User login

ACIP recommends MenACWY vaccine for HIV-infected persons 2 months and older

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices unanimously voted to recommend that all HIV-infected persons aged 2 months and older receive the meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) vaccine.

Guidance for this recommendation states that persons 2 months and older with HIV who have not been vaccinated previously should receive a two-dose, primary series of MenACWY; and that HIV-infected persons who have been vaccinated previously with one dose of MenACWY should receive a second dose at the earliest opportunity, with an 8-week minimum interval between doses. After that, boosters are to be given at the appropriate intervals.

Committee members voted in favor of immunizing earlier rather than waiting until 11 years of age or older, in part because human complement (hSBA) antibody titers following up to two doses of MenACWY vaccine in HIV-infected children ages 2-10 years is higher than in those ages 11-24 years. Also, the agreed upon recommended policy for earlier immunization is in step with current ACIP recommendations for use of the vaccine in persons with functional/anatomic asplenia or complement component deficiencies.

Despite an overall decline in the risk of meningococcal disease in the United States, there was a 13-fold increased risk in HIV-infected persons aged 25-64 years between 2000 and 2008, according to surveillance data presented to ACIP by Ms. Jessica MacNeil, MPH, an epidemiologist at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC in Atlanta. A ten-fold increase in risk was recorded in New York City alone in this population between 2000 and 2011.

Although fatality data are mixed, the infections were due primarily to serogroups C, W, and Y, for which the immune response wanes rapidly, according to Ms. MacNeil.

There are no safety or immunogenicity data currently available for the use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in HIV-infected persons, she said.

ACIP members also unanimously recommended this vaccine be covered under the Vaccines for Children program.

No information about disclosures was available at press time.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices unanimously voted to recommend that all HIV-infected persons aged 2 months and older receive the meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) vaccine.

Guidance for this recommendation states that persons 2 months and older with HIV who have not been vaccinated previously should receive a two-dose, primary series of MenACWY; and that HIV-infected persons who have been vaccinated previously with one dose of MenACWY should receive a second dose at the earliest opportunity, with an 8-week minimum interval between doses. After that, boosters are to be given at the appropriate intervals.

Committee members voted in favor of immunizing earlier rather than waiting until 11 years of age or older, in part because human complement (hSBA) antibody titers following up to two doses of MenACWY vaccine in HIV-infected children ages 2-10 years is higher than in those ages 11-24 years. Also, the agreed upon recommended policy for earlier immunization is in step with current ACIP recommendations for use of the vaccine in persons with functional/anatomic asplenia or complement component deficiencies.

Despite an overall decline in the risk of meningococcal disease in the United States, there was a 13-fold increased risk in HIV-infected persons aged 25-64 years between 2000 and 2008, according to surveillance data presented to ACIP by Ms. Jessica MacNeil, MPH, an epidemiologist at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC in Atlanta. A ten-fold increase in risk was recorded in New York City alone in this population between 2000 and 2011.

Although fatality data are mixed, the infections were due primarily to serogroups C, W, and Y, for which the immune response wanes rapidly, according to Ms. MacNeil.

There are no safety or immunogenicity data currently available for the use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in HIV-infected persons, she said.

ACIP members also unanimously recommended this vaccine be covered under the Vaccines for Children program.

No information about disclosures was available at press time.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices unanimously voted to recommend that all HIV-infected persons aged 2 months and older receive the meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) vaccine.

Guidance for this recommendation states that persons 2 months and older with HIV who have not been vaccinated previously should receive a two-dose, primary series of MenACWY; and that HIV-infected persons who have been vaccinated previously with one dose of MenACWY should receive a second dose at the earliest opportunity, with an 8-week minimum interval between doses. After that, boosters are to be given at the appropriate intervals.

Committee members voted in favor of immunizing earlier rather than waiting until 11 years of age or older, in part because human complement (hSBA) antibody titers following up to two doses of MenACWY vaccine in HIV-infected children ages 2-10 years is higher than in those ages 11-24 years. Also, the agreed upon recommended policy for earlier immunization is in step with current ACIP recommendations for use of the vaccine in persons with functional/anatomic asplenia or complement component deficiencies.

Despite an overall decline in the risk of meningococcal disease in the United States, there was a 13-fold increased risk in HIV-infected persons aged 25-64 years between 2000 and 2008, according to surveillance data presented to ACIP by Ms. Jessica MacNeil, MPH, an epidemiologist at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC in Atlanta. A ten-fold increase in risk was recorded in New York City alone in this population between 2000 and 2011.

Although fatality data are mixed, the infections were due primarily to serogroups C, W, and Y, for which the immune response wanes rapidly, according to Ms. MacNeil.

There are no safety or immunogenicity data currently available for the use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in HIV-infected persons, she said.

ACIP members also unanimously recommended this vaccine be covered under the Vaccines for Children program.

No information about disclosures was available at press time.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM AN ACIP MEETING

AAP, NASPAG issue joint guidance on menstruation management in teens with disabilities

For the first time, the American Academy of Pediatrics is offering guidance on managing menstruation and sexuality education in adolescents with disabilities.

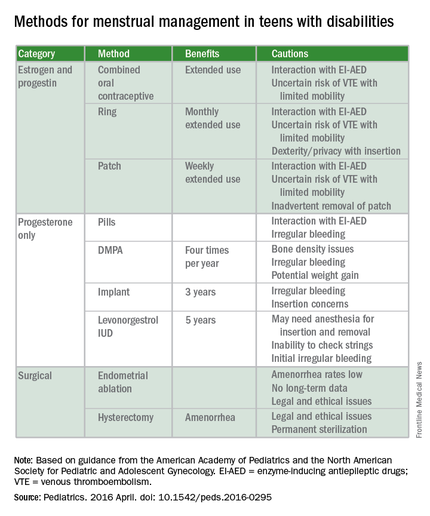

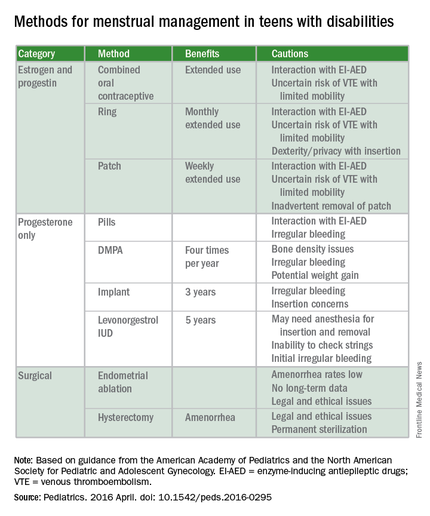

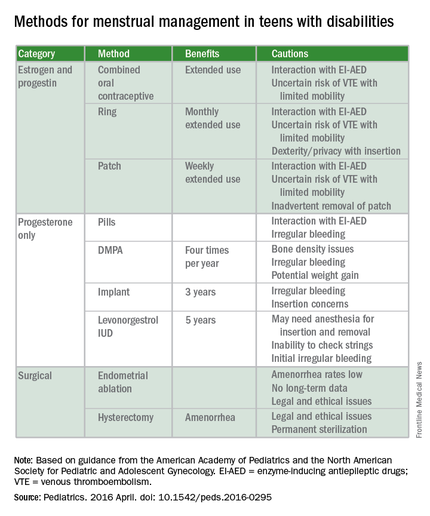

Written jointly with the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, the clinical report offers guidance on options for menstrual management, sexual education and expression, and protection from sexual abuse. The report gives guidance regarding the care of adolescents with physical and/or intellectual abilities, but not for those with psychiatric illnesses (Pediatrics. 2016 April. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0295).

