User login

EHR Report: Don’t let the electronic health record do the driving

The secret to the care of the patient ... is in caring for the patient.

-Francis W. Peabody, MD1

Last month I received a call from a man who was upset about the way he was treated in our office. He had presented with depression and felt insulted by one of our resident physicians in the way he had interacted with him during his visit. I offered to see him the next day.

When I walked into the exam room, I noticed that his eyes were bloodshot and he was fidgeting in his chair. He explained that it was difficult for him to address this issue, but he had been taken aback at his previous visit to our office when the doctor who saw him, after introducing himself, proceeded to sit down, open his computer, and start typing. The patient went on to describe that the physician – while staring at his computer screen – first acknowledged that he was being seen for depression and then immediately asked him if he had any plans to commit suicide. He did not have any suicidal plans, but he felt strongly that being asked about suicide as the first question in the doctor’s interview missed the point of his visit. He was having trouble concentrating, he felt down, and he was having difficulty sleeping at night, all contributing to trouble both at work and in his personal life. Suicide was not a concern of his. He shook his head. He said he understood that we, as doctors, had to put information into the computer, but he also felt that the doctor’s main goal during that visit appeared to be to get through the forms on the computer rather than taking care of him. He admonished that physicians also need to remember that there is a patient in the room and that we should pay attention to the patient first. The computer should be second. I couldn’t have said it better myself. I told him that I would look into what happened, and then we continued with his visit.

You can already see where this discussion is going. The odd thing about the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), Medicare’s quality payment program, is that, unless we are careful, the result of the program may be the opposite of what it’s intended to accomplish. By leading to an over-focus on documentation of the quality of care, we are at risk of diminishing the quality of care itself. In essence, many of the requirements appear to simply be more advanced versions of the meaningful (meaningless?) use provisions with which we have previously grappled. It is clear that we should assess the quality of care that is given and that physician payment should be influenced by that care. It is also clear that the only reasonable way to measure the care provided is by collecting data from the EHR. The problem is that the sophistication of the EHR has not caught up to the sophistication of our goals.

Our challenge as physicians who care for patients therefore occurs at an individual level for each of us. How do we provide the necessary documentation scattered throughout our digital charts to satisfy reporting requirements, yet still meet the very real needs of patients to have their voices heard and their emotions acknowledged? The Physician Charter by the American Board of Internal Medicine discusses “the primacy of patient welfare” as a core tenant of medical practice. It goes on to state that “administrative exigencies must not compromise this principle.”2 Given competing demands, how do we continue to accomplish these goals which are often in conflict with one another?

We cannot provide an answer to this question because unfortunately – or perhaps fortunately – the answer does not come in the form of a clear algorithm of behaviors or a form that we can click on. However that does not mean that it cannot be done. Simply being mindful of how important personal interaction is to our patients will help us stay focused on patient needs. In fact, one of the most exciting aspects of our digital age (and our use of EHRs) is that the need to actually connect with people is more important than ever, and prioritizing this stands to reward those individuals who continue to pay attention to patients. In a future column, we will discuss suggestions and strategies for integrating the EHR into truly patient-centered care. In the early 1920s, Dr. Francis W. Peabody said, “The treatment of a disease may be entirely impersonal: the care of the patient must be completely personal.”1 Medical competency is essential and documentation is required, but neither alone is sufficient for the care of patients.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

References

1. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88:877-82.

2. The Physician Charter. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation at http://abimfoundation.org/what-we-do/physician-charter.

The secret to the care of the patient ... is in caring for the patient.

-Francis W. Peabody, MD1

Last month I received a call from a man who was upset about the way he was treated in our office. He had presented with depression and felt insulted by one of our resident physicians in the way he had interacted with him during his visit. I offered to see him the next day.

When I walked into the exam room, I noticed that his eyes were bloodshot and he was fidgeting in his chair. He explained that it was difficult for him to address this issue, but he had been taken aback at his previous visit to our office when the doctor who saw him, after introducing himself, proceeded to sit down, open his computer, and start typing. The patient went on to describe that the physician – while staring at his computer screen – first acknowledged that he was being seen for depression and then immediately asked him if he had any plans to commit suicide. He did not have any suicidal plans, but he felt strongly that being asked about suicide as the first question in the doctor’s interview missed the point of his visit. He was having trouble concentrating, he felt down, and he was having difficulty sleeping at night, all contributing to trouble both at work and in his personal life. Suicide was not a concern of his. He shook his head. He said he understood that we, as doctors, had to put information into the computer, but he also felt that the doctor’s main goal during that visit appeared to be to get through the forms on the computer rather than taking care of him. He admonished that physicians also need to remember that there is a patient in the room and that we should pay attention to the patient first. The computer should be second. I couldn’t have said it better myself. I told him that I would look into what happened, and then we continued with his visit.

You can already see where this discussion is going. The odd thing about the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), Medicare’s quality payment program, is that, unless we are careful, the result of the program may be the opposite of what it’s intended to accomplish. By leading to an over-focus on documentation of the quality of care, we are at risk of diminishing the quality of care itself. In essence, many of the requirements appear to simply be more advanced versions of the meaningful (meaningless?) use provisions with which we have previously grappled. It is clear that we should assess the quality of care that is given and that physician payment should be influenced by that care. It is also clear that the only reasonable way to measure the care provided is by collecting data from the EHR. The problem is that the sophistication of the EHR has not caught up to the sophistication of our goals.

Our challenge as physicians who care for patients therefore occurs at an individual level for each of us. How do we provide the necessary documentation scattered throughout our digital charts to satisfy reporting requirements, yet still meet the very real needs of patients to have their voices heard and their emotions acknowledged? The Physician Charter by the American Board of Internal Medicine discusses “the primacy of patient welfare” as a core tenant of medical practice. It goes on to state that “administrative exigencies must not compromise this principle.”2 Given competing demands, how do we continue to accomplish these goals which are often in conflict with one another?

We cannot provide an answer to this question because unfortunately – or perhaps fortunately – the answer does not come in the form of a clear algorithm of behaviors or a form that we can click on. However that does not mean that it cannot be done. Simply being mindful of how important personal interaction is to our patients will help us stay focused on patient needs. In fact, one of the most exciting aspects of our digital age (and our use of EHRs) is that the need to actually connect with people is more important than ever, and prioritizing this stands to reward those individuals who continue to pay attention to patients. In a future column, we will discuss suggestions and strategies for integrating the EHR into truly patient-centered care. In the early 1920s, Dr. Francis W. Peabody said, “The treatment of a disease may be entirely impersonal: the care of the patient must be completely personal.”1 Medical competency is essential and documentation is required, but neither alone is sufficient for the care of patients.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

References

1. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88:877-82.

2. The Physician Charter. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation at http://abimfoundation.org/what-we-do/physician-charter.

The secret to the care of the patient ... is in caring for the patient.

-Francis W. Peabody, MD1

Last month I received a call from a man who was upset about the way he was treated in our office. He had presented with depression and felt insulted by one of our resident physicians in the way he had interacted with him during his visit. I offered to see him the next day.

When I walked into the exam room, I noticed that his eyes were bloodshot and he was fidgeting in his chair. He explained that it was difficult for him to address this issue, but he had been taken aback at his previous visit to our office when the doctor who saw him, after introducing himself, proceeded to sit down, open his computer, and start typing. The patient went on to describe that the physician – while staring at his computer screen – first acknowledged that he was being seen for depression and then immediately asked him if he had any plans to commit suicide. He did not have any suicidal plans, but he felt strongly that being asked about suicide as the first question in the doctor’s interview missed the point of his visit. He was having trouble concentrating, he felt down, and he was having difficulty sleeping at night, all contributing to trouble both at work and in his personal life. Suicide was not a concern of his. He shook his head. He said he understood that we, as doctors, had to put information into the computer, but he also felt that the doctor’s main goal during that visit appeared to be to get through the forms on the computer rather than taking care of him. He admonished that physicians also need to remember that there is a patient in the room and that we should pay attention to the patient first. The computer should be second. I couldn’t have said it better myself. I told him that I would look into what happened, and then we continued with his visit.

You can already see where this discussion is going. The odd thing about the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), Medicare’s quality payment program, is that, unless we are careful, the result of the program may be the opposite of what it’s intended to accomplish. By leading to an over-focus on documentation of the quality of care, we are at risk of diminishing the quality of care itself. In essence, many of the requirements appear to simply be more advanced versions of the meaningful (meaningless?) use provisions with which we have previously grappled. It is clear that we should assess the quality of care that is given and that physician payment should be influenced by that care. It is also clear that the only reasonable way to measure the care provided is by collecting data from the EHR. The problem is that the sophistication of the EHR has not caught up to the sophistication of our goals.

