User login

Health-Related Quality of Life and Toxicity After Definitive High-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy Among Veterans With Prostate Cancer

Nearly 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with cancer within the Veterans Health Administration annually with prostate cancer (PC) being the most frequently diagnosed, accounting for 29% of all cancers diagnosed.1 The treatment of PC depends on the stage and risk group at presentation and patient preference. Men with early stage, localized PC can be managed with prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.2

Within the Veterans Health Administration, more patients are treated with radiation therapy than with radical prostatectomy.3 This is in contrast to the civil health system, where more patients are treated with radical prostatectomy than with radiation therapy.4,5 Radiation therapy for PC can be given externally with external beam radiation therapy or internally with brachytherapy (BT). BT is categorized by the rate at which the radiation dose is delivered and generally grouped as low-dose rate (LDR) or high-dose rate (HDR). LDRBT consists of permanently implanting radioactive seeds, which slowly deliver a radiation dose over an extended period. HDRBT consists of implanting catheters that allow delivery of a radioactive source to be placed temporarily in the prostate and removed after treatment. The utilization of HDRBT has become more common as treatment has evolved to consist of fewer, larger fractions in a shorter time, making it a convenient treatment option for men with PC.6 The veteran population has singular medical challenges. These patients differ from the general population and are often underrepresented in medical research and published studies.7 There are no studies exploring the treatment-associated toxicities from HDRBT treatment for PC specifically in the veteran population. The objective of this study is to report our findings regarding the veteran-reported and physician-graded toxicities associated with HDRBT as monotherapy in veterans treated through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for PC.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of a prospectively maintained, institutional review board-approved database of patients treated with HDRBT for PC. Veterans were seen in consultation at Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois. This is the only VA hospital in Illinois that offers radiation therapy, so it acted as a tertiary center, receiving referrals from other, neighboring VA hospitals. If the veteran was deemed a good BT candidate and elected to proceed with HDRBT, HDR treatment was performed at a partnering academic institution equipped to provide HDRBT (Loyola University Medical Center).

We selected patients with National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDRBT as monotherapy using 13.5 Gy x 2 fractions delivered over 2 implants that were 1 to 2 weeks apart. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) were excluded from this study. No patients received supplemental external beam radiation. Men with unfavorable intermediate risk PC were offered ADT and BT in accordance with NCCN guidelines. However, patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk PC who declined ADT or who were deemed poor ADT candidates due to comorbidities were treated with HDR as monotherapy and included in this study.8

HDR Treatment

Our HDRBT implant procedure and treatment planning details have been previously described.9 In brief, patients were implanted with between 17 and 22 catheters based on gland size under transrectal ultrasound guidance. After implantation, computed tomography and, when possible, magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate were obtained and registered for target delineation. The prostate was segmented, and an asymmetric planning target volume of 0 to 5 mm was created and extended to encompass the proximal seminal vesicles. The second fraction was given 1 to 2 weeks after initial treatment, based on patient, physician, and operating room availability.

Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

Veteran-reported genitourinary (GU), gastrointestinal (GI), and sexual health-related quality of life (hrQOL) were assessed using the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26) instruments.10,11 Baseline veteran-reported hrQOL scores in the GU, GI, and sexual domains were obtained prior to each veteran’s first HDR treatment. Veteran-reported hrQOL scores were assessed at each of the patient’s follow-up appointments. Physician-graded toxicity was assessed Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.03 criteria.12 Physician-graded toxicity was assessed at each follow-up visit and reported as the highest grade reported during any follow-up examination.

Follow-up appointments typically occurred at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and subsequently every 6 months after the second HDR treatment. Follow-up appointments were conducted in the radiation oncology department at EHJVAH.

