User login

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems had been increasingly focused on expanding care delivery through clinical video telehealth (CVT) services.1-3 These modalities offer clinicians and patients opportunities to interact without needing face-to-face visits. CVT services offer significant advantages to patients who encounter challenges accessing traditional face-to-face services, including those living in rural or underserved areas, individuals with mobility limitations, and those with difficulty attending appointments due to work or caregiving commitments.4 The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the expansion of CVT services to mitigate the spread of the virus.1

Despite its evident advantages, widespread adoption of CVT has encountered resistance.2 Physicians have frequently expressed concerns about the reliability and functionality of CVT platforms for scheduled encounters and frustration with inadequate training.4-6 Additionally, there is a lack trust in the technology, as physicians are unfamiliar with reimbursement or workload capture associated with CVT. Physicians have concerns that telecommunication may diminish the intangible aspects of the “art of medicine.”4 As a result, the implementation of telehealth services has been inconsistent, with successful adoption limited to specific medical and surgical specialties.4 Only recently have entire departments within major health care systems expressed interest in providing comprehensive CVT services in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides an appropriate setting for assessing clinician perceptions of telehealth services. Since 2003, the VHA has significantly expanded CVT services to eligible veterans and has used the VA Video Connect (VVC) platform since 2018.7-10 Through VVC, VA staff and clinicians may schedule video visits with patients, meet with patients through virtual face-to-face interaction, and share relevant laboratory results and imaging through screen sharing. Prior research has shown increased accessibility to care through VVC. For example, a single-site study demonstrated that VVC implementation for delivering psychotherapies significantly increased CVT encounters from 15% to 85% among veterans with anxiety and/or depression.11

The VA New Mexico Healthcare System (VANMHCS) serves a high volume of veterans living in remote and rural regions and significantly increased its use of CVT during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce in-person visits. Expectedly, this was met with a variety of challenges. Herein, we sought to assess physician perspectives, concerns, and attitudes toward VVC via semistructured interviews. Our hypothesis was that VA physicians may feel uncomfortable with video encounters but recognize the growing importance of such practices providing specialty care to veterans in rural areas.

METHODS

A semistructured interview protocol was created following discussions with physicians from the VANMHCS Medicine Service. Questions were constructed to assess the following domains: overarching views of video telehealth, perceptions of various applications for conducting VVC encounters, and barriers to the broad implementation of video telehealth. A qualitative investigation specialist aided with question development. Two pilot interviews were conducted prior to performing the interviews with the recruited participants to evaluate the quality and delivery of questions.

All VANMHCS physicians who provided outpatient care within the Department of Medicine and had completed ≥ 1 VVC encounter were eligible to participate. Invitations were disseminated via email, and follow-up emails to encourage participation were sent periodically for 2 months following the initial request. Union approval was obtained to interview employees for a research study. In total, 64 physicians were invited and 13 (20%) chose to participate. As the study did not involve assessing medical interventions among patients, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the VANMHCS Institutional Review Board. Physicians who participated in this study were informed that their responses would be used for reporting purposes and could be rescinded at any time.

Data Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted by a single interviewer and recorded using Microsoft Teams. The interviews took place between February 2021 and December 2021 and lasted 5 to 15 minutes, with a mean duration of 9 minutes. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews. Interviewees were encouraged to expand on their responses to structured questions by recounting past experiences with VVC. Recorded audio was additionally transcribed via Microsoft Teams, and the research team reviewed the transcriptions to ensure accuracy.

The tracking and coding of responses to interview questions were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Initially, 5 transcripts were reviewed and responses were assessed by 2 study team members through open coding. All team members examined the 5 coded transcripts to identify differences and reach a consensus for any discrepancies. Based on recommendations from all team members regarding nuanced excerpts of transcripts, 1 study team member coded the remaining interviews. Thematic analysis was subsequently conducted according to the method described by Braun and Clarke.12 Themes were developed both deductively and inductively by reviewing the direct responses to interview questions and identifying emerging patterns of data, respectively. Indicative quotes representing each theme were carefully chosen for reporting.

