User login

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Expert review on atrophic gastritis

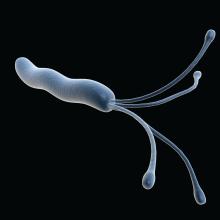

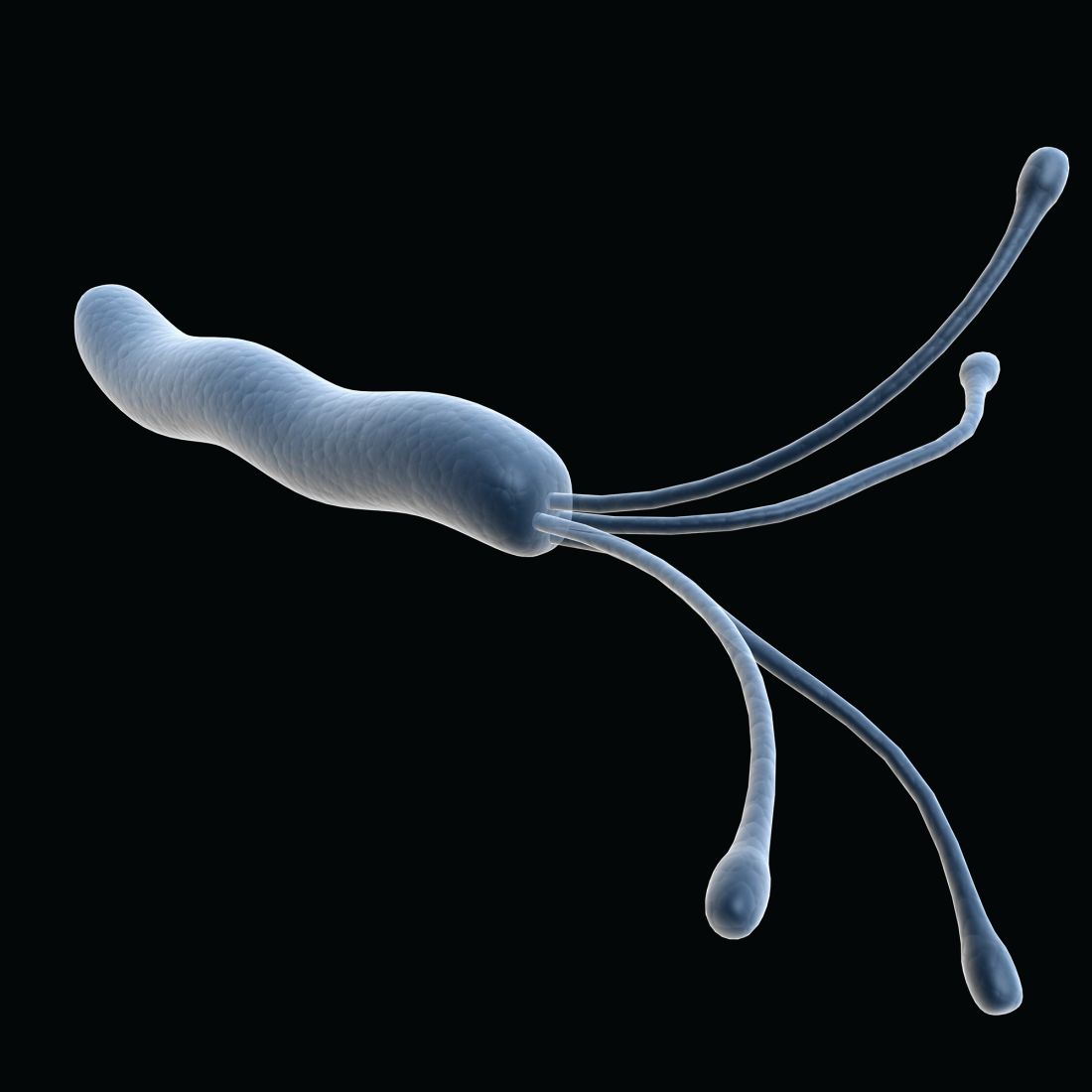

A new clinical practice update expert review for the diagnosis and management of atrophic gastritis (AG) from the American Gastroenterological Association focuses on cases linked to Helicobacter pylori infection or autoimmunity.

This update addresses a sparsity of guidelines for AG in the United States and should be seen as complementary to the AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia, according to the authors led by Shailja C. Shah, MD, MPH, of the gastroenterology section at Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego.

The 2020 guidelines didn’t specifically discuss diagnosis and management of AG; however, a diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia based on gastric histopathology indicates the presence AG since metaplasia occurs in atrophic mucosa. Nevertheless, AG often goes unmentioned in histopathology reports. Such omissions are important because AG is an important stage in the potential development of gastric cancer.

AG is believed to result from genetic and environmental factors. The two primary triggers for the condition are H. pylori infection (HpAG) and autoimmunity (AIG). The condition results from chronic inflammation and replacement of normal gastric glandular structures with connective tissue or nonnative epithelium. It can proceed to other precancerous conditions, including gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. An estimated 15% of the U.S. population has AG, according to the authors, although this prevalence could be higher in populations with higher rates of H. pylori infection. AIG is rare, occurring in 0.5%-2% of the U.S. population.

Among individuals with AG, 0.1%-0.3% per year go on to develop gastric adenocarcinoma, though additional factors could heighten this risk. Furthermore, 0.4%-0.7% per year go on develop type 1 neuroendocrine tumors.

HpAG and AIG have different patterns of mucosal involvement. During diagnosis, the authors advised careful mucosal visualization with air insufflation and mucosal cleansing. High-definition white-light endoscopy is more sensitive than traditional WLE in the identification of premalignant mucosal changes.

AG diagnosis should be confirmed by histopathology. The updated Sydney protocol should be used to obtain biopsies, and serum pepsinogens can be used to identify extensive atrophy, though this testing is not generally available in the United States for clinical use. When histology results are suggestive of AIG, the presence of parietal cell antibodies and intrinsic factor antibodies can contribute to a diagnosis, although the former can be prone to false positives because of H. pylori infection, and the latter has low sensitivity.

Patients identified with AG should be tested for H. pylori and treated for infection, followed by nonserologic testing to confirm treatment success. If H. pylori is present, successful eradication may allow for reversal of AG to normal gastric mucosa; however, patients may have irreversible changes. This could leave them at elevated risk of further progression, though elimination of H. pylori does appear to blunt that risk somewhat.

Neoplastic complications from AG are rare, and the benefits of surveillance among those with AG have not been demonstrated in prospective trials. Observational trials show that severe AG is associated with greater risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, and other factors, such as comorbidities and patient values and priorities, should inform decision-making. When called for, providers should consider surveillance endoscopies every 3 years, though the authors noted that the optimal surveillance interval is unknown. Factors such as the quality of the original endoscopy, family history of gastric cancer, and a history of immigration from regions with high rates of H. pylori infection may impact decisions on surveillance intervals.

AG can lead to iron or vitamin B12 deficiency, so patients with AG, especially those with corpus-predominant AG, should be evaluated for both. AG should also be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with either deficiency.

A diagnosis of AIG should be accompanied by screening for autoimmune thyroid disease, and type 1 diabetes or Addison’s disease may also be indicated if clinical presentation is consistent.

Because AG is commonly underdiagnosed, the authors advise that gastroenterologists and pathologists should improve coordination to maximize diagnosis of the condition, and they call for comparative clinical trials to improve risk stratification algorithms and surveillance strategies.

The authors disclose no relevant conflicts of interest.

A new clinical practice update expert review for the diagnosis and management of atrophic gastritis (AG) from the American Gastroenterological Association focuses on cases linked to Helicobacter pylori infection or autoimmunity.

This update addresses a sparsity of guidelines for AG in the United States and should be seen as complementary to the AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia, according to the authors led by Shailja C. Shah, MD, MPH, of the gastroenterology section at Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego.

The 2020 guidelines didn’t specifically discuss diagnosis and management of AG; however, a diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia based on gastric histopathology indicates the presence AG since metaplasia occurs in atrophic mucosa. Nevertheless, AG often goes unmentioned in histopathology reports. Such omissions are important because AG is an important stage in the potential development of gastric cancer.