“Taking care of teens with disabilities and figuring out what to do with menstrual management has been all over the map,” Dr. Cora Collette Breuner, chair of the AAP’s committee on adolescence, said in an interview. “So, we tried to clarify it and help clinicians know what to do and when.”

A particular concern for the two groups was the threat of adverse events. “We wanted to cover what’s safe and what’s not in menstruation management, especially around bone health and thromboembolic events,” said Dr. Breuner, a professor of pediatrics and adolescent medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Some of the information will not surprise clinicians, but there are some data that will perhaps come as news, said Dr. Breuner, including the recommendation that long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the levonorgestrel intrauterine device or the progesterone implant rod should be considered first-line management therapies. “We point out that a number of studies show that these are safe.”

The report emphasizes offering anticipatory guidance before menses begins, noting that most teens with disabilities mature at the same rate as teens without disabilities. The report does not recommend premenarchal suppression in these patients, because doing so can interfere with normal bone growth. Such suppression also prevents patients and their families and caregivers from discovering that coping with the onset of menses is perhaps not as difficult as they might fear, the report states.

Although combined oral contraceptives are not contraindicated in teens with mobility issues, to guard against the threat of thromboembolic events in teens who use wheelchairs, the report recommends taking a thorough family history to rule out inherited thrombophilia. Otherwise, the recommendation is to prescribe the lowest-dose estrogen with a first- or second-generation progestin, as these are associated with lower rates of venous thrombotic events.

The guidance states that if cycles are creating difficulties in the patient’s life, “as determined by health care providers, patients, and families,” then menstrual management is appropriate. Even though it may take up to 3 years before a menstrual cycle becomes regular, the report cites irregularities caused by certain medications can be reason enough for menstrual management. Specific drugs noted include those affecting the dopaminergic system, valproic acid, and medications that elevate prolactin. Teens with obesity, seizure disorders, and polycystic ovary syndrome also can experience higher rates of irregularity.

The report also warns against the assumption that teens with disabilities are asexual or uninterested in sex. When appropriate, they should be offered the same confidential conversations about sexuality as are recommended for all teenagers by the AAP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Teenagers with physical disabilities are just as likely to be sexually active as their peers and have a higher incidence of sexual abuse,” the report states. It is typically when a patient is cognitively impaired that consent to confidential services may require “discussion about legal guardianship or medical power of attorney status for families,” according to the report.

The report’s comprehensive review of four main menstrual management techniques – estrogen-containing, progestin-only, nonhormonal methods, and surgical requests and options – begins with the caveat that regardless of the method used, the threat of abuse or sexually transmitted infections remain. When a patient’s family or caregivers request suppression of menarche in a patient, stating fears of abuse or pregnancy, further investigation into the patient’s circumstances is warranted, the report states.

“It’s always worth reminding physicians that in this cohort, endometrial ablation can have legal implications, and it’s not recommended in this age group,” Dr. Breuner said.

On average, 1.5 hormonal methods are tried before achieving management goals, according to the report. Data cited in the study showed that at 42%, oral contraception is the preferred method of menstrual suppression, followed by the patch at 20%. Expectant management was third at 15%, followed by DMPA (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) at 12%. The least utilized method was the levonorgestrel intrauterine device at 3%. No data were provided for the implantable contraceptive rod.

The clinical report is a companion document to another AAP clinical report, “Sexuality of Children and Adolescents with Developmental Disabilities” (Pediatrics. 2006. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1115).

AAP guidance on these matters in teens with psychiatric illnesses is expected to be issued within a few years, Dr. Breuner said.

There was no external funding and the authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Although this guideline focuses on menstrual management and the guidance for you to help teens with disabilities through the pubertal transition, it’s very important to put this topic also into the context of sexuality. I think you have a great opportunity to do this because, often, you already have developed long-term relationships with these teenagers and their families, so the trust is already there. You should be the one to ensure all patients have appropriate sex education and help families with this.

|

Dr. Elisabeth Quint |

For some of these teens who are cognitively impaired, the initial conversations about sex may focus more on safety and abuse prevention. For example, which parts of their body should not be touched by other people. You can help the families really be the educators. Parents can be the ones to teach their kids how to protect themselves by rehearsing the answers to questions like, “What do you do if someone touches you? Who do you tell? Where do you go? What if it happens at school?” As part of the safety aspects, you also can help families assess whether the patient will be able to have a consensual sexual relationship. It’s the teens who have mild cognitive impairment that I worry about most, because often they are friendly and open to people, and can be taken advantage of. You just want to make sure they have the right information at their appropriate level.

Adolescents with physical disabilities are going to be just as interested in sex as any other teens and should be helped with any potential issues that they may have around that issue. They will likely get sex education in schools, but are still often viewed as not interested in sex or sexually active, and they may not get the usual confidential teen questions or appropriate screenings. Menstrual management and sexuality education both are important aspects of reproductive health care for teens with disabilities.

Dr. Elisabeth Quint, lead author of the AAP clinical report “Menstrual Management for Adolescents,” is a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She is also a past president of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Although this guideline focuses on menstrual management and the guidance for you to help teens with disabilities through the pubertal transition, it’s very important to put this topic also into the context of sexuality. I think you have a great opportunity to do this because, often, you already have developed long-term relationships with these teenagers and their families, so the trust is already there. You should be the one to ensure all patients have appropriate sex education and help families with this.

|

Dr. Elisabeth Quint |

For some of these teens who are cognitively impaired, the initial conversations about sex may focus more on safety and abuse prevention. For example, which parts of their body should not be touched by other people. You can help the families really be the educators. Parents can be the ones to teach their kids how to protect themselves by rehearsing the answers to questions like, “What do you do if someone touches you? Who do you tell? Where do you go? What if it happens at school?” As part of the safety aspects, you also can help families assess whether the patient will be able to have a consensual sexual relationship. It’s the teens who have mild cognitive impairment that I worry about most, because often they are friendly and open to people, and can be taken advantage of. You just want to make sure they have the right information at their appropriate level.

Adolescents with physical disabilities are going to be just as interested in sex as any other teens and should be helped with any potential issues that they may have around that issue. They will likely get sex education in schools, but are still often viewed as not interested in sex or sexually active, and they may not get the usual confidential teen questions or appropriate screenings. Menstrual management and sexuality education both are important aspects of reproductive health care for teens with disabilities.

Dr. Elisabeth Quint, lead author of the AAP clinical report “Menstrual Management for Adolescents,” is a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She is also a past president of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Although this guideline focuses on menstrual management and the guidance for you to help teens with disabilities through the pubertal transition, it’s very important to put this topic also into the context of sexuality. I think you have a great opportunity to do this because, often, you already have developed long-term relationships with these teenagers and their families, so the trust is already there. You should be the one to ensure all patients have appropriate sex education and help families with this.

|

Dr. Elisabeth Quint |

For some of these teens who are cognitively impaired, the initial conversations about sex may focus more on safety and abuse prevention. For example, which parts of their body should not be touched by other people. You can help the families really be the educators. Parents can be the ones to teach their kids how to protect themselves by rehearsing the answers to questions like, “What do you do if someone touches you? Who do you tell? Where do you go? What if it happens at school?” As part of the safety aspects, you also can help families assess whether the patient will be able to have a consensual sexual relationship. It’s the teens who have mild cognitive impairment that I worry about most, because often they are friendly and open to people, and can be taken advantage of. You just want to make sure they have the right information at their appropriate level.

Adolescents with physical disabilities are going to be just as interested in sex as any other teens and should be helped with any potential issues that they may have around that issue. They will likely get sex education in schools, but are still often viewed as not interested in sex or sexually active, and they may not get the usual confidential teen questions or appropriate screenings. Menstrual management and sexuality education both are important aspects of reproductive health care for teens with disabilities.

