User login

HIV prevention enters a new era

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates 40,000 new HIV infections occur annually in the US, and this may be increasing. Close to 1 million people in this country are living with HIV, and an estimated one quarter of them do not know they are infected.1 Thus, the infection often is detected late; 40% of those infected find out about it <1 year before AIDS develops. The result of delayed detection, or failed detection, is a large group of infected persons who unknowingly expose others to the disease for a prolonged period.2

Alarming trends

Recent epidemiologic trends indicate our preventive efforts are inadequate. Risky behavior is increasing among certain subpopulations of men who have sex with men.3,4 In the US, 300 babies a year are born with HIV infection, despite effective interventions to prevent mother-to-baby transmission, largely because infection in the mother is not detected during pregnancy.1 Needle exchange for IV drug users, a proven effective intervention, remains underused because of political objections.5

While the HIV epidemic in the US remains driven by infections in men who have sex with men and those who use illicit intravenous drugs, the number of heterosexually transmitted infections has increased each year and was estimated at 9183 new infections in 2002; 3234 among men and 5949 among women. In addition, the disease has become a major cause of health disparity in this country. Comparative AIDS rates per 100,000 in 2002 were 5.9 for whites, 8.5 for American Indians/Native Americans, 19.2 for Hispanics and 58.7 for African Americans.6

Effective treatments warrant more effective detection

On the other hand, the use of highly active anti-retroviral therapy has been very successful in altering the course of the disease in those infected, lowering death rates dramatically. The result has been an increasing number of people living with HIV/AIDS. While treatment lowers viral loads and presumably makes one less infectious, the overall community effect of an increasing number of infected persons still able to transmit the virus to others could be negative unless education is effective in reducing behavior that places others at risk.

Change is needed

All of these trends have created a need to reexamine HIV prevention efforts. The main HIV prevention interventions used in the US for 2 decades have included screening donated blood; screening pregnant women and administering antiretroviral agents to HIV-positive mothers during pregnancy and to their newborns; needle exchange programs (in a few locations); community-wide and risk-group specific education; and confidential or anonymous HIV counseling and testing programs.

Counseling and testing programs have used extensive pretest and posttest counseling sessions in an attempt to keep those who are HIV negative from contracting the disease. However, studies have shown that counseling and testing do not significantly alter sexual behavior among those who are HIV negative; they are effective for those who are HIV positive.7-11 Counseling of those who are HIV negative can be more effective if patient centered methods are used.12

CDC’S new initiative

The CDC has recently reviewed its HIV prevention efforts and initiated a new campaign called Advancing HIV Prevention (AHP). This initiative has 4 components:

- Make HIV testing a routine part of medical care whenever and wherever patients go for care.

- Use new models for diagnosing HIV infections outside traditional medical settings.

- Prevent new infections by working with people diagnosed with HIV and their partners.

- Decrease mother-to-child HIV transmission.

Potential benefits of increased testing include earlier detection and entry of infected persons into treatment, earlier notification and testing of contacts, shorter periods during which infected persons unknowingly transmit the infection to others, and reduced stigma of testing as it becomes routine. However, this strategy will be effective only if those who are HIV positive can receive medical care and social support and be convinced to avoid exposing others. Fortunately, the evidence is good that intensive counseling and case management can achieve these goals.8-11 Another potential benefit is earlier notification of contacts, either by the patient or the public health department, depending on local public health practice.

Testing during pregnancy is well accepted and widely used but is still not universally implemented. Voluntary testing is more acceptable if implemented as a routine test with a choice to opt out—ie, informing women that the HIV test is being offered as part of routine testing and that they have the option of refusing it. Selective testing based on perceived risk misses cases and contributes to stigmatization of those tested.13 The CDC recommends that women who refuse testing should be counseled on the potential benefits of HIV testing to them and to their babies; and that providers should recommend the test while, preserving the mother’s right to refuse should she decide the test is not in her best interest.14

Family physician involvement

Family physicians can contribute to the country’s HIV prevention efforts by implementing the steps listed in the Table. This new approach places more emphasis on finding those infected with HIV and initiating actions beneficial to them and their partners while reducing risk of transmission.

Explore acceptability of needle exchange programs. Another intervention proven effective, but more controversial, is needle exchange programs for illicit drug users. The evidence to date is that needle exchange programs prevent transmission of HIV and other blood borne pathogens and do not encourage use of illicit drugs.5 Because these programs have proven as controversial as they are effective, they have not been widely adopted. If the community political climate is receptive, family physicians could also advocate for these programs.

Implement routine testing. As family physicians move to make HIV testing routine, several issues must be considered. Though HIV testing methods are quite accurate, an initial positive test in a person with a very low pretest probability is more likely to be a false positive than a true positive. Risks, however, are not always apparent or admitted to by patients. Positive tests should be repeated and confirmed. Newly approved rapid HIV tests allow for results within a half-hour, but positive test results must be confirmed by western blot or immunofluorescence assay.15

Report cases promptly. In 31 states, HIV infection is a reportable disease. This may cause concern among patients and lead physicians to under report. This practice is discouraged for several reasons. Accurate tracking of the HIV epidemic is critical to measure the effectiveness of preventive interventions and to enable quick implementation of needed changes in public health practice. Federal funds to support treatment for those with HIV/AIDS depend on the number of persons with documented HIV infection; under-reporting causes the community to lose treatment funds. Finally, public health departments have a long established record of maintaining confidentiality of infectious disease reports and, in most jurisdictions, have more confidentiality legal protections than do physician offices.

HIV remains a significant public health problem in the US. As the epidemic evolves, new public health efforts will be needed. Full control of the epidemic might not be achieved until a more effective intervention, such as a vaccine, is available. However, interventions have proven effective and more widespread use would reduce the community burden of the disease.

TABLE

Practice based initiatives that could contribute to HIV reduction in the community

| Make HIV testing a routine part of general medical care. |

| Make HIV testing a routine part of pregnancy care. Test as early as possible in pregnancy and retest those at high risk in the third trimester. |

| Refer those who are HIV-positive to the local public health department for case management. |

| Work collaboratively with the public health department to insure that people with HIV infection receive medical care and social services. |

| Reinforce the message to those infected about how to avoid transmitting the infection to others. |

| Counsel uninfected patients who practice high-risk behaviors about how to reduce their risks of infection, using patient centered methods. |

| Promptly diagnose and treat other sexually transmitted infections. |

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention. Advancing HIV prevention: the science behind the new initiative. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/partners/ahp_science.htm.

2. Hays RB, Paul J, Ekstrand M, Kegeles SM, et al. Actual versus perceived HIV status, sexual behaviors and predictors of unprotected sex among young gay and bisexual men who identify as HIV-negative, HIV-positive and untested. AIDS 1997;11:1495-1502.

3. CDC. Primary and secondary syphilis among men who have sex with men – New York City, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:853-856.

4. CDC. Resurgent bacterial sexually transmitted disease among men who have sex with men—King County, Washington, 1997–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:773-777.

5. Institute of Medicine No Time to Lose: Getting More from HIV Prevention. Committee on HIV Prevention Strategies in the United States, Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

6. CDC. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States, 2002. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2002;14:1-58.Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasr1402.htm.

7. Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. efficacy of risk reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1161-1167.

8. Wenger NS, Kussling FS, Beck K, Shapiro MF. Sexual behavior of individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: The need for intervention. Arch Int Med 1994;154:1849-1854.

