User login

Cancer risk-reducing strategies: Focus on chemoprevention

In her presentation at The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2021 annual meeting (September 22–25, 2021, in Washington, DC), Dr. Holly J. Pederson offered her expert perspectives on breast cancer prevention in at-risk women in “Chemoprevention for risk reduction: Women’s health clinicians have a role.”

Which patients would benefit from chemoprevention?

Holly J. Pederson, MD: Obviously, women with significant family history are at risk. And approximately 10% of biopsies that are done for other reasons incidentally show atypical hyperplasia (AH) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)—which are not precancers or cancers but are markers for the development of the disease—and they markedly increase risk. Atypical hyperplasia confers a 30% risk for developing breast cancer over the next 25 years, and LCIS is associated with up to a 2% per year risk. In this setting, preventive medication has been shown to cut risk by 56% to 86%; this is a targeted population that is often overlooked.

Mathematical risk models can be used to assess risk by assessing women’s risk factors. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has set forth a threshold at which they believe the benefits outweigh the risks of preventive medications. That threshold is 3% or greater over the next 5 years using the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool.1 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) uses the Tyrer-Cuzick breast cancer risk evaluation model with a threshold of 5% over the next 10 years.2 In general, those are the situations in which chemoprevention is a no-brainer.

Certain genetic mutations also predispose to estrogen-sensitive breast cancer. While preventive medications specifically have not been studied in large groups of gene carriers, chemoprevention makes sense because these medications prevent estrogen-sensitive breast cancers that those patients are prone to. Examples would be patients with ATM and CHEK2 gene mutations, which are very common, and patients with BRCA2 and even BRCA1 variants in the postmenopausal years. Those are the big targets.

Risk assessment models

Dr. Pederson: Yes, I almost exclusively use the Tyrer-Cuzick risk model, version 8, which incorporates breast density. This model is intimidating to some practitioners initially, but once you get used to it, you can complete it very quickly.

The Gail model is very limited. It assesses only first-degree relatives, so you don’t get the paternal information at all, and you don’t use age at diagnosis, family structure, genetic testing, results of breast density, or body mass index (BMI). There are many limitations of the Gail model, but most people use it because it is so easy and they are familiar with it.

Possibly the best model is the CanRisk tool, which incorporates the Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm (BOADICEA), but it takes too much time to use in clinic; it’s too complicated. The Tyrer-Cuzick model is easy to use once you get used to it.

Dr. Pederson: Risk doesn’t always need to be formally calculated, which can be time-consuming. It’s one of those situations where most practitioners know it when they see it. Benign atypical biopsies, a strong family history, or, obviously, the presence of a genetic mutation are huge red flags.

If a practitioner has a nearby high-risk center where they can refer patients, that can be so useful, even for a one-time consultation to guide management. For example, with the virtual world now, I do a lot of consultations for patients and outline a plan, and then the referring practitioner can carry out the plan with confidence and then send the patient back periodically. There are so many more options now that previously did not exist for the busy ObGyn or primary care provider to rely on.

Continue to: Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women...

Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women

Dr. Pederson: We really never practice medicine using numbers. We use clinical judgment, and we use relationships with patients in terms of developing confidence and trust. I think that the uptake that we exhibit in our center probably is more based on the patients’ perception that we are confident in our recommendations. I think that many practitioners simply are not comfortable with explaining medications, explaining and managing adverse effects, and using alternative medications. While the modeling helps, I think the personal expertise really makes the difference.

Going forward, the addition of the polygenic risk score to the mathematical risk models is going to make a big difference. Right now, the mathematical risk model is simply that: it takes the traditional risk factors that a patient has and spits out a number. But adding the patient’s genomic data—that is, a weighted summation of SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms, now numbering over 300 for breast cancer—can explain more about their personalized risk, which is going to be more powerful in influencing a woman to take medication or not to take medication, in my opinion. Knowing their actual genomic risk will be a big step forward in individualized risk stratification and increased medication uptake as well as vigilance with high risk screening and attention to diet, exercise, and drinking alcohol in moderation.

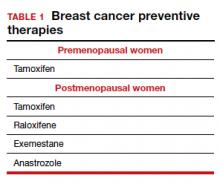

Dr. Pederson: The only drug that can be used in the premenopausal setting is tamoxifen (TABLE 1). Women can’t take it if they are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or if they don’t use a reliable form of birth control because it is teratogenic. Women also cannot take tamoxifen if they have had a history of blood clots, stroke, or transient ischemic attack; if they are on warfarin or estrogen preparations; or if they have had atypical endometrial biopsies or endometrial cancer. Those are the absolute contraindications for tamoxifen use.

Tamoxifen is generally very well tolerated in most women; some women experience hot flashes and night sweats that often will subside (or become tolerable) over the first 90 days. In addition, some women experience vaginal discharge rather than dryness, but it is not as bothersome to patients as dryness can be.

Tamoxifen can be used in the pre- or postmenopausal setting. In healthy premenopausal women, there’s no increased risk of the serious adverse effects that are seen with tamoxifen use in postmenopausal women, such as the 1% risk of blood clots and the 1% risk of endometrial cancer.

In postmenopausal women who still have their uterus, I’ll preferentially use raloxifene over tamoxifen. If they don’t have their uterus, tamoxifen is slightly more effective than the raloxifene, and I’ll use that.

Tamoxifen and raloxifene are both selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs, which means that they stimulate receptors in some tissues, like bone, keeping bones strong, and block the receptors in other tissues, like the breast, reducing risk. And so you get kind of a two-for-one in terms of breast cancer risk reduction and osteoporosis prevention.

Another class of preventive drugs is the aromatase inhibitors (AIs). They block the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens peripherally; that is, the androgens that are produced primarily in the adrenal gland, but in part in postmenopausal ovaries.

