User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

CPAP safety for infants with bronchiolitis on the general pediatrics floor

SEATTLE – Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego has been doing continuous positive airway pressure for infants with bronchiolitis on the general pediatrics floors safely and with no problems for nearly 20 years, according to a presentation at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

It’s newsworthy because “very, very few” hospitals do bronchiolitis continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) outside of the ICU. “The perception is that there are complications, and you might miss kids that are really sick if you keep them on the floor.” However, “we have been doing it safely for so long that no one thinks twice about it,” said Christiane Lenzen, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady and an assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

It doesn’t matter if children have congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, or other problems, she said, “if they are stable enough for the floor, we will see if it’s okay.”

Rady’s hand was forced on the issue because it has a large catchment area but limited ICU beds, so for practical reasons and within certain limits, CPAP moved to the floors. One of Dr. Lenzen’s colleagues noted that, as long as there’s nurse and respiratory leadership buy in, “it’s actually quite easy to pull off in a very safe manner.”

Rady has a significant advantage over community hospitals and other places considering the approach, because it has onsite pediatric ICU services for when things head south. Over the past 3 or so years, 52% of the children the pediatric hospital medicine service started on CPAP (168/324) had to be transferred to the ICU; 17% were ultimately intubated.

Many of those transfers were caused by comorbidities, not CPAP failure, but other times children needed greater respiratory support; in general, the floor CPAP limit is 6 cm H2O and a fraction of inspired oxygen of 50%. Also, sometimes children needed to be sedated for CPAP, which isn’t done on the floor.

With the 52% transfer rate, “I would worry about patients who are sick enough to need CPAP staying” in a hospital without quick access to ICU services, Dr. Lenzen said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Even so, among 324 children who at least initially were treated with CPAP on the floor – out of 2,424 admitted to the pediatric hospital medicine service with bronchiolitis – there hasn’t been a single pneumothorax, aspiration event, or CPAP equipment–related injury, she said.

CPAP on the floor has several benefits. ICU resources are conserved, patient handoffs and the work of transfers into and out of the ICU are avoided, families don’t have to get used to a new treatment team, and infants aren’t subjected to the jarring ICU environment.

For it to work, though, staff “really need to be on top of this,” and “it needs to be very tightly controlled” with order sets and other measures, the presenters said. There’s regular training at Rady for nurses, respiratory therapists, and hospitalists on CPAP equipment, airway management, monitoring, troubleshooting, and other essentials.

Almost all children on the pediatric floors have a trial of high-flow nasal cannula with an upper limit of 8 L/min. If the Respiratory Assessment Score hasn’t improved in an hour, CPAP is considered. If a child is admitted with a score above 10 and they seem to be worsening, they go straight to CPAP.

Children alternate between nasal prongs and nasal masks to prevent pressure necrosis, and are kept nil per os while on CPAP. They are on continual pulse oximetry and cardiorespiratory monitoring. Vital signs and respiratory scores are checked frequently, more so for children who are struggling.

The patient-to-nurse ratio drops from the usual 4:1 to 3:1 when a child goes on CPAP, and to 2:1 if necessary. Traveling nurses aren’t allowed to take CPAP cases.

The presenters didn’t report any disclosures.

This article was updated 8/27/19.

SEATTLE – Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego has been doing continuous positive airway pressure for infants with bronchiolitis on the general pediatrics floors safely and with no problems for nearly 20 years, according to a presentation at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

It’s newsworthy because “very, very few” hospitals do bronchiolitis continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) outside of the ICU. “The perception is that there are complications, and you might miss kids that are really sick if you keep them on the floor.” However, “we have been doing it safely for so long that no one thinks twice about it,” said Christiane Lenzen, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady and an assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

It doesn’t matter if children have congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, or other problems, she said, “if they are stable enough for the floor, we will see if it’s okay.”

Rady’s hand was forced on the issue because it has a large catchment area but limited ICU beds, so for practical reasons and within certain limits, CPAP moved to the floors. One of Dr. Lenzen’s colleagues noted that, as long as there’s nurse and respiratory leadership buy in, “it’s actually quite easy to pull off in a very safe manner.”

Rady has a significant advantage over community hospitals and other places considering the approach, because it has onsite pediatric ICU services for when things head south. Over the past 3 or so years, 52% of the children the pediatric hospital medicine service started on CPAP (168/324) had to be transferred to the ICU; 17% were ultimately intubated.

Many of those transfers were caused by comorbidities, not CPAP failure, but other times children needed greater respiratory support; in general, the floor CPAP limit is 6 cm H2O and a fraction of inspired oxygen of 50%. Also, sometimes children needed to be sedated for CPAP, which isn’t done on the floor.

With the 52% transfer rate, “I would worry about patients who are sick enough to need CPAP staying” in a hospital without quick access to ICU services, Dr. Lenzen said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Even so, among 324 children who at least initially were treated with CPAP on the floor – out of 2,424 admitted to the pediatric hospital medicine service with bronchiolitis – there hasn’t been a single pneumothorax, aspiration event, or CPAP equipment–related injury, she said.

CPAP on the floor has several benefits. ICU resources are conserved, patient handoffs and the work of transfers into and out of the ICU are avoided, families don’t have to get used to a new treatment team, and infants aren’t subjected to the jarring ICU environment.

For it to work, though, staff “really need to be on top of this,” and “it needs to be very tightly controlled” with order sets and other measures, the presenters said. There’s regular training at Rady for nurses, respiratory therapists, and hospitalists on CPAP equipment, airway management, monitoring, troubleshooting, and other essentials.

Almost all children on the pediatric floors have a trial of high-flow nasal cannula with an upper limit of 8 L/min. If the Respiratory Assessment Score hasn’t improved in an hour, CPAP is considered. If a child is admitted with a score above 10 and they seem to be worsening, they go straight to CPAP.

Children alternate between nasal prongs and nasal masks to prevent pressure necrosis, and are kept nil per os while on CPAP. They are on continual pulse oximetry and cardiorespiratory monitoring. Vital signs and respiratory scores are checked frequently, more so for children who are struggling.

The patient-to-nurse ratio drops from the usual 4:1 to 3:1 when a child goes on CPAP, and to 2:1 if necessary. Traveling nurses aren’t allowed to take CPAP cases.

The presenters didn’t report any disclosures.

This article was updated 8/27/19.

SEATTLE – Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego has been doing continuous positive airway pressure for infants with bronchiolitis on the general pediatrics floors safely and with no problems for nearly 20 years, according to a presentation at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

It’s newsworthy because “very, very few” hospitals do bronchiolitis continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) outside of the ICU. “The perception is that there are complications, and you might miss kids that are really sick if you keep them on the floor.” However, “we have been doing it safely for so long that no one thinks twice about it,” said Christiane Lenzen, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady and an assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

It doesn’t matter if children have congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, or other problems, she said, “if they are stable enough for the floor, we will see if it’s okay.”

Rady’s hand was forced on the issue because it has a large catchment area but limited ICU beds, so for practical reasons and within certain limits, CPAP moved to the floors. One of Dr. Lenzen’s colleagues noted that, as long as there’s nurse and respiratory leadership buy in, “it’s actually quite easy to pull off in a very safe manner.”

Rady has a significant advantage over community hospitals and other places considering the approach, because it has onsite pediatric ICU services for when things head south. Over the past 3 or so years, 52% of the children the pediatric hospital medicine service started on CPAP (168/324) had to be transferred to the ICU; 17% were ultimately intubated.

Many of those transfers were caused by comorbidities, not CPAP failure, but other times children needed greater respiratory support; in general, the floor CPAP limit is 6 cm H2O and a fraction of inspired oxygen of 50%. Also, sometimes children needed to be sedated for CPAP, which isn’t done on the floor.

