User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

ADHD and dyslexia may affect evaluation of concussion

, a new study shows.

“Our results suggest kids with certain learning disorders may respond differently to concussion tests, and this needs to be taken into account when advising on recovery times and when they can return to sport,” said lead author Mathew Stokes, MD. Dr. Stokes is assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology/neurotherapeutics at the University of Texas–Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Sports Concussion Virtual Conference, held online July 31 to Aug. 1.

Learning disorders affected scores

The researchers analyzed data from participants aged 10-18 years who were enrolled in the North Texas Concussion Registry (ConTex). Participants had been diagnosed with a concussion that was sustained within 30 days of enrollment. The researchers investigated whether there were differences between patients who had no history of learning disorders and those with a history of dyslexia and/or ADD/ADHD with regard to results of clinical testing following concussion.

Of the 1,298 individuals in the study, 58 had been diagnosed with dyslexia, 158 had been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD, and 35 had been diagnosed with both conditions. There was no difference in age, time since injury, or history of concussion between those with learning disorders and those without, but there were more male patients in the ADD/ADHD group.

Results showed that in the dyslexia group, mean time was slower (P = .011), and there was an increase in error scores on the King-Devick (KD) test (P = .028). That test assesses eye movements and involves the rapid naming of numbers that are spaced differently. In addition, those with ADD/ADHD had significantly higher impulse control scores (P = .007) on the ImPACT series of tests, which are commonly used in the evaluation of concussion. Participants with both dyslexia and ADHD demonstrated slower KD times (P = .009) and had higher depression scores and anxiety scores.

Dr. Stokes noted that a limiting factor of the study was that baseline scores were not available. “It is possible that kids with ADD have less impulse control even at baseline, and this would need to be taken into account,” he said. “You may perhaps also expect someone with dyslexia to have a worse score on the KD tests, so we need more data on how these scores are affected from baseline in these individuals. But our results show that when evaluating kids pre- or post concussion, it is important to know about learning disorders, as this will affect how we interpret the data.”

At 3-month follow-up, there were no longer significant differences in anxiety and depression scores for those with and those without learning disorders. “This suggests anxiety and depression may well be worse temporarily after concussion for those with ADD/ADHD but gets better with time,” Dr. Stokes said.

Follow-up data were not available for the other cognitive tests.

Are recovery times longer?

Asked whether young people with these learning disorders needed a longer time to recover after concussion, Dr. Stokes said: “That is a million-dollar question. Studies so far on this have shown conflicting results. Our results add to a growing body of literature on this.” He stressed that it is important to include anxiety and depression scores on both baseline and postconcussion tests. “People don’t tend to think of these symptoms as being associated with concussion, but they are actually very prominent in this situation,” he noted. “Our results suggest that individuals with ADHD may be more prone to anxiety and depression, and a blow to the head may tip them more into these symptoms.”

Discussing the study at a virtual press conference as part of the AAN Sports Concussion meeting, the codirector of the meeting, David Dodick, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., said: “This is a very interesting and important study which suggests there are differences between adolescents with a history of dyslexia/ADHD and those without these conditions in performance in concussion tests. Understanding the differences in these groups will help health care providers in evaluating these athletes and assisting in counseling them and their families with regard to their risk of injury.

“It is important to recognize that athletes with ADHD, whether or not they are on medication, may take longer to recover from a concussion,” Dr. Dodick added. They also exhibit greater reductions in cognitive skills and visual motor speed regarding hand-eye coordination, he said. There is an increase in the severity of symptoms. “Symptoms that exist in both groups tend to more severe in those individuals with ADHD,” he noted.

“Ascertaining the presence or absence of ADHD or dyslexia in those who are participating in sport is important, especially when trying to interpret the results of baseline testing, the results of postinjury testing, decisions on when to return to play, and assessing for individuals and their families the risk of long-term repeat concussions and adverse outcomes,” he concluded.

The other codirector of the AAN meeting, Brian Hainline, MD, chief medical officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, added: “It appears that athletes with ADHD may suffer more with concussion and have a longer recovery time. This can inform our decision making and help these individuals to understand that they are at higher risk.”

Dr. Hainline said this raises another important point: “Concussion is not a homogeneous entity. It is a brain injury that can manifest in multiple parts of the brain, and the way the brain is from a premorbid or comorbid point of view can influence the manifestation of concussion as well,” he said. “All these things need to be taken into account.”

Attentional deficit may itself make an individual more susceptible to sustaining an injury in the first place, he said. “All of this is an evolving body of research which is helping clinicians to make better-informed decisions for athletes who may manifest differently.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

“Our results suggest kids with certain learning disorders may respond differently to concussion tests, and this needs to be taken into account when advising on recovery times and when they can return to sport,” said lead author Mathew Stokes, MD. Dr. Stokes is assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology/neurotherapeutics at the University of Texas–Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Sports Concussion Virtual Conference, held online July 31 to Aug. 1.

Learning disorders affected scores

The researchers analyzed data from participants aged 10-18 years who were enrolled in the North Texas Concussion Registry (ConTex). Participants had been diagnosed with a concussion that was sustained within 30 days of enrollment. The researchers investigated whether there were differences between patients who had no history of learning disorders and those with a history of dyslexia and/or ADD/ADHD with regard to results of clinical testing following concussion.

Of the 1,298 individuals in the study, 58 had been diagnosed with dyslexia, 158 had been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD, and 35 had been diagnosed with both conditions. There was no difference in age, time since injury, or history of concussion between those with learning disorders and those without, but there were more male patients in the ADD/ADHD group.

