User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Sweeping new vaccine mandates will impact most U.S. workers

, including sweeping vaccine mandates that will affect 100 million American workers, nearly two-thirds of the country’s workforce.

“As your president, I’m announcing tonight a new plan to get more Americans vaccinated to combat those blocking public health,” he said Sept. 9.

As part of a six-part plan unveiled in a speech from the State Dining Room of the White House, President Biden said he would require vaccinations for nearly 4 million federal workers and the employees of companies that contract with the federal government.

He has also directed the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to develop a rule that will require large employers -- those with at least 100 employees -- to ensure their workers are vaccinated or tested weekly.

Nearly 17 million health care workers will face new vaccine mandates as part of the conditions of participation in the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

President Biden said the federal government will require staff at federally funded Head Start programs and schools to be vaccinated. He’s also calling on all states to mandate vaccines for teachers.

“A distinct minority of Americans, supported by a distinct minority of elected officials, are keeping us from turning the corner,” PresidentBiden said. “These pandemic politics, as I refer to them, are making people sick, causing unvaccinated people to die.”

One public health official said he was glad to see the president’s bold action.

“What I saw today was the federal government trying to use its powers to create greater safety in the American population,” said Ashish K. Jha, MD, dean of the school of public health at Brown University, Providence, R.I., in a call with reporters after the speech.

National Nurses United, the largest union of registered nurses in the United States, issued a statement in support of President Biden’s new vaccination requirements, but pushed back on his language.

“…as advocates for public health, registered nurses want to be extremely clear: There is no such thing as a pandemic of only the unvaccinated. The science of epidemiology tells us there is just one deadly, global pandemic that has not yet ended, and we are all in it together. To get out of it, we must act together. All of us,” the statement says.

A host of other professional groups, including the American Medical Association and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, also issued statements of support for President Biden’s plan.

But the plan was not well received by all.

“I will pursue every legal option available to the state of Georgia to stop this blatantly unlawful overreach by the Biden Administration,” said Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, a Republican, in a Tweet.

The National Council for Occupational Safety and Health called the plan “a missed opportunity” because it failed to include workplace protections for essential workers such as grocery, postal, and transit workers.

“Social distancing, improved ventilation, shift rotation, and protective equipment to reduce exposure are important components of an overall plan to reduce risk and stop the virus. These tools are missing from the new steps President Biden announced today,” said Jessica Martinez, co-executive director of the group.

In addition to the new vaccination requirements, President Biden said extra doses would be on the way for people who have already been fully vaccinated in order to protect against waning immunity, starting on Sept. 20. But he noted that those plans would be contingent on the Food and Drug Administration’s approval for third doses and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation of the shots.

President Biden pledged to use the Defense Production Act to ramp up production of at-home tests, which have been selling out across the nation as the Delta variant spreads.

He also announced plans to expand access to COVID-19 testing, including offering testing for free at thousands of pharmacies nationwide and getting major retailers to sell at-home COVID-19 tests at cost.

The BinaxNow test kit, which currently retails for $23.99, will now cost about $15 for two tests at Kroger, Amazon, and Walmart, according to the White House. Food banks and community health centers will get free tests, too.

He called on states to set up COVID-19 testing programs at all schools.

Jha said that in his view, the big, game-changing news out of the president’s speech was the expansion of testing.

“Our country has failed to deploy tests in a way that can really bring this pandemic under control,” Jha said. “There are plenty of reasons, data, experience to indicate that if these were widely available, it would make a dramatic difference in reducing infection numbers across our country.”.

Dr. Jha said the private market had not worked effectively to make testing more widely available, so it was “absolutely a requirement of the federal government to step in and make testing more widely available,” he said.

President Biden also announced new economic stimulus programs, saying he’s expanding loan programs to small businesses and streamlining the loan forgiveness process.

President Biden said he’s boosting help for overburdened hospitals, doubling the number of federal surge response teams sent to hard-hit areas to reduce the strain on local health care workers. He said he would increase the pace of antibody treatments to states by 50%.

“We made so much progress during the past 7 months of this pandemic. Even so, we remain at a critical moment, a critical time,” he said. “We have the tools. Now, we just have to finish the job with truth, with science, with confidence and together as one nation.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, including sweeping vaccine mandates that will affect 100 million American workers, nearly two-thirds of the country’s workforce.

“As your president, I’m announcing tonight a new plan to get more Americans vaccinated to combat those blocking public health,” he said Sept. 9.

As part of a six-part plan unveiled in a speech from the State Dining Room of the White House, President Biden said he would require vaccinations for nearly 4 million federal workers and the employees of companies that contract with the federal government.

He has also directed the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to develop a rule that will require large employers -- those with at least 100 employees -- to ensure their workers are vaccinated or tested weekly.

Nearly 17 million health care workers will face new vaccine mandates as part of the conditions of participation in the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

President Biden said the federal government will require staff at federally funded Head Start programs and schools to be vaccinated. He’s also calling on all states to mandate vaccines for teachers.

“A distinct minority of Americans, supported by a distinct minority of elected officials, are keeping us from turning the corner,” PresidentBiden said. “These pandemic politics, as I refer to them, are making people sick, causing unvaccinated people to die.”

One public health official said he was glad to see the president’s bold action.

“What I saw today was the federal government trying to use its powers to create greater safety in the American population,” said Ashish K. Jha, MD, dean of the school of public health at Brown University, Providence, R.I., in a call with reporters after the speech.

National Nurses United, the largest union of registered nurses in the United States, issued a statement in support of President Biden’s new vaccination requirements, but pushed back on his language.

“…as advocates for public health, registered nurses want to be extremely clear: There is no such thing as a pandemic of only the unvaccinated. The science of epidemiology tells us there is just one deadly, global pandemic that has not yet ended, and we are all in it together. To get out of it, we must act together. All of us,” the statement says.

A host of other professional groups, including the American Medical Association and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, also issued statements of support for President Biden’s plan.

But the plan was not well received by all.

“I will pursue every legal option available to the state of Georgia to stop this blatantly unlawful overreach by the Biden Administration,” said Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, a Republican, in a Tweet.

The National Council for Occupational Safety and Health called the plan “a missed opportunity” because it failed to include workplace protections for essential workers such as grocery, postal, and transit workers.

“Social distancing, improved ventilation, shift rotation, and protective equipment to reduce exposure are important components of an overall plan to reduce risk and stop the virus. These tools are missing from the new steps President Biden announced today,” said Jessica Martinez, co-executive director of the group.

In addition to the new vaccination requirements, President Biden said extra doses would be on the way for people who have already been fully vaccinated in order to protect against waning immunity, starting on Sept. 20. But he noted that those plans would be contingent on the Food and Drug Administration’s approval for third doses and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation of the shots.

President Biden pledged to use the Defense Production Act to ramp up production of at-home tests, which have been selling out across the nation as the Delta variant spreads.

He also announced plans to expand access to COVID-19 testing, including offering testing for free at thousands of pharmacies nationwide and getting major retailers to sell at-home COVID-19 tests at cost.

The BinaxNow test kit, which currently retails for $23.99, will now cost about $15 for two tests at Kroger, Amazon, and Walmart, according to the White House. Food banks and community health centers will get free tests, too.

He called on states to set up COVID-19 testing programs at all schools.

Jha said that in his view, the big, game-changing news out of the president’s speech was the expansion of testing.

“Our country has failed to deploy tests in a way that can really bring this pandemic under control,” Jha said. “There are plenty of reasons, data, experience to indicate that if these were widely available, it would make a dramatic difference in reducing infection numbers across our country.”.

Dr. Jha said the private market had not worked effectively to make testing more widely available, so it was “absolutely a requirement of the federal government to step in and make testing more widely available,” he said.

