User login

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems had been increasingly focused on expanding care delivery through clinical video telehealth (CVT) services.1-3 These modalities offer clinicians and patients opportunities to interact without needing face-to-face visits. CVT services offer significant advantages to patients who encounter challenges accessing traditional face-to-face services, including those living in rural or underserved areas, individuals with mobility limitations, and those with difficulty attending appointments due to work or caregiving commitments.4 The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the expansion of CVT services to mitigate the spread of the virus.1

Despite its evident advantages, widespread adoption of CVT has encountered resistance.2 Physicians have frequently expressed concerns about the reliability and functionality of CVT platforms for scheduled encounters and frustration with inadequate training.4-6 Additionally, there is a lack trust in the technology, as physicians are unfamiliar with reimbursement or workload capture associated with CVT. Physicians have concerns that telecommunication may diminish the intangible aspects of the “art of medicine.”4 As a result, the implementation of telehealth services has been inconsistent, with successful adoption limited to specific medical and surgical specialties.4 Only recently have entire departments within major health care systems expressed interest in providing comprehensive CVT services in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides an appropriate setting for assessing clinician perceptions of telehealth services. Since 2003, the VHA has significantly expanded CVT services to eligible veterans and has used the VA Video Connect (VVC) platform since 2018.7-10 Through VVC, VA staff and clinicians may schedule video visits with patients, meet with patients through virtual face-to-face interaction, and share relevant laboratory results and imaging through screen sharing. Prior research has shown increased accessibility to care through VVC. For example, a single-site study demonstrated that VVC implementation for delivering psychotherapies significantly increased CVT encounters from 15% to 85% among veterans with anxiety and/or depression.11

The VA New Mexico Healthcare System (VANMHCS) serves a high volume of veterans living in remote and rural regions and significantly increased its use of CVT during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce in-person visits. Expectedly, this was met with a variety of challenges. Herein, we sought to assess physician perspectives, concerns, and attitudes toward VVC via semistructured interviews. Our hypothesis was that VA physicians may feel uncomfortable with video encounters but recognize the growing importance of such practices providing specialty care to veterans in rural areas.

METHODS

A semistructured interview protocol was created following discussions with physicians from the VANMHCS Medicine Service. Questions were constructed to assess the following domains: overarching views of video telehealth, perceptions of various applications for conducting VVC encounters, and barriers to the broad implementation of video telehealth. A qualitative investigation specialist aided with question development. Two pilot interviews were conducted prior to performing the interviews with the recruited participants to evaluate the quality and delivery of questions.

All VANMHCS physicians who provided outpatient care within the Department of Medicine and had completed ≥ 1 VVC encounter were eligible to participate. Invitations were disseminated via email, and follow-up emails to encourage participation were sent periodically for 2 months following the initial request. Union approval was obtained to interview employees for a research study. In total, 64 physicians were invited and 13 (20%) chose to participate. As the study did not involve assessing medical interventions among patients, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the VANMHCS Institutional Review Board. Physicians who participated in this study were informed that their responses would be used for reporting purposes and could be rescinded at any time.

Data Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted by a single interviewer and recorded using Microsoft Teams. The interviews took place between February 2021 and December 2021 and lasted 5 to 15 minutes, with a mean duration of 9 minutes. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews. Interviewees were encouraged to expand on their responses to structured questions by recounting past experiences with VVC. Recorded audio was additionally transcribed via Microsoft Teams, and the research team reviewed the transcriptions to ensure accuracy.

The tracking and coding of responses to interview questions were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Initially, 5 transcripts were reviewed and responses were assessed by 2 study team members through open coding. All team members examined the 5 coded transcripts to identify differences and reach a consensus for any discrepancies. Based on recommendations from all team members regarding nuanced excerpts of transcripts, 1 study team member coded the remaining interviews. Thematic analysis was subsequently conducted according to the method described by Braun and Clarke.12 Themes were developed both deductively and inductively by reviewing the direct responses to interview questions and identifying emerging patterns of data, respectively. Indicative quotes representing each theme were carefully chosen for reporting.