Minimal Clinically Important Differences

To evaluate the veteran-reported hrQOL, we characterized statistically significant differences in IPSS or EPIC-26 scores over time as compared with baseline values as clinically important or not clinically important through the use of reported minimal clinically important difference (MCID) assessments.13-15 For the IPSS, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 3.0 points represented a clinically meaningful change in urinary function.14 For the EPIC-26 scores, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 6 points for urinary incontinence score, ≥ 5 points for urinary obstruction score, ≥ 4 points for bowel score, and ≥ 10 points for sexual score to represent an MCID.15

Statistical Analysis

Changes in veteran-reported hrQOL over time were compared using mixed linear effects models, with the time since the last BT implant serving as the fixed variable. Effects were deemed statistically significant if P < .05. If a statistically significant difference from baseline was found at any time point, additional evaluation was done to see if the numerical difference in the assessment led to an MCID as described above. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

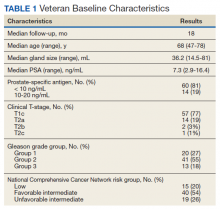

Seventy-four veterans were included in the study. The median follow-up was 18 months (range 1-43). The demographic and oncologic specifics of the treated veterans are outlined in Table 1.

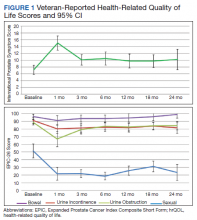

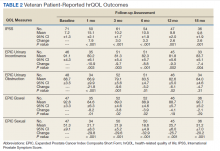

There was a significant increase in IPSS (P < .001) with reciprocal decline in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence (P = .008) and EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores (P = .001) from baseline over time (Table 2 and Figure 1). At the 18-month follow-up assessment, there was no longer a significant difference in the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction score from baseline (88.7 vs 84.0, P = .31). The increases in IPSS at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month assessments met the criteria for MCID. The decrease in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month assessments were found to be an MCID, as were the decrease in EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month assessments.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 bowel scores from baseline over time (P = .03). The decline in the EPIC-26 bowel hrQOL scores at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up assessment were significantly different from the baseline value. However, only the decrease seen at the 1-month assessment met criteria for MCID.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 sexual scores from baseline over time (P < .001). The decline in EPIC-26 sexual score noted at each follow-up compared with baseline was statistically significant. Each of these declines met criteria for an MCID.

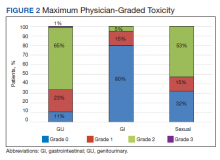

The rate of grade 2 GU, GI, and sexual physician-graded toxicity was 65%, 5%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 2). There was a single incident of grade 3 GU toxicity, which was a urethral stricture. There were no reported grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, nor were there grade 4 or 5 toxicities. There were 5 total incidents of acute urinary retention for a 6.8% rate overall.

Discussion

We performed a retrospective study of veterans with low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDR prostate BT as monotherapy. We found that veterans experienced immediate declines in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. However, each trended toward a return to baseline over time, with the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction and the EPIC-26 bowel scores showing no difference from the baseline value within 18 months and 12 months, respectively. The physician-reported toxicities were low, with only 1 incidence of grade 3 GU toxicity, no grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, and no grade 4 or 5 toxicity. This suggests that HDRBT is a well-tolerated and safe, definitive treatment for veterans with localized PC.

In a series similar to ours, Gaudet and colleagues reported on their single institutional results of treating 30 low- or intermediate-risk PC patients with HDRBT as monotherapy.16 Patients included in their study were civilians from the general population, treated in a similar fashion to the veterans treated in our study. Each patient received 27 Gy in 2 fractions given over 2 implants. The authors collected patient-reported hrQOL results using the IPSS and EPIC questionnaires and found that 57% of patients treated experienced moderate-to-severe urinary symptoms at the 1-month assessment after implantation, with a rapid recovery toward baseline over time. In contrast, GI symptoms did not change from baseline, while sexual symptoms worsened after implantation and failed to return to baseline.

Our results mirror this experience, with similar rates of patient-reported hrQOL scores and physician-graded toxicities. Patients reported similar rates of decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. The patient-reported GU and GI hrQOL scores worsened immediately after treatment, with a return toward baseline over time. However, the patient-reported sexual hrQOL dropped after treatment and had a subtle trend toward a return to baseline. Our data show higher rates of maximum physician-graded GU toxicity rates of 23%, 65%, and 1% grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This is likely due in part to our prophylactic use of tamsulosin. Patients who continued tamsulosin after the implant out of preference were technically grade 2 based on CTCAE v5.0 criteria. GI and sexual toxicity were substantially lower with rates of 15% and 5% grade 1 and grade 2 bowel toxicity with no grade 3 events, and 15% and 52% grade 1 and grade 2 sexual toxicity, respectively.

