User login

Nodular Sclerosing Hodgkin Lymphoma With Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration

Paraneoplastic syndrome is a rare disorder involving manifestations of immune dysregulation triggered by malignancy. The immune system develops antibodies to the malignancy, which can cause cross reactivation with various tissues in the body, resulting in an autoimmune response. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is a rare condition caused by immune-mediated damage to the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar tract. Symptoms may include gait instability, double vision, decreased fine motor skills, and ataxia, with progression to brainstem-associated symptoms, such as nystagmus, dysarthria, and dysphagia. Early detection and treatment of the underlying malignancy is critical to halt the progression of autoimmune-mediated destruction. We present a case of a young adult female patient with PCD caused by Purkinje cell cytoplasmic–Tr (PCA-Tr) antibody with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Case Presentation

A 20-year-old previously healthy active-duty female patient presented to the emergency department with acute worsening of chronic intermittent, recurrent episodes of lightheadedness and vertigo. Symptoms persisted for 9 months until acutely worsening over the 2 weeks prior to presentation. She reported left eye double vision but did not report seeing spots, photophobia, tinnitus, or headache. She felt off-balance, leaning on nearby objects to remain standing. Symptoms primarily occurred during ambulation; however, occasionally they happened at rest. Episodes lasted up to several minutes and occurred up to 15 times a day. The patient reported no fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss, muscle aches, weakness, numbness or tingling, loss of bowel or bladder function, or rash. She had no recent illnesses, changes to medications, or recent travel. Oral intake to include food and water was adequate and unchanged. The patient had a remote history of mild concussions without loss of consciousness while playing sports 4 years previously. She reported no recent trauma. Nine months before, she received treatment for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) with the Epley maneuver with full resolution of symptoms lasting several days. She reported no prescription or over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, or supplements. She reported no other medical or surgical history and no pertinent social or family history.

Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing female patient with intermittent conversational dysarthria, saccadic pursuits, horizontal nystagmus with lateral gaze, and vertical nystagmus with vertical gaze. The patient exhibited dysdiadochokinesia, or impaired ability to perform rapid alternating hand movements with repetition. Finger-to-nose testing was impaired and heel-to-shin motion remained intact. A Romberg test was positive, and the patient had tandem gait instability. Strength testing, sensation, reflexes, and cranial nerves were otherwise intact. Initial laboratory testing was unremarkable except for mild normocytic anemia. Her infectious workup, including testing for venereal disease, HIV, COVID-19, and Coccidioidies was negative. Heavy metals analysis and urine drug screen were negative. Ophthalmology was consulted and workup revealed small amplitude downbeat nystagmus in primary gaze, sustained gaze evoked lateral beating jerk nystagmus with rebound nystagmus R>L gaze, but there was no evidence of afferent package defect and optic nerve function remained intact. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated cerebellar vermis hypoplasia with prominence of the superior cerebellar folia. Due to concerns for autoimmune encephalitis, a lumbar puncture was performed. Antibody testing revealed PCA-Tr antibodies, which is commonly associated with Hodgkin lymphoma, prompting further evaluation for malignancy.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast demonstrated multiple mediastinal masses with a conglomeration of lymph nodes along the right paratracheal region. Further evaluation was performed with a positron emission tomography (PET)–CT, revealing a large conglomeration of hypermetabolic pretracheal, mediastinal, and right supraclavicular lymph that were suggestive of lymphoma. Mediastinoscopy with excisional lymph node biopsy was performed with immunohistochemical staining confirming diagnosis of a nodular sclerosing variant of Hodgkin lymphoma. The patient was treated with IV immunoglobulin at 0.4g/kg daily for 5 days. A central venous catheter was placed into the patient’s right internal jugular vein and a chemotherapy regimen of doxorubicin 46 mg, vinblastine 11 mg, bleomycin 19 units, and dacarbazine 700 mg was initiated. The patient’s symptoms improved with resolution of dysarthria; however, her visual impairment and gait instability persisted. Repeat PET-CT imaging 2 months later revealed interval improvement with decreased intensity and extent of the hypermetabolic lymph nodes and no new hypermetabolic foci.

Discussion

PCA-Tr antibodies affect the delta/notchlike epidermal growth factor–related receptor, expressed on the dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje cells.1 These fibers are the only output neurons of the cerebellar cortex and are critical to the coordination of motor movements, accounting for the ataxia experienced by patients with this subtype of PCD.2 The link between Hodgkin lymphoma and PCA-Tr antibodies has been established; however, most reports involve men with a median age of 61 years with lymphoma-associated symptoms (such as lymphadenopathy) or systemic symptoms (fever, night sweats, or weight loss) preceding neurologic manifestations in 80% of cases.3

Our patient was a young, previously healthy adult female who initially presented with vertigo, a common concern with frequently benign origins. Although there was temporary resolution of symptoms after Epley maneuvers, symptoms recurred and progressed over several months to include brainstem manifestations of nystagmus, diplopia, and dysarthria. Previous reports indicate that after remission of the Hodgkin lymphoma, PCA-Tr antibodies disappear and symptoms can improve or resolve.4,5 Treatment has just begun for our patient and although there has been initial clinical improvement, given the chronicity of symptoms, it is unclear if complete resolution will be achieved.

Conclusions

PCD can result in debilitating neurologic dysfunction and may be associated with malignancy such as Hodgkin lymphoma. This case offers unique insight due to the patient’s demographics and presentation, which involved brainstem pathology typically associated with late-onset disease and preceded by constitutional symptoms. Clinical suspicion of this rare disorder should be considered in all ages, especially if symptoms are progressive or neurologic manifestations arise, as early detection and treatment of the underlying malignancy are paramount to the prevention of significant disability.