RESULTS

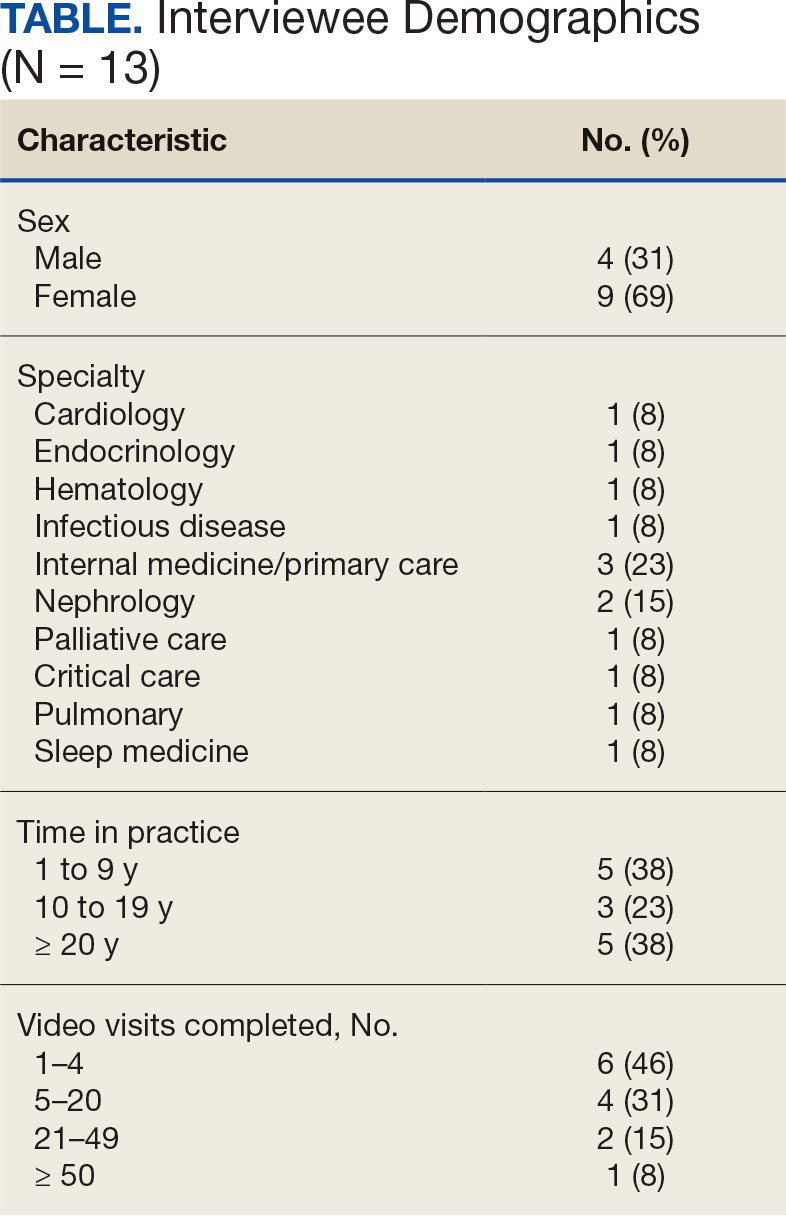

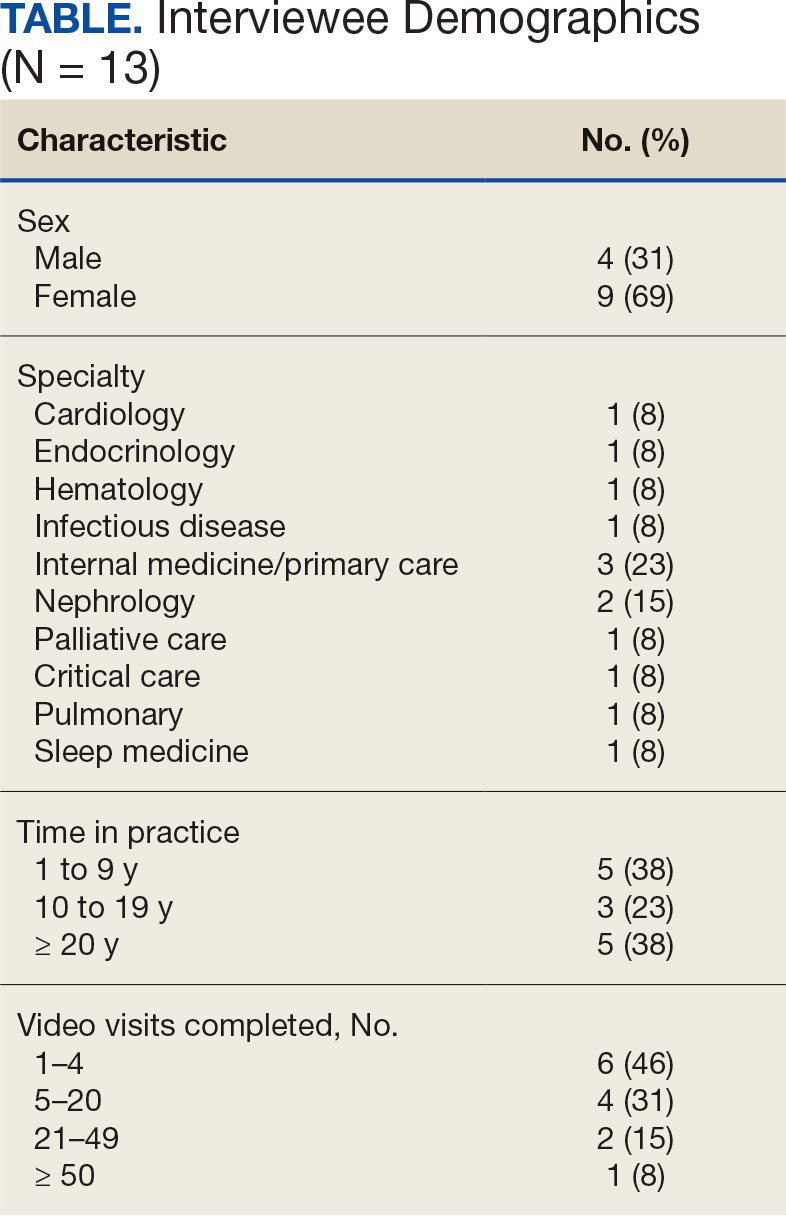

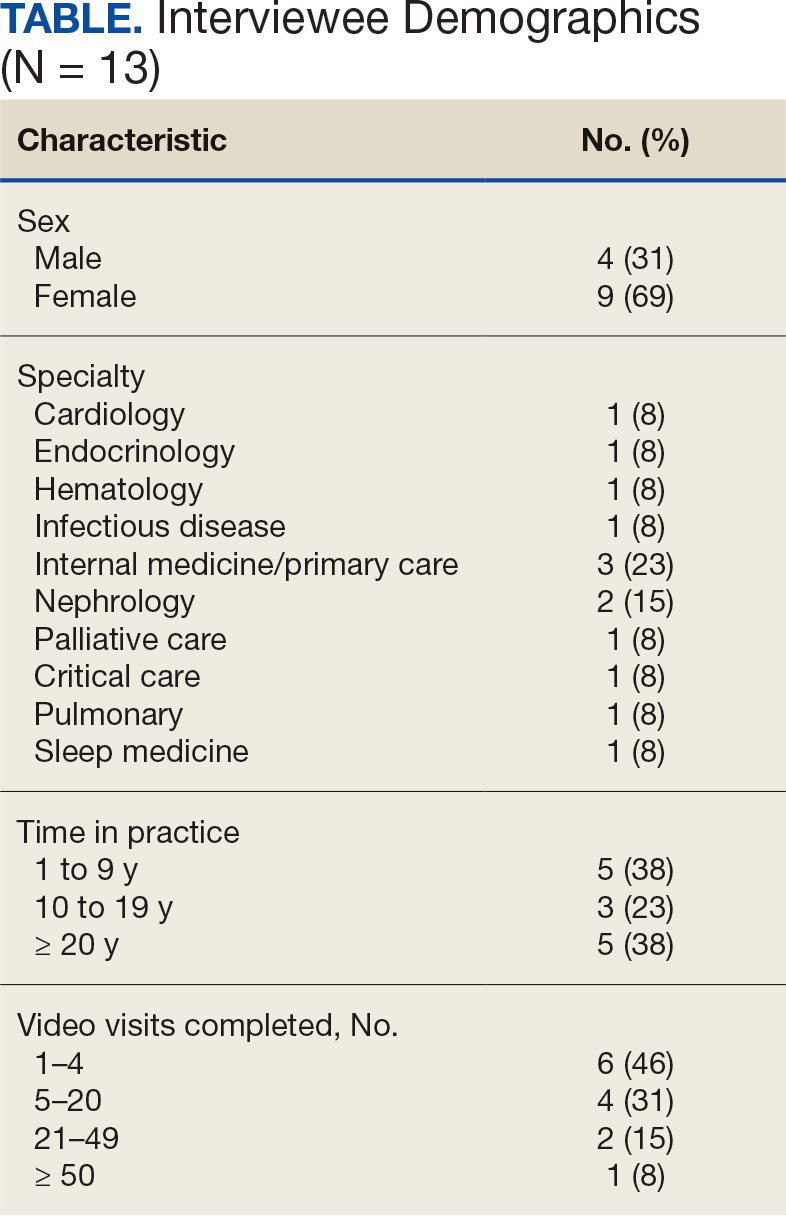

Thirteen interviews were conducted and 9 participants (69%) were female. Participating physicians included 3 internal medicine/primary care physicians (23%), 2 nephrologists (15%), and 1 (8%) from cardiology, endocrinology, hematology, infectious diseases, palliative care, critical care, pulmonology, and sleep medicine. Years of post training experience among physicians ranged from 1 to 9 years (n = 5, 38%), 10 to 19 years (n = 3, 23%), and . 20 years (n = 5, 38%). Seven participants (54%) had conducted ≥ 5 VVC visits, with 1 physician completing > 50 video visits (Table).

