User login

Teens with PID underscreened for HIV, syphilis

CHICAGO – Adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) were unlikely to be screened for HIV or syphilis, and many didn’t receive an appropriate antibiotic regimen, according to a recent study reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Patients who were sent home rather than admitted were especially likely to miss screening, as were Hispanic patients and those with private insurance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strongly recommends that all women diagnosed with PID be tested for HIV, and that high-risk individuals also be tested for syphilis, wrote Amanda Jichlinski, MD, and her coauthors at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

The study, presented during a poster session, used data from the national Pediatric Health Information System database from 2010 to 2015. A total of 10,698 records with a diagnostic code for PID were included; patients were females aged 12-21 years seen in a pediatric emergency department.

In addition to the primary outcome of syphilis and HIV testing, the authors also looked at whether antibiotic administration for PID was in line with CDC recommendations – and it wasn’t. “Fewer than half of patients in the ED received antibiotic regimens adherent to CDC guidelines,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors.

Forty-six percent of patients received ceftriaxone and doxycycline, 21% received ceftriaxone and azithromycin, and 6% received ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Ceftriaxone monotherapy was given to 15% of patients. One in 10 patients with a PID diagnosis received no antibiotic at all; 2% of patients received some other regimen.

The researchers used multivariable analysis to examine separately which patient and hospital characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of testing for both HIV and syphilis. With white, non-Hispanic adolescents used as the referent, Hispanic females with PID were less likely to receive screening for either HIV or syphilis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.8 for both; 95% confidence interval, 0.7-1.0 for both).

In contrast, black non-Hispanic females were screened more often; the aOR for HIV screening was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.6), and the aOR for syphilis screening was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6-2.0) for this group of adolescents.

Patients were dichotomized into older (17-21 years of age; n = 4,737, 44%) and younger (12-16 years of age; n = 5,961, 56%) age groups; younger patients were slightly more likely to receive HIV (aOR, 1.2) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) screening.

Just under a third of patients in the study were seen in a hospital with fewer than 300 beds, and these facilities were more likely to screen for HIV (aOR, 1.4) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) than the larger hospitals.

By far the largest predictor of whether HIV and syphilis screening was done, though, was a hospital admission. Patients who were admitted (n = 4,043, 38%) were 7 times more likely to be screened for HIV and 4.6 times more likely to be screened for syphilis than those who were sent home from the emergency department.

Although the large, nationally representative study had many strengths, Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors acknowledged that the data they were provided couldn’t account for medication that was prescribed, rather than administered in the emergency department. Also, the results may not be generalizable to adolescents treated in nonpediatric emergency departments or other facilities, such as urgent care centers.

“Adolescents with PID are underscreened for HIV and syphilis,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors. They called for pediatricians to receive more education about management of PID in adolescents. From a practical perspective, the investigators also suggested incorporating order sets for sexually transmitted infection testing and antibiotic administration into electronic medical records; in this way, a PID diagnosis code would trigger simplified testing and treatment choices.

Dr. Jichlinski reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Monika Goyal, MD, senior author on the study, reported funding support by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Goyal also holds an appointment at the George Washington University, Washington.

SOURCE: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine.

CHICAGO – Adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) were unlikely to be screened for HIV or syphilis, and many didn’t receive an appropriate antibiotic regimen, according to a recent study reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Patients who were sent home rather than admitted were especially likely to miss screening, as were Hispanic patients and those with private insurance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strongly recommends that all women diagnosed with PID be tested for HIV, and that high-risk individuals also be tested for syphilis, wrote Amanda Jichlinski, MD, and her coauthors at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

The study, presented during a poster session, used data from the national Pediatric Health Information System database from 2010 to 2015. A total of 10,698 records with a diagnostic code for PID were included; patients were females aged 12-21 years seen in a pediatric emergency department.

In addition to the primary outcome of syphilis and HIV testing, the authors also looked at whether antibiotic administration for PID was in line with CDC recommendations – and it wasn’t. “Fewer than half of patients in the ED received antibiotic regimens adherent to CDC guidelines,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors.

Forty-six percent of patients received ceftriaxone and doxycycline, 21% received ceftriaxone and azithromycin, and 6% received ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Ceftriaxone monotherapy was given to 15% of patients. One in 10 patients with a PID diagnosis received no antibiotic at all; 2% of patients received some other regimen.

The researchers used multivariable analysis to examine separately which patient and hospital characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of testing for both HIV and syphilis. With white, non-Hispanic adolescents used as the referent, Hispanic females with PID were less likely to receive screening for either HIV or syphilis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.8 for both; 95% confidence interval, 0.7-1.0 for both).

In contrast, black non-Hispanic females were screened more often; the aOR for HIV screening was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.6), and the aOR for syphilis screening was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6-2.0) for this group of adolescents.

Patients were dichotomized into older (17-21 years of age; n = 4,737, 44%) and younger (12-16 years of age; n = 5,961, 56%) age groups; younger patients were slightly more likely to receive HIV (aOR, 1.2) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) screening.

Just under a third of patients in the study were seen in a hospital with fewer than 300 beds, and these facilities were more likely to screen for HIV (aOR, 1.4) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) than the larger hospitals.

By far the largest predictor of whether HIV and syphilis screening was done, though, was a hospital admission. Patients who were admitted (n = 4,043, 38%) were 7 times more likely to be screened for HIV and 4.6 times more likely to be screened for syphilis than those who were sent home from the emergency department.

Although the large, nationally representative study had many strengths, Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors acknowledged that the data they were provided couldn’t account for medication that was prescribed, rather than administered in the emergency department. Also, the results may not be generalizable to adolescents treated in nonpediatric emergency departments or other facilities, such as urgent care centers.

“Adolescents with PID are underscreened for HIV and syphilis,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors. They called for pediatricians to receive more education about management of PID in adolescents. From a practical perspective, the investigators also suggested incorporating order sets for sexually transmitted infection testing and antibiotic administration into electronic medical records; in this way, a PID diagnosis code would trigger simplified testing and treatment choices.

Dr. Jichlinski reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Monika Goyal, MD, senior author on the study, reported funding support by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Goyal also holds an appointment at the George Washington University, Washington.

SOURCE: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine.

CHICAGO – Adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) were unlikely to be screened for HIV or syphilis, and many didn’t receive an appropriate antibiotic regimen, according to a recent study reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Patients who were sent home rather than admitted were especially likely to miss screening, as were Hispanic patients and those with private insurance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strongly recommends that all women diagnosed with PID be tested for HIV, and that high-risk individuals also be tested for syphilis, wrote Amanda Jichlinski, MD, and her coauthors at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

The study, presented during a poster session, used data from the national Pediatric Health Information System database from 2010 to 2015. A total of 10,698 records with a diagnostic code for PID were included; patients were females aged 12-21 years seen in a pediatric emergency department.

In addition to the primary outcome of syphilis and HIV testing, the authors also looked at whether antibiotic administration for PID was in line with CDC recommendations – and it wasn’t. “Fewer than half of patients in the ED received antibiotic regimens adherent to CDC guidelines,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors.

Forty-six percent of patients received ceftriaxone and doxycycline, 21% received ceftriaxone and azithromycin, and 6% received ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Ceftriaxone monotherapy was given to 15% of patients. One in 10 patients with a PID diagnosis received no antibiotic at all; 2% of patients received some other regimen.

The researchers used multivariable analysis to examine separately which patient and hospital characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of testing for both HIV and syphilis. With white, non-Hispanic adolescents used as the referent, Hispanic females with PID were less likely to receive screening for either HIV or syphilis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.8 for both; 95% confidence interval, 0.7-1.0 for both).

In contrast, black non-Hispanic females were screened more often; the aOR for HIV screening was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.6), and the aOR for syphilis screening was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6-2.0) for this group of adolescents.

Patients were dichotomized into older (17-21 years of age; n = 4,737, 44%) and younger (12-16 years of age; n = 5,961, 56%) age groups; younger patients were slightly more likely to receive HIV (aOR, 1.2) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) screening.

