User login

Implementation of a Patient Medication Disposal Program at a VA Medical Center

Opioid overdoses have quadrupled since 1999, with 78 Americans dying every day of opioid overdoses. More than half of all opioid overdose deaths involve prescription opioids.1 Attacking this problem from both ends—prescribing and disposal—can have a greater impact than focusing on a single strategy.

Background

In 2016, the CDC issued opioid prescription guidelines that included encouraging health care providers to discuss “options for safe disposal of unused opioids.”2 Pharmacies are prohibited from directly taking possession of controlled substances from a user. Historically, the Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) in Indianapolis, Indiana, recommended that patients follow FDA guidance for household medication disposal, which includes a list of medications that should be flushed down the toilet.3 As more data became available about the negative downstream environmental effects of pharmaceuticals on the water supply, this method of destruction made many patients feel uncomfortable.4,5

The Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 presented additional options for hospitals and pharmacies to assist the public with medication disposal.6,7 These options offer convenience and anonymity for the end user, reduce potential for diversion, and enhance patient safety by ridding homes of unwanted and expired medications.

Prior to the 2010 act, the only legal methods of controlled substance disposal were via trash disposal, flushing, or delivery to law enforcement, typically at a community-based drug take-back event. These methods were not always convenient, environmentally friendly, or safe for other family members and pets in the home. The Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 added 2 additional collection options for pharmacies: collection receptacles and mail-back programs.

The RLRVAMC treats > 62,000 veterans annually. The RLRVAMC Pharmacy Service had been providing pharmaceutical mail-back envelopes to patients since May 2015 with moderate success (271 lb of medications returned and a 22.8% envelope return rate through September 2016). Although the mail-back envelopes offer at-home convenience, there was no on-site disposal option. It is not uncommon for patients to bring medications to their appointment or the emergency department (ED). When medication reconciliation is performed, some medications are discontinued, and the prescriber wants them to be safely out of the patient’s possession to avoid confusion and/or accidental overdose. The purpose of this project was to offer more disposal options to patients through the addition of an on-site medication collection receptacle that would be in compliance with U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) regulations.

Methods

A policy was developed between the RLRVAMC pharmacy and police departments for the management of a medication collection receptacle. Police would oversee the disposal program so that the pharmacy would not have to change its DEA registration to collector status. The 2 access keys to the receptacle were maintained by police and secured within a key accountability system in the police station.

Full liners are removed from the receptacle by 2 police officers and sealed securely according to vendor guidelines. In accordance with DEA regulations, a form is completed that documents the dates the inner liner was acquired, installed, removed, and transferred for destruction as well as the unique identification number and size of the liner, the address of the location where it was installed, and the names and signatures of the 2 employees that witnessed the removal.

Arrangements are made to have a mail courier present during the removal of the liner. Once removed, the liner is immediately sealed and released to the mail courier who transports the liner to the DEA authorized reverse distributor. The reverse distributor is a licensed entity that has the authority to take control of the medications, including controlled substances, for disposal. The liner tracking numbers are kept in a police log book so that delivery can be confirmed and destruction certificates obtained from the vendor’s website at a later date. The records are kept for 3 years.

Funding was obtained for a 38-gallon collection receptacle and 12 liners from Pharmacy Benefits Management Services (PBM). Approval was obtained from RLRVAMC leadership to locate the receptacle in a high-traffic area, anchored to the floor, under video surveillance, and away from the ED entrance (a DEA requirement). Public Affairs promoted the receptacle to veterans. E-mails were sent to staff to provide education on regulatory requirements. Weight and frequency of medications returned were obtained from data collected by the reverse distributor. Descriptive statistics are reported.

Results

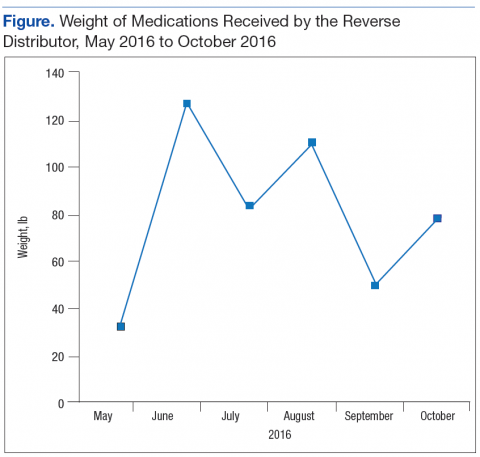

The Federal Supply Schedule cost to procure a DEA-compliant receptacle was $1,450. The additional 12 inner liners cost $2,024.97.8 Staff from Engineering Service were able to install the receptacle at no additional cost to the facility. The collection receptacle was opened to the public in May 2016. From May through October 2016, the facility collected and returned 10 liners to the reverse distributor containing 452 lb of medications. An additional 30 lb of drugs were returned through the mailback envelope program for a total weight of 482 lb over the 6-month period (Figure). The average time between inner liner changes was 2.6 weeks.

Discussion

The most challenging aspect of implementation was identification of a location for the receptacle. The location chosen, an alcove in the hallway between the coffee shop and outpatient pharmacy, was most appropriate. It is a high-traffic area, under video surveillance, and provides easy access for patients. Another challenge was determining the frequency of liner changes. There was no historic data to assist with predicting how quickly the liner would fill up. Initially, Police Service checked the receptacle every week, and it was emptied about every 2 weeks. Aspatients cleaned out their medicine cabinets, the liner needed to be replaced closer to every 4 weeks. An ongoing challenge has been determining how full the liner is without requiring the police to open the receptacle. Consideration is being given to installing a scale in the receptacle under the liner and having the display affixed to the outside of the container.

The receptacle seemed to be the preferred method of disposal, considering that it generated nearly 15 times more waste than did the mail-back envelopes during the same time period. Anecdotal patient feedback has been extremely positive on social media and by word-of-mouth.

Limitations

One limitation of this disposal program is that the specific amount of controlled substance waste vs noncontrolled substance waste cannot be determined since the liner contents are not inventoried. The University of Findlay in Ohio partnered with local law enforcement to host 7 community medication take-back events over a 3-year period, inventoried the drugs, and found that about one-third of the dosing units (eg, tablet or capsule) returned in the analgesic category were controlled substances, suggesting that take-back events may play a role in reducing unauthorized access to prescription painkillers.9 By witnessing the changing of inner liners, it can be anecdotally confirmed that a significant amount of controlled substances were collected and returned at RLRVAMC. These results have been shared with respective VISN leadership, and additional facilities are installing receptacles.

Conclusion

Changes to DEA regulations offer medical centers more options for developing a comprehensive drug disposal program. Implementation of a pharmaceutical take-back program can assist patients with disposal of unwanted and expired medications, promote safety and environmental stewardship, and reduce the risk of diversion.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html. Updated April 16, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49.

