User login

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

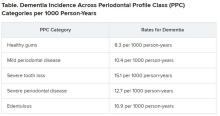

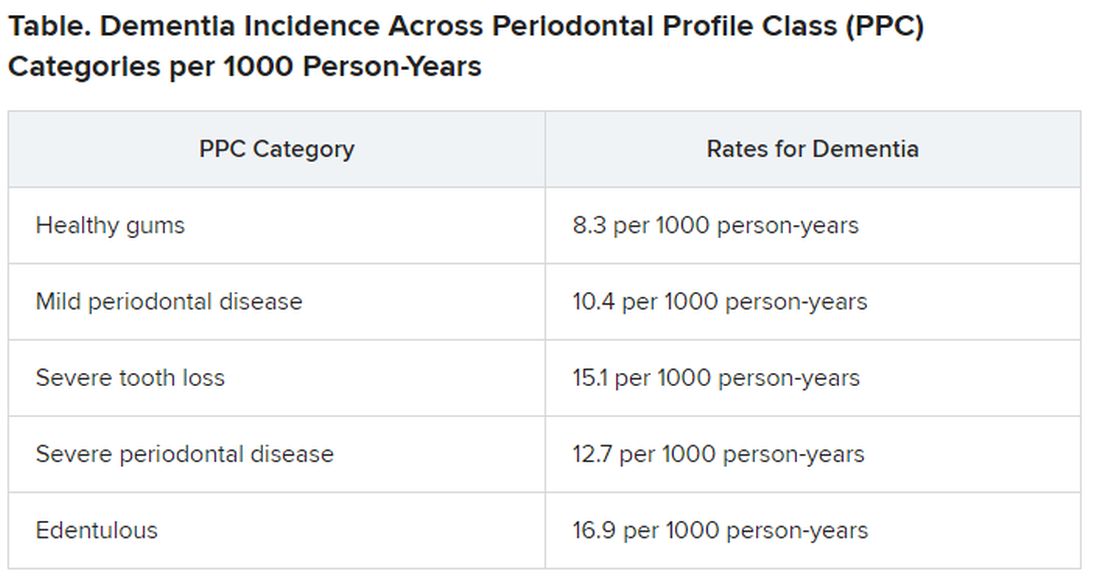

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.