User login

AAP: Protect from vaccine refusal with documentation

Protecting oneself when parents refuse vaccinations for their children entails documenting all discussions – including a conversation about how parents should respond to illness or fever – as well as creating a system in the office to identify incompletely immunized patients for proper triage and care should the need arise, Dr. James P. Scibilia said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians should also document that parents have received a vaccine information sheet at each relevant visit and ensure that parents sign appropriate and unaltered “informed refusal” forms, preferably the AAP’s Refusal to Vaccinate form, each time vaccination is refused, said Dr. Scibilia, who is not an attorney but serves on the AAP Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management.

“If patients bring their own form, make sure you read it properly. I received one that had an AAP logo and looked like our form but had a different set of information,” he said.

Physicians may be at legal risk if parents claim in the wake of a bad outcome that they weren’t informed of the risk of nonvaccination; courts have favored the plaintiffs in at least a couple of reported cases thus far, he explained.

Documentation of repeated vaccine discussions – with chart notes indicating that “you’ve reemphasized the risks of not getting a vaccine,” for instance – is important. “Have some little phrase to integrate into your records so you can show that each time the patient came in, you readdressed the issue with them,” said Dr. Scibilia, of Heritage Valley Health System, Beaver, Pa.

“Then make sure you tell your parents that their [unvaccinated] child may require more aggressive evaluation when ill,” he said. “And make sure you have some kind of triage in your phone protocol system.”

Not properly triaging or caring for an unimmunized or underimmunized child may be legally risky, he explained. “If you have a 10-month-old child who hasn’t had their pneumococcal vaccine and develops a 104° fever, you’re going to treat that child differently than one who had the vaccine,” he said. “You need to have some way to identify kids who aren’t immunized and triage them properly.”

Less clear is a situation in which a child infected with a vaccine-preventable illness is seen in the office and infects another child while there. “There is no case law in the U.S. on this. It may happen at some point, but there is nothing right now that suggests you’re at special legal risk [in such a case],” said Dr. Scibilia.

Just as vaccine refusal has been a growing problem, so have requests for altered vaccine schedules. In a recent survey of pediatricians and family physicians, 93% of physicians reported that some parents had requested altered vaccine schedules within the prior month. A significant number of physicians agreed to spread out vaccines, either always or often (37%) or sometimes (37%).

In a minority of cases, physicians decided to dismiss families from their practice: 2% said they “always or often” dismissed patients, and 4% said they “sometimes” did (Pediatrics. 2015 Apr;135:666-77).

“As a group, it seems like pediatricians are following the AAP’s guidance in that we’re trying to convince parents [that vaccination is in their child’s best interest], but it seems that we’re willing to alter schedules in order to get kids vaccinated,” he said.

Whether to agree to alternative scheduling requests is a “philosophical question” for the individual physician to answer, with the understanding that “when you alter the established vaccine schedule, you’re putting yourself at some risk if a patient develops a vaccine-preventable illness during the time frame when you’ve altered the schedule,” he said.

If a physician-patient relationship must be severed, the termination should be done properly and formally in order to avoid possible claims of abandonment. This means providing written notification and documenting that the patient received the notification in a timely fashion, usually with a return receipt. The notification must include an offer to provide emergency care for a specified period of time, Dr. Scibilia said.

Protecting oneself when parents refuse vaccinations for their children entails documenting all discussions – including a conversation about how parents should respond to illness or fever – as well as creating a system in the office to identify incompletely immunized patients for proper triage and care should the need arise, Dr. James P. Scibilia said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians should also document that parents have received a vaccine information sheet at each relevant visit and ensure that parents sign appropriate and unaltered “informed refusal” forms, preferably the AAP’s Refusal to Vaccinate form, each time vaccination is refused, said Dr. Scibilia, who is not an attorney but serves on the AAP Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management.

“If patients bring their own form, make sure you read it properly. I received one that had an AAP logo and looked like our form but had a different set of information,” he said.

Physicians may be at legal risk if parents claim in the wake of a bad outcome that they weren’t informed of the risk of nonvaccination; courts have favored the plaintiffs in at least a couple of reported cases thus far, he explained.

Documentation of repeated vaccine discussions – with chart notes indicating that “you’ve reemphasized the risks of not getting a vaccine,” for instance – is important. “Have some little phrase to integrate into your records so you can show that each time the patient came in, you readdressed the issue with them,” said Dr. Scibilia, of Heritage Valley Health System, Beaver, Pa.

“Then make sure you tell your parents that their [unvaccinated] child may require more aggressive evaluation when ill,” he said. “And make sure you have some kind of triage in your phone protocol system.”

Not properly triaging or caring for an unimmunized or underimmunized child may be legally risky, he explained. “If you have a 10-month-old child who hasn’t had their pneumococcal vaccine and develops a 104° fever, you’re going to treat that child differently than one who had the vaccine,” he said. “You need to have some way to identify kids who aren’t immunized and triage them properly.”

Less clear is a situation in which a child infected with a vaccine-preventable illness is seen in the office and infects another child while there. “There is no case law in the U.S. on this. It may happen at some point, but there is nothing right now that suggests you’re at special legal risk [in such a case],” said Dr. Scibilia.

Just as vaccine refusal has been a growing problem, so have requests for altered vaccine schedules. In a recent survey of pediatricians and family physicians, 93% of physicians reported that some parents had requested altered vaccine schedules within the prior month. A significant number of physicians agreed to spread out vaccines, either always or often (37%) or sometimes (37%).

In a minority of cases, physicians decided to dismiss families from their practice: 2% said they “always or often” dismissed patients, and 4% said they “sometimes” did (Pediatrics. 2015 Apr;135:666-77).

“As a group, it seems like pediatricians are following the AAP’s guidance in that we’re trying to convince parents [that vaccination is in their child’s best interest], but it seems that we’re willing to alter schedules in order to get kids vaccinated,” he said.

Whether to agree to alternative scheduling requests is a “philosophical question” for the individual physician to answer, with the understanding that “when you alter the established vaccine schedule, you’re putting yourself at some risk if a patient develops a vaccine-preventable illness during the time frame when you’ve altered the schedule,” he said.

If a physician-patient relationship must be severed, the termination should be done properly and formally in order to avoid possible claims of abandonment. This means providing written notification and documenting that the patient received the notification in a timely fashion, usually with a return receipt. The notification must include an offer to provide emergency care for a specified period of time, Dr. Scibilia said.

Protecting oneself when parents refuse vaccinations for their children entails documenting all discussions – including a conversation about how parents should respond to illness or fever – as well as creating a system in the office to identify incompletely immunized patients for proper triage and care should the need arise, Dr. James P. Scibilia said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians should also document that parents have received a vaccine information sheet at each relevant visit and ensure that parents sign appropriate and unaltered “informed refusal” forms, preferably the AAP’s Refusal to Vaccinate form, each time vaccination is refused, said Dr. Scibilia, who is not an attorney but serves on the AAP Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management.

“If patients bring their own form, make sure you read it properly. I received one that had an AAP logo and looked like our form but had a different set of information,” he said.

Physicians may be at legal risk if parents claim in the wake of a bad outcome that they weren’t informed of the risk of nonvaccination; courts have favored the plaintiffs in at least a couple of reported cases thus far, he explained.

Documentation of repeated vaccine discussions – with chart notes indicating that “you’ve reemphasized the risks of not getting a vaccine,” for instance – is important. “Have some little phrase to integrate into your records so you can show that each time the patient came in, you readdressed the issue with them,” said Dr. Scibilia, of Heritage Valley Health System, Beaver, Pa.

“Then make sure you tell your parents that their [unvaccinated] child may require more aggressive evaluation when ill,” he said. “And make sure you have some kind of triage in your phone protocol system.”

