User login

Specific brain damage links hypertension to cognitive impairment

Researchers have identified specific regions of the brain that appear to be damaged by high blood pressure. The finding may explain the link between hypertension and cognitive impairment.

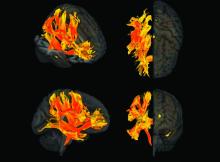

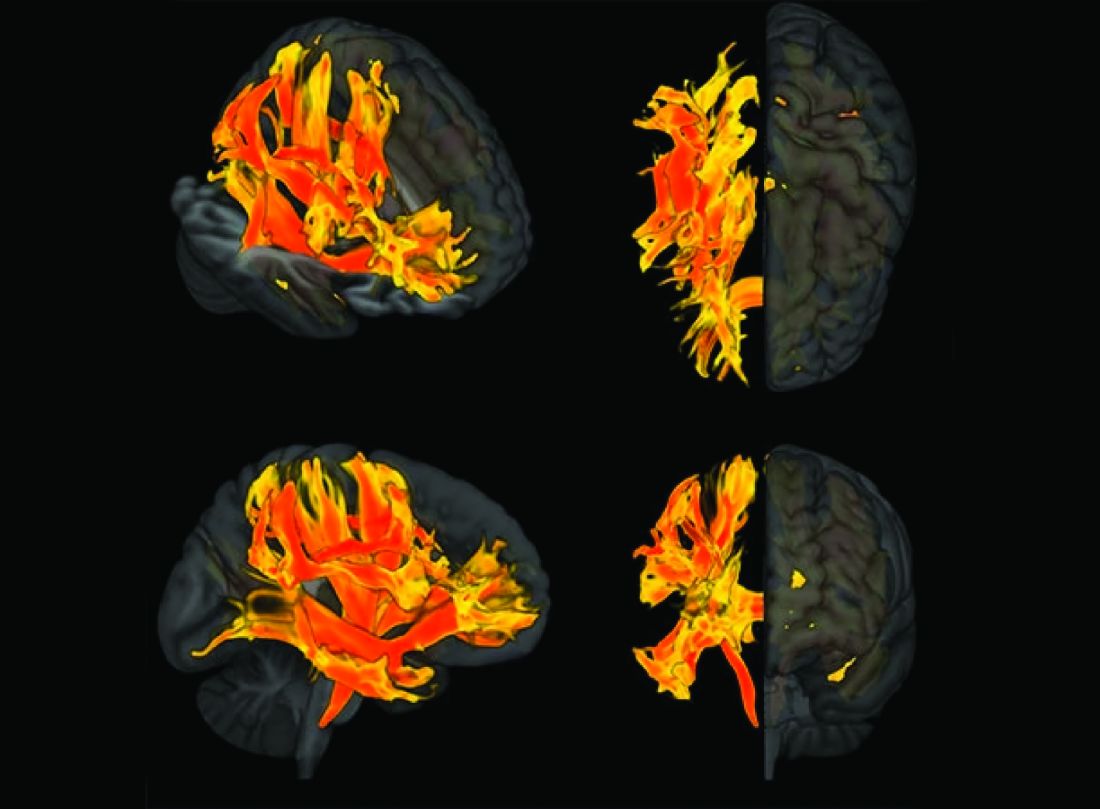

They used genetic information from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and MRI scans of the brain to study the relationship between hypertension, changes in brain structures, and cognitive impairment. Using Mendelian randomization techniques, they identified nine brain structures related to cognitive impairment that are affected by blood pressure.

“We knew before that raised blood pressure was related to changes in the brain, but our research has narrowed down the changes to those that appear to be potentially causally related to cognitive impairment,” senior author Tomasz Guzik, professor of cardiovascular medicine, at the University of Edinburgh and of the Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, told this news organization.

“Our study confirms a potentially causal relationship between raised blood pressure and cognitive impairment, emphasizing the importance of preventing and treating hypertension,” Prof. Guzik noted.

“But it also identifies the brain culprits of this relationship,” he added.

In the future, it may be possible to assess these nine brain structures in people with high blood pressure to identify those at increased risk of developing cognitive impairment, he said. “These patients may need more intensive care for their blood pressure. We can also investigate these brain structures for potential signaling pathways and molecular changes to see if we can find new targets for treatment to prevent cognitive impairment.”

For this report, the investigators married together different research datasets to identify brain structures potentially responsible for the effects of blood pressure on cognitive function, using results from previous GWASs and observational data from 39,000 people in the UK Biobank registry for whom brain MRI data were available.

First, they mapped brain structures potentially influenced by blood pressure in midlife using MRI scans from people in the UK Biobank registry. Then they examined the relationship between blood pressure and cognitive function in the UK Biobank registry. Next, of the brain structures affected by blood pressure, they identified those that are causally linked to cognitive impairment.

This was possible thanks to genetic markers coding for increased blood pressure, brain structure imaging phenotypes, and those coding for cognitive impairment that could be used in Mendelian randomization studies.

“We looked at 3935 brain magnetic resonance imaging–derived phenotypes in the brain and cognitive function defined by fluid intelligence score to identify genetically predicted causal relationships,” Prof. Guzik said.

They identified 200 brain structures that were causally affected by systolic blood pressure. Of these, nine were also causally related to cognitive impairment. The results were validated in a second prospective cohort of patients with hypertension.

“Some of these structures, including putamen and the white matter regions spanning between the anterior corona radiata, anterior thalamic radiation, and anterior limb of the internal capsule, may represent the target brain regions at which systolic blood pressure acts on cognitive function,” the authors comment.

In an accompanying editorial, Ernesto Schiffrin, MD, and James Engert, PhD, McGill University, Montreal, say that further mechanistic studies of the effects of blood pressure on cognitive function are required to determine precise causal pathways and the roles of relevant brain regions.

“Eventually, biomarkers could be developed to inform antihypertensive trials. Whether clinical trials targeting the specific brain structures will be feasible or if specific antihypertensives could be found that target specific structures remains to be demonstrated,” they write.

“Thus, these new studies could lead to an understanding of the signaling pathways that explain how these structures relate vascular damage to cognitive impairment in hypertension, and contribute to the development of novel interventions to more successfully address the scourge of cognitive decline and dementia in the future,” the editorialists conclude.

The study was funded by the European Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the Italian Ministry of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers have identified specific regions of the brain that appear to be damaged by high blood pressure. The finding may explain the link between hypertension and cognitive impairment.

They used genetic information from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and MRI scans of the brain to study the relationship between hypertension, changes in brain structures, and cognitive impairment. Using Mendelian randomization techniques, they identified nine brain structures related to cognitive impairment that are affected by blood pressure.

“We knew before that raised blood pressure was related to changes in the brain, but our research has narrowed down the changes to those that appear to be potentially causally related to cognitive impairment,” senior author Tomasz Guzik, professor of cardiovascular medicine, at the University of Edinburgh and of the Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, told this news organization.

“Our study confirms a potentially causal relationship between raised blood pressure and cognitive impairment, emphasizing the importance of preventing and treating hypertension,” Prof. Guzik noted.

“But it also identifies the brain culprits of this relationship,” he added.

In the future, it may be possible to assess these nine brain structures in people with high blood pressure to identify those at increased risk of developing cognitive impairment, he said. “These patients may need more intensive care for their blood pressure. We can also investigate these brain structures for potential signaling pathways and molecular changes to see if we can find new targets for treatment to prevent cognitive impairment.”

For this report, the investigators married together different research datasets to identify brain structures potentially responsible for the effects of blood pressure on cognitive function, using results from previous GWASs and observational data from 39,000 people in the UK Biobank registry for whom brain MRI data were available.