RESULTS

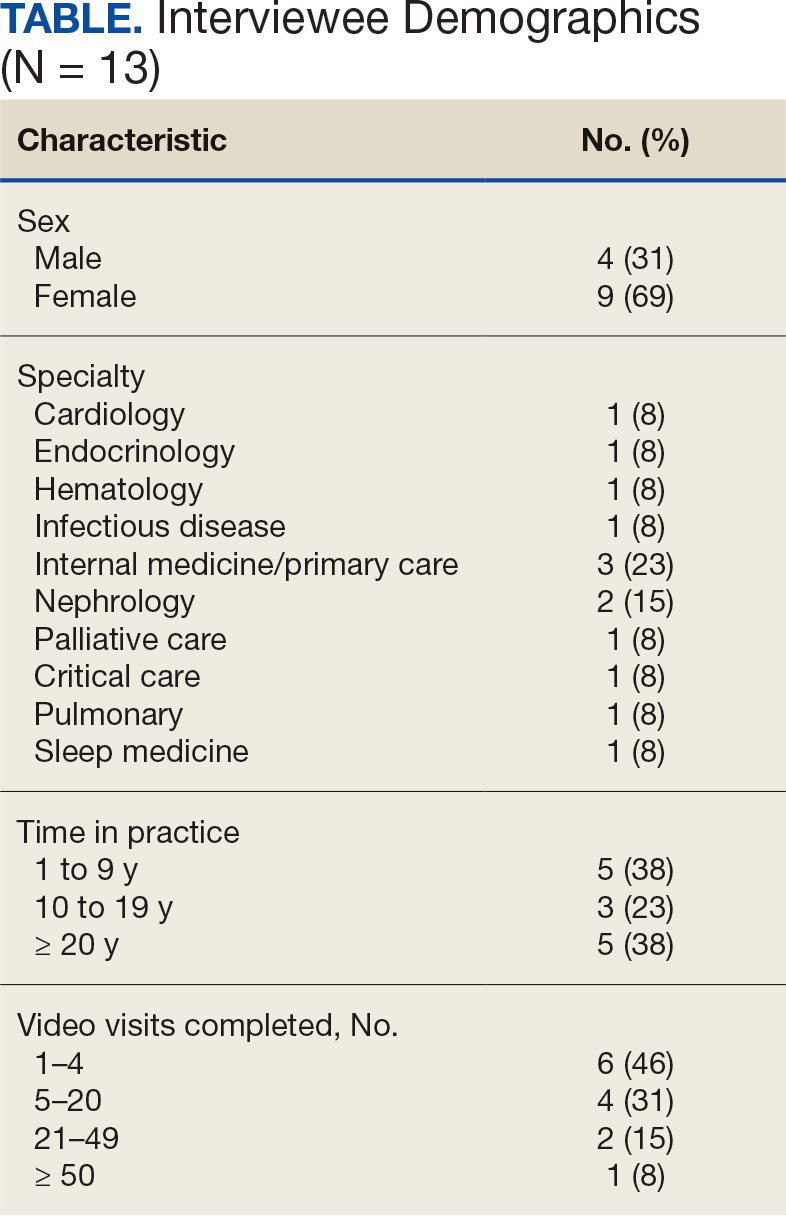

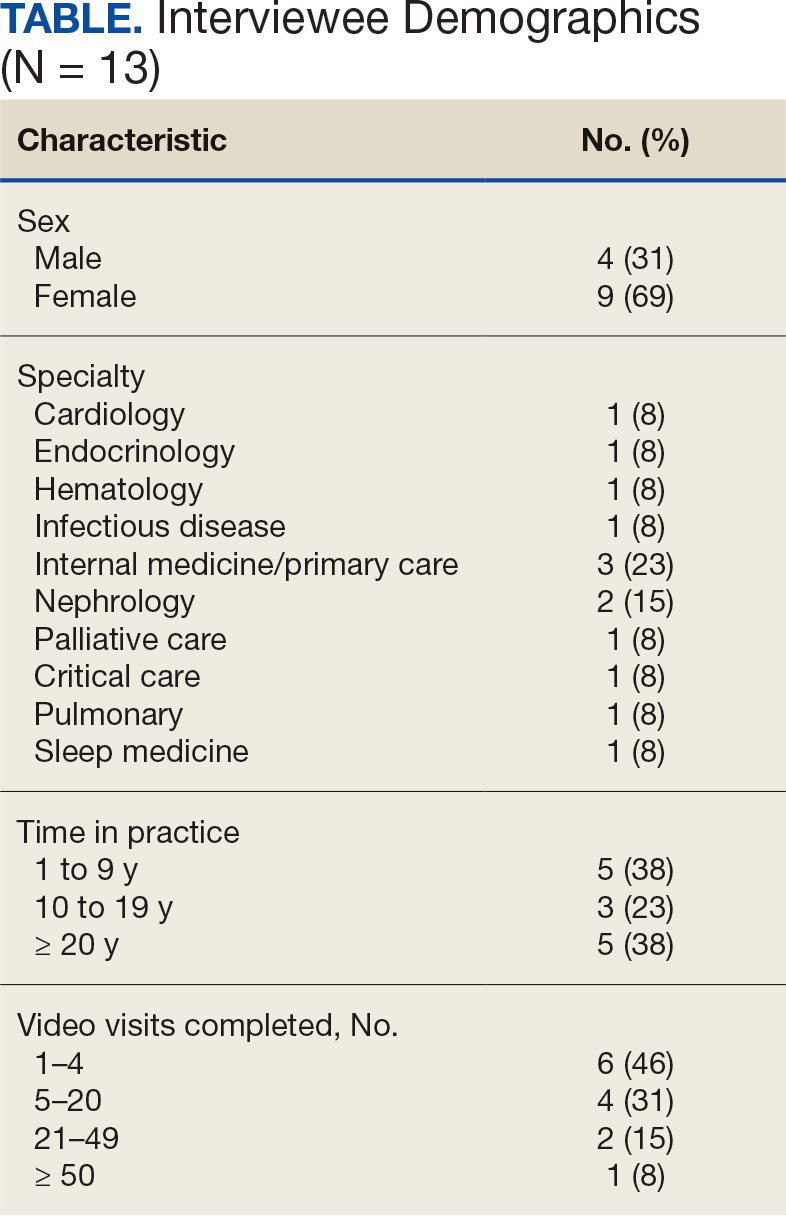

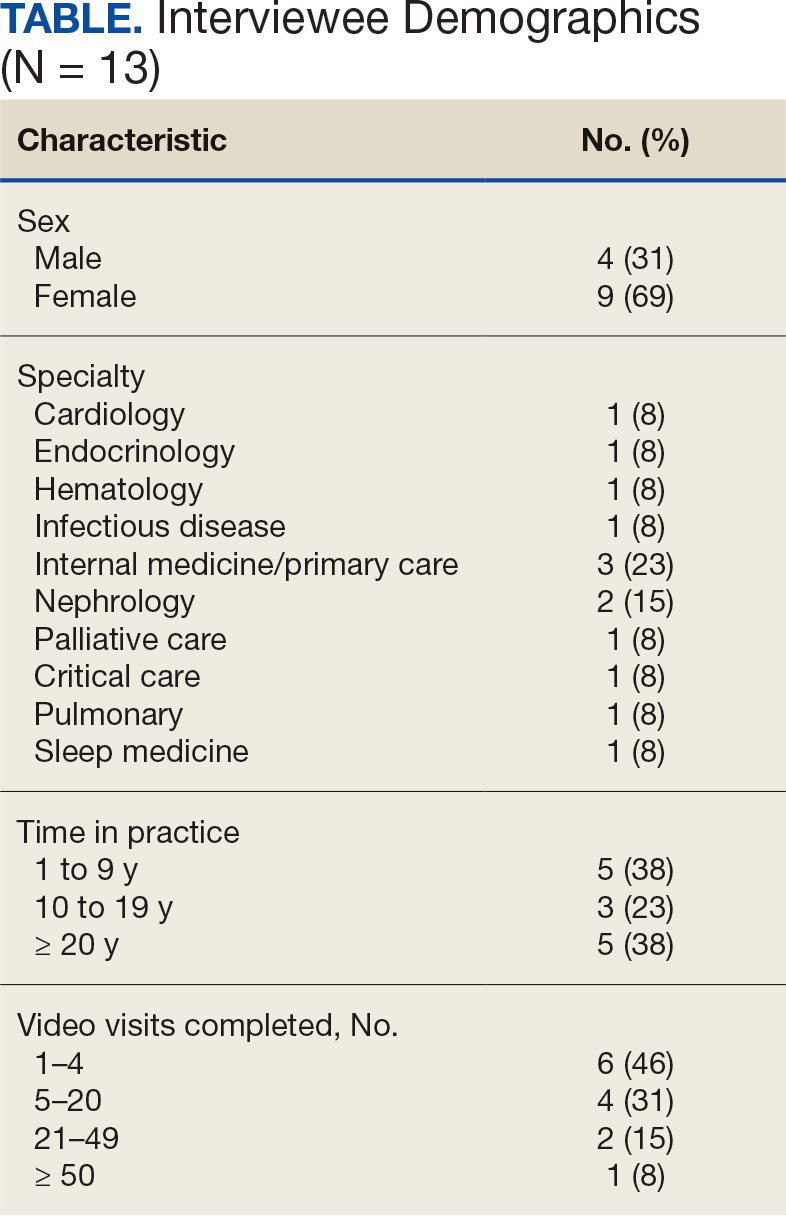

Thirteen interviews were conducted and 9 participants (69%) were female. Participating physicians included 3 internal medicine/primary care physicians (23%), 2 nephrologists (15%), and 1 (8%) from cardiology, endocrinology, hematology, infectious diseases, palliative care, critical care, pulmonology, and sleep medicine. Years of post training experience among physicians ranged from 1 to 9 years (n = 5, 38%), 10 to 19 years (n = 3, 23%), and . 20 years (n = 5, 38%). Seven participants (54%) had conducted ≥ 5 VVC visits, with 1 physician completing > 50 video visits (Table).