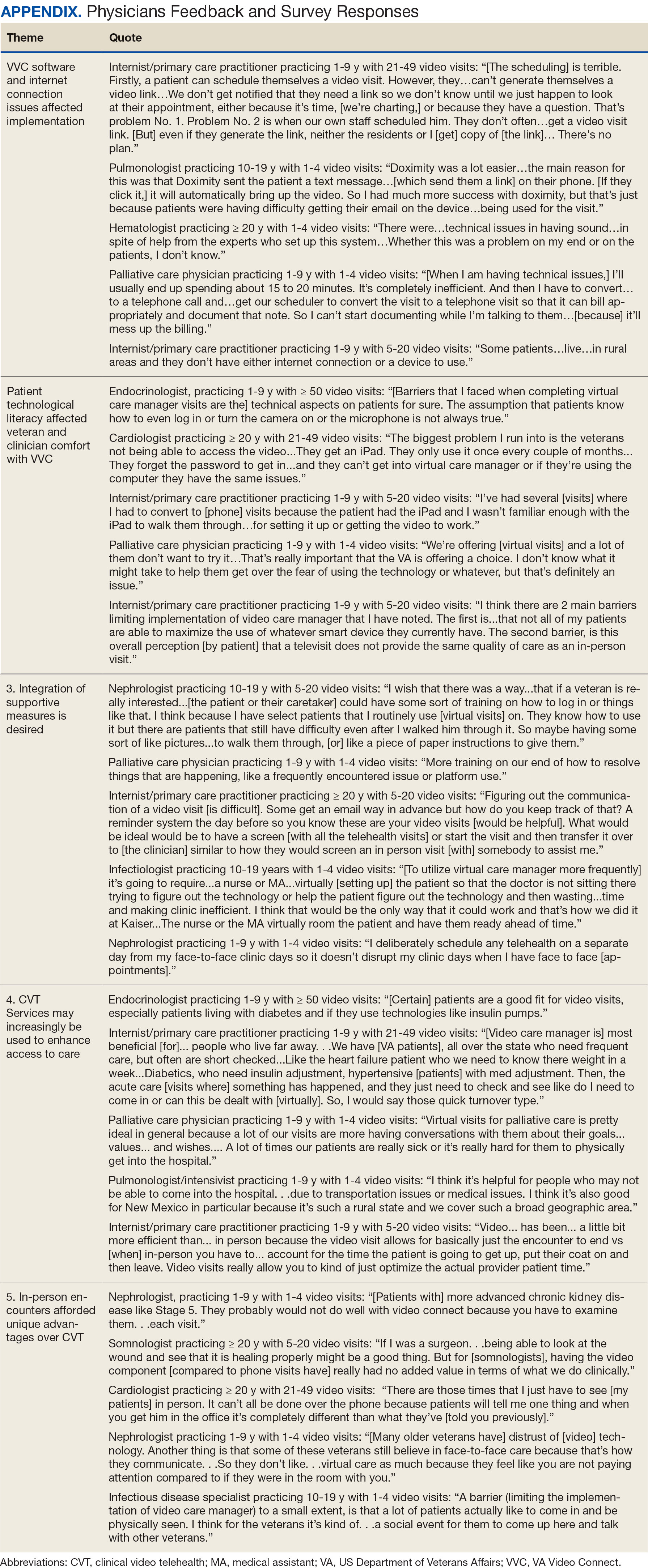

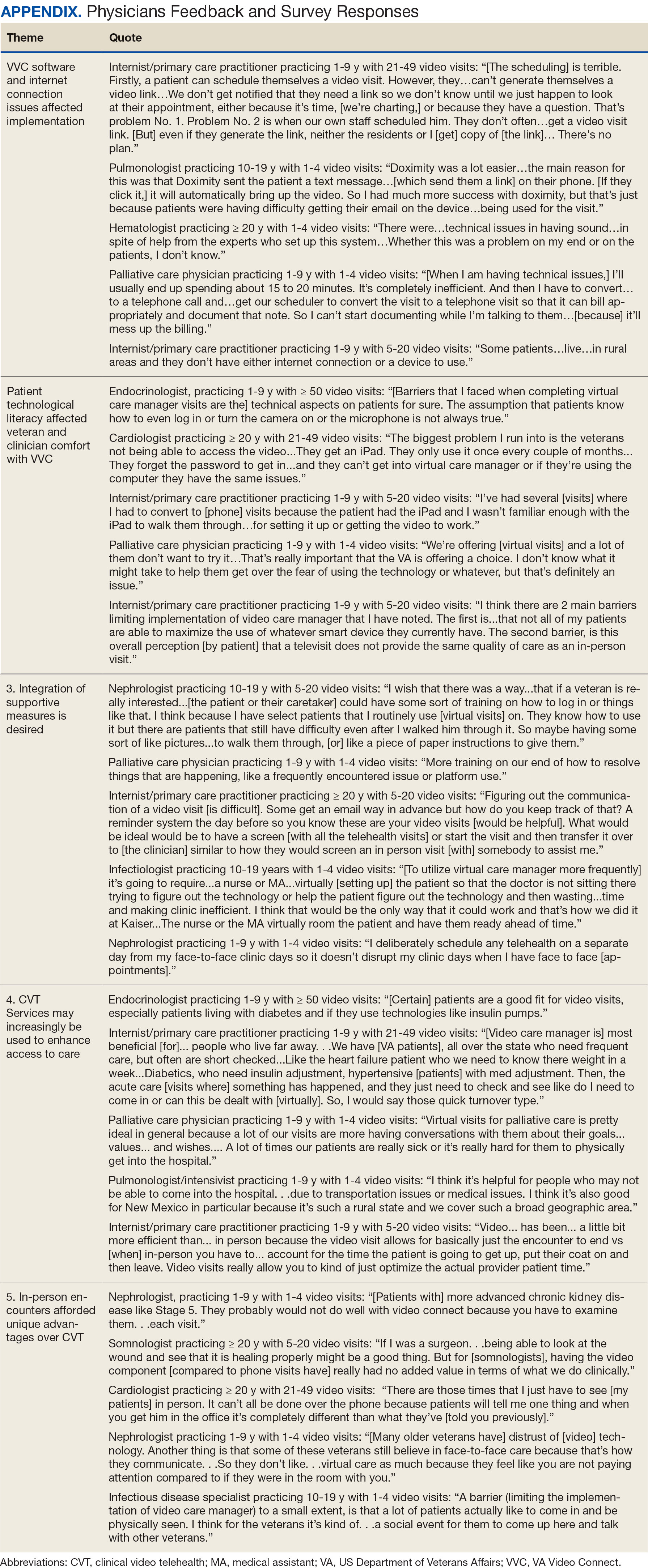

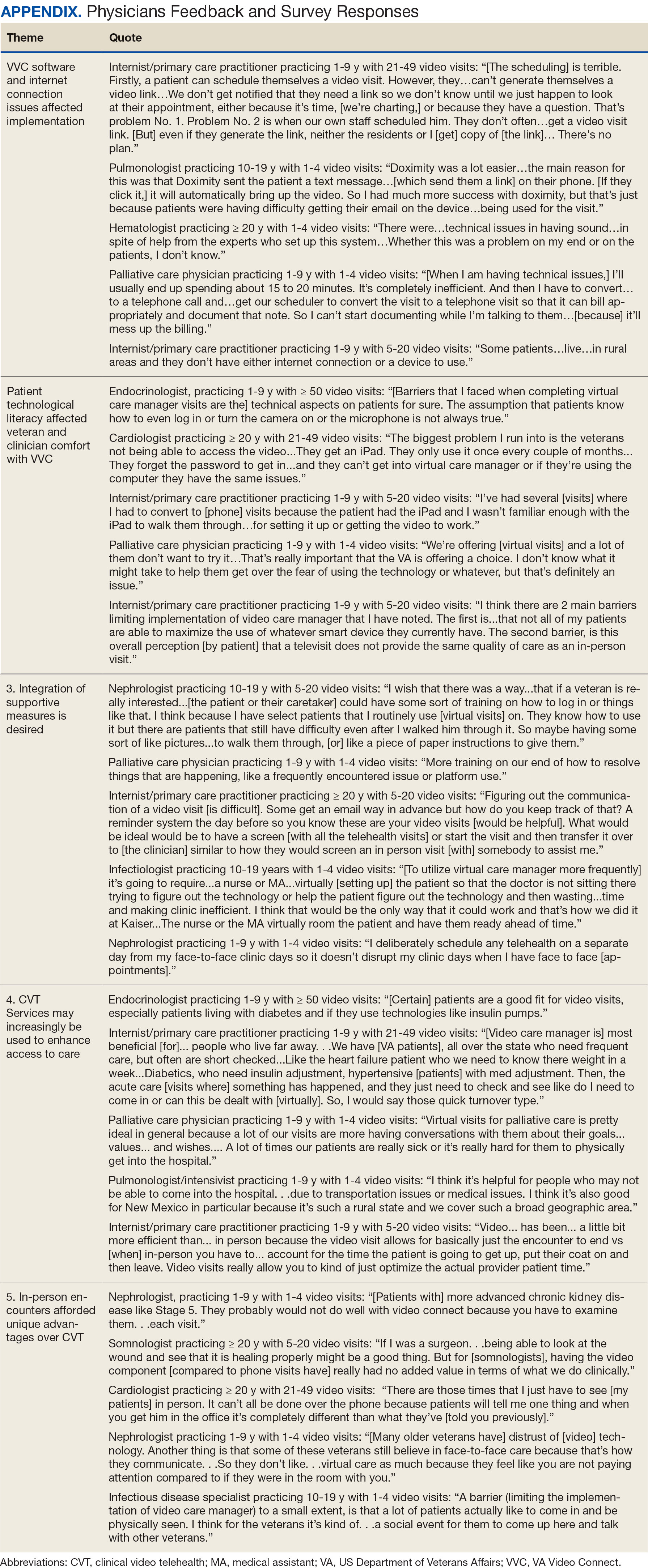

Using open coding and a deductive approach to thematic analysis, 5 themes were identified: (1) VVC software and internet connection issues affected implementation; (2) patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC; (3) integration of supportive measures was desired; (4) CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care; and (5) in-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Illustrative quotes from physicians that reflect these themes can be found in the Appendix.

Theme 1: VVC software and internet connection issues affected its implementation. Most participants expressed concern about the technical challenges with VVC. Interviewees cited inconsistencies for both patients and physicians receiving emails with links to join VVC visits, which should be generated when appointments are scheduled. Some physicians were unaware of scheduled VVC visits until the day of the appointment and only received the link via email. Such issues appeared to occur regardless whether the physicians or support staff scheduled the encounter. Poor video and audio quality was also cited as significant barriers to successful VVC visits and were often not resolvable through troubleshooting efforts by physicians, patients, or support personnel. Given the limited time allotted to each patient encounter, such issues could significantly impact the physician’s ability to remain on schedule. Moreover, connectivity problems led to significant lapses, delays in audio and video transmission, and complete disconnections from the VVC encounter. This was a significant concern for participants, given the rural nature of New Mexico and the large geographical gaps in internet service throughout the state.

Theme 2: Patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC. Successful VVC appointments require high-speed Internet and compatible hardware. Physicians indicated that some patients reported difficulties with critical steps in the process, such as logging into the VVC platform or ensuring their microphones and cameras were active. Physicians also expressed concern about older veterans’ ability to utilize electronic devices, noting they may generally be less technology savvy. Additionally, physicians reported that despite offering the option of a virtual visit, many veterans preferred in-person visits, regardless of the drive time required. This appeared related to a fear of using the technology, which led veterans to believe that virtual visits do not provide the same quality of care as in-person visits.

Theme 3: Integration of supportive measures is desired. Interviewees felt that integrated VVC technical assistance and technology literacy education were imperative. First, training the patient or the patient’s caregiver on how to complete a VVC encounter using the preferred device and the VVC platform would be beneficial. Second, education to inform physicians about common troubleshooting issues could help streamline VVC encounters. Third, managing a VVC encounter similarly to standard in-person visits could allow for better patient and physician experience. For example, physicians suggested that a medical assistant or a nurse triage the patient, take vital signs, and set them up in a room, potentially at a regional VA community based outpatient clinic. Such efforts would also allow patients to receive specialty care in remote areas where only primary care is generally offered. Support staff could assist with technological issues, such as setting up the VVC encounter and addressing potential problems before the physician joins the encounter, thereby preventing delays in patient care. Finally, physicians felt that designating a day solely for CVT visits would help prevent disruption in care with in-person visits.