Our challenge as physicians who care for patients therefore occurs at an individual level for each of us. How do we provide the necessary documentation scattered throughout our digital charts to satisfy reporting requirements, yet still meet the very real needs of patients to have their voices heard and their emotions acknowledged? The Physician Charter by the American Board of Internal Medicine discusses “the primacy of patient welfare” as a core tenant of medical practice. It goes on to state that “administrative exigencies must not compromise this principle.”2 Given competing demands, how do we continue to accomplish these goals which are often in conflict with one another?

We cannot provide an answer to this question because unfortunately – or perhaps fortunately – the answer does not come in the form of a clear algorithm of behaviors or a form that we can click on. However that does not mean that it cannot be done. Simply being mindful of how important personal interaction is to our patients will help us stay focused on patient needs. In fact, one of the most exciting aspects of our digital age (and our use of EHRs) is that the need to actually connect with people is more important than ever, and prioritizing this stands to reward those individuals who continue to pay attention to patients. In a future column, we will discuss suggestions and strategies for integrating the EHR into truly patient-centered care. In the early 1920s, Dr. Francis W. Peabody said, “The treatment of a disease may be entirely impersonal: the care of the patient must be completely personal.”1 Medical competency is essential and documentation is required, but neither alone is sufficient for the care of patients.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

References

1. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88:877-82.

2. The Physician Charter. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation at http://abimfoundation.org/what-we-do/physician-charter.

GOLD guidelines for the management of COPD – 2017 update

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States1 and a major cause of mortality and morbidity around the world. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) released a new “2017 Report”2 with modified recommendations for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. The report contains several changes that are relevant to the primary care provider that will be outlined below.

Redefining COPD

GOLD’s definition of COPD was changed in its 2017 Report: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations that are due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.” The report emphasizes that “COPD may be punctuated by periods of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, called exacerbations.” Note that the terms “emphysema” and “chronic bronchitis” have been removed in favor of a more comprehensive description of the pathophysiology of COPD. Importantly, the report states that cough and sputum production for at least 3 months in each of 2 consecutive years, previously accepted as diagnostic criteria, are present in only a minority of patients. It is noted that chronic respiratory symptoms may exist without spirometric changes and many patients (usually smokers) have structural evidence of COPD without airflow limitation.

Changes to COPD initial assessment

The primary criterion for diagnosis is unchanged: post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.70. Spirometry remains important to confirm the diagnosis in those with classic symptoms of dyspnea, chronic cough, and/or sputum production with a history of exposure to noxious particles or gases.

The GOLD assessment system previously incorporated spirometry and included an “ABCD” system such that patients in group A are least severe. Spirometry has been progressively deemphasized in favor of symptom-based classification and the 2017 Report, for the first time, dissociates spirometric findings from severity classification.

The new system uses symptom severity and exacerbation risk to classify COPD. Two specific standardized COPD symptom measurement tools, The Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire and COPD Assessment Test (CAT), are reported by GOLD as the most widely used. Low symptom severity is considered an mMRC less than or equal to 1 or CAT less than or equal to 9, high symptom severity is considered an mMRC greater than or equal to 2 or CAT greater than or equal to 10. Low risk of exacerbation is defined as no more than one exacerbation not resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months; high risk of exacerbation is defined as at least two exacerbations or any exacerbations resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months. Symptom severity and exacerbation risk is divided into four quadrants:

• GOLD group A: Low symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group B: High symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group C: Low symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group D: High symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

Changes to prevention and management of stable COPD

Smoking cessation remains important in the prevention of COPD. The 2017 Report reflects the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines for smoking cessation: Offer nicotine replacement, cessation counseling, and pharmacotherapy (varenicline, bupropion or nortriptyline). There is insufficient evidence to support the use of e-cigarettes. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended. Pulmonary rehabilitation remains important.

The 2017 Report includes an expanded discussion of COPD medications. The role of short-acting bronchodilators (SABD) in COPD remains prominent. Changes include a stronger recommendation to use combination short-acting beta-agonists and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SABA/SAMA) as these seem to be superior to SABD monotherapy in improving symptoms and FEV1.

There were several changes to the pharmacologic treatment algorithm. For the first time, GOLD proposes escalation strategies. Preference is given to LABA/LAMA (long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonists) combinations over LABA/ICS (long-acting beta-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid) combinations as a mainstay of treatment. The rationale for this change is that LABA/LAMAs give greater bronchodilation compared with LABA/ICS, and one study showed a decreased rate of exacerbations compared to LABA/ICS in patients with a history of exacerbations. In addition, patients with COPD who receive ICS appear to have a higher risk of developing pneumonia. GOLD recommendations are:

• Group A: Start with single bronchodilator (short- or long-acting), escalate to alternative class of bronchodilator if necessary.

• Group B: Start with LABA or LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA if symptoms persist.

• Group C: Start with LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LABA/ICS if exacerbations continue.

• Group D: Start with LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LAMA monotherapy, escalate to LABA/LAMA/ICS (preferred) or try LABA/ICS before escalating to LAMA/LABA/ICS if symptoms persist or exacerbations continue; roflumilast and/or a macrolide may be considered if further exacerbations occur with LABA/LAMA/ICS.

Bottom line

1. GOLD classification of COPD severity is now based on clinical criteria alone: symptom assessment and risk for exacerbation.

2. SABA/SAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to either SABA or SAMA alone.

3. Patients in group A (milder symptoms, low exacerbation risk) may be initiated on either short- or long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

4. Patients in group B (milder symptoms, increased exacerbation risk) should be initiated on LAMA monotherapy.

5. LABA/LAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to LABA/ICS combination therapy and should be used when long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy fails to control symptoms or reduce exacerbations.

References

1. CDC MMWR 11/23/12

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 at http://goldcopd.org (accessed 3/10/2017)

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Lent is chief resident in the program.

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States1 and a major cause of mortality and morbidity around the world. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) released a new “2017 Report”2 with modified recommendations for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. The report contains several changes that are relevant to the primary care provider that will be outlined below.

Redefining COPD

GOLD’s definition of COPD was changed in its 2017 Report: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations that are due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.” The report emphasizes that “COPD may be punctuated by periods of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, called exacerbations.” Note that the terms “emphysema” and “chronic bronchitis” have been removed in favor of a more comprehensive description of the pathophysiology of COPD. Importantly, the report states that cough and sputum production for at least 3 months in each of 2 consecutive years, previously accepted as diagnostic criteria, are present in only a minority of patients. It is noted that chronic respiratory symptoms may exist without spirometric changes and many patients (usually smokers) have structural evidence of COPD without airflow limitation.

Changes to COPD initial assessment

The primary criterion for diagnosis is unchanged: post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.70. Spirometry remains important to confirm the diagnosis in those with classic symptoms of dyspnea, chronic cough, and/or sputum production with a history of exposure to noxious particles or gases.

The GOLD assessment system previously incorporated spirometry and included an “ABCD” system such that patients in group A are least severe. Spirometry has been progressively deemphasized in favor of symptom-based classification and the 2017 Report, for the first time, dissociates spirometric findings from severity classification.

The new system uses symptom severity and exacerbation risk to classify COPD. Two specific standardized COPD symptom measurement tools, The Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire and COPD Assessment Test (CAT), are reported by GOLD as the most widely used. Low symptom severity is considered an mMRC less than or equal to 1 or CAT less than or equal to 9, high symptom severity is considered an mMRC greater than or equal to 2 or CAT greater than or equal to 10. Low risk of exacerbation is defined as no more than one exacerbation not resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months; high risk of exacerbation is defined as at least two exacerbations or any exacerbations resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months. Symptom severity and exacerbation risk is divided into four quadrants:

• GOLD group A: Low symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group B: High symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group C: Low symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group D: High symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

Changes to prevention and management of stable COPD

Smoking cessation remains important in the prevention of COPD. The 2017 Report reflects the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines for smoking cessation: Offer nicotine replacement, cessation counseling, and pharmacotherapy (varenicline, bupropion or nortriptyline). There is insufficient evidence to support the use of e-cigarettes. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended. Pulmonary rehabilitation remains important.

The 2017 Report includes an expanded discussion of COPD medications. The role of short-acting bronchodilators (SABD) in COPD remains prominent. Changes include a stronger recommendation to use combination short-acting beta-agonists and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SABA/SAMA) as these seem to be superior to SABD monotherapy in improving symptoms and FEV1.

There were several changes to the pharmacologic treatment algorithm. For the first time, GOLD proposes escalation strategies. Preference is given to LABA/LAMA (long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonists) combinations over LABA/ICS (long-acting beta-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid) combinations as a mainstay of treatment. The rationale for this change is that LABA/LAMAs give greater bronchodilation compared with LABA/ICS, and one study showed a decreased rate of exacerbations compared to LABA/ICS in patients with a history of exacerbations. In addition, patients with COPD who receive ICS appear to have a higher risk of developing pneumonia. GOLD recommendations are:

• Group A: Start with single bronchodilator (short- or long-acting), escalate to alternative class of bronchodilator if necessary.

