User login

Buprenorphine endangers lives and health of children

Eleven children died from exposure to buprenorphine – a drug used to treat opioid exposure – from 2007 to 2016, mostly very young children who accidentally ingested the drug.

Four deaths, however, were teens who took buprenorphine recreationally or used it in a suicide attempt, according to a new database review by Sara Post, MS, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and her associates.

“In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement advocating for increased access to buprenorphine for opioid-addicted adolescents in primary care settings,” the authors noted. “This recommendation is warranted because of the high and increasing prevalence of opioid dependence among adolescents. However, caution should be used, because increased prescriptions among adolescents could lead to increased diversion and abuse and increased access to younger children in the home. Therefore, patient education for adolescents should include information about the dangers of misusing and/or abusing prescription drugs and the proper storage of medications.”

The deaths comprise a small fraction of the 11,275 children aged 19 years and younger whose buprenorphine ingestions were reported to a poison control center during that time, the investigators said. Nevertheless, almost half (45%) of the exposed children were admitted to a health care facility – with 22% needing treatment in a critical care unit.

The rate of exposures was highest during the years when only tablet formulations were available and fell after film was introduced, wrote Ms. Post, a medical student at the Northeast Ohio Medical University in Rootstown, and her colleagues. But after 2013, the rate held steady, at about 38 exposures per 1 million children per year.

Childproof packaging for all buprenorphine formulations could help protect younger children, and education could help protect older ones, she and her coinvestigators said. Manufacturers should use unit-dose packaging for all buprenorphine products to help prevent unintentional exposure among young children. Health care providers should inform caregivers of young children about the dangers of buprenorphine exposure and provide instructions on proper storage and disposal of medications. Adolescents should receive information regarding the risks of substance abuse and misuse.”

Ms. Post and her colleagues analyzed calls to poison control centers affiliated with the National Poison Data System from 2007 to 2016. During that time, the centers received 11,275 calls about buprenorphine exposure among children and adolescents 19 years and younger.

The mean age of exposure in children was about 4 years; children younger than 6 years comprised 86% of the exposures (9,709).

The investigators noted temporal trends in exposure rates in this group. From 2007 to 2013, the rate increased by 215%, peaking at 20 per 1 million in 2010. A decline followed, with exposure dropping to 12 per 1 million in 2013, before rising again to 13 in 2016.

The increase “was likely attributable to the increasing number of buprenorphine prescriptions dispensed since the Food and Drug Administration approved its use as a treatment of opioid dependence in 2002,” Ms. Post and her colleagues wrote.

The transient decrease may have been related to a shift in adult prescribing patterns, as the drug was prescribed less often to those in their 20s and gradually given more often to people aged 40-59 years.

The decrease also was probably related to the packaging shift from tablet to film. “In 2013, the leading brand-name tablets were voluntarily withdrawn from the U.S. market because of potential risk of unintentional pediatric exposures,” the team wrote. Unfortunately, the film packaging didn’t completely deter some children; from 2013 to 2016, there was a 30% increase in the frequency of exposures to buprenorphine film.

The bulk of exposures were unintentional (98%) and involved ingestion of a single buprenorphine product. However, the authors noted, even a single adult therapeutic dose can be extremely dangerous to a small child.

“Therapeutic doses of buprenorphine-naloxone for pediatric patients are 2 to 6 mcg/kg, so ingestion of a single 2-mg sublingual tablet in a 10-kg child can result in more than a 30-fold overdose. This is particularly dangerous, because children exposed to buprenorphine do not display the ‘ceiling effect’ reported in adults, in which escalating doses do not lead to additional increases in respiratory depression,” Ms. Post and her coauthors said.

This was reflected in the serious clinical effects experienced: respiratory depression, bradycardia, coma, cyanosis, respiratory arrest, seizure, and cardiac arrest. These youngest children experienced the most serious outcomes, with half requiring a hospital admittance and 21% experiencing a serious medical outcome. Seven died, six of whom were 2 years or younger.

There were 315 (3%) exposures in children aged 6-12 years; most of these (83%) were either unintentional or therapeutic errors (18%). About 30% of the group required hospital admission and about 12% experienced a serious medical outcome. There were no fatalities among this group, the investigators noted.

Among adolescents aged 13-19 years, there were 1,251 (11%) exposures and four deaths. The bulk of these (77%) was intentional, with suspected suicide accounting for 12%, and 30% involving more than one substance. The exposure rate followed the same general trends, rising to a peak of about 6 per 1 million in 2010 and the falling and leveling off at about 3 per 1 million in 2016, they said.

About 22% of teen exposures required hospital admission, with 11% needing treatment in a critical care unit. The four deaths, one of which was a suicide, all involved multiple substances (benzodiazepines, alcohol, and marijuana).

Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

Eleven children died from exposure to buprenorphine – a drug used to treat opioid exposure – from 2007 to 2016, mostly very young children who accidentally ingested the drug.

Four deaths, however, were teens who took buprenorphine recreationally or used it in a suicide attempt, according to a new database review by Sara Post, MS, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and her associates.

“In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement advocating for increased access to buprenorphine for opioid-addicted adolescents in primary care settings,” the authors noted. “This recommendation is warranted because of the high and increasing prevalence of opioid dependence among adolescents. However, caution should be used, because increased prescriptions among adolescents could lead to increased diversion and abuse and increased access to younger children in the home. Therefore, patient education for adolescents should include information about the dangers of misusing and/or abusing prescription drugs and the proper storage of medications.”

The deaths comprise a small fraction of the 11,275 children aged 19 years and younger whose buprenorphine ingestions were reported to a poison control center during that time, the investigators said. Nevertheless, almost half (45%) of the exposed children were admitted to a health care facility – with 22% needing treatment in a critical care unit.

The rate of exposures was highest during the years when only tablet formulations were available and fell after film was introduced, wrote Ms. Post, a medical student at the Northeast Ohio Medical University in Rootstown, and her colleagues. But after 2013, the rate held steady, at about 38 exposures per 1 million children per year.

Childproof packaging for all buprenorphine formulations could help protect younger children, and education could help protect older ones, she and her coinvestigators said. Manufacturers should use unit-dose packaging for all buprenorphine products to help prevent unintentional exposure among young children. Health care providers should inform caregivers of young children about the dangers of buprenorphine exposure and provide instructions on proper storage and disposal of medications. Adolescents should receive information regarding the risks of substance abuse and misuse.”

Ms. Post and her colleagues analyzed calls to poison control centers affiliated with the National Poison Data System from 2007 to 2016. During that time, the centers received 11,275 calls about buprenorphine exposure among children and adolescents 19 years and younger.

The mean age of exposure in children was about 4 years; children younger than 6 years comprised 86% of the exposures (9,709).

The investigators noted temporal trends in exposure rates in this group. From 2007 to 2013, the rate increased by 215%, peaking at 20 per 1 million in 2010. A decline followed, with exposure dropping to 12 per 1 million in 2013, before rising again to 13 in 2016.

The increase “was likely attributable to the increasing number of buprenorphine prescriptions dispensed since the Food and Drug Administration approved its use as a treatment of opioid dependence in 2002,” Ms. Post and her colleagues wrote.

The transient decrease may have been related to a shift in adult prescribing patterns, as the drug was prescribed less often to those in their 20s and gradually given more often to people aged 40-59 years.

The decrease also was probably related to the packaging shift from tablet to film. “In 2013, the leading brand-name tablets were voluntarily withdrawn from the U.S. market because of potential risk of unintentional pediatric exposures,” the team wrote. Unfortunately, the film packaging didn’t completely deter some children; from 2013 to 2016, there was a 30% increase in the frequency of exposures to buprenorphine film.

The bulk of exposures were unintentional (98%) and involved ingestion of a single buprenorphine product. However, the authors noted, even a single adult therapeutic dose can be extremely dangerous to a small child.

“Therapeutic doses of buprenorphine-naloxone for pediatric patients are 2 to 6 mcg/kg, so ingestion of a single 2-mg sublingual tablet in a 10-kg child can result in more than a 30-fold overdose. This is particularly dangerous, because children exposed to buprenorphine do not display the ‘ceiling effect’ reported in adults, in which escalating doses do not lead to additional increases in respiratory depression,” Ms. Post and her coauthors said.