1. de Graaff E, Maat P, Hulsenboom E, et al. Identification of delta/notch-like epidermal growth factor-related receptor as the Tr antigen in paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):815-824. doi:10.1002/ana.23550

2. MacKenzie-Graham A, Tiwari-Woodruff SK, Sharma G, et al. Purkinje cell loss in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neuroimage. 2009;48(4):637-651. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.073

3. Bernal F, Shams’ili S, Rojas I, et al. Anti-Tr antibodies as markers of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration and Hodgkin’s disease. Neurology. 2003;60(2):230-234. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000041495.87539.98

4. Graus F, Ariño H, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 2014;123(21):3230-3238. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-03-537506

5. Aly R, Emmady PD. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Updated May 8, 2022. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560638

Paraneoplastic syndrome is a rare disorder involving manifestations of immune dysregulation triggered by malignancy. The immune system develops antibodies to the malignancy, which can cause cross reactivation with various tissues in the body, resulting in an autoimmune response. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is a rare condition caused by immune-mediated damage to the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar tract. Symptoms may include gait instability, double vision, decreased fine motor skills, and ataxia, with progression to brainstem-associated symptoms, such as nystagmus, dysarthria, and dysphagia. Early detection and treatment of the underlying malignancy is critical to halt the progression of autoimmune-mediated destruction. We present a case of a young adult female patient with PCD caused by Purkinje cell cytoplasmic–Tr (PCA-Tr) antibody with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Case Presentation

A 20-year-old previously healthy active-duty female patient presented to the emergency department with acute worsening of chronic intermittent, recurrent episodes of lightheadedness and vertigo. Symptoms persisted for 9 months until acutely worsening over the 2 weeks prior to presentation. She reported left eye double vision but did not report seeing spots, photophobia, tinnitus, or headache. She felt off-balance, leaning on nearby objects to remain standing. Symptoms primarily occurred during ambulation; however, occasionally they happened at rest. Episodes lasted up to several minutes and occurred up to 15 times a day. The patient reported no fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss, muscle aches, weakness, numbness or tingling, loss of bowel or bladder function, or rash. She had no recent illnesses, changes to medications, or recent travel. Oral intake to include food and water was adequate and unchanged. The patient had a remote history of mild concussions without loss of consciousness while playing sports 4 years previously. She reported no recent trauma. Nine months before, she received treatment for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) with the Epley maneuver with full resolution of symptoms lasting several days. She reported no prescription or over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, or supplements. She reported no other medical or surgical history and no pertinent social or family history.

Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing female patient with intermittent conversational dysarthria, saccadic pursuits, horizontal nystagmus with lateral gaze, and vertical nystagmus with vertical gaze. The patient exhibited dysdiadochokinesia, or impaired ability to perform rapid alternating hand movements with repetition. Finger-to-nose testing was impaired and heel-to-shin motion remained intact. A Romberg test was positive, and the patient had tandem gait instability. Strength testing, sensation, reflexes, and cranial nerves were otherwise intact. Initial laboratory testing was unremarkable except for mild normocytic anemia. Her infectious workup, including testing for venereal disease, HIV, COVID-19, and Coccidioidies was negative. Heavy metals analysis and urine drug screen were negative. Ophthalmology was consulted and workup revealed small amplitude downbeat nystagmus in primary gaze, sustained gaze evoked lateral beating jerk nystagmus with rebound nystagmus R>L gaze, but there was no evidence of afferent package defect and optic nerve function remained intact. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated cerebellar vermis hypoplasia with prominence of the superior cerebellar folia. Due to concerns for autoimmune encephalitis, a lumbar puncture was performed. Antibody testing revealed PCA-Tr antibodies, which is commonly associated with Hodgkin lymphoma, prompting further evaluation for malignancy.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast demonstrated multiple mediastinal masses with a conglomeration of lymph nodes along the right paratracheal region. Further evaluation was performed with a positron emission tomography (PET)–CT, revealing a large conglomeration of hypermetabolic pretracheal, mediastinal, and right supraclavicular lymph that were suggestive of lymphoma. Mediastinoscopy with excisional lymph node biopsy was performed with immunohistochemical staining confirming diagnosis of a nodular sclerosing variant of Hodgkin lymphoma. The patient was treated with IV immunoglobulin at 0.4g/kg daily for 5 days. A central venous catheter was placed into the patient’s right internal jugular vein and a chemotherapy regimen of doxorubicin 46 mg, vinblastine 11 mg, bleomycin 19 units, and dacarbazine 700 mg was initiated. The patient’s symptoms improved with resolution of dysarthria; however, her visual impairment and gait instability persisted. Repeat PET-CT imaging 2 months later revealed interval improvement with decreased intensity and extent of the hypermetabolic lymph nodes and no new hypermetabolic foci.

Discussion

PCA-Tr antibodies affect the delta/notchlike epidermal growth factor–related receptor, expressed on the dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje cells.1 These fibers are the only output neurons of the cerebellar cortex and are critical to the coordination of motor movements, accounting for the ataxia experienced by patients with this subtype of PCD.2 The link between Hodgkin lymphoma and PCA-Tr antibodies has been established; however, most reports involve men with a median age of 61 years with lymphoma-associated symptoms (such as lymphadenopathy) or systemic symptoms (fever, night sweats, or weight loss) preceding neurologic manifestations in 80% of cases.3

Our patient was a young, previously healthy adult female who initially presented with vertigo, a common concern with frequently benign origins. Although there was temporary resolution of symptoms after Epley maneuvers, symptoms recurred and progressed over several months to include brainstem manifestations of nystagmus, diplopia, and dysarthria. Previous reports indicate that after remission of the Hodgkin lymphoma, PCA-Tr antibodies disappear and symptoms can improve or resolve.4,5 Treatment has just begun for our patient and although there has been initial clinical improvement, given the chronicity of symptoms, it is unclear if complete resolution will be achieved.

Conclusions

PCD can result in debilitating neurologic dysfunction and may be associated with malignancy such as Hodgkin lymphoma. This case offers unique insight due to the patient’s demographics and presentation, which involved brainstem pathology typically associated with late-onset disease and preceded by constitutional symptoms. Clinical suspicion of this rare disorder should be considered in all ages, especially if symptoms are progressive or neurologic manifestations arise, as early detection and treatment of the underlying malignancy are paramount to the prevention of significant disability.

