User login

- Make a cruciate incision by incising the skin transversely and the anterior rectus fascia vertically.

- Insert a soft, sleeved, self-retaining retractor.

- Using a surgical adhesive, glue a large plastic wound dressing to the surface of the cyst to prevent leakage of contents into the abdominal cavity.

- Aspirate the cyst until it collapses and can be delivered, with the ovary, through the abdominal incision.

- After performing an extracorporeal cystectomy and/or adnexectomy, return the repaired ovary to the abdominal cavity.

Although laparotomy is still considered the standard for ovarian cyst removal, over the past 15 years minimally invasive surgery has gained wider acceptance in cases where preoperative assessment suggests an adnexal mass is benign.

Unfortunately, minimally invasive management of a large ovarian cyst (greater than 10 cm) is particularly challenging for several reasons:

- The cyst can rupture and spill its contents into the peritoneum,

- the cyst’s size limits the surgical field, and

- an unexpected malignancy may be revealed.

An innovative minilaparotomy technique for the removal of benign ovarian cysts offers the advantages of laparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted procedures while bypassing the major disadvantages: the necessity for specialized and expensive equipment, lengthy operative time, and long learning curves.1 (The minimally invasive procedures currently available for the treatment of ovarian cysts include laparoscopic cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted minilaparotomy cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal cystectomy, combined percutaneous ultrasound cyst aspiration and laparoscopic cystectomy, transvaginal cystectomy, and the traditional minilaparotomy cystectomy.2-10)

The procedure is faster, less expensive, carries fewer potential risks than traditional alternatives, and offers these advantages:

- can be performed under regional anesthesia

- relies on standard open techniques

- uses inexpensive instrumentation

- is easy to learn

- can be used for very large cysts

- eliminates the risk of intraperitoneal spillage of cyst contents

- offers similar postoperative convalescence and mean time to return to work as laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted management of large ovarian cysts

General Ob/Gyns—not gynecologic oncologists—perform most surgeries on patients with adnexal masses, since ovarian cancer is relatively uncommon in the absence of preoperative risk factors for malignancy. Our approach offers an appealing option to Ob/Gyns reluctant to abandon routine traditional laparotomy for such ovarian cysts.

Selecting the right patient

Adequate preoperative assessment diminishes the risk of unexpected malignancy in a patient undergoing surgery for an ovarian mass to less than 1%.4 At this time, the combination of menopausal status, cancer antigen (CA) 125 level, physical examination, and ultrasound is the best strategy for evaluating the patient with an ovarian cyst.11

Signs of malignancy. Ultrasound features that suggest malignancy include irregular borders, thick septa, solid areas, internal and external excrescences, matted bowel, and ascites. Benign cysts, on the other hand, are usually unilateral and have regular borders, thin septa, no solid areas, and no internal excrescences.4 The measurement of blood flow within the mass by color Doppler may improve the accuracy of ultrasound in differentiating benign from malignant cysts.4,12

On physical examination, an adnexal mass that is fixed, irregular, or solid also suggests a neoplasm. An elevated CA 125 combined with a complex adnexal mass is likely to be associated with malignancy. The test is even more specific in postmenopausal women with adnexal masses.4,12

However, plasma levels of CA 125 also can be elevated in several benign gynecologic conditions such as endometriosis, simple ovarian cysts, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, fibroids, and in physiologic conditions such as menstruation and pregnancy.13

Anticipate the need to convert to laparotomy. Every patient’s surgical consent should include a possible conversion to laparotomy. To avoid incomplete surgical treatment and significant delays in proper therapy, a gynecologic surgeon experienced in the management of ovarian cancer should be readily available, in the event an unexpected malignancy is encountered. Ideally, the staging surgery and definite treatment should be performed at the time of initial minilaparotomy. Comprehensive surgical staging and treatment include thorough exploration of the pelvis and abdomen, omentectomy, pelvic and paraaortic lymph node sampling, multiple peritoneal biopsies and washings, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and debulking, when indicated.

Prepare for surgery with position, incision, and retraction

Before beginning, it is crucial to correctly position the patient, make the appropriate incision, and insert the right retractor.1

Position. After administering regional or general anesthesia, place the patient in a modified lithotomy, as for laparoscopic surgery. Tuck the arms alongside the torso and place the legs in boot stirrups. Avoid hip flexion and allow adequate thigh abduction to expose the vagina. Perform a careful pelvic examination to determine the size and mobility of the adnexal mass.

When properly placed, this retractor creates an atraumatic, circular area of self-retraction, enabling superior exposure

Place an indwelling transurethral catheter, and pass a sturdy, hinged uterine manipulator such as the Pelosi Uterine Manipulator (Apple Medical Corp, Marlboro, Mass) transcervically into the uterine cavity (FIGURE 1).

The cruciate incision. With a conventional scalpel make a small suprapubic transverse incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue (FIGURE 2). After clearing subcutaneous fat from the midline, incise the rectus fascia and the peritoneum in a vertical direction.

A vertical skin incision can be selected if the preoperative workup suggests a later extension of the original minilaparotomy incision may be required, or if there is a prior vertical incision.

Retraction. Use a soft sleeve-type self-retaining plastic retractor, such as Mobius (Apple Medical Corp) (FIGURE 3 ). When properly placed, this retractor creates an atraumatic, circular area of self-retraction, enabling superior exposure of the pelvis (FIGURE 4).

During surgery it may be necessary to adjust the outer ring if the sleeve loosens. Narrow Deaver or Richardson retractors, if required, provide additional retraction. The bowel may be gently packed, if necessary, but typically it is adequately displaced by the large ovarian cyst.

The atraumatic retraction provided by the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor minimizes the possibility of tissue trauma, nerve damage, bruising, and postoperative pain. At the same time, the continuous 360° retraction force on the incision maximizes surgical exposure, providing a significantly larger working area than conventional retractors. For example, when applied to a 6-cm incision, the self-retaining retractor creates a 28-cm2 exposed working area, compared with only 18 cm2 provided by a conventional 4-point metal retractor.

The adjustable height of the self-retaining retractor adapts to wounds of varying depth and works on virtually any tissue thickness—a feature that makes the device effective for obese patients. Further, by lining the abdominal incision, the retractor’s plastic sleeve protects the wound’s edges from contamination and potential implantation of malignant cells, making the device ideal for managing ovarian cysts.

FIGURE 1 Hinged uterine manipulator

The manipulator facilitates exposure of the cyst and contralateral adnexa, as well as uterine elevation/rotation.

FIGURE 2 Cruciate incision

Make a 2.5- to 5-cm suprapubic transverse skin incision. Using the Bovie device, incise the subcutaneous fat transversely along the full length of the skin incision down to the level of the anterior rectus fascia. Clear the subcutaneous fat from the midline superiorly and inferiorly to expose 5 to 6 cm of the rectus fascia in the vertical axis. Use blunt digital dissection to assist in mobilizing the subcutaneous fat. Incise the anterior rectus fascia vertically through the full length of the cleared area. Retract the rectus muscles from the midline to expose the underlying transversalis fascia and the peritoneum. Control small bleeding points with the Bovie device. Enter the peritoneum either digitally or with scissors above the bladder dome and extend the peritoneal incision to the full length of the fascial incision.