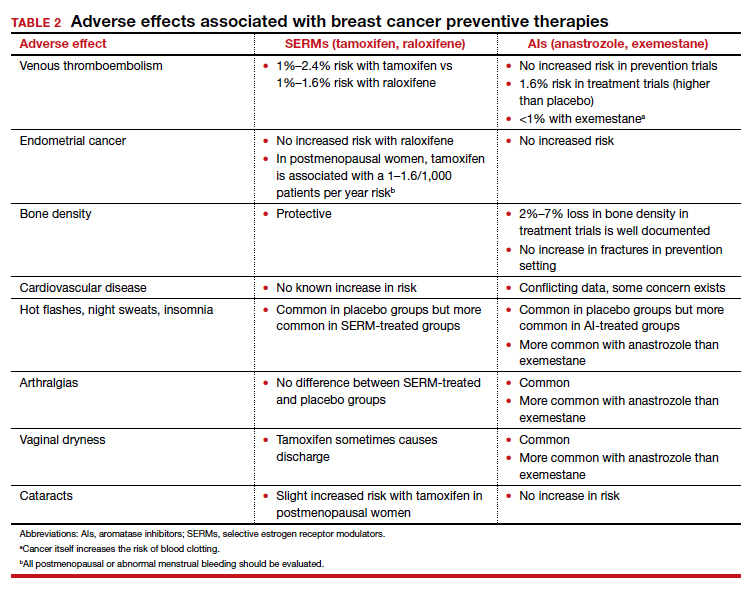

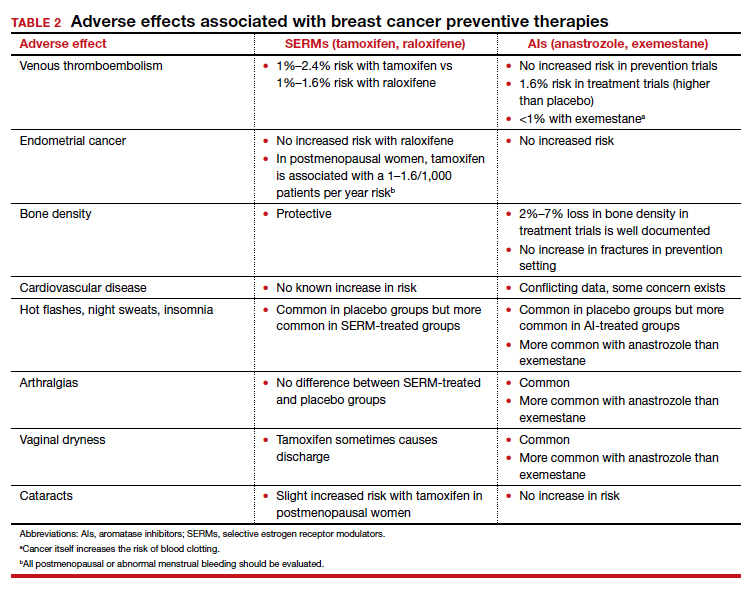

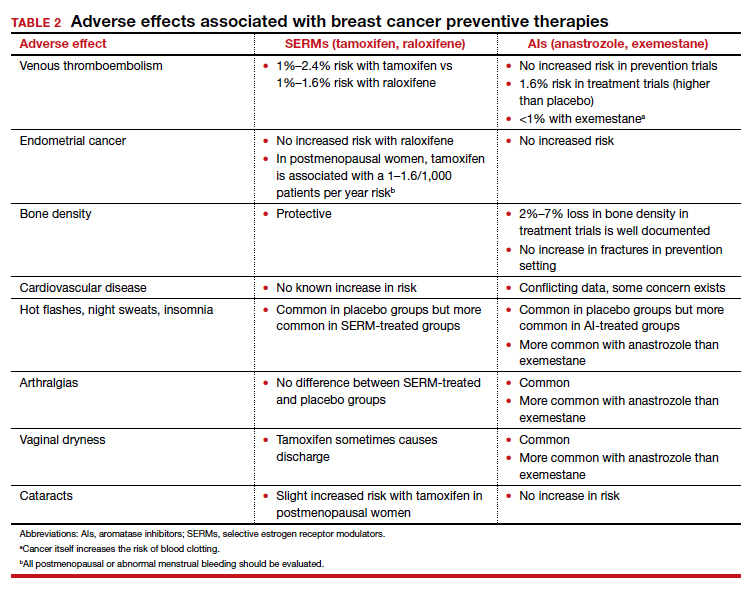

In general, AIs are less well tolerated. There are generally more hot flashes and night sweats, and more vaginal dryness than with the SERMs. Anastrozole use is associated with arthralgias; and with exemestane use, there can be some hair loss (TABLE 2). Relative contraindications to SERMs become more important in the postmenopausal setting because of the increased frequency of both blood clots and uterine cancer in the postmenopausal years. I won’t give it to smokers. I won’t give tamoxifen to smokers in the premenopausal period either. With obese women, care must be taken because of the risk of blood clots with the SERMS, so then I’ll resort to the AIs. In the postmenopausal setting, you have to think a lot harder about the choices you use for preventive medication. Preferentially, I’ll use the SERMS if possible as they have fewer adverse effects.

Dr. Pederson: All of them are recommended to be given for 5 years, but the MAP.3 trial, which studied exemestane compared with placebo, showed a 65% risk reduction with 3 years of therapy.3 So occasionally, we’ll use 3 years of therapy. Why the treatment recommendation is universally 5 years is unclear, given that the trial with that particular drug was done in 3 years. And with low-dose tamoxifen, the recommended duration is 3 years. That study was done in Italy with 5 mg daily for 3 years.4 In the United States we use 10 mg every other day for 3 years because the 5-mg tablet is not available here.

Continue to: Counseling points...

Counseling points

Dr. Pederson: Patients’ fears about adverse effects are often worse than the adverse effects themselves. Women will fester over, Should I take it? Should I take it possibly for years? And then they take the medication and they tell me, “I don’t even notice that I’m taking it, and I know I’m being proactive.” The majority of patients who take these medications don’t have a lot of significant adverse effects.

Severe hot flashes can be managed in a number of ways, primarily and most effectively with certain antidepressants. Oxybutynin use is another good way to manage vasomotor symptoms. Sometimes we use local vaginal estrogen if a patient has vaginal dryness. In general, however, I would say at least 80% of my patients who take preventive medications do not require management of adverse side effects, that they are tolerable.

I counsel women this way, “Don’t think of this as a 5-year course of medication. Think of it as a 90-day trial, and let’s see how you do. If you hate it, then we don’t do it.” They often are pleasantly surprised that the medication is much easier to tolerate than they thought it would be.

Dr. Pederson: It would be neat if a trial would directly compare lifestyle interventions with medications, because probably lifestyle change is as effective as medication is—but we don’t know that and probably will never have that data. We do know that alcohol consumption, every drink per day, increases risk by 10%. We know that obesity is responsible for 30% of breast cancers in this country, and that hormone replacement probably is overrated as a significant risk factor. Updated data from the Women’s Health Initiative study suggest that hormone replacement may actually reduce both breast cancer and cardiovascular risk in women in their 50s, but that’s in average-risk women and not in high-risk women, so we can’t generalize. We do recommend lifestyle measures including weight loss, exercise, and limiting alcohol consumption for all of our patients and certainly for our high-risk patients.

The only 2 things a woman can do to reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer are to achieve and maintain ideal body weight and to breastfeed. The medications that I have mentioned don’t reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer. Staying thin and breastfeeding do. It’s a problem in this country because at least 35% of all women and 58% of Black women are obese in America, and Black women tend to be prone to triple-negative breast cancer. That’s a real public health issue that we need to address. If we were going to focus on one thing, it would be focusing on obesity in terms of risk reduction.

Final thoughts

Dr. Pederson: I would like to direct attention to the American Heart Association scientific statement published at the end of 2020 that reported that hormone replacement in average-risk women reduced both cardiovascular events and overall mortality in women in their 50s by 30%.5 While that’s not directly related to what we are talking about, we need to weigh the pros and cons of estrogen versus estrogen blockade in women in terms of breast cancer risk management discussions. Part of shared decision making now needs to include cardiovascular risk factors and how estrogen is going to play into that.

In women with atypical hyperplasia or LCIS, they may benefit from the preventive medications we discussed. But in women with family history or in women with genetic mutations who have not had benign atypical biopsies, they may choose to consider estrogen during their 50s and perhaps take tamoxifen either beforehand or raloxifene afterward.

We need to look at patients holistically and consider all their risk factors together. We can’t look at one dimension alone.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:857-867.

- Visvanathan K, Fabian CJ, Bantug E, et al. Use of endocrine therapy for breast cancer risk reduction: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3152-3165.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alex-Martinez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2381-2391.

- DeCensi A, Puntoni M, Guerrieri-Gonzaga A, et al. Randomized placebo controlled trial of low-dose tamoxifen to prevent local and contralateral recurrence in breast intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1629-1637.

- El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al; American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e506-e532.

In her presentation at The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2021 annual meeting (September 22–25, 2021, in Washington, DC), Dr. Holly J. Pederson offered her expert perspectives on breast cancer prevention in at-risk women in “Chemoprevention for risk reduction: Women’s health clinicians have a role.”

Which patients would benefit from chemoprevention?

Holly J. Pederson, MD: Obviously, women with significant family history are at risk. And approximately 10% of biopsies that are done for other reasons incidentally show atypical hyperplasia (AH) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)—which are not precancers or cancers but are markers for the development of the disease—and they markedly increase risk. Atypical hyperplasia confers a 30% risk for developing breast cancer over the next 25 years, and LCIS is associated with up to a 2% per year risk. In this setting, preventive medication has been shown to cut risk by 56% to 86%; this is a targeted population that is often overlooked.

Mathematical risk models can be used to assess risk by assessing women’s risk factors. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has set forth a threshold at which they believe the benefits outweigh the risks of preventive medications. That threshold is 3% or greater over the next 5 years using the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool.1 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) uses the Tyrer-Cuzick breast cancer risk evaluation model with a threshold of 5% over the next 10 years.2 In general, those are the situations in which chemoprevention is a no-brainer.

