symptoms because what brings a kid – or even an adult, for that matter – to see a clinician to get treatment is because something about their symptoms is causing significant functional impairment,” she said.

“So this is the take-home message: You can see that lurasidone ... demonstrates not just recovery from depressive symptoms but that this reduction in depressive symptoms corresponds to an improvement in functioning for these youths,” she added.

Potential Limitations

Commenting on the study, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, Charite Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany, noted that BD is difficult to treat, especially for patients who are going through “a developmentally vulnerable phase of their lives.”

“Lurasidone is the only monotherapy approved for bipolar depression in youth and is fairly well tolerated,” said Dr. Correll, who was not part of the research. He added that the long-term effectiveness data on response and remission “add relevant information” to the field.

However, he noted that it is not clear whether the high and increasing rates of response and remission were based on the reporting of observed cases or on last-observation-carried-forward analyses. “Given the naturally high dropout rate in such a long-term study and the potential for a survival bias, this is a relevant methodological question that affects the interpretation of the data,” he said.

“Nevertheless, the very favorable results for cumulative response, remission, and sustained remission add to the evidence that lurasidone is an effective treatment for youth with bipolar depression. Since efficacy cannot be interpreted in isolation, data describing the tolerability, including long-term cardiometabolic effects, will be important complementary data to consider,” Dr. Correll said.

The study was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Singh is on the advisory board for Sunovion, is a consultant for Google X and Limbix, and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing. She has also received research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Department of Psychiatry, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, PCORI, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Correll has been a consultant or adviser to and has received honoraria from Sunovion, as well as Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The antipsychotic lurasidone (Latuda, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals) has long-term efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression (BD) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

In an open-label extension study involving patients aged 10-17 years, up to 2 years of treatment with lurasidone was associated with continued improvement in depressive symptoms. There were progressively higher rates of remission, recovery, and sustained remission.

Coinvestigator Manpreet K. Singh, MD, director of the Stanford Pediatric Mood Disorders Program, Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that early onset of BD is common. Although in pediatric populations, prevalence has been fairly stable at around 1.8%, these patients have “a very limited number of treatment options available for the depressed phases of BD,” which is often predominant and can be difficult to identify.

“A lot of youths who are experiencing depressive symptoms in the context of having had a manic episode will often have a relapsing and remitting course, even after the acute phase of treatment, so because kids can be on medications for long periods of time, a better understanding of what works ... is very important,” Dr. Singh said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 annual meeting.

Long-term Efficacy

The Food and Drug Administration approved lurasidone as monotherapy for BD in children and adolescents in 2018. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the drug’s long-term efficacy in achieving response or remission in this population.

A total of 305 children who completed an initial 6-week double-blind study of lurasidone versus placebo entered the 2-year, open-label extension study. In the extension, they either continued taking lurasidone or were switched from placebo to lurasidone 20-80 mg/day. Of this group, 195 children completed 52 weeks of treatment, and 93 completed 104 weeks of treatment.

Efficacy was measured with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) and the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar Depression Severity scale (CGI-BP-S). Functioning was evaluated with the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS); on that scale, a score of 70 or higher indicates no clinically meaningful functional impairment.

Remission criteria were met if a patient achieved a CDRS-R total score of 28 or less, a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score of 8 or less, and a CGI-BP-S depression score of 3 or less.

Recovery criteria were met if a patient achieved remission and had a CGAS score of at least 70.

Sustained remission, a more stringent outcome, required that the patient meet remission criteria for at least 24 consecutive weeks.

In addition, there was a strong inverse correlation (r = –0.71) between depression severity, as measured by CDRS-R total score, and functioning, as measured by the CGAS.

“That’s the cool thing: As the depression symptoms and severity came down, the overall functioning in these kids improved,” Dr. Singh noted.

“This improvement in functioning ends up being much more clinically relevant and useful to clinicians than just showing an improvement in a set of symptoms because what brings a kid – or even an adult, for that matter – to see a clinician to get treatment is because something about their symptoms is causing significant functional impairment,” she said.

“So this is the take-home message: You can see that lurasidone ... demonstrates not just recovery from depressive symptoms but that this reduction in depressive symptoms corresponds to an improvement in functioning for these youths,” she added.

Potential Limitations

Commenting on the study, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, Charite Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany, noted that BD is difficult to treat, especially for patients who are going through “a developmentally vulnerable phase of their lives.”

“Lurasidone is the only monotherapy approved for bipolar depression in youth and is fairly well tolerated,” said Dr. Correll, who was not part of the research. He added that the long-term effectiveness data on response and remission “add relevant information” to the field.

However, he noted that it is not clear whether the high and increasing rates of response and remission were based on the reporting of observed cases or on last-observation-carried-forward analyses. “Given the naturally high dropout rate in such a long-term study and the potential for a survival bias, this is a relevant methodological question that affects the interpretation of the data,” he said.

“Nevertheless, the very favorable results for cumulative response, remission, and sustained remission add to the evidence that lurasidone is an effective treatment for youth with bipolar depression. Since efficacy cannot be interpreted in isolation, data describing the tolerability, including long-term cardiometabolic effects, will be important complementary data to consider,” Dr. Correll said.

