User login

Clinical Endocrinology News is an independent news source that provides endocrinologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the endocrinologist's practice. Specialty topics include Diabetes, Lipid & Metabolic Disorders Menopause, Obesity, Osteoporosis, Pediatric Endocrinology, Pituitary, Thyroid & Adrenal Disorders, and Reproductive Endocrinology. Featured content includes Commentaries, Implementin Health Reform, Law & Medicine, and In the Loop, the blog of Clinical Endocrinology News. Clinical Endocrinology News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

addict

addicted

addicting

addiction

adult sites

alcohol

antibody

ass

attorney

audit

auditor

babies

babpa

baby

ban

banned

banning

best

bisexual

bitch

bleach

blog

blow job

bondage

boobs

booty

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cheap

cheapest

class action

cocaine

cock

counterfeit drug

crack

crap

crime

criminal

cunt

curable

cure

dangerous

dangers

dead

deadly

death

defend

defended

depedent

dependence

dependent

detergent

dick

die

dildo

drug abuse

drug recall

dying

fag

fake

fatal

fatalities

fatality

free

fuck

gangs

gingivitis

guns

hardcore

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

home remedies

homo

horny

hypersensitivity

hypoglycemia treatment

illegal drug use

illegal use of prescription

incest

infant

infants

job

ketoacidosis

kill

killer

killing

kinky

law suit

lawsuit

lawyer

lesbian

marijuana

medicine for hypoglycemia

murder

naked

natural

newborn

nigger

noise

nude

nudity

orgy

over the counter

overdosage

overdose

overdosed

overdosing

penis

pimp

pistol

porn

porno

pornographic

pornography

prison

profanity

purchase

purchasing

pussy

queer

rape

rapist

recall

recreational drug

rob

robberies

sale

sales

sex

sexual

shit

shoot

slut

slutty

stole

stolen

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

supply company

theft

thief

thieves

tit

toddler

toddlers

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treating dka

treating hypoglycemia

treatment for hypoglycemia

vagina

violence

whore

withdrawal

without prescription

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

How much do we really know about gender dysphoria?

At the risk of losing a digit or two I am going to dip my toes into the murky waters of gender-affirming care, sometimes referred to as trans care. Recently, Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, released two statements, one in the Aug. 22, 2022, Wall Street Journal, the other summarized in the Aug. 25, 2022, AAP Daily Briefing, in which she attempts to clarify the academy’s position on gender-affirming care. They were well-worded and heroic attempts to clear the air. I fear these explanations will do little to encourage informed and courteous discussions between those entrenched on either side of a disagreement that is unfortunately being played out on media outlets and state legislatures instead of the offices of primary care physicians and specialists where it belongs.

The current mess is an example of what can happen when there is a paucity of reliable data, a superabundance of emotion, and a system that feeds on instant news and sound bites with little understanding of how science should work.

Some of the turmoil is a response to the notion that in certain situations gender dysphoria may be a condition that can be learned or mimicked from exposure to other gender-dysphoric individuals. Two papers anchor either side of the debate. The first paper was published in 2018 by a then–Brown University health expert who hypothesized the existence of a condition which she labeled “rapid-onset gender dysphoria [ROGD]”. One can imagine that “social contagion” might be considered as one of the potential contributors to this hypothesized condition. Unfortunately, the publication of the paper ignited a firestorm of criticism from a segment of the population that advocates for the transgender community, prompting the university and the online publisher to backpedal and reevaluate the quality of the research on which the paper was based.

One of the concerns voiced at the time of publication was that the research could be used to support the transphobic agenda by some state legislatures hoping to ban gender-affirming care. How large a role the paper played in the current spate of legislation in is unclear. I suspect it has been small. But, one can’t deny the potential exists.

Leaping forward to 2022, the second paper was published in the August issue of Pediatrics, in which the authors attempted to test the ROGD hypothesis and question the inference of social contagion.

The investigators found that in 2017 and 2019 the birth ratios of transgender-diverse (TGD) individuals did not favor assigned female-sex-at-birth (AFAB) individuals. They also discovered that in their sample overall there was a decrease in the percentage of adolescents who self-identified as TGD. Not surprisingly, “bullying victimization and suicidality were higher among TGD youth when compared with their cisgender peers.” The authors concluded that their findings were “incongruent with an ROGD hypothesis that posits social contagion” nor should it be used to restrict access to gender-affirming care.

There you have it. Are we any closer to understanding gender dysphoria and its origins? I don’t think so. The media is somewhat less confused. The NBC News online presence headline on Aug. 3, 2022, reads “‘Social contagion’ isn’t causing more youths to be transgender, study finds.”

My sense is that the general population perceives an increase in the prevalence of gender dysphoria. It is very likely that this perception is primarily a reflection of a more compassionate and educated attitude in a significant portion of the population making it less challenging for gender-dysphoric youth to surface. However, it should not surprise us that some parents and observers are concerned that a percentage of this increased prevalence is the result of social contagion. Nor should it surprise us that some advocates for the trans population feel threatened by this hypothesis.

