User login

Senate votes on 20-week abortion ban

The U.S. Senate blocked a proposed national ban on abortions after 20 weeks gestation following a closely divided 51-46 vote on Jan. 29.

The Pain-Capable Unborn Children Protection Act, which passed the House last year after a 237-189 vote, did not earn the 60 votes it needed to clear the Senate, marking a defeat for anti-abortion proponents such as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.).

In a Jan. 29 statement, Sen. McConnell said the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act reflects a growing consensus that unborn children should not be subjected to elective abortion after 20 weeks.

After the vote, President Trump said in a statement that it was “disappointing that despite support from a bipartisan majority of U.S. Senators, this bill was blocked from further consideration.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) denounced the legislation in a Jan. 26 statement, calling it an attack on women’s access to comprehensive health care, including abortion care.

The vote was primarily split along party lines. Only three Democrats voted for the bill – Sens. Robert P. Casey Jr. of Pennsylvania, Joe Donnelly of Indiana, and Joe Manchin III of West Virginia. The three are all up for reelection this year in states in which Trump won in 2016.

The U.S. Senate blocked a proposed national ban on abortions after 20 weeks gestation following a closely divided 51-46 vote on Jan. 29.

The Pain-Capable Unborn Children Protection Act, which passed the House last year after a 237-189 vote, did not earn the 60 votes it needed to clear the Senate, marking a defeat for anti-abortion proponents such as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.).

In a Jan. 29 statement, Sen. McConnell said the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act reflects a growing consensus that unborn children should not be subjected to elective abortion after 20 weeks.

After the vote, President Trump said in a statement that it was “disappointing that despite support from a bipartisan majority of U.S. Senators, this bill was blocked from further consideration.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) denounced the legislation in a Jan. 26 statement, calling it an attack on women’s access to comprehensive health care, including abortion care.

The vote was primarily split along party lines. Only three Democrats voted for the bill – Sens. Robert P. Casey Jr. of Pennsylvania, Joe Donnelly of Indiana, and Joe Manchin III of West Virginia. The three are all up for reelection this year in states in which Trump won in 2016.

The U.S. Senate blocked a proposed national ban on abortions after 20 weeks gestation following a closely divided 51-46 vote on Jan. 29.

The Pain-Capable Unborn Children Protection Act, which passed the House last year after a 237-189 vote, did not earn the 60 votes it needed to clear the Senate, marking a defeat for anti-abortion proponents such as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.).

In a Jan. 29 statement, Sen. McConnell said the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act reflects a growing consensus that unborn children should not be subjected to elective abortion after 20 weeks.

After the vote, President Trump said in a statement that it was “disappointing that despite support from a bipartisan majority of U.S. Senators, this bill was blocked from further consideration.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) denounced the legislation in a Jan. 26 statement, calling it an attack on women’s access to comprehensive health care, including abortion care.

The vote was primarily split along party lines. Only three Democrats voted for the bill – Sens. Robert P. Casey Jr. of Pennsylvania, Joe Donnelly of Indiana, and Joe Manchin III of West Virginia. The three are all up for reelection this year in states in which Trump won in 2016.

STUDY: More mammograms after cost-sharing elimination

More women received recommended mammograms after cost sharing for the service was eliminated under the Affordable Care Act, a study shows.

In health plans that eliminated cost sharing, such as copays, deductibles, or other out-of-pocket costs, the rate of biennial screening mammography increased from 60% in the 2-year period before the cost-sharing elimination to 65% in the 2-year period following the new regulation, according to an analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition to the increased rate of mammograms in the first group, results showed the rates of biennial mammography in the second group were 73.1% (95% confidence interval, 69.2-77.0) and 72.8% (95% CI, 69.7-76.0) during the same periods, yielding a difference in differences of 5.7 percentage points. Investigators also found the difference in differences was 9.8 percentage points among women living in areas with the highest quartile of educational attainment, compared with 4.3 percentage points among women in the lowest quartile. After the elimination of cost sharing, the rate of biennial mammography rose by 6.5 percentage points for white women and 8.4 percentage points for black women, the study found. The rate was nearly unchanged for Hispanic women.

The findings extend that of past studies that show older women who need mammograms are sensitive to out-of-pocket costs and the presence of supplemental coverage, the authors conclude. If the cost-sharing provisions of the ACA are rescinded, the results also “raise concern that fewer older women will receive recommended breast-cancer screening.”

However, the authors also note that since mammogram rates in the health plans that eliminated cost sharing remained below those in plans with full coverage and less than three-quarters of women in control plans received biennial breast cancer screenings, that “the removal of out-of-pocket payments alone may not raise screening rates to desired levels.”

SOURCE: Trivedi A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 18;378:262-9.

More women received recommended mammograms after cost sharing for the service was eliminated under the Affordable Care Act, a study shows.

In health plans that eliminated cost sharing, such as copays, deductibles, or other out-of-pocket costs, the rate of biennial screening mammography increased from 60% in the 2-year period before the cost-sharing elimination to 65% in the 2-year period following the new regulation, according to an analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition to the increased rate of mammograms in the first group, results showed the rates of biennial mammography in the second group were 73.1% (95% confidence interval, 69.2-77.0) and 72.8% (95% CI, 69.7-76.0) during the same periods, yielding a difference in differences of 5.7 percentage points. Investigators also found the difference in differences was 9.8 percentage points among women living in areas with the highest quartile of educational attainment, compared with 4.3 percentage points among women in the lowest quartile. After the elimination of cost sharing, the rate of biennial mammography rose by 6.5 percentage points for white women and 8.4 percentage points for black women, the study found. The rate was nearly unchanged for Hispanic women.