Certain genetic mutations also predispose to estrogen-sensitive breast cancer. While preventive medications specifically have not been studied in large groups of gene carriers, chemoprevention makes sense because these medications prevent estrogen-sensitive breast cancers that those patients are prone to. Examples would be patients with ATM and CHEK2 gene mutations, which are very common, and patients with BRCA2 and even BRCA1 variants in the postmenopausal years. Those are the big targets.

Risk assessment models

Dr. Pederson: Yes, I almost exclusively use the Tyrer-Cuzick risk model, version 8, which incorporates breast density. This model is intimidating to some practitioners initially, but once you get used to it, you can complete it very quickly.

The Gail model is very limited. It assesses only first-degree relatives, so you don’t get the paternal information at all, and you don’t use age at diagnosis, family structure, genetic testing, results of breast density, or body mass index (BMI). There are many limitations of the Gail model, but most people use it because it is so easy and they are familiar with it.

Possibly the best model is the CanRisk tool, which incorporates the Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm (BOADICEA), but it takes too much time to use in clinic; it’s too complicated. The Tyrer-Cuzick model is easy to use once you get used to it.

Dr. Pederson: Risk doesn’t always need to be formally calculated, which can be time-consuming. It’s one of those situations where most practitioners know it when they see it. Benign atypical biopsies, a strong family history, or, obviously, the presence of a genetic mutation are huge red flags.

If a practitioner has a nearby high-risk center where they can refer patients, that can be so useful, even for a one-time consultation to guide management. For example, with the virtual world now, I do a lot of consultations for patients and outline a plan, and then the referring practitioner can carry out the plan with confidence and then send the patient back periodically. There are so many more options now that previously did not exist for the busy ObGyn or primary care provider to rely on.

Continue to: Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women...

Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women

Dr. Pederson: We really never practice medicine using numbers. We use clinical judgment, and we use relationships with patients in terms of developing confidence and trust. I think that the uptake that we exhibit in our center probably is more based on the patients’ perception that we are confident in our recommendations. I think that many practitioners simply are not comfortable with explaining medications, explaining and managing adverse effects, and using alternative medications. While the modeling helps, I think the personal expertise really makes the difference.

Going forward, the addition of the polygenic risk score to the mathematical risk models is going to make a big difference. Right now, the mathematical risk model is simply that: it takes the traditional risk factors that a patient has and spits out a number. But adding the patient’s genomic data—that is, a weighted summation of SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms, now numbering over 300 for breast cancer—can explain more about their personalized risk, which is going to be more powerful in influencing a woman to take medication or not to take medication, in my opinion. Knowing their actual genomic risk will be a big step forward in individualized risk stratification and increased medication uptake as well as vigilance with high risk screening and attention to diet, exercise, and drinking alcohol in moderation.

Dr. Pederson: The only drug that can be used in the premenopausal setting is tamoxifen (TABLE 1). Women can’t take it if they are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or if they don’t use a reliable form of birth control because it is teratogenic. Women also cannot take tamoxifen if they have had a history of blood clots, stroke, or transient ischemic attack; if they are on warfarin or estrogen preparations; or if they have had atypical endometrial biopsies or endometrial cancer. Those are the absolute contraindications for tamoxifen use.

Tamoxifen is generally very well tolerated in most women; some women experience hot flashes and night sweats that often will subside (or become tolerable) over the first 90 days. In addition, some women experience vaginal discharge rather than dryness, but it is not as bothersome to patients as dryness can be.

Tamoxifen can be used in the pre- or postmenopausal setting. In healthy premenopausal women, there’s no increased risk of the serious adverse effects that are seen with tamoxifen use in postmenopausal women, such as the 1% risk of blood clots and the 1% risk of endometrial cancer.

In postmenopausal women who still have their uterus, I’ll preferentially use raloxifene over tamoxifen. If they don’t have their uterus, tamoxifen is slightly more effective than the raloxifene, and I’ll use that.

Tamoxifen and raloxifene are both selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs, which means that they stimulate receptors in some tissues, like bone, keeping bones strong, and block the receptors in other tissues, like the breast, reducing risk. And so you get kind of a two-for-one in terms of breast cancer risk reduction and osteoporosis prevention.

Another class of preventive drugs is the aromatase inhibitors (AIs). They block the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens peripherally; that is, the androgens that are produced primarily in the adrenal gland, but in part in postmenopausal ovaries.

In general, AIs are less well tolerated. There are generally more hot flashes and night sweats, and more vaginal dryness than with the SERMs. Anastrozole use is associated with arthralgias; and with exemestane use, there can be some hair loss (TABLE 2). Relative contraindications to SERMs become more important in the postmenopausal setting because of the increased frequency of both blood clots and uterine cancer in the postmenopausal years. I won’t give it to smokers. I won’t give tamoxifen to smokers in the premenopausal period either. With obese women, care must be taken because of the risk of blood clots with the SERMS, so then I’ll resort to the AIs. In the postmenopausal setting, you have to think a lot harder about the choices you use for preventive medication. Preferentially, I’ll use the SERMS if possible as they have fewer adverse effects.

Dr. Pederson: All of them are recommended to be given for 5 years, but the MAP.3 trial, which studied exemestane compared with placebo, showed a 65% risk reduction with 3 years of therapy.3 So occasionally, we’ll use 3 years of therapy. Why the treatment recommendation is universally 5 years is unclear, given that the trial with that particular drug was done in 3 years. And with low-dose tamoxifen, the recommended duration is 3 years. That study was done in Italy with 5 mg daily for 3 years.4 In the United States we use 10 mg every other day for 3 years because the 5-mg tablet is not available here.

Continue to: Counseling points...

Counseling points

Dr. Pederson: Patients’ fears about adverse effects are often worse than the adverse effects themselves. Women will fester over, Should I take it? Should I take it possibly for years? And then they take the medication and they tell me, “I don’t even notice that I’m taking it, and I know I’m being proactive.” The majority of patients who take these medications don’t have a lot of significant adverse effects.

Severe hot flashes can be managed in a number of ways, primarily and most effectively with certain antidepressants. Oxybutynin use is another good way to manage vasomotor symptoms. Sometimes we use local vaginal estrogen if a patient has vaginal dryness. In general, however, I would say at least 80% of my patients who take preventive medications do not require management of adverse side effects, that they are tolerable.

I counsel women this way, “Don’t think of this as a 5-year course of medication. Think of it as a 90-day trial, and let’s see how you do. If you hate it, then we don’t do it.” They often are pleasantly surprised that the medication is much easier to tolerate than they thought it would be.

Dr. Pederson: It would be neat if a trial would directly compare lifestyle interventions with medications, because probably lifestyle change is as effective as medication is—but we don’t know that and probably will never have that data. We do know that alcohol consumption, every drink per day, increases risk by 10%. We know that obesity is responsible for 30% of breast cancers in this country, and that hormone replacement probably is overrated as a significant risk factor. Updated data from the Women’s Health Initiative study suggest that hormone replacement may actually reduce both breast cancer and cardiovascular risk in women in their 50s, but that’s in average-risk women and not in high-risk women, so we can’t generalize. We do recommend lifestyle measures including weight loss, exercise, and limiting alcohol consumption for all of our patients and certainly for our high-risk patients.

The only 2 things a woman can do to reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer are to achieve and maintain ideal body weight and to breastfeed. The medications that I have mentioned don’t reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer. Staying thin and breastfeeding do. It’s a problem in this country because at least 35% of all women and 58% of Black women are obese in America, and Black women tend to be prone to triple-negative breast cancer. That’s a real public health issue that we need to address. If we were going to focus on one thing, it would be focusing on obesity in terms of risk reduction.

Final thoughts

Dr. Pederson: I would like to direct attention to the American Heart Association scientific statement published at the end of 2020 that reported that hormone replacement in average-risk women reduced both cardiovascular events and overall mortality in women in their 50s by 30%.5 While that’s not directly related to what we are talking about, we need to weigh the pros and cons of estrogen versus estrogen blockade in women in terms of breast cancer risk management discussions. Part of shared decision making now needs to include cardiovascular risk factors and how estrogen is going to play into that.