Neither of these studies really answers the question of whether some cases of gender dysphoria are the result of social contagion. Both were small samples using methodology that has been called into question. The bottom line is that we need more studies and must remain open to considering their results. That’s how science should work.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

At the risk of losing a digit or two I am going to dip my toes into the murky waters of gender-affirming care, sometimes referred to as trans care. Recently, Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, released two statements, one in the Aug. 22, 2022, Wall Street Journal, the other summarized in the Aug. 25, 2022, AAP Daily Briefing, in which she attempts to clarify the academy’s position on gender-affirming care. They were well-worded and heroic attempts to clear the air. I fear these explanations will do little to encourage informed and courteous discussions between those entrenched on either side of a disagreement that is unfortunately being played out on media outlets and state legislatures instead of the offices of primary care physicians and specialists where it belongs.

The current mess is an example of what can happen when there is a paucity of reliable data, a superabundance of emotion, and a system that feeds on instant news and sound bites with little understanding of how science should work.

Some of the turmoil is a response to the notion that in certain situations gender dysphoria may be a condition that can be learned or mimicked from exposure to other gender-dysphoric individuals. Two papers anchor either side of the debate. The first paper was published in 2018 by a then–Brown University health expert who hypothesized the existence of a condition which she labeled “rapid-onset gender dysphoria [ROGD]”. One can imagine that “social contagion” might be considered as one of the potential contributors to this hypothesized condition. Unfortunately, the publication of the paper ignited a firestorm of criticism from a segment of the population that advocates for the transgender community, prompting the university and the online publisher to backpedal and reevaluate the quality of the research on which the paper was based.

One of the concerns voiced at the time of publication was that the research could be used to support the transphobic agenda by some state legislatures hoping to ban gender-affirming care. How large a role the paper played in the current spate of legislation in is unclear. I suspect it has been small. But, one can’t deny the potential exists.

Leaping forward to 2022, the second paper was published in the August issue of Pediatrics, in which the authors attempted to test the ROGD hypothesis and question the inference of social contagion.

The investigators found that in 2017 and 2019 the birth ratios of transgender-diverse (TGD) individuals did not favor assigned female-sex-at-birth (AFAB) individuals. They also discovered that in their sample overall there was a decrease in the percentage of adolescents who self-identified as TGD. Not surprisingly, “bullying victimization and suicidality were higher among TGD youth when compared with their cisgender peers.” The authors concluded that their findings were “incongruent with an ROGD hypothesis that posits social contagion” nor should it be used to restrict access to gender-affirming care.

There you have it. Are we any closer to understanding gender dysphoria and its origins? I don’t think so. The media is somewhat less confused. The NBC News online presence headline on Aug. 3, 2022, reads “‘Social contagion’ isn’t causing more youths to be transgender, study finds.”

My sense is that the general population perceives an increase in the prevalence of gender dysphoria. It is very likely that this perception is primarily a reflection of a more compassionate and educated attitude in a significant portion of the population making it less challenging for gender-dysphoric youth to surface. However, it should not surprise us that some parents and observers are concerned that a percentage of this increased prevalence is the result of social contagion. Nor should it surprise us that some advocates for the trans population feel threatened by this hypothesis.

Neither of these studies really answers the question of whether some cases of gender dysphoria are the result of social contagion. Both were small samples using methodology that has been called into question. The bottom line is that we need more studies and must remain open to considering their results. That’s how science should work.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

At the risk of losing a digit or two I am going to dip my toes into the murky waters of gender-affirming care, sometimes referred to as trans care. Recently, Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, released two statements, one in the Aug. 22, 2022, Wall Street Journal, the other summarized in the Aug. 25, 2022, AAP Daily Briefing, in which she attempts to clarify the academy’s position on gender-affirming care. They were well-worded and heroic attempts to clear the air. I fear these explanations will do little to encourage informed and courteous discussions between those entrenched on either side of a disagreement that is unfortunately being played out on media outlets and state legislatures instead of the offices of primary care physicians and specialists where it belongs.

The current mess is an example of what can happen when there is a paucity of reliable data, a superabundance of emotion, and a system that feeds on instant news and sound bites with little understanding of how science should work.

Some of the turmoil is a response to the notion that in certain situations gender dysphoria may be a condition that can be learned or mimicked from exposure to other gender-dysphoric individuals. Two papers anchor either side of the debate. The first paper was published in 2018 by a then–Brown University health expert who hypothesized the existence of a condition which she labeled “rapid-onset gender dysphoria [ROGD]”. One can imagine that “social contagion” might be considered as one of the potential contributors to this hypothesized condition. Unfortunately, the publication of the paper ignited a firestorm of criticism from a segment of the population that advocates for the transgender community, prompting the university and the online publisher to backpedal and reevaluate the quality of the research on which the paper was based.

One of the concerns voiced at the time of publication was that the research could be used to support the transphobic agenda by some state legislatures hoping to ban gender-affirming care. How large a role the paper played in the current spate of legislation in is unclear. I suspect it has been small. But, one can’t deny the potential exists.

Leaping forward to 2022, the second paper was published in the August issue of Pediatrics, in which the authors attempted to test the ROGD hypothesis and question the inference of social contagion.

The investigators found that in 2017 and 2019 the birth ratios of transgender-diverse (TGD) individuals did not favor assigned female-sex-at-birth (AFAB) individuals. They also discovered that in their sample overall there was a decrease in the percentage of adolescents who self-identified as TGD. Not surprisingly, “bullying victimization and suicidality were higher among TGD youth when compared with their cisgender peers.” The authors concluded that their findings were “incongruent with an ROGD hypothesis that posits social contagion” nor should it be used to restrict access to gender-affirming care.