Contreras and colleagues also reported on treating civilian patients with HDRBT as monotherapy for PC.17 They, too, found similar results as in our veteran study, with a rapid decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL scores immediately after treatment. They also found a gradual return to baseline in the GU hrQOL scores. Contrary to our results, they reported a return to baseline in sexual hrQOL scores, while their patients did not report a return to baseline in the GI hrQOL scores.

Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other studies exploring HDR prostate BT toxicity in a veteran-specific population, and our study is novel in addressing this question. One limitation of the study is the relatively short median follow-up time of 18 months. With this limitation, our data were not yet sufficiently mature to perform biochemical control or overall survival analyses. The next step in our study is to calculate these clinical endpoints from our data after longer follow-up.

An additional limitation to our study is the single institutional nature of the design. While veterans from neighboring VA hospitals were included in the study by way of referral and treatment at our center, the only VA hospital in the state to provide radiation therapy, our patient population remains limited. Further multi-institutional and prospective data are needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

HDR prostate BT as monotherapy is feasible with a favorable veteran-reported hrQOL and physician-graded toxicity profile. Veterans should be educated about this treatment modality when considering the optimal treatment for their localized prostate cancer.

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883‐e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Skolarus TA, Hawley ST. Prostate cancer survivorship care in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2014;31(8):10‐17.

3. Nambudiri VE, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Understanding variation in primary prostate cancer treatment within the Veterans Health Administration. Urology. 2012;79(3):537‐545. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.013

4. Harlan LC, Potosky A, Gilliland FD, et al. Factors associated with initial therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1864-1871. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.24.1864

5. Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Factors influencing prostate cancer patterns of care: an analysis of treatment variation using the SEER database. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2):170-180. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2017.12.008

6. Crook J, Marbán M, Batchelar D. HDR prostate brachytherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020;30(1):49‐60. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.08.003

7. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252.

8. D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):289-295. doi:10.1001/jama.299.3.289

9. Solanki AA, Mysz ML, Patel R, et al. Transitioning from a low-dose-rate to a high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy program: comparing initial dosimetry and improving workflow efficiency through targeted interventions. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019;4(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2018.10.004

10. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549‐1564. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5

11. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899‐905. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). version 4.03. Updated June 14, 2010. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

13. McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1342-1343. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13128

14. Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association Symptom Index and the Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154(5):1770-1774. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66780-6

15. Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–105. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044

16. Gaudet M, Pharand-Charbonneau M, Desrosiers MP, Wright D, Haddad A. Early toxicity and health-related quality of life results of high-dose-rate brachytherapy as monotherapy for low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2018;17(3):524-529. doi:10.1016/j.brachy.2018.01.009

17. Contreras JA, Wilder RB, Mellon EA, Strom TJ, Fernandez DC, Biagioli MC. Quality of life after high-dose-rate brachytherapy monotherapy for prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(1):40-45. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.07

Nearly 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with cancer within the Veterans Health Administration annually with prostate cancer (PC) being the most frequently diagnosed, accounting for 29% of all cancers diagnosed.1 The treatment of PC depends on the stage and risk group at presentation and patient preference. Men with early stage, localized PC can be managed with prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.2