In women with atypical hyperplasia or LCIS, they may benefit from the preventive medications we discussed. But in women with family history or in women with genetic mutations who have not had benign atypical biopsies, they may choose to consider estrogen during their 50s and perhaps take tamoxifen either beforehand or raloxifene afterward.

We need to look at patients holistically and consider all their risk factors together. We can’t look at one dimension alone.

In her presentation at The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2021 annual meeting (September 22–25, 2021, in Washington, DC), Dr. Holly J. Pederson offered her expert perspectives on breast cancer prevention in at-risk women in “Chemoprevention for risk reduction: Women’s health clinicians have a role.”

Which patients would benefit from chemoprevention?

Holly J. Pederson, MD: Obviously, women with significant family history are at risk. And approximately 10% of biopsies that are done for other reasons incidentally show atypical hyperplasia (AH) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)—which are not precancers or cancers but are markers for the development of the disease—and they markedly increase risk. Atypical hyperplasia confers a 30% risk for developing breast cancer over the next 25 years, and LCIS is associated with up to a 2% per year risk. In this setting, preventive medication has been shown to cut risk by 56% to 86%; this is a targeted population that is often overlooked.

Mathematical risk models can be used to assess risk by assessing women’s risk factors. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has set forth a threshold at which they believe the benefits outweigh the risks of preventive medications. That threshold is 3% or greater over the next 5 years using the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool.1 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) uses the Tyrer-Cuzick breast cancer risk evaluation model with a threshold of 5% over the next 10 years.2 In general, those are the situations in which chemoprevention is a no-brainer.

Certain genetic mutations also predispose to estrogen-sensitive breast cancer. While preventive medications specifically have not been studied in large groups of gene carriers, chemoprevention makes sense because these medications prevent estrogen-sensitive breast cancers that those patients are prone to. Examples would be patients with ATM and CHEK2 gene mutations, which are very common, and patients with BRCA2 and even BRCA1 variants in the postmenopausal years. Those are the big targets.

Risk assessment models

Dr. Pederson: Yes, I almost exclusively use the Tyrer-Cuzick risk model, version 8, which incorporates breast density. This model is intimidating to some practitioners initially, but once you get used to it, you can complete it very quickly.

The Gail model is very limited. It assesses only first-degree relatives, so you don’t get the paternal information at all, and you don’t use age at diagnosis, family structure, genetic testing, results of breast density, or body mass index (BMI). There are many limitations of the Gail model, but most people use it because it is so easy and they are familiar with it.

Possibly the best model is the CanRisk tool, which incorporates the Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm (BOADICEA), but it takes too much time to use in clinic; it’s too complicated. The Tyrer-Cuzick model is easy to use once you get used to it.

Dr. Pederson: Risk doesn’t always need to be formally calculated, which can be time-consuming. It’s one of those situations where most practitioners know it when they see it. Benign atypical biopsies, a strong family history, or, obviously, the presence of a genetic mutation are huge red flags.

If a practitioner has a nearby high-risk center where they can refer patients, that can be so useful, even for a one-time consultation to guide management. For example, with the virtual world now, I do a lot of consultations for patients and outline a plan, and then the referring practitioner can carry out the plan with confidence and then send the patient back periodically. There are so many more options now that previously did not exist for the busy ObGyn or primary care provider to rely on.

Continue to: Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women...

Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women

Dr. Pederson: We really never practice medicine using numbers. We use clinical judgment, and we use relationships with patients in terms of developing confidence and trust. I think that the uptake that we exhibit in our center probably is more based on the patients’ perception that we are confident in our recommendations. I think that many practitioners simply are not comfortable with explaining medications, explaining and managing adverse effects, and using alternative medications. While the modeling helps, I think the personal expertise really makes the difference.

Going forward, the addition of the polygenic risk score to the mathematical risk models is going to make a big difference. Right now, the mathematical risk model is simply that: it takes the traditional risk factors that a patient has and spits out a number. But adding the patient’s genomic data—that is, a weighted summation of SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms, now numbering over 300 for breast cancer—can explain more about their personalized risk, which is going to be more powerful in influencing a woman to take medication or not to take medication, in my opinion. Knowing their actual genomic risk will be a big step forward in individualized risk stratification and increased medication uptake as well as vigilance with high risk screening and attention to diet, exercise, and drinking alcohol in moderation.

Dr. Pederson: The only drug that can be used in the premenopausal setting is tamoxifen (TABLE 1). Women can’t take it if they are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or if they don’t use a reliable form of birth control because it is teratogenic. Women also cannot take tamoxifen if they have had a history of blood clots, stroke, or transient ischemic attack; if they are on warfarin or estrogen preparations; or if they have had atypical endometrial biopsies or endometrial cancer. Those are the absolute contraindications for tamoxifen use.

Tamoxifen is generally very well tolerated in most women; some women experience hot flashes and night sweats that often will subside (or become tolerable) over the first 90 days. In addition, some women experience vaginal discharge rather than dryness, but it is not as bothersome to patients as dryness can be.

Tamoxifen can be used in the pre- or postmenopausal setting. In healthy premenopausal women, there’s no increased risk of the serious adverse effects that are seen with tamoxifen use in postmenopausal women, such as the 1% risk of blood clots and the 1% risk of endometrial cancer.

In postmenopausal women who still have their uterus, I’ll preferentially use raloxifene over tamoxifen. If they don’t have their uterus, tamoxifen is slightly more effective than the raloxifene, and I’ll use that.

Tamoxifen and raloxifene are both selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs, which means that they stimulate receptors in some tissues, like bone, keeping bones strong, and block the receptors in other tissues, like the breast, reducing risk. And so you get kind of a two-for-one in terms of breast cancer risk reduction and osteoporosis prevention.

Another class of preventive drugs is the aromatase inhibitors (AIs). They block the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens peripherally; that is, the androgens that are produced primarily in the adrenal gland, but in part in postmenopausal ovaries.

In general, AIs are less well tolerated. There are generally more hot flashes and night sweats, and more vaginal dryness than with the SERMs. Anastrozole use is associated with arthralgias; and with exemestane use, there can be some hair loss (TABLE 2). Relative contraindications to SERMs become more important in the postmenopausal setting because of the increased frequency of both blood clots and uterine cancer in the postmenopausal years. I won’t give it to smokers. I won’t give tamoxifen to smokers in the premenopausal period either. With obese women, care must be taken because of the risk of blood clots with the SERMS, so then I’ll resort to the AIs. In the postmenopausal setting, you have to think a lot harder about the choices you use for preventive medication. Preferentially, I’ll use the SERMS if possible as they have fewer adverse effects.

Dr. Pederson: All of them are recommended to be given for 5 years, but the MAP.3 trial, which studied exemestane compared with placebo, showed a 65% risk reduction with 3 years of therapy.3 So occasionally, we’ll use 3 years of therapy. Why the treatment recommendation is universally 5 years is unclear, given that the trial with that particular drug was done in 3 years. And with low-dose tamoxifen, the recommended duration is 3 years. That study was done in Italy with 5 mg daily for 3 years.4 In the United States we use 10 mg every other day for 3 years because the 5-mg tablet is not available here.

Continue to: Counseling points...

Counseling points

Dr. Pederson: Patients’ fears about adverse effects are often worse than the adverse effects themselves. Women will fester over, Should I take it? Should I take it possibly for years? And then they take the medication and they tell me, “I don’t even notice that I’m taking it, and I know I’m being proactive.” The majority of patients who take these medications don’t have a lot of significant adverse effects.

Severe hot flashes can be managed in a number of ways, primarily and most effectively with certain antidepressants. Oxybutynin use is another good way to manage vasomotor symptoms. Sometimes we use local vaginal estrogen if a patient has vaginal dryness. In general, however, I would say at least 80% of my patients who take preventive medications do not require management of adverse side effects, that they are tolerable.

I counsel women this way, “Don’t think of this as a 5-year course of medication. Think of it as a 90-day trial, and let’s see how you do. If you hate it, then we don’t do it.” They often are pleasantly surprised that the medication is much easier to tolerate than they thought it would be.