9. Kilmarx PH, Hamers FF, Peterman TA. Living with HIV. Experiences and perspectives of HIV-infected sexually transmitted disease clinic patients after posttest counseling. Sex Transm Dis 1998;25:28-37.

10. Higgins DL, Galavotti C, O’Reilly KE, et al. Evidence for the effects of HIV antibody counseling and testing on risk behaviors. JAMA 1991;266:2419-2429

11. Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1397-1405.

12. Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA 1998;280:1161-1167.

13. Walensky RP, Losina E, Steger-Craven KA, Freedberg KA. Identifying undiagnosed human immunodeficiency virus: the yield of routine, voluntary inpatient testing. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:887-892.

14. CDC. Revised recommendations for HIV screening of pregnant women. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50(RR-19):59-86.

15. CDC. Notice to readers: Approval of a new rapid test for HIV antibody. MMWR Morn Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:1051-1052.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates 40,000 new HIV infections occur annually in the US, and this may be increasing. Close to 1 million people in this country are living with HIV, and an estimated one quarter of them do not know they are infected.1 Thus, the infection often is detected late; 40% of those infected find out about it <1 year before AIDS develops. The result of delayed detection, or failed detection, is a large group of infected persons who unknowingly expose others to the disease for a prolonged period.2

Alarming trends

Recent epidemiologic trends indicate our preventive efforts are inadequate. Risky behavior is increasing among certain subpopulations of men who have sex with men.3,4 In the US, 300 babies a year are born with HIV infection, despite effective interventions to prevent mother-to-baby transmission, largely because infection in the mother is not detected during pregnancy.1 Needle exchange for IV drug users, a proven effective intervention, remains underused because of political objections.5

While the HIV epidemic in the US remains driven by infections in men who have sex with men and those who use illicit intravenous drugs, the number of heterosexually transmitted infections has increased each year and was estimated at 9183 new infections in 2002; 3234 among men and 5949 among women. In addition, the disease has become a major cause of health disparity in this country. Comparative AIDS rates per 100,000 in 2002 were 5.9 for whites, 8.5 for American Indians/Native Americans, 19.2 for Hispanics and 58.7 for African Americans.6

Effective treatments warrant more effective detection

On the other hand, the use of highly active anti-retroviral therapy has been very successful in altering the course of the disease in those infected, lowering death rates dramatically. The result has been an increasing number of people living with HIV/AIDS. While treatment lowers viral loads and presumably makes one less infectious, the overall community effect of an increasing number of infected persons still able to transmit the virus to others could be negative unless education is effective in reducing behavior that places others at risk.

Change is needed

All of these trends have created a need to reexamine HIV prevention efforts. The main HIV prevention interventions used in the US for 2 decades have included screening donated blood; screening pregnant women and administering antiretroviral agents to HIV-positive mothers during pregnancy and to their newborns; needle exchange programs (in a few locations); community-wide and risk-group specific education; and confidential or anonymous HIV counseling and testing programs.

Counseling and testing programs have used extensive pretest and posttest counseling sessions in an attempt to keep those who are HIV negative from contracting the disease. However, studies have shown that counseling and testing do not significantly alter sexual behavior among those who are HIV negative; they are effective for those who are HIV positive.7-11 Counseling of those who are HIV negative can be more effective if patient centered methods are used.12

CDC’S new initiative

The CDC has recently reviewed its HIV prevention efforts and initiated a new campaign called Advancing HIV Prevention (AHP). This initiative has 4 components:

- Make HIV testing a routine part of medical care whenever and wherever patients go for care.

- Use new models for diagnosing HIV infections outside traditional medical settings.

- Prevent new infections by working with people diagnosed with HIV and their partners.

- Decrease mother-to-child HIV transmission.

Potential benefits of increased testing include earlier detection and entry of infected persons into treatment, earlier notification and testing of contacts, shorter periods during which infected persons unknowingly transmit the infection to others, and reduced stigma of testing as it becomes routine. However, this strategy will be effective only if those who are HIV positive can receive medical care and social support and be convinced to avoid exposing others. Fortunately, the evidence is good that intensive counseling and case management can achieve these goals.8-11 Another potential benefit is earlier notification of contacts, either by the patient or the public health department, depending on local public health practice.

Testing during pregnancy is well accepted and widely used but is still not universally implemented. Voluntary testing is more acceptable if implemented as a routine test with a choice to opt out—ie, informing women that the HIV test is being offered as part of routine testing and that they have the option of refusing it. Selective testing based on perceived risk misses cases and contributes to stigmatization of those tested.13 The CDC recommends that women who refuse testing should be counseled on the potential benefits of HIV testing to them and to their babies; and that providers should recommend the test while, preserving the mother’s right to refuse should she decide the test is not in her best interest.14

Family physician involvement

Family physicians can contribute to the country’s HIV prevention efforts by implementing the steps listed in the Table. This new approach places more emphasis on finding those infected with HIV and initiating actions beneficial to them and their partners while reducing risk of transmission.

Explore acceptability of needle exchange programs. Another intervention proven effective, but more controversial, is needle exchange programs for illicit drug users. The evidence to date is that needle exchange programs prevent transmission of HIV and other blood borne pathogens and do not encourage use of illicit drugs.5 Because these programs have proven as controversial as they are effective, they have not been widely adopted. If the community political climate is receptive, family physicians could also advocate for these programs.

Implement routine testing. As family physicians move to make HIV testing routine, several issues must be considered. Though HIV testing methods are quite accurate, an initial positive test in a person with a very low pretest probability is more likely to be a false positive than a true positive. Risks, however, are not always apparent or admitted to by patients. Positive tests should be repeated and confirmed. Newly approved rapid HIV tests allow for results within a half-hour, but positive test results must be confirmed by western blot or immunofluorescence assay.15

Report cases promptly. In 31 states, HIV infection is a reportable disease. This may cause concern among patients and lead physicians to under report. This practice is discouraged for several reasons. Accurate tracking of the HIV epidemic is critical to measure the effectiveness of preventive interventions and to enable quick implementation of needed changes in public health practice. Federal funds to support treatment for those with HIV/AIDS depend on the number of persons with documented HIV infection; under-reporting causes the community to lose treatment funds. Finally, public health departments have a long established record of maintaining confidentiality of infectious disease reports and, in most jurisdictions, have more confidentiality legal protections than do physician offices.

HIV remains a significant public health problem in the US. As the epidemic evolves, new public health efforts will be needed. Full control of the epidemic might not be achieved until a more effective intervention, such as a vaccine, is available. However, interventions have proven effective and more widespread use would reduce the community burden of the disease.