First, they mapped brain structures potentially influenced by blood pressure in midlife using MRI scans from people in the UK Biobank registry. Then they examined the relationship between blood pressure and cognitive function in the UK Biobank registry. Next, of the brain structures affected by blood pressure, they identified those that are causally linked to cognitive impairment.

This was possible thanks to genetic markers coding for increased blood pressure, brain structure imaging phenotypes, and those coding for cognitive impairment that could be used in Mendelian randomization studies.

“We looked at 3935 brain magnetic resonance imaging–derived phenotypes in the brain and cognitive function defined by fluid intelligence score to identify genetically predicted causal relationships,” Prof. Guzik said.

They identified 200 brain structures that were causally affected by systolic blood pressure. Of these, nine were also causally related to cognitive impairment. The results were validated in a second prospective cohort of patients with hypertension.

“Some of these structures, including putamen and the white matter regions spanning between the anterior corona radiata, anterior thalamic radiation, and anterior limb of the internal capsule, may represent the target brain regions at which systolic blood pressure acts on cognitive function,” the authors comment.

In an accompanying editorial, Ernesto Schiffrin, MD, and James Engert, PhD, McGill University, Montreal, say that further mechanistic studies of the effects of blood pressure on cognitive function are required to determine precise causal pathways and the roles of relevant brain regions.

“Eventually, biomarkers could be developed to inform antihypertensive trials. Whether clinical trials targeting the specific brain structures will be feasible or if specific antihypertensives could be found that target specific structures remains to be demonstrated,” they write.

“Thus, these new studies could lead to an understanding of the signaling pathways that explain how these structures relate vascular damage to cognitive impairment in hypertension, and contribute to the development of novel interventions to more successfully address the scourge of cognitive decline and dementia in the future,” the editorialists conclude.

The study was funded by the European Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the Italian Ministry of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers have identified specific regions of the brain that appear to be damaged by high blood pressure. The finding may explain the link between hypertension and cognitive impairment.

They used genetic information from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and MRI scans of the brain to study the relationship between hypertension, changes in brain structures, and cognitive impairment. Using Mendelian randomization techniques, they identified nine brain structures related to cognitive impairment that are affected by blood pressure.

“We knew before that raised blood pressure was related to changes in the brain, but our research has narrowed down the changes to those that appear to be potentially causally related to cognitive impairment,” senior author Tomasz Guzik, professor of cardiovascular medicine, at the University of Edinburgh and of the Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, told this news organization.

“Our study confirms a potentially causal relationship between raised blood pressure and cognitive impairment, emphasizing the importance of preventing and treating hypertension,” Prof. Guzik noted.

“But it also identifies the brain culprits of this relationship,” he added.

In the future, it may be possible to assess these nine brain structures in people with high blood pressure to identify those at increased risk of developing cognitive impairment, he said. “These patients may need more intensive care for their blood pressure. We can also investigate these brain structures for potential signaling pathways and molecular changes to see if we can find new targets for treatment to prevent cognitive impairment.”

For this report, the investigators married together different research datasets to identify brain structures potentially responsible for the effects of blood pressure on cognitive function, using results from previous GWASs and observational data from 39,000 people in the UK Biobank registry for whom brain MRI data were available.

First, they mapped brain structures potentially influenced by blood pressure in midlife using MRI scans from people in the UK Biobank registry. Then they examined the relationship between blood pressure and cognitive function in the UK Biobank registry. Next, of the brain structures affected by blood pressure, they identified those that are causally linked to cognitive impairment.

This was possible thanks to genetic markers coding for increased blood pressure, brain structure imaging phenotypes, and those coding for cognitive impairment that could be used in Mendelian randomization studies.

“We looked at 3935 brain magnetic resonance imaging–derived phenotypes in the brain and cognitive function defined by fluid intelligence score to identify genetically predicted causal relationships,” Prof. Guzik said.

They identified 200 brain structures that were causally affected by systolic blood pressure. Of these, nine were also causally related to cognitive impairment. The results were validated in a second prospective cohort of patients with hypertension.

“Some of these structures, including putamen and the white matter regions spanning between the anterior corona radiata, anterior thalamic radiation, and anterior limb of the internal capsule, may represent the target brain regions at which systolic blood pressure acts on cognitive function,” the authors comment.

In an accompanying editorial, Ernesto Schiffrin, MD, and James Engert, PhD, McGill University, Montreal, say that further mechanistic studies of the effects of blood pressure on cognitive function are required to determine precise causal pathways and the roles of relevant brain regions.

“Eventually, biomarkers could be developed to inform antihypertensive trials. Whether clinical trials targeting the specific brain structures will be feasible or if specific antihypertensives could be found that target specific structures remains to be demonstrated,” they write.

“Thus, these new studies could lead to an understanding of the signaling pathways that explain how these structures relate vascular damage to cognitive impairment in hypertension, and contribute to the development of novel interventions to more successfully address the scourge of cognitive decline and dementia in the future,” the editorialists conclude.

The study was funded by the European Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the Italian Ministry of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Does new heart transplant method challenge definition of death?

The relatively recent innovation of heart transplantation after circulatory death of the donor is increasing the number of donor hearts available and leading to many more lives on the heart transplant waiting list being saved. Experts agree it’s a major and very welcome advance in medicine.

However, some of the processes involved in one approach to donation after circulatory death has raised ethical concerns and questions about whether they violate the “dead donor rule” – a principle that requires patients be declared dead before removal of life-sustaining organs for transplant.

Experts in the fields of transplantation and medical ethics have yet to reach consensus, causing problems for the transplant community, who worry that this could cause a loss of confidence in the entire transplant process.

A new pathway for heart transplantation

The traditional approach to transplantation is to retrieve organs from a donor who has been declared brain dead, known as “donation after brain death (DBD).” These patients have usually suffered a catastrophic brain injury but survived to get to intensive care.

As the brain swells because of injury, it becomes evident that all brain function is lost, and the patient is declared brain dead. However, breathing is maintained by the ventilator and the heart is still beating. Because the organs are being oxygenated, there is no immediate rush to retrieve the organs and the heart can be evaluated for its suitability for transplant in a calm and methodical way before it is removed.

However, there is a massive shortage of organs, especially hearts, partially because of the limited number of donors who are declared brain dead in that setting.

In recent years, another pathway for organ transplantation has become available: “donation after circulatory death (DCD).” These patients also have suffered a catastrophic brain injury considered to be nonsurvivable, but unlike the DBD situation, the brain still has some function, so the patient does not meet the criteria for brain death.

Still, because the patient is considered to have no chance of a meaningful recovery, the family often recognizes the futility of treatment and agrees to the withdrawal of life support. When this happens, the heart normally stops beating after a period of time. There is then a “stand-off time” – normally 5 minutes – after which death is declared and the organs can be removed.

The difficulty with this approach, however, is that because the heart has been stopped, it has been deprived of oxygen, potentially causing injury. While DCD has been practiced for several years to retrieve organs such as the kidney, liver, lungs, and pancreas, the heart is more difficult as it is more susceptible to oxygen deprivation. And for the heart to be assessed for transplant suitability, it should ideally be beating, so it has to be reperfused and restarted quickly after death has been declared.

For many years it was thought the oxygen deprivation that occurs after circulatory death would be too much to provide a functional organ. But researchers in the United Kingdom and Australia developed techniques to overcome this problem, and early DCD heart transplants took place in 2014 in Australia, and in 2015 in the United Kingdom.

Heart transplantation after circulatory death has now become a routine part of the transplant program in many countries, including the United States, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Austria.

In the United States, 348 DCD heart transplants were performed in 2022, with numbers expected to reach 700 to 800 this year as more centers come online.

It is expected that most countries with heart transplant programs will follow suit and the number of donor hearts will increase by up to 30% worldwide because of DCD.

