User login

Clinical Endocrinology News is an independent news source that provides endocrinologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the endocrinologist's practice. Specialty topics include Diabetes, Lipid & Metabolic Disorders Menopause, Obesity, Osteoporosis, Pediatric Endocrinology, Pituitary, Thyroid & Adrenal Disorders, and Reproductive Endocrinology. Featured content includes Commentaries, Implementin Health Reform, Law & Medicine, and In the Loop, the blog of Clinical Endocrinology News. Clinical Endocrinology News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

addict

addicted

addicting

addiction

adult sites

alcohol

antibody

ass

attorney

audit

auditor

babies

babpa

baby

ban

banned

banning

best

bisexual

bitch

bleach

blog

blow job

bondage

boobs

booty

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cheap

cheapest

class action

cocaine

cock

counterfeit drug

crack

crap

crime

criminal

cunt

curable

cure

dangerous

dangers

dead

deadly

death

defend

defended

depedent

dependence

dependent

detergent

dick

die

dildo

drug abuse

drug recall

dying

fag

fake

fatal

fatalities

fatality

free

fuck

gangs

gingivitis

guns

hardcore

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

home remedies

homo

horny

hypersensitivity

hypoglycemia treatment

illegal drug use

illegal use of prescription

incest

infant

infants

job

ketoacidosis

kill

killer

killing

kinky

law suit

lawsuit

lawyer

lesbian

marijuana

medicine for hypoglycemia

murder

naked

natural

newborn

nigger

noise

nude

nudity

orgy

over the counter

overdosage

overdose

overdosed

overdosing

penis

pimp

pistol

porn

porno

pornographic

pornography

prison

profanity

purchase

purchasing

pussy

queer

rape

rapist

recall

recreational drug

rob

robberies

sale

sales

sex

sexual

shit

shoot

slut

slutty

stole

stolen

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

supply company

theft

thief

thieves

tit

toddler

toddlers

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treating dka

treating hypoglycemia

treatment for hypoglycemia

vagina

violence

whore

withdrawal

without prescription

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Subclinical CAD by CT predicts MI risk, with or without stenoses

About half of middle-aged adults in the community without cardiovascular (CV) symptoms have coronary atherosclerosis by CT angiography (CTA) that puts them at substantial risk for myocardial infarction (MI), suggests a prospective cohort study.

The 10% of participants who had subclinical disease considered obstructive at CTA showed a ninefold increased risk for MI over several years. Obstructive disease seemed to elevate risk more than subclinical disease that wasn’t obstructive but still considered extensive within the coronary arteries.

The findings, based on a Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, are new for CTA but consistent with research based on coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and other ways to assess CV risk, say researchers.

Although all participants underwent CTA, such imaging isn’t used in the general population for atherosclerosis screening. But the findings may have implications for “opportunistic screening” for subclinical coronary disease at CTA conducted for other reasons, notes the study’s report, published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Identification of luminal obstructive or extensive subclinical coronary atherosclerosis” could potentially provide “clinically relevant, incremental risk assessment” in nonischemic patients who undergo cardiac CT or electrocardiogram-gated chest CT before procedures such as arrhythmia ablation or valve repair, it states.

Such patients found with subclinical coronary atherosclerosis might potentially “benefit from referral to intensified cardiovascular primary prevention therapy,” write the authors, led by Andreas Fuchs, MD, PhD, Copenhagen University Hospital-Rigshospitalet.

The group acknowledges the findings may not entirely apply to a non-Danish population.

A screening role for CTA?

Whether CTA has a role to play in adults without symptoms “is a big, open question in the field right now,” observed Ron Blankstein, MD, not associated with the current analysis, for this news organization.

Most population studies of CV risk prediction, such as MESA, have looked at CAC scores, not CTA, and have shown that “the more plaque individuals have, the higher the risk.” The current findings are similar but novel in coming from coronary CTA in a large asymptomatic community population, said Dr. Blankstein, who is director of cardiac CT at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“It’s possible that patients who have obstructive plaque in general tend to have a larger amount of plaque as well,” he said. So, while the study suggests that “the more plaque individuals have, the worse their overall risk,” it also shows that the risk “is enhanced even more if they have obstructive disease.”

The Danish cohort analysis “provides a unique opportunity to study the contemporary natural history of coronary artery disease in the absence of intervention,” notes an accompanying editorial.

For example, both patients and clinicians were blinded to CTA results, and CV preventive therapies weren’t common, observe Michael McDermott, MBChB, and David E. Newby, DM, PhD, of the BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh.

The analysis suggests that subclinical coronary disease that is obstructive predicts MI risk more strongly than extensive coronary disease, they note, and may be present in two-thirds of MI patients. “This contrasts with symptomatic populations, where nonobstructive disease accounts for most future myocardial infarctions, presumably from plaque rupture.”

It also points to “strong associations between nonobstructive extensive disease and adverse plaque characteristics,” write Dr. McDermott and Dr. Newby. “This underscores the major importance of plaque burden” for the prediction of coronary events.

Graded risk

The analysis included 9,533 persons aged 40 and older without known ischemic heart disease or symptoms with available CTA assessments.

Obstructive disease, defined as presence of a luminal stenosis of at least 50%, was seen in 10% and nonobstructive disease in 36% of the total cohort, the report states.

Disease occupying more than one-third of the coronary tree was considered extensive and less than one-third of the coronaries nonextensive, occurring in 10.5% and 35.8% of the cohort, respectively.

There were 71 MIs and 193 deaths over a median of 3.5 years. The adjusted relative risk for MI, compared with those without coronary atherosclerosis, was:

- 7.65 (95% confidence interval, 3.53-16.57) overall in patients with extensive disease.

- 8.28 (95% CI, 3.75-18.32) in those with obstructive but nonextensive disease.

- 9.19 (95% CI, 4.49-18.82) overall in those with obstructive disease.

- 12.48 (95% CI, 5.50-28.12) in those with or obstructive and extensive disease.

The adjusted RR for the composite of death or MI was also elevated in persons with extensive disease:

- 2.70 (95% CI, 1.72-4.25) in those with extensive but nonobstructive disease.

- 3.15 (95% CI, 2.05-4.83) in those with extensive and obstructive disease.

“It’s one thing to show that the more plaque, the higher the risk,” Dr. Blankstein said. But “does the information ultimately lead to better outcomes? Do patients have fewer MIs or fewer deaths?” Several ongoing randomized trials are exploring these questions.

They include DANE-HEART (Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography for Primary Prevention), projected to enroll about 6,000 participants from the Copenhagen General Population Study cohort who have at least one CV risk factor, and SCOT-HEART 2 (second Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography for the Prevention of Myocardial Infarction), enrolling a similar cohort in Scotland.

The study was supported by grants from AP Møller og Hustru Chastine Mc-Kinney Møllers Fond, the Research Council of Rigshospitalet, and Danish Heart Foundation. Dr. Fuchs reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors can be found here. Dr. Blankstein recently disclosed serving as a consultant to Amgen, Caristo Diagnostics, Novartis, and Silence Therapeutics. Disclosures for Dr. McDermott and Dr. Newby, who are SCOT-HEART 2 investigators, can be found here.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

About half of middle-aged adults in the community without cardiovascular (CV) symptoms have coronary atherosclerosis by CT angiography (CTA) that puts them at substantial risk for myocardial infarction (MI), suggests a prospective cohort study.

The 10% of participants who had subclinical disease considered obstructive at CTA showed a ninefold increased risk for MI over several years. Obstructive disease seemed to elevate risk more than subclinical disease that wasn’t obstructive but still considered extensive within the coronary arteries.

The findings, based on a Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, are new for CTA but consistent with research based on coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and other ways to assess CV risk, say researchers.

Although all participants underwent CTA, such imaging isn’t used in the general population for atherosclerosis screening. But the findings may have implications for “opportunistic screening” for subclinical coronary disease at CTA conducted for other reasons, notes the study’s report, published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Identification of luminal obstructive or extensive subclinical coronary atherosclerosis” could potentially provide “clinically relevant, incremental risk assessment” in nonischemic patients who undergo cardiac CT or electrocardiogram-gated chest CT before procedures such as arrhythmia ablation or valve repair, it states.

Such patients found with subclinical coronary atherosclerosis might potentially “benefit from referral to intensified cardiovascular primary prevention therapy,” write the authors, led by Andreas Fuchs, MD, PhD, Copenhagen University Hospital-Rigshospitalet.

The group acknowledges the findings may not entirely apply to a non-Danish population.