Results showed that in the dyslexia group, mean time was slower (P = .011), and there was an increase in error scores on the King-Devick (KD) test (P = .028). That test assesses eye movements and involves the rapid naming of numbers that are spaced differently. In addition, those with ADD/ADHD had significantly higher impulse control scores (P = .007) on the ImPACT series of tests, which are commonly used in the evaluation of concussion. Participants with both dyslexia and ADHD demonstrated slower KD times (P = .009) and had higher depression scores and anxiety scores.

Dr. Stokes noted that a limiting factor of the study was that baseline scores were not available. “It is possible that kids with ADD have less impulse control even at baseline, and this would need to be taken into account,” he said. “You may perhaps also expect someone with dyslexia to have a worse score on the KD tests, so we need more data on how these scores are affected from baseline in these individuals. But our results show that when evaluating kids pre- or post concussion, it is important to know about learning disorders, as this will affect how we interpret the data.”

At 3-month follow-up, there were no longer significant differences in anxiety and depression scores for those with and those without learning disorders. “This suggests anxiety and depression may well be worse temporarily after concussion for those with ADD/ADHD but gets better with time,” Dr. Stokes said.

Follow-up data were not available for the other cognitive tests.

Are recovery times longer?

Asked whether young people with these learning disorders needed a longer time to recover after concussion, Dr. Stokes said: “That is a million-dollar question. Studies so far on this have shown conflicting results. Our results add to a growing body of literature on this.” He stressed that it is important to include anxiety and depression scores on both baseline and postconcussion tests. “People don’t tend to think of these symptoms as being associated with concussion, but they are actually very prominent in this situation,” he noted. “Our results suggest that individuals with ADHD may be more prone to anxiety and depression, and a blow to the head may tip them more into these symptoms.”

Discussing the study at a virtual press conference as part of the AAN Sports Concussion meeting, the codirector of the meeting, David Dodick, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., said: “This is a very interesting and important study which suggests there are differences between adolescents with a history of dyslexia/ADHD and those without these conditions in performance in concussion tests. Understanding the differences in these groups will help health care providers in evaluating these athletes and assisting in counseling them and their families with regard to their risk of injury.

“It is important to recognize that athletes with ADHD, whether or not they are on medication, may take longer to recover from a concussion,” Dr. Dodick added. They also exhibit greater reductions in cognitive skills and visual motor speed regarding hand-eye coordination, he said. There is an increase in the severity of symptoms. “Symptoms that exist in both groups tend to more severe in those individuals with ADHD,” he noted.

“Ascertaining the presence or absence of ADHD or dyslexia in those who are participating in sport is important, especially when trying to interpret the results of baseline testing, the results of postinjury testing, decisions on when to return to play, and assessing for individuals and their families the risk of long-term repeat concussions and adverse outcomes,” he concluded.

The other codirector of the AAN meeting, Brian Hainline, MD, chief medical officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, added: “It appears that athletes with ADHD may suffer more with concussion and have a longer recovery time. This can inform our decision making and help these individuals to understand that they are at higher risk.”

Dr. Hainline said this raises another important point: “Concussion is not a homogeneous entity. It is a brain injury that can manifest in multiple parts of the brain, and the way the brain is from a premorbid or comorbid point of view can influence the manifestation of concussion as well,” he said. “All these things need to be taken into account.”

Attentional deficit may itself make an individual more susceptible to sustaining an injury in the first place, he said. “All of this is an evolving body of research which is helping clinicians to make better-informed decisions for athletes who may manifest differently.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

“Our results suggest kids with certain learning disorders may respond differently to concussion tests, and this needs to be taken into account when advising on recovery times and when they can return to sport,” said lead author Mathew Stokes, MD. Dr. Stokes is assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology/neurotherapeutics at the University of Texas–Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Sports Concussion Virtual Conference, held online July 31 to Aug. 1.

Learning disorders affected scores

The researchers analyzed data from participants aged 10-18 years who were enrolled in the North Texas Concussion Registry (ConTex). Participants had been diagnosed with a concussion that was sustained within 30 days of enrollment. The researchers investigated whether there were differences between patients who had no history of learning disorders and those with a history of dyslexia and/or ADD/ADHD with regard to results of clinical testing following concussion.

Of the 1,298 individuals in the study, 58 had been diagnosed with dyslexia, 158 had been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD, and 35 had been diagnosed with both conditions. There was no difference in age, time since injury, or history of concussion between those with learning disorders and those without, but there were more male patients in the ADD/ADHD group.

Results showed that in the dyslexia group, mean time was slower (P = .011), and there was an increase in error scores on the King-Devick (KD) test (P = .028). That test assesses eye movements and involves the rapid naming of numbers that are spaced differently. In addition, those with ADD/ADHD had significantly higher impulse control scores (P = .007) on the ImPACT series of tests, which are commonly used in the evaluation of concussion. Participants with both dyslexia and ADHD demonstrated slower KD times (P = .009) and had higher depression scores and anxiety scores.

Dr. Stokes noted that a limiting factor of the study was that baseline scores were not available. “It is possible that kids with ADD have less impulse control even at baseline, and this would need to be taken into account,” he said. “You may perhaps also expect someone with dyslexia to have a worse score on the KD tests, so we need more data on how these scores are affected from baseline in these individuals. But our results show that when evaluating kids pre- or post concussion, it is important to know about learning disorders, as this will affect how we interpret the data.”