The findings extend that of past studies that show older women who need mammograms are sensitive to out-of-pocket costs and the presence of supplemental coverage, the authors conclude. If the cost-sharing provisions of the ACA are rescinded, the results also “raise concern that fewer older women will receive recommended breast-cancer screening.”

However, the authors also note that since mammogram rates in the health plans that eliminated cost sharing remained below those in plans with full coverage and less than three-quarters of women in control plans received biennial breast cancer screenings, that “the removal of out-of-pocket payments alone may not raise screening rates to desired levels.”

SOURCE: Trivedi A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 18;378:262-9.

More women received recommended mammograms after cost sharing for the service was eliminated under the Affordable Care Act, a study shows.

In health plans that eliminated cost sharing, such as copays, deductibles, or other out-of-pocket costs, the rate of biennial screening mammography increased from 60% in the 2-year period before the cost-sharing elimination to 65% in the 2-year period following the new regulation, according to an analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition to the increased rate of mammograms in the first group, results showed the rates of biennial mammography in the second group were 73.1% (95% confidence interval, 69.2-77.0) and 72.8% (95% CI, 69.7-76.0) during the same periods, yielding a difference in differences of 5.7 percentage points. Investigators also found the difference in differences was 9.8 percentage points among women living in areas with the highest quartile of educational attainment, compared with 4.3 percentage points among women in the lowest quartile. After the elimination of cost sharing, the rate of biennial mammography rose by 6.5 percentage points for white women and 8.4 percentage points for black women, the study found. The rate was nearly unchanged for Hispanic women.

The findings extend that of past studies that show older women who need mammograms are sensitive to out-of-pocket costs and the presence of supplemental coverage, the authors conclude. If the cost-sharing provisions of the ACA are rescinded, the results also “raise concern that fewer older women will receive recommended breast-cancer screening.”

However, the authors also note that since mammogram rates in the health plans that eliminated cost sharing remained below those in plans with full coverage and less than three-quarters of women in control plans received biennial breast cancer screenings, that “the removal of out-of-pocket payments alone may not raise screening rates to desired levels.”

SOURCE: Trivedi A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 18;378:262-9.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In plans that eliminated cost sharing, the rate of biennial screening mammography increased from 60% to 65% in the 2-year period thereafter.

Study details: A difference-in-differences study of biennial screening mammography among 15,085 women aged 65-74 years in 24 Medicare Advantage plans.

Disclosures: Dr. Trivedi reported personal fees from Merck Foundation outside the submitted work. Authors reported no other disclosures.

Source: Trivedi A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 18;378:262-9.

HHS creates new religious freedoms division

The Trump administration has announced a new division within the U.S. Health & Human Services Department that aims to protect health care providers who have religious or moral objections to performing medical services, such as abortion.

In a Jan. 18 announcement, HHS Office for Civil Rights Director Roger Severino said the new Conscience and Religious Freedom Division will focus on outreach, policy making, and vigorously enforcing existing federal laws that protect conscience and religious freedom rights. The new branch will enable health providers to file conscience and religious freedom complaints, which will then be investigated by the division.

Opinions on the new division from physicians and medical associations were mixed. The American College of Physicians (ACP) cautioned that the division’s creation must not lead to discrimination against any category of class of patients, as guided by medical professions’ ethical obligations.

“ACP would be particularly concerned if the new HHS division takes any actions that would result in denial of access to appropriate health care based on gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, or other personal characteristics,” ACP President Jack Ende, MD, said in a statement. “ACP will evaluate the newly formed division as it begins operating, informed by our ethics and public policy positions. Those state that physicians have a professional obligation to not discriminate against any class of patients, but also that a physician may have a conscientious objection to providing a specific medical service to a patient.”

The Catholic Medical Association (CMA) applauded the new HHS division, saying it’s about time that the religious and conscience rights of health providers were protected by the federal government. In the past, health providers could be drawn into medical activities in a hospital or health care system that they found moral objectionable with no recourse, said Kathleen Raviele, MD, a board member for the Catholic Medical Association and a Decatur, Ga.–based ob.gyn.

“The fact that individual health care providers are going to have a place to go if they feel they have valid complaint is really momentous,” Dr. Raviele said in an interview. “It’s respecting the rights of all of us and not just some special interest groups ... I also think [the new division] will make states [and] hospital systems less likely to try to infringe on people’s conscientious rights.”

The HIV Medicine Association called the formation of the new HHS division appalling, and said the office appears to protect health care providers who discriminate against vulnerable patients, such as women, LGBTQ patients, and minorities.

“The new division, designed to ‘protect’ health care providers who discriminate in the care and services they provide, defies the fundamental medical ethic to first do no harm,” HIV Medicine Association Chair Melanie Thompson, MD, said in a statement. “Using federal dollars to shield providers who choose to discriminate rather than protect vulnerable patients and provide services to improve their health is counter to the mission of HHS, wasteful of scarce federal funds, and will result in delayed or lack of care for vulnerable individuals, threatening their health and lives.”

The HHS Conscience and Religious Freedom Division is necessary to address the “sustained attack on conscience rights,” said Jane Orient, MD, executive director for the conservative Association of American Physicians and Surgeons.

“Many powerful and influential forces are attempting to impose their views on Americans, predominantly on Christians, forcing them to perform acts they believe to be immoral, [or risk] losing their job, their business, their livelihood, or even their life savings,” Dr. Orient said in an interview. “...We hope that the OCR will help to return our nation to its foundational principles of freedom and respect for people of conscience.”

The Trump administration has announced a new division within the U.S. Health & Human Services Department that aims to protect health care providers who have religious or moral objections to performing medical services, such as abortion.

