User login

Pre-authorization is illegal, unethical, and adversely disrupts patient care

Pre-authorization is a despicable scam. It’s a national racket by avaricious insurance companies, and it must be stopped. Since it first reared its ugly head 2 decades ago, it has inflicted great harm to countless patients, demoralized their physicians, and needlessly imposed higher costs in clinical practice while simultaneously depriving patients of the treatment their physicians prescribed for them.

Pre-authorization has become the nemesis of medical care. It recklessly and arbitrarily vetoes the clinical decision-making of competent physicians doing their best to address their patients’ medical needs. Yet, despite its outrageous disruption of the clinical practice of hundreds of thousands of practitioners, it continues unabated, without a forceful pushback. It has become the “new normal,” but in fact, it is the “new abnormal.” This harassment of clinicians must be outlawed.

Think about it: Pre-authorization is essentially practicing medicine without a license, which is a felony. When a remote and invisible insurance company staff member either prevents a patient from receiving a medication prescribed by that patient’s personal physician following a full diagnostic evaluation or pressures the physician to prescribe a different medication, he/she is basically deciding what the treatment should be for a patient who that insurance company employee has never seen, let alone examined. How did for-profit insurance companies empower themselves to tyrannize clinical practice so that the treatment administered isn’t customized to the patient’s need but instead to fatten the profits of the insurance company? That is patently unethical, in addition to being a felonious practice of medicine by an absentee person unqualified to decide what a patient needs without a direct examination.

Consider the multiple malignant consequences of such brazen and egregious restriction or distortion of medical care:

1. The physician’s clinical judgment is abrogated, even when it is clearly in the patient’s best interest.

2. Patients are deprived of receiving the medication that their personal physician deemed optimal.

3. The physician in private practice has to spend an inordinate amount of time going to web sites, such as CoverMyMeds.com, to fill out extensive forms containing numerous questions about the patient’s illness and diagnosis, and then selecting from a list of medications that the insurance company ironically labels as “smart choices.” These medications often are not necessarily what the physician considers a smart choice, but are the cheapest (regardless of whether their efficacy, safety, or tolerability are the best fit for the patient). After the physician completes the forms, there is a waiting period, followed by additional questions that consume more valuable time and take the physician away from seeing more patients. Some busy colleagues told me they often take the pre-authorization “homework” with them to do at home, consuming part of what should be their family time. For physicians who see patients in an institutional “clinic,” medical assistants or nurses must be hired at significant expense to work full-time on pre-authorizations, adding to the overhead of the clinic while increasing the profits of the third-party insurer.

4. Patients who have been stable on a medication for months, even years, are forced to switch to another medication if they change jobs and become covered by a different insurance company that does not have the patient’s current medication on their infamous list of “approved drugs,” an evil euphemism for “cheapest drugs.” Switching medications is known to be a possibly hazardous process with lower efficacy and/or tolerability, but that appears to be irrelevant to the insurance company. The welfare of the patient is not on the insurance company’s radar screen, perhaps because it is crowded out by dollar signs. We should all urge policymakers to pass legislation that goes beyond requiring insurance companies to cover “pre-existing conditions” and expands it to cover “pre-existing medications.”

Continue to: Often, frustrated physicians...

5. Often, frustrated physicians who do not want to see their patients receive a medication they do not believe is appropriate may spend valuable time writing letters of appeal, making phone calls, or printing and faxing scientific articles to the insurance company to convince them to authorize a medication that is not on the “approved list.” Based on my own clinical experience, that justification sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t.

6. Physicians are inevitably and understandably demoralized because their expertise and sound clinical judgment are arbitrarily dismissed and overruled by an invisible insurance employee whose knowledge about and compassion for the patient is miniscule at best.

7. New medication development has collided with the biased despotism of pre-authorization, which generally rejects any new medication (always costlier than generics) irrespective of whether the new medication was demonstrated in controlled clinical trials to have a measurably better profile than older generics. This has ominous implications for numerous medical disorders that do not have any approved medications (for psychiatry, a published study1 found that 82% of DSM disorders do not have a FDA-approved medication).

The lack of utilizing newly introduced medications has discouraged the pharmaceutical industry from investing to develop innovative new mechanisms of action for a variety of complex neuropsychiatric medical conditions. Some companies have already abandoned psychiatric drug development, which is dire for clinical care because pharmaceutical companies are the only entities that develop new treatments for our patients (some health care professionals wish the government had a pharmaceutical agency that develops medications for various illness, but no such agency has ever existed).

8. Hospitalization for a seriously ill patient is either denied, delayed, or eventually approved for an absurdly short period (a few days), which is woefully inadequate, culminating in discharging patients with unresolved symptoms. This can lead to disastrous consequences, including suicide, homicide, or incarceration.

Continue to: I have been personally infuriated...

I have been personally infuriated many times because of the adverse impact pre-authorization had on my patients. One example that still haunts me is a 23-year-old college graduate with severe treatment-resistant depression who failed multiple antidepressant trials, including IV ketamine. She harbored daily thoughts of suicide (throwing herself in front of a train, which she saw daily as she drove to work). She admitted to frequently contemplating which dress she should wear in her coffin. Based on several published double-blind studies showing that modafinil improved bipolar depression,2 I prescribed modafinil, 200 mg/d, as adjunctive treatment to venlafaxine, 300 mg/d, and she improved significantly for 10 months. Suddenly, the insurance company refused to renew her refill of modafinil, and it took 4 weeks of incessant communication (phone calls, faxes, letters, sending published articles) before it was finally approved. In the meantime, the patient deteriorated and began to have active suicidal urges. When she was restarted on modafinil, she never achieved the same level of improvement she had prior to discontinuing modafinil. The insurance company damaged this patient’s recovery with its refusal to authorize a medication that was “not approved” for depression despite the clear benefit it had provided this treatment-resistant patient for almost 1 year. Their motive was clearly to avoid covering the high cost of modafinil, regardless of this patient’s high risk of suicide.

Every physician can recite a litany of complaints about the evil of pre-authorizations. We must therefore unite and vigorously lobby legislators to pass laws that protect patients and uphold physicians’ authority to determine the right treatment for their patients. We must terminate the plague of pre-authorization that takes our patients hostage to the greed of insurance companies, who have no regard to the agony of patients who are prevented from receiving the medication that their personal physician prescribes. Physicians’ well-being would be greatly enhanced if they were not enslaved to the avarice of insurance companies.

The travesty of pre-authorization and its pervasive and deleterious effects on medical care, society, and citizens must be stopped. It’s a plague that sacrifices the practice of medicine on the altar of financial greed. Just because it has gone on for many years does not mean it should be accepted as the “new normal.” It must be condemned as the “new abnormal,” a cancerous lesion on health care delivery that must be excised and discarded.

1. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatr. 2009;2(1):29-36.

2. Nunez NA, Singh B, Romo-Nava F, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive modafinil/armodafinil in bipolar depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Bipolar Dipsord. 2019;10.1111/bdi.12859. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12859

Pre-authorization is a despicable scam. It’s a national racket by avaricious insurance companies, and it must be stopped. Since it first reared its ugly head 2 decades ago, it has inflicted great harm to countless patients, demoralized their physicians, and needlessly imposed higher costs in clinical practice while simultaneously depriving patients of the treatment their physicians prescribed for them.

Pre-authorization has become the nemesis of medical care. It recklessly and arbitrarily vetoes the clinical decision-making of competent physicians doing their best to address their patients’ medical needs. Yet, despite its outrageous disruption of the clinical practice of hundreds of thousands of practitioners, it continues unabated, without a forceful pushback. It has become the “new normal,” but in fact, it is the “new abnormal.” This harassment of clinicians must be outlawed.

Think about it: Pre-authorization is essentially practicing medicine without a license, which is a felony. When a remote and invisible insurance company staff member either prevents a patient from receiving a medication prescribed by that patient’s personal physician following a full diagnostic evaluation or pressures the physician to prescribe a different medication, he/she is basically deciding what the treatment should be for a patient who that insurance company employee has never seen, let alone examined. How did for-profit insurance companies empower themselves to tyrannize clinical practice so that the treatment administered isn’t customized to the patient’s need but instead to fatten the profits of the insurance company? That is patently unethical, in addition to being a felonious practice of medicine by an absentee person unqualified to decide what a patient needs without a direct examination.