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Disposal of unused medicines: what you should know. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htm#Flush_List. Updated April 21, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2017.

4. Li WC. Occurrence, sources, and fate of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environment and soil. Environ Pollut. 2014;187:193-201.

5. Boxall AB. The environmental side effects of medication. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(12):1110-1116.

6. Peterson DM. New DEA rules expand options for controlled substance disposal. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(1):22-26.

7. U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug disposal information. https:// www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/index.html. Accessed June 5, 2016.

8. GSA Advantage! Online shopping. https://www.gsaadvantage.gov. Accessed June 5, 2017.

9. Perry LA, Shinn BW, Stanovich J. Quantification of an ongoing community-based medication take-back program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2014;54(3):275-279.

Opioid overdoses have quadrupled since 1999, with 78 Americans dying every day of opioid overdoses. More than half of all opioid overdose deaths involve prescription opioids.1 Attacking this problem from both ends—prescribing and disposal—can have a greater impact than focusing on a single strategy.

Background

In 2016, the CDC issued opioid prescription guidelines that included encouraging health care providers to discuss “options for safe disposal of unused opioids.”2 Pharmacies are prohibited from directly taking possession of controlled substances from a user. Historically, the Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) in Indianapolis, Indiana, recommended that patients follow FDA guidance for household medication disposal, which includes a list of medications that should be flushed down the toilet.3 As more data became available about the negative downstream environmental effects of pharmaceuticals on the water supply, this method of destruction made many patients feel uncomfortable.4,5

The Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 presented additional options for hospitals and pharmacies to assist the public with medication disposal.6,7 These options offer convenience and anonymity for the end user, reduce potential for diversion, and enhance patient safety by ridding homes of unwanted and expired medications.

Prior to the 2010 act, the only legal methods of controlled substance disposal were via trash disposal, flushing, or delivery to law enforcement, typically at a community-based drug take-back event. These methods were not always convenient, environmentally friendly, or safe for other family members and pets in the home. The Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 added 2 additional collection options for pharmacies: collection receptacles and mail-back programs.

The RLRVAMC treats > 62,000 veterans annually. The RLRVAMC Pharmacy Service had been providing pharmaceutical mail-back envelopes to patients since May 2015 with moderate success (271 lb of medications returned and a 22.8% envelope return rate through September 2016). Although the mail-back envelopes offer at-home convenience, there was no on-site disposal option. It is not uncommon for patients to bring medications to their appointment or the emergency department (ED). When medication reconciliation is performed, some medications are discontinued, and the prescriber wants them to be safely out of the patient’s possession to avoid confusion and/or accidental overdose. The purpose of this project was to offer more disposal options to patients through the addition of an on-site medication collection receptacle that would be in compliance with U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) regulations.

Methods

A policy was developed between the RLRVAMC pharmacy and police departments for the management of a medication collection receptacle. Police would oversee the disposal program so that the pharmacy would not have to change its DEA registration to collector status. The 2 access keys to the receptacle were maintained by police and secured within a key accountability system in the police station.

Full liners are removed from the receptacle by 2 police officers and sealed securely according to vendor guidelines. In accordance with DEA regulations, a form is completed that documents the dates the inner liner was acquired, installed, removed, and transferred for destruction as well as the unique identification number and size of the liner, the address of the location where it was installed, and the names and signatures of the 2 employees that witnessed the removal.

Arrangements are made to have a mail courier present during the removal of the liner. Once removed, the liner is immediately sealed and released to the mail courier who transports the liner to the DEA authorized reverse distributor. The reverse distributor is a licensed entity that has the authority to take control of the medications, including controlled substances, for disposal. The liner tracking numbers are kept in a police log book so that delivery can be confirmed and destruction certificates obtained from the vendor’s website at a later date. The records are kept for 3 years.

Funding was obtained for a 38-gallon collection receptacle and 12 liners from Pharmacy Benefits Management Services (PBM). Approval was obtained from RLRVAMC leadership to locate the receptacle in a high-traffic area, anchored to the floor, under video surveillance, and away from the ED entrance (a DEA requirement). Public Affairs promoted the receptacle to veterans. E-mails were sent to staff to provide education on regulatory requirements. Weight and frequency of medications returned were obtained from data collected by the reverse distributor. Descriptive statistics are reported.

Results

The Federal Supply Schedule cost to procure a DEA-compliant receptacle was $1,450. The additional 12 inner liners cost $2,024.97.8 Staff from Engineering Service were able to install the receptacle at no additional cost to the facility. The collection receptacle was opened to the public in May 2016. From May through October 2016, the facility collected and returned 10 liners to the reverse distributor containing 452 lb of medications. An additional 30 lb of drugs were returned through the mailback envelope program for a total weight of 482 lb over the 6-month period (Figure). The average time between inner liner changes was 2.6 weeks.

Discussion

The most challenging aspect of implementation was identification of a location for the receptacle. The location chosen, an alcove in the hallway between the coffee shop and outpatient pharmacy, was most appropriate. It is a high-traffic area, under video surveillance, and provides easy access for patients. Another challenge was determining the frequency of liner changes. There was no historic data to assist with predicting how quickly the liner would fill up. Initially, Police Service checked the receptacle every week, and it was emptied about every 2 weeks. Aspatients cleaned out their medicine cabinets, the liner needed to be replaced closer to every 4 weeks. An ongoing challenge has been determining how full the liner is without requiring the police to open the receptacle. Consideration is being given to installing a scale in the receptacle under the liner and having the display affixed to the outside of the container.

The receptacle seemed to be the preferred method of disposal, considering that it generated nearly 15 times more waste than did the mail-back envelopes during the same time period. Anecdotal patient feedback has been extremely positive on social media and by word-of-mouth.

Limitations

One limitation of this disposal program is that the specific amount of controlled substance waste vs noncontrolled substance waste cannot be determined since the liner contents are not inventoried. The University of Findlay in Ohio partnered with local law enforcement to host 7 community medication take-back events over a 3-year period, inventoried the drugs, and found that about one-third of the dosing units (eg, tablet or capsule) returned in the analgesic category were controlled substances, suggesting that take-back events may play a role in reducing unauthorized access to prescription painkillers.9 By witnessing the changing of inner liners, it can be anecdotally confirmed that a significant amount of controlled substances were collected and returned at RLRVAMC. These results have been shared with respective VISN leadership, and additional facilities are installing receptacles.

Conclusion

Changes to DEA regulations offer medical centers more options for developing a comprehensive drug disposal program. Implementation of a pharmaceutical take-back program can assist patients with disposal of unwanted and expired medications, promote safety and environmental stewardship, and reduce the risk of diversion.

Opioid overdoses have quadrupled since 1999, with 78 Americans dying every day of opioid overdoses. More than half of all opioid overdose deaths involve prescription opioids.1 Attacking this problem from both ends—prescribing and disposal—can have a greater impact than focusing on a single strategy.

