User login

AAP: High-deductible plans don’t protect children

The American Academy of Pediatrics discourages the use of high-deductible health plans for children, calling the plans inappropriate for young patients and a threat to primary care services. Such plans have a disproportionate impact on poor families and children with special needs who pay more than the healthy under this model, according to a new policy published April 28 in Pediatrics.

High-deductible health plans "put more pressure on those who are ‘just making it,’ " Dr. Budd Norman Shenkin, a member of the AAP Committee on Child Health Financing, said in an interview. "A patient on Medicaid can see a doctor without cost; a patient of a prosperous family can afford the deductible without a problem; the working-class family will need to decide how dangerous it might be to let the child go without medical care. A medical decision becomes an economic decision – ‘Is he $150 sick?’ "

High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) have become more common as employers search for a way to reduce the cost of providing health insurance. A 2013 Kaiser Family Foundation report found that about 20% of employees at small companies were covered by HDHP plans, compared with 4% in 2006. Just over 40% of employees at large companies in 2013 were covered by HDHP plans in 2013, as opposed to 8% in 2006.

The AAP policy notes that while high-deductible health plans decrease health care expenditures, they do so at the cost of quality of care, continuity of care, and accessibility to care, especially for patients of modest means (Pediatrics 2014 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0555]).

By deterring primary care access, HDHPs also inhibit patient-centered medical homes, a critical component of efficient and high-quality health systems, the policy said.

Families insured by HDHPs may choose to take their children to a retail-based clinic for care, rather than the child’s pediatrician to save cost, potentially disrupting proper medical intervention by a pediatrician and compromising quality of care, Dr. Thomas F. Long, chair of the AAP Committee on Child Health Financing, said in an interview.

Families should not have to choose between seeking health care for their children and other essentials such as food, gas, or living expenses, Dr. Long said. Those with the plans also may be slower to pay their out-of-pocket expenses for doctor visits, leading to financial struggles for pediatricians, adds Dr. Long.

"If you’re having trouble collecting that high deductible, that makes it more difficult to run a pediatric office," he said. It affects a "pediatrician’s ability to keep his office open and keep his services available to the community. If those dollars are not coming in because of high deductibles, the sustainability [of a practice] is in jeopardy."

The AAP policy recommends that health savings accounts (HSAs) be included with HDHPs and funded by employers at high levels. Health insurers issuing high-deductible plans should also design procedures that help medical offices and patients better understand the costs and provisions of these plans. The AAP policy calls on the federal government to consider banning high-deductible health plans for those under 18 years. If HDHPs continue to include children, the AAP would like to see insurers define children with certain diagnoses as those with "special needs," using the Department of Health & Human Services’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s definition, thus eliminating the burden of a deductible for such children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics discourages the use of high-deductible health plans for children, calling the plans inappropriate for young patients and a threat to primary care services. Such plans have a disproportionate impact on poor families and children with special needs who pay more than the healthy under this model, according to a new policy published April 28 in Pediatrics.

High-deductible health plans "put more pressure on those who are ‘just making it,’ " Dr. Budd Norman Shenkin, a member of the AAP Committee on Child Health Financing, said in an interview. "A patient on Medicaid can see a doctor without cost; a patient of a prosperous family can afford the deductible without a problem; the working-class family will need to decide how dangerous it might be to let the child go without medical care. A medical decision becomes an economic decision – ‘Is he $150 sick?’ "

High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) have become more common as employers search for a way to reduce the cost of providing health insurance. A 2013 Kaiser Family Foundation report found that about 20% of employees at small companies were covered by HDHP plans, compared with 4% in 2006. Just over 40% of employees at large companies in 2013 were covered by HDHP plans in 2013, as opposed to 8% in 2006.

The AAP policy notes that while high-deductible health plans decrease health care expenditures, they do so at the cost of quality of care, continuity of care, and accessibility to care, especially for patients of modest means (Pediatrics 2014 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0555]).

By deterring primary care access, HDHPs also inhibit patient-centered medical homes, a critical component of efficient and high-quality health systems, the policy said.

Families insured by HDHPs may choose to take their children to a retail-based clinic for care, rather than the child’s pediatrician to save cost, potentially disrupting proper medical intervention by a pediatrician and compromising quality of care, Dr. Thomas F. Long, chair of the AAP Committee on Child Health Financing, said in an interview.

Families should not have to choose between seeking health care for their children and other essentials such as food, gas, or living expenses, Dr. Long said. Those with the plans also may be slower to pay their out-of-pocket expenses for doctor visits, leading to financial struggles for pediatricians, adds Dr. Long.

"If you’re having trouble collecting that high deductible, that makes it more difficult to run a pediatric office," he said. It affects a "pediatrician’s ability to keep his office open and keep his services available to the community. If those dollars are not coming in because of high deductibles, the sustainability [of a practice] is in jeopardy."

The AAP policy recommends that health savings accounts (HSAs) be included with HDHPs and funded by employers at high levels. Health insurers issuing high-deductible plans should also design procedures that help medical offices and patients better understand the costs and provisions of these plans. The AAP policy calls on the federal government to consider banning high-deductible health plans for those under 18 years. If HDHPs continue to include children, the AAP would like to see insurers define children with certain diagnoses as those with "special needs," using the Department of Health & Human Services’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s definition, thus eliminating the burden of a deductible for such children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics discourages the use of high-deductible health plans for children, calling the plans inappropriate for young patients and a threat to primary care services. Such plans have a disproportionate impact on poor families and children with special needs who pay more than the healthy under this model, according to a new policy published April 28 in Pediatrics.

High-deductible health plans "put more pressure on those who are ‘just making it,’ " Dr. Budd Norman Shenkin, a member of the AAP Committee on Child Health Financing, said in an interview. "A patient on Medicaid can see a doctor without cost; a patient of a prosperous family can afford the deductible without a problem; the working-class family will need to decide how dangerous it might be to let the child go without medical care. A medical decision becomes an economic decision – ‘Is he $150 sick?’ "

High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) have become more common as employers search for a way to reduce the cost of providing health insurance. A 2013 Kaiser Family Foundation report found that about 20% of employees at small companies were covered by HDHP plans, compared with 4% in 2006. Just over 40% of employees at large companies in 2013 were covered by HDHP plans in 2013, as opposed to 8% in 2006.

The AAP policy notes that while high-deductible health plans decrease health care expenditures, they do so at the cost of quality of care, continuity of care, and accessibility to care, especially for patients of modest means (Pediatrics 2014 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0555]).

By deterring primary care access, HDHPs also inhibit patient-centered medical homes, a critical component of efficient and high-quality health systems, the policy said.

Families insured by HDHPs may choose to take their children to a retail-based clinic for care, rather than the child’s pediatrician to save cost, potentially disrupting proper medical intervention by a pediatrician and compromising quality of care, Dr. Thomas F. Long, chair of the AAP Committee on Child Health Financing, said in an interview.

Families should not have to choose between seeking health care for their children and other essentials such as food, gas, or living expenses, Dr. Long said. Those with the plans also may be slower to pay their out-of-pocket expenses for doctor visits, leading to financial struggles for pediatricians, adds Dr. Long.

"If you’re having trouble collecting that high deductible, that makes it more difficult to run a pediatric office," he said. It affects a "pediatrician’s ability to keep his office open and keep his services available to the community. If those dollars are not coming in because of high deductibles, the sustainability [of a practice] is in jeopardy."