• Group B: Start with LABA or LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA if symptoms persist.

• Group C: Start with LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LABA/ICS if exacerbations continue.

• Group D: Start with LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LAMA monotherapy, escalate to LABA/LAMA/ICS (preferred) or try LABA/ICS before escalating to LAMA/LABA/ICS if symptoms persist or exacerbations continue; roflumilast and/or a macrolide may be considered if further exacerbations occur with LABA/LAMA/ICS.

Bottom line

1. GOLD classification of COPD severity is now based on clinical criteria alone: symptom assessment and risk for exacerbation.

2. SABA/SAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to either SABA or SAMA alone.

3. Patients in group A (milder symptoms, low exacerbation risk) may be initiated on either short- or long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

4. Patients in group B (milder symptoms, increased exacerbation risk) should be initiated on LAMA monotherapy.

5. LABA/LAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to LABA/ICS combination therapy and should be used when long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy fails to control symptoms or reduce exacerbations.

References

1. CDC MMWR 11/23/12

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 at http://goldcopd.org (accessed 3/10/2017)

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Lent is chief resident in the program.

Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States1 and a major cause of mortality and morbidity around the world. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) released a new “2017 Report”2 with modified recommendations for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. The report contains several changes that are relevant to the primary care provider that will be outlined below.

Redefining COPD

GOLD’s definition of COPD was changed in its 2017 Report: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations that are due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.” The report emphasizes that “COPD may be punctuated by periods of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, called exacerbations.” Note that the terms “emphysema” and “chronic bronchitis” have been removed in favor of a more comprehensive description of the pathophysiology of COPD. Importantly, the report states that cough and sputum production for at least 3 months in each of 2 consecutive years, previously accepted as diagnostic criteria, are present in only a minority of patients. It is noted that chronic respiratory symptoms may exist without spirometric changes and many patients (usually smokers) have structural evidence of COPD without airflow limitation.

Changes to COPD initial assessment

The primary criterion for diagnosis is unchanged: post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.70. Spirometry remains important to confirm the diagnosis in those with classic symptoms of dyspnea, chronic cough, and/or sputum production with a history of exposure to noxious particles or gases.

The GOLD assessment system previously incorporated spirometry and included an “ABCD” system such that patients in group A are least severe. Spirometry has been progressively deemphasized in favor of symptom-based classification and the 2017 Report, for the first time, dissociates spirometric findings from severity classification.

The new system uses symptom severity and exacerbation risk to classify COPD. Two specific standardized COPD symptom measurement tools, The Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire and COPD Assessment Test (CAT), are reported by GOLD as the most widely used. Low symptom severity is considered an mMRC less than or equal to 1 or CAT less than or equal to 9, high symptom severity is considered an mMRC greater than or equal to 2 or CAT greater than or equal to 10. Low risk of exacerbation is defined as no more than one exacerbation not resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months; high risk of exacerbation is defined as at least two exacerbations or any exacerbations resulting in hospital admission in the last 12 months. Symptom severity and exacerbation risk is divided into four quadrants:

• GOLD group A: Low symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group B: High symptom severity, low exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group C: Low symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

• GOLD group D: High symptom severity, high exacerbation risk.

Changes to prevention and management of stable COPD

Smoking cessation remains important in the prevention of COPD. The 2017 Report reflects the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s guidelines for smoking cessation: Offer nicotine replacement, cessation counseling, and pharmacotherapy (varenicline, bupropion or nortriptyline). There is insufficient evidence to support the use of e-cigarettes. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended. Pulmonary rehabilitation remains important.

The 2017 Report includes an expanded discussion of COPD medications. The role of short-acting bronchodilators (SABD) in COPD remains prominent. Changes include a stronger recommendation to use combination short-acting beta-agonists and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SABA/SAMA) as these seem to be superior to SABD monotherapy in improving symptoms and FEV1.

There were several changes to the pharmacologic treatment algorithm. For the first time, GOLD proposes escalation strategies. Preference is given to LABA/LAMA (long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonists) combinations over LABA/ICS (long-acting beta-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid) combinations as a mainstay of treatment. The rationale for this change is that LABA/LAMAs give greater bronchodilation compared with LABA/ICS, and one study showed a decreased rate of exacerbations compared to LABA/ICS in patients with a history of exacerbations. In addition, patients with COPD who receive ICS appear to have a higher risk of developing pneumonia. GOLD recommendations are:

• Group A: Start with single bronchodilator (short- or long-acting), escalate to alternative class of bronchodilator if necessary.

• Group B: Start with LABA or LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA if symptoms persist.

• Group C: Start with LAMA, escalate to LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LABA/ICS if exacerbations continue.

• Group D: Start with LABA/LAMA (preferred) or LAMA monotherapy, escalate to LABA/LAMA/ICS (preferred) or try LABA/ICS before escalating to LAMA/LABA/ICS if symptoms persist or exacerbations continue; roflumilast and/or a macrolide may be considered if further exacerbations occur with LABA/LAMA/ICS.

Bottom line

1. GOLD classification of COPD severity is now based on clinical criteria alone: symptom assessment and risk for exacerbation.

2. SABA/SAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to either SABA or SAMA alone.

3. Patients in group A (milder symptoms, low exacerbation risk) may be initiated on either short- or long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

4. Patients in group B (milder symptoms, increased exacerbation risk) should be initiated on LAMA monotherapy.

5. LABA/LAMA combination therapy seems to be superior to LABA/ICS combination therapy and should be used when long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy fails to control symptoms or reduce exacerbations.

References

1. CDC MMWR 11/23/12

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 at http://goldcopd.org (accessed 3/10/2017)

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Lent is chief resident in the program.

Restoring the promise of (really) meaningful use

When we started publishing the EHR Report several years ago, our very first column was a brief overview of a new federal incentive program known as Meaningful Use. At that time, the prospect of receiving thousands of dollars to adopt an electronic health record seemed exciting, and our dream of health care’s digital future appeared to be coming true.

Best of all, we as physicians would be paid to simply embrace it!

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before that dream (for many at least) devolved into a nightmare. Electronic health records hadn’t been designed to fit into physicians’ long-established work flows, and just weren’t up to the challenge of increasing efficiency. In fact, EHRs quickly became virtual taskmasters, leaving physicians mired in a sea of clicks and slow-moving screens.

Frankly speaking, Meaningful Use hasn’t lived up to its promises. With measures obligating users to fill in a myriad of check-boxes and document often irrelevant information, the program has seemed less like an incentive and more like a penance.

To top it off, the all-or-nothing requirement has meant that – after a year of hard work – providers missing even one goal receive no payments at all, and instead are assessed financial penalties!

All of this has appropriately led physicians to become jaded – not excited – about the digital future.

Thankfully, there is reason for hope: 2017 marks the end of Meaningful Use under Medicare.

What’s new for 2017?

MACRA has a much grander scope and sets an even loftier goal: transforming care delivery to achieve better value and ultimately healthier patients.

Now, in case you’re not already confused by the number of programs cited above, there is one more we need to mention to explain the future of EHR incentives: the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS, one of two tracks in the Quality Payment Program.

The majority of Medicare providers will choose this track, which focuses on four major components to determine reimbursement incentives: quality, improvement activities, advancing care information, and cost.

Depending on performance in each of these areas, participants will see a variable payment adjustment (upward or downward) in subsequent years (this is a percentage of Medicare payments that increases annually, beginning with a possible +/– 4% in 2019, to a maximum of +/– 9% in 2022).

Providers under MIPS who choose to attest for this year can select from three levels of participation:

1. Test: submission of only a minimal amount of 2017 data (such as one or two measures) to avoid penalty.

2. Partial: submission of 90 days’ worth of data, which may result in a neutral or positive payment adjustment (and may even earn the max adjustment).

3. Full: submission of a full year of data.

Here’s an example of how this will work: A provider who attests in March 2018 for the full 2017 year and does really well could see up to a 4% incentive bonus on Medicare payments in 2019. A provider who chooses not to attest would receive a penalty of 4%.

It’s worth noting here that MIPS expands upon the inclusion criteria set for Meaningful Use under Medicare. Medicare Part B clinicians are eligible to participate if they bill $30,000 in charges and see at least 100 Medicare patients annually. MIPS also broadens the list of eligible provider types. Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, and certified registered nurse anesthetists are all able to attest.

Advancing Care Information

Under MIPS, Meaningful Use is replaced by an initiative called Advancing Care Information, or ACI. In this new incarnation, there are fewer required measures, and they are much less onerous than they were under the former program.

