User login

Minimally invasive cesarean: Improving an innovative technique

- A simplified abdominal incision makes the traditional extensive dissection associated with the Pfannenstiel incision unnecessary.

- A soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor offers increased exposure, atraumatic retraction, incision protection, and adjustable height while facilitating delivery of the fetal head by creating a rigid border around the abdominal incision.

- Bladder-flap omission has been associated with reduced operative time and incision-delivery interval, decreased blood loss, and less need for postoperative analgesics.

Is the extensive dissection of the Pfannenstiel incision necessary in cesarean delivery? Is bladder dissection essential? Must the visceral and parietal peritoneum be closed?

The success of our minimally invasive cesarean technique suggests the answer is “no.”

The approach described here features a short operative time; minimal instrumentation; reduced surgical dissection; decreased postoperative pain; and reduced risk of blood loss, infection, and wound complications. It is easily learned and cost-effective, with a brief postoperative recovery period.

Among the updates made from the technique’s initial publication in the mid-1990s1,2:

- addition of routine perioperative oxygen (80%), to reduce the risk of surgical wound infection (see “Perioperative considerations”)

- regular use of forced warm air covers applied to the anterior skin surface, to help patients maintain normothermia

- addition of a soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor—which creates an atraumatic circle of exposure up to a calculated 177 cm2 for a 15-cm incision (versus 113 cm2 calculated for traditional retraction)

- vertical, rather than lateral, digital extension of the initial transverse uterine incision

- identification of a subgroup in whom peritoneal closure is strongly recommended

- new data on the procedure’s effectiveness.3

Routinely use prophylactic antibiotics. Several recent studies have concluded that perioperative antibiotics reduce the incidence of endometritis and wound infection following elective and nonelective cesarean section.37 Administer ampicillin or a first-generation cephalosporin at umbilical cord clamping. For patients allergic to penicillin and cephalosporins, choose an alternative, such as clindamycin.

Give antacids 30 minutes before anesthesia (general or regional) to prevent pneumonitis from inhalation of gastric contents.

Clip pubic hair, rather than shave, to reduce the risk of wound infection.

Insert a Foley catheter, empty the bladder, and keep the catheter in place.

Position the patient in a 10°left lateral tilt, to avoid hypotension associated with aortocaval occlusion.

Routinely administer supplemental perioperative oxygen (80%), with either general or regional anesthesia; this activates alveolar immune defenses and halves the risk of surgical wound infections.

Neutrophil oxidative killing and phagocytosis—the most important defenses against surgical pathogens—depend on the partial pressure of oxygen in contaminated tissue. Giving supplemental oxygen during and for the first 2 hours after the procedure (by mask) is a practical, inexpensive way to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection.38,39

Using 80% oxygen during and, for a short period, after surgery does not cause pulmonary toxicity such as atelectasis or impaired pulmonary function.40

Ensure normal body heat during and after cesarean to reduce the risk of postoperative surgical infection.40,41 Forced warm air covers applied to the anterior skin surface are the most effective way for warming surgical patients.9 IV fluid warming, though appropriate when large volumes are to be administered, is unnecessary for smaller operations.41

Modified abdominal incision reduces dissection

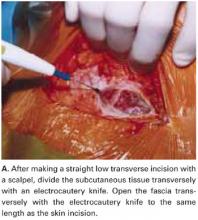

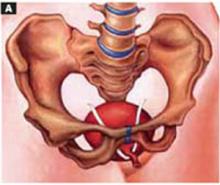

Make a straight low transverse incision with a scalpel, at a point approximately 3 to 4 cm above the symphysis pubis (FIGURE 1A).

The length of the incision is individualized (13 to 15 cm), though difficult fetal extraction is more likely if the abdominal incision is less than 15 cm.4,5

Divide the subcutaneous tissue transversely with an electrocautery knife. In a cutting and coagulation blend mode, the knife divides the fat while achieving hemostasis. To improve hemostasis, coagulate the blood vessels that cross the subcutaneous fat layer in a brushing manner before dividing them. To prevent unnecessary dead space, avoid filleting the fat and separating adherent subcutaneous fat from the anterior rectus fascia beyond what is needed to expose the fascia.

Open the fascia transversely with the electrocautery knife to the same length as the skin incision. Coagulate the blood vessels that cross the fascia before dividing them. Identify the median raphe by pulling up the superior edge of the abdominal incision.

Separate the rectus muscles in the midline by vertical blunt finger dissection (FIGURE 1B). If digital dissection is inefficient due to a dense, thick, or scarred median raphe, use an electrocautery knife, a scalpel, or scissors.

Open the peritoneum. This is facilitated by upward traction and elevation of the superior edge of the abdominal incision that lifts the peritoneum, allowing easy digital perforation using the index or middle finger (FIGURE 1C).

If this maneuver is not feasible, open the peritoneum in the traditional fashion.

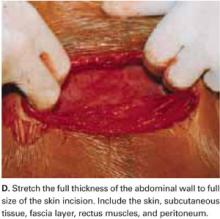

Stretch the full thickness of the abdominal wall to full size of the skin incision, using 1 or 2 fingers of each hand (FIGURE 1D). Incorporate the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia layer, rectus muscles, and peritoneum. An assistant’s hands may be required. When needed, extend the peritoneal opening transversely on either side, to the midline and away from the bladder.

Digitally stretching the full-thickness abdominal incision is easily achieved due to the mechanical stretching of the anterior abdominal wall, edema, and increased vascularization that occur during pregnancy.

FIGURE 1A Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1B Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1C Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1D Create a modified abdominal incision

Retractor facilitates exposure

Our positive experience with the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor for minilaparotomy and laparotomy6-8 compelled us to incorporate its use for cesarean 3 years ago.

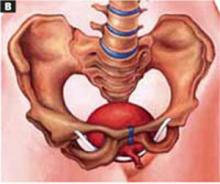

The device consists of a flexible plastic inner ring and a firmer outer ring connected by a soft plastic sleeve. We use the large size of either of the 2 models currently available: the Mobius (Apple Medical Corporation, Marlboro, Miss) and the Protractor (Weck Closure Systems, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Introduce a hand through the laparotomy incision and evaluate the pelvis to ensure that no significant adhesions are present that may interfere with swift placement of the inner ring. If significant adhesions are found, use traditional metal retractors instead.

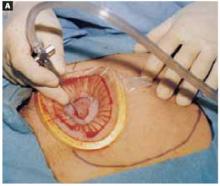

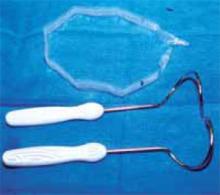

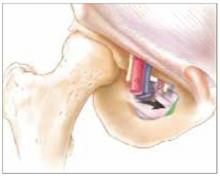

Squeeze the inner ring and insert it into the abdominal cavity toward the patient’s head, allowing the device to spring open against the parietal peritoneum (FIGURE 2A). Apply upper traction and elevate the superior edge of the abdominal incision to facilitate placement. Perform a digital check to ensure no tissue is trapped between the inner ring and the abdominal wall.

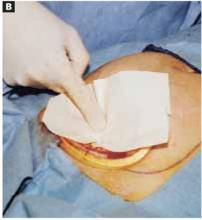

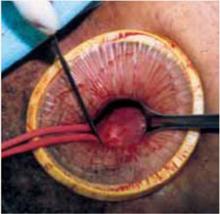

Hold up the outer ring, then roll the plastic sleeve until the ring completely inverts (FIGURE 2B). Repeat the process until the top ring is snug against the patient’s skin.

Advantages of the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor include atraumatic retraction; incision protection; and adjustable height, making it ideal for obese patients.

FIGURE 2A Place the abdominal retractor

FIGURE 2B Place the abdominal retractor

Transverse hysterotomy in lower uterine segment

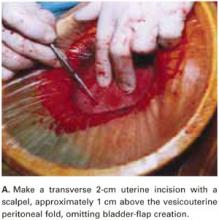

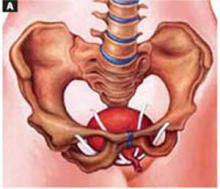

Make a transverse 2-cm uterine incision with a scalpel, approximately 1 cm above the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (identify this using gentle digital pressure to elevate the uterus) (FIGURE 3A).

