User login

CLINICAL GUIDELINES: Primary care bronchiolitis guidelines

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants during the first 12 months of life. Approximately 100,000 bronchiolitis admissions occur annually in children in the United States, at an estimated cost of $1.73 billion. The American Academy of Pediatrics recently published new guidelines for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis in children younger than 2 years.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on patient history and physical examination. The course and severity of bronchiolitis vary, ranging from mild disease with simple runny nose and cough, to transient apneic events, and on to progressive respiratory distress secondary to airway obstruction. Management of bronchiolitis must be determined in the context of increased risk factors for severe disease, including age less than 12 weeks, history of prematurity, underlying cardiopulmonary disease, and immunodeficiency. Current evidence does not support routine labs or diagnostic imaging as helping with risk assessment. Abnormalities on chest x-ray, which are common in children with bronchiolitis, do reliably predict severity of disease, so chest x-rays are only indicated when another etiology of respiratory distress such as pneumothorax or pneumonia is a concern. Routine virologic testing is not recommended, as it does not appear to aid in guiding the treatment of the child with bronchiolitis.

Management

Randomized trials have not shown any benefit from alpha- or beta-adrenergic agonist administration. Bronchodilators can lessen symptoms scores, but their use does not speed disease resolution or decrease the length of stay or need for hospitalization. A Cochrane analysis concluded that there was no benefit to giving bronchodilators to infants with bronchiolitis. Adverse effects included tachycardia, tremors, and cost, all of which outweigh potential benefits. While previous versions of the AAP guidelines recommended bronchodilators as an option, the 2014 guidelines state, “Clinicians should not administer albuterol (or salbutamol) to infants and children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis (Evidence Quality: B; Recommendation Strength: Strong).” It is noted that there may be some children who have reversible airway obstruction, but it is impossible to tell ahead of time who they are; and due to the variability of the disease, it is even hard to tell in whom the medication is effective. It is acknowledged that children with severe disease were usually excluded from the studies of bronchodilators. Epinephrine should also not be used except potentially as a rescue agent in severe disease.

Nebulized hypertonic saline appears to increase mucociliary clearance. Nebulized 3% saline is safe and effective in improving symptoms of mild to moderate bronchiolitis when measured after 24 hours of use, and it possibly decreases the length of hospital stay in studies where the length of stay exceeded 3 days. The guidelines conclude that hypertonic saline may be helpful to infants who are hospitalized with bronchiolitis, but probably is of very little benefit when administered in an emergency department setting.

Although there is strong evidence of benefit of systemic corticosteroids in asthma and croup, there is no evidence that systemic corticosteroids provide benefit in bronchiolitis. In addition, there is some evidence that corticosteroids may prolong viral shedding. For these reasons, the 2014 guidelines state, “Clinicians should not administer systemic corticosteroids to infants with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis in any setting (Evidence Quality: A; Recommendation Strength: Strong Recommendation).”

Physicians may choose not to give supplemental oxygen if oxyhemoglobin saturation is more than 90%, and also not to use continuous pulse oximetry given that it is prone to errors of measurement. Chest physiotherapy is not recommended. Antibiotics use is not recommended unless there is a concomitant bacterial infection or strong suspicion of one.

Prevention

The guidelines advise that palivizumab (Synagis) should not be given to otherwise healthy infants with a gestational age of 29 weeks or greater. Palivizumab should be given in the first year of life to infants with hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity (defined as infants of less than 32 weeks’ gestation who required more than 21% oxygen for at least the first 28 days of life). Infants who qualify for palivizumab at the start of respiratory syncytial virus season should receive a maximum of five monthly doses (15 mg/kg per dose) of palivizumab or until the end of RSV season, whichever comes first. Because of the low risk of RSV hospitalization in the second year of life, palivizumab prophylaxis is not recommended for children in the second year of life, unless the child meets the criteria for chronic lung disease and continues to require supplemental oxygen or is on chronic corticosteroids or diuretic therapy within 6 months of the onset of the second RSV season.

Reference

Ralston S.L. "Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Bronchiolitis." Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-502).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Rastogi is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Ralston S.L. “Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Bronchiolitis.” Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-502).

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants during the first 12 months of life. Approximately 100,000 bronchiolitis admissions occur annually in children in the United States, at an estimated cost of $1.73 billion. The American Academy of Pediatrics recently published new guidelines for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis in children younger than 2 years.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on patient history and physical examination. The course and severity of bronchiolitis vary, ranging from mild disease with simple runny nose and cough, to transient apneic events, and on to progressive respiratory distress secondary to airway obstruction. Management of bronchiolitis must be determined in the context of increased risk factors for severe disease, including age less than 12 weeks, history of prematurity, underlying cardiopulmonary disease, and immunodeficiency. Current evidence does not support routine labs or diagnostic imaging as helping with risk assessment. Abnormalities on chest x-ray, which are common in children with bronchiolitis, do reliably predict severity of disease, so chest x-rays are only indicated when another etiology of respiratory distress such as pneumothorax or pneumonia is a concern. Routine virologic testing is not recommended, as it does not appear to aid in guiding the treatment of the child with bronchiolitis.

Management

Randomized trials have not shown any benefit from alpha- or beta-adrenergic agonist administration. Bronchodilators can lessen symptoms scores, but their use does not speed disease resolution or decrease the length of stay or need for hospitalization. A Cochrane analysis concluded that there was no benefit to giving bronchodilators to infants with bronchiolitis. Adverse effects included tachycardia, tremors, and cost, all of which outweigh potential benefits. While previous versions of the AAP guidelines recommended bronchodilators as an option, the 2014 guidelines state, “Clinicians should not administer albuterol (or salbutamol) to infants and children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis (Evidence Quality: B; Recommendation Strength: Strong).” It is noted that there may be some children who have reversible airway obstruction, but it is impossible to tell ahead of time who they are; and due to the variability of the disease, it is even hard to tell in whom the medication is effective. It is acknowledged that children with severe disease were usually excluded from the studies of bronchodilators. Epinephrine should also not be used except potentially as a rescue agent in severe disease.

Nebulized hypertonic saline appears to increase mucociliary clearance. Nebulized 3% saline is safe and effective in improving symptoms of mild to moderate bronchiolitis when measured after 24 hours of use, and it possibly decreases the length of hospital stay in studies where the length of stay exceeded 3 days. The guidelines conclude that hypertonic saline may be helpful to infants who are hospitalized with bronchiolitis, but probably is of very little benefit when administered in an emergency department setting.

Although there is strong evidence of benefit of systemic corticosteroids in asthma and croup, there is no evidence that systemic corticosteroids provide benefit in bronchiolitis. In addition, there is some evidence that corticosteroids may prolong viral shedding. For these reasons, the 2014 guidelines state, “Clinicians should not administer systemic corticosteroids to infants with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis in any setting (Evidence Quality: A; Recommendation Strength: Strong Recommendation).”

Physicians may choose not to give supplemental oxygen if oxyhemoglobin saturation is more than 90%, and also not to use continuous pulse oximetry given that it is prone to errors of measurement. Chest physiotherapy is not recommended. Antibiotics use is not recommended unless there is a concomitant bacterial infection or strong suspicion of one.

Prevention

The guidelines advise that palivizumab (Synagis) should not be given to otherwise healthy infants with a gestational age of 29 weeks or greater. Palivizumab should be given in the first year of life to infants with hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity (defined as infants of less than 32 weeks’ gestation who required more than 21% oxygen for at least the first 28 days of life). Infants who qualify for palivizumab at the start of respiratory syncytial virus season should receive a maximum of five monthly doses (15 mg/kg per dose) of palivizumab or until the end of RSV season, whichever comes first. Because of the low risk of RSV hospitalization in the second year of life, palivizumab prophylaxis is not recommended for children in the second year of life, unless the child meets the criteria for chronic lung disease and continues to require supplemental oxygen or is on chronic corticosteroids or diuretic therapy within 6 months of the onset of the second RSV season.