The study was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Singh is on the advisory board for Sunovion, is a consultant for Google X and Limbix, and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing. She has also received research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Department of Psychiatry, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, PCORI, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Correll has been a consultant or adviser to and has received honoraria from Sunovion, as well as Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCP 2020

Daily Recap: Feds seek COVID-19 info through app, hospitalists take on new roles

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

FDA seeks COVID-19 info through CURE ID

Federal health officials are asking clinicians to use the free CURE ID mobile app and web platform as a tool to collect information on the treatment of patients with COVID-19. CURE ID is an Internet-based data repository first developed in 2013 as a collaboration between the Food and Drug Administration and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health. It provides licensed clinicians worldwide with an opportunity to report novel uses of existing drugs for patients with difficult-to-treat infectious diseases, including COVID-19, through a website, a smartphone, or other mobile device. “By utilizing the CURE ID platform now for COVID-19 case collection – in conjunction with data gathered from other registries, EHR systems, and clinical trials – data collected during an outbreak can be improved and coordinated,” said Heather A. Stone, MPH, a health science policy analyst in the office of medical policy at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “This may allow us to find possible treatments to help ease this pandemic, and prepare us better to fight the next one.” Read more.

Hospitalists take on new roles in COVID era

Whether it’s working shifts in the ICU, caring for ventilator patients, or reporting to postanesthesia care units and post-acute or step-down units, hospitalists are stepping into a variety of new roles as part of their frontline response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Valerie Vaughn, MD, a hospitalist with Michigan Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, was doing research on how to reduce overuse of antibiotics in hospitals when the COVID-19 crisis hit and dramatically redefined her job. “We were afraid that we might have 3,000 to 5,000 hospitalized COVID patients by now, based on predictive modeling done while the pandemic was still growing exponentially,” she explained. Although Michigan continues to have high COVID-19 infection rates, centered on nearby Detroit, “things are a lot better today than they were 4 weeks ago.” Dr. Vaughn helped to mobilize a team of 25 hospitalists, along with other health care professionals, who volunteered to manage COVID-19 patients in the ICU and other hospital units. Read more.

COVID-19 recommendations for rheumatic disease treatment

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) issued provisional recommendations for the management of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2. Contrary to earlier expectations, there is no indication that patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have a higher risk of contracting the virus or have a worse course if they do, according to the task force that worked on the recommendations. The task force also pointed out that rheumatology drugs are being used to treat COVID-19 patients who don’t have rheumatic diseases, raising the possibility of a shortage of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Read more.