President Biden also announced new economic stimulus programs, saying he’s expanding loan programs to small businesses and streamlining the loan forgiveness process.

President Biden said he’s boosting help for overburdened hospitals, doubling the number of federal surge response teams sent to hard-hit areas to reduce the strain on local health care workers. He said he would increase the pace of antibody treatments to states by 50%.

“We made so much progress during the past 7 months of this pandemic. Even so, we remain at a critical moment, a critical time,” he said. “We have the tools. Now, we just have to finish the job with truth, with science, with confidence and together as one nation.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, including sweeping vaccine mandates that will affect 100 million American workers, nearly two-thirds of the country’s workforce.

“As your president, I’m announcing tonight a new plan to get more Americans vaccinated to combat those blocking public health,” he said Sept. 9.

As part of a six-part plan unveiled in a speech from the State Dining Room of the White House, President Biden said he would require vaccinations for nearly 4 million federal workers and the employees of companies that contract with the federal government.

He has also directed the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to develop a rule that will require large employers -- those with at least 100 employees -- to ensure their workers are vaccinated or tested weekly.

Nearly 17 million health care workers will face new vaccine mandates as part of the conditions of participation in the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

President Biden said the federal government will require staff at federally funded Head Start programs and schools to be vaccinated. He’s also calling on all states to mandate vaccines for teachers.

“A distinct minority of Americans, supported by a distinct minority of elected officials, are keeping us from turning the corner,” PresidentBiden said. “These pandemic politics, as I refer to them, are making people sick, causing unvaccinated people to die.”

One public health official said he was glad to see the president’s bold action.

“What I saw today was the federal government trying to use its powers to create greater safety in the American population,” said Ashish K. Jha, MD, dean of the school of public health at Brown University, Providence, R.I., in a call with reporters after the speech.

National Nurses United, the largest union of registered nurses in the United States, issued a statement in support of President Biden’s new vaccination requirements, but pushed back on his language.

“…as advocates for public health, registered nurses want to be extremely clear: There is no such thing as a pandemic of only the unvaccinated. The science of epidemiology tells us there is just one deadly, global pandemic that has not yet ended, and we are all in it together. To get out of it, we must act together. All of us,” the statement says.

A host of other professional groups, including the American Medical Association and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, also issued statements of support for President Biden’s plan.

But the plan was not well received by all.

“I will pursue every legal option available to the state of Georgia to stop this blatantly unlawful overreach by the Biden Administration,” said Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, a Republican, in a Tweet.

The National Council for Occupational Safety and Health called the plan “a missed opportunity” because it failed to include workplace protections for essential workers such as grocery, postal, and transit workers.

“Social distancing, improved ventilation, shift rotation, and protective equipment to reduce exposure are important components of an overall plan to reduce risk and stop the virus. These tools are missing from the new steps President Biden announced today,” said Jessica Martinez, co-executive director of the group.

In addition to the new vaccination requirements, President Biden said extra doses would be on the way for people who have already been fully vaccinated in order to protect against waning immunity, starting on Sept. 20. But he noted that those plans would be contingent on the Food and Drug Administration’s approval for third doses and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation of the shots.

President Biden pledged to use the Defense Production Act to ramp up production of at-home tests, which have been selling out across the nation as the Delta variant spreads.

He also announced plans to expand access to COVID-19 testing, including offering testing for free at thousands of pharmacies nationwide and getting major retailers to sell at-home COVID-19 tests at cost.

The BinaxNow test kit, which currently retails for $23.99, will now cost about $15 for two tests at Kroger, Amazon, and Walmart, according to the White House. Food banks and community health centers will get free tests, too.

He called on states to set up COVID-19 testing programs at all schools.

Jha said that in his view, the big, game-changing news out of the president’s speech was the expansion of testing.

“Our country has failed to deploy tests in a way that can really bring this pandemic under control,” Jha said. “There are plenty of reasons, data, experience to indicate that if these were widely available, it would make a dramatic difference in reducing infection numbers across our country.”.

Dr. Jha said the private market had not worked effectively to make testing more widely available, so it was “absolutely a requirement of the federal government to step in and make testing more widely available,” he said.

President Biden also announced new economic stimulus programs, saying he’s expanding loan programs to small businesses and streamlining the loan forgiveness process.

President Biden said he’s boosting help for overburdened hospitals, doubling the number of federal surge response teams sent to hard-hit areas to reduce the strain on local health care workers. He said he would increase the pace of antibody treatments to states by 50%.

“We made so much progress during the past 7 months of this pandemic. Even so, we remain at a critical moment, a critical time,” he said. “We have the tools. Now, we just have to finish the job with truth, with science, with confidence and together as one nation.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Long COVID could spell kidney troubles down the line

Physicians caring for COVID-19 survivors should routinely check kidney function, which is often damaged by the SARS-CoV-2 virus months after both severe and milder cases, new research indicates.

The largest study to date with the longest follow-up of COVID-19-related kidney outcomes also found that every type of kidney problem, including end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), was far more common in COVID-19 survivors who were admitted to the ICU or experienced acute kidney injury (AKI) while hospitalized.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Veterans Health Administration data from more than 1.7 million patients, including more than 89,000 who tested positive for COVID-19, for the study, which was published online Sept. 1, 2021, in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The risk of kidney problems “is more robust or pronounced in people who have had severe infection, but present in even asymptomatic and mild disease, which shouldn’t be discounted. Those people represent the majority of those with COVID-19,” said senior author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, of the Veteran Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

“That’s why the results are important, because even in people with mild disease to start with, the risk of kidney problems is not trivial,” he told this news organization. “It’s smaller than in people who were in the ICU, but it’s not ... zero.”

Experts aren’t yet certain how COVID-19 can damage the kidneys, hypothesizing that several factors may be at play. The virus may directly infect kidney cells rich in ACE2 receptors, which are key to infection, said nephrologist F. Perry Wilson, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a member of Medscape’s advisory board.

Kidneys might also be particularly vulnerable to the inflammatory cascade or blood clotting often seen in COVID-19, Dr. Al-Aly and Wilson both suggested.

COVID-19 survivors more likely to have kidney damage than controls

“A lot of health systems either have or are establishing post-COVID care clinics, which we think should definitely incorporate a kidney component,” Dr. Al-Aly advised. “They should check patients’ blood and urine for kidney problems.”

This is particularly important because “kidney problems, for the most part, are painless and silent,” he added.

“Realizing 2 years down the road that someone has ESKD, where they need dialysis or a kidney transplant, is what we don’t want. We don’t want this to be unrecognized, uncared for, unattended to,” he said.

Dr. Al-Aly and colleagues evaluated VA health system records, including data from 89,216 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2021, as well as 1.7 million controls who did not have COVID-19. Over a median follow-up of about 5.5 months, participants’ estimated glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine levels were tracked to assess kidney health and outcomes according to infection severity.

Results were striking, with COVID-19 survivors about one-third more likely than controls to have kidney damage or significant declines in kidney function between 1 and 6 months after infection. More than 4,700 COVID-19 survivors had lost at least 30% of their kidney function within a year, and these patients were 25% more likely to reach that level of decline than controls.

Additionally, COVID-19 survivors were nearly twice as likely to experience AKI and almost three times as likely to be diagnosed with ESKD as controls.

If your patient had COVID-19, ‘it’s reasonable to check kidney function’

“This information tells us that if your patient was sick with COVID-19 and comes for follow-up visits, it’s reasonable to check their kidney function,” Dr. Wilson, who was not involved with the research, told this news organization.

“Even for patients who were not hospitalized, if they were laid low or dehydrated ... it should be part of the post-COVID care package,” he said.

If just a fraction of the millions of COVID-19 survivors in the United States develop long-term kidney problems, the ripple effect on American health care could be substantial, Dr. Wilson and Dr. Al-Aly agreed.