There you have it. Are we any closer to understanding gender dysphoria and its origins? I don’t think so. The media is somewhat less confused. The NBC News online presence headline on Aug. 3, 2022, reads “‘Social contagion’ isn’t causing more youths to be transgender, study finds.”

My sense is that the general population perceives an increase in the prevalence of gender dysphoria. It is very likely that this perception is primarily a reflection of a more compassionate and educated attitude in a significant portion of the population making it less challenging for gender-dysphoric youth to surface. However, it should not surprise us that some parents and observers are concerned that a percentage of this increased prevalence is the result of social contagion. Nor should it surprise us that some advocates for the trans population feel threatened by this hypothesis.

Neither of these studies really answers the question of whether some cases of gender dysphoria are the result of social contagion. Both were small samples using methodology that has been called into question. The bottom line is that we need more studies and must remain open to considering their results. That’s how science should work.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: Are they protective?

New research is suggesting that there are “meaningful” associations between higher dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids and lower risk for depressive episodes.

In addition, consumption of total fatty acids and alpha-linolenic acid was associated with a reduced risk for incident depressive episodes (9% and 29%, respectively).

“Our results showed an important protective effect from the consumption of omega-3,” Maria de Jesus Mendes da Fonseca, University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, and colleagues write.

The findings were published online in Nutrients.

Mixed bag of studies

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that deficient dietary omega-3 intake is a modifiable risk factor for depression and that individuals with low consumption of omega-3 food sources have more depressive symptoms.

However, the results are inconsistent, and few longitudinal studies have addressed this association, the investigators note.

The new analysis included 13,879 adults (aged 39-65 years or older) participating in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) from 2008 to 2014.

Data on depressive episodes were obtained with the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), and food consumption was measured with the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

The target dietary components were total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and the omega-3 fatty acids: alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

The majority of participants had adequate dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and none was taking omega-3 supplements.

In the fully adjusted model, consumption of fatty acids from the omega-3 family had a protective effect against maintenance of depressive episodes, showing “important associations, although the significance levels are borderline, possibly due to the sample size,” the researchers report.

In regard to onset of depressive episodes, estimates from the fully adjusted model suggest that a higher consumption of omega-3 acids (total and subtypes) is associated with lower risk for depressive episodes – with significant associations for omega-3 and alpha-linolenic acid.

The investigators note that strengths of the study include “its originality, as it is the first to assess associations between maintenance and incidence of depressive episodes and consumption of omega-3, besides the use of data from the ELSA-Brasil Study, with rigorous data collection protocols and reliable and validated instruments, thus guaranteeing the quality of the sample and the data.”

A study limitation, however, was that the ELSA-Brasil sample consists only of public employees, with the potential for a selection bias such as healthy worker phenomenon, the researchers note. Another was the use of the FFQ, which may underestimate daily intake of foods and depends on individual participant recall – all of which could possibly lead to a differential classification bias.

Interpret cautiously

Commenting on the study, David Mischoulon, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, and director of the depression clinical and research program at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said that data on omega-3s in depression are “very mixed.”

“A lot of the studies don’t necessarily agree with each other. Certainly, in studies that try to seek an association between omega-3 use and depression, it’s always complicated because it can be difficult to control for all variables that could be contributing to the result that you get,” said Dr. Mischoulon, who is also a member of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and was not involved in the research.

A caveat to the current study was that diet was assessed only at baseline, “so we don’t really know whether there were any substantial dietary changes over time, he noted.

He also cautioned that it is hard to draw any firm conclusions from this type of study.

“In general, in studies with a large sample, which this study has, it’s easier to find statistically significant differences. But you need to ask yourself: Does it really matter? Is it enough to have a clinical impact and make a difference?” Dr. Mischoulon said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and by the Ministry of Health. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals and heckel medizintechnik GmbH and honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. He also works with the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute, which has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies and the National Institute of Mental Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research is suggesting that there are “meaningful” associations between higher dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids and lower risk for depressive episodes.

In addition, consumption of total fatty acids and alpha-linolenic acid was associated with a reduced risk for incident depressive episodes (9% and 29%, respectively).

“Our results showed an important protective effect from the consumption of omega-3,” Maria de Jesus Mendes da Fonseca, University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, and colleagues write.

The findings were published online in Nutrients.

Mixed bag of studies

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that deficient dietary omega-3 intake is a modifiable risk factor for depression and that individuals with low consumption of omega-3 food sources have more depressive symptoms.

However, the results are inconsistent, and few longitudinal studies have addressed this association, the investigators note.

The new analysis included 13,879 adults (aged 39-65 years or older) participating in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) from 2008 to 2014.

Data on depressive episodes were obtained with the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), and food consumption was measured with the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

The target dietary components were total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and the omega-3 fatty acids: alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

The majority of participants had adequate dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and none was taking omega-3 supplements.

In the fully adjusted model, consumption of fatty acids from the omega-3 family had a protective effect against maintenance of depressive episodes, showing “important associations, although the significance levels are borderline, possibly due to the sample size,” the researchers report.

In regard to onset of depressive episodes, estimates from the fully adjusted model suggest that a higher consumption of omega-3 acids (total and subtypes) is associated with lower risk for depressive episodes – with significant associations for omega-3 and alpha-linolenic acid.

