User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Patients who refuse to wear masks: Responses that won’t get you sued

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children rarely transmit SARS-CoV-2 within households

“Unlike with other viral respiratory infections, children do not seem to be a major vector of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, with most pediatric cases described inside familial clusters and no documentation of child-to-child or child-to-adult transmission,” said Klara M. Posfay-Barbe, MD, of the University of Geneva, Switzerland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed data from all COVID-19 patients younger than 16 years who were identified between March 10, 2020, and April 10, 2020, through a hospital surveillance network. Parents and household contacts were called for contact tracing.

In 31 of 39 (79%) households, at least one adult family member had a suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection before onset of symptoms in the child. These findings support data from previous studies suggesting that children mainly become infected from adult family members rather than transmitting the virus to them, the researchers said

In only 3 of 39 (8%) households was the study child the first to develop symptoms. “Surprisingly, in 33% of households, symptomatic HHCs [household contacts] tested negative despite belonging to a familial cluster with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, suggesting an underreporting of cases,” Dr. Posfay-Barbe and associates noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including potential underreporting of cases because those with mild or atypical presentations may not have sought medical care, and the inability to confirm child-to-adult transmission. The results were strengthened by the extensive contact tracing and very few individuals lost to follow-up, they said; however, more diagnostic screening and contact tracing are needed to improve understanding of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they concluded.

Resolving the issue of how much children contribute to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is essential to making informed decisions about public health, including how to structure schools and child-care facility reopening, Benjamin Lee, MD, and William V. Raszka Jr., MD, both of the University of Vermont, Burlington, said in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds/2020-004879).

The data in the current study support other studies of transmission among household contacts in China suggesting that, in most cases of childhood infections, “the child was not the source of infection and that children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them,” they wrote.

In addition, the limited data on transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children outside of the household show few cases of secondary infection from children identified with SARS-CoV-2 in school settings in studies from France and Australia, Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka noted.

the editorialists wrote. “This would be another manner by which SARS-CoV2 differs drastically from influenza, for which school-based transmission is well recognized as a significant driver of epidemic disease and forms the basis for most evidence regarding school closures as public health strategy.”

“Therefore, serious consideration should be paid toward strategies that allow schools to remain open, even during periods of COVID-19 spread,” the editorialists concluded. “In doing so, we could minimize the potentially profound adverse social, developmental, and health costs that our children will continue to suffer until an effective treatment or vaccine can be developed and distributed or, failing that, until we reach herd immunity,” Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka emphasized.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Posfay-Barbe KM et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1576.

“Unlike with other viral respiratory infections, children do not seem to be a major vector of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, with most pediatric cases described inside familial clusters and no documentation of child-to-child or child-to-adult transmission,” said Klara M. Posfay-Barbe, MD, of the University of Geneva, Switzerland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed data from all COVID-19 patients younger than 16 years who were identified between March 10, 2020, and April 10, 2020, through a hospital surveillance network. Parents and household contacts were called for contact tracing.

In 31 of 39 (79%) households, at least one adult family member had a suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection before onset of symptoms in the child. These findings support data from previous studies suggesting that children mainly become infected from adult family members rather than transmitting the virus to them, the researchers said

In only 3 of 39 (8%) households was the study child the first to develop symptoms. “Surprisingly, in 33% of households, symptomatic HHCs [household contacts] tested negative despite belonging to a familial cluster with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, suggesting an underreporting of cases,” Dr. Posfay-Barbe and associates noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including potential underreporting of cases because those with mild or atypical presentations may not have sought medical care, and the inability to confirm child-to-adult transmission. The results were strengthened by the extensive contact tracing and very few individuals lost to follow-up, they said; however, more diagnostic screening and contact tracing are needed to improve understanding of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they concluded.

Resolving the issue of how much children contribute to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is essential to making informed decisions about public health, including how to structure schools and child-care facility reopening, Benjamin Lee, MD, and William V. Raszka Jr., MD, both of the University of Vermont, Burlington, said in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds/2020-004879).

The data in the current study support other studies of transmission among household contacts in China suggesting that, in most cases of childhood infections, “the child was not the source of infection and that children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them,” they wrote.

In addition, the limited data on transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children outside of the household show few cases of secondary infection from children identified with SARS-CoV-2 in school settings in studies from France and Australia, Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka noted.

the editorialists wrote. “This would be another manner by which SARS-CoV2 differs drastically from influenza, for which school-based transmission is well recognized as a significant driver of epidemic disease and forms the basis for most evidence regarding school closures as public health strategy.”

“Therefore, serious consideration should be paid toward strategies that allow schools to remain open, even during periods of COVID-19 spread,” the editorialists concluded. “In doing so, we could minimize the potentially profound adverse social, developmental, and health costs that our children will continue to suffer until an effective treatment or vaccine can be developed and distributed or, failing that, until we reach herd immunity,” Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka emphasized.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Posfay-Barbe KM et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1576.

“Unlike with other viral respiratory infections, children do not seem to be a major vector of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, with most pediatric cases described inside familial clusters and no documentation of child-to-child or child-to-adult transmission,” said Klara M. Posfay-Barbe, MD, of the University of Geneva, Switzerland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed data from all COVID-19 patients younger than 16 years who were identified between March 10, 2020, and April 10, 2020, through a hospital surveillance network. Parents and household contacts were called for contact tracing.

In 31 of 39 (79%) households, at least one adult family member had a suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection before onset of symptoms in the child. These findings support data from previous studies suggesting that children mainly become infected from adult family members rather than transmitting the virus to them, the researchers said

In only 3 of 39 (8%) households was the study child the first to develop symptoms. “Surprisingly, in 33% of households, symptomatic HHCs [household contacts] tested negative despite belonging to a familial cluster with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, suggesting an underreporting of cases,” Dr. Posfay-Barbe and associates noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including potential underreporting of cases because those with mild or atypical presentations may not have sought medical care, and the inability to confirm child-to-adult transmission. The results were strengthened by the extensive contact tracing and very few individuals lost to follow-up, they said; however, more diagnostic screening and contact tracing are needed to improve understanding of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2, they concluded.