Also, there are a number of optional measures. A provider may choose to attest to these nonrequired metrics to improve his or her chances of achieving the maximum incentive, but it isn’t necessary. There are also bonus measures involving public health registry reporting. These are optional but a sure bet to increase incentives. In all, the ACI component composes 25% of a provider’s final MIPS score.

For 2017, participants are able to choose one of two tracks in the ACI program, depending on their EHR’s certification year. (If you are confused by this or don’t know the status of your product, check with your vendor or go to https://chpl.healthit.gov to figure it out).

Providers with technology certified to the 2015 edition (or a combination of technologies from the 2014 and 2015 editions) can fully attest to the ACI objectives and measures or elect to use the transition objectives and measures. Those with 2014 edition software must choose the transition measures.

We will cover the specific measures in a future column, but for now we’ll note that both tracks are very similar and focus on protecting patient data, encouraging patient access to their own records, and sharing information electronically with other providers.

Rekindling the dream

We are certain that changing legislation won’t solve all of the problems inherent in current EHR systems, but we are always encouraged by any attempt to reduce the documentation burden on physicians. By eschewing thresholds, eliminating the all-or-nothing requirement, and reducing the number of required measures, the ACI program does seem to shift the focus away from volume and toward value.

That alone has the potential to restore our hope of a brighter future, and make our use of electronic health records significantly more meaningful.

Note: To learn more about Quality Payment Program and MIPS, we highly recommend an online resource published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that is easy to follow and is full of useful information. It can be found at https://qpp.cms.gov.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

When we started publishing the EHR Report several years ago, our very first column was a brief overview of a new federal incentive program known as Meaningful Use. At that time, the prospect of receiving thousands of dollars to adopt an electronic health record seemed exciting, and our dream of health care’s digital future appeared to be coming true.

Best of all, we as physicians would be paid to simply embrace it!

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before that dream (for many at least) devolved into a nightmare. Electronic health records hadn’t been designed to fit into physicians’ long-established work flows, and just weren’t up to the challenge of increasing efficiency. In fact, EHRs quickly became virtual taskmasters, leaving physicians mired in a sea of clicks and slow-moving screens.

Frankly speaking, Meaningful Use hasn’t lived up to its promises. With measures obligating users to fill in a myriad of check-boxes and document often irrelevant information, the program has seemed less like an incentive and more like a penance.

To top it off, the all-or-nothing requirement has meant that – after a year of hard work – providers missing even one goal receive no payments at all, and instead are assessed financial penalties!

All of this has appropriately led physicians to become jaded – not excited – about the digital future.

Thankfully, there is reason for hope: 2017 marks the end of Meaningful Use under Medicare.

What’s new for 2017?

MACRA has a much grander scope and sets an even loftier goal: transforming care delivery to achieve better value and ultimately healthier patients.

Now, in case you’re not already confused by the number of programs cited above, there is one more we need to mention to explain the future of EHR incentives: the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS, one of two tracks in the Quality Payment Program.

The majority of Medicare providers will choose this track, which focuses on four major components to determine reimbursement incentives: quality, improvement activities, advancing care information, and cost.

Depending on performance in each of these areas, participants will see a variable payment adjustment (upward or downward) in subsequent years (this is a percentage of Medicare payments that increases annually, beginning with a possible +/– 4% in 2019, to a maximum of +/– 9% in 2022).

Providers under MIPS who choose to attest for this year can select from three levels of participation:

1. Test: submission of only a minimal amount of 2017 data (such as one or two measures) to avoid penalty.

2. Partial: submission of 90 days’ worth of data, which may result in a neutral or positive payment adjustment (and may even earn the max adjustment).

3. Full: submission of a full year of data.

Here’s an example of how this will work: A provider who attests in March 2018 for the full 2017 year and does really well could see up to a 4% incentive bonus on Medicare payments in 2019. A provider who chooses not to attest would receive a penalty of 4%.

It’s worth noting here that MIPS expands upon the inclusion criteria set for Meaningful Use under Medicare. Medicare Part B clinicians are eligible to participate if they bill $30,000 in charges and see at least 100 Medicare patients annually. MIPS also broadens the list of eligible provider types. Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, and certified registered nurse anesthetists are all able to attest.

Advancing Care Information

Under MIPS, Meaningful Use is replaced by an initiative called Advancing Care Information, or ACI. In this new incarnation, there are fewer required measures, and they are much less onerous than they were under the former program.

Also, there are a number of optional measures. A provider may choose to attest to these nonrequired metrics to improve his or her chances of achieving the maximum incentive, but it isn’t necessary. There are also bonus measures involving public health registry reporting. These are optional but a sure bet to increase incentives. In all, the ACI component composes 25% of a provider’s final MIPS score.

For 2017, participants are able to choose one of two tracks in the ACI program, depending on their EHR’s certification year. (If you are confused by this or don’t know the status of your product, check with your vendor or go to https://chpl.healthit.gov to figure it out).

Providers with technology certified to the 2015 edition (or a combination of technologies from the 2014 and 2015 editions) can fully attest to the ACI objectives and measures or elect to use the transition objectives and measures. Those with 2014 edition software must choose the transition measures.

We will cover the specific measures in a future column, but for now we’ll note that both tracks are very similar and focus on protecting patient data, encouraging patient access to their own records, and sharing information electronically with other providers.

Rekindling the dream

We are certain that changing legislation won’t solve all of the problems inherent in current EHR systems, but we are always encouraged by any attempt to reduce the documentation burden on physicians. By eschewing thresholds, eliminating the all-or-nothing requirement, and reducing the number of required measures, the ACI program does seem to shift the focus away from volume and toward value.

That alone has the potential to restore our hope of a brighter future, and make our use of electronic health records significantly more meaningful.

Note: To learn more about Quality Payment Program and MIPS, we highly recommend an online resource published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that is easy to follow and is full of useful information. It can be found at https://qpp.cms.gov.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

When we started publishing the EHR Report several years ago, our very first column was a brief overview of a new federal incentive program known as Meaningful Use. At that time, the prospect of receiving thousands of dollars to adopt an electronic health record seemed exciting, and our dream of health care’s digital future appeared to be coming true.

Best of all, we as physicians would be paid to simply embrace it!

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before that dream (for many at least) devolved into a nightmare. Electronic health records hadn’t been designed to fit into physicians’ long-established work flows, and just weren’t up to the challenge of increasing efficiency. In fact, EHRs quickly became virtual taskmasters, leaving physicians mired in a sea of clicks and slow-moving screens.

Frankly speaking, Meaningful Use hasn’t lived up to its promises. With measures obligating users to fill in a myriad of check-boxes and document often irrelevant information, the program has seemed less like an incentive and more like a penance.

To top it off, the all-or-nothing requirement has meant that – after a year of hard work – providers missing even one goal receive no payments at all, and instead are assessed financial penalties!

All of this has appropriately led physicians to become jaded – not excited – about the digital future.

Thankfully, there is reason for hope: 2017 marks the end of Meaningful Use under Medicare.

What’s new for 2017?

MACRA has a much grander scope and sets an even loftier goal: transforming care delivery to achieve better value and ultimately healthier patients.

Now, in case you’re not already confused by the number of programs cited above, there is one more we need to mention to explain the future of EHR incentives: the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS, one of two tracks in the Quality Payment Program.

The majority of Medicare providers will choose this track, which focuses on four major components to determine reimbursement incentives: quality, improvement activities, advancing care information, and cost.

Depending on performance in each of these areas, participants will see a variable payment adjustment (upward or downward) in subsequent years (this is a percentage of Medicare payments that increases annually, beginning with a possible +/– 4% in 2019, to a maximum of +/– 9% in 2022).

Providers under MIPS who choose to attest for this year can select from three levels of participation:

1. Test: submission of only a minimal amount of 2017 data (such as one or two measures) to avoid penalty.

2. Partial: submission of 90 days’ worth of data, which may result in a neutral or positive payment adjustment (and may even earn the max adjustment).

3. Full: submission of a full year of data.

Here’s an example of how this will work: A provider who attests in March 2018 for the full 2017 year and does really well could see up to a 4% incentive bonus on Medicare payments in 2019. A provider who chooses not to attest would receive a penalty of 4%.

It’s worth noting here that MIPS expands upon the inclusion criteria set for Meaningful Use under Medicare. Medicare Part B clinicians are eligible to participate if they bill $30,000 in charges and see at least 100 Medicare patients annually. MIPS also broadens the list of eligible provider types. Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, and certified registered nurse anesthetists are all able to attest.

Advancing Care Information

Under MIPS, Meaningful Use is replaced by an initiative called Advancing Care Information, or ACI. In this new incarnation, there are fewer required measures, and they are much less onerous than they were under the former program.