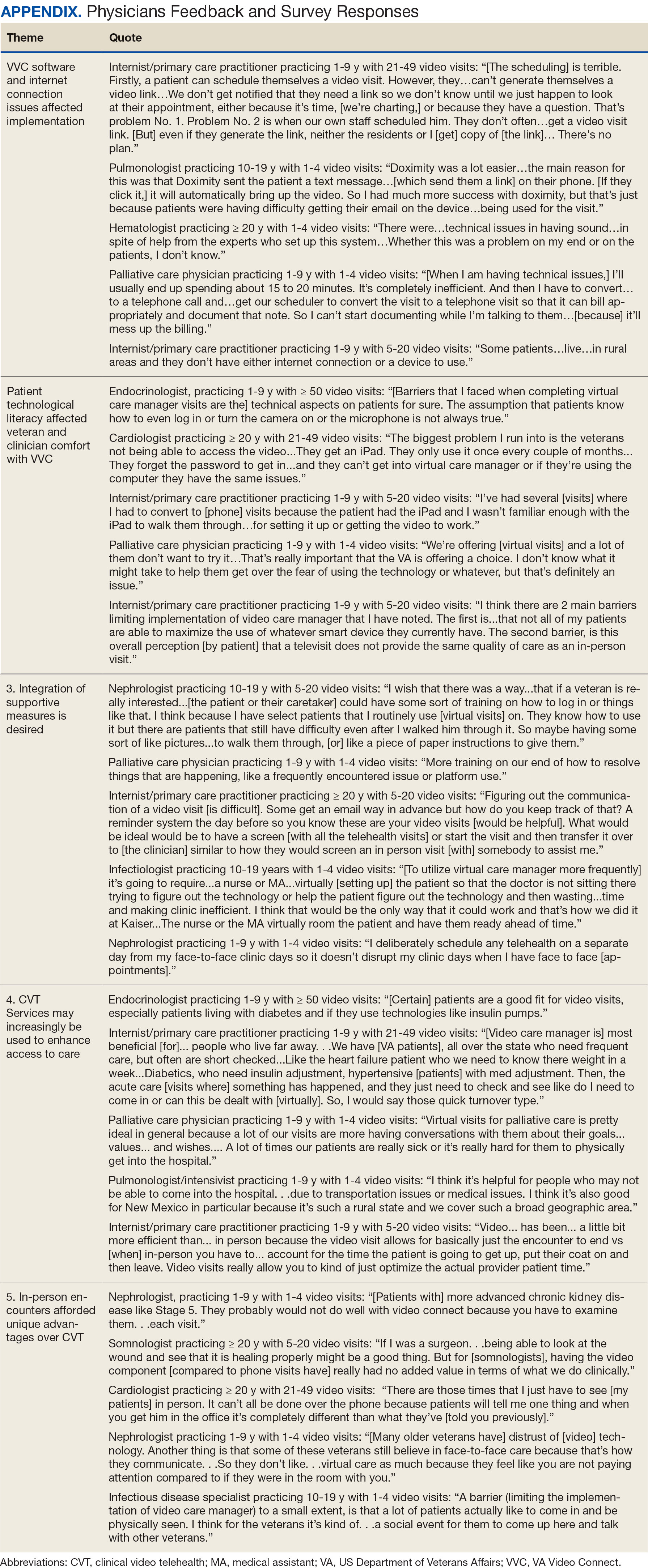

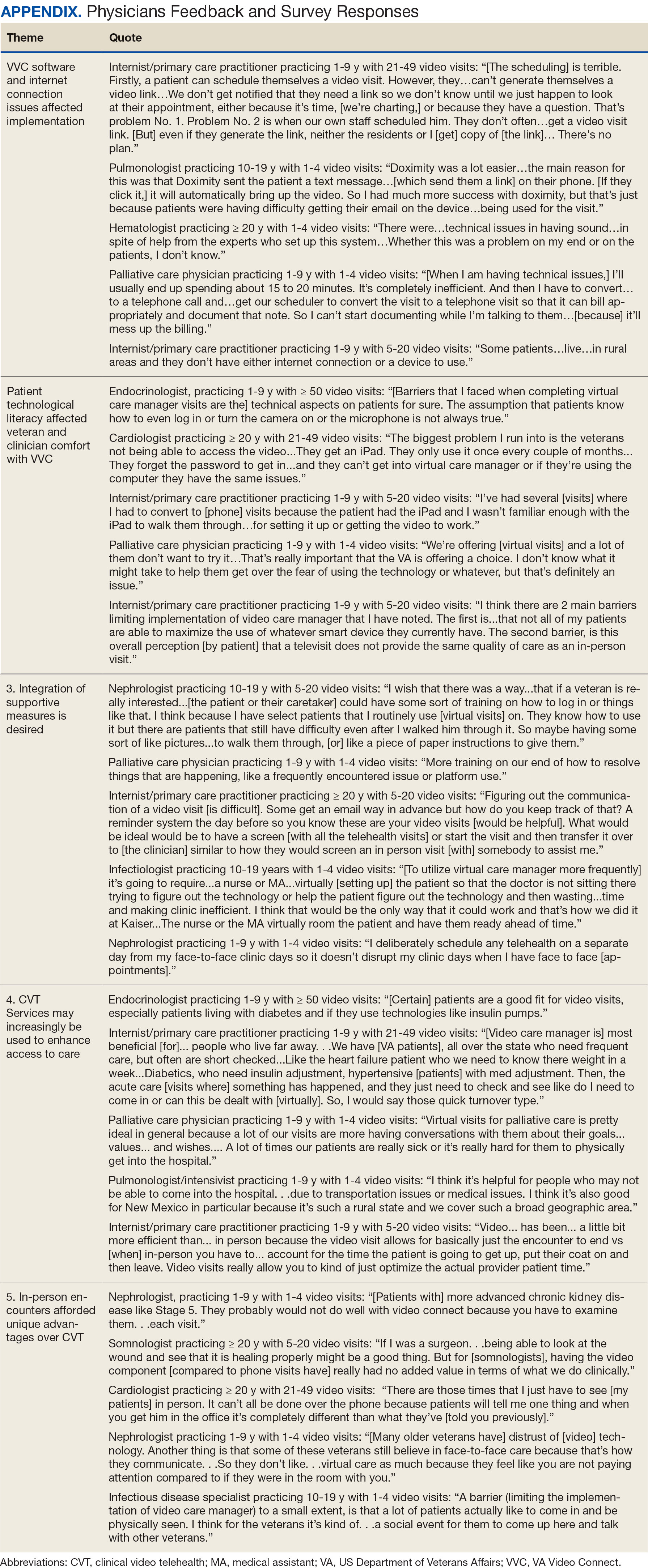

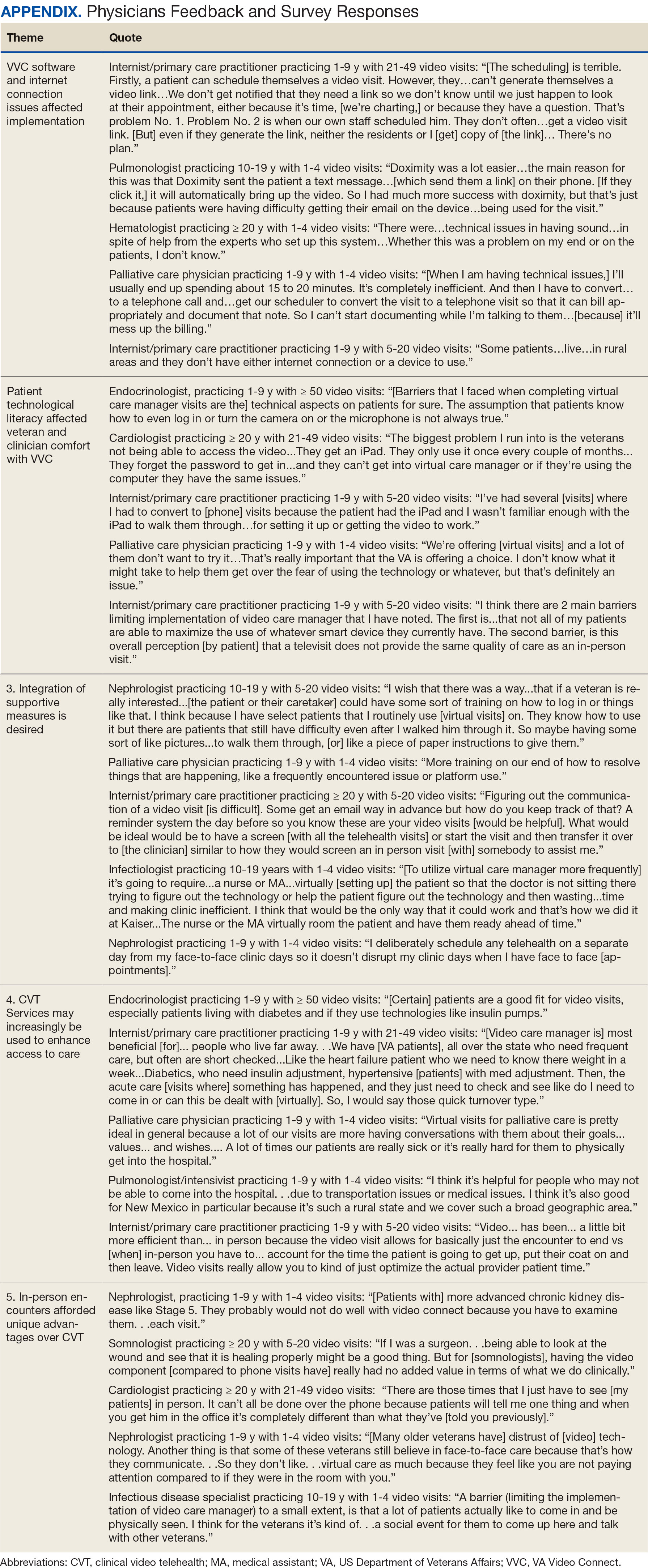

Using open coding and a deductive approach to thematic analysis, 5 themes were identified: (1) VVC software and internet connection issues affected implementation; (2) patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC; (3) integration of supportive measures was desired; (4) CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care; and (5) in-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Illustrative quotes from physicians that reflect these themes can be found in the Appendix.

Theme 1: VVC software and internet connection issues affected its implementation. Most participants expressed concern about the technical challenges with VVC. Interviewees cited inconsistencies for both patients and physicians receiving emails with links to join VVC visits, which should be generated when appointments are scheduled. Some physicians were unaware of scheduled VVC visits until the day of the appointment and only received the link via email. Such issues appeared to occur regardless whether the physicians or support staff scheduled the encounter. Poor video and audio quality was also cited as significant barriers to successful VVC visits and were often not resolvable through troubleshooting efforts by physicians, patients, or support personnel. Given the limited time allotted to each patient encounter, such issues could significantly impact the physician’s ability to remain on schedule. Moreover, connectivity problems led to significant lapses, delays in audio and video transmission, and complete disconnections from the VVC encounter. This was a significant concern for participants, given the rural nature of New Mexico and the large geographical gaps in internet service throughout the state.

Theme 2: Patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC. Successful VVC appointments require high-speed Internet and compatible hardware. Physicians indicated that some patients reported difficulties with critical steps in the process, such as logging into the VVC platform or ensuring their microphones and cameras were active. Physicians also expressed concern about older veterans’ ability to utilize electronic devices, noting they may generally be less technology savvy. Additionally, physicians reported that despite offering the option of a virtual visit, many veterans preferred in-person visits, regardless of the drive time required. This appeared related to a fear of using the technology, which led veterans to believe that virtual visits do not provide the same quality of care as in-person visits.

Theme 3: Integration of supportive measures is desired. Interviewees felt that integrated VVC technical assistance and technology literacy education were imperative. First, training the patient or the patient’s caregiver on how to complete a VVC encounter using the preferred device and the VVC platform would be beneficial. Second, education to inform physicians about common troubleshooting issues could help streamline VVC encounters. Third, managing a VVC encounter similarly to standard in-person visits could allow for better patient and physician experience. For example, physicians suggested that a medical assistant or a nurse triage the patient, take vital signs, and set them up in a room, potentially at a regional VA community based outpatient clinic. Such efforts would also allow patients to receive specialty care in remote areas where only primary care is generally offered. Support staff could assist with technological issues, such as setting up the VVC encounter and addressing potential problems before the physician joins the encounter, thereby preventing delays in patient care. Finally, physicians felt that designating a day solely for CVT visits would help prevent disruption in care with in-person visits.

Theme 4: CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care. Physicians felt that VVC would help patients encountering obstacles in accessing conventional in person services, including patients in rural and underserved areas, with disabilities, or with scheduling challenges.4 Patients with chronic conditions might drive the use of virtual visits, as many of these patients are already accustomed to remote medical monitoring. Data from devices such as scales and continuous glucose monitors can be easily reviewed during VVC visits. Second, video encounters facilitate closer monitoring that some patients might otherwise skip due to significant travel barriers, especially in a rural state like New Mexico. Lastly, VVC may be more efficient than in person visits as they eliminate the need for lengthy parking, checking in, and checking out processes. Thus, if technological issues are resolved, a typical physician’s day in the clinic may be more efficient with virtual visits.

Theme 5: In-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Some physicians felt in-person visits still offer unique advantages. They opined that the selection of appropriate candidates for CVT is critical. Patients requiring a physical examination should be scheduled for in person visits. For example, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who require accurate volume status assessment or patients who have recently undergone surgery and need detailed wound inspection should be seen in the clinic. In-person visits may also be preferable for patients with recurrent admissions, or those whose condition is difficult to assess; accurate assessments of such patients may help prevent readmissions. Finally, many patients are more comfortable and satisfied with in-person visits, which are perceived as a more standard or traditional process. Respondents noted that some patients felt physicians may not focus as much attention during a VVC visit as they do during in-person visits. There were also concerns that some patients feel more motivation to come to in-person visits, as they see the VA as a place to interact with other veterans and staff with whom they are familiar and comfortable.