The AAP policy recommends that health savings accounts (HSAs) be included with HDHPs and funded by employers at high levels. Health insurers issuing high-deductible plans should also design procedures that help medical offices and patients better understand the costs and provisions of these plans. The AAP policy calls on the federal government to consider banning high-deductible health plans for those under 18 years. If HDHPs continue to include children, the AAP would like to see insurers define children with certain diagnoses as those with "special needs," using the Department of Health & Human Services’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s definition, thus eliminating the burden of a deductible for such children.

FROM PEDIATRICS

AACAP disagrees with marijuana legalization, cites harmful effects on children

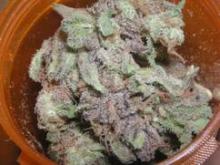

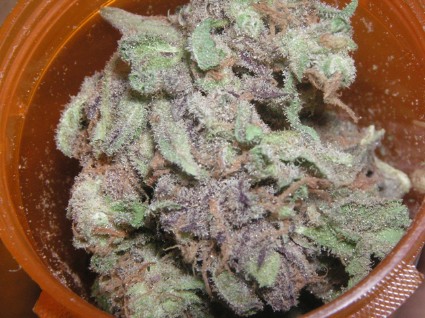

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has released a policy opposing efforts to legalize marijuana.

The AACAP policy statement, released April 15, opposes marijuana legalization while supporting initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of marijuana’s effects on adolescents and improving access to evidence-based treatment, rather than focusing on criminal charges for adolescent users. AACAP also supports the careful monitoring of marijuana-related policy changes on the mental health of children and adolescents.

The policy stresses that significant early use of the drug is associated with increased incidence and worsened psychotic, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders "across the lifespan." In addition, one in six adolescent marijuana users develops cannabis use disorder, a syndrome involving tolerance, withdrawal, and continued marijuana use despite significant associated impairments.

"Often lost in the discussion on marijuana are the concerning potential implications of policy changes on children and adolescents, who are particularly vulnerable to marijuana’s adverse effects," Dr. Kevin Gray, cochair of AACAP’s Substance Abuse and Addiction Committee, said in a statement. "With this in mind, AACAP felt it was critically important to communicate our organization’s position, given our role as advocates for children and adolescent mental health."

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has released a policy opposing efforts to legalize marijuana.

The AACAP policy statement, released April 15, opposes marijuana legalization while supporting initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of marijuana’s effects on adolescents and improving access to evidence-based treatment, rather than focusing on criminal charges for adolescent users. AACAP also supports the careful monitoring of marijuana-related policy changes on the mental health of children and adolescents.

The policy stresses that significant early use of the drug is associated with increased incidence and worsened psychotic, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders "across the lifespan." In addition, one in six adolescent marijuana users develops cannabis use disorder, a syndrome involving tolerance, withdrawal, and continued marijuana use despite significant associated impairments.

"Often lost in the discussion on marijuana are the concerning potential implications of policy changes on children and adolescents, who are particularly vulnerable to marijuana’s adverse effects," Dr. Kevin Gray, cochair of AACAP’s Substance Abuse and Addiction Committee, said in a statement. "With this in mind, AACAP felt it was critically important to communicate our organization’s position, given our role as advocates for children and adolescent mental health."

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has released a policy opposing efforts to legalize marijuana.

The AACAP policy statement, released April 15, opposes marijuana legalization while supporting initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of marijuana’s effects on adolescents and improving access to evidence-based treatment, rather than focusing on criminal charges for adolescent users. AACAP also supports the careful monitoring of marijuana-related policy changes on the mental health of children and adolescents.

The policy stresses that significant early use of the drug is associated with increased incidence and worsened psychotic, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders "across the lifespan." In addition, one in six adolescent marijuana users develops cannabis use disorder, a syndrome involving tolerance, withdrawal, and continued marijuana use despite significant associated impairments.

"Often lost in the discussion on marijuana are the concerning potential implications of policy changes on children and adolescents, who are particularly vulnerable to marijuana’s adverse effects," Dr. Kevin Gray, cochair of AACAP’s Substance Abuse and Addiction Committee, said in a statement. "With this in mind, AACAP felt it was critically important to communicate our organization’s position, given our role as advocates for children and adolescent mental health."

Hospitals: Defensive medicine by physicians common, costly

Hospital administrators estimate more than half of physicians practice defensive medicine and that such unnecessary medical treatment accounts for one-third of all health care costs.

The 2014 analysis by national health care staffing firm Jackson Healthcare corresponds with a 2010 survey by Gallup in which 73% of physicians said they had practiced defensive medicine. In the 2010 survey, physicians estimated 26% of overall health care costs stemmed from defensive medicine.

"We have been studying the reach and impact of defensive medicine for 5 years, and the conclusions are consistent," said Richard L. Jackson, chair and CEO of Jackson Healthcare. "The data show defensive medicine is impacting health care costs and is a uniquely American problem."

Jackson Healthcare examined the responses of 106 hospital executives between February and March for the survey, released April 8. Of participants, 94% said physicians’ fear of lawsuits leads them to practice defensive medicine and in turn elevates health care costs. Hospital administrators estimated an average of 57% of physicians practice defensive medicine. In the 2010 survey, Gallup interviewed 462 physicians across the United States.

Survey participants in the most recent survey were divided on how defensive medicine affects quality of care. Of those surveyed, 32% said defensive medicine has a negative impact, 31% believed it has a positive impact, and 30% said it had no impact.

But "estimates" of defensive medicine may be much different from actual costs, said Dr. Howard Brody, professor and John P. McGovern centennial chair of family medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB), and director for UTMB’s Institute for the Medical Humanities.

"I doubt that the [percentage] of defensive medicine can be shown to be as high as they say [nearly one third]," he said. "There’s a difference between surveys of people’s opinions versus actual attempts to measure defensive medicine."

Dr. Brody coauthored a study in the February 2010 Journal of General Internal Medicine about defensive medicine, cost containment, and reform. The study found the subjective aspects of defensive medicine render the practice nearly impossible to quantify.

"I believe that the basic problem is that physicians seldom do anything for one reason only," Dr. Brody said. "Any test or treatment that’s ordered may be ordered for several reasons, one of which might be defensive medicine, but it’s very hard to disentangle how much that contributes among the various other reasons. The best-conducted studies we could find would produce estimates of the actual cost of preventive medicine far below what this recent survey suggests."

Physicians themselves have long reported practicing defensively to diminish litigation risks. A 2005 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found 93% of high-risk specialists in Pennsylvania reported practicing defensive medicine (JAMA 2005; 293:2609-17). In Massachusetts, 83% of physicians said they have practiced defensive medicine, according to a 2008 report by the Massachusetts Medical Society.

However, Dr. Brody noted the many dynamics play into physicians’ treatment decisions.

"Physicians are, quite understandably, very fearful of lawsuits," he said. "This psychological reaction looms very large in their thinking, and so when asked about defensive medicine, we tend to overestimate its actual scope. I would not boggle at the idea that up to a third of the health care budget is spent on unnecessary things that don’t help patients at all. But I think the main reason physicians order these is because we do what we think we should do, or have been told to do, or feel better if we do more rather than less.

Hospital administrators estimate more than half of physicians practice defensive medicine and that such unnecessary medical treatment accounts for one-third of all health care costs.

The 2014 analysis by national health care staffing firm Jackson Healthcare corresponds with a 2010 survey by Gallup in which 73% of physicians said they had practiced defensive medicine. In the 2010 survey, physicians estimated 26% of overall health care costs stemmed from defensive medicine.

"We have been studying the reach and impact of defensive medicine for 5 years, and the conclusions are consistent," said Richard L. Jackson, chair and CEO of Jackson Healthcare. "The data show defensive medicine is impacting health care costs and is a uniquely American problem."