AG is believed to result from genetic and environmental factors. The two primary triggers for the condition are H. pylori infection (HpAG) and autoimmunity (AIG). The condition results from chronic inflammation and replacement of normal gastric glandular structures with connective tissue or nonnative epithelium. It can proceed to other precancerous conditions, including gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. An estimated 15% of the U.S. population has AG, according to the authors, although this prevalence could be higher in populations with higher rates of H. pylori infection. AIG is rare, occurring in 0.5%-2% of the U.S. population.

Among individuals with AG, 0.1%-0.3% per year go on to develop gastric adenocarcinoma, though additional factors could heighten this risk. Furthermore, 0.4%-0.7% per year go on develop type 1 neuroendocrine tumors.

HpAG and AIG have different patterns of mucosal involvement. During diagnosis, the authors advised careful mucosal visualization with air insufflation and mucosal cleansing. High-definition white-light endoscopy is more sensitive than traditional WLE in the identification of premalignant mucosal changes.

AG diagnosis should be confirmed by histopathology. The updated Sydney protocol should be used to obtain biopsies, and serum pepsinogens can be used to identify extensive atrophy, though this testing is not generally available in the United States for clinical use. When histology results are suggestive of AIG, the presence of parietal cell antibodies and intrinsic factor antibodies can contribute to a diagnosis, although the former can be prone to false positives because of H. pylori infection, and the latter has low sensitivity.

Patients identified with AG should be tested for H. pylori and treated for infection, followed by nonserologic testing to confirm treatment success. If H. pylori is present, successful eradication may allow for reversal of AG to normal gastric mucosa; however, patients may have irreversible changes. This could leave them at elevated risk of further progression, though elimination of H. pylori does appear to blunt that risk somewhat.

Neoplastic complications from AG are rare, and the benefits of surveillance among those with AG have not been demonstrated in prospective trials. Observational trials show that severe AG is associated with greater risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, and other factors, such as comorbidities and patient values and priorities, should inform decision-making. When called for, providers should consider surveillance endoscopies every 3 years, though the authors noted that the optimal surveillance interval is unknown. Factors such as the quality of the original endoscopy, family history of gastric cancer, and a history of immigration from regions with high rates of H. pylori infection may impact decisions on surveillance intervals.

AG can lead to iron or vitamin B12 deficiency, so patients with AG, especially those with corpus-predominant AG, should be evaluated for both. AG should also be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with either deficiency.

A diagnosis of AIG should be accompanied by screening for autoimmune thyroid disease, and type 1 diabetes or Addison’s disease may also be indicated if clinical presentation is consistent.

Because AG is commonly underdiagnosed, the authors advise that gastroenterologists and pathologists should improve coordination to maximize diagnosis of the condition, and they call for comparative clinical trials to improve risk stratification algorithms and surveillance strategies.

The authors disclose no relevant conflicts of interest.

A new clinical practice update expert review for the diagnosis and management of atrophic gastritis (AG) from the American Gastroenterological Association focuses on cases linked to Helicobacter pylori infection or autoimmunity.

This update addresses a sparsity of guidelines for AG in the United States and should be seen as complementary to the AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia, according to the authors led by Shailja C. Shah, MD, MPH, of the gastroenterology section at Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego.

The 2020 guidelines didn’t specifically discuss diagnosis and management of AG; however, a diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia based on gastric histopathology indicates the presence AG since metaplasia occurs in atrophic mucosa. Nevertheless, AG often goes unmentioned in histopathology reports. Such omissions are important because AG is an important stage in the potential development of gastric cancer.

AG is believed to result from genetic and environmental factors. The two primary triggers for the condition are H. pylori infection (HpAG) and autoimmunity (AIG). The condition results from chronic inflammation and replacement of normal gastric glandular structures with connective tissue or nonnative epithelium. It can proceed to other precancerous conditions, including gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. An estimated 15% of the U.S. population has AG, according to the authors, although this prevalence could be higher in populations with higher rates of H. pylori infection. AIG is rare, occurring in 0.5%-2% of the U.S. population.

Among individuals with AG, 0.1%-0.3% per year go on to develop gastric adenocarcinoma, though additional factors could heighten this risk. Furthermore, 0.4%-0.7% per year go on develop type 1 neuroendocrine tumors.

HpAG and AIG have different patterns of mucosal involvement. During diagnosis, the authors advised careful mucosal visualization with air insufflation and mucosal cleansing. High-definition white-light endoscopy is more sensitive than traditional WLE in the identification of premalignant mucosal changes.

AG diagnosis should be confirmed by histopathology. The updated Sydney protocol should be used to obtain biopsies, and serum pepsinogens can be used to identify extensive atrophy, though this testing is not generally available in the United States for clinical use. When histology results are suggestive of AIG, the presence of parietal cell antibodies and intrinsic factor antibodies can contribute to a diagnosis, although the former can be prone to false positives because of H. pylori infection, and the latter has low sensitivity.

Patients identified with AG should be tested for H. pylori and treated for infection, followed by nonserologic testing to confirm treatment success. If H. pylori is present, successful eradication may allow for reversal of AG to normal gastric mucosa; however, patients may have irreversible changes. This could leave them at elevated risk of further progression, though elimination of H. pylori does appear to blunt that risk somewhat.

Neoplastic complications from AG are rare, and the benefits of surveillance among those with AG have not been demonstrated in prospective trials. Observational trials show that severe AG is associated with greater risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, and other factors, such as comorbidities and patient values and priorities, should inform decision-making. When called for, providers should consider surveillance endoscopies every 3 years, though the authors noted that the optimal surveillance interval is unknown. Factors such as the quality of the original endoscopy, family history of gastric cancer, and a history of immigration from regions with high rates of H. pylori infection may impact decisions on surveillance intervals.

AG can lead to iron or vitamin B12 deficiency, so patients with AG, especially those with corpus-predominant AG, should be evaluated for both. AG should also be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with either deficiency.

A diagnosis of AIG should be accompanied by screening for autoimmune thyroid disease, and type 1 diabetes or Addison’s disease may also be indicated if clinical presentation is consistent.

Because AG is commonly underdiagnosed, the authors advise that gastroenterologists and pathologists should improve coordination to maximize diagnosis of the condition, and they call for comparative clinical trials to improve risk stratification algorithms and surveillance strategies.

The authors disclose no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

The Barcelona baseline risk score may predict long-term MS course

The high-risk group had the shortest time to progression to an Expanded Disability Status Score (EDSS) of 3.0, and were also more likely to progress by MRI and quality of life measures.

The ranking is based on sex, age at the first clinically isolated syndrome, CIS topography, the number of T2 lesions, and the presence of infratentorial and spinal cord lesions, contrast-enhancing lesions, and oligoclonal bands.

“What we wanted to do is merge all of the different prognostic variables for one single patient into one single score,” said Mar Tintoré, MD, PhD, in an interview. Dr. Tintoré is a professor of neurology at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona and a senior consultant at the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia (Cemcat). Dr. Tintoré presented the results of the study at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

The three groups had different outcomes in MRI, clinical factors, and MRI scans, and quality of life outcomes over the course of their disease. “So this is a confirmation that this classification at baseline is really meaningful,” Dr. Tintoré said in an interview.

She attributed the success of the model to its reliance on multiple factors, but it is also designed to be simple to use. “We have been trying to use it with simple factors, [information] that you always have, like age, sex, gender, number of lesions, and topography of the region. Everybody has this information at their desk.”

Proof of concept

The study validates the approach that neurologists already utilize, according to Patricia Coyle, MD, who moderated the session. “I think the prospective study is a really unique and powerful concept,” said Dr. Coyle, who is a professor of neurology, vice chair of neurology, and director of the Stony Brook (N.Y.) Comprehensive Care Center.

The new study “kind of confirmed their concept of the initial rating, judging long-term disability progression measures in subsets. They also looked at brain atrophy, they looked at gray-matter atrophy, and that also traveled with these three different groups of severity. So it kind of gives value to looking at prognostic indicators at a first attack,” said Dr. Coyle.

The results also validate the Barcelona group’s heavy emphasis on MRI, which Dr. Coyle pointed out is common practice. “If the brain MRI looks very bad, if there are a lot of spinal cord lesions, then that’s somebody we’re much more worried about.”