The investigators note that strengths of the study include “its originality, as it is the first to assess associations between maintenance and incidence of depressive episodes and consumption of omega-3, besides the use of data from the ELSA-Brasil Study, with rigorous data collection protocols and reliable and validated instruments, thus guaranteeing the quality of the sample and the data.”

A study limitation, however, was that the ELSA-Brasil sample consists only of public employees, with the potential for a selection bias such as healthy worker phenomenon, the researchers note. Another was the use of the FFQ, which may underestimate daily intake of foods and depends on individual participant recall – all of which could possibly lead to a differential classification bias.

Interpret cautiously

Commenting on the study, David Mischoulon, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, and director of the depression clinical and research program at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said that data on omega-3s in depression are “very mixed.”

“A lot of the studies don’t necessarily agree with each other. Certainly, in studies that try to seek an association between omega-3 use and depression, it’s always complicated because it can be difficult to control for all variables that could be contributing to the result that you get,” said Dr. Mischoulon, who is also a member of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and was not involved in the research.

A caveat to the current study was that diet was assessed only at baseline, “so we don’t really know whether there were any substantial dietary changes over time, he noted.

He also cautioned that it is hard to draw any firm conclusions from this type of study.

“In general, in studies with a large sample, which this study has, it’s easier to find statistically significant differences. But you need to ask yourself: Does it really matter? Is it enough to have a clinical impact and make a difference?” Dr. Mischoulon said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and by the Ministry of Health. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals and heckel medizintechnik GmbH and honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. He also works with the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute, which has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies and the National Institute of Mental Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research is suggesting that there are “meaningful” associations between higher dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids and lower risk for depressive episodes.

In addition, consumption of total fatty acids and alpha-linolenic acid was associated with a reduced risk for incident depressive episodes (9% and 29%, respectively).

“Our results showed an important protective effect from the consumption of omega-3,” Maria de Jesus Mendes da Fonseca, University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, and colleagues write.

The findings were published online in Nutrients.

Mixed bag of studies

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that deficient dietary omega-3 intake is a modifiable risk factor for depression and that individuals with low consumption of omega-3 food sources have more depressive symptoms.

However, the results are inconsistent, and few longitudinal studies have addressed this association, the investigators note.

The new analysis included 13,879 adults (aged 39-65 years or older) participating in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) from 2008 to 2014.

Data on depressive episodes were obtained with the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), and food consumption was measured with the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

The target dietary components were total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and the omega-3 fatty acids: alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

The majority of participants had adequate dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and none was taking omega-3 supplements.

In the fully adjusted model, consumption of fatty acids from the omega-3 family had a protective effect against maintenance of depressive episodes, showing “important associations, although the significance levels are borderline, possibly due to the sample size,” the researchers report.

In regard to onset of depressive episodes, estimates from the fully adjusted model suggest that a higher consumption of omega-3 acids (total and subtypes) is associated with lower risk for depressive episodes – with significant associations for omega-3 and alpha-linolenic acid.

The investigators note that strengths of the study include “its originality, as it is the first to assess associations between maintenance and incidence of depressive episodes and consumption of omega-3, besides the use of data from the ELSA-Brasil Study, with rigorous data collection protocols and reliable and validated instruments, thus guaranteeing the quality of the sample and the data.”

A study limitation, however, was that the ELSA-Brasil sample consists only of public employees, with the potential for a selection bias such as healthy worker phenomenon, the researchers note. Another was the use of the FFQ, which may underestimate daily intake of foods and depends on individual participant recall – all of which could possibly lead to a differential classification bias.

Interpret cautiously

Commenting on the study, David Mischoulon, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, and director of the depression clinical and research program at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said that data on omega-3s in depression are “very mixed.”

“A lot of the studies don’t necessarily agree with each other. Certainly, in studies that try to seek an association between omega-3 use and depression, it’s always complicated because it can be difficult to control for all variables that could be contributing to the result that you get,” said Dr. Mischoulon, who is also a member of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and was not involved in the research.

A caveat to the current study was that diet was assessed only at baseline, “so we don’t really know whether there were any substantial dietary changes over time, he noted.

He also cautioned that it is hard to draw any firm conclusions from this type of study.

“In general, in studies with a large sample, which this study has, it’s easier to find statistically significant differences. But you need to ask yourself: Does it really matter? Is it enough to have a clinical impact and make a difference?” Dr. Mischoulon said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and by the Ministry of Health. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals and heckel medizintechnik GmbH and honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. He also works with the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute, which has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies and the National Institute of Mental Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NUTRIENTS

New ovulatory disorder classifications from FIGO replace 50-year-old system

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

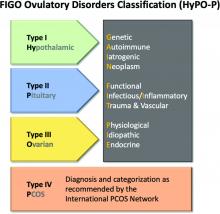

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS

How do you live with COVID? One doctor’s personal experience

Early in 2020, Anne Peters, MD, caught COVID-19. The author of Medscape’s “Peters on Diabetes” column was sick in March 2020 before state-mandated lockdowns, and well before there were any vaccines.

She remembers sitting in a small exam room with two patients who had flown to her Los Angeles office from New York. The elderly couple had hearing difficulties, so Dr. Peters sat close to them, putting on a continuous glucose monitor. “At that time, we didn’t think of COVID-19 as being in L.A.,” Dr. Peters recalled, “so I think we were not terribly consistent at mask-wearing due to the need to educate.”

