User login

Doug Brunk is a San Diego-based award-winning reporter who began covering health care in 1991. Before joining the company, he wrote for the health sciences division of Columbia University and was an associate editor at Contemporary Long Term Care magazine when it won a Jesse H. Neal Award. His work has been syndicated by the Los Angeles Times and he is the author of two books related to the University of Kentucky Wildcats men's basketball program. Doug has a master’s degree in magazine journalism from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Follow him on Twitter @dougbrunk.

Novel platform harnesses 3D laser technology for skin treatments

in all skin types, according to speakers at a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy.

The products feature “focal point technology,” which pairs 3D laser targeting with an integrated high-resolution imaging system (IntelliView), to help the user guide treatments at selectable depths. They have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for use in skin resurfacing procedures, and to treat benign pigmented lesions of the skin, including hyperpigmentation, and were created by Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, Rox Anderson, MD, and Henry Chan, MD, of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Irina Erenburg, PhD, CEO of AVAVA, the company that markets the products.

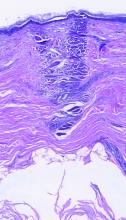

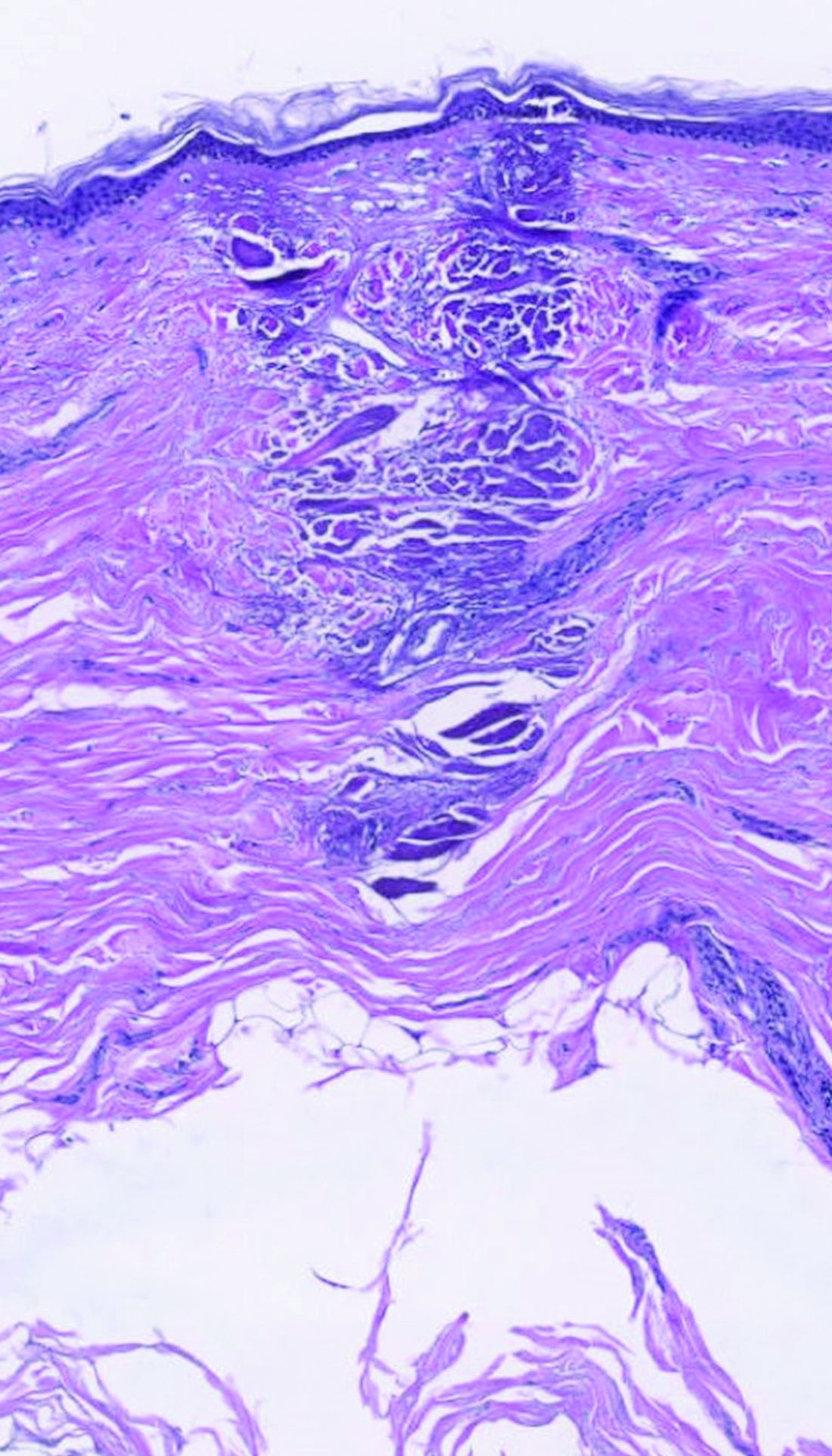

dermally focused treatment with Focal Point Technology. The coagulation zone, in dark purple, shows a deep conical lesion that extends 1.3 mm deep with significant epidermal sparing.

At the meeting, Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center, described focal point technology as an adjustable intradermally focused laser platform guided by real-time visual mapping to ensure the precise dose and depth of energy as the user performs treatments. “This is the key for rejuvenation,” he said. “You can go to different depths of the skin. You can be superficial for dyschromia and maybe a little bit different for wrinkles. If you want to treat scars, you go a little bit deeper. Coagulation occurs at these different depths.”

The collimated beam from conventional lasers affects all tissue in its path. The laser beam from the AVAVA product, however, creates a cone-shaped profile of injury in the dermis that minimizes the area of epidermal damage, making it safe in skin of color, according to Dr. Avram. “The beam comes to a focal point in the dermis at the depth that you want it to,” he explained during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “That’s where the energy is going to focus and it bypasses the dermal/epidermal junction, which traditional fractional lasers cannot. What’s interesting about this platform is that you have a wavelength for skin rejuvenation, then you have wavelengths for pigment, which allows you to treat conditions like melasma at different depths.”

The AVAVA high-speed IntelliView imaging system features 10-micron resolution, “so you get exquisite imaging that can help guide your treatments,” he said. It also features image acquisition and storage with artificial intelligence algorithm interrogation and the ability to personalize treatments to the patient’s specific skin type. Commercial availability is expected in the first half of 2023, Dr. Avram said.

In a separate presentation, New York-based cosmetic dermatologist Roy G. Geronemus, MD, who has been involved in clinical trials of AVAVA’s focal point technology, said that patients “feel less pain and have less down time than we saw previously with other nonablative, fractional technologies.”

Downtime involves “just some mild redness,” he said, adding that he is encouraged by early results seen to date, and that “there appears to be some unique capabilities that will be borne out as the clinical studies progress.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Galderma, and Revelle. He is an investigator for Endo and holds ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis and La Jolla NanoMedical. Dr. Geronemus disclosed having financial relationships with numerous device and pharmaceutical companies.

in all skin types, according to speakers at a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy.

The products feature “focal point technology,” which pairs 3D laser targeting with an integrated high-resolution imaging system (IntelliView), to help the user guide treatments at selectable depths. They have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for use in skin resurfacing procedures, and to treat benign pigmented lesions of the skin, including hyperpigmentation, and were created by Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, Rox Anderson, MD, and Henry Chan, MD, of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Irina Erenburg, PhD, CEO of AVAVA, the company that markets the products.

dermally focused treatment with Focal Point Technology. The coagulation zone, in dark purple, shows a deep conical lesion that extends 1.3 mm deep with significant epidermal sparing.