Once the model is confirmed in other cohorts, the researchers plan to release the model as a generally available algorithm that clinicians could use to help manage patients. Dr. Tintoré pointed out the debate over when to begin a patient on high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies. That choice depends on a lot of factors, including patient choice, safety, and comorbidities. “But knowing that your patient is at risk of having a bad prognosis is something that is helpful” in that decision-making process, she said.

Predicting time to EDSS 3.0

The researchers used the Barcelona CIS cohort to build a Weibull survival regression in order to estimate the median time to EDSS 3.0. The model produced three categories with widely divergent predicted times from CIS to EDSS 3.0: low risk, medium risk, and high risk.

In the current report, the researchers compared the model to a “360 degree” measure of measures in 1,308 patients, including clinical milestones (McDonald 2017 MS, confirmed secondary progressive MS, progression independent of relapse activity [PIRA], EDSS disability, number of T2 MRI lesions and brain atrophy, and Patient Reported Outcomes for MS [walking speed, manual dexterity, processing speed, and contrast sensitivity]).

At 30 years after CIS, the risk of reaching EDSS 3.0 was higher in the medium risk (hazard ratio, 3.0 versus low risk) and in the high risk group (HR, 8.3 versus low risk). At 10 years, the low risk group had a 40% risk of fulfilling McDonald 2017 criteria, versus 89% in the intermediate group, and 98% in the high risk group. A similar relationship was seen for SPMS (1%, 8%, 16%) and PIRA (17%, 26%, 35%).

At 10 years, the estimated accumulated T2 lesions was 7 in the low-risk group (95% CI, 5-9), 15 in the medium-risk group (95% CI, 12-17), and 21 in the high-risk group (95% CI, 15-27).

Compared with the low- and medium-risk groups, the high-risk group had lower brain parenchymal fraction and gray-matter fraction at 5 years. They also experienced higher stigma, had worse perception of upper and lower limb function as measured by Neuro QoL, and had worse cognitive performance.

Dr. Tintoré has received compensation for consulting services and speaking honoraria from Aimirall, Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen-Idec, Genzyme, Janssen, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Viela Bio. Dr. Coyle has no relevant disclosures.

The high-risk group had the shortest time to progression to an Expanded Disability Status Score (EDSS) of 3.0, and were also more likely to progress by MRI and quality of life measures.

The ranking is based on sex, age at the first clinically isolated syndrome, CIS topography, the number of T2 lesions, and the presence of infratentorial and spinal cord lesions, contrast-enhancing lesions, and oligoclonal bands.

“What we wanted to do is merge all of the different prognostic variables for one single patient into one single score,” said Mar Tintoré, MD, PhD, in an interview. Dr. Tintoré is a professor of neurology at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona and a senior consultant at the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia (Cemcat). Dr. Tintoré presented the results of the study at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

The three groups had different outcomes in MRI, clinical factors, and MRI scans, and quality of life outcomes over the course of their disease. “So this is a confirmation that this classification at baseline is really meaningful,” Dr. Tintoré said in an interview.

She attributed the success of the model to its reliance on multiple factors, but it is also designed to be simple to use. “We have been trying to use it with simple factors, [information] that you always have, like age, sex, gender, number of lesions, and topography of the region. Everybody has this information at their desk.”

Proof of concept

The study validates the approach that neurologists already utilize, according to Patricia Coyle, MD, who moderated the session. “I think the prospective study is a really unique and powerful concept,” said Dr. Coyle, who is a professor of neurology, vice chair of neurology, and director of the Stony Brook (N.Y.) Comprehensive Care Center.

The new study “kind of confirmed their concept of the initial rating, judging long-term disability progression measures in subsets. They also looked at brain atrophy, they looked at gray-matter atrophy, and that also traveled with these three different groups of severity. So it kind of gives value to looking at prognostic indicators at a first attack,” said Dr. Coyle.

The results also validate the Barcelona group’s heavy emphasis on MRI, which Dr. Coyle pointed out is common practice. “If the brain MRI looks very bad, if there are a lot of spinal cord lesions, then that’s somebody we’re much more worried about.”

Once the model is confirmed in other cohorts, the researchers plan to release the model as a generally available algorithm that clinicians could use to help manage patients. Dr. Tintoré pointed out the debate over when to begin a patient on high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies. That choice depends on a lot of factors, including patient choice, safety, and comorbidities. “But knowing that your patient is at risk of having a bad prognosis is something that is helpful” in that decision-making process, she said.

Predicting time to EDSS 3.0

The researchers used the Barcelona CIS cohort to build a Weibull survival regression in order to estimate the median time to EDSS 3.0. The model produced three categories with widely divergent predicted times from CIS to EDSS 3.0: low risk, medium risk, and high risk.

In the current report, the researchers compared the model to a “360 degree” measure of measures in 1,308 patients, including clinical milestones (McDonald 2017 MS, confirmed secondary progressive MS, progression independent of relapse activity [PIRA], EDSS disability, number of T2 MRI lesions and brain atrophy, and Patient Reported Outcomes for MS [walking speed, manual dexterity, processing speed, and contrast sensitivity]).

At 30 years after CIS, the risk of reaching EDSS 3.0 was higher in the medium risk (hazard ratio, 3.0 versus low risk) and in the high risk group (HR, 8.3 versus low risk). At 10 years, the low risk group had a 40% risk of fulfilling McDonald 2017 criteria, versus 89% in the intermediate group, and 98% in the high risk group. A similar relationship was seen for SPMS (1%, 8%, 16%) and PIRA (17%, 26%, 35%).

At 10 years, the estimated accumulated T2 lesions was 7 in the low-risk group (95% CI, 5-9), 15 in the medium-risk group (95% CI, 12-17), and 21 in the high-risk group (95% CI, 15-27).

Compared with the low- and medium-risk groups, the high-risk group had lower brain parenchymal fraction and gray-matter fraction at 5 years. They also experienced higher stigma, had worse perception of upper and lower limb function as measured by Neuro QoL, and had worse cognitive performance.

Dr. Tintoré has received compensation for consulting services and speaking honoraria from Aimirall, Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen-Idec, Genzyme, Janssen, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Viela Bio. Dr. Coyle has no relevant disclosures.

The high-risk group had the shortest time to progression to an Expanded Disability Status Score (EDSS) of 3.0, and were also more likely to progress by MRI and quality of life measures.

The ranking is based on sex, age at the first clinically isolated syndrome, CIS topography, the number of T2 lesions, and the presence of infratentorial and spinal cord lesions, contrast-enhancing lesions, and oligoclonal bands.

“What we wanted to do is merge all of the different prognostic variables for one single patient into one single score,” said Mar Tintoré, MD, PhD, in an interview. Dr. Tintoré is a professor of neurology at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona and a senior consultant at the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia (Cemcat). Dr. Tintoré presented the results of the study at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

The three groups had different outcomes in MRI, clinical factors, and MRI scans, and quality of life outcomes over the course of their disease. “So this is a confirmation that this classification at baseline is really meaningful,” Dr. Tintoré said in an interview.

She attributed the success of the model to its reliance on multiple factors, but it is also designed to be simple to use. “We have been trying to use it with simple factors, [information] that you always have, like age, sex, gender, number of lesions, and topography of the region. Everybody has this information at their desk.”

Proof of concept

The study validates the approach that neurologists already utilize, according to Patricia Coyle, MD, who moderated the session. “I think the prospective study is a really unique and powerful concept,” said Dr. Coyle, who is a professor of neurology, vice chair of neurology, and director of the Stony Brook (N.Y.) Comprehensive Care Center.

The new study “kind of confirmed their concept of the initial rating, judging long-term disability progression measures in subsets. They also looked at brain atrophy, they looked at gray-matter atrophy, and that also traveled with these three different groups of severity. So it kind of gives value to looking at prognostic indicators at a first attack,” said Dr. Coyle.

The results also validate the Barcelona group’s heavy emphasis on MRI, which Dr. Coyle pointed out is common practice. “If the brain MRI looks very bad, if there are a lot of spinal cord lesions, then that’s somebody we’re much more worried about.”