In a Jan. 18 announcement, HHS Office for Civil Rights Director Roger Severino said the new Conscience and Religious Freedom Division will focus on outreach, policy making, and vigorously enforcing existing federal laws that protect conscience and religious freedom rights. The new branch will enable health providers to file conscience and religious freedom complaints, which will then be investigated by the division.

Opinions on the new division from physicians and medical associations were mixed. The American College of Physicians (ACP) cautioned that the division’s creation must not lead to discrimination against any category of class of patients, as guided by medical professions’ ethical obligations.

“ACP would be particularly concerned if the new HHS division takes any actions that would result in denial of access to appropriate health care based on gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, or other personal characteristics,” ACP President Jack Ende, MD, said in a statement. “ACP will evaluate the newly formed division as it begins operating, informed by our ethics and public policy positions. Those state that physicians have a professional obligation to not discriminate against any class of patients, but also that a physician may have a conscientious objection to providing a specific medical service to a patient.”

The Catholic Medical Association (CMA) applauded the new HHS division, saying it’s about time that the religious and conscience rights of health providers were protected by the federal government. In the past, health providers could be drawn into medical activities in a hospital or health care system that they found moral objectionable with no recourse, said Kathleen Raviele, MD, a board member for the Catholic Medical Association and a Decatur, Ga.–based ob.gyn.

“The fact that individual health care providers are going to have a place to go if they feel they have valid complaint is really momentous,” Dr. Raviele said in an interview. “It’s respecting the rights of all of us and not just some special interest groups ... I also think [the new division] will make states [and] hospital systems less likely to try to infringe on people’s conscientious rights.”

The HIV Medicine Association called the formation of the new HHS division appalling, and said the office appears to protect health care providers who discriminate against vulnerable patients, such as women, LGBTQ patients, and minorities.

“The new division, designed to ‘protect’ health care providers who discriminate in the care and services they provide, defies the fundamental medical ethic to first do no harm,” HIV Medicine Association Chair Melanie Thompson, MD, said in a statement. “Using federal dollars to shield providers who choose to discriminate rather than protect vulnerable patients and provide services to improve their health is counter to the mission of HHS, wasteful of scarce federal funds, and will result in delayed or lack of care for vulnerable individuals, threatening their health and lives.”

The HHS Conscience and Religious Freedom Division is necessary to address the “sustained attack on conscience rights,” said Jane Orient, MD, executive director for the conservative Association of American Physicians and Surgeons.

“Many powerful and influential forces are attempting to impose their views on Americans, predominantly on Christians, forcing them to perform acts they believe to be immoral, [or risk] losing their job, their business, their livelihood, or even their life savings,” Dr. Orient said in an interview. “...We hope that the OCR will help to return our nation to its foundational principles of freedom and respect for people of conscience.”

The Trump administration has announced a new division within the U.S. Health & Human Services Department that aims to protect health care providers who have religious or moral objections to performing medical services, such as abortion.

In a Jan. 18 announcement, HHS Office for Civil Rights Director Roger Severino said the new Conscience and Religious Freedom Division will focus on outreach, policy making, and vigorously enforcing existing federal laws that protect conscience and religious freedom rights. The new branch will enable health providers to file conscience and religious freedom complaints, which will then be investigated by the division.

Opinions on the new division from physicians and medical associations were mixed. The American College of Physicians (ACP) cautioned that the division’s creation must not lead to discrimination against any category of class of patients, as guided by medical professions’ ethical obligations.

“ACP would be particularly concerned if the new HHS division takes any actions that would result in denial of access to appropriate health care based on gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, or other personal characteristics,” ACP President Jack Ende, MD, said in a statement. “ACP will evaluate the newly formed division as it begins operating, informed by our ethics and public policy positions. Those state that physicians have a professional obligation to not discriminate against any class of patients, but also that a physician may have a conscientious objection to providing a specific medical service to a patient.”

The Catholic Medical Association (CMA) applauded the new HHS division, saying it’s about time that the religious and conscience rights of health providers were protected by the federal government. In the past, health providers could be drawn into medical activities in a hospital or health care system that they found moral objectionable with no recourse, said Kathleen Raviele, MD, a board member for the Catholic Medical Association and a Decatur, Ga.–based ob.gyn.

“The fact that individual health care providers are going to have a place to go if they feel they have valid complaint is really momentous,” Dr. Raviele said in an interview. “It’s respecting the rights of all of us and not just some special interest groups ... I also think [the new division] will make states [and] hospital systems less likely to try to infringe on people’s conscientious rights.”

The HIV Medicine Association called the formation of the new HHS division appalling, and said the office appears to protect health care providers who discriminate against vulnerable patients, such as women, LGBTQ patients, and minorities.

“The new division, designed to ‘protect’ health care providers who discriminate in the care and services they provide, defies the fundamental medical ethic to first do no harm,” HIV Medicine Association Chair Melanie Thompson, MD, said in a statement. “Using federal dollars to shield providers who choose to discriminate rather than protect vulnerable patients and provide services to improve their health is counter to the mission of HHS, wasteful of scarce federal funds, and will result in delayed or lack of care for vulnerable individuals, threatening their health and lives.”

The HHS Conscience and Religious Freedom Division is necessary to address the “sustained attack on conscience rights,” said Jane Orient, MD, executive director for the conservative Association of American Physicians and Surgeons.

“Many powerful and influential forces are attempting to impose their views on Americans, predominantly on Christians, forcing them to perform acts they believe to be immoral, [or risk] losing their job, their business, their livelihood, or even their life savings,” Dr. Orient said in an interview. “...We hope that the OCR will help to return our nation to its foundational principles of freedom and respect for people of conscience.”

Malpractice premiums dip again

Malpractice premiums continue to inch down but wide disparities in total cost still linger across states.