This was reflected in the serious clinical effects experienced: respiratory depression, bradycardia, coma, cyanosis, respiratory arrest, seizure, and cardiac arrest. These youngest children experienced the most serious outcomes, with half requiring a hospital admittance and 21% experiencing a serious medical outcome. Seven died, six of whom were 2 years or younger.

There were 315 (3%) exposures in children aged 6-12 years; most of these (83%) were either unintentional or therapeutic errors (18%). About 30% of the group required hospital admission and about 12% experienced a serious medical outcome. There were no fatalities among this group, the investigators noted.

Among adolescents aged 13-19 years, there were 1,251 (11%) exposures and four deaths. The bulk of these (77%) was intentional, with suspected suicide accounting for 12%, and 30% involving more than one substance. The exposure rate followed the same general trends, rising to a peak of about 6 per 1 million in 2010 and the falling and leveling off at about 3 per 1 million in 2016, they said.

About 22% of teen exposures required hospital admission, with 11% needing treatment in a critical care unit. The four deaths, one of which was a suicide, all involved multiple substances (benzodiazepines, alcohol, and marijuana).

Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

Eleven children died from exposure to buprenorphine – a drug used to treat opioid exposure – from 2007 to 2016, mostly very young children who accidentally ingested the drug.

Four deaths, however, were teens who took buprenorphine recreationally or used it in a suicide attempt, according to a new database review by Sara Post, MS, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and her associates.

“In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement advocating for increased access to buprenorphine for opioid-addicted adolescents in primary care settings,” the authors noted. “This recommendation is warranted because of the high and increasing prevalence of opioid dependence among adolescents. However, caution should be used, because increased prescriptions among adolescents could lead to increased diversion and abuse and increased access to younger children in the home. Therefore, patient education for adolescents should include information about the dangers of misusing and/or abusing prescription drugs and the proper storage of medications.”

The deaths comprise a small fraction of the 11,275 children aged 19 years and younger whose buprenorphine ingestions were reported to a poison control center during that time, the investigators said. Nevertheless, almost half (45%) of the exposed children were admitted to a health care facility – with 22% needing treatment in a critical care unit.

The rate of exposures was highest during the years when only tablet formulations were available and fell after film was introduced, wrote Ms. Post, a medical student at the Northeast Ohio Medical University in Rootstown, and her colleagues. But after 2013, the rate held steady, at about 38 exposures per 1 million children per year.

Childproof packaging for all buprenorphine formulations could help protect younger children, and education could help protect older ones, she and her coinvestigators said. Manufacturers should use unit-dose packaging for all buprenorphine products to help prevent unintentional exposure among young children. Health care providers should inform caregivers of young children about the dangers of buprenorphine exposure and provide instructions on proper storage and disposal of medications. Adolescents should receive information regarding the risks of substance abuse and misuse.”

Ms. Post and her colleagues analyzed calls to poison control centers affiliated with the National Poison Data System from 2007 to 2016. During that time, the centers received 11,275 calls about buprenorphine exposure among children and adolescents 19 years and younger.

The mean age of exposure in children was about 4 years; children younger than 6 years comprised 86% of the exposures (9,709).

The investigators noted temporal trends in exposure rates in this group. From 2007 to 2013, the rate increased by 215%, peaking at 20 per 1 million in 2010. A decline followed, with exposure dropping to 12 per 1 million in 2013, before rising again to 13 in 2016.

The increase “was likely attributable to the increasing number of buprenorphine prescriptions dispensed since the Food and Drug Administration approved its use as a treatment of opioid dependence in 2002,” Ms. Post and her colleagues wrote.

The transient decrease may have been related to a shift in adult prescribing patterns, as the drug was prescribed less often to those in their 20s and gradually given more often to people aged 40-59 years.

The decrease also was probably related to the packaging shift from tablet to film. “In 2013, the leading brand-name tablets were voluntarily withdrawn from the U.S. market because of potential risk of unintentional pediatric exposures,” the team wrote. Unfortunately, the film packaging didn’t completely deter some children; from 2013 to 2016, there was a 30% increase in the frequency of exposures to buprenorphine film.

The bulk of exposures were unintentional (98%) and involved ingestion of a single buprenorphine product. However, the authors noted, even a single adult therapeutic dose can be extremely dangerous to a small child.

“Therapeutic doses of buprenorphine-naloxone for pediatric patients are 2 to 6 mcg/kg, so ingestion of a single 2-mg sublingual tablet in a 10-kg child can result in more than a 30-fold overdose. This is particularly dangerous, because children exposed to buprenorphine do not display the ‘ceiling effect’ reported in adults, in which escalating doses do not lead to additional increases in respiratory depression,” Ms. Post and her coauthors said.

This was reflected in the serious clinical effects experienced: respiratory depression, bradycardia, coma, cyanosis, respiratory arrest, seizure, and cardiac arrest. These youngest children experienced the most serious outcomes, with half requiring a hospital admittance and 21% experiencing a serious medical outcome. Seven died, six of whom were 2 years or younger.

There were 315 (3%) exposures in children aged 6-12 years; most of these (83%) were either unintentional or therapeutic errors (18%). About 30% of the group required hospital admission and about 12% experienced a serious medical outcome. There were no fatalities among this group, the investigators noted.

Among adolescents aged 13-19 years, there were 1,251 (11%) exposures and four deaths. The bulk of these (77%) was intentional, with suspected suicide accounting for 12%, and 30% involving more than one substance. The exposure rate followed the same general trends, rising to a peak of about 6 per 1 million in 2010 and the falling and leveling off at about 3 per 1 million in 2016, they said.

About 22% of teen exposures required hospital admission, with 11% needing treatment in a critical care unit. The four deaths, one of which was a suicide, all involved multiple substances (benzodiazepines, alcohol, and marijuana).

Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Buprenorphine ingestion remains a threat to children, especially those younger than 6 years.

Major finding: From 2007 to 2016, 11,275 exposures were reported; 11 children died.

Study details: The database review looked at records from the National Poison Data System.

Disclosures: Ms. Post received a research stipend from the National Student Injury Research Training Program while she worked on the study. The coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Post et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20173652.

Herpesvirus infections may have a pathogenic link to Alzheimer’s disease

Two nearly ubiquitous herpes viruses are abundant in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and appear to integrate themselves into the patient’s own genome, where the viruses play havoc with genes involved in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, among other things, a new study reports.

The genomic analysis of hundreds of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain samples found human herpesvirus 6a and 7 (HHV-6a, HHV-7) in the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus, the initial sites of beta-amyloid overexpression in the disease, first authors Benjamin Readhead, MBBS, Jean-Vianney Haure-Mirande, PhD, and colleagues reported June 21 in Neuron.

The viruses appear to interact with genes implicated in the risk for AD and for regulation and processing of the amyloid precursor protein, including presenilin-1 (PSEN1), BACE1, BIN1, PICALM, and several others. Their presence was directly related to the donors’ Clinical Dementia Rating score, and a mouse model suggests a potential pathway linking HHV infection and brain amyloidosis through a microRNA that’s been previously linked to AD.

It’s impossible to say whether HHV-6a and HHV-7 infections, which occur in nearly 100% of small children, trigger late-life amyloid pathology or whether the viruses reactivate and cross into the brain after amyloid-related damage has already begun, said Keith Fargo, PhD, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. But the data in this paper are strong enough to give real credence, for the first time, to the idea that Alzheimer’s disease may have an infective component.

“This paper, which is quite dense, presents an idea we have seen before, but which has been mostly dismissed,” Dr. Fargo said in an interview. “For the first time, a world-class group of researchers have completed a landmark paper packed with evidence. It’s not definitive evidence yet, but it will certainly bring that hypothesis into the mainstream in a way it has not been before. The Alzheimer’s research world will sit up and take notice.”