With the 52% transfer rate, “I would worry about patients who are sick enough to need CPAP staying” in a hospital without quick access to ICU services, Dr. Lenzen said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Even so, among 324 children who at least initially were treated with CPAP on the floor – out of 2,424 admitted to the pediatric hospital medicine service with bronchiolitis – there hasn’t been a single pneumothorax, aspiration event, or CPAP equipment–related injury, she said.

CPAP on the floor has several benefits. ICU resources are conserved, patient handoffs and the work of transfers into and out of the ICU are avoided, families don’t have to get used to a new treatment team, and infants aren’t subjected to the jarring ICU environment.

For it to work, though, staff “really need to be on top of this,” and “it needs to be very tightly controlled” with order sets and other measures, the presenters said. There’s regular training at Rady for nurses, respiratory therapists, and hospitalists on CPAP equipment, airway management, monitoring, troubleshooting, and other essentials.

Almost all children on the pediatric floors have a trial of high-flow nasal cannula with an upper limit of 8 L/min. If the Respiratory Assessment Score hasn’t improved in an hour, CPAP is considered. If a child is admitted with a score above 10 and they seem to be worsening, they go straight to CPAP.

Children alternate between nasal prongs and nasal masks to prevent pressure necrosis, and are kept nil per os while on CPAP. They are on continual pulse oximetry and cardiorespiratory monitoring. Vital signs and respiratory scores are checked frequently, more so for children who are struggling.

The patient-to-nurse ratio drops from the usual 4:1 to 3:1 when a child goes on CPAP, and to 2:1 if necessary. Traveling nurses aren’t allowed to take CPAP cases.

The presenters didn’t report any disclosures.

This article was updated 8/27/19.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PHM 2019

Pediatric hospitalist certification beset by gender bias concerns

Are women unfairly penalized?

More than 1,625 pediatricians have applied to take the first pediatric hospitalist certification exam in November 2019, and approximately 93% of them have been accepted, according to a statement from the American Board of Pediatrics.

It was the rejection of the 7%, however, that set off a firestorm on the electronic discussion board for American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) hospital medicine this summer, and led to a petition to the board to revise its eligibility requirements, ensure that the requirements are fair to women, and bring transparency to its decision process. The petition has more than 1,400 signatures.

Seattle Children’s Hospital and Yale New Haven (Conn.) Children’s Hospital have both said they will not consider board certification in hiring decisions until the situation is resolved.

The American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) declined an interview request pending its formal response to the Aug. 6 petition, but in a statement to this news organization, executive vice president Suzanne Woods, MD, said, “The percentage of women and men meeting the eligibility requirements for the exam did not differ. We stress this point because a concern about possible gender bias appears to have been the principal reason for this ... petition, and we wanted to offer immediate reassurance that no unintended bias has occurred.”

“We are carefully considering the requests and will release detailed data to hospitalists on the AAP’s [pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) electronic discussion board] ... and on the ABP’s website. We are conferring with ABP PHM subboard members as well as leaders from our volunteer community. We expect to provide a thoughtful response within the next 3 weeks,” Dr. Woods said in the Aug. 15 statement.

“Case-by-case” exceptions

The backstory is that, for better or worse depending on who you talk to, pediatric hospital medicine is becoming a board certified subspecialty. A fellowship will be required to sit for the exam after a few years, which is standard for subspecialties.

What’s generated concern is how the board is grandfathering current pediatric hospitalists into certification via a “practice pathway” until the fellowship requirement takes hold after 2023.

To qualify for the November test, hospitalists had to complete 4 years of full-time practice by June 30, 2019, which has been understood to mean 48 months of continual employment. At least 50% of that time had to be devoted to “professional activities ... related to the care of hospitalized children,” and at least 25% of that “devoted to direct patient care.” Assuming about 2,000 work hours per year, it translated to “450-500 hours” of direct patient care “per year over the most recent four years” to sit for the test, the board said.

“For individuals who have interrupted practice during the most recent four years for family leave or other such circumstances, an exception may be considered if there is substantial prior experience in pediatric hospital medicine. ... Such exceptions are made at the discretion of the ABP and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.” Specific criteria for exceptions were not spelled out.

In the end, there were more than a few surprises when denial letters went out in recent months, and scores of appeals have been filed. There’s “a lot of tension and a lot of confusion” about why some people with practice gaps during the 4 years were approved, but others were denied. There’s been “a lack of transparency on the ABP’s part,” said H. Barrett Fromme, MD, section chief of pediatric hospital medicine and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago.

“The standard has to be reasonable”

There are concerns about the availability of fellowship slots and other issues, but the 4-year rule – instead of averaging clinical hours over 4 or 5 years, for instance – is the main sticking point. It’s a gender issue because “women take maternity; women move with their spouse; women take care of elders; women tend to be in these roles that require time off” more than men do, Dr. Fromme said.

Until the board releases its data, the gender breakdown of the denials and the degree to which practice gaps due to such issues led to them is unknown. There’s concern that women have been unfairly penalized.

The storm was set off on the discussion board this summer by stories from physicians such as Chandani DeZure, MD, a pediatric hospitalist currently working in the neonatal ICU at Stanford (Calif.) University. She was denied a seat at the table in November, appealed, and was denied again.

She was a full-time pediatric hospitalist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, from 2014, when she graduated residency, until Oct. 2018, when her husband, also a doctor, was offered a promising research position in California, and “we decided to take it,” Dr. DeZure said.

They moved to California with their young son in November. Dr. DeZure got her California medical license in 6 weeks, was hired by Stanford in January, and started her new postion in mid-April.

Because of the move, she worked only 3.5 years in the board’s 4 year practice window, but, as is common with young physicians, that time was spent in direct patient care, for a total of over 6,000 hours.

“How is that not good enough? How is a person that worked 500 hours with patients for 4 years” – for a total of 2,000 hours – “better qualified than someone who worked 100% for 3 and a half years? Nobody is saying there shouldn’t be a standard, but the standard has to be reasonable,” Dr. DeZure said.

“Illegal regardless of intent”

It’s situations like Dr. DeZure’s that led to the petition. One of demands is that ABP “revise the practice pathway criteria to be more inclusive of applicants with interrupted practice and varied clinical experience, to include clear-cut parameters rather than considering these applications on a closed-door ‘case-by-case basis...at the discretion of the ABP.’ ” Also, the petition asks the board to “clarify the appeals process and improve responsiveness to appeals and inquiries regarding denials.”

As ABP noted in its statement, however, the major demand is that the board “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias is present.” The petition noted that signers “do not suspect intentional bias on the part of the ABP; however, if gender bias is present it is unethical and potentially illegal regardless of intent.”

For now, the perception is that the board has “a hard 48-month rule” with not many exceptions; there are people who are “very concerned that, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t have children for 4 years because I won’t be able to sit for the boards.’ No one should ever have to have that in their head,” Dr. Fromme said. At this point, it seems that 3 months off for maternity is being grandfathered in, but perhaps not 6 months for a second child; no one knows for sure.

Dr. DeZure, meanwhile, continues to study for the board exam, just in case.

Looking back over the past year, she said “I could have somehow picked up one shift a week moonlighting that would have kept me eligible, but the [board] didn’t respond to me” when contacted about her situation during the California move.

“The other option was for me was to live cross country from my husband with a small child,” she said.

Are women unfairly penalized?

Are women unfairly penalized?

More than 1,625 pediatricians have applied to take the first pediatric hospitalist certification exam in November 2019, and approximately 93% of them have been accepted, according to a statement from the American Board of Pediatrics.