Resolving the issue of how much children contribute to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is essential to making informed decisions about public health, including how to structure schools and child-care facility reopening, Benjamin Lee, MD, and William V. Raszka Jr., MD, both of the University of Vermont, Burlington, said in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds/2020-004879).

The data in the current study support other studies of transmission among household contacts in China suggesting that, in most cases of childhood infections, “the child was not the source of infection and that children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them,” they wrote.

In addition, the limited data on transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children outside of the household show few cases of secondary infection from children identified with SARS-CoV-2 in school settings in studies from France and Australia, Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka noted.

the editorialists wrote. “This would be another manner by which SARS-CoV2 differs drastically from influenza, for which school-based transmission is well recognized as a significant driver of epidemic disease and forms the basis for most evidence regarding school closures as public health strategy.”

“Therefore, serious consideration should be paid toward strategies that allow schools to remain open, even during periods of COVID-19 spread,” the editorialists concluded. “In doing so, we could minimize the potentially profound adverse social, developmental, and health costs that our children will continue to suffer until an effective treatment or vaccine can be developed and distributed or, failing that, until we reach herd immunity,” Dr. Lee and Dr. Raszka emphasized.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Posfay-Barbe KM et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1576.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Perioperative sleep medicine: The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been recognized to increase the risk of adverse cardiopulmonary perioperative outcomes for some time now.1 An ever growing body of literature supports this finding,2 including a large prospective study published in 2019 highlighting the significant risk of poor cardiac-related postoperative outcomes in patients with unrecognized OSA.3 As the majority of patients presenting for elective surgery with OSA will not be diagnosed at the time of presentation,3,4 many centers have developed preoperative screening programs to identify these patients, though the practice is not universal and a desire for better guidance is needed.5 In addition, best practices for patients with suspected or known OSA undergoing surgery have been a matter of debate. Out of these concerns, the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine (SASM) was formed over 10 years ago to promote interdisciplinary communication, education, and research into matters common to anesthesia and sleep.

Pulmonary and sleep medicine providers are often asked to provide preoperative clearance and recommendations for patients with suspected or known OSA. Recognizing the need for guidance in this area, a task force assembled by SASM obtained input from experts in anesthesiology, sleep medicine, and perioperative medicine to develop and publish an evidence-based / expert consensus guideline on the preoperative assessment and best practices for patients with suspected or known OSA.6 While specifics regarding logistics of preoperative screening and optimization of patients will vary based on each medical center’s infrastructure and organization, the recommendations presented should be able to be adapted by most, if not all, institutions. Preoperative evaluation and management is only part of the overall perioperative journey however, and SASM thus followed this document with guidelines for the intraoperative management of patients with OSA.7 To complete this set of recommendations, guidelines for the postoperative care of these patients are being planned. Guidelines for pediatric and obstetric perioperative OSA management are also currently being developed by SASM task forces to address these unique areas.

OSA is not the only sleep disorder where the perioperative environment may pose problems for our patients. Sleep disorders such as the hypersomnias and sleep-related movement disorders (including restless legs syndrome) may both impact and be impacted by the perioperative environment and may create safety concerns for some patients.8,9 These issues are also under active investigation by SASM. In addition, understanding the basic mechanisms determining unconsciousness in both anesthesia and sleep, as well as examination of the interrelationships between sleep disturbance, sedation and their effects on clinical outcomes, are areas of interest that have implications beyond the perioperative arena.

SASM is currently planning to host its 10th anniversary conference in Washington DC on October 1-2, public health issues permitting. The meeting has consistently enlisted expert speakers from anesthesia, sleep medicine, and other relevant fields, and this year will be no different. Given the host city, discussions on important healthcare policy issues will be included, as well. Registration for the meeting, as well as meeting updates, are on the SASM website (sasmhq.org).

Dr. Auckley is with the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center, Professor of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH. He is the current president of the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine.

References

1. Gupta RM, et al. Postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome undergoing hip or knee replacement: A case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(9):897.

2. Opperer M, et al. Does obstructive sleep apnea influence perioperative outcome? A qualitative systematic review for the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Task Force on Preoperative Preparation of Patients with Sleep-Disordered Breathing. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(5):1321.

3. Chan MTV, et al. Association of unrecognized obstructive sleep apnea with postoperative cardiovascular events in patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1788.

4. Finkel KJ, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea among adult surgical patients in an academic center. Sleep Med. 2009;10(7):753.

5. Auckley D, et al. Attitudes regarding perioperative care of patients with OSA: a survey study of four specialties in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(1):315.

6. Chung F, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Guidelines (SASM) on Preoperative Screening and Assessment of Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(2):452.

7. Memtsoudis SG, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Guideline (SASM) on Intraoperative Management of Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(4):967.

8. Hershner S, et al. Knowledge gaps in the perioperative management of adults with narcolepsy: A call for further research. Anesth Analg. 2019 Jul;129(1):204.

9. Goldstein C. Management of restless legs syndrome / Willis-Ekbom disease in hospitalized and perioperative patients. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(3):303.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been recognized to increase the risk of adverse cardiopulmonary perioperative outcomes for some time now.1 An ever growing body of literature supports this finding,2 including a large prospective study published in 2019 highlighting the significant risk of poor cardiac-related postoperative outcomes in patients with unrecognized OSA.3 As the majority of patients presenting for elective surgery with OSA will not be diagnosed at the time of presentation,3,4 many centers have developed preoperative screening programs to identify these patients, though the practice is not universal and a desire for better guidance is needed.5 In addition, best practices for patients with suspected or known OSA undergoing surgery have been a matter of debate. Out of these concerns, the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine (SASM) was formed over 10 years ago to promote interdisciplinary communication, education, and research into matters common to anesthesia and sleep.