Theme 4: CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care. Physicians felt that VVC would help patients encountering obstacles in accessing conventional in person services, including patients in rural and underserved areas, with disabilities, or with scheduling challenges.4 Patients with chronic conditions might drive the use of virtual visits, as many of these patients are already accustomed to remote medical monitoring. Data from devices such as scales and continuous glucose monitors can be easily reviewed during VVC visits. Second, video encounters facilitate closer monitoring that some patients might otherwise skip due to significant travel barriers, especially in a rural state like New Mexico. Lastly, VVC may be more efficient than in person visits as they eliminate the need for lengthy parking, checking in, and checking out processes. Thus, if technological issues are resolved, a typical physician’s day in the clinic may be more efficient with virtual visits.

Theme 5: In-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Some physicians felt in-person visits still offer unique advantages. They opined that the selection of appropriate candidates for CVT is critical. Patients requiring a physical examination should be scheduled for in person visits. For example, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who require accurate volume status assessment or patients who have recently undergone surgery and need detailed wound inspection should be seen in the clinic. In-person visits may also be preferable for patients with recurrent admissions, or those whose condition is difficult to assess; accurate assessments of such patients may help prevent readmissions. Finally, many patients are more comfortable and satisfied with in-person visits, which are perceived as a more standard or traditional process. Respondents noted that some patients felt physicians may not focus as much attention during a VVC visit as they do during in-person visits. There were also concerns that some patients feel more motivation to come to in-person visits, as they see the VA as a place to interact with other veterans and staff with whom they are familiar and comfortable.

DISCUSSION

VANMHCS physicians, which serves veterans across an expansive territory ranging from Southern Colorado to West Texas. About 4.6 million veterans reside in rural regions, constituting roughly 25% of the total veteran population, a pattern mirrored in New Mexico.13 Medicine Service physicians agreed on a number of themes: VVC user-interface issues may affect its use and effectiveness, technological literacy was important for both patients and health care staff, technical support staff roles before and during VVC visits should be standardized, CVT is likely to increase health care delivery, and in-person encounters are preferred for many patients.

This is the first study to qualitatively evaluate a diverse group of physicians at a VA medical center incorporating CVT services across specialties. A few related qualitative studies have been conducted external to VHA, generally evaluating clinicians within a single specialty. Kalicki and colleagues surveyed 16 physicians working at a large home-based primary care program in New York City between April and June 2020 to identify and explore barriers to telehealth among homebound older adults. Similarly to our study, physicians noted that many patients required assistance (family members or caregivers) with the visit, either due to technological literacy issues or medical conditions like dementia.14

Heyer and colleagues surveyed 29 oncologists at an urban academic center prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to our observations, the oncologists said telemedicine helped eliminate travel as a barrier to health care. Heyer and colleagues noted difficulty for oncologists in performing virtual physical examinations, despite training. This group did note the benefits when being selective as to which clinical issues they would handle virtually vs in person.15

Budhwani and colleagues reported that mental health professionals in an academic setting cited difficulty establishing therapeutic relationships via telehealth and felt that this affected quality of care.16 While this was not a topic during our interviews, it is reasonable to question how potentially missed nonverbal cues may impact patient assessments.