Once the model is confirmed in other cohorts, the researchers plan to release the model as a generally available algorithm that clinicians could use to help manage patients. Dr. Tintoré pointed out the debate over when to begin a patient on high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies. That choice depends on a lot of factors, including patient choice, safety, and comorbidities. “But knowing that your patient is at risk of having a bad prognosis is something that is helpful” in that decision-making process, she said.

Predicting time to EDSS 3.0

The researchers used the Barcelona CIS cohort to build a Weibull survival regression in order to estimate the median time to EDSS 3.0. The model produced three categories with widely divergent predicted times from CIS to EDSS 3.0: low risk, medium risk, and high risk.

In the current report, the researchers compared the model to a “360 degree” measure of measures in 1,308 patients, including clinical milestones (McDonald 2017 MS, confirmed secondary progressive MS, progression independent of relapse activity [PIRA], EDSS disability, number of T2 MRI lesions and brain atrophy, and Patient Reported Outcomes for MS [walking speed, manual dexterity, processing speed, and contrast sensitivity]).

At 30 years after CIS, the risk of reaching EDSS 3.0 was higher in the medium risk (hazard ratio, 3.0 versus low risk) and in the high risk group (HR, 8.3 versus low risk). At 10 years, the low risk group had a 40% risk of fulfilling McDonald 2017 criteria, versus 89% in the intermediate group, and 98% in the high risk group. A similar relationship was seen for SPMS (1%, 8%, 16%) and PIRA (17%, 26%, 35%).

At 10 years, the estimated accumulated T2 lesions was 7 in the low-risk group (95% CI, 5-9), 15 in the medium-risk group (95% CI, 12-17), and 21 in the high-risk group (95% CI, 15-27).

Compared with the low- and medium-risk groups, the high-risk group had lower brain parenchymal fraction and gray-matter fraction at 5 years. They also experienced higher stigma, had worse perception of upper and lower limb function as measured by Neuro QoL, and had worse cognitive performance.

Dr. Tintoré has received compensation for consulting services and speaking honoraria from Aimirall, Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen-Idec, Genzyme, Janssen, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Viela Bio. Dr. Coyle has no relevant disclosures.

FROM ECTRIMS 2021

In MS, baseline cortical lesions predict cognitive decline

, according to findings from a new analysis. The findings had good accuracy, and could help clinicians monitor and treat cognitive impairment as it develops, according to Stefano Ziccardi, PhD, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Verona in Italy.

“The number of cortical lesions at MS diagnosis accurately discriminates between the presence or the absence of cognitive impairment after diagnosis of MS, and this should be considered a predictive marker of long-term cognitive impairment in these patients. Early cortical lesion evaluation should be conducted in each MS patient to anticipate the manifestation of cognitive problems to improve the monitoring of cognitive abilities, improve the diagnosis of cognitive impairment, enable prompt intervention as necessary,” said Dr. Ziccardi at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

Cortical lesions are highly prevalent in MS, perhaps more so than white matter lesions, said Dr. Ziccardi. They are associated with clinical disability and lead to disease progression. “However, prognostic data about the role of early cortical lesions with reference to long-term cognitive impairment are still missing,” said Dr. Ziccardi.

That’s important because cognitive impairment is very common in MS, affecting between one-third and two-thirds of patients. It may appear early in the disease course and worsen over time, and it predicts worse clinical and neurological progression. And it presents a clinical challenge. “Clinicians struggle to predict the evolution of cognitive abilities over time,” said Dr. Ziccardi.

The findings drew praise from Iris-Katharina Penner, PhD, who comoderated the session. “I think the important point … is that the predictive value of cortical lesions is very high, because it indicates finally that we probably have a patient at risk for developing cognitive impairment in the future,” said Dr. Penner, who is a neuropsychologist and cognitive neuroscientist at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Clinicians often don’t pay enough attention to cognition and the complexities of MS, said Mark Gudesblatt, MD, who was asked to comment. “It’s just adding layers of complexity. We’re peeling back the onion and you realize it’s a really complicated disease. It’s not just white matter plaques, gray matter plaques, disconnection syndrome, wires cut, atrophy, ongoing inflammation, immune deficiency. All these diseases are fascinating. And we think we’re experts. But the fact is, we have much to learn,” said Dr. Gudesblatt, who is medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center at South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, New York.

The researchers analyzed data from 170 patients with MS who had a disease duration of approximately 20 years. Among the study cohort 62 patients were female, and the mean duration of disease was 19.2 years. Each patient had had a 1.5 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scan to look for cortical lesions within 3 years of diagnosis. They had also undergone periodic MRIs as well as neuropsychological exams, and underwent a neuropsychological assessment at the end of the study, which included the Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological Tests (BRB-NT) and the Stroop Test.

A total of 41% of subjects had no cortical lesions according to their first MRI; 19% had 1-2 lesions, and 40% had 3 or more. At follow-up, 50% were cognitively normal (failed no tests), 25% had mild cognitive impairment (failed one or more tests), and 25% had severe cognitive impairment (failed three or more tests).

In the overall cohort, the median number of cortical lesions at baseline was 1 (interquartile range, 5.0). Among the 50% with normal cognitive function, the median was 0 (IQR, 2.5), while for the remaining 50% with cognitive impairment, the median was 3 (IQR, 7.0).

Those with 3 or more lesions had increased odds of cognitive impairment at follow-up (odds ratio, 3.70; P < .001), with an accuracy of 65% (95% confidence interval, 58%-72%), specificity of 75% (95% CI, 65%-84%), and a sensitivity of 55% (95% CI, 44%-66%). Three or more lesions discriminated between cognitive impairment and no impairment with an area under the curve of 0.67.

Individuals with no cognitive impairment had a median 0 lesions (IQR, 2.5), those with mild cognitive impairment had a median of 2.0 (IQR, 6.0), and those with severe cognitive impairment had 4.0 (IQR, 7.25).

In a multinomial regression model, 3 or more baseline cortical lesions were associated with a greater than threefold risk of severe cognitive impairment (OR, 3.33; P = .01).

Of subjects with 0 baseline lesions, 62% were cognitively normal at follow-up. In the 1-2 lesion group, 64% were normal. In the 3 or more group, 31% were cognitively normal (P < .001). In the 0 lesion group, 26% had mild cognitive impairment and 12% had severe cognitive impairment. In the 3 or more group, 28% had mild cognitive impairment, and 41% had severe cognitive impairment.

During the Q&A session following the talk, Dr. Ziccardi was asked if the group compared cortical lesions to other MRI correlates of cognitive impairment, such as gray matter volume or white matter integrity. He responded that the group is looking into those comparisons, and recently found that neither the number nor the volume of white matter lesions improved the accuracy of the predictive models based on the number of cortical lesions. The group is also looking into the applicability of gray matter volume.

, according to findings from a new analysis. The findings had good accuracy, and could help clinicians monitor and treat cognitive impairment as it develops, according to Stefano Ziccardi, PhD, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Verona in Italy.

“The number of cortical lesions at MS diagnosis accurately discriminates between the presence or the absence of cognitive impairment after diagnosis of MS, and this should be considered a predictive marker of long-term cognitive impairment in these patients. Early cortical lesion evaluation should be conducted in each MS patient to anticipate the manifestation of cognitive problems to improve the monitoring of cognitive abilities, improve the diagnosis of cognitive impairment, enable prompt intervention as necessary,” said Dr. Ziccardi at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

Cortical lesions are highly prevalent in MS, perhaps more so than white matter lesions, said Dr. Ziccardi. They are associated with clinical disability and lead to disease progression. “However, prognostic data about the role of early cortical lesions with reference to long-term cognitive impairment are still missing,” said Dr. Ziccardi.

That’s important because cognitive impairment is very common in MS, affecting between one-third and two-thirds of patients. It may appear early in the disease course and worsen over time, and it predicts worse clinical and neurological progression. And it presents a clinical challenge. “Clinicians struggle to predict the evolution of cognitive abilities over time,” said Dr. Ziccardi.

