User login

CUBE-C initiative aims to educate about atopic dermatitis

WASHINGTON – The National Eczema Association (NEA) has established the Coalition United for Better Eczema Care (CUBE-C) to provide practitioners with a resource for “trustworthy, up-to-date, state of the art” information on atopic dermatitis, with the goal of improving health outcomes, according to Julie Block, president and chief executive officer of the NEA.

In an interview at a symposium presented by CUBE-C, Ms. Block provided more information on CUBE-C, including how and why it started and what it can offer to dermatologists, as well as primary care physicians, who care for patients with atopic dermatitis. She said that the NEA convened dermatologists, allergists, immunologists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and patients “to design a curriculum that provided an entire picture of the patient experience, so that we could go out and educate not only on the basics of eczema and atopic dermatitis for a variety of practitioners ... but also for the specialists who are now going to be engaging in new innovations and new therapies for their patients.”

She was joined by Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology and residency program director at George Washington University, Washington, where the symposium, a resident’s boot camp, was held. The boot camp was somewhat unique in that it was geared more towards trainees; typically, the CUBE-C program is a CME program for practitioners, but this reflects the flexibility of the program, which can be tailored to the audience, Dr. Friedman pointed out. “The hope is that programs like these pop up all over the place ... anywhere you have a critical mass of individuals who want to learn about this,” where planners can choose from a menu of topics provided by CUBE-C – which include therapeutics, infections, pathogenesis, and access to care – and “easily formulate a conference like we held here today for the right audience.”

Topics covered at the George Washington University symposium included the impact of climate on the prevalence of childhood eczema, the diagnosis and differential diagnosis in children, infections in atopic dermatitis patients, and itch treatment.

More information on CUBE-C is available on the NEA website.

The symposium was supported by an educational grant from Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. Dr. Friedman reported serving as a speaker for Regeneron, Pfizer, and other companies. He also consults and serves on the advisory board for Pfizer and multiple other companies developing and marketing atopic dermatitis therapies and products.

WASHINGTON – The National Eczema Association (NEA) has established the Coalition United for Better Eczema Care (CUBE-C) to provide practitioners with a resource for “trustworthy, up-to-date, state of the art” information on atopic dermatitis, with the goal of improving health outcomes, according to Julie Block, president and chief executive officer of the NEA.

In an interview at a symposium presented by CUBE-C, Ms. Block provided more information on CUBE-C, including how and why it started and what it can offer to dermatologists, as well as primary care physicians, who care for patients with atopic dermatitis. She said that the NEA convened dermatologists, allergists, immunologists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and patients “to design a curriculum that provided an entire picture of the patient experience, so that we could go out and educate not only on the basics of eczema and atopic dermatitis for a variety of practitioners ... but also for the specialists who are now going to be engaging in new innovations and new therapies for their patients.”

She was joined by Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology and residency program director at George Washington University, Washington, where the symposium, a resident’s boot camp, was held. The boot camp was somewhat unique in that it was geared more towards trainees; typically, the CUBE-C program is a CME program for practitioners, but this reflects the flexibility of the program, which can be tailored to the audience, Dr. Friedman pointed out. “The hope is that programs like these pop up all over the place ... anywhere you have a critical mass of individuals who want to learn about this,” where planners can choose from a menu of topics provided by CUBE-C – which include therapeutics, infections, pathogenesis, and access to care – and “easily formulate a conference like we held here today for the right audience.”

Topics covered at the George Washington University symposium included the impact of climate on the prevalence of childhood eczema, the diagnosis and differential diagnosis in children, infections in atopic dermatitis patients, and itch treatment.

More information on CUBE-C is available on the NEA website.

The symposium was supported by an educational grant from Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. Dr. Friedman reported serving as a speaker for Regeneron, Pfizer, and other companies. He also consults and serves on the advisory board for Pfizer and multiple other companies developing and marketing atopic dermatitis therapies and products.

WASHINGTON – The National Eczema Association (NEA) has established the Coalition United for Better Eczema Care (CUBE-C) to provide practitioners with a resource for “trustworthy, up-to-date, state of the art” information on atopic dermatitis, with the goal of improving health outcomes, according to Julie Block, president and chief executive officer of the NEA.

In an interview at a symposium presented by CUBE-C, Ms. Block provided more information on CUBE-C, including how and why it started and what it can offer to dermatologists, as well as primary care physicians, who care for patients with atopic dermatitis. She said that the NEA convened dermatologists, allergists, immunologists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and patients “to design a curriculum that provided an entire picture of the patient experience, so that we could go out and educate not only on the basics of eczema and atopic dermatitis for a variety of practitioners ... but also for the specialists who are now going to be engaging in new innovations and new therapies for their patients.”

