User login

Clinical Endocrinology News is an independent news source that provides endocrinologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the endocrinologist's practice. Specialty topics include Diabetes, Lipid & Metabolic Disorders Menopause, Obesity, Osteoporosis, Pediatric Endocrinology, Pituitary, Thyroid & Adrenal Disorders, and Reproductive Endocrinology. Featured content includes Commentaries, Implementin Health Reform, Law & Medicine, and In the Loop, the blog of Clinical Endocrinology News. Clinical Endocrinology News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

addict

addicted

addicting

addiction

adult sites

alcohol

antibody

ass

attorney

audit

auditor

babies

babpa

baby

ban

banned

banning

best

bisexual

bitch

bleach

blog

blow job

bondage

boobs

booty

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cheap

cheapest

class action

cocaine

cock

counterfeit drug

crack

crap

crime

criminal

cunt

curable

cure

dangerous

dangers

dead

deadly

death

defend

defended

depedent

dependence

dependent

detergent

dick

die

dildo

drug abuse

drug recall

dying

fag

fake

fatal

fatalities

fatality

free

fuck

gangs

gingivitis

guns

hardcore

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

home remedies

homo

horny

hypersensitivity

hypoglycemia treatment

illegal drug use

illegal use of prescription

incest

infant

infants

job

ketoacidosis

kill

killer

killing

kinky

law suit

lawsuit

lawyer

lesbian

marijuana

medicine for hypoglycemia

murder

naked

natural

newborn

nigger

noise

nude

nudity

orgy

over the counter

overdosage

overdose

overdosed

overdosing

penis

pimp

pistol

porn

porno

pornographic

pornography

prison

profanity

purchase

purchasing

pussy

queer

rape

rapist

recall

recreational drug

rob

robberies

sale

sales

sex

sexual

shit

shoot

slut

slutty

stole

stolen

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

supply company

theft

thief

thieves

tit

toddler

toddlers

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treating dka

treating hypoglycemia

treatment for hypoglycemia

vagina

violence

whore

withdrawal

without prescription

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Triglyceride puzzle: Do TG metabolites better predict risk?

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

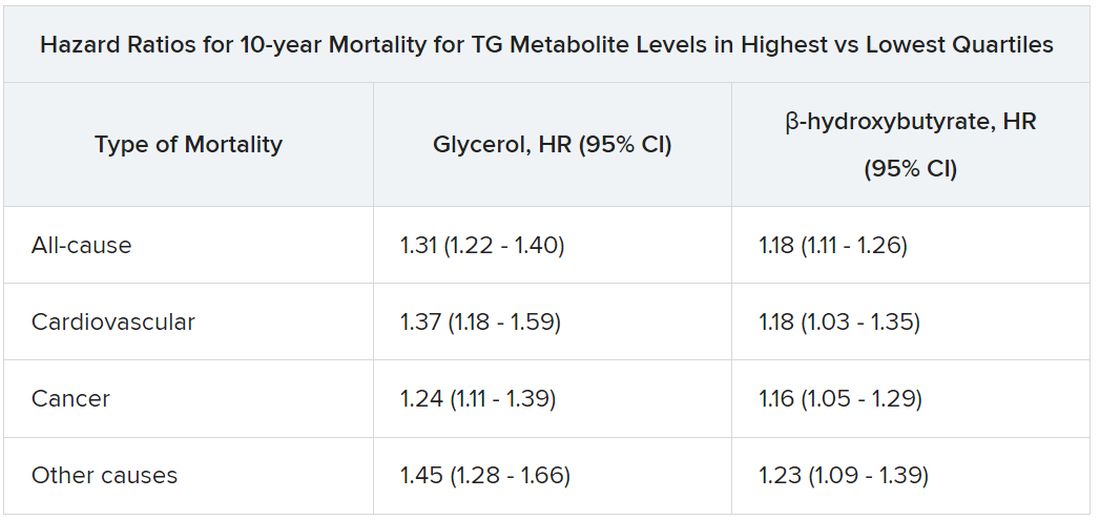

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.

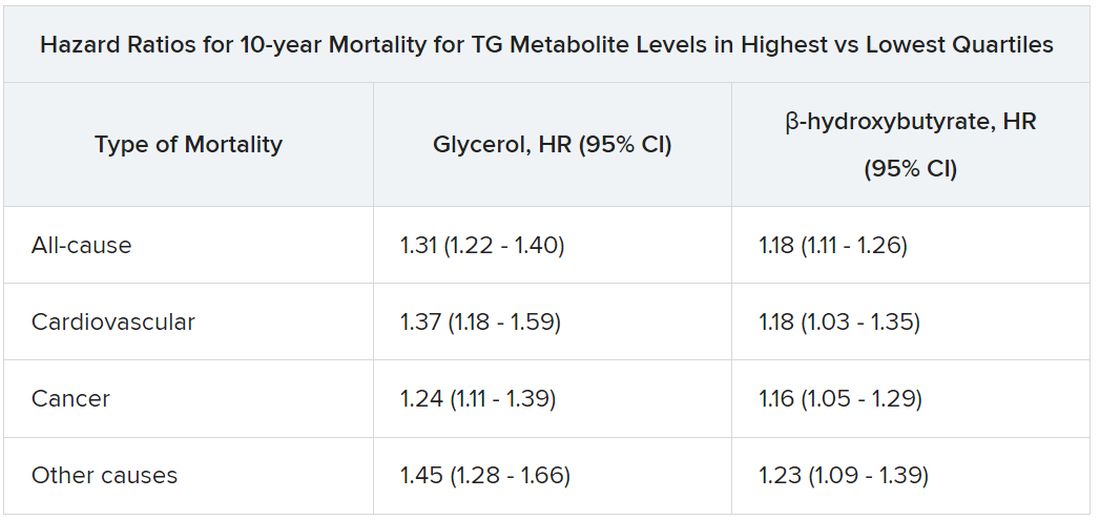

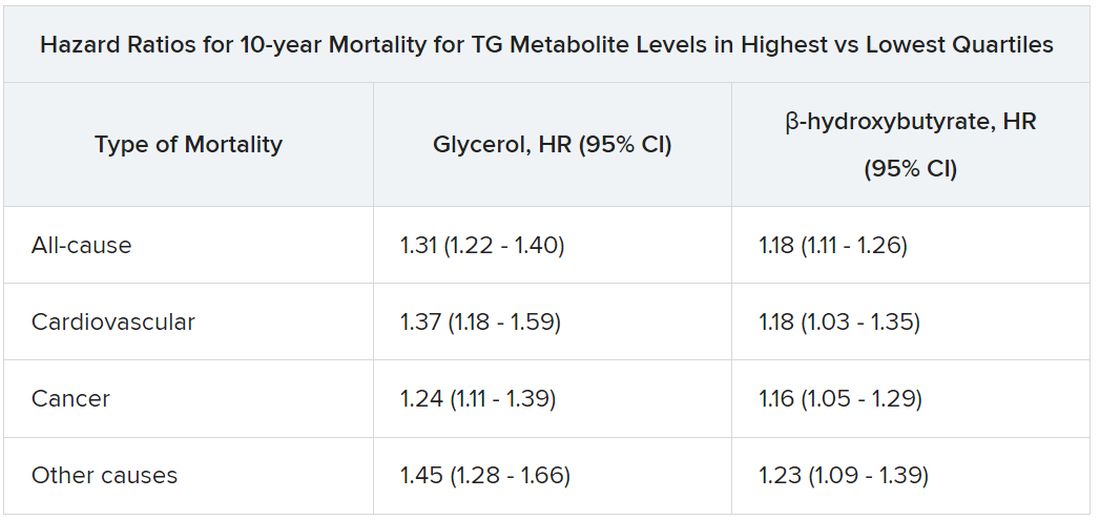

All-cause mortality jumped 31% for plasma levels of glycerol in the highest versus lowest quartiles and rose 18% for highest-quartile levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate. In parallel, CV mortality climbed 37% for glycerol and 18% for beta-hydroxybutyrate in the study, published in the European Heart Journal.