FIGURE 3 Self-retaining retractor

The retractor consists of a flexible plastic inner ring and a firmer outer ring connected by a soft plastic sleeve.

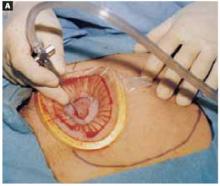

FIGURE 4360° retraction force

Squeeze the inner ring of the soft, sleeve-type, self-retaining retractor into the peritoneal cavity through the cruciate abdominal incision and allow it to spring open against the parietal peritoneum. Make a digital assessment to ensure that viscera is not trapped between the inner ring and the abdominal wall. Place the entire sleeve on traction by lifting the outer ring. Then roll the outer ring onto the sleeve, collecting excess length, until it sits firmly against the skin. The atraumatic retraction provided by the sleeve-type retractor maximizes exposure of the pelvis. Note how a portion of the large cyst is clearly seen through the atraumatic, circular area of retraction.

Cyst assessment

Visually and digitally inspect the cyst and carefully evaluate the uterus, pelvis, and contralateral adnexa. Determine the extent of adhesions and any unexpected pelvic pathology. When needed, use traditional small retractors or gentle packing to gain additional exposure. If the cystic mass appears suspicious (internal and external excrescences on the cyst, ovaries, or peritoneal surfaces, or ascites), obtain pelvic washings with a suction-irrigation cannula, send the fluid for cytologic examination, and convert the minilaparotomy to a standard exploratory laparotomy. Extensive adhesions to the bowel, broad ligament, or pelvic sidewall and unexpected extensive endometriosis may also require a conversion to standard laparotomy.

Reduce cyst size by decompression

Simple aspiration is inadvisable. To remove a large ovarian cyst using the Pelosi minilaparotomy, reduce the size of the cyst to permit safe and effective mobilization and resection through the small abdominal incision. Simple aspiration of the cyst, with its potential for spilling the contents, is not a wise strategy for several reasons. First, many ovarian cysts contain functional epithelium with a high recurrence rate (8% to 67%). Second, studies show that 10% to 66% of ovarian cyst fluid aspirates initially diagnosed as benign actually are malignant. Further, relying on negative cytology from the aspirate of an ovarian cyst without tissue biopsy may delay appropriate surgery, and the puncture of an unexpected malignant cyst may seed the peritoneal cavity and possibly worsen the patient’s prognosis.11,12

This technique, suitable for all ovarian cysts, makes it possible to aspirate a large cyst without leakage.

Whether spillage of cancer cells actually worsens the prognosis of a patient with a neoplastic cyst remains controversial because of conflicting study results. Nonetheless, the possibility of intraperitoneal dissemination of neoplastic cells from a ruptured cyst cannot be considered innocuous, and the potential negative effect on a patient’s prognosis should not be ignored.14 Make every attempt, therefore, to avoid rupturing the cyst and spilling the fluid into the peritoneal cavity.

A shared flaw plagues aspiration devices. Different devices are available for intraoperative cyst aspiration during laparoscopic, transvaginal, or laparotomy approaches.3,4,6 In addition to long needles, drainage trocars, suction cannulas, and suprapubic bladder catheters, special aspiration instruments have been developed.15 They include a metal vacuum system with an aspirator trocar that seals the surface of the cyst, and a catheter system that pinches the punctured cyst wall between double balloons to prevent spillage.16 In addition, several commercial bags are available to prevent intraperitoneal spillage during removal of ovarian cysts.

All these devices have a universal flaw, however: After a thin-walled cyst initially is punctured, none of these products can prevent the spontaneous dehiscence of the cyst and the resulting spillage of its contents into the abdominal cavity. Vacuum systems work well for large cysts with smooth, round surfaces, but in those with irregular surfaces, both application and maintaining the seal are difficult.17 Fortunately, our technique makes it possible to aspirate a large ovarian cyst without leakage, and the method is suitable for all ovarian cysts regardless of surface type or wall thickness.

Glue the dressing to the cyst to capture leakage. Using a gauze pad, carefully dry the area of the ovarian cyst that is visible through the self-retaining retractor. Then generously spread sterile surgical glue such as Dermabond (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) on the cyst wall surface (FIGURE 5A). Dermabond is the commercial name for 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, a sterile skin adhesive used as an alternative to stitches to close the edges of small wounds. It is similar to commercial adhesives such as Super Glue and Krazy Glue.

Remove the paper cover of a transparent plastic surgical dressing and place the adhesive side directly onto the glued cyst surface until you are sure the adhesive is completely fixed (FIGURES 5B AND 5C). The 35 cm x 35 cm Steri-Drape or the transparent Tegaderm (both from 3M Health Care, St. Paul, Minn) dressing is effective. A standard nonadhesive plastic dressing or a sterile plastic bag also can be used, as long as the free edges extend beyond the outer rim of the self-retaining retractor.

With a needle aspirator, pierce the cyst through the glued plastic dressing and carefully aspirate the fluid (FIGURES 6A AND 6B). Any leakage is trapped inside the plastic dressing rather than the abdominal cavity. Continue the aspiration until the collapsed cyst and ovary can be gradually delivered through the abdominal incision (FIGURE 6C). Note that the selfretaining retractor also protects the abdominal incision from potential contamination and implantation of neoplastic cells.

Once the cyst and ovary are extracted, you can readily perform an extracorporeal cystectomy, after which the repaired ovary is returned to the abdominal cavity. Be careful to avoid letting any fluid flow back into the peritoneal cavity during cyst removal. When indicated, an extracorporeal adnexectomy can readily be performed.

The presence of oily material or hairs in the aspirated fluid and on the needle tip readily identifies a dermoid cyst.

Dermoid cysts require extra care. Preventing intraperitoneal spillage is especially important when removing a large dermoid cyst, to avoid the possibility of chemical peritonitis, dense adhesions, and fistulas. The presence of oily material or hairs in the aspirated fluid and on the needle tip readily identifies a dermoid cyst. Quite frequently, a large-diameter suction cannula is required to remove the waxy contents. If the dermoid cyst is very large, aspiration alone will not empty it entirely. Complete emptying is not necessary, however. The primary goal of aspiration is to reduce the size and tension of the cyst to permit delivery through the abdominal incision.

Closing the cruciate incision is quicker and requires less exposure than a scaled-down Pfannenstiel’s incision.

Before concluding the procedure, irrigate the peritoneal cavity to remove any remnants of cyst contents that may have spilled—especially important with a dermoid cyst. Perform any additional indicated procedures through the minilaparotomy incision, such as a contralateral ovarian cystectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, or hysterectomy. After the surgery is completed, remove the self-retaining retractor by hooking a finger through the bottom ring and pulling it gently out of the incision. Closing the cruciate incision is quicker and requires less exposure to complete than a scaled-down Pfannenstiel’s incision. Apply a vertical pressure dressing over the incision to prevent postoperative wound hematoma or seroma formation. Remove the dressing 24 hours later.

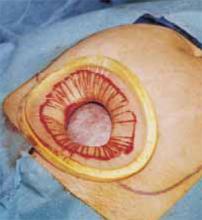

FIGURE 5A ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

After drying the surface of the cyst, apply sterile surgical glue to the cyst wall (2 to 3 ampules are usually required to cover the cyst surface).