Jackson Healthcare examined the responses of 106 hospital executives between February and March for the survey, released April 8. Of participants, 94% said physicians’ fear of lawsuits leads them to practice defensive medicine and in turn elevates health care costs. Hospital administrators estimated an average of 57% of physicians practice defensive medicine. In the 2010 survey, Gallup interviewed 462 physicians across the United States.

Survey participants in the most recent survey were divided on how defensive medicine affects quality of care. Of those surveyed, 32% said defensive medicine has a negative impact, 31% believed it has a positive impact, and 30% said it had no impact.

But "estimates" of defensive medicine may be much different from actual costs, said Dr. Howard Brody, professor and John P. McGovern centennial chair of family medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB), and director for UTMB’s Institute for the Medical Humanities.

"I doubt that the [percentage] of defensive medicine can be shown to be as high as they say [nearly one third]," he said. "There’s a difference between surveys of people’s opinions versus actual attempts to measure defensive medicine."

Dr. Brody coauthored a study in the February 2010 Journal of General Internal Medicine about defensive medicine, cost containment, and reform. The study found the subjective aspects of defensive medicine render the practice nearly impossible to quantify.

"I believe that the basic problem is that physicians seldom do anything for one reason only," Dr. Brody said. "Any test or treatment that’s ordered may be ordered for several reasons, one of which might be defensive medicine, but it’s very hard to disentangle how much that contributes among the various other reasons. The best-conducted studies we could find would produce estimates of the actual cost of preventive medicine far below what this recent survey suggests."

Physicians themselves have long reported practicing defensively to diminish litigation risks. A 2005 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found 93% of high-risk specialists in Pennsylvania reported practicing defensive medicine (JAMA 2005; 293:2609-17). In Massachusetts, 83% of physicians said they have practiced defensive medicine, according to a 2008 report by the Massachusetts Medical Society.

However, Dr. Brody noted the many dynamics play into physicians’ treatment decisions.

"Physicians are, quite understandably, very fearful of lawsuits," he said. "This psychological reaction looms very large in their thinking, and so when asked about defensive medicine, we tend to overestimate its actual scope. I would not boggle at the idea that up to a third of the health care budget is spent on unnecessary things that don’t help patients at all. But I think the main reason physicians order these is because we do what we think we should do, or have been told to do, or feel better if we do more rather than less.

Hospital administrators estimate more than half of physicians practice defensive medicine and that such unnecessary medical treatment accounts for one-third of all health care costs.

The 2014 analysis by national health care staffing firm Jackson Healthcare corresponds with a 2010 survey by Gallup in which 73% of physicians said they had practiced defensive medicine. In the 2010 survey, physicians estimated 26% of overall health care costs stemmed from defensive medicine.

"We have been studying the reach and impact of defensive medicine for 5 years, and the conclusions are consistent," said Richard L. Jackson, chair and CEO of Jackson Healthcare. "The data show defensive medicine is impacting health care costs and is a uniquely American problem."

Jackson Healthcare examined the responses of 106 hospital executives between February and March for the survey, released April 8. Of participants, 94% said physicians’ fear of lawsuits leads them to practice defensive medicine and in turn elevates health care costs. Hospital administrators estimated an average of 57% of physicians practice defensive medicine. In the 2010 survey, Gallup interviewed 462 physicians across the United States.

Survey participants in the most recent survey were divided on how defensive medicine affects quality of care. Of those surveyed, 32% said defensive medicine has a negative impact, 31% believed it has a positive impact, and 30% said it had no impact.

But "estimates" of defensive medicine may be much different from actual costs, said Dr. Howard Brody, professor and John P. McGovern centennial chair of family medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB), and director for UTMB’s Institute for the Medical Humanities.

"I doubt that the [percentage] of defensive medicine can be shown to be as high as they say [nearly one third]," he said. "There’s a difference between surveys of people’s opinions versus actual attempts to measure defensive medicine."

Dr. Brody coauthored a study in the February 2010 Journal of General Internal Medicine about defensive medicine, cost containment, and reform. The study found the subjective aspects of defensive medicine render the practice nearly impossible to quantify.

"I believe that the basic problem is that physicians seldom do anything for one reason only," Dr. Brody said. "Any test or treatment that’s ordered may be ordered for several reasons, one of which might be defensive medicine, but it’s very hard to disentangle how much that contributes among the various other reasons. The best-conducted studies we could find would produce estimates of the actual cost of preventive medicine far below what this recent survey suggests."

Physicians themselves have long reported practicing defensively to diminish litigation risks. A 2005 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found 93% of high-risk specialists in Pennsylvania reported practicing defensive medicine (JAMA 2005; 293:2609-17). In Massachusetts, 83% of physicians said they have practiced defensive medicine, according to a 2008 report by the Massachusetts Medical Society.

However, Dr. Brody noted the many dynamics play into physicians’ treatment decisions.

"Physicians are, quite understandably, very fearful of lawsuits," he said. "This psychological reaction looms very large in their thinking, and so when asked about defensive medicine, we tend to overestimate its actual scope. I would not boggle at the idea that up to a third of the health care budget is spent on unnecessary things that don’t help patients at all. But I think the main reason physicians order these is because we do what we think we should do, or have been told to do, or feel better if we do more rather than less.

Wisconsin law shields doctors’ apologies from malpractice cases

Following in the footsteps of more than 35 other states, Wisconsin has become the latest to enact a law protecting apologies by physicians from being used against them in court.

Assembly Bill 120, signed by Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker (R) in April, shields from legal evidence any statement or gesture by doctors that expresses apology, benevolence, compassion, condolence, fault, remorse, or sympathy to a patient or patient’s family.

"We know that people often feel like their doctors abandon them after things go badly," said Dr. Norman Jensen, professor emeritus of internal medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "We know one of the reasons is doctors are afraid of getting sued. [The law’s intent] is that doctors will feel [freer] to go and talk to their patients after an adverse action happens. We know that lawsuits are less likely if doctors would only do that."

The Wisconsin law is part of an ongoing trend among jurisdictions to safeguard physicians who apologize to patients after medical mishaps. At least 37 states have some form of apology law. Most recently Pennsylvania enacted an "I’m sorry" statute in October 2013. While the laws all center on protecting doctors who express sympathy to patients, the laws differ in stringency. Some shield statements of regret or condolence, but do not protect admissions of guilt or fault, Dr. Jensen said. Stronger laws, such as Wisconsin’s, protect both apologetic statements and expressions of fault.

"The weak version [of the law] might be worse than none at all," said Dr. Jensen, who testified in support of the law in the state legislature. "It might mislead physicians into thinking they were protected when they really weren’t."

Apology laws are not without opposition. Plaintiffs’ attorneys across the country have strongly advocated against the protections. The Wisconsin Association for Justice (WAJ) expressed disappointment at its new law, saying the rule prevents patients from proving their medical malpractice claims and gives too much power to the medical community.

"A physician indicating regret for something that has gone wrong is one thing, but to admit to catastrophic carelessness and not be held responsible when you told the truth about what you did is another," WAJ President Christopher Stombaugh said in a statement. "The health care worker said it, people heard them say it, but now we have to go to court and pretend it didn’t happen. If the purpose of the trial is to discover the truth, this law does just the opposite. It hides the truth."

The WAJ supported a less expansive version of the law that would have made statements of regret, sympathy, or benevolence by a health care provider inadmissible in court.