Also, there are a number of optional measures. A provider may choose to attest to these nonrequired metrics to improve his or her chances of achieving the maximum incentive, but it isn’t necessary. There are also bonus measures involving public health registry reporting. These are optional but a sure bet to increase incentives. In all, the ACI component composes 25% of a provider’s final MIPS score.

For 2017, participants are able to choose one of two tracks in the ACI program, depending on their EHR’s certification year. (If you are confused by this or don’t know the status of your product, check with your vendor or go to https://chpl.healthit.gov to figure it out).

Providers with technology certified to the 2015 edition (or a combination of technologies from the 2014 and 2015 editions) can fully attest to the ACI objectives and measures or elect to use the transition objectives and measures. Those with 2014 edition software must choose the transition measures.

We will cover the specific measures in a future column, but for now we’ll note that both tracks are very similar and focus on protecting patient data, encouraging patient access to their own records, and sharing information electronically with other providers.

Rekindling the dream

We are certain that changing legislation won’t solve all of the problems inherent in current EHR systems, but we are always encouraged by any attempt to reduce the documentation burden on physicians. By eschewing thresholds, eliminating the all-or-nothing requirement, and reducing the number of required measures, the ACI program does seem to shift the focus away from volume and toward value.

That alone has the potential to restore our hope of a brighter future, and make our use of electronic health records significantly more meaningful.

Note: To learn more about Quality Payment Program and MIPS, we highly recommend an online resource published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that is easy to follow and is full of useful information. It can be found at https://qpp.cms.gov.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

Reducing CV risk in diabetes: An ADA update

More than 29 million Americans have diabetes, and each year another 1.7 million are given the diagnosis.1 Prediabetes is even more common; over one-third of US adults ages 20 years and older, and more than half of those who are ages 65 and older, have attained this precursor status, representing another 86 million Americans.1

Because the evidence base for the management of diabetes is rapidly expanding, the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) Professional Practice Committee updates its Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes annually to incorporate new evidence into its recommendations. The 2017 Standards of Care are available at: professional.diabetes.org/jfp.2

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for people with diabetes, and is the largest contributor to the direct and indirect costs of the disease.2 As a result, all patients with diabetes should have cardiovascular (CV) risk factors, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, a family history of premature coronary disease, and the presence of albuminuria, assessed at least annually.2 Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of controlling individual CV risk factors in preventing or slowing ASCVD in people with diabetes. Even larger benefits, including reduced ASCVD morbidity and mortality, can be achieved when multiple risk factors are addressed simultaneously.3

To hone your management of CV risks in patients with diabetes, we’ve put together this Q&A pointing out the elements of the ADA’s 2017 Standards of Care that are most relevant to the management of patients at risk for, or with established, ASCVD.

Screening

Since ASCVD so commonly co-occurs with diabetes, should I routinely screen asymptomatic patients with diabetes for heart disease?

No. The current evidence suggests that outcomes are NOT improved by screening people before they develop symptoms of ASCVD,4 and widespread ASCVD screening has not been shown to be cost-effective. Cardiac testing should be reserved for those with typical or atypical symptoms or those with an abnormal resting electrocardiogram (EKG).

Lifestyle modification

What are the benefits of lifestyle interventions?

The benefits include not only lost pounds, but improved mobility, physical and sexual functioning, and health-related quality of life. Recommend that all overweight patients with diabetes take advantage of intensive lifestyle interventions focusing on weight loss through decreased caloric intake and increased physical activity as per the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) trial.5 Although the intensive lifestyle intervention in the Look AHEAD trial did not decrease CV outcomes over 10 years of follow-up, it did improve control of CV risk factors and led to people in the intervention group taking fewer glucose-, blood pressure (BP)-, and lipid-lowering medications than those in the standard care group.

There is no one diet that is recommended for all people with diabetes. Weight reduction often requires intensive intervention. In order for weight loss diets to be sustainable, they must include patient preferences.

People with diabetes should be encouraged to receive individualized medical nutrition therapy (MNT), preferably from a registered dietitian who is well versed in nutritional management for diabetes. Such MNT is associated with a 0.5% to 2% decrease in A1c levels for people with type 2 diabetes.6-9 Specific healthy diets include the Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and plant-based diets.

A new lifestyle recommendation in this year’s ADA Standards is that periods of prolonged sitting should be interrupted every 30 minutes with a period of physical activity. This appears to have glycemic benefits.2

Hypertension/BP management

When should I initiate hypertension treatment in patients with diabetes?

Nonpharmacologic therapy is reasonable in people with diabetes and mildly elevated BP (>120/80 mm Hg). If systolic blood pressure (SBP) is confirmed to be >140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is confirmed to be >90 mm Hg, the ADA recommends initiating pharmacologic therapy along with nonpharmacologic strategies. For patients with confirmed office-based BP >160/100 mm Hg, the ADA advises initiating lifestyle modifications as well as 2 pharmacologic medications (or a single pill combination of agents).2

What is the recommended BP target for patients with diabetes and hypertension?

These patients should be treated with a combination of measures, including lifestyle modification and pharmacologic therapy, to a target BP of <140/90 mm Hg. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown benefits with this target in terms of a reduction in the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) events, stroke, and diabetic kidney disease.10,11

A 2012 meta-analysis of randomized trials involving adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and comparing intensive BP targets (≤130 mm Hg SBP and ≤80 mm Hg DBP) with standard targets (≤140-160 mm Hg SBP and ≤85-100 mm Hg DBP) found no significant reduction in mortality or nonfatal MIs associated with more intense BP control. There was a statistically significant 35% relative risk (RR) reduction in stroke with intensive targets, but lower BP was also associated with an increased risk of hypotension and syncope.12

The 2010 Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial,13 which randomized 5518 patients with T2DM at high risk for ASCVD to either a target SBP of <120 mm Hg or 130 to 140 mm Hg, found that the patients with the lower SBP target did not benefit in the primary end point (a composite of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and CV death), but did benefit from nominally significant lower rates of total stroke and nonfatal stroke.

Based on these data, the ADA Standards of Care suggest that, “more intensive BP control may be reasonable in certain motivated, ACCORD-like patients (40-79 years of age with prior evidence of CVD or multiple CV risk factors) who have been educated about the added treatment burden, side effects, and costs of more intensive BP control and for patients who prefer to lower their risk of stroke beyond what can be achieved with usual care.”

Another major study, the 2015 Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) trial,14 demonstrated that treating patients with hypertension to a target SBP <120 mm Hg compared to the usual target of <140 mm Hg resulted in a 25% lower RR of the primary outcome (a composite of MI, other acute coronary syndromes, stroke, heart failure, or death from CV causes) and about a 25% reduction in all-cause mortality; however, people with diabetes were not included in the trial, so the applicability of the results to decisions about BP management in patients with diabetes is not known.

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of over 100,000 participants looked at SBP lowering in adults with T2DM and found that each 10-mm Hg reduction in SBP was associated with a significantly lower risk of morbidity, CV events, CHD, stroke, albuminuria, and retinopathy.10 When trials were stratified by mean baseline SBP (<140 mm Hg or ≥140 mm Hg), RRs for outcomes other than stroke, retinopathy, and renal failure were lower in studies with greater baseline SBP.

The latest ADA Standards of Care recommend that a lower BP target of 130/80 mm Hg may be appropriate for patients at high risk of CVD if this target can be achieved without undue treatment burden. A DBP of <80 mm Hg may also be appropriate in certain patients including those with a long life expectancy, CKD, elevated urinary albumin excretion, and those with evidence of CVD or associated risk factors.15 Of note, treating older adults with diabetes to an SBP target of <130 mm Hg has not been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes,16 and treating to a diastolic target of <70 mm Hg has been associated with a greater risk of mortality.17

What are the current recommended treatment options?

Treatment for hypertension in adults with diabetes without albuminuria should include any of the classes of medications demonstrated to reduce CV events in patients with diabetes, such as:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors,

- angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs),

- thiazide-like diuretics, and

- dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

These recommendations are based on evidence suggesting the lack of superiority of ACE inhibitors and ARBs over other classes of antihypertensive agents for the prevention of CV outcomes in all patients with diabetes.18 However, in people with diabetes at high risk for ASCVD and/or with albuminuria, ACE inhibitors and ARBs do reduce ASCVD outcomes and the progression of kidney disease.19-24 Thus, ACE inhibitors and ARBs continue to be recommended as first-line medications for the treatment of hypertension in patients with diabetes and urine albumin/creatinine ratios ≥30 mg/g, as these medications are associated with a reduction in the rate of kidney disease progression.

The use of both an ACE inhibitor and an ARB in combination is not recommended.25,26 For patients treated with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuretics, serum creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum potassium levels should be monitored.

