User login

Dyspnea and intercostal retractions

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults. Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults. Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults. Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 17-year-old boy came to the hospital with shortness of breath and loud wheezing. His mother explained that earlier that day, he visited a friend’s house where they played video games together in the basement. When he returned home, he noticed that he was becoming breathless while talking. His chest radiograph findings were normal, but intercostal retractions were observed. His heart rate is 120 beats/minute.

Question 1

Correct answer: D. Antienterocyte antibodies

Rationale

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is characterized by a severe malabsorption and secretory diarrhea, and is differentiated from celiac disease on small-bowel biopsy by the decreased numbers or absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, apoptotic bodies present in the intestinal crypts, and absent goblet and Paneth cells. Patients with AIE may also carry other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. A group at the Mayo Clinic has published a set of diagnostic criteria based on their case series of adult AIE that requires ruling out other causes of chronic diarrhea in adults, specific histology supportive of AIE, and presence of malabsorption and ruling out other causes of villous atrophy. The presence of antienterocyte or antigoblet cell antibodies are supportive of a diagnosis of AIE, but their absence does not exclude the diagnosis.

References

Akram S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1282-90.

Montalto M et al. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(9):1029-36.

Correct answer: D. Antienterocyte antibodies

Rationale

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is characterized by a severe malabsorption and secretory diarrhea, and is differentiated from celiac disease on small-bowel biopsy by the decreased numbers or absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, apoptotic bodies present in the intestinal crypts, and absent goblet and Paneth cells. Patients with AIE may also carry other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. A group at the Mayo Clinic has published a set of diagnostic criteria based on their case series of adult AIE that requires ruling out other causes of chronic diarrhea in adults, specific histology supportive of AIE, and presence of malabsorption and ruling out other causes of villous atrophy. The presence of antienterocyte or antigoblet cell antibodies are supportive of a diagnosis of AIE, but their absence does not exclude the diagnosis.

References

Akram S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1282-90.

Montalto M et al. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(9):1029-36.

Correct answer: D. Antienterocyte antibodies

Rationale

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is characterized by a severe malabsorption and secretory diarrhea, and is differentiated from celiac disease on small-bowel biopsy by the decreased numbers or absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, apoptotic bodies present in the intestinal crypts, and absent goblet and Paneth cells. Patients with AIE may also carry other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. A group at the Mayo Clinic has published a set of diagnostic criteria based on their case series of adult AIE that requires ruling out other causes of chronic diarrhea in adults, specific histology supportive of AIE, and presence of malabsorption and ruling out other causes of villous atrophy. The presence of antienterocyte or antigoblet cell antibodies are supportive of a diagnosis of AIE, but their absence does not exclude the diagnosis.

References

Akram S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1282-90.

Montalto M et al. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(9):1029-36.

Q1. A 55-year-old woman presents with a one-year history of large volume foul-smelling stools that float in water associated with 40-pound weight loss. Laboratory evaluation reveals low vitamin A and D levels. An upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies reveals complete villous blunting with decreased goblet and Paneth cells, absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, and increased crypt apoptosis. She denies nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, celiac serologies were not elevated, and a glucose hydrogen breath test was negative. She also has coexisting rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

Have you used ambulatory cervical ripening in your practice?

[polldaddy:10771173]

[polldaddy:10771173]

[polldaddy:10771173]