Paraneoplastic syndrome is a rare disorder involving manifestations of immune dysregulation triggered by malignancy. The immune system develops antibodies to the malignancy, which can cause cross reactivation with various tissues in the body, resulting in an autoimmune response. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is a rare condition caused by immune-mediated damage to the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar tract. Symptoms may include gait instability, double vision, decreased fine motor skills, and ataxia, with progression to brainstem-associated symptoms, such as nystagmus, dysarthria, and dysphagia. Early detection and treatment of the underlying malignancy is critical to halt the progression of autoimmune-mediated destruction. We present a case of a young adult female patient with PCD caused by Purkinje cell cytoplasmic–Tr (PCA-Tr) antibody with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Case Presentation

A 20-year-old previously healthy active-duty female patient presented to the emergency department with acute worsening of chronic intermittent, recurrent episodes of lightheadedness and vertigo. Symptoms persisted for 9 months until acutely worsening over the 2 weeks prior to presentation. She reported left eye double vision but did not report seeing spots, photophobia, tinnitus, or headache. She felt off-balance, leaning on nearby objects to remain standing. Symptoms primarily occurred during ambulation; however, occasionally they happened at rest. Episodes lasted up to several minutes and occurred up to 15 times a day. The patient reported no fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss, muscle aches, weakness, numbness or tingling, loss of bowel or bladder function, or rash. She had no recent illnesses, changes to medications, or recent travel. Oral intake to include food and water was adequate and unchanged. The patient had a remote history of mild concussions without loss of consciousness while playing sports 4 years previously. She reported no recent trauma. Nine months before, she received treatment for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) with the Epley maneuver with full resolution of symptoms lasting several days. She reported no prescription or over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, or supplements. She reported no other medical or surgical history and no pertinent social or family history.

Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing female patient with intermittent conversational dysarthria, saccadic pursuits, horizontal nystagmus with lateral gaze, and vertical nystagmus with vertical gaze. The patient exhibited dysdiadochokinesia, or impaired ability to perform rapid alternating hand movements with repetition. Finger-to-nose testing was impaired and heel-to-shin motion remained intact. A Romberg test was positive, and the patient had tandem gait instability. Strength testing, sensation, reflexes, and cranial nerves were otherwise intact. Initial laboratory testing was unremarkable except for mild normocytic anemia. Her infectious workup, including testing for venereal disease, HIV, COVID-19, and Coccidioidies was negative. Heavy metals analysis and urine drug screen were negative. Ophthalmology was consulted and workup revealed small amplitude downbeat nystagmus in primary gaze, sustained gaze evoked lateral beating jerk nystagmus with rebound nystagmus R>L gaze, but there was no evidence of afferent package defect and optic nerve function remained intact. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated cerebellar vermis hypoplasia with prominence of the superior cerebellar folia. Due to concerns for autoimmune encephalitis, a lumbar puncture was performed. Antibody testing revealed PCA-Tr antibodies, which is commonly associated with Hodgkin lymphoma, prompting further evaluation for malignancy.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast demonstrated multiple mediastinal masses with a conglomeration of lymph nodes along the right paratracheal region. Further evaluation was performed with a positron emission tomography (PET)–CT, revealing a large conglomeration of hypermetabolic pretracheal, mediastinal, and right supraclavicular lymph that were suggestive of lymphoma. Mediastinoscopy with excisional lymph node biopsy was performed with immunohistochemical staining confirming diagnosis of a nodular sclerosing variant of Hodgkin lymphoma. The patient was treated with IV immunoglobulin at 0.4g/kg daily for 5 days. A central venous catheter was placed into the patient’s right internal jugular vein and a chemotherapy regimen of doxorubicin 46 mg, vinblastine 11 mg, bleomycin 19 units, and dacarbazine 700 mg was initiated. The patient’s symptoms improved with resolution of dysarthria; however, her visual impairment and gait instability persisted. Repeat PET-CT imaging 2 months later revealed interval improvement with decreased intensity and extent of the hypermetabolic lymph nodes and no new hypermetabolic foci.

Discussion

PCA-Tr antibodies affect the delta/notchlike epidermal growth factor–related receptor, expressed on the dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje cells.1 These fibers are the only output neurons of the cerebellar cortex and are critical to the coordination of motor movements, accounting for the ataxia experienced by patients with this subtype of PCD.2 The link between Hodgkin lymphoma and PCA-Tr antibodies has been established; however, most reports involve men with a median age of 61 years with lymphoma-associated symptoms (such as lymphadenopathy) or systemic symptoms (fever, night sweats, or weight loss) preceding neurologic manifestations in 80% of cases.3

Our patient was a young, previously healthy adult female who initially presented with vertigo, a common concern with frequently benign origins. Although there was temporary resolution of symptoms after Epley maneuvers, symptoms recurred and progressed over several months to include brainstem manifestations of nystagmus, diplopia, and dysarthria. Previous reports indicate that after remission of the Hodgkin lymphoma, PCA-Tr antibodies disappear and symptoms can improve or resolve.4,5 Treatment has just begun for our patient and although there has been initial clinical improvement, given the chronicity of symptoms, it is unclear if complete resolution will be achieved.

Conclusions

PCD can result in debilitating neurologic dysfunction and may be associated with malignancy such as Hodgkin lymphoma. This case offers unique insight due to the patient’s demographics and presentation, which involved brainstem pathology typically associated with late-onset disease and preceded by constitutional symptoms. Clinical suspicion of this rare disorder should be considered in all ages, especially if symptoms are progressive or neurologic manifestations arise, as early detection and treatment of the underlying malignancy are paramount to the prevention of significant disability.