A screening role for CTA?

Whether CTA has a role to play in adults without symptoms “is a big, open question in the field right now,” observed Ron Blankstein, MD, not associated with the current analysis, for this news organization.

Most population studies of CV risk prediction, such as MESA, have looked at CAC scores, not CTA, and have shown that “the more plaque individuals have, the higher the risk.” The current findings are similar but novel in coming from coronary CTA in a large asymptomatic community population, said Dr. Blankstein, who is director of cardiac CT at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“It’s possible that patients who have obstructive plaque in general tend to have a larger amount of plaque as well,” he said. So, while the study suggests that “the more plaque individuals have, the worse their overall risk,” it also shows that the risk “is enhanced even more if they have obstructive disease.”

The Danish cohort analysis “provides a unique opportunity to study the contemporary natural history of coronary artery disease in the absence of intervention,” notes an accompanying editorial.

For example, both patients and clinicians were blinded to CTA results, and CV preventive therapies weren’t common, observe Michael McDermott, MBChB, and David E. Newby, DM, PhD, of the BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh.

The analysis suggests that subclinical coronary disease that is obstructive predicts MI risk more strongly than extensive coronary disease, they note, and may be present in two-thirds of MI patients. “This contrasts with symptomatic populations, where nonobstructive disease accounts for most future myocardial infarctions, presumably from plaque rupture.”

It also points to “strong associations between nonobstructive extensive disease and adverse plaque characteristics,” write Dr. McDermott and Dr. Newby. “This underscores the major importance of plaque burden” for the prediction of coronary events.

Graded risk

The analysis included 9,533 persons aged 40 and older without known ischemic heart disease or symptoms with available CTA assessments.

Obstructive disease, defined as presence of a luminal stenosis of at least 50%, was seen in 10% and nonobstructive disease in 36% of the total cohort, the report states.

Disease occupying more than one-third of the coronary tree was considered extensive and less than one-third of the coronaries nonextensive, occurring in 10.5% and 35.8% of the cohort, respectively.

There were 71 MIs and 193 deaths over a median of 3.5 years. The adjusted relative risk for MI, compared with those without coronary atherosclerosis, was:

- 7.65 (95% confidence interval, 3.53-16.57) overall in patients with extensive disease.

- 8.28 (95% CI, 3.75-18.32) in those with obstructive but nonextensive disease.

- 9.19 (95% CI, 4.49-18.82) overall in those with obstructive disease.

- 12.48 (95% CI, 5.50-28.12) in those with or obstructive and extensive disease.

The adjusted RR for the composite of death or MI was also elevated in persons with extensive disease:

- 2.70 (95% CI, 1.72-4.25) in those with extensive but nonobstructive disease.

- 3.15 (95% CI, 2.05-4.83) in those with extensive and obstructive disease.

“It’s one thing to show that the more plaque, the higher the risk,” Dr. Blankstein said. But “does the information ultimately lead to better outcomes? Do patients have fewer MIs or fewer deaths?” Several ongoing randomized trials are exploring these questions.

They include DANE-HEART (Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography for Primary Prevention), projected to enroll about 6,000 participants from the Copenhagen General Population Study cohort who have at least one CV risk factor, and SCOT-HEART 2 (second Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography for the Prevention of Myocardial Infarction), enrolling a similar cohort in Scotland.

The study was supported by grants from AP Møller og Hustru Chastine Mc-Kinney Møllers Fond, the Research Council of Rigshospitalet, and Danish Heart Foundation. Dr. Fuchs reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors can be found here. Dr. Blankstein recently disclosed serving as a consultant to Amgen, Caristo Diagnostics, Novartis, and Silence Therapeutics. Disclosures for Dr. McDermott and Dr. Newby, who are SCOT-HEART 2 investigators, can be found here.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

About half of middle-aged adults in the community without cardiovascular (CV) symptoms have coronary atherosclerosis by CT angiography (CTA) that puts them at substantial risk for myocardial infarction (MI), suggests a prospective cohort study.

The 10% of participants who had subclinical disease considered obstructive at CTA showed a ninefold increased risk for MI over several years. Obstructive disease seemed to elevate risk more than subclinical disease that wasn’t obstructive but still considered extensive within the coronary arteries.

The findings, based on a Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, are new for CTA but consistent with research based on coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and other ways to assess CV risk, say researchers.

Although all participants underwent CTA, such imaging isn’t used in the general population for atherosclerosis screening. But the findings may have implications for “opportunistic screening” for subclinical coronary disease at CTA conducted for other reasons, notes the study’s report, published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Identification of luminal obstructive or extensive subclinical coronary atherosclerosis” could potentially provide “clinically relevant, incremental risk assessment” in nonischemic patients who undergo cardiac CT or electrocardiogram-gated chest CT before procedures such as arrhythmia ablation or valve repair, it states.

Such patients found with subclinical coronary atherosclerosis might potentially “benefit from referral to intensified cardiovascular primary prevention therapy,” write the authors, led by Andreas Fuchs, MD, PhD, Copenhagen University Hospital-Rigshospitalet.

The group acknowledges the findings may not entirely apply to a non-Danish population.

A screening role for CTA?

Whether CTA has a role to play in adults without symptoms “is a big, open question in the field right now,” observed Ron Blankstein, MD, not associated with the current analysis, for this news organization.

Most population studies of CV risk prediction, such as MESA, have looked at CAC scores, not CTA, and have shown that “the more plaque individuals have, the higher the risk.” The current findings are similar but novel in coming from coronary CTA in a large asymptomatic community population, said Dr. Blankstein, who is director of cardiac CT at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“It’s possible that patients who have obstructive plaque in general tend to have a larger amount of plaque as well,” he said. So, while the study suggests that “the more plaque individuals have, the worse their overall risk,” it also shows that the risk “is enhanced even more if they have obstructive disease.”

The Danish cohort analysis “provides a unique opportunity to study the contemporary natural history of coronary artery disease in the absence of intervention,” notes an accompanying editorial.

For example, both patients and clinicians were blinded to CTA results, and CV preventive therapies weren’t common, observe Michael McDermott, MBChB, and David E. Newby, DM, PhD, of the BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh.

The analysis suggests that subclinical coronary disease that is obstructive predicts MI risk more strongly than extensive coronary disease, they note, and may be present in two-thirds of MI patients. “This contrasts with symptomatic populations, where nonobstructive disease accounts for most future myocardial infarctions, presumably from plaque rupture.”

It also points to “strong associations between nonobstructive extensive disease and adverse plaque characteristics,” write Dr. McDermott and Dr. Newby. “This underscores the major importance of plaque burden” for the prediction of coronary events.

Graded risk

The analysis included 9,533 persons aged 40 and older without known ischemic heart disease or symptoms with available CTA assessments.

Obstructive disease, defined as presence of a luminal stenosis of at least 50%, was seen in 10% and nonobstructive disease in 36% of the total cohort, the report states.

Disease occupying more than one-third of the coronary tree was considered extensive and less than one-third of the coronaries nonextensive, occurring in 10.5% and 35.8% of the cohort, respectively.

There were 71 MIs and 193 deaths over a median of 3.5 years. The adjusted relative risk for MI, compared with those without coronary atherosclerosis, was:

- 7.65 (95% confidence interval, 3.53-16.57) overall in patients with extensive disease.

- 8.28 (95% CI, 3.75-18.32) in those with obstructive but nonextensive disease.

- 9.19 (95% CI, 4.49-18.82) overall in those with obstructive disease.

- 12.48 (95% CI, 5.50-28.12) in those with or obstructive and extensive disease.

The adjusted RR for the composite of death or MI was also elevated in persons with extensive disease:

- 2.70 (95% CI, 1.72-4.25) in those with extensive but nonobstructive disease.

- 3.15 (95% CI, 2.05-4.83) in those with extensive and obstructive disease.

“It’s one thing to show that the more plaque, the higher the risk,” Dr. Blankstein said. But “does the information ultimately lead to better outcomes? Do patients have fewer MIs or fewer deaths?” Several ongoing randomized trials are exploring these questions.

They include DANE-HEART (Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography for Primary Prevention), projected to enroll about 6,000 participants from the Copenhagen General Population Study cohort who have at least one CV risk factor, and SCOT-HEART 2 (second Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography for the Prevention of Myocardial Infarction), enrolling a similar cohort in Scotland.