Reference

Ralston S.L. "Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Bronchiolitis." Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-502).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Rastogi is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants during the first 12 months of life. Approximately 100,000 bronchiolitis admissions occur annually in children in the United States, at an estimated cost of $1.73 billion. The American Academy of Pediatrics recently published new guidelines for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis in children younger than 2 years.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on patient history and physical examination. The course and severity of bronchiolitis vary, ranging from mild disease with simple runny nose and cough, to transient apneic events, and on to progressive respiratory distress secondary to airway obstruction. Management of bronchiolitis must be determined in the context of increased risk factors for severe disease, including age less than 12 weeks, history of prematurity, underlying cardiopulmonary disease, and immunodeficiency. Current evidence does not support routine labs or diagnostic imaging as helping with risk assessment. Abnormalities on chest x-ray, which are common in children with bronchiolitis, do reliably predict severity of disease, so chest x-rays are only indicated when another etiology of respiratory distress such as pneumothorax or pneumonia is a concern. Routine virologic testing is not recommended, as it does not appear to aid in guiding the treatment of the child with bronchiolitis.

Management

Randomized trials have not shown any benefit from alpha- or beta-adrenergic agonist administration. Bronchodilators can lessen symptoms scores, but their use does not speed disease resolution or decrease the length of stay or need for hospitalization. A Cochrane analysis concluded that there was no benefit to giving bronchodilators to infants with bronchiolitis. Adverse effects included tachycardia, tremors, and cost, all of which outweigh potential benefits. While previous versions of the AAP guidelines recommended bronchodilators as an option, the 2014 guidelines state, “Clinicians should not administer albuterol (or salbutamol) to infants and children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis (Evidence Quality: B; Recommendation Strength: Strong).” It is noted that there may be some children who have reversible airway obstruction, but it is impossible to tell ahead of time who they are; and due to the variability of the disease, it is even hard to tell in whom the medication is effective. It is acknowledged that children with severe disease were usually excluded from the studies of bronchodilators. Epinephrine should also not be used except potentially as a rescue agent in severe disease.

Nebulized hypertonic saline appears to increase mucociliary clearance. Nebulized 3% saline is safe and effective in improving symptoms of mild to moderate bronchiolitis when measured after 24 hours of use, and it possibly decreases the length of hospital stay in studies where the length of stay exceeded 3 days. The guidelines conclude that hypertonic saline may be helpful to infants who are hospitalized with bronchiolitis, but probably is of very little benefit when administered in an emergency department setting.

Although there is strong evidence of benefit of systemic corticosteroids in asthma and croup, there is no evidence that systemic corticosteroids provide benefit in bronchiolitis. In addition, there is some evidence that corticosteroids may prolong viral shedding. For these reasons, the 2014 guidelines state, “Clinicians should not administer systemic corticosteroids to infants with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis in any setting (Evidence Quality: A; Recommendation Strength: Strong Recommendation).”

Physicians may choose not to give supplemental oxygen if oxyhemoglobin saturation is more than 90%, and also not to use continuous pulse oximetry given that it is prone to errors of measurement. Chest physiotherapy is not recommended. Antibiotics use is not recommended unless there is a concomitant bacterial infection or strong suspicion of one.

Prevention

The guidelines advise that palivizumab (Synagis) should not be given to otherwise healthy infants with a gestational age of 29 weeks or greater. Palivizumab should be given in the first year of life to infants with hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity (defined as infants of less than 32 weeks’ gestation who required more than 21% oxygen for at least the first 28 days of life). Infants who qualify for palivizumab at the start of respiratory syncytial virus season should receive a maximum of five monthly doses (15 mg/kg per dose) of palivizumab or until the end of RSV season, whichever comes first. Because of the low risk of RSV hospitalization in the second year of life, palivizumab prophylaxis is not recommended for children in the second year of life, unless the child meets the criteria for chronic lung disease and continues to require supplemental oxygen or is on chronic corticosteroids or diuretic therapy within 6 months of the onset of the second RSV season.

Reference

Ralston S.L. "Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Bronchiolitis." Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-502).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Rastogi is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Ralston S.L. “Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Bronchiolitis.” Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-502).

Ralston S.L. “Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Bronchiolitis.” Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-502).

Sharing is caring: A primer on EHR interoperability

The debate over the future of meaningful use seems to have found its bellwether issue: interoperability. For the uninitiated, this is the concept of sharing patient information across systems with the promise of improving the ease and quality of care. As you might expect, it is full of challenges, not the least of which is standardization. Competing vendors of electronic health record (EHR) software and technological hurdles have made the goal of true interoperability quite elusive, and there is no clear path to victory. Meaningful use and other incentive programs have set requirements for widespread rapid adoption of data sharing. Unfortunately, instead of encouraging innovation, they seem only to have created more stumbling blocks for physicians. Now providers are facing penalties for noncompliance, and national physician advocacy groups are taking notice.

On Oct. 15 of this year, a letter from key stakeholders including the American Medical Association (AMA), American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) to the Department of Health and Human Services laid out a “blueprint” for revamping the meaningful use program. The center point of this communication was a call for more emphasis on interoperability, as well as flexibility for both vendors and physicians. We tend to agree with these ideas, but wonder on a global scale what this interoperability should look like. In this column, we’ll address the essential pieces to making this a reality, and how physicians and patients can benefit from enhanced information exchange.

Information should be standardized

One of the fundamental challenges standing in the way of true interoperability is standardization: allowing data to be shared and viewed anywhere, independent of hardware or software. This is an idea that has allowed the World Wide Web to flourish; websites are readable by any computer or mobile device, using any operating system or browser. As of now, very little standardization exists in the world of medical data, in part because EHRs have been developed and promoted by private corporations, all competing for market share.

This evolution is quite unlike the history of the Internet, which was developed by government and educational institutions, with the express intent of connecting disparate computer systems. EHRs have essentially been developed in isolation, with much more emphasis placed on keeping information private than on making it shareable. Now meaningful use is forcing vendors to share data across systems, and – not surprisingly – each vendor is attempting to create their own method of doing so.

Some argue that EHR companies would prefer not to share, as this might threaten their hold on the market. In fact, Epic Health Systems, the world’s largest EHR vendor, has recently faced accusations of limiting interoperability to encourage physicians to use its software exclusively. Epic has fired back with statistics pointing to its accomplishments in data exchange. Both sides clearly disagree on what true interoperability should look like. This underscores a critical point: The concept of interoperability and what the standards should look like may mean different things to different parties.

One attempt at standardization that is commonly referenced is the continuity of care document (CCD), a key requirement for data exchange outlined in Stage 2 of meaningful use. This document, endorsed by the U.S. Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel, has gained popularity as it can contain large amounts of data in one file. Unfortunately, it too is still limited and often isn’t user friendly at the point of care. It is in many ways merely a jumping-off point that will hopefully facilitate improved data accessibility and ease of sharing.

To improve usability and confidence in data exchange, many practices and health systems have joined together to create Regional Health Information Organizations and provide some governance structure to the process of data exchange. We strongly recommend getting involved in such an organization and engaging in the process of standardization. Regardless of your position on the usefulness or practicality of sharing patient records, a few notions are indisputable: Interoperability is coming, and point-of-care data availability – if accurate, secure, and useful – can ultimately usher in the promise of better patient care.