TABLE

Practice based initiatives that could contribute to HIV reduction in the community

| Make HIV testing a routine part of general medical care. |

| Make HIV testing a routine part of pregnancy care. Test as early as possible in pregnancy and retest those at high risk in the third trimester. |

| Refer those who are HIV-positive to the local public health department for case management. |

| Work collaboratively with the public health department to insure that people with HIV infection receive medical care and social services. |

| Reinforce the message to those infected about how to avoid transmitting the infection to others. |

| Counsel uninfected patients who practice high-risk behaviors about how to reduce their risks of infection, using patient centered methods. |

| Promptly diagnose and treat other sexually transmitted infections. |

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: [email protected].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates 40,000 new HIV infections occur annually in the US, and this may be increasing. Close to 1 million people in this country are living with HIV, and an estimated one quarter of them do not know they are infected.1 Thus, the infection often is detected late; 40% of those infected find out about it <1 year before AIDS develops. The result of delayed detection, or failed detection, is a large group of infected persons who unknowingly expose others to the disease for a prolonged period.2

Alarming trends

Recent epidemiologic trends indicate our preventive efforts are inadequate. Risky behavior is increasing among certain subpopulations of men who have sex with men.3,4 In the US, 300 babies a year are born with HIV infection, despite effective interventions to prevent mother-to-baby transmission, largely because infection in the mother is not detected during pregnancy.1 Needle exchange for IV drug users, a proven effective intervention, remains underused because of political objections.5

While the HIV epidemic in the US remains driven by infections in men who have sex with men and those who use illicit intravenous drugs, the number of heterosexually transmitted infections has increased each year and was estimated at 9183 new infections in 2002; 3234 among men and 5949 among women. In addition, the disease has become a major cause of health disparity in this country. Comparative AIDS rates per 100,000 in 2002 were 5.9 for whites, 8.5 for American Indians/Native Americans, 19.2 for Hispanics and 58.7 for African Americans.6

Effective treatments warrant more effective detection

On the other hand, the use of highly active anti-retroviral therapy has been very successful in altering the course of the disease in those infected, lowering death rates dramatically. The result has been an increasing number of people living with HIV/AIDS. While treatment lowers viral loads and presumably makes one less infectious, the overall community effect of an increasing number of infected persons still able to transmit the virus to others could be negative unless education is effective in reducing behavior that places others at risk.

Change is needed

All of these trends have created a need to reexamine HIV prevention efforts. The main HIV prevention interventions used in the US for 2 decades have included screening donated blood; screening pregnant women and administering antiretroviral agents to HIV-positive mothers during pregnancy and to their newborns; needle exchange programs (in a few locations); community-wide and risk-group specific education; and confidential or anonymous HIV counseling and testing programs.

Counseling and testing programs have used extensive pretest and posttest counseling sessions in an attempt to keep those who are HIV negative from contracting the disease. However, studies have shown that counseling and testing do not significantly alter sexual behavior among those who are HIV negative; they are effective for those who are HIV positive.7-11 Counseling of those who are HIV negative can be more effective if patient centered methods are used.12

CDC’S new initiative

The CDC has recently reviewed its HIV prevention efforts and initiated a new campaign called Advancing HIV Prevention (AHP). This initiative has 4 components:

- Make HIV testing a routine part of medical care whenever and wherever patients go for care.

- Use new models for diagnosing HIV infections outside traditional medical settings.

- Prevent new infections by working with people diagnosed with HIV and their partners.

- Decrease mother-to-child HIV transmission.

Potential benefits of increased testing include earlier detection and entry of infected persons into treatment, earlier notification and testing of contacts, shorter periods during which infected persons unknowingly transmit the infection to others, and reduced stigma of testing as it becomes routine. However, this strategy will be effective only if those who are HIV positive can receive medical care and social support and be convinced to avoid exposing others. Fortunately, the evidence is good that intensive counseling and case management can achieve these goals.8-11 Another potential benefit is earlier notification of contacts, either by the patient or the public health department, depending on local public health practice.

Testing during pregnancy is well accepted and widely used but is still not universally implemented. Voluntary testing is more acceptable if implemented as a routine test with a choice to opt out—ie, informing women that the HIV test is being offered as part of routine testing and that they have the option of refusing it. Selective testing based on perceived risk misses cases and contributes to stigmatization of those tested.13 The CDC recommends that women who refuse testing should be counseled on the potential benefits of HIV testing to them and to their babies; and that providers should recommend the test while, preserving the mother’s right to refuse should she decide the test is not in her best interest.14

Family physician involvement

Family physicians can contribute to the country’s HIV prevention efforts by implementing the steps listed in the Table. This new approach places more emphasis on finding those infected with HIV and initiating actions beneficial to them and their partners while reducing risk of transmission.

Explore acceptability of needle exchange programs. Another intervention proven effective, but more controversial, is needle exchange programs for illicit drug users. The evidence to date is that needle exchange programs prevent transmission of HIV and other blood borne pathogens and do not encourage use of illicit drugs.5 Because these programs have proven as controversial as they are effective, they have not been widely adopted. If the community political climate is receptive, family physicians could also advocate for these programs.

Implement routine testing. As family physicians move to make HIV testing routine, several issues must be considered. Though HIV testing methods are quite accurate, an initial positive test in a person with a very low pretest probability is more likely to be a false positive than a true positive. Risks, however, are not always apparent or admitted to by patients. Positive tests should be repeated and confirmed. Newly approved rapid HIV tests allow for results within a half-hour, but positive test results must be confirmed by western blot or immunofluorescence assay.15

Report cases promptly. In 31 states, HIV infection is a reportable disease. This may cause concern among patients and lead physicians to under report. This practice is discouraged for several reasons. Accurate tracking of the HIV epidemic is critical to measure the effectiveness of preventive interventions and to enable quick implementation of needed changes in public health practice. Federal funds to support treatment for those with HIV/AIDS depend on the number of persons with documented HIV infection; under-reporting causes the community to lose treatment funds. Finally, public health departments have a long established record of maintaining confidentiality of infectious disease reports and, in most jurisdictions, have more confidentiality legal protections than do physician offices.

HIV remains a significant public health problem in the US. As the epidemic evolves, new public health efforts will be needed. Full control of the epidemic might not be achieved until a more effective intervention, such as a vaccine, is available. However, interventions have proven effective and more widespread use would reduce the community burden of the disease.

TABLE

Practice based initiatives that could contribute to HIV reduction in the community

| Make HIV testing a routine part of general medical care. |

| Make HIV testing a routine part of pregnancy care. Test as early as possible in pregnancy and retest those at high risk in the third trimester. |

| Refer those who are HIV-positive to the local public health department for case management. |

| Work collaboratively with the public health department to insure that people with HIV infection receive medical care and social services. |

| Reinforce the message to those infected about how to avoid transmitting the infection to others. |

| Counsel uninfected patients who practice high-risk behaviors about how to reduce their risks of infection, using patient centered methods. |

| Promptly diagnose and treat other sexually transmitted infections. |

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention. Advancing HIV prevention: the science behind the new initiative. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/partners/ahp_science.htm.

2. Hays RB, Paul J, Ekstrand M, Kegeles SM, et al. Actual versus perceived HIV status, sexual behaviors and predictors of unprotected sex among young gay and bisexual men who identify as HIV-negative, HIV-positive and untested. AIDS 1997;11:1495-1502.

3. CDC. Primary and secondary syphilis among men who have sex with men – New York City, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:853-856.

4. CDC. Resurgent bacterial sexually transmitted disease among men who have sex with men—King County, Washington, 1997–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:773-777.

5. Institute of Medicine No Time to Lose: Getting More from HIV Prevention. Committee on HIV Prevention Strategies in the United States, Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

6. CDC. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States, 2002. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2002;14:1-58.Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasr1402.htm.

7. Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. efficacy of risk reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1161-1167.

8. Wenger NS, Kussling FS, Beck K, Shapiro MF. Sexual behavior of individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: The need for intervention. Arch Int Med 1994;154:1849-1854.

9. Kilmarx PH, Hamers FF, Peterman TA. Living with HIV. Experiences and perspectives of HIV-infected sexually transmitted disease clinic patients after posttest counseling. Sex Transm Dis 1998;25:28-37.

10. Higgins DL, Galavotti C, O’Reilly KE, et al. Evidence for the effects of HIV antibody counseling and testing on risk behaviors. JAMA 1991;266:2419-2429

11. Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1397-1405.

12. Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA 1998;280:1161-1167.

13. Walensky RP, Losina E, Steger-Craven KA, Freedberg KA. Identifying undiagnosed human immunodeficiency virus: the yield of routine, voluntary inpatient testing. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:887-892.

14. CDC. Revised recommendations for HIV screening of pregnant women. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50(RR-19):59-86.

15. CDC. Notice to readers: Approval of a new rapid test for HIV antibody. MMWR Morn Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:1051-1052.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention. Advancing HIV prevention: the science behind the new initiative. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/partners/ahp_science.htm.

2. Hays RB, Paul J, Ekstrand M, Kegeles SM, et al. Actual versus perceived HIV status, sexual behaviors and predictors of unprotected sex among young gay and bisexual men who identify as HIV-negative, HIV-positive and untested. AIDS 1997;11:1495-1502.

3. CDC. Primary and secondary syphilis among men who have sex with men – New York City, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:853-856.

4. CDC. Resurgent bacterial sexually transmitted disease among men who have sex with men—King County, Washington, 1997–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:773-777.

5. Institute of Medicine No Time to Lose: Getting More from HIV Prevention. Committee on HIV Prevention Strategies in the United States, Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

6. CDC. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States, 2002. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2002;14:1-58.Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasr1402.htm.

7. Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. efficacy of risk reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1161-1167.

8. Wenger NS, Kussling FS, Beck K, Shapiro MF. Sexual behavior of individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: The need for intervention. Arch Int Med 1994;154:1849-1854.

9. Kilmarx PH, Hamers FF, Peterman TA. Living with HIV. Experiences and perspectives of HIV-infected sexually transmitted disease clinic patients after posttest counseling. Sex Transm Dis 1998;25:28-37.

10. Higgins DL, Galavotti C, O’Reilly KE, et al. Evidence for the effects of HIV antibody counseling and testing on risk behaviors. JAMA 1991;266:2419-2429

11. Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1397-1405.

12. Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA 1998;280:1161-1167.

13. Walensky RP, Losina E, Steger-Craven KA, Freedberg KA. Identifying undiagnosed human immunodeficiency virus: the yield of routine, voluntary inpatient testing. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:887-892.

14. CDC. Revised recommendations for HIV screening of pregnant women. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50(RR-19):59-86.

15. CDC. Notice to readers: Approval of a new rapid test for HIV antibody. MMWR Morn Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:1051-1052.

Hepatitis A: Matching preventive resources to needs

A recent outbreak of Hepatitis A—linked to imported green onions served at a restaurant in Pennsylvania—sickened close to 600 patrons and restaurant staff and killed 3.1 Large-scale hepatitis outbreaks are uncommon. But this well-publicized event drew attention to Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infections and the issue of food safety, and it provides an example of the importance of accurate diagnosis, prompt reporting to public health authorities, and implementation of the preventive measures discussed here to lessen the community impact of this infectious disease.

Those at risk of infection

Hepatitis A virus is passed fecal-orally, and infection usually results from person-to-person transmission within a household or between sexual partners. Young children with hepatitis A are often the source of infection for adults. Day care centers are an important source of infection of children, staff, and parents of children.

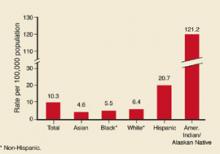

Disease incidence varies considerably by race/ethnicity and geography. American-Indians have the highest rates; Hispanics have the second-highest (Figure 1). Rates are higher in the western US (Figure 2).

Persons at highest risk for HAV infection include travelers to developing countries, men who have sex with men, users of illicit drugs, those with clotting factor disorders, and persons who work with nonhuman primates. Those who have chronic liver disease are at higher risk of fatal, fulminate infection.

Surprisingly, workers in day care centers, health care institutions, schools, and sewage facilities appear not to be at higher than average risk for the community.

FIGURE 1

Hepatitis A by race/ethnicity

Rates of reported hepatitis A by race/ethnicity—United States, 1994. Source: CDC, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System.

FIGURE 2

Average reported cases of hepatitis A per 100,000 population, 1987–1997

Approximately the national average of reported cases during 1987–1997, by county. Source: CDC.

Clinical onset is sudden

Symptoms of illness appear suddenly and include fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, dark urine, and jaundice. By the time symptoms appear, the infection has been incubating from 2 weeks to 2 months (average, 28 days).

Mild symptoms without jaundice are much more likely in children (70%) than in adults (30%). Symptoms usually last less than 2 months but can occasionally persist or relapse for up to 6 months.

Confirm with IgM testing. Diagnosis is confirmed by serologic testing for anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM), which is present before symptoms appear and persists for 6 months. Anti-HAV IgG also occurs early in infection but persists lifelong and cannot be used to distinguish old from current infection. Infectivity is highest in the 2 weeks before jaundice appears.

Matching prevention measures to patient needs

Two forms of HAV prevention are available: immune globulin (IG) and Hepatitis A vaccine.2

Immune globulin

For those traveling to high-risk areas, pre-exposure prophylaxis IG at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg intramuscularly offers up to 3 months of protection; a dose of 0.06 mL/kg intramuscularly provides protection up to 5 months.

Post-exposure prophylaxis is recommended at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg and, if given within 2 weeks of exposure, is 85% effective in preventing disease. If it can be provided within 2 weeks of the last exposure, IG is recommended for all unvaccinated household and sexual contacts of those with laboratory confirmed hepatitis A, and for those who have shared illicit drugs with an infected person.

Caveats. Immune globulin can interfere with the effectiveness of both mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine (MMR) and varicella vaccine. MMR administration should be delayed for 3 months and varicella vaccine for 5 months following IG administration. Immune globulin should not be given for at least 2 weeks after MMR vaccination or three weeks after varicella vaccination. Some IG preparations contain thimerosal; these should not be used in infants or pregnant women.

Hepatitis A vaccine

Two single-antigen hepatitis A vaccines are marketed, both of which are prepared from inactivated virus. Neither product is approved for use in children younger than 2 years. Both vaccines must be given in 2 doses, 6 months apart, for full protection; although in over 90 % of adults, protective antibody levels develop within 4 weeks of the first dose. The Table lists the dose and schedule for each hepatitis A single-antigen vaccine.

Candidates for hepatitis A vaccine:

- Children who live in states, counties, or communities with average annual hepatitis A rates of 20/100,000 or greater

- Travelers or those working in countries with high or intermediate rates of HAV infection (Figure 3)

- Men who have sex with men

- Users of illicit drugs

- Those who work with HAV in laboratories or with non-human primates

- Those with clotting factor disorders

- Those with chronic liver disease

Vaccines are safe. Hepatitis A vaccine does not interfere with other vaccines, appears safe in pregnancy, and causes only minor reactions such as pain and redness at the injection site, headache, or malaise. No credible evidence of serious complications from the vaccine exists. Since it takes 4 weeks for a full immune response to the vaccine to develop, those who need protection sooner should receive IG or both IG and vaccine administered at different sites.

Combination vaccine. There is also a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix) that is approved for those over age 18 years. This vaccine product contains trace amounts of thimerosal, neomycin, formalin, and yeast protein.3

TABLE

Recommended dosages and schedules of hepatitis A vaccines

| Vaccine | Age group | Dose | Volume | # Doses | Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Havrix | 2–18 years | 720 ELU | 0.5 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos |

| 19 years and older | 1440 ELU | 1.0 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos | |

| Vaqta | 2–18 years | 25 U | 0.5 mL | 2 | 0, 6–18 mos |

| 19 years and older | 50 U | 1.0 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos | |

| ELU, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) units; U=units | |||||

FIGURE 3

Endemicity patterns of hepatitis A virus infection worldwide

This map generalizes currently available data, and patterns might vary within countries. Source: CDC.