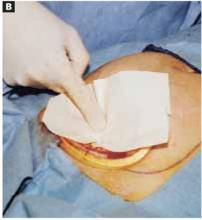

FIGURE 5B ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

Apply the adhesive side of a clear plastic wound dressing directly onto the cyst’s surface, making sure that the dressing is large enough to fully cover the self-retaining retractor. Using either a piece of folded gauze or your fingers, press the plastic dressing against the adhesive-coated cyst for about 3 to 5 minutes until the adhesive is completely fixed.

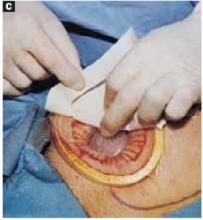

FIGURE 5C ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

Remove the paper cover of the wound dressing.

FIGURE 6A Aspirating the cyst

Pierce the dressing and carefully aspirate the fluid until the cyst is partially collapsed.

FIGURE 6B Aspirating the cyst

Place atraumatic clamps on the cyst wall to further control drainage. Any leakage is trapped inside the plastic dressing rather than draining into the abdominal cavity.

FIGURE 6C Aspirating the cyst

Continue the aspiration until the collapsed cyst and ovary can be delivered gradually through the abdominal incision, after detaching the adhesive plastic dressing from the edges of the self-retaining retractor. The portion of the plastic sleeve that is glued to the cyst surface remains attached to the cyst until the cyst is extracted. Following extraction, perform an extracorporeal cystectomy and return the repaired ovary to the abdominal cavity.

Good results

Using our approach, we have treated 38 patients with ovarian cysts of diameters greater than 20 cm thought to be benign by preoperative workup (FIGURE 7). We encountered no malignancies. All surgeries were successfully completed without laparoscopy or conversion to traditional laparotomy and with good cosmesis (FIGURE 8).

Other procedures performed in some of these patients using the same technique included contralateral cystectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, subtotal and total hysterectomy, adhesiolysis, and appendectomy. We encountered no intraoperative or postoperative complications. Operating times ranged from 18 to 65 minutes. All patients were discharged home within 36 hours and returned to work in a mean of 12 days. Pathology findings of the ovarian cysts included endometrioma, dermoid cyst, serous cystadenoma, and mucinous cystadenoma.

FIGURE 7 Effective for large cysts

Following removal, the collapsed cyst was refilled with 1,300 mL of normal saline to demonstrate its actual size.

FIGURE 8 Good cosmetic results

Cosmetic appearance of the small cruciate abdominal incision 10 days after surgery.Dr. Pelosi II reports that he is a consultant for Apple Medical Corporation. Dr. Pelosi III reports no affiliations or financial arrangements with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: Effective alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. OBG Management. 2003;15(4):16-33.

2. Havrilesky LJ, Peterson BL, Dryden DK, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes in the laparoscopic management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:243-251.

3. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Laparoscopic removal of a 103 pound ovarian tumor. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3:413-417.

4. Eltabbaku GH. Laparoscopic management of ovarian cysts. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2003;48(8):37-50.

5. Ou C, Liu Y, Zabriskie V, et al. Alternate method for laparoscopic management of adnexal masses greater than 10 cm in diameter. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2001;11:125-132.

6. Jeong E, Kim H, Ahn C, et al. Successful laparoscopic removal of huge ovarian cysts. J Am Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4:609-614.

7. Nagele F, Magos AL. Combined ultrasonographically guided drainage and laparoscopic excision of a large ovarian cyst. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1377-1378.

8. Sheth S. Adnexal pathology. In: Sheth S, Studd J, eds. Vaginal Hysterectomy. London, England: Martin Dunitz; 2002;165-178.

9. Flynn MK, Niloff JM. Outpatient minilaparotomy for ovarian cysts. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:399-404.

10. Benedetti P, Panicci P, Maneschi F, et al. Surgery by minilaparotomy in benign gynecological disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:456-459.

11. Jansen FW, Tanahotoe S, Veselie M, et al. Laparoscopic aspiration of ovarian cysts: an unreliable technique in primary diagnosis of sonographically benign ovarian lesions. Gynecol Endosc. 1997;6:363-367.

12. Parker WH. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass in postmenopausal women. J Gynecol Tech. 1995;1:3-5.

13. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Mais V, et al. Prelaparoscopic assessment of ovarian cysts in reproductive-age women. Gynecol Endosc. 1997;6:157-167.

14. Fowler JM, Carter JR. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass in postmenopausal women. J Gynecol Tech. 1995;1:7-10.

15. McCormick JB, Fitzgibbons JP. Instrument for aspiration of large ovarian cysts. Obstet Gynecol. 1967;29:869-870.

16. Yamada T, Okamoto Y, Kasematsu H. Use of the Sand balloon catheter for the laparoscopic surgery of benign ovarian cysts. Gynecol Endosc. 1999;9:51-54.

17. Shozu M, Segawa T, Sumitani H, et al. Leak-proof puncture of ovarian cysts: instant mounting of plastic bag using cyanoacrylate adhesive. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:1007-1010.

- Make a cruciate incision by incising the skin transversely and the anterior rectus fascia vertically.

- Insert a soft, sleeved, self-retaining retractor.

- Using a surgical adhesive, glue a large plastic wound dressing to the surface of the cyst to prevent leakage of contents into the abdominal cavity.

- Aspirate the cyst until it collapses and can be delivered, with the ovary, through the abdominal incision.

- After performing an extracorporeal cystectomy and/or adnexectomy, return the repaired ovary to the abdominal cavity.

Although laparotomy is still considered the standard for ovarian cyst removal, over the past 15 years minimally invasive surgery has gained wider acceptance in cases where preoperative assessment suggests an adnexal mass is benign.

Unfortunately, minimally invasive management of a large ovarian cyst (greater than 10 cm) is particularly challenging for several reasons:

- The cyst can rupture and spill its contents into the peritoneum,

- the cyst’s size limits the surgical field, and

- an unexpected malignancy may be revealed.

An innovative minilaparotomy technique for the removal of benign ovarian cysts offers the advantages of laparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted procedures while bypassing the major disadvantages: the necessity for specialized and expensive equipment, lengthy operative time, and long learning curves.1 (The minimally invasive procedures currently available for the treatment of ovarian cysts include laparoscopic cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted minilaparotomy cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal cystectomy, combined percutaneous ultrasound cyst aspiration and laparoscopic cystectomy, transvaginal cystectomy, and the traditional minilaparotomy cystectomy.2-10)

The procedure is faster, less expensive, carries fewer potential risks than traditional alternatives, and offers these advantages:

- can be performed under regional anesthesia

- relies on standard open techniques

- uses inexpensive instrumentation

- is easy to learn

- can be used for very large cysts

- eliminates the risk of intraperitoneal spillage of cyst contents

- offers similar postoperative convalescence and mean time to return to work as laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted management of large ovarian cysts

General Ob/Gyns—not gynecologic oncologists—perform most surgeries on patients with adnexal masses, since ovarian cancer is relatively uncommon in the absence of preoperative risk factors for malignancy. Our approach offers an appealing option to Ob/Gyns reluctant to abandon routine traditional laparotomy for such ovarian cysts.