At 3-month follow-up, there were no longer significant differences in anxiety and depression scores for those with and those without learning disorders. “This suggests anxiety and depression may well be worse temporarily after concussion for those with ADD/ADHD but gets better with time,” Dr. Stokes said.

Follow-up data were not available for the other cognitive tests.

Are recovery times longer?

Asked whether young people with these learning disorders needed a longer time to recover after concussion, Dr. Stokes said: “That is a million-dollar question. Studies so far on this have shown conflicting results. Our results add to a growing body of literature on this.” He stressed that it is important to include anxiety and depression scores on both baseline and postconcussion tests. “People don’t tend to think of these symptoms as being associated with concussion, but they are actually very prominent in this situation,” he noted. “Our results suggest that individuals with ADHD may be more prone to anxiety and depression, and a blow to the head may tip them more into these symptoms.”

Discussing the study at a virtual press conference as part of the AAN Sports Concussion meeting, the codirector of the meeting, David Dodick, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., said: “This is a very interesting and important study which suggests there are differences between adolescents with a history of dyslexia/ADHD and those without these conditions in performance in concussion tests. Understanding the differences in these groups will help health care providers in evaluating these athletes and assisting in counseling them and their families with regard to their risk of injury.

“It is important to recognize that athletes with ADHD, whether or not they are on medication, may take longer to recover from a concussion,” Dr. Dodick added. They also exhibit greater reductions in cognitive skills and visual motor speed regarding hand-eye coordination, he said. There is an increase in the severity of symptoms. “Symptoms that exist in both groups tend to more severe in those individuals with ADHD,” he noted.

“Ascertaining the presence or absence of ADHD or dyslexia in those who are participating in sport is important, especially when trying to interpret the results of baseline testing, the results of postinjury testing, decisions on when to return to play, and assessing for individuals and their families the risk of long-term repeat concussions and adverse outcomes,” he concluded.

The other codirector of the AAN meeting, Brian Hainline, MD, chief medical officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, added: “It appears that athletes with ADHD may suffer more with concussion and have a longer recovery time. This can inform our decision making and help these individuals to understand that they are at higher risk.”

Dr. Hainline said this raises another important point: “Concussion is not a homogeneous entity. It is a brain injury that can manifest in multiple parts of the brain, and the way the brain is from a premorbid or comorbid point of view can influence the manifestation of concussion as well,” he said. “All these things need to be taken into account.”

Attentional deficit may itself make an individual more susceptible to sustaining an injury in the first place, he said. “All of this is an evolving body of research which is helping clinicians to make better-informed decisions for athletes who may manifest differently.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAN Sports Concussion Conference

More evidence links gum disease and dementia risk

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

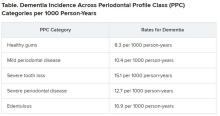

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

NBA star Mason Plumlee on COVID and life inside the Orlando ‘bubble’

Editor’s Note: This transcript from the August 20 episode of the Blood & Cancer podcast has been edited for clarity. Click this link to listen to the full episode.

David Henry, MD: Welcome to this Blood & Cancer podcast. I’m your host, Dr. David Henry. This podcast airs on Thursday morning each week. This interview and others are archived with show notes from our residents at Pennsylvania Hospital at this link.

Each week we interview key opinion leaders involved in various aspects of blood and cancer. Mason was a first round pick in the NBA, a gold medalist for the U.S. men’s national team, and NBA All-Rookie first team honoree. He’s one of the top playmaking forwards in the country, if not the world, in my opinion. In his four-year college career at Duke University, he helped lead the Blue Devils to a National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship and twice earned All-America first team academic honors at Duke. So he’s not just a basketball star, but an academic star as well. Mason, thanks so much for taking some time out from the bubble in Florida to talk with us today.

Mason Plumlee: Thanks for having me on. I’m happy to be here.

Henry: Beginning in March, the NBA didn’t know what to do about the COVID pandemic but finally decided to put you professional players in a ‘bubble.’ What did you have to go through to get there? You, your teammates, coaches, trainers, etc. And what’s the ongoing plan to be sure you continue to be safe?

Plumlee: Back to when the season shut down in March, the NBA shut down the practice facilities at the same time. Most people went home. I went back to Indiana. And then, as the idea of this bubble came up and the NBA formalized a plan to start the season again, players started to go back to market. I went back to Denver and was working out there.

About two weeks before we were scheduled to arrive in Orlando, they started testing us every other day. They used the deep nasal swab as well as the throat swab. But they were also taking two to three blood tests in that time period. You needed a certain number of consecutive negative tests before they would allow you to fly on the team plane down to Orlando. So there was an incredible amount of testing in the market. Once you got to Orlando, you went into a 48-hour quarantine. You had to have two negative tests with 48 hours between them before you could leave your hotel room.

Since then, it’s been quite strict down here. And although it’s annoying in a lot of ways, I think it’s one of the reasons our league has been able to pull this off. We’ve had no positive tests within the bubble and we are tested every day. A company called BioReference Laboratories has a setup in one of the meeting rooms here, and it’s like clockwork—we go in, we get our tests. One of my teammates missed a test and they made him stay in his room until he could get another test and get the results, so he missed a game because of that.

Henry: During this bubble time, no one has tested positive—players, coaches, staff?

Plumlee: Correct.

Henry: That’s incredible, and it’s allowed those of us who want to watch the NBA and those of you who are in it professionally to continue the sport. It must be a real nuisance for you and your family and friends, because no one can visit you, right?