Dr. Pederson: It would be neat if a trial would directly compare lifestyle interventions with medications, because probably lifestyle change is as effective as medication is—but we don’t know that and probably will never have that data. We do know that alcohol consumption, every drink per day, increases risk by 10%. We know that obesity is responsible for 30% of breast cancers in this country, and that hormone replacement probably is overrated as a significant risk factor. Updated data from the Women’s Health Initiative study suggest that hormone replacement may actually reduce both breast cancer and cardiovascular risk in women in their 50s, but that’s in average-risk women and not in high-risk women, so we can’t generalize. We do recommend lifestyle measures including weight loss, exercise, and limiting alcohol consumption for all of our patients and certainly for our high-risk patients.

The only 2 things a woman can do to reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer are to achieve and maintain ideal body weight and to breastfeed. The medications that I have mentioned don’t reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer. Staying thin and breastfeeding do. It’s a problem in this country because at least 35% of all women and 58% of Black women are obese in America, and Black women tend to be prone to triple-negative breast cancer. That’s a real public health issue that we need to address. If we were going to focus on one thing, it would be focusing on obesity in terms of risk reduction.

Final thoughts

Dr. Pederson: I would like to direct attention to the American Heart Association scientific statement published at the end of 2020 that reported that hormone replacement in average-risk women reduced both cardiovascular events and overall mortality in women in their 50s by 30%.5 While that’s not directly related to what we are talking about, we need to weigh the pros and cons of estrogen versus estrogen blockade in women in terms of breast cancer risk management discussions. Part of shared decision making now needs to include cardiovascular risk factors and how estrogen is going to play into that.

In women with atypical hyperplasia or LCIS, they may benefit from the preventive medications we discussed. But in women with family history or in women with genetic mutations who have not had benign atypical biopsies, they may choose to consider estrogen during their 50s and perhaps take tamoxifen either beforehand or raloxifene afterward.

We need to look at patients holistically and consider all their risk factors together. We can’t look at one dimension alone.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:857-867.

- Visvanathan K, Fabian CJ, Bantug E, et al. Use of endocrine therapy for breast cancer risk reduction: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3152-3165.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alex-Martinez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2381-2391.

- DeCensi A, Puntoni M, Guerrieri-Gonzaga A, et al. Randomized placebo controlled trial of low-dose tamoxifen to prevent local and contralateral recurrence in breast intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1629-1637.

- El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al; American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e506-e532.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:857-867.

- Visvanathan K, Fabian CJ, Bantug E, et al. Use of endocrine therapy for breast cancer risk reduction: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3152-3165.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alex-Martinez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2381-2391.

- DeCensi A, Puntoni M, Guerrieri-Gonzaga A, et al. Randomized placebo controlled trial of low-dose tamoxifen to prevent local and contralateral recurrence in breast intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1629-1637.

- El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al; American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e506-e532.

Cancer prevention through cascade genetic testing: A review of the current practice guidelines, barriers to testing and proposed solutions

CASE Woman with BRCA2 mutation

An 80-year-old woman presents for evaluation of newly diagnosed metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Her medical history is notable for breast cancer. Genetic testing of pancreatic tumor tissue detected a pathogenic variant in BRCA2. Family history revealed a history of melanoma as well as bladder, prostate, breast, and colon cancer. The patient subsequently underwent germline genetic testing with an 86-gene panel and a pathogenic mutation in BRCA2 was identified.

Watch a video of this patient and her clinician, Dr. Andrea Hagemann: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Methods of genetic testing

It is estimated that 1 in 300 to 1 in 500 women in the United States carry a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. This equates to between 250,000 and 415,000 women who are at high risk for breast and ovarian cancer.1 Looking at all women with cancer, 20% with ovarian,2 10% with breast,3 2% to 3% with endometrial,4 and 5% with colon cancer5 will have a germline mutation predisposing them to cancer. Identification of germline or somatic (tumor) mutations now inform treatment for patients with cancer. An equally important goal of germline genetic testing is cancer prevention. Cancer prevention strategies include risk-based screening for breast, colon, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer and prophylactic surgeries to reduce the risk of breast and ovarian cancer based on mutation type. Evidence-based screening guidelines by mutation type and absolute risk of associated cancers can be found on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).6,7

Multiple strategies have been proposed to identify patients for germline genetic testing. Patients can be identified based on a detailed multigenerational family history. This strategy requires clinicians or genetic counselors to take and update family histories, to recognize when a patient requires referral for testing, and for such testing to be completed. Even then the generation of a detailed pedigree is not very sensitive or specific. Population-based screening for high-penetrance breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility genes, regardless of family history, also has been proposed.8 Such a strategy has become increasingly realistic with decreasing cost and increasing availability of genetic testing. However, it would require increased genetic counseling resources to feasibly and equitably reach the target population and to explain the results to those patients and their relatives.

An alternative is to test the enriched population of family members of a patient with cancer who has been found to carry a pathogenic variant in a clinically relevant cancer susceptibility gene. This type of testing is termed cascade genetic testing. Cascade testing in first-degree family members carries a 50% probability of detecting the same pathogenic mutation. A related testing model is traceback testing where genetic testing is performed on pathology or tumor registry specimens from deceased patients with cancer.9 This genetic testing information is then provided to the family. Traceback models of genetic testing are an active area of research but can introduce ethical dilemmas. The more widely accepted cascade testing starts with the testing of a living patient affected with cancer. A recent article demonstrated the feasibility of a cascade testing model. Using a multiple linear regression model, the authors determined that all carriers of pathogenic mutations in 18 clinically relevant cancer susceptibility genes in the United States could be identified in 9.9 years if there was a 70% cascade testing rate of first-, second- and third-degree relatives, compared to 59.5 years with no cascade testing.10

Gaps in practice

Identification of mutation carriers, either through screening triggered by family history or through testing of patients affected with cancer, represents a gap between guidelines and clinical practice. Current NCCN guidelines outline genetic testing criteria for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome and for hereditary colorectal cancer. Despite well-established criteria, a survey in the United States revealed that only 19% of primary care providers were able to accurately assess family history for BRCA1 and 2 testing.11 Looking at patients who meet criteria for testing for Lynch syndrome, only 1 in 4 individuals have undergone genetic testing.12 Among patients diagnosed with breast and ovarian cancer, current NCCN guidelines recommend germline genetic testing for all patients with epithelial ovarian cancer; emerging evidence suggests all patients with breast cancer should be offered germline genetic testing.7,13 Large population-based studies have repeatedly demonstrated that testing rates fall short of this goal, with only 10% to 30% of patients undergoing genetic testing.9,14

Among families with a known hereditary mutation, rates of cascade genetic testing are also low, ranging from 17% to 50%.15-18 Evidence-based management guidelines, for both hereditary breast and ovarian cancer as well as Lynch syndrome, have been shown to reduce mortality.19,20 Failure to identify patients who carry these genetic mutations equates to increased mortality for our patients.

Barriers to cascade genetic testing

Cascade genetic testing ideally would be performed on entire families. Actual practice is far from ideal, and barriers to cascade testing exist. Barriers encompass resistance on the part of the family and provider as well as environmental or system factors.

Family factors

Because of privacy laws, the responsibility of disclosure of genetic testing results to family members falls primarily to the patient. Proband education is critical to ensure disclosure amongst family members. Family dynamics and geographic distribution of family members can further complicate disclosure. Following disclosure, family member gender, education, and demographics as well as personal views, attitudes, and emotions affect whether a family member decides to undergo testing.21 Furthermore, insurance status and awareness of and access to specialty-specific care for the proband’s family members may influence cascade genetic testing rates.