1. de Graaff E, Maat P, Hulsenboom E, et al. Identification of delta/notch-like epidermal growth factor-related receptor as the Tr antigen in paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):815-824. doi:10.1002/ana.23550

2. MacKenzie-Graham A, Tiwari-Woodruff SK, Sharma G, et al. Purkinje cell loss in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neuroimage. 2009;48(4):637-651. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.073

3. Bernal F, Shams’ili S, Rojas I, et al. Anti-Tr antibodies as markers of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration and Hodgkin’s disease. Neurology. 2003;60(2):230-234. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000041495.87539.98

4. Graus F, Ariño H, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 2014;123(21):3230-3238. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-03-537506

5. Aly R, Emmady PD. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Updated May 8, 2022. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560638

1. de Graaff E, Maat P, Hulsenboom E, et al. Identification of delta/notch-like epidermal growth factor-related receptor as the Tr antigen in paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):815-824. doi:10.1002/ana.23550

2. MacKenzie-Graham A, Tiwari-Woodruff SK, Sharma G, et al. Purkinje cell loss in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neuroimage. 2009;48(4):637-651. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.073

3. Bernal F, Shams’ili S, Rojas I, et al. Anti-Tr antibodies as markers of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration and Hodgkin’s disease. Neurology. 2003;60(2):230-234. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000041495.87539.98

4. Graus F, Ariño H, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 2014;123(21):3230-3238. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-03-537506

5. Aly R, Emmady PD. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Updated May 8, 2022. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560638

Cancer drug significantly cuts risk for COVID-19 death

, an interim analysis of a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial found.

Sabizabulin treatment consistently and significantly reduced deaths across patient subgroups “regardless of standard of care treatment received, baseline World Health Organization scores, age, comorbidities, vaccination status, COVID-19 variant, or geography,” study investigator Mitchell Steiner, MD, chairman, president, and CEO of Veru, said in a news release.

The company has submitted an emergency use authorization request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to use sabizabulin to treat COVID-19.

The analysis was published online in NEJM Evidence.

Sabizabulin, originally developed to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, is a novel, investigational, oral microtubule disruptor with dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities. Given the drug’s mechanism, researchers at Veru thought that sabizabulin could help treat lung inflammation in patients with COVID-19 as well.

Findings of the interim analysis are based on 150 adults hospitalized with moderate to severe COVID-19 at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome and death. The patients were randomly allocated to receive 9 mg oral sabizabulin (n = 98) or placebo (n = 52) once daily for up to 21 days.

Overall, the mortality rate was 20.2% in the sabizabulin group vs. 45.1% in the placebo group. Compared with placebo, treatment with sabizabulin led to a 24.9–percentage point absolute reduction and a 55.2% relative reduction in death (odds ratio, 3.23; P = .0042).

The key secondary endpoint of mortality through day 29 also favored sabizabulin over placebo, with a mortality rate of 17% vs. 35.3%. In this scenario, treatment with sabizabulin resulted in an absolute reduction in deaths of 18.3 percentage points and a relative reduction of 51.8%.

Sabizabulin led to a significant 43% relative reduction in ICU days, a 49% relative reduction in days on mechanical ventilation, and a 26% relative reduction in days in the hospital, compared with placebo.

Adverse and serious adverse events were also lower in the sabizabulin group (61.5%) than the placebo group (78.3%).

The data are “pretty impressive and in a group of patients that we really have limited things to offer,” Aaron Glatt, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, N.Y., said in an interview. “This is an interim analysis and obviously we’d like to see more data, but it certainly is something that is novel and quite interesting.”

David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease expert at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times that the large number of deaths in the placebo group seemed “rather high” and that the final analysis might reveal a more modest benefit for sabizabulin.

“I would be skeptical” that the reduced risk for death remains 55%, he noted.

The study was funded by Veru Pharmaceuticals. Several authors are employed by the company or have financial relationships with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, an interim analysis of a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial found.

Sabizabulin treatment consistently and significantly reduced deaths across patient subgroups “regardless of standard of care treatment received, baseline World Health Organization scores, age, comorbidities, vaccination status, COVID-19 variant, or geography,” study investigator Mitchell Steiner, MD, chairman, president, and CEO of Veru, said in a news release.

The company has submitted an emergency use authorization request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to use sabizabulin to treat COVID-19.

The analysis was published online in NEJM Evidence.

Sabizabulin, originally developed to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, is a novel, investigational, oral microtubule disruptor with dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities. Given the drug’s mechanism, researchers at Veru thought that sabizabulin could help treat lung inflammation in patients with COVID-19 as well.

Findings of the interim analysis are based on 150 adults hospitalized with moderate to severe COVID-19 at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome and death. The patients were randomly allocated to receive 9 mg oral sabizabulin (n = 98) or placebo (n = 52) once daily for up to 21 days.

Overall, the mortality rate was 20.2% in the sabizabulin group vs. 45.1% in the placebo group. Compared with placebo, treatment with sabizabulin led to a 24.9–percentage point absolute reduction and a 55.2% relative reduction in death (odds ratio, 3.23; P = .0042).

The key secondary endpoint of mortality through day 29 also favored sabizabulin over placebo, with a mortality rate of 17% vs. 35.3%. In this scenario, treatment with sabizabulin resulted in an absolute reduction in deaths of 18.3 percentage points and a relative reduction of 51.8%.

Sabizabulin led to a significant 43% relative reduction in ICU days, a 49% relative reduction in days on mechanical ventilation, and a 26% relative reduction in days in the hospital, compared with placebo.

Adverse and serious adverse events were also lower in the sabizabulin group (61.5%) than the placebo group (78.3%).

The data are “pretty impressive and in a group of patients that we really have limited things to offer,” Aaron Glatt, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, N.Y., said in an interview. “This is an interim analysis and obviously we’d like to see more data, but it certainly is something that is novel and quite interesting.”

David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease expert at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times that the large number of deaths in the placebo group seemed “rather high” and that the final analysis might reveal a more modest benefit for sabizabulin.

“I would be skeptical” that the reduced risk for death remains 55%, he noted.