Not properly triaging or caring for an unimmunized or underimmunized child may be legally risky, he explained. “If you have a 10-month-old child who hasn’t had their pneumococcal vaccine and develops a 104° fever, you’re going to treat that child differently than one who had the vaccine,” he said. “You need to have some way to identify kids who aren’t immunized and triage them properly.”

Less clear is a situation in which a child infected with a vaccine-preventable illness is seen in the office and infects another child while there. “There is no case law in the U.S. on this. It may happen at some point, but there is nothing right now that suggests you’re at special legal risk [in such a case],” said Dr. Scibilia.

Just as vaccine refusal has been a growing problem, so have requests for altered vaccine schedules. In a recent survey of pediatricians and family physicians, 93% of physicians reported that some parents had requested altered vaccine schedules within the prior month. A significant number of physicians agreed to spread out vaccines, either always or often (37%) or sometimes (37%).

In a minority of cases, physicians decided to dismiss families from their practice: 2% said they “always or often” dismissed patients, and 4% said they “sometimes” did (Pediatrics. 2015 Apr;135:666-77).

“As a group, it seems like pediatricians are following the AAP’s guidance in that we’re trying to convince parents [that vaccination is in their child’s best interest], but it seems that we’re willing to alter schedules in order to get kids vaccinated,” he said.

Whether to agree to alternative scheduling requests is a “philosophical question” for the individual physician to answer, with the understanding that “when you alter the established vaccine schedule, you’re putting yourself at some risk if a patient develops a vaccine-preventable illness during the time frame when you’ve altered the schedule,” he said.

If a physician-patient relationship must be severed, the termination should be done properly and formally in order to avoid possible claims of abandonment. This means providing written notification and documenting that the patient received the notification in a timely fashion, usually with a return receipt. The notification must include an offer to provide emergency care for a specified period of time, Dr. Scibilia said.

AT THE AAP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

Complicated concussions drive new clinics, management approaches

The Fairfax Family Practice Comprehensive Concussion Center is an example of what dedicated physicians can accomplish when they undertake to improve upon an accepted medical approach to a health problem because it falls far short of effective. The concussion center’s hall wall is adorned with a broad and colorful sign autographed by scores of patients – many of them student-athletes – who have been cleared to return to their sports and activities and to lives free of restrictions and struggle following concussion.

Dr. Garry W.K. Ho, the double-credentialed family practice and sports medicine physician who directs the 2-year-old concussion center in Fairfax, Va., takes pride in the skills his team has acquired to facilitate these recoveries.

He and his colleagues within the practice’s sports medicine division established the center, teaming up with several certified athletic trainers, to meet what they saw as a growing, urgent need: to help concussed patients who were taking longer than the oft-mentioned 7-10 days or 2 weeks to heal.

“While many of the people we’d been treating in the clinic with typical 15- to 30-minute appointments and relatively simple follow-up were able to get better, there was clearly a subset of the population that was more complicated and needed a more dedicated, multidimensional approach,” Dr. Ho said.

Findings from a growing number of studies have shown that concussions can involve a vast array of deficits – problems with the vestibular and vision systems, for example – and that a more comprehensive initial evaluation and a multipronged approach to management could shorten recovery time for any individual with the brain injury, he said.

“We’d started to realize how much patients can benefit from new and creative approaches,” said Dr. Ho. “We were also appreciating that no one person can own this disorder. You can’t say that only the neurologist can treat a concussion, or only the family physician or sports medicine physician.

‘Silent epidemic’

A small but growing number of concussion-care programs and clinics are being established across the country. Most often, the programs are incorporated into hospitals and sports medicine clinics. But some, like the program Dr. Ho leads, are embedded within larger primary care practices with a sports medicine component.

And, in other traditional family practices, some physicians are deepening their knowledge of concussions and building the networks necessary for managing prolonged impairment.

“If we have a good understanding of brain injury, we can often facilitate recovery and help [our patients] get back on track seamlessly,” said Dr. Rebecca Jaffe, a family physician in Wilmington, Del. “And when recovery is protracted, when issues don’t resolve in 2-3 weeks, there’s often more to the situation than is initially apparent, and it’s often better that we have a team of individuals who can help us.”

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), there are not enough data for an accurate estimate of the incidence of sports-related concussions in youth (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2014. Sports-related concussions in youth: Improving the science, changing the culture. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.)

But among high school athletes, an increase in concussions has been documented in several emergency department studies and other longitudinal studies published over the past 7-8 years. Most recently, the first national study to look at trends among high school athletes showed the numbers of concussions reported by certified athletic trainers increasing from 0.23/1,000 athlete-exposures in the 2005-2006 academic year to 0.51/1,000 in the 2011-2012 academic year (Am. J. Sports Med. 2014;42:1710-5).

Experts attribute such increases largely to improved awareness and new state laws. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s launched its “Heads Up” educational program in 2004, for instance. And as of last year, every state and the District of Columbia had enacted at least one law to protect young athletes with concussions.

State concussion laws vary, but most require that parents, athletes, and coaches be educated about concussions, and that athletes with suspected concussions be evaluated and cleared by a health care professional with knowledge in concussions before returning to play.

It is likely, some experts say, that the upward curve is leveling off with improved awareness and diagnosis. But with such improvements there lurks a void of data on concussions in youth outside the realm of high school sports. And, according to the 2014 IOM report, the acute and long-term health threat from concussions is “not fully appreciated or acted upon” in many settings. “Kids are getting removed from play more frequently, but then it’s not really clear what anyone should do after that,” said Dr. Shireen Atabaki, an emergency medicine specialist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, who is leading several national initiatives to improve concussion care.

Too often, concussed children and teens receive little besides unnecessary CT scans in emergency departments and concussions go undiagnosed. And when concussions are diagnosed, discharge instructions are poor and “kids are sent out into a no-man’s land” where recovery is often poorly managed, she said.

When Dr. Ho and his colleagues opened their concussion center in March 2013, they began seeing patients who remained symptomatic after concussions that had occurred 6-12 months ago, and longer. “It was almost like a silent epidemic,” he said. “We had one young woman who’d been injured in her senior year of high school and was still symptomatic after 2 years.”

To build the program at Fairfax Family Practice, Dr. Ho and his colleagues, Dr. Thomas Howard and Dr. Marc Childress (who, like Dr. Ho, are board certified in sports medicine as well as family medicine), capitalized on what they saw as a valuable synergy with high school athletic trainers.

Dr. Ho had worked closely with athletic trainers as a volunteer medical adviser to the Fairfax County Public School System’s athletic training program, which provides care to student-athletes in 25 high schools. He drew on his relationships to recruit three athletic trainers who were at transition points in their careers and who had both experience and “passion” in the treatment of concussions.

One of them, Jon Almquist, VATL, ATC, had led the development of return-to-learn protocols and other management practices for the high schools. He had also partnered with investigators at MedStar Health Research Institute in Baltimore on research that documented a 4.2-fold increase in concussions among the school system’s high school athletes between 1997 and 2008 (Am. J. Sports Med. 2011;39:958-63).

More surprising than this increase, however, were some data collected after the study period ended. When Mr. Almquist looked at recovery times for the concussions reported between 2011 and 2013, he found that about 25% of concussions took 30 days or longer to recover – a portion greater than he’d seen anywhere in the literature.

According to the 2014 IOM report, youth athletes typically recover from a concussion within 2 weeks of the injury, but in 10-20% of cases the symptoms persist for a number of weeks, months, or even years.

“Families would come to us for advice,” Mr. Almquist recalled. Other than referring them to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s (UPMC) Sports Medicine Concussion Program, there were few local providers whom they believed offered comprehensive care and had experience with prolonged impairment.