Just under a third of patients in the study were seen in a hospital with fewer than 300 beds, and these facilities were more likely to screen for HIV (aOR, 1.4) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) than the larger hospitals.

By far the largest predictor of whether HIV and syphilis screening was done, though, was a hospital admission. Patients who were admitted (n = 4,043, 38%) were 7 times more likely to be screened for HIV and 4.6 times more likely to be screened for syphilis than those who were sent home from the emergency department.

Although the large, nationally representative study had many strengths, Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors acknowledged that the data they were provided couldn’t account for medication that was prescribed, rather than administered in the emergency department. Also, the results may not be generalizable to adolescents treated in nonpediatric emergency departments or other facilities, such as urgent care centers.

“Adolescents with PID are underscreened for HIV and syphilis,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors. They called for pediatricians to receive more education about management of PID in adolescents. From a practical perspective, the investigators also suggested incorporating order sets for sexually transmitted infection testing and antibiotic administration into electronic medical records; in this way, a PID diagnosis code would trigger simplified testing and treatment choices.

Dr. Jichlinski reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Monika Goyal, MD, senior author on the study, reported funding support by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Goyal also holds an appointment at the George Washington University, Washington.

SOURCE: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine.

REPORTING FROM AAP 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Hispanic females were least likely to be screened (adjusted OR, 0.8), compared with non-Hispanic white females.

Study details: Retrospective study of 10,698 adolescent patients with PID from a national database.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the National Institute of Child Health and Development. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine

Unplanned cesareans more common with excess gestational weight gain

MONTREAL – The risk for unplanned cesarean delivery is increased when maternal gestational weight gain exceeds the recommended amount – as it does in almost half of pregnancies in the United States.

In a new analysis of data from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II), women with excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) were found to have an adjusted odds ratio of 1.61 for unplanned cesarean delivery, compared with women with adequate GWG (95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.33; P = .013).

Maternal obesity is known to be a risk factor for cesarean delivery, at least in part because excess adipose tissue may interfere with the normal ability of the cervix to thin and dilate with contractions, said Mr. Francescon, a medical student at Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens. Labor can be prolonged, and it’s often difficult to monitor fetal activity with external activity, he said.

To see whether unplanned cesarean deliveries were associated with excess GWG, Mr. Francescon and his collaborators included data from 2,107 of the 3,033 respondents to the IFPS II, excluding those with missing data and those with planned cesarean deliveries.

Weight gain was grouped into three categories – adequate, inadequate, and excessive – according to guidelines set by the Institute of Medicine. The odds of an unplanned cesarean delivery were adjusted by using multivariable analysis that took into account ethnicity, education, poverty status, parity, and previous obstetric history. The statistical analysis also accounted for the presence of gestational diabetes and the type of birth attendant.

A total of 1,038 women (49.3%) had excessive GWG according to the IOM guidelines, and 287 women (13.6%) overall had an unplanned cesarean delivery. After adjusting for the potentially confounding variables, only excessive weight gain was significantly associated with the risk for unplanned cesarean delivery; those with inadequate weight gain had an odds ratio of 1.03 (95% CI, 0.63-1.69; not significant).

, but rather were attended by a nonobstetrician physician or a midwife, said Mr. Francescon. After excluding patients who planned to have cesarean deliveries, 257 of 1,385 (15.6%) of patients seeing obstetricians had unplanned cesarean deliveries; this figure was 9% for nonobstetrician physicians and 4.1% for midwives/nurse midwives.

“This finding suggests that psychosocial factors, such as the bond formed between caregiver and patient, could also potentially influence birthing patterns,” wrote Mr. Francescon and his collaborators.

“Our study findings are supported by previous studies that found increased likelihood of cesarean delivery among women with excessive GWG,” said the investigators.

The study had a large sample size, used well-tested survey instruments, and could include many variables in statistical analysis, all strengths, wrote Mr. Francescon and his coauthors. However, there remained the potential for volunteer bias and recall bias. In addition, weight gain carries social stigma, which could have influence the self-reported results.

“Gestational weight gain is a modifiable risk factor for unplanned cesarean delivery,” Mr. Francescon said. He and his collaborators propose that a comprehensive plan of dietary and lifestyle modifications beginning pre-conception, together with enhanced patient and provider awareness of the risk of unplanned cesarean deliveries with excess gestational weight gain, could help reduce the number of unplanned cesarean deliveries.

The data for the study were provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mr. Francescon reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Francescon J. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract P495.

MONTREAL – The risk for unplanned cesarean delivery is increased when maternal gestational weight gain exceeds the recommended amount – as it does in almost half of pregnancies in the United States.

In a new analysis of data from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II), women with excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) were found to have an adjusted odds ratio of 1.61 for unplanned cesarean delivery, compared with women with adequate GWG (95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.33; P = .013).

Maternal obesity is known to be a risk factor for cesarean delivery, at least in part because excess adipose tissue may interfere with the normal ability of the cervix to thin and dilate with contractions, said Mr. Francescon, a medical student at Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens. Labor can be prolonged, and it’s often difficult to monitor fetal activity with external activity, he said.

To see whether unplanned cesarean deliveries were associated with excess GWG, Mr. Francescon and his collaborators included data from 2,107 of the 3,033 respondents to the IFPS II, excluding those with missing data and those with planned cesarean deliveries.

Weight gain was grouped into three categories – adequate, inadequate, and excessive – according to guidelines set by the Institute of Medicine. The odds of an unplanned cesarean delivery were adjusted by using multivariable analysis that took into account ethnicity, education, poverty status, parity, and previous obstetric history. The statistical analysis also accounted for the presence of gestational diabetes and the type of birth attendant.

A total of 1,038 women (49.3%) had excessive GWG according to the IOM guidelines, and 287 women (13.6%) overall had an unplanned cesarean delivery. After adjusting for the potentially confounding variables, only excessive weight gain was significantly associated with the risk for unplanned cesarean delivery; those with inadequate weight gain had an odds ratio of 1.03 (95% CI, 0.63-1.69; not significant).

, but rather were attended by a nonobstetrician physician or a midwife, said Mr. Francescon. After excluding patients who planned to have cesarean deliveries, 257 of 1,385 (15.6%) of patients seeing obstetricians had unplanned cesarean deliveries; this figure was 9% for nonobstetrician physicians and 4.1% for midwives/nurse midwives.

“This finding suggests that psychosocial factors, such as the bond formed between caregiver and patient, could also potentially influence birthing patterns,” wrote Mr. Francescon and his collaborators.

“Our study findings are supported by previous studies that found increased likelihood of cesarean delivery among women with excessive GWG,” said the investigators.

The study had a large sample size, used well-tested survey instruments, and could include many variables in statistical analysis, all strengths, wrote Mr. Francescon and his coauthors. However, there remained the potential for volunteer bias and recall bias. In addition, weight gain carries social stigma, which could have influence the self-reported results.

“Gestational weight gain is a modifiable risk factor for unplanned cesarean delivery,” Mr. Francescon said. He and his collaborators propose that a comprehensive plan of dietary and lifestyle modifications beginning pre-conception, together with enhanced patient and provider awareness of the risk of unplanned cesarean deliveries with excess gestational weight gain, could help reduce the number of unplanned cesarean deliveries.

The data for the study were provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mr. Francescon reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Francescon J. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract P495.

MONTREAL – The risk for unplanned cesarean delivery is increased when maternal gestational weight gain exceeds the recommended amount – as it does in almost half of pregnancies in the United States.

In a new analysis of data from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II), women with excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) were found to have an adjusted odds ratio of 1.61 for unplanned cesarean delivery, compared with women with adequate GWG (95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.33; P = .013).

Maternal obesity is known to be a risk factor for cesarean delivery, at least in part because excess adipose tissue may interfere with the normal ability of the cervix to thin and dilate with contractions, said Mr. Francescon, a medical student at Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens. Labor can be prolonged, and it’s often difficult to monitor fetal activity with external activity, he said.

To see whether unplanned cesarean deliveries were associated with excess GWG, Mr. Francescon and his collaborators included data from 2,107 of the 3,033 respondents to the IFPS II, excluding those with missing data and those with planned cesarean deliveries.