Provider factors

Provider factors that affect cascade genetic testing include awareness of testing guidelines, interpretation of genetic testing results, and education and knowledge of specific mutations. For instance, providers must recognize that cascade testing is not appropriate for variants of uncertain significance. This can lead to unnecessary surveillance testing and prophylactic surgeries. Providers, however, must continue to follow patients and periodically update testing results as variants may be reclassified over time. Additionally, providers must be knowledgeable about the complex and nuanced nature of the screening guidelines for each mutation. The NCCN provides detailed recommendations by mutation.7 Patients may benefit from care with cancer specialists who are aware of the guidelines, particularly for moderate-penetrance genes like BRIP1 and PALB2, as discussions about the timing of risk-reducing surgery are more nuanced in this population. Finally, which providers are responsible for facilitating cascade testing may be unclear; oncologists and genetic counselors not primarily treating probands’ relatives may assume the proper information has been passed along to family members without a practical means to follow up, and primary care providers may assume it is being taken care of by the oncology provider.

Continue to: Environmental or system factors...

Environmental or system factors

Accessibility of genetic counseling and testing is a common barrier to cascade testing. Family members may be geographically remote and connecting them to counseling and testing can be challenging. Working with local genetic counselors can facilitate this process. Insurance coverage of testing is a common perceived barrier; however, many testing companies now provide cascade testing free of charge if within a certain window from the initial test. Despite this, patients often site cost as a barrier to undergoing testing. Concerns about insurance coverage are common after a positive result. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 prohibits discrimination against employees or insurance applicants because of genetic information. Life insurance or long-term care policies, however, can incorporate genetic testing information into policy rates, so patients should be recommended to consider purchasing life insurance prior to undergoing genetic testing. This is especially important if the person considering testing has not yet been diagnosed with cancer.

Implications of a positive result

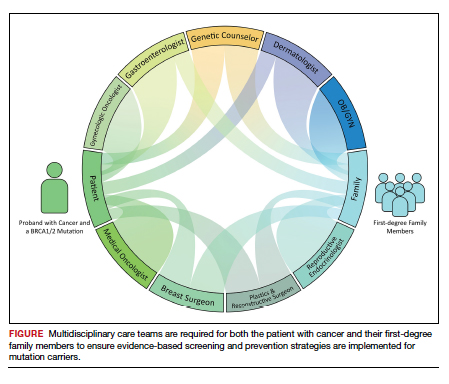

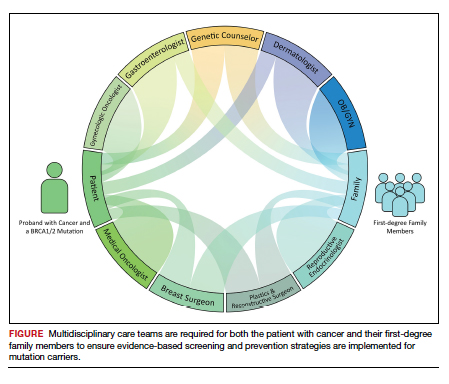

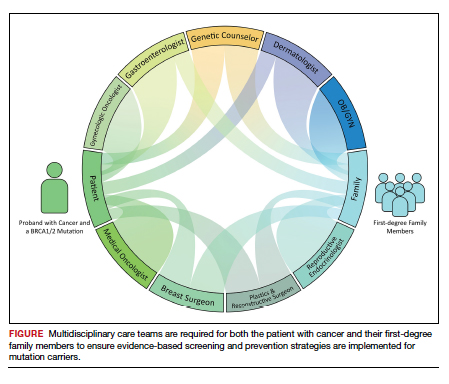

Family members who receive a positive test result should be referred for genetic counseling and to the appropriate specialists for evidence-based screening and discussion for risk-reducing surgery (FIGURE).7 For mutations associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, referral to breast and gynecologic surgeons with expertise in risk reducing surgery is critical as the risk of diagnosing an occult malignancy is approximately 1%.22 Surgical technique with a 2-cm margin on the

Patient resources: decision aids, websites

As genetic testing becomes more accessible and people are tested at younger ages, studies examining the balance of risk reduction and quality of life (QOL) are increasingly important. Fertility concerns, effects of early menopause, and the interrelatedness between decisions for breast and gynecologic risk reduction should all be considered in the counseling for surgical risk reduction. Patient decision aids can help mutation carriers navigate the complex information and decisions.25 Websites specifically designed by advocacy groups can be useful adjuncts to in-office counseling (Facing Our Risk Empowered, FORCE; Facingourrisk.org).

Family letters

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends an ObGyn have a letter or documentation stating that the patient’s relative has a specific mutation before initiating cascade testing for an at-risk family member. The indicated test (such as BRCA1) should be ordered only after the patient has been counseled about potential outcomes and has expressly decided to be tested.26 Letters, such as the example given in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin,26 are a key component of communication between oncology providers, probands, family members, and their primary care providers. ObGyn providers should work together with genetic counselors and gynecologic oncologists to determine the most efficient strategies in their communities.

Technology

Access to genetic testing and genetic counseling has been improved with the rise in telemedicine. Geographically remote patients can now access genetic counseling through medical center–based counselors as well as company-provided genetic counseling over the phone. Patients also can submit samples remotely without needing to be tested in a doctor’s office.

Databases from cancer centers that detail cascade genetic testing rates. As the preventive impact of cascade genetic testing becomes clearer, strategies to have recurrent discussions with cancer patients regarding their family members’ risk should be implemented. It is still unclear which providers—genetic counselors, gynecologic oncologists, medical oncologists, breast surgeons, ObGyns, to name a few—are primarily responsible for remembering to have these follow-up discussions, and despite advances, the burden still rests on the cancer patient themselves. Databases with automated follow-up surveys done every 6 to 12 months could provide some aid to busy providers in this regard.

Emerging research

If gynecologic risk-reducing surgery is chosen, clinical trial involvement should be encouraged. The Women Choosing Surgical Prevention (NCT02760849) in the United States and the TUBA study (NCT02321228) in the Netherlands were designed to compare menopause-related QOL between standard risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) and the innovative risk-reducing salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy for mutation carriers. Results from the nonrandomized controlled TUBA trial suggest that patients have better menopause-related QOL after risk-reducing salpingectomy than after RRSO, regardless of hormone replacement therapy.27 International collaboration is continuing to better understand oncologic safety. In the United States, the SOROCk trial (NCT04251052) is a noninferiority surgical choice study underway for BRCA1 mutation carriers aged 35 to 50, powered to determine oncologic outcome differences in addition to QOL outcomes between RRSO and delayed oophorectomy arms.

Returning to the case

The patient and her family underwent genetic counseling. The patient’s 2 daughters, each in their 50s, underwent cascade genetic testing and were found to carry the same pathogenic mutation in BRCA2. After counseling from both breast and gynecologic surgeons, they both elected to undergo risk reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy. Both now complete regular screening for breast cancer and melanoma with plans to start screening for pancreatic cancer. Both are currently cancer free.

Summary

Cascade genetic testing is an efficient strategy to identify mutation carriers for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Implementation of the best patient-centric care will require continued collaboration and communication across and within disciplines. ●

Cascade, or targeted, genetic testing within families known to carry a hereditary mutation in a cancer susceptibility gene should be performed on all living first-degree family members over the age of 18. All mutation carriers should be connected to a multidisciplinary care team (FIGURE) to ensure implementation of evidence-based screening and risk-reducing surgery for cancer prevention. If gynecologic risk-reducing surgery is chosen, clinical trial involvement should be encouraged.

- Gabai-Kapara E, Lahad A, Kaufman B, et al. Population-based screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk due to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:14205-14210.

- Norquist BM, Harrell MI, Brady MF, et al. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:482-490.

- Yamauchi H, Takei J. Management of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:45-51.

- Kahn RM, Gordhandas S, Maddy BP, et al. Universal endometrial cancer tumor typing: how much has immunohistochemistry, microsatellite instability, and MLH1 methylation improved the diagnosis of Lynch syndrome across the population? Cancer. 2019;125:3172-3183.

- Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, et al. Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2044-2058.

- Gupta S, Provenzale D, Llor X, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1032-1041.

- Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:77-102.

- King MC, Levy-Lahad E, Lahad A. Population-based screening for BRCA1 and BRCA2: 2014 Lasker Award. JAMA. 2014;312:1091-1092.