Pulmonary and sleep medicine providers are often asked to provide preoperative clearance and recommendations for patients with suspected or known OSA. Recognizing the need for guidance in this area, a task force assembled by SASM obtained input from experts in anesthesiology, sleep medicine, and perioperative medicine to develop and publish an evidence-based / expert consensus guideline on the preoperative assessment and best practices for patients with suspected or known OSA.6 While specifics regarding logistics of preoperative screening and optimization of patients will vary based on each medical center’s infrastructure and organization, the recommendations presented should be able to be adapted by most, if not all, institutions. Preoperative evaluation and management is only part of the overall perioperative journey however, and SASM thus followed this document with guidelines for the intraoperative management of patients with OSA.7 To complete this set of recommendations, guidelines for the postoperative care of these patients are being planned. Guidelines for pediatric and obstetric perioperative OSA management are also currently being developed by SASM task forces to address these unique areas.

OSA is not the only sleep disorder where the perioperative environment may pose problems for our patients. Sleep disorders such as the hypersomnias and sleep-related movement disorders (including restless legs syndrome) may both impact and be impacted by the perioperative environment and may create safety concerns for some patients.8,9 These issues are also under active investigation by SASM. In addition, understanding the basic mechanisms determining unconsciousness in both anesthesia and sleep, as well as examination of the interrelationships between sleep disturbance, sedation and their effects on clinical outcomes, are areas of interest that have implications beyond the perioperative arena.

SASM is currently planning to host its 10th anniversary conference in Washington DC on October 1-2, public health issues permitting. The meeting has consistently enlisted expert speakers from anesthesia, sleep medicine, and other relevant fields, and this year will be no different. Given the host city, discussions on important healthcare policy issues will be included, as well. Registration for the meeting, as well as meeting updates, are on the SASM website (sasmhq.org).

Dr. Auckley is with the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center, Professor of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH. He is the current president of the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine.

References

1. Gupta RM, et al. Postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome undergoing hip or knee replacement: A case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(9):897.

2. Opperer M, et al. Does obstructive sleep apnea influence perioperative outcome? A qualitative systematic review for the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Task Force on Preoperative Preparation of Patients with Sleep-Disordered Breathing. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(5):1321.

3. Chan MTV, et al. Association of unrecognized obstructive sleep apnea with postoperative cardiovascular events in patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1788.

4. Finkel KJ, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea among adult surgical patients in an academic center. Sleep Med. 2009;10(7):753.

5. Auckley D, et al. Attitudes regarding perioperative care of patients with OSA: a survey study of four specialties in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(1):315.

6. Chung F, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Guidelines (SASM) on Preoperative Screening and Assessment of Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(2):452.

7. Memtsoudis SG, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Guideline (SASM) on Intraoperative Management of Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(4):967.

8. Hershner S, et al. Knowledge gaps in the perioperative management of adults with narcolepsy: A call for further research. Anesth Analg. 2019 Jul;129(1):204.

9. Goldstein C. Management of restless legs syndrome / Willis-Ekbom disease in hospitalized and perioperative patients. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(3):303.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been recognized to increase the risk of adverse cardiopulmonary perioperative outcomes for some time now.1 An ever growing body of literature supports this finding,2 including a large prospective study published in 2019 highlighting the significant risk of poor cardiac-related postoperative outcomes in patients with unrecognized OSA.3 As the majority of patients presenting for elective surgery with OSA will not be diagnosed at the time of presentation,3,4 many centers have developed preoperative screening programs to identify these patients, though the practice is not universal and a desire for better guidance is needed.5 In addition, best practices for patients with suspected or known OSA undergoing surgery have been a matter of debate. Out of these concerns, the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine (SASM) was formed over 10 years ago to promote interdisciplinary communication, education, and research into matters common to anesthesia and sleep.

Pulmonary and sleep medicine providers are often asked to provide preoperative clearance and recommendations for patients with suspected or known OSA. Recognizing the need for guidance in this area, a task force assembled by SASM obtained input from experts in anesthesiology, sleep medicine, and perioperative medicine to develop and publish an evidence-based / expert consensus guideline on the preoperative assessment and best practices for patients with suspected or known OSA.6 While specifics regarding logistics of preoperative screening and optimization of patients will vary based on each medical center’s infrastructure and organization, the recommendations presented should be able to be adapted by most, if not all, institutions. Preoperative evaluation and management is only part of the overall perioperative journey however, and SASM thus followed this document with guidelines for the intraoperative management of patients with OSA.7 To complete this set of recommendations, guidelines for the postoperative care of these patients are being planned. Guidelines for pediatric and obstetric perioperative OSA management are also currently being developed by SASM task forces to address these unique areas.

OSA is not the only sleep disorder where the perioperative environment may pose problems for our patients. Sleep disorders such as the hypersomnias and sleep-related movement disorders (including restless legs syndrome) may both impact and be impacted by the perioperative environment and may create safety concerns for some patients.8,9 These issues are also under active investigation by SASM. In addition, understanding the basic mechanisms determining unconsciousness in both anesthesia and sleep, as well as examination of the interrelationships between sleep disturbance, sedation and their effects on clinical outcomes, are areas of interest that have implications beyond the perioperative arena.

SASM is currently planning to host its 10th anniversary conference in Washington DC on October 1-2, public health issues permitting. The meeting has consistently enlisted expert speakers from anesthesia, sleep medicine, and other relevant fields, and this year will be no different. Given the host city, discussions on important healthcare policy issues will be included, as well. Registration for the meeting, as well as meeting updates, are on the SASM website (sasmhq.org).

Dr. Auckley is with the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center, Professor of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH. He is the current president of the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine.

References

1. Gupta RM, et al. Postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome undergoing hip or knee replacement: A case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(9):897.

2. Opperer M, et al. Does obstructive sleep apnea influence perioperative outcome? A qualitative systematic review for the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Task Force on Preoperative Preparation of Patients with Sleep-Disordered Breathing. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(5):1321.

3. Chan MTV, et al. Association of unrecognized obstructive sleep apnea with postoperative cardiovascular events in patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1788.

4. Finkel KJ, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea among adult surgical patients in an academic center. Sleep Med. 2009;10(7):753.

5. Auckley D, et al. Attitudes regarding perioperative care of patients with OSA: a survey study of four specialties in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(1):315.

6. Chung F, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Guidelines (SASM) on Preoperative Screening and Assessment of Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(2):452.