Background

In 2016, the CDC issued opioid prescription guidelines that included encouraging health care providers to discuss “options for safe disposal of unused opioids.”2 Pharmacies are prohibited from directly taking possession of controlled substances from a user. Historically, the Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) in Indianapolis, Indiana, recommended that patients follow FDA guidance for household medication disposal, which includes a list of medications that should be flushed down the toilet.3 As more data became available about the negative downstream environmental effects of pharmaceuticals on the water supply, this method of destruction made many patients feel uncomfortable.4,5

The Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 presented additional options for hospitals and pharmacies to assist the public with medication disposal.6,7 These options offer convenience and anonymity for the end user, reduce potential for diversion, and enhance patient safety by ridding homes of unwanted and expired medications.

Prior to the 2010 act, the only legal methods of controlled substance disposal were via trash disposal, flushing, or delivery to law enforcement, typically at a community-based drug take-back event. These methods were not always convenient, environmentally friendly, or safe for other family members and pets in the home. The Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 added 2 additional collection options for pharmacies: collection receptacles and mail-back programs.

The RLRVAMC treats > 62,000 veterans annually. The RLRVAMC Pharmacy Service had been providing pharmaceutical mail-back envelopes to patients since May 2015 with moderate success (271 lb of medications returned and a 22.8% envelope return rate through September 2016). Although the mail-back envelopes offer at-home convenience, there was no on-site disposal option. It is not uncommon for patients to bring medications to their appointment or the emergency department (ED). When medication reconciliation is performed, some medications are discontinued, and the prescriber wants them to be safely out of the patient’s possession to avoid confusion and/or accidental overdose. The purpose of this project was to offer more disposal options to patients through the addition of an on-site medication collection receptacle that would be in compliance with U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) regulations.

Methods

A policy was developed between the RLRVAMC pharmacy and police departments for the management of a medication collection receptacle. Police would oversee the disposal program so that the pharmacy would not have to change its DEA registration to collector status. The 2 access keys to the receptacle were maintained by police and secured within a key accountability system in the police station.

Full liners are removed from the receptacle by 2 police officers and sealed securely according to vendor guidelines. In accordance with DEA regulations, a form is completed that documents the dates the inner liner was acquired, installed, removed, and transferred for destruction as well as the unique identification number and size of the liner, the address of the location where it was installed, and the names and signatures of the 2 employees that witnessed the removal.

Arrangements are made to have a mail courier present during the removal of the liner. Once removed, the liner is immediately sealed and released to the mail courier who transports the liner to the DEA authorized reverse distributor. The reverse distributor is a licensed entity that has the authority to take control of the medications, including controlled substances, for disposal. The liner tracking numbers are kept in a police log book so that delivery can be confirmed and destruction certificates obtained from the vendor’s website at a later date. The records are kept for 3 years.

Funding was obtained for a 38-gallon collection receptacle and 12 liners from Pharmacy Benefits Management Services (PBM). Approval was obtained from RLRVAMC leadership to locate the receptacle in a high-traffic area, anchored to the floor, under video surveillance, and away from the ED entrance (a DEA requirement). Public Affairs promoted the receptacle to veterans. E-mails were sent to staff to provide education on regulatory requirements. Weight and frequency of medications returned were obtained from data collected by the reverse distributor. Descriptive statistics are reported.

Results

The Federal Supply Schedule cost to procure a DEA-compliant receptacle was $1,450. The additional 12 inner liners cost $2,024.97.8 Staff from Engineering Service were able to install the receptacle at no additional cost to the facility. The collection receptacle was opened to the public in May 2016. From May through October 2016, the facility collected and returned 10 liners to the reverse distributor containing 452 lb of medications. An additional 30 lb of drugs were returned through the mailback envelope program for a total weight of 482 lb over the 6-month period (Figure). The average time between inner liner changes was 2.6 weeks.

Discussion

The most challenging aspect of implementation was identification of a location for the receptacle. The location chosen, an alcove in the hallway between the coffee shop and outpatient pharmacy, was most appropriate. It is a high-traffic area, under video surveillance, and provides easy access for patients. Another challenge was determining the frequency of liner changes. There was no historic data to assist with predicting how quickly the liner would fill up. Initially, Police Service checked the receptacle every week, and it was emptied about every 2 weeks. Aspatients cleaned out their medicine cabinets, the liner needed to be replaced closer to every 4 weeks. An ongoing challenge has been determining how full the liner is without requiring the police to open the receptacle. Consideration is being given to installing a scale in the receptacle under the liner and having the display affixed to the outside of the container.

The receptacle seemed to be the preferred method of disposal, considering that it generated nearly 15 times more waste than did the mail-back envelopes during the same time period. Anecdotal patient feedback has been extremely positive on social media and by word-of-mouth.

Limitations

One limitation of this disposal program is that the specific amount of controlled substance waste vs noncontrolled substance waste cannot be determined since the liner contents are not inventoried. The University of Findlay in Ohio partnered with local law enforcement to host 7 community medication take-back events over a 3-year period, inventoried the drugs, and found that about one-third of the dosing units (eg, tablet or capsule) returned in the analgesic category were controlled substances, suggesting that take-back events may play a role in reducing unauthorized access to prescription painkillers.9 By witnessing the changing of inner liners, it can be anecdotally confirmed that a significant amount of controlled substances were collected and returned at RLRVAMC. These results have been shared with respective VISN leadership, and additional facilities are installing receptacles.

Conclusion

Changes to DEA regulations offer medical centers more options for developing a comprehensive drug disposal program. Implementation of a pharmaceutical take-back program can assist patients with disposal of unwanted and expired medications, promote safety and environmental stewardship, and reduce the risk of diversion.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html. Updated April 16, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49.

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Disposal of unused medicines: what you should know. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htm#Flush_List. Updated April 21, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2017.

4. Li WC. Occurrence, sources, and fate of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environment and soil. Environ Pollut. 2014;187:193-201.

5. Boxall AB. The environmental side effects of medication. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(12):1110-1116.

6. Peterson DM. New DEA rules expand options for controlled substance disposal. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(1):22-26.

7. U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug disposal information. https:// www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/index.html. Accessed June 5, 2016.

8. GSA Advantage! Online shopping. https://www.gsaadvantage.gov. Accessed June 5, 2017.

9. Perry LA, Shinn BW, Stanovich J. Quantification of an ongoing community-based medication take-back program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2014;54(3):275-279.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html. Updated April 16, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49.

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Disposal of unused medicines: what you should know. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htm#Flush_List. Updated April 21, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2017.

4. Li WC. Occurrence, sources, and fate of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environment and soil. Environ Pollut. 2014;187:193-201.

5. Boxall AB. The environmental side effects of medication. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(12):1110-1116.

6. Peterson DM. New DEA rules expand options for controlled substance disposal. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(1):22-26.