It was the rejection of the 7%, however, that set off a firestorm on the electronic discussion board for American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) hospital medicine this summer, and led to a petition to the board to revise its eligibility requirements, ensure that the requirements are fair to women, and bring transparency to its decision process. The petition has more than 1,400 signatures.

Seattle Children’s Hospital and Yale New Haven (Conn.) Children’s Hospital have both said they will not consider board certification in hiring decisions until the situation is resolved.

The American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) declined an interview request pending its formal response to the Aug. 6 petition, but in a statement to this news organization, executive vice president Suzanne Woods, MD, said, “The percentage of women and men meeting the eligibility requirements for the exam did not differ. We stress this point because a concern about possible gender bias appears to have been the principal reason for this ... petition, and we wanted to offer immediate reassurance that no unintended bias has occurred.”

“We are carefully considering the requests and will release detailed data to hospitalists on the AAP’s [pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) electronic discussion board] ... and on the ABP’s website. We are conferring with ABP PHM subboard members as well as leaders from our volunteer community. We expect to provide a thoughtful response within the next 3 weeks,” Dr. Woods said in the Aug. 15 statement.

“Case-by-case” exceptions

The backstory is that, for better or worse depending on who you talk to, pediatric hospital medicine is becoming a board certified subspecialty. A fellowship will be required to sit for the exam after a few years, which is standard for subspecialties.

What’s generated concern is how the board is grandfathering current pediatric hospitalists into certification via a “practice pathway” until the fellowship requirement takes hold after 2023.

To qualify for the November test, hospitalists had to complete 4 years of full-time practice by June 30, 2019, which has been understood to mean 48 months of continual employment. At least 50% of that time had to be devoted to “professional activities ... related to the care of hospitalized children,” and at least 25% of that “devoted to direct patient care.” Assuming about 2,000 work hours per year, it translated to “450-500 hours” of direct patient care “per year over the most recent four years” to sit for the test, the board said.

“For individuals who have interrupted practice during the most recent four years for family leave or other such circumstances, an exception may be considered if there is substantial prior experience in pediatric hospital medicine. ... Such exceptions are made at the discretion of the ABP and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.” Specific criteria for exceptions were not spelled out.

In the end, there were more than a few surprises when denial letters went out in recent months, and scores of appeals have been filed. There’s “a lot of tension and a lot of confusion” about why some people with practice gaps during the 4 years were approved, but others were denied. There’s been “a lack of transparency on the ABP’s part,” said H. Barrett Fromme, MD, section chief of pediatric hospital medicine and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago.

“The standard has to be reasonable”

There are concerns about the availability of fellowship slots and other issues, but the 4-year rule – instead of averaging clinical hours over 4 or 5 years, for instance – is the main sticking point. It’s a gender issue because “women take maternity; women move with their spouse; women take care of elders; women tend to be in these roles that require time off” more than men do, Dr. Fromme said.

Until the board releases its data, the gender breakdown of the denials and the degree to which practice gaps due to such issues led to them is unknown. There’s concern that women have been unfairly penalized.

The storm was set off on the discussion board this summer by stories from physicians such as Chandani DeZure, MD, a pediatric hospitalist currently working in the neonatal ICU at Stanford (Calif.) University. She was denied a seat at the table in November, appealed, and was denied again.

She was a full-time pediatric hospitalist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, from 2014, when she graduated residency, until Oct. 2018, when her husband, also a doctor, was offered a promising research position in California, and “we decided to take it,” Dr. DeZure said.

They moved to California with their young son in November. Dr. DeZure got her California medical license in 6 weeks, was hired by Stanford in January, and started her new postion in mid-April.

Because of the move, she worked only 3.5 years in the board’s 4 year practice window, but, as is common with young physicians, that time was spent in direct patient care, for a total of over 6,000 hours.

“How is that not good enough? How is a person that worked 500 hours with patients for 4 years” – for a total of 2,000 hours – “better qualified than someone who worked 100% for 3 and a half years? Nobody is saying there shouldn’t be a standard, but the standard has to be reasonable,” Dr. DeZure said.

“Illegal regardless of intent”

It’s situations like Dr. DeZure’s that led to the petition. One of demands is that ABP “revise the practice pathway criteria to be more inclusive of applicants with interrupted practice and varied clinical experience, to include clear-cut parameters rather than considering these applications on a closed-door ‘case-by-case basis...at the discretion of the ABP.’ ” Also, the petition asks the board to “clarify the appeals process and improve responsiveness to appeals and inquiries regarding denials.”

As ABP noted in its statement, however, the major demand is that the board “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias is present.” The petition noted that signers “do not suspect intentional bias on the part of the ABP; however, if gender bias is present it is unethical and potentially illegal regardless of intent.”

For now, the perception is that the board has “a hard 48-month rule” with not many exceptions; there are people who are “very concerned that, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t have children for 4 years because I won’t be able to sit for the boards.’ No one should ever have to have that in their head,” Dr. Fromme said. At this point, it seems that 3 months off for maternity is being grandfathered in, but perhaps not 6 months for a second child; no one knows for sure.

Dr. DeZure, meanwhile, continues to study for the board exam, just in case.

Looking back over the past year, she said “I could have somehow picked up one shift a week moonlighting that would have kept me eligible, but the [board] didn’t respond to me” when contacted about her situation during the California move.

“The other option was for me was to live cross country from my husband with a small child,” she said.

More than 1,625 pediatricians have applied to take the first pediatric hospitalist certification exam in November 2019, and approximately 93% of them have been accepted, according to a statement from the American Board of Pediatrics.

It was the rejection of the 7%, however, that set off a firestorm on the electronic discussion board for American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) hospital medicine this summer, and led to a petition to the board to revise its eligibility requirements, ensure that the requirements are fair to women, and bring transparency to its decision process. The petition has more than 1,400 signatures.

Seattle Children’s Hospital and Yale New Haven (Conn.) Children’s Hospital have both said they will not consider board certification in hiring decisions until the situation is resolved.

The American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) declined an interview request pending its formal response to the Aug. 6 petition, but in a statement to this news organization, executive vice president Suzanne Woods, MD, said, “The percentage of women and men meeting the eligibility requirements for the exam did not differ. We stress this point because a concern about possible gender bias appears to have been the principal reason for this ... petition, and we wanted to offer immediate reassurance that no unintended bias has occurred.”

“We are carefully considering the requests and will release detailed data to hospitalists on the AAP’s [pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) electronic discussion board] ... and on the ABP’s website. We are conferring with ABP PHM subboard members as well as leaders from our volunteer community. We expect to provide a thoughtful response within the next 3 weeks,” Dr. Woods said in the Aug. 15 statement.

“Case-by-case” exceptions

The backstory is that, for better or worse depending on who you talk to, pediatric hospital medicine is becoming a board certified subspecialty. A fellowship will be required to sit for the exam after a few years, which is standard for subspecialties.

What’s generated concern is how the board is grandfathering current pediatric hospitalists into certification via a “practice pathway” until the fellowship requirement takes hold after 2023.

To qualify for the November test, hospitalists had to complete 4 years of full-time practice by June 30, 2019, which has been understood to mean 48 months of continual employment. At least 50% of that time had to be devoted to “professional activities ... related to the care of hospitalized children,” and at least 25% of that “devoted to direct patient care.” Assuming about 2,000 work hours per year, it translated to “450-500 hours” of direct patient care “per year over the most recent four years” to sit for the test, the board said.

“For individuals who have interrupted practice during the most recent four years for family leave or other such circumstances, an exception may be considered if there is substantial prior experience in pediatric hospital medicine. ... Such exceptions are made at the discretion of the ABP and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.” Specific criteria for exceptions were not spelled out.