Traditional bladder dissection is eliminated. We have found that when an adequate transverse hysterotomy is performed, a bladder flap is not required.1-3 In a recent randomized trial, Hohlagschwandtner et al9 confirmed our findings that bladder-flap omission was associated with reduced operative time and incision-delivery interval, decreased blood loss, and less need for postoperative analgesics.

An additional advantage of this omission: We can avoid making the uterine incision too low—especially when the cervix is fully dilated. Further, making the hysterotomy (uterine serosa and myometrium together) slightly above the vesicouterine peritoneal fold without bladder flap dissection frees the loose connective tissue between the uterus and the urinary bladder, allowing the spontaneous descent of the bladder.

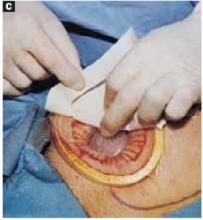

Digitally extend the transverse uterine incision. We extend the initial incision not laterally but, instead, vertically (FIGURE 3B). The vertical digital traction on the initial transverse uterine incision creates a transverse dissociation of the horizontal myometrium fibers; this results in a transverse extension of the original incision.

This modification prevents unintended and uncontrolled lateral extensions of the incision that may lacerate the uterine vessels.10 It also prevents the uterine incision from becoming an inverted “U” and the undesirable accumulation of myometrium fibers at the ends of the incision. Such incisions usually do not reapproximate well during hysterotomy closure and may lead to sacculation-type defects.11

FIGURE 3A Use a standard hysterotomy in the lower uterine segment

FIGURE 3B Use a standard hysterotomy in the lower uterine segment

Delivering the fetus

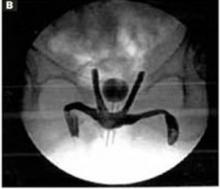

For vertex presentations, place your hand into the uterine cavity between the lower edge of the hysterotomy and fetal head. While applying transabdominal fundal pressure, lift the head with your fingers and deliver it through the incision (FIGURE 4A).

The self-retaining retractor facilitates delivery of the fetal head by creating a rigid border around the abdominal incision. The back of the surgeon’s hand that is in the uterine cavity achieves better leverage, as it now rests on a rigid plane on the inferior part of the incision rather than on the back hand and the softer and pliable wound edge of the standard abdominal incision.

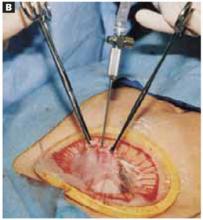

Vacuum-assistance. When delivery of the fetal head proves difficult, we use the soft vacuum cup, which avoids unnecessary intrauterine manipulation that may result in fetal or maternal trauma (FIGURE 4B).12

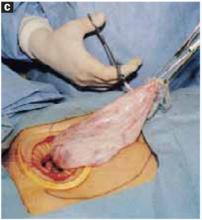

Breech extraction or transverse lie delivery is performed using standard extraction maneuvers (FIGURE 4C).13 We have found no need to perform T or J vertical extensions of the low transverse uterine incision, even in cases of a poorly developed lower uterine segment, abnormal presentation, or prematurity.

FIGURE 4A Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4B Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4C Deliver the fetal head

Uterine incision: 1-layer, in situ close

Remove the placenta only after it separates spontaneously—this greatly reduces blood loss compared with immediate manual placental delivery or umbilical-cord traction. Manually deliver the placenta only if it has not separated spontaneously after 5 minutes. Avoid routine manual clean-out of the uterine cavity if the placenta is completely delivered.1-3,14

Dilate the cervix to facilitate lochial discharge, when necessary.

Decrease uterine bleeding by massaging the uterus and administering diluted oxytocin.

Close the uterine incision in situ. Disadvantages of routine uterine exteriorization include discomfort and vomiting resulting from traction, exposure of the fallopian tubes to unnecessary trauma, increased risk of infection, possible rupture of the uteroovarian veins, and pulmonary embolism.

Exteriorization may also increase the risk of adhesion formation by exposing the uterine serosa to the abrasive effects of drying or microscopic abrasion if sponges are used to hold the uterus in place.1,14-17

Use a single-layer closure with a running suture of polyglycolic acid to close the uterine incision (FIGURE 5A). If needed, use atraumatic clamps to grasp the edges of the hysterotomy to facilitate visualization and closure.

Begin suturing at a point just beyond one end of the incision, continuing to the opposite side. Be sure to penetrate the full thickness of the myometrium and avoid incorporating the decidua in the suture line. After the uterine closure, use individual figure-of-8 sutures to control areas of persistent bleeding.

Compared with 2-layer closures, single-layer closure of a low transverse incision is associated with reduced operating time, improved hemostasis, and less tissue disruption; introduces less foreign material into the surgical site; reduces the need for postoperative analgesia; and potentially reduces infectious morbidity. A trial of labor after a cesarean section with 1-layer closure appears safe.18-22

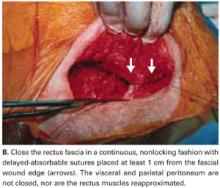

We do not close the vesicouterine fold and parietal peritoneum (FIGURE 5B) or reapproximate the rectus muscles. It has been shown that a new peritoneal layer is formed within days of the original incision closure.

Leaving the peritoneum open leads to no increased postoperative complications, nor obvious differences in wound healing, wound dehiscence, or incidence of postoperative adhesions. Compared to women without peritoneal closure, those with peritoneal closure require a longer operative time, greater amounts of post-operative narcotics for postoperative pain, a greater need for bowel stimulants, and a longer postoperative hospitalization.23

In 1995, we performed laparoscopy for gynecologic conditions in 23 patients and repeat cesarean in 10 patients who had undergone our technique (with visceral and parietal peritoneum left open).2 We found no adhesions and a normal peritoneal lining in all cases.

In 1 subgroup, peritoneal closure is strongly recommended: cases in which 1 or both rectus muscles have been transected to increase surgical exposure. Extremely thick fibromuscular adhesions between the low anterior surface of the uterus and the under-surface of the rectus musculature may develop if the parietal peritoneum is not closed.

FIGURE 5A Close the incisions

FIGURE 5B Close the incisions

Abdominal closure

Close the rectus fascia with a continuous nonlocking 0 suture after the rectus muscles fall into place. Place entry and exit sites at 1-cm intervals, 1.5 cm beyond the wound edges—this minimizes the risk of sutures pulling through fascia. Interrupted sutures offer no greater tensile strength than continuous suturing.24 Tight, continuous suturing can lead to tissue ischemia, which may weaken the sutured fascia, and thus should be avoided.

The subcutaneous layer is not closed separately. One exception is obese patients with at least 2 cm of thick subcutaneous tissue. Thickness of subcutaneous tissue appears to be a significant risk factor for wound infection after cesarean section.25

In patients with thick subcutaneous tissue, you can reduce tension on the skin edges and the risk of subcutaneous infection, seroma formation, and wound disruption by placing interrupted 3-0 absorbable synthetic sutures to eliminate dead space.26-28 We have found no need to place Penrose drains or closed drainage systems in the subcutaneous layer.29-31

Close the skin using a subcuticular continuous absorbable 4-0 suture or, alternatively, metal staples, which are removed 4 days after surgery (FIGURE 5C).

FIGURE 5C Close the incisions

Prompt postoperative recovery

The patient may drink fluids in the recovery room, can resume a regular solid food diet within 4 hours after surgery, and may resume mobility as soon as anesthesia wears off.

Early breast-feeding is also allowed in the recovery room. In our experience, this has not been associated with complications, has been highly appreciated by the patients, and has led to earlier hospital discharge.

Control pain with meperidine (50–75 mg) or morphine (10 mg) parenterally every 3 to 4 hours. Other options include oxycodone and acetaminophen, oxycodone and aspirin, and ibuprofen.

Patients are usually discharged 48 to 72 hours following surgery.

Our experience: The numbers

Using this updated system, we have successfully completed 300 consecutive cesarean sections (210 primary, 90 repeat).

The average operating time was 19 minutes; average blood loss, 405 mL.

There was no postoperative febrile morbidity, wound infection, wound disruption, or wound hematoma.Only 3 patients developed superficial wound seromas, which were easily resolved. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications.

We attribute the absence of wound infection to routine prophylactic antibiotics; supplemental perioperative oxygen; maintenance of normothermia; use of an electrocautery knife to create rapid hemostatic division of subcutaneous fat and anterior rectus fascia; a simplified abdominal wall opening; and placement of a self-retaining atraumatic retractor.10,32-36

Additional surgical procedures (tubal sterilization, myomectomy, appendectomy, and adhesiolysis) did not alter the recovery period, and all patients were able to get out of bed, shower, breast-feed, and care for their infants within 8 hours of surgery.