Selecting the right patient

Adequate preoperative assessment diminishes the risk of unexpected malignancy in a patient undergoing surgery for an ovarian mass to less than 1%.4 At this time, the combination of menopausal status, cancer antigen (CA) 125 level, physical examination, and ultrasound is the best strategy for evaluating the patient with an ovarian cyst.11

Signs of malignancy. Ultrasound features that suggest malignancy include irregular borders, thick septa, solid areas, internal and external excrescences, matted bowel, and ascites. Benign cysts, on the other hand, are usually unilateral and have regular borders, thin septa, no solid areas, and no internal excrescences.4 The measurement of blood flow within the mass by color Doppler may improve the accuracy of ultrasound in differentiating benign from malignant cysts.4,12

On physical examination, an adnexal mass that is fixed, irregular, or solid also suggests a neoplasm. An elevated CA 125 combined with a complex adnexal mass is likely to be associated with malignancy. The test is even more specific in postmenopausal women with adnexal masses.4,12

However, plasma levels of CA 125 also can be elevated in several benign gynecologic conditions such as endometriosis, simple ovarian cysts, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, fibroids, and in physiologic conditions such as menstruation and pregnancy.13

Anticipate the need to convert to laparotomy. Every patient’s surgical consent should include a possible conversion to laparotomy. To avoid incomplete surgical treatment and significant delays in proper therapy, a gynecologic surgeon experienced in the management of ovarian cancer should be readily available, in the event an unexpected malignancy is encountered. Ideally, the staging surgery and definite treatment should be performed at the time of initial minilaparotomy. Comprehensive surgical staging and treatment include thorough exploration of the pelvis and abdomen, omentectomy, pelvic and paraaortic lymph node sampling, multiple peritoneal biopsies and washings, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and debulking, when indicated.

Prepare for surgery with position, incision, and retraction

Before beginning, it is crucial to correctly position the patient, make the appropriate incision, and insert the right retractor.1

Position. After administering regional or general anesthesia, place the patient in a modified lithotomy, as for laparoscopic surgery. Tuck the arms alongside the torso and place the legs in boot stirrups. Avoid hip flexion and allow adequate thigh abduction to expose the vagina. Perform a careful pelvic examination to determine the size and mobility of the adnexal mass.

When properly placed, this retractor creates an atraumatic, circular area of self-retraction, enabling superior exposure

Place an indwelling transurethral catheter, and pass a sturdy, hinged uterine manipulator such as the Pelosi Uterine Manipulator (Apple Medical Corp, Marlboro, Mass) transcervically into the uterine cavity (FIGURE 1).

The cruciate incision. With a conventional scalpel make a small suprapubic transverse incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue (FIGURE 2). After clearing subcutaneous fat from the midline, incise the rectus fascia and the peritoneum in a vertical direction.

A vertical skin incision can be selected if the preoperative workup suggests a later extension of the original minilaparotomy incision may be required, or if there is a prior vertical incision.

Retraction. Use a soft sleeve-type self-retaining plastic retractor, such as Mobius (Apple Medical Corp) (FIGURE 3 ). When properly placed, this retractor creates an atraumatic, circular area of self-retraction, enabling superior exposure of the pelvis (FIGURE 4).

During surgery it may be necessary to adjust the outer ring if the sleeve loosens. Narrow Deaver or Richardson retractors, if required, provide additional retraction. The bowel may be gently packed, if necessary, but typically it is adequately displaced by the large ovarian cyst.

The atraumatic retraction provided by the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor minimizes the possibility of tissue trauma, nerve damage, bruising, and postoperative pain. At the same time, the continuous 360° retraction force on the incision maximizes surgical exposure, providing a significantly larger working area than conventional retractors. For example, when applied to a 6-cm incision, the self-retaining retractor creates a 28-cm2 exposed working area, compared with only 18 cm2 provided by a conventional 4-point metal retractor.

The adjustable height of the self-retaining retractor adapts to wounds of varying depth and works on virtually any tissue thickness—a feature that makes the device effective for obese patients. Further, by lining the abdominal incision, the retractor’s plastic sleeve protects the wound’s edges from contamination and potential implantation of malignant cells, making the device ideal for managing ovarian cysts.

FIGURE 1 Hinged uterine manipulator

The manipulator facilitates exposure of the cyst and contralateral adnexa, as well as uterine elevation/rotation.

FIGURE 2 Cruciate incision

Make a 2.5- to 5-cm suprapubic transverse skin incision. Using the Bovie device, incise the subcutaneous fat transversely along the full length of the skin incision down to the level of the anterior rectus fascia. Clear the subcutaneous fat from the midline superiorly and inferiorly to expose 5 to 6 cm of the rectus fascia in the vertical axis. Use blunt digital dissection to assist in mobilizing the subcutaneous fat. Incise the anterior rectus fascia vertically through the full length of the cleared area. Retract the rectus muscles from the midline to expose the underlying transversalis fascia and the peritoneum. Control small bleeding points with the Bovie device. Enter the peritoneum either digitally or with scissors above the bladder dome and extend the peritoneal incision to the full length of the fascial incision.

FIGURE 3 Self-retaining retractor

The retractor consists of a flexible plastic inner ring and a firmer outer ring connected by a soft plastic sleeve.

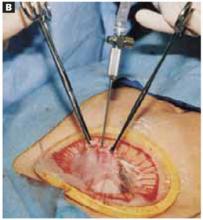

FIGURE 4360° retraction force

Squeeze the inner ring of the soft, sleeve-type, self-retaining retractor into the peritoneal cavity through the cruciate abdominal incision and allow it to spring open against the parietal peritoneum. Make a digital assessment to ensure that viscera is not trapped between the inner ring and the abdominal wall. Place the entire sleeve on traction by lifting the outer ring. Then roll the outer ring onto the sleeve, collecting excess length, until it sits firmly against the skin. The atraumatic retraction provided by the sleeve-type retractor maximizes exposure of the pelvis. Note how a portion of the large cyst is clearly seen through the atraumatic, circular area of retraction.

Cyst assessment

Visually and digitally inspect the cyst and carefully evaluate the uterus, pelvis, and contralateral adnexa. Determine the extent of adhesions and any unexpected pelvic pathology. When needed, use traditional small retractors or gentle packing to gain additional exposure. If the cystic mass appears suspicious (internal and external excrescences on the cyst, ovaries, or peritoneal surfaces, or ascites), obtain pelvic washings with a suction-irrigation cannula, send the fluid for cytologic examination, and convert the minilaparotomy to a standard exploratory laparotomy. Extensive adhesions to the bowel, broad ligament, or pelvic sidewall and unexpected extensive endometriosis may also require a conversion to standard laparotomy.

Reduce cyst size by decompression

Simple aspiration is inadvisable. To remove a large ovarian cyst using the Pelosi minilaparotomy, reduce the size of the cyst to permit safe and effective mobilization and resection through the small abdominal incision. Simple aspiration of the cyst, with its potential for spilling the contents, is not a wise strategy for several reasons. First, many ovarian cysts contain functional epithelium with a high recurrence rate (8% to 67%). Second, studies show that 10% to 66% of ovarian cyst fluid aspirates initially diagnosed as benign actually are malignant. Further, relying on negative cytology from the aspirate of an ovarian cyst without tissue biopsy may delay appropriate surgery, and the puncture of an unexpected malignant cyst may seed the peritoneal cavity and possibly worsen the patient’s prognosis.11,12

This technique, suitable for all ovarian cysts, makes it possible to aspirate a large cyst without leakage.

