User login

Doug Brunk is a San Diego-based award-winning reporter who began covering health care in 1991. Before joining the company, he wrote for the health sciences division of Columbia University and was an associate editor at Contemporary Long Term Care magazine when it won a Jesse H. Neal Award. His work has been syndicated by the Los Angeles Times and he is the author of two books related to the University of Kentucky Wildcats men's basketball program. Doug has a master’s degree in magazine journalism from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Follow him on Twitter @dougbrunk.

Chest-worn seizure detection device shows promise

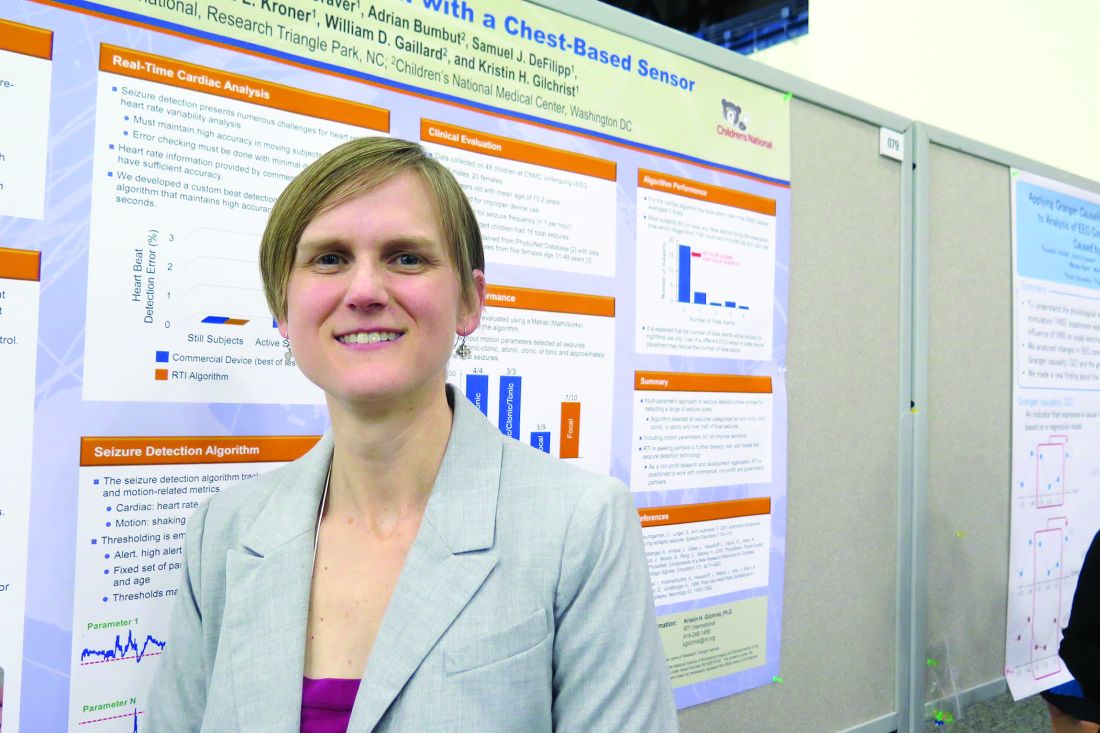

HOUSTON – An investigative, chest-worn device shows promise for detecting a wide range of seizure types in children with epilepsy, results from a small single-center study showed.

“Our goal is for parents to have more peace of mind, not feeling like they have to watch their kids all night long,” one of the study authors, Kristin H. Gilchrist, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “There are currently many wearable devices marketed for fitness [purposes], but if we can leverage some of these heart rate monitors and use them to detect seizures with specialized algorithms, that would be ideal.”

Approximately 60% of patients had a seizure during the monitoring period. Seizures without any clinical response or those lasting less than 10 seconds (such as single myoclonic jerks or clusters) were excluded from analysis, as were subjects with multiple seizures per hour because the autonomic signals often did not return to baseline, and this seizure frequency is outside of the intended use of the monitor. After exclusions, the algorithm was evaluated on 10 children with a mean age of 12 years. For additional validation, the algorithm was also evaluated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, PhysioNet database with ECG from five adults with partial seizures (Neurology. 1999;53:1590-2).The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3/9 and 7/10 of focal seizures from the CNMC and MIT subjects, respectively. In the CNMC dataset, the motion algorithm detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3), half of those categorized as atonic/clonic/tonic (2/4), and one of nine classified as focal seizures.

In the CNMC dataset, false positives averaged one per 14 hours, however, the majority of false positives occurred in a few patients with poor sensor data quality. More than half of the subjects (70%) had no false positives. One false positive occurred in the 16.8 hours of MIT data.

“In addition to an alert application, we have a technology that can be beneficial to clinic-based studies to quantify how many seizures people are having,” Dr. Gilchrist said. “Hopefully someday it will reach the commercial market.” She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – An investigative, chest-worn device shows promise for detecting a wide range of seizure types in children with epilepsy, results from a small single-center study showed.

“Our goal is for parents to have more peace of mind, not feeling like they have to watch their kids all night long,” one of the study authors, Kristin H. Gilchrist, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “There are currently many wearable devices marketed for fitness [purposes], but if we can leverage some of these heart rate monitors and use them to detect seizures with specialized algorithms, that would be ideal.”

Approximately 60% of patients had a seizure during the monitoring period. Seizures without any clinical response or those lasting less than 10 seconds (such as single myoclonic jerks or clusters) were excluded from analysis, as were subjects with multiple seizures per hour because the autonomic signals often did not return to baseline, and this seizure frequency is outside of the intended use of the monitor. After exclusions, the algorithm was evaluated on 10 children with a mean age of 12 years. For additional validation, the algorithm was also evaluated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, PhysioNet database with ECG from five adults with partial seizures (Neurology. 1999;53:1590-2).The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3/9 and 7/10 of focal seizures from the CNMC and MIT subjects, respectively. In the CNMC dataset, the motion algorithm detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3), half of those categorized as atonic/clonic/tonic (2/4), and one of nine classified as focal seizures.