Mr. Almquist and his fellow athletic trainers, and Dr. Ho and his physician colleagues, all had been following developments at UPMC’s Sports Medicine Concussion Program since it was established in 2000. The program had evolved to assess and manage diverse facets of concussions, including vision, vestibular, exertion, and medication components—not all of which are fully addressed in clinical practice guidelines and position statements. By 2010, the program was drawing 10,000 patients a year.

Care at UPMC is guided by a clinical neuropsychologist who assesses head injuries and then refers patients on as needed to other members of the team – like a neurovestibular expert for vestibular assessment and therapy, a neuro-optometrist for vision therapy, a physical therapist for exertion training, or a sports medicine physician for medication.

In planning their own concussion center, Dr. Ho and his team visited various programs in the country but homed in on UPMC. They decided to mimic several aspects of UPMC’s approach by providing comprehensive and individualized care, and by having the certified athletic trainers serve as the “quarterbacks.”

“The athletic trainer in our center does all the symptom inventories and history taking, a concussion-focused physical exam, vestibular-ocular-motor screening, and neurocognitive tests if appropriate,” said Dr. Ho.

Dr. Ho or one of his sports medicine physician colleagues then discusses results with the athletic trainer and completes the patient visit – with the trainer – by asking any necessary follow-up questions, probing further with additional evaluation, and writing medication prescriptions when appropriate.

Throughout the course of care – visits occur weekly to monthly and often last 30-90 minutes – the athletic trainer and physician work together on clinical issues such as sleep and mental health and on subtyping headaches (cognitive fatigue, cervicogenic, or migrainelike) and “determining where the headaches lie relative to other areas of dysfunction,” said Dr. Ho.

Much of the individualized counseling, monitoring, and coordination that’s required to address sleep hygiene, rest, nutrition, and graded return to physical and cognitive activity can be led by the athletic trainer, he said.

For the first year or so, patients were referred out for such special services as vision or vestibular therapy. But there were problems with this approach: One frequent issue was poor insurance coverage for these therapies. Another was the stress involved in getting to additional appointments on Fairfax’s congested roads. “Traffic and busy environments aren’t always tolerable for a concussed patient,” Dr. Ho said.

Dr. Ho searched the Internet, worked the phone, read the neuro-optometry and vestibular therapy literature, and attended conferences to learn what kinds of therapeutic exercises they could integrate into office visits and take-home care plans. Dr. Ho said he was “surprised at how willing some of [their] colleagues were to give us some basic skills” to help patients who “don’t all need the Cadillac version” of therapy.

About the same time they integrated basic vision and vestibular therapy, they also revamped their billing strategy, moving away from the use of prolonged service billing codes, which Dr. Ho said were frequently denied on the first submission, to using separate codes for the encounter, therapeutic exercise (which encompasses vision therapy and vestibular therapy), and various physical tests.

Concussion care networks

Fairfax Family Practice is not the only practice to center its concussion program on physician-athletic trainer partnerships. Carolina Family Practice and Sports Medicine, a 12-provider practice with three offices in and around Raleigh, N.C., took a similar approach when it established its concussion clinic in 2008.

“Concussion is the ultimate example of an injury that benefits from a team approach,” said Dr. Josh Bloom, medical director of the Carolina Sports Concussion Clinic that is embedded into the practice. “And it’s the one injury – the only injury in sports medicine – where the standard of care calls for the injury to be 100% resolved prior to being cleared to return to play.”

Dr. Jaffe, the family physician in Delaware, said she is fortunate to have a neuro-optometrist practicing in the medical building where her three-physician family practice resides, and a concussion care team in the nearby Nemours/Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, also in Wilmington.

Someday, she and others hope, physicians who see patients soon after injury will have tools to better predict clinical trajectories and identify who could benefit from earlier referral to a “more sophisticated team.”

For now, Dr. Jaffe said, she seeks assistance when headache and initial symptoms persist after 2-3 weeks or when their symptoms “seem out of proportion to the incident.”

Dr. Scott Ross of Novant Health Bull Run Family Medicine based in Manassas, Va., said that family physicians are well suited to guide management and should learn to evaluate each patient’s concussion-related impairments as thoroughly as possible.

About 3 years ago, he and a partner established an official “Sports Medicine and Concussion Management” service line in their practice. “We don’t have a concussion center all under one roof, but we have the knowledge, skills, and resources that we need,” he said.

This article was updated April 13, 2015.

The Fairfax Family Practice Comprehensive Concussion Center is an example of what dedicated physicians can accomplish when they undertake to improve upon an accepted medical approach to a health problem because it falls far short of effective. The concussion center’s hall wall is adorned with a broad and colorful sign autographed by scores of patients – many of them student-athletes – who have been cleared to return to their sports and activities and to lives free of restrictions and struggle following concussion.

Dr. Garry W.K. Ho, the double-credentialed family practice and sports medicine physician who directs the 2-year-old concussion center in Fairfax, Va., takes pride in the skills his team has acquired to facilitate these recoveries.

He and his colleagues within the practice’s sports medicine division established the center, teaming up with several certified athletic trainers, to meet what they saw as a growing, urgent need: to help concussed patients who were taking longer than the oft-mentioned 7-10 days or 2 weeks to heal.

“While many of the people we’d been treating in the clinic with typical 15- to 30-minute appointments and relatively simple follow-up were able to get better, there was clearly a subset of the population that was more complicated and needed a more dedicated, multidimensional approach,” Dr. Ho said.

Findings from a growing number of studies have shown that concussions can involve a vast array of deficits – problems with the vestibular and vision systems, for example – and that a more comprehensive initial evaluation and a multipronged approach to management could shorten recovery time for any individual with the brain injury, he said.

“We’d started to realize how much patients can benefit from new and creative approaches,” said Dr. Ho. “We were also appreciating that no one person can own this disorder. You can’t say that only the neurologist can treat a concussion, or only the family physician or sports medicine physician.

‘Silent epidemic’

A small but growing number of concussion-care programs and clinics are being established across the country. Most often, the programs are incorporated into hospitals and sports medicine clinics. But some, like the program Dr. Ho leads, are embedded within larger primary care practices with a sports medicine component.

And, in other traditional family practices, some physicians are deepening their knowledge of concussions and building the networks necessary for managing prolonged impairment.

“If we have a good understanding of brain injury, we can often facilitate recovery and help [our patients] get back on track seamlessly,” said Dr. Rebecca Jaffe, a family physician in Wilmington, Del. “And when recovery is protracted, when issues don’t resolve in 2-3 weeks, there’s often more to the situation than is initially apparent, and it’s often better that we have a team of individuals who can help us.”

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), there are not enough data for an accurate estimate of the incidence of sports-related concussions in youth (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2014. Sports-related concussions in youth: Improving the science, changing the culture. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.)

But among high school athletes, an increase in concussions has been documented in several emergency department studies and other longitudinal studies published over the past 7-8 years. Most recently, the first national study to look at trends among high school athletes showed the numbers of concussions reported by certified athletic trainers increasing from 0.23/1,000 athlete-exposures in the 2005-2006 academic year to 0.51/1,000 in the 2011-2012 academic year (Am. J. Sports Med. 2014;42:1710-5).

Experts attribute such increases largely to improved awareness and new state laws. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s launched its “Heads Up” educational program in 2004, for instance. And as of last year, every state and the District of Columbia had enacted at least one law to protect young athletes with concussions.

State concussion laws vary, but most require that parents, athletes, and coaches be educated about concussions, and that athletes with suspected concussions be evaluated and cleared by a health care professional with knowledge in concussions before returning to play.