Consider the multiple malignant consequences of such brazen and egregious restriction or distortion of medical care:

1. The physician’s clinical judgment is abrogated, even when it is clearly in the patient’s best interest.

2. Patients are deprived of receiving the medication that their personal physician deemed optimal.

3. The physician in private practice has to spend an inordinate amount of time going to web sites, such as CoverMyMeds.com, to fill out extensive forms containing numerous questions about the patient’s illness and diagnosis, and then selecting from a list of medications that the insurance company ironically labels as “smart choices.” These medications often are not necessarily what the physician considers a smart choice, but are the cheapest (regardless of whether their efficacy, safety, or tolerability are the best fit for the patient). After the physician completes the forms, there is a waiting period, followed by additional questions that consume more valuable time and take the physician away from seeing more patients. Some busy colleagues told me they often take the pre-authorization “homework” with them to do at home, consuming part of what should be their family time. For physicians who see patients in an institutional “clinic,” medical assistants or nurses must be hired at significant expense to work full-time on pre-authorizations, adding to the overhead of the clinic while increasing the profits of the third-party insurer.

4. Patients who have been stable on a medication for months, even years, are forced to switch to another medication if they change jobs and become covered by a different insurance company that does not have the patient’s current medication on their infamous list of “approved drugs,” an evil euphemism for “cheapest drugs.” Switching medications is known to be a possibly hazardous process with lower efficacy and/or tolerability, but that appears to be irrelevant to the insurance company. The welfare of the patient is not on the insurance company’s radar screen, perhaps because it is crowded out by dollar signs. We should all urge policymakers to pass legislation that goes beyond requiring insurance companies to cover “pre-existing conditions” and expands it to cover “pre-existing medications.”

Continue to: Often, frustrated physicians...

5. Often, frustrated physicians who do not want to see their patients receive a medication they do not believe is appropriate may spend valuable time writing letters of appeal, making phone calls, or printing and faxing scientific articles to the insurance company to convince them to authorize a medication that is not on the “approved list.” Based on my own clinical experience, that justification sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t.

6. Physicians are inevitably and understandably demoralized because their expertise and sound clinical judgment are arbitrarily dismissed and overruled by an invisible insurance employee whose knowledge about and compassion for the patient is miniscule at best.

7. New medication development has collided with the biased despotism of pre-authorization, which generally rejects any new medication (always costlier than generics) irrespective of whether the new medication was demonstrated in controlled clinical trials to have a measurably better profile than older generics. This has ominous implications for numerous medical disorders that do not have any approved medications (for psychiatry, a published study1 found that 82% of DSM disorders do not have a FDA-approved medication).

The lack of utilizing newly introduced medications has discouraged the pharmaceutical industry from investing to develop innovative new mechanisms of action for a variety of complex neuropsychiatric medical conditions. Some companies have already abandoned psychiatric drug development, which is dire for clinical care because pharmaceutical companies are the only entities that develop new treatments for our patients (some health care professionals wish the government had a pharmaceutical agency that develops medications for various illness, but no such agency has ever existed).

8. Hospitalization for a seriously ill patient is either denied, delayed, or eventually approved for an absurdly short period (a few days), which is woefully inadequate, culminating in discharging patients with unresolved symptoms. This can lead to disastrous consequences, including suicide, homicide, or incarceration.

Continue to: I have been personally infuriated...

I have been personally infuriated many times because of the adverse impact pre-authorization had on my patients. One example that still haunts me is a 23-year-old college graduate with severe treatment-resistant depression who failed multiple antidepressant trials, including IV ketamine. She harbored daily thoughts of suicide (throwing herself in front of a train, which she saw daily as she drove to work). She admitted to frequently contemplating which dress she should wear in her coffin. Based on several published double-blind studies showing that modafinil improved bipolar depression,2 I prescribed modafinil, 200 mg/d, as adjunctive treatment to venlafaxine, 300 mg/d, and she improved significantly for 10 months. Suddenly, the insurance company refused to renew her refill of modafinil, and it took 4 weeks of incessant communication (phone calls, faxes, letters, sending published articles) before it was finally approved. In the meantime, the patient deteriorated and began to have active suicidal urges. When she was restarted on modafinil, she never achieved the same level of improvement she had prior to discontinuing modafinil. The insurance company damaged this patient’s recovery with its refusal to authorize a medication that was “not approved” for depression despite the clear benefit it had provided this treatment-resistant patient for almost 1 year. Their motive was clearly to avoid covering the high cost of modafinil, regardless of this patient’s high risk of suicide.

Every physician can recite a litany of complaints about the evil of pre-authorizations. We must therefore unite and vigorously lobby legislators to pass laws that protect patients and uphold physicians’ authority to determine the right treatment for their patients. We must terminate the plague of pre-authorization that takes our patients hostage to the greed of insurance companies, who have no regard to the agony of patients who are prevented from receiving the medication that their personal physician prescribes. Physicians’ well-being would be greatly enhanced if they were not enslaved to the avarice of insurance companies.

The travesty of pre-authorization and its pervasive and deleterious effects on medical care, society, and citizens must be stopped. It’s a plague that sacrifices the practice of medicine on the altar of financial greed. Just because it has gone on for many years does not mean it should be accepted as the “new normal.” It must be condemned as the “new abnormal,” a cancerous lesion on health care delivery that must be excised and discarded.

Pre-authorization is a despicable scam. It’s a national racket by avaricious insurance companies, and it must be stopped. Since it first reared its ugly head 2 decades ago, it has inflicted great harm to countless patients, demoralized their physicians, and needlessly imposed higher costs in clinical practice while simultaneously depriving patients of the treatment their physicians prescribed for them.

Pre-authorization has become the nemesis of medical care. It recklessly and arbitrarily vetoes the clinical decision-making of competent physicians doing their best to address their patients’ medical needs. Yet, despite its outrageous disruption of the clinical practice of hundreds of thousands of practitioners, it continues unabated, without a forceful pushback. It has become the “new normal,” but in fact, it is the “new abnormal.” This harassment of clinicians must be outlawed.

Think about it: Pre-authorization is essentially practicing medicine without a license, which is a felony. When a remote and invisible insurance company staff member either prevents a patient from receiving a medication prescribed by that patient’s personal physician following a full diagnostic evaluation or pressures the physician to prescribe a different medication, he/she is basically deciding what the treatment should be for a patient who that insurance company employee has never seen, let alone examined. How did for-profit insurance companies empower themselves to tyrannize clinical practice so that the treatment administered isn’t customized to the patient’s need but instead to fatten the profits of the insurance company? That is patently unethical, in addition to being a felonious practice of medicine by an absentee person unqualified to decide what a patient needs without a direct examination.

Consider the multiple malignant consequences of such brazen and egregious restriction or distortion of medical care:

1. The physician’s clinical judgment is abrogated, even when it is clearly in the patient’s best interest.

2. Patients are deprived of receiving the medication that their personal physician deemed optimal.

3. The physician in private practice has to spend an inordinate amount of time going to web sites, such as CoverMyMeds.com, to fill out extensive forms containing numerous questions about the patient’s illness and diagnosis, and then selecting from a list of medications that the insurance company ironically labels as “smart choices.” These medications often are not necessarily what the physician considers a smart choice, but are the cheapest (regardless of whether their efficacy, safety, or tolerability are the best fit for the patient). After the physician completes the forms, there is a waiting period, followed by additional questions that consume more valuable time and take the physician away from seeing more patients. Some busy colleagues told me they often take the pre-authorization “homework” with them to do at home, consuming part of what should be their family time. For physicians who see patients in an institutional “clinic,” medical assistants or nurses must be hired at significant expense to work full-time on pre-authorizations, adding to the overhead of the clinic while increasing the profits of the third-party insurer.

4. Patients who have been stable on a medication for months, even years, are forced to switch to another medication if they change jobs and become covered by a different insurance company that does not have the patient’s current medication on their infamous list of “approved drugs,” an evil euphemism for “cheapest drugs.” Switching medications is known to be a possibly hazardous process with lower efficacy and/or tolerability, but that appears to be irrelevant to the insurance company. The welfare of the patient is not on the insurance company’s radar screen, perhaps because it is crowded out by dollar signs. We should all urge policymakers to pass legislation that goes beyond requiring insurance companies to cover “pre-existing conditions” and expands it to cover “pre-existing medications.”

Continue to: Often, frustrated physicians...

5. Often, frustrated physicians who do not want to see their patients receive a medication they do not believe is appropriate may spend valuable time writing letters of appeal, making phone calls, or printing and faxing scientific articles to the insurance company to convince them to authorize a medication that is not on the “approved list.” Based on my own clinical experience, that justification sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t.

6. Physicians are inevitably and understandably demoralized because their expertise and sound clinical judgment are arbitrarily dismissed and overruled by an invisible insurance employee whose knowledge about and compassion for the patient is miniscule at best.