7. U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug disposal information. https:// www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/index.html. Accessed June 5, 2016.

8. GSA Advantage! Online shopping. https://www.gsaadvantage.gov. Accessed June 5, 2017.

9. Perry LA, Shinn BW, Stanovich J. Quantification of an ongoing community-based medication take-back program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2014;54(3):275-279.

Development of a Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference

The VHA is the nation’s largest provider of pharmacy residency programs offering > 150 programs.1 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) is the accreditation body for these pharmacy residency programs. One of the several ASHP residency standards is the presentation of a resident project at an annual conference.2,3 To meet the requirement, U.S. residency programs send pharmacy residents to regional conferences to present their projects.

Often only pharmacy residents and their project preceptors attend the regional conferences. Most pharmacists who work at each institution are not able to attend and do not have the opportunity to benefit from resident research directly related to the pharmacy profession and the facilities where the research is conducted.

Related: Treatment of Ampicillin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium Urinary Tract Infections

Reasons for not being able to attend these regional resident conferences include financial limitations as well as staffing and work requirements. The expenses associated with attending regional resident conferences include conference registration, transportation, lodging, meals, and other incidental expenses. These expenses could easily surpass several hundred dollars per attendee.

The requirements to obtain travel reimbursement for VHA employees to attend conferences for professional development have become increasingly more complex. This has presented the VHA with a unique challenge to provide its employees with professional development opportunities that do not require travel.

One option is to develop virtual learning environments, which eliminate the need for travel and conference-related expenses. Virtual learning has been a successful and convenient platform for professional development and has recently emerged within the pharmacy profession.4 In 2012, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy hosted its first Virtual Poster Symposium, which allowed participants to visit posters and interact with presenters online.5 At the VHA, pharmacists also have the opportunity to deliver and attend virtual presentations through the VA Learning University system.

To provide increased exposure and understanding to pharmacy resident research within the limitations of the VHA employee travel reimbursement system, a virtual pharmacy resident conference was developed. This article describes the steps taken to develop a conference and its impact on the pharmacists and pharmacy residents of VISN 11.

Methods

Planning for the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference started in June 2013 during the annual call for education programming from the VHA Employee Education System (EES). A proposal for the virtual conference, explaining its purpose and structure, was submitted to EES at that time, and approval was granted in August 2013.

Planning Process

Once approved, an EES representative provided guidance through the planning process and serve as a liaison between the planning committee and the desired educational accreditation body, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). For any educational program receiving continuing education (CE) credit from ACPE, an ACPE Planning Committee must be formed that includes a licensed pharmacist.6

The ACPE credit approval process then requires a needs assessment. The needs assessment identified a current gap within the profession and highlighted how the proposed education programming filled this gap. For the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference, the needs assessment included the challenges surrounding professional travel reimbursement and the missed learning opportunity for VA pharmacists who were not able to learn from resident research projects. Developing a virtual conference was proposed to fill this gap; pharmacists within the VISN could attend presentations from their workstations in order to stay abreast of pharmacy resident projects while gaining required CE hours for license renewal.

After the needs assessment was approved, a brochure and a content alignment worksheet was developed. The brochure identified the date and time of the conference, the target audience, and included a statement of purpose. The content alignment worksheet listed the program (presentation) title, the faculty delivering the presentation, and objectives. The completed brochure and content alignment worksheet was submitted to ACPE for credit hours approval. In the VHA, it is a VHA employee who coordinates ACPE activities for the entire health system.

Gaining Support

Another important step was to gain the support of VHA pharmacy leadership. In September 2013, an informational meeting was held to discuss the proposal and request feedback from the pharmacy chiefs, supervisors, and residency program directors at each facility within VISN 11. Following this meeting, each facility was given 1 month to determine whether the pharmacy residents at each respective facility would participate in the virtual conference. Once the planning committee had a final list of participating residents, an official announcement of the virtual conference was made to the pharmacy residents, chiefs of pharmacy, supervisors, and residency pharmacy directors.

Participating pharmacy residents submitted presentation titles to the ACPE planning committee and identified which of the 3 content tracks the research fell into: ambulatory care, acute care, or pharmacy administration. A presentation schedule was then developed.

VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to register for each of the presentations. Registration took place through the VHA Talent Management System. Presentations were delivered through Microsoft Lync (Redmond, WA), a web-based communication and conferencing platform. The VA eHealth University could have been used to achieve the same outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Presentation content breakdown and attendance rates from the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The comparison of attendance rates at the virtual conference with those expected for the regional face-to-face conference was analyzed using a single sample t test.

Results

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference took place May 5-7, 2014. Twenty-six of the 29 pharmacy residents in VISN 11 delivered 23 presentations. Three presentations had 2 presenters each, as these had completed their research as a team. Each presentation was approved by ACPE for 0.5 CE hours for a total of 11.5 CE hours available to participants.

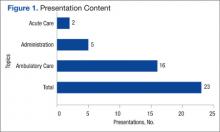

Of the 23 presentations, 16 (69.6%) focused on ambulatory care, 5 (21.7%) on pharmacy administration, and 2 (8.7%) on acute care (Figure 1). The ambulatory care presentations were divided into subgroups of diabetes (n = 6), mental health (n = 4), anticoagulation (n = 4), and cardiology (n = 2). Diabetes and cardiology presentations were delivered on day 1 of the conference, mental health and anticoagulation on day 2, and acute care and pharmacy administration on day 3.

A total of 386 VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to attend the virtual conference and 71 pharmacists (18.4%) registered for at least 1 presentation. VISN 11 pharmacy participation at the virtual conference was increased by 50% compared with the attendance at the 29th Annual Great Lakes Pharmacy Resident Conference, hosted by Purdue University, where only 47 VISN 11 pharmacists (12.2%) were expected to attend, based on results of a VISN-wide survey (95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.23; P < .001) (Figure 2).

On average, each participant attended 7 presentations and earned 3.5 hours of ACPE credit. Of the pharmacists who registered, 14 (19.7%) were pharmacy residents. Of note, registration was not required to deliver a presentation, which explains why the number of pharmacy residents registered to attend (14) was less than the number of pharmacy residents that delivered presentations (26).

More pharmacists registered for ambulatory care presentations (76.2%), followed by pharmacy administration (16.4%) and acute care (7.4%). These differences may be explained by the variability in the number of presentations within each content track. The registration for ambulatory care presentations, when stratified by content subgroup, was 45.7% for diabetes, 22.6% for mental health, 21.2% for anticoagulation, and 10.5% for cardiology.

The first day of the conference had the largest number of participants with 42.8% of all registrants, followed by 33.4% of registrants attending presentations on day 2 and 23.8% on day 3. The presentation with the largest number of registrants was in the diabetes subgroup, which was presented on the first day of the conference. The pharmacy administration presentation was held on the third and final day of the conference and had the lowest number of registrants. An average of 21.2 pharmacists registered for each presentation.