The study was supported by grants from AP Møller og Hustru Chastine Mc-Kinney Møllers Fond, the Research Council of Rigshospitalet, and Danish Heart Foundation. Dr. Fuchs reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors can be found here. Dr. Blankstein recently disclosed serving as a consultant to Amgen, Caristo Diagnostics, Novartis, and Silence Therapeutics. Disclosures for Dr. McDermott and Dr. Newby, who are SCOT-HEART 2 investigators, can be found here.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Excess’ deaths surging, but why?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

“Excess deaths.” You’ve heard the phrase countless times by now. It is one of the myriad of previously esoteric epidemiology terms that the pandemic brought squarely into the zeitgeist.

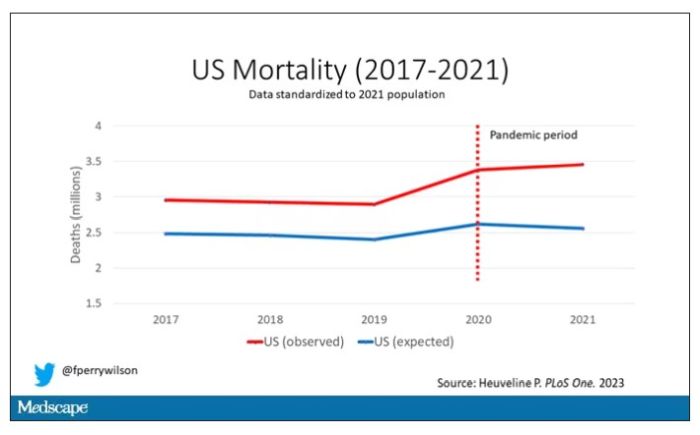

As a sort of standard candle of the performance of a state or a region or a country in terms of health care, it has a lot of utility – if for nothing more than Monday-morning quarterbacking. But this week, I want to dig in on the concept a bit because, according to a new study, the excess death gap between the United States and Western Europe has never been higher.

You might imagine that the best way to figure this out is for some group of intelligent people to review each death and decide, somehow, whether it was expected or not. But aside from being impractical, this would end up being somewhat subjective. That older person who died from pneumonia – was that an expected death? Could it have been avoided?

Rather, the calculation of excess mortality relies on large numbers and statistical inference to compare an expected number of deaths with those that are observed.

The difference is excess mortality, even if you can never be sure whether any particular death was expected or not.

As always, however, the devil is in the details. What data do you use to define the expected number of deaths?

There are options here. Probably the most straightforward analysis uses past data from the country of interest. You look at annual deaths over some historical period of time and compare those numbers with the rates today. Two issues need to be accounted for here: population growth – a larger population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust the historical population with current levels, and demographic shifts – an older or more male population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust for that as well.

But provided you take care of those factors, you can estimate fairly well how many deaths you can expect to see in any given period of time.

Still, you should see right away that excess mortality is a relative concept. If you think that, just perhaps, the United States has some systematic failure to deliver care that has been stable and persistent over time, you wouldn’t capture that failing in an excess mortality calculation that uses U.S. historical data as the baseline.

The best way to get around that is to use data from other countries, and that’s just what this article – a rare single-author piece by Patrick Heuveline – does, calculating excess deaths in the United States by standardizing our mortality rates to the five largest Western European countries: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

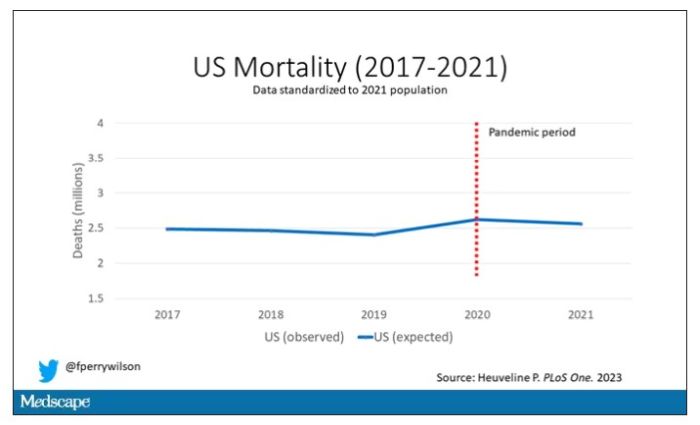

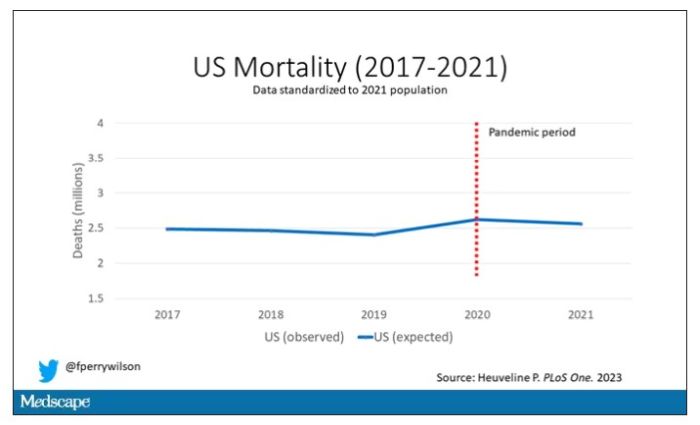

Controlling for the differences in the demographics of that European population, here is the expected number of deaths in the United States over the past 5 years.

Note that there is a small uptick in expected deaths in 2020, reflecting the pandemic, which returns to baseline levels by 2021. This is because that’s what happened in Europe; by 2021, the excess mortality due to COVID-19 was quite low.

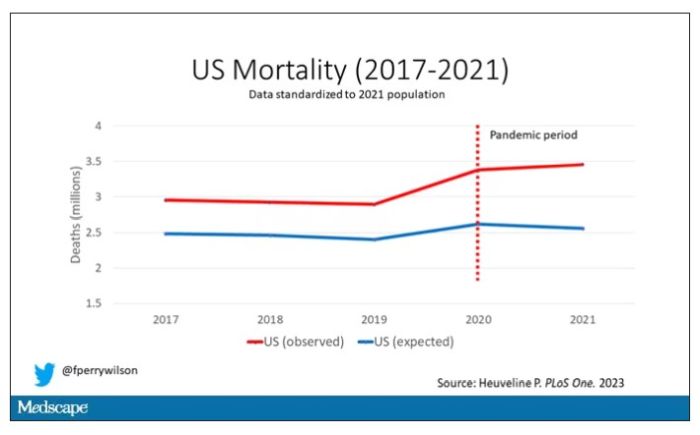

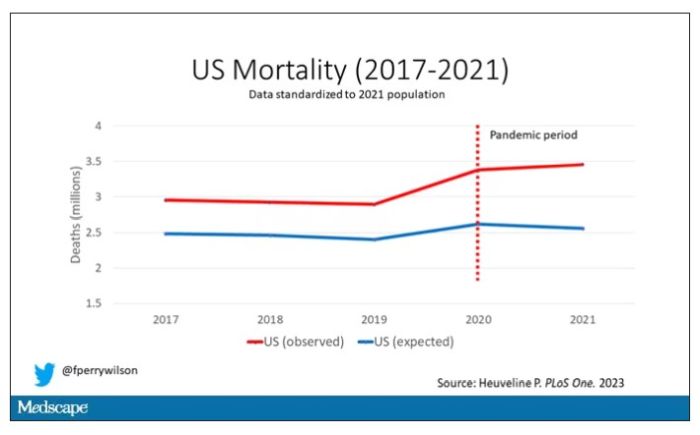

Here are the actual deaths in the US during that time.

