User login

RECOVERY trial of COVID-19 treatments stops colchicine arm

On the advice of its independent data monitoring committee (DMC), the RECOVERY trial has stopped recruitment to the colchicine arm for lack of efficacy in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

“The DMC saw no convincing evidence that further recruitment would provide conclusive proof of worthwhile mortality benefit either overall or in any prespecified subgroup,” the British investigators announced on March 5.

“The RECOVERY trial has already identified two anti-inflammatory drugs – dexamethasone and tocilizumab – that improve the chances of survival for patients with severe COVID-19. So, it is disappointing that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, has no effect in these patients,” cochief investigator Martin Landray, MBChB, PhD, said in a statement.

“We do large, randomized trials to establish whether a drug that seems promising in theory has real benefits for patients in practice. Unfortunately, colchicine is not one of those,” said Dr. Landry, University of Oxford (England).

The RECOVERY trial is evaluating a range of potential treatments for COVID-19 at 180 hospitals in the United Kingdom, Indonesia, and Nepal, and was designed with the expectation that drugs would be added or dropped as the evidence changes. Since November 2020, the trial has included an arm comparing colchicine with usual care alone.

As part of a routine meeting March 4, the DMC reviewed data from a preliminary analysis based on 2,178 deaths among 11,162 patients, 94% of whom were being treated with a corticosteroid such as dexamethasone.

The results showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of 28-day mortality in patients randomized to colchicine versus usual care alone (20% vs. 19%; risk ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.11; P = .63).

Follow-up is ongoing and final results will be published as soon as possible, the investigators said. Thus far, there has been no convincing evidence of an effect of colchicine on clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Recruitment will continue to all other treatment arms – aspirin, baricitinib, Regeneron’s antibody cocktail, and, in select hospitals, dimethyl fumarate – the investigators said.

Cochief investigator Peter Hornby, MD, PhD, also from the University of Oxford, noted that this has been the largest trial ever of colchicine. “Whilst we are disappointed that the overall result is negative, it is still important information for the future care of patients in the U.K. and worldwide.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On the advice of its independent data monitoring committee (DMC), the RECOVERY trial has stopped recruitment to the colchicine arm for lack of efficacy in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

“The DMC saw no convincing evidence that further recruitment would provide conclusive proof of worthwhile mortality benefit either overall or in any prespecified subgroup,” the British investigators announced on March 5.

“The RECOVERY trial has already identified two anti-inflammatory drugs – dexamethasone and tocilizumab – that improve the chances of survival for patients with severe COVID-19. So, it is disappointing that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, has no effect in these patients,” cochief investigator Martin Landray, MBChB, PhD, said in a statement.

“We do large, randomized trials to establish whether a drug that seems promising in theory has real benefits for patients in practice. Unfortunately, colchicine is not one of those,” said Dr. Landry, University of Oxford (England).

The RECOVERY trial is evaluating a range of potential treatments for COVID-19 at 180 hospitals in the United Kingdom, Indonesia, and Nepal, and was designed with the expectation that drugs would be added or dropped as the evidence changes. Since November 2020, the trial has included an arm comparing colchicine with usual care alone.

As part of a routine meeting March 4, the DMC reviewed data from a preliminary analysis based on 2,178 deaths among 11,162 patients, 94% of whom were being treated with a corticosteroid such as dexamethasone.

The results showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of 28-day mortality in patients randomized to colchicine versus usual care alone (20% vs. 19%; risk ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.11; P = .63).

Follow-up is ongoing and final results will be published as soon as possible, the investigators said. Thus far, there has been no convincing evidence of an effect of colchicine on clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Recruitment will continue to all other treatment arms – aspirin, baricitinib, Regeneron’s antibody cocktail, and, in select hospitals, dimethyl fumarate – the investigators said.

Cochief investigator Peter Hornby, MD, PhD, also from the University of Oxford, noted that this has been the largest trial ever of colchicine. “Whilst we are disappointed that the overall result is negative, it is still important information for the future care of patients in the U.K. and worldwide.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On the advice of its independent data monitoring committee (DMC), the RECOVERY trial has stopped recruitment to the colchicine arm for lack of efficacy in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

“The DMC saw no convincing evidence that further recruitment would provide conclusive proof of worthwhile mortality benefit either overall or in any prespecified subgroup,” the British investigators announced on March 5.

“The RECOVERY trial has already identified two anti-inflammatory drugs – dexamethasone and tocilizumab – that improve the chances of survival for patients with severe COVID-19. So, it is disappointing that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, has no effect in these patients,” cochief investigator Martin Landray, MBChB, PhD, said in a statement.

“We do large, randomized trials to establish whether a drug that seems promising in theory has real benefits for patients in practice. Unfortunately, colchicine is not one of those,” said Dr. Landry, University of Oxford (England).

The RECOVERY trial is evaluating a range of potential treatments for COVID-19 at 180 hospitals in the United Kingdom, Indonesia, and Nepal, and was designed with the expectation that drugs would be added or dropped as the evidence changes. Since November 2020, the trial has included an arm comparing colchicine with usual care alone.

As part of a routine meeting March 4, the DMC reviewed data from a preliminary analysis based on 2,178 deaths among 11,162 patients, 94% of whom were being treated with a corticosteroid such as dexamethasone.

The results showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of 28-day mortality in patients randomized to colchicine versus usual care alone (20% vs. 19%; risk ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.11; P = .63).

Follow-up is ongoing and final results will be published as soon as possible, the investigators said. Thus far, there has been no convincing evidence of an effect of colchicine on clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Recruitment will continue to all other treatment arms – aspirin, baricitinib, Regeneron’s antibody cocktail, and, in select hospitals, dimethyl fumarate – the investigators said.

Cochief investigator Peter Hornby, MD, PhD, also from the University of Oxford, noted that this has been the largest trial ever of colchicine. “Whilst we are disappointed that the overall result is negative, it is still important information for the future care of patients in the U.K. and worldwide.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No vascular benefit of testosterone over exercise in aging men

Exercise training – but not testosterone therapy – improved vascular health in aging men with widening midsections and low to normal testosterone, new research suggests.

“Previous studies have suggested that men with higher levels of testosterone, who were more physically active, might have better health outcomes,” Bu Beng Yeap, MBBS, PhD, University of Western Australia, Perth, said in an interview. “We formulated the hypothesis that the combination of testosterone treatment and exercise training would improve the health of arteries more than either alone.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators randomly assigned 80 men, aged 50-70 years, to 12 weeks of 5% testosterone cream 2 mL applied daily or placebo plus a supervised exercise program that included machine-based resistance and aerobic (cycling) exercises two to three times a week or no additional exercise.

The men (mean age, 59 years) had low-normal testosterone (6-14 nmol/L), a waist circumference of at least 95 cm (37.4 inches), and no known cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 1 diabetes, or other clinically significant illnesses. Current smokers and men on testosterone or medications that would alter testosterone levels were also excluded.