The viruses were present in about 20% of AD brain samples taken from four separate brain banks, but not in control samples or in samples from patients with other neurodegenerative diseases. The commonality suggests that the association is real, and something unique to Alzheimer’s, said Sam Gandy, MD, PhD, one of the paper’s senior authors, and a professor of neurology at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

Joel T. Dudley, PhD, director of the Mount Sinai Institute for Next Generation Healthcare, was the other senior author.

“It seems obvious to us that the AD brains around this country are accumulating the genomes of this particular pair of viruses,” Dr. Gandy said in an interview. “For whatever reason, these people were accumulating the genomes of an infectious agent which crossed the blood-brain barrier, went into the brain, and was present there when they were dying of AD. It was not a remote relationship, such as we would see with serology. This was there when they were dying, and it’s hard to imagine it was doing anything good.”

HHV6 causes a primary illness – roseola – when it first enters the body, usually in early childhood. It then enters a life-long latency, but can reactivate in adulthood, according to the HHV-6 Foundation.

“Reactivation can occur in the brain, lungs, heart, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract, especially in patients with immune deficiencies and transplant patients. In some cases, HHV-6 reactivation in the brain tissue can cause cognitive dysfunction, permanent disability, and death.”

The Neuron paper describes several separate investigations that led the team to conclude that HHV-6a and HHV-7 may be implicated in AD pathogenesis.

Dr. Gandy, Dr. Dudley, and their team were not looking for potentially infective agents when they started down this road 5 years ago. Instead, they wanted to see how genes and gene networks change as patients progress from preclinical Alzheimer’s to Alzheimer’s dementia, in the hope of finding novel drug targets.

“This was a surprise result. We were looking for genes differentially expressed as AD progressed. Instead, we found gene expression changes associated with viral infections.”

A transcriptome analysis pointed to microRNA-155, a molecule that helps control viral infections. This lead the team to look for viral RNA in 643 brain samples from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank. “What we found was that HHV-6a and HHV-7 appeared to be driving these changes,” Dr. Gandy said.

HHV-6a interacted with some of the most well-known AD risk genes, Dr. Gandy said.

“The story is full of tantalizing, yet not quite definitive pieces. Presenilin 1 is the most common cause of genetic forms of AD. There are about two dozen genes associated with late-onset sporadic AD. As we scrutinized the computational analysis of the data, whom should we find lurking there among the genes regulated by HHV-6a and HHV-7 but several of our old gene friends from conventional AD genetics and genome-wide association studies: PSEN1, BIN1, PICALM, among others, all of which are linked to causing AD.”

They validated the results from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank in three other data sets: the Religious Orders Study (300 samples from AD patients and healthy controls) the Rush Memory and Aging Project (298 samples from AD patients and healthy controls), and a collection of temporal cortex studies from the Mayo Clinic (278 samples from patients with AD, pathological aging, or progressive supranuclear palsy, and healthy controls).

Again, they saw HHV-6a and HHV-7 in the AD samples, but not in the normal controls or those with pathological aging. Compared with the AD samples, HHV-7 was present in the progressive supranuclear palsy samples, but HHV-6a was reduced.

Whole-exome sequencing found HHV-6a DNA integrated into host DNA. “This may indicate that the HHV-6a DNA that we find as more abundant in AD reflects HHV-6A that has undergone reactivation from a chromosomally integrated form, although we have not evaluated this directly,” Dr. Readhead and his co-investigators wrote in the paper.

Dr. Gandy said that the presence of the two viruses correlated directly with the patients’ Clinical Dementia Rating scale score, neuritic plaque density across multiple regions, and Braak stage, a measure of neurofibrillary tangles.

Another investigation looked at the fractions of the four major brain cells (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells) and their relationship to viral RNA. HHV-6a was associated with decreases in the neuronal content of fractions from multiple brain regions, and in all four datasets.

Dr. Haure-Mirande and the team also studied a mouse model lacking the virus-suppressing microRNA-155 molecule and crossed this with one of the most commonly used AD research strains that overexpresses human amyloid precursor protein and develops brain amyloidosis. At 4 months, these mice had larger, more frequent amyloid plaques than the standard amyloidosis mice. Cortical RNA sequencing revealed overlap between upregulated genes in the microRNA-155 knockout mice and the HHV-6a–upregulated genes in human brains.

“These findings support the view of microRNA-155 as a regulator of complex anti- and pro-viral actions, offer a mechanism linking viral activity with AD pathology, and support the hypothesis that viral activity contributes to AD,” the investigators wrote.

As Dr. Gandy said, while not definitive, the studies are tantalizing and lay a solid framework for further investigation. He is confident enough about the association to view HHV as a potential therapeutic target for AD.

“The first step is to find a way to detect the viruses in people. We do have our first antibody to recognize one of the viral proteins, so we’re about to test that on blood serum, blood cells, and spinal fluid, and we will also look for viral DNA in the blood cells. Potentially – way down the road – we might be able to conduct a trial using antivirals,” to see if treatment could slow, or prevent, Alzheimer’s progression.

“These are nice, discrete, testable hypotheses, which makes them attractive,” Dr. Gandy said, “but the truth could be different and is almost certainly a lot messier.”

Dr. Gandy has received research funding from Baxter and Amicus Therapeutics, and personal remuneration from Pfizer and DiaGenic.

SOURCE: Readhead B et al. Neuron. 2018 June 21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.023.

The study by Readhead and colleagues is a scientific tour de force and is likely to elevate the infective hypothesis to a greater height than ever before and deservedly so. Still, the findings are puzzling, at least to this relative virologic novice.

The relationship of infective agents with seemingly degenerative brain diseases has been a complex puzzle that has led to at least two major discoveries. First was the description of a lifeform simpler than viruses, the prion and identification of the human PrP gene that when mutated is the cause of familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which can also be transmitted from human to human (or human to monkey) via tissue transplants.

The data provided by Readhead and colleagues are compelling, however, and unquestionably deserve further attention. Where this will lead is still too early to tell, but given the failure of existing paradigms to translate into meaningful disease-modifying therapies, we have new reason to hope that such a therapy may yet be possible in our lifetime.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

The study by Readhead and colleagues is a scientific tour de force and is likely to elevate the infective hypothesis to a greater height than ever before and deservedly so. Still, the findings are puzzling, at least to this relative virologic novice.

The relationship of infective agents with seemingly degenerative brain diseases has been a complex puzzle that has led to at least two major discoveries. First was the description of a lifeform simpler than viruses, the prion and identification of the human PrP gene that when mutated is the cause of familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which can also be transmitted from human to human (or human to monkey) via tissue transplants.

The data provided by Readhead and colleagues are compelling, however, and unquestionably deserve further attention. Where this will lead is still too early to tell, but given the failure of existing paradigms to translate into meaningful disease-modifying therapies, we have new reason to hope that such a therapy may yet be possible in our lifetime.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

The study by Readhead and colleagues is a scientific tour de force and is likely to elevate the infective hypothesis to a greater height than ever before and deservedly so. Still, the findings are puzzling, at least to this relative virologic novice.

The relationship of infective agents with seemingly degenerative brain diseases has been a complex puzzle that has led to at least two major discoveries. First was the description of a lifeform simpler than viruses, the prion and identification of the human PrP gene that when mutated is the cause of familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which can also be transmitted from human to human (or human to monkey) via tissue transplants.

The data provided by Readhead and colleagues are compelling, however, and unquestionably deserve further attention. Where this will lead is still too early to tell, but given the failure of existing paradigms to translate into meaningful disease-modifying therapies, we have new reason to hope that such a therapy may yet be possible in our lifetime.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Two nearly ubiquitous herpes viruses are abundant in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and appear to integrate themselves into the patient’s own genome, where the viruses play havoc with genes involved in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, among other things, a new study reports.

The genomic analysis of hundreds of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain samples found human herpesvirus 6a and 7 (HHV-6a, HHV-7) in the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus, the initial sites of beta-amyloid overexpression in the disease, first authors Benjamin Readhead, MBBS, Jean-Vianney Haure-Mirande, PhD, and colleagues reported June 21 in Neuron.