Dr. Elisabeth Quint, lead author of the AAP clinical report “Menstrual Management for Adolescents,” is a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She is also a past president of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

For the first time, the American Academy of Pediatrics is offering guidance on managing menstruation and sexuality education in adolescents with disabilities.

Written jointly with the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, the clinical report offers guidance on options for menstrual management, sexual education and expression, and protection from sexual abuse. The report gives guidance regarding the care of adolescents with physical and/or intellectual abilities, but not for those with psychiatric illnesses (Pediatrics. 2016 April. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0295).

“Taking care of teens with disabilities and figuring out what to do with menstrual management has been all over the map,” Dr. Cora Collette Breuner, chair of the AAP’s committee on adolescence, said in an interview. “So, we tried to clarify it and help clinicians know what to do and when.”

A particular concern for the two groups was the threat of adverse events. “We wanted to cover what’s safe and what’s not in menstruation management, especially around bone health and thromboembolic events,” said Dr. Breuner, a professor of pediatrics and adolescent medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Some of the information will not surprise clinicians, but there are some data that will perhaps come as news, said Dr. Breuner, including the recommendation that long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the levonorgestrel intrauterine device or the progesterone implant rod should be considered first-line management therapies. “We point out that a number of studies show that these are safe.”

The report emphasizes offering anticipatory guidance before menses begins, noting that most teens with disabilities mature at the same rate as teens without disabilities. The report does not recommend premenarchal suppression in these patients, because doing so can interfere with normal bone growth. Such suppression also prevents patients and their families and caregivers from discovering that coping with the onset of menses is perhaps not as difficult as they might fear, the report states.

Although combined oral contraceptives are not contraindicated in teens with mobility issues, to guard against the threat of thromboembolic events in teens who use wheelchairs, the report recommends taking a thorough family history to rule out inherited thrombophilia. Otherwise, the recommendation is to prescribe the lowest-dose estrogen with a first- or second-generation progestin, as these are associated with lower rates of venous thrombotic events.

The guidance states that if cycles are creating difficulties in the patient’s life, “as determined by health care providers, patients, and families,” then menstrual management is appropriate. Even though it may take up to 3 years before a menstrual cycle becomes regular, the report cites irregularities caused by certain medications can be reason enough for menstrual management. Specific drugs noted include those affecting the dopaminergic system, valproic acid, and medications that elevate prolactin. Teens with obesity, seizure disorders, and polycystic ovary syndrome also can experience higher rates of irregularity.

The report also warns against the assumption that teens with disabilities are asexual or uninterested in sex. When appropriate, they should be offered the same confidential conversations about sexuality as are recommended for all teenagers by the AAP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Teenagers with physical disabilities are just as likely to be sexually active as their peers and have a higher incidence of sexual abuse,” the report states. It is typically when a patient is cognitively impaired that consent to confidential services may require “discussion about legal guardianship or medical power of attorney status for families,” according to the report.

The report’s comprehensive review of four main menstrual management techniques – estrogen-containing, progestin-only, nonhormonal methods, and surgical requests and options – begins with the caveat that regardless of the method used, the threat of abuse or sexually transmitted infections remain. When a patient’s family or caregivers request suppression of menarche in a patient, stating fears of abuse or pregnancy, further investigation into the patient’s circumstances is warranted, the report states.

“It’s always worth reminding physicians that in this cohort, endometrial ablation can have legal implications, and it’s not recommended in this age group,” Dr. Breuner said.

On average, 1.5 hormonal methods are tried before achieving management goals, according to the report. Data cited in the study showed that at 42%, oral contraception is the preferred method of menstrual suppression, followed by the patch at 20%. Expectant management was third at 15%, followed by DMPA (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) at 12%. The least utilized method was the levonorgestrel intrauterine device at 3%. No data were provided for the implantable contraceptive rod.

The clinical report is a companion document to another AAP clinical report, “Sexuality of Children and Adolescents with Developmental Disabilities” (Pediatrics. 2006. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1115).

AAP guidance on these matters in teens with psychiatric illnesses is expected to be issued within a few years, Dr. Breuner said.

There was no external funding and the authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

For the first time, the American Academy of Pediatrics is offering guidance on managing menstruation and sexuality education in adolescents with disabilities.

Written jointly with the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, the clinical report offers guidance on options for menstrual management, sexual education and expression, and protection from sexual abuse. The report gives guidance regarding the care of adolescents with physical and/or intellectual abilities, but not for those with psychiatric illnesses (Pediatrics. 2016 April. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0295).

“Taking care of teens with disabilities and figuring out what to do with menstrual management has been all over the map,” Dr. Cora Collette Breuner, chair of the AAP’s committee on adolescence, said in an interview. “So, we tried to clarify it and help clinicians know what to do and when.”

A particular concern for the two groups was the threat of adverse events. “We wanted to cover what’s safe and what’s not in menstruation management, especially around bone health and thromboembolic events,” said Dr. Breuner, a professor of pediatrics and adolescent medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Some of the information will not surprise clinicians, but there are some data that will perhaps come as news, said Dr. Breuner, including the recommendation that long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the levonorgestrel intrauterine device or the progesterone implant rod should be considered first-line management therapies. “We point out that a number of studies show that these are safe.”

The report emphasizes offering anticipatory guidance before menses begins, noting that most teens with disabilities mature at the same rate as teens without disabilities. The report does not recommend premenarchal suppression in these patients, because doing so can interfere with normal bone growth. Such suppression also prevents patients and their families and caregivers from discovering that coping with the onset of menses is perhaps not as difficult as they might fear, the report states.

Although combined oral contraceptives are not contraindicated in teens with mobility issues, to guard against the threat of thromboembolic events in teens who use wheelchairs, the report recommends taking a thorough family history to rule out inherited thrombophilia. Otherwise, the recommendation is to prescribe the lowest-dose estrogen with a first- or second-generation progestin, as these are associated with lower rates of venous thrombotic events.

The guidance states that if cycles are creating difficulties in the patient’s life, “as determined by health care providers, patients, and families,” then menstrual management is appropriate. Even though it may take up to 3 years before a menstrual cycle becomes regular, the report cites irregularities caused by certain medications can be reason enough for menstrual management. Specific drugs noted include those affecting the dopaminergic system, valproic acid, and medications that elevate prolactin. Teens with obesity, seizure disorders, and polycystic ovary syndrome also can experience higher rates of irregularity.

The report also warns against the assumption that teens with disabilities are asexual or uninterested in sex. When appropriate, they should be offered the same confidential conversations about sexuality as are recommended for all teenagers by the AAP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Teenagers with physical disabilities are just as likely to be sexually active as their peers and have a higher incidence of sexual abuse,” the report states. It is typically when a patient is cognitively impaired that consent to confidential services may require “discussion about legal guardianship or medical power of attorney status for families,” according to the report.

The report’s comprehensive review of four main menstrual management techniques – estrogen-containing, progestin-only, nonhormonal methods, and surgical requests and options – begins with the caveat that regardless of the method used, the threat of abuse or sexually transmitted infections remain. When a patient’s family or caregivers request suppression of menarche in a patient, stating fears of abuse or pregnancy, further investigation into the patient’s circumstances is warranted, the report states.

“It’s always worth reminding physicians that in this cohort, endometrial ablation can have legal implications, and it’s not recommended in this age group,” Dr. Breuner said.