- Samimi G, et al. Traceback: a proposed framework to increase identification and genetic counseling of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers through family-based outreach. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2329-2337.

- Offit K, Tkachuk KA, Stadler ZK, et al. Cascading after peridiagnostic cancer genetic testing: an alternative to population-based screening. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1398-1408.

- Bellcross CA, Kolor K, Goddard KAB, et al. Awareness and utilization of BRCA1/2 testing among U.S. primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:61-66.

- Cross DS, Rahm AK, Kauffman TL, et al. Underutilization of Lynch syndrome screening in a multisite study of patients with colorectal cancer. Genet Med. 2013;15:933-940.

- Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Hughes K, et al. Underdiagnosis of hereditary breast cancer: are genetic testing guidelines a tool or an obstacle? J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:453-460.

- Childers CP, Childers KK, Maggard-Gibbons M, et al. National estimates of genetic testing in women with a history of breast or ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3800-3806.

- Samadder NJ, Riegert-Johnson D, Boardman L, et al. Comparison of universal genetic testing vs guideline-directed targeted testing for patients with hereditary cancer syndrome. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:230-237.

- Sharaf RN, Myer P, Stave CD, et al. Uptake of genetic testing by relatives of Lynch syndrome probands: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1093-1100.

- Menko FH, Ter Stege JA, van der Kolk LE, et al. The uptake of presymptomatic genetic testing in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome: a systematic review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. Fam Cancer. 2019;18:127-135.

- Griffin NE, Buchanan TR, Smith SH, et al. Low rates of cascade genetic testing among families with hereditary gynecologic cancer: an opportunity to improve cancer prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156:140-146.

- Roberts MC, Dotson WD, DeVore CS, et al. Delivery of cascade screening for hereditary conditions: a scoping review of the literature. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:801-808.

- Finch AP, Lubinski J, Møller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1547-1553.

- Srinivasan S, Won NY, Dotson WD, et al. Barriers and facilitators for cascade testing in genetic conditions: a systematic review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:1631-1644.

- Piedimonte S, Frank C, Laprise C, et al. Occult tubal carcinoma after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:498-508.

- Shu CA, Pike MC, Jotwani AR, et al. Uterine cancer after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy in women with BRCA mutations. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1434-1440.

- Gordhandas S, Norquist BM, Pennington KP, et al. Hormone replacement therapy after risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations; a systematic review of risks and benefits. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:192-200.

- Steenbeek MP, van Bommel MHD, Harmsen MG, et al. Evaluation of a patient decision aid for BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers choosing an ovarian cancer prevention strategy. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:371-377.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion No. 727: Cascade testing: testing women for known hereditary genetic mutations associated with cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:E31-E34.

- Steenbeek MP, Harmsen MG, Hoogerbrugge N, et al. Association of salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy versus salpingo-oophorectomy with quality of life in BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1203-1212.

CASE Woman with BRCA2 mutation

An 80-year-old woman presents for evaluation of newly diagnosed metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Her medical history is notable for breast cancer. Genetic testing of pancreatic tumor tissue detected a pathogenic variant in BRCA2. Family history revealed a history of melanoma as well as bladder, prostate, breast, and colon cancer. The patient subsequently underwent germline genetic testing with an 86-gene panel and a pathogenic mutation in BRCA2 was identified.

Watch a video of this patient and her clinician, Dr. Andrea Hagemann: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Methods of genetic testing

It is estimated that 1 in 300 to 1 in 500 women in the United States carry a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. This equates to between 250,000 and 415,000 women who are at high risk for breast and ovarian cancer.1 Looking at all women with cancer, 20% with ovarian,2 10% with breast,3 2% to 3% with endometrial,4 and 5% with colon cancer5 will have a germline mutation predisposing them to cancer. Identification of germline or somatic (tumor) mutations now inform treatment for patients with cancer. An equally important goal of germline genetic testing is cancer prevention. Cancer prevention strategies include risk-based screening for breast, colon, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer and prophylactic surgeries to reduce the risk of breast and ovarian cancer based on mutation type. Evidence-based screening guidelines by mutation type and absolute risk of associated cancers can be found on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).6,7

Multiple strategies have been proposed to identify patients for germline genetic testing. Patients can be identified based on a detailed multigenerational family history. This strategy requires clinicians or genetic counselors to take and update family histories, to recognize when a patient requires referral for testing, and for such testing to be completed. Even then the generation of a detailed pedigree is not very sensitive or specific. Population-based screening for high-penetrance breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility genes, regardless of family history, also has been proposed.8 Such a strategy has become increasingly realistic with decreasing cost and increasing availability of genetic testing. However, it would require increased genetic counseling resources to feasibly and equitably reach the target population and to explain the results to those patients and their relatives.

An alternative is to test the enriched population of family members of a patient with cancer who has been found to carry a pathogenic variant in a clinically relevant cancer susceptibility gene. This type of testing is termed cascade genetic testing. Cascade testing in first-degree family members carries a 50% probability of detecting the same pathogenic mutation. A related testing model is traceback testing where genetic testing is performed on pathology or tumor registry specimens from deceased patients with cancer.9 This genetic testing information is then provided to the family. Traceback models of genetic testing are an active area of research but can introduce ethical dilemmas. The more widely accepted cascade testing starts with the testing of a living patient affected with cancer. A recent article demonstrated the feasibility of a cascade testing model. Using a multiple linear regression model, the authors determined that all carriers of pathogenic mutations in 18 clinically relevant cancer susceptibility genes in the United States could be identified in 9.9 years if there was a 70% cascade testing rate of first-, second- and third-degree relatives, compared to 59.5 years with no cascade testing.10

Gaps in practice

Identification of mutation carriers, either through screening triggered by family history or through testing of patients affected with cancer, represents a gap between guidelines and clinical practice. Current NCCN guidelines outline genetic testing criteria for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome and for hereditary colorectal cancer. Despite well-established criteria, a survey in the United States revealed that only 19% of primary care providers were able to accurately assess family history for BRCA1 and 2 testing.11 Looking at patients who meet criteria for testing for Lynch syndrome, only 1 in 4 individuals have undergone genetic testing.12 Among patients diagnosed with breast and ovarian cancer, current NCCN guidelines recommend germline genetic testing for all patients with epithelial ovarian cancer; emerging evidence suggests all patients with breast cancer should be offered germline genetic testing.7,13 Large population-based studies have repeatedly demonstrated that testing rates fall short of this goal, with only 10% to 30% of patients undergoing genetic testing.9,14

Among families with a known hereditary mutation, rates of cascade genetic testing are also low, ranging from 17% to 50%.15-18 Evidence-based management guidelines, for both hereditary breast and ovarian cancer as well as Lynch syndrome, have been shown to reduce mortality.19,20 Failure to identify patients who carry these genetic mutations equates to increased mortality for our patients.

Barriers to cascade genetic testing

Cascade genetic testing ideally would be performed on entire families. Actual practice is far from ideal, and barriers to cascade testing exist. Barriers encompass resistance on the part of the family and provider as well as environmental or system factors.

Family factors

Because of privacy laws, the responsibility of disclosure of genetic testing results to family members falls primarily to the patient. Proband education is critical to ensure disclosure amongst family members. Family dynamics and geographic distribution of family members can further complicate disclosure. Following disclosure, family member gender, education, and demographics as well as personal views, attitudes, and emotions affect whether a family member decides to undergo testing.21 Furthermore, insurance status and awareness of and access to specialty-specific care for the proband’s family members may influence cascade genetic testing rates.

Provider factors

Provider factors that affect cascade genetic testing include awareness of testing guidelines, interpretation of genetic testing results, and education and knowledge of specific mutations. For instance, providers must recognize that cascade testing is not appropriate for variants of uncertain significance. This can lead to unnecessary surveillance testing and prophylactic surgeries. Providers, however, must continue to follow patients and periodically update testing results as variants may be reclassified over time. Additionally, providers must be knowledgeable about the complex and nuanced nature of the screening guidelines for each mutation. The NCCN provides detailed recommendations by mutation.7 Patients may benefit from care with cancer specialists who are aware of the guidelines, particularly for moderate-penetrance genes like BRIP1 and PALB2, as discussions about the timing of risk-reducing surgery are more nuanced in this population. Finally, which providers are responsible for facilitating cascade testing may be unclear; oncologists and genetic counselors not primarily treating probands’ relatives may assume the proper information has been passed along to family members without a practical means to follow up, and primary care providers may assume it is being taken care of by the oncology provider.