Currently, there are about 8,000 heart transplants worldwide each year and with DCD this could rise to about 10,000, potentially an extra 2,000 lives saved each year, experts estimate.

Two different approaches to DCD heart transplantation have been developed.

The direct procurement approach

The Australian group, based at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, developed a technique referred to as “direct procurement”: after the standoff period and declaration of circulatory death, the chest is opened, and the heart is removed. New technology, the Organ Care System (OCS) heart box (Transmedics), is then used to reperfuse and restart the heart outside the body so its suitability for transplant can be assessed.

The heart is kept perfused and beating in the OCS box while it is being transported to the recipient. This has enabled longer transit times than the traditional way of transporting the nonbeating heart on ice.

Peter MacDonald, MD, PhD, from the St Vincent’s group that developed this approach, said, “Most people thought a heart from a DCD donor would not survive transport – that the injury to the heart from the combination of life support withdrawal, stand-off time, and cold storage would be too much. But we modeled the process in the lab and were able to show that we were able to get the heart beating again after withdrawal of life support.”

Dr. McDonald noted that “the recipient of their first human DCD heart transplant using this machine in 2014 is still alive and well.” The Australian group has now done 85 of these DCD heart transplants, and they have increased the number of heart transplant procedures at St. Vincent’s Hospital by 25%.

Normothermic regional perfusion (NRP)

The U.K. group, based at the Royal Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, England, developed a different approach to DCD: After the standoff period and the declaration of circulatory death, the donor is connected to a heart/lung machine using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) so that the heart is perfused and starts beating again inside the body. This approach is known as normothermic regional perfusion (NRP).

Marius Berman, MD, surgical lead for Transplantation and Mechanical Circulatory Support at Papworth, explained that the NRP approach allows the heart to be perfused and restarted faster than direct procurement, resulting in a shorter ischemic time. The heart can be evaluated thoroughly for suitability for transplantation in situ before committing to transplantation, and because the heart is less damaged, it can be transported on ice without use of the OCS box.

“DCD is more complicated than DBD, because the heart has stopped and has to be restarted. Retrieval teams have to be very experienced,” Dr. Berman noted. “This is more of an issue for the direct procurement approach, where the chest has to be opened and the heart retrieved as fast as possible. It is a rush. The longer time without the heart being perfused correlates to an increased incidence of primary graft dysfunction. With NRP, we can get the heart started again more quickly, which is crucial.”

Stephen Large, MBBS, another cardiothoracic surgeon with the Papworth team, added that they have reduced ischemic time to about 15 minutes. “That’s considerably shorter than reperfusing the heart outside the body,” he said. “This results in a healthier organ for the recipient.”

The NRP approach is also less expensive than direct procurement as one OCS box costs about $75,000.

He pointed out that the NRP approach can also be used for heart transplants in children and even small babies, while currently the direct procurement technique is not typically suitable for children because the OCS box was not designed for small hearts.

DCD, using either technique, has increased the heart transplant rate by 40% at Papworth, and is being used at all seven transplant centers in the United Kingdom, “a world first,” noted Dr. Large.

The Papworth team recently published its 5-year experience with 25 NRP transplants and 85 direct procurement transplants. Survival in recipients was no different, although there was some suggestion that the NRP hearts may have been in slightly better condition, possibly being more resistant to immunological rejection.

Ethical concerns about NRP

Restarting the circulation during the NRP process has raised ethical concerns.

When the NRP technique was first used in the United States, these ethical questions were raised by several groups, including the American College of Physicians (ACP).

Harry Peled, MD, Providence St. Jude Medical Center, Fullerton, Calif., coauthor of a recent Viewpoint on the issue, is board-certified in both cardiology and critical care, and said he is a supporter of DCD using direct procurement, but he does not believe that NRP is ethical at present. He is not part of the ACP, but said his views align with those of the organization.

There are two ethical problems with NRP, he said. The first is whether by restarting the circulation, the NRP process violates the U.S. definition of death, and retrieval of organs would therefore violate the dead donor rule.

“American law states that death is the irreversible cessation of brain function or of circulatory function. But with NRP, the circulation is artificially restored, so the cessation of circulatory function is not irreversible,” Dr. Peled pointed out.

“I have no problem with DCD using direct procurement as we are not restarting the circulation. But NRP is restarting the circulation and that is a problem for me,” Dr. Peled said. “I would argue that by performing NRP, we are resuscitating the patient.”

The second ethical problem with NRP is concern about whether, during the process, there would be any circulation to the brain, and if so, would this be enough to restore some brain function? Before NRP is started, the main arch vessel arteries to the head are clamped to prevent flow to the brain, but there are worries that some blood flow may still be possible through small collateral vessels.

“We have established that these patients do not have enough brain function for a meaningful life, which is why a decision has been made to remove life support, but they have not been declared brain dead,” Dr. Peled said.

With direct procurement, the circulation is not restarted so there is no chance that any brain function will be restored, he said. “But with NRP, because the arch vessels have to be clamped to prevent brain circulation, that is admitting there is concern that brain function may be restored if circulation to the brain is reestablished, and brain function is compatible with life. As we do not know whether there is any meaningful circulation to the brain via the small collaterals, there is, in effect, a risk of bringing the patient back to life.”

The other major concern for some is whether even a very small amount of circulation to the brain would be enough to support consciousness, and “we don’t know that for certain,” Dr. Peled said.

The argument for NRP

Nader Moazami, MD, professor of cardiovascular surgery, NYU Langone Health, New York, is one of the more vocal proponents of NRP for DCD heart transplantation in the United States, and has coauthored responses to these ethical concerns.

“People are confusing many issues to produce an argument against NRP,” he said.

“Our position is that death has already been declared based on the lack of circulatory function for over 5 minutes and this has been with the full agreement of the family, knowing that the patient has no chance of a meaningful life. No one is thinking of trying to resuscitate the patient. It has already been established that any future efforts to resuscitate are futile. In this case, we are not resuscitating the patient by restarting the circulation. It is just regional perfusion of the organs.”

Dr. Moazami pointed out this concept was accepted for the practice of abdominal DCD when it first started in the United States in the 1990s where cold perfusion was used to preserve the abdominal organs before they were retrieved from the body.

“The new approach of using NRP is similar except that it involves circulating warm blood, which will preserve organs better and result in higher quality organs for the recipient.”

On the issue of concern about possible circulation to the brain, Dr. Moazami said: “The ethical critics of NRP are questioning whether the brain may not be dead. We are arguing that the patient has already been declared dead as they have had a circulatory death. You cannot die twice.”

He maintained that the clamping of the arch vessels to the head will ensure that when the circulation is restarted “the natural process of circulatory death leading to brain death will continue to progress.”

On the concerns about possible collateral flow to the brain, Dr. Moazami said there is no evidence that this occurs. “Prominent neurologists have said it is impossible for collaterals to provide any meaningful blood flow to the brain in this situation. And even if there is small amount of blood flow to the brain, this would be insufficient to maintain any meaningful brain function.”

But Dr. Peled argues that this has not been proved. “Even though we don’t think there is enough circulation to the brain for any function with NRP, we don’t know that with 100% certainty,” he said. “In my view, if there is a possibility of even the smallest amount of brain flow, we are going against the dead donor rule. We are rewriting the rules of death.”

Dr. Moazami countered: “Nothing in life is 100%, particularly in medicine. With that argument can you also prove with 100% certainty to me that there is absolutely no brain function with regular direct procurement DCD? We know that brain death has started, but the question is: Has it been completed? We don’t know the answer to this question with 100% certainty, but that is the case for regular direct procurement DCD as well, and that has been accepted by almost everyone.