The findings “implicate triglyceride metabolic rate as a risk factor for mortality not explained by high plasma triglycerides or high BMI,” the report states. The study, it continues, may be the first to link increased mortality to more active TG metabolism – according to levels of the two biomarkers – in the general population.

The results were “really, really surprising,” senior author Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, DMSc, said in an interview. They are “completely novel” and “may make people think differently” about TG and mortality risk.

Given their unexpected findings, the group conducted further analyses for evidence that the metabolite-mortality associations weren’t independent. “We tried to stratify them away, but they stayed,” said Dr. Nordestgaard, of the University of Copenhagen.

In a weight-stratified analysis, for example, findings were similar in people with normal weight and with overweight and who were obese, Dr. Nordestgaard observed. “Even in the ones with normal weight by World Health Organization criteria, we saw the same and maybe even stronger relationships” between TG metabolism and mortality.

The study authors were is careful to note the retrospective cohort study’s limitations, but its findings “at most support an association, not causation,” Michael Miller, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, observed in an interview. Therefore, it can’t answer “whether and to what extent glycerol and/or beta-hydroxybutyrate independently contribute to mortality beyond triglyceride levels per se.”

Assessing levels of the two biomarkers “was an interesting way to indirectly assess whole-body TG metabolism,” but they were not fasting levels, said Dr. Miller, who wasn’t part of the study.

Also, the analysis doesn’t account for heparinization and other factors “that artificially raise glycerol levels” and suffers in other ways “from the inherent limitations of residual confounding,” said Dr. Miller, who is also chief of medicine at Corporal Michael J Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia.

The analysis tracked 30,000 men and women, participants in the much larger Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, for a median of 10.7 years. During that time, 9,897 of them died.

Plasma levels of glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate, the study authors noted, were measured using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Glycerol levels greater than 80 mcmol/L represented the highest quartile and those less than 52 mcmol/L the lowest quartile. The corresponding beta-hydroxybutyrate quartiles were greater than 154 mcmol/L and less than 91 mcmol/L, respectively.

Mortality risks were independent not only of BMI and TG levels but also of age, greater waist circumference, many other standard CV risk factors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, insulin use, and CV comorbidities and medications.

Dr. Nordestgaard, who also stressed that the findings are only hypothesis generating, speculated that glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting risk or guiding therapy and, indeed, might be amenable to risk-factor modification. “But I have absolutely no data to support that.”

The study was funded by the Independent Research Fund, and by Johan Boserup and Lise Boserups Grant. Dr. Nordestgaard reported consulting for or giving talks sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts. Dr. Miller disclosed serving as a scientific adviser for Amarin and 89bio.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.

All-cause mortality jumped 31% for plasma levels of glycerol in the highest versus lowest quartiles and rose 18% for highest-quartile levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate. In parallel, CV mortality climbed 37% for glycerol and 18% for beta-hydroxybutyrate in the study, published in the European Heart Journal.

The findings “implicate triglyceride metabolic rate as a risk factor for mortality not explained by high plasma triglycerides or high BMI,” the report states. The study, it continues, may be the first to link increased mortality to more active TG metabolism – according to levels of the two biomarkers – in the general population.

The results were “really, really surprising,” senior author Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, DMSc, said in an interview. They are “completely novel” and “may make people think differently” about TG and mortality risk.

Given their unexpected findings, the group conducted further analyses for evidence that the metabolite-mortality associations weren’t independent. “We tried to stratify them away, but they stayed,” said Dr. Nordestgaard, of the University of Copenhagen.

In a weight-stratified analysis, for example, findings were similar in people with normal weight and with overweight and who were obese, Dr. Nordestgaard observed. “Even in the ones with normal weight by World Health Organization criteria, we saw the same and maybe even stronger relationships” between TG metabolism and mortality.

The study authors were is careful to note the retrospective cohort study’s limitations, but its findings “at most support an association, not causation,” Michael Miller, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, observed in an interview. Therefore, it can’t answer “whether and to what extent glycerol and/or beta-hydroxybutyrate independently contribute to mortality beyond triglyceride levels per se.”

Assessing levels of the two biomarkers “was an interesting way to indirectly assess whole-body TG metabolism,” but they were not fasting levels, said Dr. Miller, who wasn’t part of the study.

Also, the analysis doesn’t account for heparinization and other factors “that artificially raise glycerol levels” and suffers in other ways “from the inherent limitations of residual confounding,” said Dr. Miller, who is also chief of medicine at Corporal Michael J Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia.

The analysis tracked 30,000 men and women, participants in the much larger Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, for a median of 10.7 years. During that time, 9,897 of them died.

Plasma levels of glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate, the study authors noted, were measured using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Glycerol levels greater than 80 mcmol/L represented the highest quartile and those less than 52 mcmol/L the lowest quartile. The corresponding beta-hydroxybutyrate quartiles were greater than 154 mcmol/L and less than 91 mcmol/L, respectively.

Mortality risks were independent not only of BMI and TG levels but also of age, greater waist circumference, many other standard CV risk factors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, insulin use, and CV comorbidities and medications.

Dr. Nordestgaard, who also stressed that the findings are only hypothesis generating, speculated that glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting risk or guiding therapy and, indeed, might be amenable to risk-factor modification. “But I have absolutely no data to support that.”

The study was funded by the Independent Research Fund, and by Johan Boserup and Lise Boserups Grant. Dr. Nordestgaard reported consulting for or giving talks sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts. Dr. Miller disclosed serving as a scientific adviser for Amarin and 89bio.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.

All-cause mortality jumped 31% for plasma levels of glycerol in the highest versus lowest quartiles and rose 18% for highest-quartile levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate. In parallel, CV mortality climbed 37% for glycerol and 18% for beta-hydroxybutyrate in the study, published in the European Heart Journal.

The findings “implicate triglyceride metabolic rate as a risk factor for mortality not explained by high plasma triglycerides or high BMI,” the report states. The study, it continues, may be the first to link increased mortality to more active TG metabolism – according to levels of the two biomarkers – in the general population.

The results were “really, really surprising,” senior author Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, DMSc, said in an interview. They are “completely novel” and “may make people think differently” about TG and mortality risk.

Given their unexpected findings, the group conducted further analyses for evidence that the metabolite-mortality associations weren’t independent. “We tried to stratify them away, but they stayed,” said Dr. Nordestgaard, of the University of Copenhagen.

In a weight-stratified analysis, for example, findings were similar in people with normal weight and with overweight and who were obese, Dr. Nordestgaard observed. “Even in the ones with normal weight by World Health Organization criteria, we saw the same and maybe even stronger relationships” between TG metabolism and mortality.

The study authors were is careful to note the retrospective cohort study’s limitations, but its findings “at most support an association, not causation,” Michael Miller, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, observed in an interview. Therefore, it can’t answer “whether and to what extent glycerol and/or beta-hydroxybutyrate independently contribute to mortality beyond triglyceride levels per se.”

Assessing levels of the two biomarkers “was an interesting way to indirectly assess whole-body TG metabolism,” but they were not fasting levels, said Dr. Miller, who wasn’t part of the study.

Also, the analysis doesn’t account for heparinization and other factors “that artificially raise glycerol levels” and suffers in other ways “from the inherent limitations of residual confounding,” said Dr. Miller, who is also chief of medicine at Corporal Michael J Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia.

The analysis tracked 30,000 men and women, participants in the much larger Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, for a median of 10.7 years. During that time, 9,897 of them died.

Plasma levels of glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate, the study authors noted, were measured using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Glycerol levels greater than 80 mcmol/L represented the highest quartile and those less than 52 mcmol/L the lowest quartile. The corresponding beta-hydroxybutyrate quartiles were greater than 154 mcmol/L and less than 91 mcmol/L, respectively.

Mortality risks were independent not only of BMI and TG levels but also of age, greater waist circumference, many other standard CV risk factors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, insulin use, and CV comorbidities and medications.

Dr. Nordestgaard, who also stressed that the findings are only hypothesis generating, speculated that glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting risk or guiding therapy and, indeed, might be amenable to risk-factor modification. “But I have absolutely no data to support that.”