Plumlee: Right. There’s no visitation. We had one false positive. It was our media relations person and the actions they took when that positive test came in -- they quarantined him in his room and interviewed everybody he had talked to; they tested anyone who had any interaction with him and those people had to go into quarantine. They’re on top of things down here. In addition to the testing, we each have a pulse oximeter and a thermometer, and we use these to check in everyday on an app. So, they’re getting all the insight they need. After the first round of the playoffs, they’re going to open the bubble to friends and family, but those friends and family will be subject to all the same protocols that we were coming in and once they’re here as well.

Henry: I’m sure you’ve heard about the Broadway star [Nick Cordero] who was healthy and suddenly got sick, lost a leg, and then lost his life. There have been some heart attacks that surprised us. Have your colleagues—players, coaches, etc.—been worried? Or are they thinking, what’s the big deal? Has the sense of how serious this is permeated through this sport?

Plumlee: The NBA is one of the groups that has heightened the understanding and awareness of this by shutting down. I think a lot of people were moving forward as is, and then, when the NBA decided to cancel the season, it let the world know, look, this is to be taken seriously.

Henry: A couple of players did test positive early on.

Plumlee: Exactly. A couple of people tested positive. I think at the outset, the unknown is always scarier. As we’ve learned more about the virus, the guys have become more comfortable. You know, I tested positive back in March. At the time, a loss of taste and smell was not a reported symptom.

Henry: And you had that?

Plumlee: I did have that, but I didn’t know what to think. More research has come out and we have a better understanding of that. I think most of the players are comfortable with the virus. We’re at a time in our lives where we’re healthy, we’re active, and we should be able to fight it off. We know the numbers for our age group. Even still, I think nobody wants to get it. Nobody wants to have to go through it. So why chance it?

Henry: Hats off to you and your sport. Other sports such as Major League Baseball haven’t been quite so successful. Of course, they’re wrestling with the players testing positive, and this has stopped games this season.

I was looking over your background prior to the interview and learned that your mother and father have been involved in the medical arena. Can you tell us about that and how it’s rubbed off on you?

Plumlee: Definitely. My mom is a pharmacist, so I spent a lot of time as a kid going to see her at work. And my dad is general counsel for an orthopedic company. My hometown is Warsaw, Ind. Some people refer to it as the “Orthopedic Capital of the World.” Zimmer Biomet is headquartered there. DePuy Synthes is there. Medtronic has offices there, as well as a lot of cottage businesses that support the orthopedic industry. In my hometown, the rock star was Dane Miller, who founded Biomet. I have no formal education in medicine or health care, but I’ve seen the impact of it. From my parents and some cousins, uncles who are doctors and surgeons, it’s been interesting to see their work and learn about what’s the latest and greatest in health care.

Henry: What’s so nice about you in particular is, with that background of interests from your family and your celebrity and accomplishments in professional basketball, you have used that to explore and promote ways to make progress in health care and help others who are less fortunate. For example, you’re involved in a telehealth platform for all-in-one practice management; affordable telehealth for pediatrics; health benefits for small businesses; prior authorization—if you can help with prior authorization, we will be in the stands for you at every game because it’s the bane of our existence; radiotherapy; and probably from mom’s background, pharmacy benefit management. Pick any of those you’d like to talk about, and tell us about your involvement and how it’s going.

Plumlee: My ticket into the arena is investment. Nobody’s calling me, asking for my expertise. But a lot of these visionary founders need financial support, and that’s where I get involved. Then also, with the celebrity angle from being an athlete, sometimes you can open doors for a start-up founder that they may not be able to open themselves.

I’m happy to speak about any of those companies. I am excited about the relaxed regulation that’s come from the pandemic; not that it’s like the Wild West out here, but I think it has allowed companies to implement solutions or think about problems in a way that they couldn’t before the pandemic. Take the prior authorization play, for example, and a company called Banjo Health, with one of my favorite founders, a guy named Saar Mahna. Medicare mandates that you turn around prior authorizations within three days. This company has an artificial intelligence and machine-learning play on prior authorizations that can deliver on that.

So efficiencies, things that increase access or affordability, better outcomes, those are the things that attract me. I lean on other people for the due diligence. The pediatric play that you referenced is a company called Blueberry Pediatrics. You have a monthly subscription for $15 that can be reimbursed by Medicaid. They send two devices to your home—an otoscope and an oximeter. The company is live in Florida right now, and it’s diverting a ton of emergency room (ER) visits. From home, for $15 a month, a mom has an otoscope and an oximeter, and she can chat or video conference with a pediatrician. There’s no additional fee. So that’s saving everyone time and saving the system money. Those are the kinds of things I’m attracted to.

Henry: You’ve touched on a couple of hot button issues for us. In oncology, unfortunately, most of our patients have pain. I am mystified every time I try to get a narcotic or a strong painkiller for a patient on a Friday night and I’m told it requires prior authorization and they’ll open up again on Monday. Well, that’s insane. These patients need something right away. So if you have a special interest in helping all of us with prior authorization, the artificial intelligence is a no brainer. If this kind of computer algorithm could happen overnight, that would be wonderful.

You mentioned the ER. Many people go to the ER as a default. They don’t know what else to do. In the COVID era, we’re trying to dial that down because we want to be able to see the sickest and have the non-sick get care elsewhere. If this particular person or people don’t know what to do, they go to the ER, it costs money, takes a lot of time, and others who may be sick are diverted from care. Families worry terribly about their children, so a device for mom and access to a pediatrician for $15 a month is another wonderful idea. These are both very interesting. Another company is in the pharmacy benefit management (PBM) space. Anything you could say about how that works?