Public health measures

Hepatitis A virus infection is reportable in every state. Prompt reporting by physicians is important, especially if the infected person is a food handler; serious, widespread, common-source outbreaks can be prevented by such actions. The role of the public health department is to verify cases, investigate outbreaks, institute outbreak control measures and make recommendations regarding routine vaccination. Some local public health departments may offer postexposure IG prophylaxis.

Use of immune globulin. Outbreak control measures will vary with the circumstances. Immune globulin for children and staff has proven effective in limiting outbreaks at daycare centers and should also be considered for parents of children at day care centers with a documented outbreak. A daycare center outbreak is defined as 1 or more cases in children or staff at a center or in 2 or more households of center attendees. Immune globulin is usually not effective in common source outbreaks, such as the recent Pennsylvania case, because the 2-week time period for protection has usually passed before the source of the outbreak is discovered.

While deaths from HAV are not common— approximately 100 per year—the individual and community morbidity caused by the virus can be considerable. Infection leads to hospitalization in 11% to 22% of cases and large economic losses with adults suffering 27 days of lost work and each case totaling over $2000 of direct and indirect costs.2 Local public health departments can also expend considerable resources trying to control outbreaks of this disease.

Indications for vaccination. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends routine vaccination for children who live in communities, counties, or states with HAV rates equal to or greater than 20/100,000, and it recommends considering routine vaccination when rates are equal to or greater than 10/100,000.

Following through. To lower community morbidity from HAV, be aware of the incidence and epidemiology of HAV in your community, suspect and accurately diagnose HAV illness using serological confirmation, promptly report all HAV cases to the local or state public health department, vaccinate patients who are in high-risk groups, offer prompt post-exposure prophylaxis to household and sexual contacts of those with acute HAV infection, and adhere to local recommendations regarding routine vaccination of children.

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hepatitis A outbreak associated with green onions at a restaurant –Monaca, Pennsylvania, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;53:1-3.

2. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Rapid Res 1990;48(RR-12):1-37.

3. CDC. FDA approval for a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:806-807.

A recent outbreak of Hepatitis A—linked to imported green onions served at a restaurant in Pennsylvania—sickened close to 600 patrons and restaurant staff and killed 3.1 Large-scale hepatitis outbreaks are uncommon. But this well-publicized event drew attention to Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infections and the issue of food safety, and it provides an example of the importance of accurate diagnosis, prompt reporting to public health authorities, and implementation of the preventive measures discussed here to lessen the community impact of this infectious disease.

Those at risk of infection

Hepatitis A virus is passed fecal-orally, and infection usually results from person-to-person transmission within a household or between sexual partners. Young children with hepatitis A are often the source of infection for adults. Day care centers are an important source of infection of children, staff, and parents of children.

Disease incidence varies considerably by race/ethnicity and geography. American-Indians have the highest rates; Hispanics have the second-highest (Figure 1). Rates are higher in the western US (Figure 2).

Persons at highest risk for HAV infection include travelers to developing countries, men who have sex with men, users of illicit drugs, those with clotting factor disorders, and persons who work with nonhuman primates. Those who have chronic liver disease are at higher risk of fatal, fulminate infection.

Surprisingly, workers in day care centers, health care institutions, schools, and sewage facilities appear not to be at higher than average risk for the community.

FIGURE 1

Hepatitis A by race/ethnicity

Rates of reported hepatitis A by race/ethnicity—United States, 1994. Source: CDC, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System.

FIGURE 2

Average reported cases of hepatitis A per 100,000 population, 1987–1997

Approximately the national average of reported cases during 1987–1997, by county. Source: CDC.

Clinical onset is sudden

Symptoms of illness appear suddenly and include fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, dark urine, and jaundice. By the time symptoms appear, the infection has been incubating from 2 weeks to 2 months (average, 28 days).

Mild symptoms without jaundice are much more likely in children (70%) than in adults (30%). Symptoms usually last less than 2 months but can occasionally persist or relapse for up to 6 months.

Confirm with IgM testing. Diagnosis is confirmed by serologic testing for anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM), which is present before symptoms appear and persists for 6 months. Anti-HAV IgG also occurs early in infection but persists lifelong and cannot be used to distinguish old from current infection. Infectivity is highest in the 2 weeks before jaundice appears.

Matching prevention measures to patient needs

Two forms of HAV prevention are available: immune globulin (IG) and Hepatitis A vaccine.2

Immune globulin

For those traveling to high-risk areas, pre-exposure prophylaxis IG at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg intramuscularly offers up to 3 months of protection; a dose of 0.06 mL/kg intramuscularly provides protection up to 5 months.

Post-exposure prophylaxis is recommended at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg and, if given within 2 weeks of exposure, is 85% effective in preventing disease. If it can be provided within 2 weeks of the last exposure, IG is recommended for all unvaccinated household and sexual contacts of those with laboratory confirmed hepatitis A, and for those who have shared illicit drugs with an infected person.

Caveats. Immune globulin can interfere with the effectiveness of both mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine (MMR) and varicella vaccine. MMR administration should be delayed for 3 months and varicella vaccine for 5 months following IG administration. Immune globulin should not be given for at least 2 weeks after MMR vaccination or three weeks after varicella vaccination. Some IG preparations contain thimerosal; these should not be used in infants or pregnant women.

Hepatitis A vaccine

Two single-antigen hepatitis A vaccines are marketed, both of which are prepared from inactivated virus. Neither product is approved for use in children younger than 2 years. Both vaccines must be given in 2 doses, 6 months apart, for full protection; although in over 90 % of adults, protective antibody levels develop within 4 weeks of the first dose. The Table lists the dose and schedule for each hepatitis A single-antigen vaccine.

Candidates for hepatitis A vaccine:

- Children who live in states, counties, or communities with average annual hepatitis A rates of 20/100,000 or greater

- Travelers or those working in countries with high or intermediate rates of HAV infection (Figure 3)

- Men who have sex with men

- Users of illicit drugs

- Those who work with HAV in laboratories or with non-human primates

- Those with clotting factor disorders

- Those with chronic liver disease

Vaccines are safe. Hepatitis A vaccine does not interfere with other vaccines, appears safe in pregnancy, and causes only minor reactions such as pain and redness at the injection site, headache, or malaise. No credible evidence of serious complications from the vaccine exists. Since it takes 4 weeks for a full immune response to the vaccine to develop, those who need protection sooner should receive IG or both IG and vaccine administered at different sites.

Combination vaccine. There is also a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix) that is approved for those over age 18 years. This vaccine product contains trace amounts of thimerosal, neomycin, formalin, and yeast protein.3

TABLE

Recommended dosages and schedules of hepatitis A vaccines

| Vaccine | Age group | Dose | Volume | # Doses | Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Havrix | 2–18 years | 720 ELU | 0.5 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos |

| 19 years and older | 1440 ELU | 1.0 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos | |

| Vaqta | 2–18 years | 25 U | 0.5 mL | 2 | 0, 6–18 mos |

| 19 years and older | 50 U | 1.0 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos | |

| ELU, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) units; U=units | |||||

FIGURE 3

Endemicity patterns of hepatitis A virus infection worldwide

This map generalizes currently available data, and patterns might vary within countries. Source: CDC.