No infant complications related to the cesarean procedure occurred.

Patients were discharged from the hospital within 72 hours.

A prospective comparison study demonstrated that the original Pelosi-type of cesarean delivery was faster to perform, more cost-effective, and resulted in less maternal morbidity than the traditional cesarean technique.3

Dr. Pelosi II is a consultant for Apple Medical Corporation. Dr. Pelosi III reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Pelosi MA, Ortega I. Cesarean section: Pelosi simplified technique. Rev Chil Obstet Gynecol. 1994;59:372-377.

2. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Simplified cesarean section. Contemp OB/GYN. 1995;40:89-100.

3. Wood RM, Simon H, Oz AU. Pelosi-type vs traditional cesarean delivery: a prospective comparison. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:788-795.

4. Finan MA, Mastrogiannis DS, Spellacy WN. The “Allis” test for easy cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:772-775.

5. Ayers IW, Morley GW. Surgical incision for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:706-712.

6. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Self-retaining abdominal retractor for minilaparotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:775-778.

7. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: Effective alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. OBG Manag. April 2003;16-33.

8. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. A novel minilaparotomy approach for large ovarian cysts. OBG Manag. February 2004:;17-30.

9. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, et al. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1089-1092.

10. Ferrari A, Frigerio L, Origoni M, et al. Modified Stark procedure for cesarean section. J Pelv Surg. 1996;2:239-244.

11. Field CS. Surgical techniques for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Amer. 1988;15:657-672.

12. Pelosi MA, Apuzzio J. Use of the soft, silicone obstetric vacuum cup for delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:289-292.

13. Pelosi MA, Apuzzio J, Fricchione D, et al. The intra-abdominal version technique for delivery of transverse lie by low segment cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:1009-1012.

14. Magann EF, Dodson MK, Albert JR, et al. Blood loss at the time of cesarean section by method of placental removal and exteriorization versus in situ repair of the uterine incision. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:389-392.

15. Stock RJ, Shelton H. Fatal pulmonary embolism occurring 2 hours after exteriorization of the uterus for repair following cesareans section. Milit Med. 1985;150:549-550.

16. Hershey DW, Quilligan EJ. Extra-abdominal uterine exteriorization at cesarean section. Obstet Genecol. 1978;52:189-191.

17. Wahab MA, Karantzis P, Eccersley PS, et al. A randomized, controlled study of uterine exteriorization and repair at cesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;106:913-916.

18. Hauth JC, Owen J, Davis RO. Transverse uterine incision closure: one versus two layers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1108-1111.

19. Ohel G, Younis JS, Lang N, et al. Double-layer closure of uterine incision with visceral and parietal peritoneal closure: Are they obligatory steps of routine cesarean sections? J Matern Fetal Med. 1996;5:366-369.

20. Tucker JM, Hauth JC, Hodgkins P, et al. Trial of labor after a one- or two-layer closure of a low transverse uterine incision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:545-546.

21. Chapman SJ, Owen J, Hauth JC. One- versus two-layer closure of a low transverse cesarean: the next pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:16-18.

22. Jelsema RD, Wittinger JA, Vander Kolk KJ. Continuous, nonlocking, single-layer repair of the low transverse uterine incision. J Reprod Med. 1993;38:393-396.

23. Tulandi T, Al-Jaroudi D. Nonclosure of peritoneum: a reappraisal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:609-612.

24. Fagniez PL, Hay JM, Lacaine F. Abdominal midline incision closure. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1351-1355.

25. Vermillion ST, Lamoutte C, Soper DE, et al. Wound infection after cesarean: effect of subcutaneous tissue thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:923-926.

26. Naumann RW, Hauth JC, Owen J, et al. Subcutaneous tissue approximation in relation to wound disruption after cesarean delivery in obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:412-416.

27. Cetin A, Cetin M. Superficial wound disruption after cesarean delivery: effect of the depth and closure of subcutaneous tissue. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;57:17-21.

28. Del Valle GO, Combs P, Qualls C, et al. Does closure of Camper fascia reduce the incidence of post-cesarean superficial wound disruption? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1013-1016.

29. Loong RL, Rogers MS, Chang AM. A controlled trial of wound drainage at cesarean section. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;28:266-269.

30. Saunders NJ, Barclay C. Closed suction wound drainage and lower-segment cesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95:1060-1062.

31. Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Rodts-Palenik S, Bufkin L, Martin JN, Jr, Morrison JC. Subcutaneous stitch closure versus subcutaneous drain to prevent wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1119-1123.

32. Stark M, Finkel AR. Comparison between the Joel-Cohen and Pfannenstiel incisions in cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;53:121-122.

33. Joel-Cohen S. Abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy. New techniques based on time and motion studies. London, England: William Heinemann Medical Books; 1972.

34. Hemsell DL, Hemsell PG, Nobles B, et al. Abdominal wound problems after hysterectomy with electrocautery versus scalpel subcutaneous incision. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1993;1:27-30.

35. Johnson CD, Serpell JW. Wound infection after abdominal incision with scalpel or diathermy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:626-629.

36. Hussain SA, Hussain S. Incisions with knife or diathermy and postoperative pain. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1179-1182.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians-gynecologists. No. 43, May, 2003. Management of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1039-1047.

38. Greif R, Akca O, Hurn E-P, et al. Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:161-167.

39. Sorensen LT, Karlsmark T, Gottrup F. Abstinence from smoking reduces incisional wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238:1-5.

40. Sessler DI, Akca O. Preventing surgical site infections without drugs. Contemp OB/GYN. 2004;49:78-87.

41. Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection and shorten hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209-1215.

- A simplified abdominal incision makes the traditional extensive dissection associated with the Pfannenstiel incision unnecessary.

- A soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor offers increased exposure, atraumatic retraction, incision protection, and adjustable height while facilitating delivery of the fetal head by creating a rigid border around the abdominal incision.

- Bladder-flap omission has been associated with reduced operative time and incision-delivery interval, decreased blood loss, and less need for postoperative analgesics.

Is the extensive dissection of the Pfannenstiel incision necessary in cesarean delivery? Is bladder dissection essential? Must the visceral and parietal peritoneum be closed?

The success of our minimally invasive cesarean technique suggests the answer is “no.”

The approach described here features a short operative time; minimal instrumentation; reduced surgical dissection; decreased postoperative pain; and reduced risk of blood loss, infection, and wound complications. It is easily learned and cost-effective, with a brief postoperative recovery period.

Among the updates made from the technique’s initial publication in the mid-1990s1,2:

- addition of routine perioperative oxygen (80%), to reduce the risk of surgical wound infection (see “Perioperative considerations”)

- regular use of forced warm air covers applied to the anterior skin surface, to help patients maintain normothermia

- addition of a soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor—which creates an atraumatic circle of exposure up to a calculated 177 cm2 for a 15-cm incision (versus 113 cm2 calculated for traditional retraction)

- vertical, rather than lateral, digital extension of the initial transverse uterine incision

- identification of a subgroup in whom peritoneal closure is strongly recommended

- new data on the procedure’s effectiveness.3

Routinely use prophylactic antibiotics. Several recent studies have concluded that perioperative antibiotics reduce the incidence of endometritis and wound infection following elective and nonelective cesarean section.37 Administer ampicillin or a first-generation cephalosporin at umbilical cord clamping. For patients allergic to penicillin and cephalosporins, choose an alternative, such as clindamycin.

Give antacids 30 minutes before anesthesia (general or regional) to prevent pneumonitis from inhalation of gastric contents.

Clip pubic hair, rather than shave, to reduce the risk of wound infection.

Insert a Foley catheter, empty the bladder, and keep the catheter in place.

Position the patient in a 10°left lateral tilt, to avoid hypotension associated with aortocaval occlusion.

Routinely administer supplemental perioperative oxygen (80%), with either general or regional anesthesia; this activates alveolar immune defenses and halves the risk of surgical wound infections.