Plumlee: I can give an overview of how I look at this as an investor in the PBM space. Three companies control about 75% of a multibillion dollar market. Several initiatives have been pursued politically to provide transparent pricing between these PBMs and pharmaceutical companies, and a lot of people are pointing fingers, but ultimately, drug prices just keep going up. Everybody knows it.

A couple of start-up founders are really set on bringing a competitive marketplace back to the pharmacy benefit manager. As an investor, when you see three people controlling a market, and you have small or medium PBMs that depend on aggregators to get competitive pricing with those big three, you get interested. It’s an interesting industry. My feeling is that somebody is going to disrupt it and bring competition back to that space. Ultimately, drug prices will come down because it’s not sustainable. The insurance companies just accommodate whatever the drug pricing is. If the drug prices go up, your premiums go up. I think these new companies will be level-setting.

Henry: In my world of oncology, we’re just a little more than halfway through 2020 and we’ve had five, six, seven new drugs approved. They all will be very expensive. One of the nicer things that’s happening and may help to tamp this down involves biosimilars. When you go to CVS or Rite Aid, you go down the aspirin aisle and see the generics, and they’re identical to the brand name aspirin. Well, these very complex molecules we used to treat cancer are antibodies or proteins, and they’re made in nature’s factories called cells. They’re not identical to the brand name drugs, but they’re called biosimilars. They work exactly the same as the branded drugs with exactly the same safety–our U.S. FDA has done a nice job of vetting that, to be sure. X, Y, Z Company has copied the brand drug after the patent expires. They were hoping for about a 30% discount in price but we’re seeing more like 15%. Nothing’s ever easy. So you make a very good point. This is not sustainable and the competition will be wonderful to tamp down these prices.

Plumlee: My hope is that those biosimilars and generics get placement in these formularies because the formularies are what’s valuable to the drug manufacturers. But they have to accommodate what the Big Three want in the PBM space. To me, making things affordable and accessible is what a lot of these startups are trying to do. And hopefully they will win.

Henry: What have you been going through, in terms of COVID? Have you recovered fully? Have your taste and smell returned, and you’re back to normal?

Plumlee: I’m all good. It caught me off guard but the symptoms weren’t too intense. For me, it was less than a flu, but more than a cold. And I’m all good today.

Henry: We’re so glad and wish you the best of luck.

Dr. Henry is a clinical professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and vice chairman of the department of medicine at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia and the host of the Blood & Cancer podcast. He has no relevant financial conflicts.

Mr. Plumlee is a board advisor to both Formsense and the Prysm Institute and a board observer with Voiceitt.

Editor’s Note: This transcript from the August 20 episode of the Blood & Cancer podcast has been edited for clarity. Click this link to listen to the full episode.

David Henry, MD: Welcome to this Blood & Cancer podcast. I’m your host, Dr. David Henry. This podcast airs on Thursday morning each week. This interview and others are archived with show notes from our residents at Pennsylvania Hospital at this link.

Each week we interview key opinion leaders involved in various aspects of blood and cancer. Mason was a first round pick in the NBA, a gold medalist for the U.S. men’s national team, and NBA All-Rookie first team honoree. He’s one of the top playmaking forwards in the country, if not the world, in my opinion. In his four-year college career at Duke University, he helped lead the Blue Devils to a National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship and twice earned All-America first team academic honors at Duke. So he’s not just a basketball star, but an academic star as well. Mason, thanks so much for taking some time out from the bubble in Florida to talk with us today.

Mason Plumlee: Thanks for having me on. I’m happy to be here.

Henry: Beginning in March, the NBA didn’t know what to do about the COVID pandemic but finally decided to put you professional players in a ‘bubble.’ What did you have to go through to get there? You, your teammates, coaches, trainers, etc. And what’s the ongoing plan to be sure you continue to be safe?

Plumlee: Back to when the season shut down in March, the NBA shut down the practice facilities at the same time. Most people went home. I went back to Indiana. And then, as the idea of this bubble came up and the NBA formalized a plan to start the season again, players started to go back to market. I went back to Denver and was working out there.

About two weeks before we were scheduled to arrive in Orlando, they started testing us every other day. They used the deep nasal swab as well as the throat swab. But they were also taking two to three blood tests in that time period. You needed a certain number of consecutive negative tests before they would allow you to fly on the team plane down to Orlando. So there was an incredible amount of testing in the market. Once you got to Orlando, you went into a 48-hour quarantine. You had to have two negative tests with 48 hours between them before you could leave your hotel room.

Since then, it’s been quite strict down here. And although it’s annoying in a lot of ways, I think it’s one of the reasons our league has been able to pull this off. We’ve had no positive tests within the bubble and we are tested every day. A company called BioReference Laboratories has a setup in one of the meeting rooms here, and it’s like clockwork—we go in, we get our tests. One of my teammates missed a test and they made him stay in his room until he could get another test and get the results, so he missed a game because of that.

Henry: During this bubble time, no one has tested positive—players, coaches, staff?

Plumlee: Correct.

Henry: That’s incredible, and it’s allowed those of us who want to watch the NBA and those of you who are in it professionally to continue the sport. It must be a real nuisance for you and your family and friends, because no one can visit you, right?