Public health measures

Hepatitis A virus infection is reportable in every state. Prompt reporting by physicians is important, especially if the infected person is a food handler; serious, widespread, common-source outbreaks can be prevented by such actions. The role of the public health department is to verify cases, investigate outbreaks, institute outbreak control measures and make recommendations regarding routine vaccination. Some local public health departments may offer postexposure IG prophylaxis.

Use of immune globulin. Outbreak control measures will vary with the circumstances. Immune globulin for children and staff has proven effective in limiting outbreaks at daycare centers and should also be considered for parents of children at day care centers with a documented outbreak. A daycare center outbreak is defined as 1 or more cases in children or staff at a center or in 2 or more households of center attendees. Immune globulin is usually not effective in common source outbreaks, such as the recent Pennsylvania case, because the 2-week time period for protection has usually passed before the source of the outbreak is discovered.

While deaths from HAV are not common— approximately 100 per year—the individual and community morbidity caused by the virus can be considerable. Infection leads to hospitalization in 11% to 22% of cases and large economic losses with adults suffering 27 days of lost work and each case totaling over $2000 of direct and indirect costs.2 Local public health departments can also expend considerable resources trying to control outbreaks of this disease.

Indications for vaccination. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends routine vaccination for children who live in communities, counties, or states with HAV rates equal to or greater than 20/100,000, and it recommends considering routine vaccination when rates are equal to or greater than 10/100,000.

Following through. To lower community morbidity from HAV, be aware of the incidence and epidemiology of HAV in your community, suspect and accurately diagnose HAV illness using serological confirmation, promptly report all HAV cases to the local or state public health department, vaccinate patients who are in high-risk groups, offer prompt post-exposure prophylaxis to household and sexual contacts of those with acute HAV infection, and adhere to local recommendations regarding routine vaccination of children.

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: [email protected].

A recent outbreak of Hepatitis A—linked to imported green onions served at a restaurant in Pennsylvania—sickened close to 600 patrons and restaurant staff and killed 3.1 Large-scale hepatitis outbreaks are uncommon. But this well-publicized event drew attention to Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infections and the issue of food safety, and it provides an example of the importance of accurate diagnosis, prompt reporting to public health authorities, and implementation of the preventive measures discussed here to lessen the community impact of this infectious disease.

Those at risk of infection

Hepatitis A virus is passed fecal-orally, and infection usually results from person-to-person transmission within a household or between sexual partners. Young children with hepatitis A are often the source of infection for adults. Day care centers are an important source of infection of children, staff, and parents of children.

Disease incidence varies considerably by race/ethnicity and geography. American-Indians have the highest rates; Hispanics have the second-highest (Figure 1). Rates are higher in the western US (Figure 2).

Persons at highest risk for HAV infection include travelers to developing countries, men who have sex with men, users of illicit drugs, those with clotting factor disorders, and persons who work with nonhuman primates. Those who have chronic liver disease are at higher risk of fatal, fulminate infection.

Surprisingly, workers in day care centers, health care institutions, schools, and sewage facilities appear not to be at higher than average risk for the community.

FIGURE 1

Hepatitis A by race/ethnicity

Rates of reported hepatitis A by race/ethnicity—United States, 1994. Source: CDC, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System.

FIGURE 2

Average reported cases of hepatitis A per 100,000 population, 1987–1997

Approximately the national average of reported cases during 1987–1997, by county. Source: CDC.

Clinical onset is sudden

Symptoms of illness appear suddenly and include fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, dark urine, and jaundice. By the time symptoms appear, the infection has been incubating from 2 weeks to 2 months (average, 28 days).

Mild symptoms without jaundice are much more likely in children (70%) than in adults (30%). Symptoms usually last less than 2 months but can occasionally persist or relapse for up to 6 months.

Confirm with IgM testing. Diagnosis is confirmed by serologic testing for anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM), which is present before symptoms appear and persists for 6 months. Anti-HAV IgG also occurs early in infection but persists lifelong and cannot be used to distinguish old from current infection. Infectivity is highest in the 2 weeks before jaundice appears.

Matching prevention measures to patient needs

Two forms of HAV prevention are available: immune globulin (IG) and Hepatitis A vaccine.2

Immune globulin

For those traveling to high-risk areas, pre-exposure prophylaxis IG at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg intramuscularly offers up to 3 months of protection; a dose of 0.06 mL/kg intramuscularly provides protection up to 5 months.

Post-exposure prophylaxis is recommended at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg and, if given within 2 weeks of exposure, is 85% effective in preventing disease. If it can be provided within 2 weeks of the last exposure, IG is recommended for all unvaccinated household and sexual contacts of those with laboratory confirmed hepatitis A, and for those who have shared illicit drugs with an infected person.

Caveats. Immune globulin can interfere with the effectiveness of both mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine (MMR) and varicella vaccine. MMR administration should be delayed for 3 months and varicella vaccine for 5 months following IG administration. Immune globulin should not be given for at least 2 weeks after MMR vaccination or three weeks after varicella vaccination. Some IG preparations contain thimerosal; these should not be used in infants or pregnant women.

Hepatitis A vaccine

Two single-antigen hepatitis A vaccines are marketed, both of which are prepared from inactivated virus. Neither product is approved for use in children younger than 2 years. Both vaccines must be given in 2 doses, 6 months apart, for full protection; although in over 90 % of adults, protective antibody levels develop within 4 weeks of the first dose. The Table lists the dose and schedule for each hepatitis A single-antigen vaccine.

Candidates for hepatitis A vaccine:

- Children who live in states, counties, or communities with average annual hepatitis A rates of 20/100,000 or greater

- Travelers or those working in countries with high or intermediate rates of HAV infection (Figure 3)

- Men who have sex with men

- Users of illicit drugs

- Those who work with HAV in laboratories or with non-human primates

- Those with clotting factor disorders

- Those with chronic liver disease

Vaccines are safe. Hepatitis A vaccine does not interfere with other vaccines, appears safe in pregnancy, and causes only minor reactions such as pain and redness at the injection site, headache, or malaise. No credible evidence of serious complications from the vaccine exists. Since it takes 4 weeks for a full immune response to the vaccine to develop, those who need protection sooner should receive IG or both IG and vaccine administered at different sites.

Combination vaccine. There is also a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix) that is approved for those over age 18 years. This vaccine product contains trace amounts of thimerosal, neomycin, formalin, and yeast protein.3

TABLE

Recommended dosages and schedules of hepatitis A vaccines

| Vaccine | Age group | Dose | Volume | # Doses | Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Havrix | 2–18 years | 720 ELU | 0.5 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos |

| 19 years and older | 1440 ELU | 1.0 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos | |

| Vaqta | 2–18 years | 25 U | 0.5 mL | 2 | 0, 6–18 mos |

| 19 years and older | 50 U | 1.0 mL | 2 | 0, 6–12 mos | |

| ELU, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) units; U=units | |||||

FIGURE 3

Endemicity patterns of hepatitis A virus infection worldwide

This map generalizes currently available data, and patterns might vary within countries. Source: CDC.

Public health measures

Hepatitis A virus infection is reportable in every state. Prompt reporting by physicians is important, especially if the infected person is a food handler; serious, widespread, common-source outbreaks can be prevented by such actions. The role of the public health department is to verify cases, investigate outbreaks, institute outbreak control measures and make recommendations regarding routine vaccination. Some local public health departments may offer postexposure IG prophylaxis.