Discussion

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference was structured in a way that offered benefits to multiple groups. First, the virtual conference served as a medium for pharmacy residents to present their yearlong research projects and meet an ASHP residency requirement. Second, the virtual conference greatly expanded the audience size and potential impact of the presentations. Traditionally, resident research projects have been available to the few pharmacists who are able to attend an in-person conference. Almost 20% of all VISN 11 pharmacists were able to attend at least 1 presentation over the course of the 3-day conference. Attendance may increase as the virtual conference becomes more familiar to the VISN 11 pharmacy staff.

Access to a larger audience may help more pharmacists understand veteran-specific research. The information discovered through these research projects may be valuable to advance the clinical and administrative role of pharmacy within each facility as well as the entire VISN. Previously, staff pharmacists could not easily learn about resident research projects taking place at their local and neighboring VA facilities. In addition to the increased impact having a larger audience size also increases staff buy-in and feedback toward the projects.

Related:Non–Daily-Dosed Rosuvastatin in Statin-Intolerant Veterans

Individual VHA facilities frequently try to find ways to increase collaboration between VISN sites. The virtual conference format can help this collaboration. Sharing information between sites through a virtual conference may decrease duplication of projects across facilities, and each facility can learn from the mistakes of the others as well as the successes.

The VHA has a standing contract with ACPE, and therefore, registration fees were not required for this conference. For health systems that may not have such a contract, an ACPE registration fee may be required; however, this fee would still be considerably lower than the travel costs of an in-person conference.

Experience preparing and delivering a virtual presentation is useful for pharmacy residents. Delivering a virtual presentation offers its own set of challenges, such as learning how to engage an audience. Exposure to this type of public speaking may benefit residents as they progress on their career paths.

To prepare for this conference, a tutorial was created to help develop presentations. Residents were encouraged to learn how to not only deliver the presentation using the web conference technology, but also incorporate active learning exercises throughout the presentation to maximize involvement and engagement of the audience. For most resident presenters, this was the first experience delivering a virtual presentation.

Finally, a virtual conference format allows pharmacists to obtain ACPE credit hours required for license renewal.

In addition to the many benefits offered through virtual conferences, there are also some limitations. Many learners enjoy the personal element that comes with an in-person presentation. Although the use of webcams is available for virtual conferences, some of this human element may still be lost. Additionally, in-person conferences provide professional networking opportunities, which are not as readily available through virtual conferences.

The majority of presentations for this conference were related to ambulatory care, which is to be expected in a VHA setting, given the multitude of outpatient clinics in the VHA health system. Of ambulatory care presentations, most participants attended presentations that focused on diabetes or cardiology (day 1 of the conference).

However, some technology difficulties occurred on the first day of the conference, which might explain the decreased participation on subsequent days. Afternoon hours were selected as the time to host the virtual conference, because it was believed this would increase the opportunity for participation, as several pharmacists were expected to be unavailable in the morning hours due to increased workload and/or clinical responsibilities.

A follow-up questionnaire was available to participants after the conference. The majority of responses received indicated positive feedback in regards to the ease of conference participation, applicability of information gained to specific facilities, as well as availability of ACPE CE hours. In the future, the intent is to expand the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference to also include CE credit for pharmacy technicians, which requires some additional steps in the ACPE credit approval process. Also, presentations will be recorded and available either live or on-demand for CE credit.

Conclusion

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference was an innovative, educational program that allowed pharmacy residents to meet the ASHP requirement to present residency research at an annual conference, while also providing the opportunity for pharmacists to have a more encompassing understanding of research taking place within the VISN and meet their CE requirements.

The virtual conference format may be applied to any multisite health system where members from pharmacy services would benefit from the presentations. Last, pharmacy residents will gain new techniques and experience in developing and delivering a virtual presentation, which will prove be a useful skill set for the future.

Author Disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Discover more options with a VA pharmacy residency. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.vacareers.va.gov/careers/pharmacists /residency.asp. Updated January 2, 2014. Accessed June 8, 2015.

2. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Accreditation Standard For Postgraduate Year One (PGY1) Pharmacy Residency Programs. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Website. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-PGY1-Standard.aspx. Updated April 13, 2012. Accessed June 8, 2015.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Accreditation Standard For Postgraduate Year Two (PGY2) Pharmacy Residency Programs. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Website. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-PGY2-Standard.aspx. Updated April 13, 2012. Accessed June 8, 2015.

4. Sloan R. Poster presentations in the virtual world. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2012;43(11):485-486.

5. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Virtual poster symposium. American College of Clinical Pharmacy Website. http://www.accp.com/meetings/virtual.aspx. Accessed June 8, 2015.

6. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education, Version 2. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; 2007. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPE_Standards_Final.pdf. Updated March 2014. Accessed June 8, 2015.

The VHA is the nation’s largest provider of pharmacy residency programs offering > 150 programs.1 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) is the accreditation body for these pharmacy residency programs. One of the several ASHP residency standards is the presentation of a resident project at an annual conference.2,3 To meet the requirement, U.S. residency programs send pharmacy residents to regional conferences to present their projects.

Often only pharmacy residents and their project preceptors attend the regional conferences. Most pharmacists who work at each institution are not able to attend and do not have the opportunity to benefit from resident research directly related to the pharmacy profession and the facilities where the research is conducted.

Related: Treatment of Ampicillin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium Urinary Tract Infections

Reasons for not being able to attend these regional resident conferences include financial limitations as well as staffing and work requirements. The expenses associated with attending regional resident conferences include conference registration, transportation, lodging, meals, and other incidental expenses. These expenses could easily surpass several hundred dollars per attendee.

The requirements to obtain travel reimbursement for VHA employees to attend conferences for professional development have become increasingly more complex. This has presented the VHA with a unique challenge to provide its employees with professional development opportunities that do not require travel.

One option is to develop virtual learning environments, which eliminate the need for travel and conference-related expenses. Virtual learning has been a successful and convenient platform for professional development and has recently emerged within the pharmacy profession.4 In 2012, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy hosted its first Virtual Poster Symposium, which allowed participants to visit posters and interact with presenters online.5 At the VHA, pharmacists also have the opportunity to deliver and attend virtual presentations through the VA Learning University system.

To provide increased exposure and understanding to pharmacy resident research within the limitations of the VHA employee travel reimbursement system, a virtual pharmacy resident conference was developed. This article describes the steps taken to develop a conference and its impact on the pharmacists and pharmacy residents of VISN 11.

Methods

Planning for the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference started in June 2013 during the annual call for education programming from the VHA Employee Education System (EES). A proposal for the virtual conference, explaining its purpose and structure, was submitted to EES at that time, and approval was granted in August 2013.