At the meeting, Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center, described focal point technology as an adjustable intradermally focused laser platform guided by real-time visual mapping to ensure the precise dose and depth of energy as the user performs treatments. “This is the key for rejuvenation,” he said. “You can go to different depths of the skin. You can be superficial for dyschromia and maybe a little bit different for wrinkles. If you want to treat scars, you go a little bit deeper. Coagulation occurs at these different depths.”

The collimated beam from conventional lasers affects all tissue in its path. The laser beam from the AVAVA product, however, creates a cone-shaped profile of injury in the dermis that minimizes the area of epidermal damage, making it safe in skin of color, according to Dr. Avram. “The beam comes to a focal point in the dermis at the depth that you want it to,” he explained during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “That’s where the energy is going to focus and it bypasses the dermal/epidermal junction, which traditional fractional lasers cannot. What’s interesting about this platform is that you have a wavelength for skin rejuvenation, then you have wavelengths for pigment, which allows you to treat conditions like melasma at different depths.”

The AVAVA high-speed IntelliView imaging system features 10-micron resolution, “so you get exquisite imaging that can help guide your treatments,” he said. It also features image acquisition and storage with artificial intelligence algorithm interrogation and the ability to personalize treatments to the patient’s specific skin type. Commercial availability is expected in the first half of 2023, Dr. Avram said.

In a separate presentation, New York-based cosmetic dermatologist Roy G. Geronemus, MD, who has been involved in clinical trials of AVAVA’s focal point technology, said that patients “feel less pain and have less down time than we saw previously with other nonablative, fractional technologies.”

Downtime involves “just some mild redness,” he said, adding that he is encouraged by early results seen to date, and that “there appears to be some unique capabilities that will be borne out as the clinical studies progress.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Galderma, and Revelle. He is an investigator for Endo and holds ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis and La Jolla NanoMedical. Dr. Geronemus disclosed having financial relationships with numerous device and pharmaceutical companies.

in all skin types, according to speakers at a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy.

The products feature “focal point technology,” which pairs 3D laser targeting with an integrated high-resolution imaging system (IntelliView), to help the user guide treatments at selectable depths. They have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for use in skin resurfacing procedures, and to treat benign pigmented lesions of the skin, including hyperpigmentation, and were created by Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, Rox Anderson, MD, and Henry Chan, MD, of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Irina Erenburg, PhD, CEO of AVAVA, the company that markets the products.

dermally focused treatment with Focal Point Technology. The coagulation zone, in dark purple, shows a deep conical lesion that extends 1.3 mm deep with significant epidermal sparing.

At the meeting, Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center, described focal point technology as an adjustable intradermally focused laser platform guided by real-time visual mapping to ensure the precise dose and depth of energy as the user performs treatments. “This is the key for rejuvenation,” he said. “You can go to different depths of the skin. You can be superficial for dyschromia and maybe a little bit different for wrinkles. If you want to treat scars, you go a little bit deeper. Coagulation occurs at these different depths.”

The collimated beam from conventional lasers affects all tissue in its path. The laser beam from the AVAVA product, however, creates a cone-shaped profile of injury in the dermis that minimizes the area of epidermal damage, making it safe in skin of color, according to Dr. Avram. “The beam comes to a focal point in the dermis at the depth that you want it to,” he explained during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “That’s where the energy is going to focus and it bypasses the dermal/epidermal junction, which traditional fractional lasers cannot. What’s interesting about this platform is that you have a wavelength for skin rejuvenation, then you have wavelengths for pigment, which allows you to treat conditions like melasma at different depths.”

The AVAVA high-speed IntelliView imaging system features 10-micron resolution, “so you get exquisite imaging that can help guide your treatments,” he said. It also features image acquisition and storage with artificial intelligence algorithm interrogation and the ability to personalize treatments to the patient’s specific skin type. Commercial availability is expected in the first half of 2023, Dr. Avram said.

In a separate presentation, New York-based cosmetic dermatologist Roy G. Geronemus, MD, who has been involved in clinical trials of AVAVA’s focal point technology, said that patients “feel less pain and have less down time than we saw previously with other nonablative, fractional technologies.”

Downtime involves “just some mild redness,” he said, adding that he is encouraged by early results seen to date, and that “there appears to be some unique capabilities that will be borne out as the clinical studies progress.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Galderma, and Revelle. He is an investigator for Endo and holds ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis and La Jolla NanoMedical. Dr. Geronemus disclosed having financial relationships with numerous device and pharmaceutical companies.

FROM A LASER & AESTHETIC SKIN THERAPY COURSE

Applications for laser-assisted drug delivery on the horizon, expert says

For those who view fractional ablative laser–assisted drug delivery as a pie-in-the-sky procedure that will take years to work its way into routine clinical practice, think again.

According to Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, DMSc, .

“The groundwork has been established over a decade with more than 100 publications available on PubMed,” Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, said during a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy. “There is no doubt that by drilling tiny little holes or channels with ablative fractional lasers, we enhance drug delivery to the skin, and we also empower different topical treatment regimens. Also, laser-assisted drug delivery holds the potential to bring new innovations into established medicine.”

Many studies have demonstrated that clinicians can enhance drug uptake into the skin with the fractional 10,600 nm CO2 laser, the fractional 2,940 nm erbium:YAG laser, and the 1,927 nm thulium laser, but proper tuning of the devices is key. The lower the density, the better, Dr. Haedersdal said.

“Typically, we use 5% density or 5% coverage, sometimes 10%-15%, but don’t go higher in order to avoid the risk of having a systemic uptake,” she said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “Also, the pulse energy for channel depth needs to be tailored to the specific dermatologic disease being treated,” she said, noting that for melasma, for example, “very low pulse energies” would be used, but they would be higher for treating thicker lesions, such as a hypertrophic scar.

Treatment with ablative fractional lasers enhances drug accumulation in the skin of any drug or substance applied to the skin, and clinical indications are expanding rapidly. Established indications include combining ablative fractional lasers and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for AKs and combining ablative fractional lasers and triamcinolone or 5-FU for scars. “Although we have a good body of evidence, particularly for AKs, it’s still an off-label use,” she emphasized.

Evolving indications include concomitant use of ablative fractional laser and vitamins and cosmeceuticals for rejuvenation; lidocaine for local anesthetics; tranexamic acid and hydroquinone for melasma; antifungals for onychomycosis; Botox for hyperhidrosis; minoxidil for alopecia; and betamethasone for vitiligo. A promising treatment for skin cancer “on the horizon,” she said, is the “combination of ablative fractional laser with PD1 inhibitors and chemotherapy.”

Data on AKs

Evidence supporting laser-assisted drug delivery for AKs comes from more than 10 randomized, controlled trials in the dermatology literature involving 400-plus immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. These trials have found ablative fractional laser–assisted PDT to be significantly more efficacious than PDT alone up to 12 months postoperatively and to foster lower rates of AK recurrence.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review, German researchers concluded that PDT combined with ablative laser treatment for AKs is more efficient but not more painful than either therapy alone. They recommended the combined regimen for patients with severe photodamage, field cancerization, and multiple AKs.

In 2020, an international consensus panel of experts, including Dr. Haedersdal, published recommendations regarding laser treatment of traumatic scars and contractures. The panel members determined that laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroids and antimetabolites was recommended for hypertrophic scars and cited triamcinolone acetonide suspension (TAC) as the most common corticosteroid used in combination with ablative fractional lasers. “It can be applied in concentrations of 40 mg/mL or less depending on the degree of hypertrophy,” they wrote.

In addition, they stated that 5-FU solution is “most commonly applied in a concentration of 50 mg/mL alone, or mixed with TAC in ratios of 9:1 or 3:1.”