The study was funded by the Independent Research Fund, and by Johan Boserup and Lise Boserups Grant. Dr. Nordestgaard reported consulting for or giving talks sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts. Dr. Miller disclosed serving as a scientific adviser for Amarin and 89bio.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

FDA approves new tubeless insulin pump

The product received CE Mark in Europe in 2018 and is now available in 19 markets worldwide. It offers users a choice of bolusing directly from the pump or from a handheld remote-control device. The pump can be detached and reattached without wasting insulin.

The remote-control device also incorporates blood glucose monitoring and bolus advice, although it currently does not integrate with continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices.

A Roche spokesperson said in an interview, “For future product generations, we are exploring possibilities to integrate CGM data into the system. Already today, the diabetes manager allows users to manually enter a glucose value that can be used to calculate a bolus. To do so, people with diabetes could use their CGM device of choice in conjunction with the Accu-Chek Solo micropump system.”

Roche will provide an update on next steps for further developments and time lines for launch “in due course,” according to a company statement.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The product received CE Mark in Europe in 2018 and is now available in 19 markets worldwide. It offers users a choice of bolusing directly from the pump or from a handheld remote-control device. The pump can be detached and reattached without wasting insulin.

The remote-control device also incorporates blood glucose monitoring and bolus advice, although it currently does not integrate with continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices.

A Roche spokesperson said in an interview, “For future product generations, we are exploring possibilities to integrate CGM data into the system. Already today, the diabetes manager allows users to manually enter a glucose value that can be used to calculate a bolus. To do so, people with diabetes could use their CGM device of choice in conjunction with the Accu-Chek Solo micropump system.”

Roche will provide an update on next steps for further developments and time lines for launch “in due course,” according to a company statement.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The product received CE Mark in Europe in 2018 and is now available in 19 markets worldwide. It offers users a choice of bolusing directly from the pump or from a handheld remote-control device. The pump can be detached and reattached without wasting insulin.

The remote-control device also incorporates blood glucose monitoring and bolus advice, although it currently does not integrate with continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices.

A Roche spokesperson said in an interview, “For future product generations, we are exploring possibilities to integrate CGM data into the system. Already today, the diabetes manager allows users to manually enter a glucose value that can be used to calculate a bolus. To do so, people with diabetes could use their CGM device of choice in conjunction with the Accu-Chek Solo micropump system.”

Roche will provide an update on next steps for further developments and time lines for launch “in due course,” according to a company statement.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Can caffeine improve thyroid function?

“Although the causal relationship between caffeine intake and thyroid function requires further verification, as an easily obtainable and widely consumed dietary ingredient, caffeine is a potential candidate for improving thyroid health in people with metabolic disorders,” reported the authors in the study, published in Nutritional Journal.

Caffeine intake, within established healthy ranges, showed a nonlinear association with thyroid levels.

Moderate caffeine intake has been associated with reducing the risk of metabolic disorders in addition to showing some mental health benefits. However, research on its effects on thyroid hormone, which importantly plays a key role in systemic metabolism and neurologic development, is lacking.

To investigate the effects, Yu Zhou, of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, School of Health, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China, and colleagues evaluated data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III 2007-2012 study involving 2,582 participants for whom data were available regarding medical conditions, dietary intake, thyroid function, and demographic background.

The participants were divided into three subgroups based on sex, age, body mass index, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and cardio-cerebral vascular disease (CVD).

Group 1 (n = 208) was the most metabolically unhealthy. Patients in that group had the highest BMI and were of oldest age. In addition, that group had higher rates of hypertension, hyperglycemia, and CVD, but, notably, it had the lowest level of caffeine consumption.

In group 2 (n = 543), all participants were current smokers, and 90.4% had a habit of drinking alcohol. That group also had the highest percentage of men.

Group 3 (n = 1,183) was the most metabolically healthy, with more women, younger age, and lowest BMI. No participants in that group had hyperglycemia, hypertension, or CVD.

Group 1, the most metabolically unhealthy, had the highest serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels. Of note, while participants with thyroid diseases were initially excluded from the analysis, higher TSH levels are predictive of subclinical hypothyroidism or progression to overt hypothyroidism.

Overall, there was no association between caffeine and TSH levels.

However, a subgroup analysis of the groups showed that in group 1, caffeine intake correlated with TSH nonlinearly (P = .0019), with minimal average consumption of caffeine (< 9.97 mg/d). There was an association with slightly higher TSH levels (P = .035) after adjustment for age, sex, race, drink, disease state, micronutrients, and macronutrients.

However, in higher, moderate amounts of caffeine consumption (9.97 – 264.97 mg/d), there was an inverse association, with lower TSH (P = .001).

There was no association between daily caffeine consumption of more than 264.97 mg and TSH levels.

For context, a typical 8-ounce cup of coffee generally contains 80-100 mg of caffeine, and the Food and Drug Administration indicates that 400 mg/d of caffeine is safe for healthy adults.

Group 2 consumed the highest amount of caffeine. Notably, that group had the lowest serum TSH levels of the three groups. There were no significant associations between caffeine consumption and TSH levels in group 2 or group 3.

There were no significant associations between caffeine consumption and levels of serum FT4 or FT3, also linked to thyroid dysfunction, in any of the groups.

The findings show that “caffeine consumption was correlated with serum TSH nonlinearly, and when taken in moderate amounts (9.97-264.97 mg/d), caffeine demonstrated a positive correlation with serum TSH levels in patients with metabolic disorders,” the authors concluded.

Mechanisms?

Caffeine is believed to modulate pituitary hormone secretion, which has been shown to influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The authors speculated that caffeine could potentially affect thyroid activity by affecting pituitary function.

“However, the effects of transient and chronic caffeine administration on human thyroid function need to be verified further, and the related mechanisms remain unclear,” they noted.

Commenting on the study, Maik Pietzner, PhD, of the Berlin Institute of Health, noted that an important limitation of the study is that various patient groups were excluded, including those with abnormal TSH levels.

“What makes me wonder is the high number of exclusions and the focus on very specific groups of people. This almost certainly introduces bias, e.g., what is specific to people not reporting coffee consumption,” Dr. Pietzner said.

Furthermore, “we already know that patients with poor metabolic health do also have slight variations in thyroid hormone levels and also have different dietary patterns,” he explained.

“So reverse confounding might occur in which the poor metabolic health is associated with both poor thyroid hormone levels and coffee consumption,” Dr. Pietzner said.

He also noted the “somewhat odd” finding that the group with the highest metabolic disorders had the lowest coffee consumption, yet the highest TSH levels.

“My guess would be that this might also be a chance finding, given that the distribution of TSH values is very skewed, which can have a strong effect in linear regression models,” Dr. Pietzner said.

In general, “the evidence generated by the study is rather weak, but there is good evidence that higher coffee consumption is linked to better metabolic health, although the exact mechanisms is not known, if indeed causal,” Dr. Pietzner added. “Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether higher coffee consumption indeed lowers the risk for thyroid disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Although the causal relationship between caffeine intake and thyroid function requires further verification, as an easily obtainable and widely consumed dietary ingredient, caffeine is a potential candidate for improving thyroid health in people with metabolic disorders,” reported the authors in the study, published in Nutritional Journal.

Caffeine intake, within established healthy ranges, showed a nonlinear association with thyroid levels.

Moderate caffeine intake has been associated with reducing the risk of metabolic disorders in addition to showing some mental health benefits. However, research on its effects on thyroid hormone, which importantly plays a key role in systemic metabolism and neurologic development, is lacking.

To investigate the effects, Yu Zhou, of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, School of Health, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China, and colleagues evaluated data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III 2007-2012 study involving 2,582 participants for whom data were available regarding medical conditions, dietary intake, thyroid function, and demographic background.

The participants were divided into three subgroups based on sex, age, body mass index, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and cardio-cerebral vascular disease (CVD).

Group 1 (n = 208) was the most metabolically unhealthy. Patients in that group had the highest BMI and were of oldest age. In addition, that group had higher rates of hypertension, hyperglycemia, and CVD, but, notably, it had the lowest level of caffeine consumption.