On average, 1.5 hormonal methods are tried before achieving management goals, according to the report. Data cited in the study showed that at 42%, oral contraception is the preferred method of menstrual suppression, followed by the patch at 20%. Expectant management was third at 15%, followed by DMPA (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) at 12%. The least utilized method was the levonorgestrel intrauterine device at 3%. No data were provided for the implantable contraceptive rod.

The clinical report is a companion document to another AAP clinical report, “Sexuality of Children and Adolescents with Developmental Disabilities” (Pediatrics. 2006. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1115).

AAP guidance on these matters in teens with psychiatric illnesses is expected to be issued within a few years, Dr. Breuner said.

There was no external funding and the authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM PEDIATRICS

Psychiatry’s role rising in hospital care

BALTIMORE – A team of physicians and mental health experts at Johns Hopkins Hospital is trying something new: combining mental health services with medical ones. Hospital leadership hopes the experiment will pay off in shorter lengths of stay, lower readmission rates, and better overall patient care.

“We’re still collecting that data,” Melissa Richardson, the hospital’s director of care coordination, said in an interview. “We also will look at the impact on staffing ratios on the units. For example, has the number of patient observers gone down? Has the overall severity of certain cases on the unit been reduced by embedding mental health workers there?”

The medical-surgical mental health team debuted in April, and is separate from the hospital’s other psychiatric services. Comprised of a social worker, a nurse practitioner, a nurse care coordinator, and an attending psychiatrist, the team typically works a regular day shift, beginning each morning with patient chart reviews prepared by medical-surgical personnel. They discuss which patients will be seen by whom, since all team members are trained to do psychiatric evaluations.

Not all medical patients require psychiatric care, but according to the program’s clinical director and attending psychiatrist, Dr. Patrick T. Triplett, up to 38% of all medical admissions have a psychiatric comorbidity. Addressing those comorbidities while patients are in the hospital often leads to improved outcomes.

The team’s social worker connects patients with the appropriate outpatient mental health services in the community, and the team’s nurse care coordinator arranges any necessary transfers from the medical-surgical units to the inpatient psychiatric unit. Dr. Triplett and the psychiatric nurse practitioner are the only two team members who can diagnose and prescribe. Dr. Triplett’s time is billed as consultation services, and the hospital absorbs the cost of the rest of the team, according to Ms. Richardson.

‘Complex medically ill’ patients

As some procedures and medical treatments have shifted to the outpatient setting in recent years, and joint replacements or acute conditions such as myocardial infarctions can be managed successfully in shorter stays, more complicated patients, such as joint replacement patients who develop delirium, have been left on the medical-surgical unit, said Dr. Constantine G. Lyketsos, the Elizabeth Plank Althouse Professor at Johns Hopkins Bayview, Baltimore.

“Also, these days, up to 20% of our admissions are linked to opioids. Then, there are the chronically mentally ill. They tend to be a population with high rates of obesity, smoking, and diabetes, so they end up in the hospital with higher-level, more complicated conditions, that because of the disintegration of the mental health system, receive neither good psychiatric nor outpatient medical care,” Dr. Lyketsos, also chief of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Bayview, said in an interview.

This surge in the number of complex medically ill patients has led to a growing number of hospitals nationwide calling upon psychiatrists for help in improving overall care. Hopkins is only the latest to join the ranks of other institutions such as Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn (N.Y.), Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., and New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City.

The progenitor of this collaborative inpatient care model is Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital. The behavioral intervention team (BIT) at Yale New Haven includes nurses, social workers, and psychiatrists who proactively screen for and address behavioral barriers to care for medical patients with a co-occurring mental illness, said Dr. Hochang B. Lee, one of the psychiatrists who helped created the model in 2008. Dr. Lee is Yale’s psychological medicine section chief and director of the school’s Psychological Medicine Research Center. He also is an associate professor of psychiatry and an associate clinical professor of nursing.

“The goal was to create a proactive model of care, not the reactive one that is traditional consultation-liaison psychiatry,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “Before the BIT model, medical teams often missed behavioral issues or made consultation requests too late in the course of hospitalization to avoid psychiatric crisis.”

LOS, costs reduced

A study

“The hospital is not making money off of us, but they’re losing less money because of us. That’s good!” Dr. Philip R. Muskin, chief of consultation-liaison psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia, said in an interview.

Patients at New York Presbyterian have been comanaged since 2004 when, according to Dr. Muskin, a donor gift specifically intended for such a purpose was matched by the hospital’s department of medicine. The unspent money was enough to cover the cost of a consultation-liaison psychiatrist to round full time as an attending with the medical team.

“We were lucky at NYPCH, because someone gave us the gift to hire a full-time psychiatrist we could embed into the medical team,” Dr. Muskin said. “But there is no one right way to deliver collaborative care in the inpatient setting.”

The NYPCH program has grown to include a second full-time and one part-time psychiatrist, serving about half of all medical services at the campus, with plans to hire more. There is also a social worker to assist with outplacement services. Dr. Muskin said he is currently looking to hire a psychiatric nurse practitioner.

‘Nurses love us’

Restoration of staff morale is another benefit to this kind of practice, according to Maureen Lewis, an accredited psychiatric nurse practitioner who is part of the Hopkins integrated team.

“Med-surge nurses love us. Patients who come in with an overdose or who have any psychiatric conditions but need to have their medical comorbidities dealt with first, they are at their sickest with their psychiatric illnesses when they first arrive,” Ms. Lewis said. “It’s the med-surge nurses who have to care for them, but it’s not their comfort zone or their skill set. They like that we are helping them manage the patient.”

A decline in the number of assaults on the nursing staff also has been recorded since the Hopkins program began, Dr. Lyketsos said.

The psychiatrists themselves tend to be happier, too. “Knowing the cases before you even walk up on the unit is a huge benefit,” Dr. Triplett said. “To have to dive into an emergency all the time is just exhausting. It changes your relationship with the patient. When you’re not in that crisis mode, the patient isn’t a ‘problem’ anymore.”

A formal assessment of the entire medical-surgical staff satisfaction involved in the Hopkins program also is underway, said Ms. Richardson, the director of care coordination.

Having psychiatrists at the fore of this evolution in care provides more opportunities for training, too.

The comanagement model gives medical staff a chance to learn more not just about the direct care of complex behaviorally disordered patients, but also to understand their own emotions and states of mind as they interact with these patients. The teaching happens naturally as the team discusses patients while making rounds, Dr. Muskin said. “That’s really an integral part of what consult-liaison psychiatry is supposed to be about, anyway.”

By helping the medical staff reflect on their experiences, Dr. Muskin said, psychiatrists are helping to change the culture of inpatient medicine. “Once you change the culture, if you keep the things that brought it about in place, it doesn’t change back.”

Creating bridge services

A problem with this kind of inpatient collaborative care model is that hospitals that run them aren’t able to control all the variables associated with the cost of providing them.

The hope is that by spending more up front to identify and treat high-risk behavioral health patients, they won’t need readmission; but if the appropriate follow-up care can’t be found on the outpatient side, they could still end up back in the hospital, driving up readmission rates and possibly lengths of stay.

To address such contingencies, Hopkins has participated in state-sponsored partnerships for improving community care and is using monies from accountable care organization funding to create bridge services. The hospital system also has 14 primary care practices that have embedded psychiatric services, and the plan is to create a team to care for more complicated patients who need care 60-90 days after discharge.

For Dr. Lyketsos, however, fixing what he says is a broken mental health system isn’t up to the hospital alone. “We’re not going to be able to bring about real change without working with our legislators and our payers. It’s a complex problem that needs a complex solution. But there is a commonality of mind that we need to fix things, that patients need better care – and that this is a good place to start.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CORRECTION, 6/28/16: A previous version of this article misstated Dr. Hochang B. Lee's name.