According to the best available evidence, the clinical approach for hypertrophic scars supports combination treatment with ablative fractional laser and triamcinolone acetonide either alone or in combination with 5-FU. For atrophic scars, laser-assisted delivery of poly-L-lactic acid has been shown to be efficient. “Both of these treatments improve texture and thickness but also dyschromia and scar functionality,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is also a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Boston.

Commenting on patient safety with laser-assisted drug delivery, “the combination of lasers and topicals can be a powerful cocktail,” she said. “You can expect intensified local skin reactions. When treating larger areas, consider the risk of systemic absorption and the risk of potential toxicity. There is also the potential for infection with pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus. The take-home message here is that you should only use the type and amount of drug no higher than administered during intradermal injection.”

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure-Hologic, MiraDry, and PerfAction Technologies. She has also received research grants from Leo Pharma, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, Novoxel, and Venus Concept.

For those who view fractional ablative laser–assisted drug delivery as a pie-in-the-sky procedure that will take years to work its way into routine clinical practice, think again.

According to Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, DMSc, .

“The groundwork has been established over a decade with more than 100 publications available on PubMed,” Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, said during a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy. “There is no doubt that by drilling tiny little holes or channels with ablative fractional lasers, we enhance drug delivery to the skin, and we also empower different topical treatment regimens. Also, laser-assisted drug delivery holds the potential to bring new innovations into established medicine.”

Many studies have demonstrated that clinicians can enhance drug uptake into the skin with the fractional 10,600 nm CO2 laser, the fractional 2,940 nm erbium:YAG laser, and the 1,927 nm thulium laser, but proper tuning of the devices is key. The lower the density, the better, Dr. Haedersdal said.

“Typically, we use 5% density or 5% coverage, sometimes 10%-15%, but don’t go higher in order to avoid the risk of having a systemic uptake,” she said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “Also, the pulse energy for channel depth needs to be tailored to the specific dermatologic disease being treated,” she said, noting that for melasma, for example, “very low pulse energies” would be used, but they would be higher for treating thicker lesions, such as a hypertrophic scar.

Treatment with ablative fractional lasers enhances drug accumulation in the skin of any drug or substance applied to the skin, and clinical indications are expanding rapidly. Established indications include combining ablative fractional lasers and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for AKs and combining ablative fractional lasers and triamcinolone or 5-FU for scars. “Although we have a good body of evidence, particularly for AKs, it’s still an off-label use,” she emphasized.

Evolving indications include concomitant use of ablative fractional laser and vitamins and cosmeceuticals for rejuvenation; lidocaine for local anesthetics; tranexamic acid and hydroquinone for melasma; antifungals for onychomycosis; Botox for hyperhidrosis; minoxidil for alopecia; and betamethasone for vitiligo. A promising treatment for skin cancer “on the horizon,” she said, is the “combination of ablative fractional laser with PD1 inhibitors and chemotherapy.”

Data on AKs

Evidence supporting laser-assisted drug delivery for AKs comes from more than 10 randomized, controlled trials in the dermatology literature involving 400-plus immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. These trials have found ablative fractional laser–assisted PDT to be significantly more efficacious than PDT alone up to 12 months postoperatively and to foster lower rates of AK recurrence.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review, German researchers concluded that PDT combined with ablative laser treatment for AKs is more efficient but not more painful than either therapy alone. They recommended the combined regimen for patients with severe photodamage, field cancerization, and multiple AKs.

In 2020, an international consensus panel of experts, including Dr. Haedersdal, published recommendations regarding laser treatment of traumatic scars and contractures. The panel members determined that laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroids and antimetabolites was recommended for hypertrophic scars and cited triamcinolone acetonide suspension (TAC) as the most common corticosteroid used in combination with ablative fractional lasers. “It can be applied in concentrations of 40 mg/mL or less depending on the degree of hypertrophy,” they wrote.

In addition, they stated that 5-FU solution is “most commonly applied in a concentration of 50 mg/mL alone, or mixed with TAC in ratios of 9:1 or 3:1.”

According to the best available evidence, the clinical approach for hypertrophic scars supports combination treatment with ablative fractional laser and triamcinolone acetonide either alone or in combination with 5-FU. For atrophic scars, laser-assisted delivery of poly-L-lactic acid has been shown to be efficient. “Both of these treatments improve texture and thickness but also dyschromia and scar functionality,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is also a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Boston.

Commenting on patient safety with laser-assisted drug delivery, “the combination of lasers and topicals can be a powerful cocktail,” she said. “You can expect intensified local skin reactions. When treating larger areas, consider the risk of systemic absorption and the risk of potential toxicity. There is also the potential for infection with pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus. The take-home message here is that you should only use the type and amount of drug no higher than administered during intradermal injection.”

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure-Hologic, MiraDry, and PerfAction Technologies. She has also received research grants from Leo Pharma, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, Novoxel, and Venus Concept.

For those who view fractional ablative laser–assisted drug delivery as a pie-in-the-sky procedure that will take years to work its way into routine clinical practice, think again.

According to Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, DMSc, .

“The groundwork has been established over a decade with more than 100 publications available on PubMed,” Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, said during a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy. “There is no doubt that by drilling tiny little holes or channels with ablative fractional lasers, we enhance drug delivery to the skin, and we also empower different topical treatment regimens. Also, laser-assisted drug delivery holds the potential to bring new innovations into established medicine.”

Many studies have demonstrated that clinicians can enhance drug uptake into the skin with the fractional 10,600 nm CO2 laser, the fractional 2,940 nm erbium:YAG laser, and the 1,927 nm thulium laser, but proper tuning of the devices is key. The lower the density, the better, Dr. Haedersdal said.

“Typically, we use 5% density or 5% coverage, sometimes 10%-15%, but don’t go higher in order to avoid the risk of having a systemic uptake,” she said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “Also, the pulse energy for channel depth needs to be tailored to the specific dermatologic disease being treated,” she said, noting that for melasma, for example, “very low pulse energies” would be used, but they would be higher for treating thicker lesions, such as a hypertrophic scar.

Treatment with ablative fractional lasers enhances drug accumulation in the skin of any drug or substance applied to the skin, and clinical indications are expanding rapidly. Established indications include combining ablative fractional lasers and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for AKs and combining ablative fractional lasers and triamcinolone or 5-FU for scars. “Although we have a good body of evidence, particularly for AKs, it’s still an off-label use,” she emphasized.

Evolving indications include concomitant use of ablative fractional laser and vitamins and cosmeceuticals for rejuvenation; lidocaine for local anesthetics; tranexamic acid and hydroquinone for melasma; antifungals for onychomycosis; Botox for hyperhidrosis; minoxidil for alopecia; and betamethasone for vitiligo. A promising treatment for skin cancer “on the horizon,” she said, is the “combination of ablative fractional laser with PD1 inhibitors and chemotherapy.”

Data on AKs

Evidence supporting laser-assisted drug delivery for AKs comes from more than 10 randomized, controlled trials in the dermatology literature involving 400-plus immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. These trials have found ablative fractional laser–assisted PDT to be significantly more efficacious than PDT alone up to 12 months postoperatively and to foster lower rates of AK recurrence.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review, German researchers concluded that PDT combined with ablative laser treatment for AKs is more efficient but not more painful than either therapy alone. They recommended the combined regimen for patients with severe photodamage, field cancerization, and multiple AKs.

In 2020, an international consensus panel of experts, including Dr. Haedersdal, published recommendations regarding laser treatment of traumatic scars and contractures. The panel members determined that laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroids and antimetabolites was recommended for hypertrophic scars and cited triamcinolone acetonide suspension (TAC) as the most common corticosteroid used in combination with ablative fractional lasers. “It can be applied in concentrations of 40 mg/mL or less depending on the degree of hypertrophy,” they wrote.