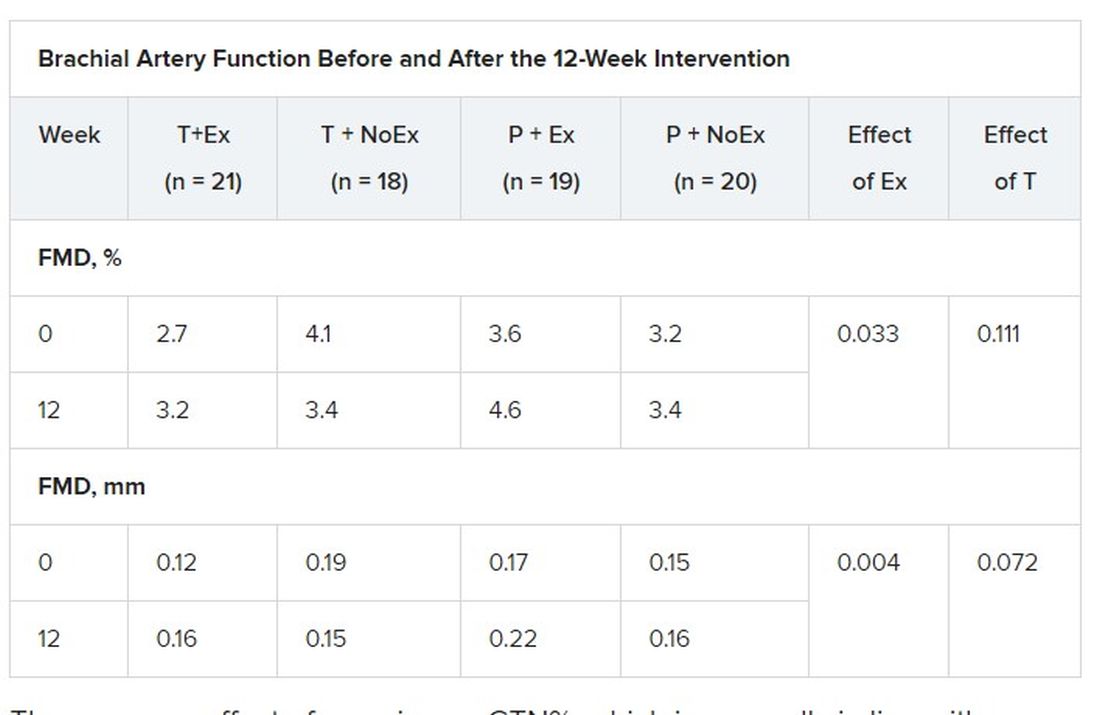

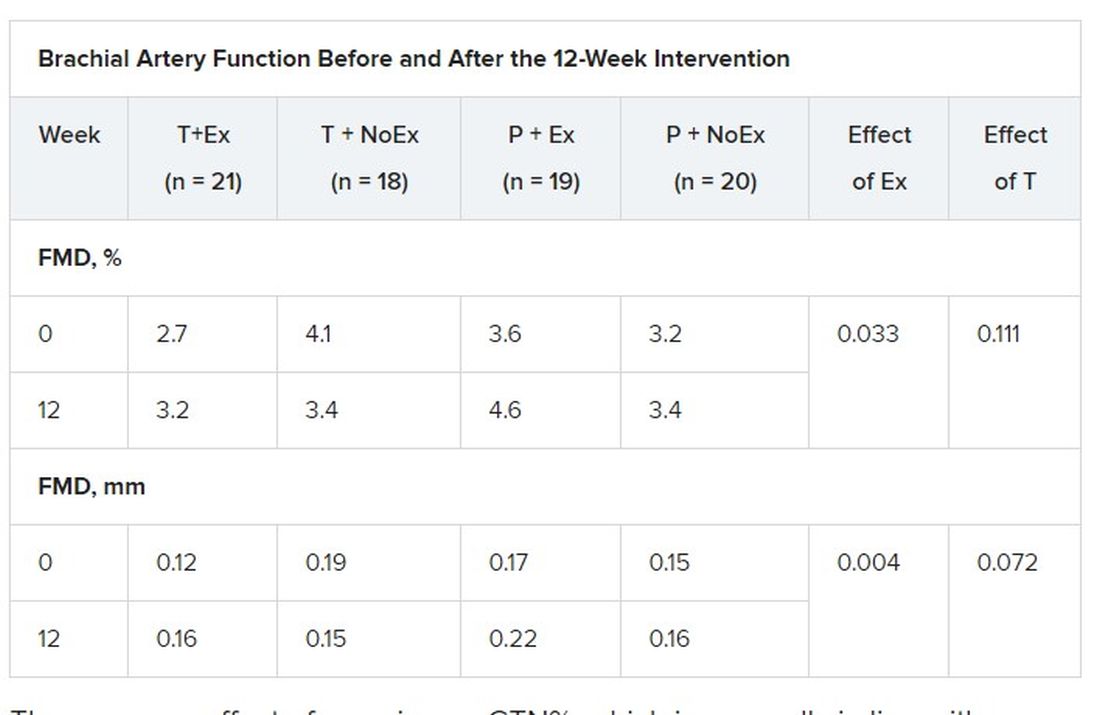

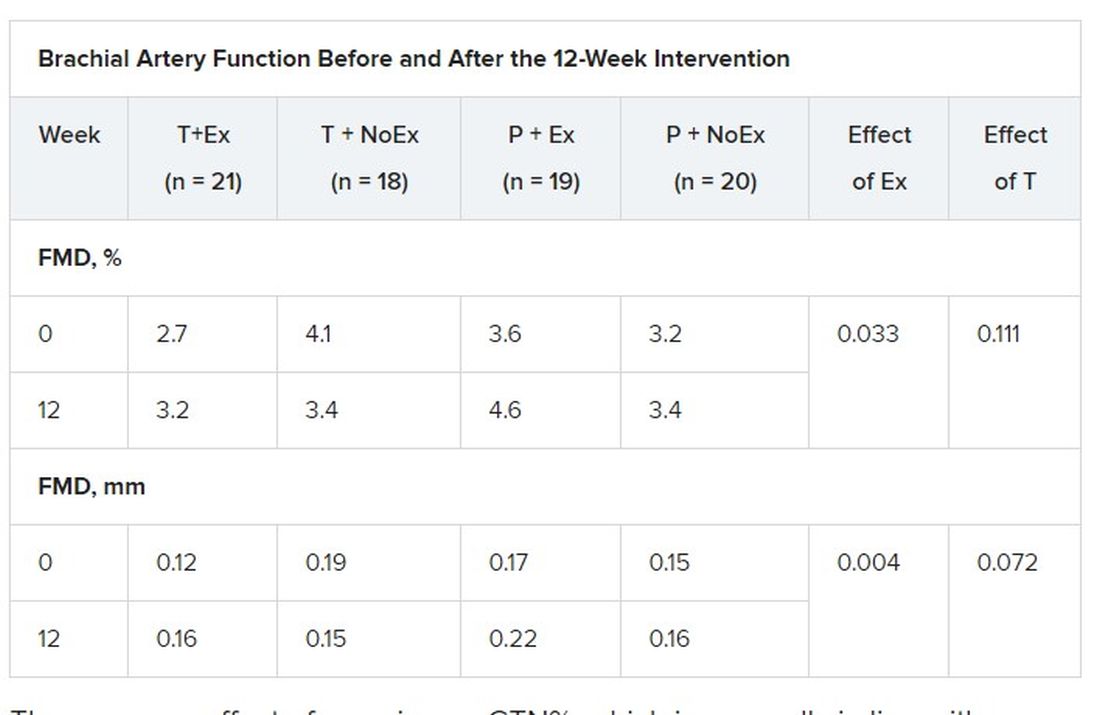

High-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery was used to assess flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) responses. FMD has been shown to be predictive of CVD risk, with a 1% increase in FMD associated with a 9%-13% decrease in future CVD events.