While it is unclear if apology laws lessen litigation against physicians, apology-based initiatives at several U.S. hospitals have demonstrated significant lawsuit reductions. So-called communication and resolution programs involve investigating events in which inappropriate care may have occurred, providing an apology to patients, and offering early compensation if necessary.

Pilot efforts in this area by the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, since 2006 have increased adverse event reports from 1,500 per year to 10,000 while decreasing malpractice premiums by $15 million since 2010.

A similar program that began at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, in 2001 has cut the average legal expenses per case in half, according to the UM website. In July 2001, the health system had 260 pre-suit claims and lawsuits pending; it now averages about 100 per year.

Following in the footsteps of more than 35 other states, Wisconsin has become the latest to enact a law protecting apologies by physicians from being used against them in court.

Assembly Bill 120, signed by Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker (R) in April, shields from legal evidence any statement or gesture by doctors that expresses apology, benevolence, compassion, condolence, fault, remorse, or sympathy to a patient or patient’s family.

"We know that people often feel like their doctors abandon them after things go badly," said Dr. Norman Jensen, professor emeritus of internal medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "We know one of the reasons is doctors are afraid of getting sued. [The law’s intent] is that doctors will feel [freer] to go and talk to their patients after an adverse action happens. We know that lawsuits are less likely if doctors would only do that."

The Wisconsin law is part of an ongoing trend among jurisdictions to safeguard physicians who apologize to patients after medical mishaps. At least 37 states have some form of apology law. Most recently Pennsylvania enacted an "I’m sorry" statute in October 2013. While the laws all center on protecting doctors who express sympathy to patients, the laws differ in stringency. Some shield statements of regret or condolence, but do not protect admissions of guilt or fault, Dr. Jensen said. Stronger laws, such as Wisconsin’s, protect both apologetic statements and expressions of fault.

"The weak version [of the law] might be worse than none at all," said Dr. Jensen, who testified in support of the law in the state legislature. "It might mislead physicians into thinking they were protected when they really weren’t."

Apology laws are not without opposition. Plaintiffs’ attorneys across the country have strongly advocated against the protections. The Wisconsin Association for Justice (WAJ) expressed disappointment at its new law, saying the rule prevents patients from proving their medical malpractice claims and gives too much power to the medical community.

"A physician indicating regret for something that has gone wrong is one thing, but to admit to catastrophic carelessness and not be held responsible when you told the truth about what you did is another," WAJ President Christopher Stombaugh said in a statement. "The health care worker said it, people heard them say it, but now we have to go to court and pretend it didn’t happen. If the purpose of the trial is to discover the truth, this law does just the opposite. It hides the truth."

The WAJ supported a less expansive version of the law that would have made statements of regret, sympathy, or benevolence by a health care provider inadmissible in court.

While it is unclear if apology laws lessen litigation against physicians, apology-based initiatives at several U.S. hospitals have demonstrated significant lawsuit reductions. So-called communication and resolution programs involve investigating events in which inappropriate care may have occurred, providing an apology to patients, and offering early compensation if necessary.

Pilot efforts in this area by the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, since 2006 have increased adverse event reports from 1,500 per year to 10,000 while decreasing malpractice premiums by $15 million since 2010.

A similar program that began at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, in 2001 has cut the average legal expenses per case in half, according to the UM website. In July 2001, the health system had 260 pre-suit claims and lawsuits pending; it now averages about 100 per year.

Following in the footsteps of more than 35 other states, Wisconsin has become the latest to enact a law protecting apologies by physicians from being used against them in court.

Assembly Bill 120, signed by Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker (R) in April, shields from legal evidence any statement or gesture by doctors that expresses apology, benevolence, compassion, condolence, fault, remorse, or sympathy to a patient or patient’s family.

"We know that people often feel like their doctors abandon them after things go badly," said Dr. Norman Jensen, professor emeritus of internal medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "We know one of the reasons is doctors are afraid of getting sued. [The law’s intent] is that doctors will feel [freer] to go and talk to their patients after an adverse action happens. We know that lawsuits are less likely if doctors would only do that."

The Wisconsin law is part of an ongoing trend among jurisdictions to safeguard physicians who apologize to patients after medical mishaps. At least 37 states have some form of apology law. Most recently Pennsylvania enacted an "I’m sorry" statute in October 2013. While the laws all center on protecting doctors who express sympathy to patients, the laws differ in stringency. Some shield statements of regret or condolence, but do not protect admissions of guilt or fault, Dr. Jensen said. Stronger laws, such as Wisconsin’s, protect both apologetic statements and expressions of fault.

"The weak version [of the law] might be worse than none at all," said Dr. Jensen, who testified in support of the law in the state legislature. "It might mislead physicians into thinking they were protected when they really weren’t."

Apology laws are not without opposition. Plaintiffs’ attorneys across the country have strongly advocated against the protections. The Wisconsin Association for Justice (WAJ) expressed disappointment at its new law, saying the rule prevents patients from proving their medical malpractice claims and gives too much power to the medical community.

"A physician indicating regret for something that has gone wrong is one thing, but to admit to catastrophic carelessness and not be held responsible when you told the truth about what you did is another," WAJ President Christopher Stombaugh said in a statement. "The health care worker said it, people heard them say it, but now we have to go to court and pretend it didn’t happen. If the purpose of the trial is to discover the truth, this law does just the opposite. It hides the truth."

The WAJ supported a less expansive version of the law that would have made statements of regret, sympathy, or benevolence by a health care provider inadmissible in court.

While it is unclear if apology laws lessen litigation against physicians, apology-based initiatives at several U.S. hospitals have demonstrated significant lawsuit reductions. So-called communication and resolution programs involve investigating events in which inappropriate care may have occurred, providing an apology to patients, and offering early compensation if necessary.

Pilot efforts in this area by the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, since 2006 have increased adverse event reports from 1,500 per year to 10,000 while decreasing malpractice premiums by $15 million since 2010.

A similar program that began at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, in 2001 has cut the average legal expenses per case in half, according to the UM website. In July 2001, the health system had 260 pre-suit claims and lawsuits pending; it now averages about 100 per year.

ACA coverage may lead to more malpractice claims

The volume of malpractice claims against physicians could increase by 5% as more Americans gain health care coverage and access health services under the Affordable Care Act, according to a study by the RAND Corporation released April 9.

That increase could translate into higher malpractice premiums for physicians, RAND researchers found in a study of the ACA’s impact on all liability insurances.

"The Affordable Care Act is unlikely to dramatically affect liability costs, but it may influence small and moderate changes in costs over the next several years," said lead author David Auerbach, a policy researcher at RAND. "For example, auto insurers may spend less for treating injuries, while it may cost a bit more to provide physicians with medical malpractice coverage."

RAND investigators theorized that a greater number of insured patients would escalate the rate of malpractice lawsuits because of more procedures, interactions, and visits with physicians. Previous analyses have found the uninsured currently use about half of the care that insured patients do, they said.

To test their theory, the researchers compared National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) data on liability claims from 2008 to 2010 to insurance coverage data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS). The results suggested that having insurance coverage is associated with a 2%-10% increase in malpractice activity. Thus, if 10% of a state’s population gains coverage, analysts estimated a 5% rise in malpractice claims.

"This study highlights the far-reaching impacts of the Affordable Care Act," said Jayne Plunkett, head of casualty reinsurance for Swiss Re, an international reinsurance company that sponsored the study. "Businesses and policymakers need to understand how and why their risk profiles might change as the Affordable Care Act is implemented."

But other insurers believe the study results are another uncertain forecast of the ACA’s future effects.