In the CNMC dataset, false positives averaged one per 14 hours, however, the majority of false positives occurred in a few patients with poor sensor data quality. More than half of the subjects (70%) had no false positives. One false positive occurred in the 16.8 hours of MIT data.

“In addition to an alert application, we have a technology that can be beneficial to clinic-based studies to quantify how many seizures people are having,” Dr. Gilchrist said. “Hopefully someday it will reach the commercial market.” She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – An investigative, chest-worn device shows promise for detecting a wide range of seizure types in children with epilepsy, results from a small single-center study showed.

“Our goal is for parents to have more peace of mind, not feeling like they have to watch their kids all night long,” one of the study authors, Kristin H. Gilchrist, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “There are currently many wearable devices marketed for fitness [purposes], but if we can leverage some of these heart rate monitors and use them to detect seizures with specialized algorithms, that would be ideal.”

Approximately 60% of patients had a seizure during the monitoring period. Seizures without any clinical response or those lasting less than 10 seconds (such as single myoclonic jerks or clusters) were excluded from analysis, as were subjects with multiple seizures per hour because the autonomic signals often did not return to baseline, and this seizure frequency is outside of the intended use of the monitor. After exclusions, the algorithm was evaluated on 10 children with a mean age of 12 years. For additional validation, the algorithm was also evaluated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, PhysioNet database with ECG from five adults with partial seizures (Neurology. 1999;53:1590-2).The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3/9 and 7/10 of focal seizures from the CNMC and MIT subjects, respectively. In the CNMC dataset, the motion algorithm detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3), half of those categorized as atonic/clonic/tonic (2/4), and one of nine classified as focal seizures.

In the CNMC dataset, false positives averaged one per 14 hours, however, the majority of false positives occurred in a few patients with poor sensor data quality. More than half of the subjects (70%) had no false positives. One false positive occurred in the 16.8 hours of MIT data.

“In addition to an alert application, we have a technology that can be beneficial to clinic-based studies to quantify how many seizures people are having,” Dr. Gilchrist said. “Hopefully someday it will reach the commercial market.” She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3 of 9 classified as focal seizures.

Data source: A clinic-based study of 10 epilepsy patients with a mean age of 12 years who wore an investigative device to detect seizures.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gilchrist reported having no financial disclosures.

Study highlights need to address vitamin D deficiency in epilepsy patients

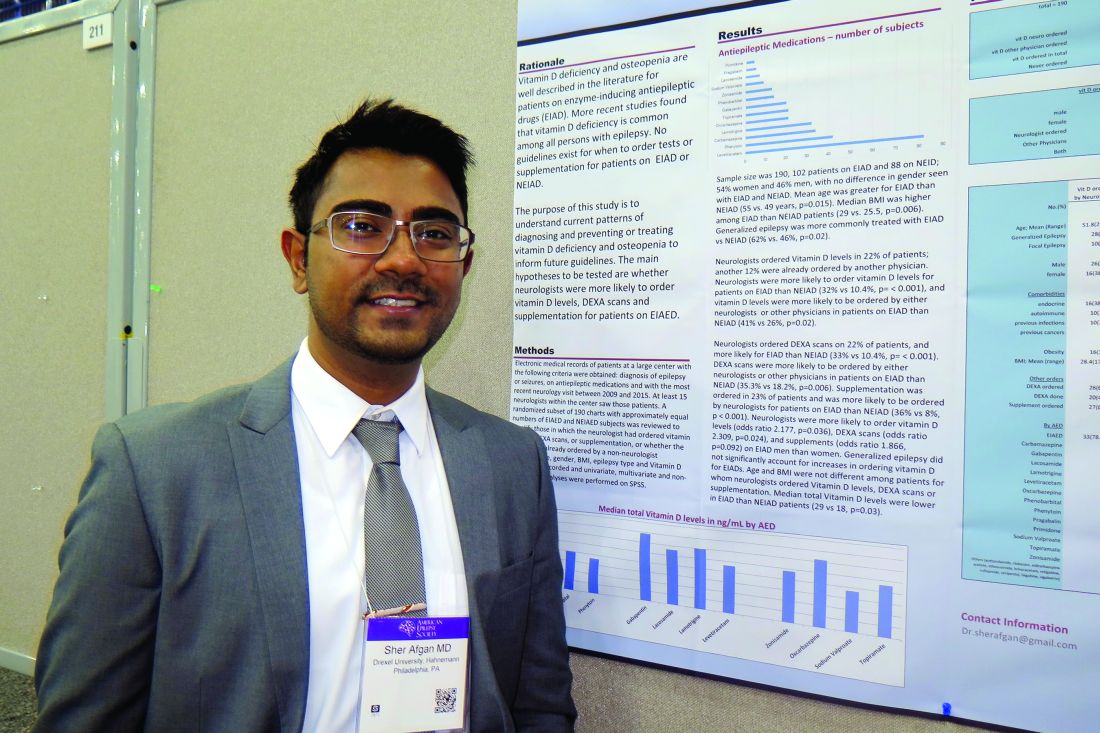

HOUSTON – Neurologists and other clinicians ordered vitamin D levels, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, and vitamin D supplementation for epilepsy patients in order to diagnose and prevent vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia, results from a single-center study showed.

Vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia are well described in the literature for patients on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (EIADs), but no guidelines currently exist for when to order tests or supplementation for patients on EIADs or non–enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs (NEIADs). “Further studies with larger sample sizes will be helpful in order to establish guidelines for neurologists and other physicians,” Sher Afgan, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Afgan, a research assistant at Drexel, went on to report that neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% had already been ordered by another physician. Neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (32% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001), and vitamin D levels were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (41% vs. 26%; P = .02). Neurologists ordered DXA scans in 22% of patients, and more often for those on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (33% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001). Similarly, DXA scans were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (35.3% vs. 18.2%; P = .006). Supplementation was ordered in 23% of patients and was more likely to be ordered by neurologists for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (36% vs. 8%; P less than .001).