Weight gain was grouped into three categories – adequate, inadequate, and excessive – according to guidelines set by the Institute of Medicine. The odds of an unplanned cesarean delivery were adjusted by using multivariable analysis that took into account ethnicity, education, poverty status, parity, and previous obstetric history. The statistical analysis also accounted for the presence of gestational diabetes and the type of birth attendant.

A total of 1,038 women (49.3%) had excessive GWG according to the IOM guidelines, and 287 women (13.6%) overall had an unplanned cesarean delivery. After adjusting for the potentially confounding variables, only excessive weight gain was significantly associated with the risk for unplanned cesarean delivery; those with inadequate weight gain had an odds ratio of 1.03 (95% CI, 0.63-1.69; not significant).

, but rather were attended by a nonobstetrician physician or a midwife, said Mr. Francescon. After excluding patients who planned to have cesarean deliveries, 257 of 1,385 (15.6%) of patients seeing obstetricians had unplanned cesarean deliveries; this figure was 9% for nonobstetrician physicians and 4.1% for midwives/nurse midwives.

“This finding suggests that psychosocial factors, such as the bond formed between caregiver and patient, could also potentially influence birthing patterns,” wrote Mr. Francescon and his collaborators.

“Our study findings are supported by previous studies that found increased likelihood of cesarean delivery among women with excessive GWG,” said the investigators.

The study had a large sample size, used well-tested survey instruments, and could include many variables in statistical analysis, all strengths, wrote Mr. Francescon and his coauthors. However, there remained the potential for volunteer bias and recall bias. In addition, weight gain carries social stigma, which could have influence the self-reported results.

“Gestational weight gain is a modifiable risk factor for unplanned cesarean delivery,” Mr. Francescon said. He and his collaborators propose that a comprehensive plan of dietary and lifestyle modifications beginning pre-conception, together with enhanced patient and provider awareness of the risk of unplanned cesarean deliveries with excess gestational weight gain, could help reduce the number of unplanned cesarean deliveries.

The data for the study were provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mr. Francescon reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Francescon J. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract P495.

REPORTING FROM NAPCRG 2017

Key clinical point: The risk for an unplanned cesarean delivery rose with excess gestational weight gain.

Major finding: The adjusted odds ratio for unplanned cesarean was 1.61 for those with excess GWG (P = .013).

Study details: Retrospective analysis of 2,107 responses to the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPSII).

Disclosures: Study data were provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mr. Francescon reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Francescon J. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract P495.

Length of stay shorter with admission to family medicine, not hospitalist, service

MONTREAL – When a family medicine teaching service provided hospital care for local patients, length of stay was almost a third shorter than when care was provided by the hospitalist internal medicine service at a large tertiary care hospital.

What made the difference in length of stay? “,” said Gregory Garrison, MD, of the department of family medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He noted that readmission rates weren’t higher for the patients cared for by the family medicine inpatient service.

The primary outcome measures were length of stay and readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, Dr. Garrison said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

A total of 3,125 admissions were seen for 2,138 unique patients. Most admissions (2,651; 84.8%) were for the family medicine service. Demographic characteristics and readmission rates were similar between admissions to the two services, but “hospitalist internal medicine patients were perhaps slightly sicker,” said Dr. Garrison. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was 4 for the family medicine admissions and 5.6 for the hospitalist internal medicine admissions (P less than .001). Also, the patients admitted to the hospitalist service were slightly more likely to have had a previous hospital admission within the prior 12 months.

Examining the unadjusted data, Dr. Garrison and his colleagues found that the family medicine patients had a shorter length of stay, with a mean 2.5 days and a median 1.8 days, compared with the mean 3.8 days and median 2.7 days spent in hospital for the hospitalist internal medicine patients.

The difference remained significant after multivariable analysis to control for several potentially confounding factors, including patient demographics, prior health care utilization, disposition, readmissions, and Charlson comorbidity score.

The adjusted figures showed that length of stay was 31.8% longer for admissions to the hospitalist internal medicine service than for the family medicine service.

In discussion, Dr. Garrison said that he and his colleagues believe that the physicians, social workers, and clinical assistants who make up the family medicine service really understand the “outpatient resources that can be marshaled to help local patients with the transition from hospital to home.”

In practical terms, this can mean that a social worker knows which skilled nursing facilities are likely to accept a Friday admission, or that a physician understands community resources that can help an elderly patient return to her home with a little extra support, he said.

Another practicality, is that “the lack of a census cap on the family medicine inpatient service may incentivize rapid turnover,” he added.

Dr. Garrison reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32

MONTREAL – When a family medicine teaching service provided hospital care for local patients, length of stay was almost a third shorter than when care was provided by the hospitalist internal medicine service at a large tertiary care hospital.

What made the difference in length of stay? “,” said Gregory Garrison, MD, of the department of family medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He noted that readmission rates weren’t higher for the patients cared for by the family medicine inpatient service.

The primary outcome measures were length of stay and readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, Dr. Garrison said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

A total of 3,125 admissions were seen for 2,138 unique patients. Most admissions (2,651; 84.8%) were for the family medicine service. Demographic characteristics and readmission rates were similar between admissions to the two services, but “hospitalist internal medicine patients were perhaps slightly sicker,” said Dr. Garrison. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was 4 for the family medicine admissions and 5.6 for the hospitalist internal medicine admissions (P less than .001). Also, the patients admitted to the hospitalist service were slightly more likely to have had a previous hospital admission within the prior 12 months.

Examining the unadjusted data, Dr. Garrison and his colleagues found that the family medicine patients had a shorter length of stay, with a mean 2.5 days and a median 1.8 days, compared with the mean 3.8 days and median 2.7 days spent in hospital for the hospitalist internal medicine patients.

The difference remained significant after multivariable analysis to control for several potentially confounding factors, including patient demographics, prior health care utilization, disposition, readmissions, and Charlson comorbidity score.

The adjusted figures showed that length of stay was 31.8% longer for admissions to the hospitalist internal medicine service than for the family medicine service.

In discussion, Dr. Garrison said that he and his colleagues believe that the physicians, social workers, and clinical assistants who make up the family medicine service really understand the “outpatient resources that can be marshaled to help local patients with the transition from hospital to home.”

In practical terms, this can mean that a social worker knows which skilled nursing facilities are likely to accept a Friday admission, or that a physician understands community resources that can help an elderly patient return to her home with a little extra support, he said.

Another practicality, is that “the lack of a census cap on the family medicine inpatient service may incentivize rapid turnover,” he added.

Dr. Garrison reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32

MONTREAL – When a family medicine teaching service provided hospital care for local patients, length of stay was almost a third shorter than when care was provided by the hospitalist internal medicine service at a large tertiary care hospital.

What made the difference in length of stay? “,” said Gregory Garrison, MD, of the department of family medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He noted that readmission rates weren’t higher for the patients cared for by the family medicine inpatient service.

The primary outcome measures were length of stay and readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, Dr. Garrison said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

A total of 3,125 admissions were seen for 2,138 unique patients. Most admissions (2,651; 84.8%) were for the family medicine service. Demographic characteristics and readmission rates were similar between admissions to the two services, but “hospitalist internal medicine patients were perhaps slightly sicker,” said Dr. Garrison. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was 4 for the family medicine admissions and 5.6 for the hospitalist internal medicine admissions (P less than .001). Also, the patients admitted to the hospitalist service were slightly more likely to have had a previous hospital admission within the prior 12 months.

Examining the unadjusted data, Dr. Garrison and his colleagues found that the family medicine patients had a shorter length of stay, with a mean 2.5 days and a median 1.8 days, compared with the mean 3.8 days and median 2.7 days spent in hospital for the hospitalist internal medicine patients.

The difference remained significant after multivariable analysis to control for several potentially confounding factors, including patient demographics, prior health care utilization, disposition, readmissions, and Charlson comorbidity score.

The adjusted figures showed that length of stay was 31.8% longer for admissions to the hospitalist internal medicine service than for the family medicine service.