7. New medication development has collided with the biased despotism of pre-authorization, which generally rejects any new medication (always costlier than generics) irrespective of whether the new medication was demonstrated in controlled clinical trials to have a measurably better profile than older generics. This has ominous implications for numerous medical disorders that do not have any approved medications (for psychiatry, a published study1 found that 82% of DSM disorders do not have a FDA-approved medication).

The lack of utilizing newly introduced medications has discouraged the pharmaceutical industry from investing to develop innovative new mechanisms of action for a variety of complex neuropsychiatric medical conditions. Some companies have already abandoned psychiatric drug development, which is dire for clinical care because pharmaceutical companies are the only entities that develop new treatments for our patients (some health care professionals wish the government had a pharmaceutical agency that develops medications for various illness, but no such agency has ever existed).

8. Hospitalization for a seriously ill patient is either denied, delayed, or eventually approved for an absurdly short period (a few days), which is woefully inadequate, culminating in discharging patients with unresolved symptoms. This can lead to disastrous consequences, including suicide, homicide, or incarceration.

Continue to: I have been personally infuriated...

I have been personally infuriated many times because of the adverse impact pre-authorization had on my patients. One example that still haunts me is a 23-year-old college graduate with severe treatment-resistant depression who failed multiple antidepressant trials, including IV ketamine. She harbored daily thoughts of suicide (throwing herself in front of a train, which she saw daily as she drove to work). She admitted to frequently contemplating which dress she should wear in her coffin. Based on several published double-blind studies showing that modafinil improved bipolar depression,2 I prescribed modafinil, 200 mg/d, as adjunctive treatment to venlafaxine, 300 mg/d, and she improved significantly for 10 months. Suddenly, the insurance company refused to renew her refill of modafinil, and it took 4 weeks of incessant communication (phone calls, faxes, letters, sending published articles) before it was finally approved. In the meantime, the patient deteriorated and began to have active suicidal urges. When she was restarted on modafinil, she never achieved the same level of improvement she had prior to discontinuing modafinil. The insurance company damaged this patient’s recovery with its refusal to authorize a medication that was “not approved” for depression despite the clear benefit it had provided this treatment-resistant patient for almost 1 year. Their motive was clearly to avoid covering the high cost of modafinil, regardless of this patient’s high risk of suicide.

Every physician can recite a litany of complaints about the evil of pre-authorizations. We must therefore unite and vigorously lobby legislators to pass laws that protect patients and uphold physicians’ authority to determine the right treatment for their patients. We must terminate the plague of pre-authorization that takes our patients hostage to the greed of insurance companies, who have no regard to the agony of patients who are prevented from receiving the medication that their personal physician prescribes. Physicians’ well-being would be greatly enhanced if they were not enslaved to the avarice of insurance companies.

The travesty of pre-authorization and its pervasive and deleterious effects on medical care, society, and citizens must be stopped. It’s a plague that sacrifices the practice of medicine on the altar of financial greed. Just because it has gone on for many years does not mean it should be accepted as the “new normal.” It must be condemned as the “new abnormal,” a cancerous lesion on health care delivery that must be excised and discarded.

1. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatr. 2009;2(1):29-36.

2. Nunez NA, Singh B, Romo-Nava F, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive modafinil/armodafinil in bipolar depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Bipolar Dipsord. 2019;10.1111/bdi.12859. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12859

1. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatr. 2009;2(1):29-36.

2. Nunez NA, Singh B, Romo-Nava F, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive modafinil/armodafinil in bipolar depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Bipolar Dipsord. 2019;10.1111/bdi.12859. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12859

During a viral pandemic, anxiety is endemic: The psychiatric aspects of COVID-19

Fear of dying is considered “normal.” However, the ongoing threat of a potentially fatal viral infection can cause panic, anxiety, and an exaggerated fear of illness and death. The relentless spread of the coronavirus infectious disease that began in late 2019 (COVID-19) is spawning widespread anxiety, panic, and worry about one’s health and the health of loved ones. The viral pandemic has triggered a parallel anxiety epidemic.

Making things worse is that no vaccine has yet been developed, and for individuals who do get infected, there are no specific treatments other than supportive care, such as ventilators. Members of the public have been urged to practice sensible preventative measures, including handwashing, sanitizing certain items and surfaces, and—particularly challenging—self-isolation and social distancing. The public has channeled its fear into frantic buying and hoarding of food and non-food items, especially masks, sanitizers, soap, disinfectant wipes, and toilet paper (perhaps preparing for gastrointestinal hyperactivity during anxiety); canceling flights; avoiding group activities; and self-isolation or, for those exposed to the virus, quarantine. Anxiety is palpable. The facial masks that people wear are ironically unmasking their inner agitation and disquietude.

Our role as psychiatrists

As psychiatrists, we have an important role to play in such times, especially for our patients who already have anxiety disorders or depression. The additional emotional burden of this escalating health crisis is exacerbating the mental anguish of our patients (in addition to those who may soon become new patients). The anxiety and panic attacks due to “imagined” doom and gloom are now intensified by anxiety due to a “real” fatal threat. The effect on some vulnerable patients can be devastating, and may culminate in an acute stress reaction and future posttraumatic stress disorder. There are also reports of “psychogenic COVID-19” conversion reaction, with symptoms of sore throat, dyspnea, and even psychogenic fever. Paradoxically, self-isolation and social distancing, which are recommended to prevent the human-to-human spread of the virus, may further worsen anxiety and depression by reducing the comfort of intimacy and social contacts.

Individuals with depression will also experience an increased risk of symptom breakthrough despite receiving treatment. Stress is well known to trigger or exacerbate depression. Thus, the sense of helplessness and hopelessness during depression may intensify among our patients with pre-existing mood disorders, and suicidal ideation may resurface. Making things worse is the unfortunate timing of the COVID-19 pandemic. Spring is the peak season for the re-emergence of depression and suicide attempts. The ongoing stress of the health crisis, coupled with the onset of spring, may coalesce into a dreadful synergy for relapse among vulnerable individuals with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are known to be averse to imagined germs and may wash their hands multiple times a day. An epidemic in which all health officials strongly urge washing one’s hands is very likely to exacerbate the compulsive handwashing of persons with OCD and significantly increase their anxiety. Because their other obsessions and compulsions may also increase in frequency and intensity, they will need our attention as their psychiatrists.

The viral pandemic is eerily similar to a natural disaster such as a hurricane of tornado, both of which physically destroy towns and flatten homes. The COVID-19 pandemic is damaging social structures and obliterating the fabric of global human relations. Consider the previously unimaginable disruption of what makes a vibrant society: schools, colleges, sporting events, concerts, Broadway shows, houses of worship, festivals, conferences, conventions, busy airports/train stations/bus stations, and spontaneous community gatherings. The sudden shock of upheaval in our daily lives may not only cause a hollow sense of emptiness and grief, but also have residual economic and emotional consequences. Nothing can be taken for granted anymore, and nothing is permanent. Cynicism may rise about maintaining life as we know it.

Rising to the challenge

Physicians and clinicians across all specialties are rising to the challenge of the pandemic, whether to manage the immediate physical or emotional impacts of the health crisis or its anticipated consequences (including the economic sequelae). The often-demonized pharmaceutical industry is urgently summoning all its resources to develop both a vaccine as well as biologic treatments for this potentially fatal viral infection. The government is removing regulatory barriers to expedite solutions to the crisis. A welcome public-private partnership is expediting the availability of and access to testing for the virus. The toxic political partisanship has temporarily given way to collaboration in crafting laws that can mitigate the corrosive effects of the health crisis on businesses and individuals. All these salubrious repercussions of the pandemic are heartening and indicative of how a crisis can often bring out the best among us humans.

Continue to: Let's acknowledge the benefits...

Let’s acknowledge the benefits of the internet and the often-maligned social media. At a time of social isolation and cancellation of popular recreational activities (March Madness, NBA games, spring training baseball, movie theaters, concerts, religious congregations, partying with friends), the internet can offset the pain of mandated isolation by connecting all of us virtually, thus alleviating the emptiness that comes with isolation and boredom laced with anxiety. The damaging effects of a viral pandemic on human well-being would have been much worse if the internet did not exist.

Before the internet, television was a major escape, and for many it still is. But there is a downside: the wall-to-wall coverage of the local, national, and international effects of the pandemic can be alarming, and could increase distress even among persons who don’t have an anxiety disorder. Paradoxically, fear of going outdoors (agoraphobia) has suddenly become a necessary coping mechanism during a viral pandemic, instead of its traditional status as a “disabling symptom.”