Planning Process

Once approved, an EES representative provided guidance through the planning process and serve as a liaison between the planning committee and the desired educational accreditation body, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). For any educational program receiving continuing education (CE) credit from ACPE, an ACPE Planning Committee must be formed that includes a licensed pharmacist.6

The ACPE credit approval process then requires a needs assessment. The needs assessment identified a current gap within the profession and highlighted how the proposed education programming filled this gap. For the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference, the needs assessment included the challenges surrounding professional travel reimbursement and the missed learning opportunity for VA pharmacists who were not able to learn from resident research projects. Developing a virtual conference was proposed to fill this gap; pharmacists within the VISN could attend presentations from their workstations in order to stay abreast of pharmacy resident projects while gaining required CE hours for license renewal.

After the needs assessment was approved, a brochure and a content alignment worksheet was developed. The brochure identified the date and time of the conference, the target audience, and included a statement of purpose. The content alignment worksheet listed the program (presentation) title, the faculty delivering the presentation, and objectives. The completed brochure and content alignment worksheet was submitted to ACPE for credit hours approval. In the VHA, it is a VHA employee who coordinates ACPE activities for the entire health system.

Gaining Support

Another important step was to gain the support of VHA pharmacy leadership. In September 2013, an informational meeting was held to discuss the proposal and request feedback from the pharmacy chiefs, supervisors, and residency program directors at each facility within VISN 11. Following this meeting, each facility was given 1 month to determine whether the pharmacy residents at each respective facility would participate in the virtual conference. Once the planning committee had a final list of participating residents, an official announcement of the virtual conference was made to the pharmacy residents, chiefs of pharmacy, supervisors, and residency pharmacy directors.

Participating pharmacy residents submitted presentation titles to the ACPE planning committee and identified which of the 3 content tracks the research fell into: ambulatory care, acute care, or pharmacy administration. A presentation schedule was then developed.

VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to register for each of the presentations. Registration took place through the VHA Talent Management System. Presentations were delivered through Microsoft Lync (Redmond, WA), a web-based communication and conferencing platform. The VA eHealth University could have been used to achieve the same outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Presentation content breakdown and attendance rates from the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The comparison of attendance rates at the virtual conference with those expected for the regional face-to-face conference was analyzed using a single sample t test.

Results

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference took place May 5-7, 2014. Twenty-six of the 29 pharmacy residents in VISN 11 delivered 23 presentations. Three presentations had 2 presenters each, as these had completed their research as a team. Each presentation was approved by ACPE for 0.5 CE hours for a total of 11.5 CE hours available to participants.

Of the 23 presentations, 16 (69.6%) focused on ambulatory care, 5 (21.7%) on pharmacy administration, and 2 (8.7%) on acute care (Figure 1). The ambulatory care presentations were divided into subgroups of diabetes (n = 6), mental health (n = 4), anticoagulation (n = 4), and cardiology (n = 2). Diabetes and cardiology presentations were delivered on day 1 of the conference, mental health and anticoagulation on day 2, and acute care and pharmacy administration on day 3.

A total of 386 VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to attend the virtual conference and 71 pharmacists (18.4%) registered for at least 1 presentation. VISN 11 pharmacy participation at the virtual conference was increased by 50% compared with the attendance at the 29th Annual Great Lakes Pharmacy Resident Conference, hosted by Purdue University, where only 47 VISN 11 pharmacists (12.2%) were expected to attend, based on results of a VISN-wide survey (95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.23; P < .001) (Figure 2).

On average, each participant attended 7 presentations and earned 3.5 hours of ACPE credit. Of the pharmacists who registered, 14 (19.7%) were pharmacy residents. Of note, registration was not required to deliver a presentation, which explains why the number of pharmacy residents registered to attend (14) was less than the number of pharmacy residents that delivered presentations (26).

More pharmacists registered for ambulatory care presentations (76.2%), followed by pharmacy administration (16.4%) and acute care (7.4%). These differences may be explained by the variability in the number of presentations within each content track. The registration for ambulatory care presentations, when stratified by content subgroup, was 45.7% for diabetes, 22.6% for mental health, 21.2% for anticoagulation, and 10.5% for cardiology.

The first day of the conference had the largest number of participants with 42.8% of all registrants, followed by 33.4% of registrants attending presentations on day 2 and 23.8% on day 3. The presentation with the largest number of registrants was in the diabetes subgroup, which was presented on the first day of the conference. The pharmacy administration presentation was held on the third and final day of the conference and had the lowest number of registrants. An average of 21.2 pharmacists registered for each presentation.

Discussion

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference was structured in a way that offered benefits to multiple groups. First, the virtual conference served as a medium for pharmacy residents to present their yearlong research projects and meet an ASHP residency requirement. Second, the virtual conference greatly expanded the audience size and potential impact of the presentations. Traditionally, resident research projects have been available to the few pharmacists who are able to attend an in-person conference. Almost 20% of all VISN 11 pharmacists were able to attend at least 1 presentation over the course of the 3-day conference. Attendance may increase as the virtual conference becomes more familiar to the VISN 11 pharmacy staff.

Access to a larger audience may help more pharmacists understand veteran-specific research. The information discovered through these research projects may be valuable to advance the clinical and administrative role of pharmacy within each facility as well as the entire VISN. Previously, staff pharmacists could not easily learn about resident research projects taking place at their local and neighboring VA facilities. In addition to the increased impact having a larger audience size also increases staff buy-in and feedback toward the projects.

Related:Non–Daily-Dosed Rosuvastatin in Statin-Intolerant Veterans

Individual VHA facilities frequently try to find ways to increase collaboration between VISN sites. The virtual conference format can help this collaboration. Sharing information between sites through a virtual conference may decrease duplication of projects across facilities, and each facility can learn from the mistakes of the others as well as the successes.

The VHA has a standing contract with ACPE, and therefore, registration fees were not required for this conference. For health systems that may not have such a contract, an ACPE registration fee may be required; however, this fee would still be considerably lower than the travel costs of an in-person conference.

Experience preparing and delivering a virtual presentation is useful for pharmacy residents. Delivering a virtual presentation offers its own set of challenges, such as learning how to engage an audience. Exposure to this type of public speaking may benefit residents as they progress on their career paths.

To prepare for this conference, a tutorial was created to help develop presentations. Residents were encouraged to learn how to not only deliver the presentation using the web conference technology, but also incorporate active learning exercises throughout the presentation to maximize involvement and engagement of the audience. For most resident presenters, this was the first experience delivering a virtual presentation.

Finally, a virtual conference format allows pharmacists to obtain ACPE credit hours required for license renewal.

In addition to the many benefits offered through virtual conferences, there are also some limitations. Many learners enjoy the personal element that comes with an in-person presentation. Although the use of webcams is available for virtual conferences, some of this human element may still be lost. Additionally, in-person conferences provide professional networking opportunities, which are not as readily available through virtual conferences.