DISCUSSION

VANMHCS physicians, which serves veterans across an expansive territory ranging from Southern Colorado to West Texas. About 4.6 million veterans reside in rural regions, constituting roughly 25% of the total veteran population, a pattern mirrored in New Mexico.13 Medicine Service physicians agreed on a number of themes: VVC user-interface issues may affect its use and effectiveness, technological literacy was important for both patients and health care staff, technical support staff roles before and during VVC visits should be standardized, CVT is likely to increase health care delivery, and in-person encounters are preferred for many patients.

This is the first study to qualitatively evaluate a diverse group of physicians at a VA medical center incorporating CVT services across specialties. A few related qualitative studies have been conducted external to VHA, generally evaluating clinicians within a single specialty. Kalicki and colleagues surveyed 16 physicians working at a large home-based primary care program in New York City between April and June 2020 to identify and explore barriers to telehealth among homebound older adults. Similarly to our study, physicians noted that many patients required assistance (family members or caregivers) with the visit, either due to technological literacy issues or medical conditions like dementia.14

Heyer and colleagues surveyed 29 oncologists at an urban academic center prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to our observations, the oncologists said telemedicine helped eliminate travel as a barrier to health care. Heyer and colleagues noted difficulty for oncologists in performing virtual physical examinations, despite training. This group did note the benefits when being selective as to which clinical issues they would handle virtually vs in person.15

Budhwani and colleagues reported that mental health professionals in an academic setting cited difficulty establishing therapeutic relationships via telehealth and felt that this affected quality of care.16 While this was not a topic during our interviews, it is reasonable to question how potentially missed nonverbal cues may impact patient assessments.

Notably, technological issues were common among all reviewed studies. These ranged from internet connectivity issues to necessary electronic devices. As mentioned, these barriers are more prevalent in rural states like New Mexico.

Limitations

All participants in this study were Medicine Service physicians of a single VA health care system, which may limit generalizability. Many of our respondents were female (69%), compared with 39.2% of active internal medicine physicians and therefore may not be representative.17 Nearly one-half of our participants only completed 1 to 4 VVC encounters, which may have contributed to the emergence of a common theme regarding technological issues. Physicians with more experience with CVT services may be more skilled at troubleshooting technological issues that arise during visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study, conducted with VANMHCS physicians, illuminated 5 key themes influencing the use and implementation of video encounters: technological issues, technological literacy, a desire for integrated support measures, perceived future growth of video telehealth, and the unique advantages of in-person visits. Addressing technological barriers and providing more extensive training may streamline CVT use. However, it is vital to recognize the unique benefits of in-person visits and consider the benefits of each modality along with patient preferences when selecting the best care venue. As health care evolves, better understanding and acting upon these themes will optimize telehealth services, particularly in rural areas. Future research should involve patients and other health care team members to further explore strategies for effective CVT service integration.

Appendix

- Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during covid-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1193. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12. doi:10.1177/1357633X16674087

- Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

- Yellowlees P, Nakagawa K, Pakyurek M, Hanson A, Elder J, Kales HC. Rapid conversion of an outpatient psychiatric clinic to a 100% virtual telepsychiatry clinic in response to covid-19. Pyschiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):749-752. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000230

- Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Roine R. Study quality and evidence of benefit in recent assessments of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(6):318-324. doi:10.1258/1357633042602053

- Osuji TA, Macias M, McMullen C, et al. Clinician perspectives on implementing video visits in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):221-226. doi:10.1089/pmr.2020.0074

- Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the Veterans Health Administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):761-768. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0143

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/nejmra1601705

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA video connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: Baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Padala KP, Wilson KB, Gauss CH, Stovall JD, Padala PR. VA video connect for clinical care in older adults in a rural state during the covid-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9)e21561. doi:10.2196/21561

- Myers US, Coulon S, Knies K, et al. Lessons learned in implementing VA video connect for evidence-based psychotherapies for anxiety and depression in the veterans healthcare administration. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;6(2):320-326. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00161-8

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Feterans Analysis and Statistics. Accessed September 18, 2024. www.va.gov/vetdata/report.asp

- Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, Ornstein KA. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2404-2411. doi:10.1111/jgs.17163

- Heyer A, Granberg RE, Rising KL, Binder AF, Gentsch AT, Handley NR. Medical oncology professionals’ perceptions of telehealth video visits. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1) e2033967. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33967

- Budhwani S, Fujioka JK, Chu C, et al. Delivering mental health care virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative evaluation of provider experiences in a scaled context. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9)e30280. doi:10.2196/30280

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2021. AAMC. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems had been increasingly focused on expanding care delivery through clinical video telehealth (CVT) services.1-3 These modalities offer clinicians and patients opportunities to interact without needing face-to-face visits. CVT services offer significant advantages to patients who encounter challenges accessing traditional face-to-face services, including those living in rural or underserved areas, individuals with mobility limitations, and those with difficulty attending appointments due to work or caregiving commitments.4 The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the expansion of CVT services to mitigate the spread of the virus.1

Despite its evident advantages, widespread adoption of CVT has encountered resistance.2 Physicians have frequently expressed concerns about the reliability and functionality of CVT platforms for scheduled encounters and frustration with inadequate training.4-6 Additionally, there is a lack trust in the technology, as physicians are unfamiliar with reimbursement or workload capture associated with CVT. Physicians have concerns that telecommunication may diminish the intangible aspects of the “art of medicine.”4 As a result, the implementation of telehealth services has been inconsistent, with successful adoption limited to specific medical and surgical specialties.4 Only recently have entire departments within major health care systems expressed interest in providing comprehensive CVT services in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides an appropriate setting for assessing clinician perceptions of telehealth services. Since 2003, the VHA has significantly expanded CVT services to eligible veterans and has used the VA Video Connect (VVC) platform since 2018.7-10 Through VVC, VA staff and clinicians may schedule video visits with patients, meet with patients through virtual face-to-face interaction, and share relevant laboratory results and imaging through screen sharing. Prior research has shown increased accessibility to care through VVC. For example, a single-site study demonstrated that VVC implementation for delivering psychotherapies significantly increased CVT encounters from 15% to 85% among veterans with anxiety and/or depression.11

The VA New Mexico Healthcare System (VANMHCS) serves a high volume of veterans living in remote and rural regions and significantly increased its use of CVT during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce in-person visits. Expectedly, this was met with a variety of challenges. Herein, we sought to assess physician perspectives, concerns, and attitudes toward VVC via semistructured interviews. Our hypothesis was that VA physicians may feel uncomfortable with video encounters but recognize the growing importance of such practices providing specialty care to veterans in rural areas.

METHODS

A semistructured interview protocol was created following discussions with physicians from the VANMHCS Medicine Service. Questions were constructed to assess the following domains: overarching views of video telehealth, perceptions of various applications for conducting VVC encounters, and barriers to the broad implementation of video telehealth. A qualitative investigation specialist aided with question development. Two pilot interviews were conducted prior to performing the interviews with the recruited participants to evaluate the quality and delivery of questions.

All VANMHCS physicians who provided outpatient care within the Department of Medicine and had completed ≥ 1 VVC encounter were eligible to participate. Invitations were disseminated via email, and follow-up emails to encourage participation were sent periodically for 2 months following the initial request. Union approval was obtained to interview employees for a research study. In total, 64 physicians were invited and 13 (20%) chose to participate. As the study did not involve assessing medical interventions among patients, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the VANMHCS Institutional Review Board. Physicians who participated in this study were informed that their responses would be used for reporting purposes and could be rescinded at any time.

Data Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted by a single interviewer and recorded using Microsoft Teams. The interviews took place between February 2021 and December 2021 and lasted 5 to 15 minutes, with a mean duration of 9 minutes. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews. Interviewees were encouraged to expand on their responses to structured questions by recounting past experiences with VVC. Recorded audio was additionally transcribed via Microsoft Teams, and the research team reviewed the transcriptions to ensure accuracy.

The tracking and coding of responses to interview questions were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Initially, 5 transcripts were reviewed and responses were assessed by 2 study team members through open coding. All team members examined the 5 coded transcripts to identify differences and reach a consensus for any discrepancies. Based on recommendations from all team members regarding nuanced excerpts of transcripts, 1 study team member coded the remaining interviews. Thematic analysis was subsequently conducted according to the method described by Braun and Clarke.12 Themes were developed both deductively and inductively by reviewing the direct responses to interview questions and identifying emerging patterns of data, respectively. Indicative quotes representing each theme were carefully chosen for reporting.

RESULTS

Thirteen interviews were conducted and 9 participants (69%) were female. Participating physicians included 3 internal medicine/primary care physicians (23%), 2 nephrologists (15%), and 1 (8%) from cardiology, endocrinology, hematology, infectious diseases, palliative care, critical care, pulmonology, and sleep medicine. Years of post training experience among physicians ranged from 1 to 9 years (n = 5, 38%), 10 to 19 years (n = 3, 23%), and . 20 years (n = 5, 38%). Seven participants (54%) had conducted ≥ 5 VVC visits, with 1 physician completing > 50 video visits (Table).

Using open coding and a deductive approach to thematic analysis, 5 themes were identified: (1) VVC software and internet connection issues affected implementation; (2) patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC; (3) integration of supportive measures was desired; (4) CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care; and (5) in-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Illustrative quotes from physicians that reflect these themes can be found in the Appendix.