In discussion, Dr. Garrison said that he and his colleagues believe that the physicians, social workers, and clinical assistants who make up the family medicine service really understand the “outpatient resources that can be marshaled to help local patients with the transition from hospital to home.”

In practical terms, this can mean that a social worker knows which skilled nursing facilities are likely to accept a Friday admission, or that a physician understands community resources that can help an elderly patient return to her home with a little extra support, he said.

Another practicality, is that “the lack of a census cap on the family medicine inpatient service may incentivize rapid turnover,” he added.

Dr. Garrison reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32

REPORTING FROM NAPCRG 2017

Key clinical point: Patients’ length of stay was shorter when they were cared for by family medicine doctors and not hospitalists.

Major finding: After multivariable analysis, the adjusted length of stay was 31.8% longer for patients on the hospitalist service than on the family medicine inpatient service.

Study details: A retrospective review of records from 3,125 admissions of 2,138 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Garrison reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

Source: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32.

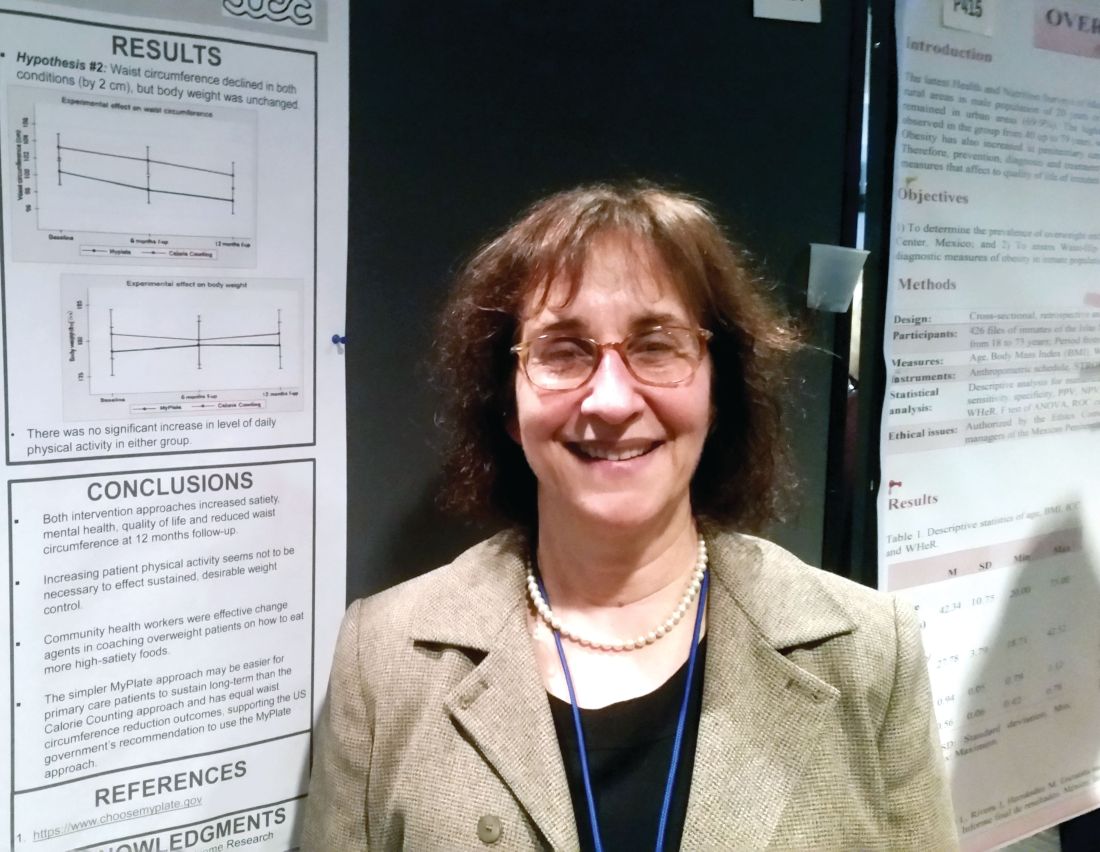

MyPlate as effective as calorie counting after 12 months

MONTREAL – The high-satiety MyPlate approach to weight loss reduced waist circumference, improved mental health and quality of life, and increased satiety 12 months into a study that found the strategy as effective as a conventional calorie-counting approach.

After 12 months, waist circumference had decreased by about 2 cm in study participants, regardless of whether they used the MyPlate approach or counted calories. Body weight was unchanged after a year in both groups.

“The simpler MyPlate approach may be easier for primary care patients to sustain long-term than the calorie-counting approach and has equal waist circumference reduction outcomes, supporting the U.S. government’s recommendation to use the MyPlate approach,” wrote Lillian Gelberg, MD, and her collaborators.

MyPlate recommends eating more fruits and vegetables, making half of grain choices whole grain, replacing sugary drinks with water, limiting sodium intake.

Over the study period, neither group significantly increased their physical activity. “Increasing patient physical activity seems not to be necessary to effect sustained, desirable weight control,” the researchers wrote.

The comparative effectiveness study compared the two weight loss approaches in 261 primarily Hispanic patients at two federally qualified health center clinics.

The primary outcome in the patient-centered study was perceived satiety; secondary outcomes included waist circumference, weight, mental health, quality of life, intake of sugary drinks, water intake, and exercise.

Participants received 11 health coaching sessions from bilingual community health workers, dubbed “promotoras,” over a 6 month period. “Community health workers were effective change agents in coaching overweight patients on how to eat more high-satiety foods,” Dr. Gelberg and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Two of the sessions were hour-long home-based sessions; the MyPlate group also received two hour-long cooking demonstrations. Both groups received two hour-long group education sessions, as well as a total of seven 20-minute telephone coaching sessions.

Most participants (56%) were in five sessions during the study period, with a quarter completing 10 of the 11 sessions. At 12 months, 80% of study members were still being followed.

Overall, 95% of the participants were female, and about half (n = 126) did not have a high school diploma or equivalent.

A total of 86% were Hispanic, and Spanish was the preferred language for about three quarters of all participants. Most patients (82%) were born outside the United States.

The mean age at enrollment was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 for about half (46%) of the patients; 5% had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more.

In an interview, Dr. Gelberg, professor of family medicine and public health and management at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that the investigators had hypothesized that the MyPlate approach would be easier for patients to follow, because it’s easier to understand and less cumbersome in terms of record keeping. The investigators did not think that one approach would result in greater reductions in body weight or waist circumference, a finding borne out by the data presented.

Both groups reduced their intake of sugary drinks and increased the amount of water they drank, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Dr. Gelberg reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

This article was updated on 2/13/18

MONTREAL – The high-satiety MyPlate approach to weight loss reduced waist circumference, improved mental health and quality of life, and increased satiety 12 months into a study that found the strategy as effective as a conventional calorie-counting approach.

After 12 months, waist circumference had decreased by about 2 cm in study participants, regardless of whether they used the MyPlate approach or counted calories. Body weight was unchanged after a year in both groups.

“The simpler MyPlate approach may be easier for primary care patients to sustain long-term than the calorie-counting approach and has equal waist circumference reduction outcomes, supporting the U.S. government’s recommendation to use the MyPlate approach,” wrote Lillian Gelberg, MD, and her collaborators.

MyPlate recommends eating more fruits and vegetables, making half of grain choices whole grain, replacing sugary drinks with water, limiting sodium intake.

Over the study period, neither group significantly increased their physical activity. “Increasing patient physical activity seems not to be necessary to effect sustained, desirable weight control,” the researchers wrote.

The comparative effectiveness study compared the two weight loss approaches in 261 primarily Hispanic patients at two federally qualified health center clinics.

The primary outcome in the patient-centered study was perceived satiety; secondary outcomes included waist circumference, weight, mental health, quality of life, intake of sugary drinks, water intake, and exercise.

Participants received 11 health coaching sessions from bilingual community health workers, dubbed “promotoras,” over a 6 month period. “Community health workers were effective change agents in coaching overweight patients on how to eat more high-satiety foods,” Dr. Gelberg and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Two of the sessions were hour-long home-based sessions; the MyPlate group also received two hour-long cooking demonstrations. Both groups received two hour-long group education sessions, as well as a total of seven 20-minute telephone coaching sessions.