The researchers also found that neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels, DXA scans, and supplements for men on EIADs, compared with women on EIADs (odds ratio, 2.178, P = .03; OR, 2.31, P = .02; OR, 1.87, P = .09, respectively). Generalized epilepsy did not significantly account for increases in ordering vitamin D for EIADs. Median total vitamin D levels were lower in patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (29 vs. 18 ng/mL; P = .03), but age and body mass index were not different among patients for whom neurologists ordered Vitamin D levels, DXA scans, or supplementation.

Dr. Afgan acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and small sample size. “Also, type and duration of epilepsy, type and duration of antiepileptic drugs, and comorbidities should be considered in further studies with larger sample sizes,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Neurologists and other clinicians ordered vitamin D levels, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, and vitamin D supplementation for epilepsy patients in order to diagnose and prevent vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia, results from a single-center study showed.

Vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia are well described in the literature for patients on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (EIADs), but no guidelines currently exist for when to order tests or supplementation for patients on EIADs or non–enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs (NEIADs). “Further studies with larger sample sizes will be helpful in order to establish guidelines for neurologists and other physicians,” Sher Afgan, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Afgan, a research assistant at Drexel, went on to report that neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% had already been ordered by another physician. Neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (32% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001), and vitamin D levels were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (41% vs. 26%; P = .02). Neurologists ordered DXA scans in 22% of patients, and more often for those on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (33% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001). Similarly, DXA scans were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (35.3% vs. 18.2%; P = .006). Supplementation was ordered in 23% of patients and was more likely to be ordered by neurologists for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (36% vs. 8%; P less than .001).

The researchers also found that neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels, DXA scans, and supplements for men on EIADs, compared with women on EIADs (odds ratio, 2.178, P = .03; OR, 2.31, P = .02; OR, 1.87, P = .09, respectively). Generalized epilepsy did not significantly account for increases in ordering vitamin D for EIADs. Median total vitamin D levels were lower in patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (29 vs. 18 ng/mL; P = .03), but age and body mass index were not different among patients for whom neurologists ordered Vitamin D levels, DXA scans, or supplementation.

Dr. Afgan acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and small sample size. “Also, type and duration of epilepsy, type and duration of antiepileptic drugs, and comorbidities should be considered in further studies with larger sample sizes,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Neurologists and other clinicians ordered vitamin D levels, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, and vitamin D supplementation for epilepsy patients in order to diagnose and prevent vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia, results from a single-center study showed.

Vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia are well described in the literature for patients on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (EIADs), but no guidelines currently exist for when to order tests or supplementation for patients on EIADs or non–enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs (NEIADs). “Further studies with larger sample sizes will be helpful in order to establish guidelines for neurologists and other physicians,” Sher Afgan, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Afgan, a research assistant at Drexel, went on to report that neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% had already been ordered by another physician. Neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (32% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001), and vitamin D levels were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (41% vs. 26%; P = .02). Neurologists ordered DXA scans in 22% of patients, and more often for those on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (33% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001). Similarly, DXA scans were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (35.3% vs. 18.2%; P = .006). Supplementation was ordered in 23% of patients and was more likely to be ordered by neurologists for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (36% vs. 8%; P less than .001).

The researchers also found that neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels, DXA scans, and supplements for men on EIADs, compared with women on EIADs (odds ratio, 2.178, P = .03; OR, 2.31, P = .02; OR, 1.87, P = .09, respectively). Generalized epilepsy did not significantly account for increases in ordering vitamin D for EIADs. Median total vitamin D levels were lower in patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (29 vs. 18 ng/mL; P = .03), but age and body mass index were not different among patients for whom neurologists ordered Vitamin D levels, DXA scans, or supplementation.

Dr. Afgan acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and small sample size. “Also, type and duration of epilepsy, type and duration of antiepileptic drugs, and comorbidities should be considered in further studies with larger sample sizes,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% were already ordered by another physician.

Data source: A retrospective review of 190 patients who had a diagnosis of epilepsy or seizures, were currently on antiepileptic medications, and whose most recent neurology visit occurred between 2009 and 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Afgan reported having no financial disclosures.

Project aims to improve understanding of AED prescribing trends

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%).

Data source: A pilot study that evaluated medical records from about 2.5 million epilepsy patients from 2013 to 2015.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