Neutrophil oxidative killing and phagocytosis—the most important defenses against surgical pathogens—depend on the partial pressure of oxygen in contaminated tissue. Giving supplemental oxygen during and for the first 2 hours after the procedure (by mask) is a practical, inexpensive way to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection.38,39

Using 80% oxygen during and, for a short period, after surgery does not cause pulmonary toxicity such as atelectasis or impaired pulmonary function.40

Ensure normal body heat during and after cesarean to reduce the risk of postoperative surgical infection.40,41 Forced warm air covers applied to the anterior skin surface are the most effective way for warming surgical patients.9 IV fluid warming, though appropriate when large volumes are to be administered, is unnecessary for smaller operations.41

Modified abdominal incision reduces dissection

Make a straight low transverse incision with a scalpel, at a point approximately 3 to 4 cm above the symphysis pubis (FIGURE 1A).

The length of the incision is individualized (13 to 15 cm), though difficult fetal extraction is more likely if the abdominal incision is less than 15 cm.4,5

Divide the subcutaneous tissue transversely with an electrocautery knife. In a cutting and coagulation blend mode, the knife divides the fat while achieving hemostasis. To improve hemostasis, coagulate the blood vessels that cross the subcutaneous fat layer in a brushing manner before dividing them. To prevent unnecessary dead space, avoid filleting the fat and separating adherent subcutaneous fat from the anterior rectus fascia beyond what is needed to expose the fascia.

Open the fascia transversely with the electrocautery knife to the same length as the skin incision. Coagulate the blood vessels that cross the fascia before dividing them. Identify the median raphe by pulling up the superior edge of the abdominal incision.

Separate the rectus muscles in the midline by vertical blunt finger dissection (FIGURE 1B). If digital dissection is inefficient due to a dense, thick, or scarred median raphe, use an electrocautery knife, a scalpel, or scissors.

Open the peritoneum. This is facilitated by upward traction and elevation of the superior edge of the abdominal incision that lifts the peritoneum, allowing easy digital perforation using the index or middle finger (FIGURE 1C).

If this maneuver is not feasible, open the peritoneum in the traditional fashion.

Stretch the full thickness of the abdominal wall to full size of the skin incision, using 1 or 2 fingers of each hand (FIGURE 1D). Incorporate the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia layer, rectus muscles, and peritoneum. An assistant’s hands may be required. When needed, extend the peritoneal opening transversely on either side, to the midline and away from the bladder.

Digitally stretching the full-thickness abdominal incision is easily achieved due to the mechanical stretching of the anterior abdominal wall, edema, and increased vascularization that occur during pregnancy.

FIGURE 1A Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1B Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1C Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1D Create a modified abdominal incision

Retractor facilitates exposure

Our positive experience with the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor for minilaparotomy and laparotomy6-8 compelled us to incorporate its use for cesarean 3 years ago.

The device consists of a flexible plastic inner ring and a firmer outer ring connected by a soft plastic sleeve. We use the large size of either of the 2 models currently available: the Mobius (Apple Medical Corporation, Marlboro, Miss) and the Protractor (Weck Closure Systems, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Introduce a hand through the laparotomy incision and evaluate the pelvis to ensure that no significant adhesions are present that may interfere with swift placement of the inner ring. If significant adhesions are found, use traditional metal retractors instead.

Squeeze the inner ring and insert it into the abdominal cavity toward the patient’s head, allowing the device to spring open against the parietal peritoneum (FIGURE 2A). Apply upper traction and elevate the superior edge of the abdominal incision to facilitate placement. Perform a digital check to ensure no tissue is trapped between the inner ring and the abdominal wall.

Hold up the outer ring, then roll the plastic sleeve until the ring completely inverts (FIGURE 2B). Repeat the process until the top ring is snug against the patient’s skin.

Advantages of the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor include atraumatic retraction; incision protection; and adjustable height, making it ideal for obese patients.

FIGURE 2A Place the abdominal retractor

FIGURE 2B Place the abdominal retractor

Transverse hysterotomy in lower uterine segment

Make a transverse 2-cm uterine incision with a scalpel, approximately 1 cm above the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (identify this using gentle digital pressure to elevate the uterus) (FIGURE 3A).

Traditional bladder dissection is eliminated. We have found that when an adequate transverse hysterotomy is performed, a bladder flap is not required.1-3 In a recent randomized trial, Hohlagschwandtner et al9 confirmed our findings that bladder-flap omission was associated with reduced operative time and incision-delivery interval, decreased blood loss, and less need for postoperative analgesics.

An additional advantage of this omission: We can avoid making the uterine incision too low—especially when the cervix is fully dilated. Further, making the hysterotomy (uterine serosa and myometrium together) slightly above the vesicouterine peritoneal fold without bladder flap dissection frees the loose connective tissue between the uterus and the urinary bladder, allowing the spontaneous descent of the bladder.

Digitally extend the transverse uterine incision. We extend the initial incision not laterally but, instead, vertically (FIGURE 3B). The vertical digital traction on the initial transverse uterine incision creates a transverse dissociation of the horizontal myometrium fibers; this results in a transverse extension of the original incision.

This modification prevents unintended and uncontrolled lateral extensions of the incision that may lacerate the uterine vessels.10 It also prevents the uterine incision from becoming an inverted “U” and the undesirable accumulation of myometrium fibers at the ends of the incision. Such incisions usually do not reapproximate well during hysterotomy closure and may lead to sacculation-type defects.11

FIGURE 3A Use a standard hysterotomy in the lower uterine segment

FIGURE 3B Use a standard hysterotomy in the lower uterine segment

Delivering the fetus

For vertex presentations, place your hand into the uterine cavity between the lower edge of the hysterotomy and fetal head. While applying transabdominal fundal pressure, lift the head with your fingers and deliver it through the incision (FIGURE 4A).

The self-retaining retractor facilitates delivery of the fetal head by creating a rigid border around the abdominal incision. The back of the surgeon’s hand that is in the uterine cavity achieves better leverage, as it now rests on a rigid plane on the inferior part of the incision rather than on the back hand and the softer and pliable wound edge of the standard abdominal incision.

Vacuum-assistance. When delivery of the fetal head proves difficult, we use the soft vacuum cup, which avoids unnecessary intrauterine manipulation that may result in fetal or maternal trauma (FIGURE 4B).12

Breech extraction or transverse lie delivery is performed using standard extraction maneuvers (FIGURE 4C).13 We have found no need to perform T or J vertical extensions of the low transverse uterine incision, even in cases of a poorly developed lower uterine segment, abnormal presentation, or prematurity.

FIGURE 4A Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4B Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4C Deliver the fetal head

Uterine incision: 1-layer, in situ close

Remove the placenta only after it separates spontaneously—this greatly reduces blood loss compared with immediate manual placental delivery or umbilical-cord traction. Manually deliver the placenta only if it has not separated spontaneously after 5 minutes. Avoid routine manual clean-out of the uterine cavity if the placenta is completely delivered.1-3,14

Dilate the cervix to facilitate lochial discharge, when necessary.

Decrease uterine bleeding by massaging the uterus and administering diluted oxytocin.

Close the uterine incision in situ. Disadvantages of routine uterine exteriorization include discomfort and vomiting resulting from traction, exposure of the fallopian tubes to unnecessary trauma, increased risk of infection, possible rupture of the uteroovarian veins, and pulmonary embolism.

Exteriorization may also increase the risk of adhesion formation by exposing the uterine serosa to the abrasive effects of drying or microscopic abrasion if sponges are used to hold the uterus in place.1,14-17

Use a single-layer closure with a running suture of polyglycolic acid to close the uterine incision (FIGURE 5A). If needed, use atraumatic clamps to grasp the edges of the hysterotomy to facilitate visualization and closure.

Begin suturing at a point just beyond one end of the incision, continuing to the opposite side. Be sure to penetrate the full thickness of the myometrium and avoid incorporating the decidua in the suture line. After the uterine closure, use individual figure-of-8 sutures to control areas of persistent bleeding.

Compared with 2-layer closures, single-layer closure of a low transverse incision is associated with reduced operating time, improved hemostasis, and less tissue disruption; introduces less foreign material into the surgical site; reduces the need for postoperative analgesia; and potentially reduces infectious morbidity. A trial of labor after a cesarean section with 1-layer closure appears safe.18-22

We do not close the vesicouterine fold and parietal peritoneum (FIGURE 5B) or reapproximate the rectus muscles. It has been shown that a new peritoneal layer is formed within days of the original incision closure.