Most participants (56%) were in five sessions during the study period, with a quarter completing 10 of the 11 sessions. At 12 months, 80% of study members were still being followed.

Overall, 95% of the participants were female, and about half (n = 126) did not have a high school diploma or equivalent.

A total of 86% were Hispanic, and Spanish was the preferred language for about three quarters of all participants. Most patients (82%) were born outside the United States.

The mean age at enrollment was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 for about half (46%) of the patients; 5% had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more.

In an interview, Dr. Gelberg, professor of family medicine and public health and management at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that the investigators had hypothesized that the MyPlate approach would be easier for patients to follow, because it’s easier to understand and less cumbersome in terms of record keeping. The investigators did not think that one approach would result in greater reductions in body weight or waist circumference, a finding borne out by the data presented.

Both groups reduced their intake of sugary drinks and increased the amount of water they drank, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Dr. Gelberg reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

This article was updated on 2/13/18

MONTREAL – The high-satiety MyPlate approach to weight loss reduced waist circumference, improved mental health and quality of life, and increased satiety 12 months into a study that found the strategy as effective as a conventional calorie-counting approach.

After 12 months, waist circumference had decreased by about 2 cm in study participants, regardless of whether they used the MyPlate approach or counted calories. Body weight was unchanged after a year in both groups.

“The simpler MyPlate approach may be easier for primary care patients to sustain long-term than the calorie-counting approach and has equal waist circumference reduction outcomes, supporting the U.S. government’s recommendation to use the MyPlate approach,” wrote Lillian Gelberg, MD, and her collaborators.

MyPlate recommends eating more fruits and vegetables, making half of grain choices whole grain, replacing sugary drinks with water, limiting sodium intake.

Over the study period, neither group significantly increased their physical activity. “Increasing patient physical activity seems not to be necessary to effect sustained, desirable weight control,” the researchers wrote.

The comparative effectiveness study compared the two weight loss approaches in 261 primarily Hispanic patients at two federally qualified health center clinics.

The primary outcome in the patient-centered study was perceived satiety; secondary outcomes included waist circumference, weight, mental health, quality of life, intake of sugary drinks, water intake, and exercise.

Participants received 11 health coaching sessions from bilingual community health workers, dubbed “promotoras,” over a 6 month period. “Community health workers were effective change agents in coaching overweight patients on how to eat more high-satiety foods,” Dr. Gelberg and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Two of the sessions were hour-long home-based sessions; the MyPlate group also received two hour-long cooking demonstrations. Both groups received two hour-long group education sessions, as well as a total of seven 20-minute telephone coaching sessions.

Most participants (56%) were in five sessions during the study period, with a quarter completing 10 of the 11 sessions. At 12 months, 80% of study members were still being followed.

Overall, 95% of the participants were female, and about half (n = 126) did not have a high school diploma or equivalent.

A total of 86% were Hispanic, and Spanish was the preferred language for about three quarters of all participants. Most patients (82%) were born outside the United States.

The mean age at enrollment was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 for about half (46%) of the patients; 5% had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more.

In an interview, Dr. Gelberg, professor of family medicine and public health and management at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that the investigators had hypothesized that the MyPlate approach would be easier for patients to follow, because it’s easier to understand and less cumbersome in terms of record keeping. The investigators did not think that one approach would result in greater reductions in body weight or waist circumference, a finding borne out by the data presented.

Both groups reduced their intake of sugary drinks and increased the amount of water they drank, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Dr. Gelberg reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

This article was updated on 2/13/18

REPORTING FROM NAPCRG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 12 months, both approaches reduced waist circumference by 2 cm but didn’t result in weight loss.

Data source: Prospective randomized comparative effectiveness trial of 261 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Gelberg reported no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Comparative Effectiveness Institute.

Source: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

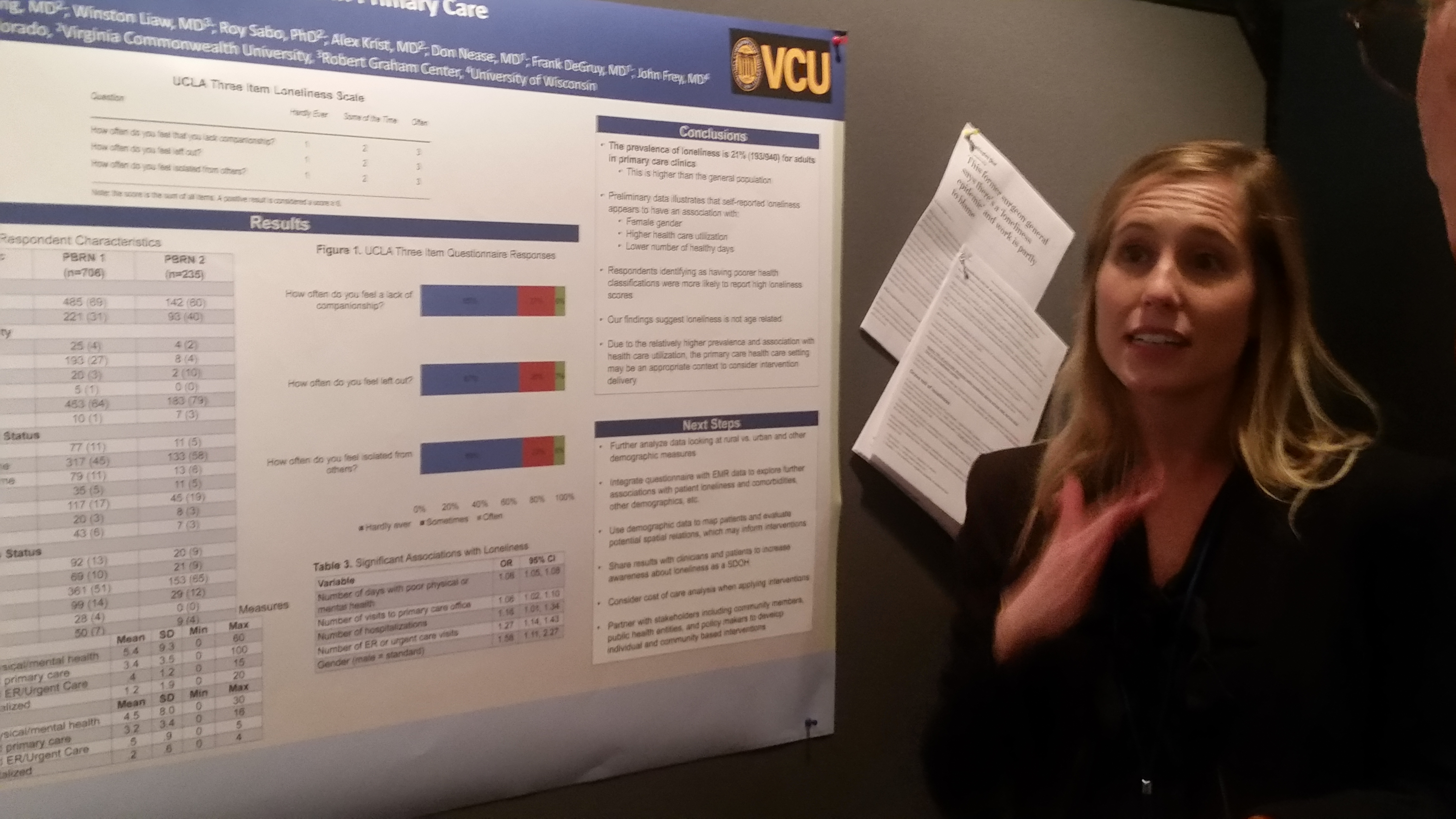

Loneliness is common, and not just in the elderly

MONTREAL – Loneliness is associated with poorer health, but isn’t necessarily more common among older adults; one in five adults in a primary care population reported being lonely, a number higher than previously reported, a study showed.