Based on participants’ daily dairies, testosterone adherence was 97.6%. Exercise adherence was 96.5% for twice-weekly attendance and 80.0% for thrice-weekly attendance, with no between-group differences.

As reported Feb. 22, 2021, in Hypertension, testosterone levels increased, on average, 3.0 nmol/L in both testosterone groups by week 12 (P = .003). In all, 62% of these men had levels of the hormone exceeding 14 nmol/L, compared with 29% of those receiving placebo.

Testosterone levels improved with exercise training plus placebo by 0.9 nmol/L, but fell with no exercise and placebo by 0.9 nmol/L.

In terms of vascular function, exercise training increased FMD when expressed as both the delta change (mm; P = .004) and relative rise from baseline diameter (%; P = .033).

There was no effect of exercise on GTN%, which is generally in line with exercise literature indicating that shear-mediated adaptations in response to episodic exercise occur largely in endothelial cells, the authors noted.

Testosterone did not affect any measures of FMD nor was there an effect on GTN response, despite previous evidence that lower testosterone doses might enhance smooth muscle function.

“Our main finding was that testosterone – at this dose over this duration of treatment – did not have a beneficial effect on artery health, nor did it enhance the effect of exercise,” said Dr. Yeap, who is also president of the Endocrine Society of Australia. “For middle-aged and older men wanting to improve the health of their arteries, exercise is better than testosterone!”

Shalender Bhasin, MBBS, director of research programs in men’s health, aging, and metabolism at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study is interesting from a mechanistic perspective and adds to the overall body of evidence on how testosterone affects performance, but was narrowly focused.

“They looked at very specific markers and what they’re showing is that this is not the mechanism by which testosterone improves performance,” he said. “That may be so, but it doesn’t negate the finding that testosterone improves endurance and has other vascular effects: it increases capillarity, increases blood flow to the tissues, and improves myocardial function.”

Although well done, the study doesn’t get at the larger question of whether testosterone increases cardiovascular risk, observed Dr. Bhasin. “None of the randomized studies have been large enough or long enough to determine the effect on cardiovascular events rates. There’s a lot of argument on both sides but we need some data to address that.”

The 6,000-patient TRAVERSE trial is specifically looking at long-term major cardiovascular events with topical testosterone, compared with placebo, in hypogonadal men aged 45-80 years age who have evidence of or are at increased risk for CVD. The study, which is set to be completed in April 2022, should also provide information on fracture risk in these men, said Dr. Bhasin, one of the trial’s principal investigators and lead author of the Endocrine Society’s 2018 clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for hypogonadism in men.

William Evans, MD, adjunct professor of human nutrition, University of California, Berkley, said in an interview that the positive effects of testosterone occur at much lower doses in men and women who are hypogonadal but, in this particular population, exercise is the key and the major recommendation.

“Testosterone has been overprescribed and overadvertised for essentially a lifetime of sedentary living, and it’s advertised as a way to get all that back without having to work for it,” he said. “Exercise has a profound and positive effect on control of blood pressure, function, and strength, and testosterone may only affect in people who are sick, people who have really low levels.”

The study was funded by the Heart Foundation of Australia. Lawley Pharmaceuticals provided the study medication and placebo. Dr. Yeap has received speaker honoraria and conference support from Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Besins Healthcare; research support from Bayer, Lily, and Lawley; and served as an adviser for Lily, Besins Healthcare, Ferring, and Lawley. Dr. Shalender reports consultation or advisement for GTx, Pfizer, and TAP; grant or other research support from Solvay and GlaxoSmithKline; and honoraria from Solvay and Auxilium. Dr. Evans reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exercise training – but not testosterone therapy – improved vascular health in aging men with widening midsections and low to normal testosterone, new research suggests.

“Previous studies have suggested that men with higher levels of testosterone, who were more physically active, might have better health outcomes,” Bu Beng Yeap, MBBS, PhD, University of Western Australia, Perth, said in an interview. “We formulated the hypothesis that the combination of testosterone treatment and exercise training would improve the health of arteries more than either alone.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators randomly assigned 80 men, aged 50-70 years, to 12 weeks of 5% testosterone cream 2 mL applied daily or placebo plus a supervised exercise program that included machine-based resistance and aerobic (cycling) exercises two to three times a week or no additional exercise.

The men (mean age, 59 years) had low-normal testosterone (6-14 nmol/L), a waist circumference of at least 95 cm (37.4 inches), and no known cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 1 diabetes, or other clinically significant illnesses. Current smokers and men on testosterone or medications that would alter testosterone levels were also excluded.

High-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery was used to assess flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) responses. FMD has been shown to be predictive of CVD risk, with a 1% increase in FMD associated with a 9%-13% decrease in future CVD events.

Based on participants’ daily dairies, testosterone adherence was 97.6%. Exercise adherence was 96.5% for twice-weekly attendance and 80.0% for thrice-weekly attendance, with no between-group differences.

As reported Feb. 22, 2021, in Hypertension, testosterone levels increased, on average, 3.0 nmol/L in both testosterone groups by week 12 (P = .003). In all, 62% of these men had levels of the hormone exceeding 14 nmol/L, compared with 29% of those receiving placebo.

Testosterone levels improved with exercise training plus placebo by 0.9 nmol/L, but fell with no exercise and placebo by 0.9 nmol/L.

In terms of vascular function, exercise training increased FMD when expressed as both the delta change (mm; P = .004) and relative rise from baseline diameter (%; P = .033).

There was no effect of exercise on GTN%, which is generally in line with exercise literature indicating that shear-mediated adaptations in response to episodic exercise occur largely in endothelial cells, the authors noted.

Testosterone did not affect any measures of FMD nor was there an effect on GTN response, despite previous evidence that lower testosterone doses might enhance smooth muscle function.

“Our main finding was that testosterone – at this dose over this duration of treatment – did not have a beneficial effect on artery health, nor did it enhance the effect of exercise,” said Dr. Yeap, who is also president of the Endocrine Society of Australia. “For middle-aged and older men wanting to improve the health of their arteries, exercise is better than testosterone!”

Shalender Bhasin, MBBS, director of research programs in men’s health, aging, and metabolism at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study is interesting from a mechanistic perspective and adds to the overall body of evidence on how testosterone affects performance, but was narrowly focused.

“They looked at very specific markers and what they’re showing is that this is not the mechanism by which testosterone improves performance,” he said. “That may be so, but it doesn’t negate the finding that testosterone improves endurance and has other vascular effects: it increases capillarity, increases blood flow to the tissues, and improves myocardial function.”

Although well done, the study doesn’t get at the larger question of whether testosterone increases cardiovascular risk, observed Dr. Bhasin. “None of the randomized studies have been large enough or long enough to determine the effect on cardiovascular events rates. There’s a lot of argument on both sides but we need some data to address that.”