“We’re still living in a pandemic, so it’s hard to tell the total impact,” Dr. Al-Aly said. “But this ultimately will contribute to a rise in burden of kidney disease. This and other long COVID manifestations are going to alter the landscape of clinical care and health care in the United States for a decade or more.”

Because renal problems can limit a patient’s treatment options for other major diseases, including diabetes and cancer, COVID-related kidney damage can ultimately impact survivability.

“There are a lot of medications you can’t use in people with advanced kidney problems,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

The main study limitation was that patients were mostly older White men (median age, 68 years), although more than 9,000 women were included in the VA data, Dr. Al-Aly noted. Additionally, controls were more likely to be younger, Black, living in long-term care, and have higher rates of chronic health conditions and medication use.

The experts agreed that ongoing research tracking kidney outcomes is crucial for years to come.

“We also need to be following a cohort of these patients as part of a research protocol where they come in every 6 months for a standard set of lab tests to really understand what’s going on with their kidneys,” Dr. Wilson said.

“Lastly – and a much tougher sell – is we need biopsies. It’s very hard to infer what’s going on in complex disease with the kidneys without biopsy tissue,” he added.

The study was funded by the American Society of Nephrology and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Al-Aly and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians caring for COVID-19 survivors should routinely check kidney function, which is often damaged by the SARS-CoV-2 virus months after both severe and milder cases, new research indicates.

The largest study to date with the longest follow-up of COVID-19-related kidney outcomes also found that every type of kidney problem, including end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), was far more common in COVID-19 survivors who were admitted to the ICU or experienced acute kidney injury (AKI) while hospitalized.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Veterans Health Administration data from more than 1.7 million patients, including more than 89,000 who tested positive for COVID-19, for the study, which was published online Sept. 1, 2021, in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The risk of kidney problems “is more robust or pronounced in people who have had severe infection, but present in even asymptomatic and mild disease, which shouldn’t be discounted. Those people represent the majority of those with COVID-19,” said senior author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, of the Veteran Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

“That’s why the results are important, because even in people with mild disease to start with, the risk of kidney problems is not trivial,” he told this news organization. “It’s smaller than in people who were in the ICU, but it’s not ... zero.”

Experts aren’t yet certain how COVID-19 can damage the kidneys, hypothesizing that several factors may be at play. The virus may directly infect kidney cells rich in ACE2 receptors, which are key to infection, said nephrologist F. Perry Wilson, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a member of Medscape’s advisory board.

Kidneys might also be particularly vulnerable to the inflammatory cascade or blood clotting often seen in COVID-19, Dr. Al-Aly and Wilson both suggested.

COVID-19 survivors more likely to have kidney damage than controls

“A lot of health systems either have or are establishing post-COVID care clinics, which we think should definitely incorporate a kidney component,” Dr. Al-Aly advised. “They should check patients’ blood and urine for kidney problems.”

This is particularly important because “kidney problems, for the most part, are painless and silent,” he added.

“Realizing 2 years down the road that someone has ESKD, where they need dialysis or a kidney transplant, is what we don’t want. We don’t want this to be unrecognized, uncared for, unattended to,” he said.

Dr. Al-Aly and colleagues evaluated VA health system records, including data from 89,216 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2021, as well as 1.7 million controls who did not have COVID-19. Over a median follow-up of about 5.5 months, participants’ estimated glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine levels were tracked to assess kidney health and outcomes according to infection severity.

Results were striking, with COVID-19 survivors about one-third more likely than controls to have kidney damage or significant declines in kidney function between 1 and 6 months after infection. More than 4,700 COVID-19 survivors had lost at least 30% of their kidney function within a year, and these patients were 25% more likely to reach that level of decline than controls.

Additionally, COVID-19 survivors were nearly twice as likely to experience AKI and almost three times as likely to be diagnosed with ESKD as controls.

If your patient had COVID-19, ‘it’s reasonable to check kidney function’

“This information tells us that if your patient was sick with COVID-19 and comes for follow-up visits, it’s reasonable to check their kidney function,” Dr. Wilson, who was not involved with the research, told this news organization.

“Even for patients who were not hospitalized, if they were laid low or dehydrated ... it should be part of the post-COVID care package,” he said.

If just a fraction of the millions of COVID-19 survivors in the United States develop long-term kidney problems, the ripple effect on American health care could be substantial, Dr. Wilson and Dr. Al-Aly agreed.

“We’re still living in a pandemic, so it’s hard to tell the total impact,” Dr. Al-Aly said. “But this ultimately will contribute to a rise in burden of kidney disease. This and other long COVID manifestations are going to alter the landscape of clinical care and health care in the United States for a decade or more.”

Because renal problems can limit a patient’s treatment options for other major diseases, including diabetes and cancer, COVID-related kidney damage can ultimately impact survivability.

“There are a lot of medications you can’t use in people with advanced kidney problems,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

The main study limitation was that patients were mostly older White men (median age, 68 years), although more than 9,000 women were included in the VA data, Dr. Al-Aly noted. Additionally, controls were more likely to be younger, Black, living in long-term care, and have higher rates of chronic health conditions and medication use.

The experts agreed that ongoing research tracking kidney outcomes is crucial for years to come.

“We also need to be following a cohort of these patients as part of a research protocol where they come in every 6 months for a standard set of lab tests to really understand what’s going on with their kidneys,” Dr. Wilson said.

“Lastly – and a much tougher sell – is we need biopsies. It’s very hard to infer what’s going on in complex disease with the kidneys without biopsy tissue,” he added.

The study was funded by the American Society of Nephrology and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Al-Aly and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians caring for COVID-19 survivors should routinely check kidney function, which is often damaged by the SARS-CoV-2 virus months after both severe and milder cases, new research indicates.

The largest study to date with the longest follow-up of COVID-19-related kidney outcomes also found that every type of kidney problem, including end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), was far more common in COVID-19 survivors who were admitted to the ICU or experienced acute kidney injury (AKI) while hospitalized.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Veterans Health Administration data from more than 1.7 million patients, including more than 89,000 who tested positive for COVID-19, for the study, which was published online Sept. 1, 2021, in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The risk of kidney problems “is more robust or pronounced in people who have had severe infection, but present in even asymptomatic and mild disease, which shouldn’t be discounted. Those people represent the majority of those with COVID-19,” said senior author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, of the Veteran Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

“That’s why the results are important, because even in people with mild disease to start with, the risk of kidney problems is not trivial,” he told this news organization. “It’s smaller than in people who were in the ICU, but it’s not ... zero.”

Experts aren’t yet certain how COVID-19 can damage the kidneys, hypothesizing that several factors may be at play. The virus may directly infect kidney cells rich in ACE2 receptors, which are key to infection, said nephrologist F. Perry Wilson, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a member of Medscape’s advisory board.

Kidneys might also be particularly vulnerable to the inflammatory cascade or blood clotting often seen in COVID-19, Dr. Al-Aly and Wilson both suggested.

COVID-19 survivors more likely to have kidney damage than controls

“A lot of health systems either have or are establishing post-COVID care clinics, which we think should definitely incorporate a kidney component,” Dr. Al-Aly advised. “They should check patients’ blood and urine for kidney problems.”

This is particularly important because “kidney problems, for the most part, are painless and silent,” he added.

“Realizing 2 years down the road that someone has ESKD, where they need dialysis or a kidney transplant, is what we don’t want. We don’t want this to be unrecognized, uncared for, unattended to,” he said.

Dr. Al-Aly and colleagues evaluated VA health system records, including data from 89,216 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2021, as well as 1.7 million controls who did not have COVID-19. Over a median follow-up of about 5.5 months, participants’ estimated glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine levels were tracked to assess kidney health and outcomes according to infection severity.