Theme 1: VVC software and internet connection issues affected its implementation. Most participants expressed concern about the technical challenges with VVC. Interviewees cited inconsistencies for both patients and physicians receiving emails with links to join VVC visits, which should be generated when appointments are scheduled. Some physicians were unaware of scheduled VVC visits until the day of the appointment and only received the link via email. Such issues appeared to occur regardless whether the physicians or support staff scheduled the encounter. Poor video and audio quality was also cited as significant barriers to successful VVC visits and were often not resolvable through troubleshooting efforts by physicians, patients, or support personnel. Given the limited time allotted to each patient encounter, such issues could significantly impact the physician’s ability to remain on schedule. Moreover, connectivity problems led to significant lapses, delays in audio and video transmission, and complete disconnections from the VVC encounter. This was a significant concern for participants, given the rural nature of New Mexico and the large geographical gaps in internet service throughout the state.

Theme 2: Patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC. Successful VVC appointments require high-speed Internet and compatible hardware. Physicians indicated that some patients reported difficulties with critical steps in the process, such as logging into the VVC platform or ensuring their microphones and cameras were active. Physicians also expressed concern about older veterans’ ability to utilize electronic devices, noting they may generally be less technology savvy. Additionally, physicians reported that despite offering the option of a virtual visit, many veterans preferred in-person visits, regardless of the drive time required. This appeared related to a fear of using the technology, which led veterans to believe that virtual visits do not provide the same quality of care as in-person visits.

Theme 3: Integration of supportive measures is desired. Interviewees felt that integrated VVC technical assistance and technology literacy education were imperative. First, training the patient or the patient’s caregiver on how to complete a VVC encounter using the preferred device and the VVC platform would be beneficial. Second, education to inform physicians about common troubleshooting issues could help streamline VVC encounters. Third, managing a VVC encounter similarly to standard in-person visits could allow for better patient and physician experience. For example, physicians suggested that a medical assistant or a nurse triage the patient, take vital signs, and set them up in a room, potentially at a regional VA community based outpatient clinic. Such efforts would also allow patients to receive specialty care in remote areas where only primary care is generally offered. Support staff could assist with technological issues, such as setting up the VVC encounter and addressing potential problems before the physician joins the encounter, thereby preventing delays in patient care. Finally, physicians felt that designating a day solely for CVT visits would help prevent disruption in care with in-person visits.

Theme 4: CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care. Physicians felt that VVC would help patients encountering obstacles in accessing conventional in person services, including patients in rural and underserved areas, with disabilities, or with scheduling challenges.4 Patients with chronic conditions might drive the use of virtual visits, as many of these patients are already accustomed to remote medical monitoring. Data from devices such as scales and continuous glucose monitors can be easily reviewed during VVC visits. Second, video encounters facilitate closer monitoring that some patients might otherwise skip due to significant travel barriers, especially in a rural state like New Mexico. Lastly, VVC may be more efficient than in person visits as they eliminate the need for lengthy parking, checking in, and checking out processes. Thus, if technological issues are resolved, a typical physician’s day in the clinic may be more efficient with virtual visits.

Theme 5: In-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Some physicians felt in-person visits still offer unique advantages. They opined that the selection of appropriate candidates for CVT is critical. Patients requiring a physical examination should be scheduled for in person visits. For example, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who require accurate volume status assessment or patients who have recently undergone surgery and need detailed wound inspection should be seen in the clinic. In-person visits may also be preferable for patients with recurrent admissions, or those whose condition is difficult to assess; accurate assessments of such patients may help prevent readmissions. Finally, many patients are more comfortable and satisfied with in-person visits, which are perceived as a more standard or traditional process. Respondents noted that some patients felt physicians may not focus as much attention during a VVC visit as they do during in-person visits. There were also concerns that some patients feel more motivation to come to in-person visits, as they see the VA as a place to interact with other veterans and staff with whom they are familiar and comfortable.

DISCUSSION

VANMHCS physicians, which serves veterans across an expansive territory ranging from Southern Colorado to West Texas. About 4.6 million veterans reside in rural regions, constituting roughly 25% of the total veteran population, a pattern mirrored in New Mexico.13 Medicine Service physicians agreed on a number of themes: VVC user-interface issues may affect its use and effectiveness, technological literacy was important for both patients and health care staff, technical support staff roles before and during VVC visits should be standardized, CVT is likely to increase health care delivery, and in-person encounters are preferred for many patients.

This is the first study to qualitatively evaluate a diverse group of physicians at a VA medical center incorporating CVT services across specialties. A few related qualitative studies have been conducted external to VHA, generally evaluating clinicians within a single specialty. Kalicki and colleagues surveyed 16 physicians working at a large home-based primary care program in New York City between April and June 2020 to identify and explore barriers to telehealth among homebound older adults. Similarly to our study, physicians noted that many patients required assistance (family members or caregivers) with the visit, either due to technological literacy issues or medical conditions like dementia.14

Heyer and colleagues surveyed 29 oncologists at an urban academic center prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to our observations, the oncologists said telemedicine helped eliminate travel as a barrier to health care. Heyer and colleagues noted difficulty for oncologists in performing virtual physical examinations, despite training. This group did note the benefits when being selective as to which clinical issues they would handle virtually vs in person.15

Budhwani and colleagues reported that mental health professionals in an academic setting cited difficulty establishing therapeutic relationships via telehealth and felt that this affected quality of care.16 While this was not a topic during our interviews, it is reasonable to question how potentially missed nonverbal cues may impact patient assessments.

Notably, technological issues were common among all reviewed studies. These ranged from internet connectivity issues to necessary electronic devices. As mentioned, these barriers are more prevalent in rural states like New Mexico.

Limitations

All participants in this study were Medicine Service physicians of a single VA health care system, which may limit generalizability. Many of our respondents were female (69%), compared with 39.2% of active internal medicine physicians and therefore may not be representative.17 Nearly one-half of our participants only completed 1 to 4 VVC encounters, which may have contributed to the emergence of a common theme regarding technological issues. Physicians with more experience with CVT services may be more skilled at troubleshooting technological issues that arise during visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study, conducted with VANMHCS physicians, illuminated 5 key themes influencing the use and implementation of video encounters: technological issues, technological literacy, a desire for integrated support measures, perceived future growth of video telehealth, and the unique advantages of in-person visits. Addressing technological barriers and providing more extensive training may streamline CVT use. However, it is vital to recognize the unique benefits of in-person visits and consider the benefits of each modality along with patient preferences when selecting the best care venue. As health care evolves, better understanding and acting upon these themes will optimize telehealth services, particularly in rural areas. Future research should involve patients and other health care team members to further explore strategies for effective CVT service integration.

Appendix

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems had been increasingly focused on expanding care delivery through clinical video telehealth (CVT) services.1-3 These modalities offer clinicians and patients opportunities to interact without needing face-to-face visits. CVT services offer significant advantages to patients who encounter challenges accessing traditional face-to-face services, including those living in rural or underserved areas, individuals with mobility limitations, and those with difficulty attending appointments due to work or caregiving commitments.4 The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the expansion of CVT services to mitigate the spread of the virus.1

Despite its evident advantages, widespread adoption of CVT has encountered resistance.2 Physicians have frequently expressed concerns about the reliability and functionality of CVT platforms for scheduled encounters and frustration with inadequate training.4-6 Additionally, there is a lack trust in the technology, as physicians are unfamiliar with reimbursement or workload capture associated with CVT. Physicians have concerns that telecommunication may diminish the intangible aspects of the “art of medicine.”4 As a result, the implementation of telehealth services has been inconsistent, with successful adoption limited to specific medical and surgical specialties.4 Only recently have entire departments within major health care systems expressed interest in providing comprehensive CVT services in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides an appropriate setting for assessing clinician perceptions of telehealth services. Since 2003, the VHA has significantly expanded CVT services to eligible veterans and has used the VA Video Connect (VVC) platform since 2018.7-10 Through VVC, VA staff and clinicians may schedule video visits with patients, meet with patients through virtual face-to-face interaction, and share relevant laboratory results and imaging through screen sharing. Prior research has shown increased accessibility to care through VVC. For example, a single-site study demonstrated that VVC implementation for delivering psychotherapies significantly increased CVT encounters from 15% to 85% among veterans with anxiety and/or depression.11

The VA New Mexico Healthcare System (VANMHCS) serves a high volume of veterans living in remote and rural regions and significantly increased its use of CVT during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce in-person visits. Expectedly, this was met with a variety of challenges. Herein, we sought to assess physician perspectives, concerns, and attitudes toward VVC via semistructured interviews. Our hypothesis was that VA physicians may feel uncomfortable with video encounters but recognize the growing importance of such practices providing specialty care to veterans in rural areas.

METHODS

A semistructured interview protocol was created following discussions with physicians from the VANMHCS Medicine Service. Questions were constructed to assess the following domains: overarching views of video telehealth, perceptions of various applications for conducting VVC encounters, and barriers to the broad implementation of video telehealth. A qualitative investigation specialist aided with question development. Two pilot interviews were conducted prior to performing the interviews with the recruited participants to evaluate the quality and delivery of questions.