The study was funded by Veru Pharmaceuticals. Several authors are employed by the company or have financial relationships with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, an interim analysis of a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial found.

Sabizabulin treatment consistently and significantly reduced deaths across patient subgroups “regardless of standard of care treatment received, baseline World Health Organization scores, age, comorbidities, vaccination status, COVID-19 variant, or geography,” study investigator Mitchell Steiner, MD, chairman, president, and CEO of Veru, said in a news release.

The company has submitted an emergency use authorization request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to use sabizabulin to treat COVID-19.

The analysis was published online in NEJM Evidence.

Sabizabulin, originally developed to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, is a novel, investigational, oral microtubule disruptor with dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities. Given the drug’s mechanism, researchers at Veru thought that sabizabulin could help treat lung inflammation in patients with COVID-19 as well.

Findings of the interim analysis are based on 150 adults hospitalized with moderate to severe COVID-19 at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome and death. The patients were randomly allocated to receive 9 mg oral sabizabulin (n = 98) or placebo (n = 52) once daily for up to 21 days.

Overall, the mortality rate was 20.2% in the sabizabulin group vs. 45.1% in the placebo group. Compared with placebo, treatment with sabizabulin led to a 24.9–percentage point absolute reduction and a 55.2% relative reduction in death (odds ratio, 3.23; P = .0042).

The key secondary endpoint of mortality through day 29 also favored sabizabulin over placebo, with a mortality rate of 17% vs. 35.3%. In this scenario, treatment with sabizabulin resulted in an absolute reduction in deaths of 18.3 percentage points and a relative reduction of 51.8%.

Sabizabulin led to a significant 43% relative reduction in ICU days, a 49% relative reduction in days on mechanical ventilation, and a 26% relative reduction in days in the hospital, compared with placebo.

Adverse and serious adverse events were also lower in the sabizabulin group (61.5%) than the placebo group (78.3%).

The data are “pretty impressive and in a group of patients that we really have limited things to offer,” Aaron Glatt, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, N.Y., said in an interview. “This is an interim analysis and obviously we’d like to see more data, but it certainly is something that is novel and quite interesting.”

David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease expert at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times that the large number of deaths in the placebo group seemed “rather high” and that the final analysis might reveal a more modest benefit for sabizabulin.

“I would be skeptical” that the reduced risk for death remains 55%, he noted.

The study was funded by Veru Pharmaceuticals. Several authors are employed by the company or have financial relationships with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEJM EVIDENCE

Select patients with breast cancer may skip RT after lumpectomy

The women in this trial who skipped radiotherapy, and were treated with breast-conserving surgery followed by endocrine therapy, had an overall survival rate of 97.2%. The local recurrence rate was 2.3%, which was the study’s primary endpoint.

“Women 55 and over, with low-grade luminal A-type breast cancer, following breast conserving surgery and treated with endocrine therapy alone, had a very low rate of local recurrence at 5 years,” commented lead author Timothy Joseph Whelan, MD.

“The prospective and multicenter nature of this study supports that these patients are candidates for the omission of radiotherapy,” said Dr. Whelan, oncology professor and Canada Research Chair in Breast Cancer Research at McMaster University and a radiation oncologist at the Juravinski Cancer Centre, both in Hamilton, Ont.

“Over 300,000 [people] are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in North America annually, the majority in the United States,” said Dr. Whelan. “We estimate that these results could apply to 10%-15% of them, so about 30,000-40,000 women per year who could avoid the morbidity, the cost, and inconvenience of radiotherapy.”

The results were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Dr. Whelan explained that adjuvant radiation therapy is generally prescribed following breast conservation therapy to lower the risk of local recurrence, but the treatment is also associated with acute and late toxicity. In addition, it can incur high costs and inconvenience for the patient.

Previous studies have found that among women older than 60 with low-grade, luminal A-type breast cancer who received only breast-conserving surgery, there was a low rate of local recurrence. In women aged older than 70 years, the risk of local recurrence was about 4%-5%.

This latest study focused on patients with breast cancer with a luminal A subtype combined with clinical pathological factors (defined as estrogen receptor ≥ 1%, progesterone receptor > 20%, HER2 negative, and Ki67 ≤ 13.25%).

This was a prospective, multicenter cohort study that included 501 patients aged 55 years and older who had undergone breast-conserving surgery for grade 1-2 T1N0 cancer.

The median patient age was 67, with 442 (88%) older than 75 years. The median tumor size was 1.1 cm.

Median follow-up was 5 years. The cohort was followed every 6 months for the first 2 years and then annually.

The primary outcome was local recurrence defined as time from enrollment to any invasive or noninvasive cancer in the ipsilateral breast, and secondary endpoints included contralateral breast cancer, relapse-free survival based on any recurrence, disease free survival, second cancer or death, and overall survival.

At five years, there were 10 events of local recurrence, for a rate of 2.3%. For secondary outcomes, there were eight events of contralateral breast cancer (1.9%); 12 relapses for a recurrence-free survival rate of 97.3%; 47 disease progression (23 second nonbreast cancers) for a disease-free survival rate of 89.9%; and 13 deaths, including 1 from breast cancer, for an overall survival of 97.2%.

Confirms earlier data

Penny R. Anderson, MD, professor in the department of radiation oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, commented that this was an “extremely well-designed and important study.

“It has identified a specific subset of patients to be appropriate candidates for consideration of omission of adjuvant breast radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery,” she added.

Although previously published trials have helped identify certain patient groups who have a low risk of local recurrence – and therefore, for whom it may be appropriate to omit radiation – they have been based on the traditional clinical and pathologic factors of tumor size, margin status, receptor status, and patient age.

“This LUMINA trial utilizes the molecular-defined intrinsic subtype of luminal A breast cancer to provide additional prognostic information,” she said. “This finding certainly suggests that this group of patients are ideal candidates for the omission of radiation, and that this should be discussed with these patients as a potential option in their treatment management.”