Results were striking, with COVID-19 survivors about one-third more likely than controls to have kidney damage or significant declines in kidney function between 1 and 6 months after infection. More than 4,700 COVID-19 survivors had lost at least 30% of their kidney function within a year, and these patients were 25% more likely to reach that level of decline than controls.

Additionally, COVID-19 survivors were nearly twice as likely to experience AKI and almost three times as likely to be diagnosed with ESKD as controls.

If your patient had COVID-19, ‘it’s reasonable to check kidney function’

“This information tells us that if your patient was sick with COVID-19 and comes for follow-up visits, it’s reasonable to check their kidney function,” Dr. Wilson, who was not involved with the research, told this news organization.

“Even for patients who were not hospitalized, if they were laid low or dehydrated ... it should be part of the post-COVID care package,” he said.

If just a fraction of the millions of COVID-19 survivors in the United States develop long-term kidney problems, the ripple effect on American health care could be substantial, Dr. Wilson and Dr. Al-Aly agreed.

“We’re still living in a pandemic, so it’s hard to tell the total impact,” Dr. Al-Aly said. “But this ultimately will contribute to a rise in burden of kidney disease. This and other long COVID manifestations are going to alter the landscape of clinical care and health care in the United States for a decade or more.”

Because renal problems can limit a patient’s treatment options for other major diseases, including diabetes and cancer, COVID-related kidney damage can ultimately impact survivability.

“There are a lot of medications you can’t use in people with advanced kidney problems,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

The main study limitation was that patients were mostly older White men (median age, 68 years), although more than 9,000 women were included in the VA data, Dr. Al-Aly noted. Additionally, controls were more likely to be younger, Black, living in long-term care, and have higher rates of chronic health conditions and medication use.

The experts agreed that ongoing research tracking kidney outcomes is crucial for years to come.

“We also need to be following a cohort of these patients as part of a research protocol where they come in every 6 months for a standard set of lab tests to really understand what’s going on with their kidneys,” Dr. Wilson said.

“Lastly – and a much tougher sell – is we need biopsies. It’s very hard to infer what’s going on in complex disease with the kidneys without biopsy tissue,” he added.

The study was funded by the American Society of Nephrology and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Al-Aly and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Elderly mice receive the gift of warmth

Steal from the warm, give to the cold

If there’s one constant in life other than taxes, it’s elderly people moving to Florida. The Sunshine State’s reputation as a giant retirement home needs no elaboration, but why do senior citizens gravitate there? Well, many reasons, but a big one is that, the older you get, the more susceptible and sensitive you are to the cold. And now, according to a new study, we may have identified a culprit.

Researchers from Yale University examined a group of mice and found that the older ones lacked ICL2 cells in their fatty tissue. These cells, at least in younger mice, help restore body heat when exposed to cold temperatures. Lacking these cells meant that older mice had a limited ability to burn their fat and raise their temperature in response to cold.

Well, job done, all we need to do now is stimulate production of ICL2 cells in elderly people, and they’ll be able to go outside in 80-degree weather without a sweater again. Except there’s a problem. In a cruel twist of fate, when the elderly mice were given a molecule to boost ICL2 cell production, they actually became less tolerant of the cold than at baseline. Oops.

The scientists didn’t give up though, and gave their elderly mice ICL2 cells from young mice. This finally did the trick, though we have to admit, if that treatment does eventually scale up to humans, the prospect of a bunch of senior citizens taking ICL2 cells from young people to stay warm does sound a bit like a bad vampire movie premise. “I vant to suck your immune cell group 2 innate lymphoid cells!” Not the most pithy catch phrase in the world.

Grocery store tapping your subconscious? It’s a good thing

We all know there’s marketing and functionality elements to grocery stores and how they’re set up for your shopping pleasure. But what if I told you that the good old supermarket subconscious trick works on how healthy food decisions are?

In a recent study, researchers at the University of Southampton in England found that if you placed a wider selection of fruits and vegetables near the entrances and more nonfood items near checkouts, sales decreased on the sweets and increased on the produce. “The findings of our study suggest that a healthier store layout could lead to nearly 10,000 extra portions of fruit and vegetables and approximately 1,500 fewer portions of confectionery being sold on a weekly basis in each store,” lead author Dr. Christina Vogel explained.

You’re probably thinking that food placement studies aren’t new. That’s true, but this one went above and beyond. Instead of just looking at the influence placement has on purchase, this one took it further by trying to reduce the consumers’ “calorie opportunities” and examining the effect on sales. Also, customer loyalty, patterns, and diets were taken into account across multiple household members.

The researchers think shifting the layouts in grocery stores could shift people’s food choices, producing a domino effect on the population’s overall diet. With obesity, diabetes, and cardiology concerns always looming, swaying consumers toward healthier food choices makes for better public health overall.

So if you feel like you’re being subconsciously assaulted by veggies every time you walk into Trader Joe’s, just know it’s for your own good.

TikTokers take on tics

We know TikTok is what makes a lot of teens and young adults tick, but what if TikTokers are actually catching tic disorders from other TikTokers?

TikTok blew up during the pandemic. Many people were stuck at home and had nothing better to do than make and watch TikTok videos. The pandemic brought isolation, uncertainty, and anxiety. The stress that followed may have caused many people, mostly women and young girls, to develop tic disorders.

There’s a TikTok for everything, whether it’s a new dance or a recipe. Many people even use TikTok to speak out about their illnesses. Several TikTokers have Tourette’s syndrome and show their tics on their videos. It appears that some audience members actually “catch” the tics from watching the videos and are then unable to stop certain jerking movements or saying specific words.

Neurologists at the University of Calgary (Alta.), who were hearing from colleagues and getting referrals of such patients, called it “an epidemic within the pandemic.” The behavior is not actually Tourette’s, they told Vice, but the patients “cannot stop, and we have absolutely witnessed that.”

There is, of course, controversy over the issue. One individual with the condition said, “I feel like there’s a lot of really weird, backwards stigma on TikTok about tic disorders. Like, you aren’t allowed to have one unless it’s this one.”

Who would have guessed that people would disagree over stuff on the Internet?

Look on the bright side: Obesity edition

The pandemic may have postponed “Top Gun: Maverick” and “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” until who-knows-when, but we here at LOTME are happy to announce the nearly-as-anticipated return of Bacteria vs. the World.

As you may recall from our last edition of BVTW, bacteria battled the ghost of Charles Darwin, who had taken the earthly form of antibiotics capable of stopping bacterial evolution. Tonight, our prokaryotic protagonists take on an equally relentless and ubiquitous challenger: obesity.

Specifically, we’re putting bacteria up against the obesity survival paradox, that phenomenon in which obesity and overweight seem to protect against – yes, you guessed it – bacterial infections.

A Swedish research team observed a group of 2,196 individual adults who received care for suspected severe bacterial infection at Skaraborg Hospital in Skövde. One year after hospitalization, 26% of normal-weight (body mass index, 18.5-24.99) patients were dead, compared with 17% of overweight (BMI, 25.0-29.99), 16% of obese (BMI, 30.0-34.99), and 9% of very obese (BMI >35) patients.

These results confirm the obesity survival paradox, but “what we don’t know is how being overweight can benefit the patient with a bacterial infection, or whether it’s connected with functions in the immune system and how they’re regulated,” lead author Dr. Åsa Alsiö said in a written statement.

A spokes-cell for the bacteria disputed the results and challenged the legitimacy of the investigators. When asked if there should be some sort of reexamination of the findings, he/she/it replied: “You bet your flagella.” We then pointed out that humans don’t have flagellum, and the representative raised his/her/its flagella in what could only be considered an obscene gesture.

Steal from the warm, give to the cold

If there’s one constant in life other than taxes, it’s elderly people moving to Florida. The Sunshine State’s reputation as a giant retirement home needs no elaboration, but why do senior citizens gravitate there? Well, many reasons, but a big one is that, the older you get, the more susceptible and sensitive you are to the cold. And now, according to a new study, we may have identified a culprit.