All VANMHCS physicians who provided outpatient care within the Department of Medicine and had completed ≥ 1 VVC encounter were eligible to participate. Invitations were disseminated via email, and follow-up emails to encourage participation were sent periodically for 2 months following the initial request. Union approval was obtained to interview employees for a research study. In total, 64 physicians were invited and 13 (20%) chose to participate. As the study did not involve assessing medical interventions among patients, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the VANMHCS Institutional Review Board. Physicians who participated in this study were informed that their responses would be used for reporting purposes and could be rescinded at any time.

Data Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted by a single interviewer and recorded using Microsoft Teams. The interviews took place between February 2021 and December 2021 and lasted 5 to 15 minutes, with a mean duration of 9 minutes. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews. Interviewees were encouraged to expand on their responses to structured questions by recounting past experiences with VVC. Recorded audio was additionally transcribed via Microsoft Teams, and the research team reviewed the transcriptions to ensure accuracy.

The tracking and coding of responses to interview questions were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Initially, 5 transcripts were reviewed and responses were assessed by 2 study team members through open coding. All team members examined the 5 coded transcripts to identify differences and reach a consensus for any discrepancies. Based on recommendations from all team members regarding nuanced excerpts of transcripts, 1 study team member coded the remaining interviews. Thematic analysis was subsequently conducted according to the method described by Braun and Clarke.12 Themes were developed both deductively and inductively by reviewing the direct responses to interview questions and identifying emerging patterns of data, respectively. Indicative quotes representing each theme were carefully chosen for reporting.

RESULTS

Thirteen interviews were conducted and 9 participants (69%) were female. Participating physicians included 3 internal medicine/primary care physicians (23%), 2 nephrologists (15%), and 1 (8%) from cardiology, endocrinology, hematology, infectious diseases, palliative care, critical care, pulmonology, and sleep medicine. Years of post training experience among physicians ranged from 1 to 9 years (n = 5, 38%), 10 to 19 years (n = 3, 23%), and . 20 years (n = 5, 38%). Seven participants (54%) had conducted ≥ 5 VVC visits, with 1 physician completing > 50 video visits (Table).

Using open coding and a deductive approach to thematic analysis, 5 themes were identified: (1) VVC software and internet connection issues affected implementation; (2) patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC; (3) integration of supportive measures was desired; (4) CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care; and (5) in-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Illustrative quotes from physicians that reflect these themes can be found in the Appendix.

Theme 1: VVC software and internet connection issues affected its implementation. Most participants expressed concern about the technical challenges with VVC. Interviewees cited inconsistencies for both patients and physicians receiving emails with links to join VVC visits, which should be generated when appointments are scheduled. Some physicians were unaware of scheduled VVC visits until the day of the appointment and only received the link via email. Such issues appeared to occur regardless whether the physicians or support staff scheduled the encounter. Poor video and audio quality was also cited as significant barriers to successful VVC visits and were often not resolvable through troubleshooting efforts by physicians, patients, or support personnel. Given the limited time allotted to each patient encounter, such issues could significantly impact the physician’s ability to remain on schedule. Moreover, connectivity problems led to significant lapses, delays in audio and video transmission, and complete disconnections from the VVC encounter. This was a significant concern for participants, given the rural nature of New Mexico and the large geographical gaps in internet service throughout the state.

Theme 2: Patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC. Successful VVC appointments require high-speed Internet and compatible hardware. Physicians indicated that some patients reported difficulties with critical steps in the process, such as logging into the VVC platform or ensuring their microphones and cameras were active. Physicians also expressed concern about older veterans’ ability to utilize electronic devices, noting they may generally be less technology savvy. Additionally, physicians reported that despite offering the option of a virtual visit, many veterans preferred in-person visits, regardless of the drive time required. This appeared related to a fear of using the technology, which led veterans to believe that virtual visits do not provide the same quality of care as in-person visits.

Theme 3: Integration of supportive measures is desired. Interviewees felt that integrated VVC technical assistance and technology literacy education were imperative. First, training the patient or the patient’s caregiver on how to complete a VVC encounter using the preferred device and the VVC platform would be beneficial. Second, education to inform physicians about common troubleshooting issues could help streamline VVC encounters. Third, managing a VVC encounter similarly to standard in-person visits could allow for better patient and physician experience. For example, physicians suggested that a medical assistant or a nurse triage the patient, take vital signs, and set them up in a room, potentially at a regional VA community based outpatient clinic. Such efforts would also allow patients to receive specialty care in remote areas where only primary care is generally offered. Support staff could assist with technological issues, such as setting up the VVC encounter and addressing potential problems before the physician joins the encounter, thereby preventing delays in patient care. Finally, physicians felt that designating a day solely for CVT visits would help prevent disruption in care with in-person visits.

Theme 4: CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care. Physicians felt that VVC would help patients encountering obstacles in accessing conventional in person services, including patients in rural and underserved areas, with disabilities, or with scheduling challenges.4 Patients with chronic conditions might drive the use of virtual visits, as many of these patients are already accustomed to remote medical monitoring. Data from devices such as scales and continuous glucose monitors can be easily reviewed during VVC visits. Second, video encounters facilitate closer monitoring that some patients might otherwise skip due to significant travel barriers, especially in a rural state like New Mexico. Lastly, VVC may be more efficient than in person visits as they eliminate the need for lengthy parking, checking in, and checking out processes. Thus, if technological issues are resolved, a typical physician’s day in the clinic may be more efficient with virtual visits.

Theme 5: In-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Some physicians felt in-person visits still offer unique advantages. They opined that the selection of appropriate candidates for CVT is critical. Patients requiring a physical examination should be scheduled for in person visits. For example, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who require accurate volume status assessment or patients who have recently undergone surgery and need detailed wound inspection should be seen in the clinic. In-person visits may also be preferable for patients with recurrent admissions, or those whose condition is difficult to assess; accurate assessments of such patients may help prevent readmissions. Finally, many patients are more comfortable and satisfied with in-person visits, which are perceived as a more standard or traditional process. Respondents noted that some patients felt physicians may not focus as much attention during a VVC visit as they do during in-person visits. There were also concerns that some patients feel more motivation to come to in-person visits, as they see the VA as a place to interact with other veterans and staff with whom they are familiar and comfortable.

DISCUSSION

VANMHCS physicians, which serves veterans across an expansive territory ranging from Southern Colorado to West Texas. About 4.6 million veterans reside in rural regions, constituting roughly 25% of the total veteran population, a pattern mirrored in New Mexico.13 Medicine Service physicians agreed on a number of themes: VVC user-interface issues may affect its use and effectiveness, technological literacy was important for both patients and health care staff, technical support staff roles before and during VVC visits should be standardized, CVT is likely to increase health care delivery, and in-person encounters are preferred for many patients.

This is the first study to qualitatively evaluate a diverse group of physicians at a VA medical center incorporating CVT services across specialties. A few related qualitative studies have been conducted external to VHA, generally evaluating clinicians within a single specialty. Kalicki and colleagues surveyed 16 physicians working at a large home-based primary care program in New York City between April and June 2020 to identify and explore barriers to telehealth among homebound older adults. Similarly to our study, physicians noted that many patients required assistance (family members or caregivers) with the visit, either due to technological literacy issues or medical conditions like dementia.14

Heyer and colleagues surveyed 29 oncologists at an urban academic center prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to our observations, the oncologists said telemedicine helped eliminate travel as a barrier to health care. Heyer and colleagues noted difficulty for oncologists in performing virtual physical examinations, despite training. This group did note the benefits when being selective as to which clinical issues they would handle virtually vs in person.15

Budhwani and colleagues reported that mental health professionals in an academic setting cited difficulty establishing therapeutic relationships via telehealth and felt that this affected quality of care.16 While this was not a topic during our interviews, it is reasonable to question how potentially missed nonverbal cues may impact patient assessments.

Notably, technological issues were common among all reviewed studies. These ranged from internet connectivity issues to necessary electronic devices. As mentioned, these barriers are more prevalent in rural states like New Mexico.

Limitations

All participants in this study were Medicine Service physicians of a single VA health care system, which may limit generalizability. Many of our respondents were female (69%), compared with 39.2% of active internal medicine physicians and therefore may not be representative.17 Nearly one-half of our participants only completed 1 to 4 VVC encounters, which may have contributed to the emergence of a common theme regarding technological issues. Physicians with more experience with CVT services may be more skilled at troubleshooting technological issues that arise during visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study, conducted with VANMHCS physicians, illuminated 5 key themes influencing the use and implementation of video encounters: technological issues, technological literacy, a desire for integrated support measures, perceived future growth of video telehealth, and the unique advantages of in-person visits. Addressing technological barriers and providing more extensive training may streamline CVT use. However, it is vital to recognize the unique benefits of in-person visits and consider the benefits of each modality along with patient preferences when selecting the best care venue. As health care evolves, better understanding and acting upon these themes will optimize telehealth services, particularly in rural areas. Future research should involve patients and other health care team members to further explore strategies for effective CVT service integration.