In addition, they stated that 5-FU solution is “most commonly applied in a concentration of 50 mg/mL alone, or mixed with TAC in ratios of 9:1 or 3:1.”

According to the best available evidence, the clinical approach for hypertrophic scars supports combination treatment with ablative fractional laser and triamcinolone acetonide either alone or in combination with 5-FU. For atrophic scars, laser-assisted delivery of poly-L-lactic acid has been shown to be efficient. “Both of these treatments improve texture and thickness but also dyschromia and scar functionality,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is also a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Boston.

Commenting on patient safety with laser-assisted drug delivery, “the combination of lasers and topicals can be a powerful cocktail,” she said. “You can expect intensified local skin reactions. When treating larger areas, consider the risk of systemic absorption and the risk of potential toxicity. There is also the potential for infection with pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus. The take-home message here is that you should only use the type and amount of drug no higher than administered during intradermal injection.”

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure-Hologic, MiraDry, and PerfAction Technologies. She has also received research grants from Leo Pharma, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, Novoxel, and Venus Concept.

FROM A LASER & AESTHETIC SKIN THERAPY COURSE

What are the risk factors for Mohs surgery–related anxiety?

confirmed by a health care provider (HCP), results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“Higher patient-reported anxiety in hospital settings is significantly linked to lower patient satisfaction with the quality of care and higher patient-reported postoperative pain,” corresponding author Ally-Khan Somani, MD, PhD, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online in Dermatologic Surgery. “Identifying factors associated with perioperative patient anxiety could improve outcomes and patient satisfaction.”

Dr. Somani, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at the University of Indiana, Indianapolis, and coauthors surveyed 145 patients who underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) at the university from February 2018 to March 2020. They collected patient self-reported demographics, medical history, and administered a 10-point visual analog scale assessment of anxiety at multiple stages. They also sought HCP-perceived assessments of anxiety and used a stepwise regression mode to explore factors that potentially contributed to anxiety outcomes. The mean age of the 145 patients was 63 years, 60% were female, and 77% had no self-reported anxiety confirmed by a prior HCP’s diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients (66%) received a pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon, 59% had a history of skin cancer removal surgery, and 86% had 1-2 layers removed during the current MMS.

Prior to MMS, the researchers found that significant risk factors for increased anxiety included younger age, female sex, and self-reported history of anxiety confirmed by an HCP (P < .05), while intraoperatively, HCP-perceived patient anxiety increased with younger patient age and more layers removed. Following MMS, patient anxiety increased significantly with more layers removed and higher self-reported preoperative anxiety levels. “Although existing research is divided regarding the efficacy of pre-MMS consultation for anxiety reduction, these findings suggest that patient-reported and HCP-perceived anxiety were not significantly affected by in-person pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon,” Dr. Somani and colleagues wrote. “Thus, routinely recommending consultations may not be the best approach for improving anxiety outcomes.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of their analysis, including its single-center design, enrollment of demographically similar patients, and the fact that no objective measurements of anxiety such as heart rate or blood pressure were taken.

“One of the main benefits of Mohs surgery is that we are able to operate under local anesthesia, but this also means that our patients are acutely aware of everything going on around them,” said Patricia M. Richey, MD, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and was asked to comment on the study.

“I think it is so important that this study is primarily focusing on the patient experience,” she said. “While this study did not find that a pre-op consult impacted patient anxiety levels, I do think we can infer that it is critical to connect with your patients on some level prior to surgery, as it helps you tailor your process to make the day more tolerable for them [such as] playing music, determining the need for an oral anxiolytic, etc.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Richey reported having financial disclosures.

confirmed by a health care provider (HCP), results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“Higher patient-reported anxiety in hospital settings is significantly linked to lower patient satisfaction with the quality of care and higher patient-reported postoperative pain,” corresponding author Ally-Khan Somani, MD, PhD, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online in Dermatologic Surgery. “Identifying factors associated with perioperative patient anxiety could improve outcomes and patient satisfaction.”

Dr. Somani, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at the University of Indiana, Indianapolis, and coauthors surveyed 145 patients who underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) at the university from February 2018 to March 2020. They collected patient self-reported demographics, medical history, and administered a 10-point visual analog scale assessment of anxiety at multiple stages. They also sought HCP-perceived assessments of anxiety and used a stepwise regression mode to explore factors that potentially contributed to anxiety outcomes. The mean age of the 145 patients was 63 years, 60% were female, and 77% had no self-reported anxiety confirmed by a prior HCP’s diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients (66%) received a pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon, 59% had a history of skin cancer removal surgery, and 86% had 1-2 layers removed during the current MMS.

Prior to MMS, the researchers found that significant risk factors for increased anxiety included younger age, female sex, and self-reported history of anxiety confirmed by an HCP (P < .05), while intraoperatively, HCP-perceived patient anxiety increased with younger patient age and more layers removed. Following MMS, patient anxiety increased significantly with more layers removed and higher self-reported preoperative anxiety levels. “Although existing research is divided regarding the efficacy of pre-MMS consultation for anxiety reduction, these findings suggest that patient-reported and HCP-perceived anxiety were not significantly affected by in-person pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon,” Dr. Somani and colleagues wrote. “Thus, routinely recommending consultations may not be the best approach for improving anxiety outcomes.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of their analysis, including its single-center design, enrollment of demographically similar patients, and the fact that no objective measurements of anxiety such as heart rate or blood pressure were taken.

“One of the main benefits of Mohs surgery is that we are able to operate under local anesthesia, but this also means that our patients are acutely aware of everything going on around them,” said Patricia M. Richey, MD, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and was asked to comment on the study.

“I think it is so important that this study is primarily focusing on the patient experience,” she said. “While this study did not find that a pre-op consult impacted patient anxiety levels, I do think we can infer that it is critical to connect with your patients on some level prior to surgery, as it helps you tailor your process to make the day more tolerable for them [such as] playing music, determining the need for an oral anxiolytic, etc.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Richey reported having financial disclosures.

confirmed by a health care provider (HCP), results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“Higher patient-reported anxiety in hospital settings is significantly linked to lower patient satisfaction with the quality of care and higher patient-reported postoperative pain,” corresponding author Ally-Khan Somani, MD, PhD, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online in Dermatologic Surgery. “Identifying factors associated with perioperative patient anxiety could improve outcomes and patient satisfaction.”

Dr. Somani, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at the University of Indiana, Indianapolis, and coauthors surveyed 145 patients who underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) at the university from February 2018 to March 2020. They collected patient self-reported demographics, medical history, and administered a 10-point visual analog scale assessment of anxiety at multiple stages. They also sought HCP-perceived assessments of anxiety and used a stepwise regression mode to explore factors that potentially contributed to anxiety outcomes. The mean age of the 145 patients was 63 years, 60% were female, and 77% had no self-reported anxiety confirmed by a prior HCP’s diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients (66%) received a pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon, 59% had a history of skin cancer removal surgery, and 86% had 1-2 layers removed during the current MMS.

Prior to MMS, the researchers found that significant risk factors for increased anxiety included younger age, female sex, and self-reported history of anxiety confirmed by an HCP (P < .05), while intraoperatively, HCP-perceived patient anxiety increased with younger patient age and more layers removed. Following MMS, patient anxiety increased significantly with more layers removed and higher self-reported preoperative anxiety levels. “Although existing research is divided regarding the efficacy of pre-MMS consultation for anxiety reduction, these findings suggest that patient-reported and HCP-perceived anxiety were not significantly affected by in-person pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon,” Dr. Somani and colleagues wrote. “Thus, routinely recommending consultations may not be the best approach for improving anxiety outcomes.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of their analysis, including its single-center design, enrollment of demographically similar patients, and the fact that no objective measurements of anxiety such as heart rate or blood pressure were taken.