Use of immune globulin. Outbreak control measures will vary with the circumstances. Immune globulin for children and staff has proven effective in limiting outbreaks at daycare centers and should also be considered for parents of children at day care centers with a documented outbreak. A daycare center outbreak is defined as 1 or more cases in children or staff at a center or in 2 or more households of center attendees. Immune globulin is usually not effective in common source outbreaks, such as the recent Pennsylvania case, because the 2-week time period for protection has usually passed before the source of the outbreak is discovered.

While deaths from HAV are not common— approximately 100 per year—the individual and community morbidity caused by the virus can be considerable. Infection leads to hospitalization in 11% to 22% of cases and large economic losses with adults suffering 27 days of lost work and each case totaling over $2000 of direct and indirect costs.2 Local public health departments can also expend considerable resources trying to control outbreaks of this disease.

Indications for vaccination. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends routine vaccination for children who live in communities, counties, or states with HAV rates equal to or greater than 20/100,000, and it recommends considering routine vaccination when rates are equal to or greater than 10/100,000.

Following through. To lower community morbidity from HAV, be aware of the incidence and epidemiology of HAV in your community, suspect and accurately diagnose HAV illness using serological confirmation, promptly report all HAV cases to the local or state public health department, vaccinate patients who are in high-risk groups, offer prompt post-exposure prophylaxis to household and sexual contacts of those with acute HAV infection, and adhere to local recommendations regarding routine vaccination of children.

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hepatitis A outbreak associated with green onions at a restaurant –Monaca, Pennsylvania, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;53:1-3.

2. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Rapid Res 1990;48(RR-12):1-37.

3. CDC. FDA approval for a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:806-807.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hepatitis A outbreak associated with green onions at a restaurant –Monaca, Pennsylvania, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;53:1-3.

2. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Rapid Res 1990;48(RR-12):1-37.

3. CDC. FDA approval for a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:806-807.

Sexually transmitted disease: Easier screening tests, single-dose therapies

Success in the United States in reducing morbidity caused by syphilis and gonorrhea has been offset by the rising morbidity seen with other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as chlamydia and herpes. Also, recent increases in the prevalence of syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) underscore the fact that sustaining public health successes depends on constant surveillance and a commitment to control efforts.

This Practice Alert focuses on 3 prevalent STDs: syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia—those patients most likely to be infected, and specific developments in screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

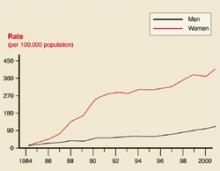

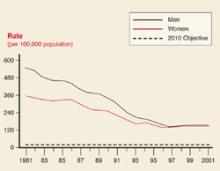

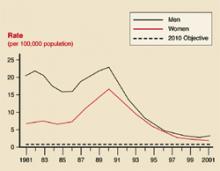

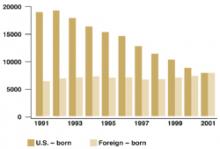

Those most likely to be infected

In 2001, 783,000 cases of chlamydia, 362,000 cases of gonorrhea, and 31,600 cases of syphilis were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 The true incidence of each disease is unknown. Historical trends in the number of cases reported are reflected in Figures 1 ,2, and 3. In 2001, there was a slight increase in the number of syphilis cases, reversing a 10-year downward trend. The number of chlamydia cases continued to rise, which may reflect improved screening and reporting, while the number of gonorrhea cases continued downward.

FIGURE 1

Chlamydia rates

Chlamydia rates by sex: United States, 1984–2001.

FIGURE 2

Gonorrhea rates

Gonorrhea rates by sex: United States 1981–2001, and the Healthy People year 2010 objective.

FIGURE 3

Syphilis rates

Primary and secondary syphilis rates by sex: United States 1881–2001, and the Healthy People year 2010 objective.

Chlamydia

Infection with Chlamydia trachomatisis reported 4 times as often in women as in men, reflecting better screening of women in family planning programs and during prenatal care.2 The highest rates of chlamydia in women occur in the age groups 15 to 19 years (25/1000) and 20 to 25 years (24/1000). Testing in family planning clinics has yielded chlamydia infection rates of 5.6% among these women.2

Gonorrhea and syphilis

The age groups at highest risk for gonorrhea are 15 to 19 years for women (703/100,000) and 20 to 24 for men (563/100,000).3 For syphilis, the highest risk for women is age 20 to 24 years (3.8/100,000 for primary and secondary syphilis) and 35 to 39 years for men (7.2/100,000).4 There are marked geographic variations in the rates of syphilis (Figure 4). The recent increase in syphilis has been among men, largely attributed to homosexual activity.

FIGURE 4

Syphilis rates by county

Counties with primary and secondary syphilis rates above and below the Healthy People year 2010 objective: United States, 2001.

When and whom to screen

Many STDs persist asymptomatically. These silent infections can cause long-term morbidity such as infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancies, and chronic pelvic pain. Both the United States Preventive Services Task Force and the American Academy of Family Physicians recommend that screening for STDs be performed in specific circumstances (Table 1).9,10

These recommendations should probably be considered a minimum standard, with other groups and diseases included based on the local epidemiology. The local or state health department can be a useful source of information on local epidemiologic patterns and screening and treatment recommendations. Keep in mind that the accuracy of local disease statistics depends on screening and disease reporting by local physicians.

TABLE 1

When and whom to screen for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis

| Chlamydia | Sexually active women aged 25 years should be routinely tested, and tested during pregnancy at the first prenatal care visit. |

| Other women at high risk* for chlamydia should be routinely tested, and tested during pregnancy at the first prenatal care visit. | |

| Gonorrhea | High-risk women* should be routinely tested, and tested during pregnancy at the first prenatal care visit |

| Syphilis | High-risk women should be routinely tested, and tested during pregnancy at the first prenatal care visit, again in the third trimester, and at delivery. |

| All pregnant women should be tested at the first prenatal care visit. | |

| * Definitions for high risk vary but generally include the following: those with multiple sex partners, other STDs, sexual contact to those with disease, or who exchange sex for money for drugs. | |

Urine screening tests

New nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) facilitate screening and diagnosis of chlamydia and gonorrhea with a urine sample. This offers the ease of urine collection in both men and women, with the added benefit of sensitivitiesand specificities equal to those obtained from urethral or endocervical samples. NAATs make possible urine screening in settings where urethral and cervical samples may not be possible because of logistics or patient nonacceptance.

NAATs do not require the presence of live organisms, and only a small number of organisms are needed for accurate test results.

One disadvantage of these tests is an inability to determine antibiotic sensitivities. Another is occasional false-positive results from dead organisms, which can occur if test of cures are performed too soon after treatment (less than 3 weeks).

NAATs can be used on urethral and endocervical swabs as well as urine samples. But they should not be used on oral or rectal samples. Some products test for both gonorrhea and chlamydia in a single specimen. A positive result could be due to either organism, however, requiring more specific testing.

The CDC believes that NAATs on urine samples are acceptable methods of screening for genital gonorrhea and chlamydia in both men and women, although for gonorrhea, cultures of urethral and endocervical swabs are preferred so that sensitivities can be obtained. Gonorrhea and chlamydia cultures are recommended for diagnosing oropharyngeal or anal infection.11

Treatment

Single-dose therapies

A variety of single-dose therapies for STDs are now available (Table 2). Single-dose therapies are convenient for patients, and they encourage quicker completion of therapy. If single-dose therapy is administered in the clinical setting, it is essentially directly observed therapy. Tests of cure can be avoided when common STDs are treated with recommended regimens and completion of treatment is assured.