Thank heavens for advances in technology. School children and college students can continue their education remotely without the risks of spreading infection by going to crowded classrooms. Scientific interactions and collaboration as well as business communications can remain active via videoconferencing technology, such as Zoom, Skype, or WebEx, without having to walk in crowded airports and fly to other cities on planes with recirculated air. Also, individuals who live far from family or friends can use their smartphones to see and chat with their loved ones. And cellphones remain a convenient method of staying in touch with the latest developments or making a “call to action” locally, national, and internationally.

During these oppressive and exceptional times, special attention and support must be provided to vulnerable populations, especially individuals with psychiatric illnesses, older adults who are physically infirm, and young children. Providing medical care, including psychiatric care, is essential to prevent the escalation of anxiety and panic among children and adults alike, and to prevent physical deterioration or death. This health crisis must be tackled with biopsychosocial approaches. And we, psychiatrists, must support and educate our patients and the public about stress management, and remind all about the transiency of epidemics as exemplified by the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957 Asian flu, the 1968 Hong Kong flu, the 1982 human immunodeficiency virus, the 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome virus, the 2009 Swine flu, the 2013 Ebola virus, and the 2016 Zika virus, all of which are now distant memories. The current COVID-19 pandemic should inoculate us to be more prepared and resilient for the inevitable future pandemics.

Fear of dying is considered “normal.” However, the ongoing threat of a potentially fatal viral infection can cause panic, anxiety, and an exaggerated fear of illness and death. The relentless spread of the coronavirus infectious disease that began in late 2019 (COVID-19) is spawning widespread anxiety, panic, and worry about one’s health and the health of loved ones. The viral pandemic has triggered a parallel anxiety epidemic.

Making things worse is that no vaccine has yet been developed, and for individuals who do get infected, there are no specific treatments other than supportive care, such as ventilators. Members of the public have been urged to practice sensible preventative measures, including handwashing, sanitizing certain items and surfaces, and—particularly challenging—self-isolation and social distancing. The public has channeled its fear into frantic buying and hoarding of food and non-food items, especially masks, sanitizers, soap, disinfectant wipes, and toilet paper (perhaps preparing for gastrointestinal hyperactivity during anxiety); canceling flights; avoiding group activities; and self-isolation or, for those exposed to the virus, quarantine. Anxiety is palpable. The facial masks that people wear are ironically unmasking their inner agitation and disquietude.

Our role as psychiatrists

As psychiatrists, we have an important role to play in such times, especially for our patients who already have anxiety disorders or depression. The additional emotional burden of this escalating health crisis is exacerbating the mental anguish of our patients (in addition to those who may soon become new patients). The anxiety and panic attacks due to “imagined” doom and gloom are now intensified by anxiety due to a “real” fatal threat. The effect on some vulnerable patients can be devastating, and may culminate in an acute stress reaction and future posttraumatic stress disorder. There are also reports of “psychogenic COVID-19” conversion reaction, with symptoms of sore throat, dyspnea, and even psychogenic fever. Paradoxically, self-isolation and social distancing, which are recommended to prevent the human-to-human spread of the virus, may further worsen anxiety and depression by reducing the comfort of intimacy and social contacts.

Individuals with depression will also experience an increased risk of symptom breakthrough despite receiving treatment. Stress is well known to trigger or exacerbate depression. Thus, the sense of helplessness and hopelessness during depression may intensify among our patients with pre-existing mood disorders, and suicidal ideation may resurface. Making things worse is the unfortunate timing of the COVID-19 pandemic. Spring is the peak season for the re-emergence of depression and suicide attempts. The ongoing stress of the health crisis, coupled with the onset of spring, may coalesce into a dreadful synergy for relapse among vulnerable individuals with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are known to be averse to imagined germs and may wash their hands multiple times a day. An epidemic in which all health officials strongly urge washing one’s hands is very likely to exacerbate the compulsive handwashing of persons with OCD and significantly increase their anxiety. Because their other obsessions and compulsions may also increase in frequency and intensity, they will need our attention as their psychiatrists.

The viral pandemic is eerily similar to a natural disaster such as a hurricane of tornado, both of which physically destroy towns and flatten homes. The COVID-19 pandemic is damaging social structures and obliterating the fabric of global human relations. Consider the previously unimaginable disruption of what makes a vibrant society: schools, colleges, sporting events, concerts, Broadway shows, houses of worship, festivals, conferences, conventions, busy airports/train stations/bus stations, and spontaneous community gatherings. The sudden shock of upheaval in our daily lives may not only cause a hollow sense of emptiness and grief, but also have residual economic and emotional consequences. Nothing can be taken for granted anymore, and nothing is permanent. Cynicism may rise about maintaining life as we know it.

Rising to the challenge

Physicians and clinicians across all specialties are rising to the challenge of the pandemic, whether to manage the immediate physical or emotional impacts of the health crisis or its anticipated consequences (including the economic sequelae). The often-demonized pharmaceutical industry is urgently summoning all its resources to develop both a vaccine as well as biologic treatments for this potentially fatal viral infection. The government is removing regulatory barriers to expedite solutions to the crisis. A welcome public-private partnership is expediting the availability of and access to testing for the virus. The toxic political partisanship has temporarily given way to collaboration in crafting laws that can mitigate the corrosive effects of the health crisis on businesses and individuals. All these salubrious repercussions of the pandemic are heartening and indicative of how a crisis can often bring out the best among us humans.

Continue to: Let's acknowledge the benefits...

Let’s acknowledge the benefits of the internet and the often-maligned social media. At a time of social isolation and cancellation of popular recreational activities (March Madness, NBA games, spring training baseball, movie theaters, concerts, religious congregations, partying with friends), the internet can offset the pain of mandated isolation by connecting all of us virtually, thus alleviating the emptiness that comes with isolation and boredom laced with anxiety. The damaging effects of a viral pandemic on human well-being would have been much worse if the internet did not exist.

Before the internet, television was a major escape, and for many it still is. But there is a downside: the wall-to-wall coverage of the local, national, and international effects of the pandemic can be alarming, and could increase distress even among persons who don’t have an anxiety disorder. Paradoxically, fear of going outdoors (agoraphobia) has suddenly become a necessary coping mechanism during a viral pandemic, instead of its traditional status as a “disabling symptom.”

Thank heavens for advances in technology. School children and college students can continue their education remotely without the risks of spreading infection by going to crowded classrooms. Scientific interactions and collaboration as well as business communications can remain active via videoconferencing technology, such as Zoom, Skype, or WebEx, without having to walk in crowded airports and fly to other cities on planes with recirculated air. Also, individuals who live far from family or friends can use their smartphones to see and chat with their loved ones. And cellphones remain a convenient method of staying in touch with the latest developments or making a “call to action” locally, national, and internationally.

During these oppressive and exceptional times, special attention and support must be provided to vulnerable populations, especially individuals with psychiatric illnesses, older adults who are physically infirm, and young children. Providing medical care, including psychiatric care, is essential to prevent the escalation of anxiety and panic among children and adults alike, and to prevent physical deterioration or death. This health crisis must be tackled with biopsychosocial approaches. And we, psychiatrists, must support and educate our patients and the public about stress management, and remind all about the transiency of epidemics as exemplified by the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957 Asian flu, the 1968 Hong Kong flu, the 1982 human immunodeficiency virus, the 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome virus, the 2009 Swine flu, the 2013 Ebola virus, and the 2016 Zika virus, all of which are now distant memories. The current COVID-19 pandemic should inoculate us to be more prepared and resilient for the inevitable future pandemics.

Fear of dying is considered “normal.” However, the ongoing threat of a potentially fatal viral infection can cause panic, anxiety, and an exaggerated fear of illness and death. The relentless spread of the coronavirus infectious disease that began in late 2019 (COVID-19) is spawning widespread anxiety, panic, and worry about one’s health and the health of loved ones. The viral pandemic has triggered a parallel anxiety epidemic.

Making things worse is that no vaccine has yet been developed, and for individuals who do get infected, there are no specific treatments other than supportive care, such as ventilators. Members of the public have been urged to practice sensible preventative measures, including handwashing, sanitizing certain items and surfaces, and—particularly challenging—self-isolation and social distancing. The public has channeled its fear into frantic buying and hoarding of food and non-food items, especially masks, sanitizers, soap, disinfectant wipes, and toilet paper (perhaps preparing for gastrointestinal hyperactivity during anxiety); canceling flights; avoiding group activities; and self-isolation or, for those exposed to the virus, quarantine. Anxiety is palpable. The facial masks that people wear are ironically unmasking their inner agitation and disquietude.