7. Memtsoudis SG, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Guideline (SASM) on Intraoperative Management of Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(4):967.

8. Hershner S, et al. Knowledge gaps in the perioperative management of adults with narcolepsy: A call for further research. Anesth Analg. 2019 Jul;129(1):204.

9. Goldstein C. Management of restless legs syndrome / Willis-Ekbom disease in hospitalized and perioperative patients. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(3):303.

COVID-19 and the future of telehealth for sleep medicine

On March 18, 2020, the doors to our sleep center were physically closed. Two potential exposures to COVID-19 within a few hours, the palpable anxiety of our team, and a poor grasp of the virus and the growing pandemic moved us to make this decision. Up to that point, we could not help but feel we were playing “catch up” with our evolving set of safety measures to the escalating risk. Like so many other sleep centers around the country, a complete transition to virtual care was needed to ensure the safety of our patients and our team. It was perhaps that moment that we felt the emotional impact that our world had changed, altering both our personal lives and sleep medicine practice as we knew it. This event, while unfortunate, also provided a transformative opportunity to reimagine our identity, accelerating the efforts to bring the future of sleep medicine into the present.

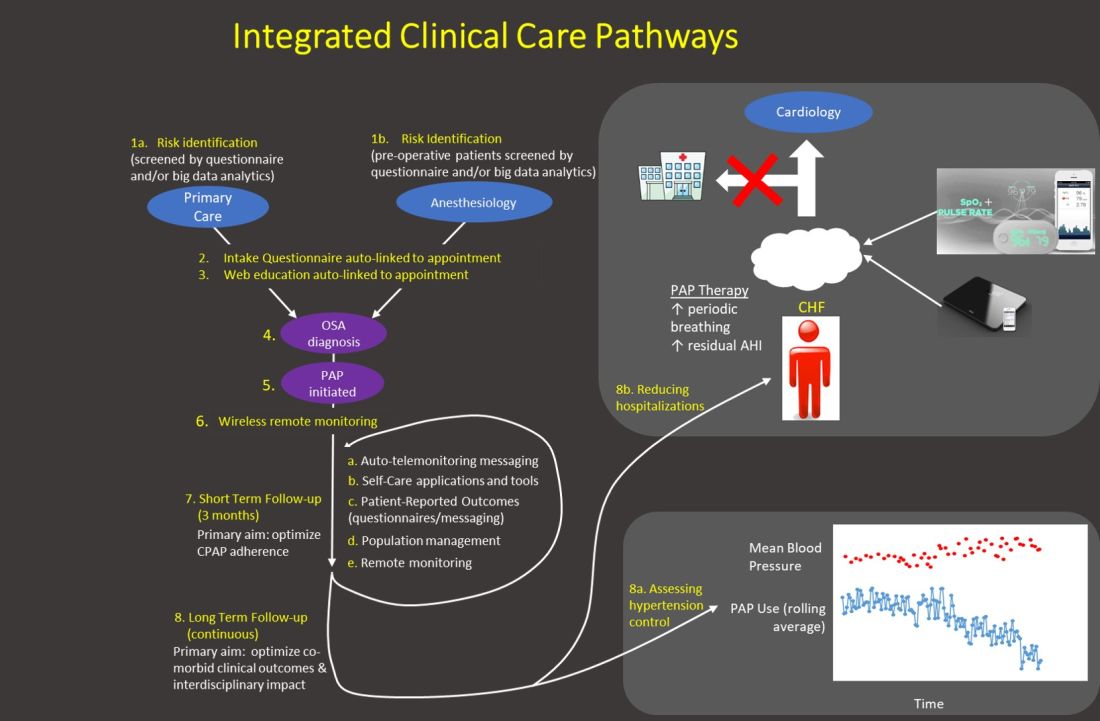

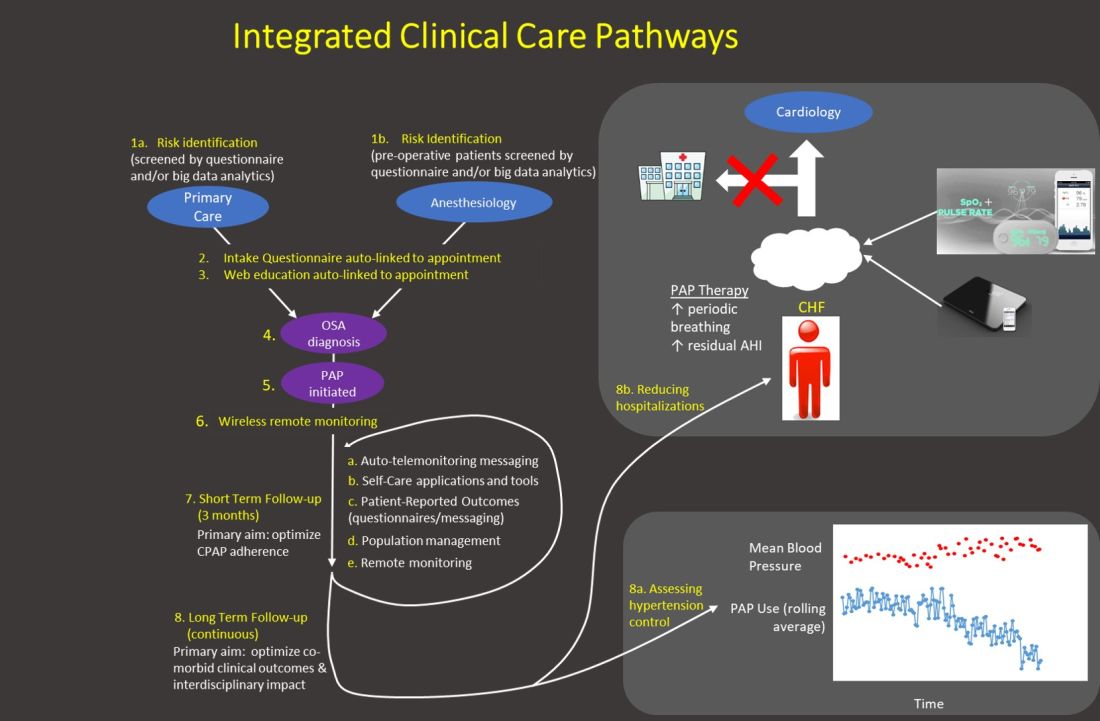

Our team’s clinical evolution and innovation efforts have been guided by efforts to reconsider sleep medicine paradigms. Innovation progress was deliberate with incremental implementations that typically required repeat business cases with multiple approving parties and budgetary access. Those barriers largely dissolved once COVID-19 intensified, and a large portion of the strategies on our roadmap were put into production. In a matter of a couple weeks, our services completely transitioned to remote and virtual care, while most of the team of 55 persons were moved to “work-from-home.” A suite of technologies (automated questionnaires, automated and two-way text messaging templates, consumer wearable technologies, and population management dashboards) were put on the table (Somnoware, Inc.), and each of our longitudinal care teams (eg, adult obstructive sleep apnea, pediatrics, chronic respiratory failure, commercial driver, insomnia programs, etc) worked to embed them into new care pathways. This effort further consolidated technology as the backbone of our work and the enabler of remote virtual collaboration between sleep center personnel (respiratory case managers, medical assistants and nursing team, and physician and leadership personnel) to enhance our team-based approach. Moreover, we felt this point in time was ripe to swallow the proverbial “red pill” and approach patient care with shifted paradigms. We discuss three areas of active effort to leverage technology in this COVID-19 environment to accelerate a transition toward how we envision the future of sleep medicine.

Reimagined sleep diagnostics

Our virtual obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) diagnostic process includes utilizing a disposable home sleep apnea test (HSAT) device with wireless data transfer (WatchPAT ONE, Itamar Medical) while HSAT and PAP (positive airway pressure) setups are supported by information sheets, online videos (YouTube), automated interactive platforms (Emmi Solutions; Hwang D. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Jan 1;197[1]:117), and synchronous provider video visits. Our more radical shift, however, is in approaching OSA diagnosis based principally on symptoms and secondarily supported by physiologic measurements and response to therapy. This “clinical diagnosis” approach reduces our reliance on traditional sleep testing and allows patient wearables to provide supportive physiologic data (eg, oximetry) to help determine OSA severity and phenotype. Its immediate impact is in limiting the need to send and retrieve potentially contaminated equipment. Broader clinical advantages include overcoming the imprecise nature of the apnea-hypopnea index (which often has dramatic night-to-night variability) through data collection over extended durations, improving disease assessment due to availability of complementary sleep/activity data in the person’s usual setting, and tracking changes after therapy initiation.

Our post-COVID-19 re-opening of polysomnography (PSG) services, after a temporary shutdown, introduces home PSG (Type II) for approximately half our patients without suspected complex breathing conditions while reserving attended PSG (Type I) for those who may require noninvasive ventilation. The immediate incentive is in reducing viral exposure by limiting patient traffic and risk of PAP trial aerosolization while also improving access to accommodate the backlog of patients requiring PSG. This approach furthers the paradigm shift to emphasizing care in the home setting. Testing in the patient’s usual environment and enabling multiple night/day testing may be clinically advantageous.