In the end, there were more than a few surprises when denial letters went out in recent months, and scores of appeals have been filed. There’s “a lot of tension and a lot of confusion” about why some people with practice gaps during the 4 years were approved, but others were denied. There’s been “a lack of transparency on the ABP’s part,” said H. Barrett Fromme, MD, section chief of pediatric hospital medicine and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago.

“The standard has to be reasonable”

There are concerns about the availability of fellowship slots and other issues, but the 4-year rule – instead of averaging clinical hours over 4 or 5 years, for instance – is the main sticking point. It’s a gender issue because “women take maternity; women move with their spouse; women take care of elders; women tend to be in these roles that require time off” more than men do, Dr. Fromme said.

Until the board releases its data, the gender breakdown of the denials and the degree to which practice gaps due to such issues led to them is unknown. There’s concern that women have been unfairly penalized.

The storm was set off on the discussion board this summer by stories from physicians such as Chandani DeZure, MD, a pediatric hospitalist currently working in the neonatal ICU at Stanford (Calif.) University. She was denied a seat at the table in November, appealed, and was denied again.

She was a full-time pediatric hospitalist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, from 2014, when she graduated residency, until Oct. 2018, when her husband, also a doctor, was offered a promising research position in California, and “we decided to take it,” Dr. DeZure said.

They moved to California with their young son in November. Dr. DeZure got her California medical license in 6 weeks, was hired by Stanford in January, and started her new postion in mid-April.

Because of the move, she worked only 3.5 years in the board’s 4 year practice window, but, as is common with young physicians, that time was spent in direct patient care, for a total of over 6,000 hours.

“How is that not good enough? How is a person that worked 500 hours with patients for 4 years” – for a total of 2,000 hours – “better qualified than someone who worked 100% for 3 and a half years? Nobody is saying there shouldn’t be a standard, but the standard has to be reasonable,” Dr. DeZure said.

“Illegal regardless of intent”

It’s situations like Dr. DeZure’s that led to the petition. One of demands is that ABP “revise the practice pathway criteria to be more inclusive of applicants with interrupted practice and varied clinical experience, to include clear-cut parameters rather than considering these applications on a closed-door ‘case-by-case basis...at the discretion of the ABP.’ ” Also, the petition asks the board to “clarify the appeals process and improve responsiveness to appeals and inquiries regarding denials.”

As ABP noted in its statement, however, the major demand is that the board “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias is present.” The petition noted that signers “do not suspect intentional bias on the part of the ABP; however, if gender bias is present it is unethical and potentially illegal regardless of intent.”

For now, the perception is that the board has “a hard 48-month rule” with not many exceptions; there are people who are “very concerned that, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t have children for 4 years because I won’t be able to sit for the boards.’ No one should ever have to have that in their head,” Dr. Fromme said. At this point, it seems that 3 months off for maternity is being grandfathered in, but perhaps not 6 months for a second child; no one knows for sure.

Dr. DeZure, meanwhile, continues to study for the board exam, just in case.

Looking back over the past year, she said “I could have somehow picked up one shift a week moonlighting that would have kept me eligible, but the [board] didn’t respond to me” when contacted about her situation during the California move.

“The other option was for me was to live cross country from my husband with a small child,” she said.

FDA approves baroreflex activation for advanced HF

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Barostim Neo System, an electronic carotid sinus baroreceptor stimulator, for advanced heart failure patients who have a regular heart rhythm, an ejection fraction of 35% or less, and who are not candidates for cardiac resynchronization.

A tiny, unilateral electrode delivers a pulse that decreases sympathetic but increases parasympathetic tone. The effect is that blood vessels relax and production of stress hormones drops. The device is powered by a small generator implanted under the collarbone.

Approval was based on BeAT-HF, a randomized trial with 408 patients on guideline-directed medical therapy with left ventricular ejection fractions at or below 35% and New York Heart Association class III disease.

At 6 months, 125 patients implanted with the device had improved about 14 points more than controls on a quality of life scale, walked about 60 meters farther in 6 minutes, and were more likely to have improved a functional class or two. The benefits corresponded with a drop in the N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide.

Possible complications include infection, low blood pressure, nerve damage, arterial damage, heart failure exacerbation, stroke, and death. Contraindications include certain nervous system disorders, uncontrolled and symptomatic bradycardia, and atherosclerosis or ulcerative carotid plaques near the implant zone, the FDA said.

The system, from CRVx in Minneapolis, received priority review as a breakthrough device. The agency is requiring a phase 4 investigation of its potential to reduce hospitalizations and prolong life.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Barostim Neo System, an electronic carotid sinus baroreceptor stimulator, for advanced heart failure patients who have a regular heart rhythm, an ejection fraction of 35% or less, and who are not candidates for cardiac resynchronization.

A tiny, unilateral electrode delivers a pulse that decreases sympathetic but increases parasympathetic tone. The effect is that blood vessels relax and production of stress hormones drops. The device is powered by a small generator implanted under the collarbone.

Approval was based on BeAT-HF, a randomized trial with 408 patients on guideline-directed medical therapy with left ventricular ejection fractions at or below 35% and New York Heart Association class III disease.

At 6 months, 125 patients implanted with the device had improved about 14 points more than controls on a quality of life scale, walked about 60 meters farther in 6 minutes, and were more likely to have improved a functional class or two. The benefits corresponded with a drop in the N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide.

Possible complications include infection, low blood pressure, nerve damage, arterial damage, heart failure exacerbation, stroke, and death. Contraindications include certain nervous system disorders, uncontrolled and symptomatic bradycardia, and atherosclerosis or ulcerative carotid plaques near the implant zone, the FDA said.

The system, from CRVx in Minneapolis, received priority review as a breakthrough device. The agency is requiring a phase 4 investigation of its potential to reduce hospitalizations and prolong life.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Barostim Neo System, an electronic carotid sinus baroreceptor stimulator, for advanced heart failure patients who have a regular heart rhythm, an ejection fraction of 35% or less, and who are not candidates for cardiac resynchronization.

A tiny, unilateral electrode delivers a pulse that decreases sympathetic but increases parasympathetic tone. The effect is that blood vessels relax and production of stress hormones drops. The device is powered by a small generator implanted under the collarbone.

Approval was based on BeAT-HF, a randomized trial with 408 patients on guideline-directed medical therapy with left ventricular ejection fractions at or below 35% and New York Heart Association class III disease.

At 6 months, 125 patients implanted with the device had improved about 14 points more than controls on a quality of life scale, walked about 60 meters farther in 6 minutes, and were more likely to have improved a functional class or two. The benefits corresponded with a drop in the N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide.

Possible complications include infection, low blood pressure, nerve damage, arterial damage, heart failure exacerbation, stroke, and death. Contraindications include certain nervous system disorders, uncontrolled and symptomatic bradycardia, and atherosclerosis or ulcerative carotid plaques near the implant zone, the FDA said.

The system, from CRVx in Minneapolis, received priority review as a breakthrough device. The agency is requiring a phase 4 investigation of its potential to reduce hospitalizations and prolong life.