Information should be secure

In the process of seeking easier data exchange, we cannot lose sight of the importance of data security. Health care entities need to feel confident the information they are sending electronically will stay private until it reaches its ultimate destination. An attempt to address this issue led to the development of the “direct” encryption standard in 2010. Also known as Direct Exchange and Direct Secure Messaging, it specifies a secure method for the exchange of Protected Health Information. Providers can take advantage of the security offered through Direct by developing their own infrastructure or engaging the services of a Health Information Service Provider. These are private, HIPAA-compliant data exchange services that serve a health care community and facilitate direct messaging between health care settings. Ultimately, the goal is to create a robust Nationwide Health Information Network and achieve true widespread health information exchange. But before we actually achieve this, there is one more element essential to interoperability and improving patient care.

The information should be useful

In the preliminary stages of EHR interoperability, attempts at meaningful information exchange have led to only modest success. Outside of private health systems that have developed their own proprietary interfaces, data extraction and sharing between disparate electronic platforms have yet to have a meaningful impact on patient care. In part, this is because the information is not provided to clinicians in a useful format. Even the CCD described above is often confusing and replete with extraneous information – filtering through it during a patient encounter can be tedious and frustrating. Also, ensuring data integrity can be a real challenge, not only technically, but also practically. Questions occur regularly, such as “Did the data come through in the correct fields?” or “Did the medical resident remember to include all of the medications or allergies associated with the patient?” Ultimately, physicians need to decide whether or not to trust the information they receive before making it a permanent part of a patient’s health record.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The debate over the future of meaningful use seems to have found its bellwether issue: interoperability. For the uninitiated, this is the concept of sharing patient information across systems with the promise of improving the ease and quality of care. As you might expect, it is full of challenges, not the least of which is standardization. Competing vendors of electronic health record (EHR) software and technological hurdles have made the goal of true interoperability quite elusive, and there is no clear path to victory. Meaningful use and other incentive programs have set requirements for widespread rapid adoption of data sharing. Unfortunately, instead of encouraging innovation, they seem only to have created more stumbling blocks for physicians. Now providers are facing penalties for noncompliance, and national physician advocacy groups are taking notice.

On Oct. 15 of this year, a letter from key stakeholders including the American Medical Association (AMA), American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) to the Department of Health and Human Services laid out a “blueprint” for revamping the meaningful use program. The center point of this communication was a call for more emphasis on interoperability, as well as flexibility for both vendors and physicians. We tend to agree with these ideas, but wonder on a global scale what this interoperability should look like. In this column, we’ll address the essential pieces to making this a reality, and how physicians and patients can benefit from enhanced information exchange.

Information should be standardized

One of the fundamental challenges standing in the way of true interoperability is standardization: allowing data to be shared and viewed anywhere, independent of hardware or software. This is an idea that has allowed the World Wide Web to flourish; websites are readable by any computer or mobile device, using any operating system or browser. As of now, very little standardization exists in the world of medical data, in part because EHRs have been developed and promoted by private corporations, all competing for market share.

This evolution is quite unlike the history of the Internet, which was developed by government and educational institutions, with the express intent of connecting disparate computer systems. EHRs have essentially been developed in isolation, with much more emphasis placed on keeping information private than on making it shareable. Now meaningful use is forcing vendors to share data across systems, and – not surprisingly – each vendor is attempting to create their own method of doing so.

Some argue that EHR companies would prefer not to share, as this might threaten their hold on the market. In fact, Epic Health Systems, the world’s largest EHR vendor, has recently faced accusations of limiting interoperability to encourage physicians to use its software exclusively. Epic has fired back with statistics pointing to its accomplishments in data exchange. Both sides clearly disagree on what true interoperability should look like. This underscores a critical point: The concept of interoperability and what the standards should look like may mean different things to different parties.

One attempt at standardization that is commonly referenced is the continuity of care document (CCD), a key requirement for data exchange outlined in Stage 2 of meaningful use. This document, endorsed by the U.S. Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel, has gained popularity as it can contain large amounts of data in one file. Unfortunately, it too is still limited and often isn’t user friendly at the point of care. It is in many ways merely a jumping-off point that will hopefully facilitate improved data accessibility and ease of sharing.

To improve usability and confidence in data exchange, many practices and health systems have joined together to create Regional Health Information Organizations and provide some governance structure to the process of data exchange. We strongly recommend getting involved in such an organization and engaging in the process of standardization. Regardless of your position on the usefulness or practicality of sharing patient records, a few notions are indisputable: Interoperability is coming, and point-of-care data availability – if accurate, secure, and useful – can ultimately usher in the promise of better patient care.

Information should be secure

In the process of seeking easier data exchange, we cannot lose sight of the importance of data security. Health care entities need to feel confident the information they are sending electronically will stay private until it reaches its ultimate destination. An attempt to address this issue led to the development of the “direct” encryption standard in 2010. Also known as Direct Exchange and Direct Secure Messaging, it specifies a secure method for the exchange of Protected Health Information. Providers can take advantage of the security offered through Direct by developing their own infrastructure or engaging the services of a Health Information Service Provider. These are private, HIPAA-compliant data exchange services that serve a health care community and facilitate direct messaging between health care settings. Ultimately, the goal is to create a robust Nationwide Health Information Network and achieve true widespread health information exchange. But before we actually achieve this, there is one more element essential to interoperability and improving patient care.

The information should be useful

In the preliminary stages of EHR interoperability, attempts at meaningful information exchange have led to only modest success. Outside of private health systems that have developed their own proprietary interfaces, data extraction and sharing between disparate electronic platforms have yet to have a meaningful impact on patient care. In part, this is because the information is not provided to clinicians in a useful format. Even the CCD described above is often confusing and replete with extraneous information – filtering through it during a patient encounter can be tedious and frustrating. Also, ensuring data integrity can be a real challenge, not only technically, but also practically. Questions occur regularly, such as “Did the data come through in the correct fields?” or “Did the medical resident remember to include all of the medications or allergies associated with the patient?” Ultimately, physicians need to decide whether or not to trust the information they receive before making it a permanent part of a patient’s health record.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The debate over the future of meaningful use seems to have found its bellwether issue: interoperability. For the uninitiated, this is the concept of sharing patient information across systems with the promise of improving the ease and quality of care. As you might expect, it is full of challenges, not the least of which is standardization. Competing vendors of electronic health record (EHR) software and technological hurdles have made the goal of true interoperability quite elusive, and there is no clear path to victory. Meaningful use and other incentive programs have set requirements for widespread rapid adoption of data sharing. Unfortunately, instead of encouraging innovation, they seem only to have created more stumbling blocks for physicians. Now providers are facing penalties for noncompliance, and national physician advocacy groups are taking notice.

On Oct. 15 of this year, a letter from key stakeholders including the American Medical Association (AMA), American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) to the Department of Health and Human Services laid out a “blueprint” for revamping the meaningful use program. The center point of this communication was a call for more emphasis on interoperability, as well as flexibility for both vendors and physicians. We tend to agree with these ideas, but wonder on a global scale what this interoperability should look like. In this column, we’ll address the essential pieces to making this a reality, and how physicians and patients can benefit from enhanced information exchange.

Information should be standardized

One of the fundamental challenges standing in the way of true interoperability is standardization: allowing data to be shared and viewed anywhere, independent of hardware or software. This is an idea that has allowed the World Wide Web to flourish; websites are readable by any computer or mobile device, using any operating system or browser. As of now, very little standardization exists in the world of medical data, in part because EHRs have been developed and promoted by private corporations, all competing for market share.

This evolution is quite unlike the history of the Internet, which was developed by government and educational institutions, with the express intent of connecting disparate computer systems. EHRs have essentially been developed in isolation, with much more emphasis placed on keeping information private than on making it shareable. Now meaningful use is forcing vendors to share data across systems, and – not surprisingly – each vendor is attempting to create their own method of doing so.