The majority of presentations for this conference were related to ambulatory care, which is to be expected in a VHA setting, given the multitude of outpatient clinics in the VHA health system. Of ambulatory care presentations, most participants attended presentations that focused on diabetes or cardiology (day 1 of the conference).

However, some technology difficulties occurred on the first day of the conference, which might explain the decreased participation on subsequent days. Afternoon hours were selected as the time to host the virtual conference, because it was believed this would increase the opportunity for participation, as several pharmacists were expected to be unavailable in the morning hours due to increased workload and/or clinical responsibilities.

A follow-up questionnaire was available to participants after the conference. The majority of responses received indicated positive feedback in regards to the ease of conference participation, applicability of information gained to specific facilities, as well as availability of ACPE CE hours. In the future, the intent is to expand the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference to also include CE credit for pharmacy technicians, which requires some additional steps in the ACPE credit approval process. Also, presentations will be recorded and available either live or on-demand for CE credit.

Conclusion

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference was an innovative, educational program that allowed pharmacy residents to meet the ASHP requirement to present residency research at an annual conference, while also providing the opportunity for pharmacists to have a more encompassing understanding of research taking place within the VISN and meet their CE requirements.

The virtual conference format may be applied to any multisite health system where members from pharmacy services would benefit from the presentations. Last, pharmacy residents will gain new techniques and experience in developing and delivering a virtual presentation, which will prove be a useful skill set for the future.

Author Disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The VHA is the nation’s largest provider of pharmacy residency programs offering > 150 programs.1 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) is the accreditation body for these pharmacy residency programs. One of the several ASHP residency standards is the presentation of a resident project at an annual conference.2,3 To meet the requirement, U.S. residency programs send pharmacy residents to regional conferences to present their projects.

Often only pharmacy residents and their project preceptors attend the regional conferences. Most pharmacists who work at each institution are not able to attend and do not have the opportunity to benefit from resident research directly related to the pharmacy profession and the facilities where the research is conducted.

Related: Treatment of Ampicillin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium Urinary Tract Infections

Reasons for not being able to attend these regional resident conferences include financial limitations as well as staffing and work requirements. The expenses associated with attending regional resident conferences include conference registration, transportation, lodging, meals, and other incidental expenses. These expenses could easily surpass several hundred dollars per attendee.

The requirements to obtain travel reimbursement for VHA employees to attend conferences for professional development have become increasingly more complex. This has presented the VHA with a unique challenge to provide its employees with professional development opportunities that do not require travel.

One option is to develop virtual learning environments, which eliminate the need for travel and conference-related expenses. Virtual learning has been a successful and convenient platform for professional development and has recently emerged within the pharmacy profession.4 In 2012, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy hosted its first Virtual Poster Symposium, which allowed participants to visit posters and interact with presenters online.5 At the VHA, pharmacists also have the opportunity to deliver and attend virtual presentations through the VA Learning University system.

To provide increased exposure and understanding to pharmacy resident research within the limitations of the VHA employee travel reimbursement system, a virtual pharmacy resident conference was developed. This article describes the steps taken to develop a conference and its impact on the pharmacists and pharmacy residents of VISN 11.

Methods

Planning for the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference started in June 2013 during the annual call for education programming from the VHA Employee Education System (EES). A proposal for the virtual conference, explaining its purpose and structure, was submitted to EES at that time, and approval was granted in August 2013.

Planning Process

Once approved, an EES representative provided guidance through the planning process and serve as a liaison between the planning committee and the desired educational accreditation body, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). For any educational program receiving continuing education (CE) credit from ACPE, an ACPE Planning Committee must be formed that includes a licensed pharmacist.6

The ACPE credit approval process then requires a needs assessment. The needs assessment identified a current gap within the profession and highlighted how the proposed education programming filled this gap. For the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference, the needs assessment included the challenges surrounding professional travel reimbursement and the missed learning opportunity for VA pharmacists who were not able to learn from resident research projects. Developing a virtual conference was proposed to fill this gap; pharmacists within the VISN could attend presentations from their workstations in order to stay abreast of pharmacy resident projects while gaining required CE hours for license renewal.

After the needs assessment was approved, a brochure and a content alignment worksheet was developed. The brochure identified the date and time of the conference, the target audience, and included a statement of purpose. The content alignment worksheet listed the program (presentation) title, the faculty delivering the presentation, and objectives. The completed brochure and content alignment worksheet was submitted to ACPE for credit hours approval. In the VHA, it is a VHA employee who coordinates ACPE activities for the entire health system.

Gaining Support

Another important step was to gain the support of VHA pharmacy leadership. In September 2013, an informational meeting was held to discuss the proposal and request feedback from the pharmacy chiefs, supervisors, and residency program directors at each facility within VISN 11. Following this meeting, each facility was given 1 month to determine whether the pharmacy residents at each respective facility would participate in the virtual conference. Once the planning committee had a final list of participating residents, an official announcement of the virtual conference was made to the pharmacy residents, chiefs of pharmacy, supervisors, and residency pharmacy directors.

Participating pharmacy residents submitted presentation titles to the ACPE planning committee and identified which of the 3 content tracks the research fell into: ambulatory care, acute care, or pharmacy administration. A presentation schedule was then developed.

VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to register for each of the presentations. Registration took place through the VHA Talent Management System. Presentations were delivered through Microsoft Lync (Redmond, WA), a web-based communication and conferencing platform. The VA eHealth University could have been used to achieve the same outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Presentation content breakdown and attendance rates from the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The comparison of attendance rates at the virtual conference with those expected for the regional face-to-face conference was analyzed using a single sample t test.

Results

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference took place May 5-7, 2014. Twenty-six of the 29 pharmacy residents in VISN 11 delivered 23 presentations. Three presentations had 2 presenters each, as these had completed their research as a team. Each presentation was approved by ACPE for 0.5 CE hours for a total of 11.5 CE hours available to participants.

Of the 23 presentations, 16 (69.6%) focused on ambulatory care, 5 (21.7%) on pharmacy administration, and 2 (8.7%) on acute care (Figure 1). The ambulatory care presentations were divided into subgroups of diabetes (n = 6), mental health (n = 4), anticoagulation (n = 4), and cardiology (n = 2). Diabetes and cardiology presentations were delivered on day 1 of the conference, mental health and anticoagulation on day 2, and acute care and pharmacy administration on day 3.

A total of 386 VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to attend the virtual conference and 71 pharmacists (18.4%) registered for at least 1 presentation. VISN 11 pharmacy participation at the virtual conference was increased by 50% compared with the attendance at the 29th Annual Great Lakes Pharmacy Resident Conference, hosted by Purdue University, where only 47 VISN 11 pharmacists (12.2%) were expected to attend, based on results of a VISN-wide survey (95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.23; P < .001) (Figure 2).