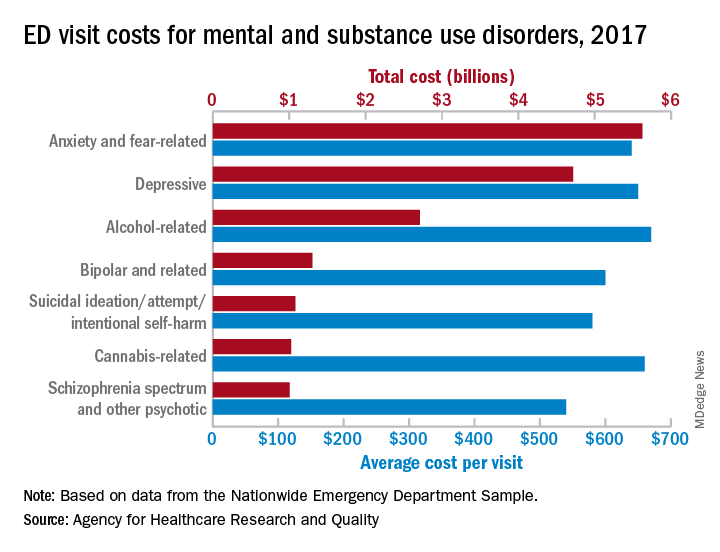

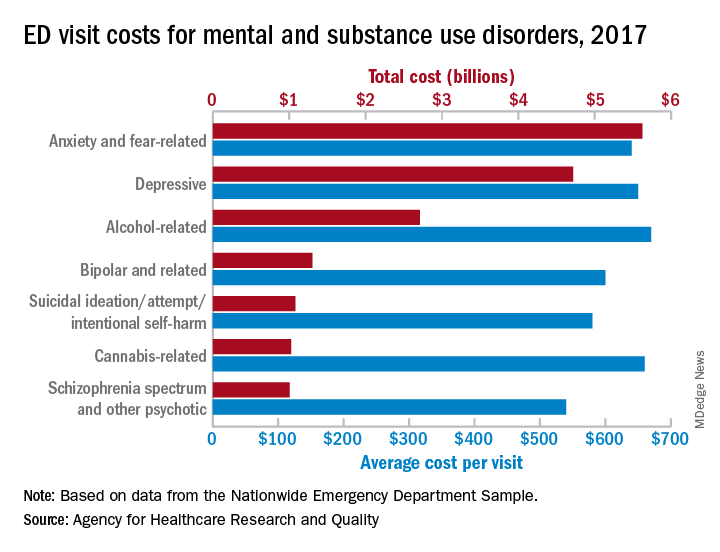

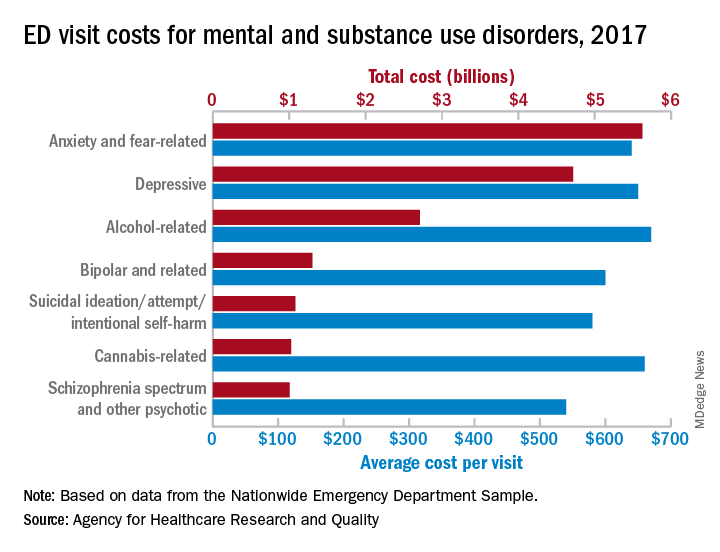

Mental health visits are 19% of ED costs

Mental and substance use disorders represented 19% of all emergency department visits in 2017 and cost $14.6 billion, according to figures from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The most costly mental and substance use disorder diagnosis was anxiety and fear-related disorders, accounting for $5.6 billion worth of visits, following by depressive disorders and alcohol-related disorders. Read more.

Food deserts linked to health issues in pregnancy

Living in a neighborhood lacking adequate access to affordable, high-quality food is associated with a somewhat greater risk of developing pregnancy morbidity, according to an observational study. Researchers found that women who lived in a food desert had a 1.6 times greater odds of pregnancy comorbidity than if they did not. “An additional, albeit less obvious factor that may be unique to patients suffering disproportionately from obstetric morbidity is exposure to toxic elements,” the researchers reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology. “It has been shown in a previous study that low-income, predominantly black communities of pregnant women may suffer disproportionately from lead or arsenic exposure.” Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

FDA seeks COVID-19 info through CURE ID

Federal health officials are asking clinicians to use the free CURE ID mobile app and web platform as a tool to collect information on the treatment of patients with COVID-19. CURE ID is an Internet-based data repository first developed in 2013 as a collaboration between the Food and Drug Administration and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health. It provides licensed clinicians worldwide with an opportunity to report novel uses of existing drugs for patients with difficult-to-treat infectious diseases, including COVID-19, through a website, a smartphone, or other mobile device. “By utilizing the CURE ID platform now for COVID-19 case collection – in conjunction with data gathered from other registries, EHR systems, and clinical trials – data collected during an outbreak can be improved and coordinated,” said Heather A. Stone, MPH, a health science policy analyst in the office of medical policy at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “This may allow us to find possible treatments to help ease this pandemic, and prepare us better to fight the next one.” Read more.

Hospitalists take on new roles in COVID era

Whether it’s working shifts in the ICU, caring for ventilator patients, or reporting to postanesthesia care units and post-acute or step-down units, hospitalists are stepping into a variety of new roles as part of their frontline response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Valerie Vaughn, MD, a hospitalist with Michigan Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, was doing research on how to reduce overuse of antibiotics in hospitals when the COVID-19 crisis hit and dramatically redefined her job. “We were afraid that we might have 3,000 to 5,000 hospitalized COVID patients by now, based on predictive modeling done while the pandemic was still growing exponentially,” she explained. Although Michigan continues to have high COVID-19 infection rates, centered on nearby Detroit, “things are a lot better today than they were 4 weeks ago.” Dr. Vaughn helped to mobilize a team of 25 hospitalists, along with other health care professionals, who volunteered to manage COVID-19 patients in the ICU and other hospital units. Read more.

COVID-19 recommendations for rheumatic disease treatment

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) issued provisional recommendations for the management of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2. Contrary to earlier expectations, there is no indication that patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have a higher risk of contracting the virus or have a worse course if they do, according to the task force that worked on the recommendations. The task force also pointed out that rheumatology drugs are being used to treat COVID-19 patients who don’t have rheumatic diseases, raising the possibility of a shortage of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Read more.

Mental health visits are 19% of ED costs

Mental and substance use disorders represented 19% of all emergency department visits in 2017 and cost $14.6 billion, according to figures from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The most costly mental and substance use disorder diagnosis was anxiety and fear-related disorders, accounting for $5.6 billion worth of visits, following by depressive disorders and alcohol-related disorders. Read more.

Food deserts linked to health issues in pregnancy

Living in a neighborhood lacking adequate access to affordable, high-quality food is associated with a somewhat greater risk of developing pregnancy morbidity, according to an observational study. Researchers found that women who lived in a food desert had a 1.6 times greater odds of pregnancy comorbidity than if they did not. “An additional, albeit less obvious factor that may be unique to patients suffering disproportionately from obstetric morbidity is exposure to toxic elements,” the researchers reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology. “It has been shown in a previous study that low-income, predominantly black communities of pregnant women may suffer disproportionately from lead or arsenic exposure.” Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

FDA seeks COVID-19 info through CURE ID

Federal health officials are asking clinicians to use the free CURE ID mobile app and web platform as a tool to collect information on the treatment of patients with COVID-19. CURE ID is an Internet-based data repository first developed in 2013 as a collaboration between the Food and Drug Administration and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health. It provides licensed clinicians worldwide with an opportunity to report novel uses of existing drugs for patients with difficult-to-treat infectious diseases, including COVID-19, through a website, a smartphone, or other mobile device. “By utilizing the CURE ID platform now for COVID-19 case collection – in conjunction with data gathered from other registries, EHR systems, and clinical trials – data collected during an outbreak can be improved and coordinated,” said Heather A. Stone, MPH, a health science policy analyst in the office of medical policy at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “This may allow us to find possible treatments to help ease this pandemic, and prepare us better to fight the next one.” Read more.