Shift in emphasis to care management

The emphasis of sleep medicine has traditionally focused on diagnostics through performing PSG and HSAT. Our field has invested tremendous effort in developing guidelines for processing sleep studies, but the scoring and interpretation of those studies is extremely labor intensive. Reimagining the diagnostic approach reduces the need to manually process studies—wearable data are produced automatically, HSAT can be auto-scored, and artificial intelligence platforms can score PSGs (Goldstein CA. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Apr 15;16[4]:609), which allows a shift in resources and emphasis to follow-up care. A comprehensive discussion of technology-based tools to enhance care management is beyond the purview of this editorial. However, an overview of our current efforts includes: (1) utilizing population management dashboards to automatically risk stratify different cohorts of patients (eg, adult OSA, pediatrics, commercial drivers, chronic respiratory failure, etc) to identify patients “at-risk” (eg, based on OSA severity, symptoms, co-morbidities, and PAP adherence); (2) applying enhanced patient-provider interchange tools that include automated and “intelligent” electronic questionnaires, automated personalized text messaging/emails, and two-way messaging to deliver care; (3) utilizing remote patient monitoring to enhance holistic, personalized management, such as with remote activity/sleep trackers, blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and weight scales. We are engaged with efforts to validate the impact of these data to provide more personalized feedback, directly impact clinical outcomes, facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration, and identify acutely ill patients. Furthermore, a holistic approach beyond a narrow focus on PAP may create a positive collateral effect on adherence by targeting engagement with broader areas of health; and (4) implementing machine learning tools to directly support providers and patients (examples discussed in the next section.) Each of our teams has created workflows embedding these strategies throughout new care pathways.

Generally, our emphasis during the first 3 months after PAP initiation focuses on achieving therapy adherence, and the post-3-month period broadens the efforts to target clinical outcomes. Recent trials with low PAP usage that failed to confirm the benefit of PAP on cardiovascular outcomes (McEvoy DR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:919) strongly suggest greater investment in cost-effective long-term strategies is imperative to increase our field’s relevance.

Application of artificial intelligence

We describe current efforts to apply artificial intelligence (AI) into clinical care: (1) We are implementing machine learning (ML) PSG scoring, which can potentially improve both the consistency and efficiency of scoring, further enabling greater investment in follow-up care. The future of sleep study processing, however, will likely depend on computer vision to “view” details inaccessible to the human eye and produce novel metrics that better inform clinical phenotypes (eg, cardiovascular risk, response to alternative therapies, etc). For example, “brain age” has been derived from EEG tracings that could reflect the degree of impact of sleep disorders on neurocognitive function (Fernandez C, unpublished data); (2) Machine learning clinical decision tools are in development to predict PAP adherence and timing of discontinuation, predict timing of cardiovascular disease onset and hospitalization, personalizing adherence targets, automating triaging of patients to home or PSG testing, and innumerable other predictions at clinical decision inflection points. Prediction outputs may be presented as risk profiles embedded in each patient’s “chart,” as personalized alerts, and in gamification strategies. For example, machine learning personalized cardiovascular risk scores can be regularly updated based on degree of PAP use to incentivize adherence; (3) Artificial providers may provide consistent, personalized, and holistic supplementary care. Many people rely on AI-bots for social support and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression. A sleep wellness bot, currently in planning stages, is intended to be the primary interface for many of the strategies described above that enhance engagement with PAP and therapies for comorbid conditions, provide CBT and lifestyle accountability, and collect patient reported data. This artificial provider would be a constant companion providing interactive, personalized, and continuous management to complement traditional intermittent live-person care.