“The whole issue revolves around when are we comfortable that death has occurred,” he said. “Those against NRP are concerned that organs are being taken before the patient is dead. But the key point is that the patient has already been declared dead.”

Since there is some concern over the ethics of NRP, why not just stick to DCD with direct procurement?

Dr. Moazami argued that NRP results in healthier organs. “NRP allows more successful heart transplants, liver transplants, lung transplants. It preserves all the organs better,” he said. “This will have a big impact on recipients – they would obviously much prefer a healthier organ. In addition, the process is easier and cheaper, so more centers will be able to do it, therefore more transplants will get done and more lives will be saved if NRP is used.”

He added: “I am a physician taking care of sick patients. I believe I have to respect the wishes of the donor and the donor family; make sure I’m not doing any harm to the donor; and ensure the best quality possible of the organ I am retrieving to best serve the recipient. I am happy I am doing this by using NRP for DCD heart transplantation.”

But Dr. Peled argued that while NRP may have some possible advantages over direct procurement, that does not justify allowing a process to go ahead that is unethical.

“The fact that NRP may result in some benefits doesn’t justify violating the dead donor rule or the possibility, however small, of causing pain to the donor. If it’s unethical, it’s unethical. Full stop,” he said.

“I feel that NRP is not respecting the rights of our patients and that the process does not have adequate transparency. We took it to our local ethics committee, and they decided not to approve NRP in our health care system. I agree with this decision,” Dr. Peled said.

“The trouble is different experts and different countries are not in agreement about this,” he added. “Reasonable, well-informed people are in disagreement. I do not believe we can have a standard of care where there is not consensus.”

Cautious nod

In a 2022 consensus statement, the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) gave a cautious nod toward DCD and NRP, dependent on local recommendations.

The ISHLT conclusion reads: “With appropriate consideration of the ethical principles involved in organ donation, DCD can be undertaken in a morally permissible manner. In all cases, the introduction of DCD programs should be in accordance with local legal regulations. Countries lacking a DCD pathway should be encouraged to develop national ethical, professional, and legal frameworks to address both public and professional concerns.”

The author of a recent editorial on the subject, Ulrich P. Jorde, MD, head of the heart transplant program at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, said, “DCD is a great step forward. People regularly die on the heart transplant waiting list. DCD will increase the supply of donor hearts by 20% to 30%.”

However, he noted that while most societies have agreed on a protocol for organ donation based on brain death, the situation is more complicated with circulatory death.

“Different countries have different definitions of circulatory death. How long do we have to wait after the heart has stopped beating before the patient is declared dead? Most countries have agreed on 5 minutes, but other countries have imposed different periods and as such, different definitions of death.

“The ISHLT statement says that restarting the circulation is acceptable if death has been certified according to prevailing law and surgical interventions are undertaken to preclude any restoration of cerebral circulation. But our problem is that different regional societies have different definitions of circulatory, death which makes the situation confusing.”

Dr. Jorde added: “We also have to weigh the wishes of the donor and their family. If family, advocating what are presumed to be the donor’s wishes, have decided that DCD would be acceptable and they understand the concept and wish to donate the organs after circulatory death, this should be strongly considered under the concept of self-determination, a basic human right.”

Variations in practice around the world

This ethical debate has led to large variations in practice around the world, with some countries, such as Spain, allowing both methods of DCD, while Australia allows direct procurement but not NRP, and Germany currently does not allow DCD at all.

In the United States, things are even more complicated, with some states allowing NRP while others don’t. Even within states, some hospitals and transplant organizations allow NRP, and others don’t.

David A. D’Alessandro, MD, cardiac surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, uses only the direct procurement approach as his region does not allow NRP.

“The direct procurement approach is not controversial and to me that’s a big advantage. I believe we need to agree on the ethics first, and then get into a debate about which technique is better,” he told this news organization.

Dr. D’Alessandro and his group recently published the results of their study, with direct procurement DCD heart transplantation showing similar short-term clinical outcomes to DBD.

“We are only doing direct procurement and we are seeing good results that appear to be comparable to DBD. That is good enough for me,” he said.

Dr. D’Alessandro estimates that in the United States both types of DCD procedures are currently being done about equally.

“Anything we can do to increase the amount of hearts available for transplantation is a big deal,” he said. “At the moment, only the very sickest patients get a heart transplant, and many patients die on the transplant waiting list. Very sadly, many young people die every year from a circulatory death after having life support withdrawn. Before DCD, these beautiful functional organs were not able to be used. Now we have a way of saving lives with these organs.”

Dr. D’Alessandro noted that more and more centers in the United States are starting to perform DCD heart transplants.

“Not every transplant center may join in as the DCD procedures are very resource-intensive and time-consuming. For low-volume transplant centers, it may not be worth the expense and anguish to do DCD heart transplants. But bigger centers will need to engage in DCD to remain competitive. My guess is that 50%-70% of U.S. transplant centers will do DCD in future.”

He said he thinks it is a “medical shortcoming” that agreement cannot be reached on the ethics of NRP. “In an ideal world everyone would be on the same page. It makes me a bit uncomfortable that some people think it’s okay and some people don’t.”

Adam DeVore, MD, a cardiologist at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., the first U.S. center to perform an adult DCD heart transplant, reported that his institution uses both methods, with the choice sometimes depending on how far the heart must travel.

“If the recipient is near, NRP may be chosen as the heart is transported on ice, but if it needs to go further away we are more likely to choose direct procurement and use of the OCS box,” he said.

“I am really proud of what we’ve been able to do, helping to introduce DCD in the U.S.,” Dr. DeVore said. “This is having a massive benefit in increasing the number of hearts for donation with great outcomes.”

But he acknowledged that the whole concept of DCD is somewhat controversial.

“The idea of brain death really came about for the purpose of heart donation. The two things are very intricately tied. Trying to do heart donation without brain death having been declared is foreign to people. Also, in DCD there is the issue of [this]: When life support is removed, how long do we wait before death can be declared? That could be in conflict with how long the organ needs to remain viable. We are going through the process now of looking at these questions. There is a lot of variation in the U.S. about the withdrawal of care and the declaration of death, which is not completely standardized.

“But the concept of circulatory death itself is accepted after the withdrawal of life support. I think it’s the rush to take the organs out that makes it more difficult.”

Dr. DeVore said the field is moving forward now. “As the process has become more common, people have become more comfortable, probably because of the big difference it will make to saving lives. But we do need to try and standardize best practices.”

A recent Canadian review of the ethics of DCD concluded that the direct procurement approach would be in alignment with current medical guidelines, but that further work is required to evaluate the consistency of NRP with current Canadian death determination policy and to ensure the absence of brain perfusion during this process.

In the United Kingdom, the definition of death is brain-based, and brain death is defined on a neurological basis.

Dr. Stephen Large from Papworth explained that this recognizes the presence of brain-stem death through brain stem reflex testing after the withdrawal of life support, cardiorespiratory arrest and 5 further minutes of ischemia. As long as NRP does not restore intracranial (brainstem) perfusion after death has been confirmed, then it is consistent with laws for death determination and therefore both direct procurement and NRP are permissible.

However, the question over possible collateral flow to the brain has led the United Kingdom to pause the NRP technique as routine practice while this is investigated further. So, at the present time, the vast majority of DCD heart transplants are being conducted using the direct procurement approach.

But the United Kingdom is facing the bigger challenge: national funding that will soon end. “The DCD program in the U.K. has been extremely successful, increasing heart transplant rates by up to 28%,” Dr. Berman said. “Everybody wants it to continue. But at present the DCD program only has national funding in the U.K. until March 2023. We don’t know what will happen after that.”

The current model in the United Kingdom consists of three specialized DCD heart retrieval teams, a national protocol of direct organ procurement and delivery of DCD hearts to all seven transplant programs, both adult and pediatric.