Hospitalists take on new roles in COVID era

Whether it’s working shifts in the ICU, caring for ventilator patients, or reporting to postanesthesia care units and post-acute or step-down units, hospitalists are stepping into a variety of new roles as part of their frontline response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Valerie Vaughn, MD, a hospitalist with Michigan Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, was doing research on how to reduce overuse of antibiotics in hospitals when the COVID-19 crisis hit and dramatically redefined her job. “We were afraid that we might have 3,000 to 5,000 hospitalized COVID patients by now, based on predictive modeling done while the pandemic was still growing exponentially,” she explained. Although Michigan continues to have high COVID-19 infection rates, centered on nearby Detroit, “things are a lot better today than they were 4 weeks ago.” Dr. Vaughn helped to mobilize a team of 25 hospitalists, along with other health care professionals, who volunteered to manage COVID-19 patients in the ICU and other hospital units. Read more.

COVID-19 recommendations for rheumatic disease treatment

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) issued provisional recommendations for the management of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2. Contrary to earlier expectations, there is no indication that patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have a higher risk of contracting the virus or have a worse course if they do, according to the task force that worked on the recommendations. The task force also pointed out that rheumatology drugs are being used to treat COVID-19 patients who don’t have rheumatic diseases, raising the possibility of a shortage of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Read more.

Mental health visits are 19% of ED costs

Mental and substance use disorders represented 19% of all emergency department visits in 2017 and cost $14.6 billion, according to figures from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The most costly mental and substance use disorder diagnosis was anxiety and fear-related disorders, accounting for $5.6 billion worth of visits, following by depressive disorders and alcohol-related disorders. Read more.

Food deserts linked to health issues in pregnancy

Living in a neighborhood lacking adequate access to affordable, high-quality food is associated with a somewhat greater risk of developing pregnancy morbidity, according to an observational study. Researchers found that women who lived in a food desert had a 1.6 times greater odds of pregnancy comorbidity than if they did not. “An additional, albeit less obvious factor that may be unique to patients suffering disproportionately from obstetric morbidity is exposure to toxic elements,” the researchers reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology. “It has been shown in a previous study that low-income, predominantly black communities of pregnant women may suffer disproportionately from lead or arsenic exposure.” Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Hospitalists stretch into new roles on COVID-19 front lines

‘Every single day is different’

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems, hospitals, and hospitalists – especially in hot spots like New York, Detroit, or Boston – have been challenged to stretch limits, redefine roles, and redeploy critical staff in response to rapidly changing needs on the ground.

Many hospitalists are working above and beyond their normal duties, sometimes beyond their training, specialty, or comfort zone and are rising to the occasion in ways they never imagined. These include doing shifts in ICUs, working with ventilator patients, and reporting to other atypical sites of care like postanesthesia care units and post-acute or step-down units.

Valerie Vaughn, MD, MSc, a hospitalist with Michigan Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, was doing research on how to reduce overuse of antibiotics in hospitals when the COVID-19 crisis hit and dramatically redefined her job. “We were afraid that we might have 3,000 to 5,000 hospitalized COVID patients by now, based on predictive modeling done while the pandemic was still growing exponentially,” she explained. Although Michigan continues to have high COVID-19 infection rates, centered on nearby Detroit, “things are a lot better today than they were 4 weeks ago.”

Dr. Vaughn helped to mobilize a team of 25 hospitalists, along with other health care providers, who volunteered to manage COVID-19 patients in the ICU and other hospital units. She was asked to help develop an all-COVID unit called the Regional Infectious Containment Unit or RICU, which opened March 16. Then, when the RICU became full, it was supplemented by two COVID-19 Moderate Care Units staffed by hospitalists who had “learned the ropes” in the RICU.

Both of these new models were defined in relation to the ICUs at Michigan Medicine – which were doubling in capacity, up to 200 beds at last count – and to the provision of intensive-level and long-term ventilator care for the sickest patients. The moderate care units are for patients who are not on ventilators but still very sick, for example, those receiving massive high-flow oxygen, often with a medical do-not-resuscitate/do-not-intubate order. “We established these units to do everything (medically) short of vents,” Dr. Vaughn said.

“We are having in-depth conversations about goals of care with patients soon after they arrive at the hospital. We know outcomes from ventilators are worse for COVID-positive patients who have comorbidities, and we’re using that information to inform these conversations. We’ve given scripts to clinicians to help guide them in leading these conversations. We can do other things than `use ventilators to manage their symptoms. But these are still difficult conversations,” Dr. Vaughn said.

“We also engaged palliative care early on and asked them to round with us on every [COVID] patient – until demand got too high.” The bottleneck has been the number of ICU beds available, she explained. “If you want your patient to come in and take that bed, make sure you’ve talked to the family about it.”