The current health-care environment embodies the principle to “never let a serious crisis go to waste.” COVID-19 has accelerated the progression into the future by fostering an opening to embrace novel application of technologies to support changes in paradigms. Furthermore, health-care infrastructures that typically progress deliberately changed seemingly in a single moment. The Center for Medicare Services issued broad authorization to reimburse for telemedicine in response to COVID-19. Continued evolution in infrastructures will dictate progress with innovation, and a greater transition to outcomes-based incentives may be necessary to accommodate many of the strategies described above that rely on nonsynchronous care. But, we may be experiencing the moment when health care starts to catch up with the world in its embrace of technology. Sleep and pulmonary medicine can be a leader by providing a successful template for other specialties in optimizing chronic disease management.

Dr. Hwang is Medical Director, Kaiser Permanente SBC Sleep Center, and co-chair, Sleep Medicine, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

On March 18, 2020, the doors to our sleep center were physically closed. Two potential exposures to COVID-19 within a few hours, the palpable anxiety of our team, and a poor grasp of the virus and the growing pandemic moved us to make this decision. Up to that point, we could not help but feel we were playing “catch up” with our evolving set of safety measures to the escalating risk. Like so many other sleep centers around the country, a complete transition to virtual care was needed to ensure the safety of our patients and our team. It was perhaps that moment that we felt the emotional impact that our world had changed, altering both our personal lives and sleep medicine practice as we knew it. This event, while unfortunate, also provided a transformative opportunity to reimagine our identity, accelerating the efforts to bring the future of sleep medicine into the present.

Our team’s clinical evolution and innovation efforts have been guided by efforts to reconsider sleep medicine paradigms. Innovation progress was deliberate with incremental implementations that typically required repeat business cases with multiple approving parties and budgetary access. Those barriers largely dissolved once COVID-19 intensified, and a large portion of the strategies on our roadmap were put into production. In a matter of a couple weeks, our services completely transitioned to remote and virtual care, while most of the team of 55 persons were moved to “work-from-home.” A suite of technologies (automated questionnaires, automated and two-way text messaging templates, consumer wearable technologies, and population management dashboards) were put on the table (Somnoware, Inc.), and each of our longitudinal care teams (eg, adult obstructive sleep apnea, pediatrics, chronic respiratory failure, commercial driver, insomnia programs, etc) worked to embed them into new care pathways. This effort further consolidated technology as the backbone of our work and the enabler of remote virtual collaboration between sleep center personnel (respiratory case managers, medical assistants and nursing team, and physician and leadership personnel) to enhance our team-based approach. Moreover, we felt this point in time was ripe to swallow the proverbial “red pill” and approach patient care with shifted paradigms. We discuss three areas of active effort to leverage technology in this COVID-19 environment to accelerate a transition toward how we envision the future of sleep medicine.

Reimagined sleep diagnostics

Our virtual obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) diagnostic process includes utilizing a disposable home sleep apnea test (HSAT) device with wireless data transfer (WatchPAT ONE, Itamar Medical) while HSAT and PAP (positive airway pressure) setups are supported by information sheets, online videos (YouTube), automated interactive platforms (Emmi Solutions; Hwang D. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Jan 1;197[1]:117), and synchronous provider video visits. Our more radical shift, however, is in approaching OSA diagnosis based principally on symptoms and secondarily supported by physiologic measurements and response to therapy. This “clinical diagnosis” approach reduces our reliance on traditional sleep testing and allows patient wearables to provide supportive physiologic data (eg, oximetry) to help determine OSA severity and phenotype. Its immediate impact is in limiting the need to send and retrieve potentially contaminated equipment. Broader clinical advantages include overcoming the imprecise nature of the apnea-hypopnea index (which often has dramatic night-to-night variability) through data collection over extended durations, improving disease assessment due to availability of complementary sleep/activity data in the person’s usual setting, and tracking changes after therapy initiation.

Our post-COVID-19 re-opening of polysomnography (PSG) services, after a temporary shutdown, introduces home PSG (Type II) for approximately half our patients without suspected complex breathing conditions while reserving attended PSG (Type I) for those who may require noninvasive ventilation. The immediate incentive is in reducing viral exposure by limiting patient traffic and risk of PAP trial aerosolization while also improving access to accommodate the backlog of patients requiring PSG. This approach furthers the paradigm shift to emphasizing care in the home setting. Testing in the patient’s usual environment and enabling multiple night/day testing may be clinically advantageous.

Shift in emphasis to care management

The emphasis of sleep medicine has traditionally focused on diagnostics through performing PSG and HSAT. Our field has invested tremendous effort in developing guidelines for processing sleep studies, but the scoring and interpretation of those studies is extremely labor intensive. Reimagining the diagnostic approach reduces the need to manually process studies—wearable data are produced automatically, HSAT can be auto-scored, and artificial intelligence platforms can score PSGs (Goldstein CA. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Apr 15;16[4]:609), which allows a shift in resources and emphasis to follow-up care. A comprehensive discussion of technology-based tools to enhance care management is beyond the purview of this editorial. However, an overview of our current efforts includes: (1) utilizing population management dashboards to automatically risk stratify different cohorts of patients (eg, adult OSA, pediatrics, commercial drivers, chronic respiratory failure, etc) to identify patients “at-risk” (eg, based on OSA severity, symptoms, co-morbidities, and PAP adherence); (2) applying enhanced patient-provider interchange tools that include automated and “intelligent” electronic questionnaires, automated personalized text messaging/emails, and two-way messaging to deliver care; (3) utilizing remote patient monitoring to enhance holistic, personalized management, such as with remote activity/sleep trackers, blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and weight scales. We are engaged with efforts to validate the impact of these data to provide more personalized feedback, directly impact clinical outcomes, facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration, and identify acutely ill patients. Furthermore, a holistic approach beyond a narrow focus on PAP may create a positive collateral effect on adherence by targeting engagement with broader areas of health; and (4) implementing machine learning tools to directly support providers and patients (examples discussed in the next section.) Each of our teams has created workflows embedding these strategies throughout new care pathways.