"You’re trying to look through a very cloudy crystal ball in making predictions about the Affordable Care Act," said Frank O’Neil, senior vice president and chief communications officer for ProAssurance, a national medical liability insurer. "There are a number of things that could cause a 5% change in medical liability rates that could happen at the same time as the implementation of the ACA, but be totally unrelated."

For example, if there is a sudden increase in either the frequency or the severity of malpractice claims in a particular state, that could impact the medical liability climate, Mr. O’Neil said. He added that other experts believe that new patients entering the health care system may be so appreciative of previously absent care that they would be reluctant to sue.

"There are a lot of unknowns yet, and I think it’s hard to agree or disagree with a prediction that doesn’t say over what time frame [an increase in claims] would occur," he said. The study "should be taken as just one other prediction."

The volume of malpractice claims against physicians could increase by 5% as more Americans gain health care coverage and access health services under the Affordable Care Act, according to a study by the RAND Corporation released April 9.

That increase could translate into higher malpractice premiums for physicians, RAND researchers found in a study of the ACA’s impact on all liability insurances.

"The Affordable Care Act is unlikely to dramatically affect liability costs, but it may influence small and moderate changes in costs over the next several years," said lead author David Auerbach, a policy researcher at RAND. "For example, auto insurers may spend less for treating injuries, while it may cost a bit more to provide physicians with medical malpractice coverage."

RAND investigators theorized that a greater number of insured patients would escalate the rate of malpractice lawsuits because of more procedures, interactions, and visits with physicians. Previous analyses have found the uninsured currently use about half of the care that insured patients do, they said.

To test their theory, the researchers compared National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) data on liability claims from 2008 to 2010 to insurance coverage data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS). The results suggested that having insurance coverage is associated with a 2%-10% increase in malpractice activity. Thus, if 10% of a state’s population gains coverage, analysts estimated a 5% rise in malpractice claims.

"This study highlights the far-reaching impacts of the Affordable Care Act," said Jayne Plunkett, head of casualty reinsurance for Swiss Re, an international reinsurance company that sponsored the study. "Businesses and policymakers need to understand how and why their risk profiles might change as the Affordable Care Act is implemented."

But other insurers believe the study results are another uncertain forecast of the ACA’s future effects.

"You’re trying to look through a very cloudy crystal ball in making predictions about the Affordable Care Act," said Frank O’Neil, senior vice president and chief communications officer for ProAssurance, a national medical liability insurer. "There are a number of things that could cause a 5% change in medical liability rates that could happen at the same time as the implementation of the ACA, but be totally unrelated."

For example, if there is a sudden increase in either the frequency or the severity of malpractice claims in a particular state, that could impact the medical liability climate, Mr. O’Neil said. He added that other experts believe that new patients entering the health care system may be so appreciative of previously absent care that they would be reluctant to sue.

"There are a lot of unknowns yet, and I think it’s hard to agree or disagree with a prediction that doesn’t say over what time frame [an increase in claims] would occur," he said. The study "should be taken as just one other prediction."

The volume of malpractice claims against physicians could increase by 5% as more Americans gain health care coverage and access health services under the Affordable Care Act, according to a study by the RAND Corporation released April 9.

That increase could translate into higher malpractice premiums for physicians, RAND researchers found in a study of the ACA’s impact on all liability insurances.

"The Affordable Care Act is unlikely to dramatically affect liability costs, but it may influence small and moderate changes in costs over the next several years," said lead author David Auerbach, a policy researcher at RAND. "For example, auto insurers may spend less for treating injuries, while it may cost a bit more to provide physicians with medical malpractice coverage."

RAND investigators theorized that a greater number of insured patients would escalate the rate of malpractice lawsuits because of more procedures, interactions, and visits with physicians. Previous analyses have found the uninsured currently use about half of the care that insured patients do, they said.

To test their theory, the researchers compared National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) data on liability claims from 2008 to 2010 to insurance coverage data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS). The results suggested that having insurance coverage is associated with a 2%-10% increase in malpractice activity. Thus, if 10% of a state’s population gains coverage, analysts estimated a 5% rise in malpractice claims.

"This study highlights the far-reaching impacts of the Affordable Care Act," said Jayne Plunkett, head of casualty reinsurance for Swiss Re, an international reinsurance company that sponsored the study. "Businesses and policymakers need to understand how and why their risk profiles might change as the Affordable Care Act is implemented."

But other insurers believe the study results are another uncertain forecast of the ACA’s future effects.

"You’re trying to look through a very cloudy crystal ball in making predictions about the Affordable Care Act," said Frank O’Neil, senior vice president and chief communications officer for ProAssurance, a national medical liability insurer. "There are a number of things that could cause a 5% change in medical liability rates that could happen at the same time as the implementation of the ACA, but be totally unrelated."

For example, if there is a sudden increase in either the frequency or the severity of malpractice claims in a particular state, that could impact the medical liability climate, Mr. O’Neil said. He added that other experts believe that new patients entering the health care system may be so appreciative of previously absent care that they would be reluctant to sue.

"There are a lot of unknowns yet, and I think it’s hard to agree or disagree with a prediction that doesn’t say over what time frame [an increase in claims] would occur," he said. The study "should be taken as just one other prediction."

Avoiding the RAC: Expert advice

The vast majority of physicians at the center of billing investigations and audits have made accidental errors. Regardless of intent, however, such mistakes fuel lengthy examinations, fines, and, in some cases, civil or criminal charges.

"The overwhelming majority of physicians are good, honorable people trying to take care of patients to the best of their ability. Having said that, ignorance is no excuse" for billing errors, said Mark S. Kopson, chair of Plunkett Cooney’s Health Care Industry Group in Bloomfield Hills, Mich.

Proactive steps to ensure correct billing and recognize early any errors are essential to preventing investigations and defending overbilling accusations, said Heather Greene, vice president of compliance services at Kraft Healthcare Consulting in Nashville, Tenn.

At the February meeting of the American Health Lawyers Association (AHLA) Physicians and Hospitals Law Institute, Ms. Greene discussed recent trends among False Claims Act (FCA) claims and reviews by Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs).

More claims are being seen related to incorrect unit billings for medications, multiple procedures erroneously coded together, and incorrect usage of modifiers, she said. Also, auditors and investigators are quick to scrutinize cases in which physicians fail to clearly link the patient’s presentation to the diagnosis and treatment provided.

"The overarching criteria for all services is medical necessity," Ms. Greene said. "Medicare says it’s the physician’s responsibility to substantiate that treatment was medically necessary. If they don’t write it down, if they don’t connect the dots, then medical necessity could be called into question."

A critical element in avoiding government scrutiny is maintaining a solid compliance plan, said Mr. Kopson. The plan should include regular self-auditing and the comparing of a random sampling of charts to submitted claims.

"If you don’t have the time or expertise in-house to do that, contract with an outside consultant," Mr. Kopson said. "That will be money very well spent."

He also advised ensuring that billers and coders are appropriately trained and have sufficient skill and experience to bill accurately.

Once a payment error is identified, the claim must be refunded within 60 days and the claim must be self-reported if any fraud is involved, said Christopher A. Melton, a health law attorney and partner at Wyatt, Tarrant & Combsin Louisville, Ky. But Mr. Melton notes that federal rules lack clarity on the scope of identification. For example, if 10 claims are examined and the same error is found in all of them, it’s unclear if that sample accounts for the identification of all similar claims submitted, he said.

"The problem is, no one can audit 100% of their charts," said Mr. Melton, who was copresenter of the AHLA session. "Is there a duty to look deeper into these? Those are the questions everyone is going to have to wrestle with."