Appendix

- Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during covid-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1193. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12. doi:10.1177/1357633X16674087

- Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

- Yellowlees P, Nakagawa K, Pakyurek M, Hanson A, Elder J, Kales HC. Rapid conversion of an outpatient psychiatric clinic to a 100% virtual telepsychiatry clinic in response to covid-19. Pyschiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):749-752. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000230

- Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Roine R. Study quality and evidence of benefit in recent assessments of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(6):318-324. doi:10.1258/1357633042602053

- Osuji TA, Macias M, McMullen C, et al. Clinician perspectives on implementing video visits in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):221-226. doi:10.1089/pmr.2020.0074

- Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the Veterans Health Administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):761-768. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0143

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/nejmra1601705

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA video connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: Baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Padala KP, Wilson KB, Gauss CH, Stovall JD, Padala PR. VA video connect for clinical care in older adults in a rural state during the covid-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9)e21561. doi:10.2196/21561

- Myers US, Coulon S, Knies K, et al. Lessons learned in implementing VA video connect for evidence-based psychotherapies for anxiety and depression in the veterans healthcare administration. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;6(2):320-326. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00161-8

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Feterans Analysis and Statistics. Accessed September 18, 2024. www.va.gov/vetdata/report.asp

- Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, Ornstein KA. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2404-2411. doi:10.1111/jgs.17163

- Heyer A, Granberg RE, Rising KL, Binder AF, Gentsch AT, Handley NR. Medical oncology professionals’ perceptions of telehealth video visits. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1) e2033967. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33967

- Budhwani S, Fujioka JK, Chu C, et al. Delivering mental health care virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative evaluation of provider experiences in a scaled context. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9)e30280. doi:10.2196/30280

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2021. AAMC. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021

- Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during covid-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1193. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12. doi:10.1177/1357633X16674087

- Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

- Yellowlees P, Nakagawa K, Pakyurek M, Hanson A, Elder J, Kales HC. Rapid conversion of an outpatient psychiatric clinic to a 100% virtual telepsychiatry clinic in response to covid-19. Pyschiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):749-752. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000230

- Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Roine R. Study quality and evidence of benefit in recent assessments of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(6):318-324. doi:10.1258/1357633042602053

- Osuji TA, Macias M, McMullen C, et al. Clinician perspectives on implementing video visits in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):221-226. doi:10.1089/pmr.2020.0074

- Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the Veterans Health Administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):761-768. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0143

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/nejmra1601705

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA video connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: Baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Padala KP, Wilson KB, Gauss CH, Stovall JD, Padala PR. VA video connect for clinical care in older adults in a rural state during the covid-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9)e21561. doi:10.2196/21561

- Myers US, Coulon S, Knies K, et al. Lessons learned in implementing VA video connect for evidence-based psychotherapies for anxiety and depression in the veterans healthcare administration. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;6(2):320-326. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00161-8

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Feterans Analysis and Statistics. Accessed September 18, 2024. www.va.gov/vetdata/report.asp

- Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, Ornstein KA. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2404-2411. doi:10.1111/jgs.17163

- Heyer A, Granberg RE, Rising KL, Binder AF, Gentsch AT, Handley NR. Medical oncology professionals’ perceptions of telehealth video visits. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1) e2033967. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33967

- Budhwani S, Fujioka JK, Chu C, et al. Delivering mental health care virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative evaluation of provider experiences in a scaled context. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9)e30280. doi:10.2196/30280

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2021. AAMC. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters

EBER-Negative, Double-Hit High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma Responding to Methotrexate Discontinuation

High-grade B-cell lymphomas (HGBCLs) are aggressive lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) that require fluorescence in-situ hybridization to identify gene rearrangements within MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 oncogenes. Traditionally referred to as double-hit or triple-hit lymphomas, HGBCL is a newer entity in the 2016 updated World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms.1 More than 90% of patients with HGBCL present with advanced clinical features, such as central nervous system involvement, leukocytosis, or lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal. Treatment outcomes with aggressive multiagent chemotherapy combined with anti-CD20–targeted therapy are generally worse for patients with double-hit disease, especially among frail patients with advanced age. Patients with underlying autoimmune and rheumatologic conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are at higher risk for developing LPDs. These include highly aggressive subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, such as HGBCL, likely due to cascading events secondary to chronic inflammation and/or immunosuppressive medications. These immunodeficiency-associated LPDs often express positivity for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA (EBER).

We present a case of double-hit HGBCL that was EBER negative with MYC and BCL6 rearrangements in an older veteran with RA managed with methotrexate. An excellent sustained response was observed for the patient’s stage IV double-hit HGBCL disease within 4 weeks of methotrexate discontinuation. To our knowledge, this is the first reported response to methotrexate discontinuation for a patient with HGBCL.

CASE PRESENTATION

A male veteran aged 81 years presented to the Raymond G. Murphy Veterans Affairs Medical Center (RGMVAMC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with an unintentional 25-pound weight loss over 18 months. Pertinent history included RA managed with methotrexate 15 mg weekly for 6 years and a previous remote seizure. The patients prior prostate cancer was treated with radiation at the time of diagnosis and ongoing androgen deprivation therapy. Initial workup with chest X-ray and chest computed tomography (CT) indicated loculated left pleural fluid collection with a suspected splenic tumor.

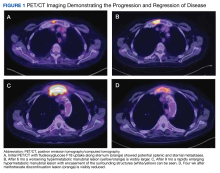

A positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT was ordered given his history of prostate cancer, which showed potential splenic and sternal metastases with corresponding fludeoxyglucose F18 uptake (Figure 1A). Biopsy was not pursued due to the potential for splenic hemorrhage. Based on the patient’s RA and methotrexate use, the collection of findings was initially thought to represent a non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with knowledge that metastatic prostate cancer refractory to androgen deprivation therapy was possible. Because he was unable to undergo a splenic biopsy, an observation strategy involving repeat PET/CT every 6 months was started.

The surveillance PET/CT 6 months later conveyed worsened disease burden with increased avidity in the manubrium (Figure 1B). The patient’s case was discussed at the RGMVAMC tumor board, and the recommendation was to continue with surveillance follow-up imaging because image-guided biopsy might not definitively yield a diagnosis. Repeat PET/CT3 months later indicated continued worsening of disease (Figure 1C) with a rapidly enlarging hypermetabolic mass in the manubrium that extended anteriorly into the subcutaneous tissues and encased the bilateral anterior jugular veins. On physical examination, this sternal mass had become painful and was clearly evident. Additionally, increased avidity in multiple upper abdominal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes was observed.

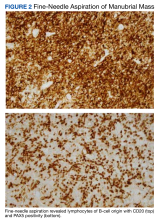

Interventional radiology was consulted to assist with a percutaneous fine-needle aspiration of the manubrial mass, which revealed a dense aggregate of large, atypical lymphocytes confirmed to be of B-cell origin (CD20 and PAX5 positive) (Figure 2). The atypical B cells demonstrated co-expression of BCL6, BCL2, MUM1, and MYC but were negative for CD30 and EBER by in situ hybridization. The overall morphologic and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with a large B-cell lymphoma. Fluorescent in-situ hybridization identified the presence of MYC and BCL6 gene rearrangements, and the mass was consequently best classified as a double-hit HGBCL.

Given the patient’s history of long-term methotrexate use, we thought the HGBCL may have reflected an immunodeficiency-associated LPD, although the immunophenotype was not classic because of the CD30 and EBER negativity. With the known toxicity and poor treatment outcomes of aggressive multiagent chemotherapy for patients with double-hit HGBCL—particularly in the older adult population—methotrexate was discontinued on a trial basis.

A PET/CT was completed 4 weeks after methotrexate was discontinued due to concerns about managing an HGBCL without chemotherapy or anti-CD20–directed therapy. The updated PET/CT showed significant improvement with marked reduction in avidity of his manubrial lesion (Figure 1D). Three months after methotrexate discontinuation, the patient remained in partial remission for his double-hit HGBCL, as evidenced by no findings of sternal mass on repeat examinations with continued decrease in hypermetabolic findings on PET/CT. The patient's RA symptoms rebounded, and rheumatology colleagues prescribed sulfasalazine and periodic steroid tapers to help control his inflammatory arthritis. Fourteen months after discontinuation of methotrexate, the patient died after developing pneumonia, which led to multisystemic organ failure.

DISCUSSION

HGBCL with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements is an aggressive LPD.1 A definitive diagnosis requires collection of morphologic and immunophenotypic evaluations of suspicious tissue. Approximately 60% of patients with HGBCL have translocations in MYC and BCL2, 20% have MYC and BCL6 translocations, and the remaining 20% have MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 translocations (triple-hit disease).1

The MYC and BCL gene rearrangements are thought to synergistically drive tumorigenesis, leading to accelerated lymphoma progression and a lesser response to standard multiagent chemotherapy than seen in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.1-3 Consequently, there have been several attempts to increase treatment efficacy with intense chemotherapy regimens, namely DA-EPOCH-R (dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab), or by adding targeted agents, such as ibrutinib and venetoclax to a standard R-CHOP (rituximab with reduced cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) backbone.4-7 Though the standard choice of therapy for fit patients harboring HGBCL remains controversial, these aggressive regimens at standard doses are typically difficult to tolerate for patients aged > 80 years.