It is likely, some experts say, that the upward curve is leveling off with improved awareness and diagnosis. But with such improvements there lurks a void of data on concussions in youth outside the realm of high school sports. And, according to the 2014 IOM report, the acute and long-term health threat from concussions is “not fully appreciated or acted upon” in many settings. “Kids are getting removed from play more frequently, but then it’s not really clear what anyone should do after that,” said Dr. Shireen Atabaki, an emergency medicine specialist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, who is leading several national initiatives to improve concussion care.

Too often, concussed children and teens receive little besides unnecessary CT scans in emergency departments and concussions go undiagnosed. And when concussions are diagnosed, discharge instructions are poor and “kids are sent out into a no-man’s land” where recovery is often poorly managed, she said.

When Dr. Ho and his colleagues opened their concussion center in March 2013, they began seeing patients who remained symptomatic after concussions that had occurred 6-12 months ago, and longer. “It was almost like a silent epidemic,” he said. “We had one young woman who’d been injured in her senior year of high school and was still symptomatic after 2 years.”

To build the program at Fairfax Family Practice, Dr. Ho and his colleagues, Dr. Thomas Howard and Dr. Marc Childress (who, like Dr. Ho, are board certified in sports medicine as well as family medicine), capitalized on what they saw as a valuable synergy with high school athletic trainers.

Dr. Ho had worked closely with athletic trainers as a volunteer medical adviser to the Fairfax County Public School System’s athletic training program, which provides care to student-athletes in 25 high schools. He drew on his relationships to recruit three athletic trainers who were at transition points in their careers and who had both experience and “passion” in the treatment of concussions.

One of them, Jon Almquist, VATL, ATC, had led the development of return-to-learn protocols and other management practices for the high schools. He had also partnered with investigators at MedStar Health Research Institute in Baltimore on research that documented a 4.2-fold increase in concussions among the school system’s high school athletes between 1997 and 2008 (Am. J. Sports Med. 2011;39:958-63).

More surprising than this increase, however, were some data collected after the study period ended. When Mr. Almquist looked at recovery times for the concussions reported between 2011 and 2013, he found that about 25% of concussions took 30 days or longer to recover – a portion greater than he’d seen anywhere in the literature.

According to the 2014 IOM report, youth athletes typically recover from a concussion within 2 weeks of the injury, but in 10-20% of cases the symptoms persist for a number of weeks, months, or even years.

“Families would come to us for advice,” Mr. Almquist recalled. Other than referring them to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s (UPMC) Sports Medicine Concussion Program, there were few local providers whom they believed offered comprehensive care and had experience with prolonged impairment.

Mr. Almquist and his fellow athletic trainers, and Dr. Ho and his physician colleagues, all had been following developments at UPMC’s Sports Medicine Concussion Program since it was established in 2000. The program had evolved to assess and manage diverse facets of concussions, including vision, vestibular, exertion, and medication components—not all of which are fully addressed in clinical practice guidelines and position statements. By 2010, the program was drawing 10,000 patients a year.

Care at UPMC is guided by a clinical neuropsychologist who assesses head injuries and then refers patients on as needed to other members of the team – like a neurovestibular expert for vestibular assessment and therapy, a neuro-optometrist for vision therapy, a physical therapist for exertion training, or a sports medicine physician for medication.

In planning their own concussion center, Dr. Ho and his team visited various programs in the country but homed in on UPMC. They decided to mimic several aspects of UPMC’s approach by providing comprehensive and individualized care, and by having the certified athletic trainers serve as the “quarterbacks.”

“The athletic trainer in our center does all the symptom inventories and history taking, a concussion-focused physical exam, vestibular-ocular-motor screening, and neurocognitive tests if appropriate,” said Dr. Ho.

Dr. Ho or one of his sports medicine physician colleagues then discusses results with the athletic trainer and completes the patient visit – with the trainer – by asking any necessary follow-up questions, probing further with additional evaluation, and writing medication prescriptions when appropriate.

Throughout the course of care – visits occur weekly to monthly and often last 30-90 minutes – the athletic trainer and physician work together on clinical issues such as sleep and mental health and on subtyping headaches (cognitive fatigue, cervicogenic, or migrainelike) and “determining where the headaches lie relative to other areas of dysfunction,” said Dr. Ho.

Much of the individualized counseling, monitoring, and coordination that’s required to address sleep hygiene, rest, nutrition, and graded return to physical and cognitive activity can be led by the athletic trainer, he said.

For the first year or so, patients were referred out for such special services as vision or vestibular therapy. But there were problems with this approach: One frequent issue was poor insurance coverage for these therapies. Another was the stress involved in getting to additional appointments on Fairfax’s congested roads. “Traffic and busy environments aren’t always tolerable for a concussed patient,” Dr. Ho said.

Dr. Ho searched the Internet, worked the phone, read the neuro-optometry and vestibular therapy literature, and attended conferences to learn what kinds of therapeutic exercises they could integrate into office visits and take-home care plans. Dr. Ho said he was “surprised at how willing some of [their] colleagues were to give us some basic skills” to help patients who “don’t all need the Cadillac version” of therapy.

About the same time they integrated basic vision and vestibular therapy, they also revamped their billing strategy, moving away from the use of prolonged service billing codes, which Dr. Ho said were frequently denied on the first submission, to using separate codes for the encounter, therapeutic exercise (which encompasses vision therapy and vestibular therapy), and various physical tests.

Concussion care networks

Fairfax Family Practice is not the only practice to center its concussion program on physician-athletic trainer partnerships. Carolina Family Practice and Sports Medicine, a 12-provider practice with three offices in and around Raleigh, N.C., took a similar approach when it established its concussion clinic in 2008.

“Concussion is the ultimate example of an injury that benefits from a team approach,” said Dr. Josh Bloom, medical director of the Carolina Sports Concussion Clinic that is embedded into the practice. “And it’s the one injury – the only injury in sports medicine – where the standard of care calls for the injury to be 100% resolved prior to being cleared to return to play.”

Dr. Jaffe, the family physician in Delaware, said she is fortunate to have a neuro-optometrist practicing in the medical building where her three-physician family practice resides, and a concussion care team in the nearby Nemours/Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, also in Wilmington.

Someday, she and others hope, physicians who see patients soon after injury will have tools to better predict clinical trajectories and identify who could benefit from earlier referral to a “more sophisticated team.”

For now, Dr. Jaffe said, she seeks assistance when headache and initial symptoms persist after 2-3 weeks or when their symptoms “seem out of proportion to the incident.”

Dr. Scott Ross of Novant Health Bull Run Family Medicine based in Manassas, Va., said that family physicians are well suited to guide management and should learn to evaluate each patient’s concussion-related impairments as thoroughly as possible.

About 3 years ago, he and a partner established an official “Sports Medicine and Concussion Management” service line in their practice. “We don’t have a concussion center all under one roof, but we have the knowledge, skills, and resources that we need,” he said.

This article was updated April 13, 2015.

The Fairfax Family Practice Comprehensive Concussion Center is an example of what dedicated physicians can accomplish when they undertake to improve upon an accepted medical approach to a health problem because it falls far short of effective. The concussion center’s hall wall is adorned with a broad and colorful sign autographed by scores of patients – many of them student-athletes – who have been cleared to return to their sports and activities and to lives free of restrictions and struggle following concussion.

Dr. Garry W.K. Ho, the double-credentialed family practice and sports medicine physician who directs the 2-year-old concussion center in Fairfax, Va., takes pride in the skills his team has acquired to facilitate these recoveries.

He and his colleagues within the practice’s sports medicine division established the center, teaming up with several certified athletic trainers, to meet what they saw as a growing, urgent need: to help concussed patients who were taking longer than the oft-mentioned 7-10 days or 2 weeks to heal.