“One of the main benefits of Mohs surgery is that we are able to operate under local anesthesia, but this also means that our patients are acutely aware of everything going on around them,” said Patricia M. Richey, MD, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and was asked to comment on the study.

“I think it is so important that this study is primarily focusing on the patient experience,” she said. “While this study did not find that a pre-op consult impacted patient anxiety levels, I do think we can infer that it is critical to connect with your patients on some level prior to surgery, as it helps you tailor your process to make the day more tolerable for them [such as] playing music, determining the need for an oral anxiolytic, etc.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Richey reported having financial disclosures.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Pandemic caused treatment delay for half of patients with CTCL, study finds

showed. However, among patients with CTCL diagnosed with COVID-19 during that time, no cases were acquired from outpatient visits.

“Delays in therapy for patients with cutaneous lymphomas should likely be avoided,” two of the study authors, Larisa J. Geskin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, and Bradley D. Kwinta, a medical student at Columbia University, told this news organization in a combined response via email.

“Continuing treatment and maintenance therapy appears critical to avoiding disease progression, highlighting the importance of maintenance therapy in CTCL,” they said. “These patients can be safely treated according to established treatment protocols while practicing physical distancing and using personal protective equipment without significantly increasing their risk of COVID-19 infection.”

The United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer developed emergency guidelines for the management of patients with cutaneous lymphomas during the pandemic to ensure patient safety, and the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas created an International Cutaneous Lymphomas Pandemic Section to collect data to assess the impact of these guidelines.

“Using this data, we can determine if these measures were effective in preventing COVID-19 infection, what the impact was of maintenance therapy, and how delays in treatment affected disease outcomes in CTCL patients,” the authors and their colleagues wrote in the study, which was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

They retrospectively analyzed data from the electronic medical records of 149 patients with CTCL who were being managed at one of nine international academic medical centers in seven countries from March to October 2020. Slightly more than half (56%) were male, 70% were White, 18% were Black, 52% had stage IA-IIA disease, and 19% acquired COVID-19 during the study period.

Of the 149 patients, 79 (53%) experienced a mean treatment delay of 3.2 months (range, 10 days to 10 months). After adjusting for age, race, biological sex, COVID-19 status, and disease stage, treatment delay was associated with a significant risk of disease relapse or progression across all stages (odds ratio, 5.00; P < .001). Specifically, for each additional month that a patient experienced treatment delay, the odds of disease progression increased by 37% (OR, 1.37; P < .001).

A total of 28 patients with CTCL (19%) were diagnosed with COVID-19, but none were acquired from outpatient office visits. Patients who contracted COVID-19 did not have a statistically significant increase in odds of disease progression, compared with COVID-negative patients (OR, 0.41; P = .07).

According to Dr. Geskin, who is also director of the Comprehensive Skin Cancer Center in the division of cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at Columbia, and Mr. Kwinta, no clinical trials exist to inform maintenance protocols in patients with cutaneous lymphomas. “There are also no randomized and controlled observational studies that demonstrate the impact that therapy delay may have on disease outcomes,” they said in the email. “In fact, the need for maintenance therapy for CTCL is often debated. Our findings demonstrate the importance of continuing treatment and the use of maintenance therapy in avoiding disease progression in these incurable lymphomas.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective observational design. “Therefore, we cannot establish a definitive causal link between treatment delay and disease progression,” they said. “Our cohort of patients were on various and often multiple therapies, making it hard to extrapolate our data to discern which maintenance therapies were most effective in preventing disease progression.”

In addition, their data only includes patients from March to October 2020, “before the discovery of new variants and the development of COVID-19 vaccines,” they added. “Additional studies would be required to draw conclusions on how COVID-19 vaccines may affect patients with CTCL, including outcomes in the setting of new variants.”

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

showed. However, among patients with CTCL diagnosed with COVID-19 during that time, no cases were acquired from outpatient visits.

“Delays in therapy for patients with cutaneous lymphomas should likely be avoided,” two of the study authors, Larisa J. Geskin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, and Bradley D. Kwinta, a medical student at Columbia University, told this news organization in a combined response via email.

“Continuing treatment and maintenance therapy appears critical to avoiding disease progression, highlighting the importance of maintenance therapy in CTCL,” they said. “These patients can be safely treated according to established treatment protocols while practicing physical distancing and using personal protective equipment without significantly increasing their risk of COVID-19 infection.”

The United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer developed emergency guidelines for the management of patients with cutaneous lymphomas during the pandemic to ensure patient safety, and the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas created an International Cutaneous Lymphomas Pandemic Section to collect data to assess the impact of these guidelines.

“Using this data, we can determine if these measures were effective in preventing COVID-19 infection, what the impact was of maintenance therapy, and how delays in treatment affected disease outcomes in CTCL patients,” the authors and their colleagues wrote in the study, which was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

They retrospectively analyzed data from the electronic medical records of 149 patients with CTCL who were being managed at one of nine international academic medical centers in seven countries from March to October 2020. Slightly more than half (56%) were male, 70% were White, 18% were Black, 52% had stage IA-IIA disease, and 19% acquired COVID-19 during the study period.

Of the 149 patients, 79 (53%) experienced a mean treatment delay of 3.2 months (range, 10 days to 10 months). After adjusting for age, race, biological sex, COVID-19 status, and disease stage, treatment delay was associated with a significant risk of disease relapse or progression across all stages (odds ratio, 5.00; P < .001). Specifically, for each additional month that a patient experienced treatment delay, the odds of disease progression increased by 37% (OR, 1.37; P < .001).

A total of 28 patients with CTCL (19%) were diagnosed with COVID-19, but none were acquired from outpatient office visits. Patients who contracted COVID-19 did not have a statistically significant increase in odds of disease progression, compared with COVID-negative patients (OR, 0.41; P = .07).

According to Dr. Geskin, who is also director of the Comprehensive Skin Cancer Center in the division of cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at Columbia, and Mr. Kwinta, no clinical trials exist to inform maintenance protocols in patients with cutaneous lymphomas. “There are also no randomized and controlled observational studies that demonstrate the impact that therapy delay may have on disease outcomes,” they said in the email. “In fact, the need for maintenance therapy for CTCL is often debated. Our findings demonstrate the importance of continuing treatment and the use of maintenance therapy in avoiding disease progression in these incurable lymphomas.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective observational design. “Therefore, we cannot establish a definitive causal link between treatment delay and disease progression,” they said. “Our cohort of patients were on various and often multiple therapies, making it hard to extrapolate our data to discern which maintenance therapies were most effective in preventing disease progression.”

In addition, their data only includes patients from March to October 2020, “before the discovery of new variants and the development of COVID-19 vaccines,” they added. “Additional studies would be required to draw conclusions on how COVID-19 vaccines may affect patients with CTCL, including outcomes in the setting of new variants.”

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

showed. However, among patients with CTCL diagnosed with COVID-19 during that time, no cases were acquired from outpatient visits.

“Delays in therapy for patients with cutaneous lymphomas should likely be avoided,” two of the study authors, Larisa J. Geskin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, and Bradley D. Kwinta, a medical student at Columbia University, told this news organization in a combined response via email.

“Continuing treatment and maintenance therapy appears critical to avoiding disease progression, highlighting the importance of maintenance therapy in CTCL,” they said. “These patients can be safely treated according to established treatment protocols while practicing physical distancing and using personal protective equipment without significantly increasing their risk of COVID-19 infection.”

The United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer developed emergency guidelines for the management of patients with cutaneous lymphomas during the pandemic to ensure patient safety, and the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas created an International Cutaneous Lymphomas Pandemic Section to collect data to assess the impact of these guidelines.