She was joined by Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology and residency program director at George Washington University, Washington, where the symposium, a resident’s boot camp, was held. The boot camp was somewhat unique in that it was geared more towards trainees; typically, the CUBE-C program is a CME program for practitioners, but this reflects the flexibility of the program, which can be tailored to the audience, Dr. Friedman pointed out. “The hope is that programs like these pop up all over the place ... anywhere you have a critical mass of individuals who want to learn about this,” where planners can choose from a menu of topics provided by CUBE-C – which include therapeutics, infections, pathogenesis, and access to care – and “easily formulate a conference like we held here today for the right audience.”

Topics covered at the George Washington University symposium included the impact of climate on the prevalence of childhood eczema, the diagnosis and differential diagnosis in children, infections in atopic dermatitis patients, and itch treatment.

More information on CUBE-C is available on the NEA website.

The symposium was supported by an educational grant from Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. Dr. Friedman reported serving as a speaker for Regeneron, Pfizer, and other companies. He also consults and serves on the advisory board for Pfizer and multiple other companies developing and marketing atopic dermatitis therapies and products.

Treating substance use disorders: What do you do after withdrawal?

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

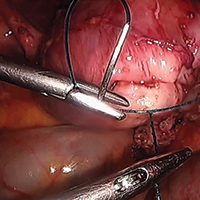

Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by

Incident heart failure linked to HIV infection

AMSTERDAM –

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“HIV infection is independently associated with a higher risk for developing heart failure, and this excess risk does not appear mediated through atherosclerotic disease pathways or differential use of cardioprotective medications,” Alan S. Go, MD, said at the 22nd International AIDS Conference.

The finding sends two important messages to physicians who care for people living with HIV, Dr. Go said in a video interview. First, have “greater awareness for the risk of heart failure” in people living with HIV, even in those who have excellent [HIV] treatment. Be on the lookout, he recommended, for classic symptoms of heart failure like dyspnea and fatigue, and if found follow-up with an assessment of heart function, usually by echocardiography. The second message is to pay attention to and aggressively treat risk factors for heart failure, such as hypertension, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia, said Dr. Go, director of the Comprehensive Clinical Research Unit of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif.

Results from a small number of prior studies also suggested an increased heart failure rate in people infected with HIV, but those reports had not been able to untangle this observed increase from a possible relationship to the elevated rate of MIs among people living with HIV. The study led by Dr. Go adjusted for acute coronary syndrome events that occurred during follow-up in the analysis and this showed that the increased incidence of heart failure occurred independently of any preceding MI or unstable angina event.

Dr. Go proposed several potential mechanisms that could tie HIV infection to an elevated heart failure risk that was not linked to a prior ischemic heart disease event. The virus could directly damage cardiac myocytes to produce fibrosis, the virus could trigger cardiac inflammation, and the infected person could have an increased susceptibility to infection by a pathogen know to potentially cause cardiac damage and myocarditis such as coxsackievirus.

For the time being, patients infected by HIV who develop heart failure should receive the same treatments that are recommended for the general population, Dr. Go said, but he also highlighted the need for further study to determine the effectiveness of standard heart failure treatments specifically in people living with HIV. He and his associates are also currently analyzing the relationship of several other variables to the risk for heart failure in HIV-infected people, such as the degree of HIV control, and the types of antiretroviral therapy that patients receive. So far the study has not shown a relationship between HIV infection and any specific type of heart failure. About a quarter of the HIV-infected people who developed heart failure in this study had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, about a quarter had preserved ejection fraction, and for the remaining patients information on their left ventricular ejection fraction was not available, Dr. Go said.

The Kaiser Permanente HIV Heart Study used data from health records from about 13.5 million people enrolled in the health system during 2000-2016 at locations in northern California, southern California, or the mid-Atlantic region. From these records the researchers identified 38,868 people diagnosed with an HIV infection, free of a heart failure diagnosis, and at least 21 years old, and matched them by age, sex, and race with 386,586 people in the health system who were both uninfected and free of heart failure. At “baseline” in the analysis the two study groups had very similar rates of smoking, but those with HIV had somewhat more alcohol abuse and nearly twice the rate of illicit drug use, although even among those with HIV this rate was low at 4%.

Some clinical characteristics at baseline showed significant differences between the two groups. People living with HIV had substantially less hypertension, 7% compared with 12% in those without HIV; half the rate of dyslipidemia, 8% compared with 16% among the control group; and nearly half the prevalence of diabetes, 3% versus 5% among those without HIV. On the other hand, certain other clinical characteristics were more common among those with HIV. The prevalence at baseline of diagnosed dementia was 15% among people infected with HIV and essentially nonexistent (less than 1%) among controls, and the prevalence of diagnosed depression was 8% among people with HIV and 5% among those without the infection.

Baseline parameters also showed that at the time this review first identified a person with HIV and without heart failure in the system records only 18% of the HIV-infected individuals were on an antiretroviral therapy regimen. Dr. Go said that the study is currently analyzing subsequent HIV treatments that these patients may have received. Also at “baseline” 13% of people with documented HIV infection had a CD4 cell count of fewer than 200 cell/mm3, with 4% having fewer than 50 CD4 cells/mm3, and 29% of those with HIV had a blood level of at least 500 copies of HIV RNA/mL. In addition, information on CD4 cell counts was unavailable for 43% of these people, and information on viral load was unavailable for about half.