Within the Veterans Health Administration, more patients are treated with radiation therapy than with radical prostatectomy.3 This is in contrast to the civil health system, where more patients are treated with radical prostatectomy than with radiation therapy.4,5 Radiation therapy for PC can be given externally with external beam radiation therapy or internally with brachytherapy (BT). BT is categorized by the rate at which the radiation dose is delivered and generally grouped as low-dose rate (LDR) or high-dose rate (HDR). LDRBT consists of permanently implanting radioactive seeds, which slowly deliver a radiation dose over an extended period. HDRBT consists of implanting catheters that allow delivery of a radioactive source to be placed temporarily in the prostate and removed after treatment. The utilization of HDRBT has become more common as treatment has evolved to consist of fewer, larger fractions in a shorter time, making it a convenient treatment option for men with PC.6 The veteran population has singular medical challenges. These patients differ from the general population and are often underrepresented in medical research and published studies.7 There are no studies exploring the treatment-associated toxicities from HDRBT treatment for PC specifically in the veteran population. The objective of this study is to report our findings regarding the veteran-reported and physician-graded toxicities associated with HDRBT as monotherapy in veterans treated through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for PC.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of a prospectively maintained, institutional review board-approved database of patients treated with HDRBT for PC. Veterans were seen in consultation at Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois. This is the only VA hospital in Illinois that offers radiation therapy, so it acted as a tertiary center, receiving referrals from other, neighboring VA hospitals. If the veteran was deemed a good BT candidate and elected to proceed with HDRBT, HDR treatment was performed at a partnering academic institution equipped to provide HDRBT (Loyola University Medical Center).

We selected patients with National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDRBT as monotherapy using 13.5 Gy x 2 fractions delivered over 2 implants that were 1 to 2 weeks apart. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) were excluded from this study. No patients received supplemental external beam radiation. Men with unfavorable intermediate risk PC were offered ADT and BT in accordance with NCCN guidelines. However, patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk PC who declined ADT or who were deemed poor ADT candidates due to comorbidities were treated with HDR as monotherapy and included in this study.8

HDR Treatment

Our HDRBT implant procedure and treatment planning details have been previously described.9 In brief, patients were implanted with between 17 and 22 catheters based on gland size under transrectal ultrasound guidance. After implantation, computed tomography and, when possible, magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate were obtained and registered for target delineation. The prostate was segmented, and an asymmetric planning target volume of 0 to 5 mm was created and extended to encompass the proximal seminal vesicles. The second fraction was given 1 to 2 weeks after initial treatment, based on patient, physician, and operating room availability.

Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

Veteran-reported genitourinary (GU), gastrointestinal (GI), and sexual health-related quality of life (hrQOL) were assessed using the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26) instruments.10,11 Baseline veteran-reported hrQOL scores in the GU, GI, and sexual domains were obtained prior to each veteran’s first HDR treatment. Veteran-reported hrQOL scores were assessed at each of the patient’s follow-up appointments. Physician-graded toxicity was assessed Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.03 criteria.12 Physician-graded toxicity was assessed at each follow-up visit and reported as the highest grade reported during any follow-up examination.

Follow-up appointments typically occurred at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and subsequently every 6 months after the second HDR treatment. Follow-up appointments were conducted in the radiation oncology department at EHJVAH.

Minimal Clinically Important Differences

To evaluate the veteran-reported hrQOL, we characterized statistically significant differences in IPSS or EPIC-26 scores over time as compared with baseline values as clinically important or not clinically important through the use of reported minimal clinically important difference (MCID) assessments.13-15 For the IPSS, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 3.0 points represented a clinically meaningful change in urinary function.14 For the EPIC-26 scores, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 6 points for urinary incontinence score, ≥ 5 points for urinary obstruction score, ≥ 4 points for bowel score, and ≥ 10 points for sexual score to represent an MCID.15

Statistical Analysis

Changes in veteran-reported hrQOL over time were compared using mixed linear effects models, with the time since the last BT implant serving as the fixed variable. Effects were deemed statistically significant if P < .05. If a statistically significant difference from baseline was found at any time point, additional evaluation was done to see if the numerical difference in the assessment led to an MCID as described above. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

Seventy-four veterans were included in the study. The median follow-up was 18 months (range 1-43). The demographic and oncologic specifics of the treated veterans are outlined in Table 1.