In a survey of 940 adults seeking care in primary care clinics, 193 (21%) reported loneliness, with women more likely than men to say they were lonely. “Respondents identifying as having poorer health classifications were more likely to report high loneliness scores,” said Rebecca Mullen, MD, and her colleagues in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Those who said they were lonely also had a higher level of health care utilization, and reported they had a lower number of healthy days than the respondents who didn’t report loneliness.

The study was conducted in outpatient practice-based research networks in both urban and rural settings in the states of Virginia and Colorado. Participants were adult, English-speaking primary care patients who were given the UCLA Three-Item Loneliness Scale. The scale asks how often respondents feel a lack of companionship, feel left out, and feel isolated from others; responses are “hardly ever,” “sometimes,” and “often.”

The investigators sought to determine whether high loneliness scores on this scale – the primary outcome – were correlated with health care utilization, the number of healthy days reported by patients, and demographic information. These associations were the study’s secondary outcomes.

After statistical analysis, several variables emerged as being significantly associated with high loneliness scores. These included the number of reported days with poor physical or mental health (odds ratio, 1.06), the number of primary care office visits (OR, 1.06), the number of hospitalizations (OR, 1.16), the number of emergency department or urgent care visits (OR ,1.27), and gender.

When compared with male respondents, females had an OR of 1.56 for reporting loneliness.

Race and ethnicity were not associated with a greater risk of loneliness; neither were disability or employment status, or whether the respondent was in a relationship.

And despite other studies indicating an increased prevalence of loneliness among the elderly, “our findings suggest loneliness is not age related,” wrote Dr. Mullen and her colleagues.

The investigators said they plan to examine their data further, to see if factors such as living in a rural or urban environment are associated with differences in loneliness. Going into still more detail, they plan to use demographic data to plot out respondents’ residences, and then look for spatial associations and links to other comorbidities. Integrating the questionnaire with data from the electronic record will allow Dr. Mullen and her colleagues to search for further associations as well, they said.

Finally, the investigators plan to build partnerships with the community, public health agencies, and those involved in health policy to build interventions against loneliness targeted at both the individual and the community. Some of these interventions, they said, could begin in the clinic: “[T]he primary care health care setting may be an appropriate context to consider intervention delivery.”

Dr. Mullen reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mullen R et al. Abstract P196.

MONTREAL – Loneliness is associated with poorer health, but isn’t necessarily more common among older adults; one in five adults in a primary care population reported being lonely, a number higher than previously reported, a study showed.

In a survey of 940 adults seeking care in primary care clinics, 193 (21%) reported loneliness, with women more likely than men to say they were lonely. “Respondents identifying as having poorer health classifications were more likely to report high loneliness scores,” said Rebecca Mullen, MD, and her colleagues in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Those who said they were lonely also had a higher level of health care utilization, and reported they had a lower number of healthy days than the respondents who didn’t report loneliness.

The study was conducted in outpatient practice-based research networks in both urban and rural settings in the states of Virginia and Colorado. Participants were adult, English-speaking primary care patients who were given the UCLA Three-Item Loneliness Scale. The scale asks how often respondents feel a lack of companionship, feel left out, and feel isolated from others; responses are “hardly ever,” “sometimes,” and “often.”

The investigators sought to determine whether high loneliness scores on this scale – the primary outcome – were correlated with health care utilization, the number of healthy days reported by patients, and demographic information. These associations were the study’s secondary outcomes.

After statistical analysis, several variables emerged as being significantly associated with high loneliness scores. These included the number of reported days with poor physical or mental health (odds ratio, 1.06), the number of primary care office visits (OR, 1.06), the number of hospitalizations (OR, 1.16), the number of emergency department or urgent care visits (OR ,1.27), and gender.

When compared with male respondents, females had an OR of 1.56 for reporting loneliness.

Race and ethnicity were not associated with a greater risk of loneliness; neither were disability or employment status, or whether the respondent was in a relationship.

And despite other studies indicating an increased prevalence of loneliness among the elderly, “our findings suggest loneliness is not age related,” wrote Dr. Mullen and her colleagues.

The investigators said they plan to examine their data further, to see if factors such as living in a rural or urban environment are associated with differences in loneliness. Going into still more detail, they plan to use demographic data to plot out respondents’ residences, and then look for spatial associations and links to other comorbidities. Integrating the questionnaire with data from the electronic record will allow Dr. Mullen and her colleagues to search for further associations as well, they said.

Finally, the investigators plan to build partnerships with the community, public health agencies, and those involved in health policy to build interventions against loneliness targeted at both the individual and the community. Some of these interventions, they said, could begin in the clinic: “[T]he primary care health care setting may be an appropriate context to consider intervention delivery.”

Dr. Mullen reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mullen R et al. Abstract P196.

MONTREAL – Loneliness is associated with poorer health, but isn’t necessarily more common among older adults; one in five adults in a primary care population reported being lonely, a number higher than previously reported, a study showed.

In a survey of 940 adults seeking care in primary care clinics, 193 (21%) reported loneliness, with women more likely than men to say they were lonely. “Respondents identifying as having poorer health classifications were more likely to report high loneliness scores,” said Rebecca Mullen, MD, and her colleagues in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Those who said they were lonely also had a higher level of health care utilization, and reported they had a lower number of healthy days than the respondents who didn’t report loneliness.

The study was conducted in outpatient practice-based research networks in both urban and rural settings in the states of Virginia and Colorado. Participants were adult, English-speaking primary care patients who were given the UCLA Three-Item Loneliness Scale. The scale asks how often respondents feel a lack of companionship, feel left out, and feel isolated from others; responses are “hardly ever,” “sometimes,” and “often.”

The investigators sought to determine whether high loneliness scores on this scale – the primary outcome – were correlated with health care utilization, the number of healthy days reported by patients, and demographic information. These associations were the study’s secondary outcomes.

After statistical analysis, several variables emerged as being significantly associated with high loneliness scores. These included the number of reported days with poor physical or mental health (odds ratio, 1.06), the number of primary care office visits (OR, 1.06), the number of hospitalizations (OR, 1.16), the number of emergency department or urgent care visits (OR ,1.27), and gender.

When compared with male respondents, females had an OR of 1.56 for reporting loneliness.

Race and ethnicity were not associated with a greater risk of loneliness; neither were disability or employment status, or whether the respondent was in a relationship.

And despite other studies indicating an increased prevalence of loneliness among the elderly, “our findings suggest loneliness is not age related,” wrote Dr. Mullen and her colleagues.

The investigators said they plan to examine their data further, to see if factors such as living in a rural or urban environment are associated with differences in loneliness. Going into still more detail, they plan to use demographic data to plot out respondents’ residences, and then look for spatial associations and links to other comorbidities. Integrating the questionnaire with data from the electronic record will allow Dr. Mullen and her colleagues to search for further associations as well, they said.

Finally, the investigators plan to build partnerships with the community, public health agencies, and those involved in health policy to build interventions against loneliness targeted at both the individual and the community. Some of these interventions, they said, could begin in the clinic: “[T]he primary care health care setting may be an appropriate context to consider intervention delivery.”

Dr. Mullen reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mullen R et al. Abstract P196.

REPORTING FROM NAPCRG 2017

Key clinical point: One in five adults – and more women than men – reported loneliness.

Major finding: Of 940 adults surveyed, 193 (21%) reported being lonely.

Study details: A prospective survey of 940 adults seeking care in primary care clinics.

Disclosures: Dr. Mullen reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Bright Futures 4th Edition gets a clinical refresher

CHICAGO – Bracing his audience for a whirlwind tour of the many updates to the fourth edition of Bright Futures, Joseph F. Hagan Jr., MD, said that it’s still completely possible to fit Bright Futures visits into a clinic day.

“I practice primary care pediatrics,” said Dr. Hagan, a pediatrician in private practice and clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Vermont, both in Burlington. “I said to my Bright Futures colleagues, if I didn’t think I could do this in 18 minutes, I wouldn’t ask you to do it.”