The findings drew praise from Iris-Katharina Penner, PhD, who comoderated the session. “I think the important point … is that the predictive value of cortical lesions is very high, because it indicates finally that we probably have a patient at risk for developing cognitive impairment in the future,” said Dr. Penner, who is a neuropsychologist and cognitive neuroscientist at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Clinicians often don’t pay enough attention to cognition and the complexities of MS, said Mark Gudesblatt, MD, who was asked to comment. “It’s just adding layers of complexity. We’re peeling back the onion and you realize it’s a really complicated disease. It’s not just white matter plaques, gray matter plaques, disconnection syndrome, wires cut, atrophy, ongoing inflammation, immune deficiency. All these diseases are fascinating. And we think we’re experts. But the fact is, we have much to learn,” said Dr. Gudesblatt, who is medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center at South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, New York.

The researchers analyzed data from 170 patients with MS who had a disease duration of approximately 20 years. Among the study cohort 62 patients were female, and the mean duration of disease was 19.2 years. Each patient had had a 1.5 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scan to look for cortical lesions within 3 years of diagnosis. They had also undergone periodic MRIs as well as neuropsychological exams, and underwent a neuropsychological assessment at the end of the study, which included the Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological Tests (BRB-NT) and the Stroop Test.

A total of 41% of subjects had no cortical lesions according to their first MRI; 19% had 1-2 lesions, and 40% had 3 or more. At follow-up, 50% were cognitively normal (failed no tests), 25% had mild cognitive impairment (failed one or more tests), and 25% had severe cognitive impairment (failed three or more tests).

In the overall cohort, the median number of cortical lesions at baseline was 1 (interquartile range, 5.0). Among the 50% with normal cognitive function, the median was 0 (IQR, 2.5), while for the remaining 50% with cognitive impairment, the median was 3 (IQR, 7.0).

Those with 3 or more lesions had increased odds of cognitive impairment at follow-up (odds ratio, 3.70; P < .001), with an accuracy of 65% (95% confidence interval, 58%-72%), specificity of 75% (95% CI, 65%-84%), and a sensitivity of 55% (95% CI, 44%-66%). Three or more lesions discriminated between cognitive impairment and no impairment with an area under the curve of 0.67.

Individuals with no cognitive impairment had a median 0 lesions (IQR, 2.5), those with mild cognitive impairment had a median of 2.0 (IQR, 6.0), and those with severe cognitive impairment had 4.0 (IQR, 7.25).

In a multinomial regression model, 3 or more baseline cortical lesions were associated with a greater than threefold risk of severe cognitive impairment (OR, 3.33; P = .01).

Of subjects with 0 baseline lesions, 62% were cognitively normal at follow-up. In the 1-2 lesion group, 64% were normal. In the 3 or more group, 31% were cognitively normal (P < .001). In the 0 lesion group, 26% had mild cognitive impairment and 12% had severe cognitive impairment. In the 3 or more group, 28% had mild cognitive impairment, and 41% had severe cognitive impairment.

During the Q&A session following the talk, Dr. Ziccardi was asked if the group compared cortical lesions to other MRI correlates of cognitive impairment, such as gray matter volume or white matter integrity. He responded that the group is looking into those comparisons, and recently found that neither the number nor the volume of white matter lesions improved the accuracy of the predictive models based on the number of cortical lesions. The group is also looking into the applicability of gray matter volume.

, according to findings from a new analysis. The findings had good accuracy, and could help clinicians monitor and treat cognitive impairment as it develops, according to Stefano Ziccardi, PhD, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Verona in Italy.

“The number of cortical lesions at MS diagnosis accurately discriminates between the presence or the absence of cognitive impairment after diagnosis of MS, and this should be considered a predictive marker of long-term cognitive impairment in these patients. Early cortical lesion evaluation should be conducted in each MS patient to anticipate the manifestation of cognitive problems to improve the monitoring of cognitive abilities, improve the diagnosis of cognitive impairment, enable prompt intervention as necessary,” said Dr. Ziccardi at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

Cortical lesions are highly prevalent in MS, perhaps more so than white matter lesions, said Dr. Ziccardi. They are associated with clinical disability and lead to disease progression. “However, prognostic data about the role of early cortical lesions with reference to long-term cognitive impairment are still missing,” said Dr. Ziccardi.

That’s important because cognitive impairment is very common in MS, affecting between one-third and two-thirds of patients. It may appear early in the disease course and worsen over time, and it predicts worse clinical and neurological progression. And it presents a clinical challenge. “Clinicians struggle to predict the evolution of cognitive abilities over time,” said Dr. Ziccardi.

The findings drew praise from Iris-Katharina Penner, PhD, who comoderated the session. “I think the important point … is that the predictive value of cortical lesions is very high, because it indicates finally that we probably have a patient at risk for developing cognitive impairment in the future,” said Dr. Penner, who is a neuropsychologist and cognitive neuroscientist at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Clinicians often don’t pay enough attention to cognition and the complexities of MS, said Mark Gudesblatt, MD, who was asked to comment. “It’s just adding layers of complexity. We’re peeling back the onion and you realize it’s a really complicated disease. It’s not just white matter plaques, gray matter plaques, disconnection syndrome, wires cut, atrophy, ongoing inflammation, immune deficiency. All these diseases are fascinating. And we think we’re experts. But the fact is, we have much to learn,” said Dr. Gudesblatt, who is medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center at South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, New York.

The researchers analyzed data from 170 patients with MS who had a disease duration of approximately 20 years. Among the study cohort 62 patients were female, and the mean duration of disease was 19.2 years. Each patient had had a 1.5 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scan to look for cortical lesions within 3 years of diagnosis. They had also undergone periodic MRIs as well as neuropsychological exams, and underwent a neuropsychological assessment at the end of the study, which included the Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological Tests (BRB-NT) and the Stroop Test.

A total of 41% of subjects had no cortical lesions according to their first MRI; 19% had 1-2 lesions, and 40% had 3 or more. At follow-up, 50% were cognitively normal (failed no tests), 25% had mild cognitive impairment (failed one or more tests), and 25% had severe cognitive impairment (failed three or more tests).

In the overall cohort, the median number of cortical lesions at baseline was 1 (interquartile range, 5.0). Among the 50% with normal cognitive function, the median was 0 (IQR, 2.5), while for the remaining 50% with cognitive impairment, the median was 3 (IQR, 7.0).

Those with 3 or more lesions had increased odds of cognitive impairment at follow-up (odds ratio, 3.70; P < .001), with an accuracy of 65% (95% confidence interval, 58%-72%), specificity of 75% (95% CI, 65%-84%), and a sensitivity of 55% (95% CI, 44%-66%). Three or more lesions discriminated between cognitive impairment and no impairment with an area under the curve of 0.67.

Individuals with no cognitive impairment had a median 0 lesions (IQR, 2.5), those with mild cognitive impairment had a median of 2.0 (IQR, 6.0), and those with severe cognitive impairment had 4.0 (IQR, 7.25).

In a multinomial regression model, 3 or more baseline cortical lesions were associated with a greater than threefold risk of severe cognitive impairment (OR, 3.33; P = .01).

Of subjects with 0 baseline lesions, 62% were cognitively normal at follow-up. In the 1-2 lesion group, 64% were normal. In the 3 or more group, 31% were cognitively normal (P < .001). In the 0 lesion group, 26% had mild cognitive impairment and 12% had severe cognitive impairment. In the 3 or more group, 28% had mild cognitive impairment, and 41% had severe cognitive impairment.

During the Q&A session following the talk, Dr. Ziccardi was asked if the group compared cortical lesions to other MRI correlates of cognitive impairment, such as gray matter volume or white matter integrity. He responded that the group is looking into those comparisons, and recently found that neither the number nor the volume of white matter lesions improved the accuracy of the predictive models based on the number of cortical lesions. The group is also looking into the applicability of gray matter volume.

FROM ECTRIMS 2021

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Expert review on GI perforations

A clinical practice update expert review from the American Gastroenterological Association gives advice on management of endoscopic perforations in the gastrointestinal tract, including esophageal, gastric, duodenal and periampullary, and colon perforation.

There are various techniques for dealing with perforations, including through-the-scope clips (TTSCs), over-the-scope clips (OTSCs), self-expanding metal stents (SEMS), and endoscopic suturing. Newer methods include biological glue and esophageal vacuum therapy. These techniques have been the subject of various retrospective analyses, but few prospective studies have examined their safety and efficacy.