The COVID-19 team developed guidelines printed on pocket cards addressing critical care issues such as a refresher on how to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome and how to use vasopressors. (See the COVID-19 Continuing Medical Education Portal for web-accessible educational resources developed by Michigan Health).

It’s amazing how quickly patients can become very sick with COVID-19, Dr. Vaughn said. “One of the good things to happen from the beginning with our RICU is that a group of doctors became COVID care experts very quickly. We joined four to five hospitalists and their teams with each intensivist, so one critical care expert is there to do teaching and answer clinicians’ questions. The hospitalists coordinate the COVID care and talk to the families.”

Working on the front lines of this crisis, Dr. Vaughn said, has generated a powerful sense of purpose and camaraderie, creating bonds like in war time. “All of us on our days off feel a twinge of guilt for not being there in the hospital. The sense of gratitude we get from patients and families has been enormous, even when we were telling them bad news. That just brings us to tears.”

One of the hardest things for the doctors practicing above their typical scope of practice is that, when something bad happens, they can’t know whether it was a mistake on their part or not, she noted. “But I’ve never been so proud of our group or to be a hospitalist. No one has complained or pushed back. Everyone has responded by saying: ‘What can I do to help?’ ”

Enough work in hospital medicine

Hospitalists had not been deployed to care for ICU patients at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, a major hot spot for COVID-19, said Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at BIDMC, when he spoke to The Hospitalist in mid-May. That’s because there were plenty of hospital medicine assignments to keep them busy. Dr. Li leads a service of 120 hospitalists practicing at four hospitals.

“As we speak today, we have 300 patients with COVID, with 70 or 80 of them in our ICU. I’m taking care of 17 patients today, 15 of them COVID-positive, and the other two placed in a former radiology holding suite adapted for COVID-negative patients. Our postanesthesia care unit is now an ICU filled with COVID patients,” he said.

“Half of my day is seeing patients and the other half I’m on Zoom calls. I’m also one of the resource allocation officers for BIDMC,” Dr. Li said. He helped to create a standard of care for the hospital, addressing what to do if there weren’t enough ICU beds or ventilators. “We’ve never actualized it and probably won’t, but it was important to go through this exercise, with a lot of discussion up front.”

Haki Laho, MD, an orthopedic hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital (NEBH), also in Boston, has been redeployed to care for a different population of patients as his system tries to bunch patients. “All of a sudden – within hours and days – at the beginning of the pandemic and based on the recommendations, our whole system decided to stop all elective procedures and devote the resources to COVID,” he said.

NEBH is Beth Israel Lahey Health’s 141-bed orthopedic and surgical hospital, and the system has tried to keep the specialty facility COVID-19–free as much as possible, with the COVID-19 patients grouped together at BIDMC. Dr. Laho’s orthopedic hospitalist group, just five doctors, has been managing the influx of medical patients with multiple comorbidities – not COVID-19–infected but still a different kind of patient than they are used to.

“So far, so good. We’re dealing with it,” he said. “But if one of us got sick, the others would have to step up and do more shifts. We are physicians, internal medicine trained, but since my residency I hadn’t had to deal with these kinds of issues on a daily basis, such as setting up IV lines. I feel like I am back in residency mode.”

Convention Center medicine

Another Boston hospitalist, Amy Baughman, MD, who practices at Massachusetts General Hospital, is using her skills in a new setting, serving as a co-medical director at Boston Hope Medical Center, a 1,000-bed field hospital for patients with COVID-19. Open since April 10 and housed in the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, it is a four-way collaboration between the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the City of Boston, Partners HealthCare, and the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

Boston Hope is divided into a post-acute care section for recovering COVID-19 patients and a respite section for undomiciled patients with COVID-19 who need a place to safely quarantine. Built for a maximum of 1,000 beds, it is currently using fewer, with 83 patients on the post-acute side and 73 on the respite side as of May 12. A total of 370 and 315, respectively, had been admitted through May 12.

The team had 5 days to put the field hospital together with the help of the Army National Guard. “During that first week I was installing hand sanitizer dispensers and making [personal protective equipment] signs. Everyone here has had to do things like that,” Dr. Baughman said. “We’ve had to be incredibly creative in our staffing, using doctors from primary care and subspecialties including dermatology, radiology, and orthopedics. We had to fast-track trainings on how to use EPIC and to provide post-acute COVID care. How do you simultaneously build a medical facility and lead teams to provide high quality care?”

Dr. Baughman still works hospitalist shifts half-time at Massachusetts General. Her prior experience providing post-acute care in the VA system was helpful in creating the post-acute level of care at Boston Hope.

“My medical director role involves supervising, staffing, and scheduling. My co-medical director, Dr. Kerri Palamara, and I also supervise the clinical care,” she said. “There are a lot of systems issues, like ordering labs or prescriptions, with couriers going back and forth. And we developed clinical pathways, such as for [deep vein thrombosis] prophylaxis or for COVID retesting to determine when it is safe to end a quarantine. We’re just now rolling out virtual specialist consultations,” she noted.

“It has gone incredibly well. So much of it has been about our ability and willingness to work hard, and take feedback and go forward. We don’t have time to harp on things. We have to be very solution oriented. At the same time, honestly, it’s been fun. Every single day is different,” Dr. Baughman said.