Some argue that EHR companies would prefer not to share, as this might threaten their hold on the market. In fact, Epic Health Systems, the world’s largest EHR vendor, has recently faced accusations of limiting interoperability to encourage physicians to use its software exclusively. Epic has fired back with statistics pointing to its accomplishments in data exchange. Both sides clearly disagree on what true interoperability should look like. This underscores a critical point: The concept of interoperability and what the standards should look like may mean different things to different parties.

One attempt at standardization that is commonly referenced is the continuity of care document (CCD), a key requirement for data exchange outlined in Stage 2 of meaningful use. This document, endorsed by the U.S. Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel, has gained popularity as it can contain large amounts of data in one file. Unfortunately, it too is still limited and often isn’t user friendly at the point of care. It is in many ways merely a jumping-off point that will hopefully facilitate improved data accessibility and ease of sharing.

To improve usability and confidence in data exchange, many practices and health systems have joined together to create Regional Health Information Organizations and provide some governance structure to the process of data exchange. We strongly recommend getting involved in such an organization and engaging in the process of standardization. Regardless of your position on the usefulness or practicality of sharing patient records, a few notions are indisputable: Interoperability is coming, and point-of-care data availability – if accurate, secure, and useful – can ultimately usher in the promise of better patient care.

Information should be secure

In the process of seeking easier data exchange, we cannot lose sight of the importance of data security. Health care entities need to feel confident the information they are sending electronically will stay private until it reaches its ultimate destination. An attempt to address this issue led to the development of the “direct” encryption standard in 2010. Also known as Direct Exchange and Direct Secure Messaging, it specifies a secure method for the exchange of Protected Health Information. Providers can take advantage of the security offered through Direct by developing their own infrastructure or engaging the services of a Health Information Service Provider. These are private, HIPAA-compliant data exchange services that serve a health care community and facilitate direct messaging between health care settings. Ultimately, the goal is to create a robust Nationwide Health Information Network and achieve true widespread health information exchange. But before we actually achieve this, there is one more element essential to interoperability and improving patient care.

The information should be useful

In the preliminary stages of EHR interoperability, attempts at meaningful information exchange have led to only modest success. Outside of private health systems that have developed their own proprietary interfaces, data extraction and sharing between disparate electronic platforms have yet to have a meaningful impact on patient care. In part, this is because the information is not provided to clinicians in a useful format. Even the CCD described above is often confusing and replete with extraneous information – filtering through it during a patient encounter can be tedious and frustrating. Also, ensuring data integrity can be a real challenge, not only technically, but also practically. Questions occur regularly, such as “Did the data come through in the correct fields?” or “Did the medical resident remember to include all of the medications or allergies associated with the patient?” Ultimately, physicians need to decide whether or not to trust the information they receive before making it a permanent part of a patient’s health record.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Contraception for adolescents

Approximately 750,000 adolescents become pregnant each year in the United States and nearly half of high school students report having had sexual intercourse. More than 80% of teenage pregnancies are unplanned and result in substantial health care costs, reduced earning potential, and increased health risks to both the mother and newborn. The American Academy of Pediatrics has released an updated policy statement that endorses long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) as a first-line consideration for adolescent contraception.

Sexual history taking and counseling

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) encourages the 5 P’s of sexual history taking: partners, prevention of pregnancy, protection from sexually transmitted infections (STIs), sexual practices, past history of STIs, and pregnancy. Confidentiality is advised for issues revolving around sexuality and sexually transmitted infections. Most states have legislation regarding minor consent for contraception, details of which can be found at the Guttmacher Institute. The adolescent should be encouraged to delay onset of sexual activity until they are ready, but abstinence should not be the only focus of contraception counseling, and adolescents should be supported in choosing, and adhering to, a method of contraception if they choose to be sexually active.

Methods of contraception

The updated AAP policy statement advises that physicians offer methods of contraception by discussing methods that are more effective preventing pregnancy as preferred over methods that are less effective. The effectiveness of all contraceptive methods is described by typical user rates and average user rates, expressed as the percent of women who become pregnant using the method for 1 year. The gap between perfect and typical user rates is explained by the amount of effort that is needed to reliably use the method. Typical user rates should guide decisions about contraceptive efficacy for adolescents. Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), specifically implants and intrauterine devices, are the most effective methods and should be encouraged for adolescents who desire birth control.

Progestin implants: Implanon and Nexplanon (Merck) are both implants containing the active metabolite of desogestrel, a progestin. Failure rates are less than 1% for the 3-year duration of the implant. Unpredictable bleeding or spotting is common, but implants are ideal for patients who desire an extended length of pregnancy prevention, without any schedule of adherence.

IUDs: These LARCs include two levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs (Mirena, 52 mg levonorgestrel and Skyla, 13.5 mg levonorgestrel, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals) and a copper-containing IUD (ParaGard, Teva ). All remain in place for 3-10 years, depending on brand, and have less than 1% failure rates. Known to be safe for use in nulliparous adolescents and patients with a previous episode of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), STI screening in the asymptomatic patient can be performed on the day of IUD insertion. Infection can be treated while the IUD remains in place. Contraindications to an IUD are current, symptomatic PID or current, purulent cervicitis.

Progestin-only injectable contraception: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA or Depo-Provera, Pfizer) is a long-acting progestin given as a single intramuscular injection every 13 weeks. DMPA has a typical use failure rate of 6% in the first year and can be initiated on the same day of the visit if the patient is not pregnant. Bone density reduction seems to recover once DMPA is discontinued and bone density does not need to be measured repeatedly. However, individual risk for osteoporosis must be assessed, and all patients need to be counseled on adequate calcium and vitamin D intake.

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs): COCs all contain an estrogen and a progestin. A follow-up visit is advised in 1-3 months after starting COCs, and no gynecologic examination is necessary prior to COC use. COC can be started on the same day as the office visit in nonpregnant adolescents. The typical use failure rates are 9%, and adolescents should be educated on what to do when pills are missed. A serious adverse event associated with COC is up to 4/10,000 risk of thromboembolism, but the risk is up to 20/10,000 during pregnancy. Rifampin and antiviral and antiepileptic medications can decrease efficacy. Contraindications to COCs should be reviewed prior to prescribing.

Contraceptive vaginal ring: The vaginal ring (NuvaRing, Merck) has similar efficacy and side effects as the COCs, since it releases a combination of estrogen and progestin. Inserted and left in place for 3 weeks, it is then removed for 1 week to induce withdrawal bleeding.

Transdermal contraceptive patch: The patch has similar a similar profile as COCs and the vaginal ring. It is placed on the upper arm, torso, or abdomen, left in place for 3 weeks, and removed for 1 week. Users have estrogen exposure of 1.6 times that of COC users, so there is a potential for increased thromboembolism with patch use. Obese patients have a higher risk of pregnancy with perfect use.

Progestin-only pills: Progestin only pills work by thickening cervical mucus. Failure rates are elevated, due to the need for strict, timed dosing schedule. They provide an option for the patient who has concerns with estrogen use.

Male condom use: Condoms remain a cheap, easily accessible form of contraception, used by 53% of female and 75% of male adolescents studied. With an 18% failure rate with typical use when used alone, condom use should be additional to another effective hormonal or long-acting contraceptive.

Emergency contraception: Various hormonal options can be used up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse. Plan B One-Step is a nonprescription form available for all women of childbearing potential.

Withdrawal: 57% of female adolescents report using this method. A 22% failure rate and lack of STI protection is important to relay to the patient and more effective contraception methods should be encouraged.

The Bottom Line

The IUD and implant should be considered safe, first-line contraceptive choices for adolescents. Physicians should counsel adolescent patients on all available methods of contraception in a developmentally appropriate, confidential manner that falls within the limits of state and federal law. Condoms should always be encouraged for STI protection.