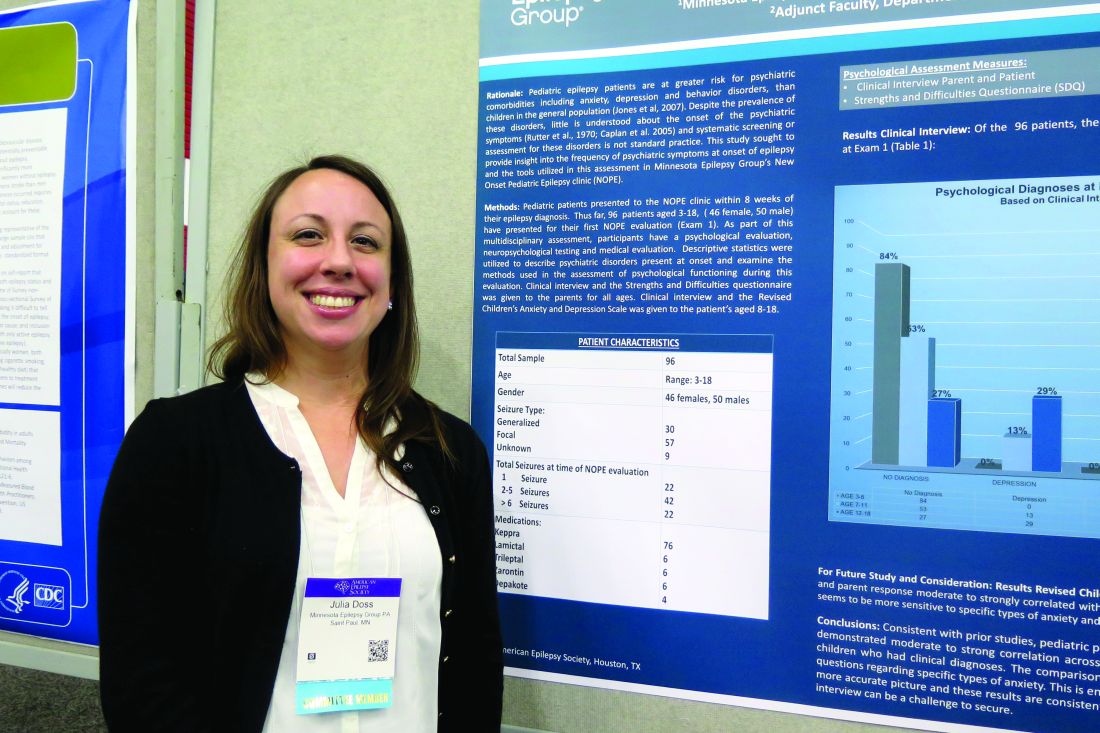

Psychiatric comorbidities common in newly diagnosed pediatric epilepsy cases

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among patients aged 12-18 years, the percentage who met criteria for criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 29%, 38%, and 10%, respectively.

Data source: A study of 96 patients who presented to a New Onset Pediatric Epilepsy (NOPE) clinic within 8 weeks of their epilepsy diagnosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Doss reported having no financial disclosures.

Study eyes fracture risk in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic drugs

HOUSTON – The incidence of fractures in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic medication stands at an estimated 1.1%, according to results from a 4-year period at a children’s hospital.

“Understanding the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an AED [antiepileptic drug] will allow clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefit of therapy,” researchers led by Shannon DiCarlo, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Recognizing a risk of fractures with AEDs will permit clinicians to provide appropriate supportive care and monitoring from the initiation of therapy.”

Dr. DiCarlo of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and her associates went on to note that adults with epilepsy have a twofold to sixfold greater risk of experiencing fractures, compared with the general population, and that fractures secondary to seizures “are a major concern in pediatrics.” In fact, one survey of 404 pediatric neurologists found that only 41% of respondents were aware of the association between AEDs and reduced bone mass (Arch Neurol. 2001;58[9]:1369-74).

In an effort to evaluate the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an antiepileptic drug, the researchers conducted a cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014. Half of the study population were female, and the most common concomitant disease was epilepsy (52.6%), followed by cerebral palsy (8.3%), epilepsy plus cerebral palsy (6.9%), osteoporosis (0.2%), and osteopenia (0.3%). In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of an AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years. Patients on enzyme-inducing AEDs were two times more likely to experience a fracture, while those with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were three times more likely to experience a fracture. Proton pump inhibitors and corticosteroids were the most common concomitant drugs. The researchers also found that less than 10% of patients were on calcium or vitamin D supplementation.

“Vigilant monitoring should be employed for at-risk patients,” the researchers concluded. “Regular monitoring of calcium and vitamin D levels may be warranted; further studies are needed to evaluate the roll of prophylactic calcium and vitamin D supplements.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The incidence of fractures in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic medication stands at an estimated 1.1%, according to results from a 4-year period at a children’s hospital.

“Understanding the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an AED [antiepileptic drug] will allow clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefit of therapy,” researchers led by Shannon DiCarlo, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Recognizing a risk of fractures with AEDs will permit clinicians to provide appropriate supportive care and monitoring from the initiation of therapy.”

Dr. DiCarlo of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and her associates went on to note that adults with epilepsy have a twofold to sixfold greater risk of experiencing fractures, compared with the general population, and that fractures secondary to seizures “are a major concern in pediatrics.” In fact, one survey of 404 pediatric neurologists found that only 41% of respondents were aware of the association between AEDs and reduced bone mass (Arch Neurol. 2001;58[9]:1369-74).

In an effort to evaluate the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an antiepileptic drug, the researchers conducted a cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014. Half of the study population were female, and the most common concomitant disease was epilepsy (52.6%), followed by cerebral palsy (8.3%), epilepsy plus cerebral palsy (6.9%), osteoporosis (0.2%), and osteopenia (0.3%). In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of an AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years. Patients on enzyme-inducing AEDs were two times more likely to experience a fracture, while those with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were three times more likely to experience a fracture. Proton pump inhibitors and corticosteroids were the most common concomitant drugs. The researchers also found that less than 10% of patients were on calcium or vitamin D supplementation.

“Vigilant monitoring should be employed for at-risk patients,” the researchers concluded. “Regular monitoring of calcium and vitamin D levels may be warranted; further studies are needed to evaluate the roll of prophylactic calcium and vitamin D supplements.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The incidence of fractures in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic medication stands at an estimated 1.1%, according to results from a 4-year period at a children’s hospital.

“Understanding the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an AED [antiepileptic drug] will allow clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefit of therapy,” researchers led by Shannon DiCarlo, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Recognizing a risk of fractures with AEDs will permit clinicians to provide appropriate supportive care and monitoring from the initiation of therapy.”

Dr. DiCarlo of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and her associates went on to note that adults with epilepsy have a twofold to sixfold greater risk of experiencing fractures, compared with the general population, and that fractures secondary to seizures “are a major concern in pediatrics.” In fact, one survey of 404 pediatric neurologists found that only 41% of respondents were aware of the association between AEDs and reduced bone mass (Arch Neurol. 2001;58[9]:1369-74).