Leaving the peritoneum open leads to no increased postoperative complications, nor obvious differences in wound healing, wound dehiscence, or incidence of postoperative adhesions. Compared to women without peritoneal closure, those with peritoneal closure require a longer operative time, greater amounts of post-operative narcotics for postoperative pain, a greater need for bowel stimulants, and a longer postoperative hospitalization.23

In 1995, we performed laparoscopy for gynecologic conditions in 23 patients and repeat cesarean in 10 patients who had undergone our technique (with visceral and parietal peritoneum left open).2 We found no adhesions and a normal peritoneal lining in all cases.

In 1 subgroup, peritoneal closure is strongly recommended: cases in which 1 or both rectus muscles have been transected to increase surgical exposure. Extremely thick fibromuscular adhesions between the low anterior surface of the uterus and the under-surface of the rectus musculature may develop if the parietal peritoneum is not closed.

FIGURE 5A Close the incisions

FIGURE 5B Close the incisions

Abdominal closure

Close the rectus fascia with a continuous nonlocking 0 suture after the rectus muscles fall into place. Place entry and exit sites at 1-cm intervals, 1.5 cm beyond the wound edges—this minimizes the risk of sutures pulling through fascia. Interrupted sutures offer no greater tensile strength than continuous suturing.24 Tight, continuous suturing can lead to tissue ischemia, which may weaken the sutured fascia, and thus should be avoided.

The subcutaneous layer is not closed separately. One exception is obese patients with at least 2 cm of thick subcutaneous tissue. Thickness of subcutaneous tissue appears to be a significant risk factor for wound infection after cesarean section.25

In patients with thick subcutaneous tissue, you can reduce tension on the skin edges and the risk of subcutaneous infection, seroma formation, and wound disruption by placing interrupted 3-0 absorbable synthetic sutures to eliminate dead space.26-28 We have found no need to place Penrose drains or closed drainage systems in the subcutaneous layer.29-31

Close the skin using a subcuticular continuous absorbable 4-0 suture or, alternatively, metal staples, which are removed 4 days after surgery (FIGURE 5C).

FIGURE 5C Close the incisions

Prompt postoperative recovery

The patient may drink fluids in the recovery room, can resume a regular solid food diet within 4 hours after surgery, and may resume mobility as soon as anesthesia wears off.

Early breast-feeding is also allowed in the recovery room. In our experience, this has not been associated with complications, has been highly appreciated by the patients, and has led to earlier hospital discharge.

Control pain with meperidine (50–75 mg) or morphine (10 mg) parenterally every 3 to 4 hours. Other options include oxycodone and acetaminophen, oxycodone and aspirin, and ibuprofen.

Patients are usually discharged 48 to 72 hours following surgery.

Our experience: The numbers

Using this updated system, we have successfully completed 300 consecutive cesarean sections (210 primary, 90 repeat).

The average operating time was 19 minutes; average blood loss, 405 mL.

There was no postoperative febrile morbidity, wound infection, wound disruption, or wound hematoma.Only 3 patients developed superficial wound seromas, which were easily resolved. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications.

We attribute the absence of wound infection to routine prophylactic antibiotics; supplemental perioperative oxygen; maintenance of normothermia; use of an electrocautery knife to create rapid hemostatic division of subcutaneous fat and anterior rectus fascia; a simplified abdominal wall opening; and placement of a self-retaining atraumatic retractor.10,32-36

Additional surgical procedures (tubal sterilization, myomectomy, appendectomy, and adhesiolysis) did not alter the recovery period, and all patients were able to get out of bed, shower, breast-feed, and care for their infants within 8 hours of surgery.

No infant complications related to the cesarean procedure occurred.

Patients were discharged from the hospital within 72 hours.

A prospective comparison study demonstrated that the original Pelosi-type of cesarean delivery was faster to perform, more cost-effective, and resulted in less maternal morbidity than the traditional cesarean technique.3

Dr. Pelosi II is a consultant for Apple Medical Corporation. Dr. Pelosi III reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- A simplified abdominal incision makes the traditional extensive dissection associated with the Pfannenstiel incision unnecessary.

- A soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor offers increased exposure, atraumatic retraction, incision protection, and adjustable height while facilitating delivery of the fetal head by creating a rigid border around the abdominal incision.

- Bladder-flap omission has been associated with reduced operative time and incision-delivery interval, decreased blood loss, and less need for postoperative analgesics.

Is the extensive dissection of the Pfannenstiel incision necessary in cesarean delivery? Is bladder dissection essential? Must the visceral and parietal peritoneum be closed?

The success of our minimally invasive cesarean technique suggests the answer is “no.”

The approach described here features a short operative time; minimal instrumentation; reduced surgical dissection; decreased postoperative pain; and reduced risk of blood loss, infection, and wound complications. It is easily learned and cost-effective, with a brief postoperative recovery period.

Among the updates made from the technique’s initial publication in the mid-1990s1,2:

- addition of routine perioperative oxygen (80%), to reduce the risk of surgical wound infection (see “Perioperative considerations”)

- regular use of forced warm air covers applied to the anterior skin surface, to help patients maintain normothermia

- addition of a soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor—which creates an atraumatic circle of exposure up to a calculated 177 cm2 for a 15-cm incision (versus 113 cm2 calculated for traditional retraction)

- vertical, rather than lateral, digital extension of the initial transverse uterine incision

- identification of a subgroup in whom peritoneal closure is strongly recommended

- new data on the procedure’s effectiveness.3

Routinely use prophylactic antibiotics. Several recent studies have concluded that perioperative antibiotics reduce the incidence of endometritis and wound infection following elective and nonelective cesarean section.37 Administer ampicillin or a first-generation cephalosporin at umbilical cord clamping. For patients allergic to penicillin and cephalosporins, choose an alternative, such as clindamycin.

Give antacids 30 minutes before anesthesia (general or regional) to prevent pneumonitis from inhalation of gastric contents.

Clip pubic hair, rather than shave, to reduce the risk of wound infection.

Insert a Foley catheter, empty the bladder, and keep the catheter in place.

Position the patient in a 10°left lateral tilt, to avoid hypotension associated with aortocaval occlusion.

Routinely administer supplemental perioperative oxygen (80%), with either general or regional anesthesia; this activates alveolar immune defenses and halves the risk of surgical wound infections.

Neutrophil oxidative killing and phagocytosis—the most important defenses against surgical pathogens—depend on the partial pressure of oxygen in contaminated tissue. Giving supplemental oxygen during and for the first 2 hours after the procedure (by mask) is a practical, inexpensive way to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection.38,39

Using 80% oxygen during and, for a short period, after surgery does not cause pulmonary toxicity such as atelectasis or impaired pulmonary function.40

Ensure normal body heat during and after cesarean to reduce the risk of postoperative surgical infection.40,41 Forced warm air covers applied to the anterior skin surface are the most effective way for warming surgical patients.9 IV fluid warming, though appropriate when large volumes are to be administered, is unnecessary for smaller operations.41

Modified abdominal incision reduces dissection

Make a straight low transverse incision with a scalpel, at a point approximately 3 to 4 cm above the symphysis pubis (FIGURE 1A).

The length of the incision is individualized (13 to 15 cm), though difficult fetal extraction is more likely if the abdominal incision is less than 15 cm.4,5

Divide the subcutaneous tissue transversely with an electrocautery knife. In a cutting and coagulation blend mode, the knife divides the fat while achieving hemostasis. To improve hemostasis, coagulate the blood vessels that cross the subcutaneous fat layer in a brushing manner before dividing them. To prevent unnecessary dead space, avoid filleting the fat and separating adherent subcutaneous fat from the anterior rectus fascia beyond what is needed to expose the fascia.

Open the fascia transversely with the electrocautery knife to the same length as the skin incision. Coagulate the blood vessels that cross the fascia before dividing them. Identify the median raphe by pulling up the superior edge of the abdominal incision.

Separate the rectus muscles in the midline by vertical blunt finger dissection (FIGURE 1B). If digital dissection is inefficient due to a dense, thick, or scarred median raphe, use an electrocautery knife, a scalpel, or scissors.

Open the peritoneum. This is facilitated by upward traction and elevation of the superior edge of the abdominal incision that lifts the peritoneum, allowing easy digital perforation using the index or middle finger (FIGURE 1C).

If this maneuver is not feasible, open the peritoneum in the traditional fashion.

Stretch the full thickness of the abdominal wall to full size of the skin incision, using 1 or 2 fingers of each hand (FIGURE 1D). Incorporate the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia layer, rectus muscles, and peritoneum. An assistant’s hands may be required. When needed, extend the peritoneal opening transversely on either side, to the midline and away from the bladder.