What are the recommended lifestyle modifications for patients with diabetes and hypertension?

Regular exercise and healthy eating are recommended for all people with diabetes to optimize glycemic control and lose weight (if they are overweight or obese). For patients with hypertension, the DASH diet (available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/dash/) is effective at lowering BP. The DASH diet emphasizes reducing sodium intake, increasing potassium intake, limiting alcohol intake, and increasing physical activity. Specifically, sodium intake should be restricted to <2300 mg/d and patients should consume approximately 8 to 10 servings of fruits and vegetables per day and 2 to 3 servings of low-fat dairy per day. Alcohol should be limited to 2 drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women.

Most adults with diabetes should perform 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous exercise, spread over at least 3 days/week. In addition, it is recommended that resistance exercises be performed at least 2 to 3 days/week. Prolonged inactivity is detrimental to health and should be interrupted with activity every 30 minutes.27

Finally, as a part of lifestyle management for all patients with diabetes, smoking cessation is important, as is attention to stress, depression, and anxiety.

Is there an advantage to nighttime dosing of antihypertensive medications?

Yes. Growing evidence suggests that there is an ASCVD benefit to avoiding nocturnal BP dipping. A 2011 RCT of 448 participants with T2DM and hypertension showed a decrease in CV events and mortality during 5.4 years of follow-up if at least one antihypertensive medication was taken at bedtime.28 As a result of this and other evidence,29 consider administering one or more antihypertensive medications at bedtime, although this is not a formal recommendation in the ADA Standards of Care.

Are there any additional issues to be aware of when treating patients with diabetes and hypertension?

Yes. Sometimes patients who have had diabetes for many years have significant orthostatic hypotension secondary to autonomic neuropathy. Postural changes in BP and pulse may require adjustment of BP targets. Home BP self-monitoring and 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring may indicate white-coat or masked hypertension.

Lipid management

What is the current evidence for lipid treatment in diabetes?

Lipid abnormalities are common in people with diabetes and contribute to the overall high risk of ASCVD in these patients. Subgroup analyses of patients in large trials with diabetes30 and trials involving patients with diabetes31 have shown significant improvements in primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD with statin use. A 2008 meta-analysis of 18,686 people with diabetes showed a 9% reduction in all-cause mortality and a 13% reduction in vascular mortality for each 39-mg/dL reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.32 Absolute reductions in mortality are greatest in those with highest risk, but the benefits of statin therapy are clear for low- and moderate-risk individuals with diabetes, too.33,34 As a result, statins are the medications of choice for lipid lowering and CV risk reduction and should be used in addition to lifestyle management.