“While many of the people we’d been treating in the clinic with typical 15- to 30-minute appointments and relatively simple follow-up were able to get better, there was clearly a subset of the population that was more complicated and needed a more dedicated, multidimensional approach,” Dr. Ho said.

Findings from a growing number of studies have shown that concussions can involve a vast array of deficits – problems with the vestibular and vision systems, for example – and that a more comprehensive initial evaluation and a multipronged approach to management could shorten recovery time for any individual with the brain injury, he said.

“We’d started to realize how much patients can benefit from new and creative approaches,” said Dr. Ho. “We were also appreciating that no one person can own this disorder. You can’t say that only the neurologist can treat a concussion, or only the family physician or sports medicine physician.

‘Silent epidemic’

A small but growing number of concussion-care programs and clinics are being established across the country. Most often, the programs are incorporated into hospitals and sports medicine clinics. But some, like the program Dr. Ho leads, are embedded within larger primary care practices with a sports medicine component.

And, in other traditional family practices, some physicians are deepening their knowledge of concussions and building the networks necessary for managing prolonged impairment.

“If we have a good understanding of brain injury, we can often facilitate recovery and help [our patients] get back on track seamlessly,” said Dr. Rebecca Jaffe, a family physician in Wilmington, Del. “And when recovery is protracted, when issues don’t resolve in 2-3 weeks, there’s often more to the situation than is initially apparent, and it’s often better that we have a team of individuals who can help us.”

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), there are not enough data for an accurate estimate of the incidence of sports-related concussions in youth (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2014. Sports-related concussions in youth: Improving the science, changing the culture. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.)

But among high school athletes, an increase in concussions has been documented in several emergency department studies and other longitudinal studies published over the past 7-8 years. Most recently, the first national study to look at trends among high school athletes showed the numbers of concussions reported by certified athletic trainers increasing from 0.23/1,000 athlete-exposures in the 2005-2006 academic year to 0.51/1,000 in the 2011-2012 academic year (Am. J. Sports Med. 2014;42:1710-5).

Experts attribute such increases largely to improved awareness and new state laws. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s launched its “Heads Up” educational program in 2004, for instance. And as of last year, every state and the District of Columbia had enacted at least one law to protect young athletes with concussions.

State concussion laws vary, but most require that parents, athletes, and coaches be educated about concussions, and that athletes with suspected concussions be evaluated and cleared by a health care professional with knowledge in concussions before returning to play.

It is likely, some experts say, that the upward curve is leveling off with improved awareness and diagnosis. But with such improvements there lurks a void of data on concussions in youth outside the realm of high school sports. And, according to the 2014 IOM report, the acute and long-term health threat from concussions is “not fully appreciated or acted upon” in many settings. “Kids are getting removed from play more frequently, but then it’s not really clear what anyone should do after that,” said Dr. Shireen Atabaki, an emergency medicine specialist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, who is leading several national initiatives to improve concussion care.

Too often, concussed children and teens receive little besides unnecessary CT scans in emergency departments and concussions go undiagnosed. And when concussions are diagnosed, discharge instructions are poor and “kids are sent out into a no-man’s land” where recovery is often poorly managed, she said.

When Dr. Ho and his colleagues opened their concussion center in March 2013, they began seeing patients who remained symptomatic after concussions that had occurred 6-12 months ago, and longer. “It was almost like a silent epidemic,” he said. “We had one young woman who’d been injured in her senior year of high school and was still symptomatic after 2 years.”

To build the program at Fairfax Family Practice, Dr. Ho and his colleagues, Dr. Thomas Howard and Dr. Marc Childress (who, like Dr. Ho, are board certified in sports medicine as well as family medicine), capitalized on what they saw as a valuable synergy with high school athletic trainers.

Dr. Ho had worked closely with athletic trainers as a volunteer medical adviser to the Fairfax County Public School System’s athletic training program, which provides care to student-athletes in 25 high schools. He drew on his relationships to recruit three athletic trainers who were at transition points in their careers and who had both experience and “passion” in the treatment of concussions.

One of them, Jon Almquist, VATL, ATC, had led the development of return-to-learn protocols and other management practices for the high schools. He had also partnered with investigators at MedStar Health Research Institute in Baltimore on research that documented a 4.2-fold increase in concussions among the school system’s high school athletes between 1997 and 2008 (Am. J. Sports Med. 2011;39:958-63).

More surprising than this increase, however, were some data collected after the study period ended. When Mr. Almquist looked at recovery times for the concussions reported between 2011 and 2013, he found that about 25% of concussions took 30 days or longer to recover – a portion greater than he’d seen anywhere in the literature.

According to the 2014 IOM report, youth athletes typically recover from a concussion within 2 weeks of the injury, but in 10-20% of cases the symptoms persist for a number of weeks, months, or even years.

“Families would come to us for advice,” Mr. Almquist recalled. Other than referring them to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s (UPMC) Sports Medicine Concussion Program, there were few local providers whom they believed offered comprehensive care and had experience with prolonged impairment.

Mr. Almquist and his fellow athletic trainers, and Dr. Ho and his physician colleagues, all had been following developments at UPMC’s Sports Medicine Concussion Program since it was established in 2000. The program had evolved to assess and manage diverse facets of concussions, including vision, vestibular, exertion, and medication components—not all of which are fully addressed in clinical practice guidelines and position statements. By 2010, the program was drawing 10,000 patients a year.

Care at UPMC is guided by a clinical neuropsychologist who assesses head injuries and then refers patients on as needed to other members of the team – like a neurovestibular expert for vestibular assessment and therapy, a neuro-optometrist for vision therapy, a physical therapist for exertion training, or a sports medicine physician for medication.

In planning their own concussion center, Dr. Ho and his team visited various programs in the country but homed in on UPMC. They decided to mimic several aspects of UPMC’s approach by providing comprehensive and individualized care, and by having the certified athletic trainers serve as the “quarterbacks.”

“The athletic trainer in our center does all the symptom inventories and history taking, a concussion-focused physical exam, vestibular-ocular-motor screening, and neurocognitive tests if appropriate,” said Dr. Ho.

Dr. Ho or one of his sports medicine physician colleagues then discusses results with the athletic trainer and completes the patient visit – with the trainer – by asking any necessary follow-up questions, probing further with additional evaluation, and writing medication prescriptions when appropriate.

Throughout the course of care – visits occur weekly to monthly and often last 30-90 minutes – the athletic trainer and physician work together on clinical issues such as sleep and mental health and on subtyping headaches (cognitive fatigue, cervicogenic, or migrainelike) and “determining where the headaches lie relative to other areas of dysfunction,” said Dr. Ho.

Much of the individualized counseling, monitoring, and coordination that’s required to address sleep hygiene, rest, nutrition, and graded return to physical and cognitive activity can be led by the athletic trainer, he said.

For the first year or so, patients were referred out for such special services as vision or vestibular therapy. But there were problems with this approach: One frequent issue was poor insurance coverage for these therapies. Another was the stress involved in getting to additional appointments on Fairfax’s congested roads. “Traffic and busy environments aren’t always tolerable for a concussed patient,” Dr. Ho said.

Dr. Ho searched the Internet, worked the phone, read the neuro-optometry and vestibular therapy literature, and attended conferences to learn what kinds of therapeutic exercises they could integrate into office visits and take-home care plans. Dr. Ho said he was “surprised at how willing some of [their] colleagues were to give us some basic skills” to help patients who “don’t all need the Cadillac version” of therapy.

About the same time they integrated basic vision and vestibular therapy, they also revamped their billing strategy, moving away from the use of prolonged service billing codes, which Dr. Ho said were frequently denied on the first submission, to using separate codes for the encounter, therapeutic exercise (which encompasses vision therapy and vestibular therapy), and various physical tests.