The Bright Futures framework, described by Dr. Hagan as the health prevention and disease prevention component of the medical home for children and youth, emerges in the Fourth Edition with a significant evidence-based refresher. The changes and updates are built within the existing framework and encompass surveillance and screening recommendations as well as anticipatory guidance. All content, including family handouts, has been updated, said Dr. Hagan, a coeditor of the Fourth Edition of Bright Futures. He spoke at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

New clinical content

“What’s new? Maternal depression screening is new,” said Dr. Hagan, noting that the recommendation has long been under discussion. Now, supported by a 2016 United States Preventative Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation that carries a grade B level of evidence, all mothers should be screened for depression at the 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-month Bright Futures visits.

However, he said, know your local regulations. “State mandates to do more might overrule this.” And conversely, “Just because we’re doing it universally until 6 months doesn’t mean you couldn’t selectively screen later if you have concerns.”

Safe sleep is another area with new clinical focus, he said. The new recommendation for the child to sleep in the parent’s room for “at least 6 months” draws on data from European studies showing lower mortality for children who share a room with parents during this period.

Clinicians should continue to recommend that parents not sleep with their infants in couches, chairs, or beds. As before, parents should be told not to have loose blankets, stuffed toys, or crib bumpers in their babies’ cribs. Another key message, said Dr. Hagan, is that “There is no such thing as safe ‘breast-sleeping.’ ”

Parents should be reminded not to swaddle at nap – or bedtime. The risk is that even a 2-month-old infant may be capable of wriggling over from back to front, and a swaddled infant whose hands are trapped may not be able to move to protect her airway once prone. “Swaddle for comfort, swaddle for crying, swaddle for nursing, but don’t swaddle for sleep” is the message, said Dr. Hagan.

For breast-fed babies, iron supplementation should begin at the 4-month visit. The notion is to prevent progression from iron deficiency to frank anemia, said Dr. Hagan. “We know that we screen for iron deficiency anemia … but we also know that before you’re iron deficient anemic, you’re iron deficient,” he said, and iron’s also critical to brain development. For convenience, switching from vitamin D alone to a multivitamin drop with iron at 4 months is a practical choice.

New dental health recommendations bring prevention to the pediatrician’s office. “Fluoride varnish? Do it!” said Dr. Hagan. Although the USPSTF made a 2014 grade B recommendation that primary care clinicians apply fluoride varnish to primary teeth as soon as they erupt, “It’s new to the Bright Futures periodicity schedule,” he said; parents can be assured that fluoride varnish does not cause fluorosis.

The good news for clinicians, he noted. “Once it hits the periodicity schedule, now, it’s a billable service that must be paid” under Affordable Care Act regulations, said Dr. Hagan. “Don’t let your insurer say, ‘That’s part of what you’re already being paid for.’ ” He recommends avoiding the pressure to bundle this important service. Use the discrete CPT code 99188, “Application of a fluoride varnish by a physician or other qualified health care professional.”

Although Bright Futures has updated recommendations for dyslipidemia blood screening, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to back lipid screening for those younger than 20 years of age, citing an inability to assess the balance of benefits and harms for universal, rather than risk-based, screening. However, said Dr. Hagan, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) were looking at this issue at about the same time, and they “did a really good job of showing their work,” to show that if family history alone guided screening in the pediatric population, it “just wasn’t getting done.” And AAP and NHLBI did demonstrate evidence sufficient to support this recommendation.

Accordingly, Bright Futures recommends one screening between ages 9 and 11 years and an additional screening between ages 17 and 21. These windows are designed to bracket puberty, said Dr. Hagan, because values can be skewed during that period. “It’s billable, it’s not bundle-able, and I’d recommend that you do it,” he said.

Developmental surveillance and screening

What’s new with developmental surveillance and screening? “Well, we could argue that the milestones are something to think about, because the milestones are the cornerstone of developmental surveillance,” said Dr. Hagan. “You’re in the room with the child. You’re trained, you’re experienced, you’re smart, your gestalt tells you if their development is good or bad.”

As important as surveillance is, though, he said, it is “nowhere near as important as screening.” Surveillance happens at every well-child visit, but there’s no substitute for formal developmental screening. For the Fourth Edition guidance and toolkit, gross motor milestones have been adjusted to reflect what’s really being seen as more parents adopt the Back to Sleep recommendations as well.

A standardized developmental screening tool is used at the 9-, 18-, and 30-month visits, and when parents or caregivers express concern about development. Autism-specific screening happens at 18 and 24 months.

“Remember this, if you remember nothing else: If the screening is positive, and you believe there’s a problem, you’re going to refer,” not just to the appropriate specialist but also for early intervention services, so time isn’t lost as the child is waiting for further evaluation and a formal diagnosis, said Dr. Hagan. This coordinated effort appropriately places the responsibility for early identification of developmental delays and disorders at the doorstep of the child’s medical home.

The federally-coordinated Birth to 5: Watch Me Thrive! effort has aggregated research-based screening tools, users’ guides targeted at a variety of audiences, and resources to help caregivers, said Dr. Hagan.

Four commonly-used tools to consider using during the visit are the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, the Child Health and Development Interactive System, and the Survey of Wellbeing of Young Children. Of these, said Dr. Hagan, the latter is the only tool that’s in the public domain. However, he said, they are “all really good.”

Consider having parents fill out screening questionnaires in the waiting room before the visit, said Dr. Hagan. “I always tell my colleagues, ‘Have them start the visit without you, if you want to get it done in 18 minutes.’ ”

Two questionnaires per visit are available in the Bright Futures toolkit. One questionnaire asks developmental surveillance and risk assessment questions for selective screening. The second questionnaire asks prescreening questions to help with the anticipatory guidance part of the visit, he said. Having families do these ahead of time, said Dr. Hagan, “allows you to become more focused.”

Paying attention to practicalities can make all this go more smoothly, and maximize reimbursement as well. In his own practice, Dr. Hagan said, screening tools and questionnaires are integrated into the EHR system, so that appropriate paperwork prints automatically ahead of the visit.

It’s also worth reviewing billing practices to make sure that CPT code 96110 is used when administering screening with a standardized instrument and completing scoring and documentation. According to the Bright Futures periodicity schedule, this may be done at the 9-, 18-, and 30-month visits for developmental screening, as well as at 18 and 24 months for autism-specific screening.

Promoting lifelong health

Since the initial Bright Futures guidelines were published in the late 1990s, said Dr. Hagan, the focus has always been on seeing the child as part of the family, who, in turn, are part of the community, forming a framework that addresses the social components of child health. “If you’re not looking at the whole picture, you’re not promoting health,” he said. “It’s no big surprise that we now have a specific, called-out focus on promoting lifelong health.”

In the Fourth Edition, the theme of promoting lifelong health for families and communities is woven throughout, with social determinants of health being a specific visit priority. For example, questions about food insecurity have been drawn from the published literature and are included. Also, said Dr. Hagan, there’s specific anticipatory guidance content that’s clearly marked as addressing social determinants of health.

The fundamental importance of socioeconomic status as a social determinant of health was brought home by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Commission to Build a Healthier America, which demonstrated that, “Your ZIP code is more important to your health than your genetic code,” said Dr. Hagan. “So your work in health supervision is important, and you have been leaders in this effort.”

Research guides Bright Futures updates

The fourth edition of Bright Futures builds on health promotion themes to support the mental and physical health of children and adolescents, and has a robust framework of evidence underpinning the guidelines, said Dr. Hagan.

The goal is for clinicians to “use evidence to decide upon content of their own health supervision visits,” he explained.

The chapter of the Bright Futures guidelines that addresses the evidence and rationale for the guidelines has been expanded to better answer two questions, said Dr. Hagan: “What evidence grounds our recommendations?” and “What rationale did we use when evidence was insufficient or lacking?”

When possible, the editors of the guidelines used evidence-based sources such as recommendations from the USPSTF, the Centers for Disease Control Community Guide, and the Cochrane Collaboration.

There were many more evidence-based recommendations available to those working on the 4th edition than there had been when writing the previous edition, when, said Dr. Hagan, the USPSTF had exactly two recommendations for those under the age of 21 years. The current expanded number of USPSTF pediatric recommendations was due in part to the attention the AAP was able to bring regarding the need for evidence-based recommendations in pediatrics, he said.