Our role as psychiatrists

As psychiatrists, we have an important role to play in such times, especially for our patients who already have anxiety disorders or depression. The additional emotional burden of this escalating health crisis is exacerbating the mental anguish of our patients (in addition to those who may soon become new patients). The anxiety and panic attacks due to “imagined” doom and gloom are now intensified by anxiety due to a “real” fatal threat. The effect on some vulnerable patients can be devastating, and may culminate in an acute stress reaction and future posttraumatic stress disorder. There are also reports of “psychogenic COVID-19” conversion reaction, with symptoms of sore throat, dyspnea, and even psychogenic fever. Paradoxically, self-isolation and social distancing, which are recommended to prevent the human-to-human spread of the virus, may further worsen anxiety and depression by reducing the comfort of intimacy and social contacts.

Individuals with depression will also experience an increased risk of symptom breakthrough despite receiving treatment. Stress is well known to trigger or exacerbate depression. Thus, the sense of helplessness and hopelessness during depression may intensify among our patients with pre-existing mood disorders, and suicidal ideation may resurface. Making things worse is the unfortunate timing of the COVID-19 pandemic. Spring is the peak season for the re-emergence of depression and suicide attempts. The ongoing stress of the health crisis, coupled with the onset of spring, may coalesce into a dreadful synergy for relapse among vulnerable individuals with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are known to be averse to imagined germs and may wash their hands multiple times a day. An epidemic in which all health officials strongly urge washing one’s hands is very likely to exacerbate the compulsive handwashing of persons with OCD and significantly increase their anxiety. Because their other obsessions and compulsions may also increase in frequency and intensity, they will need our attention as their psychiatrists.

The viral pandemic is eerily similar to a natural disaster such as a hurricane of tornado, both of which physically destroy towns and flatten homes. The COVID-19 pandemic is damaging social structures and obliterating the fabric of global human relations. Consider the previously unimaginable disruption of what makes a vibrant society: schools, colleges, sporting events, concerts, Broadway shows, houses of worship, festivals, conferences, conventions, busy airports/train stations/bus stations, and spontaneous community gatherings. The sudden shock of upheaval in our daily lives may not only cause a hollow sense of emptiness and grief, but also have residual economic and emotional consequences. Nothing can be taken for granted anymore, and nothing is permanent. Cynicism may rise about maintaining life as we know it.

Rising to the challenge

Physicians and clinicians across all specialties are rising to the challenge of the pandemic, whether to manage the immediate physical or emotional impacts of the health crisis or its anticipated consequences (including the economic sequelae). The often-demonized pharmaceutical industry is urgently summoning all its resources to develop both a vaccine as well as biologic treatments for this potentially fatal viral infection. The government is removing regulatory barriers to expedite solutions to the crisis. A welcome public-private partnership is expediting the availability of and access to testing for the virus. The toxic political partisanship has temporarily given way to collaboration in crafting laws that can mitigate the corrosive effects of the health crisis on businesses and individuals. All these salubrious repercussions of the pandemic are heartening and indicative of how a crisis can often bring out the best among us humans.

Continue to: Let's acknowledge the benefits...

Let’s acknowledge the benefits of the internet and the often-maligned social media. At a time of social isolation and cancellation of popular recreational activities (March Madness, NBA games, spring training baseball, movie theaters, concerts, religious congregations, partying with friends), the internet can offset the pain of mandated isolation by connecting all of us virtually, thus alleviating the emptiness that comes with isolation and boredom laced with anxiety. The damaging effects of a viral pandemic on human well-being would have been much worse if the internet did not exist.

Before the internet, television was a major escape, and for many it still is. But there is a downside: the wall-to-wall coverage of the local, national, and international effects of the pandemic can be alarming, and could increase distress even among persons who don’t have an anxiety disorder. Paradoxically, fear of going outdoors (agoraphobia) has suddenly become a necessary coping mechanism during a viral pandemic, instead of its traditional status as a “disabling symptom.”

Thank heavens for advances in technology. School children and college students can continue their education remotely without the risks of spreading infection by going to crowded classrooms. Scientific interactions and collaboration as well as business communications can remain active via videoconferencing technology, such as Zoom, Skype, or WebEx, without having to walk in crowded airports and fly to other cities on planes with recirculated air. Also, individuals who live far from family or friends can use their smartphones to see and chat with their loved ones. And cellphones remain a convenient method of staying in touch with the latest developments or making a “call to action” locally, national, and internationally.

During these oppressive and exceptional times, special attention and support must be provided to vulnerable populations, especially individuals with psychiatric illnesses, older adults who are physically infirm, and young children. Providing medical care, including psychiatric care, is essential to prevent the escalation of anxiety and panic among children and adults alike, and to prevent physical deterioration or death. This health crisis must be tackled with biopsychosocial approaches. And we, psychiatrists, must support and educate our patients and the public about stress management, and remind all about the transiency of epidemics as exemplified by the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957 Asian flu, the 1968 Hong Kong flu, the 1982 human immunodeficiency virus, the 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome virus, the 2009 Swine flu, the 2013 Ebola virus, and the 2016 Zika virus, all of which are now distant memories. The current COVID-19 pandemic should inoculate us to be more prepared and resilient for the inevitable future pandemics.

Paradise lost: Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness among psychiatric patients

The United States Declaration of Independence is widely known for the words that begin its second paragraph:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Those basic rights are accessible and exercised by all healthy US citizens, but for many individuals with psychiatric disorders, those inalienable rights may be elusive. Consider how they are compromised by untreated psychiatric illness.

Life. This is the most basic right. In the United States, healthy individuals cherish being alive, and many take it for granted, unlike the residents of nondemocratic countries, where persons may be killed by dictators for political or other reasons (Stalin and Hitler murdered millions of innocent people). In the past, persons with mental illness were considered possessed by demons and were killed or burned at the stake (as in the Middle Ages). But unfortunately, the current major risk for the loss of life among psychiatric patients is the patients themselves. Suicidal urges, attempts, and completions are of epidemic proportions and continue to rise every year. Our patients end their own lives because their illness prompts them to relinquish their life and to embrace untimely death. And once life is lost, all other rights are abdicated. Suicide attempts are common among patients who are diagnosed with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Sometimes, suicide is unintentional, such as when a patient with a substance use disorder inadvertently overdoses (as in the contemporary opioid epidemic) or ingests drugs laced with a deadly substance. For many untreated patients, life can be so fragile, tenuous, and tragically brief.

Liberty. Healthy citizens in the United States (and other democratic countries) have many liberties: where to live, what to do, where to move, what to say, what to believe, who to assemble with, what to eat or drink, whom to befriend, whom to marry, whether or not to procreate, and what to wear. They can choose to be an activist for any cause, no matter how quaint, or to disfigure their bodies with tattoos or piercings.

In contrast, the liberties of individuals with a psychiatric disorder can be compromised. In fact, patients’ liberties can be seriously shackled by their illness. A person with untreated schizophrenia can be enslaved by fixed irrational beliefs that may constrain their choices or determine how they live or relate to others. Command hallucinations can dictate what a patient should or mustn’t do. Poor reality testing detrimentally limits the options of a person with psychosis. A lack of insight deprives a patient with schizophrenia from rational decision-making. Self-neglect leads to physical, mental, and social deterioration.

For persons with depression, the range of liberties is shattered by social withdrawal, overwhelming guilt, sense of worthlessness, dismal hopelessness, doleful ruminations, and loss of appetite or sleep. The only rights that people with depression may exercise is to injure their body or end their life.

Think also of patients with OCD, who are subjugated by their ongoing obsessions or compulsive rituals; think of those with panic disorder who are unable to leave their home due to agoraphobia or

Continue to: Happiness

Happiness. I often wonder if most Americans these days are pursuing pleasure rather than happiness, seeking the momentary thrill and gratification instead of long-lasting happiness and joy. But persons with psychiatric brain disorders have great difficulty pursuing either pleasure or happiness. Anhedonia is a common symptom in schizophrenia and depression, depriving patients from experiencing enjoyable activities (ie, having fun) as they used to do before they got sick. Persons with anxiety have such emotional turmoil, it is hard for them to experience pleasure or happiness when feelings of impending doom permeates their souls. Persons with an addictive disorder are coerced to seek their substance for a momentary reward, only to spend a much longer time craving and seeking their substance of choice again and again. On the other end of the spectrum, for persons with mania, the excessive pursuit of high-risk pleasures can have grave consequences or embarrassment after they recover.

Happiness for patients with mental illness is possible only when they emerge from their illness and are “liberated” from the symptoms that disrupt their lives. As psychiatrists, we don’t just evaluate and treat patients with psychiatric illness—we restore their liberties and ability to pursue happiness and enjoy small pleasures.