Plumlee: Right. There’s no visitation. We had one false positive. It was our media relations person and the actions they took when that positive test came in -- they quarantined him in his room and interviewed everybody he had talked to; they tested anyone who had any interaction with him and those people had to go into quarantine. They’re on top of things down here. In addition to the testing, we each have a pulse oximeter and a thermometer, and we use these to check in everyday on an app. So, they’re getting all the insight they need. After the first round of the playoffs, they’re going to open the bubble to friends and family, but those friends and family will be subject to all the same protocols that we were coming in and once they’re here as well.

Henry: I’m sure you’ve heard about the Broadway star [Nick Cordero] who was healthy and suddenly got sick, lost a leg, and then lost his life. There have been some heart attacks that surprised us. Have your colleagues—players, coaches, etc.—been worried? Or are they thinking, what’s the big deal? Has the sense of how serious this is permeated through this sport?

Plumlee: The NBA is one of the groups that has heightened the understanding and awareness of this by shutting down. I think a lot of people were moving forward as is, and then, when the NBA decided to cancel the season, it let the world know, look, this is to be taken seriously.

Henry: A couple of players did test positive early on.

Plumlee: Exactly. A couple of people tested positive. I think at the outset, the unknown is always scarier. As we’ve learned more about the virus, the guys have become more comfortable. You know, I tested positive back in March. At the time, a loss of taste and smell was not a reported symptom.

Henry: And you had that?

Plumlee: I did have that, but I didn’t know what to think. More research has come out and we have a better understanding of that. I think most of the players are comfortable with the virus. We’re at a time in our lives where we’re healthy, we’re active, and we should be able to fight it off. We know the numbers for our age group. Even still, I think nobody wants to get it. Nobody wants to have to go through it. So why chance it?

Henry: Hats off to you and your sport. Other sports such as Major League Baseball haven’t been quite so successful. Of course, they’re wrestling with the players testing positive, and this has stopped games this season.

I was looking over your background prior to the interview and learned that your mother and father have been involved in the medical arena. Can you tell us about that and how it’s rubbed off on you?

Plumlee: Definitely. My mom is a pharmacist, so I spent a lot of time as a kid going to see her at work. And my dad is general counsel for an orthopedic company. My hometown is Warsaw, Ind. Some people refer to it as the “Orthopedic Capital of the World.” Zimmer Biomet is headquartered there. DePuy Synthes is there. Medtronic has offices there, as well as a lot of cottage businesses that support the orthopedic industry. In my hometown, the rock star was Dane Miller, who founded Biomet. I have no formal education in medicine or health care, but I’ve seen the impact of it. From my parents and some cousins, uncles who are doctors and surgeons, it’s been interesting to see their work and learn about what’s the latest and greatest in health care.

Henry: What’s so nice about you in particular is, with that background of interests from your family and your celebrity and accomplishments in professional basketball, you have used that to explore and promote ways to make progress in health care and help others who are less fortunate. For example, you’re involved in a telehealth platform for all-in-one practice management; affordable telehealth for pediatrics; health benefits for small businesses; prior authorization—if you can help with prior authorization, we will be in the stands for you at every game because it’s the bane of our existence; radiotherapy; and probably from mom’s background, pharmacy benefit management. Pick any of those you’d like to talk about, and tell us about your involvement and how it’s going.

Plumlee: My ticket into the arena is investment. Nobody’s calling me, asking for my expertise. But a lot of these visionary founders need financial support, and that’s where I get involved. Then also, with the celebrity angle from being an athlete, sometimes you can open doors for a start-up founder that they may not be able to open themselves.

I’m happy to speak about any of those companies. I am excited about the relaxed regulation that’s come from the pandemic; not that it’s like the Wild West out here, but I think it has allowed companies to implement solutions or think about problems in a way that they couldn’t before the pandemic. Take the prior authorization play, for example, and a company called Banjo Health, with one of my favorite founders, a guy named Saar Mahna. Medicare mandates that you turn around prior authorizations within three days. This company has an artificial intelligence and machine-learning play on prior authorizations that can deliver on that.

So efficiencies, things that increase access or affordability, better outcomes, those are the things that attract me. I lean on other people for the due diligence. The pediatric play that you referenced is a company called Blueberry Pediatrics. You have a monthly subscription for $15 that can be reimbursed by Medicaid. They send two devices to your home—an otoscope and an oximeter. The company is live in Florida right now, and it’s diverting a ton of emergency room (ER) visits. From home, for $15 a month, a mom has an otoscope and an oximeter, and she can chat or video conference with a pediatrician. There’s no additional fee. So that’s saving everyone time and saving the system money. Those are the kinds of things I’m attracted to.

Henry: You’ve touched on a couple of hot button issues for us. In oncology, unfortunately, most of our patients have pain. I am mystified every time I try to get a narcotic or a strong painkiller for a patient on a Friday night and I’m told it requires prior authorization and they’ll open up again on Monday. Well, that’s insane. These patients need something right away. So if you have a special interest in helping all of us with prior authorization, the artificial intelligence is a no brainer. If this kind of computer algorithm could happen overnight, that would be wonderful.

You mentioned the ER. Many people go to the ER as a default. They don’t know what else to do. In the COVID era, we’re trying to dial that down because we want to be able to see the sickest and have the non-sick get care elsewhere. If this particular person or people don’t know what to do, they go to the ER, it costs money, takes a lot of time, and others who may be sick are diverted from care. Families worry terribly about their children, so a device for mom and access to a pediatrician for $15 a month is another wonderful idea. These are both very interesting. Another company is in the pharmacy benefit management (PBM) space. Anything you could say about how that works?