The 6,000-patient TRAVERSE trial is specifically looking at long-term major cardiovascular events with topical testosterone, compared with placebo, in hypogonadal men aged 45-80 years age who have evidence of or are at increased risk for CVD. The study, which is set to be completed in April 2022, should also provide information on fracture risk in these men, said Dr. Bhasin, one of the trial’s principal investigators and lead author of the Endocrine Society’s 2018 clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for hypogonadism in men.

William Evans, MD, adjunct professor of human nutrition, University of California, Berkley, said in an interview that the positive effects of testosterone occur at much lower doses in men and women who are hypogonadal but, in this particular population, exercise is the key and the major recommendation.

“Testosterone has been overprescribed and overadvertised for essentially a lifetime of sedentary living, and it’s advertised as a way to get all that back without having to work for it,” he said. “Exercise has a profound and positive effect on control of blood pressure, function, and strength, and testosterone may only affect in people who are sick, people who have really low levels.”

The study was funded by the Heart Foundation of Australia. Lawley Pharmaceuticals provided the study medication and placebo. Dr. Yeap has received speaker honoraria and conference support from Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Besins Healthcare; research support from Bayer, Lily, and Lawley; and served as an adviser for Lily, Besins Healthcare, Ferring, and Lawley. Dr. Shalender reports consultation or advisement for GTx, Pfizer, and TAP; grant or other research support from Solvay and GlaxoSmithKline; and honoraria from Solvay and Auxilium. Dr. Evans reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exercise training – but not testosterone therapy – improved vascular health in aging men with widening midsections and low to normal testosterone, new research suggests.

“Previous studies have suggested that men with higher levels of testosterone, who were more physically active, might have better health outcomes,” Bu Beng Yeap, MBBS, PhD, University of Western Australia, Perth, said in an interview. “We formulated the hypothesis that the combination of testosterone treatment and exercise training would improve the health of arteries more than either alone.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators randomly assigned 80 men, aged 50-70 years, to 12 weeks of 5% testosterone cream 2 mL applied daily or placebo plus a supervised exercise program that included machine-based resistance and aerobic (cycling) exercises two to three times a week or no additional exercise.

The men (mean age, 59 years) had low-normal testosterone (6-14 nmol/L), a waist circumference of at least 95 cm (37.4 inches), and no known cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 1 diabetes, or other clinically significant illnesses. Current smokers and men on testosterone or medications that would alter testosterone levels were also excluded.

High-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery was used to assess flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) responses. FMD has been shown to be predictive of CVD risk, with a 1% increase in FMD associated with a 9%-13% decrease in future CVD events.

Based on participants’ daily dairies, testosterone adherence was 97.6%. Exercise adherence was 96.5% for twice-weekly attendance and 80.0% for thrice-weekly attendance, with no between-group differences.

As reported Feb. 22, 2021, in Hypertension, testosterone levels increased, on average, 3.0 nmol/L in both testosterone groups by week 12 (P = .003). In all, 62% of these men had levels of the hormone exceeding 14 nmol/L, compared with 29% of those receiving placebo.

Testosterone levels improved with exercise training plus placebo by 0.9 nmol/L, but fell with no exercise and placebo by 0.9 nmol/L.

In terms of vascular function, exercise training increased FMD when expressed as both the delta change (mm; P = .004) and relative rise from baseline diameter (%; P = .033).

There was no effect of exercise on GTN%, which is generally in line with exercise literature indicating that shear-mediated adaptations in response to episodic exercise occur largely in endothelial cells, the authors noted.

Testosterone did not affect any measures of FMD nor was there an effect on GTN response, despite previous evidence that lower testosterone doses might enhance smooth muscle function.

“Our main finding was that testosterone – at this dose over this duration of treatment – did not have a beneficial effect on artery health, nor did it enhance the effect of exercise,” said Dr. Yeap, who is also president of the Endocrine Society of Australia. “For middle-aged and older men wanting to improve the health of their arteries, exercise is better than testosterone!”

Shalender Bhasin, MBBS, director of research programs in men’s health, aging, and metabolism at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study is interesting from a mechanistic perspective and adds to the overall body of evidence on how testosterone affects performance, but was narrowly focused.

“They looked at very specific markers and what they’re showing is that this is not the mechanism by which testosterone improves performance,” he said. “That may be so, but it doesn’t negate the finding that testosterone improves endurance and has other vascular effects: it increases capillarity, increases blood flow to the tissues, and improves myocardial function.”

Although well done, the study doesn’t get at the larger question of whether testosterone increases cardiovascular risk, observed Dr. Bhasin. “None of the randomized studies have been large enough or long enough to determine the effect on cardiovascular events rates. There’s a lot of argument on both sides but we need some data to address that.”

The 6,000-patient TRAVERSE trial is specifically looking at long-term major cardiovascular events with topical testosterone, compared with placebo, in hypogonadal men aged 45-80 years age who have evidence of or are at increased risk for CVD. The study, which is set to be completed in April 2022, should also provide information on fracture risk in these men, said Dr. Bhasin, one of the trial’s principal investigators and lead author of the Endocrine Society’s 2018 clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for hypogonadism in men.

William Evans, MD, adjunct professor of human nutrition, University of California, Berkley, said in an interview that the positive effects of testosterone occur at much lower doses in men and women who are hypogonadal but, in this particular population, exercise is the key and the major recommendation.

“Testosterone has been overprescribed and overadvertised for essentially a lifetime of sedentary living, and it’s advertised as a way to get all that back without having to work for it,” he said. “Exercise has a profound and positive effect on control of blood pressure, function, and strength, and testosterone may only affect in people who are sick, people who have really low levels.”

The study was funded by the Heart Foundation of Australia. Lawley Pharmaceuticals provided the study medication and placebo. Dr. Yeap has received speaker honoraria and conference support from Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Besins Healthcare; research support from Bayer, Lily, and Lawley; and served as an adviser for Lily, Besins Healthcare, Ferring, and Lawley. Dr. Shalender reports consultation or advisement for GTx, Pfizer, and TAP; grant or other research support from Solvay and GlaxoSmithKline; and honoraria from Solvay and Auxilium. Dr. Evans reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ivabradine knocks down heart rate, symptoms in POTS

The heart failure drug ivabradine (Corlanor) can provide relief from the elevated heart rate and often debilitating symptoms associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a new study suggests.

Ivabradine significantly lowered standing heart rate, compared with placebo (77.9 vs. 94.2 beats/min; P < .001). The typical surge in heart rate that occurs upon standing in these patients was also blunted, compared with baseline (13.0 vs. 21.4 beats/min; P = .001).

“There are really not a lot of great options for patients with POTS and, mechanistically, ivabradine just make sense because it’s a drug that lowers heart rate very selectively and doesn’t lower blood pressure,” lead study author Pam R. Taub, MD, told this news organization.

Surprisingly, the reduction in heart rate translated into improved physical (P = .008) and social (P = .021) functioning after just 1 month of ivabradine, without any other background POTS medications or a change in nonpharmacologic therapies, she said. “What’s really nice to see is when you tackle a really significant part of the disease, which is the elevated heart rate, just how much better they feel.”

POTS patients are mostly healthy, active young women, who after some inciting event – such as viral infection, trauma, or surgery – experience an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min upon standing accompanied by a range of symptoms, including dizziness, palpitations, brain fog, and fatigue.