In the expert review, published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, authors led by Jeffrey H. Lee, MD, MPH, AGAF, of the department of gastroenterology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, emphasized that gastroenterologists should have a perforation protocol in place and practice procedures that will be used to address perforations. Endoscopists should also recognize their own limits and know when a patient should be sent to experienced, high-volume centers for further care.

In the event of a perforation, the entire team should be notified immediately, and carbon dioxide insufflation should be used at a low flow setting. The endoscopist should clean up luminal material to reduce the chance of peritoneal contamination, and then treat with an antibiotic regimen that counters gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria.

Esophageal perforation

Esophageal perforations most commonly occur during dilation of strictures, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Perforations of the mucosal flap may happen during so-called third-space endoscopy techniques like peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). Small perforations can be readily addressed with TTSCs. Larger perforations call for some combination of TTSCs, endoscopic suturing, fibrin glue injection, or esophageal stenting, though the latter is discouraged because of the potential for erosion.

A more concerning complication of POEM is delayed barrier failure, which can cause leaks, mediastinitis, or peritonitis. These complications have been estimated to occur in 0.2%-1.1% of cases.

In the event of an esophageal perforation, the area should be kept clean by suctioning, or by altering patient position if required. Perforations 1-2 cm in size can be closed using OTSCs. Excessive bleeding or larger tears can be addressed using a fully covered SEMS.

Leaks that occur in the ensuing days after the procedure should be closed using TTSCs, OTSCs, or endosuturing, followed by putting in a fully covered stent. Esophageal fistula should be addressed with a fully covered stent with a tight fit.

Endoscopic vacuum therapy is a newer technique to address large or persistent esophageal perforations. A review found it had a 96% success rate for esophageal perforations.

Gastric perforations

Gastric perforations often result from peptic ulcer disease or ingestion of something caustic, and it is a high risk during EMR and ESD procedures (0.4%-0.7% intraprocedural risk). The proximal gastric wall isn’t thick as in the gastric antrum, so proximal endoscopic resections require extra care. Lengthy procedures should be done under anesthesia. Ongoing gaseous insufflation during a perforation may worsen the problem because of heightened intraperitoneal pressure. OTSCs may be a better choice than TTSCs for 1-3 cm perforations, while endoloop/TTSC can be used for larger ones.

Duodenal and periampullary perforations

Duodenal and periampullary perforations occur during duodenal stricture dilation, EMR, endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic ultrasound, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ECRP). The thin duodenal wall makes it more susceptible to perforation than the esophagus, stomach, or colon.

Closing a duodenum perforation can be difficult. Type 1 perforations typically show sudden bleeding and lumen deflation, and often require surgical intervention. Some recent reports have suggested success with TTSCs, OTSCs, band ligation, and endoloops. Type 2 perforations are less obvious, and the endoscopist must examine the gas pattern on fluoroscopic beneath the liver or in the area of the right kidney. Retroperitoneal air following ERCP, if asymptomatic, doesn’t necessarily require intervention.

The challenges presented by the duodenum mean that, for large duodenal polyps, EMR should only be done by experienced endoscopists who are skilled at mucosal closure, and only experts should attempt ESD. Proteolytic enzymes from the pancreas can also pool in the duodenum, which can degrade muscle tissue and lead to delayed perforations. TTSC, OTSC, endosuturing, polymer gels or sheets, and TTSC combined with endoloop cinching have been used to close resection-associated perforations.

Colon perforation

Colon perforation may be caused by diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or occasionally colonic obstruction. Iatrogenic causes are more common and include endoscopic resection, hot forceps biopsy, dilation of stricture resulting from radiation or Crohn’s disease, colonic stenting, and advancement of colonoscope across angulations or into diverticula without straightening the endoscope

Large perforations are usually immediately noticeable and should be treated surgically, as should hemodynamic instability or delayed perforations with peritoneal signs.

Endoscopic closure should be attempted when the perforation site is clean, and lower rectal perforations can generally be repaired with TTSC, OTSC, or endoscopic suturing. In the cecum, or in a torturous or unclean colon, it may be difficult or dangerous to remove the colonoscope and insert an OTSC, and endoscopic suturing may not be possible, making TTSC the only procedure available for right colon perforations. The X-Tack Endoscopic HeliX Tacking System is a recently introduced, through-the-scope technology that places suture-tethered tacks into tissue surrounding the perforation and cinches it together. The system in principle can close large or irregular colonic and small bowel perforations using gastroscopes and colonoscopes, but no human studies have yet been published.

Conclusion

This update was a collaborative effort by four endoscopists who felt that it was timely to review the issue of perforations since they can be serious and challenging to manage. The evolution of endoscopic techniques over the last few years, however, has made the closure of spontaneous and iatrogenic perforations much less fear provoking, and they wished to summarize the approaches to a variety of such situations in order to guide practitioners who may encounter them.

“Although perforation is a serious event, with novel endoscopic techniques and tools, the endoscopist should no longer be paralyzed when it occurs,” the authors concluded.

Some authors reported relationships, such as consulting for or royalties from, device companies such as Medtronic and Boston Scientific. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

This article was updated Oct. 25, 2021.

A clinical practice update expert review from the American Gastroenterological Association gives advice on management of endoscopic perforations in the gastrointestinal tract, including esophageal, gastric, duodenal and periampullary, and colon perforation.

There are various techniques for dealing with perforations, including through-the-scope clips (TTSCs), over-the-scope clips (OTSCs), self-expanding metal stents (SEMS), and endoscopic suturing. Newer methods include biological glue and esophageal vacuum therapy. These techniques have been the subject of various retrospective analyses, but few prospective studies have examined their safety and efficacy.

In the expert review, published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, authors led by Jeffrey H. Lee, MD, MPH, AGAF, of the department of gastroenterology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, emphasized that gastroenterologists should have a perforation protocol in place and practice procedures that will be used to address perforations. Endoscopists should also recognize their own limits and know when a patient should be sent to experienced, high-volume centers for further care.

In the event of a perforation, the entire team should be notified immediately, and carbon dioxide insufflation should be used at a low flow setting. The endoscopist should clean up luminal material to reduce the chance of peritoneal contamination, and then treat with an antibiotic regimen that counters gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria.

Esophageal perforation

Esophageal perforations most commonly occur during dilation of strictures, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Perforations of the mucosal flap may happen during so-called third-space endoscopy techniques like peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). Small perforations can be readily addressed with TTSCs. Larger perforations call for some combination of TTSCs, endoscopic suturing, fibrin glue injection, or esophageal stenting, though the latter is discouraged because of the potential for erosion.

A more concerning complication of POEM is delayed barrier failure, which can cause leaks, mediastinitis, or peritonitis. These complications have been estimated to occur in 0.2%-1.1% of cases.

In the event of an esophageal perforation, the area should be kept clean by suctioning, or by altering patient position if required. Perforations 1-2 cm in size can be closed using OTSCs. Excessive bleeding or larger tears can be addressed using a fully covered SEMS.

Leaks that occur in the ensuing days after the procedure should be closed using TTSCs, OTSCs, or endosuturing, followed by putting in a fully covered stent. Esophageal fistula should be addressed with a fully covered stent with a tight fit.

Endoscopic vacuum therapy is a newer technique to address large or persistent esophageal perforations. A review found it had a 96% success rate for esophageal perforations.

Gastric perforations

Gastric perforations often result from peptic ulcer disease or ingestion of something caustic, and it is a high risk during EMR and ESD procedures (0.4%-0.7% intraprocedural risk). The proximal gastric wall isn’t thick as in the gastric antrum, so proximal endoscopic resections require extra care. Lengthy procedures should be done under anesthesia. Ongoing gaseous insufflation during a perforation may worsen the problem because of heightened intraperitoneal pressure. OTSCs may be a better choice than TTSCs for 1-3 cm perforations, while endoloop/TTSC can be used for larger ones.

Duodenal and periampullary perforations

Duodenal and periampullary perforations occur during duodenal stricture dilation, EMR, endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic ultrasound, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ECRP). The thin duodenal wall makes it more susceptible to perforation than the esophagus, stomach, or colon.

Closing a duodenum perforation can be difficult. Type 1 perforations typically show sudden bleeding and lumen deflation, and often require surgical intervention. Some recent reports have suggested success with TTSCs, OTSCs, band ligation, and endoloops. Type 2 perforations are less obvious, and the endoscopist must examine the gas pattern on fluoroscopic beneath the liver or in the area of the right kidney. Retroperitoneal air following ERCP, if asymptomatic, doesn’t necessarily require intervention.