The motto on the seal of the American University of Beirut, which I attended in my youth, is “That they may have life, and to have it abundantly.” As I have grown older and wiser, I have come to realize the true meaning of that motto. Life is a right we take for granted, but without it, we cannot exercise the various liberties, or be able to pursue happiness. I exercised my right to become a psychiatrist, and that provided me with lifelong happiness and satisfaction, especially when I prevent the loss of life of my patients, restore their liberty by ridding them of illness, and resurrect their ability to experience pleasure and pursue happiness.

The United States Declaration of Independence is widely known for the words that begin its second paragraph:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Those basic rights are accessible and exercised by all healthy US citizens, but for many individuals with psychiatric disorders, those inalienable rights may be elusive. Consider how they are compromised by untreated psychiatric illness.

Life. This is the most basic right. In the United States, healthy individuals cherish being alive, and many take it for granted, unlike the residents of nondemocratic countries, where persons may be killed by dictators for political or other reasons (Stalin and Hitler murdered millions of innocent people). In the past, persons with mental illness were considered possessed by demons and were killed or burned at the stake (as in the Middle Ages). But unfortunately, the current major risk for the loss of life among psychiatric patients is the patients themselves. Suicidal urges, attempts, and completions are of epidemic proportions and continue to rise every year. Our patients end their own lives because their illness prompts them to relinquish their life and to embrace untimely death. And once life is lost, all other rights are abdicated. Suicide attempts are common among patients who are diagnosed with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Sometimes, suicide is unintentional, such as when a patient with a substance use disorder inadvertently overdoses (as in the contemporary opioid epidemic) or ingests drugs laced with a deadly substance. For many untreated patients, life can be so fragile, tenuous, and tragically brief.

Liberty. Healthy citizens in the United States (and other democratic countries) have many liberties: where to live, what to do, where to move, what to say, what to believe, who to assemble with, what to eat or drink, whom to befriend, whom to marry, whether or not to procreate, and what to wear. They can choose to be an activist for any cause, no matter how quaint, or to disfigure their bodies with tattoos or piercings.

In contrast, the liberties of individuals with a psychiatric disorder can be compromised. In fact, patients’ liberties can be seriously shackled by their illness. A person with untreated schizophrenia can be enslaved by fixed irrational beliefs that may constrain their choices or determine how they live or relate to others. Command hallucinations can dictate what a patient should or mustn’t do. Poor reality testing detrimentally limits the options of a person with psychosis. A lack of insight deprives a patient with schizophrenia from rational decision-making. Self-neglect leads to physical, mental, and social deterioration.

For persons with depression, the range of liberties is shattered by social withdrawal, overwhelming guilt, sense of worthlessness, dismal hopelessness, doleful ruminations, and loss of appetite or sleep. The only rights that people with depression may exercise is to injure their body or end their life.

Think also of patients with OCD, who are subjugated by their ongoing obsessions or compulsive rituals; think of those with panic disorder who are unable to leave their home due to agoraphobia or

Continue to: Happiness

Happiness. I often wonder if most Americans these days are pursuing pleasure rather than happiness, seeking the momentary thrill and gratification instead of long-lasting happiness and joy. But persons with psychiatric brain disorders have great difficulty pursuing either pleasure or happiness. Anhedonia is a common symptom in schizophrenia and depression, depriving patients from experiencing enjoyable activities (ie, having fun) as they used to do before they got sick. Persons with anxiety have such emotional turmoil, it is hard for them to experience pleasure or happiness when feelings of impending doom permeates their souls. Persons with an addictive disorder are coerced to seek their substance for a momentary reward, only to spend a much longer time craving and seeking their substance of choice again and again. On the other end of the spectrum, for persons with mania, the excessive pursuit of high-risk pleasures can have grave consequences or embarrassment after they recover.

Happiness for patients with mental illness is possible only when they emerge from their illness and are “liberated” from the symptoms that disrupt their lives. As psychiatrists, we don’t just evaluate and treat patients with psychiatric illness—we restore their liberties and ability to pursue happiness and enjoy small pleasures.

The motto on the seal of the American University of Beirut, which I attended in my youth, is “That they may have life, and to have it abundantly.” As I have grown older and wiser, I have come to realize the true meaning of that motto. Life is a right we take for granted, but without it, we cannot exercise the various liberties, or be able to pursue happiness. I exercised my right to become a psychiatrist, and that provided me with lifelong happiness and satisfaction, especially when I prevent the loss of life of my patients, restore their liberty by ridding them of illness, and resurrect their ability to experience pleasure and pursue happiness.

The United States Declaration of Independence is widely known for the words that begin its second paragraph:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Those basic rights are accessible and exercised by all healthy US citizens, but for many individuals with psychiatric disorders, those inalienable rights may be elusive. Consider how they are compromised by untreated psychiatric illness.

Life. This is the most basic right. In the United States, healthy individuals cherish being alive, and many take it for granted, unlike the residents of nondemocratic countries, where persons may be killed by dictators for political or other reasons (Stalin and Hitler murdered millions of innocent people). In the past, persons with mental illness were considered possessed by demons and were killed or burned at the stake (as in the Middle Ages). But unfortunately, the current major risk for the loss of life among psychiatric patients is the patients themselves. Suicidal urges, attempts, and completions are of epidemic proportions and continue to rise every year. Our patients end their own lives because their illness prompts them to relinquish their life and to embrace untimely death. And once life is lost, all other rights are abdicated. Suicide attempts are common among patients who are diagnosed with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Sometimes, suicide is unintentional, such as when a patient with a substance use disorder inadvertently overdoses (as in the contemporary opioid epidemic) or ingests drugs laced with a deadly substance. For many untreated patients, life can be so fragile, tenuous, and tragically brief.

Liberty. Healthy citizens in the United States (and other democratic countries) have many liberties: where to live, what to do, where to move, what to say, what to believe, who to assemble with, what to eat or drink, whom to befriend, whom to marry, whether or not to procreate, and what to wear. They can choose to be an activist for any cause, no matter how quaint, or to disfigure their bodies with tattoos or piercings.

In contrast, the liberties of individuals with a psychiatric disorder can be compromised. In fact, patients’ liberties can be seriously shackled by their illness. A person with untreated schizophrenia can be enslaved by fixed irrational beliefs that may constrain their choices or determine how they live or relate to others. Command hallucinations can dictate what a patient should or mustn’t do. Poor reality testing detrimentally limits the options of a person with psychosis. A lack of insight deprives a patient with schizophrenia from rational decision-making. Self-neglect leads to physical, mental, and social deterioration.

For persons with depression, the range of liberties is shattered by social withdrawal, overwhelming guilt, sense of worthlessness, dismal hopelessness, doleful ruminations, and loss of appetite or sleep. The only rights that people with depression may exercise is to injure their body or end their life.

Think also of patients with OCD, who are subjugated by their ongoing obsessions or compulsive rituals; think of those with panic disorder who are unable to leave their home due to agoraphobia or

Continue to: Happiness

Happiness. I often wonder if most Americans these days are pursuing pleasure rather than happiness, seeking the momentary thrill and gratification instead of long-lasting happiness and joy. But persons with psychiatric brain disorders have great difficulty pursuing either pleasure or happiness. Anhedonia is a common symptom in schizophrenia and depression, depriving patients from experiencing enjoyable activities (ie, having fun) as they used to do before they got sick. Persons with anxiety have such emotional turmoil, it is hard for them to experience pleasure or happiness when feelings of impending doom permeates their souls. Persons with an addictive disorder are coerced to seek their substance for a momentary reward, only to spend a much longer time craving and seeking their substance of choice again and again. On the other end of the spectrum, for persons with mania, the excessive pursuit of high-risk pleasures can have grave consequences or embarrassment after they recover.

Happiness for patients with mental illness is possible only when they emerge from their illness and are “liberated” from the symptoms that disrupt their lives. As psychiatrists, we don’t just evaluate and treat patients with psychiatric illness—we restore their liberties and ability to pursue happiness and enjoy small pleasures.

The motto on the seal of the American University of Beirut, which I attended in my youth, is “That they may have life, and to have it abundantly.” As I have grown older and wiser, I have come to realize the true meaning of that motto. Life is a right we take for granted, but without it, we cannot exercise the various liberties, or be able to pursue happiness. I exercised my right to become a psychiatrist, and that provided me with lifelong happiness and satisfaction, especially when I prevent the loss of life of my patients, restore their liberty by ridding them of illness, and resurrect their ability to experience pleasure and pursue happiness.

We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients!

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.

Our unique professional identify is at stake. We do not want to be lumped with nonphysicians as if we are interchangeable parts of a health care system or cogs in a wheel. No other mental health professional has the extensive training, scientific knowledge, clinical expertise, research accomplishments, and teaching/supervisory abilities that physicians have. We strongly uphold the sacred tenet of the physician-patient relationship, and adamantly reject its corruption into a provider-consumer transaction.