Digitally stretching the full-thickness abdominal incision is easily achieved due to the mechanical stretching of the anterior abdominal wall, edema, and increased vascularization that occur during pregnancy.

FIGURE 1A Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1B Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1C Create a modified abdominal incision

FIGURE 1D Create a modified abdominal incision

Retractor facilitates exposure

Our positive experience with the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor for minilaparotomy and laparotomy6-8 compelled us to incorporate its use for cesarean 3 years ago.

The device consists of a flexible plastic inner ring and a firmer outer ring connected by a soft plastic sleeve. We use the large size of either of the 2 models currently available: the Mobius (Apple Medical Corporation, Marlboro, Miss) and the Protractor (Weck Closure Systems, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Introduce a hand through the laparotomy incision and evaluate the pelvis to ensure that no significant adhesions are present that may interfere with swift placement of the inner ring. If significant adhesions are found, use traditional metal retractors instead.

Squeeze the inner ring and insert it into the abdominal cavity toward the patient’s head, allowing the device to spring open against the parietal peritoneum (FIGURE 2A). Apply upper traction and elevate the superior edge of the abdominal incision to facilitate placement. Perform a digital check to ensure no tissue is trapped between the inner ring and the abdominal wall.

Hold up the outer ring, then roll the plastic sleeve until the ring completely inverts (FIGURE 2B). Repeat the process until the top ring is snug against the patient’s skin.

Advantages of the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor include atraumatic retraction; incision protection; and adjustable height, making it ideal for obese patients.

FIGURE 2A Place the abdominal retractor

FIGURE 2B Place the abdominal retractor

Transverse hysterotomy in lower uterine segment

Make a transverse 2-cm uterine incision with a scalpel, approximately 1 cm above the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (identify this using gentle digital pressure to elevate the uterus) (FIGURE 3A).

Traditional bladder dissection is eliminated. We have found that when an adequate transverse hysterotomy is performed, a bladder flap is not required.1-3 In a recent randomized trial, Hohlagschwandtner et al9 confirmed our findings that bladder-flap omission was associated with reduced operative time and incision-delivery interval, decreased blood loss, and less need for postoperative analgesics.

An additional advantage of this omission: We can avoid making the uterine incision too low—especially when the cervix is fully dilated. Further, making the hysterotomy (uterine serosa and myometrium together) slightly above the vesicouterine peritoneal fold without bladder flap dissection frees the loose connective tissue between the uterus and the urinary bladder, allowing the spontaneous descent of the bladder.

Digitally extend the transverse uterine incision. We extend the initial incision not laterally but, instead, vertically (FIGURE 3B). The vertical digital traction on the initial transverse uterine incision creates a transverse dissociation of the horizontal myometrium fibers; this results in a transverse extension of the original incision.

This modification prevents unintended and uncontrolled lateral extensions of the incision that may lacerate the uterine vessels.10 It also prevents the uterine incision from becoming an inverted “U” and the undesirable accumulation of myometrium fibers at the ends of the incision. Such incisions usually do not reapproximate well during hysterotomy closure and may lead to sacculation-type defects.11

FIGURE 3A Use a standard hysterotomy in the lower uterine segment

FIGURE 3B Use a standard hysterotomy in the lower uterine segment

Delivering the fetus

For vertex presentations, place your hand into the uterine cavity between the lower edge of the hysterotomy and fetal head. While applying transabdominal fundal pressure, lift the head with your fingers and deliver it through the incision (FIGURE 4A).

The self-retaining retractor facilitates delivery of the fetal head by creating a rigid border around the abdominal incision. The back of the surgeon’s hand that is in the uterine cavity achieves better leverage, as it now rests on a rigid plane on the inferior part of the incision rather than on the back hand and the softer and pliable wound edge of the standard abdominal incision.

Vacuum-assistance. When delivery of the fetal head proves difficult, we use the soft vacuum cup, which avoids unnecessary intrauterine manipulation that may result in fetal or maternal trauma (FIGURE 4B).12

Breech extraction or transverse lie delivery is performed using standard extraction maneuvers (FIGURE 4C).13 We have found no need to perform T or J vertical extensions of the low transverse uterine incision, even in cases of a poorly developed lower uterine segment, abnormal presentation, or prematurity.

FIGURE 4A Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4B Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4C Deliver the fetal head

Uterine incision: 1-layer, in situ close

Remove the placenta only after it separates spontaneously—this greatly reduces blood loss compared with immediate manual placental delivery or umbilical-cord traction. Manually deliver the placenta only if it has not separated spontaneously after 5 minutes. Avoid routine manual clean-out of the uterine cavity if the placenta is completely delivered.1-3,14

Dilate the cervix to facilitate lochial discharge, when necessary.

Decrease uterine bleeding by massaging the uterus and administering diluted oxytocin.

Close the uterine incision in situ. Disadvantages of routine uterine exteriorization include discomfort and vomiting resulting from traction, exposure of the fallopian tubes to unnecessary trauma, increased risk of infection, possible rupture of the uteroovarian veins, and pulmonary embolism.

Exteriorization may also increase the risk of adhesion formation by exposing the uterine serosa to the abrasive effects of drying or microscopic abrasion if sponges are used to hold the uterus in place.1,14-17

Use a single-layer closure with a running suture of polyglycolic acid to close the uterine incision (FIGURE 5A). If needed, use atraumatic clamps to grasp the edges of the hysterotomy to facilitate visualization and closure.

Begin suturing at a point just beyond one end of the incision, continuing to the opposite side. Be sure to penetrate the full thickness of the myometrium and avoid incorporating the decidua in the suture line. After the uterine closure, use individual figure-of-8 sutures to control areas of persistent bleeding.

Compared with 2-layer closures, single-layer closure of a low transverse incision is associated with reduced operating time, improved hemostasis, and less tissue disruption; introduces less foreign material into the surgical site; reduces the need for postoperative analgesia; and potentially reduces infectious morbidity. A trial of labor after a cesarean section with 1-layer closure appears safe.18-22

We do not close the vesicouterine fold and parietal peritoneum (FIGURE 5B) or reapproximate the rectus muscles. It has been shown that a new peritoneal layer is formed within days of the original incision closure.

Leaving the peritoneum open leads to no increased postoperative complications, nor obvious differences in wound healing, wound dehiscence, or incidence of postoperative adhesions. Compared to women without peritoneal closure, those with peritoneal closure require a longer operative time, greater amounts of post-operative narcotics for postoperative pain, a greater need for bowel stimulants, and a longer postoperative hospitalization.23

In 1995, we performed laparoscopy for gynecologic conditions in 23 patients and repeat cesarean in 10 patients who had undergone our technique (with visceral and parietal peritoneum left open).2 We found no adhesions and a normal peritoneal lining in all cases.

In 1 subgroup, peritoneal closure is strongly recommended: cases in which 1 or both rectus muscles have been transected to increase surgical exposure. Extremely thick fibromuscular adhesions between the low anterior surface of the uterus and the under-surface of the rectus musculature may develop if the parietal peritoneum is not closed.

FIGURE 5A Close the incisions

FIGURE 5B Close the incisions

Abdominal closure

Close the rectus fascia with a continuous nonlocking 0 suture after the rectus muscles fall into place. Place entry and exit sites at 1-cm intervals, 1.5 cm beyond the wound edges—this minimizes the risk of sutures pulling through fascia. Interrupted sutures offer no greater tensile strength than continuous suturing.24 Tight, continuous suturing can lead to tissue ischemia, which may weaken the sutured fascia, and thus should be avoided.

The subcutaneous layer is not closed separately. One exception is obese patients with at least 2 cm of thick subcutaneous tissue. Thickness of subcutaneous tissue appears to be a significant risk factor for wound infection after cesarean section.25

In patients with thick subcutaneous tissue, you can reduce tension on the skin edges and the risk of subcutaneous infection, seroma formation, and wound disruption by placing interrupted 3-0 absorbable synthetic sutures to eliminate dead space.26-28 We have found no need to place Penrose drains or closed drainage systems in the subcutaneous layer.29-31

Close the skin using a subcuticular continuous absorbable 4-0 suture or, alternatively, metal staples, which are removed 4 days after surgery (FIGURE 5C).

FIGURE 5C Close the incisions

Prompt postoperative recovery

The patient may drink fluids in the recovery room, can resume a regular solid food diet within 4 hours after surgery, and may resume mobility as soon as anesthesia wears off.