The challenges presented by the duodenum mean that, for large duodenal polyps, EMR should only be done by experienced endoscopists who are skilled at mucosal closure, and only experts should attempt ESD. Proteolytic enzymes from the pancreas can also pool in the duodenum, which can degrade muscle tissue and lead to delayed perforations. TTSC, OTSC, endosuturing, polymer gels or sheets, and TTSC combined with endoloop cinching have been used to close resection-associated perforations.

Colon perforation

Colon perforation may be caused by diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or occasionally colonic obstruction. Iatrogenic causes are more common and include endoscopic resection, hot forceps biopsy, dilation of stricture resulting from radiation or Crohn’s disease, colonic stenting, and advancement of colonoscope across angulations or into diverticula without straightening the endoscope

Large perforations are usually immediately noticeable and should be treated surgically, as should hemodynamic instability or delayed perforations with peritoneal signs.

Endoscopic closure should be attempted when the perforation site is clean, and lower rectal perforations can generally be repaired with TTSC, OTSC, or endoscopic suturing. In the cecum, or in a torturous or unclean colon, it may be difficult or dangerous to remove the colonoscope and insert an OTSC, and endoscopic suturing may not be possible, making TTSC the only procedure available for right colon perforations. The X-Tack Endoscopic HeliX Tacking System is a recently introduced, through-the-scope technology that places suture-tethered tacks into tissue surrounding the perforation and cinches it together. The system in principle can close large or irregular colonic and small bowel perforations using gastroscopes and colonoscopes, but no human studies have yet been published.

Conclusion

This update was a collaborative effort by four endoscopists who felt that it was timely to review the issue of perforations since they can be serious and challenging to manage. The evolution of endoscopic techniques over the last few years, however, has made the closure of spontaneous and iatrogenic perforations much less fear provoking, and they wished to summarize the approaches to a variety of such situations in order to guide practitioners who may encounter them.

“Although perforation is a serious event, with novel endoscopic techniques and tools, the endoscopist should no longer be paralyzed when it occurs,” the authors concluded.

Some authors reported relationships, such as consulting for or royalties from, device companies such as Medtronic and Boston Scientific. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

This article was updated Oct. 25, 2021.

A clinical practice update expert review from the American Gastroenterological Association gives advice on management of endoscopic perforations in the gastrointestinal tract, including esophageal, gastric, duodenal and periampullary, and colon perforation.

There are various techniques for dealing with perforations, including through-the-scope clips (TTSCs), over-the-scope clips (OTSCs), self-expanding metal stents (SEMS), and endoscopic suturing. Newer methods include biological glue and esophageal vacuum therapy. These techniques have been the subject of various retrospective analyses, but few prospective studies have examined their safety and efficacy.

In the expert review, published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, authors led by Jeffrey H. Lee, MD, MPH, AGAF, of the department of gastroenterology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, emphasized that gastroenterologists should have a perforation protocol in place and practice procedures that will be used to address perforations. Endoscopists should also recognize their own limits and know when a patient should be sent to experienced, high-volume centers for further care.

In the event of a perforation, the entire team should be notified immediately, and carbon dioxide insufflation should be used at a low flow setting. The endoscopist should clean up luminal material to reduce the chance of peritoneal contamination, and then treat with an antibiotic regimen that counters gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria.

Esophageal perforation

Esophageal perforations most commonly occur during dilation of strictures, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Perforations of the mucosal flap may happen during so-called third-space endoscopy techniques like peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). Small perforations can be readily addressed with TTSCs. Larger perforations call for some combination of TTSCs, endoscopic suturing, fibrin glue injection, or esophageal stenting, though the latter is discouraged because of the potential for erosion.

A more concerning complication of POEM is delayed barrier failure, which can cause leaks, mediastinitis, or peritonitis. These complications have been estimated to occur in 0.2%-1.1% of cases.

In the event of an esophageal perforation, the area should be kept clean by suctioning, or by altering patient position if required. Perforations 1-2 cm in size can be closed using OTSCs. Excessive bleeding or larger tears can be addressed using a fully covered SEMS.

Leaks that occur in the ensuing days after the procedure should be closed using TTSCs, OTSCs, or endosuturing, followed by putting in a fully covered stent. Esophageal fistula should be addressed with a fully covered stent with a tight fit.

Endoscopic vacuum therapy is a newer technique to address large or persistent esophageal perforations. A review found it had a 96% success rate for esophageal perforations.

Gastric perforations

Gastric perforations often result from peptic ulcer disease or ingestion of something caustic, and it is a high risk during EMR and ESD procedures (0.4%-0.7% intraprocedural risk). The proximal gastric wall isn’t thick as in the gastric antrum, so proximal endoscopic resections require extra care. Lengthy procedures should be done under anesthesia. Ongoing gaseous insufflation during a perforation may worsen the problem because of heightened intraperitoneal pressure. OTSCs may be a better choice than TTSCs for 1-3 cm perforations, while endoloop/TTSC can be used for larger ones.

Duodenal and periampullary perforations

Duodenal and periampullary perforations occur during duodenal stricture dilation, EMR, endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic ultrasound, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ECRP). The thin duodenal wall makes it more susceptible to perforation than the esophagus, stomach, or colon.

Closing a duodenum perforation can be difficult. Type 1 perforations typically show sudden bleeding and lumen deflation, and often require surgical intervention. Some recent reports have suggested success with TTSCs, OTSCs, band ligation, and endoloops. Type 2 perforations are less obvious, and the endoscopist must examine the gas pattern on fluoroscopic beneath the liver or in the area of the right kidney. Retroperitoneal air following ERCP, if asymptomatic, doesn’t necessarily require intervention.

The challenges presented by the duodenum mean that, for large duodenal polyps, EMR should only be done by experienced endoscopists who are skilled at mucosal closure, and only experts should attempt ESD. Proteolytic enzymes from the pancreas can also pool in the duodenum, which can degrade muscle tissue and lead to delayed perforations. TTSC, OTSC, endosuturing, polymer gels or sheets, and TTSC combined with endoloop cinching have been used to close resection-associated perforations.

Colon perforation

Colon perforation may be caused by diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or occasionally colonic obstruction. Iatrogenic causes are more common and include endoscopic resection, hot forceps biopsy, dilation of stricture resulting from radiation or Crohn’s disease, colonic stenting, and advancement of colonoscope across angulations or into diverticula without straightening the endoscope

Large perforations are usually immediately noticeable and should be treated surgically, as should hemodynamic instability or delayed perforations with peritoneal signs.

Endoscopic closure should be attempted when the perforation site is clean, and lower rectal perforations can generally be repaired with TTSC, OTSC, or endoscopic suturing. In the cecum, or in a torturous or unclean colon, it may be difficult or dangerous to remove the colonoscope and insert an OTSC, and endoscopic suturing may not be possible, making TTSC the only procedure available for right colon perforations. The X-Tack Endoscopic HeliX Tacking System is a recently introduced, through-the-scope technology that places suture-tethered tacks into tissue surrounding the perforation and cinches it together. The system in principle can close large or irregular colonic and small bowel perforations using gastroscopes and colonoscopes, but no human studies have yet been published.

Conclusion

This update was a collaborative effort by four endoscopists who felt that it was timely to review the issue of perforations since they can be serious and challenging to manage. The evolution of endoscopic techniques over the last few years, however, has made the closure of spontaneous and iatrogenic perforations much less fear provoking, and they wished to summarize the approaches to a variety of such situations in order to guide practitioners who may encounter them.

“Although perforation is a serious event, with novel endoscopic techniques and tools, the endoscopist should no longer be paralyzed when it occurs,” the authors concluded.

Some authors reported relationships, such as consulting for or royalties from, device companies such as Medtronic and Boston Scientific. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

This article was updated Oct. 25, 2021.

FROM THE CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Melatonin improves sleep in MS

according to a new pilot study.