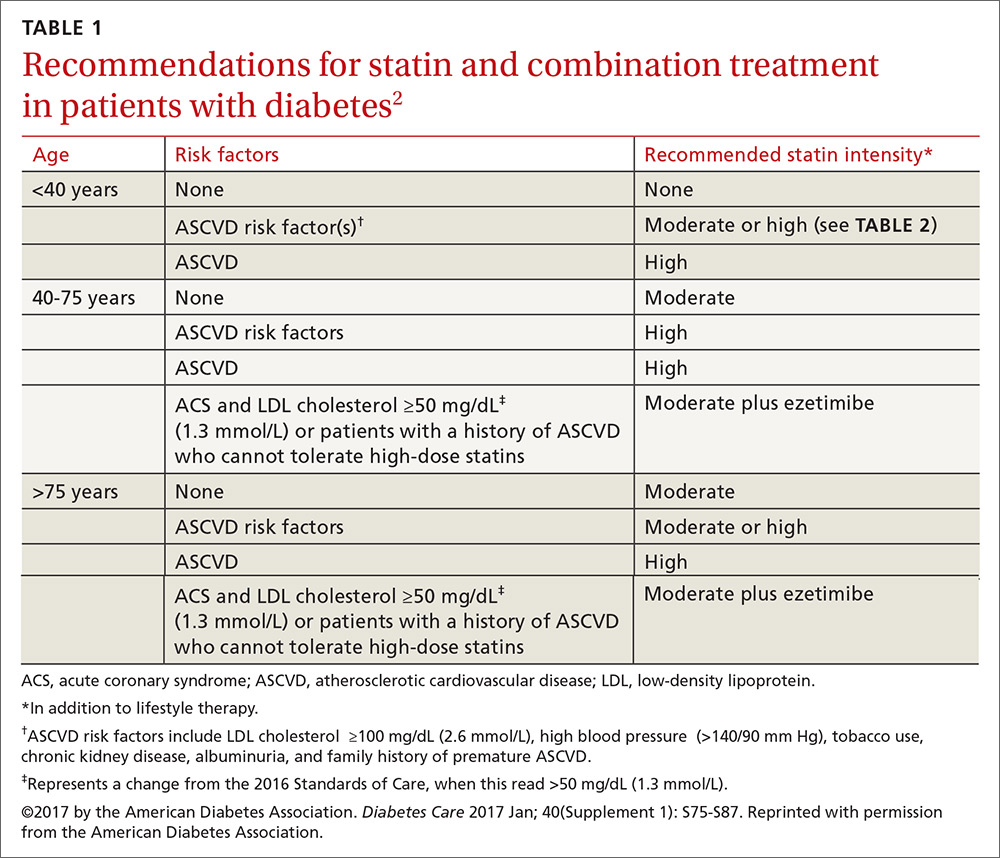

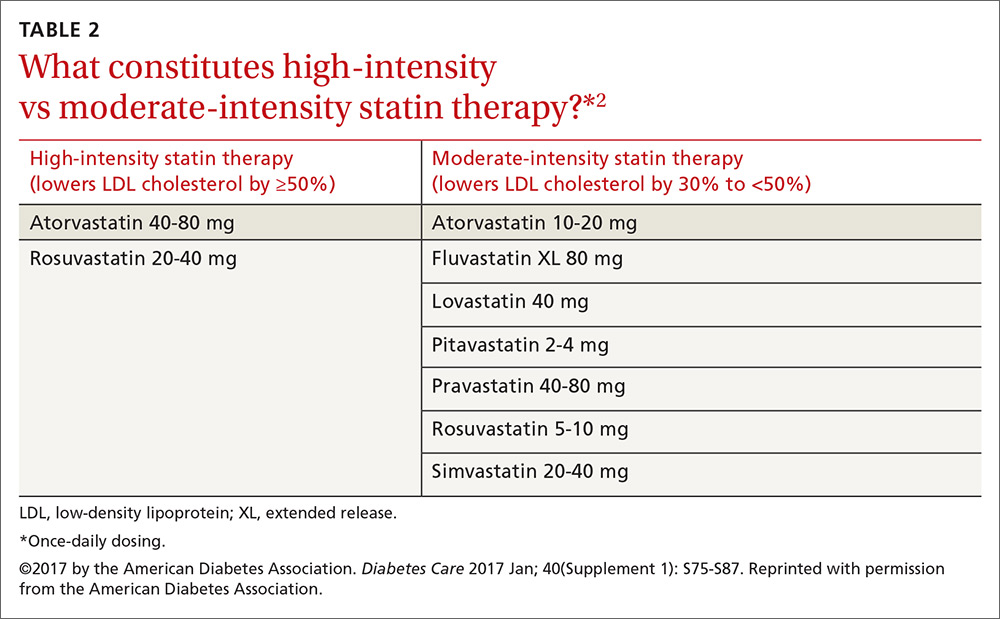

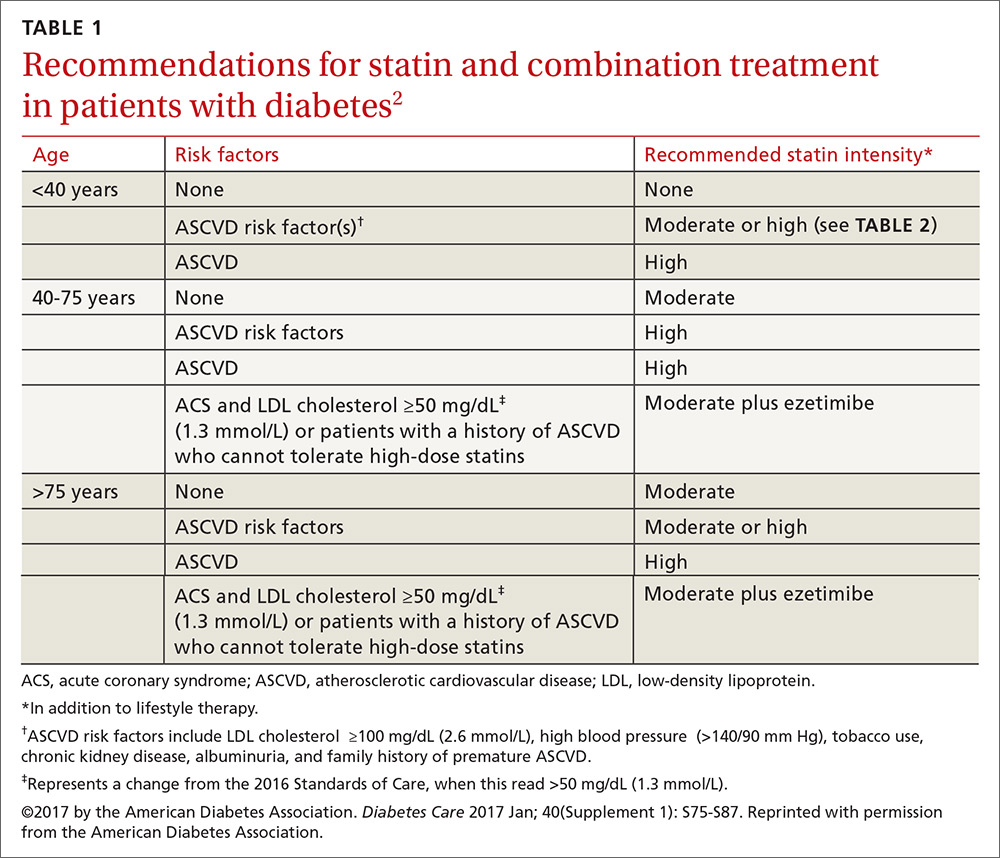

Who should get a statin, and how do I choose the optimum dosage?

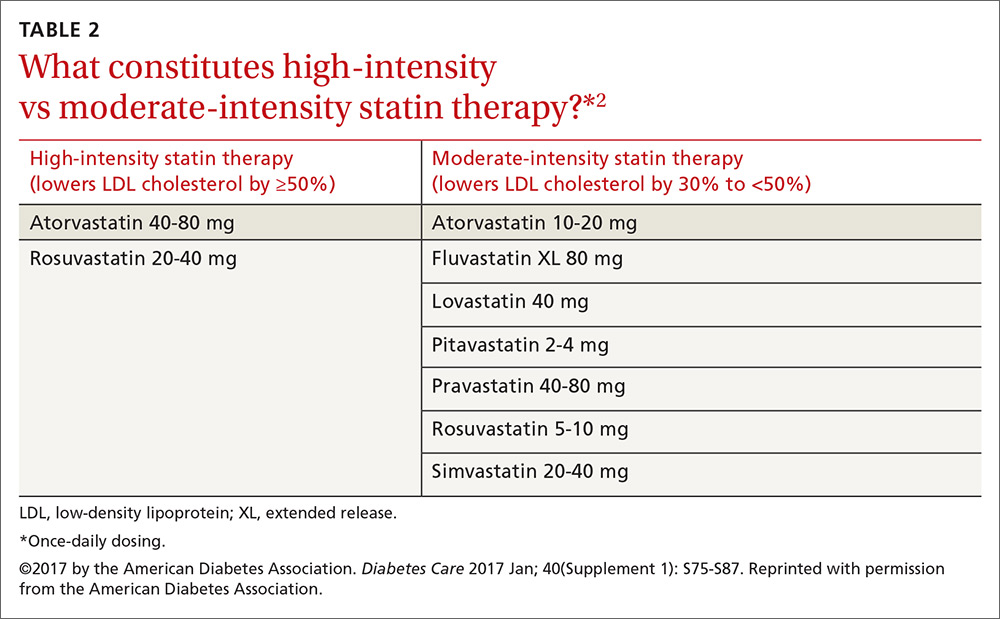

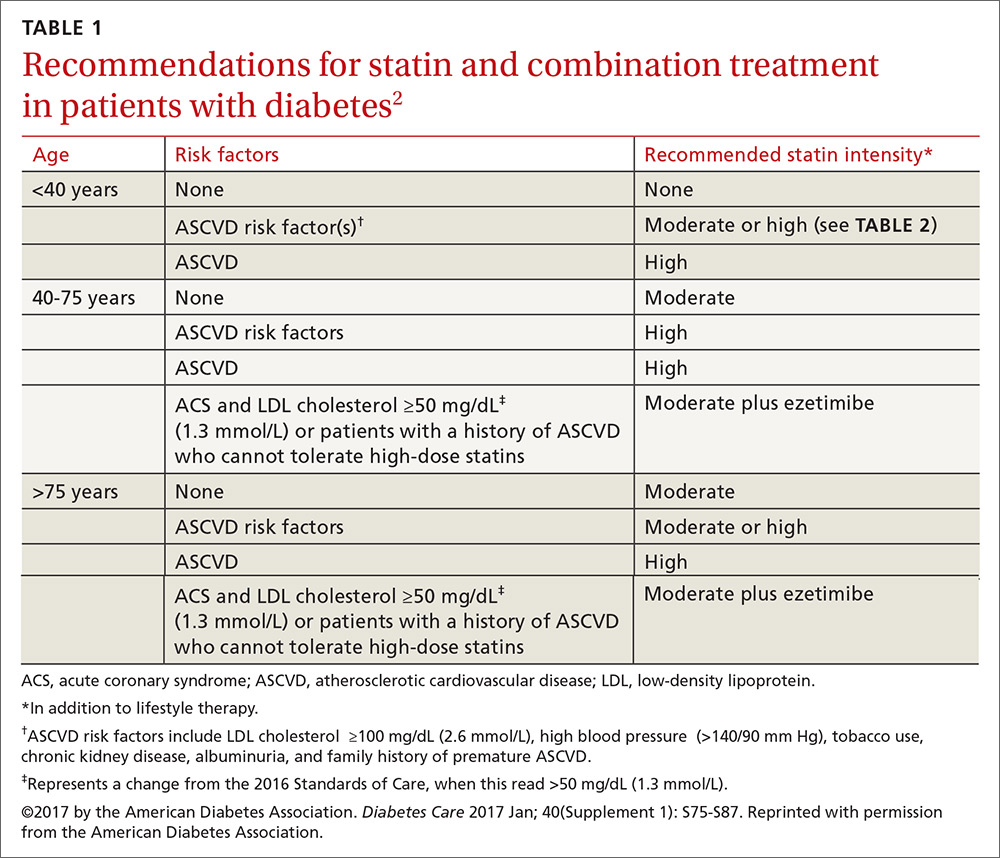

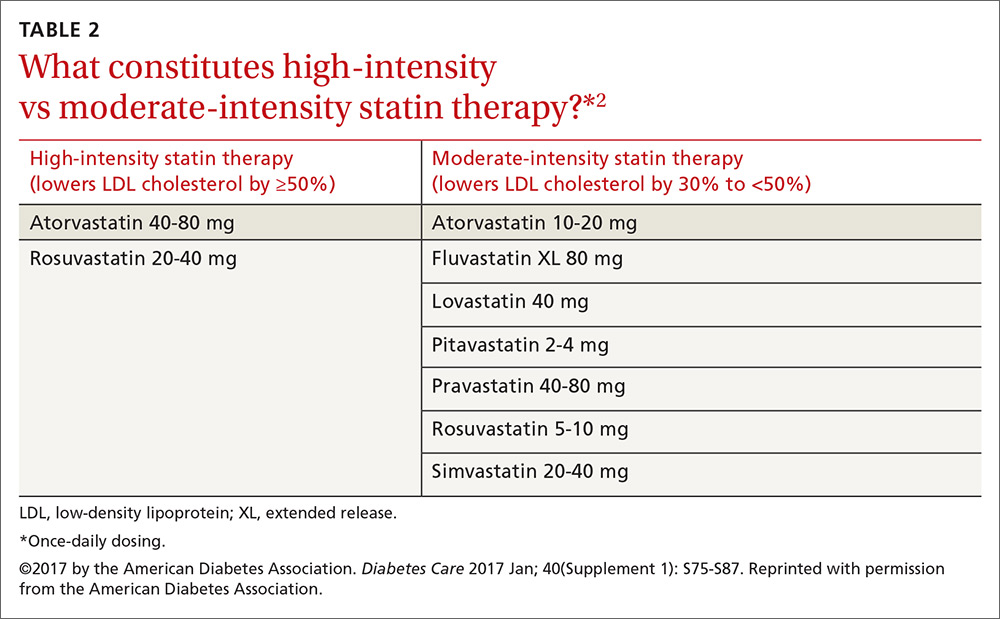

Patients ages 40 to 75 years with diabetes but without additional ASCVD risk factors should receive a moderate-intensity statin, according to the ADA (see TABLES 12 and 22). For those with additional CV risk factors, a high-intensity statin should be considered. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD risk calculator (available at: http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/) may be useful for some patients, but generally, risk is already known to be high for most patients with diabetes. For patients of all ages with diabetes and established ASCVD, high-intensity statin therapy should be added to lifestyle modifications.35-37

For patients with diabetes who are <40 years with additional ASCVD risk factors, few clinical trial data exist; nevertheless, consider a moderate- or high-intensity statin and lifestyle therapy. Similarly, for patients >75 years who have diabetes and no additional ASCVD risk factors, consider a moderate-intensity statin and lifestyle modifications. For older adults with additional ASCVD risk factors, consider high-intensity statin therapy.35-37

Statins and cognition. It should be noted that published data have not demonstrated an adverse effect of statins on cognition.38 Statins, however, have been linked to an increased risk of developing diabetes,39,40 although the absolute increase in risk is small, and much smaller than the benefit derived from preventing the development of coronary disease.