Generally, our emphasis during the first 3 months after PAP initiation focuses on achieving therapy adherence, and the post-3-month period broadens the efforts to target clinical outcomes. Recent trials with low PAP usage that failed to confirm the benefit of PAP on cardiovascular outcomes (McEvoy DR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:919) strongly suggest greater investment in cost-effective long-term strategies is imperative to increase our field’s relevance.

Application of artificial intelligence

We describe current efforts to apply artificial intelligence (AI) into clinical care: (1) We are implementing machine learning (ML) PSG scoring, which can potentially improve both the consistency and efficiency of scoring, further enabling greater investment in follow-up care. The future of sleep study processing, however, will likely depend on computer vision to “view” details inaccessible to the human eye and produce novel metrics that better inform clinical phenotypes (eg, cardiovascular risk, response to alternative therapies, etc). For example, “brain age” has been derived from EEG tracings that could reflect the degree of impact of sleep disorders on neurocognitive function (Fernandez C, unpublished data); (2) Machine learning clinical decision tools are in development to predict PAP adherence and timing of discontinuation, predict timing of cardiovascular disease onset and hospitalization, personalizing adherence targets, automating triaging of patients to home or PSG testing, and innumerable other predictions at clinical decision inflection points. Prediction outputs may be presented as risk profiles embedded in each patient’s “chart,” as personalized alerts, and in gamification strategies. For example, machine learning personalized cardiovascular risk scores can be regularly updated based on degree of PAP use to incentivize adherence; (3) Artificial providers may provide consistent, personalized, and holistic supplementary care. Many people rely on AI-bots for social support and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression. A sleep wellness bot, currently in planning stages, is intended to be the primary interface for many of the strategies described above that enhance engagement with PAP and therapies for comorbid conditions, provide CBT and lifestyle accountability, and collect patient reported data. This artificial provider would be a constant companion providing interactive, personalized, and continuous management to complement traditional intermittent live-person care.

The current health-care environment embodies the principle to “never let a serious crisis go to waste.” COVID-19 has accelerated the progression into the future by fostering an opening to embrace novel application of technologies to support changes in paradigms. Furthermore, health-care infrastructures that typically progress deliberately changed seemingly in a single moment. The Center for Medicare Services issued broad authorization to reimburse for telemedicine in response to COVID-19. Continued evolution in infrastructures will dictate progress with innovation, and a greater transition to outcomes-based incentives may be necessary to accommodate many of the strategies described above that rely on nonsynchronous care. But, we may be experiencing the moment when health care starts to catch up with the world in its embrace of technology. Sleep and pulmonary medicine can be a leader by providing a successful template for other specialties in optimizing chronic disease management.

Dr. Hwang is Medical Director, Kaiser Permanente SBC Sleep Center, and co-chair, Sleep Medicine, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

On March 18, 2020, the doors to our sleep center were physically closed. Two potential exposures to COVID-19 within a few hours, the palpable anxiety of our team, and a poor grasp of the virus and the growing pandemic moved us to make this decision. Up to that point, we could not help but feel we were playing “catch up” with our evolving set of safety measures to the escalating risk. Like so many other sleep centers around the country, a complete transition to virtual care was needed to ensure the safety of our patients and our team. It was perhaps that moment that we felt the emotional impact that our world had changed, altering both our personal lives and sleep medicine practice as we knew it. This event, while unfortunate, also provided a transformative opportunity to reimagine our identity, accelerating the efforts to bring the future of sleep medicine into the present.

Our team’s clinical evolution and innovation efforts have been guided by efforts to reconsider sleep medicine paradigms. Innovation progress was deliberate with incremental implementations that typically required repeat business cases with multiple approving parties and budgetary access. Those barriers largely dissolved once COVID-19 intensified, and a large portion of the strategies on our roadmap were put into production. In a matter of a couple weeks, our services completely transitioned to remote and virtual care, while most of the team of 55 persons were moved to “work-from-home.” A suite of technologies (automated questionnaires, automated and two-way text messaging templates, consumer wearable technologies, and population management dashboards) were put on the table (Somnoware, Inc.), and each of our longitudinal care teams (eg, adult obstructive sleep apnea, pediatrics, chronic respiratory failure, commercial driver, insomnia programs, etc) worked to embed them into new care pathways. This effort further consolidated technology as the backbone of our work and the enabler of remote virtual collaboration between sleep center personnel (respiratory case managers, medical assistants and nursing team, and physician and leadership personnel) to enhance our team-based approach. Moreover, we felt this point in time was ripe to swallow the proverbial “red pill” and approach patient care with shifted paradigms. We discuss three areas of active effort to leverage technology in this COVID-19 environment to accelerate a transition toward how we envision the future of sleep medicine.

Reimagined sleep diagnostics

Our virtual obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) diagnostic process includes utilizing a disposable home sleep apnea test (HSAT) device with wireless data transfer (WatchPAT ONE, Itamar Medical) while HSAT and PAP (positive airway pressure) setups are supported by information sheets, online videos (YouTube), automated interactive platforms (Emmi Solutions; Hwang D. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Jan 1;197[1]:117), and synchronous provider video visits. Our more radical shift, however, is in approaching OSA diagnosis based principally on symptoms and secondarily supported by physiologic measurements and response to therapy. This “clinical diagnosis” approach reduces our reliance on traditional sleep testing and allows patient wearables to provide supportive physiologic data (eg, oximetry) to help determine OSA severity and phenotype. Its immediate impact is in limiting the need to send and retrieve potentially contaminated equipment. Broader clinical advantages include overcoming the imprecise nature of the apnea-hypopnea index (which often has dramatic night-to-night variability) through data collection over extended durations, improving disease assessment due to availability of complementary sleep/activity data in the person’s usual setting, and tracking changes after therapy initiation.