In an effort to evaluate the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an antiepileptic drug, the researchers conducted a cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014. Half of the study population were female, and the most common concomitant disease was epilepsy (52.6%), followed by cerebral palsy (8.3%), epilepsy plus cerebral palsy (6.9%), osteoporosis (0.2%), and osteopenia (0.3%). In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of an AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years. Patients on enzyme-inducing AEDs were two times more likely to experience a fracture, while those with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were three times more likely to experience a fracture. Proton pump inhibitors and corticosteroids were the most common concomitant drugs. The researchers also found that less than 10% of patients were on calcium or vitamin D supplementation.

“Vigilant monitoring should be employed for at-risk patients,” the researchers concluded. “Regular monitoring of calcium and vitamin D levels may be warranted; further studies are needed to evaluate the roll of prophylactic calcium and vitamin D supplements.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years.

Data source: A cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

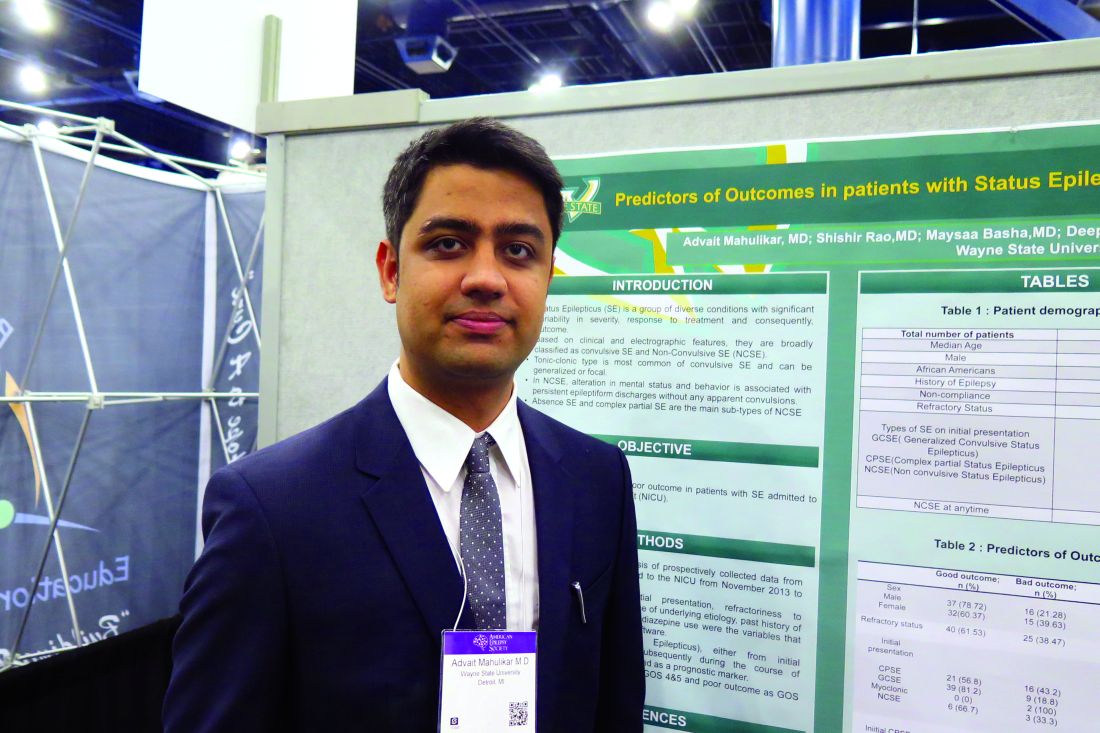

Study identifies predictors of poor outcome in status epilepticus

HOUSTON – Predictors of poor outcomes in patients with status epilepticus admitted to the neurointensive care unit include complex partial status epilepticus (CPSE), refractory status epilepticus, or the development of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) at any time during the hospital course, according to results from a single-center study.

“Not a lot of data exist as to what predicts the poor outcomes and what’s known about the outcome in patients with status epilepticus,” lead study author Advait Mahulikar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016. Variables of interest included patient demographics, initial presentation, refractoriness to treatment, presence or absence of underlying etiology, past history of epilepsy, and use of benzodiazepines on admission. Another variable of interest was NCSE, either from initial presentation or developed during the course of convulsive status epilepticus. A good outcome was defined as a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 4 or 5, and a poor outcome was defined as a GOS score of 1-3.

Neither age nor gender predicted poor outcome, and there was no difference in outcome between structural and nonstructural causes of status epilepticus. However, prior history of epilepsy was a strong negative predictor of poor outcome. In fact, only 14 of 70 patients (20%) with a prior history of epilepsy had a poor outcome (P less than .01). “The theory is that [these patients] were already on treatment for epilepsy in the past and that affected their outcome in a positive way,” Dr. Mahulikar explained.

When outcome was analyzed based on status semiology on initial presentation, poor outcome was seen in 16 of the 37 patients (43%) with CPSE (P = .04); 9 of 48 patients (19%) with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus (n = 2), and 3 of 9 (33%) who had NCSE (P less than .01). The type of status epilepticus was unknown for four patients, one of whom had an unknown outcome. NCSE at any time during the hospital course (including at presentation) was seen in 31 patients. Of these, 14 (45%) had a poor outcome (P = .02).

The mean number of ventilator days was higher in patients with NCSE than in those without NCSE (9.2 vs. 1.6 days; P = .0001) and also higher in those with new-onset seizures than in those without (7.8 vs. 2.9 days; P = .001). Analysis of methods of treatments revealed that only 7 of 31 (22.5%) patients who received adequate benzodiazepine dosing had poor outcomes (P = .2247). “The take-home message is to diagnose NCSE as early as possible because I think some patients who come in initially we may attribute to metabolic or autoimmune causes, and we tend to miss NCSE sometimes due to delay in diagnosis of NCSE,” Dr. Mahulikar said. “Treat aggressively at the beginning.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Predictors of poor outcomes in patients with status epilepticus admitted to the neurointensive care unit include complex partial status epilepticus (CPSE), refractory status epilepticus, or the development of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) at any time during the hospital course, according to results from a single-center study.