Plumlee: I can give an overview of how I look at this as an investor in the PBM space. Three companies control about 75% of a multibillion dollar market. Several initiatives have been pursued politically to provide transparent pricing between these PBMs and pharmaceutical companies, and a lot of people are pointing fingers, but ultimately, drug prices just keep going up. Everybody knows it.

A couple of start-up founders are really set on bringing a competitive marketplace back to the pharmacy benefit manager. As an investor, when you see three people controlling a market, and you have small or medium PBMs that depend on aggregators to get competitive pricing with those big three, you get interested. It’s an interesting industry. My feeling is that somebody is going to disrupt it and bring competition back to that space. Ultimately, drug prices will come down because it’s not sustainable. The insurance companies just accommodate whatever the drug pricing is. If the drug prices go up, your premiums go up. I think these new companies will be level-setting.

Henry: In my world of oncology, we’re just a little more than halfway through 2020 and we’ve had five, six, seven new drugs approved. They all will be very expensive. One of the nicer things that’s happening and may help to tamp this down involves biosimilars. When you go to CVS or Rite Aid, you go down the aspirin aisle and see the generics, and they’re identical to the brand name aspirin. Well, these very complex molecules we used to treat cancer are antibodies or proteins, and they’re made in nature’s factories called cells. They’re not identical to the brand name drugs, but they’re called biosimilars. They work exactly the same as the branded drugs with exactly the same safety–our U.S. FDA has done a nice job of vetting that, to be sure. X, Y, Z Company has copied the brand drug after the patent expires. They were hoping for about a 30% discount in price but we’re seeing more like 15%. Nothing’s ever easy. So you make a very good point. This is not sustainable and the competition will be wonderful to tamp down these prices.

Plumlee: My hope is that those biosimilars and generics get placement in these formularies because the formularies are what’s valuable to the drug manufacturers. But they have to accommodate what the Big Three want in the PBM space. To me, making things affordable and accessible is what a lot of these startups are trying to do. And hopefully they will win.

Henry: What have you been going through, in terms of COVID? Have you recovered fully? Have your taste and smell returned, and you’re back to normal?

Plumlee: I’m all good. It caught me off guard but the symptoms weren’t too intense. For me, it was less than a flu, but more than a cold. And I’m all good today.

Henry: We’re so glad and wish you the best of luck.

Dr. Henry is a clinical professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and vice chairman of the department of medicine at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia and the host of the Blood & Cancer podcast. He has no relevant financial conflicts.

Mr. Plumlee is a board advisor to both Formsense and the Prysm Institute and a board observer with Voiceitt.

Editor’s Note: This transcript from the August 20 episode of the Blood & Cancer podcast has been edited for clarity. Click this link to listen to the full episode.

David Henry, MD: Welcome to this Blood & Cancer podcast. I’m your host, Dr. David Henry. This podcast airs on Thursday morning each week. This interview and others are archived with show notes from our residents at Pennsylvania Hospital at this link.

Each week we interview key opinion leaders involved in various aspects of blood and cancer. Mason was a first round pick in the NBA, a gold medalist for the U.S. men’s national team, and NBA All-Rookie first team honoree. He’s one of the top playmaking forwards in the country, if not the world, in my opinion. In his four-year college career at Duke University, he helped lead the Blue Devils to a National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship and twice earned All-America first team academic honors at Duke. So he’s not just a basketball star, but an academic star as well. Mason, thanks so much for taking some time out from the bubble in Florida to talk with us today.

Mason Plumlee: Thanks for having me on. I’m happy to be here.

Henry: Beginning in March, the NBA didn’t know what to do about the COVID pandemic but finally decided to put you professional players in a ‘bubble.’ What did you have to go through to get there? You, your teammates, coaches, trainers, etc. And what’s the ongoing plan to be sure you continue to be safe?

Plumlee: Back to when the season shut down in March, the NBA shut down the practice facilities at the same time. Most people went home. I went back to Indiana. And then, as the idea of this bubble came up and the NBA formalized a plan to start the season again, players started to go back to market. I went back to Denver and was working out there.

About two weeks before we were scheduled to arrive in Orlando, they started testing us every other day. They used the deep nasal swab as well as the throat swab. But they were also taking two to three blood tests in that time period. You needed a certain number of consecutive negative tests before they would allow you to fly on the team plane down to Orlando. So there was an incredible amount of testing in the market. Once you got to Orlando, you went into a 48-hour quarantine. You had to have two negative tests with 48 hours between them before you could leave your hotel room.

Since then, it’s been quite strict down here. And although it’s annoying in a lot of ways, I think it’s one of the reasons our league has been able to pull this off. We’ve had no positive tests within the bubble and we are tested every day. A company called BioReference Laboratories has a setup in one of the meeting rooms here, and it’s like clockwork—we go in, we get our tests. One of my teammates missed a test and they made him stay in his room until he could get another test and get the results, so he missed a game because of that.

Henry: During this bubble time, no one has tested positive—players, coaches, staff?

Plumlee: Correct.

Henry: That’s incredible, and it’s allowed those of us who want to watch the NBA and those of you who are in it professionally to continue the sport. It must be a real nuisance for you and your family and friends, because no one can visit you, right?