There was a significant increase in IPSS (P < .001) with reciprocal decline in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence (P = .008) and EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores (P = .001) from baseline over time (Table 2 and Figure 1). At the 18-month follow-up assessment, there was no longer a significant difference in the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction score from baseline (88.7 vs 84.0, P = .31). The increases in IPSS at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month assessments met the criteria for MCID. The decrease in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month assessments were found to be an MCID, as were the decrease in EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month assessments.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 bowel scores from baseline over time (P = .03). The decline in the EPIC-26 bowel hrQOL scores at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up assessment were significantly different from the baseline value. However, only the decrease seen at the 1-month assessment met criteria for MCID.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 sexual scores from baseline over time (P < .001). The decline in EPIC-26 sexual score noted at each follow-up compared with baseline was statistically significant. Each of these declines met criteria for an MCID.

The rate of grade 2 GU, GI, and sexual physician-graded toxicity was 65%, 5%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 2). There was a single incident of grade 3 GU toxicity, which was a urethral stricture. There were no reported grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, nor were there grade 4 or 5 toxicities. There were 5 total incidents of acute urinary retention for a 6.8% rate overall.

Discussion

We performed a retrospective study of veterans with low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDR prostate BT as monotherapy. We found that veterans experienced immediate declines in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. However, each trended toward a return to baseline over time, with the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction and the EPIC-26 bowel scores showing no difference from the baseline value within 18 months and 12 months, respectively. The physician-reported toxicities were low, with only 1 incidence of grade 3 GU toxicity, no grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, and no grade 4 or 5 toxicity. This suggests that HDRBT is a well-tolerated and safe, definitive treatment for veterans with localized PC.

In a series similar to ours, Gaudet and colleagues reported on their single institutional results of treating 30 low- or intermediate-risk PC patients with HDRBT as monotherapy.16 Patients included in their study were civilians from the general population, treated in a similar fashion to the veterans treated in our study. Each patient received 27 Gy in 2 fractions given over 2 implants. The authors collected patient-reported hrQOL results using the IPSS and EPIC questionnaires and found that 57% of patients treated experienced moderate-to-severe urinary symptoms at the 1-month assessment after implantation, with a rapid recovery toward baseline over time. In contrast, GI symptoms did not change from baseline, while sexual symptoms worsened after implantation and failed to return to baseline.

Our results mirror this experience, with similar rates of patient-reported hrQOL scores and physician-graded toxicities. Patients reported similar rates of decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. The patient-reported GU and GI hrQOL scores worsened immediately after treatment, with a return toward baseline over time. However, the patient-reported sexual hrQOL dropped after treatment and had a subtle trend toward a return to baseline. Our data show higher rates of maximum physician-graded GU toxicity rates of 23%, 65%, and 1% grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This is likely due in part to our prophylactic use of tamsulosin. Patients who continued tamsulosin after the implant out of preference were technically grade 2 based on CTCAE v5.0 criteria. GI and sexual toxicity were substantially lower with rates of 15% and 5% grade 1 and grade 2 bowel toxicity with no grade 3 events, and 15% and 52% grade 1 and grade 2 sexual toxicity, respectively.

Contreras and colleagues also reported on treating civilian patients with HDRBT as monotherapy for PC.17 They, too, found similar results as in our veteran study, with a rapid decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL scores immediately after treatment. They also found a gradual return to baseline in the GU hrQOL scores. Contrary to our results, they reported a return to baseline in sexual hrQOL scores, while their patients did not report a return to baseline in the GI hrQOL scores.

Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other studies exploring HDR prostate BT toxicity in a veteran-specific population, and our study is novel in addressing this question. One limitation of the study is the relatively short median follow-up time of 18 months. With this limitation, our data were not yet sufficiently mature to perform biochemical control or overall survival analyses. The next step in our study is to calculate these clinical endpoints from our data after longer follow-up.

An additional limitation to our study is the single institutional nature of the design. While veterans from neighboring VA hospitals were included in the study by way of referral and treatment at our center, the only VA hospital in the state to provide radiation therapy, our patient population remains limited. Further multi-institutional and prospective data are needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

HDR prostate BT as monotherapy is feasible with a favorable veteran-reported hrQOL and physician-graded toxicity profile. Veterans should be educated about this treatment modality when considering the optimal treatment for their localized prostate cancer.