Notably, technological issues were common among all reviewed studies. These ranged from internet connectivity issues to necessary electronic devices. As mentioned, these barriers are more prevalent in rural states like New Mexico.

Limitations

All participants in this study were Medicine Service physicians of a single VA health care system, which may limit generalizability. Many of our respondents were female (69%), compared with 39.2% of active internal medicine physicians and therefore may not be representative.17 Nearly one-half of our participants only completed 1 to 4 VVC encounters, which may have contributed to the emergence of a common theme regarding technological issues. Physicians with more experience with CVT services may be more skilled at troubleshooting technological issues that arise during visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study, conducted with VANMHCS physicians, illuminated 5 key themes influencing the use and implementation of video encounters: technological issues, technological literacy, a desire for integrated support measures, perceived future growth of video telehealth, and the unique advantages of in-person visits. Addressing technological barriers and providing more extensive training may streamline CVT use. However, it is vital to recognize the unique benefits of in-person visits and consider the benefits of each modality along with patient preferences when selecting the best care venue. As health care evolves, better understanding and acting upon these themes will optimize telehealth services, particularly in rural areas. Future research should involve patients and other health care team members to further explore strategies for effective CVT service integration.

Appendix

- Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during covid-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1193. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12. doi:10.1177/1357633X16674087

- Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

- Yellowlees P, Nakagawa K, Pakyurek M, Hanson A, Elder J, Kales HC. Rapid conversion of an outpatient psychiatric clinic to a 100% virtual telepsychiatry clinic in response to covid-19. Pyschiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):749-752. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000230

- Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Roine R. Study quality and evidence of benefit in recent assessments of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(6):318-324. doi:10.1258/1357633042602053

- Osuji TA, Macias M, McMullen C, et al. Clinician perspectives on implementing video visits in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):221-226. doi:10.1089/pmr.2020.0074

- Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the Veterans Health Administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):761-768. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0143

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/nejmra1601705

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA video connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: Baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Padala KP, Wilson KB, Gauss CH, Stovall JD, Padala PR. VA video connect for clinical care in older adults in a rural state during the covid-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9)e21561. doi:10.2196/21561

- Myers US, Coulon S, Knies K, et al. Lessons learned in implementing VA video connect for evidence-based psychotherapies for anxiety and depression in the veterans healthcare administration. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;6(2):320-326. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00161-8

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Feterans Analysis and Statistics. Accessed September 18, 2024. www.va.gov/vetdata/report.asp

- Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, Ornstein KA. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2404-2411. doi:10.1111/jgs.17163

- Heyer A, Granberg RE, Rising KL, Binder AF, Gentsch AT, Handley NR. Medical oncology professionals’ perceptions of telehealth video visits. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1) e2033967. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33967

- Budhwani S, Fujioka JK, Chu C, et al. Delivering mental health care virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative evaluation of provider experiences in a scaled context. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9)e30280. doi:10.2196/30280

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2021. AAMC. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems had been increasingly focused on expanding care delivery through clinical video telehealth (CVT) services.1-3 These modalities offer clinicians and patients opportunities to interact without needing face-to-face visits. CVT services offer significant advantages to patients who encounter challenges accessing traditional face-to-face services, including those living in rural or underserved areas, individuals with mobility limitations, and those with difficulty attending appointments due to work or caregiving commitments.4 The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the expansion of CVT services to mitigate the spread of the virus.1

Despite its evident advantages, widespread adoption of CVT has encountered resistance.2 Physicians have frequently expressed concerns about the reliability and functionality of CVT platforms for scheduled encounters and frustration with inadequate training.4-6 Additionally, there is a lack trust in the technology, as physicians are unfamiliar with reimbursement or workload capture associated with CVT. Physicians have concerns that telecommunication may diminish the intangible aspects of the “art of medicine.”4 As a result, the implementation of telehealth services has been inconsistent, with successful adoption limited to specific medical and surgical specialties.4 Only recently have entire departments within major health care systems expressed interest in providing comprehensive CVT services in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides an appropriate setting for assessing clinician perceptions of telehealth services. Since 2003, the VHA has significantly expanded CVT services to eligible veterans and has used the VA Video Connect (VVC) platform since 2018.7-10 Through VVC, VA staff and clinicians may schedule video visits with patients, meet with patients through virtual face-to-face interaction, and share relevant laboratory results and imaging through screen sharing. Prior research has shown increased accessibility to care through VVC. For example, a single-site study demonstrated that VVC implementation for delivering psychotherapies significantly increased CVT encounters from 15% to 85% among veterans with anxiety and/or depression.11

The VA New Mexico Healthcare System (VANMHCS) serves a high volume of veterans living in remote and rural regions and significantly increased its use of CVT during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce in-person visits. Expectedly, this was met with a variety of challenges. Herein, we sought to assess physician perspectives, concerns, and attitudes toward VVC via semistructured interviews. Our hypothesis was that VA physicians may feel uncomfortable with video encounters but recognize the growing importance of such practices providing specialty care to veterans in rural areas.

METHODS

A semistructured interview protocol was created following discussions with physicians from the VANMHCS Medicine Service. Questions were constructed to assess the following domains: overarching views of video telehealth, perceptions of various applications for conducting VVC encounters, and barriers to the broad implementation of video telehealth. A qualitative investigation specialist aided with question development. Two pilot interviews were conducted prior to performing the interviews with the recruited participants to evaluate the quality and delivery of questions.

All VANMHCS physicians who provided outpatient care within the Department of Medicine and had completed ≥ 1 VVC encounter were eligible to participate. Invitations were disseminated via email, and follow-up emails to encourage participation were sent periodically for 2 months following the initial request. Union approval was obtained to interview employees for a research study. In total, 64 physicians were invited and 13 (20%) chose to participate. As the study did not involve assessing medical interventions among patients, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the VANMHCS Institutional Review Board. Physicians who participated in this study were informed that their responses would be used for reporting purposes and could be rescinded at any time.

Data Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted by a single interviewer and recorded using Microsoft Teams. The interviews took place between February 2021 and December 2021 and lasted 5 to 15 minutes, with a mean duration of 9 minutes. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews. Interviewees were encouraged to expand on their responses to structured questions by recounting past experiences with VVC. Recorded audio was additionally transcribed via Microsoft Teams, and the research team reviewed the transcriptions to ensure accuracy.

The tracking and coding of responses to interview questions were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Initially, 5 transcripts were reviewed and responses were assessed by 2 study team members through open coding. All team members examined the 5 coded transcripts to identify differences and reach a consensus for any discrepancies. Based on recommendations from all team members regarding nuanced excerpts of transcripts, 1 study team member coded the remaining interviews. Thematic analysis was subsequently conducted according to the method described by Braun and Clarke.12 Themes were developed both deductively and inductively by reviewing the direct responses to interview questions and identifying emerging patterns of data, respectively. Indicative quotes representing each theme were carefully chosen for reporting.

RESULTS

Thirteen interviews were conducted and 9 participants (69%) were female. Participating physicians included 3 internal medicine/primary care physicians (23%), 2 nephrologists (15%), and 1 (8%) from cardiology, endocrinology, hematology, infectious diseases, palliative care, critical care, pulmonology, and sleep medicine. Years of post training experience among physicians ranged from 1 to 9 years (n = 5, 38%), 10 to 19 years (n = 3, 23%), and . 20 years (n = 5, 38%). Seven participants (54%) had conducted ≥ 5 VVC visits, with 1 physician completing > 50 video visits (Table).