The viruses appear to interact with genes implicated in the risk for AD and for regulation and processing of the amyloid precursor protein, including presenilin-1 (PSEN1), BACE1, BIN1, PICALM, and several others. Their presence was directly related to the donors’ Clinical Dementia Rating score, and a mouse model suggests a potential pathway linking HHV infection and brain amyloidosis through a microRNA that’s been previously linked to AD.

It’s impossible to say whether HHV-6a and HHV-7 infections, which occur in nearly 100% of small children, trigger late-life amyloid pathology or whether the viruses reactivate and cross into the brain after amyloid-related damage has already begun, said Keith Fargo, PhD, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. But the data in this paper are strong enough to give real credence, for the first time, to the idea that Alzheimer’s disease may have an infective component.

“This paper, which is quite dense, presents an idea we have seen before, but which has been mostly dismissed,” Dr. Fargo said in an interview. “For the first time, a world-class group of researchers have completed a landmark paper packed with evidence. It’s not definitive evidence yet, but it will certainly bring that hypothesis into the mainstream in a way it has not been before. The Alzheimer’s research world will sit up and take notice.”

The viruses were present in about 20% of AD brain samples taken from four separate brain banks, but not in control samples or in samples from patients with other neurodegenerative diseases. The commonality suggests that the association is real, and something unique to Alzheimer’s, said Sam Gandy, MD, PhD, one of the paper’s senior authors, and a professor of neurology at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

Joel T. Dudley, PhD, director of the Mount Sinai Institute for Next Generation Healthcare, was the other senior author.

“It seems obvious to us that the AD brains around this country are accumulating the genomes of this particular pair of viruses,” Dr. Gandy said in an interview. “For whatever reason, these people were accumulating the genomes of an infectious agent which crossed the blood-brain barrier, went into the brain, and was present there when they were dying of AD. It was not a remote relationship, such as we would see with serology. This was there when they were dying, and it’s hard to imagine it was doing anything good.”

HHV6 causes a primary illness – roseola – when it first enters the body, usually in early childhood. It then enters a life-long latency, but can reactivate in adulthood, according to the HHV-6 Foundation.

“Reactivation can occur in the brain, lungs, heart, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract, especially in patients with immune deficiencies and transplant patients. In some cases, HHV-6 reactivation in the brain tissue can cause cognitive dysfunction, permanent disability, and death.”

The Neuron paper describes several separate investigations that led the team to conclude that HHV-6a and HHV-7 may be implicated in AD pathogenesis.

Dr. Gandy, Dr. Dudley, and their team were not looking for potentially infective agents when they started down this road 5 years ago. Instead, they wanted to see how genes and gene networks change as patients progress from preclinical Alzheimer’s to Alzheimer’s dementia, in the hope of finding novel drug targets.

“This was a surprise result. We were looking for genes differentially expressed as AD progressed. Instead, we found gene expression changes associated with viral infections.”

A transcriptome analysis pointed to microRNA-155, a molecule that helps control viral infections. This lead the team to look for viral RNA in 643 brain samples from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank. “What we found was that HHV-6a and HHV-7 appeared to be driving these changes,” Dr. Gandy said.

HHV-6a interacted with some of the most well-known AD risk genes, Dr. Gandy said.

“The story is full of tantalizing, yet not quite definitive pieces. Presenilin 1 is the most common cause of genetic forms of AD. There are about two dozen genes associated with late-onset sporadic AD. As we scrutinized the computational analysis of the data, whom should we find lurking there among the genes regulated by HHV-6a and HHV-7 but several of our old gene friends from conventional AD genetics and genome-wide association studies: PSEN1, BIN1, PICALM, among others, all of which are linked to causing AD.”

They validated the results from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank in three other data sets: the Religious Orders Study (300 samples from AD patients and healthy controls) the Rush Memory and Aging Project (298 samples from AD patients and healthy controls), and a collection of temporal cortex studies from the Mayo Clinic (278 samples from patients with AD, pathological aging, or progressive supranuclear palsy, and healthy controls).

Again, they saw HHV-6a and HHV-7 in the AD samples, but not in the normal controls or those with pathological aging. Compared with the AD samples, HHV-7 was present in the progressive supranuclear palsy samples, but HHV-6a was reduced.

Whole-exome sequencing found HHV-6a DNA integrated into host DNA. “This may indicate that the HHV-6a DNA that we find as more abundant in AD reflects HHV-6A that has undergone reactivation from a chromosomally integrated form, although we have not evaluated this directly,” Dr. Readhead and his co-investigators wrote in the paper.

Dr. Gandy said that the presence of the two viruses correlated directly with the patients’ Clinical Dementia Rating scale score, neuritic plaque density across multiple regions, and Braak stage, a measure of neurofibrillary tangles.

Another investigation looked at the fractions of the four major brain cells (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells) and their relationship to viral RNA. HHV-6a was associated with decreases in the neuronal content of fractions from multiple brain regions, and in all four datasets.

Dr. Haure-Mirande and the team also studied a mouse model lacking the virus-suppressing microRNA-155 molecule and crossed this with one of the most commonly used AD research strains that overexpresses human amyloid precursor protein and develops brain amyloidosis. At 4 months, these mice had larger, more frequent amyloid plaques than the standard amyloidosis mice. Cortical RNA sequencing revealed overlap between upregulated genes in the microRNA-155 knockout mice and the HHV-6a–upregulated genes in human brains.

“These findings support the view of microRNA-155 as a regulator of complex anti- and pro-viral actions, offer a mechanism linking viral activity with AD pathology, and support the hypothesis that viral activity contributes to AD,” the investigators wrote.

As Dr. Gandy said, while not definitive, the studies are tantalizing and lay a solid framework for further investigation. He is confident enough about the association to view HHV as a potential therapeutic target for AD.

“The first step is to find a way to detect the viruses in people. We do have our first antibody to recognize one of the viral proteins, so we’re about to test that on blood serum, blood cells, and spinal fluid, and we will also look for viral DNA in the blood cells. Potentially – way down the road – we might be able to conduct a trial using antivirals,” to see if treatment could slow, or prevent, Alzheimer’s progression.

“These are nice, discrete, testable hypotheses, which makes them attractive,” Dr. Gandy said, “but the truth could be different and is almost certainly a lot messier.”

Dr. Gandy has received research funding from Baxter and Amicus Therapeutics, and personal remuneration from Pfizer and DiaGenic.

SOURCE: Readhead B et al. Neuron. 2018 June 21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.023.

Two nearly ubiquitous herpes viruses are abundant in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and appear to integrate themselves into the patient’s own genome, where the viruses play havoc with genes involved in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, among other things, a new study reports.

The genomic analysis of hundreds of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain samples found human herpesvirus 6a and 7 (HHV-6a, HHV-7) in the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus, the initial sites of beta-amyloid overexpression in the disease, first authors Benjamin Readhead, MBBS, Jean-Vianney Haure-Mirande, PhD, and colleagues reported June 21 in Neuron.

The viruses appear to interact with genes implicated in the risk for AD and for regulation and processing of the amyloid precursor protein, including presenilin-1 (PSEN1), BACE1, BIN1, PICALM, and several others. Their presence was directly related to the donors’ Clinical Dementia Rating score, and a mouse model suggests a potential pathway linking HHV infection and brain amyloidosis through a microRNA that’s been previously linked to AD.

It’s impossible to say whether HHV-6a and HHV-7 infections, which occur in nearly 100% of small children, trigger late-life amyloid pathology or whether the viruses reactivate and cross into the brain after amyloid-related damage has already begun, said Keith Fargo, PhD, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. But the data in this paper are strong enough to give real credence, for the first time, to the idea that Alzheimer’s disease may have an infective component.

“This paper, which is quite dense, presents an idea we have seen before, but which has been mostly dismissed,” Dr. Fargo said in an interview. “For the first time, a world-class group of researchers have completed a landmark paper packed with evidence. It’s not definitive evidence yet, but it will certainly bring that hypothesis into the mainstream in a way it has not been before. The Alzheimer’s research world will sit up and take notice.”