During “follow-up” in the system’s medical records for a period of up to 17 years, diagnoses of incident heart failure accumulated significantly faster among people with HIV compared to those without HIV. After adjustment for demographic differences, the time of entry into the health system, cardiovascular and other medical differences, and differences in medication use, people living with HIV had a 75% higher rate of incident heart failure compared with those without HIV. Further adjustment based on incident first episodes of acute coronary syndrome during “follow-up” brought the excess rate of heart failure to 66% higher among people infected by HIV, Dr. Go reported. He cautioned that the findings came from a U.S. population that had access to comprehensive health care.

SOURCE: Go AS et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract 2778, THAB0103.

AMSTERDAM –

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“HIV infection is independently associated with a higher risk for developing heart failure, and this excess risk does not appear mediated through atherosclerotic disease pathways or differential use of cardioprotective medications,” Alan S. Go, MD, said at the 22nd International AIDS Conference.

The finding sends two important messages to physicians who care for people living with HIV, Dr. Go said in a video interview. First, have “greater awareness for the risk of heart failure” in people living with HIV, even in those who have excellent [HIV] treatment. Be on the lookout, he recommended, for classic symptoms of heart failure like dyspnea and fatigue, and if found follow-up with an assessment of heart function, usually by echocardiography. The second message is to pay attention to and aggressively treat risk factors for heart failure, such as hypertension, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia, said Dr. Go, director of the Comprehensive Clinical Research Unit of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif.

Results from a small number of prior studies also suggested an increased heart failure rate in people infected with HIV, but those reports had not been able to untangle this observed increase from a possible relationship to the elevated rate of MIs among people living with HIV. The study led by Dr. Go adjusted for acute coronary syndrome events that occurred during follow-up in the analysis and this showed that the increased incidence of heart failure occurred independently of any preceding MI or unstable angina event.

Dr. Go proposed several potential mechanisms that could tie HIV infection to an elevated heart failure risk that was not linked to a prior ischemic heart disease event. The virus could directly damage cardiac myocytes to produce fibrosis, the virus could trigger cardiac inflammation, and the infected person could have an increased susceptibility to infection by a pathogen know to potentially cause cardiac damage and myocarditis such as coxsackievirus.

For the time being, patients infected by HIV who develop heart failure should receive the same treatments that are recommended for the general population, Dr. Go said, but he also highlighted the need for further study to determine the effectiveness of standard heart failure treatments specifically in people living with HIV. He and his associates are also currently analyzing the relationship of several other variables to the risk for heart failure in HIV-infected people, such as the degree of HIV control, and the types of antiretroviral therapy that patients receive. So far the study has not shown a relationship between HIV infection and any specific type of heart failure. About a quarter of the HIV-infected people who developed heart failure in this study had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, about a quarter had preserved ejection fraction, and for the remaining patients information on their left ventricular ejection fraction was not available, Dr. Go said.

The Kaiser Permanente HIV Heart Study used data from health records from about 13.5 million people enrolled in the health system during 2000-2016 at locations in northern California, southern California, or the mid-Atlantic region. From these records the researchers identified 38,868 people diagnosed with an HIV infection, free of a heart failure diagnosis, and at least 21 years old, and matched them by age, sex, and race with 386,586 people in the health system who were both uninfected and free of heart failure. At “baseline” in the analysis the two study groups had very similar rates of smoking, but those with HIV had somewhat more alcohol abuse and nearly twice the rate of illicit drug use, although even among those with HIV this rate was low at 4%.

Some clinical characteristics at baseline showed significant differences between the two groups. People living with HIV had substantially less hypertension, 7% compared with 12% in those without HIV; half the rate of dyslipidemia, 8% compared with 16% among the control group; and nearly half the prevalence of diabetes, 3% versus 5% among those without HIV. On the other hand, certain other clinical characteristics were more common among those with HIV. The prevalence at baseline of diagnosed dementia was 15% among people infected with HIV and essentially nonexistent (less than 1%) among controls, and the prevalence of diagnosed depression was 8% among people with HIV and 5% among those without the infection.

Baseline parameters also showed that at the time this review first identified a person with HIV and without heart failure in the system records only 18% of the HIV-infected individuals were on an antiretroviral therapy regimen. Dr. Go said that the study is currently analyzing subsequent HIV treatments that these patients may have received. Also at “baseline” 13% of people with documented HIV infection had a CD4 cell count of fewer than 200 cell/mm3, with 4% having fewer than 50 CD4 cells/mm3, and 29% of those with HIV had a blood level of at least 500 copies of HIV RNA/mL. In addition, information on CD4 cell counts was unavailable for 43% of these people, and information on viral load was unavailable for about half.