“Several days later, I got COVID, but I didn’t know I had COVID per se. I felt crappy, had a terrible sore throat, lost my sense of taste and smell [which was not yet described as a COVID symptom], was completely exhausted, but had no fever or cough, which were the only criteria for getting COVID tested at the time. I didn’t know I had been exposed until 2 weeks later, when the patient’s assistant returned the sensor warning us to ‘be careful’ with it because the patient and his wife were recovering from COVID.”

That early battle with COVID-19 was just the beginning of what would become a 2-year struggle, including familial loss amid her own health problems and concerns about the under-resourced patients she cares for. Here, she shares her journey through the pandemic with this news organization.

Question: Thanks for talking to us. Let’s discuss your journey over these past 2.5 years.

Answer: Everybody has their own COVID story because we all went through this together. Some of us have worse COVID stories, and some of us have better ones, but all have been impacted.

I’m not a sick person. I’m a very healthy person but COVID made me so unwell for 2 years. The brain fog and fatigue were nothing compared to the autonomic neuropathy that affected my heart. It was really limiting for me. And I still don’t know the long-term implications, looking 20-30 years from now.

Q: When you initially had COVID, what were your symptoms? What was the impact?

A: I had all the symptoms of COVID, except for a cough and fever. I lost my sense of taste and smell. I had a horrible headache, a sore throat, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t get tested because I didn’t have the right symptoms.

Despite being sick, I never stopped working but just switched to telemedicine. I also took my regular monthly trip to our cabin in Montana. I unknowingly flew on a plane with COVID. I wore a well-fitted N95 mask, so I don’t think I gave anybody COVID. I didn’t give COVID to my partner, Eric, which is hard to believe as – at 77 – he’s older than me. He has diabetes, heart disease, and every other high-risk characteristic. If he’d gotten COVID back then, it would have been terrible, as there were no treatments, but luckily he didn’t get it.

Q: When were you officially diagnosed?

A: Two or 3 months after I thought I might have had COVID, I checked my antibodies, which tested strongly positive for a prior COVID infection. That was when I knew all the symptoms I’d had were due to the disease.

Q: Not only were you dealing with your own illness, but also that of those close to you. Can you talk about that?

A: In April 2020, my mother who was in her 90s and otherwise healthy except for dementia, got COVID. She could have gotten it from me. I visited often but wore a mask. She had all the horrible pulmonary symptoms. In her advance directive, she didn’t want to be hospitalized so I kept her in her home. She died from COVID in her own bed. It was fairly brutal, but at least I kept her where she felt comforted.

My 91-year-old dad was living in a different residential facility. Throughout COVID he had become very depressed because his social patterns had changed. Prior to COVID, they all ate together, but during the pandemic they were unable to. He missed his social connections, disliked being isolated in his room, hated everyone in masks.

He was a bit demented, but not so much that he couldn’t communicate with me or remember where his grandson was going to law school. I wasn’t allowed inside the facility, which was hard on him. I hadn’t told him his wife died because the hospice social workers advised me that I shouldn’t give him news that he couldn’t process readily until I could spend time with him. Unfortunately, that time never came. In December 2020, he got COVID. One of the people in that facility had gone to the hospital, came back, and tested negative, but actually had COVID and gave it to my dad. The guy who gave it to my dad didn’t die but my dad was terribly ill. He died 2 weeks short of getting his vaccine. He was coherent enough to have a conversation. I asked him: ‘Do you want to go to the hospital?’ And he said: ‘No, because it would be too scary,’ since he couldn’t be with me. I put him on hospice and held his hand as he died from pulmonary COVID, which was awful. I couldn’t give him enough morphine or valium to ease his breathing. But his last words to me were “I love you,” and at the very end he seemed peaceful, which was a blessing.

I got an autopsy, because he wanted one. Nothing else was wrong with him other than COVID. It destroyed his lungs. The rest of him was fine – no heart disease, cancer, or anything else. He died of COVID-19, the same as my mother.

That same week, my aunt, my only surviving older relative, who was in Des Moines, Iowa, died of COVID-19. All three family members died before the vaccine came out.

It was hard to lose my parents. I’m the only surviving child because my sister died in her 20s. It’s not been an easy pandemic. But what pandemic is easy? I just happened to have lost more people than most. Ironically, my grandfather was one of the legionnaires at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia in 1976 and died of Legionnaire’s disease before we knew what was causing the outbreak.

Q: Were you still struggling with COVID?

A: COVID impacted my whole body. I lost a lot of weight. I didn’t want to eat, and my gastrointestinal system was not happy. It took a while for my sense of taste and smell to come back. Nothing tasted good. I’m not a foodie; I don’t really care about food. We could get takeout or whatever, but none of it appealed to me. I’m not so sure it was a taste thing, I just didn’t feel like eating.

I didn’t realize I had “brain fog” per se, because I felt stressed and overwhelmed by the pandemic and my patients’ concerns. But one day, about 3 months after I had developed COVID, I woke up without the fog. Which made me aware that I hadn’t been feeling right up until that point.

The worst symptoms, however, were cardiac. I noticed also immediately that my heart rate went up very quickly with minimal exertion. My pulse has always been in the 55-60 bpm range, and suddenly just walking across a room made it go up to over 140 bpm. If I did any aerobic activity, it went up over 160 and would be associated with dyspnea and chest pain. I believed these were all post-COVID symptoms and felt validated when reports of others having similar issues were published in the literature.