Internists, general surgeons, and obstetrician-gynecologists experienced a respective 1% drop in their medical liability premiums last year, according to the 2017 Medical Liability Monitor Annual Rate Survey. The rate drop follows an ongoing trend of decreasing premiums over the last decade.

“The takeaways for doctors are really all good ones in that the rates remain very stable,” said Paul A. Greve Jr. senior vice president/senior consultant for Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice and coauthor of the 2017 MLM Survey report. “The market for physician coverage remains very competitive because there are so many players involved for what is really a shrinking number of buyers, so the groups and individual physicians that are buying are seeing favorable pricing.”

Premiums differed vastly across geographic area, consistent with previous years. Southern Florida internists for example, paid $47,707 for malpractice insurance last year, while their Minnesota colleagues paid $3,375. For ob.gyns., premiums ranged from $214,999 in southern New York to $16,240 in central California. General surgeons in Southern Florida paid $190,829 in 2016, while those in Wisconsin paid $10,868.

Overall, no states experienced a premium rate change in the double digits, and physicians in only five states – Hawaii, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, and Ohio – saw premium decreases of more than 5%. No states experienced rate increases of more than 5%.

Fewer claims filed by plaintiffs’ attorneys is one factor contributing to the continued stability of malpractice premiums, according to analysts. However, there are signs that high verdicts are on the rise, said Michael Matray, editor of the Medical Liability Monitor and chief content officer for Cunningham Group. Survey data show claims closing at greater than $1 million are increasing.

“There is data that indicates claim severity has experienced a slight uptick,” Mr. Matray said in an interview. “It obviously hasn’t affected rates, yet. This could be due to the positive effect state-level tort reforms have had – where plaintiff attorneys are only bringing cases that are a slam dunk and carry a larger dollar value.”

Continued practice consolidation and the increase in employed physicians also helped keep premiums steady, Mr. Greve said in an interview. Consolidation means fewer buyers and a more competitive market, which helps keep premiums low and stable.

The jury is still out on how the move to value-based care might impact medical malpractice insurance payments. There is concern that the methods required to determine health care value could unwittingly increase malpractice risk, Mr. Matray said.

“To support value-based reimbursement models, a health care system must manage a vast network of public and private data used by various entities in order to monitor quality and cost,” Mr. Matray said. “The collection of that data requires using electronic health record technology that many physicians find onerous. This leads to physician burnout and dangerous EHR workarounds, such as copy-and-paste practices where previous EHR entries are cloned and inserted into a new progress note, as well as disabling or overriding burdensome safety alerts, to save time and increase efficiency. You can see how this would increase medical liability claim risk.”

The MLM survey is published yearly based on July 1 premium data from the major malpractice insurers and examines premium rates for mature, claims-made policies with $1 million/$3 million limits for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns.

Malpractice premiums continue to inch down but wide disparities in total cost still linger across states.

Internists, general surgeons, and obstetrician-gynecologists experienced a respective 1% drop in their medical liability premiums last year, according to the 2017 Medical Liability Monitor Annual Rate Survey. The rate drop follows an ongoing trend of decreasing premiums over the last decade.

“The takeaways for doctors are really all good ones in that the rates remain very stable,” said Paul A. Greve Jr. senior vice president/senior consultant for Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice and coauthor of the 2017 MLM Survey report. “The market for physician coverage remains very competitive because there are so many players involved for what is really a shrinking number of buyers, so the groups and individual physicians that are buying are seeing favorable pricing.”

Premiums differed vastly across geographic area, consistent with previous years. Southern Florida internists for example, paid $47,707 for malpractice insurance last year, while their Minnesota colleagues paid $3,375. For ob.gyns., premiums ranged from $214,999 in southern New York to $16,240 in central California. General surgeons in Southern Florida paid $190,829 in 2016, while those in Wisconsin paid $10,868.

Overall, no states experienced a premium rate change in the double digits, and physicians in only five states – Hawaii, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, and Ohio – saw premium decreases of more than 5%. No states experienced rate increases of more than 5%.

Fewer claims filed by plaintiffs’ attorneys is one factor contributing to the continued stability of malpractice premiums, according to analysts. However, there are signs that high verdicts are on the rise, said Michael Matray, editor of the Medical Liability Monitor and chief content officer for Cunningham Group. Survey data show claims closing at greater than $1 million are increasing.

“There is data that indicates claim severity has experienced a slight uptick,” Mr. Matray said in an interview. “It obviously hasn’t affected rates, yet. This could be due to the positive effect state-level tort reforms have had – where plaintiff attorneys are only bringing cases that are a slam dunk and carry a larger dollar value.”

Continued practice consolidation and the increase in employed physicians also helped keep premiums steady, Mr. Greve said in an interview. Consolidation means fewer buyers and a more competitive market, which helps keep premiums low and stable.

The jury is still out on how the move to value-based care might impact medical malpractice insurance payments. There is concern that the methods required to determine health care value could unwittingly increase malpractice risk, Mr. Matray said.

“To support value-based reimbursement models, a health care system must manage a vast network of public and private data used by various entities in order to monitor quality and cost,” Mr. Matray said. “The collection of that data requires using electronic health record technology that many physicians find onerous. This leads to physician burnout and dangerous EHR workarounds, such as copy-and-paste practices where previous EHR entries are cloned and inserted into a new progress note, as well as disabling or overriding burdensome safety alerts, to save time and increase efficiency. You can see how this would increase medical liability claim risk.”

The MLM survey is published yearly based on July 1 premium data from the major malpractice insurers and examines premium rates for mature, claims-made policies with $1 million/$3 million limits for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns.

Malpractice premiums continue to inch down but wide disparities in total cost still linger across states.