“Using this data, we can determine if these measures were effective in preventing COVID-19 infection, what the impact was of maintenance therapy, and how delays in treatment affected disease outcomes in CTCL patients,” the authors and their colleagues wrote in the study, which was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

They retrospectively analyzed data from the electronic medical records of 149 patients with CTCL who were being managed at one of nine international academic medical centers in seven countries from March to October 2020. Slightly more than half (56%) were male, 70% were White, 18% were Black, 52% had stage IA-IIA disease, and 19% acquired COVID-19 during the study period.

Of the 149 patients, 79 (53%) experienced a mean treatment delay of 3.2 months (range, 10 days to 10 months). After adjusting for age, race, biological sex, COVID-19 status, and disease stage, treatment delay was associated with a significant risk of disease relapse or progression across all stages (odds ratio, 5.00; P < .001). Specifically, for each additional month that a patient experienced treatment delay, the odds of disease progression increased by 37% (OR, 1.37; P < .001).

A total of 28 patients with CTCL (19%) were diagnosed with COVID-19, but none were acquired from outpatient office visits. Patients who contracted COVID-19 did not have a statistically significant increase in odds of disease progression, compared with COVID-negative patients (OR, 0.41; P = .07).

According to Dr. Geskin, who is also director of the Comprehensive Skin Cancer Center in the division of cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at Columbia, and Mr. Kwinta, no clinical trials exist to inform maintenance protocols in patients with cutaneous lymphomas. “There are also no randomized and controlled observational studies that demonstrate the impact that therapy delay may have on disease outcomes,” they said in the email. “In fact, the need for maintenance therapy for CTCL is often debated. Our findings demonstrate the importance of continuing treatment and the use of maintenance therapy in avoiding disease progression in these incurable lymphomas.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective observational design. “Therefore, we cannot establish a definitive causal link between treatment delay and disease progression,” they said. “Our cohort of patients were on various and often multiple therapies, making it hard to extrapolate our data to discern which maintenance therapies were most effective in preventing disease progression.”

In addition, their data only includes patients from March to October 2020, “before the discovery of new variants and the development of COVID-19 vaccines,” they added. “Additional studies would be required to draw conclusions on how COVID-19 vaccines may affect patients with CTCL, including outcomes in the setting of new variants.”

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

DEI advances in dermatology unremarkable to date, studies find

suggest.

To evaluate diversity and career goals of graduating allopathic medical students pursuing careers in dermatology, corresponding author Matthew Mansh, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues drew from the 2016-2019 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire for their study. The main outcome measures were the proportion of female students, students from racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in medicine (URM), and sexual minority (SM) students pursuing dermatology versus those pursuing other specialties, as well as the proportions and multivariable adjusted odds of intended career goals between students pursuing dermatology and those pursuing other specialties, and by sex, race, and ethnicity, and sexual orientation among students pursuing dermatology.

Of the 58,077 graduating students, 49% were women, 15% were URM, and 6% were SM. The researchers found that women pursuing dermatology were significantly less likely than women pursuing other specialties to identify as URM (11.6% vs. 17.2%; P < .001) or SM (1.9% vs. 5.7%; P < .001).

In multivariable-adjusted analyses of all students, those pursuing dermatology compared with other specialties had decreased odds of intending to care for underserved populations (18.3% vs. 34%; adjusted odd ratio, 0.40; P < .001), practice in underserved areas (12.7% vs. 25.9%; aOR, 0.40; P < .001), and practice public health (17% vs. 30.2%; aOR, 0.44; P < .001). The odds for pursuing research in their careers was greater among those pursuing dermatology (64.7% vs. 51.7%; aOR, 1.76; P < .001).

“Addressing health inequities and improving care for underserved patients is the responsibility of all dermatologists, and efforts are needed to increase diversity and interest in careers focused on underserved care among trainees in the dermatology workforce pipeline,” the authors concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including lack of data delineating sex, sex assigned at birth, and gender identity, and lack of intersectional analyses between multiple minority identities and multiple career goals. “Importantly, diversity factors and their relationship to underserved care is likely multidimensional, and many students pursuing dermatology identified with multiple minority identities, highlighting the need for future studies focused on intersectionality,” they wrote.

Trends over 15 years

In a separate study, Jazzmin C. Williams, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, and coauthors drew from an Association of American Medical Colleges report of trainees’ and applicants’ self-reported race and ethnicity by specialty from 2005 to 2020 to evaluate diversity trends over the 15-year period. They found that Black and Latinx trainees were underrepresented in all specialties, but even more so in dermatology (mean annual rate ratios of 0.32 and 0.14, respectively), compared with those in primary care (mean annual RRs of 0.54 and 0.23) and those in specialty care (mean annual RRs of 0.39 and 0.18).

In other findings, the annual representation of Black trainees remained unchanged in dermatology between 2005 and 2020, but down-trended for primary (P < .001) and specialty care (P = .001). At the same time, representation of Latinx trainees remained unchanged in dermatology and specialty care but increased in primary care (P < .001). Finally, Black and Latinx race and ethnicity comprised a lower mean proportion of matriculating dermatology trainees (postgraduate year-2s) compared with annual dermatology applicants (4.01% vs. 5.97%, respectively, and 2.06% vs. 6.37% among Latinx; P < .001 for all associations).

“Much of these disparities can be attributed to the leaky pipeline – the disproportionate, stepwise reduction in racial and ethnic minority representation along the path to medicine,” the authors wrote. “This leaky pipeline is the direct result of structural racism, which includes, but is not limited to, historical and contemporary economic disinvestment from majority-minority schools, kindergarten through grade 12.” They concluded by stating that “dermatologists must intervene throughout the educational pipeline, including residency selection and mentorship, to effectively increase diversity.”

Solutions to address diversity

In an editorial accompanying the two studies published in the same issue of JAMA Dermatology, Ellen N. Pritchett, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and Andrew J. Park, MD, MBA, and Rebecca Vasquez, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, offered several solutions to address diversity in the dermatology work force. They include:

Go beyond individual bias in recruitment. “A residency selection framework that meaningfully incorporates diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) will require more than strategies that address individual bias,” they wrote. “Departmental recruitment committees must become familiar with systems that serve to perpetuate individual bias, like institutional racism or practices that disproportionately favor non-URM versus URM individuals.”

Challenge the myth of meritocracy. “The inaccurate notion of meritocracy – that success purely derives from individual effort has become the foundation of residency selection,” the authors wrote. “Unfortunately, this view ignores the inequitably distributed sociostructural resources that limit the rewards of individual effort.”

Avoid tokenism in retention strategies. Tokenism, which they defined as “a symbolic addition of members from a marginalized group to give the impression of social inclusiveness and diversity without meaningful incorporation of DEI in the policies, processes, and culture,” can lead to depression, burnout, and attrition, they wrote. They advise leaders of dermatology departments to “review their residency selection framework to ensure that it allows for meaningful representation, inclusion, and equity among trainees and faculty to better support URM individuals at all levels.”

Omar N. Qutub, MD, a Portland, Ore.–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the studies, characterized the findings by Dr. Mansh and colleagues as sobering. “It appears that there is work to do as far as improving diversity in the dermatology workforce that will likely benefit greatly from an honest and steadfast approach to equitable application standards as well as mentorship during all stages of the application process,” such as medical school and residency, said Dr. Qutub, who is the director of equity, diversity, and inclusion of the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “With a focused attempt, we are likely to matriculate more racial minorities into our residency programs, maximizing patient outcomes.”

As for the study by Ms. Williams and colleagues, he told this news organization that efforts toward recruiting URM students as well as sexual minority students “is likely to not only improve health inequities in underserved areas, but will also enrich the specialty as a whole, allowing for better understanding of our diverse patient population and [for us to] to deliver quality care more readily for people and in areas where the focus has often been limited.”