Using open coding and a deductive approach to thematic analysis, 5 themes were identified: (1) VVC software and internet connection issues affected implementation; (2) patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC; (3) integration of supportive measures was desired; (4) CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care; and (5) in-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Illustrative quotes from physicians that reflect these themes can be found in the Appendix.

Theme 1: VVC software and internet connection issues affected its implementation. Most participants expressed concern about the technical challenges with VVC. Interviewees cited inconsistencies for both patients and physicians receiving emails with links to join VVC visits, which should be generated when appointments are scheduled. Some physicians were unaware of scheduled VVC visits until the day of the appointment and only received the link via email. Such issues appeared to occur regardless whether the physicians or support staff scheduled the encounter. Poor video and audio quality was also cited as significant barriers to successful VVC visits and were often not resolvable through troubleshooting efforts by physicians, patients, or support personnel. Given the limited time allotted to each patient encounter, such issues could significantly impact the physician’s ability to remain on schedule. Moreover, connectivity problems led to significant lapses, delays in audio and video transmission, and complete disconnections from the VVC encounter. This was a significant concern for participants, given the rural nature of New Mexico and the large geographical gaps in internet service throughout the state.

Theme 2: Patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC. Successful VVC appointments require high-speed Internet and compatible hardware. Physicians indicated that some patients reported difficulties with critical steps in the process, such as logging into the VVC platform or ensuring their microphones and cameras were active. Physicians also expressed concern about older veterans’ ability to utilize electronic devices, noting they may generally be less technology savvy. Additionally, physicians reported that despite offering the option of a virtual visit, many veterans preferred in-person visits, regardless of the drive time required. This appeared related to a fear of using the technology, which led veterans to believe that virtual visits do not provide the same quality of care as in-person visits.

Theme 3: Integration of supportive measures is desired. Interviewees felt that integrated VVC technical assistance and technology literacy education were imperative. First, training the patient or the patient’s caregiver on how to complete a VVC encounter using the preferred device and the VVC platform would be beneficial. Second, education to inform physicians about common troubleshooting issues could help streamline VVC encounters. Third, managing a VVC encounter similarly to standard in-person visits could allow for better patient and physician experience. For example, physicians suggested that a medical assistant or a nurse triage the patient, take vital signs, and set them up in a room, potentially at a regional VA community based outpatient clinic. Such efforts would also allow patients to receive specialty care in remote areas where only primary care is generally offered. Support staff could assist with technological issues, such as setting up the VVC encounter and addressing potential problems before the physician joins the encounter, thereby preventing delays in patient care. Finally, physicians felt that designating a day solely for CVT visits would help prevent disruption in care with in-person visits.

Theme 4: CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care. Physicians felt that VVC would help patients encountering obstacles in accessing conventional in person services, including patients in rural and underserved areas, with disabilities, or with scheduling challenges.4 Patients with chronic conditions might drive the use of virtual visits, as many of these patients are already accustomed to remote medical monitoring. Data from devices such as scales and continuous glucose monitors can be easily reviewed during VVC visits. Second, video encounters facilitate closer monitoring that some patients might otherwise skip due to significant travel barriers, especially in a rural state like New Mexico. Lastly, VVC may be more efficient than in person visits as they eliminate the need for lengthy parking, checking in, and checking out processes. Thus, if technological issues are resolved, a typical physician’s day in the clinic may be more efficient with virtual visits.

Theme 5: In-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Some physicians felt in-person visits still offer unique advantages. They opined that the selection of appropriate candidates for CVT is critical. Patients requiring a physical examination should be scheduled for in person visits. For example, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who require accurate volume status assessment or patients who have recently undergone surgery and need detailed wound inspection should be seen in the clinic. In-person visits may also be preferable for patients with recurrent admissions, or those whose condition is difficult to assess; accurate assessments of such patients may help prevent readmissions. Finally, many patients are more comfortable and satisfied with in-person visits, which are perceived as a more standard or traditional process. Respondents noted that some patients felt physicians may not focus as much attention during a VVC visit as they do during in-person visits. There were also concerns that some patients feel more motivation to come to in-person visits, as they see the VA as a place to interact with other veterans and staff with whom they are familiar and comfortable.

DISCUSSION

VANMHCS physicians, which serves veterans across an expansive territory ranging from Southern Colorado to West Texas. About 4.6 million veterans reside in rural regions, constituting roughly 25% of the total veteran population, a pattern mirrored in New Mexico.13 Medicine Service physicians agreed on a number of themes: VVC user-interface issues may affect its use and effectiveness, technological literacy was important for both patients and health care staff, technical support staff roles before and during VVC visits should be standardized, CVT is likely to increase health care delivery, and in-person encounters are preferred for many patients.

This is the first study to qualitatively evaluate a diverse group of physicians at a VA medical center incorporating CVT services across specialties. A few related qualitative studies have been conducted external to VHA, generally evaluating clinicians within a single specialty. Kalicki and colleagues surveyed 16 physicians working at a large home-based primary care program in New York City between April and June 2020 to identify and explore barriers to telehealth among homebound older adults. Similarly to our study, physicians noted that many patients required assistance (family members or caregivers) with the visit, either due to technological literacy issues or medical conditions like dementia.14

Heyer and colleagues surveyed 29 oncologists at an urban academic center prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to our observations, the oncologists said telemedicine helped eliminate travel as a barrier to health care. Heyer and colleagues noted difficulty for oncologists in performing virtual physical examinations, despite training. This group did note the benefits when being selective as to which clinical issues they would handle virtually vs in person.15

Budhwani and colleagues reported that mental health professionals in an academic setting cited difficulty establishing therapeutic relationships via telehealth and felt that this affected quality of care.16 While this was not a topic during our interviews, it is reasonable to question how potentially missed nonverbal cues may impact patient assessments.

Notably, technological issues were common among all reviewed studies. These ranged from internet connectivity issues to necessary electronic devices. As mentioned, these barriers are more prevalent in rural states like New Mexico.

Limitations

All participants in this study were Medicine Service physicians of a single VA health care system, which may limit generalizability. Many of our respondents were female (69%), compared with 39.2% of active internal medicine physicians and therefore may not be representative.17 Nearly one-half of our participants only completed 1 to 4 VVC encounters, which may have contributed to the emergence of a common theme regarding technological issues. Physicians with more experience with CVT services may be more skilled at troubleshooting technological issues that arise during visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study, conducted with VANMHCS physicians, illuminated 5 key themes influencing the use and implementation of video encounters: technological issues, technological literacy, a desire for integrated support measures, perceived future growth of video telehealth, and the unique advantages of in-person visits. Addressing technological barriers and providing more extensive training may streamline CVT use. However, it is vital to recognize the unique benefits of in-person visits and consider the benefits of each modality along with patient preferences when selecting the best care venue. As health care evolves, better understanding and acting upon these themes will optimize telehealth services, particularly in rural areas. Future research should involve patients and other health care team members to further explore strategies for effective CVT service integration.