Plumlee: Right. There’s no visitation. We had one false positive. It was our media relations person and the actions they took when that positive test came in -- they quarantined him in his room and interviewed everybody he had talked to; they tested anyone who had any interaction with him and those people had to go into quarantine. They’re on top of things down here. In addition to the testing, we each have a pulse oximeter and a thermometer, and we use these to check in everyday on an app. So, they’re getting all the insight they need. After the first round of the playoffs, they’re going to open the bubble to friends and family, but those friends and family will be subject to all the same protocols that we were coming in and once they’re here as well.

Henry: I’m sure you’ve heard about the Broadway star [Nick Cordero] who was healthy and suddenly got sick, lost a leg, and then lost his life. There have been some heart attacks that surprised us. Have your colleagues—players, coaches, etc.—been worried? Or are they thinking, what’s the big deal? Has the sense of how serious this is permeated through this sport?

Plumlee: The NBA is one of the groups that has heightened the understanding and awareness of this by shutting down. I think a lot of people were moving forward as is, and then, when the NBA decided to cancel the season, it let the world know, look, this is to be taken seriously.

Henry: A couple of players did test positive early on.

Plumlee: Exactly. A couple of people tested positive. I think at the outset, the unknown is always scarier. As we’ve learned more about the virus, the guys have become more comfortable. You know, I tested positive back in March. At the time, a loss of taste and smell was not a reported symptom.

Henry: And you had that?

Plumlee: I did have that, but I didn’t know what to think. More research has come out and we have a better understanding of that. I think most of the players are comfortable with the virus. We’re at a time in our lives where we’re healthy, we’re active, and we should be able to fight it off. We know the numbers for our age group. Even still, I think nobody wants to get it. Nobody wants to have to go through it. So why chance it?

Henry: Hats off to you and your sport. Other sports such as Major League Baseball haven’t been quite so successful. Of course, they’re wrestling with the players testing positive, and this has stopped games this season.

I was looking over your background prior to the interview and learned that your mother and father have been involved in the medical arena. Can you tell us about that and how it’s rubbed off on you?

Plumlee: Definitely. My mom is a pharmacist, so I spent a lot of time as a kid going to see her at work. And my dad is general counsel for an orthopedic company. My hometown is Warsaw, Ind. Some people refer to it as the “Orthopedic Capital of the World.” Zimmer Biomet is headquartered there. DePuy Synthes is there. Medtronic has offices there, as well as a lot of cottage businesses that support the orthopedic industry. In my hometown, the rock star was Dane Miller, who founded Biomet. I have no formal education in medicine or health care, but I’ve seen the impact of it. From my parents and some cousins, uncles who are doctors and surgeons, it’s been interesting to see their work and learn about what’s the latest and greatest in health care.

Henry: What’s so nice about you in particular is, with that background of interests from your family and your celebrity and accomplishments in professional basketball, you have used that to explore and promote ways to make progress in health care and help others who are less fortunate. For example, you’re involved in a telehealth platform for all-in-one practice management; affordable telehealth for pediatrics; health benefits for small businesses; prior authorization—if you can help with prior authorization, we will be in the stands for you at every game because it’s the bane of our existence; radiotherapy; and probably from mom’s background, pharmacy benefit management. Pick any of those you’d like to talk about, and tell us about your involvement and how it’s going.

Plumlee: My ticket into the arena is investment. Nobody’s calling me, asking for my expertise. But a lot of these visionary founders need financial support, and that’s where I get involved. Then also, with the celebrity angle from being an athlete, sometimes you can open doors for a start-up founder that they may not be able to open themselves.

I’m happy to speak about any of those companies. I am excited about the relaxed regulation that’s come from the pandemic; not that it’s like the Wild West out here, but I think it has allowed companies to implement solutions or think about problems in a way that they couldn’t before the pandemic. Take the prior authorization play, for example, and a company called Banjo Health, with one of my favorite founders, a guy named Saar Mahna. Medicare mandates that you turn around prior authorizations within three days. This company has an artificial intelligence and machine-learning play on prior authorizations that can deliver on that.

So efficiencies, things that increase access or affordability, better outcomes, those are the things that attract me. I lean on other people for the due diligence. The pediatric play that you referenced is a company called Blueberry Pediatrics. You have a monthly subscription for $15 that can be reimbursed by Medicaid. They send two devices to your home—an otoscope and an oximeter. The company is live in Florida right now, and it’s diverting a ton of emergency room (ER) visits. From home, for $15 a month, a mom has an otoscope and an oximeter, and she can chat or video conference with a pediatrician. There’s no additional fee. So that’s saving everyone time and saving the system money. Those are the kinds of things I’m attracted to.

Henry: You’ve touched on a couple of hot button issues for us. In oncology, unfortunately, most of our patients have pain. I am mystified every time I try to get a narcotic or a strong painkiller for a patient on a Friday night and I’m told it requires prior authorization and they’ll open up again on Monday. Well, that’s insane. These patients need something right away. So if you have a special interest in helping all of us with prior authorization, the artificial intelligence is a no brainer. If this kind of computer algorithm could happen overnight, that would be wonderful.

You mentioned the ER. Many people go to the ER as a default. They don’t know what else to do. In the COVID era, we’re trying to dial that down because we want to be able to see the sickest and have the non-sick get care elsewhere. If this particular person or people don’t know what to do, they go to the ER, it costs money, takes a lot of time, and others who may be sick are diverted from care. Families worry terribly about their children, so a device for mom and access to a pediatrician for $15 a month is another wonderful idea. These are both very interesting. Another company is in the pharmacy benefit management (PBM) space. Anything you could say about how that works?