If the national funding is not extended, “we will go back to individual hospitals trying to fund their own programs. That will be a serious threat to the program and could result in a large reduction in heart transplants,” said Dr. Berman.

Definition of death

The crux of the issue with regard to NRP seems to be variations in how death is defined and the interpretation of those definitions.

DCD donors will have had many tests indicating severe brain damage, a neurologist will have declared the prognosis is futile, and relatives will have agreed to withdraw life support, Dr. Jorde said. “The heart stops beating, and the stand-off time means that blood flow to the brain ceases completely for at least 5 minutes before circulatory death is declared. This is enough on its own to stop brain function.”

Dr. Large made the point that by the time the circulation is reestablished with NRP, more time has elapsed, and the brain will have been without perfusion for much longer than 5 minutes, so it would be “physiologically almost impossible” for there to be any blood flow to the brain.

“Because these brains are already very damaged before life support was removed, the intracranial pressure is high, which will further discourage blood flow to the brain,” he said. Then the donor goes through a period of anoxic heart arrest, up to 16 minutes at a minimum of no blood supply, enough on its own to stop meaningful brain function.

“It’s asking an awful lot to believe that there might be any brain function left,” he said. “And if, on reestablishing the circulation with NRP, there is any blood in the collaterals, the pressure of such flow is so low it won’t enter the brain.”

Dr. Large also pointed out that the fact that the United Kingdom requires a neurologic definition for brain-stem death makes the process easier.

In Australia, St. Vincent’s cardiologist Dr. MacDonald noted that death is defined as the irreversible cessation of circulation, so the NRP procedure is not allowed.

“With NRP, there is an ethical dilemma over whether the patient has legally died or not. Different countries have different ways of defining death. Perhaps society will have to review of the definition of death,” he suggested. Death is a process, “but for organ donation, we have to choose a moment in time of that process that satisfies everyone – when there is no prospect of recovery of the donor but the organs can still be utilized without harming the donor.”

Dr. MacDonald said the field is in transition. “I don’t want to argue that one technique is better than the other; I think it’s good to have access to both techniques. Anything that will increase the number of transplants we can do is a good thing.”

Collaborative decision

Everyone seems to agree that there should be an effort to try to define death in a uniform way worldwide, and that international, national and local regulations are aligned with each other.

Dr. Jorde said: “It is of critical importance that local guidelines are streamlined, firstly in any one given country and then globally, and these things must be discussed transparently within society with all stakeholders – doctors, patients, citizens.”

Dr. Peled, from Providence St. Jude in California, concurred: “There is the possibility that we could change the definition of death, but that cannot be a decision based solely on transplant organizations. It has to be a collaborative decision with a large input from groups who do not have an interest in the procurement of organs.”

He added: “The dialogue so far has been civil, and everybody is trying to do the right thing. My hope is that as a civilized society we will figure out a way forward. At present, there is significant controversy about NRP, and families need to know that. My main concern is that if there is any lack of transparency in getting informed consent, then this risks people losing trust in the donation system.”

Dr. Moazami, from NYU Langone, said the controversy has cast a cloud over the practice of NRP throughout the world. “We need to get it sorted out.”

He said he believes the way forward is to settle the question of whether there is any meaningful blood flow to the brain with the NRP technique.

“This is where the research has to focus. I believe this concern is hypothetical, but I am happy to do the studies to confirm that. Then, the issue should come to a rest. I think that is the right way forward – to do the studies rather than enforcing a moratorium on the practice because of a hypothetical concern.”

These studies on blood flow to the brain are now getting started in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

The U.K. study is being run by Antonio Rubino, MD, consultant in cardiothoracic anesthesia and intensive care at Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation and clinical lead, organ donation. Dr. Rubino explained that the study will assess cerebral blood flow using CT angiography of the brain. “We hypothesize that this will provide evidence to indicate that brain blood flow is not present during NRP and promote trust in the use of NRP in routine practice,” he said.

Dr. Large said: “Rather than having these tortured arguments, we will do the measurements. For the sake of society in this situation, I think it’s good to stop and take a breath. We must measure this, and we are doing just that.”

If there is any blood flow at all, Dr. Large said they will then have to seek expert guidance. “Say we find there is 50 mL of blood flow and normal blood flow is 1,500 mL/min. We will need expert guidance on whether it is remotely possible to be sentient on that. I would say it would be extraordinarily unlikely.”

Dr. Berman summarized the situation: “DCD is increasing the availability of hearts for transplant. This is saving lives, reducing the number of patients on the waiting list, and reducing hospital stays for patients unable to leave the hospital without a transplant. It is definitely here to stay. It is crucial that it gets funded properly, and it is also crucial that we resolve the NRP ethical issues as soon as possible.”

He is hopeful that some of these issues will be resolved this year.

Dr. MacDonald reported he has received “in-kind” support from Transmedics through provision of research modules for preclinical research studies. Dr. D’Alessandro reported he is on the speakers bureau for Abiomed, not relevant to this article. No other relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relatively recent innovation of heart transplantation after circulatory death of the donor is increasing the number of donor hearts available and leading to many more lives on the heart transplant waiting list being saved. Experts agree it’s a major and very welcome advance in medicine.

However, some of the processes involved in one approach to donation after circulatory death has raised ethical concerns and questions about whether they violate the “dead donor rule” – a principle that requires patients be declared dead before removal of life-sustaining organs for transplant.

Experts in the fields of transplantation and medical ethics have yet to reach consensus, causing problems for the transplant community, who worry that this could cause a loss of confidence in the entire transplant process.

A new pathway for heart transplantation

The traditional approach to transplantation is to retrieve organs from a donor who has been declared brain dead, known as “donation after brain death (DBD).” These patients have usually suffered a catastrophic brain injury but survived to get to intensive care.

As the brain swells because of injury, it becomes evident that all brain function is lost, and the patient is declared brain dead. However, breathing is maintained by the ventilator and the heart is still beating. Because the organs are being oxygenated, there is no immediate rush to retrieve the organs and the heart can be evaluated for its suitability for transplant in a calm and methodical way before it is removed.

However, there is a massive shortage of organs, especially hearts, partially because of the limited number of donors who are declared brain dead in that setting.

In recent years, another pathway for organ transplantation has become available: “donation after circulatory death (DCD).” These patients also have suffered a catastrophic brain injury considered to be nonsurvivable, but unlike the DBD situation, the brain still has some function, so the patient does not meet the criteria for brain death.

Still, because the patient is considered to have no chance of a meaningful recovery, the family often recognizes the futility of treatment and agrees to the withdrawal of life support. When this happens, the heart normally stops beating after a period of time. There is then a “stand-off time” – normally 5 minutes – after which death is declared and the organs can be removed.

The difficulty with this approach, however, is that because the heart has been stopped, it has been deprived of oxygen, potentially causing injury. While DCD has been practiced for several years to retrieve organs such as the kidney, liver, lungs, and pancreas, the heart is more difficult as it is more susceptible to oxygen deprivation. And for the heart to be assessed for transplant suitability, it should ideally be beating, so it has to be reperfused and restarted quickly after death has been declared.

For many years it was thought the oxygen deprivation that occurs after circulatory death would be too much to provide a functional organ. But researchers in the United Kingdom and Australia developed techniques to overcome this problem, and early DCD heart transplants took place in 2014 in Australia, and in 2015 in the United Kingdom.

Heart transplantation after circulatory death has now become a routine part of the transplant program in many countries, including the United States, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Austria.

In the United States, 348 DCD heart transplants were performed in 2022, with numbers expected to reach 700 to 800 this year as more centers come online.