Concussion care networks

Fairfax Family Practice is not the only practice to center its concussion program on physician-athletic trainer partnerships. Carolina Family Practice and Sports Medicine, a 12-provider practice with three offices in and around Raleigh, N.C., took a similar approach when it established its concussion clinic in 2008.

“Concussion is the ultimate example of an injury that benefits from a team approach,” said Dr. Josh Bloom, medical director of the Carolina Sports Concussion Clinic that is embedded into the practice. “And it’s the one injury – the only injury in sports medicine – where the standard of care calls for the injury to be 100% resolved prior to being cleared to return to play.”

Dr. Jaffe, the family physician in Delaware, said she is fortunate to have a neuro-optometrist practicing in the medical building where her three-physician family practice resides, and a concussion care team in the nearby Nemours/Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, also in Wilmington.

Someday, she and others hope, physicians who see patients soon after injury will have tools to better predict clinical trajectories and identify who could benefit from earlier referral to a “more sophisticated team.”

For now, Dr. Jaffe said, she seeks assistance when headache and initial symptoms persist after 2-3 weeks or when their symptoms “seem out of proportion to the incident.”

Dr. Scott Ross of Novant Health Bull Run Family Medicine based in Manassas, Va., said that family physicians are well suited to guide management and should learn to evaluate each patient’s concussion-related impairments as thoroughly as possible.

About 3 years ago, he and a partner established an official “Sports Medicine and Concussion Management” service line in their practice. “We don’t have a concussion center all under one roof, but we have the knowledge, skills, and resources that we need,” he said.

This article was updated April 13, 2015.

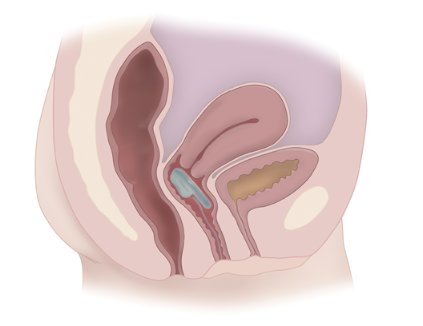

Women Are Not Seeking Care for Urinary Incontinence

WASHINGTON – Women are not seeking care for even moderate to severe urinary incontinence because they have a fear of treatment and lack knowledge of the etiology of the condition and available treatment options, according to a qualitative focus group study at Kaiser Permanente Orange County (Calif.).

Embarrassment is another barrier. So are physicians themselves, said Dr. Jennifer K. Lee, a urogynecologist at Kaiser in Anaheim, Calif., who reported the findings at the annual meeting of the American Urogynecologic Society.

"Providers were mentioned (in the focus groups) to be barriers," Dr. Lee said. "Patients were either dismissed, or they were given misinformation."

By 2050, an estimated 50 million Americans will have urinary incontinence. Previous research has shown, however, that less than 50% of women with moderate incontinence seek care.

The focus group study involved 19 women – 11 who had not sought care but were found after recruitment to have moderate to severe incontinence by the Sandvik severity index, and 8 who had previous treatment or had been evaluated for urinary incontinence.

A moderator led discussions among small groups of these women, all of whom were fluent in English and most of whom (90%) had a college education or higher. The participants were of varying ethnicities, including Caucasian, Hispanic, and Asian.

A fear of medical or surgical treatment, including medication side effects and recovery time for surgery, was one of the themes to emerge. Women also said they felt embarrassed and were therefore not likely to raise the issue, particularly with time constraints in their medical visits.

There was a prevailing idea that urinary incontinence is a normal part of aging or childbearing, or that it is hereditary, and that other health issues take priority. Physicians, moreover, did not ask about the issue, and in cases in which it was mentioned, physicians were dismissive or gave misinformation, the study showed.

Dr. Lee said the barriers are significant, and that "there’s a lot of work to be done" to facilitate communication and change practices.

Leaders at Kaiser Permanente Orange County, Anaheim, Calif., plan to give physicians question prompts to incorporate into routine and primary care visits, she noted during a press conference at the meeting. "We also want to work on educational tools for the public," she said.

"There are urinary incontinence questions [for] the Medicare wellness visit, but these are for women over 65," she said. "There certainly are plenty of women under 65 who have incontinence."

Food and Drug Administration warnings about complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh did not come up in the focus group discussions, but Dr. Lee said that in her practice she has seen this controversy feed patients’ fear of incontinence and its treatment.

Study participants were recruited through e-mail research announcements and flyers, as well as more actively through the offices of urogynecology providers.

Dr. Lee said she had no disclosures to report. Her coauthors and research colleagues at the University of California, Irvine, reported numerous disclosures ranging from speakers’ bureau participation and consulting fees at Hospira and Cadence Pharmaceuticals to consultant positions with Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

WASHINGTON – Women are not seeking care for even moderate to severe urinary incontinence because they have a fear of treatment and lack knowledge of the etiology of the condition and available treatment options, according to a qualitative focus group study at Kaiser Permanente Orange County (Calif.).

Embarrassment is another barrier. So are physicians themselves, said Dr. Jennifer K. Lee, a urogynecologist at Kaiser in Anaheim, Calif., who reported the findings at the annual meeting of the American Urogynecologic Society.

"Providers were mentioned (in the focus groups) to be barriers," Dr. Lee said. "Patients were either dismissed, or they were given misinformation."

By 2050, an estimated 50 million Americans will have urinary incontinence. Previous research has shown, however, that less than 50% of women with moderate incontinence seek care.

The focus group study involved 19 women – 11 who had not sought care but were found after recruitment to have moderate to severe incontinence by the Sandvik severity index, and 8 who had previous treatment or had been evaluated for urinary incontinence.

A moderator led discussions among small groups of these women, all of whom were fluent in English and most of whom (90%) had a college education or higher. The participants were of varying ethnicities, including Caucasian, Hispanic, and Asian.

A fear of medical or surgical treatment, including medication side effects and recovery time for surgery, was one of the themes to emerge. Women also said they felt embarrassed and were therefore not likely to raise the issue, particularly with time constraints in their medical visits.

There was a prevailing idea that urinary incontinence is a normal part of aging or childbearing, or that it is hereditary, and that other health issues take priority. Physicians, moreover, did not ask about the issue, and in cases in which it was mentioned, physicians were dismissive or gave misinformation, the study showed.

Dr. Lee said the barriers are significant, and that "there’s a lot of work to be done" to facilitate communication and change practices.

Leaders at Kaiser Permanente Orange County, Anaheim, Calif., plan to give physicians question prompts to incorporate into routine and primary care visits, she noted during a press conference at the meeting. "We also want to work on educational tools for the public," she said.

"There are urinary incontinence questions [for] the Medicare wellness visit, but these are for women over 65," she said. "There certainly are plenty of women under 65 who have incontinence."

Food and Drug Administration warnings about complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh did not come up in the focus group discussions, but Dr. Lee said that in her practice she has seen this controversy feed patients’ fear of incontinence and its treatment.

Study participants were recruited through e-mail research announcements and flyers, as well as more actively through the offices of urogynecology providers.

Dr. Lee said she had no disclosures to report. Her coauthors and research colleagues at the University of California, Irvine, reported numerous disclosures ranging from speakers’ bureau participation and consulting fees at Hospira and Cadence Pharmaceuticals to consultant positions with Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

WASHINGTON – Women are not seeking care for even moderate to severe urinary incontinence because they have a fear of treatment and lack knowledge of the etiology of the condition and available treatment options, according to a qualitative focus group study at Kaiser Permanente Orange County (Calif.).

Embarrassment is another barrier. So are physicians themselves, said Dr. Jennifer K. Lee, a urogynecologist at Kaiser in Anaheim, Calif., who reported the findings at the annual meeting of the American Urogynecologic Society.