A COVID connection?

The study enrolled patients with hyperadrenergic POTS as the predominant subtype, but another group to keep in mind that might benefit is the post-COVID POTS patient, said Dr. Taub, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We’re seeing an incredible number of patients post COVID that meet the criteria for POTS, and a lot of these patients also have COVID fatigue,” she said. “So clinically, myself and many other cardiologists who understand ivabradine have been using it off-label for the COVID patients, as long as they meet the criteria. You don’t want to use it in every COVID patient, but if someone’s predominant complaint is that their heart rate is going up when they’re standing and they’re debilitated by it, this is a drug to consider.”

Anecdotal findings in patients with long-hauler COVID need to be translated into rigorous research protocols, but mechanistically, whether it’s POTS from COVID or from another type of infection – like Lyme disease or some other viral syndrome – it should work the same, Dr. Taub said. “POTS is POTS.”

There are no first-line drugs for POTS, and current class IIb recommendations include midodrine, which increases blood pressure and can make people feel awful, and fludrocortisone, which can cause a lot of weight gain and fluid retention, she observed. Other agents that lower heart rate, like beta-blockers, also lower blood pressure and can aggravate depression and fatigue.

Ivabradine regulates heart rate by specifically blocking the Ifunny channel of the sinoatrial node. It was approved in 2015 in the United States to reduce hospitalizations in patients with systolic heart failure, and it also has a second class IIb recommendation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia.

The present study, reported in the Feb. 23 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first randomized clinical trial using ivabradine to treat POTS.

A total of 26 patients with POTS were started on ivabradine 5 mg or placebo twice daily for 1 month, then were crossed over to the other treatment for 1 month after a 1-week washout period. Six patients were started on a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose. Doses were adjusted during the study based on the patient’s heart rate response and tolerance. Patients had seven clinic visits in which norepinephrine (NE) levels were measured and head-up tilt testing conducted.

Four patients in the ivabradine arm withdrew because of adverse effects, and one withdrew during crossover.

Among the 22 patients who completed the study, exploratory analyses showed a strong trend for greater reduction in plasma NE upon standing with ivabradine (P = .056). The effect was also more profound in patients with very high baseline standing NE levels (at least 1,000 pg/mL) than in those with lower NE levels (600 to 1,000 pg/mL).

“It makes sense because that means their sympathetic nervous system is more overactive; they have a higher heart rate,” Dr. Taub said. “So it’s a potential clinical tool that people can use in their practice to determine, ‘okay, is this a patient I should be considering ivabradine on?’ ”

Although the present study had only 22 patients, “it should definitely be looked at as a step forward, both in terms of ivabradine specifically and in terms of setting the standard for the types of studies we want to see in our patients,” Satish R. Raj, MD, MSCI, University of Calgary (Alta.), said in an interview.

In a related editorial, however, Dr. Raj and coauthor Robert S. Sheldon, MD, PhD, also from the University of Calgary, point out that the standing heart rate in the placebo phase was only 94 beats/min, “suggesting that these patients may be affected only mildly by their POTS.”

Asked about the point, Dr. Taub said: “I don’t know if I agree with that.” She noted that the diagnosis of POTS was confirmed by tilt-table testing and NE levels and that patients’ symptoms vary from day to day. “The standard deviation was plus or minus 16.8, so there’s variability.”

Both Dr. Raj and Dr. Taub said they expect the results will be included in the next scientific statement for POTS, but in the meantime, it may be a struggle to get the drug covered by insurance.

“The challenge is that this is a very off-label use for this medication, and the medication’s not cheap,” Dr. Raj observed. The price for 60 tablets, which is about a 1-month supply, is $485 on GoodRx.

Another question going forward, he said, is whether ivabradine is superior to beta-blockers, which will be studied in a 20-patient crossover trial sponsored by the University of Calgary that is about to launch. The primary completion date is set for 2024.

The study was supported by a grant from Amgen. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA. Dr. Raj has received a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and research grants from Dysautonomia International to address the pathophysiology of POTS. Dr. Sheldon has received a research grant from Dysautonomia International for a clinical trial assessing ivabradine and propranolol for the treatment of POTS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The heart failure drug ivabradine (Corlanor) can provide relief from the elevated heart rate and often debilitating symptoms associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a new study suggests.

Ivabradine significantly lowered standing heart rate, compared with placebo (77.9 vs. 94.2 beats/min; P < .001). The typical surge in heart rate that occurs upon standing in these patients was also blunted, compared with baseline (13.0 vs. 21.4 beats/min; P = .001).

“There are really not a lot of great options for patients with POTS and, mechanistically, ivabradine just make sense because it’s a drug that lowers heart rate very selectively and doesn’t lower blood pressure,” lead study author Pam R. Taub, MD, told this news organization.

Surprisingly, the reduction in heart rate translated into improved physical (P = .008) and social (P = .021) functioning after just 1 month of ivabradine, without any other background POTS medications or a change in nonpharmacologic therapies, she said. “What’s really nice to see is when you tackle a really significant part of the disease, which is the elevated heart rate, just how much better they feel.”

POTS patients are mostly healthy, active young women, who after some inciting event – such as viral infection, trauma, or surgery – experience an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min upon standing accompanied by a range of symptoms, including dizziness, palpitations, brain fog, and fatigue.

A COVID connection?

The study enrolled patients with hyperadrenergic POTS as the predominant subtype, but another group to keep in mind that might benefit is the post-COVID POTS patient, said Dr. Taub, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We’re seeing an incredible number of patients post COVID that meet the criteria for POTS, and a lot of these patients also have COVID fatigue,” she said. “So clinically, myself and many other cardiologists who understand ivabradine have been using it off-label for the COVID patients, as long as they meet the criteria. You don’t want to use it in every COVID patient, but if someone’s predominant complaint is that their heart rate is going up when they’re standing and they’re debilitated by it, this is a drug to consider.”

Anecdotal findings in patients with long-hauler COVID need to be translated into rigorous research protocols, but mechanistically, whether it’s POTS from COVID or from another type of infection – like Lyme disease or some other viral syndrome – it should work the same, Dr. Taub said. “POTS is POTS.”

There are no first-line drugs for POTS, and current class IIb recommendations include midodrine, which increases blood pressure and can make people feel awful, and fludrocortisone, which can cause a lot of weight gain and fluid retention, she observed. Other agents that lower heart rate, like beta-blockers, also lower blood pressure and can aggravate depression and fatigue.

Ivabradine regulates heart rate by specifically blocking the Ifunny channel of the sinoatrial node. It was approved in 2015 in the United States to reduce hospitalizations in patients with systolic heart failure, and it also has a second class IIb recommendation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia.

The present study, reported in the Feb. 23 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first randomized clinical trial using ivabradine to treat POTS.

A total of 26 patients with POTS were started on ivabradine 5 mg or placebo twice daily for 1 month, then were crossed over to the other treatment for 1 month after a 1-week washout period. Six patients were started on a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose. Doses were adjusted during the study based on the patient’s heart rate response and tolerance. Patients had seven clinic visits in which norepinephrine (NE) levels were measured and head-up tilt testing conducted.

Four patients in the ivabradine arm withdrew because of adverse effects, and one withdrew during crossover.