“Not a lot of data exist as to what predicts the poor outcomes and what’s known about the outcome in patients with status epilepticus,” lead study author Advait Mahulikar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016. Variables of interest included patient demographics, initial presentation, refractoriness to treatment, presence or absence of underlying etiology, past history of epilepsy, and use of benzodiazepines on admission. Another variable of interest was NCSE, either from initial presentation or developed during the course of convulsive status epilepticus. A good outcome was defined as a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 4 or 5, and a poor outcome was defined as a GOS score of 1-3.

Neither age nor gender predicted poor outcome, and there was no difference in outcome between structural and nonstructural causes of status epilepticus. However, prior history of epilepsy was a strong negative predictor of poor outcome. In fact, only 14 of 70 patients (20%) with a prior history of epilepsy had a poor outcome (P less than .01). “The theory is that [these patients] were already on treatment for epilepsy in the past and that affected their outcome in a positive way,” Dr. Mahulikar explained.

When outcome was analyzed based on status semiology on initial presentation, poor outcome was seen in 16 of the 37 patients (43%) with CPSE (P = .04); 9 of 48 patients (19%) with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus (n = 2), and 3 of 9 (33%) who had NCSE (P less than .01). The type of status epilepticus was unknown for four patients, one of whom had an unknown outcome. NCSE at any time during the hospital course (including at presentation) was seen in 31 patients. Of these, 14 (45%) had a poor outcome (P = .02).

The mean number of ventilator days was higher in patients with NCSE than in those without NCSE (9.2 vs. 1.6 days; P = .0001) and also higher in those with new-onset seizures than in those without (7.8 vs. 2.9 days; P = .001). Analysis of methods of treatments revealed that only 7 of 31 (22.5%) patients who received adequate benzodiazepine dosing had poor outcomes (P = .2247). “The take-home message is to diagnose NCSE as early as possible because I think some patients who come in initially we may attribute to metabolic or autoimmune causes, and we tend to miss NCSE sometimes due to delay in diagnosis of NCSE,” Dr. Mahulikar said. “Treat aggressively at the beginning.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Predictors of poor outcomes in patients with status epilepticus admitted to the neurointensive care unit include complex partial status epilepticus (CPSE), refractory status epilepticus, or the development of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) at any time during the hospital course, according to results from a single-center study.

“Not a lot of data exist as to what predicts the poor outcomes and what’s known about the outcome in patients with status epilepticus,” lead study author Advait Mahulikar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016. Variables of interest included patient demographics, initial presentation, refractoriness to treatment, presence or absence of underlying etiology, past history of epilepsy, and use of benzodiazepines on admission. Another variable of interest was NCSE, either from initial presentation or developed during the course of convulsive status epilepticus. A good outcome was defined as a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 4 or 5, and a poor outcome was defined as a GOS score of 1-3.

Neither age nor gender predicted poor outcome, and there was no difference in outcome between structural and nonstructural causes of status epilepticus. However, prior history of epilepsy was a strong negative predictor of poor outcome. In fact, only 14 of 70 patients (20%) with a prior history of epilepsy had a poor outcome (P less than .01). “The theory is that [these patients] were already on treatment for epilepsy in the past and that affected their outcome in a positive way,” Dr. Mahulikar explained.

When outcome was analyzed based on status semiology on initial presentation, poor outcome was seen in 16 of the 37 patients (43%) with CPSE (P = .04); 9 of 48 patients (19%) with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus (n = 2), and 3 of 9 (33%) who had NCSE (P less than .01). The type of status epilepticus was unknown for four patients, one of whom had an unknown outcome. NCSE at any time during the hospital course (including at presentation) was seen in 31 patients. Of these, 14 (45%) had a poor outcome (P = .02).

The mean number of ventilator days was higher in patients with NCSE than in those without NCSE (9.2 vs. 1.6 days; P = .0001) and also higher in those with new-onset seizures than in those without (7.8 vs. 2.9 days; P = .001). Analysis of methods of treatments revealed that only 7 of 31 (22.5%) patients who received adequate benzodiazepine dosing had poor outcomes (P = .2247). “The take-home message is to diagnose NCSE as early as possible because I think some patients who come in initially we may attribute to metabolic or autoimmune causes, and we tend to miss NCSE sometimes due to delay in diagnosis of NCSE,” Dr. Mahulikar said. “Treat aggressively at the beginning.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Poor outcome was seen in 43% of patients with CPSE, 19% with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus, and in 33% of those who had NCSE.

Data source: A retrospective review of data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016.

Disclosures: Dr. Mahulikar reported having no financial disclosures.

Coronary revascularization appropriate use criteria updated

For ST segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients presenting between 12 and 24 hours from symptom onset but with no signs of clinical instability, coronary revascularization “may be appropriate,” according to a new report. At the same time, for STEMI patients initially treated with fibrinolysis, revascularization was rated as “appropriate therapy” in the setting of suspected failed fibrinolytic therapy or in stable and asymptomatic patients from 3 to 24 hours after fibrinolysis.

Those are two conclusions contained in a revision of the appropriate use criteria (AUC) for coronary revascularization published on Dec. 21 (J Am Coll Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.034).

“This update provides a reassessment of clinical scenarios that the writing group felt to be affected by significant changes in the medical literature or gaps from prior criteria,” Manesh R. Patel, MD, chief of the division of cardiology and codirector of the Duke Heart Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and chair of the seven-member writing committee for the document, said in a prepared statement. “The primary objective of the appropriate use criteria is to provide a framework for the assessment of practice patterns that will hopefully improve physician decision making and ultimately lead to better patient outcomes.”