In group 2 (n = 543), all participants were current smokers, and 90.4% had a habit of drinking alcohol. That group also had the highest percentage of men.

Group 3 (n = 1,183) was the most metabolically healthy, with more women, younger age, and lowest BMI. No participants in that group had hyperglycemia, hypertension, or CVD.

Group 1, the most metabolically unhealthy, had the highest serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels. Of note, while participants with thyroid diseases were initially excluded from the analysis, higher TSH levels are predictive of subclinical hypothyroidism or progression to overt hypothyroidism.

Overall, there was no association between caffeine and TSH levels.

However, a subgroup analysis of the groups showed that in group 1, caffeine intake correlated with TSH nonlinearly (P = .0019), with minimal average consumption of caffeine (< 9.97 mg/d). There was an association with slightly higher TSH levels (P = .035) after adjustment for age, sex, race, drink, disease state, micronutrients, and macronutrients.

However, in higher, moderate amounts of caffeine consumption (9.97 – 264.97 mg/d), there was an inverse association, with lower TSH (P = .001).

There was no association between daily caffeine consumption of more than 264.97 mg and TSH levels.

For context, a typical 8-ounce cup of coffee generally contains 80-100 mg of caffeine, and the Food and Drug Administration indicates that 400 mg/d of caffeine is safe for healthy adults.

Group 2 consumed the highest amount of caffeine. Notably, that group had the lowest serum TSH levels of the three groups. There were no significant associations between caffeine consumption and TSH levels in group 2 or group 3.

There were no significant associations between caffeine consumption and levels of serum FT4 or FT3, also linked to thyroid dysfunction, in any of the groups.

The findings show that “caffeine consumption was correlated with serum TSH nonlinearly, and when taken in moderate amounts (9.97-264.97 mg/d), caffeine demonstrated a positive correlation with serum TSH levels in patients with metabolic disorders,” the authors concluded.

Mechanisms?

Caffeine is believed to modulate pituitary hormone secretion, which has been shown to influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The authors speculated that caffeine could potentially affect thyroid activity by affecting pituitary function.

“However, the effects of transient and chronic caffeine administration on human thyroid function need to be verified further, and the related mechanisms remain unclear,” they noted.

Commenting on the study, Maik Pietzner, PhD, of the Berlin Institute of Health, noted that an important limitation of the study is that various patient groups were excluded, including those with abnormal TSH levels.

“What makes me wonder is the high number of exclusions and the focus on very specific groups of people. This almost certainly introduces bias, e.g., what is specific to people not reporting coffee consumption,” Dr. Pietzner said.

Furthermore, “we already know that patients with poor metabolic health do also have slight variations in thyroid hormone levels and also have different dietary patterns,” he explained.

“So reverse confounding might occur in which the poor metabolic health is associated with both poor thyroid hormone levels and coffee consumption,” Dr. Pietzner said.

He also noted the “somewhat odd” finding that the group with the highest metabolic disorders had the lowest coffee consumption, yet the highest TSH levels.

“My guess would be that this might also be a chance finding, given that the distribution of TSH values is very skewed, which can have a strong effect in linear regression models,” Dr. Pietzner said.

In general, “the evidence generated by the study is rather weak, but there is good evidence that higher coffee consumption is linked to better metabolic health, although the exact mechanisms is not known, if indeed causal,” Dr. Pietzner added. “Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether higher coffee consumption indeed lowers the risk for thyroid disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Although the causal relationship between caffeine intake and thyroid function requires further verification, as an easily obtainable and widely consumed dietary ingredient, caffeine is a potential candidate for improving thyroid health in people with metabolic disorders,” reported the authors in the study, published in Nutritional Journal.

Caffeine intake, within established healthy ranges, showed a nonlinear association with thyroid levels.

Moderate caffeine intake has been associated with reducing the risk of metabolic disorders in addition to showing some mental health benefits. However, research on its effects on thyroid hormone, which importantly plays a key role in systemic metabolism and neurologic development, is lacking.

To investigate the effects, Yu Zhou, of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, School of Health, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China, and colleagues evaluated data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III 2007-2012 study involving 2,582 participants for whom data were available regarding medical conditions, dietary intake, thyroid function, and demographic background.

The participants were divided into three subgroups based on sex, age, body mass index, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and cardio-cerebral vascular disease (CVD).

Group 1 (n = 208) was the most metabolically unhealthy. Patients in that group had the highest BMI and were of oldest age. In addition, that group had higher rates of hypertension, hyperglycemia, and CVD, but, notably, it had the lowest level of caffeine consumption.

In group 2 (n = 543), all participants were current smokers, and 90.4% had a habit of drinking alcohol. That group also had the highest percentage of men.

Group 3 (n = 1,183) was the most metabolically healthy, with more women, younger age, and lowest BMI. No participants in that group had hyperglycemia, hypertension, or CVD.

Group 1, the most metabolically unhealthy, had the highest serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels. Of note, while participants with thyroid diseases were initially excluded from the analysis, higher TSH levels are predictive of subclinical hypothyroidism or progression to overt hypothyroidism.

Overall, there was no association between caffeine and TSH levels.

However, a subgroup analysis of the groups showed that in group 1, caffeine intake correlated with TSH nonlinearly (P = .0019), with minimal average consumption of caffeine (< 9.97 mg/d). There was an association with slightly higher TSH levels (P = .035) after adjustment for age, sex, race, drink, disease state, micronutrients, and macronutrients.

However, in higher, moderate amounts of caffeine consumption (9.97 – 264.97 mg/d), there was an inverse association, with lower TSH (P = .001).

There was no association between daily caffeine consumption of more than 264.97 mg and TSH levels.

For context, a typical 8-ounce cup of coffee generally contains 80-100 mg of caffeine, and the Food and Drug Administration indicates that 400 mg/d of caffeine is safe for healthy adults.

Group 2 consumed the highest amount of caffeine. Notably, that group had the lowest serum TSH levels of the three groups. There were no significant associations between caffeine consumption and TSH levels in group 2 or group 3.

There were no significant associations between caffeine consumption and levels of serum FT4 or FT3, also linked to thyroid dysfunction, in any of the groups.

The findings show that “caffeine consumption was correlated with serum TSH nonlinearly, and when taken in moderate amounts (9.97-264.97 mg/d), caffeine demonstrated a positive correlation with serum TSH levels in patients with metabolic disorders,” the authors concluded.

Mechanisms?

Caffeine is believed to modulate pituitary hormone secretion, which has been shown to influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The authors speculated that caffeine could potentially affect thyroid activity by affecting pituitary function.

“However, the effects of transient and chronic caffeine administration on human thyroid function need to be verified further, and the related mechanisms remain unclear,” they noted.

Commenting on the study, Maik Pietzner, PhD, of the Berlin Institute of Health, noted that an important limitation of the study is that various patient groups were excluded, including those with abnormal TSH levels.

“What makes me wonder is the high number of exclusions and the focus on very specific groups of people. This almost certainly introduces bias, e.g., what is specific to people not reporting coffee consumption,” Dr. Pietzner said.

Furthermore, “we already know that patients with poor metabolic health do also have slight variations in thyroid hormone levels and also have different dietary patterns,” he explained.

“So reverse confounding might occur in which the poor metabolic health is associated with both poor thyroid hormone levels and coffee consumption,” Dr. Pietzner said.

He also noted the “somewhat odd” finding that the group with the highest metabolic disorders had the lowest coffee consumption, yet the highest TSH levels.

“My guess would be that this might also be a chance finding, given that the distribution of TSH values is very skewed, which can have a strong effect in linear regression models,” Dr. Pietzner said.

In general, “the evidence generated by the study is rather weak, but there is good evidence that higher coffee consumption is linked to better metabolic health, although the exact mechanisms is not known, if indeed causal,” Dr. Pietzner added. “Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether higher coffee consumption indeed lowers the risk for thyroid disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NUTRITIONAL JOURNAL

Type 1 diabetes management improves as technology advances

Significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c have occurred over time among adults with type 1 diabetes as their use of diabetes technology has increased, yet there is still room for improvement, new data suggest.