"Providers were mentioned (in the focus groups) to be barriers," Dr. Lee said. "Patients were either dismissed, or they were given misinformation."

By 2050, an estimated 50 million Americans will have urinary incontinence. Previous research has shown, however, that less than 50% of women with moderate incontinence seek care.

The focus group study involved 19 women – 11 who had not sought care but were found after recruitment to have moderate to severe incontinence by the Sandvik severity index, and 8 who had previous treatment or had been evaluated for urinary incontinence.

A moderator led discussions among small groups of these women, all of whom were fluent in English and most of whom (90%) had a college education or higher. The participants were of varying ethnicities, including Caucasian, Hispanic, and Asian.

A fear of medical or surgical treatment, including medication side effects and recovery time for surgery, was one of the themes to emerge. Women also said they felt embarrassed and were therefore not likely to raise the issue, particularly with time constraints in their medical visits.

There was a prevailing idea that urinary incontinence is a normal part of aging or childbearing, or that it is hereditary, and that other health issues take priority. Physicians, moreover, did not ask about the issue, and in cases in which it was mentioned, physicians were dismissive or gave misinformation, the study showed.

Dr. Lee said the barriers are significant, and that "there’s a lot of work to be done" to facilitate communication and change practices.

Leaders at Kaiser Permanente Orange County, Anaheim, Calif., plan to give physicians question prompts to incorporate into routine and primary care visits, she noted during a press conference at the meeting. "We also want to work on educational tools for the public," she said.

"There are urinary incontinence questions [for] the Medicare wellness visit, but these are for women over 65," she said. "There certainly are plenty of women under 65 who have incontinence."

Food and Drug Administration warnings about complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh did not come up in the focus group discussions, but Dr. Lee said that in her practice she has seen this controversy feed patients’ fear of incontinence and its treatment.

Study participants were recruited through e-mail research announcements and flyers, as well as more actively through the offices of urogynecology providers.

Dr. Lee said she had no disclosures to report. Her coauthors and research colleagues at the University of California, Irvine, reported numerous disclosures ranging from speakers’ bureau participation and consulting fees at Hospira and Cadence Pharmaceuticals to consultant positions with Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

AT THE AUGS ANNUAL MEETING

Mediolateral episiotomy shines in 10-year Netherlands analysis

WASHINGTON – The use of mediolateral episiotomy in women undergoing operative vaginal delivery – a common practice in the Netherlands – was associated with a large reduction in the risk of obstetrical anal sphincter injuries, according to an analysis of 10 years of data from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry.

For physicians and other obstetrical providers in the small European country, the findings reinforce current practice of favoring mediolateral episiotomies in operative vaginal deliveries as protection against obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) – a risk factor for fecal incontinence, the investigators said.

"In the Netherlands, a mediolateral episiotomy is common practice. ... Our opinion is that the mediolateral episiotomies are causing less morbidity than an anal sphincter rupture would cause," Dr. Jeroen van Bavel reported during a press conference at the scientific meetings of the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the International Urogynecological Association.

But for physicians here in the United States, the risks are weighed differently. "It’s not that we don’t know that a mediolateral episiotomy decreases the risk of sphincter injury," Dr. Haywood Brown, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in a telephone interview after the conference.

"The problem is, mediolateral incisions are so uncomfortable," said Dr. Brown, who also is chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IV.

"They heal poorly, they heal with defects, ... and as a result the patient has more pain related to the mediolateral [episiotomy] than they would have with a third- or fourth-degree tear," he said. "Doing the mediolateral is really not the answer."

The Netherlands Perinatal Registry contains information on 96% of the 1.5 million deliveries that occurred during 2000-2009. Dr. van Bavel, of Amphia Hospital in Breda, the Netherlands, and his coinvestigators focused their analysis on the 170,974 women who had operative vaginal deliveries, comparing the rates of OASIS in women who had mediolateral episiotomies with those who did not.

Among primiparous women who had vacuum deliveries, OASIS occurred in 2.5% of those who had mediolateral episiotomies, compared with 14% who did not. Among multiparous women who had vacuum deliveries, OASIS rates were 2.1% with mediolateral episiotomy versus 7.5% without.

The differences were more striking with forceps deliveries. Anal sphincter injuries occurred in 3.4% versus 26.7% in primiparous women with and without mediolateral episiotomies, respectively. Among multiparous women, the risk of OASIS was 2.6% versus 14.2%.

For primiparous women, the number of mediolateral episiotomies needed to prevent one OASIS was 8 for vacuum delivery and 4 for forceps delivery, according to the analysis. For multiparous women, 18 mediolateral episiotomies were needed to prevent one OASIS for vacuum delivery, and 8 for forceps delivery.

ACOG’s Practice Bulletin No. 71 on episiotomy, which was written in 2006 (Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;107:957-62) and reaffirmed in 2013, states that median episiotomy is associated with higher rates of injury to the anal sphincter and rectum than mediolateral episiotomy (level A evidence), and that mediolateral episiotomy may be preferable in selected cases (level B evidence).

Overall, "restricted use of episiotomy is preferable to routine use of episiotomy," the guidelines say (level A evidence). Postpartum recovery, the guidelines note, is an area of obstetrics that lacks systematic study and analysis.

Dr. Brown said he stands firmly with his belief that mediolateral episiotomy as a routine prophylactic procedure in operative vaginal deliveries cannot be justified. "Having lived through an era of mediolaterals and seeing how long they take to heal, and the discomfort that patients have, I can’t justify it," he said.

"We’ve moved away from episiotomies [in the United States], period," he said. "We’ve moved away from them primarily because of the data showing that midline episiotomies increase the risk of sphincter injury. And the mediolateral episiotomies are just too painful."

The risk of OASIS can be minimized through good delivery technique, he noted.

"The trend here is toward more vacuum deliveries, which have [been shown to be less risky] than forceps deliveries, although its depends on the type of forceps used and the skill of the [obstetrician]," Dr. Brown said. "The challenge we face is that we don’t have enough forceps and vacuum deliveries to easily keep skill levels up."

Dr. Charles W. Nager, president of AUGS and director the urogynecological and reconstructive pelvic surgery division at the University of California, San Diego, said that rates of both episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery have been declining in the United States, and that simultaneously, "there’s been a parallel drop in OASIS."

There also is more training ongoing in U.S. hospitals on repairing third- and fourth-degree obstetric lacerations, he said in an interview at the meeting.

The Netherlands analysis excluded women with preterm delivery, stillbirth, multiple gestation, transverse position, and breech delivery, as well as women whose deliveries involved both forceps and vacuum and women who had a midline episiotomy.

Factors controlled for in the study included parity, fetal position, birth weight, augmentation with oxytocin, and duration of the second stage of labor.

Dr. van Bavel and all but one of his coinvestigators reported no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The use of mediolateral episiotomy in women undergoing operative vaginal delivery – a common practice in the Netherlands – was associated with a large reduction in the risk of obstetrical anal sphincter injuries, according to an analysis of 10 years of data from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry.

For physicians and other obstetrical providers in the small European country, the findings reinforce current practice of favoring mediolateral episiotomies in operative vaginal deliveries as protection against obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) – a risk factor for fecal incontinence, the investigators said.

"In the Netherlands, a mediolateral episiotomy is common practice. ... Our opinion is that the mediolateral episiotomies are causing less morbidity than an anal sphincter rupture would cause," Dr. Jeroen van Bavel reported during a press conference at the scientific meetings of the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the International Urogynecological Association.

But for physicians here in the United States, the risks are weighed differently. "It’s not that we don’t know that a mediolateral episiotomy decreases the risk of sphincter injury," Dr. Haywood Brown, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in a telephone interview after the conference.