It is expected that most countries with heart transplant programs will follow suit and the number of donor hearts will increase by up to 30% worldwide because of DCD.

Currently, there are about 8,000 heart transplants worldwide each year and with DCD this could rise to about 10,000, potentially an extra 2,000 lives saved each year, experts estimate.

Two different approaches to DCD heart transplantation have been developed.

The direct procurement approach

The Australian group, based at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, developed a technique referred to as “direct procurement”: after the standoff period and declaration of circulatory death, the chest is opened, and the heart is removed. New technology, the Organ Care System (OCS) heart box (Transmedics), is then used to reperfuse and restart the heart outside the body so its suitability for transplant can be assessed.

The heart is kept perfused and beating in the OCS box while it is being transported to the recipient. This has enabled longer transit times than the traditional way of transporting the nonbeating heart on ice.

Peter MacDonald, MD, PhD, from the St Vincent’s group that developed this approach, said, “Most people thought a heart from a DCD donor would not survive transport – that the injury to the heart from the combination of life support withdrawal, stand-off time, and cold storage would be too much. But we modeled the process in the lab and were able to show that we were able to get the heart beating again after withdrawal of life support.”

Dr. McDonald noted that “the recipient of their first human DCD heart transplant using this machine in 2014 is still alive and well.” The Australian group has now done 85 of these DCD heart transplants, and they have increased the number of heart transplant procedures at St. Vincent’s Hospital by 25%.

Normothermic regional perfusion (NRP)

The U.K. group, based at the Royal Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, England, developed a different approach to DCD: After the standoff period and the declaration of circulatory death, the donor is connected to a heart/lung machine using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) so that the heart is perfused and starts beating again inside the body. This approach is known as normothermic regional perfusion (NRP).

Marius Berman, MD, surgical lead for Transplantation and Mechanical Circulatory Support at Papworth, explained that the NRP approach allows the heart to be perfused and restarted faster than direct procurement, resulting in a shorter ischemic time. The heart can be evaluated thoroughly for suitability for transplantation in situ before committing to transplantation, and because the heart is less damaged, it can be transported on ice without use of the OCS box.

“DCD is more complicated than DBD, because the heart has stopped and has to be restarted. Retrieval teams have to be very experienced,” Dr. Berman noted. “This is more of an issue for the direct procurement approach, where the chest has to be opened and the heart retrieved as fast as possible. It is a rush. The longer time without the heart being perfused correlates to an increased incidence of primary graft dysfunction. With NRP, we can get the heart started again more quickly, which is crucial.”

Stephen Large, MBBS, another cardiothoracic surgeon with the Papworth team, added that they have reduced ischemic time to about 15 minutes. “That’s considerably shorter than reperfusing the heart outside the body,” he said. “This results in a healthier organ for the recipient.”

The NRP approach is also less expensive than direct procurement as one OCS box costs about $75,000.

He pointed out that the NRP approach can also be used for heart transplants in children and even small babies, while currently the direct procurement technique is not typically suitable for children because the OCS box was not designed for small hearts.

DCD, using either technique, has increased the heart transplant rate by 40% at Papworth, and is being used at all seven transplant centers in the United Kingdom, “a world first,” noted Dr. Large.

The Papworth team recently published its 5-year experience with 25 NRP transplants and 85 direct procurement transplants. Survival in recipients was no different, although there was some suggestion that the NRP hearts may have been in slightly better condition, possibly being more resistant to immunological rejection.

Ethical concerns about NRP

Restarting the circulation during the NRP process has raised ethical concerns.

When the NRP technique was first used in the United States, these ethical questions were raised by several groups, including the American College of Physicians (ACP).

Harry Peled, MD, Providence St. Jude Medical Center, Fullerton, Calif., coauthor of a recent Viewpoint on the issue, is board-certified in both cardiology and critical care, and said he is a supporter of DCD using direct procurement, but he does not believe that NRP is ethical at present. He is not part of the ACP, but said his views align with those of the organization.

There are two ethical problems with NRP, he said. The first is whether by restarting the circulation, the NRP process violates the U.S. definition of death, and retrieval of organs would therefore violate the dead donor rule.

“American law states that death is the irreversible cessation of brain function or of circulatory function. But with NRP, the circulation is artificially restored, so the cessation of circulatory function is not irreversible,” Dr. Peled pointed out.

“I have no problem with DCD using direct procurement as we are not restarting the circulation. But NRP is restarting the circulation and that is a problem for me,” Dr. Peled said. “I would argue that by performing NRP, we are resuscitating the patient.”

The second ethical problem with NRP is concern about whether, during the process, there would be any circulation to the brain, and if so, would this be enough to restore some brain function? Before NRP is started, the main arch vessel arteries to the head are clamped to prevent flow to the brain, but there are worries that some blood flow may still be possible through small collateral vessels.

“We have established that these patients do not have enough brain function for a meaningful life, which is why a decision has been made to remove life support, but they have not been declared brain dead,” Dr. Peled said.

With direct procurement, the circulation is not restarted so there is no chance that any brain function will be restored, he said. “But with NRP, because the arch vessels have to be clamped to prevent brain circulation, that is admitting there is concern that brain function may be restored if circulation to the brain is reestablished, and brain function is compatible with life. As we do not know whether there is any meaningful circulation to the brain via the small collaterals, there is, in effect, a risk of bringing the patient back to life.”

The other major concern for some is whether even a very small amount of circulation to the brain would be enough to support consciousness, and “we don’t know that for certain,” Dr. Peled said.

The argument for NRP

Nader Moazami, MD, professor of cardiovascular surgery, NYU Langone Health, New York, is one of the more vocal proponents of NRP for DCD heart transplantation in the United States, and has coauthored responses to these ethical concerns.

“People are confusing many issues to produce an argument against NRP,” he said.

“Our position is that death has already been declared based on the lack of circulatory function for over 5 minutes and this has been with the full agreement of the family, knowing that the patient has no chance of a meaningful life. No one is thinking of trying to resuscitate the patient. It has already been established that any future efforts to resuscitate are futile. In this case, we are not resuscitating the patient by restarting the circulation. It is just regional perfusion of the organs.”

Dr. Moazami pointed out this concept was accepted for the practice of abdominal DCD when it first started in the United States in the 1990s where cold perfusion was used to preserve the abdominal organs before they were retrieved from the body.

“The new approach of using NRP is similar except that it involves circulating warm blood, which will preserve organs better and result in higher quality organs for the recipient.”

On the issue of concern about possible circulation to the brain, Dr. Moazami said: “The ethical critics of NRP are questioning whether the brain may not be dead. We are arguing that the patient has already been declared dead as they have had a circulatory death. You cannot die twice.”

He maintained that the clamping of the arch vessels to the head will ensure that when the circulation is restarted “the natural process of circulatory death leading to brain death will continue to progress.”

On the concerns about possible collateral flow to the brain, Dr. Moazami said there is no evidence that this occurs. “Prominent neurologists have said it is impossible for collaterals to provide any meaningful blood flow to the brain in this situation. And even if there is small amount of blood flow to the brain, this would be insufficient to maintain any meaningful brain function.”

But Dr. Peled argues that this has not been proved. “Even though we don’t think there is enough circulation to the brain for any function with NRP, we don’t know that with 100% certainty,” he said. “In my view, if there is a possibility of even the smallest amount of brain flow, we are going against the dead donor rule. We are rewriting the rules of death.”

Dr. Moazami countered: “Nothing in life is 100%, particularly in medicine. With that argument can you also prove with 100% certainty to me that there is absolutely no brain function with regular direct procurement DCD? We know that brain death has started, but the question is: Has it been completed? We don’t know the answer to this question with 100% certainty, but that is the case for regular direct procurement DCD as well, and that has been accepted by almost everyone.