During “follow-up” in the system’s medical records for a period of up to 17 years, diagnoses of incident heart failure accumulated significantly faster among people with HIV compared to those without HIV. After adjustment for demographic differences, the time of entry into the health system, cardiovascular and other medical differences, and differences in medication use, people living with HIV had a 75% higher rate of incident heart failure compared with those without HIV. Further adjustment based on incident first episodes of acute coronary syndrome during “follow-up” brought the excess rate of heart failure to 66% higher among people infected by HIV, Dr. Go reported. He cautioned that the findings came from a U.S. population that had access to comprehensive health care.

SOURCE: Go AS et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract 2778, THAB0103.

AMSTERDAM –

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“HIV infection is independently associated with a higher risk for developing heart failure, and this excess risk does not appear mediated through atherosclerotic disease pathways or differential use of cardioprotective medications,” Alan S. Go, MD, said at the 22nd International AIDS Conference.

The finding sends two important messages to physicians who care for people living with HIV, Dr. Go said in a video interview. First, have “greater awareness for the risk of heart failure” in people living with HIV, even in those who have excellent [HIV] treatment. Be on the lookout, he recommended, for classic symptoms of heart failure like dyspnea and fatigue, and if found follow-up with an assessment of heart function, usually by echocardiography. The second message is to pay attention to and aggressively treat risk factors for heart failure, such as hypertension, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia, said Dr. Go, director of the Comprehensive Clinical Research Unit of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif.

Results from a small number of prior studies also suggested an increased heart failure rate in people infected with HIV, but those reports had not been able to untangle this observed increase from a possible relationship to the elevated rate of MIs among people living with HIV. The study led by Dr. Go adjusted for acute coronary syndrome events that occurred during follow-up in the analysis and this showed that the increased incidence of heart failure occurred independently of any preceding MI or unstable angina event.

Dr. Go proposed several potential mechanisms that could tie HIV infection to an elevated heart failure risk that was not linked to a prior ischemic heart disease event. The virus could directly damage cardiac myocytes to produce fibrosis, the virus could trigger cardiac inflammation, and the infected person could have an increased susceptibility to infection by a pathogen know to potentially cause cardiac damage and myocarditis such as coxsackievirus.

For the time being, patients infected by HIV who develop heart failure should receive the same treatments that are recommended for the general population, Dr. Go said, but he also highlighted the need for further study to determine the effectiveness of standard heart failure treatments specifically in people living with HIV. He and his associates are also currently analyzing the relationship of several other variables to the risk for heart failure in HIV-infected people, such as the degree of HIV control, and the types of antiretroviral therapy that patients receive. So far the study has not shown a relationship between HIV infection and any specific type of heart failure. About a quarter of the HIV-infected people who developed heart failure in this study had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, about a quarter had preserved ejection fraction, and for the remaining patients information on their left ventricular ejection fraction was not available, Dr. Go said.

The Kaiser Permanente HIV Heart Study used data from health records from about 13.5 million people enrolled in the health system during 2000-2016 at locations in northern California, southern California, or the mid-Atlantic region. From these records the researchers identified 38,868 people diagnosed with an HIV infection, free of a heart failure diagnosis, and at least 21 years old, and matched them by age, sex, and race with 386,586 people in the health system who were both uninfected and free of heart failure. At “baseline” in the analysis the two study groups had very similar rates of smoking, but those with HIV had somewhat more alcohol abuse and nearly twice the rate of illicit drug use, although even among those with HIV this rate was low at 4%.

Some clinical characteristics at baseline showed significant differences between the two groups. People living with HIV had substantially less hypertension, 7% compared with 12% in those without HIV; half the rate of dyslipidemia, 8% compared with 16% among the control group; and nearly half the prevalence of diabetes, 3% versus 5% among those without HIV. On the other hand, certain other clinical characteristics were more common among those with HIV. The prevalence at baseline of diagnosed dementia was 15% among people infected with HIV and essentially nonexistent (less than 1%) among controls, and the prevalence of diagnosed depression was 8% among people with HIV and 5% among those without the infection.

Baseline parameters also showed that at the time this review first identified a person with HIV and without heart failure in the system records only 18% of the HIV-infected individuals were on an antiretroviral therapy regimen. Dr. Go said that the study is currently analyzing subsequent HIV treatments that these patients may have received. Also at “baseline” 13% of people with documented HIV infection had a CD4 cell count of fewer than 200 cell/mm3, with 4% having fewer than 50 CD4 cells/mm3, and 29% of those with HIV had a blood level of at least 500 copies of HIV RNA/mL. In addition, information on CD4 cell counts was unavailable for 43% of these people, and information on viral load was unavailable for about half.