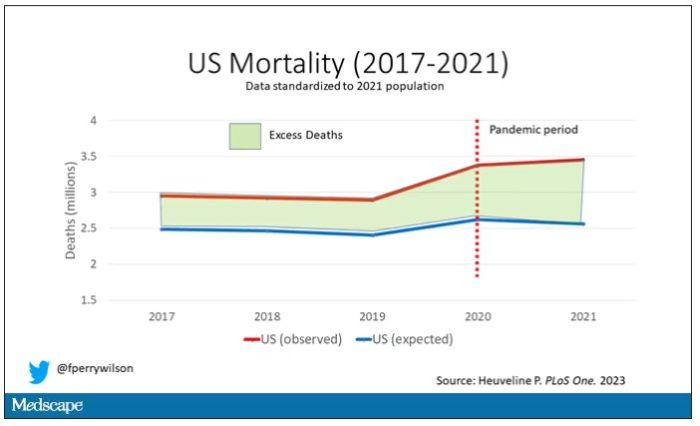

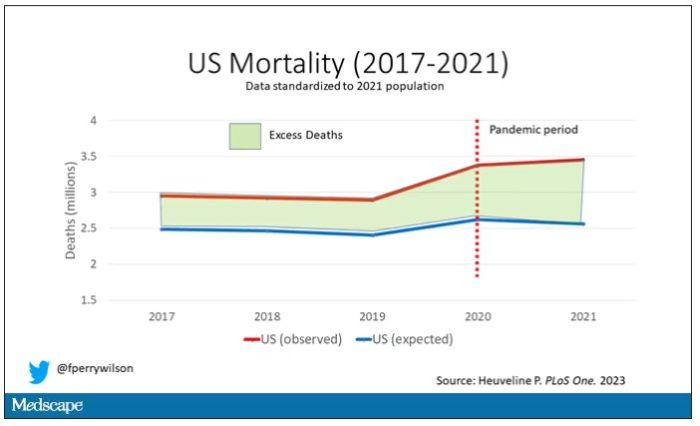

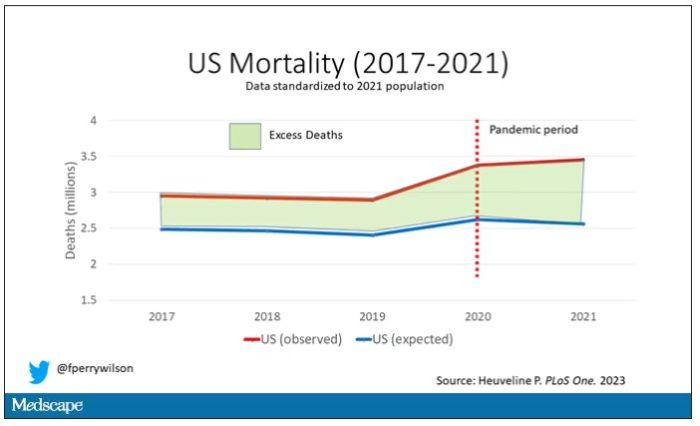

Highlighted here in green, then, is the excess mortality over time in the United States.

There are some fascinating and concerning findings here.

First of all, you can see that even before the pandemic, the United States has an excess mortality problem. This is not entirely a surprise; we’ve known that so-called “deaths of despair,” those due to alcohol abuse, drug overdoses, and suicide, are at an all-time high and tend to affect a “prime of life” population that would not otherwise be expected to die. In fact, fully 50% of the excess deaths in the United States occur in those between ages 15 and 64.

Excess deaths are also a concerning percentage of total deaths. In 2017, 17% of total deaths in the United States could be considered “excess.” In 2021, that number had doubled to 35%. Nearly 900,000 individuals in the United States died in 2021 who perhaps didn’t need to.

The obvious culprit to blame here is COVID, but COVID-associated excess deaths only explain about 50% of the excess we see in 2021. The rest reflect something even more concerning: a worsening of the failures of the past, perhaps exacerbated by the pandemic but not due to the virus itself.

Of course, we started this discussion acknowledging that the calculation of excess mortality is exquisitely dependent on how you model the expected number of deaths, and I’m sure some will take issue with the use of European numbers when applied to Americans. After all, Europe has, by and large, a robust public health service, socialized medicine, and healthcare that does not run the risk of bankrupting its citizens. How can we compare our outcomes to a place like that?

How indeed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven,Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

“Excess deaths.” You’ve heard the phrase countless times by now. It is one of the myriad of previously esoteric epidemiology terms that the pandemic brought squarely into the zeitgeist.

As a sort of standard candle of the performance of a state or a region or a country in terms of health care, it has a lot of utility – if for nothing more than Monday-morning quarterbacking. But this week, I want to dig in on the concept a bit because, according to a new study, the excess death gap between the United States and Western Europe has never been higher.

You might imagine that the best way to figure this out is for some group of intelligent people to review each death and decide, somehow, whether it was expected or not. But aside from being impractical, this would end up being somewhat subjective. That older person who died from pneumonia – was that an expected death? Could it have been avoided?

Rather, the calculation of excess mortality relies on large numbers and statistical inference to compare an expected number of deaths with those that are observed.

The difference is excess mortality, even if you can never be sure whether any particular death was expected or not.

As always, however, the devil is in the details. What data do you use to define the expected number of deaths?

There are options here. Probably the most straightforward analysis uses past data from the country of interest. You look at annual deaths over some historical period of time and compare those numbers with the rates today. Two issues need to be accounted for here: population growth – a larger population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust the historical population with current levels, and demographic shifts – an older or more male population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust for that as well.

But provided you take care of those factors, you can estimate fairly well how many deaths you can expect to see in any given period of time.

Still, you should see right away that excess mortality is a relative concept. If you think that, just perhaps, the United States has some systematic failure to deliver care that has been stable and persistent over time, you wouldn’t capture that failing in an excess mortality calculation that uses U.S. historical data as the baseline.

The best way to get around that is to use data from other countries, and that’s just what this article – a rare single-author piece by Patrick Heuveline – does, calculating excess deaths in the United States by standardizing our mortality rates to the five largest Western European countries: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

Controlling for the differences in the demographics of that European population, here is the expected number of deaths in the United States over the past 5 years.

Note that there is a small uptick in expected deaths in 2020, reflecting the pandemic, which returns to baseline levels by 2021. This is because that’s what happened in Europe; by 2021, the excess mortality due to COVID-19 was quite low.

Here are the actual deaths in the US during that time.

Highlighted here in green, then, is the excess mortality over time in the United States.

There are some fascinating and concerning findings here.

First of all, you can see that even before the pandemic, the United States has an excess mortality problem. This is not entirely a surprise; we’ve known that so-called “deaths of despair,” those due to alcohol abuse, drug overdoses, and suicide, are at an all-time high and tend to affect a “prime of life” population that would not otherwise be expected to die. In fact, fully 50% of the excess deaths in the United States occur in those between ages 15 and 64.

Excess deaths are also a concerning percentage of total deaths. In 2017, 17% of total deaths in the United States could be considered “excess.” In 2021, that number had doubled to 35%. Nearly 900,000 individuals in the United States died in 2021 who perhaps didn’t need to.

The obvious culprit to blame here is COVID, but COVID-associated excess deaths only explain about 50% of the excess we see in 2021. The rest reflect something even more concerning: a worsening of the failures of the past, perhaps exacerbated by the pandemic but not due to the virus itself.

Of course, we started this discussion acknowledging that the calculation of excess mortality is exquisitely dependent on how you model the expected number of deaths, and I’m sure some will take issue with the use of European numbers when applied to Americans. After all, Europe has, by and large, a robust public health service, socialized medicine, and healthcare that does not run the risk of bankrupting its citizens. How can we compare our outcomes to a place like that?

How indeed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven,Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

“Excess deaths.” You’ve heard the phrase countless times by now. It is one of the myriad of previously esoteric epidemiology terms that the pandemic brought squarely into the zeitgeist.

As a sort of standard candle of the performance of a state or a region or a country in terms of health care, it has a lot of utility – if for nothing more than Monday-morning quarterbacking. But this week, I want to dig in on the concept a bit because, according to a new study, the excess death gap between the United States and Western Europe has never been higher.

You might imagine that the best way to figure this out is for some group of intelligent people to review each death and decide, somehow, whether it was expected or not. But aside from being impractical, this would end up being somewhat subjective. That older person who died from pneumonia – was that an expected death? Could it have been avoided?

Rather, the calculation of excess mortality relies on large numbers and statistical inference to compare an expected number of deaths with those that are observed.

The difference is excess mortality, even if you can never be sure whether any particular death was expected or not.

As always, however, the devil is in the details. What data do you use to define the expected number of deaths?

There are options here. Probably the most straightforward analysis uses past data from the country of interest. You look at annual deaths over some historical period of time and compare those numbers with the rates today. Two issues need to be accounted for here: population growth – a larger population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust the historical population with current levels, and demographic shifts – an older or more male population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust for that as well.

But provided you take care of those factors, you can estimate fairly well how many deaths you can expect to see in any given period of time.

Still, you should see right away that excess mortality is a relative concept. If you think that, just perhaps, the United States has some systematic failure to deliver care that has been stable and persistent over time, you wouldn’t capture that failing in an excess mortality calculation that uses U.S. historical data as the baseline.