Even plumbers and electricians are not referred to as “providers.” Lawyers are not called legal aid providers. Teachers are not called knowledge providers, and administrators and CEOs are not called management providers. So why should physicians in any specialty, including psychiatry, obsequiously accept the denigration of their esteemed medical identify into the vague, amorphous ipseity of a “provider”? Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians used to be called primary care physicians, but have been reduced to primary care providers, which is insulting and degrading to these highly trained MD specialists.

The corruption and debasement of the professional identify of physicians and the propagation of the usage of the belittling term “provider” can be traced back to 3 entities:

1. The Nazi Third Reich. This is the most evil origin of the term “provider,” inflicted on Jewish physicians as part of the despicable persecution of German Jews in the 1930s. The Nazis decided to deprive pediatricians of being called physicians (“Arzt” in German) and forcefully relabeled them as “behandlers” or “providers,” thus erasing their noble medical identity.1 In 1933, all Jewish pediatricians were expelled or forced to resign from the German Society of Pediatrics and were no longer allowed to be called doctors. This deliberate and systematic humiliation of pediatric clinicians and scientists was followed by deporting the lowly “providers” to concentration camps. So why perpetuate this pernicious Nazi terminology?

2. The Federal Government. The term “provider” was introduced and propagated in Public Law 93-641 titled “The National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974.” In that document, patients were referred to as “consumers” and physicians as “providers” (this term was used 19 times in that law). At that time, the civil service employees who drafted the law that marginalized physicians by using generic, nonmedical nomenclature may not have realized the dire consequences of relabeling physicians as “providers.”

Continue to: Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems...

3. Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems have jubilantly adopted the term “provider” because they can equate physicians with less expensive, nonphysician clinicians (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists), especially when physicians across several specialties (particularly psychiatry) are in short supply. None of these clinicians deserve to be labeled “providers,” either.