During “follow-up” in the system’s medical records for a period of up to 17 years, diagnoses of incident heart failure accumulated significantly faster among people with HIV compared to those without HIV. After adjustment for demographic differences, the time of entry into the health system, cardiovascular and other medical differences, and differences in medication use, people living with HIV had a 75% higher rate of incident heart failure compared with those without HIV. Further adjustment based on incident first episodes of acute coronary syndrome during “follow-up” brought the excess rate of heart failure to 66% higher among people infected by HIV, Dr. Go reported. He cautioned that the findings came from a U.S. population that had access to comprehensive health care.

SOURCE: Go AS et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract 2778, THAB0103.

REPORTING FROM AIDS 2018

Key clinical point: HIV infection may be an independent trigger for heart failure.

Major finding: After extensive adjustment for potential confounders, HIV infection linked with a 66% increased rate of incident heart failure.

Study details: The Kaiser Permanente HIV Heart Study, which included medical records for 425,454 people.

Disclosures: Dr. Go had no disclosures.

Source: Go AS et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract 2778, THAB0103.

Novel HIV vaccine induces durable immune responses

AMSTERDAM – that had identified the most effective dosing strategy for the vaccine.

The 96-week follow-up data showed durable humoral and cellular immunity induction by the vaccine and its associated booster, a durable breadth of immune responses to the multiple HIV clades that the vaccine targets, and no serious or grade 3 or 4 adverse effects in the 393 people who participated in the early-phase study, Frank L. Tomaka, MD, said at the 22nd International AIDS Conference.

The 96-week results he reported came from follow-up of the 393 people who received one of several different dosing regimens for an engineered, mosaic HIV vaccine. The vaccine incorporates genes for three different HIV envelope antigens that contain components drawn from several different HIV clades (to induce more broadly protective immunity) into a serotype 26 adenovirus. The immunization regimen also includes treatment with HIV glycoprotein 140 as a booster agent. Dr. Tomaka and his associates reported the primary endpoints from this placebo-controlled study, APPROACH, measured just after the fourth and final immunizing regimen at 48 weeks after the first treatment in a recently published article (Lancet. 2018 Jul 21;392[10143]:232-43).

As part of the study, the investigators administered the vaccine and booster to rhesus monkeys and found that the regimens produced a pattern of immune responses in the monkeys similar to that seen in people. When the monkeys that received the regimen that performed best in people received six monthly challenges with a simian-human immunodeficiency virus that’s related to HIV, the researchers found a 67% efficacy for protection against infection. These “very encouraging” findings led the company developing the vaccine to launch in November 2017 a phase IIb trial, named Imbokodo, in five African countries, with a plan to enroll 2,600 people, Dr. Tomaka said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“What’s unique and very exciting” about the APPROACH findings are the nonhuman primate findings, and the fact that the vaccine was designed to provide protection against several different HIV clades, Dr. Tomaka said in a video interview. The 67% level of protection against viral challenge in the monkeys is at a level that would be clinically meaningful if replicated in people. A vaccine and booster regimen that provided something in the range of 50%-60% protection or better might be an attractive option in a region with relatively low resources, while in a more developed country a vaccine with a protective efficacy of 70% or better would also likely be seen as an attractive intervention, said Dr. Tomaka, clinical leader for HIV/STI vaccines for Janssen in Titusville, N.J.

SOURCE: Tomaka FL et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract TUAA0104.

The 1-year results for this new HIV vaccine and now the 1-year follow-up results appear very promising for its future prospects in wider clinical testing.

What’s especially interesting about the data reported for this vaccine so far is that the developers also tested the vaccine in rhesus monkeys and showed similar immunologic induction and a 67% efficacy for protecting against repeated challenges with a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. This level of protection against infection and the similar cellular and antibody responses to the vaccine and booster in the animal model and in people is encouraging. The vaccine protected monkeys. Now we need to find out whether it will protect humans.

R. Brad Jones, PhD , is an immunologist at Cornell University, New York. He had no disclosures. He made these comments during a talk at the conference.

The 1-year results for this new HIV vaccine and now the 1-year follow-up results appear very promising for its future prospects in wider clinical testing.

What’s especially interesting about the data reported for this vaccine so far is that the developers also tested the vaccine in rhesus monkeys and showed similar immunologic induction and a 67% efficacy for protecting against repeated challenges with a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. This level of protection against infection and the similar cellular and antibody responses to the vaccine and booster in the animal model and in people is encouraging. The vaccine protected monkeys. Now we need to find out whether it will protect humans.

R. Brad Jones, PhD , is an immunologist at Cornell University, New York. He had no disclosures. He made these comments during a talk at the conference.

The 1-year results for this new HIV vaccine and now the 1-year follow-up results appear very promising for its future prospects in wider clinical testing.

What’s especially interesting about the data reported for this vaccine so far is that the developers also tested the vaccine in rhesus monkeys and showed similar immunologic induction and a 67% efficacy for protecting against repeated challenges with a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. This level of protection against infection and the similar cellular and antibody responses to the vaccine and booster in the animal model and in people is encouraging. The vaccine protected monkeys. Now we need to find out whether it will protect humans.