Internists, general surgeons, and obstetrician-gynecologists experienced a respective 1% drop in their medical liability premiums last year, according to the 2017 Medical Liability Monitor Annual Rate Survey. The rate drop follows an ongoing trend of decreasing premiums over the last decade.

“The takeaways for doctors are really all good ones in that the rates remain very stable,” said Paul A. Greve Jr. senior vice president/senior consultant for Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice and coauthor of the 2017 MLM Survey report. “The market for physician coverage remains very competitive because there are so many players involved for what is really a shrinking number of buyers, so the groups and individual physicians that are buying are seeing favorable pricing.”

Premiums differed vastly across geographic area, consistent with previous years. Southern Florida internists for example, paid $47,707 for malpractice insurance last year, while their Minnesota colleagues paid $3,375. For ob.gyns., premiums ranged from $214,999 in southern New York to $16,240 in central California. General surgeons in Southern Florida paid $190,829 in 2016, while those in Wisconsin paid $10,868.

Overall, no states experienced a premium rate change in the double digits, and physicians in only five states – Hawaii, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, and Ohio – saw premium decreases of more than 5%. No states experienced rate increases of more than 5%.

Fewer claims filed by plaintiffs’ attorneys is one factor contributing to the continued stability of malpractice premiums, according to analysts. However, there are signs that high verdicts are on the rise, said Michael Matray, editor of the Medical Liability Monitor and chief content officer for Cunningham Group. Survey data show claims closing at greater than $1 million are increasing.

“There is data that indicates claim severity has experienced a slight uptick,” Mr. Matray said in an interview. “It obviously hasn’t affected rates, yet. This could be due to the positive effect state-level tort reforms have had – where plaintiff attorneys are only bringing cases that are a slam dunk and carry a larger dollar value.”

Continued practice consolidation and the increase in employed physicians also helped keep premiums steady, Mr. Greve said in an interview. Consolidation means fewer buyers and a more competitive market, which helps keep premiums low and stable.

The jury is still out on how the move to value-based care might impact medical malpractice insurance payments. There is concern that the methods required to determine health care value could unwittingly increase malpractice risk, Mr. Matray said.

“To support value-based reimbursement models, a health care system must manage a vast network of public and private data used by various entities in order to monitor quality and cost,” Mr. Matray said. “The collection of that data requires using electronic health record technology that many physicians find onerous. This leads to physician burnout and dangerous EHR workarounds, such as copy-and-paste practices where previous EHR entries are cloned and inserted into a new progress note, as well as disabling or overriding burdensome safety alerts, to save time and increase efficiency. You can see how this would increase medical liability claim risk.”

The MLM survey is published yearly based on July 1 premium data from the major malpractice insurers and examines premium rates for mature, claims-made policies with $1 million/$3 million limits for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns.

Study: EHR malpractice claims rising

Malpractice claims involving the use of electronic health records (EHRs) are on the rise, according to data from The Doctors Company.

Cases in which EHRs were a factor grew from 2 claims during 2007-2010 to 161 claims from 2011 to December 2016, according an analysis published Oct. 16 by The Doctors Company, a national medical malpractice insurer.

The majority of EHR-related claims during 2014-2016 stemmed from incidents in a doctor’s office or a hospital clinic (35%), while the second most common location was a patient’s room. Malpractice claims involving EHRs were most commonly alleged against ob.gyns, followed by family physicians, and orthopedists. Diagnosis errors and improper medication management were the top most frequent allegations associated with EHR claims.

The analysis shows that while digitization of medicine has improved patient safety, it also has a dark side – as evidenced by the emergence of new kinds of errors, said Robert M. Wachter, MD, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and a member of the board of governors for The Doctors Company.

“This study makes an important contribution by chronicling actual errors, such as wrong medications selected from an autopick list, and helps point the way to changes ranging from physician education to EHR software design,” Dr. Wachter said in a statement.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Malpractice claims involving the use of electronic health records (EHRs) are on the rise, according to data from The Doctors Company.

Cases in which EHRs were a factor grew from 2 claims during 2007-2010 to 161 claims from 2011 to December 2016, according an analysis published Oct. 16 by The Doctors Company, a national medical malpractice insurer.

The majority of EHR-related claims during 2014-2016 stemmed from incidents in a doctor’s office or a hospital clinic (35%), while the second most common location was a patient’s room. Malpractice claims involving EHRs were most commonly alleged against ob.gyns, followed by family physicians, and orthopedists. Diagnosis errors and improper medication management were the top most frequent allegations associated with EHR claims.

The analysis shows that while digitization of medicine has improved patient safety, it also has a dark side – as evidenced by the emergence of new kinds of errors, said Robert M. Wachter, MD, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and a member of the board of governors for The Doctors Company.

“This study makes an important contribution by chronicling actual errors, such as wrong medications selected from an autopick list, and helps point the way to changes ranging from physician education to EHR software design,” Dr. Wachter said in a statement.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Malpractice claims involving the use of electronic health records (EHRs) are on the rise, according to data from The Doctors Company.

Cases in which EHRs were a factor grew from 2 claims during 2007-2010 to 161 claims from 2011 to December 2016, according an analysis published Oct. 16 by The Doctors Company, a national medical malpractice insurer.

The majority of EHR-related claims during 2014-2016 stemmed from incidents in a doctor’s office or a hospital clinic (35%), while the second most common location was a patient’s room. Malpractice claims involving EHRs were most commonly alleged against ob.gyns, followed by family physicians, and orthopedists. Diagnosis errors and improper medication management were the top most frequent allegations associated with EHR claims.

The analysis shows that while digitization of medicine has improved patient safety, it also has a dark side – as evidenced by the emergence of new kinds of errors, said Robert M. Wachter, MD, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and a member of the board of governors for The Doctors Company.