Researchers from Yale University examined a group of mice and found that the older ones lacked ICL2 cells in their fatty tissue. These cells, at least in younger mice, help restore body heat when exposed to cold temperatures. Lacking these cells meant that older mice had a limited ability to burn their fat and raise their temperature in response to cold.

Well, job done, all we need to do now is stimulate production of ICL2 cells in elderly people, and they’ll be able to go outside in 80-degree weather without a sweater again. Except there’s a problem. In a cruel twist of fate, when the elderly mice were given a molecule to boost ICL2 cell production, they actually became less tolerant of the cold than at baseline. Oops.

The scientists didn’t give up though, and gave their elderly mice ICL2 cells from young mice. This finally did the trick, though we have to admit, if that treatment does eventually scale up to humans, the prospect of a bunch of senior citizens taking ICL2 cells from young people to stay warm does sound a bit like a bad vampire movie premise. “I vant to suck your immune cell group 2 innate lymphoid cells!” Not the most pithy catch phrase in the world.

Grocery store tapping your subconscious? It’s a good thing

We all know there’s marketing and functionality elements to grocery stores and how they’re set up for your shopping pleasure. But what if I told you that the good old supermarket subconscious trick works on how healthy food decisions are?

In a recent study, researchers at the University of Southampton in England found that if you placed a wider selection of fruits and vegetables near the entrances and more nonfood items near checkouts, sales decreased on the sweets and increased on the produce. “The findings of our study suggest that a healthier store layout could lead to nearly 10,000 extra portions of fruit and vegetables and approximately 1,500 fewer portions of confectionery being sold on a weekly basis in each store,” lead author Dr. Christina Vogel explained.

You’re probably thinking that food placement studies aren’t new. That’s true, but this one went above and beyond. Instead of just looking at the influence placement has on purchase, this one took it further by trying to reduce the consumers’ “calorie opportunities” and examining the effect on sales. Also, customer loyalty, patterns, and diets were taken into account across multiple household members.

The researchers think shifting the layouts in grocery stores could shift people’s food choices, producing a domino effect on the population’s overall diet. With obesity, diabetes, and cardiology concerns always looming, swaying consumers toward healthier food choices makes for better public health overall.

So if you feel like you’re being subconsciously assaulted by veggies every time you walk into Trader Joe’s, just know it’s for your own good.

TikTokers take on tics

We know TikTok is what makes a lot of teens and young adults tick, but what if TikTokers are actually catching tic disorders from other TikTokers?

TikTok blew up during the pandemic. Many people were stuck at home and had nothing better to do than make and watch TikTok videos. The pandemic brought isolation, uncertainty, and anxiety. The stress that followed may have caused many people, mostly women and young girls, to develop tic disorders.

There’s a TikTok for everything, whether it’s a new dance or a recipe. Many people even use TikTok to speak out about their illnesses. Several TikTokers have Tourette’s syndrome and show their tics on their videos. It appears that some audience members actually “catch” the tics from watching the videos and are then unable to stop certain jerking movements or saying specific words.

Neurologists at the University of Calgary (Alta.), who were hearing from colleagues and getting referrals of such patients, called it “an epidemic within the pandemic.” The behavior is not actually Tourette’s, they told Vice, but the patients “cannot stop, and we have absolutely witnessed that.”

There is, of course, controversy over the issue. One individual with the condition said, “I feel like there’s a lot of really weird, backwards stigma on TikTok about tic disorders. Like, you aren’t allowed to have one unless it’s this one.”

Who would have guessed that people would disagree over stuff on the Internet?

Look on the bright side: Obesity edition

The pandemic may have postponed “Top Gun: Maverick” and “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” until who-knows-when, but we here at LOTME are happy to announce the nearly-as-anticipated return of Bacteria vs. the World.

As you may recall from our last edition of BVTW, bacteria battled the ghost of Charles Darwin, who had taken the earthly form of antibiotics capable of stopping bacterial evolution. Tonight, our prokaryotic protagonists take on an equally relentless and ubiquitous challenger: obesity.

Specifically, we’re putting bacteria up against the obesity survival paradox, that phenomenon in which obesity and overweight seem to protect against – yes, you guessed it – bacterial infections.

A Swedish research team observed a group of 2,196 individual adults who received care for suspected severe bacterial infection at Skaraborg Hospital in Skövde. One year after hospitalization, 26% of normal-weight (body mass index, 18.5-24.99) patients were dead, compared with 17% of overweight (BMI, 25.0-29.99), 16% of obese (BMI, 30.0-34.99), and 9% of very obese (BMI >35) patients.

These results confirm the obesity survival paradox, but “what we don’t know is how being overweight can benefit the patient with a bacterial infection, or whether it’s connected with functions in the immune system and how they’re regulated,” lead author Dr. Åsa Alsiö said in a written statement.

A spokes-cell for the bacteria disputed the results and challenged the legitimacy of the investigators. When asked if there should be some sort of reexamination of the findings, he/she/it replied: “You bet your flagella.” We then pointed out that humans don’t have flagellum, and the representative raised his/her/its flagella in what could only be considered an obscene gesture.

Steal from the warm, give to the cold

If there’s one constant in life other than taxes, it’s elderly people moving to Florida. The Sunshine State’s reputation as a giant retirement home needs no elaboration, but why do senior citizens gravitate there? Well, many reasons, but a big one is that, the older you get, the more susceptible and sensitive you are to the cold. And now, according to a new study, we may have identified a culprit.

Researchers from Yale University examined a group of mice and found that the older ones lacked ICL2 cells in their fatty tissue. These cells, at least in younger mice, help restore body heat when exposed to cold temperatures. Lacking these cells meant that older mice had a limited ability to burn their fat and raise their temperature in response to cold.

Well, job done, all we need to do now is stimulate production of ICL2 cells in elderly people, and they’ll be able to go outside in 80-degree weather without a sweater again. Except there’s a problem. In a cruel twist of fate, when the elderly mice were given a molecule to boost ICL2 cell production, they actually became less tolerant of the cold than at baseline. Oops.

The scientists didn’t give up though, and gave their elderly mice ICL2 cells from young mice. This finally did the trick, though we have to admit, if that treatment does eventually scale up to humans, the prospect of a bunch of senior citizens taking ICL2 cells from young people to stay warm does sound a bit like a bad vampire movie premise. “I vant to suck your immune cell group 2 innate lymphoid cells!” Not the most pithy catch phrase in the world.

Grocery store tapping your subconscious? It’s a good thing

We all know there’s marketing and functionality elements to grocery stores and how they’re set up for your shopping pleasure. But what if I told you that the good old supermarket subconscious trick works on how healthy food decisions are?

In a recent study, researchers at the University of Southampton in England found that if you placed a wider selection of fruits and vegetables near the entrances and more nonfood items near checkouts, sales decreased on the sweets and increased on the produce. “The findings of our study suggest that a healthier store layout could lead to nearly 10,000 extra portions of fruit and vegetables and approximately 1,500 fewer portions of confectionery being sold on a weekly basis in each store,” lead author Dr. Christina Vogel explained.

You’re probably thinking that food placement studies aren’t new. That’s true, but this one went above and beyond. Instead of just looking at the influence placement has on purchase, this one took it further by trying to reduce the consumers’ “calorie opportunities” and examining the effect on sales. Also, customer loyalty, patterns, and diets were taken into account across multiple household members.

The researchers think shifting the layouts in grocery stores could shift people’s food choices, producing a domino effect on the population’s overall diet. With obesity, diabetes, and cardiology concerns always looming, swaying consumers toward healthier food choices makes for better public health overall.