Nearly 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with cancer within the Veterans Health Administration annually with prostate cancer (PC) being the most frequently diagnosed, accounting for 29% of all cancers diagnosed.1 The treatment of PC depends on the stage and risk group at presentation and patient preference. Men with early stage, localized PC can be managed with prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.2

Within the Veterans Health Administration, more patients are treated with radiation therapy than with radical prostatectomy.3 This is in contrast to the civil health system, where more patients are treated with radical prostatectomy than with radiation therapy.4,5 Radiation therapy for PC can be given externally with external beam radiation therapy or internally with brachytherapy (BT). BT is categorized by the rate at which the radiation dose is delivered and generally grouped as low-dose rate (LDR) or high-dose rate (HDR). LDRBT consists of permanently implanting radioactive seeds, which slowly deliver a radiation dose over an extended period. HDRBT consists of implanting catheters that allow delivery of a radioactive source to be placed temporarily in the prostate and removed after treatment. The utilization of HDRBT has become more common as treatment has evolved to consist of fewer, larger fractions in a shorter time, making it a convenient treatment option for men with PC.6 The veteran population has singular medical challenges. These patients differ from the general population and are often underrepresented in medical research and published studies.7 There are no studies exploring the treatment-associated toxicities from HDRBT treatment for PC specifically in the veteran population. The objective of this study is to report our findings regarding the veteran-reported and physician-graded toxicities associated with HDRBT as monotherapy in veterans treated through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for PC.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of a prospectively maintained, institutional review board-approved database of patients treated with HDRBT for PC. Veterans were seen in consultation at Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois. This is the only VA hospital in Illinois that offers radiation therapy, so it acted as a tertiary center, receiving referrals from other, neighboring VA hospitals. If the veteran was deemed a good BT candidate and elected to proceed with HDRBT, HDR treatment was performed at a partnering academic institution equipped to provide HDRBT (Loyola University Medical Center).

We selected patients with National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDRBT as monotherapy using 13.5 Gy x 2 fractions delivered over 2 implants that were 1 to 2 weeks apart. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) were excluded from this study. No patients received supplemental external beam radiation. Men with unfavorable intermediate risk PC were offered ADT and BT in accordance with NCCN guidelines. However, patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk PC who declined ADT or who were deemed poor ADT candidates due to comorbidities were treated with HDR as monotherapy and included in this study.8

HDR Treatment

Our HDRBT implant procedure and treatment planning details have been previously described.9 In brief, patients were implanted with between 17 and 22 catheters based on gland size under transrectal ultrasound guidance. After implantation, computed tomography and, when possible, magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate were obtained and registered for target delineation. The prostate was segmented, and an asymmetric planning target volume of 0 to 5 mm was created and extended to encompass the proximal seminal vesicles. The second fraction was given 1 to 2 weeks after initial treatment, based on patient, physician, and operating room availability.

Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

Veteran-reported genitourinary (GU), gastrointestinal (GI), and sexual health-related quality of life (hrQOL) were assessed using the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26) instruments.10,11 Baseline veteran-reported hrQOL scores in the GU, GI, and sexual domains were obtained prior to each veteran’s first HDR treatment. Veteran-reported hrQOL scores were assessed at each of the patient’s follow-up appointments. Physician-graded toxicity was assessed Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.03 criteria.12 Physician-graded toxicity was assessed at each follow-up visit and reported as the highest grade reported during any follow-up examination.

Follow-up appointments typically occurred at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and subsequently every 6 months after the second HDR treatment. Follow-up appointments were conducted in the radiation oncology department at EHJVAH.

Minimal Clinically Important Differences

To evaluate the veteran-reported hrQOL, we characterized statistically significant differences in IPSS or EPIC-26 scores over time as compared with baseline values as clinically important or not clinically important through the use of reported minimal clinically important difference (MCID) assessments.13-15 For the IPSS, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 3.0 points represented a clinically meaningful change in urinary function.14 For the EPIC-26 scores, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 6 points for urinary incontinence score, ≥ 5 points for urinary obstruction score, ≥ 4 points for bowel score, and ≥ 10 points for sexual score to represent an MCID.15

Statistical Analysis

Changes in veteran-reported hrQOL over time were compared using mixed linear effects models, with the time since the last BT implant serving as the fixed variable. Effects were deemed statistically significant if P < .05. If a statistically significant difference from baseline was found at any time point, additional evaluation was done to see if the numerical difference in the assessment led to an MCID as described above. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

Seventy-four veterans were included in the study. The median follow-up was 18 months (range 1-43). The demographic and oncologic specifics of the treated veterans are outlined in Table 1.