Whether spillage of cancer cells actually worsens the prognosis of a patient with a neoplastic cyst remains controversial because of conflicting study results. Nonetheless, the possibility of intraperitoneal dissemination of neoplastic cells from a ruptured cyst cannot be considered innocuous, and the potential negative effect on a patient’s prognosis should not be ignored.14 Make every attempt, therefore, to avoid rupturing the cyst and spilling the fluid into the peritoneal cavity.

A shared flaw plagues aspiration devices. Different devices are available for intraoperative cyst aspiration during laparoscopic, transvaginal, or laparotomy approaches.3,4,6 In addition to long needles, drainage trocars, suction cannulas, and suprapubic bladder catheters, special aspiration instruments have been developed.15 They include a metal vacuum system with an aspirator trocar that seals the surface of the cyst, and a catheter system that pinches the punctured cyst wall between double balloons to prevent spillage.16 In addition, several commercial bags are available to prevent intraperitoneal spillage during removal of ovarian cysts.

All these devices have a universal flaw, however: After a thin-walled cyst initially is punctured, none of these products can prevent the spontaneous dehiscence of the cyst and the resulting spillage of its contents into the abdominal cavity. Vacuum systems work well for large cysts with smooth, round surfaces, but in those with irregular surfaces, both application and maintaining the seal are difficult.17 Fortunately, our technique makes it possible to aspirate a large ovarian cyst without leakage, and the method is suitable for all ovarian cysts regardless of surface type or wall thickness.

Glue the dressing to the cyst to capture leakage. Using a gauze pad, carefully dry the area of the ovarian cyst that is visible through the self-retaining retractor. Then generously spread sterile surgical glue such as Dermabond (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) on the cyst wall surface (FIGURE 5A). Dermabond is the commercial name for 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, a sterile skin adhesive used as an alternative to stitches to close the edges of small wounds. It is similar to commercial adhesives such as Super Glue and Krazy Glue.

Remove the paper cover of a transparent plastic surgical dressing and place the adhesive side directly onto the glued cyst surface until you are sure the adhesive is completely fixed (FIGURES 5B AND 5C). The 35 cm x 35 cm Steri-Drape or the transparent Tegaderm (both from 3M Health Care, St. Paul, Minn) dressing is effective. A standard nonadhesive plastic dressing or a sterile plastic bag also can be used, as long as the free edges extend beyond the outer rim of the self-retaining retractor.

With a needle aspirator, pierce the cyst through the glued plastic dressing and carefully aspirate the fluid (FIGURES 6A AND 6B). Any leakage is trapped inside the plastic dressing rather than the abdominal cavity. Continue the aspiration until the collapsed cyst and ovary can be gradually delivered through the abdominal incision (FIGURE 6C). Note that the selfretaining retractor also protects the abdominal incision from potential contamination and implantation of neoplastic cells.

Once the cyst and ovary are extracted, you can readily perform an extracorporeal cystectomy, after which the repaired ovary is returned to the abdominal cavity. Be careful to avoid letting any fluid flow back into the peritoneal cavity during cyst removal. When indicated, an extracorporeal adnexectomy can readily be performed.

The presence of oily material or hairs in the aspirated fluid and on the needle tip readily identifies a dermoid cyst.

Dermoid cysts require extra care. Preventing intraperitoneal spillage is especially important when removing a large dermoid cyst, to avoid the possibility of chemical peritonitis, dense adhesions, and fistulas. The presence of oily material or hairs in the aspirated fluid and on the needle tip readily identifies a dermoid cyst. Quite frequently, a large-diameter suction cannula is required to remove the waxy contents. If the dermoid cyst is very large, aspiration alone will not empty it entirely. Complete emptying is not necessary, however. The primary goal of aspiration is to reduce the size and tension of the cyst to permit delivery through the abdominal incision.

Closing the cruciate incision is quicker and requires less exposure than a scaled-down Pfannenstiel’s incision.

Before concluding the procedure, irrigate the peritoneal cavity to remove any remnants of cyst contents that may have spilled—especially important with a dermoid cyst. Perform any additional indicated procedures through the minilaparotomy incision, such as a contralateral ovarian cystectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, or hysterectomy. After the surgery is completed, remove the self-retaining retractor by hooking a finger through the bottom ring and pulling it gently out of the incision. Closing the cruciate incision is quicker and requires less exposure to complete than a scaled-down Pfannenstiel’s incision. Apply a vertical pressure dressing over the incision to prevent postoperative wound hematoma or seroma formation. Remove the dressing 24 hours later.

FIGURE 5A ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

After drying the surface of the cyst, apply sterile surgical glue to the cyst wall (2 to 3 ampules are usually required to cover the cyst surface).

FIGURE 5B ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

Apply the adhesive side of a clear plastic wound dressing directly onto the cyst’s surface, making sure that the dressing is large enough to fully cover the self-retaining retractor. Using either a piece of folded gauze or your fingers, press the plastic dressing against the adhesive-coated cyst for about 3 to 5 minutes until the adhesive is completely fixed.

FIGURE 5C ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

Remove the paper cover of the wound dressing.

FIGURE 6A Aspirating the cyst

Pierce the dressing and carefully aspirate the fluid until the cyst is partially collapsed.

FIGURE 6B Aspirating the cyst

Place atraumatic clamps on the cyst wall to further control drainage. Any leakage is trapped inside the plastic dressing rather than draining into the abdominal cavity.

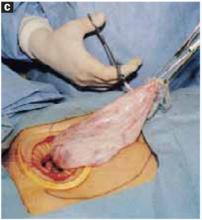

FIGURE 6C Aspirating the cyst

Continue the aspiration until the collapsed cyst and ovary can be delivered gradually through the abdominal incision, after detaching the adhesive plastic dressing from the edges of the self-retaining retractor. The portion of the plastic sleeve that is glued to the cyst surface remains attached to the cyst until the cyst is extracted. Following extraction, perform an extracorporeal cystectomy and return the repaired ovary to the abdominal cavity.

Good results

Using our approach, we have treated 38 patients with ovarian cysts of diameters greater than 20 cm thought to be benign by preoperative workup (FIGURE 7). We encountered no malignancies. All surgeries were successfully completed without laparoscopy or conversion to traditional laparotomy and with good cosmesis (FIGURE 8).

Other procedures performed in some of these patients using the same technique included contralateral cystectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, subtotal and total hysterectomy, adhesiolysis, and appendectomy. We encountered no intraoperative or postoperative complications. Operating times ranged from 18 to 65 minutes. All patients were discharged home within 36 hours and returned to work in a mean of 12 days. Pathology findings of the ovarian cysts included endometrioma, dermoid cyst, serous cystadenoma, and mucinous cystadenoma.

FIGURE 7 Effective for large cysts

Following removal, the collapsed cyst was refilled with 1,300 mL of normal saline to demonstrate its actual size.