Among the 22 patients who completed the study, exploratory analyses showed a strong trend for greater reduction in plasma NE upon standing with ivabradine (P = .056). The effect was also more profound in patients with very high baseline standing NE levels (at least 1,000 pg/mL) than in those with lower NE levels (600 to 1,000 pg/mL).

“It makes sense because that means their sympathetic nervous system is more overactive; they have a higher heart rate,” Dr. Taub said. “So it’s a potential clinical tool that people can use in their practice to determine, ‘okay, is this a patient I should be considering ivabradine on?’ ”

Although the present study had only 22 patients, “it should definitely be looked at as a step forward, both in terms of ivabradine specifically and in terms of setting the standard for the types of studies we want to see in our patients,” Satish R. Raj, MD, MSCI, University of Calgary (Alta.), said in an interview.

In a related editorial, however, Dr. Raj and coauthor Robert S. Sheldon, MD, PhD, also from the University of Calgary, point out that the standing heart rate in the placebo phase was only 94 beats/min, “suggesting that these patients may be affected only mildly by their POTS.”

Asked about the point, Dr. Taub said: “I don’t know if I agree with that.” She noted that the diagnosis of POTS was confirmed by tilt-table testing and NE levels and that patients’ symptoms vary from day to day. “The standard deviation was plus or minus 16.8, so there’s variability.”

Both Dr. Raj and Dr. Taub said they expect the results will be included in the next scientific statement for POTS, but in the meantime, it may be a struggle to get the drug covered by insurance.

“The challenge is that this is a very off-label use for this medication, and the medication’s not cheap,” Dr. Raj observed. The price for 60 tablets, which is about a 1-month supply, is $485 on GoodRx.

Another question going forward, he said, is whether ivabradine is superior to beta-blockers, which will be studied in a 20-patient crossover trial sponsored by the University of Calgary that is about to launch. The primary completion date is set for 2024.

The study was supported by a grant from Amgen. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA. Dr. Raj has received a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and research grants from Dysautonomia International to address the pathophysiology of POTS. Dr. Sheldon has received a research grant from Dysautonomia International for a clinical trial assessing ivabradine and propranolol for the treatment of POTS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The heart failure drug ivabradine (Corlanor) can provide relief from the elevated heart rate and often debilitating symptoms associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a new study suggests.

Ivabradine significantly lowered standing heart rate, compared with placebo (77.9 vs. 94.2 beats/min; P < .001). The typical surge in heart rate that occurs upon standing in these patients was also blunted, compared with baseline (13.0 vs. 21.4 beats/min; P = .001).

“There are really not a lot of great options for patients with POTS and, mechanistically, ivabradine just make sense because it’s a drug that lowers heart rate very selectively and doesn’t lower blood pressure,” lead study author Pam R. Taub, MD, told this news organization.

Surprisingly, the reduction in heart rate translated into improved physical (P = .008) and social (P = .021) functioning after just 1 month of ivabradine, without any other background POTS medications or a change in nonpharmacologic therapies, she said. “What’s really nice to see is when you tackle a really significant part of the disease, which is the elevated heart rate, just how much better they feel.”

POTS patients are mostly healthy, active young women, who after some inciting event – such as viral infection, trauma, or surgery – experience an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min upon standing accompanied by a range of symptoms, including dizziness, palpitations, brain fog, and fatigue.

A COVID connection?

The study enrolled patients with hyperadrenergic POTS as the predominant subtype, but another group to keep in mind that might benefit is the post-COVID POTS patient, said Dr. Taub, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We’re seeing an incredible number of patients post COVID that meet the criteria for POTS, and a lot of these patients also have COVID fatigue,” she said. “So clinically, myself and many other cardiologists who understand ivabradine have been using it off-label for the COVID patients, as long as they meet the criteria. You don’t want to use it in every COVID patient, but if someone’s predominant complaint is that their heart rate is going up when they’re standing and they’re debilitated by it, this is a drug to consider.”

Anecdotal findings in patients with long-hauler COVID need to be translated into rigorous research protocols, but mechanistically, whether it’s POTS from COVID or from another type of infection – like Lyme disease or some other viral syndrome – it should work the same, Dr. Taub said. “POTS is POTS.”

There are no first-line drugs for POTS, and current class IIb recommendations include midodrine, which increases blood pressure and can make people feel awful, and fludrocortisone, which can cause a lot of weight gain and fluid retention, she observed. Other agents that lower heart rate, like beta-blockers, also lower blood pressure and can aggravate depression and fatigue.

Ivabradine regulates heart rate by specifically blocking the Ifunny channel of the sinoatrial node. It was approved in 2015 in the United States to reduce hospitalizations in patients with systolic heart failure, and it also has a second class IIb recommendation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia.

The present study, reported in the Feb. 23 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first randomized clinical trial using ivabradine to treat POTS.

A total of 26 patients with POTS were started on ivabradine 5 mg or placebo twice daily for 1 month, then were crossed over to the other treatment for 1 month after a 1-week washout period. Six patients were started on a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose. Doses were adjusted during the study based on the patient’s heart rate response and tolerance. Patients had seven clinic visits in which norepinephrine (NE) levels were measured and head-up tilt testing conducted.

Four patients in the ivabradine arm withdrew because of adverse effects, and one withdrew during crossover.

Among the 22 patients who completed the study, exploratory analyses showed a strong trend for greater reduction in plasma NE upon standing with ivabradine (P = .056). The effect was also more profound in patients with very high baseline standing NE levels (at least 1,000 pg/mL) than in those with lower NE levels (600 to 1,000 pg/mL).

“It makes sense because that means their sympathetic nervous system is more overactive; they have a higher heart rate,” Dr. Taub said. “So it’s a potential clinical tool that people can use in their practice to determine, ‘okay, is this a patient I should be considering ivabradine on?’ ”

Although the present study had only 22 patients, “it should definitely be looked at as a step forward, both in terms of ivabradine specifically and in terms of setting the standard for the types of studies we want to see in our patients,” Satish R. Raj, MD, MSCI, University of Calgary (Alta.), said in an interview.

In a related editorial, however, Dr. Raj and coauthor Robert S. Sheldon, MD, PhD, also from the University of Calgary, point out that the standing heart rate in the placebo phase was only 94 beats/min, “suggesting that these patients may be affected only mildly by their POTS.”

Asked about the point, Dr. Taub said: “I don’t know if I agree with that.” She noted that the diagnosis of POTS was confirmed by tilt-table testing and NE levels and that patients’ symptoms vary from day to day. “The standard deviation was plus or minus 16.8, so there’s variability.”

Both Dr. Raj and Dr. Taub said they expect the results will be included in the next scientific statement for POTS, but in the meantime, it may be a struggle to get the drug covered by insurance.

“The challenge is that this is a very off-label use for this medication, and the medication’s not cheap,” Dr. Raj observed. The price for 60 tablets, which is about a 1-month supply, is $485 on GoodRx.

Another question going forward, he said, is whether ivabradine is superior to beta-blockers, which will be studied in a 20-patient crossover trial sponsored by the University of Calgary that is about to launch. The primary completion date is set for 2024.