Our post-COVID-19 re-opening of polysomnography (PSG) services, after a temporary shutdown, introduces home PSG (Type II) for approximately half our patients without suspected complex breathing conditions while reserving attended PSG (Type I) for those who may require noninvasive ventilation. The immediate incentive is in reducing viral exposure by limiting patient traffic and risk of PAP trial aerosolization while also improving access to accommodate the backlog of patients requiring PSG. This approach furthers the paradigm shift to emphasizing care in the home setting. Testing in the patient’s usual environment and enabling multiple night/day testing may be clinically advantageous.

Shift in emphasis to care management

The emphasis of sleep medicine has traditionally focused on diagnostics through performing PSG and HSAT. Our field has invested tremendous effort in developing guidelines for processing sleep studies, but the scoring and interpretation of those studies is extremely labor intensive. Reimagining the diagnostic approach reduces the need to manually process studies—wearable data are produced automatically, HSAT can be auto-scored, and artificial intelligence platforms can score PSGs (Goldstein CA. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Apr 15;16[4]:609), which allows a shift in resources and emphasis to follow-up care. A comprehensive discussion of technology-based tools to enhance care management is beyond the purview of this editorial. However, an overview of our current efforts includes: (1) utilizing population management dashboards to automatically risk stratify different cohorts of patients (eg, adult OSA, pediatrics, commercial drivers, chronic respiratory failure, etc) to identify patients “at-risk” (eg, based on OSA severity, symptoms, co-morbidities, and PAP adherence); (2) applying enhanced patient-provider interchange tools that include automated and “intelligent” electronic questionnaires, automated personalized text messaging/emails, and two-way messaging to deliver care; (3) utilizing remote patient monitoring to enhance holistic, personalized management, such as with remote activity/sleep trackers, blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and weight scales. We are engaged with efforts to validate the impact of these data to provide more personalized feedback, directly impact clinical outcomes, facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration, and identify acutely ill patients. Furthermore, a holistic approach beyond a narrow focus on PAP may create a positive collateral effect on adherence by targeting engagement with broader areas of health; and (4) implementing machine learning tools to directly support providers and patients (examples discussed in the next section.) Each of our teams has created workflows embedding these strategies throughout new care pathways.

Generally, our emphasis during the first 3 months after PAP initiation focuses on achieving therapy adherence, and the post-3-month period broadens the efforts to target clinical outcomes. Recent trials with low PAP usage that failed to confirm the benefit of PAP on cardiovascular outcomes (McEvoy DR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:919) strongly suggest greater investment in cost-effective long-term strategies is imperative to increase our field’s relevance.

Application of artificial intelligence

We describe current efforts to apply artificial intelligence (AI) into clinical care: (1) We are implementing machine learning (ML) PSG scoring, which can potentially improve both the consistency and efficiency of scoring, further enabling greater investment in follow-up care. The future of sleep study processing, however, will likely depend on computer vision to “view” details inaccessible to the human eye and produce novel metrics that better inform clinical phenotypes (eg, cardiovascular risk, response to alternative therapies, etc). For example, “brain age” has been derived from EEG tracings that could reflect the degree of impact of sleep disorders on neurocognitive function (Fernandez C, unpublished data); (2) Machine learning clinical decision tools are in development to predict PAP adherence and timing of discontinuation, predict timing of cardiovascular disease onset and hospitalization, personalizing adherence targets, automating triaging of patients to home or PSG testing, and innumerable other predictions at clinical decision inflection points. Prediction outputs may be presented as risk profiles embedded in each patient’s “chart,” as personalized alerts, and in gamification strategies. For example, machine learning personalized cardiovascular risk scores can be regularly updated based on degree of PAP use to incentivize adherence; (3) Artificial providers may provide consistent, personalized, and holistic supplementary care. Many people rely on AI-bots for social support and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression. A sleep wellness bot, currently in planning stages, is intended to be the primary interface for many of the strategies described above that enhance engagement with PAP and therapies for comorbid conditions, provide CBT and lifestyle accountability, and collect patient reported data. This artificial provider would be a constant companion providing interactive, personalized, and continuous management to complement traditional intermittent live-person care.

The current health-care environment embodies the principle to “never let a serious crisis go to waste.” COVID-19 has accelerated the progression into the future by fostering an opening to embrace novel application of technologies to support changes in paradigms. Furthermore, health-care infrastructures that typically progress deliberately changed seemingly in a single moment. The Center for Medicare Services issued broad authorization to reimburse for telemedicine in response to COVID-19. Continued evolution in infrastructures will dictate progress with innovation, and a greater transition to outcomes-based incentives may be necessary to accommodate many of the strategies described above that rely on nonsynchronous care. But, we may be experiencing the moment when health care starts to catch up with the world in its embrace of technology. Sleep and pulmonary medicine can be a leader by providing a successful template for other specialties in optimizing chronic disease management.

Dr. Hwang is Medical Director, Kaiser Permanente SBC Sleep Center, and co-chair, Sleep Medicine, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

This month in the journal CHEST®: Editor’s picks

Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China.By Dr. L. Shiyue, et al.

Effect of intermittent or continuous feed on muscle wasting in critical illness a phase II clinical trial. By Dr. A. McNelly, et al.

Triage of scarce critical care resources in COVID-19: An implementation guide for regional allocation: A CHEST and Task Force for Mass Critical Care Expert Panel Report.By Dr. J. Dichter, et al.

Managing Chronic Cough as a Symptom in Children and Management Algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. Chang, et al.

Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China.By Dr. L. Shiyue, et al.

Effect of intermittent or continuous feed on muscle wasting in critical illness a phase II clinical trial. By Dr. A. McNelly, et al.

Triage of scarce critical care resources in COVID-19: An implementation guide for regional allocation: A CHEST and Task Force for Mass Critical Care Expert Panel Report.By Dr. J. Dichter, et al.

Managing Chronic Cough as a Symptom in Children and Management Algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. Chang, et al.