FIGURE 8 Good cosmetic results

Cosmetic appearance of the small cruciate abdominal incision 10 days after surgery.Dr. Pelosi II reports that he is a consultant for Apple Medical Corporation. Dr. Pelosi III reports no affiliations or financial arrangements with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

- Make a cruciate incision by incising the skin transversely and the anterior rectus fascia vertically.

- Insert a soft, sleeved, self-retaining retractor.

- Using a surgical adhesive, glue a large plastic wound dressing to the surface of the cyst to prevent leakage of contents into the abdominal cavity.

- Aspirate the cyst until it collapses and can be delivered, with the ovary, through the abdominal incision.

- After performing an extracorporeal cystectomy and/or adnexectomy, return the repaired ovary to the abdominal cavity.

Although laparotomy is still considered the standard for ovarian cyst removal, over the past 15 years minimally invasive surgery has gained wider acceptance in cases where preoperative assessment suggests an adnexal mass is benign.

Unfortunately, minimally invasive management of a large ovarian cyst (greater than 10 cm) is particularly challenging for several reasons:

- The cyst can rupture and spill its contents into the peritoneum,

- the cyst’s size limits the surgical field, and

- an unexpected malignancy may be revealed.

An innovative minilaparotomy technique for the removal of benign ovarian cysts offers the advantages of laparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted procedures while bypassing the major disadvantages: the necessity for specialized and expensive equipment, lengthy operative time, and long learning curves.1 (The minimally invasive procedures currently available for the treatment of ovarian cysts include laparoscopic cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted minilaparotomy cystectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal cystectomy, combined percutaneous ultrasound cyst aspiration and laparoscopic cystectomy, transvaginal cystectomy, and the traditional minilaparotomy cystectomy.2-10)

The procedure is faster, less expensive, carries fewer potential risks than traditional alternatives, and offers these advantages:

- can be performed under regional anesthesia

- relies on standard open techniques

- uses inexpensive instrumentation

- is easy to learn

- can be used for very large cysts

- eliminates the risk of intraperitoneal spillage of cyst contents

- offers similar postoperative convalescence and mean time to return to work as laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted management of large ovarian cysts

General Ob/Gyns—not gynecologic oncologists—perform most surgeries on patients with adnexal masses, since ovarian cancer is relatively uncommon in the absence of preoperative risk factors for malignancy. Our approach offers an appealing option to Ob/Gyns reluctant to abandon routine traditional laparotomy for such ovarian cysts.

Selecting the right patient

Adequate preoperative assessment diminishes the risk of unexpected malignancy in a patient undergoing surgery for an ovarian mass to less than 1%.4 At this time, the combination of menopausal status, cancer antigen (CA) 125 level, physical examination, and ultrasound is the best strategy for evaluating the patient with an ovarian cyst.11

Signs of malignancy. Ultrasound features that suggest malignancy include irregular borders, thick septa, solid areas, internal and external excrescences, matted bowel, and ascites. Benign cysts, on the other hand, are usually unilateral and have regular borders, thin septa, no solid areas, and no internal excrescences.4 The measurement of blood flow within the mass by color Doppler may improve the accuracy of ultrasound in differentiating benign from malignant cysts.4,12

On physical examination, an adnexal mass that is fixed, irregular, or solid also suggests a neoplasm. An elevated CA 125 combined with a complex adnexal mass is likely to be associated with malignancy. The test is even more specific in postmenopausal women with adnexal masses.4,12

However, plasma levels of CA 125 also can be elevated in several benign gynecologic conditions such as endometriosis, simple ovarian cysts, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, fibroids, and in physiologic conditions such as menstruation and pregnancy.13

Anticipate the need to convert to laparotomy. Every patient’s surgical consent should include a possible conversion to laparotomy. To avoid incomplete surgical treatment and significant delays in proper therapy, a gynecologic surgeon experienced in the management of ovarian cancer should be readily available, in the event an unexpected malignancy is encountered. Ideally, the staging surgery and definite treatment should be performed at the time of initial minilaparotomy. Comprehensive surgical staging and treatment include thorough exploration of the pelvis and abdomen, omentectomy, pelvic and paraaortic lymph node sampling, multiple peritoneal biopsies and washings, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and debulking, when indicated.

Prepare for surgery with position, incision, and retraction

Before beginning, it is crucial to correctly position the patient, make the appropriate incision, and insert the right retractor.1

Position. After administering regional or general anesthesia, place the patient in a modified lithotomy, as for laparoscopic surgery. Tuck the arms alongside the torso and place the legs in boot stirrups. Avoid hip flexion and allow adequate thigh abduction to expose the vagina. Perform a careful pelvic examination to determine the size and mobility of the adnexal mass.

When properly placed, this retractor creates an atraumatic, circular area of self-retraction, enabling superior exposure

Place an indwelling transurethral catheter, and pass a sturdy, hinged uterine manipulator such as the Pelosi Uterine Manipulator (Apple Medical Corp, Marlboro, Mass) transcervically into the uterine cavity (FIGURE 1).

The cruciate incision. With a conventional scalpel make a small suprapubic transverse incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue (FIGURE 2). After clearing subcutaneous fat from the midline, incise the rectus fascia and the peritoneum in a vertical direction.

A vertical skin incision can be selected if the preoperative workup suggests a later extension of the original minilaparotomy incision may be required, or if there is a prior vertical incision.

Retraction. Use a soft sleeve-type self-retaining plastic retractor, such as Mobius (Apple Medical Corp) (FIGURE 3 ). When properly placed, this retractor creates an atraumatic, circular area of self-retraction, enabling superior exposure of the pelvis (FIGURE 4).

During surgery it may be necessary to adjust the outer ring if the sleeve loosens. Narrow Deaver or Richardson retractors, if required, provide additional retraction. The bowel may be gently packed, if necessary, but typically it is adequately displaced by the large ovarian cyst.

The atraumatic retraction provided by the soft, self-retaining abdominal retractor minimizes the possibility of tissue trauma, nerve damage, bruising, and postoperative pain. At the same time, the continuous 360° retraction force on the incision maximizes surgical exposure, providing a significantly larger working area than conventional retractors. For example, when applied to a 6-cm incision, the self-retaining retractor creates a 28-cm2 exposed working area, compared with only 18 cm2 provided by a conventional 4-point metal retractor.

The adjustable height of the self-retaining retractor adapts to wounds of varying depth and works on virtually any tissue thickness—a feature that makes the device effective for obese patients. Further, by lining the abdominal incision, the retractor’s plastic sleeve protects the wound’s edges from contamination and potential implantation of malignant cells, making the device ideal for managing ovarian cysts.

FIGURE 1 Hinged uterine manipulator

The manipulator facilitates exposure of the cyst and contralateral adnexa, as well as uterine elevation/rotation.

FIGURE 2 Cruciate incision

Make a 2.5- to 5-cm suprapubic transverse skin incision. Using the Bovie device, incise the subcutaneous fat transversely along the full length of the skin incision down to the level of the anterior rectus fascia. Clear the subcutaneous fat from the midline superiorly and inferiorly to expose 5 to 6 cm of the rectus fascia in the vertical axis. Use blunt digital dissection to assist in mobilizing the subcutaneous fat. Incise the anterior rectus fascia vertically through the full length of the cleared area. Retract the rectus muscles from the midline to expose the underlying transversalis fascia and the peritoneum. Control small bleeding points with the Bovie device. Enter the peritoneum either digitally or with scissors above the bladder dome and extend the peritoneal incision to the full length of the fascial incision.