“It’s been an opportunity to use my skills in a totally new setting, and at a level of responsibility I haven’t had before, although that’s probably a common theme with COVID-19. I was put on this team because I am a hospitalist,” she said. “I think hospitalists have been the backbone of the response to COVID in this country. It’s been an opportunity for our specialty to shine. We need to embrace the opportunity.”

Balancing expertise and supervision

Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH) in Manhattan is in the New York epicenter of the COVID-19 crisis and has mobilized large numbers of pulmonary critical care and anesthesia physicians to staff up multiple ICUs for COVID-19 patients, said Andrew Dunn, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

“My hospitalist group is covering many step-down units, medical wards, and atypical locations, providing advanced oxygen therapies, [bilevel positive airway pressure], high-flow nasal cannulas, and managing some patients on ventilators,” he said.

MSH has teaching services with house staff and nonteaching services. “We combined them into a unified service with house staff dispersed across all of the teams. We drafted a lot of nonhospitalists from different specialties to be attendings, and that has given us a tiered model, with a hospitalist supervising three or four nonhospitalist-led teams. Although the supervising hospitalists carry no patient caseloads of their own, this is primarily a clinical rather than an administrative role.”

At the peak, there were 40 rounding teams at MSH, each with a typical census of 15 patients or more, which meant that 10 supervisory hospitalists were responsible for 300 to 400 patients. “What we learned first was the need to balance the level of expertise. For example, a team may include a postgraduate year 3 resident and a radiology intern,” Dr. Dunn said. As COVID-19 census has started coming down, supervisory hospitalists are returning to direct care attending roles, and some hospitalists have been shared across the Mount Sinai system’s hospitals.

Dr. Dunn’s advice for hospitalists filling a supervisory role like this in a tiered model: Make sure you talk to your team the night before the first day of a scheduling block and try to address as many of their questions as possible. “If you wait until the morning of the shift to connect with them, anxiety will be high. But after going through a couple of scheduling cycles, we find that things are getting better. I think we’ve paid a lot of attention to the risks of burnout by our physicians. We’re using a model of 4 days on/4 off.”

Another variation on these themes is Joshua Shatzkes, MD, assistant professor of medicine and cardiology at Mount Sinai, who practices outpatient cardiology at MSH and in several off-site offices in Brooklyn. He saw early on that COVID-19 would have a huge effect on his practice, so he volunteered to help out with inpatient care. “I made it known to my chief that I was available, and I was deployed in the first week, after a weekend of cramming webinars and lectures on critical care and pulling out critical concepts that I already knew.”

Dr. Shatzkes said his career path led him into outpatient cardiology 11 years ago, where he was quickly too busy to see his patients when they went into the hospital, even though he missed hospital medicine. Working as a temporary hospitalist with the arrival of COVID-19, he has been invigorated and mobilized by the experience and reminded of why he went to medical school in the first place. “Each day’s shift went quickly but felt long. At the end of the day, I was tired but not exhausted. When I walked out of a patient’s room, they could tell, ‘This is a doctor who cared for me,’ ” he said.

After Dr. Shatzkes volunteered, he got the call from his division chief. “I was officially deployed for a 4-day shift at Mount Sinai and then as a backup.” On his first morning as an inpatient doctor, he was still getting oriented when calls started coming from the nurses. “I had five patients struggling to breathe. Their degree of hypoxia was remarkable. I kept them out of the ICU, at least for that day.”

Since then, he has continued to follow some of those patients in the hospital, along with some from his outpatient practice who were hospitalized, and others referred by colleagues, while remaining available to his outpatients through telemedicine. When this is all over, Dr. Shatzkes said, he would love to find a way to incorporate a hospital practice in his job – depending on the realities of New York traffic.

“Joshua is not a hospitalist, but he went on service and felt so fulfilled and rewarded, he asked me if he could stay on service,” Dr. Dunn said. “I also got an email from the nurse manager on the unit. They want him back.”

‘Every single day is different’

‘Every single day is different’

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems, hospitals, and hospitalists – especially in hot spots like New York, Detroit, or Boston – have been challenged to stretch limits, redefine roles, and redeploy critical staff in response to rapidly changing needs on the ground.

Many hospitalists are working above and beyond their normal duties, sometimes beyond their training, specialty, or comfort zone and are rising to the occasion in ways they never imagined. These include doing shifts in ICUs, working with ventilator patients, and reporting to other atypical sites of care like postanesthesia care units and post-acute or step-down units.

Valerie Vaughn, MD, MSc, a hospitalist with Michigan Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, was doing research on how to reduce overuse of antibiotics in hospitals when the COVID-19 crisis hit and dramatically redefined her job. “We were afraid that we might have 3,000 to 5,000 hospitalized COVID patients by now, based on predictive modeling done while the pandemic was still growing exponentially,” she explained. Although Michigan continues to have high COVID-19 infection rates, centered on nearby Detroit, “things are a lot better today than they were 4 weeks ago.”

Dr. Vaughn helped to mobilize a team of 25 hospitalists, along with other health care providers, who volunteered to manage COVID-19 patients in the ICU and other hospital units. She was asked to help develop an all-COVID unit called the Regional Infectious Containment Unit or RICU, which opened March 16. Then, when the RICU became full, it was supplemented by two COVID-19 Moderate Care Units staffed by hospitalists who had “learned the ropes” in the RICU.