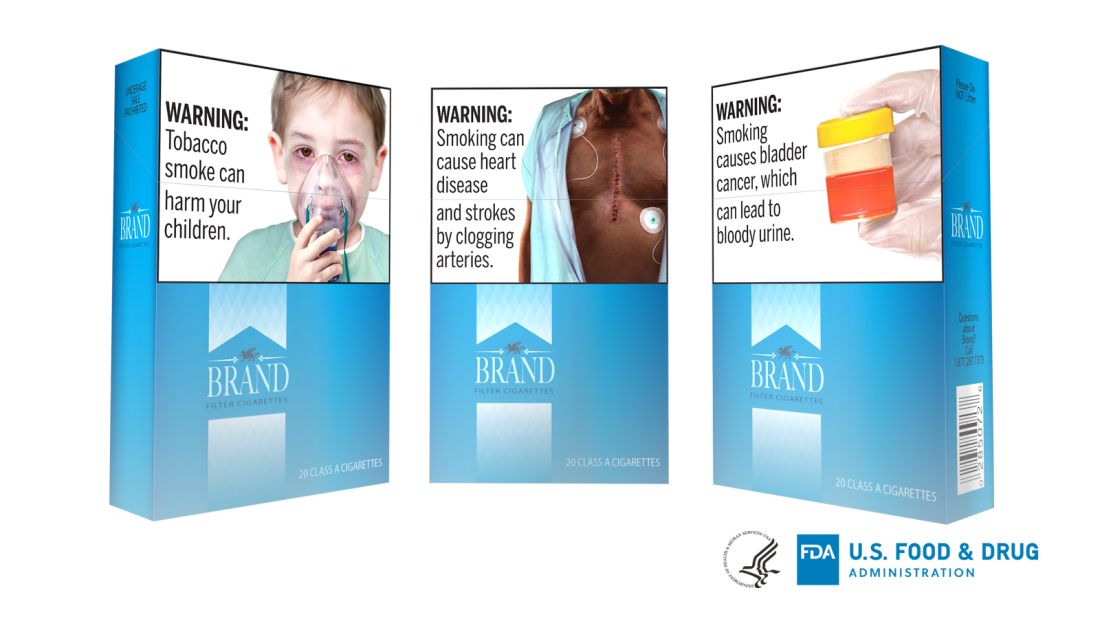

FDA takes another swing at updating cigarette pack warnings

illustrating the harms of smoking, but this could be subjected to legal challenge.

Several years ago, tobacco companies filed a lawsuit, which ultimately shut down a similar proposal.

The warnings focus on lesser-known complications – including diabetes, cataracts, gangrene, stroke, bladder cancer, erectile dysfunction, and obstructive pulmonary disease – and would take up the top half of the front and back of cigarette packs, and at least the top 20% of print advertisements. Each pack and ad would be required to carry 1 of the 13 proposed warnings, according to the announcement.

The approach would be similar to, but not as aggressive as Canada’s. For years, cigarettes packs sold in Canada have included disturbing photographs of diseased lungs, rotted teeth, and dying patients. The lasting impact of such imagery has been demonstrated in the literature (for example, Am J Prev Med. 2007 Mar;32[3]:202-9).

The new proposal is the FDA’s second attempt to enact something comparable in the United States, after being directed to do so by the Tobacco Control Act of 2009.

The first effort to add strong, illustrated warnings to cigarette packs was widely backed by medical groups, but challenged in the courts by R.J. Reynolds and other tobacco companies, and blocked on appeal in 2012 as an abridgment of commercial free speech. The federal government dropped the case in 2013.

The American Lung Association and other public health groups subsequently sued the FDA in 2016 to enact the Tobacco Act mandate. Subsequently, a federal judge ordered the agency to publish a new rule by August 2019, and issue a final rule in March 2020.

This time around, the FDA “took the necessary time to get these new proposed warnings right ... based on – and within the limits of – both science and the law,” the agency said. The new images, though graphic, are less disturbing than those used in Canada and the agency’s previous proposals, which included an apparent corpse with a sternotomy. The 1-800-Quit-Now cessation hotline number, which was a sticking point in the 2012 ruling, has also been dropped.

When asked about the new efforts, R.J. Reynolds spokesperson Kaelan Hollon said, “We are carefully reviewing FDA’s latest proposal for graphic warnings on cigarettes. We firmly support public awareness of the harms of smoking cigarettes, but the manner in which those messages are delivered to the public cannot run afoul of the First Amendment protections that apply to all speakers, including cigarette manufacturers.”

Warnings on U.S. cigarettes haven’t changed since 1984, when the risks of lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and pregnancy complications were added to the side of cigarette packs. With time, the FDA said the surgeon general’s warnings have become “virtually invisible” to consumers.

The American Lung Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and other plaintiffs in the 2016 suit called the new proposal a “dramatic improvement” over the current situation and “long overdue” in a joint statement on Aug. 15.

Although rates have declined substantially in recent decades, about 34.3 million U.S. adults and almost 1.4 million teenagers still smoke. The habit kills about a half million Americans every year, at a health cost of more than $300 billion, the FDA said.

Comments on the proposed rule are being accepted through Oct. 15. The agency is open to suggestions for alternative text and images.

illustrating the harms of smoking, but this could be subjected to legal challenge.

Several years ago, tobacco companies filed a lawsuit, which ultimately shut down a similar proposal.

The warnings focus on lesser-known complications – including diabetes, cataracts, gangrene, stroke, bladder cancer, erectile dysfunction, and obstructive pulmonary disease – and would take up the top half of the front and back of cigarette packs, and at least the top 20% of print advertisements. Each pack and ad would be required to carry 1 of the 13 proposed warnings, according to the announcement.

The approach would be similar to, but not as aggressive as Canada’s. For years, cigarettes packs sold in Canada have included disturbing photographs of diseased lungs, rotted teeth, and dying patients. The lasting impact of such imagery has been demonstrated in the literature (for example, Am J Prev Med. 2007 Mar;32[3]:202-9).

The new proposal is the FDA’s second attempt to enact something comparable in the United States, after being directed to do so by the Tobacco Control Act of 2009.

The first effort to add strong, illustrated warnings to cigarette packs was widely backed by medical groups, but challenged in the courts by R.J. Reynolds and other tobacco companies, and blocked on appeal in 2012 as an abridgment of commercial free speech. The federal government dropped the case in 2013.

The American Lung Association and other public health groups subsequently sued the FDA in 2016 to enact the Tobacco Act mandate. Subsequently, a federal judge ordered the agency to publish a new rule by August 2019, and issue a final rule in March 2020.

This time around, the FDA “took the necessary time to get these new proposed warnings right ... based on – and within the limits of – both science and the law,” the agency said. The new images, though graphic, are less disturbing than those used in Canada and the agency’s previous proposals, which included an apparent corpse with a sternotomy. The 1-800-Quit-Now cessation hotline number, which was a sticking point in the 2012 ruling, has also been dropped.

When asked about the new efforts, R.J. Reynolds spokesperson Kaelan Hollon said, “We are carefully reviewing FDA’s latest proposal for graphic warnings on cigarettes. We firmly support public awareness of the harms of smoking cigarettes, but the manner in which those messages are delivered to the public cannot run afoul of the First Amendment protections that apply to all speakers, including cigarette manufacturers.”

Warnings on U.S. cigarettes haven’t changed since 1984, when the risks of lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and pregnancy complications were added to the side of cigarette packs. With time, the FDA said the surgeon general’s warnings have become “virtually invisible” to consumers.

The American Lung Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and other plaintiffs in the 2016 suit called the new proposal a “dramatic improvement” over the current situation and “long overdue” in a joint statement on Aug. 15.

Although rates have declined substantially in recent decades, about 34.3 million U.S. adults and almost 1.4 million teenagers still smoke. The habit kills about a half million Americans every year, at a health cost of more than $300 billion, the FDA said.

Comments on the proposed rule are being accepted through Oct. 15. The agency is open to suggestions for alternative text and images.

illustrating the harms of smoking, but this could be subjected to legal challenge.

Several years ago, tobacco companies filed a lawsuit, which ultimately shut down a similar proposal.

The warnings focus on lesser-known complications – including diabetes, cataracts, gangrene, stroke, bladder cancer, erectile dysfunction, and obstructive pulmonary disease – and would take up the top half of the front and back of cigarette packs, and at least the top 20% of print advertisements. Each pack and ad would be required to carry 1 of the 13 proposed warnings, according to the announcement.