Reference: Contraception for Adolescents. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1244-e56

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Roesing is an assistant director in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Approximately 750,000 adolescents become pregnant each year in the United States and nearly half of high school students report having had sexual intercourse. More than 80% of teenage pregnancies are unplanned and result in substantial health care costs, reduced earning potential, and increased health risks to both the mother and newborn. The American Academy of Pediatrics has released an updated policy statement that endorses long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) as a first-line consideration for adolescent contraception.

Sexual history taking and counseling

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) encourages the 5 P’s of sexual history taking: partners, prevention of pregnancy, protection from sexually transmitted infections (STIs), sexual practices, past history of STIs, and pregnancy. Confidentiality is advised for issues revolving around sexuality and sexually transmitted infections. Most states have legislation regarding minor consent for contraception, details of which can be found at the Guttmacher Institute. The adolescent should be encouraged to delay onset of sexual activity until they are ready, but abstinence should not be the only focus of contraception counseling, and adolescents should be supported in choosing, and adhering to, a method of contraception if they choose to be sexually active.

Methods of contraception

The updated AAP policy statement advises that physicians offer methods of contraception by discussing methods that are more effective preventing pregnancy as preferred over methods that are less effective. The effectiveness of all contraceptive methods is described by typical user rates and average user rates, expressed as the percent of women who become pregnant using the method for 1 year. The gap between perfect and typical user rates is explained by the amount of effort that is needed to reliably use the method. Typical user rates should guide decisions about contraceptive efficacy for adolescents. Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), specifically implants and intrauterine devices, are the most effective methods and should be encouraged for adolescents who desire birth control.

Progestin implants: Implanon and Nexplanon (Merck) are both implants containing the active metabolite of desogestrel, a progestin. Failure rates are less than 1% for the 3-year duration of the implant. Unpredictable bleeding or spotting is common, but implants are ideal for patients who desire an extended length of pregnancy prevention, without any schedule of adherence.

IUDs: These LARCs include two levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs (Mirena, 52 mg levonorgestrel and Skyla, 13.5 mg levonorgestrel, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals) and a copper-containing IUD (ParaGard, Teva ). All remain in place for 3-10 years, depending on brand, and have less than 1% failure rates. Known to be safe for use in nulliparous adolescents and patients with a previous episode of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), STI screening in the asymptomatic patient can be performed on the day of IUD insertion. Infection can be treated while the IUD remains in place. Contraindications to an IUD are current, symptomatic PID or current, purulent cervicitis.

Progestin-only injectable contraception: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA or Depo-Provera, Pfizer) is a long-acting progestin given as a single intramuscular injection every 13 weeks. DMPA has a typical use failure rate of 6% in the first year and can be initiated on the same day of the visit if the patient is not pregnant. Bone density reduction seems to recover once DMPA is discontinued and bone density does not need to be measured repeatedly. However, individual risk for osteoporosis must be assessed, and all patients need to be counseled on adequate calcium and vitamin D intake.

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs): COCs all contain an estrogen and a progestin. A follow-up visit is advised in 1-3 months after starting COCs, and no gynecologic examination is necessary prior to COC use. COC can be started on the same day as the office visit in nonpregnant adolescents. The typical use failure rates are 9%, and adolescents should be educated on what to do when pills are missed. A serious adverse event associated with COC is up to 4/10,000 risk of thromboembolism, but the risk is up to 20/10,000 during pregnancy. Rifampin and antiviral and antiepileptic medications can decrease efficacy. Contraindications to COCs should be reviewed prior to prescribing.

Contraceptive vaginal ring: The vaginal ring (NuvaRing, Merck) has similar efficacy and side effects as the COCs, since it releases a combination of estrogen and progestin. Inserted and left in place for 3 weeks, it is then removed for 1 week to induce withdrawal bleeding.

Transdermal contraceptive patch: The patch has similar a similar profile as COCs and the vaginal ring. It is placed on the upper arm, torso, or abdomen, left in place for 3 weeks, and removed for 1 week. Users have estrogen exposure of 1.6 times that of COC users, so there is a potential for increased thromboembolism with patch use. Obese patients have a higher risk of pregnancy with perfect use.

Progestin-only pills: Progestin only pills work by thickening cervical mucus. Failure rates are elevated, due to the need for strict, timed dosing schedule. They provide an option for the patient who has concerns with estrogen use.

Male condom use: Condoms remain a cheap, easily accessible form of contraception, used by 53% of female and 75% of male adolescents studied. With an 18% failure rate with typical use when used alone, condom use should be additional to another effective hormonal or long-acting contraceptive.

Emergency contraception: Various hormonal options can be used up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse. Plan B One-Step is a nonprescription form available for all women of childbearing potential.

Withdrawal: 57% of female adolescents report using this method. A 22% failure rate and lack of STI protection is important to relay to the patient and more effective contraception methods should be encouraged.

The Bottom Line

The IUD and implant should be considered safe, first-line contraceptive choices for adolescents. Physicians should counsel adolescent patients on all available methods of contraception in a developmentally appropriate, confidential manner that falls within the limits of state and federal law. Condoms should always be encouraged for STI protection.

Reference: Contraception for Adolescents. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1244-e56

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Roesing is an assistant director in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Approximately 750,000 adolescents become pregnant each year in the United States and nearly half of high school students report having had sexual intercourse. More than 80% of teenage pregnancies are unplanned and result in substantial health care costs, reduced earning potential, and increased health risks to both the mother and newborn. The American Academy of Pediatrics has released an updated policy statement that endorses long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) as a first-line consideration for adolescent contraception.

Sexual history taking and counseling

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) encourages the 5 P’s of sexual history taking: partners, prevention of pregnancy, protection from sexually transmitted infections (STIs), sexual practices, past history of STIs, and pregnancy. Confidentiality is advised for issues revolving around sexuality and sexually transmitted infections. Most states have legislation regarding minor consent for contraception, details of which can be found at the Guttmacher Institute. The adolescent should be encouraged to delay onset of sexual activity until they are ready, but abstinence should not be the only focus of contraception counseling, and adolescents should be supported in choosing, and adhering to, a method of contraception if they choose to be sexually active.

Methods of contraception

The updated AAP policy statement advises that physicians offer methods of contraception by discussing methods that are more effective preventing pregnancy as preferred over methods that are less effective. The effectiveness of all contraceptive methods is described by typical user rates and average user rates, expressed as the percent of women who become pregnant using the method for 1 year. The gap between perfect and typical user rates is explained by the amount of effort that is needed to reliably use the method. Typical user rates should guide decisions about contraceptive efficacy for adolescents. Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), specifically implants and intrauterine devices, are the most effective methods and should be encouraged for adolescents who desire birth control.

Progestin implants: Implanon and Nexplanon (Merck) are both implants containing the active metabolite of desogestrel, a progestin. Failure rates are less than 1% for the 3-year duration of the implant. Unpredictable bleeding or spotting is common, but implants are ideal for patients who desire an extended length of pregnancy prevention, without any schedule of adherence.

IUDs: These LARCs include two levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs (Mirena, 52 mg levonorgestrel and Skyla, 13.5 mg levonorgestrel, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals) and a copper-containing IUD (ParaGard, Teva ). All remain in place for 3-10 years, depending on brand, and have less than 1% failure rates. Known to be safe for use in nulliparous adolescents and patients with a previous episode of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), STI screening in the asymptomatic patient can be performed on the day of IUD insertion. Infection can be treated while the IUD remains in place. Contraindications to an IUD are current, symptomatic PID or current, purulent cervicitis.