Nearly as important as preventing billing mistakes is handling audits and billing investigations correctly when they happen. While such examinations can be nerve-wracking, remember to stay calm and refrain from changing or trying to improve records, Mr. Kopson said.

"Do not change any medical records, period," he said. "That is the surest way to lose your audit or civil case and [create] significant risk of incurring criminal liability or licensure sanctions. I’ve seen far too many people get the notice, go into panic mode, and start rewriting history."

If it’s necessary to augment a chart, follow the proper rules for making amendments and additions to notes.

When physicians disagree with the findings of a RAC audit, they should document the dispute and their concerns, even if they chose to repay the claim, Mr. Melton said. This helps strengthen a doctor’s case should there later be an FCA or fraud accusation.

The aid of an experienced health law attorney can allow one to work competently through audits and address overbilling allegations, Ms. Greene added.

"Just like health care, this is a very complex industry," she said. "It’s helpful to have an attorney involved. Sometimes attorneys can have conversations with government attorneys and ask questions physicians may not be able to ask. They have a toolbox that is set up to deal with these kinds of situations."

Mr. Kopson stresses that physicians must accept that "the buck stops" with them when it comes to proper billing and coding.

"It’s no defense that your clerk entered inaccurate information or someone else who was employed by your employer did the coding," he said. "It’s critically important that you know what they are billing for your service. You could wind up in the hot seat very easily. Know the required elements for your most frequently billed codes ... and ensure that you’re documenting accurately all of those elements that you’re performing."

The vast majority of physicians at the center of billing investigations and audits have made accidental errors. Regardless of intent, however, such mistakes fuel lengthy examinations, fines, and, in some cases, civil or criminal charges.

"The overwhelming majority of physicians are good, honorable people trying to take care of patients to the best of their ability. Having said that, ignorance is no excuse" for billing errors, said Mark S. Kopson, chair of Plunkett Cooney’s Health Care Industry Group in Bloomfield Hills, Mich.

Proactive steps to ensure correct billing and recognize early any errors are essential to preventing investigations and defending overbilling accusations, said Heather Greene, vice president of compliance services at Kraft Healthcare Consulting in Nashville, Tenn.

At the February meeting of the American Health Lawyers Association (AHLA) Physicians and Hospitals Law Institute, Ms. Greene discussed recent trends among False Claims Act (FCA) claims and reviews by Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs).

More claims are being seen related to incorrect unit billings for medications, multiple procedures erroneously coded together, and incorrect usage of modifiers, she said. Also, auditors and investigators are quick to scrutinize cases in which physicians fail to clearly link the patient’s presentation to the diagnosis and treatment provided.

"The overarching criteria for all services is medical necessity," Ms. Greene said. "Medicare says it’s the physician’s responsibility to substantiate that treatment was medically necessary. If they don’t write it down, if they don’t connect the dots, then medical necessity could be called into question."

A critical element in avoiding government scrutiny is maintaining a solid compliance plan, said Mr. Kopson. The plan should include regular self-auditing and the comparing of a random sampling of charts to submitted claims.

"If you don’t have the time or expertise in-house to do that, contract with an outside consultant," Mr. Kopson said. "That will be money very well spent."

He also advised ensuring that billers and coders are appropriately trained and have sufficient skill and experience to bill accurately.

Once a payment error is identified, the claim must be refunded within 60 days and the claim must be self-reported if any fraud is involved, said Christopher A. Melton, a health law attorney and partner at Wyatt, Tarrant & Combsin Louisville, Ky. But Mr. Melton notes that federal rules lack clarity on the scope of identification. For example, if 10 claims are examined and the same error is found in all of them, it’s unclear if that sample accounts for the identification of all similar claims submitted, he said.

"The problem is, no one can audit 100% of their charts," said Mr. Melton, who was copresenter of the AHLA session. "Is there a duty to look deeper into these? Those are the questions everyone is going to have to wrestle with."

Nearly as important as preventing billing mistakes is handling audits and billing investigations correctly when they happen. While such examinations can be nerve-wracking, remember to stay calm and refrain from changing or trying to improve records, Mr. Kopson said.

"Do not change any medical records, period," he said. "That is the surest way to lose your audit or civil case and [create] significant risk of incurring criminal liability or licensure sanctions. I’ve seen far too many people get the notice, go into panic mode, and start rewriting history."

If it’s necessary to augment a chart, follow the proper rules for making amendments and additions to notes.

When physicians disagree with the findings of a RAC audit, they should document the dispute and their concerns, even if they chose to repay the claim, Mr. Melton said. This helps strengthen a doctor’s case should there later be an FCA or fraud accusation.

The aid of an experienced health law attorney can allow one to work competently through audits and address overbilling allegations, Ms. Greene added.

"Just like health care, this is a very complex industry," she said. "It’s helpful to have an attorney involved. Sometimes attorneys can have conversations with government attorneys and ask questions physicians may not be able to ask. They have a toolbox that is set up to deal with these kinds of situations."

Mr. Kopson stresses that physicians must accept that "the buck stops" with them when it comes to proper billing and coding.

"It’s no defense that your clerk entered inaccurate information or someone else who was employed by your employer did the coding," he said. "It’s critically important that you know what they are billing for your service. You could wind up in the hot seat very easily. Know the required elements for your most frequently billed codes ... and ensure that you’re documenting accurately all of those elements that you’re performing."

The vast majority of physicians at the center of billing investigations and audits have made accidental errors. Regardless of intent, however, such mistakes fuel lengthy examinations, fines, and, in some cases, civil or criminal charges.

"The overwhelming majority of physicians are good, honorable people trying to take care of patients to the best of their ability. Having said that, ignorance is no excuse" for billing errors, said Mark S. Kopson, chair of Plunkett Cooney’s Health Care Industry Group in Bloomfield Hills, Mich.

Proactive steps to ensure correct billing and recognize early any errors are essential to preventing investigations and defending overbilling accusations, said Heather Greene, vice president of compliance services at Kraft Healthcare Consulting in Nashville, Tenn.

At the February meeting of the American Health Lawyers Association (AHLA) Physicians and Hospitals Law Institute, Ms. Greene discussed recent trends among False Claims Act (FCA) claims and reviews by Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs).

More claims are being seen related to incorrect unit billings for medications, multiple procedures erroneously coded together, and incorrect usage of modifiers, she said. Also, auditors and investigators are quick to scrutinize cases in which physicians fail to clearly link the patient’s presentation to the diagnosis and treatment provided.

"The overarching criteria for all services is medical necessity," Ms. Greene said. "Medicare says it’s the physician’s responsibility to substantiate that treatment was medically necessary. If they don’t write it down, if they don’t connect the dots, then medical necessity could be called into question."

A critical element in avoiding government scrutiny is maintaining a solid compliance plan, said Mr. Kopson. The plan should include regular self-auditing and the comparing of a random sampling of charts to submitted claims.

"If you don’t have the time or expertise in-house to do that, contract with an outside consultant," Mr. Kopson said. "That will be money very well spent."

He also advised ensuring that billers and coders are appropriately trained and have sufficient skill and experience to bill accurately.

Once a payment error is identified, the claim must be refunded within 60 days and the claim must be self-reported if any fraud is involved, said Christopher A. Melton, a health law attorney and partner at Wyatt, Tarrant & Combsin Louisville, Ky. But Mr. Melton notes that federal rules lack clarity on the scope of identification. For example, if 10 claims are examined and the same error is found in all of them, it’s unclear if that sample accounts for the identification of all similar claims submitted, he said.