BALTIMORE – A team of physicians and mental health experts at Johns Hopkins Hospital is trying something new: combining mental health services with medical ones. Hospital leadership hopes the experiment will pay off in shorter lengths of stay, lower readmission rates, and better overall patient care.

“We’re still collecting that data,” Melissa Richardson, the hospital’s director of care coordination, said in an interview. “We also will look at the impact on staffing ratios on the units. For example, has the number of patient observers gone down? Has the overall severity of certain cases on the unit been reduced by embedding mental health workers there?”

The medical-surgical mental health team debuted in April, and is separate from the hospital’s other psychiatric services. Comprised of a social worker, a nurse practitioner, a nurse care coordinator, and an attending psychiatrist, the team typically works a regular day shift, beginning each morning with patient chart reviews prepared by medical-surgical personnel. They discuss which patients will be seen by whom, since all team members are trained to do psychiatric evaluations.

Not all medical patients require psychiatric care, but according to the program’s clinical director and attending psychiatrist, Dr. Patrick T. Triplett, up to 38% of all medical admissions have a psychiatric comorbidity. Addressing those comorbidities while patients are in the hospital often leads to improved outcomes.

The team’s social worker connects patients with the appropriate outpatient mental health services in the community, and the team’s nurse care coordinator arranges any necessary transfers from the medical-surgical units to the inpatient psychiatric unit. Dr. Triplett and the psychiatric nurse practitioner are the only two team members who can diagnose and prescribe. Dr. Triplett’s time is billed as consultation services, and the hospital absorbs the cost of the rest of the team, according to Ms. Richardson.

‘Complex medically ill’ patients

As some procedures and medical treatments have shifted to the outpatient setting in recent years, and joint replacements or acute conditions such as myocardial infarctions can be managed successfully in shorter stays, more complicated patients, such as joint replacement patients who develop delirium, have been left on the medical-surgical unit, said Dr. Constantine G. Lyketsos, the Elizabeth Plank Althouse Professor at Johns Hopkins Bayview, Baltimore.

“Also, these days, up to 20% of our admissions are linked to opioids. Then, there are the chronically mentally ill. They tend to be a population with high rates of obesity, smoking, and diabetes, so they end up in the hospital with higher-level, more complicated conditions, that because of the disintegration of the mental health system, receive neither good psychiatric nor outpatient medical care,” Dr. Lyketsos, also chief of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Bayview, said in an interview.

This surge in the number of complex medically ill patients has led to a growing number of hospitals nationwide calling upon psychiatrists for help in improving overall care. Hopkins is only the latest to join the ranks of other institutions such as Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn (N.Y.), Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., and New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City.

The progenitor of this collaborative inpatient care model is Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital. The behavioral intervention team (BIT) at Yale New Haven includes nurses, social workers, and psychiatrists who proactively screen for and address behavioral barriers to care for medical patients with a co-occurring mental illness, said Dr. Hochang B. Lee, one of the psychiatrists who helped created the model in 2008. Dr. Lee is Yale’s psychological medicine section chief and director of the school’s Psychological Medicine Research Center. He also is an associate professor of psychiatry and an associate clinical professor of nursing.

“The goal was to create a proactive model of care, not the reactive one that is traditional consultation-liaison psychiatry,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “Before the BIT model, medical teams often missed behavioral issues or made consultation requests too late in the course of hospitalization to avoid psychiatric crisis.”

LOS, costs reduced

A study

“The hospital is not making money off of us, but they’re losing less money because of us. That’s good!” Dr. Philip R. Muskin, chief of consultation-liaison psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia, said in an interview.

Patients at New York Presbyterian have been comanaged since 2004 when, according to Dr. Muskin, a donor gift specifically intended for such a purpose was matched by the hospital’s department of medicine. The unspent money was enough to cover the cost of a consultation-liaison psychiatrist to round full time as an attending with the medical team.

“We were lucky at NYPCH, because someone gave us the gift to hire a full-time psychiatrist we could embed into the medical team,” Dr. Muskin said. “But there is no one right way to deliver collaborative care in the inpatient setting.”

The NYPCH program has grown to include a second full-time and one part-time psychiatrist, serving about half of all medical services at the campus, with plans to hire more. There is also a social worker to assist with outplacement services. Dr. Muskin said he is currently looking to hire a psychiatric nurse practitioner.

‘Nurses love us’

Restoration of staff morale is another benefit to this kind of practice, according to Maureen Lewis, an accredited psychiatric nurse practitioner who is part of the Hopkins integrated team.

“Med-surge nurses love us. Patients who come in with an overdose or who have any psychiatric conditions but need to have their medical comorbidities dealt with first, they are at their sickest with their psychiatric illnesses when they first arrive,” Ms. Lewis said. “It’s the med-surge nurses who have to care for them, but it’s not their comfort zone or their skill set. They like that we are helping them manage the patient.”

A decline in the number of assaults on the nursing staff also has been recorded since the Hopkins program began, Dr. Lyketsos said.

The psychiatrists themselves tend to be happier, too. “Knowing the cases before you even walk up on the unit is a huge benefit,” Dr. Triplett said. “To have to dive into an emergency all the time is just exhausting. It changes your relationship with the patient. When you’re not in that crisis mode, the patient isn’t a ‘problem’ anymore.”

A formal assessment of the entire medical-surgical staff satisfaction involved in the Hopkins program also is underway, said Ms. Richardson, the director of care coordination.

Having psychiatrists at the fore of this evolution in care provides more opportunities for training, too.

The comanagement model gives medical staff a chance to learn more not just about the direct care of complex behaviorally disordered patients, but also to understand their own emotions and states of mind as they interact with these patients. The teaching happens naturally as the team discusses patients while making rounds, Dr. Muskin said. “That’s really an integral part of what consult-liaison psychiatry is supposed to be about, anyway.”

By helping the medical staff reflect on their experiences, Dr. Muskin said, psychiatrists are helping to change the culture of inpatient medicine. “Once you change the culture, if you keep the things that brought it about in place, it doesn’t change back.”

Creating bridge services

A problem with this kind of inpatient collaborative care model is that hospitals that run them aren’t able to control all the variables associated with the cost of providing them.

The hope is that by spending more up front to identify and treat high-risk behavioral health patients, they won’t need readmission; but if the appropriate follow-up care can’t be found on the outpatient side, they could still end up back in the hospital, driving up readmission rates and possibly lengths of stay.

To address such contingencies, Hopkins has participated in state-sponsored partnerships for improving community care and is using monies from accountable care organization funding to create bridge services. The hospital system also has 14 primary care practices that have embedded psychiatric services, and the plan is to create a team to care for more complicated patients who need care 60-90 days after discharge.

For Dr. Lyketsos, however, fixing what he says is a broken mental health system isn’t up to the hospital alone. “We’re not going to be able to bring about real change without working with our legislators and our payers. It’s a complex problem that needs a complex solution. But there is a commonality of mind that we need to fix things, that patients need better care – and that this is a good place to start.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CORRECTION, 6/28/16: A previous version of this article misstated Dr. Hochang B. Lee's name.

BALTIMORE – A team of physicians and mental health experts at Johns Hopkins Hospital is trying something new: combining mental health services with medical ones. Hospital leadership hopes the experiment will pay off in shorter lengths of stay, lower readmission rates, and better overall patient care.

“We’re still collecting that data,” Melissa Richardson, the hospital’s director of care coordination, said in an interview. “We also will look at the impact on staffing ratios on the units. For example, has the number of patient observers gone down? Has the overall severity of certain cases on the unit been reduced by embedding mental health workers there?”