Progestin-only injectable contraception: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA or Depo-Provera, Pfizer) is a long-acting progestin given as a single intramuscular injection every 13 weeks. DMPA has a typical use failure rate of 6% in the first year and can be initiated on the same day of the visit if the patient is not pregnant. Bone density reduction seems to recover once DMPA is discontinued and bone density does not need to be measured repeatedly. However, individual risk for osteoporosis must be assessed, and all patients need to be counseled on adequate calcium and vitamin D intake.

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs): COCs all contain an estrogen and a progestin. A follow-up visit is advised in 1-3 months after starting COCs, and no gynecologic examination is necessary prior to COC use. COC can be started on the same day as the office visit in nonpregnant adolescents. The typical use failure rates are 9%, and adolescents should be educated on what to do when pills are missed. A serious adverse event associated with COC is up to 4/10,000 risk of thromboembolism, but the risk is up to 20/10,000 during pregnancy. Rifampin and antiviral and antiepileptic medications can decrease efficacy. Contraindications to COCs should be reviewed prior to prescribing.

Contraceptive vaginal ring: The vaginal ring (NuvaRing, Merck) has similar efficacy and side effects as the COCs, since it releases a combination of estrogen and progestin. Inserted and left in place for 3 weeks, it is then removed for 1 week to induce withdrawal bleeding.

Transdermal contraceptive patch: The patch has similar a similar profile as COCs and the vaginal ring. It is placed on the upper arm, torso, or abdomen, left in place for 3 weeks, and removed for 1 week. Users have estrogen exposure of 1.6 times that of COC users, so there is a potential for increased thromboembolism with patch use. Obese patients have a higher risk of pregnancy with perfect use.

Progestin-only pills: Progestin only pills work by thickening cervical mucus. Failure rates are elevated, due to the need for strict, timed dosing schedule. They provide an option for the patient who has concerns with estrogen use.

Male condom use: Condoms remain a cheap, easily accessible form of contraception, used by 53% of female and 75% of male adolescents studied. With an 18% failure rate with typical use when used alone, condom use should be additional to another effective hormonal or long-acting contraceptive.

Emergency contraception: Various hormonal options can be used up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse. Plan B One-Step is a nonprescription form available for all women of childbearing potential.

Withdrawal: 57% of female adolescents report using this method. A 22% failure rate and lack of STI protection is important to relay to the patient and more effective contraception methods should be encouraged.

The Bottom Line

The IUD and implant should be considered safe, first-line contraceptive choices for adolescents. Physicians should counsel adolescent patients on all available methods of contraception in a developmentally appropriate, confidential manner that falls within the limits of state and federal law. Condoms should always be encouraged for STI protection.

Reference: Contraception for Adolescents. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1244-e56

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Roesing is an assistant director in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Clinical Guidelines: Obstructive sleep apnea

The Greek word apnea literally translates to “without breath.” More than 18 million American adults experience several moments “without breath” every night, according to the National Sleep Foundation. These pauses in breathing can last from a few seconds to minutes and can occur up to 30 times per hour or more. There are three types of apnea: obstructive, central, and mixed. Of the three, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common. If left untreated, sleep apnea can have serious or life-threatening consequences, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and day-time sleepiness that can lead to car accidents, depression, and headaches.

The significance of this condition has led the American College of Physicians (ACP) to publish guidelines regarding the management of OSA in adults. These guidelines are intended to provide clinicians with evidence-based recommendations that will have positive, long-term effects on patients’ cardiovascular risk, as well overall health and quality of life.

Recommendation 1: Encourage weight loss in all overweight and obese patients diagnosed with OSA.

There is strong evidence that shows how weight loss interventions can reduce the apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) and improve symptoms. The apnea/hypopnea index is a measure of the number of apnea and hypopnea episodes per hour of monitored sleep. According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, an OSA diagnosis is defined by ≥ 15 events/hr (with or without OSA symptoms) or ≥ 5 events/hr with OSA symptoms. Severity of OSA is classified as:

• Mild: 5-14 events/hr

• Moderate: 15-30 events/hr

• Severe: >30 events/hr

In patients with mild OSA, weight loss alone can be sufficient to normalize the apnea/hypopnea index, thereby reducing the need for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). In those with persistent OSA, weight loss can reduce the amount of PAP pressure required, which can increase tolerance of and adherence to CPAP. However, weight loss alone may not be sufficient to reduce OSA in all patients. In obese patients, weight loss must be encouraged with another primary treatment. In a meta-analysis of 342 patients in 12 published trials, weight loss produced substantial reductions in apnea/hypopnea index; however, the majority of patients continued to have persistent OSA after significant weight reduction. So, while weight loss should always be encouraged in patients with OSA, it should not be assumed that this intervention alone will be sufficient; patients need to be reassessed to determine whether OSA persists and if so, CPAP should be continued.

Recommendation 2: Prescribe CPAP as the initial therapy for patients diagnosed with OSA.

CPAP is as critical as it is effective not only in reducing the AHI but also in improving sleep continuity and architecture and decreasing the sleep hypoxia that is associated with OSA. Because of the lack of adherence to CPAP, many new features have been added including heated humidification, broad pressure adjustments, and expiratory pressure relief; while many of these features mildly improve patients’ preferences, there is no evidence to suggest that these changes improve efficacy or adherence. Again, it is critical that each patient’s needs be taken into consideration. Some patients, particularly those with mild forms of OSA, may not need CPAP and instead, may benefit from positional therapy or weight loss. Other therapy such as surgery or mandibular advancement devices (MADs) may be better suited for some patients despite their lessor effectiveness when compared with CPAP.

Recommendation 3: Consider MAD as an alternate therapy to CPAP for patients diagnosed with OSA who prefer MAD or for those with adverse effects associated with CPAP.

MADs have been recommended for patients with moderate to severe OSA, those with apnea/hypopnea index values between 18-40 events/hour, and for individuals who experienced adverse events on CPAP or who can’t tolerate using it. While CPAP still is considered to be primary therapy, for those who must use a mandibular advancement device, it can often be very effective. Patients may find it easier to be compliant with MAD than with CPAP. One group of researchers observed that MADs were able to provide appropriate decrease in obstructive events in 70% of patients with mild OSA, 48% of those with moderate OSA, and 42% of those with severe OSA (Chest 2011:139:1331-9). The ACP concluded that, without sufficient evidence, it is unclear which patients will benefit from MADs. Data from several studies show that patients who are younger and thinner, with less severe OSA, may benefit more from the use of MADs. Although the ACP does not recommend surgery or pharmaceutical therapy for OSA, the ACP does acknowledge that it may work for certain patients. However, the documented efficacy rate ranges from 20%-100%, thereby making it challenging to determine its true effect.

Bottom Line

The ACP recommends weight loss for all overweight patients with OSA. CPAP is first-line therapy, particularly if weight loss cannot be sustained or does not sufficiently lessen symptoms. For selected patients who are younger and thinner, with less severe OSA, or for those patients who are unable to tolerate CPAP, MADs can be used as an alternative first-line therapy with moderate success.

Reference

Qaseem A., Holty J.C., Owens D. et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: a Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;161:210-20.

Dr. Grover is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The Greek word apnea literally translates to “without breath.” More than 18 million American adults experience several moments “without breath” every night, according to the National Sleep Foundation. These pauses in breathing can last from a few seconds to minutes and can occur up to 30 times per hour or more. There are three types of apnea: obstructive, central, and mixed. Of the three, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common. If left untreated, sleep apnea can have serious or life-threatening consequences, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and day-time sleepiness that can lead to car accidents, depression, and headaches.

The significance of this condition has led the American College of Physicians (ACP) to publish guidelines regarding the management of OSA in adults. These guidelines are intended to provide clinicians with evidence-based recommendations that will have positive, long-term effects on patients’ cardiovascular risk, as well overall health and quality of life.