Overall, this trial is a “significant addition and a very relevant contribution to the literature demonstrating that adjuvant breast radiation may safely be omitted in this particular subgroup of breast cancer patients,” she said.

Unanswered questions

Commenting on the study, Julie Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO, told this news organization that she thinks the take-home message is that there is “clearly a population of early-stage breast cancer [patients] who after lumpectomy do not benefit from radiation.”

“I think where there will be discussion will be what is the optimal way of identifying that group,” she said, noting that in this study the patients were screened for Ki67, a marker of proliferation.

Testing for Ki67 is not the standard of care, Dr. Gralow pointed out, and there is also a problem with reproducibility since “every lab does it somewhat differently, because it is not a standard pathology approach.”

There are now many unanswered questions, she noted. “Do we need that central testing of Ki67? Do we need to develop guidelines for how to do this? Is this better than if you’ve already run an Oncotype or a MammaPrint test to see if the patient needs chemo, then would that suffice? That is where the discussion will be. We can reduce the number of patients who need radiation without an increase in local regional recurrence.”

In terms of clinical practice, Dr. Gralow explained that there are already some data supporting the omission of radiation therapy in an older population with ER-positive small low-grade tumors, and this has become a standard clinical practice. “It’s not based on solid data, but based on an accumulation of retrospective analyses,” she said. “So we have already been doing it for an older population. This would bring down the age group, and it would better define it, and test it prospectively.”

Limitations to note

Also commenting on the study, Deborah Axelrod, MD, director of clinical breast surgery at New York University Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, explained that, in the last decade, knowledge about the behavior of breast cancers based on molecular subtyping has greatly increased. “Results of studies such as this have given us information on which cancers need more treatment and for which cancers we can de-escalate treatment,” she said. “Refining this more, it’s about reducing the morbidity and improving quality of life without compromising the oncological outcome.”

She noted that a big strength of this LUMINA study is that it is prospective and multicenter. “It has been supported by other past studies as well and will define for which patients with newly treated breast cancers can we omit radiation, which has been the standard of care,” said Dr. Axelrod. “It is based on the age and biology of breast cancer in defining which patient can forgo radiation and showed a low risk of recurrence in a specific population of women with a favorable breast cancer profile”

There were limitations to the study. “There is a 5-year follow-up and local recurrence for ER-positive cancers continues to rise after 5 years, so longer-term follow-up will be important,” she said. Also, she pointed out that it is a single-arm study so there is no radiation therapy comparison arm.

Other limitations were that the patients were older with smaller tumors, and all were committed to 5 years of endocrine therapy, although compliance with that has not been reported. There may be some older patients who prefer radiation therapy, especially a week of accelerated partial breast irradiation, rather than commit to 5 years of endocrine therapy as mandated in this study.

“Overall, the takeaway message for patients is that the omission of radiation therapy should be considered an option for older women with localized breast cancer with favorable features who receive endocrine therapies,” said Dr. Axelrod.

LUMINA was sponsored by the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation and the Canadian Cancer Society. Dr. Whelan has reported research funding from Exact Sciences (Inst). Dr. Axelrod and Dr. Anderson reported no disclosures. Dr. Gralow reported relationships with Genentech, AstraZeneca, Hexal, Puma BioTechnology, Roche, Novartis, Seagen, and Genomic Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The women in this trial who skipped radiotherapy, and were treated with breast-conserving surgery followed by endocrine therapy, had an overall survival rate of 97.2%. The local recurrence rate was 2.3%, which was the study’s primary endpoint.

“Women 55 and over, with low-grade luminal A-type breast cancer, following breast conserving surgery and treated with endocrine therapy alone, had a very low rate of local recurrence at 5 years,” commented lead author Timothy Joseph Whelan, MD.

“The prospective and multicenter nature of this study supports that these patients are candidates for the omission of radiotherapy,” said Dr. Whelan, oncology professor and Canada Research Chair in Breast Cancer Research at McMaster University and a radiation oncologist at the Juravinski Cancer Centre, both in Hamilton, Ont.

“Over 300,000 [people] are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in North America annually, the majority in the United States,” said Dr. Whelan. “We estimate that these results could apply to 10%-15% of them, so about 30,000-40,000 women per year who could avoid the morbidity, the cost, and inconvenience of radiotherapy.”

The results were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Dr. Whelan explained that adjuvant radiation therapy is generally prescribed following breast conservation therapy to lower the risk of local recurrence, but the treatment is also associated with acute and late toxicity. In addition, it can incur high costs and inconvenience for the patient.

Previous studies have found that among women older than 60 with low-grade, luminal A-type breast cancer who received only breast-conserving surgery, there was a low rate of local recurrence. In women aged older than 70 years, the risk of local recurrence was about 4%-5%.

This latest study focused on patients with breast cancer with a luminal A subtype combined with clinical pathological factors (defined as estrogen receptor ≥ 1%, progesterone receptor > 20%, HER2 negative, and Ki67 ≤ 13.25%).

This was a prospective, multicenter cohort study that included 501 patients aged 55 years and older who had undergone breast-conserving surgery for grade 1-2 T1N0 cancer.

The median patient age was 67, with 442 (88%) older than 75 years. The median tumor size was 1.1 cm.

Median follow-up was 5 years. The cohort was followed every 6 months for the first 2 years and then annually.

The primary outcome was local recurrence defined as time from enrollment to any invasive or noninvasive cancer in the ipsilateral breast, and secondary endpoints included contralateral breast cancer, relapse-free survival based on any recurrence, disease free survival, second cancer or death, and overall survival.

At five years, there were 10 events of local recurrence, for a rate of 2.3%. For secondary outcomes, there were eight events of contralateral breast cancer (1.9%); 12 relapses for a recurrence-free survival rate of 97.3%; 47 disease progression (23 second nonbreast cancers) for a disease-free survival rate of 89.9%; and 13 deaths, including 1 from breast cancer, for an overall survival of 97.2%.