The best way to get around that is to use data from other countries, and that’s just what this article – a rare single-author piece by Patrick Heuveline – does, calculating excess deaths in the United States by standardizing our mortality rates to the five largest Western European countries: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

Controlling for the differences in the demographics of that European population, here is the expected number of deaths in the United States over the past 5 years.

Note that there is a small uptick in expected deaths in 2020, reflecting the pandemic, which returns to baseline levels by 2021. This is because that’s what happened in Europe; by 2021, the excess mortality due to COVID-19 was quite low.

Here are the actual deaths in the US during that time.

Highlighted here in green, then, is the excess mortality over time in the United States.

There are some fascinating and concerning findings here.

First of all, you can see that even before the pandemic, the United States has an excess mortality problem. This is not entirely a surprise; we’ve known that so-called “deaths of despair,” those due to alcohol abuse, drug overdoses, and suicide, are at an all-time high and tend to affect a “prime of life” population that would not otherwise be expected to die. In fact, fully 50% of the excess deaths in the United States occur in those between ages 15 and 64.

Excess deaths are also a concerning percentage of total deaths. In 2017, 17% of total deaths in the United States could be considered “excess.” In 2021, that number had doubled to 35%. Nearly 900,000 individuals in the United States died in 2021 who perhaps didn’t need to.

The obvious culprit to blame here is COVID, but COVID-associated excess deaths only explain about 50% of the excess we see in 2021. The rest reflect something even more concerning: a worsening of the failures of the past, perhaps exacerbated by the pandemic but not due to the virus itself.

Of course, we started this discussion acknowledging that the calculation of excess mortality is exquisitely dependent on how you model the expected number of deaths, and I’m sure some will take issue with the use of European numbers when applied to Americans. After all, Europe has, by and large, a robust public health service, socialized medicine, and healthcare that does not run the risk of bankrupting its citizens. How can we compare our outcomes to a place like that?

How indeed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven,Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Could a baby’s gut health be an early predictor of future type 1 diabetes?

Microbial biomarkers for type 1 diabetes may be present in infants as young as 12 months old, suggesting the potential to mitigate disease onset by nurturing a healthy gut microbiome early, show data from the Swedish general population.

“Our findings indicate that the gut of infants who go on to develop type 1 diabetes is notably different from healthy babies,” said Malin Bélteky, MD, from the Crown Princess Victoria’s Children’s Hospital, Linköping, Sweden, who jointly led the work, which was recently published in Diabetologia, alongside Patricia L. Milletich, PhD candidate, from the University of Florida, Gainesville.

“This discovery could be used to help identity infants at [the] highest risk of developing type 1 diabetes before or during the first stage of disease and could offer the opportunity to bolster a healthy gut microbiome to prevent the disease from becoming established,” added Dr. Bélteky.

Currently, beta-cell autoantibodies are used to predict disease, which are usually only identifiable between 9 and 36 months of age.

Marian Rewers, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics & medicine, University of Colorado, Denver, and principal investigator of The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study, welcomed the findings, saying it is a well-designed study from a strong group of investigators.

“While the effective number of cases was very small [n = 16], the results were apparently adjusted for multiple comparisons, and significant differences were noted in the microbiome of cases versus controls at 1 year of age. This was 12 years prior to the average age of type 1 diabetes diagnosis in the cases,” he said.

“The differences in diversity and abundances of specific bacteria need to be interpreted with caution; however, the study results are consistent with several previous reports,” he noted.

Differences in microbial diversity and function

Data were drawn from children participating in the longitudinal, general population All Babies In Southeast Sweden (ABIS) study. Microbiota from stool samples, taken at age 1 year, were sequenced and analyzed to establish diversity, abundance, and functional status of the component bacteria. Questionnaires were completed at birth and at 1 year of age, allowing for the study of environmental factors that might influence the microbiota or type 1 diabetes risk independently. Parent diaries provided information on pregnancy, nutrition, and lifestyle factors.

Of the cohort of 167 children who developed type 1 diabetes by 2020, stool samples were available for 16 of these participants, which were compared with 268 healthy controls. The microbiomes of the 16 infants who later developed type 1 diabetes were compared with 100 iterations of 32 matched control infants (matched by geographical region, siblings at birth, residence type, duration of breastfeeding, and month of stool collection) who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes by the age of 20.

Specific bacteria found in greater abundance in children who later developed type 1 diabetes, compared with those who didn’t, included Firmicutes (Enterococcus, Gemella, and Hungatella), as well as Bacteroides (Bacteroides and Porphyromonas), known to promote inflammation and be involved in the immune response.

Bacteria with greater abundance in children who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes, compared with those who did, were Firmicutes (Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, and Ruminococcaceae UBA1819, and Eubacterium). These species help maintain metabolic and immune health and produce butyrate, an important short-chain fatty acid that helps prevent inflammation and fuels the cells of the gut lining.

Alistipes were more abundant in infants who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes, and various abundances of Fusicatenibacter were the strongest factors for differentiating future type 1 diabetes, reported the researchers.

“Gut microbial biomarkers at 12 months would benefit the prediction opportunity well before the onset of multiple autoantibodies,” write the authors.

The youngest age at type 1 diabetes diagnosis was aged 1 year, 4 months, and the oldest was aged 21 years, 4 months. The mean age at diagnosis was 13.3 years.

The microbial differences found between infants who go on to develop type 1 diabetes and those who don’t also shed light on interactions between the developing immune system and short-chain fatty acid production and metabolism in childhood autoimmunity, write the authors.

Prior studies have found fewer short-chain fatty acid–producing microbiota in the gut of children with early-onset autoantibody development. This study confirmed these data, finding a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria (Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, Ruminococcaceae UBA1819, and Eubacterium) in infants who went on to develop type 1 diabetes. Likewise, a reduction in pyruvate fermentation was found in those infants with future disease.

According to coauthor Eric Triplett, PhD, from the University of Florida, Gainesville: “The autoimmune processes usually begin long before any clinical signs of disease appear, highlighting how differences in the makeup of the infant gut microbiome could shed important light on the complex interaction between the developing immune system, environmental exposures in childhood, and autoimmunity. Studies with much larger cohorts of prospectively traced individuals will be required to establish which are the strongest biomarkers and how effectively they can predict disease.”

The authors and Dr. Rewers have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Microbial biomarkers for type 1 diabetes may be present in infants as young as 12 months old, suggesting the potential to mitigate disease onset by nurturing a healthy gut microbiome early, show data from the Swedish general population.

“Our findings indicate that the gut of infants who go on to develop type 1 diabetes is notably different from healthy babies,” said Malin Bélteky, MD, from the Crown Princess Victoria’s Children’s Hospital, Linköping, Sweden, who jointly led the work, which was recently published in Diabetologia, alongside Patricia L. Milletich, PhD candidate, from the University of Florida, Gainesville.

“This discovery could be used to help identity infants at [the] highest risk of developing type 1 diabetes before or during the first stage of disease and could offer the opportunity to bolster a healthy gut microbiome to prevent the disease from becoming established,” added Dr. Bélteky.

Currently, beta-cell autoantibodies are used to predict disease, which are usually only identifiable between 9 and 36 months of age.

Marian Rewers, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics & medicine, University of Colorado, Denver, and principal investigator of The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study, welcomed the findings, saying it is a well-designed study from a strong group of investigators.

“While the effective number of cases was very small [n = 16], the results were apparently adjusted for multiple comparisons, and significant differences were noted in the microbiome of cases versus controls at 1 year of age. This was 12 years prior to the average age of type 1 diabetes diagnosis in the cases,” he said.

“The differences in diversity and abundances of specific bacteria need to be interpreted with caution; however, the study results are consistent with several previous reports,” he noted.

Differences in microbial diversity and function

Data were drawn from children participating in the longitudinal, general population All Babies In Southeast Sweden (ABIS) study. Microbiota from stool samples, taken at age 1 year, were sequenced and analyzed to establish diversity, abundance, and functional status of the component bacteria. Questionnaires were completed at birth and at 1 year of age, allowing for the study of environmental factors that might influence the microbiota or type 1 diabetes risk independently. Parent diaries provided information on pregnancy, nutrition, and lifestyle factors.

Of the cohort of 167 children who developed type 1 diabetes by 2020, stool samples were available for 16 of these participants, which were compared with 268 healthy controls. The microbiomes of the 16 infants who later developed type 1 diabetes were compared with 100 iterations of 32 matched control infants (matched by geographical region, siblings at birth, residence type, duration of breastfeeding, and month of stool collection) who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes by the age of 20.