The viruses were present in about 20% of AD brain samples taken from four separate brain banks, but not in control samples or in samples from patients with other neurodegenerative diseases. The commonality suggests that the association is real, and something unique to Alzheimer’s, said Sam Gandy, MD, PhD, one of the paper’s senior authors, and a professor of neurology at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

Joel T. Dudley, PhD, director of the Mount Sinai Institute for Next Generation Healthcare, was the other senior author.

“It seems obvious to us that the AD brains around this country are accumulating the genomes of this particular pair of viruses,” Dr. Gandy said in an interview. “For whatever reason, these people were accumulating the genomes of an infectious agent which crossed the blood-brain barrier, went into the brain, and was present there when they were dying of AD. It was not a remote relationship, such as we would see with serology. This was there when they were dying, and it’s hard to imagine it was doing anything good.”

HHV6 causes a primary illness – roseola – when it first enters the body, usually in early childhood. It then enters a life-long latency, but can reactivate in adulthood, according to the HHV-6 Foundation.

“Reactivation can occur in the brain, lungs, heart, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract, especially in patients with immune deficiencies and transplant patients. In some cases, HHV-6 reactivation in the brain tissue can cause cognitive dysfunction, permanent disability, and death.”

The Neuron paper describes several separate investigations that led the team to conclude that HHV-6a and HHV-7 may be implicated in AD pathogenesis.

Dr. Gandy, Dr. Dudley, and their team were not looking for potentially infective agents when they started down this road 5 years ago. Instead, they wanted to see how genes and gene networks change as patients progress from preclinical Alzheimer’s to Alzheimer’s dementia, in the hope of finding novel drug targets.

“This was a surprise result. We were looking for genes differentially expressed as AD progressed. Instead, we found gene expression changes associated with viral infections.”

A transcriptome analysis pointed to microRNA-155, a molecule that helps control viral infections. This lead the team to look for viral RNA in 643 brain samples from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank. “What we found was that HHV-6a and HHV-7 appeared to be driving these changes,” Dr. Gandy said.

HHV-6a interacted with some of the most well-known AD risk genes, Dr. Gandy said.

“The story is full of tantalizing, yet not quite definitive pieces. Presenilin 1 is the most common cause of genetic forms of AD. There are about two dozen genes associated with late-onset sporadic AD. As we scrutinized the computational analysis of the data, whom should we find lurking there among the genes regulated by HHV-6a and HHV-7 but several of our old gene friends from conventional AD genetics and genome-wide association studies: PSEN1, BIN1, PICALM, among others, all of which are linked to causing AD.”

They validated the results from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank in three other data sets: the Religious Orders Study (300 samples from AD patients and healthy controls) the Rush Memory and Aging Project (298 samples from AD patients and healthy controls), and a collection of temporal cortex studies from the Mayo Clinic (278 samples from patients with AD, pathological aging, or progressive supranuclear palsy, and healthy controls).

Again, they saw HHV-6a and HHV-7 in the AD samples, but not in the normal controls or those with pathological aging. Compared with the AD samples, HHV-7 was present in the progressive supranuclear palsy samples, but HHV-6a was reduced.

Whole-exome sequencing found HHV-6a DNA integrated into host DNA. “This may indicate that the HHV-6a DNA that we find as more abundant in AD reflects HHV-6A that has undergone reactivation from a chromosomally integrated form, although we have not evaluated this directly,” Dr. Readhead and his co-investigators wrote in the paper.

Dr. Gandy said that the presence of the two viruses correlated directly with the patients’ Clinical Dementia Rating scale score, neuritic plaque density across multiple regions, and Braak stage, a measure of neurofibrillary tangles.

Another investigation looked at the fractions of the four major brain cells (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells) and their relationship to viral RNA. HHV-6a was associated with decreases in the neuronal content of fractions from multiple brain regions, and in all four datasets.

Dr. Haure-Mirande and the team also studied a mouse model lacking the virus-suppressing microRNA-155 molecule and crossed this with one of the most commonly used AD research strains that overexpresses human amyloid precursor protein and develops brain amyloidosis. At 4 months, these mice had larger, more frequent amyloid plaques than the standard amyloidosis mice. Cortical RNA sequencing revealed overlap between upregulated genes in the microRNA-155 knockout mice and the HHV-6a–upregulated genes in human brains.

“These findings support the view of microRNA-155 as a regulator of complex anti- and pro-viral actions, offer a mechanism linking viral activity with AD pathology, and support the hypothesis that viral activity contributes to AD,” the investigators wrote.

As Dr. Gandy said, while not definitive, the studies are tantalizing and lay a solid framework for further investigation. He is confident enough about the association to view HHV as a potential therapeutic target for AD.

“The first step is to find a way to detect the viruses in people. We do have our first antibody to recognize one of the viral proteins, so we’re about to test that on blood serum, blood cells, and spinal fluid, and we will also look for viral DNA in the blood cells. Potentially – way down the road – we might be able to conduct a trial using antivirals,” to see if treatment could slow, or prevent, Alzheimer’s progression.

“These are nice, discrete, testable hypotheses, which makes them attractive,” Dr. Gandy said, “but the truth could be different and is almost certainly a lot messier.”

Dr. Gandy has received research funding from Baxter and Amicus Therapeutics, and personal remuneration from Pfizer and DiaGenic.

SOURCE: Readhead B et al. Neuron. 2018 June 21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.023.

FROM NEURON

NIH cans study that relied on millions in funding from alcohol companies

NIH Francis Collins, MD, said the ethical violations resulted in a fundamentally flawed study that could not proceed.

“NIH has strong policies that detail the standards of conduct for NIH employees, including prohibiting the solicitation of gifts and promoting fairness in grant competitions. We take very seriously any violations of these standards,” Dr. Collins said in a statement, which added that the agency will take appropriate personnel actions.

While testifying before the Senate Appropriations Committee in mid-May on NIH’s budget request for 2019, Dr. Collins vowed not only to appropriately close the Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health (MACH) study, but to investigate whether other potential conflicts exist in other NIH-funded studies.

The story broke in mid-March, when The New York Times reported that scientists and officials from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism who were working on the MACH trial met at informational sessions with five liquor and beer companies in 2013 and 2014. The officials suggested that “the research might reflect favorably on moderate drinking, while institute officials pressed the groups for support,” according to documents obtained by the Times.

In all, the Times reported, the alcohol companies agreed to foot $67 million of the trial’s total $100 million bill. Such action violates NIH policy. An NIH report named those companies as Anheuser-Busch InBev, Carlsberg Breweries A/S, Diageo plc, Heineken, and Pernod Ricard USA LLC.

The MACH study was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial to determine the effects of one serving of alcohol (approximately 15 grams) daily, compared to no alcohol intake, on the rate of new cases of cardiovascular disease and the rate of new cases of diabetes among participants free of diabetes at baseline.

“The study was launched because some epidemiological studies have shown that moderate alcohol consumption has health benefits by reducing risk for coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis,” according to the NIH statement. “The study aimed to enroll 7,800 participants. After a planning phase, it began enrollment on Feb. 5, 2018, and was suspended on May 10, 2018, at which time there were 105 participants enrolled.”

The trial was being led by researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

In response to the public disclosure of the study’s funding, NIH convened a working group to ascertain:

- the circumstances that led to securing private funding for MACH trial

- the scientific premise of and planning for the MACH trial

- the process used to decide to support the MACH trial

- program development and oversight once funding was secured by the secured by the Foundation for NIH (FNIH)

- a review of the NIAAA portfolio prior to and during the leadership of the current NIAAA Director to assess what programmatic shifts, if any, could be discerned.

While noting that public-private partnerships are key to advancing science, the committee found that soliciting funds from alcoholic beverage companies for a study that could prove such beverages are beneficial, crossed the “firewall” between public funds and private resources. The committee recommended terminating the study.

The committee also recommended an expanded investigation into measures that would prevent NIH staff from soliciting external funds to support research programs.

The committee uncovered an email trail strongly suggesting that the solicitation of funds was planned and intended to be secretive.