So if you feel like you’re being subconsciously assaulted by veggies every time you walk into Trader Joe’s, just know it’s for your own good.

TikTokers take on tics

We know TikTok is what makes a lot of teens and young adults tick, but what if TikTokers are actually catching tic disorders from other TikTokers?

TikTok blew up during the pandemic. Many people were stuck at home and had nothing better to do than make and watch TikTok videos. The pandemic brought isolation, uncertainty, and anxiety. The stress that followed may have caused many people, mostly women and young girls, to develop tic disorders.

There’s a TikTok for everything, whether it’s a new dance or a recipe. Many people even use TikTok to speak out about their illnesses. Several TikTokers have Tourette’s syndrome and show their tics on their videos. It appears that some audience members actually “catch” the tics from watching the videos and are then unable to stop certain jerking movements or saying specific words.

Neurologists at the University of Calgary (Alta.), who were hearing from colleagues and getting referrals of such patients, called it “an epidemic within the pandemic.” The behavior is not actually Tourette’s, they told Vice, but the patients “cannot stop, and we have absolutely witnessed that.”

There is, of course, controversy over the issue. One individual with the condition said, “I feel like there’s a lot of really weird, backwards stigma on TikTok about tic disorders. Like, you aren’t allowed to have one unless it’s this one.”

Who would have guessed that people would disagree over stuff on the Internet?

Look on the bright side: Obesity edition

The pandemic may have postponed “Top Gun: Maverick” and “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” until who-knows-when, but we here at LOTME are happy to announce the nearly-as-anticipated return of Bacteria vs. the World.

As you may recall from our last edition of BVTW, bacteria battled the ghost of Charles Darwin, who had taken the earthly form of antibiotics capable of stopping bacterial evolution. Tonight, our prokaryotic protagonists take on an equally relentless and ubiquitous challenger: obesity.

Specifically, we’re putting bacteria up against the obesity survival paradox, that phenomenon in which obesity and overweight seem to protect against – yes, you guessed it – bacterial infections.

A Swedish research team observed a group of 2,196 individual adults who received care for suspected severe bacterial infection at Skaraborg Hospital in Skövde. One year after hospitalization, 26% of normal-weight (body mass index, 18.5-24.99) patients were dead, compared with 17% of overweight (BMI, 25.0-29.99), 16% of obese (BMI, 30.0-34.99), and 9% of very obese (BMI >35) patients.

These results confirm the obesity survival paradox, but “what we don’t know is how being overweight can benefit the patient with a bacterial infection, or whether it’s connected with functions in the immune system and how they’re regulated,” lead author Dr. Åsa Alsiö said in a written statement.

A spokes-cell for the bacteria disputed the results and challenged the legitimacy of the investigators. When asked if there should be some sort of reexamination of the findings, he/she/it replied: “You bet your flagella.” We then pointed out that humans don’t have flagellum, and the representative raised his/her/its flagella in what could only be considered an obscene gesture.

Walking 7,000 steps per day may be enough to reduce mortality risk

based on prospective data from more than 2,000 people.

Findings were consistent regardless of race or sex, and step intensity had no impact on mortality risk, reported lead author Amanda E. Paluch, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and colleagues.

“In response to the need for empirical data on the associations of step volume and intensity with mortality in younger and diverse populations, we conducted a prospective study in middle-aged Black and White adults followed up for mortality for approximately 11 years,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Network Open. “The objectives of our study were to examine the associations of step volume and intensity with mortality overall and by race and sex.”

Steps per day is easy to communicate

Dr. Paluch noted that steps per day is a “very appealing metric to quantify activity,” for both researchers and laypeople.

“Steps per day is simple and easy to communicate in public health and clinical settings,” Dr. Paluch said in an interview. “Additionally, the dramatic growth of wearable devices measuring steps makes it appealing and broadens the reach of promoting physical activity to many individuals. Walking is an activity that most of the general population can pursue. It can also be accumulated throughout daily living and may seem more achievable to fit into busy lives than a structured exercise session.”

The present investigation was conducted as part of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. The dataset included 2,110 participants ranging from 38-50 years of age, with a mean age of 45.2 years. A slightly higher proportion of the subjects were women (57.1%) and White (57.9%).

All participants wore an ActiGraph 7164 accelerometer for 1 week and were then followed for death of any cause, with a mean follow-up of 10.8 years. Multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models included a range of covariates, such as smoking history, body weight, alcohol intake, blood pressure, total cholesterol, and others. Step counts were grouped into low (less than 7,000 steps per day), moderate (7,000-9,999), and high (at least 10,000 steps per day) categories.

Compared with individuals who took less than 7,000 steps per day, those who took 7,000-9,000 steps per day had a 72% reduced risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.54). Going beyond 10,000 steps appeared to add no benefit, based on a 55% lower risk of all-cause mortality in the highly active group, compared with those taking less than 7,000 steps per day (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.25-0.81).

Walking faster didn’t appear to help either, as stepping intensity was not associated with mortality risk; however, Dr. Paluch urged a cautious interpretation of this finding, calling it “inconclusive,” and suggesting that more research is needed.

“It is also important to note that this study only looked at premature all-cause mortality, and therefore the results may be different for other health outcomes, such as the risk of cardiovascular disease, or diabetes, cancer, or mental health outcomes,” Dr. Paluch said.

“The results from our study demonstrated that those who are least active have the most to gain,” Dr. Paluch said. “Even small incremental increases in steps per day are associated with a lower mortality risk during middle age. A walking plan that gradually works up toward 7,000-10,000 steps per day in middle-aged adults may have health benefits and lower the risk of premature mortality.”

Causality cannot be confirmed

According to Raed A. Joundi, MD, DPhil, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), the study size, diverse population, and length of follow-up should increase confidence in the findings, although a causal relationship remains elusive.

“As this study is observational, causality between step count and mortality cannot be confirmed; however, the authors accounted for many factors, and the association was consistent in different analyses and with prior literature,” Dr. Joundi said in an interview. “The authors did not assess the risk of other important events like stroke and heart attack, and these could be addressed in a future study.”

Dr. Joundi, who recently published a study linking exercise with a 50% reduction in mortality after stroke, noted that “physical activity has innumerable benefits, and it’s important that people engage in activity that can be regular and consistent, regardless of the type or intensity.”

To this end, he highlighted the use of “devices capable of monitoring step count, which can be an important motivational tool,” and suggested that these findings may bring a sigh of relief to step counters who come up a little short on a common daily goal.

“A target of 10,000 steps is often used for public health promotion, and this study now provides convincing observational evidence that it may be an optimal step count target for mortality reduction,” Dr. Joundi said. “However, if 10,000 steps per day is not feasible, 7,000 steps seems to be a very reasonable target given its association with markedly lower mortality in this study.”

Not all step counters are equal

Unfortunately, such recommendations are complicated by uncertainty in measurement, as widely used step counting devices, like smart watches, may not yield the same results as research-grade accelerometers, according to Nicole L. Spartano, PhD, of Boston University.

“Many comparison studies have been conducted in laboratory settings among young healthy adults, but these do not necessarily reflect real-life wear experiences that will be generalizable to the population as a whole,” Dr. Spartano wrote in an accompanying editorial.

She called for large-scale comparison studies to compare research-grade and consumer devices.

“The reason for conducting comparison studies is not to develop distinct guidelines for different devices or subgroups of the population, but rather to understand the variability so that we can develop one clear message that is most appropriate to the public,” Dr. Spartano wrote. “Some devices may have bias in terms of step measurement at different activity intensity and may not record steps as accurately in older adults or individuals with obesity or mobility disorders. For example, when adults who were obese wore an ActiGraph monitor in a laboratory setting, the device only recorded 80% of steps walked at a moderate pace, while other devices recorded close to 100% of steps walked. If we in the public health community are to move toward using these devices more for physical activity prescription, these details will need to be explored in more depth.”