The medical-surgical mental health team debuted in April, and is separate from the hospital’s other psychiatric services. Comprised of a social worker, a nurse practitioner, a nurse care coordinator, and an attending psychiatrist, the team typically works a regular day shift, beginning each morning with patient chart reviews prepared by medical-surgical personnel. They discuss which patients will be seen by whom, since all team members are trained to do psychiatric evaluations.

Not all medical patients require psychiatric care, but according to the program’s clinical director and attending psychiatrist, Dr. Patrick T. Triplett, up to 38% of all medical admissions have a psychiatric comorbidity. Addressing those comorbidities while patients are in the hospital often leads to improved outcomes.

The team’s social worker connects patients with the appropriate outpatient mental health services in the community, and the team’s nurse care coordinator arranges any necessary transfers from the medical-surgical units to the inpatient psychiatric unit. Dr. Triplett and the psychiatric nurse practitioner are the only two team members who can diagnose and prescribe. Dr. Triplett’s time is billed as consultation services, and the hospital absorbs the cost of the rest of the team, according to Ms. Richardson.

‘Complex medically ill’ patients

As some procedures and medical treatments have shifted to the outpatient setting in recent years, and joint replacements or acute conditions such as myocardial infarctions can be managed successfully in shorter stays, more complicated patients, such as joint replacement patients who develop delirium, have been left on the medical-surgical unit, said Dr. Constantine G. Lyketsos, the Elizabeth Plank Althouse Professor at Johns Hopkins Bayview, Baltimore.

“Also, these days, up to 20% of our admissions are linked to opioids. Then, there are the chronically mentally ill. They tend to be a population with high rates of obesity, smoking, and diabetes, so they end up in the hospital with higher-level, more complicated conditions, that because of the disintegration of the mental health system, receive neither good psychiatric nor outpatient medical care,” Dr. Lyketsos, also chief of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Bayview, said in an interview.

This surge in the number of complex medically ill patients has led to a growing number of hospitals nationwide calling upon psychiatrists for help in improving overall care. Hopkins is only the latest to join the ranks of other institutions such as Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn (N.Y.), Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., and New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City.

The progenitor of this collaborative inpatient care model is Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital. The behavioral intervention team (BIT) at Yale New Haven includes nurses, social workers, and psychiatrists who proactively screen for and address behavioral barriers to care for medical patients with a co-occurring mental illness, said Dr. Hochang B. Lee, one of the psychiatrists who helped created the model in 2008. Dr. Lee is Yale’s psychological medicine section chief and director of the school’s Psychological Medicine Research Center. He also is an associate professor of psychiatry and an associate clinical professor of nursing.

“The goal was to create a proactive model of care, not the reactive one that is traditional consultation-liaison psychiatry,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “Before the BIT model, medical teams often missed behavioral issues or made consultation requests too late in the course of hospitalization to avoid psychiatric crisis.”

LOS, costs reduced

A study

“The hospital is not making money off of us, but they’re losing less money because of us. That’s good!” Dr. Philip R. Muskin, chief of consultation-liaison psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia, said in an interview.

Patients at New York Presbyterian have been comanaged since 2004 when, according to Dr. Muskin, a donor gift specifically intended for such a purpose was matched by the hospital’s department of medicine. The unspent money was enough to cover the cost of a consultation-liaison psychiatrist to round full time as an attending with the medical team.

“We were lucky at NYPCH, because someone gave us the gift to hire a full-time psychiatrist we could embed into the medical team,” Dr. Muskin said. “But there is no one right way to deliver collaborative care in the inpatient setting.”

The NYPCH program has grown to include a second full-time and one part-time psychiatrist, serving about half of all medical services at the campus, with plans to hire more. There is also a social worker to assist with outplacement services. Dr. Muskin said he is currently looking to hire a psychiatric nurse practitioner.

‘Nurses love us’

Restoration of staff morale is another benefit to this kind of practice, according to Maureen Lewis, an accredited psychiatric nurse practitioner who is part of the Hopkins integrated team.

“Med-surge nurses love us. Patients who come in with an overdose or who have any psychiatric conditions but need to have their medical comorbidities dealt with first, they are at their sickest with their psychiatric illnesses when they first arrive,” Ms. Lewis said. “It’s the med-surge nurses who have to care for them, but it’s not their comfort zone or their skill set. They like that we are helping them manage the patient.”

A decline in the number of assaults on the nursing staff also has been recorded since the Hopkins program began, Dr. Lyketsos said.

The psychiatrists themselves tend to be happier, too. “Knowing the cases before you even walk up on the unit is a huge benefit,” Dr. Triplett said. “To have to dive into an emergency all the time is just exhausting. It changes your relationship with the patient. When you’re not in that crisis mode, the patient isn’t a ‘problem’ anymore.”

A formal assessment of the entire medical-surgical staff satisfaction involved in the Hopkins program also is underway, said Ms. Richardson, the director of care coordination.

Having psychiatrists at the fore of this evolution in care provides more opportunities for training, too.

The comanagement model gives medical staff a chance to learn more not just about the direct care of complex behaviorally disordered patients, but also to understand their own emotions and states of mind as they interact with these patients. The teaching happens naturally as the team discusses patients while making rounds, Dr. Muskin said. “That’s really an integral part of what consult-liaison psychiatry is supposed to be about, anyway.”

By helping the medical staff reflect on their experiences, Dr. Muskin said, psychiatrists are helping to change the culture of inpatient medicine. “Once you change the culture, if you keep the things that brought it about in place, it doesn’t change back.”

Creating bridge services

A problem with this kind of inpatient collaborative care model is that hospitals that run them aren’t able to control all the variables associated with the cost of providing them.

The hope is that by spending more up front to identify and treat high-risk behavioral health patients, they won’t need readmission; but if the appropriate follow-up care can’t be found on the outpatient side, they could still end up back in the hospital, driving up readmission rates and possibly lengths of stay.

To address such contingencies, Hopkins has participated in state-sponsored partnerships for improving community care and is using monies from accountable care organization funding to create bridge services. The hospital system also has 14 primary care practices that have embedded psychiatric services, and the plan is to create a team to care for more complicated patients who need care 60-90 days after discharge.

For Dr. Lyketsos, however, fixing what he says is a broken mental health system isn’t up to the hospital alone. “We’re not going to be able to bring about real change without working with our legislators and our payers. It’s a complex problem that needs a complex solution. But there is a commonality of mind that we need to fix things, that patients need better care – and that this is a good place to start.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CORRECTION, 6/28/16: A previous version of this article misstated Dr. Hochang B. Lee's name.

Unanimous vote sends mental health reform to House floor

The much contested Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act is at last headed for the House floor. The bipartisan bill was passed 53-0 by members of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

“The 53-0 vote marks another important milestone to delivering meaningful reforms to families in mental health crisis. Those suffering from mental illness need the attention of this Congress, and I hope the House will swiftly follow our lead,” Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), chairman of the committee, said in a statement.

Much of the debate on H.R. 2646, introduced last year by Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.), has centered on its call for relaxation of HIPAA rules, tougher assisted outpatient treatment requirements, and changes to the structure of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

The bill originally called for relaxing HIPAA somewhat so that parents and caregivers could receive patient care information, excluding psychotherapy notes. Instead, the bill as passed by the committee calls upon the Department of Health and Human Services to clarify the law and better educate medical personnel as to what is and isn’t appropriate to share, particularly when a patient is considered incapacitated.

Rep. Murphy, who is a clinical child psychologist, also wanted to more widely implement assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) for patients with serious mental illness. In the end, the committee approved a 2-year extension for AOT block grant funding into 2020, at a cost of an additional $5 million.