“This study makes an important contribution by chronicling actual errors, such as wrong medications selected from an autopick list, and helps point the way to changes ranging from physician education to EHR software design,” Dr. Wachter said in a statement.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Cases in which EHRs were a factor grew from 2 claims during 2007-2010 to 161 claims from 2011 to December 2016

Data source: Review of 163 claims from 2007 to 2016 in The Doctors Company database.

Disclosures: The study was funded by The Doctors Company.

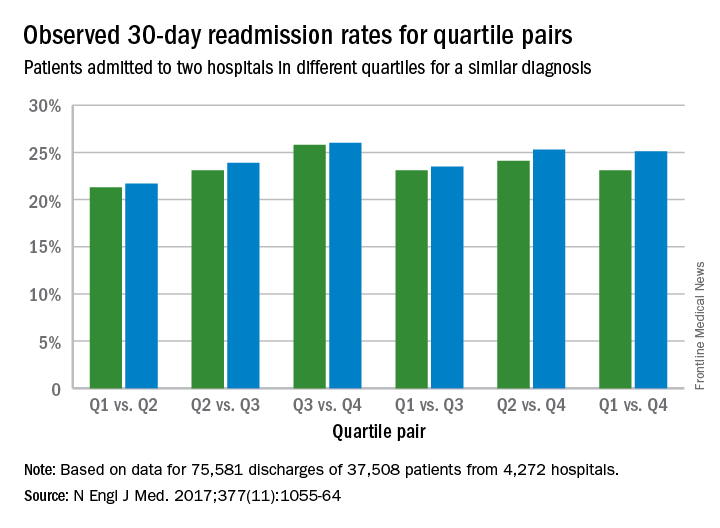

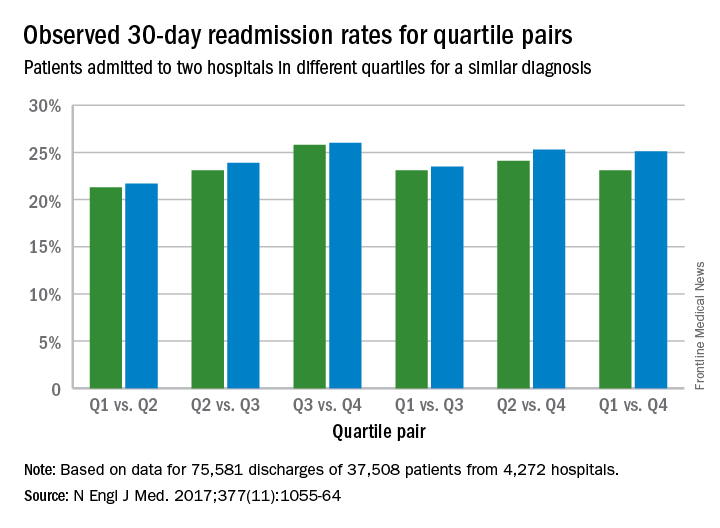

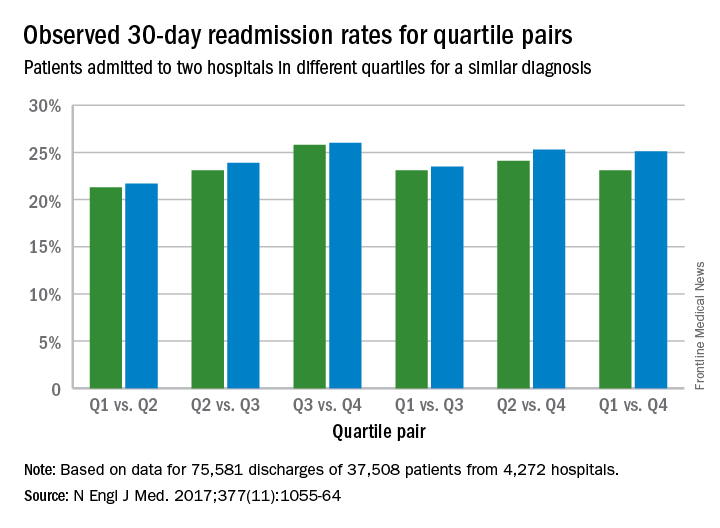

Readmission rates linked to hospital quality measures

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points).

Data source: Analysis of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data from July 2014 through June 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

Malpractice: Communication and compensation program helps to minimize lawsuits

Communication and resolution programs at four Massachusetts medical centers helped resolve adverse medical events without increasing lawsuits or leading to excessive payouts to patients, according to Michelle M. Mello, PhD, and her colleagues.

They evaluated a communication and resolution program (CRP) model known as CARe (Communication, Apology, and Resolution) implemented at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and at two of each center’s community hospitals. As part of the CARe model, hospital staff and insurers communicate with patients when adverse events occur, investigate and explain what happened, and, when appropriate, apologize and offer compensation.

Of 989 total events studied, 929 (90%) entered the program because an adverse event that allegedly exceeded the severity threshold was reported and 60 (6%) entered CARe because a prelitigation notice or claim was received, said Dr. Mello, professor of law and health research and policy at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Few events that entered the CARe process met the criteria for compensation. The standard of care was violated in 26% of cases where a determination could be reached. No determination could be reached in 59 cases, 9 cases were pending at the close of data collection, and 5 were referred directly to the insurer. Of the 241 cases involving standard-of-care violations, 55% were potentially eligible for compensation because they involved significant harm. After further review, monetary compensation was offered in 43 cases and paid in 40 cases by August 2016, with $75,000 as the median payment (Health Aff. 2017 Oct 2;36[10]:1795-1803).

As of August 2016, 5% of the 929 adverse events led to claims or lawsuits. Insurers deemed 14 of the 47 events that ultimately resulted in legal action ineligible for compensation because of a lack of negligence or lack of harm. They deemed 22 of the cases compensable, offered compensation in all of them, and had settled 20 by August 2016.