According to the working group report, there was “frequent email correspondence among members of NIAAA senior staff, select extramural investigators (including the eventual PI of the MACH trial), and industry representatives occurred prior to involvement of the FNIH and the development of the NIH funding opportunity announcement for a multi-site clinical trial on moderate drinking and cardiovascular health. These communications appear to be an attempt to persuade industry to provide funding for the MACH trial. Moreover, these senior members of NIAAA staff appear to have purposefully kept other key members of NIAAA staff and the FNIH ignorant of these efforts. For example, correspondence between NIAAA staff draws attention to a February 2014 wine industry blog that reports that FNIH is initiating a search for industry funding to support a major clinical study on the health effects of moderate alcohol consumption. One senior staff member at NIAAA is unaware of any such potential planning, asking another senior staff member about the article. ‘... Anything seem broken here?’ even though such a trial to test moderate drinking effects on cardiovascular health should very likely involve the programmatic division to which this senior staff member belongs. In response to receiving the forwarded discussion, NIAAA senior leadership communicates among one other, ‘Best not to respond right now but we can’t keep him totally in the dark.’ "

The trial was also funded in part by NIAAA, which expected to commit $20 million to the overall project over 10 years, of which $4 million has been spent.

“The integrity of the NIH grants administrative process, peer review, and the quality of NIH-supported research must always be above reproach,” Dr. Collins said in the statement. “When any problems are uncovered, however, efforts to correct them must be swift and comprehensive.”

NIH Francis Collins, MD, said the ethical violations resulted in a fundamentally flawed study that could not proceed.

“NIH has strong policies that detail the standards of conduct for NIH employees, including prohibiting the solicitation of gifts and promoting fairness in grant competitions. We take very seriously any violations of these standards,” Dr. Collins said in a statement, which added that the agency will take appropriate personnel actions.

While testifying before the Senate Appropriations Committee in mid-May on NIH’s budget request for 2019, Dr. Collins vowed not only to appropriately close the Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health (MACH) study, but to investigate whether other potential conflicts exist in other NIH-funded studies.

The story broke in mid-March, when The New York Times reported that scientists and officials from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism who were working on the MACH trial met at informational sessions with five liquor and beer companies in 2013 and 2014. The officials suggested that “the research might reflect favorably on moderate drinking, while institute officials pressed the groups for support,” according to documents obtained by the Times.

In all, the Times reported, the alcohol companies agreed to foot $67 million of the trial’s total $100 million bill. Such action violates NIH policy. An NIH report named those companies as Anheuser-Busch InBev, Carlsberg Breweries A/S, Diageo plc, Heineken, and Pernod Ricard USA LLC.

The MACH study was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial to determine the effects of one serving of alcohol (approximately 15 grams) daily, compared to no alcohol intake, on the rate of new cases of cardiovascular disease and the rate of new cases of diabetes among participants free of diabetes at baseline.

“The study was launched because some epidemiological studies have shown that moderate alcohol consumption has health benefits by reducing risk for coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis,” according to the NIH statement. “The study aimed to enroll 7,800 participants. After a planning phase, it began enrollment on Feb. 5, 2018, and was suspended on May 10, 2018, at which time there were 105 participants enrolled.”

The trial was being led by researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

In response to the public disclosure of the study’s funding, NIH convened a working group to ascertain:

- the circumstances that led to securing private funding for MACH trial

- the scientific premise of and planning for the MACH trial

- the process used to decide to support the MACH trial

- program development and oversight once funding was secured by the secured by the Foundation for NIH (FNIH)

- a review of the NIAAA portfolio prior to and during the leadership of the current NIAAA Director to assess what programmatic shifts, if any, could be discerned.

While noting that public-private partnerships are key to advancing science, the committee found that soliciting funds from alcoholic beverage companies for a study that could prove such beverages are beneficial, crossed the “firewall” between public funds and private resources. The committee recommended terminating the study.

The committee also recommended an expanded investigation into measures that would prevent NIH staff from soliciting external funds to support research programs.

The committee uncovered an email trail strongly suggesting that the solicitation of funds was planned and intended to be secretive.

According to the working group report, there was “frequent email correspondence among members of NIAAA senior staff, select extramural investigators (including the eventual PI of the MACH trial), and industry representatives occurred prior to involvement of the FNIH and the development of the NIH funding opportunity announcement for a multi-site clinical trial on moderate drinking and cardiovascular health. These communications appear to be an attempt to persuade industry to provide funding for the MACH trial. Moreover, these senior members of NIAAA staff appear to have purposefully kept other key members of NIAAA staff and the FNIH ignorant of these efforts. For example, correspondence between NIAAA staff draws attention to a February 2014 wine industry blog that reports that FNIH is initiating a search for industry funding to support a major clinical study on the health effects of moderate alcohol consumption. One senior staff member at NIAAA is unaware of any such potential planning, asking another senior staff member about the article. ‘... Anything seem broken here?’ even though such a trial to test moderate drinking effects on cardiovascular health should very likely involve the programmatic division to which this senior staff member belongs. In response to receiving the forwarded discussion, NIAAA senior leadership communicates among one other, ‘Best not to respond right now but we can’t keep him totally in the dark.’ "

The trial was also funded in part by NIAAA, which expected to commit $20 million to the overall project over 10 years, of which $4 million has been spent.

“The integrity of the NIH grants administrative process, peer review, and the quality of NIH-supported research must always be above reproach,” Dr. Collins said in the statement. “When any problems are uncovered, however, efforts to correct them must be swift and comprehensive.”

NIH Francis Collins, MD, said the ethical violations resulted in a fundamentally flawed study that could not proceed.

“NIH has strong policies that detail the standards of conduct for NIH employees, including prohibiting the solicitation of gifts and promoting fairness in grant competitions. We take very seriously any violations of these standards,” Dr. Collins said in a statement, which added that the agency will take appropriate personnel actions.

While testifying before the Senate Appropriations Committee in mid-May on NIH’s budget request for 2019, Dr. Collins vowed not only to appropriately close the Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health (MACH) study, but to investigate whether other potential conflicts exist in other NIH-funded studies.

The story broke in mid-March, when The New York Times reported that scientists and officials from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism who were working on the MACH trial met at informational sessions with five liquor and beer companies in 2013 and 2014. The officials suggested that “the research might reflect favorably on moderate drinking, while institute officials pressed the groups for support,” according to documents obtained by the Times.

In all, the Times reported, the alcohol companies agreed to foot $67 million of the trial’s total $100 million bill. Such action violates NIH policy. An NIH report named those companies as Anheuser-Busch InBev, Carlsberg Breweries A/S, Diageo plc, Heineken, and Pernod Ricard USA LLC.

The MACH study was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial to determine the effects of one serving of alcohol (approximately 15 grams) daily, compared to no alcohol intake, on the rate of new cases of cardiovascular disease and the rate of new cases of diabetes among participants free of diabetes at baseline.

“The study was launched because some epidemiological studies have shown that moderate alcohol consumption has health benefits by reducing risk for coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis,” according to the NIH statement. “The study aimed to enroll 7,800 participants. After a planning phase, it began enrollment on Feb. 5, 2018, and was suspended on May 10, 2018, at which time there were 105 participants enrolled.”

The trial was being led by researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

In response to the public disclosure of the study’s funding, NIH convened a working group to ascertain:

- the circumstances that led to securing private funding for MACH trial

- the scientific premise of and planning for the MACH trial

- the process used to decide to support the MACH trial

- program development and oversight once funding was secured by the secured by the Foundation for NIH (FNIH)

- a review of the NIAAA portfolio prior to and during the leadership of the current NIAAA Director to assess what programmatic shifts, if any, could be discerned.

While noting that public-private partnerships are key to advancing science, the committee found that soliciting funds from alcoholic beverage companies for a study that could prove such beverages are beneficial, crossed the “firewall” between public funds and private resources. The committee recommended terminating the study.

The committee also recommended an expanded investigation into measures that would prevent NIH staff from soliciting external funds to support research programs.

The committee uncovered an email trail strongly suggesting that the solicitation of funds was planned and intended to be secretive.