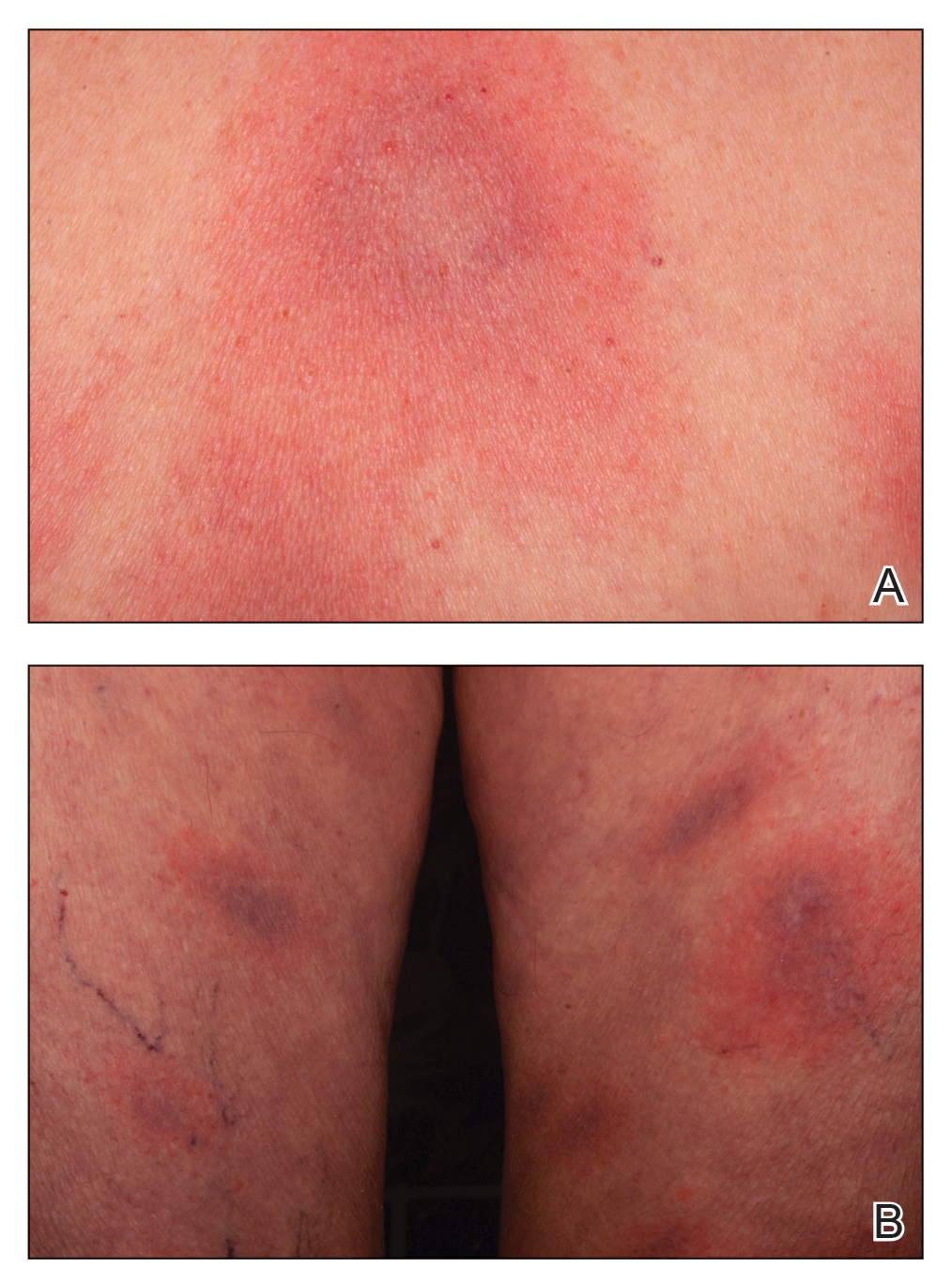

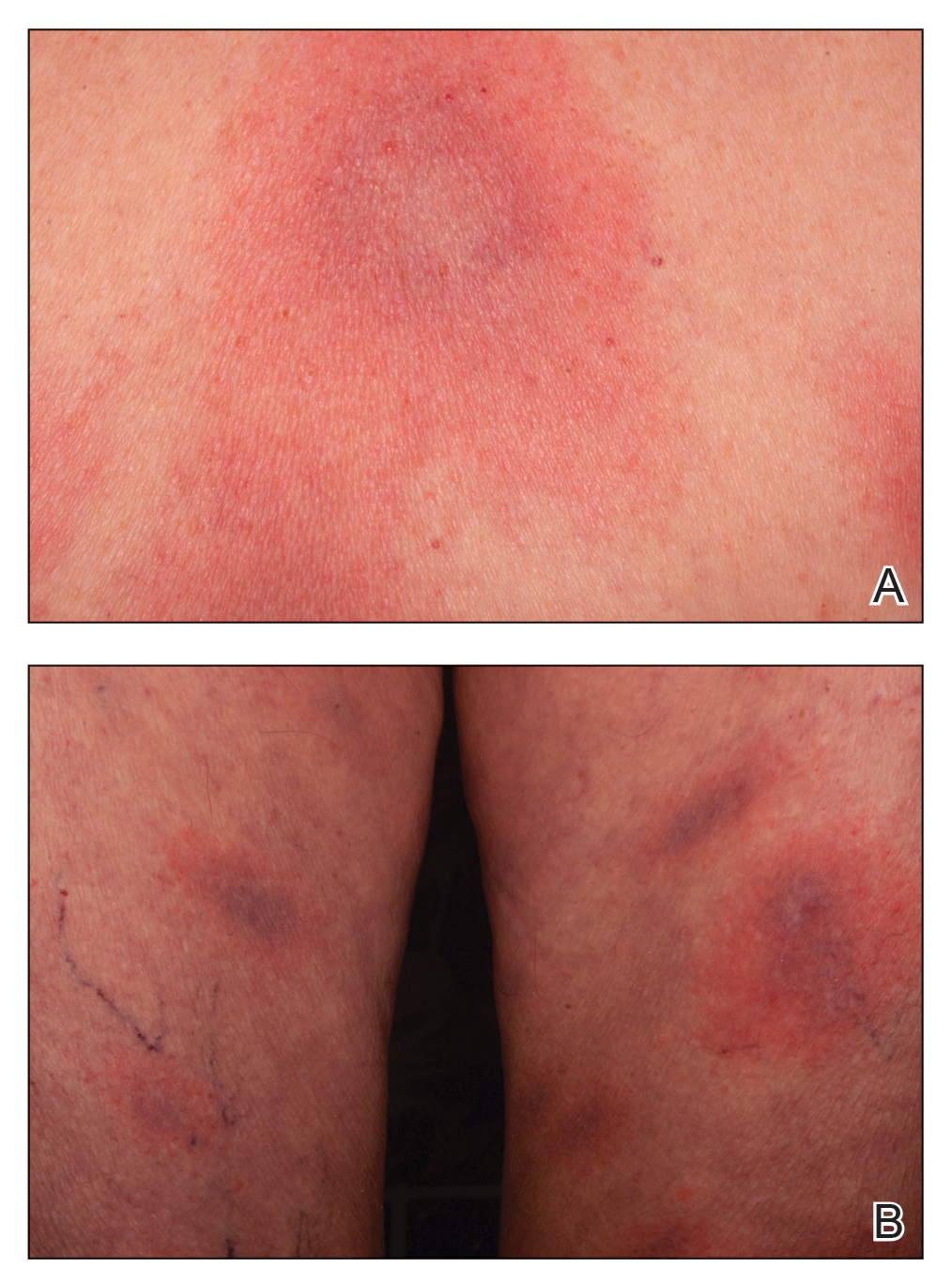

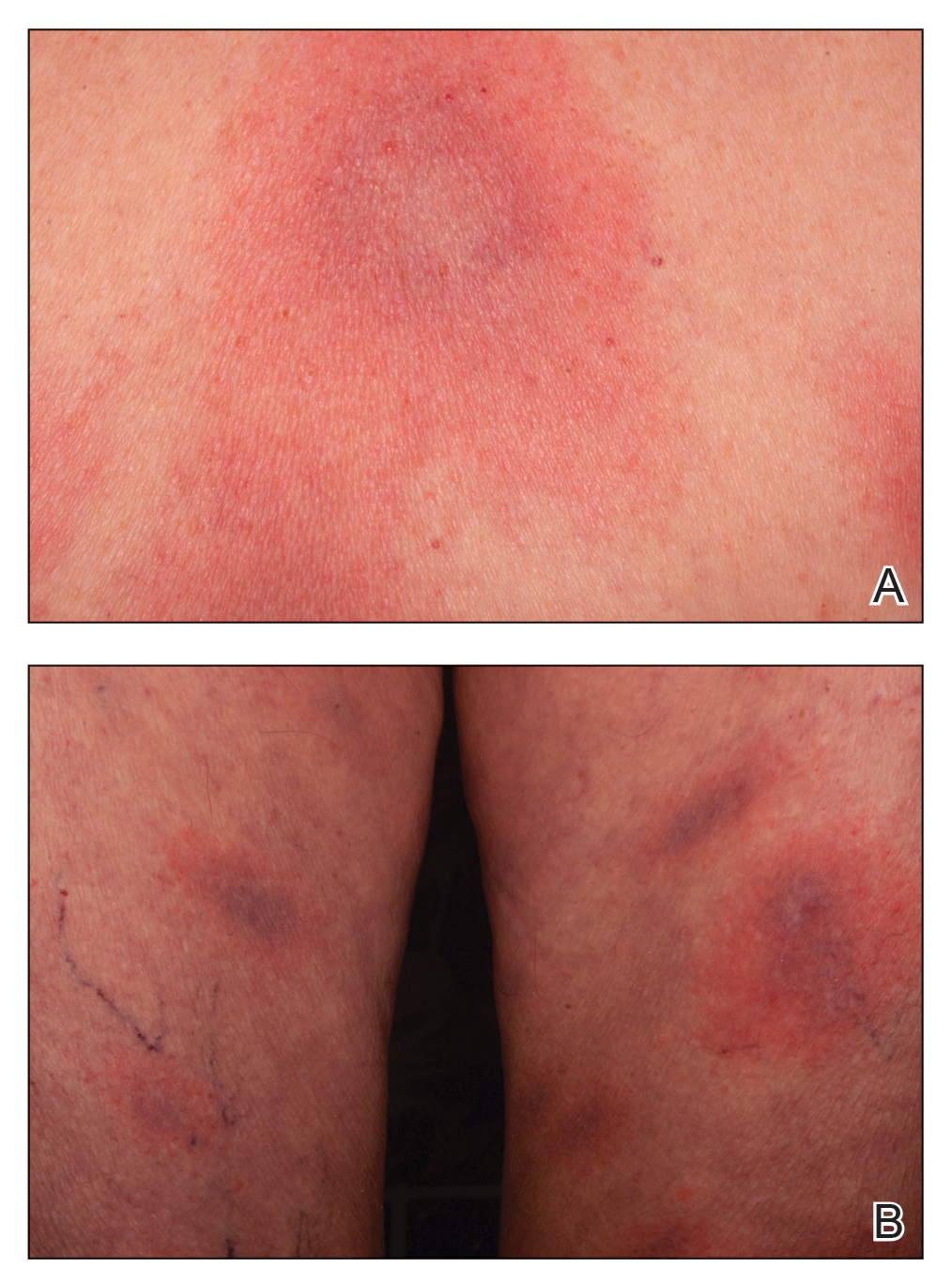

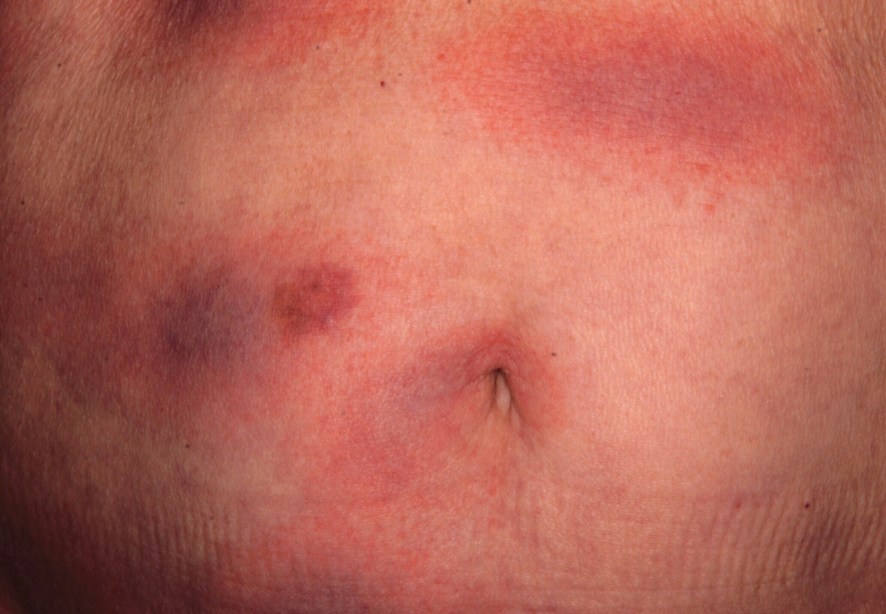

Multifocal Annular Pink Plaques With a Central Violaceous Hue

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

An otherwise healthy 78-year-old woman presented with a diffuse, mildly itchy rash of 5 days’ duration with associated fatigue, chills, decreased appetite, and nausea. She reported waking up with her arms “feeling like they weigh a ton.” She denied any pain, bleeding, or oozing and was unsure if new spots were continuing to develop. The patient reported having allergies to numerous medications but denied any new medications or recent illnesses. She had recently spent time on a farm in Minnesota, and upon further questioning she recalled a tick bite 2 months prior to presentation. She stated that she removed the nonengorged tick and that it could not have been attached for more than 24 hours. Her medical and family history were unremarkable. Physical examination showed multiple annular pink plaques with a central violaceous hue in a generalized distribution involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs with mild erythema of the palms. The plantar surfaces were clear, and there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the physical examination and review of systems was negative. Laboratory screening was notable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level with negative antinuclear antibodies.

The ASCCP now recommends that clinicians routinely exposed to HPVs consider 9vHPV vaccination. Will you get this vaccine?

[polldaddy:10665862]

[polldaddy:10665862]

[polldaddy:10665862]

DDSEP® 9 Quick Quiz

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

Episodic hepatic encephalopathy is usually precipitant-induced in over 80% of cases and includes dehydration, infections, over diuresis, gastrointestinal bleeding, constipation, and the use of narcotics and sedatives. Key is to identify and treat the precipitant. A diagnostic workup to rule out other disorders that can alter brain function and mimic hepatic encephalopathy should also be performed.

Reference

1. Viltstrup H et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-35.

[email protected]

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

Episodic hepatic encephalopathy is usually precipitant-induced in over 80% of cases and includes dehydration, infections, over diuresis, gastrointestinal bleeding, constipation, and the use of narcotics and sedatives. Key is to identify and treat the precipitant. A diagnostic workup to rule out other disorders that can alter brain function and mimic hepatic encephalopathy should also be performed.

Reference

1. Viltstrup H et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-35.

[email protected]

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

Episodic hepatic encephalopathy is usually precipitant-induced in over 80% of cases and includes dehydration, infections, over diuresis, gastrointestinal bleeding, constipation, and the use of narcotics and sedatives. Key is to identify and treat the precipitant. A diagnostic workup to rule out other disorders that can alter brain function and mimic hepatic encephalopathy should also be performed.

Reference

1. Viltstrup H et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-35.

[email protected]

A 62-year-old man with hepatitis C cirrhosis is admitted with altered mental status. He had a recent dental procedure and was given pain medication and a short course of antibiotics. He is only taking spironolactone 50 mg for small ascites. Patient is alert but not oriented to place and time. He has evidence of asterixis. His mucous membranes are dry and he has no evidence of ascites on exam. His labs include WBC, 4.7 × 103 mm3; AST, 45 U/L; ALT, 40 U/L; total bilirubin of 2.5 mg/dL; albumin of 3.7 g/dL; sodium 142 mEq/L; and a creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL.

DDSEP® 9 Quick Quiz

Q1. Correct answer: A

Rationale

In the United States, pigmented stones (black and brown) are less common than cholesterol gallstones. Both types of pigmented stones contain an excess of unconjugated bilirubin and are composed of calcium hydrogen bilirubinate, which is oxidized and polymerized in the hard black stones but unpolymerized in softer brown stones. Black pigmented gallstones are frequently radiopaque and form in sterile bile. Risk factors for black pigmented stones include hemolysis (example, sickle cell disease), cirrhosis, cystic fibrosis, and diseases affecting the ileum (example, Crohn's disease). In contrast, brown stones are more likely to occur in the bile ducts, are radiolucent, and form secondary to biliary stasis (example, biliary stricture) and infection (example, Clonorchis sinensis).