The study included only 30 patients, but the findings suggest that melatonin could potentially help patients with MS who have sleep issues, according to Wan-Yu Hsu, PhD, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

There is no optimal management of sleep issues for these patients, and objective studies of sleep in patients with MS are scarce, said Dr. Hsu, who is an associate specialist in the department of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. She worked with Riley Bove, MD, who is an associate professor of neurology at UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“Melatonin use was associated with improvement in sleep quality and sleep disturbance in MS patients, although there was no significant change in other outcomes, like daytime sleepiness, mood, and walking ability” Dr. Hsu said in an interview.

Melatonin is inexpensive and readily available over the counter, but it’s too soon to begin recommending it to MS patients experiencing sleep problems, according to Dr. Hsu. “It’s a good start that we’re seeing some effects here with this relatively small group of people. Larger studies are needed to unravel the complex relationship between MS and sleep disturbances, as well as develop successful interventions. But for now, since melatonin is an over-the-counter, low-cost supplement, many patients are trying it already.”

Melatonin regulates the sleep-wake cycle, and previous research has shown a decrease in melatonin serum levels as a result of corticosteroid administration. Other work has suggested that the decline of melatonin secretion in MS may reflect progressive failure of the pineal gland in the pathogenesis of MS. “The cause of sleep problems can be lesions and neural damage to brain structures involved in sleep, or symptoms that indirectly disrupt sleep,” she said.

Indeed, sleep issues in MS are common and wide-ranging, according to Mark Gudesblatt, MD, who was asked to comment on the study. His group previously reported that 65% of people with MS who reported fatigue had undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea. He also pointed out that disruption of the neural network also disrupts sleep. “That is not only sleep-disordered breathing, that’s sleep onset, REM latency, and sleep efficiency,” said Dr. Gudesblatt, who is medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center at South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, N.Y.

Dr. Gudesblatt cautioned that melatonin, as a dietary supplement, is unregulated. The potency listed on the package may not be accurate and also may not be the correct dose for the patient. “It’s fraught with problems, but ultimately it’s relatively safe,” said Dr. Gudesblatt.

The study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Participants had a Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score of 5 or more, or an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score higher than 14 at baseline. Other baseline assessments included patient-reported outcomes for sleep disturbances, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, fatigue, walking ability, and mood. Half of the participants received melatonin for the first 2 weeks and then switched to placebo. The other half started with placebo and moved over to melatonin at the beginning of week 3.

Participants in the trial started out at 0.5 mg melatonin and were stepped up to 3.0 mg after 3 days if they didn't feel it was working, both when taking melatonin and when taking placebo. Of the 30 patients, 24 stepped up to 3.0 mg when they were receiving melatonin.*

During the second and fourth weeks, participants wore an actigraph watch to measure their physical and sleep activities, and then repeated the patient-reported outcome measures at the end of weeks 2 and 4. Melatonin improved average sleep time (6.96 vs. 6.67 hours; P = .03) as measured by the actigraph watch. Sleep efficiency was also nominally improved (84.7% vs. 83.2%), though the result was not statistically significant (P = .07). Other trends toward statistical significance included improvements in ISI (–3.5 vs. –2.4; P = .07), change in PSQI component 1 (–0.03 vs. 0.0; P = .07), and change in the NeuroQoL-Fatigue score (–4.7 vs. –2.4; P = .06).

Dr. Hsu hopes to conduct larger studies to examine how the disease-modifying therapies might affect the results of the study.

The study was funded by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Dr. Hsu and Dr. Gudesblatt have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on Oct. 15.

according to a new pilot study.

The study included only 30 patients, but the findings suggest that melatonin could potentially help patients with MS who have sleep issues, according to Wan-Yu Hsu, PhD, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

There is no optimal management of sleep issues for these patients, and objective studies of sleep in patients with MS are scarce, said Dr. Hsu, who is an associate specialist in the department of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. She worked with Riley Bove, MD, who is an associate professor of neurology at UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“Melatonin use was associated with improvement in sleep quality and sleep disturbance in MS patients, although there was no significant change in other outcomes, like daytime sleepiness, mood, and walking ability” Dr. Hsu said in an interview.

Melatonin is inexpensive and readily available over the counter, but it’s too soon to begin recommending it to MS patients experiencing sleep problems, according to Dr. Hsu. “It’s a good start that we’re seeing some effects here with this relatively small group of people. Larger studies are needed to unravel the complex relationship between MS and sleep disturbances, as well as develop successful interventions. But for now, since melatonin is an over-the-counter, low-cost supplement, many patients are trying it already.”

Melatonin regulates the sleep-wake cycle, and previous research has shown a decrease in melatonin serum levels as a result of corticosteroid administration. Other work has suggested that the decline of melatonin secretion in MS may reflect progressive failure of the pineal gland in the pathogenesis of MS. “The cause of sleep problems can be lesions and neural damage to brain structures involved in sleep, or symptoms that indirectly disrupt sleep,” she said.

Indeed, sleep issues in MS are common and wide-ranging, according to Mark Gudesblatt, MD, who was asked to comment on the study. His group previously reported that 65% of people with MS who reported fatigue had undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea. He also pointed out that disruption of the neural network also disrupts sleep. “That is not only sleep-disordered breathing, that’s sleep onset, REM latency, and sleep efficiency,” said Dr. Gudesblatt, who is medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center at South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, N.Y.

Dr. Gudesblatt cautioned that melatonin, as a dietary supplement, is unregulated. The potency listed on the package may not be accurate and also may not be the correct dose for the patient. “It’s fraught with problems, but ultimately it’s relatively safe,” said Dr. Gudesblatt.

The study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Participants had a Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score of 5 or more, or an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score higher than 14 at baseline. Other baseline assessments included patient-reported outcomes for sleep disturbances, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, fatigue, walking ability, and mood. Half of the participants received melatonin for the first 2 weeks and then switched to placebo. The other half started with placebo and moved over to melatonin at the beginning of week 3.

Participants in the trial started out at 0.5 mg melatonin and were stepped up to 3.0 mg after 3 days if they didn't feel it was working, both when taking melatonin and when taking placebo. Of the 30 patients, 24 stepped up to 3.0 mg when they were receiving melatonin.*

During the second and fourth weeks, participants wore an actigraph watch to measure their physical and sleep activities, and then repeated the patient-reported outcome measures at the end of weeks 2 and 4. Melatonin improved average sleep time (6.96 vs. 6.67 hours; P = .03) as measured by the actigraph watch. Sleep efficiency was also nominally improved (84.7% vs. 83.2%), though the result was not statistically significant (P = .07). Other trends toward statistical significance included improvements in ISI (–3.5 vs. –2.4; P = .07), change in PSQI component 1 (–0.03 vs. 0.0; P = .07), and change in the NeuroQoL-Fatigue score (–4.7 vs. –2.4; P = .06).

Dr. Hsu hopes to conduct larger studies to examine how the disease-modifying therapies might affect the results of the study.

The study was funded by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Dr. Hsu and Dr. Gudesblatt have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on Oct. 15.

according to a new pilot study.

The study included only 30 patients, but the findings suggest that melatonin could potentially help patients with MS who have sleep issues, according to Wan-Yu Hsu, PhD, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

There is no optimal management of sleep issues for these patients, and objective studies of sleep in patients with MS are scarce, said Dr. Hsu, who is an associate specialist in the department of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. She worked with Riley Bove, MD, who is an associate professor of neurology at UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“Melatonin use was associated with improvement in sleep quality and sleep disturbance in MS patients, although there was no significant change in other outcomes, like daytime sleepiness, mood, and walking ability” Dr. Hsu said in an interview.

Melatonin is inexpensive and readily available over the counter, but it’s too soon to begin recommending it to MS patients experiencing sleep problems, according to Dr. Hsu. “It’s a good start that we’re seeing some effects here with this relatively small group of people. Larger studies are needed to unravel the complex relationship between MS and sleep disturbances, as well as develop successful interventions. But for now, since melatonin is an over-the-counter, low-cost supplement, many patients are trying it already.”

Melatonin regulates the sleep-wake cycle, and previous research has shown a decrease in melatonin serum levels as a result of corticosteroid administration. Other work has suggested that the decline of melatonin secretion in MS may reflect progressive failure of the pineal gland in the pathogenesis of MS. “The cause of sleep problems can be lesions and neural damage to brain structures involved in sleep, or symptoms that indirectly disrupt sleep,” she said.