According to the working group report, there was “frequent email correspondence among members of NIAAA senior staff, select extramural investigators (including the eventual PI of the MACH trial), and industry representatives occurred prior to involvement of the FNIH and the development of the NIH funding opportunity announcement for a multi-site clinical trial on moderate drinking and cardiovascular health. These communications appear to be an attempt to persuade industry to provide funding for the MACH trial. Moreover, these senior members of NIAAA staff appear to have purposefully kept other key members of NIAAA staff and the FNIH ignorant of these efforts. For example, correspondence between NIAAA staff draws attention to a February 2014 wine industry blog that reports that FNIH is initiating a search for industry funding to support a major clinical study on the health effects of moderate alcohol consumption. One senior staff member at NIAAA is unaware of any such potential planning, asking another senior staff member about the article. ‘... Anything seem broken here?’ even though such a trial to test moderate drinking effects on cardiovascular health should very likely involve the programmatic division to which this senior staff member belongs. In response to receiving the forwarded discussion, NIAAA senior leadership communicates among one other, ‘Best not to respond right now but we can’t keep him totally in the dark.’ "

The trial was also funded in part by NIAAA, which expected to commit $20 million to the overall project over 10 years, of which $4 million has been spent.

“The integrity of the NIH grants administrative process, peer review, and the quality of NIH-supported research must always be above reproach,” Dr. Collins said in the statement. “When any problems are uncovered, however, efforts to correct them must be swift and comprehensive.”

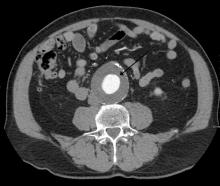

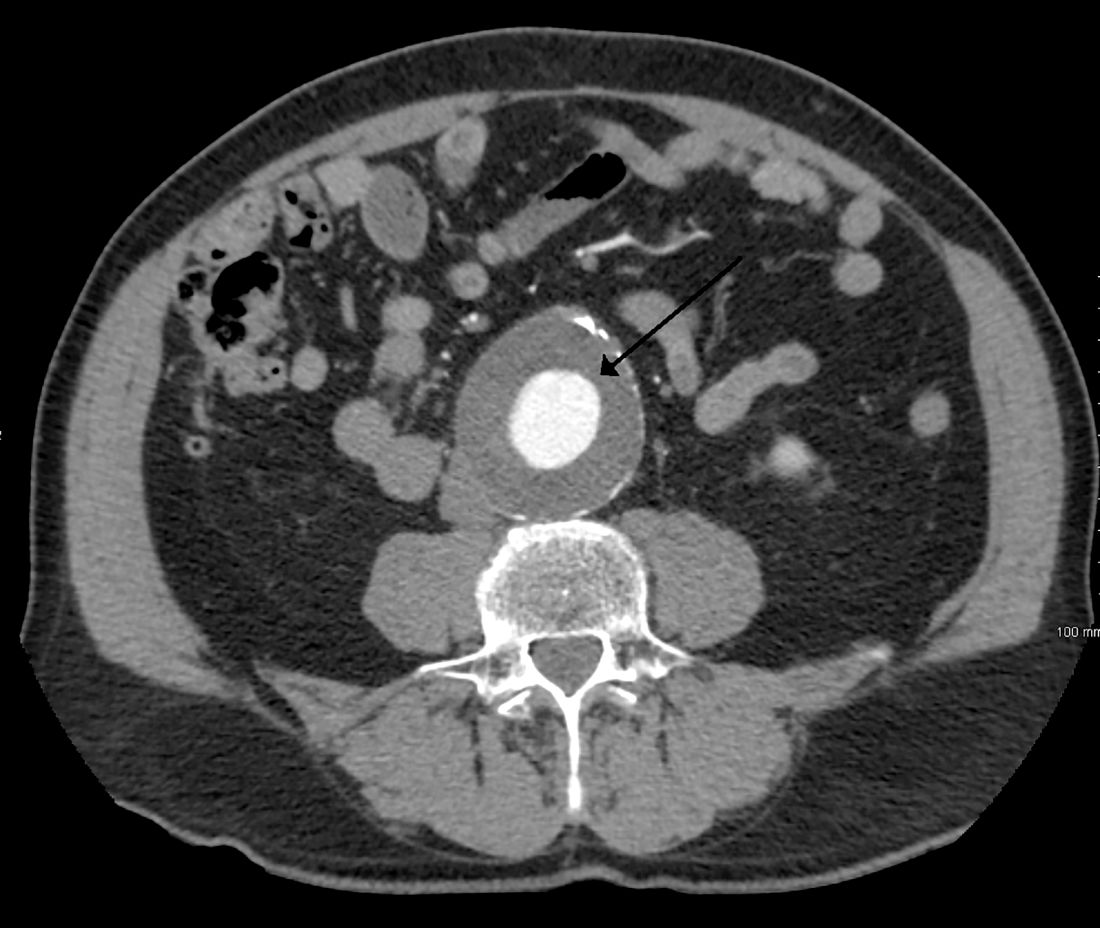

Routine screening for AAA in older men may harm more than help

Deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm among Swedish men are going down – but not because they’re being screened for the potentially fatal condition.

Although the death rate has decreased by 70% since the early 2000s, screening only saved 2 lives per 10,000 men screened. It did, however, increase by 59% the risk of unnecessary surgery, Minna Johansson, MD, and colleagues wrote in the June 16 issue of the Lancet.

“Screening had only a minor effect on AAA mortality,” wrote Dr. Johansson of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). “In absolute numbers, only 7% of the benefit estimated in the largest trial of AAA screening was observed. The observed large reductions in AAA mortality were present in both the screened and nonscreened cohorts and were thus mainly caused by other factors – probably reduced smoking. … Our results call the continued justification of AAA screening into question.”

In Sweden, all men aged 65 years are invited to a one-time ultrasound abdominal aorta screening. Most participate. Anyone with an aneurysm is followed up at a vascular surgery clinic, with surgery considered if the aortic diameter is 55 mm or larger.

Dr. Johansson and her colleagues plumbed national health records to estimate the risks and benefits of this routine screening. The study comprised 25,265 men invited to join the AAA screening program in Sweden from 2006 to 2009. Mortality data were compared with those from a contemporaneous cohort of 106,087 men of similar age who were not invited to screen. Finally, the mortality data were compared with national trends in AAA mortality in all Swedish men aged 40-99 years from 1987 to 2015.

A multivariate analysis adjusted for cohort year, marital status, educational level, income, and whether the patient already had an AAA diagnosis at baseline.

From the early 2000s to 2015, AAA mortality among men aged 65-74 years declined from 36 to10 deaths per 100,000. This 70% reduction was similar in both screened and unscreened populations; in fact, the decline began about a decade before population-based screening was introduced and continued to decrease at a steady rate afterward.

After 6 years of screening, there was a 30% reduction of AAA mortality in the screened population, compared with the unscreened, translating to an absolute mortality reduction of two deaths per 10,000 men offered screening.

Screening increased by 52% the number of AAAs detected. The absolute difference in incidence after 6 years of screening translated to an additional 49 overdiagnoses per 10,000 screened men.

Looking back into the mid-1990s, the investigators saw the numbers of elective AAA surgeries rise steadily. In the adjusted model, screened men were 59% more likely to have this procedure than unscreened. The increased risk didn’t come with an equally increased benefit, though. There was a 10% decrease in AAA ruptures, “rendering a risk of overtreatment of 19%, or 19 potentially avoidable elective surgeries per 10,000 men,” the team noted. “Sixty-three percent of all additional elective surgeries for AAA might therefore have constituted overtreat.”

The findings are at odds with large published studies that found a consistent benefit to screening.

“Compared with results at 7-year follow-up of the largest trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm [Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS)], we found about half of the benefit in terms of a relative effect and 7% of the estimated benefit in terms of absolute numbers [2 vs. 27 avoided deaths from AAA per 10,000 invited men]. Compared with previous estimates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, we found a lower absolute number of over-diagnosed cases [49 vs.176 per 10,000 invited men] and fewer overtreated cases [19 vs. 37 per 10,000 invited men]. However, since the harms of screening decreased less than the benefit, the balance between benefits and harms seems much less appealing in today’s setting.”