During the CARe process, patient safety improvements were frequently identified and improvements made, the investigators said. Of 132 cases in which review progressed far enough for patient safety questions to have been answered, 41% of the incidents gave rise to a safety improvement action. Actions included sharing investigation findings with clinical staff members, clinical staff educational efforts, policy changes, safety alerts sent to staff members, input into the quality improvement system for further analysis, new process flow diagrams, and human factor engineering analysis, among others.

Investigators also surveyed clinicians on their satisfaction with the CARe program. Of 162 clinicians (124 physicians), nearly 40% were either not very or not at all familiar with the program. More than two-thirds (69%) of those who felt well informed about the program gave strongly positive ratings and 10% gave a negative rating to the program. The most commonly suggested improvement to CARe was to improve communication with clinicians.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Communication and resolution programs at four Massachusetts medical centers helped resolve adverse medical events without increasing lawsuits or leading to excessive payouts to patients, according to Michelle M. Mello, PhD, and her colleagues.

They evaluated a communication and resolution program (CRP) model known as CARe (Communication, Apology, and Resolution) implemented at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and at two of each center’s community hospitals. As part of the CARe model, hospital staff and insurers communicate with patients when adverse events occur, investigate and explain what happened, and, when appropriate, apologize and offer compensation.

Of 989 total events studied, 929 (90%) entered the program because an adverse event that allegedly exceeded the severity threshold was reported and 60 (6%) entered CARe because a prelitigation notice or claim was received, said Dr. Mello, professor of law and health research and policy at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Few events that entered the CARe process met the criteria for compensation. The standard of care was violated in 26% of cases where a determination could be reached. No determination could be reached in 59 cases, 9 cases were pending at the close of data collection, and 5 were referred directly to the insurer. Of the 241 cases involving standard-of-care violations, 55% were potentially eligible for compensation because they involved significant harm. After further review, monetary compensation was offered in 43 cases and paid in 40 cases by August 2016, with $75,000 as the median payment (Health Aff. 2017 Oct 2;36[10]:1795-1803).

As of August 2016, 5% of the 929 adverse events led to claims or lawsuits. Insurers deemed 14 of the 47 events that ultimately resulted in legal action ineligible for compensation because of a lack of negligence or lack of harm. They deemed 22 of the cases compensable, offered compensation in all of them, and had settled 20 by August 2016.

During the CARe process, patient safety improvements were frequently identified and improvements made, the investigators said. Of 132 cases in which review progressed far enough for patient safety questions to have been answered, 41% of the incidents gave rise to a safety improvement action. Actions included sharing investigation findings with clinical staff members, clinical staff educational efforts, policy changes, safety alerts sent to staff members, input into the quality improvement system for further analysis, new process flow diagrams, and human factor engineering analysis, among others.

Investigators also surveyed clinicians on their satisfaction with the CARe program. Of 162 clinicians (124 physicians), nearly 40% were either not very or not at all familiar with the program. More than two-thirds (69%) of those who felt well informed about the program gave strongly positive ratings and 10% gave a negative rating to the program. The most commonly suggested improvement to CARe was to improve communication with clinicians.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Communication and resolution programs at four Massachusetts medical centers helped resolve adverse medical events without increasing lawsuits or leading to excessive payouts to patients, according to Michelle M. Mello, PhD, and her colleagues.

They evaluated a communication and resolution program (CRP) model known as CARe (Communication, Apology, and Resolution) implemented at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and at two of each center’s community hospitals. As part of the CARe model, hospital staff and insurers communicate with patients when adverse events occur, investigate and explain what happened, and, when appropriate, apologize and offer compensation.

Of 989 total events studied, 929 (90%) entered the program because an adverse event that allegedly exceeded the severity threshold was reported and 60 (6%) entered CARe because a prelitigation notice or claim was received, said Dr. Mello, professor of law and health research and policy at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Few events that entered the CARe process met the criteria for compensation. The standard of care was violated in 26% of cases where a determination could be reached. No determination could be reached in 59 cases, 9 cases were pending at the close of data collection, and 5 were referred directly to the insurer. Of the 241 cases involving standard-of-care violations, 55% were potentially eligible for compensation because they involved significant harm. After further review, monetary compensation was offered in 43 cases and paid in 40 cases by August 2016, with $75,000 as the median payment (Health Aff. 2017 Oct 2;36[10]:1795-1803).

As of August 2016, 5% of the 929 adverse events led to claims or lawsuits. Insurers deemed 14 of the 47 events that ultimately resulted in legal action ineligible for compensation because of a lack of negligence or lack of harm. They deemed 22 of the cases compensable, offered compensation in all of them, and had settled 20 by August 2016.

During the CARe process, patient safety improvements were frequently identified and improvements made, the investigators said. Of 132 cases in which review progressed far enough for patient safety questions to have been answered, 41% of the incidents gave rise to a safety improvement action. Actions included sharing investigation findings with clinical staff members, clinical staff educational efforts, policy changes, safety alerts sent to staff members, input into the quality improvement system for further analysis, new process flow diagrams, and human factor engineering analysis, among others.

Investigators also surveyed clinicians on their satisfaction with the CARe program. Of 162 clinicians (124 physicians), nearly 40% were either not very or not at all familiar with the program. More than two-thirds (69%) of those who felt well informed about the program gave strongly positive ratings and 10% gave a negative rating to the program. The most commonly suggested improvement to CARe was to improve communication with clinicians.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Out of 989 events, monetary compensation was paid in 40 cases, with a $75,000 median payment.

Data source: Review of 989 adverse events at four Massachusetts hospitals.