When guidelines were not available, the editors also turned to high quality studies from peer reviewed publications. When such high quality evidence was lacking in a particular area, the guidelines make clear what rationale was used to formulate a given recommendation, and that some recommendations should be interpreted with a degree of caution.

And, said Dr. Hagan, even science-based guidelines will change as more data accumulates. “Don’t forget about peanuts!” he said. “It was really logical 15 years ago when we said don’t give peanut products until 1 year of age. And about 2 years ago, we found out that it really didn’t work.”

Although there are specific updates to clinical content, there also were changes made in broader strokes throughout the 4th edition. One of these shifts embeds social determinants of health in many visits. This adjustment acknowledges the growing body of knowledge that “strengths and protective factors make a difference, and risk factors make a difference” in pediatric outcomes.

A greater focus on lifelong physical and mental health is included under the general rubric of promoting lifelong health for families and communities. More emphasis is placed on promoting health for children and youth who have special health care needs as well.

Nuts-and-bolts changes in the updated 4th edition include updates for milestones of development and accompanying developmental surveillance questions, new clinical content and guidance for implementation that have been added based on strong evidence, and a variety of updates for adolescent screenings in particular.

The full 4th edition Bright Futures toolkit will be available for use in 2018.

Dr. Hagan was a coeditor of the Fourth Edition of Bright Futures.

*This article was updated on December 21, 2017

CHICAGO – Bracing his audience for a whirlwind tour of the many updates to the fourth edition of Bright Futures, Joseph F. Hagan Jr., MD, said that it’s still completely possible to fit Bright Futures visits into a clinic day.

“I practice primary care pediatrics,” said Dr. Hagan, a pediatrician in private practice and clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Vermont, both in Burlington. “I said to my Bright Futures colleagues, if I didn’t think I could do this in 18 minutes, I wouldn’t ask you to do it.”

The Bright Futures framework, described by Dr. Hagan as the health prevention and disease prevention component of the medical home for children and youth, emerges in the Fourth Edition with a significant evidence-based refresher. The changes and updates are built within the existing framework and encompass surveillance and screening recommendations as well as anticipatory guidance. All content, including family handouts, has been updated, said Dr. Hagan, a coeditor of the Fourth Edition of Bright Futures. He spoke at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

New clinical content

“What’s new? Maternal depression screening is new,” said Dr. Hagan, noting that the recommendation has long been under discussion. Now, supported by a 2016 United States Preventative Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation that carries a grade B level of evidence, all mothers should be screened for depression at the 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-month Bright Futures visits.

However, he said, know your local regulations. “State mandates to do more might overrule this.” And conversely, “Just because we’re doing it universally until 6 months doesn’t mean you couldn’t selectively screen later if you have concerns.”

Safe sleep is another area with new clinical focus, he said. The new recommendation for the child to sleep in the parent’s room for “at least 6 months” draws on data from European studies showing lower mortality for children who share a room with parents during this period.

Clinicians should continue to recommend that parents not sleep with their infants in couches, chairs, or beds. As before, parents should be told not to have loose blankets, stuffed toys, or crib bumpers in their babies’ cribs. Another key message, said Dr. Hagan, is that “There is no such thing as safe ‘breast-sleeping.’ ”

Parents should be reminded not to swaddle at nap – or bedtime. The risk is that even a 2-month-old infant may be capable of wriggling over from back to front, and a swaddled infant whose hands are trapped may not be able to move to protect her airway once prone. “Swaddle for comfort, swaddle for crying, swaddle for nursing, but don’t swaddle for sleep” is the message, said Dr. Hagan.

For breast-fed babies, iron supplementation should begin at the 4-month visit. The notion is to prevent progression from iron deficiency to frank anemia, said Dr. Hagan. “We know that we screen for iron deficiency anemia … but we also know that before you’re iron deficient anemic, you’re iron deficient,” he said, and iron’s also critical to brain development. For convenience, switching from vitamin D alone to a multivitamin drop with iron at 4 months is a practical choice.

New dental health recommendations bring prevention to the pediatrician’s office. “Fluoride varnish? Do it!” said Dr. Hagan. Although the USPSTF made a 2014 grade B recommendation that primary care clinicians apply fluoride varnish to primary teeth as soon as they erupt, “It’s new to the Bright Futures periodicity schedule,” he said; parents can be assured that fluoride varnish does not cause fluorosis.

The good news for clinicians, he noted. “Once it hits the periodicity schedule, now, it’s a billable service that must be paid” under Affordable Care Act regulations, said Dr. Hagan. “Don’t let your insurer say, ‘That’s part of what you’re already being paid for.’ ” He recommends avoiding the pressure to bundle this important service. Use the discrete CPT code 99188, “Application of a fluoride varnish by a physician or other qualified health care professional.”

Although Bright Futures has updated recommendations for dyslipidemia blood screening, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to back lipid screening for those younger than 20 years of age, citing an inability to assess the balance of benefits and harms for universal, rather than risk-based, screening. However, said Dr. Hagan, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) were looking at this issue at about the same time, and they “did a really good job of showing their work,” to show that if family history alone guided screening in the pediatric population, it “just wasn’t getting done.” And AAP and NHLBI did demonstrate evidence sufficient to support this recommendation.

Accordingly, Bright Futures recommends one screening between ages 9 and 11 years and an additional screening between ages 17 and 21. These windows are designed to bracket puberty, said Dr. Hagan, because values can be skewed during that period. “It’s billable, it’s not bundle-able, and I’d recommend that you do it,” he said.

Developmental surveillance and screening

What’s new with developmental surveillance and screening? “Well, we could argue that the milestones are something to think about, because the milestones are the cornerstone of developmental surveillance,” said Dr. Hagan. “You’re in the room with the child. You’re trained, you’re experienced, you’re smart, your gestalt tells you if their development is good or bad.”

As important as surveillance is, though, he said, it is “nowhere near as important as screening.” Surveillance happens at every well-child visit, but there’s no substitute for formal developmental screening. For the Fourth Edition guidance and toolkit, gross motor milestones have been adjusted to reflect what’s really being seen as more parents adopt the Back to Sleep recommendations as well.

A standardized developmental screening tool is used at the 9-, 18-, and 30-month visits, and when parents or caregivers express concern about development. Autism-specific screening happens at 18 and 24 months.

“Remember this, if you remember nothing else: If the screening is positive, and you believe there’s a problem, you’re going to refer,” not just to the appropriate specialist but also for early intervention services, so time isn’t lost as the child is waiting for further evaluation and a formal diagnosis, said Dr. Hagan. This coordinated effort appropriately places the responsibility for early identification of developmental delays and disorders at the doorstep of the child’s medical home.

The federally-coordinated Birth to 5: Watch Me Thrive! effort has aggregated research-based screening tools, users’ guides targeted at a variety of audiences, and resources to help caregivers, said Dr. Hagan.

Four commonly-used tools to consider using during the visit are the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, the Child Health and Development Interactive System, and the Survey of Wellbeing of Young Children. Of these, said Dr. Hagan, the latter is the only tool that’s in the public domain. However, he said, they are “all really good.”

Consider having parents fill out screening questionnaires in the waiting room before the visit, said Dr. Hagan. “I always tell my colleagues, ‘Have them start the visit without you, if you want to get it done in 18 minutes.’ ”

Two questionnaires per visit are available in the Bright Futures toolkit. One questionnaire asks developmental surveillance and risk assessment questions for selective screening. The second questionnaire asks prescreening questions to help with the anticipatory guidance part of the visit, he said. Having families do these ahead of time, said Dr. Hagan, “allows you to become more focused.”

Paying attention to practicalities can make all this go more smoothly, and maximize reimbursement as well. In his own practice, Dr. Hagan said, screening tools and questionnaires are integrated into the EHR system, so that appropriate paperwork prints automatically ahead of the visit.

It’s also worth reviewing billing practices to make sure that CPT code 96110 is used when administering screening with a standardized instrument and completing scoring and documentation. According to the Bright Futures periodicity schedule, this may be done at the 9-, 18-, and 30-month visits for developmental screening, as well as at 18 and 24 months for autism-specific screening.

Promoting lifelong health