The study was supported by a grant from Amgen. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA. Dr. Raj has received a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and research grants from Dysautonomia International to address the pathophysiology of POTS. Dr. Sheldon has received a research grant from Dysautonomia International for a clinical trial assessing ivabradine and propranolol for the treatment of POTS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More Americans hospitalized, readmitted for heart failure

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ColCORONA: More questions than answers for colchicine in COVID-19

Science by press release and preprint has cooled clinician enthusiasm for the use of colchicine in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19, despite a pressing need for early treatments.

As previously reported by this news organization, a Jan. 22 press release announced that the massive ColCORONA study missed its primary endpoint of hospitalization or death among 4,488 newly diagnosed patients at increased risk for hospitalization.

But it also touted that use of the anti-inflammatory drug significantly reduced the primary endpoint in 4,159 of those patients with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID and led to reductions of 25%, 50%, and 44%, respectively, for hospitalizations, ventilations, and death.

Lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, director of the Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, deemed the findings a “medical breakthrough.”

When the preprint released a few days later, however, newly revealed confidence intervals showed colchicine did not meaningfully reduce the need for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-1.07) or death alone (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.19-1.66).

Further, the significant benefit on the primary outcome came at the cost of a fivefold increase in pulmonary embolism (11 vs. 2; P = .01), which was not mentioned in the press release.

“Whether this represents a real phenomenon or simply the play of chance is not known,” Dr. Tardif and colleagues noted later in the preprint.

“I read the preprint on colchicine and I have so many questions,” Aaron E. Glatt, MD, spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Hewlett, N.Y., said in an interview. “I’ve been burned too many times with COVID and prefer to see better data.

“People sometimes say if you wait for perfect data, people are going to die,” he said. “Yeah, but we have no idea if people are going to die from getting this drug more than not getting it. That’s what concerns me. How many pulmonary emboli are going to be fatal versus the slight benefit that the study showed?”

The pushback to the non–peer-reviewed data on social media and via emails was so strong that Dr. Tardif posted a nearly 2,000-word letter responding to the many questions at play.

Chief among them was why the trial, originally planned for 6,000 patients, was stopped early by the investigators without consultation with the data safety monitoring board (DSMB).

The explanation in the letter that logistical issues like running the study call center, budget constraints, and a perceived need to quickly communicate the results left some calling foul that the study wasn’t allowed to finish and come to a more definitive conclusion.

“I can be a little bit sympathetic to their cause but at the same time the DSMB should have said no,” said David Boulware, MD, MPH, who led a recent hydroxychloroquine trial in COVID-19. “The problem is we’re sort of left in limbo, where some people kind of believe it and some say it’s not really a thing. So it’s not really moving the needle, as far as guidelines go.”

Indeed, a Twitter poll by cardiologist James Januzzi Jr., MD, captured the uncertainty, with 28% of respondents saying the trial was “neutral,” 58% saying “maybe but meh,” and 14% saying “colchicine for all.”

Another poll cheekily asked whether ColCORONA was the Gamestop/Reddit equivalent of COVID.

“The press release really didn’t help things because it very much oversold the effect. That, I think, poisoned the well,” said Dr. Boulware, professor of medicine in infectious diseases at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“The question I’m left with is not whether colchicine works, but who does it work in,” he said. “That’s really the fundamental question because it does seem that there are probably high-risk groups in their trial and others where they benefit, whereas other groups don’t benefit. In the subgroup analysis, there was absolutely no beneficial effect in women.”

According to the authors, the number needed to treat to prevent one death or hospitalization was 71 overall, but 29 for patients with diabetes, 31 for those aged 70 years and older, 53 for patients with respiratory disease, and 25 for those with coronary disease or heart failure.

Men are at higher risk overall for poor outcomes. But “the authors didn’t present a multivariable analysis, so it is unclear if another factor, such as a differential prevalence of smoking or cardiovascular risk factors, contributed to the differential benefit,” Rachel Bender Ignacio, MD, MPH, infectious disease specialist, University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Importantly, in this pragmatic study, duration and severity of symptoms were not reported, observed Dr. Bender Ignacio, who is also a STOP-COVID-2 investigator. “We don’t yet have data as to whether colchicine shortens duration or severity of symptoms or prevents long COVID, so we need more data on that.”

The overall risk for serious adverse events was lower in the colchicine group, but the difference in pulmonary embolism (PE) was striking, she said. This could be caused by a real biologic effect, or it’s possible that persons with shortness of breath and hypoxia, without evident viral pneumonia on chest x-ray after a positive COVID-19 test, were more likely to receive a CT-PE study.

The press release also failed to include information, later noted in the preprint, that the MHI has submitted two patents related to colchicine: “Methods of treating a coronavirus infection using colchicine” and “Early administration of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction.”

Reached for clarification, MHI communications adviser Camille Turbide said in an interview that the first patent “simply refers to the novel concept of preventing complications of COVID-19, such as admission to the hospital, with colchicine as tested in the ColCORONA study.”

The second patent, she said, refers to the “novel concept that administering colchicine early after a major adverse cardiovascular event is better than waiting several days,” as supported by the COLCOT study, which Dr. Tardif also led.

The patents are being reviewed by authorities and “Dr. Tardif has waived his rights in these patents and does not stand to benefit financially at all if colchicine becomes used as a treatment for COVID-19,” Ms. Turbide said.

Dr. Tardif did not respond to interview requests for this story. Dr. Glatt said conflicts of interest must be assessed and are “something that is of great concern in any scientific study.”

Cardiologist Steve Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said in an interview that, “despite the negative results, the study does suggest that colchicine might have a benefit and should be studied in future trials. These findings are not sufficient evidence to suggest use of the drug in patients infected with COVID-19.”

He noted that adverse effects like diarrhea were expected but that the excess PE was unexpected and needs greater clarification.

“Stopping the trial for administrative reasons is puzzling and undermined the ability of the trial to give a reliable answer,” Dr. Nissen said. “This is a reasonable pilot study that should be viewed as hypothesis generating but inconclusive.”

Several sources said a new trial is unlikely, particularly given the cost and 28 trials already evaluating colchicine. Among these are RECOVERY and COLCOVID, testing whether colchicine can reduce the duration of hospitalization or death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Because there are so many trials ongoing right now, including for antivirals and other immunomodulators, it’s important that, if colchicine comes to routine clinical use, it provides access to treatment for those not able or willing to access clinical trials, rather than impeding clinical trial enrollment, Dr. Bender Ignacio suggested.

“We have already learned the lesson in the pandemic that early adoption of potentially promising therapies can negatively impact our ability to study and develop other promising treatments,” she said.

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais, and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators. Dr. Glatt reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Boulware reported receiving $18 in food and beverages from Gilead Sciences in 2018.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Science by press release and preprint has cooled clinician enthusiasm for the use of colchicine in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19, despite a pressing need for early treatments.

As previously reported by this news organization, a Jan. 22 press release announced that the massive ColCORONA study missed its primary endpoint of hospitalization or death among 4,488 newly diagnosed patients at increased risk for hospitalization.

But it also touted that use of the anti-inflammatory drug significantly reduced the primary endpoint in 4,159 of those patients with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID and led to reductions of 25%, 50%, and 44%, respectively, for hospitalizations, ventilations, and death.

Lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, director of the Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, deemed the findings a “medical breakthrough.”

When the preprint released a few days later, however, newly revealed confidence intervals showed colchicine did not meaningfully reduce the need for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-1.07) or death alone (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.19-1.66).