Recommendation 1: Encourage weight loss in all overweight and obese patients diagnosed with OSA.

There is strong evidence that shows how weight loss interventions can reduce the apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) and improve symptoms. The apnea/hypopnea index is a measure of the number of apnea and hypopnea episodes per hour of monitored sleep. According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, an OSA diagnosis is defined by ≥ 15 events/hr (with or without OSA symptoms) or ≥ 5 events/hr with OSA symptoms. Severity of OSA is classified as:

• Mild: 5-14 events/hr

• Moderate: 15-30 events/hr

• Severe: >30 events/hr

In patients with mild OSA, weight loss alone can be sufficient to normalize the apnea/hypopnea index, thereby reducing the need for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). In those with persistent OSA, weight loss can reduce the amount of PAP pressure required, which can increase tolerance of and adherence to CPAP. However, weight loss alone may not be sufficient to reduce OSA in all patients. In obese patients, weight loss must be encouraged with another primary treatment. In a meta-analysis of 342 patients in 12 published trials, weight loss produced substantial reductions in apnea/hypopnea index; however, the majority of patients continued to have persistent OSA after significant weight reduction. So, while weight loss should always be encouraged in patients with OSA, it should not be assumed that this intervention alone will be sufficient; patients need to be reassessed to determine whether OSA persists and if so, CPAP should be continued.

Recommendation 2: Prescribe CPAP as the initial therapy for patients diagnosed with OSA.

CPAP is as critical as it is effective not only in reducing the AHI but also in improving sleep continuity and architecture and decreasing the sleep hypoxia that is associated with OSA. Because of the lack of adherence to CPAP, many new features have been added including heated humidification, broad pressure adjustments, and expiratory pressure relief; while many of these features mildly improve patients’ preferences, there is no evidence to suggest that these changes improve efficacy or adherence. Again, it is critical that each patient’s needs be taken into consideration. Some patients, particularly those with mild forms of OSA, may not need CPAP and instead, may benefit from positional therapy or weight loss. Other therapy such as surgery or mandibular advancement devices (MADs) may be better suited for some patients despite their lessor effectiveness when compared with CPAP.

Recommendation 3: Consider MAD as an alternate therapy to CPAP for patients diagnosed with OSA who prefer MAD or for those with adverse effects associated with CPAP.

MADs have been recommended for patients with moderate to severe OSA, those with apnea/hypopnea index values between 18-40 events/hour, and for individuals who experienced adverse events on CPAP or who can’t tolerate using it. While CPAP still is considered to be primary therapy, for those who must use a mandibular advancement device, it can often be very effective. Patients may find it easier to be compliant with MAD than with CPAP. One group of researchers observed that MADs were able to provide appropriate decrease in obstructive events in 70% of patients with mild OSA, 48% of those with moderate OSA, and 42% of those with severe OSA (Chest 2011:139:1331-9). The ACP concluded that, without sufficient evidence, it is unclear which patients will benefit from MADs. Data from several studies show that patients who are younger and thinner, with less severe OSA, may benefit more from the use of MADs. Although the ACP does not recommend surgery or pharmaceutical therapy for OSA, the ACP does acknowledge that it may work for certain patients. However, the documented efficacy rate ranges from 20%-100%, thereby making it challenging to determine its true effect.

Bottom Line

The ACP recommends weight loss for all overweight patients with OSA. CPAP is first-line therapy, particularly if weight loss cannot be sustained or does not sufficiently lessen symptoms. For selected patients who are younger and thinner, with less severe OSA, or for those patients who are unable to tolerate CPAP, MADs can be used as an alternative first-line therapy with moderate success.

Reference

Qaseem A., Holty J.C., Owens D. et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: a Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;161:210-20.

Dr. Grover is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The Greek word apnea literally translates to “without breath.” More than 18 million American adults experience several moments “without breath” every night, according to the National Sleep Foundation. These pauses in breathing can last from a few seconds to minutes and can occur up to 30 times per hour or more. There are three types of apnea: obstructive, central, and mixed. Of the three, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common. If left untreated, sleep apnea can have serious or life-threatening consequences, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and day-time sleepiness that can lead to car accidents, depression, and headaches.

The significance of this condition has led the American College of Physicians (ACP) to publish guidelines regarding the management of OSA in adults. These guidelines are intended to provide clinicians with evidence-based recommendations that will have positive, long-term effects on patients’ cardiovascular risk, as well overall health and quality of life.

Recommendation 1: Encourage weight loss in all overweight and obese patients diagnosed with OSA.

There is strong evidence that shows how weight loss interventions can reduce the apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) and improve symptoms. The apnea/hypopnea index is a measure of the number of apnea and hypopnea episodes per hour of monitored sleep. According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, an OSA diagnosis is defined by ≥ 15 events/hr (with or without OSA symptoms) or ≥ 5 events/hr with OSA symptoms. Severity of OSA is classified as:

• Mild: 5-14 events/hr

• Moderate: 15-30 events/hr

• Severe: >30 events/hr

In patients with mild OSA, weight loss alone can be sufficient to normalize the apnea/hypopnea index, thereby reducing the need for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). In those with persistent OSA, weight loss can reduce the amount of PAP pressure required, which can increase tolerance of and adherence to CPAP. However, weight loss alone may not be sufficient to reduce OSA in all patients. In obese patients, weight loss must be encouraged with another primary treatment. In a meta-analysis of 342 patients in 12 published trials, weight loss produced substantial reductions in apnea/hypopnea index; however, the majority of patients continued to have persistent OSA after significant weight reduction. So, while weight loss should always be encouraged in patients with OSA, it should not be assumed that this intervention alone will be sufficient; patients need to be reassessed to determine whether OSA persists and if so, CPAP should be continued.

Recommendation 2: Prescribe CPAP as the initial therapy for patients diagnosed with OSA.

CPAP is as critical as it is effective not only in reducing the AHI but also in improving sleep continuity and architecture and decreasing the sleep hypoxia that is associated with OSA. Because of the lack of adherence to CPAP, many new features have been added including heated humidification, broad pressure adjustments, and expiratory pressure relief; while many of these features mildly improve patients’ preferences, there is no evidence to suggest that these changes improve efficacy or adherence. Again, it is critical that each patient’s needs be taken into consideration. Some patients, particularly those with mild forms of OSA, may not need CPAP and instead, may benefit from positional therapy or weight loss. Other therapy such as surgery or mandibular advancement devices (MADs) may be better suited for some patients despite their lessor effectiveness when compared with CPAP.

Recommendation 3: Consider MAD as an alternate therapy to CPAP for patients diagnosed with OSA who prefer MAD or for those with adverse effects associated with CPAP.

MADs have been recommended for patients with moderate to severe OSA, those with apnea/hypopnea index values between 18-40 events/hour, and for individuals who experienced adverse events on CPAP or who can’t tolerate using it. While CPAP still is considered to be primary therapy, for those who must use a mandibular advancement device, it can often be very effective. Patients may find it easier to be compliant with MAD than with CPAP. One group of researchers observed that MADs were able to provide appropriate decrease in obstructive events in 70% of patients with mild OSA, 48% of those with moderate OSA, and 42% of those with severe OSA (Chest 2011:139:1331-9). The ACP concluded that, without sufficient evidence, it is unclear which patients will benefit from MADs. Data from several studies show that patients who are younger and thinner, with less severe OSA, may benefit more from the use of MADs. Although the ACP does not recommend surgery or pharmaceutical therapy for OSA, the ACP does acknowledge that it may work for certain patients. However, the documented efficacy rate ranges from 20%-100%, thereby making it challenging to determine its true effect.