"The problem is, no one can audit 100% of their charts," said Mr. Melton, who was copresenter of the AHLA session. "Is there a duty to look deeper into these? Those are the questions everyone is going to have to wrestle with."

Nearly as important as preventing billing mistakes is handling audits and billing investigations correctly when they happen. While such examinations can be nerve-wracking, remember to stay calm and refrain from changing or trying to improve records, Mr. Kopson said.

"Do not change any medical records, period," he said. "That is the surest way to lose your audit or civil case and [create] significant risk of incurring criminal liability or licensure sanctions. I’ve seen far too many people get the notice, go into panic mode, and start rewriting history."

If it’s necessary to augment a chart, follow the proper rules for making amendments and additions to notes.

When physicians disagree with the findings of a RAC audit, they should document the dispute and their concerns, even if they chose to repay the claim, Mr. Melton said. This helps strengthen a doctor’s case should there later be an FCA or fraud accusation.

The aid of an experienced health law attorney can allow one to work competently through audits and address overbilling allegations, Ms. Greene added.

"Just like health care, this is a very complex industry," she said. "It’s helpful to have an attorney involved. Sometimes attorneys can have conversations with government attorneys and ask questions physicians may not be able to ask. They have a toolbox that is set up to deal with these kinds of situations."

Mr. Kopson stresses that physicians must accept that "the buck stops" with them when it comes to proper billing and coding.

"It’s no defense that your clerk entered inaccurate information or someone else who was employed by your employer did the coding," he said. "It’s critically important that you know what they are billing for your service. You could wind up in the hot seat very easily. Know the required elements for your most frequently billed codes ... and ensure that you’re documenting accurately all of those elements that you’re performing."

AAP moves toward collaboration with retail-based clinics

Pediatricians say a revised policy by the American Academy of Pediatrics that emphasizes collaboration between physicians and retail-based clinics is a necessary shift as the clinics expand and grow in popularity.

The 2014 policy maintains its stance established in 2006 that retail-based clinics (RBCs) are an inappropriate source of primary care for children, but now maintains that partnerships among pediatric medical homes and retail clinics are essential if such clinics are needed to expand acute care access in a given community.

"It is important to still emphasize that the best care for children is delivered within the medical home," Dr. Lee Savio Beers of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, said in an interview. "That said, there are situations and communities where RBCs can play a role in making sure children have access to care, particularly during after-hours times. In these situations, good collaboration between the RBCs and the primary care medical home is of the utmost importance in order to ensure the best and most comprehensive care for children."

The revised policy is a fundamental change from the AAP’s 2006 position of opposing all RBCs as a source of pediatric care. The new policy stresses that both the medical home and the RBC should develop a formal collaborative relationship in the event that pediatricians and the pediatric medical home need to use the services of an RBC. The policy indicates the necessary criteria of that relationship, including prompt communication with the pediatric medical home for all RBC visits, referral of patients back to the pediatric medical home or the establishment of a medical home, and formal arrangements for after-hours coverage or emergency situations that may occur during an RBC patient visit (Pediatrics 2014;133:e794-7 [doi 10.1542/peds.2013-4080]).

In a statement, the academy said RBCs do not provide children with the high-quality, regular preventative health care that they require, but that it is understood that the services of these clinics may be used for acute care outside the medical home. More than 6,000 RBCs have opened since their 2000 inception, and research shows 15% of pediatric patients will visit a retail clinic in the future.

"The landscape of how medical care is delivered and the continued emergence of large systems of care potentially creates an opportunity for RBCs to work with local pediatricians and utilize them as the partner to expand access to care for children and still function in a coordinated and cooperative way," said Dr. James J. Laughlin, lead author of the revised AAP policy and a Bloomington, Ind.–based pediatrician.

This policy does not cover freestanding urgent care clinics, which are addressed in a separate AAP policy statement.

Pediatricians say they are open to the idea of developing partnerships with RBCs, although some have not yet had the opportunity.

"In our area, we have not yet had to forge those relationships," said Dr. David Hill, vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "However, if we do see an influx of RBCs, we’re going to want to reach out to them proactively and ensure rapid and complete communications between their offices and ours."

Dr. Beers also has not seen a need to develop relationships with RBCs, but said the partnerships appear to be valuable in rural areas.

"We advise our patients to always call us first so that we can help them think through if they need to be seen outside the medical home and help facilitate access to care in our own clinics if needed," said Dr. Beers, chair of the AAP Committee on Residency Scholarships.

The AAP policy encourages pediatricians to offer accessible hours and locations to provide patients the convenience they prefer.

Dr. Hill’s practice already has instituted these benefits to compete with urgent care centers and emergency departments, he said.

"This year has started out for us with low patient volume, and we are responding by adding evening hours and starting to schedule well-child exams on Saturdays," said Dr. Hill, chair-elect of the AAP Council on Communications and Media.

"We’ve also added walk-in hours in the mornings and opened a new clinic. In the past, we’ve always been able to rely on providing a higher quality level of care than RBCs. Now we’re going to have to compete with them on convenience as well."

But Dr. Hill notes that RBCs as pediatric care providers are an inevitable part of the future.

"Change is a constant in pediatrics, just as in all other fields," he said. "We can shake our fists at the heavens, or we can work hard to adapt and thrive in the new environment."

Lucas Franki contributed to this report.

Pediatricians say a revised policy by the American Academy of Pediatrics that emphasizes collaboration between physicians and retail-based clinics is a necessary shift as the clinics expand and grow in popularity.

The 2014 policy maintains its stance established in 2006 that retail-based clinics (RBCs) are an inappropriate source of primary care for children, but now maintains that partnerships among pediatric medical homes and retail clinics are essential if such clinics are needed to expand acute care access in a given community.

"It is important to still emphasize that the best care for children is delivered within the medical home," Dr. Lee Savio Beers of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, said in an interview. "That said, there are situations and communities where RBCs can play a role in making sure children have access to care, particularly during after-hours times. In these situations, good collaboration between the RBCs and the primary care medical home is of the utmost importance in order to ensure the best and most comprehensive care for children."

The revised policy is a fundamental change from the AAP’s 2006 position of opposing all RBCs as a source of pediatric care. The new policy stresses that both the medical home and the RBC should develop a formal collaborative relationship in the event that pediatricians and the pediatric medical home need to use the services of an RBC. The policy indicates the necessary criteria of that relationship, including prompt communication with the pediatric medical home for all RBC visits, referral of patients back to the pediatric medical home or the establishment of a medical home, and formal arrangements for after-hours coverage or emergency situations that may occur during an RBC patient visit (Pediatrics 2014;133:e794-7 [doi 10.1542/peds.2013-4080]).

In a statement, the academy said RBCs do not provide children with the high-quality, regular preventative health care that they require, but that it is understood that the services of these clinics may be used for acute care outside the medical home. More than 6,000 RBCs have opened since their 2000 inception, and research shows 15% of pediatric patients will visit a retail clinic in the future.

"The landscape of how medical care is delivered and the continued emergence of large systems of care potentially creates an opportunity for RBCs to work with local pediatricians and utilize them as the partner to expand access to care for children and still function in a coordinated and cooperative way," said Dr. James J. Laughlin, lead author of the revised AAP policy and a Bloomington, Ind.–based pediatrician.

This policy does not cover freestanding urgent care clinics, which are addressed in a separate AAP policy statement.

Pediatricians say they are open to the idea of developing partnerships with RBCs, although some have not yet had the opportunity.