Both of these new models were defined in relation to the ICUs at Michigan Medicine – which were doubling in capacity, up to 200 beds at last count – and to the provision of intensive-level and long-term ventilator care for the sickest patients. The moderate care units are for patients who are not on ventilators but still very sick, for example, those receiving massive high-flow oxygen, often with a medical do-not-resuscitate/do-not-intubate order. “We established these units to do everything (medically) short of vents,” Dr. Vaughn said.

“We are having in-depth conversations about goals of care with patients soon after they arrive at the hospital. We know outcomes from ventilators are worse for COVID-positive patients who have comorbidities, and we’re using that information to inform these conversations. We’ve given scripts to clinicians to help guide them in leading these conversations. We can do other things than `use ventilators to manage their symptoms. But these are still difficult conversations,” Dr. Vaughn said.

“We also engaged palliative care early on and asked them to round with us on every [COVID] patient – until demand got too high.” The bottleneck has been the number of ICU beds available, she explained. “If you want your patient to come in and take that bed, make sure you’ve talked to the family about it.”

The COVID-19 team developed guidelines printed on pocket cards addressing critical care issues such as a refresher on how to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome and how to use vasopressors. (See the COVID-19 Continuing Medical Education Portal for web-accessible educational resources developed by Michigan Health).

It’s amazing how quickly patients can become very sick with COVID-19, Dr. Vaughn said. “One of the good things to happen from the beginning with our RICU is that a group of doctors became COVID care experts very quickly. We joined four to five hospitalists and their teams with each intensivist, so one critical care expert is there to do teaching and answer clinicians’ questions. The hospitalists coordinate the COVID care and talk to the families.”

Working on the front lines of this crisis, Dr. Vaughn said, has generated a powerful sense of purpose and camaraderie, creating bonds like in war time. “All of us on our days off feel a twinge of guilt for not being there in the hospital. The sense of gratitude we get from patients and families has been enormous, even when we were telling them bad news. That just brings us to tears.”

One of the hardest things for the doctors practicing above their typical scope of practice is that, when something bad happens, they can’t know whether it was a mistake on their part or not, she noted. “But I’ve never been so proud of our group or to be a hospitalist. No one has complained or pushed back. Everyone has responded by saying: ‘What can I do to help?’ ”

Enough work in hospital medicine

Hospitalists had not been deployed to care for ICU patients at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, a major hot spot for COVID-19, said Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at BIDMC, when he spoke to The Hospitalist in mid-May. That’s because there were plenty of hospital medicine assignments to keep them busy. Dr. Li leads a service of 120 hospitalists practicing at four hospitals.

“As we speak today, we have 300 patients with COVID, with 70 or 80 of them in our ICU. I’m taking care of 17 patients today, 15 of them COVID-positive, and the other two placed in a former radiology holding suite adapted for COVID-negative patients. Our postanesthesia care unit is now an ICU filled with COVID patients,” he said.

“Half of my day is seeing patients and the other half I’m on Zoom calls. I’m also one of the resource allocation officers for BIDMC,” Dr. Li said. He helped to create a standard of care for the hospital, addressing what to do if there weren’t enough ICU beds or ventilators. “We’ve never actualized it and probably won’t, but it was important to go through this exercise, with a lot of discussion up front.”

Haki Laho, MD, an orthopedic hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital (NEBH), also in Boston, has been redeployed to care for a different population of patients as his system tries to bunch patients. “All of a sudden – within hours and days – at the beginning of the pandemic and based on the recommendations, our whole system decided to stop all elective procedures and devote the resources to COVID,” he said.

NEBH is Beth Israel Lahey Health’s 141-bed orthopedic and surgical hospital, and the system has tried to keep the specialty facility COVID-19–free as much as possible, with the COVID-19 patients grouped together at BIDMC. Dr. Laho’s orthopedic hospitalist group, just five doctors, has been managing the influx of medical patients with multiple comorbidities – not COVID-19–infected but still a different kind of patient than they are used to.

“So far, so good. We’re dealing with it,” he said. “But if one of us got sick, the others would have to step up and do more shifts. We are physicians, internal medicine trained, but since my residency I hadn’t had to deal with these kinds of issues on a daily basis, such as setting up IV lines. I feel like I am back in residency mode.”

Convention Center medicine

Another Boston hospitalist, Amy Baughman, MD, who practices at Massachusetts General Hospital, is using her skills in a new setting, serving as a co-medical director at Boston Hope Medical Center, a 1,000-bed field hospital for patients with COVID-19. Open since April 10 and housed in the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, it is a four-way collaboration between the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the City of Boston, Partners HealthCare, and the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

Boston Hope is divided into a post-acute care section for recovering COVID-19 patients and a respite section for undomiciled patients with COVID-19 who need a place to safely quarantine. Built for a maximum of 1,000 beds, it is currently using fewer, with 83 patients on the post-acute side and 73 on the respite side as of May 12. A total of 370 and 315, respectively, had been admitted through May 12.

The team had 5 days to put the field hospital together with the help of the Army National Guard. “During that first week I was installing hand sanitizer dispensers and making [personal protective equipment] signs. Everyone here has had to do things like that,” Dr. Baughman said. “We’ve had to be incredibly creative in our staffing, using doctors from primary care and subspecialties including dermatology, radiology, and orthopedics. We had to fast-track trainings on how to use EPIC and to provide post-acute COVID care. How do you simultaneously build a medical facility and lead teams to provide high quality care?”