The new findings are from a study involving patients at the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes Adult Clinic between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2021. They show that as technology use has increased, A1c levels have dropped in parallel. Moreover, progression from use of stand-alone continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) to automated insulin delivery systems (AIDs), which comprise insulin pumps and connected CGMs, furthered that progress.

The findings “are in agreement with American Diabetes Association standards of care, and recent international consensus recommending CGM and AID for most people with type 1 diabetes, and early initiation of diabetes technology from the onset of type 1 diabetes,” write Kagan E. Karakus, MD, of the University of Colorado’s Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, and colleagues in the article, which was published online in Diabetes Care.

“It’s very rewarding to us. We can see clearly that the uptake is going up and the A1c is dropping,” lead author Viral N. Shah, MD, of the Barbara Davis Center, told this news organization.

On the flip side, A1c levels rose significantly over the study period among nonusers of technology. “We cannot rule out provider bias for not prescribing diabetes technology among those with higher A1c or from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds,” Dr. Karakus and colleagues write.

Also of note, even with use of the most advanced AID systems available during the study period, just under half of patients were still not achieving A1c levels below 7%. “The technology helps, but it’s not perfect,” Dr. Shah observed.

This study is the first to examine the relationship of A1c with technology use over time, in contrast to prior cross-sectional studies. “The intention here was to look at the landscape over a decade,” Dr. Shah said.

As overall use of technology use rose, A1c levels fell

The analysis included data for 4,174 unique patients (mean number of patients, 1,988/yr); 15,903 clinic visits were included over the 8-year study period. Technology use was defined as CGM use without an AID system or with an AID system.

Over the study period, diabetes technology use increased from 26.9% to 82.7% of the clinic population (P < .001). At the same time, the overall proportion patients who achieved the A1c goal of less than 7% increased from 32.3% to 41.7%, while the mean A1c level dropped from 7.7% to 7.5% (P < .001).

But among the technology nonusers, A1c rose from 7.85% in 2014 to 8.4% in 2021 (P < .001).

Regardless of diabetes technology use, White patients (about 80% of the total study population) had significantly lower A1c than non-White patients (7.5% vs. 7.7% for technology users [P = .02]; 8.0% vs. 8.3% for nontechnology users [P < .001]).

The non-White group was too small to enable the researchers to break down the data by technology type. Nonetheless, Dr. Shah said, “As a clinician, I can say that the penetration of diabetes technology in non-White populations remains low. These are also the people more vulnerable for socioeconomic and psychosocial reasons.”

The A1c increase among technology nonusers may be a result of a statistical artifact, as the number of those individuals was much lower in 2021 than in 2014. It’s possible that those remaining individuals have exceedingly high A1c levels, bringing the average up. “It’s still not good, though,” Dr. Shah said.

The more technology, the lower the A1c

Over the study period, the proportion of stand-alone CGM users rose from 26.9% to 44.1%, while use of AIDs rose from 0% in 2014 and 2015 to 38.6% in 2021. The latter group included patients who used first-generation Medtronic 670G and 770G devices and second-generation Tandem t:slim X2 with Control-IQ devices.

Between 2017 and 2021, AIDs users had significantly lower A1c levels than nontechnology users: 7.4% vs. 8.1% in 2017, and 7.3% vs. 8.4% in 2021 (P < .001 for every year). CGM users also had significantly lower A1c levels than nonusers at all time points (P < .001 per year).

The proportions achieving an A1c less than 7% differed significantly across users of CGMs, AIDs, and no technology (P < .01 for all years). In 2021, the percentage of people who achieved an A1c less than 7% were 50.9% with AIDs and 44.1% for CGMs vs, just 15.2% with no technology.

Work to be done: Why aren’t more achieving < 7% with AIDs?

Asked why only slightly more than half of patients who used AIDs achieved A1c levels below 7%, Dr. Shah listed three possibilities:

First, the 7% goal doesn’t apply to everyone with type 1 diabetes, including those with multiple comorbidities or with short life expectancy, for whom the recommended goal is 7.5%-8.0% to prevent hypoglycemia. “We didn’t separate out patients by A1c goals. If we add that, the number might go up,” Dr. Shah said.

Second, AID technology is continually improving, but it’s not perfect. Users still must enter carbohydrate counts and signal the devices for exercise, which can lead to errors. “It’s a wonderful technology for overnight control, but still, during the daytime, there are so many factors with the user interface and how much a person is engaged with the technology,” Dr. Shah explained.

Third, he said, “Unfortunately, obesity is increasing in type 1 diabetes, and insulin doses are increasing. Higher BMI [body mass index] and more insulin resistance can mean higher A1c. I really think for many patients, we probably will need an adjunct therapy, such as an SGLT2 [sodium-glucose cotransporter-2] inhibitor or a GLP-1 [glucagonlike peptide-1] agonist, even though they’re not approved in type 1 diabetes, for both glycemic and metabolic control including weight. I think that’s another missing piece.”

He also pointed out, “If someone has an A1c of 7.5%, I don’t expect a huge change. But if they’re at 10%, a drop to 8% is a huge change.”

Overall, Dr. Shah said, the news from the study is good. “In the past, only 30% were achieving an A1c less than 7%. Now we’re 20% above that. ... It’s a glass half full.”

Dr. Karakus has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shah has received, through the University of Colorado, research support from Novo Nordisk, Insulet, Tandem Diabetes, and Dexcom, and honoraria from Medscape, Lifescan, Novo Nordisk, and DKSH Singapore for advisory board attendance and from Insulet and Dexcom for speaking engagements.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c have occurred over time among adults with type 1 diabetes as their use of diabetes technology has increased, yet there is still room for improvement, new data suggest.

The new findings are from a study involving patients at the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes Adult Clinic between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2021. They show that as technology use has increased, A1c levels have dropped in parallel. Moreover, progression from use of stand-alone continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) to automated insulin delivery systems (AIDs), which comprise insulin pumps and connected CGMs, furthered that progress.

The findings “are in agreement with American Diabetes Association standards of care, and recent international consensus recommending CGM and AID for most people with type 1 diabetes, and early initiation of diabetes technology from the onset of type 1 diabetes,” write Kagan E. Karakus, MD, of the University of Colorado’s Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, and colleagues in the article, which was published online in Diabetes Care.

“It’s very rewarding to us. We can see clearly that the uptake is going up and the A1c is dropping,” lead author Viral N. Shah, MD, of the Barbara Davis Center, told this news organization.

On the flip side, A1c levels rose significantly over the study period among nonusers of technology. “We cannot rule out provider bias for not prescribing diabetes technology among those with higher A1c or from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds,” Dr. Karakus and colleagues write.

Also of note, even with use of the most advanced AID systems available during the study period, just under half of patients were still not achieving A1c levels below 7%. “The technology helps, but it’s not perfect,” Dr. Shah observed.

This study is the first to examine the relationship of A1c with technology use over time, in contrast to prior cross-sectional studies. “The intention here was to look at the landscape over a decade,” Dr. Shah said.

As overall use of technology use rose, A1c levels fell

The analysis included data for 4,174 unique patients (mean number of patients, 1,988/yr); 15,903 clinic visits were included over the 8-year study period. Technology use was defined as CGM use without an AID system or with an AID system.

Over the study period, diabetes technology use increased from 26.9% to 82.7% of the clinic population (P < .001). At the same time, the overall proportion patients who achieved the A1c goal of less than 7% increased from 32.3% to 41.7%, while the mean A1c level dropped from 7.7% to 7.5% (P < .001).

But among the technology nonusers, A1c rose from 7.85% in 2014 to 8.4% in 2021 (P < .001).

Regardless of diabetes technology use, White patients (about 80% of the total study population) had significantly lower A1c than non-White patients (7.5% vs. 7.7% for technology users [P = .02]; 8.0% vs. 8.3% for nontechnology users [P < .001]).