The 22-page document contains 17 clinical scenarios that were scored by a separate committee of 17 experts to indicate whether revascularization in patients with acute coronary syndromes is appropriate, may be appropriate, or is rarely appropriate for the clinical scenario presented. Step-by-step flow charts are included to help use the criteria. “Since publication of the 2012 AUC document (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:857-81), new guidelines for [STEMI] and non–ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)/unstable angina have been published with additional focused updates of the [stable ischemic heart disease] guideline and a combined focused update of the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and STEMI guideline,” the writing committee noted. “New clinical trials have been published extending the knowledge and evidence around coronary revascularization, including trials that challenge earlier recommendations about the timing of nonculprit vessel PCI in the setting of STEMI. Additional studies related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery, medical therapy, and diagnostic technologies such as fractional flow reserve (FFR) have emerged as well as analyses from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) on the existing AUC that provide insights into practice patterns, clinical scenarios, and patient features not previously addressed.”

Conclusions in the document include those for nonculprit artery revascularization during the index hospitalization after primary PCI or fibrinolysis. This was rated as “appropriate and reasonable” for patients with one or more severe stenoses and spontaneous or easily provoked ischemia or for asymptomatic patients with ischemic findings on noninvasive testing. Meanwhile, in the presence of an intermediate-severity nonculprit artery stenosis, revascularization was rated as “appropriate therapy” in cases where the fractional flow reserve is at or below 0.80. For patients who are stable and asymptomatic after primary PCI, revascularization was rated as “may be appropriate” for one or more severe stenoses even in the absence of further testing.

The only “rarely appropriate” rating in patients with acute coronary syndromes occurred for asymptomatic patients with intermediate-severity nonculprit artery stenoses in the absence of any additional testing to demonstrate the functional significance of the stenosis.

“As in prior versions of the AUC, these revascularization ratings should be used to reinforce existing management strategies and identify patient populations that need more information to identify the most effective treatments,” the authors concluded. Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures.

For ST segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients presenting between 12 and 24 hours from symptom onset but with no signs of clinical instability, coronary revascularization “may be appropriate,” according to a new report. At the same time, for STEMI patients initially treated with fibrinolysis, revascularization was rated as “appropriate therapy” in the setting of suspected failed fibrinolytic therapy or in stable and asymptomatic patients from 3 to 24 hours after fibrinolysis.

Those are two conclusions contained in a revision of the appropriate use criteria (AUC) for coronary revascularization published on Dec. 21 (J Am Coll Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.034).

“This update provides a reassessment of clinical scenarios that the writing group felt to be affected by significant changes in the medical literature or gaps from prior criteria,” Manesh R. Patel, MD, chief of the division of cardiology and codirector of the Duke Heart Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and chair of the seven-member writing committee for the document, said in a prepared statement. “The primary objective of the appropriate use criteria is to provide a framework for the assessment of practice patterns that will hopefully improve physician decision making and ultimately lead to better patient outcomes.”

The 22-page document contains 17 clinical scenarios that were scored by a separate committee of 17 experts to indicate whether revascularization in patients with acute coronary syndromes is appropriate, may be appropriate, or is rarely appropriate for the clinical scenario presented. Step-by-step flow charts are included to help use the criteria. “Since publication of the 2012 AUC document (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:857-81), new guidelines for [STEMI] and non–ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)/unstable angina have been published with additional focused updates of the [stable ischemic heart disease] guideline and a combined focused update of the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and STEMI guideline,” the writing committee noted. “New clinical trials have been published extending the knowledge and evidence around coronary revascularization, including trials that challenge earlier recommendations about the timing of nonculprit vessel PCI in the setting of STEMI. Additional studies related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery, medical therapy, and diagnostic technologies such as fractional flow reserve (FFR) have emerged as well as analyses from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) on the existing AUC that provide insights into practice patterns, clinical scenarios, and patient features not previously addressed.”

Conclusions in the document include those for nonculprit artery revascularization during the index hospitalization after primary PCI or fibrinolysis. This was rated as “appropriate and reasonable” for patients with one or more severe stenoses and spontaneous or easily provoked ischemia or for asymptomatic patients with ischemic findings on noninvasive testing. Meanwhile, in the presence of an intermediate-severity nonculprit artery stenosis, revascularization was rated as “appropriate therapy” in cases where the fractional flow reserve is at or below 0.80. For patients who are stable and asymptomatic after primary PCI, revascularization was rated as “may be appropriate” for one or more severe stenoses even in the absence of further testing.

The only “rarely appropriate” rating in patients with acute coronary syndromes occurred for asymptomatic patients with intermediate-severity nonculprit artery stenoses in the absence of any additional testing to demonstrate the functional significance of the stenosis.

“As in prior versions of the AUC, these revascularization ratings should be used to reinforce existing management strategies and identify patient populations that need more information to identify the most effective treatments,” the authors concluded. Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures.

For ST segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients presenting between 12 and 24 hours from symptom onset but with no signs of clinical instability, coronary revascularization “may be appropriate,” according to a new report. At the same time, for STEMI patients initially treated with fibrinolysis, revascularization was rated as “appropriate therapy” in the setting of suspected failed fibrinolytic therapy or in stable and asymptomatic patients from 3 to 24 hours after fibrinolysis.

Those are two conclusions contained in a revision of the appropriate use criteria (AUC) for coronary revascularization published on Dec. 21 (J Am Coll Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.034).

“This update provides a reassessment of clinical scenarios that the writing group felt to be affected by significant changes in the medical literature or gaps from prior criteria,” Manesh R. Patel, MD, chief of the division of cardiology and codirector of the Duke Heart Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and chair of the seven-member writing committee for the document, said in a prepared statement. “The primary objective of the appropriate use criteria is to provide a framework for the assessment of practice patterns that will hopefully improve physician decision making and ultimately lead to better patient outcomes.”