Disclosures: The project was funded by Baystate Health Insurance Company, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, CRICO RMF, Coverys, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Massachusetts Medical Society, and Tufts Health Plan. The authors listed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Advance care planning benefit presents challenges

When Donna Sweet, MD, sees patients for routine exams, death and dying are often the furthest thing from their minds. Regardless of age or health status, however, Dr. Sweet regularly asks patients about end-of-life care and whether they’ve considered their options.

In the past, physicians had to be creative in how they coded for such conversations, but Medicare’s newish advance care planning benefit is changing that.

Staring in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began reimbursing physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30-minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

Dr. Sweet said that she uses these codes a couple times a week when patients visit for reasons such as routine hypertension or diabetes exams or annual Medicare wellness visits. To broach the subject, Dr. Sweet said it helps to have literature about advance care planning in the room that patients can review.

“It’s just a matter of bringing it up,” she said. “Considering some of the other codes, the advance care planning code is really pretty simple.”

However, doctors like Dr. Sweet appear to be in the minority when it comes to providing this service. Of the nearly 57 million beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare at the end of 2016, only about 1% received advance care planning sessions, according to analysis of Medicare data posted by Kaiser Health News. Nationwide, health providers submitted about $93 million in charges, of which $43 million was paid by Medicare.

Challenges deter conversations

During a recent visit with a 72-year-old cancer patient, Bridget Fahy, MD, a surgical oncologist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, spent time discussing advance directives and the importance of naming a surrogate decision maker. Dr. Fahy had treated the patient for two different cancers over the course of 4 years, and he was now diagnosed with a third, she recalled during an interview. Figuring out an advance care plan, though, proved complicated: The man was not married, had no children, and had no family members who lived in the state.

Although Dr. Fahy was aware of the Medicare advance care planning codes, she did not bill the session as such.

“Even in the course of having that conversation, I’m more apt to bill on time than I am specifically to meet the Medicare requirements for the documentation for [the benefit],” she said.

“There are two pieces required to take advantage of the advance care planning benefit code: having the conversation and documenting it,” Dr. Fahy noted. “What I write at the end of a resident note or an advanced practice provider note is going to be more focused on the counseling I had with the patient about their condition, the evaluation, and what the treatment plan is going to be. For surgeons to utilize the advance care planning codes, they have to have knowledge of the code, which many do not; they must know the requirements for documenting the conversation; and they have to have the time needed to have the conversation while also addressing all of the surgery-specific issues that need to be covered during the visit. There are a number of hurdles to overcome.”

Danielle B. Scheurer, MD, a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said that she, too, has not used advance care planning codes. The reimbursement tool is a positive step forward, she said, but so far, it’s not an easy insert into a hospitalist’s practice.

“It’s not top of mind as far as a billing practice,” she said. “It’s not built into the typical work flow. Obviously, it’s not every patient, it’s not everyday, so you have to remember to put it into your work flow. That’s probably the biggest barrier for most hospitalists: either not knowing about it at all or not yet figuring out how to weave it into what they already do.”

Overcoming hurdles through experience

Using the advance care planning benefit has been easier said than done in his practice, according to Carl R. Olden, MD, a family physician in Yakima, Wash. The logistics of scheduling and patient reluctance are contributing to low usage of the new codes, said Dr. Olden, a member of the American Academy of Family Physicians board of directors.

Between Sept. 1, 2016, and Aug. 31, 2017, the family medicine, primary care, internal medicine, and pulmonary medicine members of Dr. Olden’s network who provide end-of-life counseling submitted billing for a total of 106,160 Medicare visits. Of those visits, the 99497 code was submitted only 32 times, according to data provided by Dr. Olden.

At Dr. Olden’s 16-physician practice, there are no registered nurses to help set up and start Medicare wellness visits, which the advance care planning session benefit is designed to fit within, he said.

“Most of those Medicare wellness visits are driven by having a registered nurse do most of the work,” he said. “[For us] to schedule a wellness visit, it’s mostly physician work and to do a 30-minute wellness visit, most of us can see three patients in that 30-minute slot, so it ends up not being very cost effective.”

“Most of my Medicare patients are folks that have four to five chronic medical conditions, and for them to make a 30-minute visit to the office and not talk about any of those conditions but to talk about home safety and advance directives and fall prevention, it’s hard for them to understand that,” he said.

Dr. Newman stresses that while the billing approach takes time to learn, the codes can be weaved into regular practice with some preparation and planning. At her practice, she primarily uses the codes for patients with challenging changes in their health status, sometimes setting up meetings in advance and, other times, conducting a spur-of-the-moment conversation.

“It’s a wonderful benefit,” she said. “I’m not surprised it’s taking awhile to take hold. The reason is you have to prepare for these visits. It takes preparation, including a chart review.”

A common misconception is that the visit must be scheduled separately and cannot be added to another visit, she said. Doctors can bill the advance care planning codes on the same day as an evaluation and management service. For instance, if a patient is accompanied by a family member and seen for routine follow-up, the physician can discuss the medical conditions first and later have a discussion about advance care planning. When billing, the physician can then use an evaluation and management code for the part of the visit related to the patient’s medical conditions and also bill for the advance care planning discussion using the new Medicare codes, Dr. Newman said.

“You’re allowed to use a modifier to attach to it to get paid for both on the same day,” she said. She suggested checking local Medicare policy for the use of the appropriate modifier, usually 26. “One thing that’s important to understand is there’s a lot of short discussions about advanced care planning that doesn’t fit the code. So if a patient wants to have a 5-minute conversation – that happens a lot – these will not be billable or counted under this new benefit. Fifteen minutes is the least amount of time that qualifies for 99497.”

Dr. Sweet said that she expects greater use of the codes as more doctors become aware of how they can be used.