CARDIA was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Northwestern University, the University of Minnesota, and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Some study authors received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Dr Spartano disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk, the American Heart Association, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Joundi and Dr. Paluch disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

based on prospective data from more than 2,000 people.

Findings were consistent regardless of race or sex, and step intensity had no impact on mortality risk, reported lead author Amanda E. Paluch, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and colleagues.

“In response to the need for empirical data on the associations of step volume and intensity with mortality in younger and diverse populations, we conducted a prospective study in middle-aged Black and White adults followed up for mortality for approximately 11 years,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Network Open. “The objectives of our study were to examine the associations of step volume and intensity with mortality overall and by race and sex.”

Steps per day is easy to communicate

Dr. Paluch noted that steps per day is a “very appealing metric to quantify activity,” for both researchers and laypeople.

“Steps per day is simple and easy to communicate in public health and clinical settings,” Dr. Paluch said in an interview. “Additionally, the dramatic growth of wearable devices measuring steps makes it appealing and broadens the reach of promoting physical activity to many individuals. Walking is an activity that most of the general population can pursue. It can also be accumulated throughout daily living and may seem more achievable to fit into busy lives than a structured exercise session.”

The present investigation was conducted as part of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. The dataset included 2,110 participants ranging from 38-50 years of age, with a mean age of 45.2 years. A slightly higher proportion of the subjects were women (57.1%) and White (57.9%).

All participants wore an ActiGraph 7164 accelerometer for 1 week and were then followed for death of any cause, with a mean follow-up of 10.8 years. Multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models included a range of covariates, such as smoking history, body weight, alcohol intake, blood pressure, total cholesterol, and others. Step counts were grouped into low (less than 7,000 steps per day), moderate (7,000-9,999), and high (at least 10,000 steps per day) categories.

Compared with individuals who took less than 7,000 steps per day, those who took 7,000-9,000 steps per day had a 72% reduced risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.54). Going beyond 10,000 steps appeared to add no benefit, based on a 55% lower risk of all-cause mortality in the highly active group, compared with those taking less than 7,000 steps per day (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.25-0.81).

Walking faster didn’t appear to help either, as stepping intensity was not associated with mortality risk; however, Dr. Paluch urged a cautious interpretation of this finding, calling it “inconclusive,” and suggesting that more research is needed.

“It is also important to note that this study only looked at premature all-cause mortality, and therefore the results may be different for other health outcomes, such as the risk of cardiovascular disease, or diabetes, cancer, or mental health outcomes,” Dr. Paluch said.

“The results from our study demonstrated that those who are least active have the most to gain,” Dr. Paluch said. “Even small incremental increases in steps per day are associated with a lower mortality risk during middle age. A walking plan that gradually works up toward 7,000-10,000 steps per day in middle-aged adults may have health benefits and lower the risk of premature mortality.”

Causality cannot be confirmed

According to Raed A. Joundi, MD, DPhil, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), the study size, diverse population, and length of follow-up should increase confidence in the findings, although a causal relationship remains elusive.

“As this study is observational, causality between step count and mortality cannot be confirmed; however, the authors accounted for many factors, and the association was consistent in different analyses and with prior literature,” Dr. Joundi said in an interview. “The authors did not assess the risk of other important events like stroke and heart attack, and these could be addressed in a future study.”

Dr. Joundi, who recently published a study linking exercise with a 50% reduction in mortality after stroke, noted that “physical activity has innumerable benefits, and it’s important that people engage in activity that can be regular and consistent, regardless of the type or intensity.”

To this end, he highlighted the use of “devices capable of monitoring step count, which can be an important motivational tool,” and suggested that these findings may bring a sigh of relief to step counters who come up a little short on a common daily goal.

“A target of 10,000 steps is often used for public health promotion, and this study now provides convincing observational evidence that it may be an optimal step count target for mortality reduction,” Dr. Joundi said. “However, if 10,000 steps per day is not feasible, 7,000 steps seems to be a very reasonable target given its association with markedly lower mortality in this study.”

Not all step counters are equal

Unfortunately, such recommendations are complicated by uncertainty in measurement, as widely used step counting devices, like smart watches, may not yield the same results as research-grade accelerometers, according to Nicole L. Spartano, PhD, of Boston University.

“Many comparison studies have been conducted in laboratory settings among young healthy adults, but these do not necessarily reflect real-life wear experiences that will be generalizable to the population as a whole,” Dr. Spartano wrote in an accompanying editorial.

She called for large-scale comparison studies to compare research-grade and consumer devices.

“The reason for conducting comparison studies is not to develop distinct guidelines for different devices or subgroups of the population, but rather to understand the variability so that we can develop one clear message that is most appropriate to the public,” Dr. Spartano wrote. “Some devices may have bias in terms of step measurement at different activity intensity and may not record steps as accurately in older adults or individuals with obesity or mobility disorders. For example, when adults who were obese wore an ActiGraph monitor in a laboratory setting, the device only recorded 80% of steps walked at a moderate pace, while other devices recorded close to 100% of steps walked. If we in the public health community are to move toward using these devices more for physical activity prescription, these details will need to be explored in more depth.”

CARDIA was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Northwestern University, the University of Minnesota, and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Some study authors received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Dr Spartano disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk, the American Heart Association, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Joundi and Dr. Paluch disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

based on prospective data from more than 2,000 people.

Findings were consistent regardless of race or sex, and step intensity had no impact on mortality risk, reported lead author Amanda E. Paluch, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and colleagues.

“In response to the need for empirical data on the associations of step volume and intensity with mortality in younger and diverse populations, we conducted a prospective study in middle-aged Black and White adults followed up for mortality for approximately 11 years,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Network Open. “The objectives of our study were to examine the associations of step volume and intensity with mortality overall and by race and sex.”

Steps per day is easy to communicate

Dr. Paluch noted that steps per day is a “very appealing metric to quantify activity,” for both researchers and laypeople.

“Steps per day is simple and easy to communicate in public health and clinical settings,” Dr. Paluch said in an interview. “Additionally, the dramatic growth of wearable devices measuring steps makes it appealing and broadens the reach of promoting physical activity to many individuals. Walking is an activity that most of the general population can pursue. It can also be accumulated throughout daily living and may seem more achievable to fit into busy lives than a structured exercise session.”

The present investigation was conducted as part of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. The dataset included 2,110 participants ranging from 38-50 years of age, with a mean age of 45.2 years. A slightly higher proportion of the subjects were women (57.1%) and White (57.9%).

All participants wore an ActiGraph 7164 accelerometer for 1 week and were then followed for death of any cause, with a mean follow-up of 10.8 years. Multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models included a range of covariates, such as smoking history, body weight, alcohol intake, blood pressure, total cholesterol, and others. Step counts were grouped into low (less than 7,000 steps per day), moderate (7,000-9,999), and high (at least 10,000 steps per day) categories.

Compared with individuals who took less than 7,000 steps per day, those who took 7,000-9,000 steps per day had a 72% reduced risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.54). Going beyond 10,000 steps appeared to add no benefit, based on a 55% lower risk of all-cause mortality in the highly active group, compared with those taking less than 7,000 steps per day (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.25-0.81).

Walking faster didn’t appear to help either, as stepping intensity was not associated with mortality risk; however, Dr. Paluch urged a cautious interpretation of this finding, calling it “inconclusive,” and suggesting that more research is needed.

“It is also important to note that this study only looked at premature all-cause mortality, and therefore the results may be different for other health outcomes, such as the risk of cardiovascular disease, or diabetes, cancer, or mental health outcomes,” Dr. Paluch said.