Q: Did you continue seeing patients?

A: Yes, of course. Patients never needed their doctors more. In East L.A., where patients don’t have easy access to telemedicine, I kept going into clinic throughout the pandemic. In the more affluent Westside of Los Angeles, we switched to telemedicine, which was quite effective for most. However, because diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID, my patients were understandably afraid. I’ve never been busier, but (like all health care providers), I became more of a COVID provider than a diabetologist.

Q: Do you feel your battle with COVID impacted your work?

A: It didn’t affect me at work. If I was sitting still, I was fine. Sitting at home at a desk, I didn’t notice any symptoms. But as a habitual stair-user, I would be gasping for breath in the stairwell because I couldn’t go up the stairs to my office as I once could.

I think you empathize more with people who had COVID (when you’ve had it yourself). There was such a huge patient burden. And I think that’s been the thing that’s affected health care providers the most – no matter what specialty we’re in – that nobody has answers.

Q: What happened after you had your vaccine?

A: The vaccine itself was fine. I didn’t have any reaction to the first two doses. But the first booster made my cardiac issues worse.

By this point, my cardiac problems stopped me from exercising. I even went to the ER with chest pain once because I was having palpitations and chest pressure caused by simply taking my morning shower. Fortunately, I wasn’t having an MI, but I certainly wasn’t “normal.”

My measure of my fitness is the cross-country skiing trail I use in Montana. I know exactly how far I can ski. Usually I can do the loop in 35 minutes. After COVID, I lasted 10 minutes. I would be tachycardic, short of breath with chest pain radiating down my left arm. I would rest and try to keep going. But with each rest period, I only got worse. I would be laying in the snow and strangers would ask if I needed help.

Q: What helped you?

A: I’ve read a lot about long COVID and have tried to learn from the experts. Of course, I never went to a doctor directly, although I did ask colleagues for advice. What I learned was to never push myself. I forced myself to create an exercise schedule where I only exercised three times a week with rest days in between. When exercising, the second my heart rate went above 140 bpm, I stopped until I could get it back down. I would push against this new limit, even though my limit was low.

Additionally, I worked on my breathing patterns and did meditative breathing for 10 minutes twice daily using a commercially available app.

Although progress was slow, I did improve, and by June 2022, I seemed back to normal. I was not as fit as I was prior to COVID and needed to improve, but the tachycardic response to exercise and cardiac symptoms were gone. I felt like my normal self. Normal enough to go on a spot packing trip in the Sierras in August. (Horses carried us and a mule carried the gear over the 12,000-foot pass into the mountains, and then left my friend and me high in the Sierras for a week.) We were camped above 10,000 feet and every day hiked up to another high mountain lake where we fly-fished for trout that we ate for dinner. The hikes were a challenge, but not abnormally so. Not as they would have been while I had long COVID.

Q: What is the current atmosphere in your clinic?

A: COVID is much milder now in my vaccinated patients, but I feel most health care providers are exhausted. Many of my staff left when COVID hit because they didn’t want to keep working. It made practicing medicine exhausting. There’s been a shortage of nurses, a shortage of everything. We’ve been required to do a whole lot more than we ever did before. It’s much harder to be a doctor. This pandemic is the first time I’ve ever thought of quitting. Granted, I lost my whole family, or at least the older generation, but it’s just been almost overwhelming.

On the plus side, almost every one of my patients has been vaccinated, because early on, people would ask: “Do you trust this vaccine?” I would reply: “I saw my parents die from COVID when they weren’t vaccinated, so you’re getting vaccinated. This is real and the vaccines help.” It made me very good at convincing people to get vaccines because I knew what it was like to see someone dying from COVID up close.

Q: What advice do you have for those struggling with the COVID pandemic?

A: People need to decide what their own risk is for getting sick and how many times they want to get COVID. At this point, I want people to go out, but safely. In the beginning, when my patients said, “can I go visit my granddaughter?” I said, “no,” but that was before we had the vaccine. Now I feel it is safe to go out using common sense. I still have my patients wear masks on planes. I still have patients try to eat outside as much as possible. And I tell people to take the precautions that make sense, but I tell them to go out and do things because life is short.

I had a patient in his 70s who has many risk factors like heart disease and diabetes. His granddaughter’s Bat Mitzvah in Florida was coming up. He asked: “Can I go?” I told him “Yes,” but to be safe – to wear an N95 mask on the plane and at the event, and stay in his own hotel room, rather than with the whole family. I said, “You need to do this.” Earlier in the pandemic, I saw people who literally died from loneliness and isolation.

He and his wife flew there. He sent me a picture of himself with his granddaughter. When he returned, he showed me a handwritten note from her that said, “I love you so much. Everyone else canceled, which made me cry. You’re the only one who came. You have no idea how much this meant to me.”

He’s back in L.A., and he didn’t get COVID. He said, “It was the best thing I’ve done in years.” That’s what I need to help people with, navigating this world with COVID and assessing risks and benefits. As with all of medicine, my advice is individualized. My advice changes based on the major circulating variant and the rates of the virus in the population, as well as the risk factors of the individual.

Q: What are you doing now?