The 22-page document contains 17 clinical scenarios that were scored by a separate committee of 17 experts to indicate whether revascularization in patients with acute coronary syndromes is appropriate, may be appropriate, or is rarely appropriate for the clinical scenario presented. Step-by-step flow charts are included to help use the criteria. “Since publication of the 2012 AUC document (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:857-81), new guidelines for [STEMI] and non–ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)/unstable angina have been published with additional focused updates of the [stable ischemic heart disease] guideline and a combined focused update of the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and STEMI guideline,” the writing committee noted. “New clinical trials have been published extending the knowledge and evidence around coronary revascularization, including trials that challenge earlier recommendations about the timing of nonculprit vessel PCI in the setting of STEMI. Additional studies related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery, medical therapy, and diagnostic technologies such as fractional flow reserve (FFR) have emerged as well as analyses from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) on the existing AUC that provide insights into practice patterns, clinical scenarios, and patient features not previously addressed.”

Conclusions in the document include those for nonculprit artery revascularization during the index hospitalization after primary PCI or fibrinolysis. This was rated as “appropriate and reasonable” for patients with one or more severe stenoses and spontaneous or easily provoked ischemia or for asymptomatic patients with ischemic findings on noninvasive testing. Meanwhile, in the presence of an intermediate-severity nonculprit artery stenosis, revascularization was rated as “appropriate therapy” in cases where the fractional flow reserve is at or below 0.80. For patients who are stable and asymptomatic after primary PCI, revascularization was rated as “may be appropriate” for one or more severe stenoses even in the absence of further testing.

The only “rarely appropriate” rating in patients with acute coronary syndromes occurred for asymptomatic patients with intermediate-severity nonculprit artery stenoses in the absence of any additional testing to demonstrate the functional significance of the stenosis.

“As in prior versions of the AUC, these revascularization ratings should be used to reinforce existing management strategies and identify patient populations that need more information to identify the most effective treatments,” the authors concluded. Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Reasons for noncompliance to ketogenic diet explored

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: More than one-third of children (43%) discontinued the ketogenic diet before the end of a 3-month trial period.

Data source: A prospective evaluation of 64 patients with intractable epilepsy and their families who were educated about the ketogenic diet at Dayton Children’s Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Kumar reported having no financial disclosures.

FDA gives nod to crisaborole for atopic dermatitis

The Food and Drug Administration has approved crisaborole topical ointment, 2%, to treat mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in patients 2 years of age and older. The boron-based phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, which will be marketed as Eucrisa, was developed by Anacor Pharmaceuticals, which Pfizer acquired in May of 2016.

“Today’s approval provides another treatment option for patients dealing with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis,” Amy Egan, deputy director of the Office of Drug Evaluation III in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement. Safety and efficacy of the drug were established in two placebo-controlled trials with a total of 1,522 participants aged 2-79 years with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association in August 2016, Dr. Kelly Cordoro, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Francisco, described crisaborole as an anti-inflammatory agent that modifies inflammation by inhibiting the degradation of cAMP by PDE4, resulting in downstream modification of nuclear factor-kB and T-cell signaling pathways. “Crisaborole has shown promising results from four clinical studies in patients 2 years of age and older, with notable improvements in all atopic dermatitis parameters,” she said.

The results of the two phase III studies were recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2016 Sept;75[3]:494-503).

The Food and Drug Administration has approved crisaborole topical ointment, 2%, to treat mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in patients 2 years of age and older. The boron-based phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, which will be marketed as Eucrisa, was developed by Anacor Pharmaceuticals, which Pfizer acquired in May of 2016.

“Today’s approval provides another treatment option for patients dealing with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis,” Amy Egan, deputy director of the Office of Drug Evaluation III in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement. Safety and efficacy of the drug were established in two placebo-controlled trials with a total of 1,522 participants aged 2-79 years with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association in August 2016, Dr. Kelly Cordoro, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Francisco, described crisaborole as an anti-inflammatory agent that modifies inflammation by inhibiting the degradation of cAMP by PDE4, resulting in downstream modification of nuclear factor-kB and T-cell signaling pathways. “Crisaborole has shown promising results from four clinical studies in patients 2 years of age and older, with notable improvements in all atopic dermatitis parameters,” she said.

The results of the two phase III studies were recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2016 Sept;75[3]:494-503).

The Food and Drug Administration has approved crisaborole topical ointment, 2%, to treat mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in patients 2 years of age and older. The boron-based phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, which will be marketed as Eucrisa, was developed by Anacor Pharmaceuticals, which Pfizer acquired in May of 2016.

“Today’s approval provides another treatment option for patients dealing with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis,” Amy Egan, deputy director of the Office of Drug Evaluation III in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement. Safety and efficacy of the drug were established in two placebo-controlled trials with a total of 1,522 participants aged 2-79 years with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association in August 2016, Dr. Kelly Cordoro, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Francisco, described crisaborole as an anti-inflammatory agent that modifies inflammation by inhibiting the degradation of cAMP by PDE4, resulting in downstream modification of nuclear factor-kB and T-cell signaling pathways. “Crisaborole has shown promising results from four clinical studies in patients 2 years of age and older, with notable improvements in all atopic dermatitis parameters,” she said.

The results of the two phase III studies were recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2016 Sept;75[3]:494-503).

Cardiovascular comorbidities common in patients with epilepsy

HOUSTON – Adults with epilepsy reported five of the six most common cardiovascular diseases more often than did adults without epilepsy, according to results from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey.

“Often, neurologists are busy treating the seizure, making sure the patient has proper treatment, but they often don’t have the time to look at these conditions that can cause deaths a lot more commonly than things like sudden unexpected death from epilepsy,” lead study author Matthew Zack, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We’re not talking about mortality here, but it’s important for doctors to be aware of the fact that patients with epilepsy have increased risk for conditions like heart attacks, high blood pressure, and stroke.”