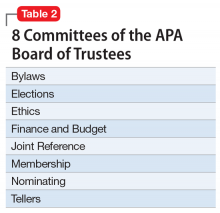

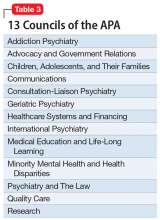

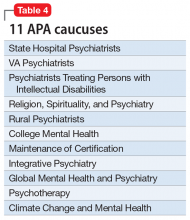

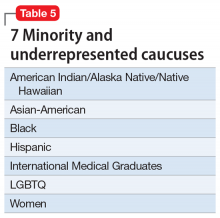

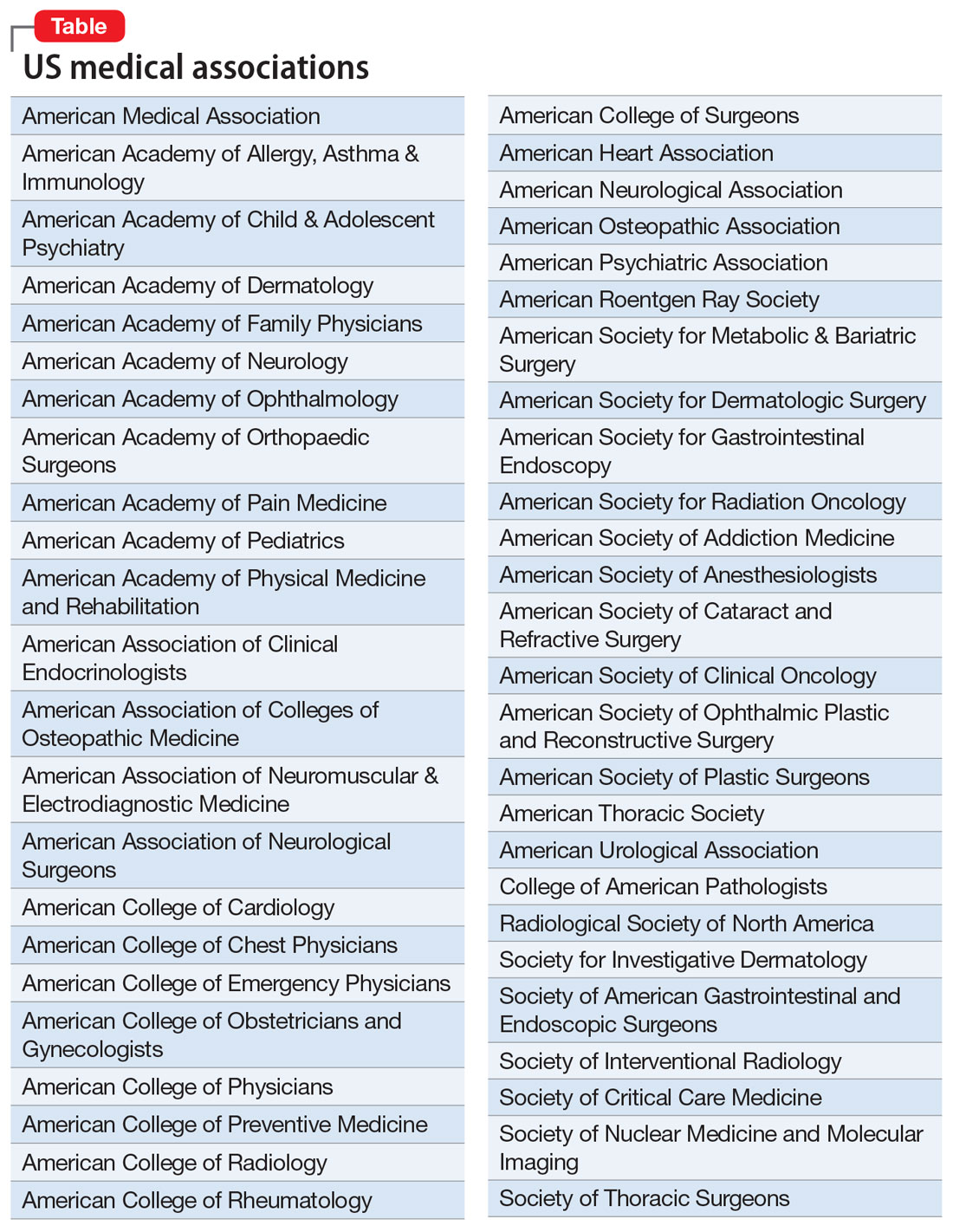

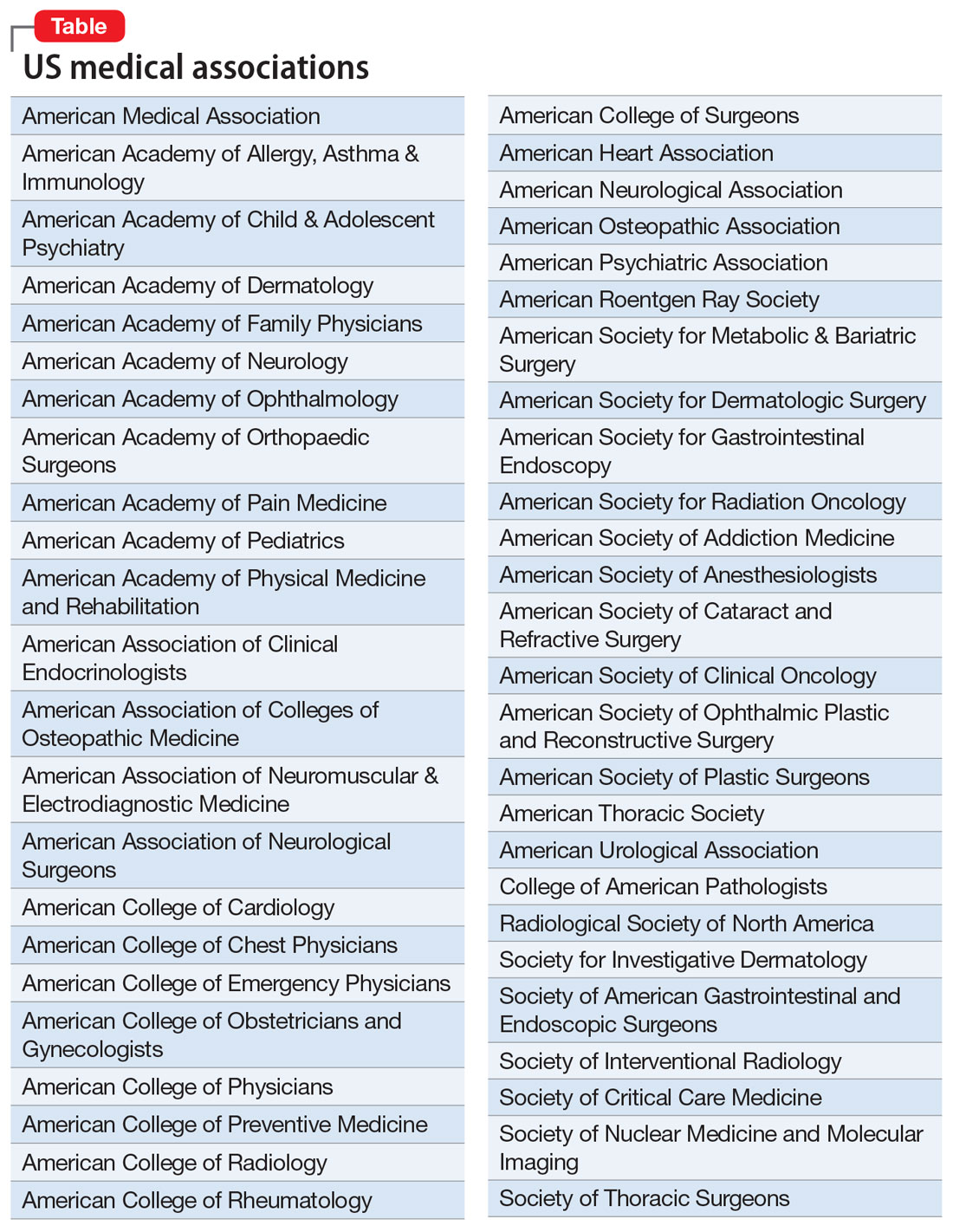

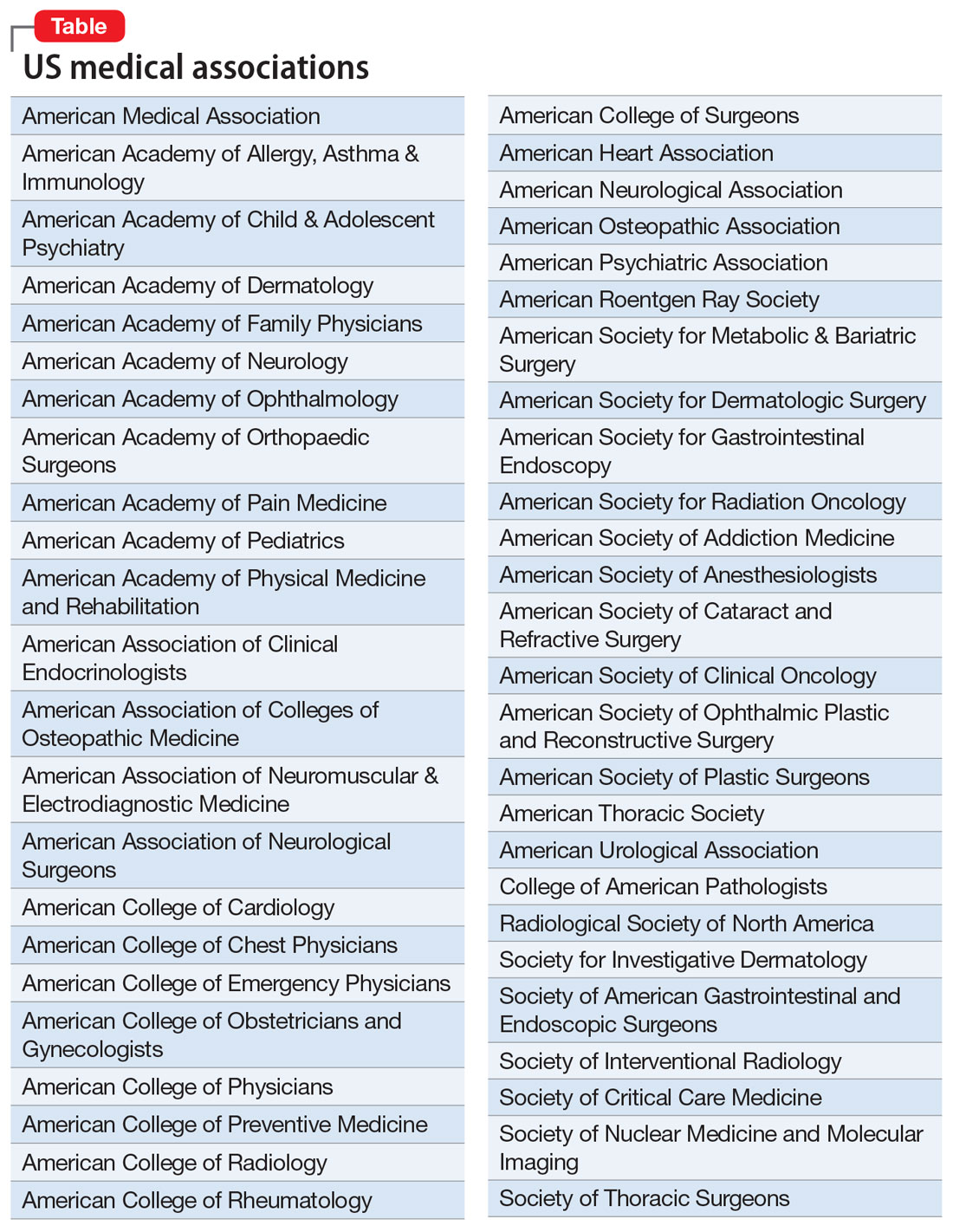

To understand why the term “provider” was used instead of “clinicians” or “clinical practitioner,” one must recognize the “businessification” of medicine and the commoditization of clinical care in our country. In some ways, health care has adopted a model similar to a fast-food joint, where workers provide customers with a hamburger. The question here is why did the 1.1 million physicians in the United States not halt this terminology shift before it spread and permeated the national health care system? Physicians who graduate from medical schools (not “provider” schools!) must vigorously and loudly fight back and put this wicked genie back in its bottle. This is feasible only if the American Medical Association (which would never conceive of itself as the “American Provider Association”), along with all 48 specialty organizations (Table), including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), unite and demand that physicians be called medical doctors or physicians, or by a term that reflects their specialty (orthopedists, psychiatrists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, etc.). This is an urgent issue to prevent the dissolution of our professional identity and its highly regarded societal image. It is a travesty that we physicians have allowed it to go on unopposed and to become entrenched in the dumbed-down jargon of health care. Physicians tend to avoid confrontation and adversarial stances, but we must unite and demand a return to the traditional nomenclature of medicine.

Much debate has emerged lately about an epidemic of “burnout” among physicians. Proposed causes include the savage increase in the amount of paperwork at the expense of patient care, the sense of helplessness that pre-authorization has inflicted on physicians’ decision-making, and the tyranny of relative value units (RVUs) as a benchmark for physician performance, as if healing patients is like manufacturing widgets. However, the blow to the self-esteem of physicians by being called “providers” daily is certainly another major factor contributing to burnout. It is perfectly legitimate for physicians to expect recognition for their long, rigorous, and uniquely advanced medical training, instead of being lumped together with less qualified professionals as anonymous “providers” in the name of politically correct pseudo-equality of all clinical practitioners. Let the administrators stop and contemplate whether tertiary or quaternary care for the most complex and severely ill patients in medical, surgical, or psychiatric intensive care units can operate without highly specialized physicians.

I urge APA leadership to take a visible and strong stand to rid psychiatrists of this assault on our medical identity. As I mentioned in my January 2020 editorial,2 it is vital that the name of our national psychiatric organization (APA) be modified to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, to remind all health care systems, as well as patients, the public, and the media, of our medical identity as physicians before we specialized in psychiatry.

Continue to: Patients, not clients

Patients, not clients

We should also emphasize that our suffering and medically ill patients with serious neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder are patients, not clients. The terminology used in community mental health centers around the country almost universally includes “providers” and “clients.” This de-medicalization of psychiatrists and our patients must be corrected and reversed so that the public understands that treating mental illness is not a business transaction between a “provider” and a “client.” Using the correct terminology may help generate sympathy and compassion towards patients with serious psychiatric illnesses, just as it does for patients with cancer, heart disease, or stroke. The term “client” will never evoke the public sympathy and support that our patients truly deserve.

Let’s keep this issue alive and translate our demands into actions, both locally and nationally. Psychiatrists and physicians of all other specialties must stand up for their rights and inform their systems of care that they must be called by their legitimate and lawful name: physicians or medical doctors (never “providers”). This is an issue that unites all 1.1 million of us. The US health care system would collapse without us, and asking that we be called exactly what our medical license displays is our right and our professional identity.

1. Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of persecution. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(5):324-328.

2. Nasrallah HA. 20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.