The approach would be similar to, but not as aggressive as Canada’s. For years, cigarettes packs sold in Canada have included disturbing photographs of diseased lungs, rotted teeth, and dying patients. The lasting impact of such imagery has been demonstrated in the literature (for example, Am J Prev Med. 2007 Mar;32[3]:202-9).

The new proposal is the FDA’s second attempt to enact something comparable in the United States, after being directed to do so by the Tobacco Control Act of 2009.

The first effort to add strong, illustrated warnings to cigarette packs was widely backed by medical groups, but challenged in the courts by R.J. Reynolds and other tobacco companies, and blocked on appeal in 2012 as an abridgment of commercial free speech. The federal government dropped the case in 2013.

The American Lung Association and other public health groups subsequently sued the FDA in 2016 to enact the Tobacco Act mandate. Subsequently, a federal judge ordered the agency to publish a new rule by August 2019, and issue a final rule in March 2020.

This time around, the FDA “took the necessary time to get these new proposed warnings right ... based on – and within the limits of – both science and the law,” the agency said. The new images, though graphic, are less disturbing than those used in Canada and the agency’s previous proposals, which included an apparent corpse with a sternotomy. The 1-800-Quit-Now cessation hotline number, which was a sticking point in the 2012 ruling, has also been dropped.

When asked about the new efforts, R.J. Reynolds spokesperson Kaelan Hollon said, “We are carefully reviewing FDA’s latest proposal for graphic warnings on cigarettes. We firmly support public awareness of the harms of smoking cigarettes, but the manner in which those messages are delivered to the public cannot run afoul of the First Amendment protections that apply to all speakers, including cigarette manufacturers.”

Warnings on U.S. cigarettes haven’t changed since 1984, when the risks of lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and pregnancy complications were added to the side of cigarette packs. With time, the FDA said the surgeon general’s warnings have become “virtually invisible” to consumers.

The American Lung Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and other plaintiffs in the 2016 suit called the new proposal a “dramatic improvement” over the current situation and “long overdue” in a joint statement on Aug. 15.

Although rates have declined substantially in recent decades, about 34.3 million U.S. adults and almost 1.4 million teenagers still smoke. The habit kills about a half million Americans every year, at a health cost of more than $300 billion, the FDA said.

Comments on the proposed rule are being accepted through Oct. 15. The agency is open to suggestions for alternative text and images.

How to nearly eliminate CLABSIs in children’s hospitals

SEATTLE – Levine Children’s Hospital, in Charlotte, N.C., dropped its central line–associated bloodstream infection rate from 1.13 per 1,000 line days to 0.67 in just a few months, with a mix of common sense steps and public accountability.

Levine Children’s was at about the 50th percentile for CLABSIs, compared with other children’s hospitals, but dropped to the 10th percentile after the changes. There were 21 CLABSIs in 2017, but only 12 in 2018. The hospital went 6 straight months without a CLABSI after the changes were made. The efforts saved about $300,000 and 63 patient days.

“We really had great success,” said Kayla S. Koch, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s, who presented the findings at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Hospital units had been working to reduce CLABSIs, but they were each doing their own thing. “Many of our units were already dabbling, so we just sort of brought them together. We standardized the process and got everyone on the same page,” said copresenter Ketan P. Nadkarni, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s.

It wasn’t hard to get buy-in. “I don’t think the units were aware that everyone was doing it differently,” and were on board once the problem was explained. Also, using the same approach throughout the hospital made it easier for nurses and physicians moving between units, he said.

Each morning, the nurse supervisor and patient nurse would partner up at the bedside to check that central venous lines were set up correctly. They examined the alcohol disinfectant caps to make sure they were clean; determined that children were getting chlorhexidine gluconate baths; checked the dressings for bleeding and soiling; noted in the electronic medical record why the patient had a central line; and discussed with hospitalists if it were still needed. Problems were addressed immediately.

These quality processes were all tracked on wall racks placed in plain sight on each unit, including the neonatal and pediatric ICUs. Each central line patient had a card that listed what needed to be done, with a green stripe on one side and a red stripe on the other. If everything was done right, the green side faced out; if even one thing was done wrong, the red side was displayed, for all to see. It brought accountability to the process, the presenters said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The wall rack also had the central line audit schedule, plus diagrams that showed every failed item, the reason for it, and the unit’s compliance rate. Anyone walking by could see at a glance how the unit was doing that day and overall.

The number of dressing options was reduced from 10 to 2, a SorbaView SHIELD and a Tegaderm-like dressing, which made it easier to standardize the efforts. A protocol also was put in place to reinforce oozing dressings, instead of automatically changing them. “We were doing too many changes,” Dr. Koch said.

Compliance with the bundle was almost 90%. Staff “really got into it, and it was great to see,” she said.

The “initial success was almost unexpected, and so dramatic.” The goal now is to sustain the improvements, and roll them out to radiology and other places were central lines are placed, Dr. Nadkarni said.

There was no external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Levine Children’s Hospital, in Charlotte, N.C., dropped its central line–associated bloodstream infection rate from 1.13 per 1,000 line days to 0.67 in just a few months, with a mix of common sense steps and public accountability.

Levine Children’s was at about the 50th percentile for CLABSIs, compared with other children’s hospitals, but dropped to the 10th percentile after the changes. There were 21 CLABSIs in 2017, but only 12 in 2018. The hospital went 6 straight months without a CLABSI after the changes were made. The efforts saved about $300,000 and 63 patient days.

“We really had great success,” said Kayla S. Koch, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s, who presented the findings at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Hospital units had been working to reduce CLABSIs, but they were each doing their own thing. “Many of our units were already dabbling, so we just sort of brought them together. We standardized the process and got everyone on the same page,” said copresenter Ketan P. Nadkarni, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s.

It wasn’t hard to get buy-in. “I don’t think the units were aware that everyone was doing it differently,” and were on board once the problem was explained. Also, using the same approach throughout the hospital made it easier for nurses and physicians moving between units, he said.

Each morning, the nurse supervisor and patient nurse would partner up at the bedside to check that central venous lines were set up correctly. They examined the alcohol disinfectant caps to make sure they were clean; determined that children were getting chlorhexidine gluconate baths; checked the dressings for bleeding and soiling; noted in the electronic medical record why the patient had a central line; and discussed with hospitalists if it were still needed. Problems were addressed immediately.

These quality processes were all tracked on wall racks placed in plain sight on each unit, including the neonatal and pediatric ICUs. Each central line patient had a card that listed what needed to be done, with a green stripe on one side and a red stripe on the other. If everything was done right, the green side faced out; if even one thing was done wrong, the red side was displayed, for all to see. It brought accountability to the process, the presenters said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The wall rack also had the central line audit schedule, plus diagrams that showed every failed item, the reason for it, and the unit’s compliance rate. Anyone walking by could see at a glance how the unit was doing that day and overall.

The number of dressing options was reduced from 10 to 2, a SorbaView SHIELD and a Tegaderm-like dressing, which made it easier to standardize the efforts. A protocol also was put in place to reinforce oozing dressings, instead of automatically changing them. “We were doing too many changes,” Dr. Koch said.

Compliance with the bundle was almost 90%. Staff “really got into it, and it was great to see,” she said.

The “initial success was almost unexpected, and so dramatic.” The goal now is to sustain the improvements, and roll them out to radiology and other places were central lines are placed, Dr. Nadkarni said.

There was no external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Levine Children’s Hospital, in Charlotte, N.C., dropped its central line–associated bloodstream infection rate from 1.13 per 1,000 line days to 0.67 in just a few months, with a mix of common sense steps and public accountability.

Levine Children’s was at about the 50th percentile for CLABSIs, compared with other children’s hospitals, but dropped to the 10th percentile after the changes. There were 21 CLABSIs in 2017, but only 12 in 2018. The hospital went 6 straight months without a CLABSI after the changes were made. The efforts saved about $300,000 and 63 patient days.