Specific bacteria found in greater abundance in children who later developed type 1 diabetes, compared with those who didn’t, included Firmicutes (Enterococcus, Gemella, and Hungatella), as well as Bacteroides (Bacteroides and Porphyromonas), known to promote inflammation and be involved in the immune response.

Bacteria with greater abundance in children who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes, compared with those who did, were Firmicutes (Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, and Ruminococcaceae UBA1819, and Eubacterium). These species help maintain metabolic and immune health and produce butyrate, an important short-chain fatty acid that helps prevent inflammation and fuels the cells of the gut lining.

Alistipes were more abundant in infants who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes, and various abundances of Fusicatenibacter were the strongest factors for differentiating future type 1 diabetes, reported the researchers.

“Gut microbial biomarkers at 12 months would benefit the prediction opportunity well before the onset of multiple autoantibodies,” write the authors.

The youngest age at type 1 diabetes diagnosis was aged 1 year, 4 months, and the oldest was aged 21 years, 4 months. The mean age at diagnosis was 13.3 years.

The microbial differences found between infants who go on to develop type 1 diabetes and those who don’t also shed light on interactions between the developing immune system and short-chain fatty acid production and metabolism in childhood autoimmunity, write the authors.

Prior studies have found fewer short-chain fatty acid–producing microbiota in the gut of children with early-onset autoantibody development. This study confirmed these data, finding a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria (Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, Ruminococcaceae UBA1819, and Eubacterium) in infants who went on to develop type 1 diabetes. Likewise, a reduction in pyruvate fermentation was found in those infants with future disease.

According to coauthor Eric Triplett, PhD, from the University of Florida, Gainesville: “The autoimmune processes usually begin long before any clinical signs of disease appear, highlighting how differences in the makeup of the infant gut microbiome could shed important light on the complex interaction between the developing immune system, environmental exposures in childhood, and autoimmunity. Studies with much larger cohorts of prospectively traced individuals will be required to establish which are the strongest biomarkers and how effectively they can predict disease.”

The authors and Dr. Rewers have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Microbial biomarkers for type 1 diabetes may be present in infants as young as 12 months old, suggesting the potential to mitigate disease onset by nurturing a healthy gut microbiome early, show data from the Swedish general population.

“Our findings indicate that the gut of infants who go on to develop type 1 diabetes is notably different from healthy babies,” said Malin Bélteky, MD, from the Crown Princess Victoria’s Children’s Hospital, Linköping, Sweden, who jointly led the work, which was recently published in Diabetologia, alongside Patricia L. Milletich, PhD candidate, from the University of Florida, Gainesville.

“This discovery could be used to help identity infants at [the] highest risk of developing type 1 diabetes before or during the first stage of disease and could offer the opportunity to bolster a healthy gut microbiome to prevent the disease from becoming established,” added Dr. Bélteky.

Currently, beta-cell autoantibodies are used to predict disease, which are usually only identifiable between 9 and 36 months of age.

Marian Rewers, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics & medicine, University of Colorado, Denver, and principal investigator of The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study, welcomed the findings, saying it is a well-designed study from a strong group of investigators.

“While the effective number of cases was very small [n = 16], the results were apparently adjusted for multiple comparisons, and significant differences were noted in the microbiome of cases versus controls at 1 year of age. This was 12 years prior to the average age of type 1 diabetes diagnosis in the cases,” he said.

“The differences in diversity and abundances of specific bacteria need to be interpreted with caution; however, the study results are consistent with several previous reports,” he noted.

Differences in microbial diversity and function

Data were drawn from children participating in the longitudinal, general population All Babies In Southeast Sweden (ABIS) study. Microbiota from stool samples, taken at age 1 year, were sequenced and analyzed to establish diversity, abundance, and functional status of the component bacteria. Questionnaires were completed at birth and at 1 year of age, allowing for the study of environmental factors that might influence the microbiota or type 1 diabetes risk independently. Parent diaries provided information on pregnancy, nutrition, and lifestyle factors.

Of the cohort of 167 children who developed type 1 diabetes by 2020, stool samples were available for 16 of these participants, which were compared with 268 healthy controls. The microbiomes of the 16 infants who later developed type 1 diabetes were compared with 100 iterations of 32 matched control infants (matched by geographical region, siblings at birth, residence type, duration of breastfeeding, and month of stool collection) who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes by the age of 20.

Specific bacteria found in greater abundance in children who later developed type 1 diabetes, compared with those who didn’t, included Firmicutes (Enterococcus, Gemella, and Hungatella), as well as Bacteroides (Bacteroides and Porphyromonas), known to promote inflammation and be involved in the immune response.

Bacteria with greater abundance in children who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes, compared with those who did, were Firmicutes (Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, and Ruminococcaceae UBA1819, and Eubacterium). These species help maintain metabolic and immune health and produce butyrate, an important short-chain fatty acid that helps prevent inflammation and fuels the cells of the gut lining.

Alistipes were more abundant in infants who didn’t develop type 1 diabetes, and various abundances of Fusicatenibacter were the strongest factors for differentiating future type 1 diabetes, reported the researchers.

“Gut microbial biomarkers at 12 months would benefit the prediction opportunity well before the onset of multiple autoantibodies,” write the authors.

The youngest age at type 1 diabetes diagnosis was aged 1 year, 4 months, and the oldest was aged 21 years, 4 months. The mean age at diagnosis was 13.3 years.

The microbial differences found between infants who go on to develop type 1 diabetes and those who don’t also shed light on interactions between the developing immune system and short-chain fatty acid production and metabolism in childhood autoimmunity, write the authors.

Prior studies have found fewer short-chain fatty acid–producing microbiota in the gut of children with early-onset autoantibody development. This study confirmed these data, finding a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria (Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, Ruminococcaceae UBA1819, and Eubacterium) in infants who went on to develop type 1 diabetes. Likewise, a reduction in pyruvate fermentation was found in those infants with future disease.

According to coauthor Eric Triplett, PhD, from the University of Florida, Gainesville: “The autoimmune processes usually begin long before any clinical signs of disease appear, highlighting how differences in the makeup of the infant gut microbiome could shed important light on the complex interaction between the developing immune system, environmental exposures in childhood, and autoimmunity. Studies with much larger cohorts of prospectively traced individuals will be required to establish which are the strongest biomarkers and how effectively they can predict disease.”

The authors and Dr. Rewers have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sweaty treatment for social anxiety could pass the sniff test

Getting sweet on sweat

Are you the sort of person who struggles in social situations? Have the past 3 years been a secret respite from the terror and exhaustion of meeting new people? We understand your plight. People kind of suck. And you don’t have to look far to be reminded of it.

Unfortunately, on occasion we all have to interact with other human beings. If you suffer from social anxiety, this is not a fun thing to do. But new research indicates that there may be a way to alleviate the stress for those with social anxiety: armpits.

Specifically, sweat from the armpits of other people. Yes, this means a group of scientists gathered up some volunteers and collected their armpit sweat while the volunteers watched a variety of movies (horror, comedy, romance, etc.). Our condolences to the poor unpaid interns tasked with gathering the sweat.

Once they had their precious new medicine, the researchers took a group of women and administered a round of mindfulness therapy. Some of the participants then received the various sweats, while the rest were forced to smell only clean air. (The horror!) Lo and behold, the sweat groups had their anxiety scores reduced by about 40% after their therapy, compared with just 17% in the control group.

The researchers also found that the source of the sweat didn’t matter. Their study subjects responded the same to sweat excreted during a scary movie as they did to sweat from a comedy, a result that surprised the researchers. They suggested chemosignals in the sweat may affect the treatment response and advised further research. Which means more sweat collection! They plan on testing emotionally neutral movies next time, and if we can make a humble suggestion, they also should try the sweatiest movies.

Before the Food and Drug Administration can approve armpit sweat as a treatment for social anxiety, we have some advice for those shut-in introverts out there. Next time you have to interact with rabid extroverts, instead of shaking their hands, walk up to them and take a deep whiff of their armpits. Establish dominance. Someone will feel awkward, and science has proved it won’t be you.

The puff that vaccinates

Ever been shot with a Nerf gun or hit with a foam pool tube? More annoying than painful, right? If we asked if you’d rather get pelted with one of those than receive a traditional vaccine injection, you would choose the former. Maybe someday you actually will.

During the boredom of the early pandemic lockdown, Jeremiah Gassensmith, PhD, of the department of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Texas, Dallas, ordered a compressed gas–powered jet injection system to fool around with at home. Hey, who didn’t? Anyway, when it was time to go back to the lab he handed it over to one of his grad students, Yalini Wijesundara, and asked her to see what could be done with it.