Bottom Line

The ACP recommends weight loss for all overweight patients with OSA. CPAP is first-line therapy, particularly if weight loss cannot be sustained or does not sufficiently lessen symptoms. For selected patients who are younger and thinner, with less severe OSA, or for those patients who are unable to tolerate CPAP, MADs can be used as an alternative first-line therapy with moderate success.

Reference

Qaseem A., Holty J.C., Owens D. et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: a Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;161:210-20.

Dr. Grover is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Meaningful use – Stage 2 (Part 1 of 2)

The words "meaningful use" have been making providers cringe for more than 2 years now. Those clinicians who worked hard to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 1 requirements now must go on to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 2 requirements. We recently heard one of our colleagues describe stage 2 of meaningful use as reminiscent of the 1978 movie "Jaws 2," the ads for which ran with the tagline: "Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water..."

As you may be aware, on August 29th the Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. This only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time due to vendor delays. Unfortunately, this flexibility does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new workflows (we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility). Regardless of stage or year, everyone is on a 90-day reporting period for 2014, but remember that 2015 will require a full year of reporting (January through December). So even if you qualify for the flexibility and opt to stick with the Stage 1 measures, you’ll need to be ready to hit the ground running with Stage 2 as soon as the ball drops on January 1st, 2015.

The government’s intent with the EHR incentive program is to ensure that practitioners use an EHR to do more than what could otherwise be done on a paper note. As we review the criteria that must be met for stage 2 of meaningful use, we will see the inclusion of menu items and quality measures that are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care, population management (even for patients who might not come in to the office), and physician-patient communication. By articulating these goals we can see that they are very different from what most practitioners perceive to be the main outcome of the meaningful use rules: the creation of a lot of unnecessary busywork in the office that yields very little benefit for practitioners or patients.

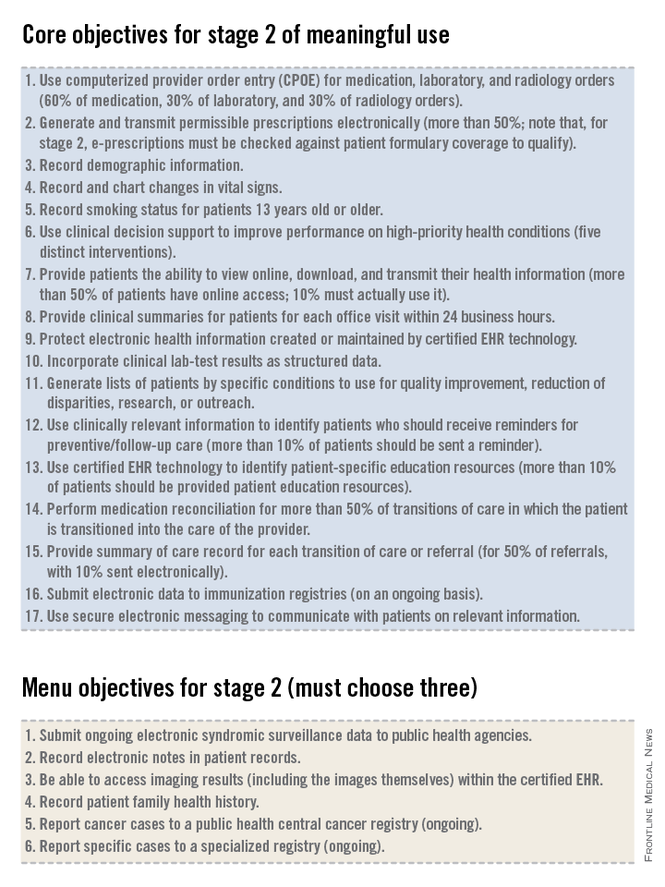

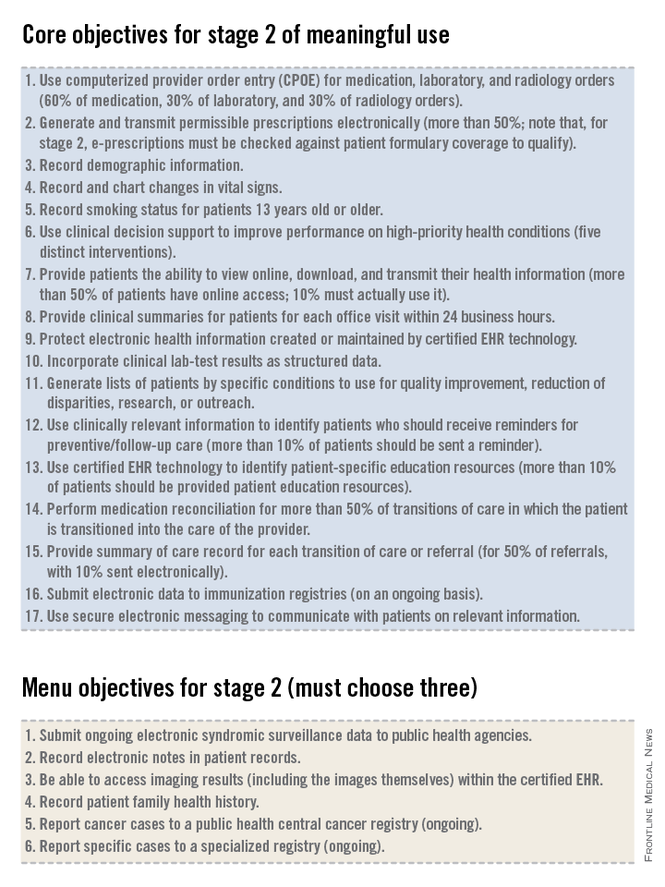

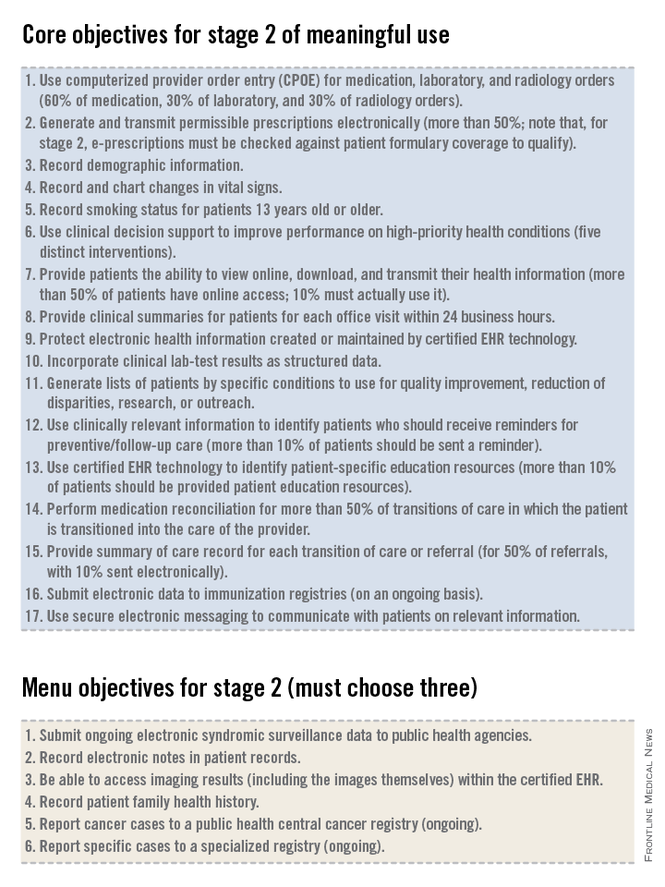

The EHR incentive program consists of three stages.

• Stage 1, which many practitioners have already accomplished and received incentive dollars for completing, focused on basic data capture.

• Stage 2, which focuses on more advanced processes including additional requirements for e-prescribing, incorporating lab results into the record, electronic transmission of patient summaries across systems, and increased patient engagement.