"In our area, we have not yet had to forge those relationships," said Dr. David Hill, vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "However, if we do see an influx of RBCs, we’re going to want to reach out to them proactively and ensure rapid and complete communications between their offices and ours."

Dr. Beers also has not seen a need to develop relationships with RBCs, but said the partnerships appear to be valuable in rural areas.

"We advise our patients to always call us first so that we can help them think through if they need to be seen outside the medical home and help facilitate access to care in our own clinics if needed," said Dr. Beers, chair of the AAP Committee on Residency Scholarships.

The AAP policy encourages pediatricians to offer accessible hours and locations to provide patients the convenience they prefer.

Dr. Hill’s practice already has instituted these benefits to compete with urgent care centers and emergency departments, he said.

"This year has started out for us with low patient volume, and we are responding by adding evening hours and starting to schedule well-child exams on Saturdays," said Dr. Hill, chair-elect of the AAP Council on Communications and Media.

"We’ve also added walk-in hours in the mornings and opened a new clinic. In the past, we’ve always been able to rely on providing a higher quality level of care than RBCs. Now we’re going to have to compete with them on convenience as well."

But Dr. Hill notes that RBCs as pediatric care providers are an inevitable part of the future.

"Change is a constant in pediatrics, just as in all other fields," he said. "We can shake our fists at the heavens, or we can work hard to adapt and thrive in the new environment."

Lucas Franki contributed to this report.

Pediatricians say a revised policy by the American Academy of Pediatrics that emphasizes collaboration between physicians and retail-based clinics is a necessary shift as the clinics expand and grow in popularity.

The 2014 policy maintains its stance established in 2006 that retail-based clinics (RBCs) are an inappropriate source of primary care for children, but now maintains that partnerships among pediatric medical homes and retail clinics are essential if such clinics are needed to expand acute care access in a given community.

"It is important to still emphasize that the best care for children is delivered within the medical home," Dr. Lee Savio Beers of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, said in an interview. "That said, there are situations and communities where RBCs can play a role in making sure children have access to care, particularly during after-hours times. In these situations, good collaboration between the RBCs and the primary care medical home is of the utmost importance in order to ensure the best and most comprehensive care for children."

The revised policy is a fundamental change from the AAP’s 2006 position of opposing all RBCs as a source of pediatric care. The new policy stresses that both the medical home and the RBC should develop a formal collaborative relationship in the event that pediatricians and the pediatric medical home need to use the services of an RBC. The policy indicates the necessary criteria of that relationship, including prompt communication with the pediatric medical home for all RBC visits, referral of patients back to the pediatric medical home or the establishment of a medical home, and formal arrangements for after-hours coverage or emergency situations that may occur during an RBC patient visit (Pediatrics 2014;133:e794-7 [doi 10.1542/peds.2013-4080]).

In a statement, the academy said RBCs do not provide children with the high-quality, regular preventative health care that they require, but that it is understood that the services of these clinics may be used for acute care outside the medical home. More than 6,000 RBCs have opened since their 2000 inception, and research shows 15% of pediatric patients will visit a retail clinic in the future.

"The landscape of how medical care is delivered and the continued emergence of large systems of care potentially creates an opportunity for RBCs to work with local pediatricians and utilize them as the partner to expand access to care for children and still function in a coordinated and cooperative way," said Dr. James J. Laughlin, lead author of the revised AAP policy and a Bloomington, Ind.–based pediatrician.

This policy does not cover freestanding urgent care clinics, which are addressed in a separate AAP policy statement.

Pediatricians say they are open to the idea of developing partnerships with RBCs, although some have not yet had the opportunity.

"In our area, we have not yet had to forge those relationships," said Dr. David Hill, vice president of Cape Fear Pediatrics in Wilmington, N.C., and professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "However, if we do see an influx of RBCs, we’re going to want to reach out to them proactively and ensure rapid and complete communications between their offices and ours."

Dr. Beers also has not seen a need to develop relationships with RBCs, but said the partnerships appear to be valuable in rural areas.

"We advise our patients to always call us first so that we can help them think through if they need to be seen outside the medical home and help facilitate access to care in our own clinics if needed," said Dr. Beers, chair of the AAP Committee on Residency Scholarships.

The AAP policy encourages pediatricians to offer accessible hours and locations to provide patients the convenience they prefer.

Dr. Hill’s practice already has instituted these benefits to compete with urgent care centers and emergency departments, he said.

"This year has started out for us with low patient volume, and we are responding by adding evening hours and starting to schedule well-child exams on Saturdays," said Dr. Hill, chair-elect of the AAP Council on Communications and Media.

"We’ve also added walk-in hours in the mornings and opened a new clinic. In the past, we’ve always been able to rely on providing a higher quality level of care than RBCs. Now we’re going to have to compete with them on convenience as well."

But Dr. Hill notes that RBCs as pediatric care providers are an inevitable part of the future.

"Change is a constant in pediatrics, just as in all other fields," he said. "We can shake our fists at the heavens, or we can work hard to adapt and thrive in the new environment."

Lucas Franki contributed to this report.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Birth injury funds may end lawsuit strife for ob.gyns.

Physicians in Maryland are pushing for legislation that would create a fund to compensate infants injured at birth, in an attempt to combat multimillion-dollar jury verdicts and excessive liability premiums for ob.gyns. in that state. If passed, Maryland would follow in the footsteps of three other states that have birth injury funds: New York, Florida, and Virginia.

"Physicians who have been sued know how devastating that can be," said Dr. Dan K. Morhaim (D-Baltimore County), a Maryland state delegate who sponsored the bill. The birth injury fund "would avoid lawsuits where the problem could be solved another way. The current system is based on litigation. It’s like a big-time lottery. Some [plaintiffs] get huge settlements, others get nothing."

The proposed Maryland bill would require physicians who deliver at least five infants yearly to pay $7,500 into the fund annually, while hospitals would pay about $175 per birth, depending on hospital size. Insurers also would pay a surcharge. Families would have to show proof of an infant’s injury when applying to the fund, and an administrative law judge would determine eligibility. The bill is currently in the Maryland House of Delegates and at press time a hearing was scheduled.

Questions remain, however, about how effective birth injury funds are for physicians and whether they work to reduce litigation costs. Medical experts in Virginia and Florida cite significant reductions in medical liability premiums for doctors and markedly lower claim frequency since enactment of their respective funds. New York physicians, however, have so far not seen the results they had hoped from the fund, said Liz Dears, senior vice president for legislative and regulatory affairs for the Medical Society of the State of New York.

In New York, physicians "have not been able to attribute any reductions in medical liability premiums to the existence of the [fund]," Ms. Dears said. "For physicians, it’s been very disappointing. It hasn’t translated into what our overall goal has been, which is overall cost reductions."

New York enacted its medial indemnity fund in 2011. The system is designed to pay future medical costs of malpractice plaintiffs who receive court-approved settlements or judgments for birth-related injuries. The medical indemnity fund is funded by assessing all hospitals performing obstetrical services an amount equal to 1.6% percent of their obstetrics revenue. Doctors do not pay into the fund, Ms. Dears said. Thus far, the 3-year-old program has resulted in lower medical liability premiums for some hospitals – but not doctors, she said.

In Virginia, ob.gyns. and other physicians report an opposite experience. The state’s birth injury fund was created in 1987 to mitigate a growing lack of insurance coverage for ob.gyns., said Michael Jurgensen, senior vice president of health policy for the Medical Society of Virginia. Participating physicians pay $5,000 a year into the fund, while nonparticipating doctors pay $250 a year. Participating hospitals also pay an assessment.