FIGURE 3 Self-retaining retractor

The retractor consists of a flexible plastic inner ring and a firmer outer ring connected by a soft plastic sleeve.

FIGURE 4360° retraction force

Squeeze the inner ring of the soft, sleeve-type, self-retaining retractor into the peritoneal cavity through the cruciate abdominal incision and allow it to spring open against the parietal peritoneum. Make a digital assessment to ensure that viscera is not trapped between the inner ring and the abdominal wall. Place the entire sleeve on traction by lifting the outer ring. Then roll the outer ring onto the sleeve, collecting excess length, until it sits firmly against the skin. The atraumatic retraction provided by the sleeve-type retractor maximizes exposure of the pelvis. Note how a portion of the large cyst is clearly seen through the atraumatic, circular area of retraction.

Cyst assessment

Visually and digitally inspect the cyst and carefully evaluate the uterus, pelvis, and contralateral adnexa. Determine the extent of adhesions and any unexpected pelvic pathology. When needed, use traditional small retractors or gentle packing to gain additional exposure. If the cystic mass appears suspicious (internal and external excrescences on the cyst, ovaries, or peritoneal surfaces, or ascites), obtain pelvic washings with a suction-irrigation cannula, send the fluid for cytologic examination, and convert the minilaparotomy to a standard exploratory laparotomy. Extensive adhesions to the bowel, broad ligament, or pelvic sidewall and unexpected extensive endometriosis may also require a conversion to standard laparotomy.

Reduce cyst size by decompression

Simple aspiration is inadvisable. To remove a large ovarian cyst using the Pelosi minilaparotomy, reduce the size of the cyst to permit safe and effective mobilization and resection through the small abdominal incision. Simple aspiration of the cyst, with its potential for spilling the contents, is not a wise strategy for several reasons. First, many ovarian cysts contain functional epithelium with a high recurrence rate (8% to 67%). Second, studies show that 10% to 66% of ovarian cyst fluid aspirates initially diagnosed as benign actually are malignant. Further, relying on negative cytology from the aspirate of an ovarian cyst without tissue biopsy may delay appropriate surgery, and the puncture of an unexpected malignant cyst may seed the peritoneal cavity and possibly worsen the patient’s prognosis.11,12

This technique, suitable for all ovarian cysts, makes it possible to aspirate a large cyst without leakage.

Whether spillage of cancer cells actually worsens the prognosis of a patient with a neoplastic cyst remains controversial because of conflicting study results. Nonetheless, the possibility of intraperitoneal dissemination of neoplastic cells from a ruptured cyst cannot be considered innocuous, and the potential negative effect on a patient’s prognosis should not be ignored.14 Make every attempt, therefore, to avoid rupturing the cyst and spilling the fluid into the peritoneal cavity.

A shared flaw plagues aspiration devices. Different devices are available for intraoperative cyst aspiration during laparoscopic, transvaginal, or laparotomy approaches.3,4,6 In addition to long needles, drainage trocars, suction cannulas, and suprapubic bladder catheters, special aspiration instruments have been developed.15 They include a metal vacuum system with an aspirator trocar that seals the surface of the cyst, and a catheter system that pinches the punctured cyst wall between double balloons to prevent spillage.16 In addition, several commercial bags are available to prevent intraperitoneal spillage during removal of ovarian cysts.

All these devices have a universal flaw, however: After a thin-walled cyst initially is punctured, none of these products can prevent the spontaneous dehiscence of the cyst and the resulting spillage of its contents into the abdominal cavity. Vacuum systems work well for large cysts with smooth, round surfaces, but in those with irregular surfaces, both application and maintaining the seal are difficult.17 Fortunately, our technique makes it possible to aspirate a large ovarian cyst without leakage, and the method is suitable for all ovarian cysts regardless of surface type or wall thickness.

Glue the dressing to the cyst to capture leakage. Using a gauze pad, carefully dry the area of the ovarian cyst that is visible through the self-retaining retractor. Then generously spread sterile surgical glue such as Dermabond (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) on the cyst wall surface (FIGURE 5A). Dermabond is the commercial name for 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, a sterile skin adhesive used as an alternative to stitches to close the edges of small wounds. It is similar to commercial adhesives such as Super Glue and Krazy Glue.

Remove the paper cover of a transparent plastic surgical dressing and place the adhesive side directly onto the glued cyst surface until you are sure the adhesive is completely fixed (FIGURES 5B AND 5C). The 35 cm x 35 cm Steri-Drape or the transparent Tegaderm (both from 3M Health Care, St. Paul, Minn) dressing is effective. A standard nonadhesive plastic dressing or a sterile plastic bag also can be used, as long as the free edges extend beyond the outer rim of the self-retaining retractor.

With a needle aspirator, pierce the cyst through the glued plastic dressing and carefully aspirate the fluid (FIGURES 6A AND 6B). Any leakage is trapped inside the plastic dressing rather than the abdominal cavity. Continue the aspiration until the collapsed cyst and ovary can be gradually delivered through the abdominal incision (FIGURE 6C). Note that the selfretaining retractor also protects the abdominal incision from potential contamination and implantation of neoplastic cells.

Once the cyst and ovary are extracted, you can readily perform an extracorporeal cystectomy, after which the repaired ovary is returned to the abdominal cavity. Be careful to avoid letting any fluid flow back into the peritoneal cavity during cyst removal. When indicated, an extracorporeal adnexectomy can readily be performed.

The presence of oily material or hairs in the aspirated fluid and on the needle tip readily identifies a dermoid cyst.

Dermoid cysts require extra care. Preventing intraperitoneal spillage is especially important when removing a large dermoid cyst, to avoid the possibility of chemical peritonitis, dense adhesions, and fistulas. The presence of oily material or hairs in the aspirated fluid and on the needle tip readily identifies a dermoid cyst. Quite frequently, a large-diameter suction cannula is required to remove the waxy contents. If the dermoid cyst is very large, aspiration alone will not empty it entirely. Complete emptying is not necessary, however. The primary goal of aspiration is to reduce the size and tension of the cyst to permit delivery through the abdominal incision.

Closing the cruciate incision is quicker and requires less exposure than a scaled-down Pfannenstiel’s incision.

Before concluding the procedure, irrigate the peritoneal cavity to remove any remnants of cyst contents that may have spilled—especially important with a dermoid cyst. Perform any additional indicated procedures through the minilaparotomy incision, such as a contralateral ovarian cystectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, or hysterectomy. After the surgery is completed, remove the self-retaining retractor by hooking a finger through the bottom ring and pulling it gently out of the incision. Closing the cruciate incision is quicker and requires less exposure to complete than a scaled-down Pfannenstiel’s incision. Apply a vertical pressure dressing over the incision to prevent postoperative wound hematoma or seroma formation. Remove the dressing 24 hours later.

FIGURE 5A ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

After drying the surface of the cyst, apply sterile surgical glue to the cyst wall (2 to 3 ampules are usually required to cover the cyst surface).