In her tinkering she found that the jet injector could deliver metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that can hold a bunch of different materials, like proteins and nucleic acids, through the skin.

Thus the “MOF-Jet” was born!

Jet injectors are nothing new, but they hurt. The MOF-Jet, however, is practically painless and cheaper than the gene guns that veterinarians use to inject biological cargo attached to the surface of a metal microparticle.

Changing the carrier gas also changes the time needed to break down the MOF and thus alters delivery of the drug inside. “If you shoot it with carbon dioxide, it will release its cargo faster within cells; if you use regular air, it will take 4 or 5 days,” Ms. Wijesundara explained in a written statement. That means the same drug could be released over different timescales without changing its formulation.

While testing on onion cells and mice, Ms. Wijesundara noted that it was as easy as “pointing and shooting” to distribute the puff of gas into the cells. A saving grace to those with needle anxiety. Not that we would know anything about needle anxiety.

More testing needs to be done before bringing this technology to human use, obviously, but we’re looking forward to saying goodbye to that dreaded prick and hello to a puff.

Your hippocampus is showing

Brain anatomy is one of the many, many things that’s not really our thing, but we do know a cool picture when we see one. Case in point: The image just below, which happens to be a full-scale, single-cell resolution model of the CA1 region of the hippocampus that “replicates the structure and architecture of the area, along with the position and relative connectivity of the neurons,” according to a statement from the Human Brain Project.

“We have performed a data mining operation on high resolution images of the human hippocampus, obtained from the BigBrain database. The position of individual neurons has been derived from a detailed analysis of these images,” said senior author Michele Migliore, PhD, of the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Biophysics in Palermo.

Yes, he did say BigBrain database. BigBrain is – we checked and it’s definitely not this – a 3D model of a brain that was sectioned into 7,404 slices just 20 micrometers thick and then scanned by MRI. Digital reconstruction of those slices was done by supercomputer and the results are now available for analysis.

Dr. Migliore and his associates developed an image-processing algorithm to obtain neuronal positioning distribution and an algorithm to generate neuronal connectivity by approximating the shapes of dendrites and axons. (Our brains are starting to hurt just trying to write this.) “Some fit into narrow cones, others have a broad complex extension that can be approximated by dedicated geometrical volumes, and the connectivity to nearby neurons changes accordingly,” explained lead author Daniela Gandolfi of the University of Modena (Italy) and Reggio Emilia.

The investigators have made their dataset and the extraction methodology available on the EBRAINS platform and through the Human Brain Project and are moving on to other brain regions. And then, once everyone can find their way in and around the old gray matter, it should bring an end to conversations like this, which no doubt occur between male and female neuroscientists every day:

“Arnold, I think we’re lost.”

“Don’t worry, Bev, I know where I’m going.”

“Stop and ask this lady for directions.”

“I said I can find it.”

“Just ask her.”

“Fine. Excuse me, ma’am, can you tell us how to get to the corpora quadrigemina from here?

Getting sweet on sweat

Are you the sort of person who struggles in social situations? Have the past 3 years been a secret respite from the terror and exhaustion of meeting new people? We understand your plight. People kind of suck. And you don’t have to look far to be reminded of it.

Unfortunately, on occasion we all have to interact with other human beings. If you suffer from social anxiety, this is not a fun thing to do. But new research indicates that there may be a way to alleviate the stress for those with social anxiety: armpits.

Specifically, sweat from the armpits of other people. Yes, this means a group of scientists gathered up some volunteers and collected their armpit sweat while the volunteers watched a variety of movies (horror, comedy, romance, etc.). Our condolences to the poor unpaid interns tasked with gathering the sweat.

Once they had their precious new medicine, the researchers took a group of women and administered a round of mindfulness therapy. Some of the participants then received the various sweats, while the rest were forced to smell only clean air. (The horror!) Lo and behold, the sweat groups had their anxiety scores reduced by about 40% after their therapy, compared with just 17% in the control group.

The researchers also found that the source of the sweat didn’t matter. Their study subjects responded the same to sweat excreted during a scary movie as they did to sweat from a comedy, a result that surprised the researchers. They suggested chemosignals in the sweat may affect the treatment response and advised further research. Which means more sweat collection! They plan on testing emotionally neutral movies next time, and if we can make a humble suggestion, they also should try the sweatiest movies.

Before the Food and Drug Administration can approve armpit sweat as a treatment for social anxiety, we have some advice for those shut-in introverts out there. Next time you have to interact with rabid extroverts, instead of shaking their hands, walk up to them and take a deep whiff of their armpits. Establish dominance. Someone will feel awkward, and science has proved it won’t be you.

The puff that vaccinates

Ever been shot with a Nerf gun or hit with a foam pool tube? More annoying than painful, right? If we asked if you’d rather get pelted with one of those than receive a traditional vaccine injection, you would choose the former. Maybe someday you actually will.

During the boredom of the early pandemic lockdown, Jeremiah Gassensmith, PhD, of the department of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Texas, Dallas, ordered a compressed gas–powered jet injection system to fool around with at home. Hey, who didn’t? Anyway, when it was time to go back to the lab he handed it over to one of his grad students, Yalini Wijesundara, and asked her to see what could be done with it.

In her tinkering she found that the jet injector could deliver metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that can hold a bunch of different materials, like proteins and nucleic acids, through the skin.

Thus the “MOF-Jet” was born!

Jet injectors are nothing new, but they hurt. The MOF-Jet, however, is practically painless and cheaper than the gene guns that veterinarians use to inject biological cargo attached to the surface of a metal microparticle.

Changing the carrier gas also changes the time needed to break down the MOF and thus alters delivery of the drug inside. “If you shoot it with carbon dioxide, it will release its cargo faster within cells; if you use regular air, it will take 4 or 5 days,” Ms. Wijesundara explained in a written statement. That means the same drug could be released over different timescales without changing its formulation.

While testing on onion cells and mice, Ms. Wijesundara noted that it was as easy as “pointing and shooting” to distribute the puff of gas into the cells. A saving grace to those with needle anxiety. Not that we would know anything about needle anxiety.

More testing needs to be done before bringing this technology to human use, obviously, but we’re looking forward to saying goodbye to that dreaded prick and hello to a puff.

Your hippocampus is showing

Brain anatomy is one of the many, many things that’s not really our thing, but we do know a cool picture when we see one. Case in point: The image just below, which happens to be a full-scale, single-cell resolution model of the CA1 region of the hippocampus that “replicates the structure and architecture of the area, along with the position and relative connectivity of the neurons,” according to a statement from the Human Brain Project.

“We have performed a data mining operation on high resolution images of the human hippocampus, obtained from the BigBrain database. The position of individual neurons has been derived from a detailed analysis of these images,” said senior author Michele Migliore, PhD, of the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Biophysics in Palermo.

Yes, he did say BigBrain database. BigBrain is – we checked and it’s definitely not this – a 3D model of a brain that was sectioned into 7,404 slices just 20 micrometers thick and then scanned by MRI. Digital reconstruction of those slices was done by supercomputer and the results are now available for analysis.

Dr. Migliore and his associates developed an image-processing algorithm to obtain neuronal positioning distribution and an algorithm to generate neuronal connectivity by approximating the shapes of dendrites and axons. (Our brains are starting to hurt just trying to write this.) “Some fit into narrow cones, others have a broad complex extension that can be approximated by dedicated geometrical volumes, and the connectivity to nearby neurons changes accordingly,” explained lead author Daniela Gandolfi of the University of Modena (Italy) and Reggio Emilia.

The investigators have made their dataset and the extraction methodology available on the EBRAINS platform and through the Human Brain Project and are moving on to other brain regions. And then, once everyone can find their way in and around the old gray matter, it should bring an end to conversations like this, which no doubt occur between male and female neuroscientists every day:

“Arnold, I think we’re lost.”

“Don’t worry, Bev, I know where I’m going.”

“Stop and ask this lady for directions.”

“I said I can find it.”

“Just ask her.”

“Fine. Excuse me, ma’am, can you tell us how to get to the corpora quadrigemina from here?

Getting sweet on sweat

Are you the sort of person who struggles in social situations? Have the past 3 years been a secret respite from the terror and exhaustion of meeting new people? We understand your plight. People kind of suck. And you don’t have to look far to be reminded of it.

Unfortunately, on occasion we all have to interact with other human beings. If you suffer from social anxiety, this is not a fun thing to do. But new research indicates that there may be a way to alleviate the stress for those with social anxiety: armpits.