A disadvantage often of single-dose therapy is its cost. However, when compared with the total costs of incomplete treatments—lower cure rates, return visits, increased infection of contacts—the price of a single-dose agent may seem more acceptable.

Many of the single-dose therapies for gonorrhea are quinolones, which should not be used to treat gonorrhea in (or acquired in) areas with high rates of quinolone resistance (Hawaii, parts of California). Consult your local or state health department to learn the local rates of resistance.

TABLE 2

Single-dose therapies available for common STDs

| Infection | Single-dose therapy |

|---|---|

| Chlamydia | Azithromycin 1 gm (oral) |

| Gonorrhea | Cefixime 400 mg (oral)*† |

| Ceftriaxone 125 mg (intramuscular) | |

| Ciprofloxacin 500 mg (oral) | |

| Ofloxacin 400 mg (oral)† | |

| Levofloxacin 250 mg (oral)† | |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Azithromycin 1 gm (oral) |

| Syphilis (primary, secondary, early latent) | Benzathene penicillin 2.4 million units (intramuscular) |

| *Cefixime tablets are currently not being manufactured. | |

| †Not recommended for pharyngeal gonorrhea. | |

Management of sex partners

Treatment of patients with STDs is not complete until sex partners who have been exposed are also evaluated, tested, and treated. The common STDs discussed in this article are reportable to local and state health departments. However, in many jurisdictions, cost and staffing limitations prevent public health investigation and contact notification of gonorrhea or chlamydia infections. Family physicians in such locations need to advise their patients to notify sexual contacts of their exposure and recommend that they be examined and treated.

Confidentiality. When patients express concern about having their infections reported to the public health department, reassure them that these departments have a very good record of maintaining patient confidentiality and that public health information is usually afforded a greater degree of protection than information in an office medical record. When public health departments notify sexual contacts of their exposure, they do not reveal who exposed them, although in some instances the sexual contacts can figure this out.

Gonorrhea or chlamydia. The CDC recommends that when a patient is diagnosed with either gonorrhea or chlamydia, all their sex partners from the past 60 days should be evaluated and treated prophylactically.12 Patients and their sex partner(s) should avoid intercourse for 7 days after initiation of treatment and until symptoms resolve.

Syphilis. Syphilis is more complicated. Persons who were exposed to primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis within the 90 days prior to diagnosis should be treated prophylactically. Those exposed from 91 days to 6 months prior to diagnosis of secondary syphilis, or 91 days to 1 year prior to the diagnosis of early latent syphilis, should be treated prophylactically if serology testing is not available or if follow up is uncertain.

Other infections. Current sex partners of those with mucopurulent cervicitis or nongonococcal urethritis should also be evaluated and treated with the same regimen chosen for the index patient. Sex partners within the past 60 days of women with pelvic inflammatory disease should be evaluated and treated prophylactically for both gonorrhea and chlamydia while sex partners within the past 60 days of men with epididymitis should be evaluated but not necessarily treated prophylactically.

As of May 2001,169 million Americans were regular users of the Internet.5 Internet sites created for the purpose of facilitating sexual contact have proliferated and include those for heterosexuals, gay men, lesbians, swingers, and those interested in group sex.6

Use of the Internet to meet sex partners has generated concern in public health circles because of the potential for increased risk of STDs, including HIV/AIDS, from anonymous sex. One case report describes an outbreak of syphilis among gay men who were participants in an Internet chat room for sexual networking.7 Each man with syphilis who was located reported an average of 12 recent sex partners (range of 2–47); a mean of 6 partners (range of 2–15) were located and examined. Four out of the 7 with syphilis were also positive for HIV.

Another study of users of HIVcounseling and testing services found that 16% had sought sex partners on the Internet and 65% of these reported having sex with someone they met on the Internet.8 Internet users reported more previous STDs,more partners, more HIV-positive partners,and more sex with gay men than did non-Internet users.

While much remains to be learned about this topic,these studies indicate that Internet-initiated sex may involve higher risk than sex initiated through other means, although anonymous sex and having multiple sex partners should be considered high-risk activities however they are initiated. Warn patients about these risks.

Collaboration is key to control

The impact of STDs on a community can be moderated when family physicians and local public health departments collaborate. The department’s role includes providing information on the local epidemiology of STDs; assistance in screening, testing, and treating; and, depending on available resources, notifying sexual partners. Many larger public health departments operate a publicly funded STD clinic for patients and sexual contacts who lack financial resources.

Family physicians can screen high-risk persons, use recommended treatment regimens, report communicable diseases as required by state statute, and assist with partner notification by urging patients to cooperate with the local health agency and, if public health partner notification is not available, urging patients to notify their sexual partners.

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention. Division of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001 National STD Surveillance Report. Table 1: Cases of sexually transmitted diseases reported by state health departments and rates per 100,000 civilian population: United States, 1941–2001. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/stats/tables/table1.htm. Accessed on October 27, 2003.

2. CDC. Division of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Chlamydia. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/stats/2001chlamydia.htm. Accessed on October 27, 2003.

3. CDC. Division of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Gonorrhea. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/stats/2001gonorrhea.htm. Accessed on October 27, 2003.

4. CDC. Division of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Syphilis. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/stats/2001syphilis.htm. Accessed on October 27, 2003.

5. Available at www.eurmktg.com/globstats.

6. Bull SS, McFarlane M. Soliciting sex on the internet. What are the risks for sexually transmitted diseases and HIV? Sex Transm Dis 2000;27:545-550.

7. Klausner JD, Wolf W, Fischer-Ponce L, Zolt I, Katz MH. Tracing a syphilis outbreak through cyberspace. JAMA 2000;284:447-449.

8. McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. The internet as a newly-emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA 2000;284:443-446.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRCQ). United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening: chlamydia infection. Available at www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschlm.htm. Accessed on October 27, 2003.

10. American Academy of Family Physicians. Introduction to AAFP summary of policy recommendations for periodic health examinations. Available at www.aafp.org/x10601.xml. Accessed on October 27, 2003.

11. CDC. Screening tests to detect chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea infections. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-15):1-38.

12. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR6):1-78.

Success in the United States in reducing morbidity caused by syphilis and gonorrhea has been offset by the rising morbidity seen with other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as chlamydia and herpes. Also, recent increases in the prevalence of syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) underscore the fact that sustaining public health successes depends on constant surveillance and a commitment to control efforts.

This Practice Alert focuses on 3 prevalent STDs: syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia—those patients most likely to be infected, and specific developments in screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

Those most likely to be infected

In 2001, 783,000 cases of chlamydia, 362,000 cases of gonorrhea, and 31,600 cases of syphilis were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 The true incidence of each disease is unknown. Historical trends in the number of cases reported are reflected in Figures 1 ,2, and 3. In 2001, there was a slight increase in the number of syphilis cases, reversing a 10-year downward trend. The number of chlamydia cases continued to rise, which may reflect improved screening and reporting, while the number of gonorrhea cases continued downward.

FIGURE 1

Chlamydia rates

Chlamydia rates by sex: United States, 1984–2001.

FIGURE 2

Gonorrhea rates

Gonorrhea rates by sex: United States 1981–2001, and the Healthy People year 2010 objective.

FIGURE 3

Syphilis rates