Confirms earlier data

Penny R. Anderson, MD, professor in the department of radiation oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, commented that this was an “extremely well-designed and important study.

“It has identified a specific subset of patients to be appropriate candidates for consideration of omission of adjuvant breast radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery,” she added.

Although previously published trials have helped identify certain patient groups who have a low risk of local recurrence – and therefore, for whom it may be appropriate to omit radiation – they have been based on the traditional clinical and pathologic factors of tumor size, margin status, receptor status, and patient age.

“This LUMINA trial utilizes the molecular-defined intrinsic subtype of luminal A breast cancer to provide additional prognostic information,” she said. “This finding certainly suggests that this group of patients are ideal candidates for the omission of radiation, and that this should be discussed with these patients as a potential option in their treatment management.”

Overall, this trial is a “significant addition and a very relevant contribution to the literature demonstrating that adjuvant breast radiation may safely be omitted in this particular subgroup of breast cancer patients,” she said.

Unanswered questions

Commenting on the study, Julie Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO, told this news organization that she thinks the take-home message is that there is “clearly a population of early-stage breast cancer [patients] who after lumpectomy do not benefit from radiation.”

“I think where there will be discussion will be what is the optimal way of identifying that group,” she said, noting that in this study the patients were screened for Ki67, a marker of proliferation.

Testing for Ki67 is not the standard of care, Dr. Gralow pointed out, and there is also a problem with reproducibility since “every lab does it somewhat differently, because it is not a standard pathology approach.”

There are now many unanswered questions, she noted. “Do we need that central testing of Ki67? Do we need to develop guidelines for how to do this? Is this better than if you’ve already run an Oncotype or a MammaPrint test to see if the patient needs chemo, then would that suffice? That is where the discussion will be. We can reduce the number of patients who need radiation without an increase in local regional recurrence.”

In terms of clinical practice, Dr. Gralow explained that there are already some data supporting the omission of radiation therapy in an older population with ER-positive small low-grade tumors, and this has become a standard clinical practice. “It’s not based on solid data, but based on an accumulation of retrospective analyses,” she said. “So we have already been doing it for an older population. This would bring down the age group, and it would better define it, and test it prospectively.”

Limitations to note

Also commenting on the study, Deborah Axelrod, MD, director of clinical breast surgery at New York University Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, explained that, in the last decade, knowledge about the behavior of breast cancers based on molecular subtyping has greatly increased. “Results of studies such as this have given us information on which cancers need more treatment and for which cancers we can de-escalate treatment,” she said. “Refining this more, it’s about reducing the morbidity and improving quality of life without compromising the oncological outcome.”

She noted that a big strength of this LUMINA study is that it is prospective and multicenter. “It has been supported by other past studies as well and will define for which patients with newly treated breast cancers can we omit radiation, which has been the standard of care,” said Dr. Axelrod. “It is based on the age and biology of breast cancer in defining which patient can forgo radiation and showed a low risk of recurrence in a specific population of women with a favorable breast cancer profile”

There were limitations to the study. “There is a 5-year follow-up and local recurrence for ER-positive cancers continues to rise after 5 years, so longer-term follow-up will be important,” she said. Also, she pointed out that it is a single-arm study so there is no radiation therapy comparison arm.

Other limitations were that the patients were older with smaller tumors, and all were committed to 5 years of endocrine therapy, although compliance with that has not been reported. There may be some older patients who prefer radiation therapy, especially a week of accelerated partial breast irradiation, rather than commit to 5 years of endocrine therapy as mandated in this study.

“Overall, the takeaway message for patients is that the omission of radiation therapy should be considered an option for older women with localized breast cancer with favorable features who receive endocrine therapies,” said Dr. Axelrod.

LUMINA was sponsored by the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation and the Canadian Cancer Society. Dr. Whelan has reported research funding from Exact Sciences (Inst). Dr. Axelrod and Dr. Anderson reported no disclosures. Dr. Gralow reported relationships with Genentech, AstraZeneca, Hexal, Puma BioTechnology, Roche, Novartis, Seagen, and Genomic Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The women in this trial who skipped radiotherapy, and were treated with breast-conserving surgery followed by endocrine therapy, had an overall survival rate of 97.2%. The local recurrence rate was 2.3%, which was the study’s primary endpoint.

“Women 55 and over, with low-grade luminal A-type breast cancer, following breast conserving surgery and treated with endocrine therapy alone, had a very low rate of local recurrence at 5 years,” commented lead author Timothy Joseph Whelan, MD.

“The prospective and multicenter nature of this study supports that these patients are candidates for the omission of radiotherapy,” said Dr. Whelan, oncology professor and Canada Research Chair in Breast Cancer Research at McMaster University and a radiation oncologist at the Juravinski Cancer Centre, both in Hamilton, Ont.

“Over 300,000 [people] are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in North America annually, the majority in the United States,” said Dr. Whelan. “We estimate that these results could apply to 10%-15% of them, so about 30,000-40,000 women per year who could avoid the morbidity, the cost, and inconvenience of radiotherapy.”

The results were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Dr. Whelan explained that adjuvant radiation therapy is generally prescribed following breast conservation therapy to lower the risk of local recurrence, but the treatment is also associated with acute and late toxicity. In addition, it can incur high costs and inconvenience for the patient.

Previous studies have found that among women older than 60 with low-grade, luminal A-type breast cancer who received only breast-conserving surgery, there was a low rate of local recurrence. In women aged older than 70 years, the risk of local recurrence was about 4%-5%.

This latest study focused on patients with breast cancer with a luminal A subtype combined with clinical pathological factors (defined as estrogen receptor ≥ 1%, progesterone receptor > 20%, HER2 negative, and Ki67 ≤ 13.25%).

This was a prospective, multicenter cohort study that included 501 patients aged 55 years and older who had undergone breast-conserving surgery for grade 1-2 T1N0 cancer.

The median patient age was 67, with 442 (88%) older than 75 years. The median tumor size was 1.1 cm.

Median follow-up was 5 years. The cohort was followed every 6 months for the first 2 years and then annually.