The non-White group was too small to enable the researchers to break down the data by technology type. Nonetheless, Dr. Shah said, “As a clinician, I can say that the penetration of diabetes technology in non-White populations remains low. These are also the people more vulnerable for socioeconomic and psychosocial reasons.”

The A1c increase among technology nonusers may be a result of a statistical artifact, as the number of those individuals was much lower in 2021 than in 2014. It’s possible that those remaining individuals have exceedingly high A1c levels, bringing the average up. “It’s still not good, though,” Dr. Shah said.

The more technology, the lower the A1c

Over the study period, the proportion of stand-alone CGM users rose from 26.9% to 44.1%, while use of AIDs rose from 0% in 2014 and 2015 to 38.6% in 2021. The latter group included patients who used first-generation Medtronic 670G and 770G devices and second-generation Tandem t:slim X2 with Control-IQ devices.

Between 2017 and 2021, AIDs users had significantly lower A1c levels than nontechnology users: 7.4% vs. 8.1% in 2017, and 7.3% vs. 8.4% in 2021 (P < .001 for every year). CGM users also had significantly lower A1c levels than nonusers at all time points (P < .001 per year).

The proportions achieving an A1c less than 7% differed significantly across users of CGMs, AIDs, and no technology (P < .01 for all years). In 2021, the percentage of people who achieved an A1c less than 7% were 50.9% with AIDs and 44.1% for CGMs vs, just 15.2% with no technology.

Work to be done: Why aren’t more achieving < 7% with AIDs?

Asked why only slightly more than half of patients who used AIDs achieved A1c levels below 7%, Dr. Shah listed three possibilities:

First, the 7% goal doesn’t apply to everyone with type 1 diabetes, including those with multiple comorbidities or with short life expectancy, for whom the recommended goal is 7.5%-8.0% to prevent hypoglycemia. “We didn’t separate out patients by A1c goals. If we add that, the number might go up,” Dr. Shah said.

Second, AID technology is continually improving, but it’s not perfect. Users still must enter carbohydrate counts and signal the devices for exercise, which can lead to errors. “It’s a wonderful technology for overnight control, but still, during the daytime, there are so many factors with the user interface and how much a person is engaged with the technology,” Dr. Shah explained.

Third, he said, “Unfortunately, obesity is increasing in type 1 diabetes, and insulin doses are increasing. Higher BMI [body mass index] and more insulin resistance can mean higher A1c. I really think for many patients, we probably will need an adjunct therapy, such as an SGLT2 [sodium-glucose cotransporter-2] inhibitor or a GLP-1 [glucagonlike peptide-1] agonist, even though they’re not approved in type 1 diabetes, for both glycemic and metabolic control including weight. I think that’s another missing piece.”

He also pointed out, “If someone has an A1c of 7.5%, I don’t expect a huge change. But if they’re at 10%, a drop to 8% is a huge change.”

Overall, Dr. Shah said, the news from the study is good. “In the past, only 30% were achieving an A1c less than 7%. Now we’re 20% above that. ... It’s a glass half full.”

Dr. Karakus has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shah has received, through the University of Colorado, research support from Novo Nordisk, Insulet, Tandem Diabetes, and Dexcom, and honoraria from Medscape, Lifescan, Novo Nordisk, and DKSH Singapore for advisory board attendance and from Insulet and Dexcom for speaking engagements.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c have occurred over time among adults with type 1 diabetes as their use of diabetes technology has increased, yet there is still room for improvement, new data suggest.

The new findings are from a study involving patients at the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes Adult Clinic between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2021. They show that as technology use has increased, A1c levels have dropped in parallel. Moreover, progression from use of stand-alone continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) to automated insulin delivery systems (AIDs), which comprise insulin pumps and connected CGMs, furthered that progress.

The findings “are in agreement with American Diabetes Association standards of care, and recent international consensus recommending CGM and AID for most people with type 1 diabetes, and early initiation of diabetes technology from the onset of type 1 diabetes,” write Kagan E. Karakus, MD, of the University of Colorado’s Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, and colleagues in the article, which was published online in Diabetes Care.

“It’s very rewarding to us. We can see clearly that the uptake is going up and the A1c is dropping,” lead author Viral N. Shah, MD, of the Barbara Davis Center, told this news organization.

On the flip side, A1c levels rose significantly over the study period among nonusers of technology. “We cannot rule out provider bias for not prescribing diabetes technology among those with higher A1c or from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds,” Dr. Karakus and colleagues write.

Also of note, even with use of the most advanced AID systems available during the study period, just under half of patients were still not achieving A1c levels below 7%. “The technology helps, but it’s not perfect,” Dr. Shah observed.

This study is the first to examine the relationship of A1c with technology use over time, in contrast to prior cross-sectional studies. “The intention here was to look at the landscape over a decade,” Dr. Shah said.

As overall use of technology use rose, A1c levels fell

The analysis included data for 4,174 unique patients (mean number of patients, 1,988/yr); 15,903 clinic visits were included over the 8-year study period. Technology use was defined as CGM use without an AID system or with an AID system.

Over the study period, diabetes technology use increased from 26.9% to 82.7% of the clinic population (P < .001). At the same time, the overall proportion patients who achieved the A1c goal of less than 7% increased from 32.3% to 41.7%, while the mean A1c level dropped from 7.7% to 7.5% (P < .001).

But among the technology nonusers, A1c rose from 7.85% in 2014 to 8.4% in 2021 (P < .001).

Regardless of diabetes technology use, White patients (about 80% of the total study population) had significantly lower A1c than non-White patients (7.5% vs. 7.7% for technology users [P = .02]; 8.0% vs. 8.3% for nontechnology users [P < .001]).

The non-White group was too small to enable the researchers to break down the data by technology type. Nonetheless, Dr. Shah said, “As a clinician, I can say that the penetration of diabetes technology in non-White populations remains low. These are also the people more vulnerable for socioeconomic and psychosocial reasons.”

The A1c increase among technology nonusers may be a result of a statistical artifact, as the number of those individuals was much lower in 2021 than in 2014. It’s possible that those remaining individuals have exceedingly high A1c levels, bringing the average up. “It’s still not good, though,” Dr. Shah said.

The more technology, the lower the A1c

Over the study period, the proportion of stand-alone CGM users rose from 26.9% to 44.1%, while use of AIDs rose from 0% in 2014 and 2015 to 38.6% in 2021. The latter group included patients who used first-generation Medtronic 670G and 770G devices and second-generation Tandem t:slim X2 with Control-IQ devices.

Between 2017 and 2021, AIDs users had significantly lower A1c levels than nontechnology users: 7.4% vs. 8.1% in 2017, and 7.3% vs. 8.4% in 2021 (P < .001 for every year). CGM users also had significantly lower A1c levels than nonusers at all time points (P < .001 per year).

The proportions achieving an A1c less than 7% differed significantly across users of CGMs, AIDs, and no technology (P < .01 for all years). In 2021, the percentage of people who achieved an A1c less than 7% were 50.9% with AIDs and 44.1% for CGMs vs, just 15.2% with no technology.

Work to be done: Why aren’t more achieving < 7% with AIDs?

Asked why only slightly more than half of patients who used AIDs achieved A1c levels below 7%, Dr. Shah listed three possibilities:

First, the 7% goal doesn’t apply to everyone with type 1 diabetes, including those with multiple comorbidities or with short life expectancy, for whom the recommended goal is 7.5%-8.0% to prevent hypoglycemia. “We didn’t separate out patients by A1c goals. If we add that, the number might go up,” Dr. Shah said.

Second, AID technology is continually improving, but it’s not perfect. Users still must enter carbohydrate counts and signal the devices for exercise, which can lead to errors. “It’s a wonderful technology for overnight control, but still, during the daytime, there are so many factors with the user interface and how much a person is engaged with the technology,” Dr. Shah explained.

Third, he said, “Unfortunately, obesity is increasing in type 1 diabetes, and insulin doses are increasing. Higher BMI [body mass index] and more insulin resistance can mean higher A1c. I really think for many patients, we probably will need an adjunct therapy, such as an SGLT2 [sodium-glucose cotransporter-2] inhibitor or a GLP-1 [glucagonlike peptide-1] agonist, even though they’re not approved in type 1 diabetes, for both glycemic and metabolic control including weight. I think that’s another missing piece.”