On average, each participant attended 7 presentations and earned 3.5 hours of ACPE credit. Of the pharmacists who registered, 14 (19.7%) were pharmacy residents. Of note, registration was not required to deliver a presentation, which explains why the number of pharmacy residents registered to attend (14) was less than the number of pharmacy residents that delivered presentations (26).

More pharmacists registered for ambulatory care presentations (76.2%), followed by pharmacy administration (16.4%) and acute care (7.4%). These differences may be explained by the variability in the number of presentations within each content track. The registration for ambulatory care presentations, when stratified by content subgroup, was 45.7% for diabetes, 22.6% for mental health, 21.2% for anticoagulation, and 10.5% for cardiology.

The first day of the conference had the largest number of participants with 42.8% of all registrants, followed by 33.4% of registrants attending presentations on day 2 and 23.8% on day 3. The presentation with the largest number of registrants was in the diabetes subgroup, which was presented on the first day of the conference. The pharmacy administration presentation was held on the third and final day of the conference and had the lowest number of registrants. An average of 21.2 pharmacists registered for each presentation.

Discussion

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference was structured in a way that offered benefits to multiple groups. First, the virtual conference served as a medium for pharmacy residents to present their yearlong research projects and meet an ASHP residency requirement. Second, the virtual conference greatly expanded the audience size and potential impact of the presentations. Traditionally, resident research projects have been available to the few pharmacists who are able to attend an in-person conference. Almost 20% of all VISN 11 pharmacists were able to attend at least 1 presentation over the course of the 3-day conference. Attendance may increase as the virtual conference becomes more familiar to the VISN 11 pharmacy staff.

Access to a larger audience may help more pharmacists understand veteran-specific research. The information discovered through these research projects may be valuable to advance the clinical and administrative role of pharmacy within each facility as well as the entire VISN. Previously, staff pharmacists could not easily learn about resident research projects taking place at their local and neighboring VA facilities. In addition to the increased impact having a larger audience size also increases staff buy-in and feedback toward the projects.

Related:Non–Daily-Dosed Rosuvastatin in Statin-Intolerant Veterans

Individual VHA facilities frequently try to find ways to increase collaboration between VISN sites. The virtual conference format can help this collaboration. Sharing information between sites through a virtual conference may decrease duplication of projects across facilities, and each facility can learn from the mistakes of the others as well as the successes.

The VHA has a standing contract with ACPE, and therefore, registration fees were not required for this conference. For health systems that may not have such a contract, an ACPE registration fee may be required; however, this fee would still be considerably lower than the travel costs of an in-person conference.

Experience preparing and delivering a virtual presentation is useful for pharmacy residents. Delivering a virtual presentation offers its own set of challenges, such as learning how to engage an audience. Exposure to this type of public speaking may benefit residents as they progress on their career paths.

To prepare for this conference, a tutorial was created to help develop presentations. Residents were encouraged to learn how to not only deliver the presentation using the web conference technology, but also incorporate active learning exercises throughout the presentation to maximize involvement and engagement of the audience. For most resident presenters, this was the first experience delivering a virtual presentation.

Finally, a virtual conference format allows pharmacists to obtain ACPE credit hours required for license renewal.

In addition to the many benefits offered through virtual conferences, there are also some limitations. Many learners enjoy the personal element that comes with an in-person presentation. Although the use of webcams is available for virtual conferences, some of this human element may still be lost. Additionally, in-person conferences provide professional networking opportunities, which are not as readily available through virtual conferences.

The majority of presentations for this conference were related to ambulatory care, which is to be expected in a VHA setting, given the multitude of outpatient clinics in the VHA health system. Of ambulatory care presentations, most participants attended presentations that focused on diabetes or cardiology (day 1 of the conference).

However, some technology difficulties occurred on the first day of the conference, which might explain the decreased participation on subsequent days. Afternoon hours were selected as the time to host the virtual conference, because it was believed this would increase the opportunity for participation, as several pharmacists were expected to be unavailable in the morning hours due to increased workload and/or clinical responsibilities.

A follow-up questionnaire was available to participants after the conference. The majority of responses received indicated positive feedback in regards to the ease of conference participation, applicability of information gained to specific facilities, as well as availability of ACPE CE hours. In the future, the intent is to expand the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference to also include CE credit for pharmacy technicians, which requires some additional steps in the ACPE credit approval process. Also, presentations will be recorded and available either live or on-demand for CE credit.

Conclusion

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference was an innovative, educational program that allowed pharmacy residents to meet the ASHP requirement to present residency research at an annual conference, while also providing the opportunity for pharmacists to have a more encompassing understanding of research taking place within the VISN and meet their CE requirements.

The virtual conference format may be applied to any multisite health system where members from pharmacy services would benefit from the presentations. Last, pharmacy residents will gain new techniques and experience in developing and delivering a virtual presentation, which will prove be a useful skill set for the future.

Author Disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Discover more options with a VA pharmacy residency. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.vacareers.va.gov/careers/pharmacists /residency.asp. Updated January 2, 2014. Accessed June 8, 2015.

2. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Accreditation Standard For Postgraduate Year One (PGY1) Pharmacy Residency Programs. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Website. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-PGY1-Standard.aspx. Updated April 13, 2012. Accessed June 8, 2015.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Accreditation Standard For Postgraduate Year Two (PGY2) Pharmacy Residency Programs. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Website. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-PGY2-Standard.aspx. Updated April 13, 2012. Accessed June 8, 2015.

4. Sloan R. Poster presentations in the virtual world. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2012;43(11):485-486.

5. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Virtual poster symposium. American College of Clinical Pharmacy Website. http://www.accp.com/meetings/virtual.aspx. Accessed June 8, 2015.

6. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education, Version 2. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; 2007. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPE_Standards_Final.pdf. Updated March 2014. Accessed June 8, 2015.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Discover more options with a VA pharmacy residency. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.vacareers.va.gov/careers/pharmacists /residency.asp. Updated January 2, 2014. Accessed June 8, 2015.

2. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Accreditation Standard For Postgraduate Year One (PGY1) Pharmacy Residency Programs. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Website. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-PGY1-Standard.aspx. Updated April 13, 2012. Accessed June 8, 2015.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Accreditation Standard For Postgraduate Year Two (PGY2) Pharmacy Residency Programs. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Website. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-PGY2-Standard.aspx. Updated April 13, 2012. Accessed June 8, 2015.

4. Sloan R. Poster presentations in the virtual world. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2012;43(11):485-486.

5. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Virtual poster symposium. American College of Clinical Pharmacy Website. http://www.accp.com/meetings/virtual.aspx. Accessed June 8, 2015.

6. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards for Continuing Pharmacy Education, Version 2. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; 2007. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPE_Standards_Final.pdf. Updated March 2014. Accessed June 8, 2015.