A: I’m trying to avoid getting COVID again, or another booster. I could get pre-exposure monoclonal antibodies but am waiting to do anything further until I see what happens over the fall and winter. I still wear a mask inside but now do a mix of in-person and telemedicine visits. I still try to go to outdoor restaurants, which is easy in California. But I’m flying to see my son in New York and plan to go to Europe this fall for a meeting. I also go to my cabin in Montana every month to get my “dose” of the wilderness. Overall, I travel for conferences and speaking engagements much less because I have learned the joy of staying home.

Thinking back on my life as a doctor, my career began as an intern at Stanford rotating through Ward 5B, the AIDS unit at San Francisco General Hospital, and will likely end with COVID. In spite of all our medical advances, my generation of physicians, much as many generations before us, has a front-row seat to the vulnerability of humans to infectious diseases and how far we still need to go to protect our patients from communicable illness.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anne L. Peters, MD, is a professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She has published more than 200 articles, reviews, and abstracts; three books on diabetes; and has been an investigator for more than 40 research studies. She has spoken internationally at over 400 programs and serves on many committees of several professional organizations.

Early in 2020, Anne Peters, MD, caught COVID-19. The author of Medscape’s “Peters on Diabetes” column was sick in March 2020 before state-mandated lockdowns, and well before there were any vaccines.

She remembers sitting in a small exam room with two patients who had flown to her Los Angeles office from New York. The elderly couple had hearing difficulties, so Dr. Peters sat close to them, putting on a continuous glucose monitor. “At that time, we didn’t think of COVID-19 as being in L.A.,” Dr. Peters recalled, “so I think we were not terribly consistent at mask-wearing due to the need to educate.”

“Several days later, I got COVID, but I didn’t know I had COVID per se. I felt crappy, had a terrible sore throat, lost my sense of taste and smell [which was not yet described as a COVID symptom], was completely exhausted, but had no fever or cough, which were the only criteria for getting COVID tested at the time. I didn’t know I had been exposed until 2 weeks later, when the patient’s assistant returned the sensor warning us to ‘be careful’ with it because the patient and his wife were recovering from COVID.”

That early battle with COVID-19 was just the beginning of what would become a 2-year struggle, including familial loss amid her own health problems and concerns about the under-resourced patients she cares for. Here, she shares her journey through the pandemic with this news organization.

Question: Thanks for talking to us. Let’s discuss your journey over these past 2.5 years.

Answer: Everybody has their own COVID story because we all went through this together. Some of us have worse COVID stories, and some of us have better ones, but all have been impacted.

I’m not a sick person. I’m a very healthy person but COVID made me so unwell for 2 years. The brain fog and fatigue were nothing compared to the autonomic neuropathy that affected my heart. It was really limiting for me. And I still don’t know the long-term implications, looking 20-30 years from now.

Q: When you initially had COVID, what were your symptoms? What was the impact?

A: I had all the symptoms of COVID, except for a cough and fever. I lost my sense of taste and smell. I had a horrible headache, a sore throat, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t get tested because I didn’t have the right symptoms.

Despite being sick, I never stopped working but just switched to telemedicine. I also took my regular monthly trip to our cabin in Montana. I unknowingly flew on a plane with COVID. I wore a well-fitted N95 mask, so I don’t think I gave anybody COVID. I didn’t give COVID to my partner, Eric, which is hard to believe as – at 77 – he’s older than me. He has diabetes, heart disease, and every other high-risk characteristic. If he’d gotten COVID back then, it would have been terrible, as there were no treatments, but luckily he didn’t get it.

Q: When were you officially diagnosed?

A: Two or 3 months after I thought I might have had COVID, I checked my antibodies, which tested strongly positive for a prior COVID infection. That was when I knew all the symptoms I’d had were due to the disease.

Q: Not only were you dealing with your own illness, but also that of those close to you. Can you talk about that?

A: In April 2020, my mother who was in her 90s and otherwise healthy except for dementia, got COVID. She could have gotten it from me. I visited often but wore a mask. She had all the horrible pulmonary symptoms. In her advance directive, she didn’t want to be hospitalized so I kept her in her home. She died from COVID in her own bed. It was fairly brutal, but at least I kept her where she felt comforted.

My 91-year-old dad was living in a different residential facility. Throughout COVID he had become very depressed because his social patterns had changed. Prior to COVID, they all ate together, but during the pandemic they were unable to. He missed his social connections, disliked being isolated in his room, hated everyone in masks.

He was a bit demented, but not so much that he couldn’t communicate with me or remember where his grandson was going to law school. I wasn’t allowed inside the facility, which was hard on him. I hadn’t told him his wife died because the hospice social workers advised me that I shouldn’t give him news that he couldn’t process readily until I could spend time with him. Unfortunately, that time never came. In December 2020, he got COVID. One of the people in that facility had gone to the hospital, came back, and tested negative, but actually had COVID and gave it to my dad. The guy who gave it to my dad didn’t die but my dad was terribly ill. He died 2 weeks short of getting his vaccine. He was coherent enough to have a conversation. I asked him: ‘Do you want to go to the hospital?’ And he said: ‘No, because it would be too scary,’ since he couldn’t be with me. I put him on hospice and held his hand as he died from pulmonary COVID, which was awful. I couldn’t give him enough morphine or valium to ease his breathing. But his last words to me were “I love you,” and at the very end he seemed peaceful, which was a blessing.