“We really had great success,” said Kayla S. Koch, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s, who presented the findings at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Hospital units had been working to reduce CLABSIs, but they were each doing their own thing. “Many of our units were already dabbling, so we just sort of brought them together. We standardized the process and got everyone on the same page,” said copresenter Ketan P. Nadkarni, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s.

It wasn’t hard to get buy-in. “I don’t think the units were aware that everyone was doing it differently,” and were on board once the problem was explained. Also, using the same approach throughout the hospital made it easier for nurses and physicians moving between units, he said.

Each morning, the nurse supervisor and patient nurse would partner up at the bedside to check that central venous lines were set up correctly. They examined the alcohol disinfectant caps to make sure they were clean; determined that children were getting chlorhexidine gluconate baths; checked the dressings for bleeding and soiling; noted in the electronic medical record why the patient had a central line; and discussed with hospitalists if it were still needed. Problems were addressed immediately.

These quality processes were all tracked on wall racks placed in plain sight on each unit, including the neonatal and pediatric ICUs. Each central line patient had a card that listed what needed to be done, with a green stripe on one side and a red stripe on the other. If everything was done right, the green side faced out; if even one thing was done wrong, the red side was displayed, for all to see. It brought accountability to the process, the presenters said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The wall rack also had the central line audit schedule, plus diagrams that showed every failed item, the reason for it, and the unit’s compliance rate. Anyone walking by could see at a glance how the unit was doing that day and overall.

The number of dressing options was reduced from 10 to 2, a SorbaView SHIELD and a Tegaderm-like dressing, which made it easier to standardize the efforts. A protocol also was put in place to reinforce oozing dressings, instead of automatically changing them. “We were doing too many changes,” Dr. Koch said.

Compliance with the bundle was almost 90%. Staff “really got into it, and it was great to see,” she said.

The “initial success was almost unexpected, and so dramatic.” The goal now is to sustain the improvements, and roll them out to radiology and other places were central lines are placed, Dr. Nadkarni said.

There was no external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2019

Procalcitonin advocated to help rule out bacterial infections

SEATTLE – Procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection, rises and peaks sooner than C-reactive protein (CRP), and is especially useful to help rule out invasive bacterial infections in young infants and pediatric community acquired pneumonia due to typical bacteria, according to a presentation at the 2019 Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference.

It’s “excellent for identifying low risk patients” and has the potential to decrease lumbar punctures and antibiotic exposure, but “the specificity isn’t great,” so there’s the potential for false positives, said Russell McCulloh, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

There was great interest in procalcitonin at the meeting; the presentation room was packed, with a line out the door. It’s used mostly in Europe at this point. Testing is available in many U.S. hospitals, but a large majority of audience members, when polled, said they don’t currently use it in clinical practice, and that it’s not a part of diagnostic algorithms at their institutions.

Levels of procalcitonin, a calcitonin precursor normally produced by the thyroid, are low or undetectable in healthy people, but inflammation, be it from infectious or noninfectious causes, triggers production by parenchymal cells throughout the body.

Levels began to rise as early as 2.5 hours after healthy subjects in one study were injected with bacterial endotoxins, and peaked as early as 6 hours; CRP, in contrast, started to rise after 12 hours, and peaked at 30 hours. Procalcitonin levels also seem to correlate with bacterial load and severity of infection, said Nivedita Srinivas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University (J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016 Dec;5[4]:162-71).

Due to time, the presenters focused their talk on community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in young infants, meaning essentially bacteremia and meningitis.

Different studies use different cutoffs, but a procalcitonin below, for instance, 0.5 ng/mL is “certainly more sensitive [for IBI] than any single biomarker we currently use,” including CRP, white blood cells, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC). “If it’s negative, you’re really confident it’s negative,” but “a positive test does not necessarily indicate the presence of IBI,” Dr. McCulloh said (Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130[5]:815-22).

“Procalcitonin works really well as part of a validated step-wise rule” that includes, for instance, CRP and ANC; “I think that’s where its utility is. On its own, it is not a substitute for you examining the patient and doing your basic risk stratification, but it may enhance your decision making incrementally above what we currently have,” he said.

Meanwhile, in a study of 532 children a median age of 2.4 years with radiographically confirmed CAP, procalcitonin levels were a median of 6.1 ng/mL in children whose pneumonia was caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or other typical bacteria, and no child infected with typical bacteria had a level under 0.1 ng/mL. Below that level, “you can be very sure you do not have typical bacteria pneumonia,” said Marie Wang, MD, also a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018 Feb 19;7[1]:46-53).

As procalcitonin levels went up, the likelihood of having bacterial pneumonia increased; at 2 ng/mL, 26% of subjects were infected with typical bacteria, “but even in that group, 58% still had viral infection, so you are still detecting a lot of viral” disease, she said.

Prolcalcitonin-guided therapy – antibiotics until patients fall below a level of 0.25 ng/ml, for instance – has also been associated with decreased antibiotic exposure (Respir Med. 2011 Dec;105[12]:1939-45).

The speakers had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection, rises and peaks sooner than C-reactive protein (CRP), and is especially useful to help rule out invasive bacterial infections in young infants and pediatric community acquired pneumonia due to typical bacteria, according to a presentation at the 2019 Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference.

It’s “excellent for identifying low risk patients” and has the potential to decrease lumbar punctures and antibiotic exposure, but “the specificity isn’t great,” so there’s the potential for false positives, said Russell McCulloh, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

There was great interest in procalcitonin at the meeting; the presentation room was packed, with a line out the door. It’s used mostly in Europe at this point. Testing is available in many U.S. hospitals, but a large majority of audience members, when polled, said they don’t currently use it in clinical practice, and that it’s not a part of diagnostic algorithms at their institutions.

Levels of procalcitonin, a calcitonin precursor normally produced by the thyroid, are low or undetectable in healthy people, but inflammation, be it from infectious or noninfectious causes, triggers production by parenchymal cells throughout the body.

Levels began to rise as early as 2.5 hours after healthy subjects in one study were injected with bacterial endotoxins, and peaked as early as 6 hours; CRP, in contrast, started to rise after 12 hours, and peaked at 30 hours. Procalcitonin levels also seem to correlate with bacterial load and severity of infection, said Nivedita Srinivas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University (J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016 Dec;5[4]:162-71).

Due to time, the presenters focused their talk on community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in young infants, meaning essentially bacteremia and meningitis.

Different studies use different cutoffs, but a procalcitonin below, for instance, 0.5 ng/mL is “certainly more sensitive [for IBI] than any single biomarker we currently use,” including CRP, white blood cells, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC). “If it’s negative, you’re really confident it’s negative,” but “a positive test does not necessarily indicate the presence of IBI,” Dr. McCulloh said (Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130[5]:815-22).

“Procalcitonin works really well as part of a validated step-wise rule” that includes, for instance, CRP and ANC; “I think that’s where its utility is. On its own, it is not a substitute for you examining the patient and doing your basic risk stratification, but it may enhance your decision making incrementally above what we currently have,” he said.

Meanwhile, in a study of 532 children a median age of 2.4 years with radiographically confirmed CAP, procalcitonin levels were a median of 6.1 ng/mL in children whose pneumonia was caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or other typical bacteria, and no child infected with typical bacteria had a level under 0.1 ng/mL. Below that level, “you can be very sure you do not have typical bacteria pneumonia,” said Marie Wang, MD, also a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018 Feb 19;7[1]:46-53).

As procalcitonin levels went up, the likelihood of having bacterial pneumonia increased; at 2 ng/mL, 26% of subjects were infected with typical bacteria, “but even in that group, 58% still had viral infection, so you are still detecting a lot of viral” disease, she said.