Specifically, sweat from the armpits of other people. Yes, this means a group of scientists gathered up some volunteers and collected their armpit sweat while the volunteers watched a variety of movies (horror, comedy, romance, etc.). Our condolences to the poor unpaid interns tasked with gathering the sweat.

Once they had their precious new medicine, the researchers took a group of women and administered a round of mindfulness therapy. Some of the participants then received the various sweats, while the rest were forced to smell only clean air. (The horror!) Lo and behold, the sweat groups had their anxiety scores reduced by about 40% after their therapy, compared with just 17% in the control group.

The researchers also found that the source of the sweat didn’t matter. Their study subjects responded the same to sweat excreted during a scary movie as they did to sweat from a comedy, a result that surprised the researchers. They suggested chemosignals in the sweat may affect the treatment response and advised further research. Which means more sweat collection! They plan on testing emotionally neutral movies next time, and if we can make a humble suggestion, they also should try the sweatiest movies.

Before the Food and Drug Administration can approve armpit sweat as a treatment for social anxiety, we have some advice for those shut-in introverts out there. Next time you have to interact with rabid extroverts, instead of shaking their hands, walk up to them and take a deep whiff of their armpits. Establish dominance. Someone will feel awkward, and science has proved it won’t be you.

The puff that vaccinates

Ever been shot with a Nerf gun or hit with a foam pool tube? More annoying than painful, right? If we asked if you’d rather get pelted with one of those than receive a traditional vaccine injection, you would choose the former. Maybe someday you actually will.

During the boredom of the early pandemic lockdown, Jeremiah Gassensmith, PhD, of the department of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Texas, Dallas, ordered a compressed gas–powered jet injection system to fool around with at home. Hey, who didn’t? Anyway, when it was time to go back to the lab he handed it over to one of his grad students, Yalini Wijesundara, and asked her to see what could be done with it.

In her tinkering she found that the jet injector could deliver metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that can hold a bunch of different materials, like proteins and nucleic acids, through the skin.

Thus the “MOF-Jet” was born!

Jet injectors are nothing new, but they hurt. The MOF-Jet, however, is practically painless and cheaper than the gene guns that veterinarians use to inject biological cargo attached to the surface of a metal microparticle.

Changing the carrier gas also changes the time needed to break down the MOF and thus alters delivery of the drug inside. “If you shoot it with carbon dioxide, it will release its cargo faster within cells; if you use regular air, it will take 4 or 5 days,” Ms. Wijesundara explained in a written statement. That means the same drug could be released over different timescales without changing its formulation.

While testing on onion cells and mice, Ms. Wijesundara noted that it was as easy as “pointing and shooting” to distribute the puff of gas into the cells. A saving grace to those with needle anxiety. Not that we would know anything about needle anxiety.

More testing needs to be done before bringing this technology to human use, obviously, but we’re looking forward to saying goodbye to that dreaded prick and hello to a puff.

Your hippocampus is showing

Brain anatomy is one of the many, many things that’s not really our thing, but we do know a cool picture when we see one. Case in point: The image just below, which happens to be a full-scale, single-cell resolution model of the CA1 region of the hippocampus that “replicates the structure and architecture of the area, along with the position and relative connectivity of the neurons,” according to a statement from the Human Brain Project.

“We have performed a data mining operation on high resolution images of the human hippocampus, obtained from the BigBrain database. The position of individual neurons has been derived from a detailed analysis of these images,” said senior author Michele Migliore, PhD, of the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Biophysics in Palermo.

Yes, he did say BigBrain database. BigBrain is – we checked and it’s definitely not this – a 3D model of a brain that was sectioned into 7,404 slices just 20 micrometers thick and then scanned by MRI. Digital reconstruction of those slices was done by supercomputer and the results are now available for analysis.

Dr. Migliore and his associates developed an image-processing algorithm to obtain neuronal positioning distribution and an algorithm to generate neuronal connectivity by approximating the shapes of dendrites and axons. (Our brains are starting to hurt just trying to write this.) “Some fit into narrow cones, others have a broad complex extension that can be approximated by dedicated geometrical volumes, and the connectivity to nearby neurons changes accordingly,” explained lead author Daniela Gandolfi of the University of Modena (Italy) and Reggio Emilia.

The investigators have made their dataset and the extraction methodology available on the EBRAINS platform and through the Human Brain Project and are moving on to other brain regions. And then, once everyone can find their way in and around the old gray matter, it should bring an end to conversations like this, which no doubt occur between male and female neuroscientists every day:

“Arnold, I think we’re lost.”

“Don’t worry, Bev, I know where I’m going.”

“Stop and ask this lady for directions.”

“I said I can find it.”

“Just ask her.”

“Fine. Excuse me, ma’am, can you tell us how to get to the corpora quadrigemina from here?

Plant-based diets not always healthy; quality is key

The prospective cohort study used data from more than 120,000 middle-aged adults followed for over 10 years in the UK Biobank. Those who consumed a healthful plant-based diet – with higher amounts of foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and nuts – and lower intakes of animal products, sugary drinks, and refined grains had a 16% lower risk of dying during follow-up, compared with those with the lowest intakes of the healthful plant-based foods.

By contrast, an unhealthy plant-based diet was associated with a 23% higher total mortality risk.

“Not all plant-based diets are created equally. Our data provide evidence to support the notion that for health benefits the plant-based sources need to be whole grains, fruits and vegetables, legumes, nuts, etc., rather than processed plant-based foods,” study coauthor Aedín Cassidy, PhD, of Queen’s University, Belfast, Northern Ireland, said in an interview.

She added: “We do not necessarily need to radically shift diets to vegan or vegetarian regimens, but rather to switch proportions on the plate to incorporate more healthful plant-based foods, fish, and leaner cuts of meat into our habitual diet. This would have benefits for both individual health and planetary health.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open by Alysha S. Thompson, MSc, also at Queen’s University, and colleagues.

High- vs. low-quality plant-based diets linked to better outcomes

The UK Biobank is a population-based, prospective study that included more than 500,000 participants aged 40-69 years at the time of recruitment between 2006 and 2010 at 22 centers in England, Scotland, and Wales. The current study included 126,395 individuals; slightly over half (55.9%) are women.

Food intake data were collected for at least two 24-hour periods to create both “healthful” and “unhealthful” plant-based diet indexes (PDIs). These included 17 food groups: whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes and vegetarian protein alternatives, tea and coffee, fruit juices, refined grains, potatoes, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweets and desserts, animal fat, dairy, eggs, fish or seafood, meat, and miscellaneous animal-derived foods. Data on oils weren’t available.

Higher scores on the healthful PDI and unhealthful PDI were scored positively or negatively based on quantities of those foods consumed.

Participants were then ranked in quartiles for portions of each food group and assigned scores between 2 (lowest-intake category) and 5 (highest).

During a follow-up of 10.6-12.2 years, there were 698 deaths attributed to cardiovascular disease, 3,275 deaths caused by cancer, 6,890 individuals who experienced a cardiovascular incident, and 8,939 with incident cancer.

Another 4,751 experienced an incident fracture, which was evaluated because of the concern that diets low in animal protein might lead to insufficient vitamin B and calcium intake.

After adjustment for confounding factors, the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality in individuals with the highest healthful PDI score quartile compared with the lowest quartile was 0.84.

At the same time, the HR for all-cause mortality for those with the highest versus lowest unhealthful PDI scores was 1.23, and for cancer-related mortality was 1.19. All were statistically significant (P = .004).

Similarly, greater healthy plant-based diet adherence was associated with a significantly lower risk of being diagnosed with any cancer (HR, 0.93; P = .03), while higher unhealthful PDI scores yielded a higher risk (HR, 1.10; P = .004).

Moreover, higher healthy PDI scores were associated with lower risks for total cardiovascular incident risks (HR, 0.92; P = .007), as well as for the individual events of ischemic stroke (HR, 0.84; P = .08) and MI (HR, 0.86; P = .004). Higher unhealthy PDI scores were similarly associated with greater risks for those outcomes, with an overall HR of 1.21 (P = .004).

No associations were found between either healthful PDI or unhealthful PDI and total or site-specific fracture risk.

And because 91.3% of the UK Biobank study population was White, “future studies among more racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse populations are needed to assess the risk of major chronic disease in relation to [plant-based diets],” the authors wrote.

Dr. Cassidy and Ms. Thompson reported no relevant financial relationships.