R. Brad Jones, PhD , is an immunologist at Cornell University, New York. He had no disclosures. He made these comments during a talk at the conference.

AMSTERDAM – that had identified the most effective dosing strategy for the vaccine.

The 96-week follow-up data showed durable humoral and cellular immunity induction by the vaccine and its associated booster, a durable breadth of immune responses to the multiple HIV clades that the vaccine targets, and no serious or grade 3 or 4 adverse effects in the 393 people who participated in the early-phase study, Frank L. Tomaka, MD, said at the 22nd International AIDS Conference.

The 96-week results he reported came from follow-up of the 393 people who received one of several different dosing regimens for an engineered, mosaic HIV vaccine. The vaccine incorporates genes for three different HIV envelope antigens that contain components drawn from several different HIV clades (to induce more broadly protective immunity) into a serotype 26 adenovirus. The immunization regimen also includes treatment with HIV glycoprotein 140 as a booster agent. Dr. Tomaka and his associates reported the primary endpoints from this placebo-controlled study, APPROACH, measured just after the fourth and final immunizing regimen at 48 weeks after the first treatment in a recently published article (Lancet. 2018 Jul 21;392[10143]:232-43).

As part of the study, the investigators administered the vaccine and booster to rhesus monkeys and found that the regimens produced a pattern of immune responses in the monkeys similar to that seen in people. When the monkeys that received the regimen that performed best in people received six monthly challenges with a simian-human immunodeficiency virus that’s related to HIV, the researchers found a 67% efficacy for protection against infection. These “very encouraging” findings led the company developing the vaccine to launch in November 2017 a phase IIb trial, named Imbokodo, in five African countries, with a plan to enroll 2,600 people, Dr. Tomaka said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“What’s unique and very exciting” about the APPROACH findings are the nonhuman primate findings, and the fact that the vaccine was designed to provide protection against several different HIV clades, Dr. Tomaka said in a video interview. The 67% level of protection against viral challenge in the monkeys is at a level that would be clinically meaningful if replicated in people. A vaccine and booster regimen that provided something in the range of 50%-60% protection or better might be an attractive option in a region with relatively low resources, while in a more developed country a vaccine with a protective efficacy of 70% or better would also likely be seen as an attractive intervention, said Dr. Tomaka, clinical leader for HIV/STI vaccines for Janssen in Titusville, N.J.

SOURCE: Tomaka FL et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract TUAA0104.

AMSTERDAM – that had identified the most effective dosing strategy for the vaccine.

The 96-week follow-up data showed durable humoral and cellular immunity induction by the vaccine and its associated booster, a durable breadth of immune responses to the multiple HIV clades that the vaccine targets, and no serious or grade 3 or 4 adverse effects in the 393 people who participated in the early-phase study, Frank L. Tomaka, MD, said at the 22nd International AIDS Conference.

The 96-week results he reported came from follow-up of the 393 people who received one of several different dosing regimens for an engineered, mosaic HIV vaccine. The vaccine incorporates genes for three different HIV envelope antigens that contain components drawn from several different HIV clades (to induce more broadly protective immunity) into a serotype 26 adenovirus. The immunization regimen also includes treatment with HIV glycoprotein 140 as a booster agent. Dr. Tomaka and his associates reported the primary endpoints from this placebo-controlled study, APPROACH, measured just after the fourth and final immunizing regimen at 48 weeks after the first treatment in a recently published article (Lancet. 2018 Jul 21;392[10143]:232-43).

As part of the study, the investigators administered the vaccine and booster to rhesus monkeys and found that the regimens produced a pattern of immune responses in the monkeys similar to that seen in people. When the monkeys that received the regimen that performed best in people received six monthly challenges with a simian-human immunodeficiency virus that’s related to HIV, the researchers found a 67% efficacy for protection against infection. These “very encouraging” findings led the company developing the vaccine to launch in November 2017 a phase IIb trial, named Imbokodo, in five African countries, with a plan to enroll 2,600 people, Dr. Tomaka said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“What’s unique and very exciting” about the APPROACH findings are the nonhuman primate findings, and the fact that the vaccine was designed to provide protection against several different HIV clades, Dr. Tomaka said in a video interview. The 67% level of protection against viral challenge in the monkeys is at a level that would be clinically meaningful if replicated in people. A vaccine and booster regimen that provided something in the range of 50%-60% protection or better might be an attractive option in a region with relatively low resources, while in a more developed country a vaccine with a protective efficacy of 70% or better would also likely be seen as an attractive intervention, said Dr. Tomaka, clinical leader for HIV/STI vaccines for Janssen in Titusville, N.J.

SOURCE: Tomaka FL et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract TUAA0104.

REPORTING FROM AIDS 2018

Key clinical point: An investigational HIV vaccine and booster showed durable safety and anti-HIV immune effects.

Major finding: One year follow-up after the final dosage showed no serious or grade 3 or 4 adverse effects and durable immune responses.

Study details: The APPROACH study, a phase I/IIa study with 393 participants.