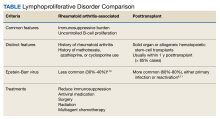

Patients with immunosuppression are at higher risk for developing LPDs, including aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. These patients are frequently classified into 2 groups: those with underlying autoimmune conditions (RA-associated LPDs), or those who have undergone solid-organ or allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplants, which drives the development of posttransplant LPDs (Table).8-11 Both types of LPDs are often EBER positive, indicating some association with Epstein-Barr virus infection driven by ongoing immunosuppression, with knowledge that this finding is not absolute and is less frequent among patients with autoimmune conditions than those with posttransplant LPD.8,12

For indolent and early-stage aggressive LPDs, reduction of immunosuppression is a reasonable frontline treatment. In fact, Tokuyama and colleagues reported a previous case in which an methotrexate-associated EBER-positive early-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma responded well to methotrexate withdrawal.13 For advanced, aggressive LPDs associated with immunosuppression, a combination strategy of reducing immunosuppression and initiating a standard multiagent systemic therapy such as with R-CHOP is more common. Reducing immunosuppression without adding systemic anticancer therapy can certainly be considered in patients with EBER-negative LPDs; however, there is less evidence supporting this approach in the literature.

A case series of patients with EBER-positive double-hit HGBCL has been described previously, and response rates were low despite aggressive treatment.14 The current case differs from that case series in 2 ways. First, our patient did not have EBER-positive disease despite having an HGBCL associated with RA and methotrexate use. Second, our patient had a very rapid and excellent partial response simply with methotrexate discontinuation. Aggressive treatment was considered initially; however, given the patient’s age and performance status, reduction of immunosuppression alone was considered the frontline approach.

This case indicates that methotrexate withdrawal may lead to remission in patients with double-hit lymphoma, even without clear signs of Epstein-Barr virus infection being present. We are not sure why our patient with EBER-negative HGBCL responded differently to methotrexate withdrawal than the patients in the aforementioned case series with EBER-positive disease; nevertheless, a short trial of methotrexate withdrawal with repeat imaging 4 to 8 weeks after discontinuation seems reasonable for patients who are older, frail, and seemingly not fit for more aggressive treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

For our older patient with RA and biopsy-proven, stage IV EBER-negative HGBCL bearing MYC and BCL6 rearrangements (double hit), discontinuation of methotrexate led to a rapid and sustained marked response. Reducing immunosuppression should be considered for patients with LPDs associated with autoimmune conditions or immunosuppressive medications, regardless of additional multiagent systemic therapy administration. In older patients who are frail with aggressive B-cell lymphomas, a short trial of methotrexate withdrawal with quick interval imaging is a reasonable frontline option, regardless of EBER status.

1. Sesques P, Johnson NA. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of high-grade B-cell lymphomas with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements. Blood. 2017;129(3):280-288. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-02-636316

2. Aukema SM, Siebert R, Schuuring E, et al. Double-hit B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2011;117(8):2319-2331. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-09-297879

3. Scott DW, King RL, Staiger AM, et al. High-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma morphology. Blood. 2018;131(18):2060-2064. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-12-820605

4. Dunleavy K, Fanale MA, Abramson JS, et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab) in untreated aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with MYC rearrangement: a prospective, multicentre, single-arm phase 2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5(12):e609-e617. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30177-7

5. Younes A, Sehn LH, Johnson P, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ibrutinib and rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in non-germinal center B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):1285-1295. doi:10.1200/JCO.18.02403

6. Morschhauser F, Feugier P, Flinn IW, et al. A phase 2 study of venetoclax plus R-CHOP as first-line treatment for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2021;137(5):600-609. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006578

7. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). B-cell lymphomas. Version 2.2024. January 18, 2024. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf

8. Abbas F, Kossi ME, Shaheen IS, Sharma A, Halawa A. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: current concepts and future therapeutic approaches. World J Transplant. 2020;10(2):29-46. doi:10.5500/wjt.v10.i2.29

9. Hoshida Y, Xu JX, Fujita S, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in rheumatoid arthritis: clinicopathological analysis of 76 cases in relation to methotrexate medication. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):322-331.

10. Salloum E, Cooper DL, Howe G, et al. Spontaneous regression of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients treated with methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(6):1943-1949. doi:10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1943

11. Nijland ML, Kersten MJ, Pals ST, Bemelman FJ, Ten Berge IJM. Epstein-Barr virus–positive posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease after solid organ transplantation: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Transplantation Direct. 2015;2(1):e48. doi:10.1097/txd.0000000000000557

12. Ekström Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M, et al. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: a pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood. 2008;111(8):4029-4038. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-11997413. Tokuyama K, Okada F, Matsumoto S, et al. EBV-positive methotrexate-diffuse large B cell lymphoma in a rheumatoid arthritis patient. Jpn J Radiol. 2014;32(3):183-187. doi:10.1007/s11604-013-0280-y

14. Liu H, Xu-Monette ZY, Tang G, et al. EBV+ high-grade B cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements: a multi-institutional study. Histopathology. 2022;80(3):575-588. doi:10.1111/his.14585

High-grade B-cell lymphomas (HGBCLs) are aggressive lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) that require fluorescence in-situ hybridization to identify gene rearrangements within MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 oncogenes. Traditionally referred to as double-hit or triple-hit lymphomas, HGBCL is a newer entity in the 2016 updated World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms.1 More than 90% of patients with HGBCL present with advanced clinical features, such as central nervous system involvement, leukocytosis, or lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal. Treatment outcomes with aggressive multiagent chemotherapy combined with anti-CD20–targeted therapy are generally worse for patients with double-hit disease, especially among frail patients with advanced age. Patients with underlying autoimmune and rheumatologic conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are at higher risk for developing LPDs. These include highly aggressive subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, such as HGBCL, likely due to cascading events secondary to chronic inflammation and/or immunosuppressive medications. These immunodeficiency-associated LPDs often express positivity for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA (EBER).

We present a case of double-hit HGBCL that was EBER negative with MYC and BCL6 rearrangements in an older veteran with RA managed with methotrexate. An excellent sustained response was observed for the patient’s stage IV double-hit HGBCL disease within 4 weeks of methotrexate discontinuation. To our knowledge, this is the first reported response to methotrexate discontinuation for a patient with HGBCL.

CASE PRESENTATION

A male veteran aged 81 years presented to the Raymond G. Murphy Veterans Affairs Medical Center (RGMVAMC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with an unintentional 25-pound weight loss over 18 months. Pertinent history included RA managed with methotrexate 15 mg weekly for 6 years and a previous remote seizure. The patients prior prostate cancer was treated with radiation at the time of diagnosis and ongoing androgen deprivation therapy. Initial workup with chest X-ray and chest computed tomography (CT) indicated loculated left pleural fluid collection with a suspected splenic tumor.

A positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT was ordered given his history of prostate cancer, which showed potential splenic and sternal metastases with corresponding fludeoxyglucose F18 uptake (Figure 1A). Biopsy was not pursued due to the potential for splenic hemorrhage. Based on the patient’s RA and methotrexate use, the collection of findings was initially thought to represent a non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with knowledge that metastatic prostate cancer refractory to androgen deprivation therapy was possible. Because he was unable to undergo a splenic biopsy, an observation strategy involving repeat PET/CT every 6 months was started.

The surveillance PET/CT 6 months later conveyed worsened disease burden with increased avidity in the manubrium (Figure 1B). The patient’s case was discussed at the RGMVAMC tumor board, and the recommendation was to continue with surveillance follow-up imaging because image-guided biopsy might not definitively yield a diagnosis. Repeat PET/CT3 months later indicated continued worsening of disease (Figure 1C) with a rapidly enlarging hypermetabolic mass in the manubrium that extended anteriorly into the subcutaneous tissues and encased the bilateral anterior jugular veins. On physical examination, this sternal mass had become painful and was clearly evident. Additionally, increased avidity in multiple upper abdominal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes was observed.

Interventional radiology was consulted to assist with a percutaneous fine-needle aspiration of the manubrial mass, which revealed a dense aggregate of large, atypical lymphocytes confirmed to be of B-cell origin (CD20 and PAX5 positive) (Figure 2). The atypical B cells demonstrated co-expression of BCL6, BCL2, MUM1, and MYC but were negative for CD30 and EBER by in situ hybridization. The overall morphologic and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with a large B-cell lymphoma. Fluorescent in-situ hybridization identified the presence of MYC and BCL6 gene rearrangements, and the mass was consequently best classified as a double-hit HGBCL.

Given the patient’s history of long-term methotrexate use, we thought the HGBCL may have reflected an immunodeficiency-associated LPD, although the immunophenotype was not classic because of the CD30 and EBER negativity. With the known toxicity and poor treatment outcomes of aggressive multiagent chemotherapy for patients with double-hit HGBCL—particularly in the older adult population—methotrexate was discontinued on a trial basis.

A PET/CT was completed 4 weeks after methotrexate was discontinued due to concerns about managing an HGBCL without chemotherapy or anti-CD20–directed therapy. The updated PET/CT showed significant improvement with marked reduction in avidity of his manubrial lesion (Figure 1D). Three months after methotrexate discontinuation, the patient remained in partial remission for his double-hit HGBCL, as evidenced by no findings of sternal mass on repeat examinations with continued decrease in hypermetabolic findings on PET/CT. The patient's RA symptoms rebounded, and rheumatology colleagues prescribed sulfasalazine and periodic steroid tapers to help control his inflammatory arthritis. Fourteen months after discontinuation of methotrexate, the patient died after developing pneumonia, which led to multisystemic organ failure.

DISCUSSION

HGBCL with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements is an aggressive LPD.1 A definitive diagnosis requires collection of morphologic and immunophenotypic evaluations of suspicious tissue. Approximately 60% of patients with HGBCL have translocations in MYC and BCL2, 20% have MYC and BCL6 translocations, and the remaining 20% have MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 translocations (triple-hit disease).1