In an interview, Chesahna Kindred, MD, a Columbia, Md.–based dermatologist and immediate past chair of the National Medical Association dermatology section, pointed out that the number of Black physicians in the United States has increased by only 4% in the last 120 years. The study by Dr. Mansh and colleagues, she commented, “underscores what I’ve recognized in the last couple of years: Where are the Black male dermatologists? NMA Derm started recruiting this demographic aggressively about a year ago and started the Black Men in Derm events. Black male members of NMA Derm travel to the Student National Medical Association and NMA conference and hold a panel to expose Black male students into dermatology. This article provides the numbers needed to measure how successful this and other programs are to closing the equity gap.”

Ms. Williams reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Mansh reported receiving grants from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Pritchett and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures, as did Dr. Qutub and Dr. Kindred.

suggest.

To evaluate diversity and career goals of graduating allopathic medical students pursuing careers in dermatology, corresponding author Matthew Mansh, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues drew from the 2016-2019 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire for their study. The main outcome measures were the proportion of female students, students from racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in medicine (URM), and sexual minority (SM) students pursuing dermatology versus those pursuing other specialties, as well as the proportions and multivariable adjusted odds of intended career goals between students pursuing dermatology and those pursuing other specialties, and by sex, race, and ethnicity, and sexual orientation among students pursuing dermatology.

Of the 58,077 graduating students, 49% were women, 15% were URM, and 6% were SM. The researchers found that women pursuing dermatology were significantly less likely than women pursuing other specialties to identify as URM (11.6% vs. 17.2%; P < .001) or SM (1.9% vs. 5.7%; P < .001).

In multivariable-adjusted analyses of all students, those pursuing dermatology compared with other specialties had decreased odds of intending to care for underserved populations (18.3% vs. 34%; adjusted odd ratio, 0.40; P < .001), practice in underserved areas (12.7% vs. 25.9%; aOR, 0.40; P < .001), and practice public health (17% vs. 30.2%; aOR, 0.44; P < .001). The odds for pursuing research in their careers was greater among those pursuing dermatology (64.7% vs. 51.7%; aOR, 1.76; P < .001).

“Addressing health inequities and improving care for underserved patients is the responsibility of all dermatologists, and efforts are needed to increase diversity and interest in careers focused on underserved care among trainees in the dermatology workforce pipeline,” the authors concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including lack of data delineating sex, sex assigned at birth, and gender identity, and lack of intersectional analyses between multiple minority identities and multiple career goals. “Importantly, diversity factors and their relationship to underserved care is likely multidimensional, and many students pursuing dermatology identified with multiple minority identities, highlighting the need for future studies focused on intersectionality,” they wrote.

Trends over 15 years

In a separate study, Jazzmin C. Williams, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, and coauthors drew from an Association of American Medical Colleges report of trainees’ and applicants’ self-reported race and ethnicity by specialty from 2005 to 2020 to evaluate diversity trends over the 15-year period. They found that Black and Latinx trainees were underrepresented in all specialties, but even more so in dermatology (mean annual rate ratios of 0.32 and 0.14, respectively), compared with those in primary care (mean annual RRs of 0.54 and 0.23) and those in specialty care (mean annual RRs of 0.39 and 0.18).

In other findings, the annual representation of Black trainees remained unchanged in dermatology between 2005 and 2020, but down-trended for primary (P < .001) and specialty care (P = .001). At the same time, representation of Latinx trainees remained unchanged in dermatology and specialty care but increased in primary care (P < .001). Finally, Black and Latinx race and ethnicity comprised a lower mean proportion of matriculating dermatology trainees (postgraduate year-2s) compared with annual dermatology applicants (4.01% vs. 5.97%, respectively, and 2.06% vs. 6.37% among Latinx; P < .001 for all associations).

“Much of these disparities can be attributed to the leaky pipeline – the disproportionate, stepwise reduction in racial and ethnic minority representation along the path to medicine,” the authors wrote. “This leaky pipeline is the direct result of structural racism, which includes, but is not limited to, historical and contemporary economic disinvestment from majority-minority schools, kindergarten through grade 12.” They concluded by stating that “dermatologists must intervene throughout the educational pipeline, including residency selection and mentorship, to effectively increase diversity.”

Solutions to address diversity

In an editorial accompanying the two studies published in the same issue of JAMA Dermatology, Ellen N. Pritchett, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and Andrew J. Park, MD, MBA, and Rebecca Vasquez, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, offered several solutions to address diversity in the dermatology work force. They include:

Go beyond individual bias in recruitment. “A residency selection framework that meaningfully incorporates diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) will require more than strategies that address individual bias,” they wrote. “Departmental recruitment committees must become familiar with systems that serve to perpetuate individual bias, like institutional racism or practices that disproportionately favor non-URM versus URM individuals.”

Challenge the myth of meritocracy. “The inaccurate notion of meritocracy – that success purely derives from individual effort has become the foundation of residency selection,” the authors wrote. “Unfortunately, this view ignores the inequitably distributed sociostructural resources that limit the rewards of individual effort.”

Avoid tokenism in retention strategies. Tokenism, which they defined as “a symbolic addition of members from a marginalized group to give the impression of social inclusiveness and diversity without meaningful incorporation of DEI in the policies, processes, and culture,” can lead to depression, burnout, and attrition, they wrote. They advise leaders of dermatology departments to “review their residency selection framework to ensure that it allows for meaningful representation, inclusion, and equity among trainees and faculty to better support URM individuals at all levels.”

Omar N. Qutub, MD, a Portland, Ore.–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the studies, characterized the findings by Dr. Mansh and colleagues as sobering. “It appears that there is work to do as far as improving diversity in the dermatology workforce that will likely benefit greatly from an honest and steadfast approach to equitable application standards as well as mentorship during all stages of the application process,” such as medical school and residency, said Dr. Qutub, who is the director of equity, diversity, and inclusion of the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “With a focused attempt, we are likely to matriculate more racial minorities into our residency programs, maximizing patient outcomes.”

As for the study by Ms. Williams and colleagues, he told this news organization that efforts toward recruiting URM students as well as sexual minority students “is likely to not only improve health inequities in underserved areas, but will also enrich the specialty as a whole, allowing for better understanding of our diverse patient population and [for us to] to deliver quality care more readily for people and in areas where the focus has often been limited.”

In an interview, Chesahna Kindred, MD, a Columbia, Md.–based dermatologist and immediate past chair of the National Medical Association dermatology section, pointed out that the number of Black physicians in the United States has increased by only 4% in the last 120 years. The study by Dr. Mansh and colleagues, she commented, “underscores what I’ve recognized in the last couple of years: Where are the Black male dermatologists? NMA Derm started recruiting this demographic aggressively about a year ago and started the Black Men in Derm events. Black male members of NMA Derm travel to the Student National Medical Association and NMA conference and hold a panel to expose Black male students into dermatology. This article provides the numbers needed to measure how successful this and other programs are to closing the equity gap.”

Ms. Williams reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Mansh reported receiving grants from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Pritchett and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures, as did Dr. Qutub and Dr. Kindred.

suggest.

To evaluate diversity and career goals of graduating allopathic medical students pursuing careers in dermatology, corresponding author Matthew Mansh, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues drew from the 2016-2019 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire for their study. The main outcome measures were the proportion of female students, students from racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in medicine (URM), and sexual minority (SM) students pursuing dermatology versus those pursuing other specialties, as well as the proportions and multivariable adjusted odds of intended career goals between students pursuing dermatology and those pursuing other specialties, and by sex, race, and ethnicity, and sexual orientation among students pursuing dermatology.