Prolcalcitonin-guided therapy – antibiotics until patients fall below a level of 0.25 ng/ml, for instance – has also been associated with decreased antibiotic exposure (Respir Med. 2011 Dec;105[12]:1939-45).

The speakers had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection, rises and peaks sooner than C-reactive protein (CRP), and is especially useful to help rule out invasive bacterial infections in young infants and pediatric community acquired pneumonia due to typical bacteria, according to a presentation at the 2019 Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference.

It’s “excellent for identifying low risk patients” and has the potential to decrease lumbar punctures and antibiotic exposure, but “the specificity isn’t great,” so there’s the potential for false positives, said Russell McCulloh, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

There was great interest in procalcitonin at the meeting; the presentation room was packed, with a line out the door. It’s used mostly in Europe at this point. Testing is available in many U.S. hospitals, but a large majority of audience members, when polled, said they don’t currently use it in clinical practice, and that it’s not a part of diagnostic algorithms at their institutions.

Levels of procalcitonin, a calcitonin precursor normally produced by the thyroid, are low or undetectable in healthy people, but inflammation, be it from infectious or noninfectious causes, triggers production by parenchymal cells throughout the body.

Levels began to rise as early as 2.5 hours after healthy subjects in one study were injected with bacterial endotoxins, and peaked as early as 6 hours; CRP, in contrast, started to rise after 12 hours, and peaked at 30 hours. Procalcitonin levels also seem to correlate with bacterial load and severity of infection, said Nivedita Srinivas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University (J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016 Dec;5[4]:162-71).

Due to time, the presenters focused their talk on community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in young infants, meaning essentially bacteremia and meningitis.

Different studies use different cutoffs, but a procalcitonin below, for instance, 0.5 ng/mL is “certainly more sensitive [for IBI] than any single biomarker we currently use,” including CRP, white blood cells, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC). “If it’s negative, you’re really confident it’s negative,” but “a positive test does not necessarily indicate the presence of IBI,” Dr. McCulloh said (Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130[5]:815-22).

“Procalcitonin works really well as part of a validated step-wise rule” that includes, for instance, CRP and ANC; “I think that’s where its utility is. On its own, it is not a substitute for you examining the patient and doing your basic risk stratification, but it may enhance your decision making incrementally above what we currently have,” he said.

Meanwhile, in a study of 532 children a median age of 2.4 years with radiographically confirmed CAP, procalcitonin levels were a median of 6.1 ng/mL in children whose pneumonia was caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or other typical bacteria, and no child infected with typical bacteria had a level under 0.1 ng/mL. Below that level, “you can be very sure you do not have typical bacteria pneumonia,” said Marie Wang, MD, also a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018 Feb 19;7[1]:46-53).

As procalcitonin levels went up, the likelihood of having bacterial pneumonia increased; at 2 ng/mL, 26% of subjects were infected with typical bacteria, “but even in that group, 58% still had viral infection, so you are still detecting a lot of viral” disease, she said.

Prolcalcitonin-guided therapy – antibiotics until patients fall below a level of 0.25 ng/ml, for instance – has also been associated with decreased antibiotic exposure (Respir Med. 2011 Dec;105[12]:1939-45).

The speakers had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PHM 2019

In newborns, concentrated urine helps rule out UTI

SEATTLE – according to investigators at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

The researchers found that urine testing negative for nitrites with a specific gravity above 1.015 in children up to 2 months old had a sensitivity of 53% for ruling out UTIs, but that urine with a specific gravity below that mark had a sensitivity of just 14%. The finding “should be taken into account when interpreting nitrite results ... in this high-risk population,” they concluded.

Bacteria in the bladder convert nitrates to nitrites, so positive results are pretty much pathognomonic for UTIs, with a specificity of nearly 100%, according to the researchers.

Negative results, however, don’t reliably rule out infection, and are even less reliable in infants because they urinate frequently, which means they usually flush out bacteria before they have enough time to make the conversion, which takes several hours, they said.

The lead investigator Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston, said he had a hunch that negative results might be more reliable when newborns urinate less frequently and have more concentrated urine.

He and his team reviewed data collected on 413 infants up to 2 months old who were admitted for fever workup and treated for UTIs both in the hospital and after discharge. Nitrite results were stratified by urine concentration. A specific gravity of 1.015 was used as the cutoff between concentrated and dilute urine, which was “midway between the parameters reported” in every urinalysis, Dr. Parlar-Chun said.

Although the sensitivity of concentrated urine was only 53%, “it’s a stark difference from” the 14% in dilute urine, he said.“You should take a look at specific gravity to interpret nitrites. If urine is concentrated, you have [more confidence] that you don’t have a UTI if you’re negative. It’s better than taking [nitrites] at face value.”

The subjects were 31 days old, on average, and 62% were boys; 112 had a specific gravity above 1.015, and 301 below.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Parlar-Chun didn’t have any disclosures.

SEATTLE – according to investigators at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

The researchers found that urine testing negative for nitrites with a specific gravity above 1.015 in children up to 2 months old had a sensitivity of 53% for ruling out UTIs, but that urine with a specific gravity below that mark had a sensitivity of just 14%. The finding “should be taken into account when interpreting nitrite results ... in this high-risk population,” they concluded.

Bacteria in the bladder convert nitrates to nitrites, so positive results are pretty much pathognomonic for UTIs, with a specificity of nearly 100%, according to the researchers.

Negative results, however, don’t reliably rule out infection, and are even less reliable in infants because they urinate frequently, which means they usually flush out bacteria before they have enough time to make the conversion, which takes several hours, they said.

The lead investigator Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston, said he had a hunch that negative results might be more reliable when newborns urinate less frequently and have more concentrated urine.

He and his team reviewed data collected on 413 infants up to 2 months old who were admitted for fever workup and treated for UTIs both in the hospital and after discharge. Nitrite results were stratified by urine concentration. A specific gravity of 1.015 was used as the cutoff between concentrated and dilute urine, which was “midway between the parameters reported” in every urinalysis, Dr. Parlar-Chun said.

Although the sensitivity of concentrated urine was only 53%, “it’s a stark difference from” the 14% in dilute urine, he said.“You should take a look at specific gravity to interpret nitrites. If urine is concentrated, you have [more confidence] that you don’t have a UTI if you’re negative. It’s better than taking [nitrites] at face value.”

The subjects were 31 days old, on average, and 62% were boys; 112 had a specific gravity above 1.015, and 301 below.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Parlar-Chun didn’t have any disclosures.

SEATTLE – according to investigators at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

The researchers found that urine testing negative for nitrites with a specific gravity above 1.015 in children up to 2 months old had a sensitivity of 53% for ruling out UTIs, but that urine with a specific gravity below that mark had a sensitivity of just 14%. The finding “should be taken into account when interpreting nitrite results ... in this high-risk population,” they concluded.

Bacteria in the bladder convert nitrates to nitrites, so positive results are pretty much pathognomonic for UTIs, with a specificity of nearly 100%, according to the researchers.

Negative results, however, don’t reliably rule out infection, and are even less reliable in infants because they urinate frequently, which means they usually flush out bacteria before they have enough time to make the conversion, which takes several hours, they said.

The lead investigator Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston, said he had a hunch that negative results might be more reliable when newborns urinate less frequently and have more concentrated urine.

He and his team reviewed data collected on 413 infants up to 2 months old who were admitted for fever workup and treated for UTIs both in the hospital and after discharge. Nitrite results were stratified by urine concentration. A specific gravity of 1.015 was used as the cutoff between concentrated and dilute urine, which was “midway between the parameters reported” in every urinalysis, Dr. Parlar-Chun said.