“The whole issue revolves around when are we comfortable that death has occurred,” he said. “Those against NRP are concerned that organs are being taken before the patient is dead. But the key point is that the patient has already been declared dead.”

Since there is some concern over the ethics of NRP, why not just stick to DCD with direct procurement?

Dr. Moazami argued that NRP results in healthier organs. “NRP allows more successful heart transplants, liver transplants, lung transplants. It preserves all the organs better,” he said. “This will have a big impact on recipients – they would obviously much prefer a healthier organ. In addition, the process is easier and cheaper, so more centers will be able to do it, therefore more transplants will get done and more lives will be saved if NRP is used.”

He added: “I am a physician taking care of sick patients. I believe I have to respect the wishes of the donor and the donor family; make sure I’m not doing any harm to the donor; and ensure the best quality possible of the organ I am retrieving to best serve the recipient. I am happy I am doing this by using NRP for DCD heart transplantation.”

But Dr. Peled argued that while NRP may have some possible advantages over direct procurement, that does not justify allowing a process to go ahead that is unethical.

“The fact that NRP may result in some benefits doesn’t justify violating the dead donor rule or the possibility, however small, of causing pain to the donor. If it’s unethical, it’s unethical. Full stop,” he said.

“I feel that NRP is not respecting the rights of our patients and that the process does not have adequate transparency. We took it to our local ethics committee, and they decided not to approve NRP in our health care system. I agree with this decision,” Dr. Peled said.

“The trouble is different experts and different countries are not in agreement about this,” he added. “Reasonable, well-informed people are in disagreement. I do not believe we can have a standard of care where there is not consensus.”

Cautious nod

In a 2022 consensus statement, the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) gave a cautious nod toward DCD and NRP, dependent on local recommendations.

The ISHLT conclusion reads: “With appropriate consideration of the ethical principles involved in organ donation, DCD can be undertaken in a morally permissible manner. In all cases, the introduction of DCD programs should be in accordance with local legal regulations. Countries lacking a DCD pathway should be encouraged to develop national ethical, professional, and legal frameworks to address both public and professional concerns.”

The author of a recent editorial on the subject, Ulrich P. Jorde, MD, head of the heart transplant program at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, said, “DCD is a great step forward. People regularly die on the heart transplant waiting list. DCD will increase the supply of donor hearts by 20% to 30%.”

However, he noted that while most societies have agreed on a protocol for organ donation based on brain death, the situation is more complicated with circulatory death.

“Different countries have different definitions of circulatory death. How long do we have to wait after the heart has stopped beating before the patient is declared dead? Most countries have agreed on 5 minutes, but other countries have imposed different periods and as such, different definitions of death.

“The ISHLT statement says that restarting the circulation is acceptable if death has been certified according to prevailing law and surgical interventions are undertaken to preclude any restoration of cerebral circulation. But our problem is that different regional societies have different definitions of circulatory, death which makes the situation confusing.”

Dr. Jorde added: “We also have to weigh the wishes of the donor and their family. If family, advocating what are presumed to be the donor’s wishes, have decided that DCD would be acceptable and they understand the concept and wish to donate the organs after circulatory death, this should be strongly considered under the concept of self-determination, a basic human right.”

Variations in practice around the world

This ethical debate has led to large variations in practice around the world, with some countries, such as Spain, allowing both methods of DCD, while Australia allows direct procurement but not NRP, and Germany currently does not allow DCD at all.

In the United States, things are even more complicated, with some states allowing NRP while others don’t. Even within states, some hospitals and transplant organizations allow NRP, and others don’t.

David A. D’Alessandro, MD, cardiac surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, uses only the direct procurement approach as his region does not allow NRP.

“The direct procurement approach is not controversial and to me that’s a big advantage. I believe we need to agree on the ethics first, and then get into a debate about which technique is better,” he told this news organization.

Dr. D’Alessandro and his group recently published the results of their study, with direct procurement DCD heart transplantation showing similar short-term clinical outcomes to DBD.

“We are only doing direct procurement and we are seeing good results that appear to be comparable to DBD. That is good enough for me,” he said.

Dr. D’Alessandro estimates that in the United States both types of DCD procedures are currently being done about equally.

“Anything we can do to increase the amount of hearts available for transplantation is a big deal,” he said. “At the moment, only the very sickest patients get a heart transplant, and many patients die on the transplant waiting list. Very sadly, many young people die every year from a circulatory death after having life support withdrawn. Before DCD, these beautiful functional organs were not able to be used. Now we have a way of saving lives with these organs.”

Dr. D’Alessandro noted that more and more centers in the United States are starting to perform DCD heart transplants.

“Not every transplant center may join in as the DCD procedures are very resource-intensive and time-consuming. For low-volume transplant centers, it may not be worth the expense and anguish to do DCD heart transplants. But bigger centers will need to engage in DCD to remain competitive. My guess is that 50%-70% of U.S. transplant centers will do DCD in future.”

He said he thinks it is a “medical shortcoming” that agreement cannot be reached on the ethics of NRP. “In an ideal world everyone would be on the same page. It makes me a bit uncomfortable that some people think it’s okay and some people don’t.”

Adam DeVore, MD, a cardiologist at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., the first U.S. center to perform an adult DCD heart transplant, reported that his institution uses both methods, with the choice sometimes depending on how far the heart must travel.

“If the recipient is near, NRP may be chosen as the heart is transported on ice, but if it needs to go further away we are more likely to choose direct procurement and use of the OCS box,” he said.

“I am really proud of what we’ve been able to do, helping to introduce DCD in the U.S.,” Dr. DeVore said. “This is having a massive benefit in increasing the number of hearts for donation with great outcomes.”

But he acknowledged that the whole concept of DCD is somewhat controversial.

“The idea of brain death really came about for the purpose of heart donation. The two things are very intricately tied. Trying to do heart donation without brain death having been declared is foreign to people. Also, in DCD there is the issue of [this]: When life support is removed, how long do we wait before death can be declared? That could be in conflict with how long the organ needs to remain viable. We are going through the process now of looking at these questions. There is a lot of variation in the U.S. about the withdrawal of care and the declaration of death, which is not completely standardized.

“But the concept of circulatory death itself is accepted after the withdrawal of life support. I think it’s the rush to take the organs out that makes it more difficult.”

Dr. DeVore said the field is moving forward now. “As the process has become more common, people have become more comfortable, probably because of the big difference it will make to saving lives. But we do need to try and standardize best practices.”

A recent Canadian review of the ethics of DCD concluded that the direct procurement approach would be in alignment with current medical guidelines, but that further work is required to evaluate the consistency of NRP with current Canadian death determination policy and to ensure the absence of brain perfusion during this process.

In the United Kingdom, the definition of death is brain-based, and brain death is defined on a neurological basis.

Dr. Stephen Large from Papworth explained that this recognizes the presence of brain-stem death through brain stem reflex testing after the withdrawal of life support, cardiorespiratory arrest and 5 further minutes of ischemia. As long as NRP does not restore intracranial (brainstem) perfusion after death has been confirmed, then it is consistent with laws for death determination and therefore both direct procurement and NRP are permissible.

However, the question over possible collateral flow to the brain has led the United Kingdom to pause the NRP technique as routine practice while this is investigated further. So, at the present time, the vast majority of DCD heart transplants are being conducted using the direct procurement approach.

But the United Kingdom is facing the bigger challenge: national funding that will soon end. “The DCD program in the U.K. has been extremely successful, increasing heart transplant rates by up to 28%,” Dr. Berman said. “Everybody wants it to continue. But at present the DCD program only has national funding in the U.K. until March 2023. We don’t know what will happen after that.”