The bill as passed by the committee entrusts the administration of SAMHSA to a cabinet-level appointee and calls for that individual to be a physician or clinical psychologist. Various checks and balances have also been added to ensure that if the bill becomes law, SAMHSA will focus on evidence-based practices.

The bill (which greatly mirrors the U.S. Senate bill the Mental Health Reform Act of 2016, S. 2680) now heads to the House floor where Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) has pledged to give it priority this summer.

“Here and now this committee jointly proclaims that the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness must come out of the shadows. We declare a new dawn of hope for the care of those with mental illness and we pledge our unwavering commitment to continued work to bring help and hope in the future,” Rep. Murphy said in a statement.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The much contested Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act is at last headed for the House floor. The bipartisan bill was passed 53-0 by members of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

“The 53-0 vote marks another important milestone to delivering meaningful reforms to families in mental health crisis. Those suffering from mental illness need the attention of this Congress, and I hope the House will swiftly follow our lead,” Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), chairman of the committee, said in a statement.

Much of the debate on H.R. 2646, introduced last year by Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.), has centered on its call for relaxation of HIPAA rules, tougher assisted outpatient treatment requirements, and changes to the structure of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

The bill originally called for relaxing HIPAA somewhat so that parents and caregivers could receive patient care information, excluding psychotherapy notes. Instead, the bill as passed by the committee calls upon the Department of Health and Human Services to clarify the law and better educate medical personnel as to what is and isn’t appropriate to share, particularly when a patient is considered incapacitated.

Rep. Murphy, who is a clinical child psychologist, also wanted to more widely implement assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) for patients with serious mental illness. In the end, the committee approved a 2-year extension for AOT block grant funding into 2020, at a cost of an additional $5 million.

The bill as passed by the committee entrusts the administration of SAMHSA to a cabinet-level appointee and calls for that individual to be a physician or clinical psychologist. Various checks and balances have also been added to ensure that if the bill becomes law, SAMHSA will focus on evidence-based practices.

The bill (which greatly mirrors the U.S. Senate bill the Mental Health Reform Act of 2016, S. 2680) now heads to the House floor where Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) has pledged to give it priority this summer.

“Here and now this committee jointly proclaims that the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness must come out of the shadows. We declare a new dawn of hope for the care of those with mental illness and we pledge our unwavering commitment to continued work to bring help and hope in the future,” Rep. Murphy said in a statement.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The much contested Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act is at last headed for the House floor. The bipartisan bill was passed 53-0 by members of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

“The 53-0 vote marks another important milestone to delivering meaningful reforms to families in mental health crisis. Those suffering from mental illness need the attention of this Congress, and I hope the House will swiftly follow our lead,” Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), chairman of the committee, said in a statement.

Much of the debate on H.R. 2646, introduced last year by Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.), has centered on its call for relaxation of HIPAA rules, tougher assisted outpatient treatment requirements, and changes to the structure of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

The bill originally called for relaxing HIPAA somewhat so that parents and caregivers could receive patient care information, excluding psychotherapy notes. Instead, the bill as passed by the committee calls upon the Department of Health and Human Services to clarify the law and better educate medical personnel as to what is and isn’t appropriate to share, particularly when a patient is considered incapacitated.

Rep. Murphy, who is a clinical child psychologist, also wanted to more widely implement assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) for patients with serious mental illness. In the end, the committee approved a 2-year extension for AOT block grant funding into 2020, at a cost of an additional $5 million.

The bill as passed by the committee entrusts the administration of SAMHSA to a cabinet-level appointee and calls for that individual to be a physician or clinical psychologist. Various checks and balances have also been added to ensure that if the bill becomes law, SAMHSA will focus on evidence-based practices.

The bill (which greatly mirrors the U.S. Senate bill the Mental Health Reform Act of 2016, S. 2680) now heads to the House floor where Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) has pledged to give it priority this summer.

“Here and now this committee jointly proclaims that the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness must come out of the shadows. We declare a new dawn of hope for the care of those with mental illness and we pledge our unwavering commitment to continued work to bring help and hope in the future,” Rep. Murphy said in a statement.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Few adverse events linked to flibanserin with self-reported alcohol use

A small number of women reported adverse events related to hypotension and syncope while taking flibanserin and drinking alcohol, an analysis of data from five phase III trials has shown.

Flibanserin is the first drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for low female sexual desire in premenopausal women. When the FDA approved flibanserin in August 2015, the agency gave it a boxed warning contraindicating alcohol use with the drug because of a risk of severe hypotension and syncope. The FDA also directed Sprout Pharmaceuticals, who markets the drug as Addyi, to conduct postmarket studies into the relationship between hypotension- and syncope-related events concurrent with alcohol use.

Flibanserin is metabolized through the CYP3A4 system, creating the potential for drug-drug and drug-alcohol interactions. A mixed agonist/antagonist for serotonin and dopamine receptors, flibanserin is taken orally at bedtime on a long-term basis, typically in doses of 100 mg.

Events related to hypotension and syncope include circulatory collapse, hypotension, loss of consciousness, orthostatic hypotension, syncope, vasovagal syncope, and light-headedness.

The industry-funded post hoc analysis included data from five phase III randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled studies of 3,448 premenopausal women. Of the 1,543 taking flibanserin 100 mg at bedtime for up to 24 weeks, 898 reported alcohol use at baseline. Six of these women reported a total of eight adverse events related to hypotension and syncope. In addition, two women who took flibanserin and reported they did not use alcohol had syncope-related events.

Of the 1,905 women taking a placebo, 1,212 reported alcohol use at baseline. Four of these women reported hypotension- and syncope-related adverse events. One woman in the placebo group who reported no alcohol use had two syncope-related adverse events.

Discontinuation rates due to hypotension or syncope among flibanserin users were virtually the same among those who did and did not report alcohol use: 1.8% vs. 1.7%. Among women in the placebo group, those who did not use alcohol had a discontinuation rate of 0.3%, while alcohol users who received placebo had a discontinuation rate of 0.15%.

“It is interesting to note that of the six alcohol users who took flibanserin and had syncopal or hypotensive episodes, four of them continued dosing and completed the study,” Dr. Stuart Apfel, the study’s lead author, said in an interview. “Of the two who did discontinue, one did so because of the syncopal event; the other did so because of somnolence, which is the most common side effect whether one takes alcohol with it or not.”

Dr. Apfel and his colleagues acknowledged that the analysis was limited by the fact that alcohol use was based on self-reports, rather than direct measurement. However, when asked if the drug is safe even if a woman has used alcohol more than she has reported, Dr. Apfel said he personally believes it’s safe, based on the data.

Although there is an increased risk of hypotension and/or syncope with the combination of alcohol use and flibanserin, Dr. Apfel said the risk “appears to be very small, and only moderately higher than [for] those who did not take alcohol.” But the FDA appears to disagree, and after reviewing these same data, required that alcohol use be listed as a contraindication, he added. “I personally don’t think the data indicates that there is a major risk, but it is obviously open to interpretation.”

Dr. Apfel is a consultant to Sprout Pharmaceuticals and Valeant Pharmaceuticals. The studies were supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Other support was provided by Valeant Pharmaceuticals. The data were presented at the 2016 American Urological Association annual meeting in San Diego.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Dr. Apfel et al.’s study reports on the hypotension and syncopal side effects of flibanserin in women who drank alcohol. Some of the women were concerned with using the medication after the FDA attached a boxed warning at the time of its approval, contraindicating alcohol use. The study covers the five registration phase III flibanserin trials, and shows a very low percentage of side effects, despite the use of alcohol.