Early breast-feeding is also allowed in the recovery room. In our experience, this has not been associated with complications, has been highly appreciated by the patients, and has led to earlier hospital discharge.

Control pain with meperidine (50–75 mg) or morphine (10 mg) parenterally every 3 to 4 hours. Other options include oxycodone and acetaminophen, oxycodone and aspirin, and ibuprofen.

Patients are usually discharged 48 to 72 hours following surgery.

Our experience: The numbers

Using this updated system, we have successfully completed 300 consecutive cesarean sections (210 primary, 90 repeat).

The average operating time was 19 minutes; average blood loss, 405 mL.

There was no postoperative febrile morbidity, wound infection, wound disruption, or wound hematoma.Only 3 patients developed superficial wound seromas, which were easily resolved. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications.

We attribute the absence of wound infection to routine prophylactic antibiotics; supplemental perioperative oxygen; maintenance of normothermia; use of an electrocautery knife to create rapid hemostatic division of subcutaneous fat and anterior rectus fascia; a simplified abdominal wall opening; and placement of a self-retaining atraumatic retractor.10,32-36

Additional surgical procedures (tubal sterilization, myomectomy, appendectomy, and adhesiolysis) did not alter the recovery period, and all patients were able to get out of bed, shower, breast-feed, and care for their infants within 8 hours of surgery.

No infant complications related to the cesarean procedure occurred.

Patients were discharged from the hospital within 72 hours.

A prospective comparison study demonstrated that the original Pelosi-type of cesarean delivery was faster to perform, more cost-effective, and resulted in less maternal morbidity than the traditional cesarean technique.3

Dr. Pelosi II is a consultant for Apple Medical Corporation. Dr. Pelosi III reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Pelosi MA, Ortega I. Cesarean section: Pelosi simplified technique. Rev Chil Obstet Gynecol. 1994;59:372-377.

2. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Simplified cesarean section. Contemp OB/GYN. 1995;40:89-100.

3. Wood RM, Simon H, Oz AU. Pelosi-type vs traditional cesarean delivery: a prospective comparison. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:788-795.

4. Finan MA, Mastrogiannis DS, Spellacy WN. The “Allis” test for easy cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:772-775.

5. Ayers IW, Morley GW. Surgical incision for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:706-712.

6. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Self-retaining abdominal retractor for minilaparotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:775-778.

7. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: Effective alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. OBG Manag. April 2003;16-33.

8. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. A novel minilaparotomy approach for large ovarian cysts. OBG Manag. February 2004:;17-30.

9. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, et al. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1089-1092.

10. Ferrari A, Frigerio L, Origoni M, et al. Modified Stark procedure for cesarean section. J Pelv Surg. 1996;2:239-244.

11. Field CS. Surgical techniques for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Amer. 1988;15:657-672.

12. Pelosi MA, Apuzzio J. Use of the soft, silicone obstetric vacuum cup for delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:289-292.

13. Pelosi MA, Apuzzio J, Fricchione D, et al. The intra-abdominal version technique for delivery of transverse lie by low segment cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:1009-1012.

14. Magann EF, Dodson MK, Albert JR, et al. Blood loss at the time of cesarean section by method of placental removal and exteriorization versus in situ repair of the uterine incision. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:389-392.

15. Stock RJ, Shelton H. Fatal pulmonary embolism occurring 2 hours after exteriorization of the uterus for repair following cesareans section. Milit Med. 1985;150:549-550.

16. Hershey DW, Quilligan EJ. Extra-abdominal uterine exteriorization at cesarean section. Obstet Genecol. 1978;52:189-191.

17. Wahab MA, Karantzis P, Eccersley PS, et al. A randomized, controlled study of uterine exteriorization and repair at cesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;106:913-916.

18. Hauth JC, Owen J, Davis RO. Transverse uterine incision closure: one versus two layers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1108-1111.

19. Ohel G, Younis JS, Lang N, et al. Double-layer closure of uterine incision with visceral and parietal peritoneal closure: Are they obligatory steps of routine cesarean sections? J Matern Fetal Med. 1996;5:366-369.

20. Tucker JM, Hauth JC, Hodgkins P, et al. Trial of labor after a one- or two-layer closure of a low transverse uterine incision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:545-546.

21. Chapman SJ, Owen J, Hauth JC. One- versus two-layer closure of a low transverse cesarean: the next pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:16-18.

22. Jelsema RD, Wittinger JA, Vander Kolk KJ. Continuous, nonlocking, single-layer repair of the low transverse uterine incision. J Reprod Med. 1993;38:393-396.

23. Tulandi T, Al-Jaroudi D. Nonclosure of peritoneum: a reappraisal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:609-612.

24. Fagniez PL, Hay JM, Lacaine F. Abdominal midline incision closure. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1351-1355.

25. Vermillion ST, Lamoutte C, Soper DE, et al. Wound infection after cesarean: effect of subcutaneous tissue thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:923-926.

26. Naumann RW, Hauth JC, Owen J, et al. Subcutaneous tissue approximation in relation to wound disruption after cesarean delivery in obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:412-416.

27. Cetin A, Cetin M. Superficial wound disruption after cesarean delivery: effect of the depth and closure of subcutaneous tissue. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;57:17-21.

28. Del Valle GO, Combs P, Qualls C, et al. Does closure of Camper fascia reduce the incidence of post-cesarean superficial wound disruption? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1013-1016.

29. Loong RL, Rogers MS, Chang AM. A controlled trial of wound drainage at cesarean section. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;28:266-269.

30. Saunders NJ, Barclay C. Closed suction wound drainage and lower-segment cesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95:1060-1062.

31. Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Rodts-Palenik S, Bufkin L, Martin JN, Jr, Morrison JC. Subcutaneous stitch closure versus subcutaneous drain to prevent wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1119-1123.

32. Stark M, Finkel AR. Comparison between the Joel-Cohen and Pfannenstiel incisions in cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;53:121-122.

33. Joel-Cohen S. Abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy. New techniques based on time and motion studies. London, England: William Heinemann Medical Books; 1972.

34. Hemsell DL, Hemsell PG, Nobles B, et al. Abdominal wound problems after hysterectomy with electrocautery versus scalpel subcutaneous incision. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1993;1:27-30.

35. Johnson CD, Serpell JW. Wound infection after abdominal incision with scalpel or diathermy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:626-629.

36. Hussain SA, Hussain S. Incisions with knife or diathermy and postoperative pain. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1179-1182.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians-gynecologists. No. 43, May, 2003. Management of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1039-1047.

38. Greif R, Akca O, Hurn E-P, et al. Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:161-167.

39. Sorensen LT, Karlsmark T, Gottrup F. Abstinence from smoking reduces incisional wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238:1-5.

40. Sessler DI, Akca O. Preventing surgical site infections without drugs. Contemp OB/GYN. 2004;49:78-87.

41. Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection and shorten hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209-1215.

1. Pelosi MA, Ortega I. Cesarean section: Pelosi simplified technique. Rev Chil Obstet Gynecol. 1994;59:372-377.

2. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Simplified cesarean section. Contemp OB/GYN. 1995;40:89-100.

3. Wood RM, Simon H, Oz AU. Pelosi-type vs traditional cesarean delivery: a prospective comparison. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:788-795.

4. Finan MA, Mastrogiannis DS, Spellacy WN. The “Allis” test for easy cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:772-775.

5. Ayers IW, Morley GW. Surgical incision for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:706-712.

6. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Self-retaining abdominal retractor for minilaparotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:775-778.

7. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: Effective alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. OBG Manag. April 2003;16-33.

8. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. A novel minilaparotomy approach for large ovarian cysts. OBG Manag. February 2004:;17-30.

9. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, et al. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1089-1092.

10. Ferrari A, Frigerio L, Origoni M, et al. Modified Stark procedure for cesarean section. J Pelv Surg. 1996;2:239-244.

11. Field CS. Surgical techniques for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Amer. 1988;15:657-672.

12. Pelosi MA, Apuzzio J. Use of the soft, silicone obstetric vacuum cup for delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:289-292.

13. Pelosi MA, Apuzzio J, Fricchione D, et al. The intra-abdominal version technique for delivery of transverse lie by low segment cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:1009-1012.

14. Magann EF, Dodson MK, Albert JR, et al. Blood loss at the time of cesarean section by method of placental removal and exteriorization versus in situ repair of the uterine incision. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:389-392.