"The problem is, mediolateral incisions are so uncomfortable," said Dr. Brown, who also is chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IV.

"They heal poorly, they heal with defects, ... and as a result the patient has more pain related to the mediolateral [episiotomy] than they would have with a third- or fourth-degree tear," he said. "Doing the mediolateral is really not the answer."

The Netherlands Perinatal Registry contains information on 96% of the 1.5 million deliveries that occurred during 2000-2009. Dr. van Bavel, of Amphia Hospital in Breda, the Netherlands, and his coinvestigators focused their analysis on the 170,974 women who had operative vaginal deliveries, comparing the rates of OASIS in women who had mediolateral episiotomies with those who did not.

Among primiparous women who had vacuum deliveries, OASIS occurred in 2.5% of those who had mediolateral episiotomies, compared with 14% who did not. Among multiparous women who had vacuum deliveries, OASIS rates were 2.1% with mediolateral episiotomy versus 7.5% without.

The differences were more striking with forceps deliveries. Anal sphincter injuries occurred in 3.4% versus 26.7% in primiparous women with and without mediolateral episiotomies, respectively. Among multiparous women, the risk of OASIS was 2.6% versus 14.2%.

For primiparous women, the number of mediolateral episiotomies needed to prevent one OASIS was 8 for vacuum delivery and 4 for forceps delivery, according to the analysis. For multiparous women, 18 mediolateral episiotomies were needed to prevent one OASIS for vacuum delivery, and 8 for forceps delivery.

ACOG’s Practice Bulletin No. 71 on episiotomy, which was written in 2006 (Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;107:957-62) and reaffirmed in 2013, states that median episiotomy is associated with higher rates of injury to the anal sphincter and rectum than mediolateral episiotomy (level A evidence), and that mediolateral episiotomy may be preferable in selected cases (level B evidence).

Overall, "restricted use of episiotomy is preferable to routine use of episiotomy," the guidelines say (level A evidence). Postpartum recovery, the guidelines note, is an area of obstetrics that lacks systematic study and analysis.

Dr. Brown said he stands firmly with his belief that mediolateral episiotomy as a routine prophylactic procedure in operative vaginal deliveries cannot be justified. "Having lived through an era of mediolaterals and seeing how long they take to heal, and the discomfort that patients have, I can’t justify it," he said.

"We’ve moved away from episiotomies [in the United States], period," he said. "We’ve moved away from them primarily because of the data showing that midline episiotomies increase the risk of sphincter injury. And the mediolateral episiotomies are just too painful."

The risk of OASIS can be minimized through good delivery technique, he noted.

"The trend here is toward more vacuum deliveries, which have [been shown to be less risky] than forceps deliveries, although its depends on the type of forceps used and the skill of the [obstetrician]," Dr. Brown said. "The challenge we face is that we don’t have enough forceps and vacuum deliveries to easily keep skill levels up."

Dr. Charles W. Nager, president of AUGS and director the urogynecological and reconstructive pelvic surgery division at the University of California, San Diego, said that rates of both episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery have been declining in the United States, and that simultaneously, "there’s been a parallel drop in OASIS."

There also is more training ongoing in U.S. hospitals on repairing third- and fourth-degree obstetric lacerations, he said in an interview at the meeting.

The Netherlands analysis excluded women with preterm delivery, stillbirth, multiple gestation, transverse position, and breech delivery, as well as women whose deliveries involved both forceps and vacuum and women who had a midline episiotomy.

Factors controlled for in the study included parity, fetal position, birth weight, augmentation with oxytocin, and duration of the second stage of labor.

Dr. van Bavel and all but one of his coinvestigators reported no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The use of mediolateral episiotomy in women undergoing operative vaginal delivery – a common practice in the Netherlands – was associated with a large reduction in the risk of obstetrical anal sphincter injuries, according to an analysis of 10 years of data from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry.

For physicians and other obstetrical providers in the small European country, the findings reinforce current practice of favoring mediolateral episiotomies in operative vaginal deliveries as protection against obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) – a risk factor for fecal incontinence, the investigators said.

"In the Netherlands, a mediolateral episiotomy is common practice. ... Our opinion is that the mediolateral episiotomies are causing less morbidity than an anal sphincter rupture would cause," Dr. Jeroen van Bavel reported during a press conference at the scientific meetings of the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the International Urogynecological Association.

But for physicians here in the United States, the risks are weighed differently. "It’s not that we don’t know that a mediolateral episiotomy decreases the risk of sphincter injury," Dr. Haywood Brown, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in a telephone interview after the conference.

"The problem is, mediolateral incisions are so uncomfortable," said Dr. Brown, who also is chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IV.

"They heal poorly, they heal with defects, ... and as a result the patient has more pain related to the mediolateral [episiotomy] than they would have with a third- or fourth-degree tear," he said. "Doing the mediolateral is really not the answer."

The Netherlands Perinatal Registry contains information on 96% of the 1.5 million deliveries that occurred during 2000-2009. Dr. van Bavel, of Amphia Hospital in Breda, the Netherlands, and his coinvestigators focused their analysis on the 170,974 women who had operative vaginal deliveries, comparing the rates of OASIS in women who had mediolateral episiotomies with those who did not.

Among primiparous women who had vacuum deliveries, OASIS occurred in 2.5% of those who had mediolateral episiotomies, compared with 14% who did not. Among multiparous women who had vacuum deliveries, OASIS rates were 2.1% with mediolateral episiotomy versus 7.5% without.

The differences were more striking with forceps deliveries. Anal sphincter injuries occurred in 3.4% versus 26.7% in primiparous women with and without mediolateral episiotomies, respectively. Among multiparous women, the risk of OASIS was 2.6% versus 14.2%.

For primiparous women, the number of mediolateral episiotomies needed to prevent one OASIS was 8 for vacuum delivery and 4 for forceps delivery, according to the analysis. For multiparous women, 18 mediolateral episiotomies were needed to prevent one OASIS for vacuum delivery, and 8 for forceps delivery.

ACOG’s Practice Bulletin No. 71 on episiotomy, which was written in 2006 (Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;107:957-62) and reaffirmed in 2013, states that median episiotomy is associated with higher rates of injury to the anal sphincter and rectum than mediolateral episiotomy (level A evidence), and that mediolateral episiotomy may be preferable in selected cases (level B evidence).

Overall, "restricted use of episiotomy is preferable to routine use of episiotomy," the guidelines say (level A evidence). Postpartum recovery, the guidelines note, is an area of obstetrics that lacks systematic study and analysis.

Dr. Brown said he stands firmly with his belief that mediolateral episiotomy as a routine prophylactic procedure in operative vaginal deliveries cannot be justified. "Having lived through an era of mediolaterals and seeing how long they take to heal, and the discomfort that patients have, I can’t justify it," he said.

"We’ve moved away from episiotomies [in the United States], period," he said. "We’ve moved away from them primarily because of the data showing that midline episiotomies increase the risk of sphincter injury. And the mediolateral episiotomies are just too painful."

The risk of OASIS can be minimized through good delivery technique, he noted.

"The trend here is toward more vacuum deliveries, which have [been shown to be less risky] than forceps deliveries, although its depends on the type of forceps used and the skill of the [obstetrician]," Dr. Brown said. "The challenge we face is that we don’t have enough forceps and vacuum deliveries to easily keep skill levels up."

Dr. Charles W. Nager, president of AUGS and director the urogynecological and reconstructive pelvic surgery division at the University of California, San Diego, said that rates of both episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery have been declining in the United States, and that simultaneously, "there’s been a parallel drop in OASIS."

There also is more training ongoing in U.S. hospitals on repairing third- and fourth-degree obstetric lacerations, he said in an interview at the meeting.