Further, the significant benefit on the primary outcome came at the cost of a fivefold increase in pulmonary embolism (11 vs. 2; P = .01), which was not mentioned in the press release.

“Whether this represents a real phenomenon or simply the play of chance is not known,” Dr. Tardif and colleagues noted later in the preprint.

“I read the preprint on colchicine and I have so many questions,” Aaron E. Glatt, MD, spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Hewlett, N.Y., said in an interview. “I’ve been burned too many times with COVID and prefer to see better data.

“People sometimes say if you wait for perfect data, people are going to die,” he said. “Yeah, but we have no idea if people are going to die from getting this drug more than not getting it. That’s what concerns me. How many pulmonary emboli are going to be fatal versus the slight benefit that the study showed?”

The pushback to the non–peer-reviewed data on social media and via emails was so strong that Dr. Tardif posted a nearly 2,000-word letter responding to the many questions at play.

Chief among them was why the trial, originally planned for 6,000 patients, was stopped early by the investigators without consultation with the data safety monitoring board (DSMB).

The explanation in the letter that logistical issues like running the study call center, budget constraints, and a perceived need to quickly communicate the results left some calling foul that the study wasn’t allowed to finish and come to a more definitive conclusion.

“I can be a little bit sympathetic to their cause but at the same time the DSMB should have said no,” said David Boulware, MD, MPH, who led a recent hydroxychloroquine trial in COVID-19. “The problem is we’re sort of left in limbo, where some people kind of believe it and some say it’s not really a thing. So it’s not really moving the needle, as far as guidelines go.”

Indeed, a Twitter poll by cardiologist James Januzzi Jr., MD, captured the uncertainty, with 28% of respondents saying the trial was “neutral,” 58% saying “maybe but meh,” and 14% saying “colchicine for all.”

Another poll cheekily asked whether ColCORONA was the Gamestop/Reddit equivalent of COVID.

“The press release really didn’t help things because it very much oversold the effect. That, I think, poisoned the well,” said Dr. Boulware, professor of medicine in infectious diseases at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“The question I’m left with is not whether colchicine works, but who does it work in,” he said. “That’s really the fundamental question because it does seem that there are probably high-risk groups in their trial and others where they benefit, whereas other groups don’t benefit. In the subgroup analysis, there was absolutely no beneficial effect in women.”

According to the authors, the number needed to treat to prevent one death or hospitalization was 71 overall, but 29 for patients with diabetes, 31 for those aged 70 years and older, 53 for patients with respiratory disease, and 25 for those with coronary disease or heart failure.

Men are at higher risk overall for poor outcomes. But “the authors didn’t present a multivariable analysis, so it is unclear if another factor, such as a differential prevalence of smoking or cardiovascular risk factors, contributed to the differential benefit,” Rachel Bender Ignacio, MD, MPH, infectious disease specialist, University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Importantly, in this pragmatic study, duration and severity of symptoms were not reported, observed Dr. Bender Ignacio, who is also a STOP-COVID-2 investigator. “We don’t yet have data as to whether colchicine shortens duration or severity of symptoms or prevents long COVID, so we need more data on that.”

The overall risk for serious adverse events was lower in the colchicine group, but the difference in pulmonary embolism (PE) was striking, she said. This could be caused by a real biologic effect, or it’s possible that persons with shortness of breath and hypoxia, without evident viral pneumonia on chest x-ray after a positive COVID-19 test, were more likely to receive a CT-PE study.

The press release also failed to include information, later noted in the preprint, that the MHI has submitted two patents related to colchicine: “Methods of treating a coronavirus infection using colchicine” and “Early administration of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction.”

Reached for clarification, MHI communications adviser Camille Turbide said in an interview that the first patent “simply refers to the novel concept of preventing complications of COVID-19, such as admission to the hospital, with colchicine as tested in the ColCORONA study.”

The second patent, she said, refers to the “novel concept that administering colchicine early after a major adverse cardiovascular event is better than waiting several days,” as supported by the COLCOT study, which Dr. Tardif also led.

The patents are being reviewed by authorities and “Dr. Tardif has waived his rights in these patents and does not stand to benefit financially at all if colchicine becomes used as a treatment for COVID-19,” Ms. Turbide said.

Dr. Tardif did not respond to interview requests for this story. Dr. Glatt said conflicts of interest must be assessed and are “something that is of great concern in any scientific study.”

Cardiologist Steve Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said in an interview that, “despite the negative results, the study does suggest that colchicine might have a benefit and should be studied in future trials. These findings are not sufficient evidence to suggest use of the drug in patients infected with COVID-19.”

He noted that adverse effects like diarrhea were expected but that the excess PE was unexpected and needs greater clarification.

“Stopping the trial for administrative reasons is puzzling and undermined the ability of the trial to give a reliable answer,” Dr. Nissen said. “This is a reasonable pilot study that should be viewed as hypothesis generating but inconclusive.”

Several sources said a new trial is unlikely, particularly given the cost and 28 trials already evaluating colchicine. Among these are RECOVERY and COLCOVID, testing whether colchicine can reduce the duration of hospitalization or death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Because there are so many trials ongoing right now, including for antivirals and other immunomodulators, it’s important that, if colchicine comes to routine clinical use, it provides access to treatment for those not able or willing to access clinical trials, rather than impeding clinical trial enrollment, Dr. Bender Ignacio suggested.

“We have already learned the lesson in the pandemic that early adoption of potentially promising therapies can negatively impact our ability to study and develop other promising treatments,” she said.

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais, and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators. Dr. Glatt reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Boulware reported receiving $18 in food and beverages from Gilead Sciences in 2018.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Science by press release and preprint has cooled clinician enthusiasm for the use of colchicine in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19, despite a pressing need for early treatments.

As previously reported by this news organization, a Jan. 22 press release announced that the massive ColCORONA study missed its primary endpoint of hospitalization or death among 4,488 newly diagnosed patients at increased risk for hospitalization.

But it also touted that use of the anti-inflammatory drug significantly reduced the primary endpoint in 4,159 of those patients with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID and led to reductions of 25%, 50%, and 44%, respectively, for hospitalizations, ventilations, and death.

Lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, director of the Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, deemed the findings a “medical breakthrough.”

When the preprint released a few days later, however, newly revealed confidence intervals showed colchicine did not meaningfully reduce the need for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-1.07) or death alone (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.19-1.66).

Further, the significant benefit on the primary outcome came at the cost of a fivefold increase in pulmonary embolism (11 vs. 2; P = .01), which was not mentioned in the press release.

“Whether this represents a real phenomenon or simply the play of chance is not known,” Dr. Tardif and colleagues noted later in the preprint.

“I read the preprint on colchicine and I have so many questions,” Aaron E. Glatt, MD, spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Hewlett, N.Y., said in an interview. “I’ve been burned too many times with COVID and prefer to see better data.

“People sometimes say if you wait for perfect data, people are going to die,” he said. “Yeah, but we have no idea if people are going to die from getting this drug more than not getting it. That’s what concerns me. How many pulmonary emboli are going to be fatal versus the slight benefit that the study showed?”

The pushback to the non–peer-reviewed data on social media and via emails was so strong that Dr. Tardif posted a nearly 2,000-word letter responding to the many questions at play.