15. Stock RJ, Shelton H. Fatal pulmonary embolism occurring 2 hours after exteriorization of the uterus for repair following cesareans section. Milit Med. 1985;150:549-550.

16. Hershey DW, Quilligan EJ. Extra-abdominal uterine exteriorization at cesarean section. Obstet Genecol. 1978;52:189-191.

17. Wahab MA, Karantzis P, Eccersley PS, et al. A randomized, controlled study of uterine exteriorization and repair at cesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;106:913-916.

18. Hauth JC, Owen J, Davis RO. Transverse uterine incision closure: one versus two layers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1108-1111.

19. Ohel G, Younis JS, Lang N, et al. Double-layer closure of uterine incision with visceral and parietal peritoneal closure: Are they obligatory steps of routine cesarean sections? J Matern Fetal Med. 1996;5:366-369.

20. Tucker JM, Hauth JC, Hodgkins P, et al. Trial of labor after a one- or two-layer closure of a low transverse uterine incision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:545-546.

21. Chapman SJ, Owen J, Hauth JC. One- versus two-layer closure of a low transverse cesarean: the next pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:16-18.

22. Jelsema RD, Wittinger JA, Vander Kolk KJ. Continuous, nonlocking, single-layer repair of the low transverse uterine incision. J Reprod Med. 1993;38:393-396.

23. Tulandi T, Al-Jaroudi D. Nonclosure of peritoneum: a reappraisal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:609-612.

24. Fagniez PL, Hay JM, Lacaine F. Abdominal midline incision closure. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1351-1355.

25. Vermillion ST, Lamoutte C, Soper DE, et al. Wound infection after cesarean: effect of subcutaneous tissue thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:923-926.

26. Naumann RW, Hauth JC, Owen J, et al. Subcutaneous tissue approximation in relation to wound disruption after cesarean delivery in obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:412-416.

27. Cetin A, Cetin M. Superficial wound disruption after cesarean delivery: effect of the depth and closure of subcutaneous tissue. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;57:17-21.

28. Del Valle GO, Combs P, Qualls C, et al. Does closure of Camper fascia reduce the incidence of post-cesarean superficial wound disruption? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1013-1016.

29. Loong RL, Rogers MS, Chang AM. A controlled trial of wound drainage at cesarean section. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;28:266-269.

30. Saunders NJ, Barclay C. Closed suction wound drainage and lower-segment cesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95:1060-1062.

31. Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Rodts-Palenik S, Bufkin L, Martin JN, Jr, Morrison JC. Subcutaneous stitch closure versus subcutaneous drain to prevent wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1119-1123.

32. Stark M, Finkel AR. Comparison between the Joel-Cohen and Pfannenstiel incisions in cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;53:121-122.

33. Joel-Cohen S. Abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy. New techniques based on time and motion studies. London, England: William Heinemann Medical Books; 1972.

34. Hemsell DL, Hemsell PG, Nobles B, et al. Abdominal wound problems after hysterectomy with electrocautery versus scalpel subcutaneous incision. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1993;1:27-30.

35. Johnson CD, Serpell JW. Wound infection after abdominal incision with scalpel or diathermy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:626-629.

36. Hussain SA, Hussain S. Incisions with knife or diathermy and postoperative pain. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1179-1182.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians-gynecologists. No. 43, May, 2003. Management of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1039-1047.

38. Greif R, Akca O, Hurn E-P, et al. Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:161-167.

39. Sorensen LT, Karlsmark T, Gottrup F. Abstinence from smoking reduces incisional wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238:1-5.

40. Sessler DI, Akca O. Preventing surgical site infections without drugs. Contemp OB/GYN. 2004;49:78-87.

41. Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection and shorten hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209-1215.

A novel minilaparotomy approach for large ovarian cysts

- Make a cruciate incision by incising the skin transversely and the anterior rectus fascia vertically.

- Insert a soft, sleeved, self-retaining retractor.

- Using a surgical adhesive, glue a large plastic wound dressing to the surface of the cyst to prevent leakage of contents into the abdominal cavity.

- Aspirate the cyst until it collapses and can be delivered, with the ovary, through the abdominal incision.

- After performing an extracorporeal cystectomy and/or adnexectomy, return the repaired ovary to the abdominal cavity.

Although laparotomy is still considered the standard for ovarian cyst removal, over the past 15 years minimally invasive surgery has gained wider acceptance in cases where preoperative assessment suggests an adnexal mass is benign.

Unfortunately, minimally invasive management of a large ovarian cyst (greater than 10 cm) is particularly challenging for several reasons:

- The cyst can rupture and spill its contents into the peritoneum,

- the cyst’s size limits the surgical field, and

- an unexpected malignancy may be revealed.

An innovative minilaparotomy technique for the removal of benign ovarian cysts offers the advantages of laparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted procedures while bypassing the major disadvantages: the necessity for specialized and expensive equipment, lengthy operative time, and long learning curves.1 (The minimally invasive procedures currently available for the treatment of ovarian cysts include laparoscopic cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted minilaparotomy cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal cystectomy, combined percutaneous ultrasound cyst aspiration and laparoscopic cystectomy, transvaginal cystectomy, and the traditional minilaparotomy cystectomy.2-10)

The procedure is faster, less expensive, carries fewer potential risks than traditional alternatives, and offers these advantages:

- can be performed under regional anesthesia

- relies on standard open techniques

- uses inexpensive instrumentation

- is easy to learn

- can be used for very large cysts

- eliminates the risk of intraperitoneal spillage of cyst contents

- offers similar postoperative convalescence and mean time to return to work as laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted management of large ovarian cysts

General Ob/Gyns—not gynecologic oncologists—perform most surgeries on patients with adnexal masses, since ovarian cancer is relatively uncommon in the absence of preoperative risk factors for malignancy. Our approach offers an appealing option to Ob/Gyns reluctant to abandon routine traditional laparotomy for such ovarian cysts.

Selecting the right patient

Adequate preoperative assessment diminishes the risk of unexpected malignancy in a patient undergoing surgery for an ovarian mass to less than 1%.4 At this time, the combination of menopausal status, cancer antigen (CA) 125 level, physical examination, and ultrasound is the best strategy for evaluating the patient with an ovarian cyst.11

Signs of malignancy. Ultrasound features that suggest malignancy include irregular borders, thick septa, solid areas, internal and external excrescences, matted bowel, and ascites. Benign cysts, on the other hand, are usually unilateral and have regular borders, thin septa, no solid areas, and no internal excrescences.4 The measurement of blood flow within the mass by color Doppler may improve the accuracy of ultrasound in differentiating benign from malignant cysts.4,12

On physical examination, an adnexal mass that is fixed, irregular, or solid also suggests a neoplasm. An elevated CA 125 combined with a complex adnexal mass is likely to be associated with malignancy. The test is even more specific in postmenopausal women with adnexal masses.4,12

However, plasma levels of CA 125 also can be elevated in several benign gynecologic conditions such as endometriosis, simple ovarian cysts, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, fibroids, and in physiologic conditions such as menstruation and pregnancy.13

Anticipate the need to convert to laparotomy. Every patient’s surgical consent should include a possible conversion to laparotomy. To avoid incomplete surgical treatment and significant delays in proper therapy, a gynecologic surgeon experienced in the management of ovarian cancer should be readily available, in the event an unexpected malignancy is encountered. Ideally, the staging surgery and definite treatment should be performed at the time of initial minilaparotomy. Comprehensive surgical staging and treatment include thorough exploration of the pelvis and abdomen, omentectomy, pelvic and paraaortic lymph node sampling, multiple peritoneal biopsies and washings, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and debulking, when indicated.

Prepare for surgery with position, incision, and retraction

Before beginning, it is crucial to correctly position the patient, make the appropriate incision, and insert the right retractor.1

Position. After administering regional or general anesthesia, place the patient in a modified lithotomy, as for laparoscopic surgery. Tuck the arms alongside the torso and place the legs in boot stirrups. Avoid hip flexion and allow adequate thigh abduction to expose the vagina. Perform a careful pelvic examination to determine the size and mobility of the adnexal mass.

When properly placed, this retractor creates an atraumatic, circular area of self-retraction, enabling superior exposure

Place an indwelling transurethral catheter, and pass a sturdy, hinged uterine manipulator such as the Pelosi Uterine Manipulator (Apple Medical Corp, Marlboro, Mass) transcervically into the uterine cavity (FIGURE 1).