I got an autopsy, because he wanted one. Nothing else was wrong with him other than COVID. It destroyed his lungs. The rest of him was fine – no heart disease, cancer, or anything else. He died of COVID-19, the same as my mother.

That same week, my aunt, my only surviving older relative, who was in Des Moines, Iowa, died of COVID-19. All three family members died before the vaccine came out.

It was hard to lose my parents. I’m the only surviving child because my sister died in her 20s. It’s not been an easy pandemic. But what pandemic is easy? I just happened to have lost more people than most. Ironically, my grandfather was one of the legionnaires at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia in 1976 and died of Legionnaire’s disease before we knew what was causing the outbreak.

Q: Were you still struggling with COVID?

A: COVID impacted my whole body. I lost a lot of weight. I didn’t want to eat, and my gastrointestinal system was not happy. It took a while for my sense of taste and smell to come back. Nothing tasted good. I’m not a foodie; I don’t really care about food. We could get takeout or whatever, but none of it appealed to me. I’m not so sure it was a taste thing, I just didn’t feel like eating.

I didn’t realize I had “brain fog” per se, because I felt stressed and overwhelmed by the pandemic and my patients’ concerns. But one day, about 3 months after I had developed COVID, I woke up without the fog. Which made me aware that I hadn’t been feeling right up until that point.

The worst symptoms, however, were cardiac. I noticed also immediately that my heart rate went up very quickly with minimal exertion. My pulse has always been in the 55-60 bpm range, and suddenly just walking across a room made it go up to over 140 bpm. If I did any aerobic activity, it went up over 160 and would be associated with dyspnea and chest pain. I believed these were all post-COVID symptoms and felt validated when reports of others having similar issues were published in the literature.

Q: Did you continue seeing patients?

A: Yes, of course. Patients never needed their doctors more. In East L.A., where patients don’t have easy access to telemedicine, I kept going into clinic throughout the pandemic. In the more affluent Westside of Los Angeles, we switched to telemedicine, which was quite effective for most. However, because diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID, my patients were understandably afraid. I’ve never been busier, but (like all health care providers), I became more of a COVID provider than a diabetologist.

Q: Do you feel your battle with COVID impacted your work?

A: It didn’t affect me at work. If I was sitting still, I was fine. Sitting at home at a desk, I didn’t notice any symptoms. But as a habitual stair-user, I would be gasping for breath in the stairwell because I couldn’t go up the stairs to my office as I once could.

I think you empathize more with people who had COVID (when you’ve had it yourself). There was such a huge patient burden. And I think that’s been the thing that’s affected health care providers the most – no matter what specialty we’re in – that nobody has answers.

Q: What happened after you had your vaccine?

A: The vaccine itself was fine. I didn’t have any reaction to the first two doses. But the first booster made my cardiac issues worse.

By this point, my cardiac problems stopped me from exercising. I even went to the ER with chest pain once because I was having palpitations and chest pressure caused by simply taking my morning shower. Fortunately, I wasn’t having an MI, but I certainly wasn’t “normal.”

My measure of my fitness is the cross-country skiing trail I use in Montana. I know exactly how far I can ski. Usually I can do the loop in 35 minutes. After COVID, I lasted 10 minutes. I would be tachycardic, short of breath with chest pain radiating down my left arm. I would rest and try to keep going. But with each rest period, I only got worse. I would be laying in the snow and strangers would ask if I needed help.

Q: What helped you?

A: I’ve read a lot about long COVID and have tried to learn from the experts. Of course, I never went to a doctor directly, although I did ask colleagues for advice. What I learned was to never push myself. I forced myself to create an exercise schedule where I only exercised three times a week with rest days in between. When exercising, the second my heart rate went above 140 bpm, I stopped until I could get it back down. I would push against this new limit, even though my limit was low.

Additionally, I worked on my breathing patterns and did meditative breathing for 10 minutes twice daily using a commercially available app.

Although progress was slow, I did improve, and by June 2022, I seemed back to normal. I was not as fit as I was prior to COVID and needed to improve, but the tachycardic response to exercise and cardiac symptoms were gone. I felt like my normal self. Normal enough to go on a spot packing trip in the Sierras in August. (Horses carried us and a mule carried the gear over the 12,000-foot pass into the mountains, and then left my friend and me high in the Sierras for a week.) We were camped above 10,000 feet and every day hiked up to another high mountain lake where we fly-fished for trout that we ate for dinner. The hikes were a challenge, but not abnormally so. Not as they would have been while I had long COVID.

Q: What is the current atmosphere in your clinic?

A: COVID is much milder now in my vaccinated patients, but I feel most health care providers are exhausted. Many of my staff left when COVID hit because they didn’t want to keep working. It made practicing medicine exhausting. There’s been a shortage of nurses, a shortage of everything. We’ve been required to do a whole lot more than we ever did before. It’s much harder to be a doctor. This pandemic is the first time I’ve ever thought of quitting. Granted, I lost my whole family, or at least the older generation, but it’s just been almost overwhelming.

On the plus side, almost every one of my patients has been vaccinated, because early on, people would ask: “Do you trust this vaccine?” I would reply: “I saw my parents die from COVID when they weren’t vaccinated, so you’re getting vaccinated. This is real and the vaccines help.” It made me very good at convincing people to get vaccines because I knew what it was like to see someone dying from COVID up close.

Q: What advice do you have for those struggling with the COVID pandemic?