He also pointed out, “If someone has an A1c of 7.5%, I don’t expect a huge change. But if they’re at 10%, a drop to 8% is a huge change.”

Overall, Dr. Shah said, the news from the study is good. “In the past, only 30% were achieving an A1c less than 7%. Now we’re 20% above that. ... It’s a glass half full.”

Dr. Karakus has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shah has received, through the University of Colorado, research support from Novo Nordisk, Insulet, Tandem Diabetes, and Dexcom, and honoraria from Medscape, Lifescan, Novo Nordisk, and DKSH Singapore for advisory board attendance and from Insulet and Dexcom for speaking engagements.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Artificial sweeteners no help for weight loss: Review

It also shows evidence that these products are not beneficial for controlling excess weight.

Francisco Gómez-Delgado, MD, PhD, and Pablo Pérez-Martínez, MD, PhD, are members of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis and of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. They have coordinated an updated review of the leading scientific evidence surrounding artificial sweeteners: evidence showing that far from positively affecting our health, they have “negative effects for the cardiometabolic system.”

The paper, published in Current Opinion in Cardiology, delves into the consumption of these sweeteners and their negative influence on the development of obesity and of several of the most important cardiometabolic risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes).

Globalization and the increase in consumption of ultraprocessed foods have led to a need for greater knowledge on the health impacts of certain nutrients such as artificial sweeteners (nutritive and nonnutritive). This review aims to analyze their role and their effect on cardiometabolic and cardiovascular disease risk.

Cardiovascular risk

The detrimental effects of a high-calorie, high-sugar diet have been well established. For this reason, health authorities recommend limiting sugar consumption. The recommendation has led the food industry to develop different artificial sweeteners with specific properties, such as flavor and stability (nutritive artificial sweeteners), and others aimed at limiting sugar in the diet (nonnutritive artificial sweeteners). Recent evidence explores the influence of these two types of artificial sweeteners on cardiovascular disease risk through risk factors such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, among others.

Initially, the consumption of artificial sweeteners was presented as an alternative for reducing calorie intake in the diet as an option for people with excess weight and obesity. However, as this paper explains, the consumption of these artificial sweeteners favors weight gain because of neuroendocrine mechanisms related to satiety that are abnormally activated when artificial sweeteners are consumed.

Weight gain

On the other hand, evidence shows that consuming artificial sweeteners does not encourage weight loss. “Quite the contrary,” Dr. Pérez-Martínez, scientific director at the Maimonides Biomedical Research Institute and internist at the University Hospital Reina Sofia, both in Córdoba, told this news organization. “There is evidence showing weight gain resulting from the effect that artificial sweetener consumption has at the neurohormonal level by altering the mechanisms involved in regulating the feeling of satiety.”

However, on the basis of current evidence, sugar cannot be claimed to be less harmful. “What we do know is that in both cases, we should reduce or remove them from our diets and replace them with other healthier alternatives for weight management, such as eating plant-based products or being physically active.”

Confronting ignorance

Nonetheless, these recommendations are conditional, “because the weight of the evidence is not extremely high, since there have not been a whole lot of studies. All nutritional studies must be viewed with caution,” Manuel Anguita, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Anguita is department head of clinical cardiology at the University Hospital Reina Sofia in Córdoba and past president of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

“It’s something that should be included within the medical record when you’re assessing cardiovascular risk. In addition to identifying patients who use artificial sweeteners, it’s especially important to emphasize that it’s not an appropriate recommendation for weight management.” Healthier measures include moderate exercise and the Mediterranean diet.

Explaining why this research is valuable, he said, “It’s generally useful because there’s ignorance not only in the population but among physicians as well [about] these negative effects of sweeteners.”

Diabetes and metabolic syndrome

Artificial sweeteners cause significant disruptions in the endocrine system, leading our metabolism to function abnormally. The review revealed that consuming artificial sweeteners raises the risk for type 2 diabetes by between 18% and 24% and raises the risk for metabolic syndrome by up to 44%.

Dr. Gómez-Delgado, an internal medicine specialist at the University Hospital of Jaen in Spain and first author of the study, discussed the deleterious effects of sweeteners on metabolism. “On one hand, neurohormonal disorders impact appetite, and the feeling of satiety is abnormally delayed.” On the other hand, “they induce excessive insulin secretion in the pancreas,” which in the long run, encourages metabolic disorders that lead to diabetes. Ultimately, this process produces what we know as “dysbiosis, since our microbiota is unable to process these artificial sweeteners.” Dysbiosis triggers specific pathophysiologic processes that negatively affect cardiometabolic and cardiovascular systems.

No differences

Regarding the type of sweetener, Dr. Gómez-Delgado noted that currently available studies assess the consumption of special dietary products that, in most cases, include various types of artificial sweeteners. “So, it’s not possible to define specific differences between them as to how they impact our health.” Additional studies are needed to confirm this effect at the cardiometabolic level and to analyze the different types of artificial sweeteners individually.

“There’s enough evidence to confirm that consuming artificial sweeteners negatively interferes with our metabolism – especially glucose metabolism – and increases the risk of developing diabetes,” said Dr. Gómez-Delgado.

High-sodium drinks

When it comes to the influence of artificial sweeteners on hypertension, “there is no single explanation. The World Health Organization already discussed this issue 4-5 years ago, not only due to their carcinogenic risk, but also due to this cardiovascular risk in terms of a lack of control of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension,” said Dr. Anguita.

Another important point “is that this is not in reference to the sweeteners themselves, but to soft drinks containing those components, which is where we have more studies,” he added. There are two factors explaining this increase in hypertension, which poses a problem at the population level, with medium- to long-term follow-up. “The sugary beverages that we mentioned have a higher sodium content. That is, the sweeteners add this element, which is a factor that’s directly linked to the increase in blood pressure levels.” Another factor that can influence blood pressure is “the increase in insulin secretion that has been described as resulting from sweeteners. In the medium and long term, this is associated with increased blood pressure levels.”

Cardiovascular risk factor?

Are artificial sweeteners considered to be a new cardiovascular risk factor? “What they really do is increase the incidence of the other classic risk factors,” including obesity, said Dr. Anguita. It has been shown that artificial sweeteners don’t reduce obesity when used continuously. Nonetheless, “there is still not enough evidence to view it in the same light as the classic risk factors,” added Dr. Anguita. However, it is a factor that can clearly worsen the control of the other factors. Therefore, “it’s appropriate to sound an alarm and explain that it’s not the best way to lose weight; there are many other healthier choices.”

“We need more robust evidence to take a clear position on the use of this type of sweetener and its detrimental effect on health. Meanwhile, it would be ideal to limit their consumption or even avoid adding artificial sweeteners to coffee or teas,” added Dr. Pérez-Martínez.

Regulate consumption

Dr. Pérez-Martínez mentioned that the measures proposed to regulate the consumption of artificial sweeteners and to modify the current legislation must involve “minimizing the consumption of these special dietary products as much as possible and even avoiding adding these artificial sweeteners to the foods that we consume; for example, to coffee and tea.” On the other hand, “we must provide consumers with information that is as clear and simple as possible regarding the composition of the food they consume and how it impacts their health.”

However, “we need more evidence to be able to take a clear position on what type of sweeteners we can consume in our diet and also to what extent we should limit their presence in the foods we consume,” said Dr. Pérez-Martínez.

Last, “most of the evidence is from short-term observational studies that assess frequencies and patterns of consumption of foods containing these artificial sweeteners.” Of course, “we need studies that specifically analyze their effects at the metabolic level as well as longer-term studies where the nutritional follow-up of participants is more accurate and rigorous, especially when it comes to the consumption of this type of food,” concluded Dr. Gómez-Delgado.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

It also shows evidence that these products are not beneficial for controlling excess weight.

Francisco Gómez-Delgado, MD, PhD, and Pablo Pérez-Martínez, MD, PhD, are members of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis and of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. They have coordinated an updated review of the leading scientific evidence surrounding artificial sweeteners: evidence showing that far from positively affecting our health, they have “negative effects for the cardiometabolic system.”