Disclosures: APPROACH was sponsored by Janssen, the company developing the vaccine. Dr. Tomaka is a Janssen employee.

Source: Tomaka FL et al. AIDS 2018, Abstract TUAA0104.

VIDEO: Look for Signs of Depression in Rosacea Patients

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Special care advised for HIV-infected patients with diabetes

ORLANDO – Research suggests that HIV-positive people who take the latest generations of AIDS medications are living almost as long as everyone else. But they still face special medical challenges, and an endocrinologist urged colleagues to adjust their approaches to diabetes in these patients.

said Todd T. Brown, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, in a presentation at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

It’s not just a matter of subbing in an alternate drug here or there. When it comes to diabetes, patients with HIV require significant adjustments to diagnosis and treatment, Dr. Brown said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

In terms of diagnosis, treatment guidelines approved by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and ADA recommend that all HIV-positive patients be tested for diabetes before they begin taking antiretroviral therapy. Then, the guidelines suggest, they should be tested 4-6 weeks after initiation of therapy, and every 6-12 months going forward.

“It’s a bit of overkill to go every 6 months,” said Dr. Brown, who prefers an annual testing approach. He added that research has suggested that the 2-hour postload glucose test is more sensitive than the fasting glucose test in some HIV-positive populations. However, he believes that it’s generally fine to give a fasting glucose test before initiation of therapy – and on an annual basis afterward – rather than the more cumbersome postload test.

Still, he said, the postload test may be appropriate in a patient with impaired glucose tolerance “if you really want to make the diagnosis, and especially if you’ll change your treatment based on it.”

Ongoing treatment of HIV-positive patients also presents unique challenges, he said. For one, antiretroviral therapy seems to affect glucose metabolism and body fat, he said, and findings from a 2016 study suggest HIV-positive people who begin antiretroviral therapy face a higher risk of developing diabetes after weight gain (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016 Oct 1;73[2]:228-36).

One option is to switch patients to integrase inhibitors, but findings from a 2017 study suggested that this may also lead to more weight gain, Dr. Brown said.

“This has been an evolving story,” he said. “The clinical consequences of this are unclear. This is a topic that’s being hotly investigated now in the HIV health world” (JAIDS. 2017 Dec 15;76[5]:527-31).

As for other diabetes management issues, Dr. Brown noted that hemoglobin A1c tests appear to underestimate glycemia in HIV-infected patients. He suggested that goal HbA1c levels should be lower in diabetic patients with HIV, especially those with CD4+ counts under 500 cells /mm3 and/or mean cell volume over 100 fL.

Research suggests that lifestyle changes seem to work well in HIV-positive patients, he said, and metformin is the ideal first-line drug treatment just as in the HIV-negative population. “It’s a good drug. We all love it,” he said. “It may improve lipohypertrophy and coronary plaque.”

He added that proteinuria and neuropathy are more common in HIV-positive patients with diabetes. He said levels of neuropathy and nephropathy could be related to AIDS drugs.

On the medication front, Dr. Brown cautioned about certain drugs in HIV-positive patients: The HIV drug dolutegravir increases metformin concentrations by about 80%, he said, and there are concerns about bone and cardiac health in HIV-positive patients who take the diabetes medications known as thiazolidinediones (glitazones).

He added that there are sparse data about the use of several types of diabetes drugs – DPP IV inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors – in HIV-positive patients.

Dr. Brown discloses consulting for Gilead Sciences, ViiV, BMS, Merck, Theratechnologies, and EMD Serono.

ORLANDO – Research suggests that HIV-positive people who take the latest generations of AIDS medications are living almost as long as everyone else. But they still face special medical challenges, and an endocrinologist urged colleagues to adjust their approaches to diabetes in these patients.

said Todd T. Brown, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, in a presentation at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

It’s not just a matter of subbing in an alternate drug here or there. When it comes to diabetes, patients with HIV require significant adjustments to diagnosis and treatment, Dr. Brown said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

In terms of diagnosis, treatment guidelines approved by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and ADA recommend that all HIV-positive patients be tested for diabetes before they begin taking antiretroviral therapy. Then, the guidelines suggest, they should be tested 4-6 weeks after initiation of therapy, and every 6-12 months going forward.

“It’s a bit of overkill to go every 6 months,” said Dr. Brown, who prefers an annual testing approach. He added that research has suggested that the 2-hour postload glucose test is more sensitive than the fasting glucose test in some HIV-positive populations. However, he believes that it’s generally fine to give a fasting glucose test before initiation of therapy – and on an annual basis afterward – rather than the more cumbersome postload test.

Still, he said, the postload test may be appropriate in a patient with impaired glucose tolerance “if you really want to make the diagnosis, and especially if you’ll change your treatment based on it.”