Appendix

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems had been increasingly focused on expanding care delivery through clinical video telehealth (CVT) services.1-3 These modalities offer clinicians and patients opportunities to interact without needing face-to-face visits. CVT services offer significant advantages to patients who encounter challenges accessing traditional face-to-face services, including those living in rural or underserved areas, individuals with mobility limitations, and those with difficulty attending appointments due to work or caregiving commitments.4 The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the expansion of CVT services to mitigate the spread of the virus.1

Despite its evident advantages, widespread adoption of CVT has encountered resistance.2 Physicians have frequently expressed concerns about the reliability and functionality of CVT platforms for scheduled encounters and frustration with inadequate training.4-6 Additionally, there is a lack trust in the technology, as physicians are unfamiliar with reimbursement or workload capture associated with CVT. Physicians have concerns that telecommunication may diminish the intangible aspects of the “art of medicine.”4 As a result, the implementation of telehealth services has been inconsistent, with successful adoption limited to specific medical and surgical specialties.4 Only recently have entire departments within major health care systems expressed interest in providing comprehensive CVT services in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides an appropriate setting for assessing clinician perceptions of telehealth services. Since 2003, the VHA has significantly expanded CVT services to eligible veterans and has used the VA Video Connect (VVC) platform since 2018.7-10 Through VVC, VA staff and clinicians may schedule video visits with patients, meet with patients through virtual face-to-face interaction, and share relevant laboratory results and imaging through screen sharing. Prior research has shown increased accessibility to care through VVC. For example, a single-site study demonstrated that VVC implementation for delivering psychotherapies significantly increased CVT encounters from 15% to 85% among veterans with anxiety and/or depression.11

The VA New Mexico Healthcare System (VANMHCS) serves a high volume of veterans living in remote and rural regions and significantly increased its use of CVT during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce in-person visits. Expectedly, this was met with a variety of challenges. Herein, we sought to assess physician perspectives, concerns, and attitudes toward VVC via semistructured interviews. Our hypothesis was that VA physicians may feel uncomfortable with video encounters but recognize the growing importance of such practices providing specialty care to veterans in rural areas.

METHODS

A semistructured interview protocol was created following discussions with physicians from the VANMHCS Medicine Service. Questions were constructed to assess the following domains: overarching views of video telehealth, perceptions of various applications for conducting VVC encounters, and barriers to the broad implementation of video telehealth. A qualitative investigation specialist aided with question development. Two pilot interviews were conducted prior to performing the interviews with the recruited participants to evaluate the quality and delivery of questions.

All VANMHCS physicians who provided outpatient care within the Department of Medicine and had completed ≥ 1 VVC encounter were eligible to participate. Invitations were disseminated via email, and follow-up emails to encourage participation were sent periodically for 2 months following the initial request. Union approval was obtained to interview employees for a research study. In total, 64 physicians were invited and 13 (20%) chose to participate. As the study did not involve assessing medical interventions among patients, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the VANMHCS Institutional Review Board. Physicians who participated in this study were informed that their responses would be used for reporting purposes and could be rescinded at any time.

Data Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted by a single interviewer and recorded using Microsoft Teams. The interviews took place between February 2021 and December 2021 and lasted 5 to 15 minutes, with a mean duration of 9 minutes. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews. Interviewees were encouraged to expand on their responses to structured questions by recounting past experiences with VVC. Recorded audio was additionally transcribed via Microsoft Teams, and the research team reviewed the transcriptions to ensure accuracy.

The tracking and coding of responses to interview questions were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Initially, 5 transcripts were reviewed and responses were assessed by 2 study team members through open coding. All team members examined the 5 coded transcripts to identify differences and reach a consensus for any discrepancies. Based on recommendations from all team members regarding nuanced excerpts of transcripts, 1 study team member coded the remaining interviews. Thematic analysis was subsequently conducted according to the method described by Braun and Clarke.12 Themes were developed both deductively and inductively by reviewing the direct responses to interview questions and identifying emerging patterns of data, respectively. Indicative quotes representing each theme were carefully chosen for reporting.

RESULTS

Thirteen interviews were conducted and 9 participants (69%) were female. Participating physicians included 3 internal medicine/primary care physicians (23%), 2 nephrologists (15%), and 1 (8%) from cardiology, endocrinology, hematology, infectious diseases, palliative care, critical care, pulmonology, and sleep medicine. Years of post training experience among physicians ranged from 1 to 9 years (n = 5, 38%), 10 to 19 years (n = 3, 23%), and . 20 years (n = 5, 38%). Seven participants (54%) had conducted ≥ 5 VVC visits, with 1 physician completing > 50 video visits (Table).

Using open coding and a deductive approach to thematic analysis, 5 themes were identified: (1) VVC software and internet connection issues affected implementation; (2) patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC; (3) integration of supportive measures was desired; (4) CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care; and (5) in-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Illustrative quotes from physicians that reflect these themes can be found in the Appendix.

Theme 1: VVC software and internet connection issues affected its implementation. Most participants expressed concern about the technical challenges with VVC. Interviewees cited inconsistencies for both patients and physicians receiving emails with links to join VVC visits, which should be generated when appointments are scheduled. Some physicians were unaware of scheduled VVC visits until the day of the appointment and only received the link via email. Such issues appeared to occur regardless whether the physicians or support staff scheduled the encounter. Poor video and audio quality was also cited as significant barriers to successful VVC visits and were often not resolvable through troubleshooting efforts by physicians, patients, or support personnel. Given the limited time allotted to each patient encounter, such issues could significantly impact the physician’s ability to remain on schedule. Moreover, connectivity problems led to significant lapses, delays in audio and video transmission, and complete disconnections from the VVC encounter. This was a significant concern for participants, given the rural nature of New Mexico and the large geographical gaps in internet service throughout the state.

Theme 2: Patient technological literacy affected veteran and physician comfort with VVC. Successful VVC appointments require high-speed Internet and compatible hardware. Physicians indicated that some patients reported difficulties with critical steps in the process, such as logging into the VVC platform or ensuring their microphones and cameras were active. Physicians also expressed concern about older veterans’ ability to utilize electronic devices, noting they may generally be less technology savvy. Additionally, physicians reported that despite offering the option of a virtual visit, many veterans preferred in-person visits, regardless of the drive time required. This appeared related to a fear of using the technology, which led veterans to believe that virtual visits do not provide the same quality of care as in-person visits.

Theme 3: Integration of supportive measures is desired. Interviewees felt that integrated VVC technical assistance and technology literacy education were imperative. First, training the patient or the patient’s caregiver on how to complete a VVC encounter using the preferred device and the VVC platform would be beneficial. Second, education to inform physicians about common troubleshooting issues could help streamline VVC encounters. Third, managing a VVC encounter similarly to standard in-person visits could allow for better patient and physician experience. For example, physicians suggested that a medical assistant or a nurse triage the patient, take vital signs, and set them up in a room, potentially at a regional VA community based outpatient clinic. Such efforts would also allow patients to receive specialty care in remote areas where only primary care is generally offered. Support staff could assist with technological issues, such as setting up the VVC encounter and addressing potential problems before the physician joins the encounter, thereby preventing delays in patient care. Finally, physicians felt that designating a day solely for CVT visits would help prevent disruption in care with in-person visits.

Theme 4: CVT services may increasingly be used to enhance access to care. Physicians felt that VVC would help patients encountering obstacles in accessing conventional in person services, including patients in rural and underserved areas, with disabilities, or with scheduling challenges.4 Patients with chronic conditions might drive the use of virtual visits, as many of these patients are already accustomed to remote medical monitoring. Data from devices such as scales and continuous glucose monitors can be easily reviewed during VVC visits. Second, video encounters facilitate closer monitoring that some patients might otherwise skip due to significant travel barriers, especially in a rural state like New Mexico. Lastly, VVC may be more efficient than in person visits as they eliminate the need for lengthy parking, checking in, and checking out processes. Thus, if technological issues are resolved, a typical physician’s day in the clinic may be more efficient with virtual visits.