The paper, published in Current Opinion in Cardiology, delves into the consumption of these sweeteners and their negative influence on the development of obesity and of several of the most important cardiometabolic risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes).

Globalization and the increase in consumption of ultraprocessed foods have led to a need for greater knowledge on the health impacts of certain nutrients such as artificial sweeteners (nutritive and nonnutritive). This review aims to analyze their role and their effect on cardiometabolic and cardiovascular disease risk.

Cardiovascular risk

The detrimental effects of a high-calorie, high-sugar diet have been well established. For this reason, health authorities recommend limiting sugar consumption. The recommendation has led the food industry to develop different artificial sweeteners with specific properties, such as flavor and stability (nutritive artificial sweeteners), and others aimed at limiting sugar in the diet (nonnutritive artificial sweeteners). Recent evidence explores the influence of these two types of artificial sweeteners on cardiovascular disease risk through risk factors such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, among others.

Initially, the consumption of artificial sweeteners was presented as an alternative for reducing calorie intake in the diet as an option for people with excess weight and obesity. However, as this paper explains, the consumption of these artificial sweeteners favors weight gain because of neuroendocrine mechanisms related to satiety that are abnormally activated when artificial sweeteners are consumed.

Weight gain

On the other hand, evidence shows that consuming artificial sweeteners does not encourage weight loss. “Quite the contrary,” Dr. Pérez-Martínez, scientific director at the Maimonides Biomedical Research Institute and internist at the University Hospital Reina Sofia, both in Córdoba, told this news organization. “There is evidence showing weight gain resulting from the effect that artificial sweetener consumption has at the neurohormonal level by altering the mechanisms involved in regulating the feeling of satiety.”

However, on the basis of current evidence, sugar cannot be claimed to be less harmful. “What we do know is that in both cases, we should reduce or remove them from our diets and replace them with other healthier alternatives for weight management, such as eating plant-based products or being physically active.”

Confronting ignorance

Nonetheless, these recommendations are conditional, “because the weight of the evidence is not extremely high, since there have not been a whole lot of studies. All nutritional studies must be viewed with caution,” Manuel Anguita, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Anguita is department head of clinical cardiology at the University Hospital Reina Sofia in Córdoba and past president of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

“It’s something that should be included within the medical record when you’re assessing cardiovascular risk. In addition to identifying patients who use artificial sweeteners, it’s especially important to emphasize that it’s not an appropriate recommendation for weight management.” Healthier measures include moderate exercise and the Mediterranean diet.

Explaining why this research is valuable, he said, “It’s generally useful because there’s ignorance not only in the population but among physicians as well [about] these negative effects of sweeteners.”

Diabetes and metabolic syndrome

Artificial sweeteners cause significant disruptions in the endocrine system, leading our metabolism to function abnormally. The review revealed that consuming artificial sweeteners raises the risk for type 2 diabetes by between 18% and 24% and raises the risk for metabolic syndrome by up to 44%.

Dr. Gómez-Delgado, an internal medicine specialist at the University Hospital of Jaen in Spain and first author of the study, discussed the deleterious effects of sweeteners on metabolism. “On one hand, neurohormonal disorders impact appetite, and the feeling of satiety is abnormally delayed.” On the other hand, “they induce excessive insulin secretion in the pancreas,” which in the long run, encourages metabolic disorders that lead to diabetes. Ultimately, this process produces what we know as “dysbiosis, since our microbiota is unable to process these artificial sweeteners.” Dysbiosis triggers specific pathophysiologic processes that negatively affect cardiometabolic and cardiovascular systems.

No differences

Regarding the type of sweetener, Dr. Gómez-Delgado noted that currently available studies assess the consumption of special dietary products that, in most cases, include various types of artificial sweeteners. “So, it’s not possible to define specific differences between them as to how they impact our health.” Additional studies are needed to confirm this effect at the cardiometabolic level and to analyze the different types of artificial sweeteners individually.

“There’s enough evidence to confirm that consuming artificial sweeteners negatively interferes with our metabolism – especially glucose metabolism – and increases the risk of developing diabetes,” said Dr. Gómez-Delgado.

High-sodium drinks

When it comes to the influence of artificial sweeteners on hypertension, “there is no single explanation. The World Health Organization already discussed this issue 4-5 years ago, not only due to their carcinogenic risk, but also due to this cardiovascular risk in terms of a lack of control of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension,” said Dr. Anguita.

Another important point “is that this is not in reference to the sweeteners themselves, but to soft drinks containing those components, which is where we have more studies,” he added. There are two factors explaining this increase in hypertension, which poses a problem at the population level, with medium- to long-term follow-up. “The sugary beverages that we mentioned have a higher sodium content. That is, the sweeteners add this element, which is a factor that’s directly linked to the increase in blood pressure levels.” Another factor that can influence blood pressure is “the increase in insulin secretion that has been described as resulting from sweeteners. In the medium and long term, this is associated with increased blood pressure levels.”

Cardiovascular risk factor?

Are artificial sweeteners considered to be a new cardiovascular risk factor? “What they really do is increase the incidence of the other classic risk factors,” including obesity, said Dr. Anguita. It has been shown that artificial sweeteners don’t reduce obesity when used continuously. Nonetheless, “there is still not enough evidence to view it in the same light as the classic risk factors,” added Dr. Anguita. However, it is a factor that can clearly worsen the control of the other factors. Therefore, “it’s appropriate to sound an alarm and explain that it’s not the best way to lose weight; there are many other healthier choices.”

“We need more robust evidence to take a clear position on the use of this type of sweetener and its detrimental effect on health. Meanwhile, it would be ideal to limit their consumption or even avoid adding artificial sweeteners to coffee or teas,” added Dr. Pérez-Martínez.

Regulate consumption

Dr. Pérez-Martínez mentioned that the measures proposed to regulate the consumption of artificial sweeteners and to modify the current legislation must involve “minimizing the consumption of these special dietary products as much as possible and even avoiding adding these artificial sweeteners to the foods that we consume; for example, to coffee and tea.” On the other hand, “we must provide consumers with information that is as clear and simple as possible regarding the composition of the food they consume and how it impacts their health.”

However, “we need more evidence to be able to take a clear position on what type of sweeteners we can consume in our diet and also to what extent we should limit their presence in the foods we consume,” said Dr. Pérez-Martínez.

Last, “most of the evidence is from short-term observational studies that assess frequencies and patterns of consumption of foods containing these artificial sweeteners.” Of course, “we need studies that specifically analyze their effects at the metabolic level as well as longer-term studies where the nutritional follow-up of participants is more accurate and rigorous, especially when it comes to the consumption of this type of food,” concluded Dr. Gómez-Delgado.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

It also shows evidence that these products are not beneficial for controlling excess weight.

Francisco Gómez-Delgado, MD, PhD, and Pablo Pérez-Martínez, MD, PhD, are members of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis and of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine. They have coordinated an updated review of the leading scientific evidence surrounding artificial sweeteners: evidence showing that far from positively affecting our health, they have “negative effects for the cardiometabolic system.”

The paper, published in Current Opinion in Cardiology, delves into the consumption of these sweeteners and their negative influence on the development of obesity and of several of the most important cardiometabolic risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes).

Globalization and the increase in consumption of ultraprocessed foods have led to a need for greater knowledge on the health impacts of certain nutrients such as artificial sweeteners (nutritive and nonnutritive). This review aims to analyze their role and their effect on cardiometabolic and cardiovascular disease risk.

Cardiovascular risk

The detrimental effects of a high-calorie, high-sugar diet have been well established. For this reason, health authorities recommend limiting sugar consumption. The recommendation has led the food industry to develop different artificial sweeteners with specific properties, such as flavor and stability (nutritive artificial sweeteners), and others aimed at limiting sugar in the diet (nonnutritive artificial sweeteners). Recent evidence explores the influence of these two types of artificial sweeteners on cardiovascular disease risk through risk factors such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, among others.