None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

The study by Johansson et al. indicates a significant risk of overdiagnosis associated with routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Those risks may not be as clinically harmful as might be assumed, Stefan Acosta, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018; 391: 2394-95).

“Although I agree that having a small AAA that needs long-term follow-up might be associated with negative psychological consequences, there could also be a window of opportunity [eg. with statins, antiplatelet therapy, and blood pressure reduction], for individuals with increased burden of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, screening for AAA, peripheral artery disease, and hypertension, with the initiation of relevant pharmacotherapy, if positive, reduces all-cause mortality and some evidence suggests that this approach of multifaceted vascular screening instead of isolated AAA screening should be considered.”

When performed according to the established criteria for elective AAA surgery, the procedure is associated with less than 1% postoperative mortality, “mainly because of wide implementation of endovascular aneurysm repair, a minimally invasive method.”

The 6-year follow-up time, as the authors noted, is relatively short. A 2016 review of the Swedish Nationwide Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Program determined that significant mortality benefit could take 10 years to materialize(Circ 2016;134:1141-8).

The full impact of Sweden’s remarkable decrease in smoking is almost certainly making itself known in these outcomes – smoking is implicated in 75% of AAA cases.

“The decreased prevalence of smoking in Sweden, from 44% of the population in 1970 to 15% in 2010, should be viewed as the main cause of the decreasing incidence and mortality of AAA. Every percent drop in the prevalence of smoking will have a huge effect on smoking-related diseases, such as cancer and AAA.”

Dr. Stefan is a vascular disease researcher at Lund (Sweden) University. He had no financial disclosures.

The study by Johansson et al. indicates a significant risk of overdiagnosis associated with routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Those risks may not be as clinically harmful as might be assumed, Stefan Acosta, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018; 391: 2394-95).

“Although I agree that having a small AAA that needs long-term follow-up might be associated with negative psychological consequences, there could also be a window of opportunity [eg. with statins, antiplatelet therapy, and blood pressure reduction], for individuals with increased burden of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, screening for AAA, peripheral artery disease, and hypertension, with the initiation of relevant pharmacotherapy, if positive, reduces all-cause mortality and some evidence suggests that this approach of multifaceted vascular screening instead of isolated AAA screening should be considered.”

When performed according to the established criteria for elective AAA surgery, the procedure is associated with less than 1% postoperative mortality, “mainly because of wide implementation of endovascular aneurysm repair, a minimally invasive method.”

The 6-year follow-up time, as the authors noted, is relatively short. A 2016 review of the Swedish Nationwide Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Program determined that significant mortality benefit could take 10 years to materialize(Circ 2016;134:1141-8).

The full impact of Sweden’s remarkable decrease in smoking is almost certainly making itself known in these outcomes – smoking is implicated in 75% of AAA cases.

“The decreased prevalence of smoking in Sweden, from 44% of the population in 1970 to 15% in 2010, should be viewed as the main cause of the decreasing incidence and mortality of AAA. Every percent drop in the prevalence of smoking will have a huge effect on smoking-related diseases, such as cancer and AAA.”

Dr. Stefan is a vascular disease researcher at Lund (Sweden) University. He had no financial disclosures.

The study by Johansson et al. indicates a significant risk of overdiagnosis associated with routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Those risks may not be as clinically harmful as might be assumed, Stefan Acosta, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018; 391: 2394-95).

“Although I agree that having a small AAA that needs long-term follow-up might be associated with negative psychological consequences, there could also be a window of opportunity [eg. with statins, antiplatelet therapy, and blood pressure reduction], for individuals with increased burden of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, screening for AAA, peripheral artery disease, and hypertension, with the initiation of relevant pharmacotherapy, if positive, reduces all-cause mortality and some evidence suggests that this approach of multifaceted vascular screening instead of isolated AAA screening should be considered.”

When performed according to the established criteria for elective AAA surgery, the procedure is associated with less than 1% postoperative mortality, “mainly because of wide implementation of endovascular aneurysm repair, a minimally invasive method.”

The 6-year follow-up time, as the authors noted, is relatively short. A 2016 review of the Swedish Nationwide Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Program determined that significant mortality benefit could take 10 years to materialize(Circ 2016;134:1141-8).

The full impact of Sweden’s remarkable decrease in smoking is almost certainly making itself known in these outcomes – smoking is implicated in 75% of AAA cases.

“The decreased prevalence of smoking in Sweden, from 44% of the population in 1970 to 15% in 2010, should be viewed as the main cause of the decreasing incidence and mortality of AAA. Every percent drop in the prevalence of smoking will have a huge effect on smoking-related diseases, such as cancer and AAA.”

Dr. Stefan is a vascular disease researcher at Lund (Sweden) University. He had no financial disclosures.

Deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm among Swedish men are going down – but not because they’re being screened for the potentially fatal condition.

Although the death rate has decreased by 70% since the early 2000s, screening only saved 2 lives per 10,000 men screened. It did, however, increase by 59% the risk of unnecessary surgery, Minna Johansson, MD, and colleagues wrote in the June 16 issue of the Lancet.

“Screening had only a minor effect on AAA mortality,” wrote Dr. Johansson of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). “In absolute numbers, only 7% of the benefit estimated in the largest trial of AAA screening was observed. The observed large reductions in AAA mortality were present in both the screened and nonscreened cohorts and were thus mainly caused by other factors – probably reduced smoking. … Our results call the continued justification of AAA screening into question.”

In Sweden, all men aged 65 years are invited to a one-time ultrasound abdominal aorta screening. Most participate. Anyone with an aneurysm is followed up at a vascular surgery clinic, with surgery considered if the aortic diameter is 55 mm or larger.

Dr. Johansson and her colleagues plumbed national health records to estimate the risks and benefits of this routine screening. The study comprised 25,265 men invited to join the AAA screening program in Sweden from 2006 to 2009. Mortality data were compared with those from a contemporaneous cohort of 106,087 men of similar age who were not invited to screen. Finally, the mortality data were compared with national trends in AAA mortality in all Swedish men aged 40-99 years from 1987 to 2015.

A multivariate analysis adjusted for cohort year, marital status, educational level, income, and whether the patient already had an AAA diagnosis at baseline.

From the early 2000s to 2015, AAA mortality among men aged 65-74 years declined from 36 to10 deaths per 100,000. This 70% reduction was similar in both screened and unscreened populations; in fact, the decline began about a decade before population-based screening was introduced and continued to decrease at a steady rate afterward.

After 6 years of screening, there was a 30% reduction of AAA mortality in the screened population, compared with the unscreened, translating to an absolute mortality reduction of two deaths per 10,000 men offered screening.

Screening increased by 52% the number of AAAs detected. The absolute difference in incidence after 6 years of screening translated to an additional 49 overdiagnoses per 10,000 screened men.

Looking back into the mid-1990s, the investigators saw the numbers of elective AAA surgeries rise steadily. In the adjusted model, screened men were 59% more likely to have this procedure than unscreened. The increased risk didn’t come with an equally increased benefit, though. There was a 10% decrease in AAA ruptures, “rendering a risk of overtreatment of 19%, or 19 potentially avoidable elective surgeries per 10,000 men,” the team noted. “Sixty-three percent of all additional elective surgeries for AAA might therefore have constituted overtreat.”

The findings are at odds with large published studies that found a consistent benefit to screening.

“Compared with results at 7-year follow-up of the largest trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm [Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS)], we found about half of the benefit in terms of a relative effect and 7% of the estimated benefit in terms of absolute numbers [2 vs. 27 avoided deaths from AAA per 10,000 invited men]. Compared with previous estimates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, we found a lower absolute number of over-diagnosed cases [49 vs.176 per 10,000 invited men] and fewer overtreated cases [19 vs. 37 per 10,000 invited men]. However, since the harms of screening decreased less than the benefit, the balance between benefits and harms seems much less appealing in today’s setting.”

None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

Deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm among Swedish men are going down – but not because they’re being screened for the potentially fatal condition.