Obesity, female sex, and hyperlipidemia are risk factors for cholesterol gallstone formation. Octreotide decreases gallbladder motility and long-term use can increase the risk of cholelithiasis.

References

1. Stinton LM, Myers RP, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2010;39:157-69.

2. Vitek L, Carey MC. New pathophysiological concepts underlying pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:122-9.

Q1. Correct answer: A

Rationale

In the United States, pigmented stones (black and brown) are less common than cholesterol gallstones. Both types of pigmented stones contain an excess of unconjugated bilirubin and are composed of calcium hydrogen bilirubinate, which is oxidized and polymerized in the hard black stones but unpolymerized in softer brown stones. Black pigmented gallstones are frequently radiopaque and form in sterile bile. Risk factors for black pigmented stones include hemolysis (example, sickle cell disease), cirrhosis, cystic fibrosis, and diseases affecting the ileum (example, Crohn's disease). In contrast, brown stones are more likely to occur in the bile ducts, are radiolucent, and form secondary to biliary stasis (example, biliary stricture) and infection (example, Clonorchis sinensis).

Obesity, female sex, and hyperlipidemia are risk factors for cholesterol gallstone formation. Octreotide decreases gallbladder motility and long-term use can increase the risk of cholelithiasis.

References

1. Stinton LM, Myers RP, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2010;39:157-69.

2. Vitek L, Carey MC. New pathophysiological concepts underlying pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:122-9.

Q1. Correct answer: A

Rationale

In the United States, pigmented stones (black and brown) are less common than cholesterol gallstones. Both types of pigmented stones contain an excess of unconjugated bilirubin and are composed of calcium hydrogen bilirubinate, which is oxidized and polymerized in the hard black stones but unpolymerized in softer brown stones. Black pigmented gallstones are frequently radiopaque and form in sterile bile. Risk factors for black pigmented stones include hemolysis (example, sickle cell disease), cirrhosis, cystic fibrosis, and diseases affecting the ileum (example, Crohn's disease). In contrast, brown stones are more likely to occur in the bile ducts, are radiolucent, and form secondary to biliary stasis (example, biliary stricture) and infection (example, Clonorchis sinensis).

Obesity, female sex, and hyperlipidemia are risk factors for cholesterol gallstone formation. Octreotide decreases gallbladder motility and long-term use can increase the risk of cholelithiasis.

References

1. Stinton LM, Myers RP, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2010;39:157-69.

2. Vitek L, Carey MC. New pathophysiological concepts underlying pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:122-9.

A 56-year-old woman presents for evaluation of right upper-quadrant pain. Her medical history is remarkable for obesity with a BMI of 31 kg/m2, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, NASH cirrhosis, and a recent admission for melena. During her prior admission, she was treated with a proton pump inhibitor and octreotide. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a gastric ulcer with signs of recent bleeding and small esophageal varices without red wale signs.

Her lab evaluation is as follows: AST, 69 U/L; ALT, 35 U/L; total bilirubin, 1.6 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 121 U/L, leukocytes 7,500/microL. An abdominal ultrasound is notable for a positive sonographic Murphy's sign, cholelithiasis, an 8-mm gallbladder wall, normal appearing bile ducts, and a cirrhotic appearing liver with splenomegaly. She undergoes cholecystectomy. Examination of the gallbladder reveals numerous hard gallstones, which are predominately composed of calcium bilirubinate.

Poll: Institutions should implement mandatory implicit bias training and policies for inclusion and diversity to address inequities in health care

[polldaddy:10586792]

[polldaddy:10586792]

[polldaddy:10586792]

Should the practice of counseling patients to present to the office for a string check after IUD insertion be halted?

[polldaddy:10527068]

[polldaddy:10527068]

[polldaddy:10527068]