Only 6 of 898 premenopausal women (0.7%) taking flibanserin as directed for 24 weeks, but who also used alcohol, reported hypotension or syncope. Comparatively, only 4 of 1,212 subjects (0.3%) taking a placebo and alcohol had similar side effects. Discontinuation rates were similarly low in both groups. Whether the prevalence of side effects and discontinuation rates are low enough for the FDA to consider lifting the boxed warning remains to be seen.

|

Dr. Patrick J. Woodman |

The FDA required the manufacturer to perform postmarket surveillance studies to monitor these and other adverse events (AEs). Currently, Sprout Pharmaceuticals requires physicians to complete an educational program, take a quiz, and register as a flibanserin provider. The education is specifically geared toward the potential hypotension and syncope AEs when patients use alcohol.

Taken alone, the results seem to indicate that there is twice as much hypotension and syncope as a result of drinking alcohol during treatment, and that twice as many subjects discontinue the medication as a result. However, the absolute effect of alcohol on flibanserin-treated patients is quite small (0.3% AEs and a 0.15% discontinuation rate).

These findings are encouraging since nearly 60% of U.S. women admit to having drunk alcohol within the last month. It is not reasonable to expect a patient to never drink alcohol during a course of her treatment, especially if the hypoactive sexual desire is long-standing or recalcitrant.

Dr. Apfel’s team has given prescribers some much-needed information that can be utilized for counseling patients interested in treatment. It appears that incidental alcohol use during flibanserin treatment may be relatively safe. But if hypotension or syncope occurs at a certain time or in certain situations, these AEs can be dangerous. It behooves us to wait until the postmarket surveillance studies are performed and reported before giving our flibanserin patients the “all clear” to have that glass of wine or beer.

Dr. Patrick J. Woodman is a urogynecologist and obstetrics and gynecology residency program director at St. John Macomb-Oakland Hospital in Warren, Mich. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Apfel et al.’s study reports on the hypotension and syncopal side effects of flibanserin in women who drank alcohol. Some of the women were concerned with using the medication after the FDA attached a boxed warning at the time of its approval, contraindicating alcohol use. The study covers the five registration phase III flibanserin trials, and shows a very low percentage of side effects, despite the use of alcohol.

Only 6 of 898 premenopausal women (0.7%) taking flibanserin as directed for 24 weeks, but who also used alcohol, reported hypotension or syncope. Comparatively, only 4 of 1,212 subjects (0.3%) taking a placebo and alcohol had similar side effects. Discontinuation rates were similarly low in both groups. Whether the prevalence of side effects and discontinuation rates are low enough for the FDA to consider lifting the boxed warning remains to be seen.

|

Dr. Patrick J. Woodman |

The FDA required the manufacturer to perform postmarket surveillance studies to monitor these and other adverse events (AEs). Currently, Sprout Pharmaceuticals requires physicians to complete an educational program, take a quiz, and register as a flibanserin provider. The education is specifically geared toward the potential hypotension and syncope AEs when patients use alcohol.

Taken alone, the results seem to indicate that there is twice as much hypotension and syncope as a result of drinking alcohol during treatment, and that twice as many subjects discontinue the medication as a result. However, the absolute effect of alcohol on flibanserin-treated patients is quite small (0.3% AEs and a 0.15% discontinuation rate).

These findings are encouraging since nearly 60% of U.S. women admit to having drunk alcohol within the last month. It is not reasonable to expect a patient to never drink alcohol during a course of her treatment, especially if the hypoactive sexual desire is long-standing or recalcitrant.

Dr. Apfel’s team has given prescribers some much-needed information that can be utilized for counseling patients interested in treatment. It appears that incidental alcohol use during flibanserin treatment may be relatively safe. But if hypotension or syncope occurs at a certain time or in certain situations, these AEs can be dangerous. It behooves us to wait until the postmarket surveillance studies are performed and reported before giving our flibanserin patients the “all clear” to have that glass of wine or beer.

Dr. Patrick J. Woodman is a urogynecologist and obstetrics and gynecology residency program director at St. John Macomb-Oakland Hospital in Warren, Mich. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Apfel et al.’s study reports on the hypotension and syncopal side effects of flibanserin in women who drank alcohol. Some of the women were concerned with using the medication after the FDA attached a boxed warning at the time of its approval, contraindicating alcohol use. The study covers the five registration phase III flibanserin trials, and shows a very low percentage of side effects, despite the use of alcohol.

Only 6 of 898 premenopausal women (0.7%) taking flibanserin as directed for 24 weeks, but who also used alcohol, reported hypotension or syncope. Comparatively, only 4 of 1,212 subjects (0.3%) taking a placebo and alcohol had similar side effects. Discontinuation rates were similarly low in both groups. Whether the prevalence of side effects and discontinuation rates are low enough for the FDA to consider lifting the boxed warning remains to be seen.

|

Dr. Patrick J. Woodman |

The FDA required the manufacturer to perform postmarket surveillance studies to monitor these and other adverse events (AEs). Currently, Sprout Pharmaceuticals requires physicians to complete an educational program, take a quiz, and register as a flibanserin provider. The education is specifically geared toward the potential hypotension and syncope AEs when patients use alcohol.

Taken alone, the results seem to indicate that there is twice as much hypotension and syncope as a result of drinking alcohol during treatment, and that twice as many subjects discontinue the medication as a result. However, the absolute effect of alcohol on flibanserin-treated patients is quite small (0.3% AEs and a 0.15% discontinuation rate).

These findings are encouraging since nearly 60% of U.S. women admit to having drunk alcohol within the last month. It is not reasonable to expect a patient to never drink alcohol during a course of her treatment, especially if the hypoactive sexual desire is long-standing or recalcitrant.

Dr. Apfel’s team has given prescribers some much-needed information that can be utilized for counseling patients interested in treatment. It appears that incidental alcohol use during flibanserin treatment may be relatively safe. But if hypotension or syncope occurs at a certain time or in certain situations, these AEs can be dangerous. It behooves us to wait until the postmarket surveillance studies are performed and reported before giving our flibanserin patients the “all clear” to have that glass of wine or beer.

Dr. Patrick J. Woodman is a urogynecologist and obstetrics and gynecology residency program director at St. John Macomb-Oakland Hospital in Warren, Mich. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A small number of women reported adverse events related to hypotension and syncope while taking flibanserin and drinking alcohol, an analysis of data from five phase III trials has shown.

Flibanserin is the first drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for low female sexual desire in premenopausal women. When the FDA approved flibanserin in August 2015, the agency gave it a boxed warning contraindicating alcohol use with the drug because of a risk of severe hypotension and syncope. The FDA also directed Sprout Pharmaceuticals, who markets the drug as Addyi, to conduct postmarket studies into the relationship between hypotension- and syncope-related events concurrent with alcohol use.

Flibanserin is metabolized through the CYP3A4 system, creating the potential for drug-drug and drug-alcohol interactions. A mixed agonist/antagonist for serotonin and dopamine receptors, flibanserin is taken orally at bedtime on a long-term basis, typically in doses of 100 mg.

Events related to hypotension and syncope include circulatory collapse, hypotension, loss of consciousness, orthostatic hypotension, syncope, vasovagal syncope, and light-headedness.

The industry-funded post hoc analysis included data from five phase III randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled studies of 3,448 premenopausal women. Of the 1,543 taking flibanserin 100 mg at bedtime for up to 24 weeks, 898 reported alcohol use at baseline. Six of these women reported a total of eight adverse events related to hypotension and syncope. In addition, two women who took flibanserin and reported they did not use alcohol had syncope-related events.

Of the 1,905 women taking a placebo, 1,212 reported alcohol use at baseline. Four of these women reported hypotension- and syncope-related adverse events. One woman in the placebo group who reported no alcohol use had two syncope-related adverse events.