Should total cholesterol and LDL levels be used as targets with statin treatment?

No. Statin doses have primarily been tested against placebo in clinical trials, rather than testing to specific target LDL levels, suggesting that the initiation and intensification of statin therapy be based on a patient’s risk profile.35 When maximally tolerated doses of statins do not lower LDL cholesterol by more than 30% from the patient’s baseline, there is currently no good evidence that combination therapy would be helpful, so regular monitoring of lipid levels has limited value. A lipid profile that includes levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides should be obtained at initial medical evaluation, at diagnosis of diabetes, and every 5 years thereafter or before the initiation of statin therapy. Ongoing testing may be appropriate in individual circumstances and to monitor for adherence to, or efficacy of, therapy.

What should I do for my patients who can’t tolerate statins?

Try a lower dose or a different statin before eliminating the class. Research has shown that even small doses (eg, rosuvastatin 5 mg) have some benefit.41

How do combination treatments figure into the current treatment of lipids in patients with diabetes?

It depends on the agent and the patient’s profile.

Fenofibrate. The ADA does not recommend automatically adding fenofibrate to statin therapy because the combination is associated with increased risks for abnormal transaminase levels, myositis, and rhabdomyolysis. In the ACCORD trial, the combination of fenofibrate and simvastatin did not reduce the rate of fatal CV events, nonfatal MIs, or nonfatal strokes compared with simvastatin alone.42

That said, a subgroup analysis suggested a benefit for men with both a triglyceride level ≥204 mg/dL (2.3 mmol/L) and an HDL cholesterol level ≤34 mg/dL (0.9 mmol/L).42 For this reason, the combination of a statin and fenofibrate may be considered for men who meet these laboratory parameters. In addition, consider medical therapy for triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL to reduce the risk of pancreatitis.

Ezetimibe. Recommendations regarding ezetimibe are based on the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial), a 2015 RCT including over 18,000 patients that compared treatment with ezetimibe and simvastatin to simvastatin alone.43 Individuals in the trial were ≥50 years of age and had experienced an ACS within the preceding 10 days. In those with diabetes, the combination of moderate-intensity simvastatin (40 mg) and ezetimibe (10 mg) significantly reduced major adverse CV events with an absolute risk reduction of 5% (40% vs 45%) and an RR reduction of 14% over moderate-intensity simvastatin (40 mg) alone.

Based on these results, patients with diabetes and a recent ACS should be considered for combination therapy with ezetimibe and a moderate-intensity statin. The combination should also be considered in patients with diabetes and a history of ASCVD who cannot tolerate high-intensity statins.43

Niacin. The ADA currently does not recommend niacin in combination with a statin because of lack of efficacy on major ASCVD outcomes, possible increased risk of ischemic stroke, and adverse effects.44

What are the recommendations for the use of PCSK-9 inhibitors?

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK-9) inhibitors (ie, evolucumab and alirocumab) may be considered as adjunctive therapy to statins for patients with diabetes at high risk for ASCVD events who require additional lowering of LDL cholesterol. They may also be considered for those in whom high-intensity statin therapy is indicated, but not tolerated.

Antiplatelet agents

Who should take aspirin for primary prevention of CVD?

Both women and men ages ≥50 years who have diabetes and at least one additional CV risk factor (family history of premature ASCVD, hypertension, tobacco use, dyslipidemia, or albuminuria) should consider taking daily aspirin therapy (75-162 mg/d) if they do not have an excessive bleeding risk.45,46 The most common dose in the United States is 81 mg. This recommendation is supported by a 2010 consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology.47

Should patients with diabetes and heart disease receive antiplatelet therapy?

Yes. The evidence is clear that people with known diabetes and ASCVD benefit from aspirin therapy, according to the 2017 Standards of Care. Clopidogrel 75 mg/d is an appropriate alternative for patients who are allergic to aspirin. Dual antiplatelet therapy (a P2Y12 receptor antagonist and aspirin) should be used for as long as one year after an ACS and may have benefits beyond this period.48

Established heart disease

Are there specific recommendations for patients with diabetes and CHD?

According to the ADA Standards, there is good evidence that both aspirin and statin therapy are beneficial for patients with known ASCVD, and that high-intensity statin therapy should be used. In addition, consider ACE inhibitors to reduce the future risk of CV events. In patients with a prior MI, continue beta-blocker therapy for at least 2 years post event.49

Which medications should I avoid, or approach with caution, in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF)?

Thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, and metformin all require careful attention. This is especially important to know when you consider that almost half of all patients with T2DM will develop heart failure.50

Thiazolidinediones. The 2017 Standards of Care state that patients with diabetes and symptomatic congestive heart failure should not receive thiazolidinediones, as they can worsen heart failure status via fluid retention. As such, they are contraindicated in patients with class III and IV heart failure.51

DPP-4 inhibitors. The studies on DPP-4 inhibitors and heart failure have had mixed results. The 2013 SAVOR-TIMI (Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 53 trial52 showed that patients treated with saxagliptin were more likely to be hospitalized for heart failure than those taking placebo (3.5% vs 2.8%, respectively). However, the 2015 EXAMINE (Examination of Cardiovascular Outcomes with Alogliptin vs Standard of Care)53 trial and the 2015 TECOS (Trial Evaluating Cardiovascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin)54 trial evaluated heart failure and mortality outcomes in patients with alogliptin and sitagliptin, respectively, compared to placebo, and did not show a relationship to heart failure.

Metformin may be used in people who have T2DM and stable CHF if their eGFR remains >30 mL/min; it should be withheld from patients with unstable heart failure and those who are hospitalized with CHF.

Are there antihyperglycemic medications that reduce CV morbidity and mortality in those with established ASCVD?

Yes. This year’s ADA Standards indicate that certain glucose-lowering medications—specifically empagliflozin (a sodium–glucose cotransporter [SGLT]-2 inhibitor) and liraglutide (a glucagon-like peptide [GLP]-1 receptor agonist)—have been shown to be beneficial for those with established CVD. According to the 2017 Standards of Care, “In patients with longstanding suboptimally controlled T2DM and established ASCVD, empagliflozin or liraglutide should be considered, as they have been shown to reduce CV and all-cause mortality when added to standard care.”2 The studies that provide support for their use are summarized below. Ongoing studies are investigating the CV effects of other agents in these drug classes.

Empagliflozin. The 2015 EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) study55 was a randomized double-blind study of empagliflozin vs placebo and usual care in patients with diabetes and established CVD. Over a median follow-up of 3.1 years, treatment with empagliflozin reduced the aggregate outcome of MI, stroke, and CV death by 14%, reduced CV deaths by 38%, and decreased deaths from any cause by 32%. In December 2016, the FDA announced a new indication for empagliflozin: to reduce the risk of CV death in adult patients with T2DM and CVD.56

Liraglutide. The LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results: A Long Term Evaluation) trial57 was a double-blind randomized trial of liraglutide vs placebo added to usual care in patients with T2DM at high risk for CVD or with existing CVD. More than 80% of the participants had existing CVD including a history of prior MI, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease. After a median follow-up of 3.8 years, the group taking liraglutide demonstrated a 13% reduction in the composite outcome of MI, stroke, or CV death, a 22% reduction in CV death, and a 15% reduction in death from any cause, compared with placebo.57

CORRESPONDENCE

Neil Skolnik, MD, Abington-Jefferson Health, 500 Old York Rd, Ste 108, Jenkintown, PA 19046; [email protected].

The authors thank Sarah Bradley, director, professional engagement & collaboration at the American Diabetes Association, for her editorial and organizational assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National diabetes statistics report, 2014. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Available at: http://templatelab.com/national-diabetes-report-2014/. Accessed April 7, 2017.

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2017. Available at: http://professional.diabetes.org/sites/professional.diabetes.org/files/media/dc_40_s1_final.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2017.

3. Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, et al. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:580-591.

4. Bax JJ, Young LH, Frye RL, et al; American Diabetes Association. Screening for coronary artery disease in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2729-2736.

5. The Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145-154.