The primary outcome was local recurrence defined as time from enrollment to any invasive or noninvasive cancer in the ipsilateral breast, and secondary endpoints included contralateral breast cancer, relapse-free survival based on any recurrence, disease free survival, second cancer or death, and overall survival.

At five years, there were 10 events of local recurrence, for a rate of 2.3%. For secondary outcomes, there were eight events of contralateral breast cancer (1.9%); 12 relapses for a recurrence-free survival rate of 97.3%; 47 disease progression (23 second nonbreast cancers) for a disease-free survival rate of 89.9%; and 13 deaths, including 1 from breast cancer, for an overall survival of 97.2%.

Confirms earlier data

Penny R. Anderson, MD, professor in the department of radiation oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, commented that this was an “extremely well-designed and important study.

“It has identified a specific subset of patients to be appropriate candidates for consideration of omission of adjuvant breast radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery,” she added.

Although previously published trials have helped identify certain patient groups who have a low risk of local recurrence – and therefore, for whom it may be appropriate to omit radiation – they have been based on the traditional clinical and pathologic factors of tumor size, margin status, receptor status, and patient age.

“This LUMINA trial utilizes the molecular-defined intrinsic subtype of luminal A breast cancer to provide additional prognostic information,” she said. “This finding certainly suggests that this group of patients are ideal candidates for the omission of radiation, and that this should be discussed with these patients as a potential option in their treatment management.”

Overall, this trial is a “significant addition and a very relevant contribution to the literature demonstrating that adjuvant breast radiation may safely be omitted in this particular subgroup of breast cancer patients,” she said.

Unanswered questions

Commenting on the study, Julie Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO, told this news organization that she thinks the take-home message is that there is “clearly a population of early-stage breast cancer [patients] who after lumpectomy do not benefit from radiation.”

“I think where there will be discussion will be what is the optimal way of identifying that group,” she said, noting that in this study the patients were screened for Ki67, a marker of proliferation.

Testing for Ki67 is not the standard of care, Dr. Gralow pointed out, and there is also a problem with reproducibility since “every lab does it somewhat differently, because it is not a standard pathology approach.”

There are now many unanswered questions, she noted. “Do we need that central testing of Ki67? Do we need to develop guidelines for how to do this? Is this better than if you’ve already run an Oncotype or a MammaPrint test to see if the patient needs chemo, then would that suffice? That is where the discussion will be. We can reduce the number of patients who need radiation without an increase in local regional recurrence.”

In terms of clinical practice, Dr. Gralow explained that there are already some data supporting the omission of radiation therapy in an older population with ER-positive small low-grade tumors, and this has become a standard clinical practice. “It’s not based on solid data, but based on an accumulation of retrospective analyses,” she said. “So we have already been doing it for an older population. This would bring down the age group, and it would better define it, and test it prospectively.”

Limitations to note

Also commenting on the study, Deborah Axelrod, MD, director of clinical breast surgery at New York University Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, explained that, in the last decade, knowledge about the behavior of breast cancers based on molecular subtyping has greatly increased. “Results of studies such as this have given us information on which cancers need more treatment and for which cancers we can de-escalate treatment,” she said. “Refining this more, it’s about reducing the morbidity and improving quality of life without compromising the oncological outcome.”

She noted that a big strength of this LUMINA study is that it is prospective and multicenter. “It has been supported by other past studies as well and will define for which patients with newly treated breast cancers can we omit radiation, which has been the standard of care,” said Dr. Axelrod. “It is based on the age and biology of breast cancer in defining which patient can forgo radiation and showed a low risk of recurrence in a specific population of women with a favorable breast cancer profile”

There were limitations to the study. “There is a 5-year follow-up and local recurrence for ER-positive cancers continues to rise after 5 years, so longer-term follow-up will be important,” she said. Also, she pointed out that it is a single-arm study so there is no radiation therapy comparison arm.

Other limitations were that the patients were older with smaller tumors, and all were committed to 5 years of endocrine therapy, although compliance with that has not been reported. There may be some older patients who prefer radiation therapy, especially a week of accelerated partial breast irradiation, rather than commit to 5 years of endocrine therapy as mandated in this study.

“Overall, the takeaway message for patients is that the omission of radiation therapy should be considered an option for older women with localized breast cancer with favorable features who receive endocrine therapies,” said Dr. Axelrod.

LUMINA was sponsored by the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation and the Canadian Cancer Society. Dr. Whelan has reported research funding from Exact Sciences (Inst). Dr. Axelrod and Dr. Anderson reported no disclosures. Dr. Gralow reported relationships with Genentech, AstraZeneca, Hexal, Puma BioTechnology, Roche, Novartis, Seagen, and Genomic Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCO 2022

Sleep-deprived physicians less empathetic to patient pain?

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

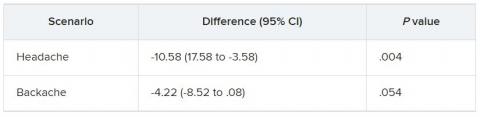

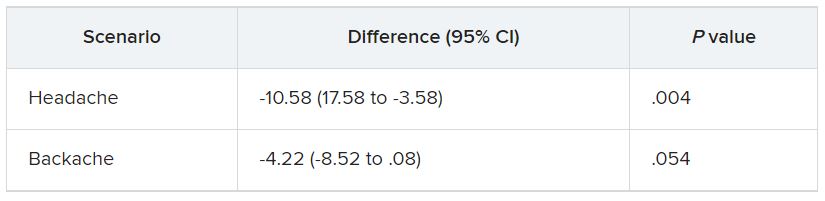

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

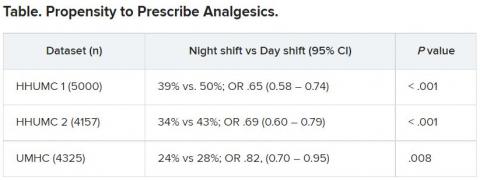

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.