Continue to: Environmental or system factors...

Environmental or system factors

Accessibility of genetic counseling and testing is a common barrier to cascade testing. Family members may be geographically remote and connecting them to counseling and testing can be challenging. Working with local genetic counselors can facilitate this process. Insurance coverage of testing is a common perceived barrier; however, many testing companies now provide cascade testing free of charge if within a certain window from the initial test. Despite this, patients often site cost as a barrier to undergoing testing. Concerns about insurance coverage are common after a positive result. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 prohibits discrimination against employees or insurance applicants because of genetic information. Life insurance or long-term care policies, however, can incorporate genetic testing information into policy rates, so patients should be recommended to consider purchasing life insurance prior to undergoing genetic testing. This is especially important if the person considering testing has not yet been diagnosed with cancer.

Implications of a positive result

Family members who receive a positive test result should be referred for genetic counseling and to the appropriate specialists for evidence-based screening and discussion for risk-reducing surgery (FIGURE).7 For mutations associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, referral to breast and gynecologic surgeons with expertise in risk reducing surgery is critical as the risk of diagnosing an occult malignancy is approximately 1%.22 Surgical technique with a 2-cm margin on the

Patient resources: decision aids, websites

As genetic testing becomes more accessible and people are tested at younger ages, studies examining the balance of risk reduction and quality of life (QOL) are increasingly important. Fertility concerns, effects of early menopause, and the interrelatedness between decisions for breast and gynecologic risk reduction should all be considered in the counseling for surgical risk reduction. Patient decision aids can help mutation carriers navigate the complex information and decisions.25 Websites specifically designed by advocacy groups can be useful adjuncts to in-office counseling (Facing Our Risk Empowered, FORCE; Facingourrisk.org).

Family letters

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends an ObGyn have a letter or documentation stating that the patient’s relative has a specific mutation before initiating cascade testing for an at-risk family member. The indicated test (such as BRCA1) should be ordered only after the patient has been counseled about potential outcomes and has expressly decided to be tested.26 Letters, such as the example given in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin,26 are a key component of communication between oncology providers, probands, family members, and their primary care providers. ObGyn providers should work together with genetic counselors and gynecologic oncologists to determine the most efficient strategies in their communities.

Technology

Access to genetic testing and genetic counseling has been improved with the rise in telemedicine. Geographically remote patients can now access genetic counseling through medical center–based counselors as well as company-provided genetic counseling over the phone. Patients also can submit samples remotely without needing to be tested in a doctor’s office.

Databases from cancer centers that detail cascade genetic testing rates. As the preventive impact of cascade genetic testing becomes clearer, strategies to have recurrent discussions with cancer patients regarding their family members’ risk should be implemented. It is still unclear which providers—genetic counselors, gynecologic oncologists, medical oncologists, breast surgeons, ObGyns, to name a few—are primarily responsible for remembering to have these follow-up discussions, and despite advances, the burden still rests on the cancer patient themselves. Databases with automated follow-up surveys done every 6 to 12 months could provide some aid to busy providers in this regard.

Emerging research

If gynecologic risk-reducing surgery is chosen, clinical trial involvement should be encouraged. The Women Choosing Surgical Prevention (NCT02760849) in the United States and the TUBA study (NCT02321228) in the Netherlands were designed to compare menopause-related QOL between standard risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) and the innovative risk-reducing salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy for mutation carriers. Results from the nonrandomized controlled TUBA trial suggest that patients have better menopause-related QOL after risk-reducing salpingectomy than after RRSO, regardless of hormone replacement therapy.27 International collaboration is continuing to better understand oncologic safety. In the United States, the SOROCk trial (NCT04251052) is a noninferiority surgical choice study underway for BRCA1 mutation carriers aged 35 to 50, powered to determine oncologic outcome differences in addition to QOL outcomes between RRSO and delayed oophorectomy arms.

Returning to the case

The patient and her family underwent genetic counseling. The patient’s 2 daughters, each in their 50s, underwent cascade genetic testing and were found to carry the same pathogenic mutation in BRCA2. After counseling from both breast and gynecologic surgeons, they both elected to undergo risk reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy. Both now complete regular screening for breast cancer and melanoma with plans to start screening for pancreatic cancer. Both are currently cancer free.

Summary

Cascade genetic testing is an efficient strategy to identify mutation carriers for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Implementation of the best patient-centric care will require continued collaboration and communication across and within disciplines. ●

Cascade, or targeted, genetic testing within families known to carry a hereditary mutation in a cancer susceptibility gene should be performed on all living first-degree family members over the age of 18. All mutation carriers should be connected to a multidisciplinary care team (FIGURE) to ensure implementation of evidence-based screening and risk-reducing surgery for cancer prevention. If gynecologic risk-reducing surgery is chosen, clinical trial involvement should be encouraged.

CASE Woman with BRCA2 mutation

An 80-year-old woman presents for evaluation of newly diagnosed metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Her medical history is notable for breast cancer. Genetic testing of pancreatic tumor tissue detected a pathogenic variant in BRCA2. Family history revealed a history of melanoma as well as bladder, prostate, breast, and colon cancer. The patient subsequently underwent germline genetic testing with an 86-gene panel and a pathogenic mutation in BRCA2 was identified.

Watch a video of this patient and her clinician, Dr. Andrea Hagemann: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Methods of genetic testing

It is estimated that 1 in 300 to 1 in 500 women in the United States carry a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. This equates to between 250,000 and 415,000 women who are at high risk for breast and ovarian cancer.1 Looking at all women with cancer, 20% with ovarian,2 10% with breast,3 2% to 3% with endometrial,4 and 5% with colon cancer5 will have a germline mutation predisposing them to cancer. Identification of germline or somatic (tumor) mutations now inform treatment for patients with cancer. An equally important goal of germline genetic testing is cancer prevention. Cancer prevention strategies include risk-based screening for breast, colon, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer and prophylactic surgeries to reduce the risk of breast and ovarian cancer based on mutation type. Evidence-based screening guidelines by mutation type and absolute risk of associated cancers can be found on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).6,7

Multiple strategies have been proposed to identify patients for germline genetic testing. Patients can be identified based on a detailed multigenerational family history. This strategy requires clinicians or genetic counselors to take and update family histories, to recognize when a patient requires referral for testing, and for such testing to be completed. Even then the generation of a detailed pedigree is not very sensitive or specific. Population-based screening for high-penetrance breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility genes, regardless of family history, also has been proposed.8 Such a strategy has become increasingly realistic with decreasing cost and increasing availability of genetic testing. However, it would require increased genetic counseling resources to feasibly and equitably reach the target population and to explain the results to those patients and their relatives.

An alternative is to test the enriched population of family members of a patient with cancer who has been found to carry a pathogenic variant in a clinically relevant cancer susceptibility gene. This type of testing is termed cascade genetic testing. Cascade testing in first-degree family members carries a 50% probability of detecting the same pathogenic mutation. A related testing model is traceback testing where genetic testing is performed on pathology or tumor registry specimens from deceased patients with cancer.9 This genetic testing information is then provided to the family. Traceback models of genetic testing are an active area of research but can introduce ethical dilemmas. The more widely accepted cascade testing starts with the testing of a living patient affected with cancer. A recent article demonstrated the feasibility of a cascade testing model. Using a multiple linear regression model, the authors determined that all carriers of pathogenic mutations in 18 clinically relevant cancer susceptibility genes in the United States could be identified in 9.9 years if there was a 70% cascade testing rate of first-, second- and third-degree relatives, compared to 59.5 years with no cascade testing.10

Gaps in practice