FIGURE 5B ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

Apply the adhesive side of a clear plastic wound dressing directly onto the cyst’s surface, making sure that the dressing is large enough to fully cover the self-retaining retractor. Using either a piece of folded gauze or your fingers, press the plastic dressing against the adhesive-coated cyst for about 3 to 5 minutes until the adhesive is completely fixed.

FIGURE 5C ‘Leak-proofing’ the aspiration

Remove the paper cover of the wound dressing.

FIGURE 6A Aspirating the cyst

Pierce the dressing and carefully aspirate the fluid until the cyst is partially collapsed.

FIGURE 6B Aspirating the cyst

Place atraumatic clamps on the cyst wall to further control drainage. Any leakage is trapped inside the plastic dressing rather than draining into the abdominal cavity.

FIGURE 6C Aspirating the cyst

Continue the aspiration until the collapsed cyst and ovary can be delivered gradually through the abdominal incision, after detaching the adhesive plastic dressing from the edges of the self-retaining retractor. The portion of the plastic sleeve that is glued to the cyst surface remains attached to the cyst until the cyst is extracted. Following extraction, perform an extracorporeal cystectomy and return the repaired ovary to the abdominal cavity.

Good results

Using our approach, we have treated 38 patients with ovarian cysts of diameters greater than 20 cm thought to be benign by preoperative workup (FIGURE 7). We encountered no malignancies. All surgeries were successfully completed without laparoscopy or conversion to traditional laparotomy and with good cosmesis (FIGURE 8).

Other procedures performed in some of these patients using the same technique included contralateral cystectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, subtotal and total hysterectomy, adhesiolysis, and appendectomy. We encountered no intraoperative or postoperative complications. Operating times ranged from 18 to 65 minutes. All patients were discharged home within 36 hours and returned to work in a mean of 12 days. Pathology findings of the ovarian cysts included endometrioma, dermoid cyst, serous cystadenoma, and mucinous cystadenoma.

FIGURE 7 Effective for large cysts

Following removal, the collapsed cyst was refilled with 1,300 mL of normal saline to demonstrate its actual size.

FIGURE 8 Good cosmetic results

Cosmetic appearance of the small cruciate abdominal incision 10 days after surgery.Dr. Pelosi II reports that he is a consultant for Apple Medical Corporation. Dr. Pelosi III reports no affiliations or financial arrangements with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: Effective alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. OBG Management. 2003;15(4):16-33.

2. Havrilesky LJ, Peterson BL, Dryden DK, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes in the laparoscopic management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:243-251.

3. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Laparoscopic removal of a 103 pound ovarian tumor. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3:413-417.

4. Eltabbaku GH. Laparoscopic management of ovarian cysts. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2003;48(8):37-50.

5. Ou C, Liu Y, Zabriskie V, et al. Alternate method for laparoscopic management of adnexal masses greater than 10 cm in diameter. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2001;11:125-132.

6. Jeong E, Kim H, Ahn C, et al. Successful laparoscopic removal of huge ovarian cysts. J Am Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4:609-614.

7. Nagele F, Magos AL. Combined ultrasonographically guided drainage and laparoscopic excision of a large ovarian cyst. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1377-1378.

8. Sheth S. Adnexal pathology. In: Sheth S, Studd J, eds. Vaginal Hysterectomy. London, England: Martin Dunitz; 2002;165-178.

9. Flynn MK, Niloff JM. Outpatient minilaparotomy for ovarian cysts. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:399-404.

10. Benedetti P, Panicci P, Maneschi F, et al. Surgery by minilaparotomy in benign gynecological disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:456-459.

11. Jansen FW, Tanahotoe S, Veselie M, et al. Laparoscopic aspiration of ovarian cysts: an unreliable technique in primary diagnosis of sonographically benign ovarian lesions. Gynecol Endosc. 1997;6:363-367.

12. Parker WH. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass in postmenopausal women. J Gynecol Tech. 1995;1:3-5.

13. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Mais V, et al. Prelaparoscopic assessment of ovarian cysts in reproductive-age women. Gynecol Endosc. 1997;6:157-167.

14. Fowler JM, Carter JR. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass in postmenopausal women. J Gynecol Tech. 1995;1:7-10.

15. McCormick JB, Fitzgibbons JP. Instrument for aspiration of large ovarian cysts. Obstet Gynecol. 1967;29:869-870.

16. Yamada T, Okamoto Y, Kasematsu H. Use of the Sand balloon catheter for the laparoscopic surgery of benign ovarian cysts. Gynecol Endosc. 1999;9:51-54.

17. Shozu M, Segawa T, Sumitani H, et al. Leak-proof puncture of ovarian cysts: instant mounting of plastic bag using cyanoacrylate adhesive. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:1007-1010.

1. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: Effective alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. OBG Management. 2003;15(4):16-33.

2. Havrilesky LJ, Peterson BL, Dryden DK, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes in the laparoscopic management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:243-251.

3. Pelosi MA, II, Pelosi MA, III. Laparoscopic removal of a 103 pound ovarian tumor. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3:413-417.

4. Eltabbaku GH. Laparoscopic management of ovarian cysts. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2003;48(8):37-50.

5. Ou C, Liu Y, Zabriskie V, et al. Alternate method for laparoscopic management of adnexal masses greater than 10 cm in diameter. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2001;11:125-132.

6. Jeong E, Kim H, Ahn C, et al. Successful laparoscopic removal of huge ovarian cysts. J Am Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4:609-614.

7. Nagele F, Magos AL. Combined ultrasonographically guided drainage and laparoscopic excision of a large ovarian cyst. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1377-1378.

8. Sheth S. Adnexal pathology. In: Sheth S, Studd J, eds. Vaginal Hysterectomy. London, England: Martin Dunitz; 2002;165-178.

9. Flynn MK, Niloff JM. Outpatient minilaparotomy for ovarian cysts. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:399-404.

10. Benedetti P, Panicci P, Maneschi F, et al. Surgery by minilaparotomy in benign gynecological disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:456-459.

11. Jansen FW, Tanahotoe S, Veselie M, et al. Laparoscopic aspiration of ovarian cysts: an unreliable technique in primary diagnosis of sonographically benign ovarian lesions. Gynecol Endosc. 1997;6:363-367.

12. Parker WH. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass in postmenopausal women. J Gynecol Tech. 1995;1:3-5.

13. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Mais V, et al. Prelaparoscopic assessment of ovarian cysts in reproductive-age women. Gynecol Endosc. 1997;6:157-167.

14. Fowler JM, Carter JR. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass in postmenopausal women. J Gynecol Tech. 1995;1:7-10.

15. McCormick JB, Fitzgibbons JP. Instrument for aspiration of large ovarian cysts. Obstet Gynecol. 1967;29:869-870.

16. Yamada T, Okamoto Y, Kasematsu H. Use of the Sand balloon catheter for the laparoscopic surgery of benign ovarian cysts. Gynecol Endosc. 1999;9:51-54.

17. Shozu M, Segawa T, Sumitani H, et al. Leak-proof puncture of ovarian cysts: instant mounting of plastic bag using cyanoacrylate adhesive. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:1007-1010.