Dr. Baughman still works hospitalist shifts half-time at Massachusetts General. Her prior experience providing post-acute care in the VA system was helpful in creating the post-acute level of care at Boston Hope.

“My medical director role involves supervising, staffing, and scheduling. My co-medical director, Dr. Kerri Palamara, and I also supervise the clinical care,” she said. “There are a lot of systems issues, like ordering labs or prescriptions, with couriers going back and forth. And we developed clinical pathways, such as for [deep vein thrombosis] prophylaxis or for COVID retesting to determine when it is safe to end a quarantine. We’re just now rolling out virtual specialist consultations,” she noted.

“It has gone incredibly well. So much of it has been about our ability and willingness to work hard, and take feedback and go forward. We don’t have time to harp on things. We have to be very solution oriented. At the same time, honestly, it’s been fun. Every single day is different,” Dr. Baughman said.

“It’s been an opportunity to use my skills in a totally new setting, and at a level of responsibility I haven’t had before, although that’s probably a common theme with COVID-19. I was put on this team because I am a hospitalist,” she said. “I think hospitalists have been the backbone of the response to COVID in this country. It’s been an opportunity for our specialty to shine. We need to embrace the opportunity.”

Balancing expertise and supervision

Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH) in Manhattan is in the New York epicenter of the COVID-19 crisis and has mobilized large numbers of pulmonary critical care and anesthesia physicians to staff up multiple ICUs for COVID-19 patients, said Andrew Dunn, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

“My hospitalist group is covering many step-down units, medical wards, and atypical locations, providing advanced oxygen therapies, [bilevel positive airway pressure], high-flow nasal cannulas, and managing some patients on ventilators,” he said.

MSH has teaching services with house staff and nonteaching services. “We combined them into a unified service with house staff dispersed across all of the teams. We drafted a lot of nonhospitalists from different specialties to be attendings, and that has given us a tiered model, with a hospitalist supervising three or four nonhospitalist-led teams. Although the supervising hospitalists carry no patient caseloads of their own, this is primarily a clinical rather than an administrative role.”

At the peak, there were 40 rounding teams at MSH, each with a typical census of 15 patients or more, which meant that 10 supervisory hospitalists were responsible for 300 to 400 patients. “What we learned first was the need to balance the level of expertise. For example, a team may include a postgraduate year 3 resident and a radiology intern,” Dr. Dunn said. As COVID-19 census has started coming down, supervisory hospitalists are returning to direct care attending roles, and some hospitalists have been shared across the Mount Sinai system’s hospitals.

Dr. Dunn’s advice for hospitalists filling a supervisory role like this in a tiered model: Make sure you talk to your team the night before the first day of a scheduling block and try to address as many of their questions as possible. “If you wait until the morning of the shift to connect with them, anxiety will be high. But after going through a couple of scheduling cycles, we find that things are getting better. I think we’ve paid a lot of attention to the risks of burnout by our physicians. We’re using a model of 4 days on/4 off.”

Another variation on these themes is Joshua Shatzkes, MD, assistant professor of medicine and cardiology at Mount Sinai, who practices outpatient cardiology at MSH and in several off-site offices in Brooklyn. He saw early on that COVID-19 would have a huge effect on his practice, so he volunteered to help out with inpatient care. “I made it known to my chief that I was available, and I was deployed in the first week, after a weekend of cramming webinars and lectures on critical care and pulling out critical concepts that I already knew.”

Dr. Shatzkes said his career path led him into outpatient cardiology 11 years ago, where he was quickly too busy to see his patients when they went into the hospital, even though he missed hospital medicine. Working as a temporary hospitalist with the arrival of COVID-19, he has been invigorated and mobilized by the experience and reminded of why he went to medical school in the first place. “Each day’s shift went quickly but felt long. At the end of the day, I was tired but not exhausted. When I walked out of a patient’s room, they could tell, ‘This is a doctor who cared for me,’ ” he said.

After Dr. Shatzkes volunteered, he got the call from his division chief. “I was officially deployed for a 4-day shift at Mount Sinai and then as a backup.” On his first morning as an inpatient doctor, he was still getting oriented when calls started coming from the nurses. “I had five patients struggling to breathe. Their degree of hypoxia was remarkable. I kept them out of the ICU, at least for that day.”

Since then, he has continued to follow some of those patients in the hospital, along with some from his outpatient practice who were hospitalized, and others referred by colleagues, while remaining available to his outpatients through telemedicine. When this is all over, Dr. Shatzkes said, he would love to find a way to incorporate a hospital practice in his job – depending on the realities of New York traffic.

“Joshua is not a hospitalist, but he went on service and felt so fulfilled and rewarded, he asked me if he could stay on service,” Dr. Dunn said. “I also got an email from the nurse manager on the unit. They want him back.”

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems, hospitals, and hospitalists – especially in hot spots like New York, Detroit, or Boston – have been challenged to stretch limits, redefine roles, and redeploy critical staff in response to rapidly changing needs on the ground.

Many hospitalists are working above and beyond their normal duties, sometimes beyond their training, specialty, or comfort zone and are rising to the occasion in ways they never imagined. These include doing shifts in ICUs, working with ventilator patients, and reporting to other atypical sites of care like postanesthesia care units and post-acute or step-down units.