The current model in the United Kingdom consists of three specialized DCD heart retrieval teams, a national protocol of direct organ procurement and delivery of DCD hearts to all seven transplant programs, both adult and pediatric.

If the national funding is not extended, “we will go back to individual hospitals trying to fund their own programs. That will be a serious threat to the program and could result in a large reduction in heart transplants,” said Dr. Berman.

Definition of death

The crux of the issue with regard to NRP seems to be variations in how death is defined and the interpretation of those definitions.

DCD donors will have had many tests indicating severe brain damage, a neurologist will have declared the prognosis is futile, and relatives will have agreed to withdraw life support, Dr. Jorde said. “The heart stops beating, and the stand-off time means that blood flow to the brain ceases completely for at least 5 minutes before circulatory death is declared. This is enough on its own to stop brain function.”

Dr. Large made the point that by the time the circulation is reestablished with NRP, more time has elapsed, and the brain will have been without perfusion for much longer than 5 minutes, so it would be “physiologically almost impossible” for there to be any blood flow to the brain.

“Because these brains are already very damaged before life support was removed, the intracranial pressure is high, which will further discourage blood flow to the brain,” he said. Then the donor goes through a period of anoxic heart arrest, up to 16 minutes at a minimum of no blood supply, enough on its own to stop meaningful brain function.

“It’s asking an awful lot to believe that there might be any brain function left,” he said. “And if, on reestablishing the circulation with NRP, there is any blood in the collaterals, the pressure of such flow is so low it won’t enter the brain.”

Dr. Large also pointed out that the fact that the United Kingdom requires a neurologic definition for brain-stem death makes the process easier.

In Australia, St. Vincent’s cardiologist Dr. MacDonald noted that death is defined as the irreversible cessation of circulation, so the NRP procedure is not allowed.

“With NRP, there is an ethical dilemma over whether the patient has legally died or not. Different countries have different ways of defining death. Perhaps society will have to review of the definition of death,” he suggested. Death is a process, “but for organ donation, we have to choose a moment in time of that process that satisfies everyone – when there is no prospect of recovery of the donor but the organs can still be utilized without harming the donor.”

Dr. MacDonald said the field is in transition. “I don’t want to argue that one technique is better than the other; I think it’s good to have access to both techniques. Anything that will increase the number of transplants we can do is a good thing.”

Collaborative decision

Everyone seems to agree that there should be an effort to try to define death in a uniform way worldwide, and that international, national and local regulations are aligned with each other.

Dr. Jorde said: “It is of critical importance that local guidelines are streamlined, firstly in any one given country and then globally, and these things must be discussed transparently within society with all stakeholders – doctors, patients, citizens.”

Dr. Peled, from Providence St. Jude in California, concurred: “There is the possibility that we could change the definition of death, but that cannot be a decision based solely on transplant organizations. It has to be a collaborative decision with a large input from groups who do not have an interest in the procurement of organs.”

He added: “The dialogue so far has been civil, and everybody is trying to do the right thing. My hope is that as a civilized society we will figure out a way forward. At present, there is significant controversy about NRP, and families need to know that. My main concern is that if there is any lack of transparency in getting informed consent, then this risks people losing trust in the donation system.”

Dr. Moazami, from NYU Langone, said the controversy has cast a cloud over the practice of NRP throughout the world. “We need to get it sorted out.”

He said he believes the way forward is to settle the question of whether there is any meaningful blood flow to the brain with the NRP technique.

“This is where the research has to focus. I believe this concern is hypothetical, but I am happy to do the studies to confirm that. Then, the issue should come to a rest. I think that is the right way forward – to do the studies rather than enforcing a moratorium on the practice because of a hypothetical concern.”

These studies on blood flow to the brain are now getting started in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

The U.K. study is being run by Antonio Rubino, MD, consultant in cardiothoracic anesthesia and intensive care at Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation and clinical lead, organ donation. Dr. Rubino explained that the study will assess cerebral blood flow using CT angiography of the brain. “We hypothesize that this will provide evidence to indicate that brain blood flow is not present during NRP and promote trust in the use of NRP in routine practice,” he said.

Dr. Large said: “Rather than having these tortured arguments, we will do the measurements. For the sake of society in this situation, I think it’s good to stop and take a breath. We must measure this, and we are doing just that.”

If there is any blood flow at all, Dr. Large said they will then have to seek expert guidance. “Say we find there is 50 mL of blood flow and normal blood flow is 1,500 mL/min. We will need expert guidance on whether it is remotely possible to be sentient on that. I would say it would be extraordinarily unlikely.”

Dr. Berman summarized the situation: “DCD is increasing the availability of hearts for transplant. This is saving lives, reducing the number of patients on the waiting list, and reducing hospital stays for patients unable to leave the hospital without a transplant. It is definitely here to stay. It is crucial that it gets funded properly, and it is also crucial that we resolve the NRP ethical issues as soon as possible.”

He is hopeful that some of these issues will be resolved this year.

Dr. MacDonald reported he has received “in-kind” support from Transmedics through provision of research modules for preclinical research studies. Dr. D’Alessandro reported he is on the speakers bureau for Abiomed, not relevant to this article. No other relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relatively recent innovation of heart transplantation after circulatory death of the donor is increasing the number of donor hearts available and leading to many more lives on the heart transplant waiting list being saved. Experts agree it’s a major and very welcome advance in medicine.

However, some of the processes involved in one approach to donation after circulatory death has raised ethical concerns and questions about whether they violate the “dead donor rule” – a principle that requires patients be declared dead before removal of life-sustaining organs for transplant.

Experts in the fields of transplantation and medical ethics have yet to reach consensus, causing problems for the transplant community, who worry that this could cause a loss of confidence in the entire transplant process.

A new pathway for heart transplantation

The traditional approach to transplantation is to retrieve organs from a donor who has been declared brain dead, known as “donation after brain death (DBD).” These patients have usually suffered a catastrophic brain injury but survived to get to intensive care.

As the brain swells because of injury, it becomes evident that all brain function is lost, and the patient is declared brain dead. However, breathing is maintained by the ventilator and the heart is still beating. Because the organs are being oxygenated, there is no immediate rush to retrieve the organs and the heart can be evaluated for its suitability for transplant in a calm and methodical way before it is removed.

However, there is a massive shortage of organs, especially hearts, partially because of the limited number of donors who are declared brain dead in that setting.

In recent years, another pathway for organ transplantation has become available: “donation after circulatory death (DCD).” These patients also have suffered a catastrophic brain injury considered to be nonsurvivable, but unlike the DBD situation, the brain still has some function, so the patient does not meet the criteria for brain death.

Still, because the patient is considered to have no chance of a meaningful recovery, the family often recognizes the futility of treatment and agrees to the withdrawal of life support. When this happens, the heart normally stops beating after a period of time. There is then a “stand-off time” – normally 5 minutes – after which death is declared and the organs can be removed.

The difficulty with this approach, however, is that because the heart has been stopped, it has been deprived of oxygen, potentially causing injury. While DCD has been practiced for several years to retrieve organs such as the kidney, liver, lungs, and pancreas, the heart is more difficult as it is more susceptible to oxygen deprivation. And for the heart to be assessed for transplant suitability, it should ideally be beating, so it has to be reperfused and restarted quickly after death has been declared.

For many years it was thought the oxygen deprivation that occurs after circulatory death would be too much to provide a functional organ. But researchers in the United Kingdom and Australia developed techniques to overcome this problem, and early DCD heart transplants took place in 2014 in Australia, and in 2015 in the United Kingdom.

Heart transplantation after circulatory death has now become a routine part of the transplant program in many countries, including the United States, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Austria.

In the United States, 348 DCD heart transplants were performed in 2022, with numbers expected to reach 700 to 800 this year as more centers come online.