“The results from our study demonstrated that those who are least active have the most to gain,” Dr. Paluch said. “Even small incremental increases in steps per day are associated with a lower mortality risk during middle age. A walking plan that gradually works up toward 7,000-10,000 steps per day in middle-aged adults may have health benefits and lower the risk of premature mortality.”

Causality cannot be confirmed

According to Raed A. Joundi, MD, DPhil, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), the study size, diverse population, and length of follow-up should increase confidence in the findings, although a causal relationship remains elusive.

“As this study is observational, causality between step count and mortality cannot be confirmed; however, the authors accounted for many factors, and the association was consistent in different analyses and with prior literature,” Dr. Joundi said in an interview. “The authors did not assess the risk of other important events like stroke and heart attack, and these could be addressed in a future study.”

Dr. Joundi, who recently published a study linking exercise with a 50% reduction in mortality after stroke, noted that “physical activity has innumerable benefits, and it’s important that people engage in activity that can be regular and consistent, regardless of the type or intensity.”

To this end, he highlighted the use of “devices capable of monitoring step count, which can be an important motivational tool,” and suggested that these findings may bring a sigh of relief to step counters who come up a little short on a common daily goal.

“A target of 10,000 steps is often used for public health promotion, and this study now provides convincing observational evidence that it may be an optimal step count target for mortality reduction,” Dr. Joundi said. “However, if 10,000 steps per day is not feasible, 7,000 steps seems to be a very reasonable target given its association with markedly lower mortality in this study.”

Not all step counters are equal

Unfortunately, such recommendations are complicated by uncertainty in measurement, as widely used step counting devices, like smart watches, may not yield the same results as research-grade accelerometers, according to Nicole L. Spartano, PhD, of Boston University.

“Many comparison studies have been conducted in laboratory settings among young healthy adults, but these do not necessarily reflect real-life wear experiences that will be generalizable to the population as a whole,” Dr. Spartano wrote in an accompanying editorial.

She called for large-scale comparison studies to compare research-grade and consumer devices.

“The reason for conducting comparison studies is not to develop distinct guidelines for different devices or subgroups of the population, but rather to understand the variability so that we can develop one clear message that is most appropriate to the public,” Dr. Spartano wrote. “Some devices may have bias in terms of step measurement at different activity intensity and may not record steps as accurately in older adults or individuals with obesity or mobility disorders. For example, when adults who were obese wore an ActiGraph monitor in a laboratory setting, the device only recorded 80% of steps walked at a moderate pace, while other devices recorded close to 100% of steps walked. If we in the public health community are to move toward using these devices more for physical activity prescription, these details will need to be explored in more depth.”

CARDIA was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Northwestern University, the University of Minnesota, and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Some study authors received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Dr Spartano disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk, the American Heart Association, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Joundi and Dr. Paluch disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

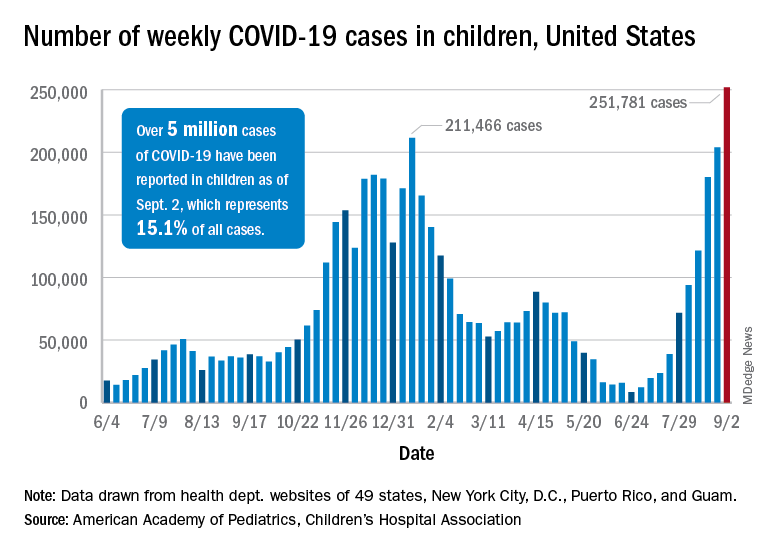

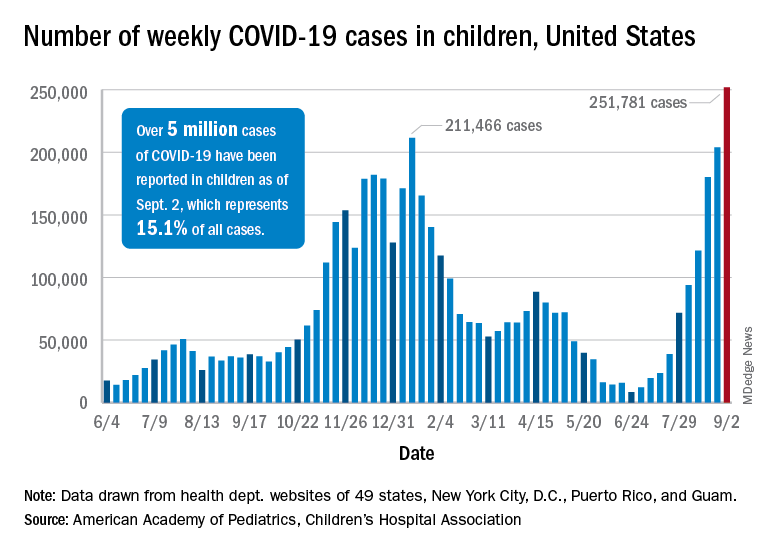

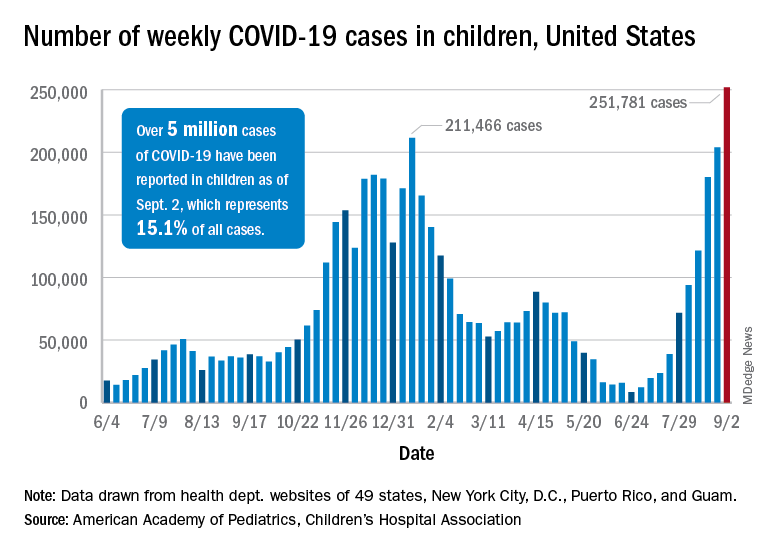

United States reaches 5 million cases of child COVID

Cases of child COVID-19 set a new 1-week record and the total number of children infected during the pandemic passed 5 million, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The nearly 282,000 new cases reported in the United States during the week ending Sept. 2 broke the record of 211,000 set in mid-January and brought the cumulative count to 5,049,465 children with COVID-19 since the pandemic began, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Hospitalizations in children aged 0-17 years have also reached record levels in recent days. The highest daily admission rate since the pandemic began, 0.51 per 100,000 population, was recorded on Sept. 2, less than 2 months after the nation saw its lowest child COVID admission rate for 1 day: 0.07 per 100,000 on July 4. That’s an increase of 629%, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccinations in children, however, did not follow suit. New vaccinations in children aged 12-17 years dropped by 4.5% for the week ending Sept. 6, compared with the week before. Initiations were actually up almost 12% for children aged 16-17, but that was not enough to overcome the continued decline among 12- to 15-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.