There was a significant increase in IPSS (P < .001) with reciprocal decline in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence (P = .008) and EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores (P = .001) from baseline over time (Table 2 and Figure 1). At the 18-month follow-up assessment, there was no longer a significant difference in the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction score from baseline (88.7 vs 84.0, P = .31). The increases in IPSS at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month assessments met the criteria for MCID. The decrease in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month assessments were found to be an MCID, as were the decrease in EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month assessments.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 bowel scores from baseline over time (P = .03). The decline in the EPIC-26 bowel hrQOL scores at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up assessment were significantly different from the baseline value. However, only the decrease seen at the 1-month assessment met criteria for MCID.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 sexual scores from baseline over time (P < .001). The decline in EPIC-26 sexual score noted at each follow-up compared with baseline was statistically significant. Each of these declines met criteria for an MCID.

The rate of grade 2 GU, GI, and sexual physician-graded toxicity was 65%, 5%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 2). There was a single incident of grade 3 GU toxicity, which was a urethral stricture. There were no reported grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, nor were there grade 4 or 5 toxicities. There were 5 total incidents of acute urinary retention for a 6.8% rate overall.

Discussion

We performed a retrospective study of veterans with low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDR prostate BT as monotherapy. We found that veterans experienced immediate declines in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. However, each trended toward a return to baseline over time, with the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction and the EPIC-26 bowel scores showing no difference from the baseline value within 18 months and 12 months, respectively. The physician-reported toxicities were low, with only 1 incidence of grade 3 GU toxicity, no grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, and no grade 4 or 5 toxicity. This suggests that HDRBT is a well-tolerated and safe, definitive treatment for veterans with localized PC.

In a series similar to ours, Gaudet and colleagues reported on their single institutional results of treating 30 low- or intermediate-risk PC patients with HDRBT as monotherapy.16 Patients included in their study were civilians from the general population, treated in a similar fashion to the veterans treated in our study. Each patient received 27 Gy in 2 fractions given over 2 implants. The authors collected patient-reported hrQOL results using the IPSS and EPIC questionnaires and found that 57% of patients treated experienced moderate-to-severe urinary symptoms at the 1-month assessment after implantation, with a rapid recovery toward baseline over time. In contrast, GI symptoms did not change from baseline, while sexual symptoms worsened after implantation and failed to return to baseline.

Our results mirror this experience, with similar rates of patient-reported hrQOL scores and physician-graded toxicities. Patients reported similar rates of decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. The patient-reported GU and GI hrQOL scores worsened immediately after treatment, with a return toward baseline over time. However, the patient-reported sexual hrQOL dropped after treatment and had a subtle trend toward a return to baseline. Our data show higher rates of maximum physician-graded GU toxicity rates of 23%, 65%, and 1% grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This is likely due in part to our prophylactic use of tamsulosin. Patients who continued tamsulosin after the implant out of preference were technically grade 2 based on CTCAE v5.0 criteria. GI and sexual toxicity were substantially lower with rates of 15% and 5% grade 1 and grade 2 bowel toxicity with no grade 3 events, and 15% and 52% grade 1 and grade 2 sexual toxicity, respectively.

Contreras and colleagues also reported on treating civilian patients with HDRBT as monotherapy for PC.17 They, too, found similar results as in our veteran study, with a rapid decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL scores immediately after treatment. They also found a gradual return to baseline in the GU hrQOL scores. Contrary to our results, they reported a return to baseline in sexual hrQOL scores, while their patients did not report a return to baseline in the GI hrQOL scores.

Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other studies exploring HDR prostate BT toxicity in a veteran-specific population, and our study is novel in addressing this question. One limitation of the study is the relatively short median follow-up time of 18 months. With this limitation, our data were not yet sufficiently mature to perform biochemical control or overall survival analyses. The next step in our study is to calculate these clinical endpoints from our data after longer follow-up.

An additional limitation to our study is the single institutional nature of the design. While veterans from neighboring VA hospitals were included in the study by way of referral and treatment at our center, the only VA hospital in the state to provide radiation therapy, our patient population remains limited. Further multi-institutional and prospective data are needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

HDR prostate BT as monotherapy is feasible with a favorable veteran-reported hrQOL and physician-graded toxicity profile. Veterans should be educated about this treatment modality when considering the optimal treatment for their localized prostate cancer.

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883‐e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Skolarus TA, Hawley ST. Prostate cancer survivorship care in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2014;31(8):10‐17.

3. Nambudiri VE, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Understanding variation in primary prostate cancer treatment within the Veterans Health Administration. Urology. 2012;79(3):537‐545. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.013

4. Harlan LC, Potosky A, Gilliland FD, et al. Factors associated with initial therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1864-1871. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.24.1864

5. Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Factors influencing prostate cancer patterns of care: an analysis of treatment variation using the SEER database. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2):170-180. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2017.12.008

6. Crook J, Marbán M, Batchelar D. HDR prostate brachytherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020;30(1):49‐60. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.08.003

7. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252.

8. D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):289-295. doi:10.1001/jama.299.3.289

9. Solanki AA, Mysz ML, Patel R, et al. Transitioning from a low-dose-rate to a high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy program: comparing initial dosimetry and improving workflow efficiency through targeted interventions. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019;4(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2018.10.004

10. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549‐1564. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5

11. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899‐905. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). version 4.03. Updated June 14, 2010. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

13. McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1342-1343. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13128

14. Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association Symptom Index and the Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154(5):1770-1774. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66780-6

15. Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–105. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044

16. Gaudet M, Pharand-Charbonneau M, Desrosiers MP, Wright D, Haddad A. Early toxicity and health-related quality of life results of high-dose-rate brachytherapy as monotherapy for low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2018;17(3):524-529. doi:10.1016/j.brachy.2018.01.009

17. Contreras JA, Wilder RB, Mellon EA, Strom TJ, Fernandez DC, Biagioli MC. Quality of life after high-dose-rate brachytherapy monotherapy for prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(1):40-45. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.07

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883‐e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Skolarus TA, Hawley ST. Prostate cancer survivorship care in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2014;31(8):10‐17.

3. Nambudiri VE, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Understanding variation in primary prostate cancer treatment within the Veterans Health Administration. Urology. 2012;79(3):537‐545. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.013

4. Harlan LC, Potosky A, Gilliland FD, et al. Factors associated with initial therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1864-1871. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.24.1864

5. Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Factors influencing prostate cancer patterns of care: an analysis of treatment variation using the SEER database. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2):170-180. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2017.12.008

6. Crook J, Marbán M, Batchelar D. HDR prostate brachytherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020;30(1):49‐60. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.08.003

7. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252.

8. D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):289-295. doi:10.1001/jama.299.3.289

9. Solanki AA, Mysz ML, Patel R, et al. Transitioning from a low-dose-rate to a high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy program: comparing initial dosimetry and improving workflow efficiency through targeted interventions. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019;4(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2018.10.004

10. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549‐1564. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5

11. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899‐905. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). version 4.03. Updated June 14, 2010. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

13. McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1342-1343. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13128

14. Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association Symptom Index and the Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154(5):1770-1774. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66780-6

15. Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–105. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044

16. Gaudet M, Pharand-Charbonneau M, Desrosiers MP, Wright D, Haddad A. Early toxicity and health-related quality of life results of high-dose-rate brachytherapy as monotherapy for low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2018;17(3):524-529. doi:10.1016/j.brachy.2018.01.009

17. Contreras JA, Wilder RB, Mellon EA, Strom TJ, Fernandez DC, Biagioli MC. Quality of life after high-dose-rate brachytherapy monotherapy for prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(1):40-45. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.07