Theme 5: In-person encounters afforded unique advantages over CVT. Some physicians felt in-person visits still offer unique advantages. They opined that the selection of appropriate candidates for CVT is critical. Patients requiring a physical examination should be scheduled for in person visits. For example, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who require accurate volume status assessment or patients who have recently undergone surgery and need detailed wound inspection should be seen in the clinic. In-person visits may also be preferable for patients with recurrent admissions, or those whose condition is difficult to assess; accurate assessments of such patients may help prevent readmissions. Finally, many patients are more comfortable and satisfied with in-person visits, which are perceived as a more standard or traditional process. Respondents noted that some patients felt physicians may not focus as much attention during a VVC visit as they do during in-person visits. There were also concerns that some patients feel more motivation to come to in-person visits, as they see the VA as a place to interact with other veterans and staff with whom they are familiar and comfortable.

DISCUSSION

VANMHCS physicians, which serves veterans across an expansive territory ranging from Southern Colorado to West Texas. About 4.6 million veterans reside in rural regions, constituting roughly 25% of the total veteran population, a pattern mirrored in New Mexico.13 Medicine Service physicians agreed on a number of themes: VVC user-interface issues may affect its use and effectiveness, technological literacy was important for both patients and health care staff, technical support staff roles before and during VVC visits should be standardized, CVT is likely to increase health care delivery, and in-person encounters are preferred for many patients.

This is the first study to qualitatively evaluate a diverse group of physicians at a VA medical center incorporating CVT services across specialties. A few related qualitative studies have been conducted external to VHA, generally evaluating clinicians within a single specialty. Kalicki and colleagues surveyed 16 physicians working at a large home-based primary care program in New York City between April and June 2020 to identify and explore barriers to telehealth among homebound older adults. Similarly to our study, physicians noted that many patients required assistance (family members or caregivers) with the visit, either due to technological literacy issues or medical conditions like dementia.14

Heyer and colleagues surveyed 29 oncologists at an urban academic center prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to our observations, the oncologists said telemedicine helped eliminate travel as a barrier to health care. Heyer and colleagues noted difficulty for oncologists in performing virtual physical examinations, despite training. This group did note the benefits when being selective as to which clinical issues they would handle virtually vs in person.15

Budhwani and colleagues reported that mental health professionals in an academic setting cited difficulty establishing therapeutic relationships via telehealth and felt that this affected quality of care.16 While this was not a topic during our interviews, it is reasonable to question how potentially missed nonverbal cues may impact patient assessments.

Notably, technological issues were common among all reviewed studies. These ranged from internet connectivity issues to necessary electronic devices. As mentioned, these barriers are more prevalent in rural states like New Mexico.

Limitations

All participants in this study were Medicine Service physicians of a single VA health care system, which may limit generalizability. Many of our respondents were female (69%), compared with 39.2% of active internal medicine physicians and therefore may not be representative.17 Nearly one-half of our participants only completed 1 to 4 VVC encounters, which may have contributed to the emergence of a common theme regarding technological issues. Physicians with more experience with CVT services may be more skilled at troubleshooting technological issues that arise during visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study, conducted with VANMHCS physicians, illuminated 5 key themes influencing the use and implementation of video encounters: technological issues, technological literacy, a desire for integrated support measures, perceived future growth of video telehealth, and the unique advantages of in-person visits. Addressing technological barriers and providing more extensive training may streamline CVT use. However, it is vital to recognize the unique benefits of in-person visits and consider the benefits of each modality along with patient preferences when selecting the best care venue. As health care evolves, better understanding and acting upon these themes will optimize telehealth services, particularly in rural areas. Future research should involve patients and other health care team members to further explore strategies for effective CVT service integration.

Appendix

- Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during covid-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1193. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12. doi:10.1177/1357633X16674087

- Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

- Yellowlees P, Nakagawa K, Pakyurek M, Hanson A, Elder J, Kales HC. Rapid conversion of an outpatient psychiatric clinic to a 100% virtual telepsychiatry clinic in response to covid-19. Pyschiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):749-752. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000230

- Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Roine R. Study quality and evidence of benefit in recent assessments of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(6):318-324. doi:10.1258/1357633042602053

- Osuji TA, Macias M, McMullen C, et al. Clinician perspectives on implementing video visits in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):221-226. doi:10.1089/pmr.2020.0074

- Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the Veterans Health Administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):761-768. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0143

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/nejmra1601705

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA video connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: Baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Padala KP, Wilson KB, Gauss CH, Stovall JD, Padala PR. VA video connect for clinical care in older adults in a rural state during the covid-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9)e21561. doi:10.2196/21561

- Myers US, Coulon S, Knies K, et al. Lessons learned in implementing VA video connect for evidence-based psychotherapies for anxiety and depression in the veterans healthcare administration. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;6(2):320-326. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00161-8

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Feterans Analysis and Statistics. Accessed September 18, 2024. www.va.gov/vetdata/report.asp

- Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, Ornstein KA. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2404-2411. doi:10.1111/jgs.17163

- Heyer A, Granberg RE, Rising KL, Binder AF, Gentsch AT, Handley NR. Medical oncology professionals’ perceptions of telehealth video visits. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1) e2033967. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33967

- Budhwani S, Fujioka JK, Chu C, et al. Delivering mental health care virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative evaluation of provider experiences in a scaled context. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9)e30280. doi:10.2196/30280

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2021. AAMC. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021

- Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during covid-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1193. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12. doi:10.1177/1357633X16674087

- Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

- Yellowlees P, Nakagawa K, Pakyurek M, Hanson A, Elder J, Kales HC. Rapid conversion of an outpatient psychiatric clinic to a 100% virtual telepsychiatry clinic in response to covid-19. Pyschiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):749-752. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000230

- Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Roine R. Study quality and evidence of benefit in recent assessments of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(6):318-324. doi:10.1258/1357633042602053

- Osuji TA, Macias M, McMullen C, et al. Clinician perspectives on implementing video visits in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):221-226. doi:10.1089/pmr.2020.0074

- Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the Veterans Health Administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):761-768. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0143

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/nejmra1601705

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA video connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: Baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Padala KP, Wilson KB, Gauss CH, Stovall JD, Padala PR. VA video connect for clinical care in older adults in a rural state during the covid-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9)e21561. doi:10.2196/21561

- Myers US, Coulon S, Knies K, et al. Lessons learned in implementing VA video connect for evidence-based psychotherapies for anxiety and depression in the veterans healthcare administration. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;6(2):320-326. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00161-8

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Feterans Analysis and Statistics. Accessed September 18, 2024. www.va.gov/vetdata/report.asp

- Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, Ornstein KA. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2404-2411. doi:10.1111/jgs.17163

- Heyer A, Granberg RE, Rising KL, Binder AF, Gentsch AT, Handley NR. Medical oncology professionals’ perceptions of telehealth video visits. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1) e2033967. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33967

- Budhwani S, Fujioka JK, Chu C, et al. Delivering mental health care virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative evaluation of provider experiences in a scaled context. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9)e30280. doi:10.2196/30280

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2021. AAMC. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters

Physician Attitudes About Veterans Affairs Video Connect Encounters