Ongoing treatment of HIV-positive patients also presents unique challenges, he said. For one, antiretroviral therapy seems to affect glucose metabolism and body fat, he said, and findings from a 2016 study suggest HIV-positive people who begin antiretroviral therapy face a higher risk of developing diabetes after weight gain (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016 Oct 1;73[2]:228-36).

One option is to switch patients to integrase inhibitors, but findings from a 2017 study suggested that this may also lead to more weight gain, Dr. Brown said.

“This has been an evolving story,” he said. “The clinical consequences of this are unclear. This is a topic that’s being hotly investigated now in the HIV health world” (JAIDS. 2017 Dec 15;76[5]:527-31).

As for other diabetes management issues, Dr. Brown noted that hemoglobin A1c tests appear to underestimate glycemia in HIV-infected patients. He suggested that goal HbA1c levels should be lower in diabetic patients with HIV, especially those with CD4+ counts under 500 cells /mm3 and/or mean cell volume over 100 fL.

Research suggests that lifestyle changes seem to work well in HIV-positive patients, he said, and metformin is the ideal first-line drug treatment just as in the HIV-negative population. “It’s a good drug. We all love it,” he said. “It may improve lipohypertrophy and coronary plaque.”

He added that proteinuria and neuropathy are more common in HIV-positive patients with diabetes. He said levels of neuropathy and nephropathy could be related to AIDS drugs.

On the medication front, Dr. Brown cautioned about certain drugs in HIV-positive patients: The HIV drug dolutegravir increases metformin concentrations by about 80%, he said, and there are concerns about bone and cardiac health in HIV-positive patients who take the diabetes medications known as thiazolidinediones (glitazones).

He added that there are sparse data about the use of several types of diabetes drugs – DPP IV inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors – in HIV-positive patients.

Dr. Brown discloses consulting for Gilead Sciences, ViiV, BMS, Merck, Theratechnologies, and EMD Serono.

ORLANDO – Research suggests that HIV-positive people who take the latest generations of AIDS medications are living almost as long as everyone else. But they still face special medical challenges, and an endocrinologist urged colleagues to adjust their approaches to diabetes in these patients.

said Todd T. Brown, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, in a presentation at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

It’s not just a matter of subbing in an alternate drug here or there. When it comes to diabetes, patients with HIV require significant adjustments to diagnosis and treatment, Dr. Brown said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

In terms of diagnosis, treatment guidelines approved by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and ADA recommend that all HIV-positive patients be tested for diabetes before they begin taking antiretroviral therapy. Then, the guidelines suggest, they should be tested 4-6 weeks after initiation of therapy, and every 6-12 months going forward.

“It’s a bit of overkill to go every 6 months,” said Dr. Brown, who prefers an annual testing approach. He added that research has suggested that the 2-hour postload glucose test is more sensitive than the fasting glucose test in some HIV-positive populations. However, he believes that it’s generally fine to give a fasting glucose test before initiation of therapy – and on an annual basis afterward – rather than the more cumbersome postload test.

Still, he said, the postload test may be appropriate in a patient with impaired glucose tolerance “if you really want to make the diagnosis, and especially if you’ll change your treatment based on it.”

Ongoing treatment of HIV-positive patients also presents unique challenges, he said. For one, antiretroviral therapy seems to affect glucose metabolism and body fat, he said, and findings from a 2016 study suggest HIV-positive people who begin antiretroviral therapy face a higher risk of developing diabetes after weight gain (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016 Oct 1;73[2]:228-36).

One option is to switch patients to integrase inhibitors, but findings from a 2017 study suggested that this may also lead to more weight gain, Dr. Brown said.

“This has been an evolving story,” he said. “The clinical consequences of this are unclear. This is a topic that’s being hotly investigated now in the HIV health world” (JAIDS. 2017 Dec 15;76[5]:527-31).

As for other diabetes management issues, Dr. Brown noted that hemoglobin A1c tests appear to underestimate glycemia in HIV-infected patients. He suggested that goal HbA1c levels should be lower in diabetic patients with HIV, especially those with CD4+ counts under 500 cells /mm3 and/or mean cell volume over 100 fL.

Research suggests that lifestyle changes seem to work well in HIV-positive patients, he said, and metformin is the ideal first-line drug treatment just as in the HIV-negative population. “It’s a good drug. We all love it,” he said. “It may improve lipohypertrophy and coronary plaque.”

He added that proteinuria and neuropathy are more common in HIV-positive patients with diabetes. He said levels of neuropathy and nephropathy could be related to AIDS drugs.

On the medication front, Dr. Brown cautioned about certain drugs in HIV-positive patients: The HIV drug dolutegravir increases metformin concentrations by about 80%, he said, and there are concerns about bone and cardiac health in HIV-positive patients who take the diabetes medications known as thiazolidinediones (glitazones).

He added that there are sparse data about the use of several types of diabetes drugs – DPP IV inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors – in HIV-positive patients.

Dr. Brown discloses consulting for Gilead Sciences, ViiV, BMS, Merck, Theratechnologies, and EMD Serono.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ADA 2018