Of the 58,077 graduating students, 49% were women, 15% were URM, and 6% were SM. The researchers found that women pursuing dermatology were significantly less likely than women pursuing other specialties to identify as URM (11.6% vs. 17.2%; P < .001) or SM (1.9% vs. 5.7%; P < .001).

In multivariable-adjusted analyses of all students, those pursuing dermatology compared with other specialties had decreased odds of intending to care for underserved populations (18.3% vs. 34%; adjusted odd ratio, 0.40; P < .001), practice in underserved areas (12.7% vs. 25.9%; aOR, 0.40; P < .001), and practice public health (17% vs. 30.2%; aOR, 0.44; P < .001). The odds for pursuing research in their careers was greater among those pursuing dermatology (64.7% vs. 51.7%; aOR, 1.76; P < .001).

“Addressing health inequities and improving care for underserved patients is the responsibility of all dermatologists, and efforts are needed to increase diversity and interest in careers focused on underserved care among trainees in the dermatology workforce pipeline,” the authors concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including lack of data delineating sex, sex assigned at birth, and gender identity, and lack of intersectional analyses between multiple minority identities and multiple career goals. “Importantly, diversity factors and their relationship to underserved care is likely multidimensional, and many students pursuing dermatology identified with multiple minority identities, highlighting the need for future studies focused on intersectionality,” they wrote.

Trends over 15 years

In a separate study, Jazzmin C. Williams, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, and coauthors drew from an Association of American Medical Colleges report of trainees’ and applicants’ self-reported race and ethnicity by specialty from 2005 to 2020 to evaluate diversity trends over the 15-year period. They found that Black and Latinx trainees were underrepresented in all specialties, but even more so in dermatology (mean annual rate ratios of 0.32 and 0.14, respectively), compared with those in primary care (mean annual RRs of 0.54 and 0.23) and those in specialty care (mean annual RRs of 0.39 and 0.18).

In other findings, the annual representation of Black trainees remained unchanged in dermatology between 2005 and 2020, but down-trended for primary (P < .001) and specialty care (P = .001). At the same time, representation of Latinx trainees remained unchanged in dermatology and specialty care but increased in primary care (P < .001). Finally, Black and Latinx race and ethnicity comprised a lower mean proportion of matriculating dermatology trainees (postgraduate year-2s) compared with annual dermatology applicants (4.01% vs. 5.97%, respectively, and 2.06% vs. 6.37% among Latinx; P < .001 for all associations).

“Much of these disparities can be attributed to the leaky pipeline – the disproportionate, stepwise reduction in racial and ethnic minority representation along the path to medicine,” the authors wrote. “This leaky pipeline is the direct result of structural racism, which includes, but is not limited to, historical and contemporary economic disinvestment from majority-minority schools, kindergarten through grade 12.” They concluded by stating that “dermatologists must intervene throughout the educational pipeline, including residency selection and mentorship, to effectively increase diversity.”

Solutions to address diversity

In an editorial accompanying the two studies published in the same issue of JAMA Dermatology, Ellen N. Pritchett, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and Andrew J. Park, MD, MBA, and Rebecca Vasquez, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, offered several solutions to address diversity in the dermatology work force. They include:

Go beyond individual bias in recruitment. “A residency selection framework that meaningfully incorporates diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) will require more than strategies that address individual bias,” they wrote. “Departmental recruitment committees must become familiar with systems that serve to perpetuate individual bias, like institutional racism or practices that disproportionately favor non-URM versus URM individuals.”

Challenge the myth of meritocracy. “The inaccurate notion of meritocracy – that success purely derives from individual effort has become the foundation of residency selection,” the authors wrote. “Unfortunately, this view ignores the inequitably distributed sociostructural resources that limit the rewards of individual effort.”

Avoid tokenism in retention strategies. Tokenism, which they defined as “a symbolic addition of members from a marginalized group to give the impression of social inclusiveness and diversity without meaningful incorporation of DEI in the policies, processes, and culture,” can lead to depression, burnout, and attrition, they wrote. They advise leaders of dermatology departments to “review their residency selection framework to ensure that it allows for meaningful representation, inclusion, and equity among trainees and faculty to better support URM individuals at all levels.”

Omar N. Qutub, MD, a Portland, Ore.–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the studies, characterized the findings by Dr. Mansh and colleagues as sobering. “It appears that there is work to do as far as improving diversity in the dermatology workforce that will likely benefit greatly from an honest and steadfast approach to equitable application standards as well as mentorship during all stages of the application process,” such as medical school and residency, said Dr. Qutub, who is the director of equity, diversity, and inclusion of the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “With a focused attempt, we are likely to matriculate more racial minorities into our residency programs, maximizing patient outcomes.”

As for the study by Ms. Williams and colleagues, he told this news organization that efforts toward recruiting URM students as well as sexual minority students “is likely to not only improve health inequities in underserved areas, but will also enrich the specialty as a whole, allowing for better understanding of our diverse patient population and [for us to] to deliver quality care more readily for people and in areas where the focus has often been limited.”

In an interview, Chesahna Kindred, MD, a Columbia, Md.–based dermatologist and immediate past chair of the National Medical Association dermatology section, pointed out that the number of Black physicians in the United States has increased by only 4% in the last 120 years. The study by Dr. Mansh and colleagues, she commented, “underscores what I’ve recognized in the last couple of years: Where are the Black male dermatologists? NMA Derm started recruiting this demographic aggressively about a year ago and started the Black Men in Derm events. Black male members of NMA Derm travel to the Student National Medical Association and NMA conference and hold a panel to expose Black male students into dermatology. This article provides the numbers needed to measure how successful this and other programs are to closing the equity gap.”

Ms. Williams reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Mansh reported receiving grants from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Pritchett and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures, as did Dr. Qutub and Dr. Kindred.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Consider radiologic imaging for high-risk cutaneous SCC, expert advises

DENVER –

In a study published in 2020, Emily Ruiz, MD, MPH, and colleagues identified 87 CSCC tumors in 83 patients who underwent baseline or surveillance imaging primary at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Mohs Surgery Clinic and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic, both in Boston, from Jan. 1, 2017, to June 1, 2019. Of the 87 primary CSCCs, 48 (58%) underwent surveillance imaging. The researchers found that imaging detected additional disease in 26 patients, or 30% of cases, “whether that be nodal metastasis, local invasion beyond what was clinically accepted, or in-transit disease,” Dr. Ruiz, academic director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center at Brigham and Women’s, said during the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. “But if you look at the 16 nodal metastases in this cohort, all were picked up on imaging and not on clinical exam.”

Since publication of these results, Dr. Ruiz routinely considers baseline radiologic imaging in T2b and T3 tumors; borderline T2a tumors (which she said they are now calling “T2a high,” for those who have one risk factor plus another intermediate risk factor),” and T2a tumors in patients who are profoundly immunosuppressed.

“My preference is to always do [the imaging] before treatment unless I’m up-staging them during surgery,” said Dr. Ruiz, who also directs the High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at Dana Farber. “We have picked up nodal metastases before surgery, which enables us to create a good therapeutic plan for our patients before we start operating. Then we image them every 6 months or so for about 2 years. Sometimes we will extend that out to 3 years.”

Some clinicians use sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a diagnostic test, but there are mixed results about its prognostic significance. A retrospective observational study of 720 patients with CSCC found that SLNB provided no benefit regarding further metastasis or tumor-specific survival, compared with those who received routine observation and follow-up, “but head and neck surgeons in the U.S. are putting together some prospective data from multiple centers,” Dr. Ruiz said. “I think in the coming years, you will have more multicenter data to inform us as to whether to do SLNB or not.”