User login

Papular Eruption Following Excessive Tanning Bed Use

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

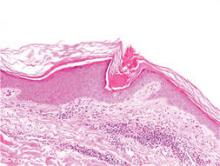

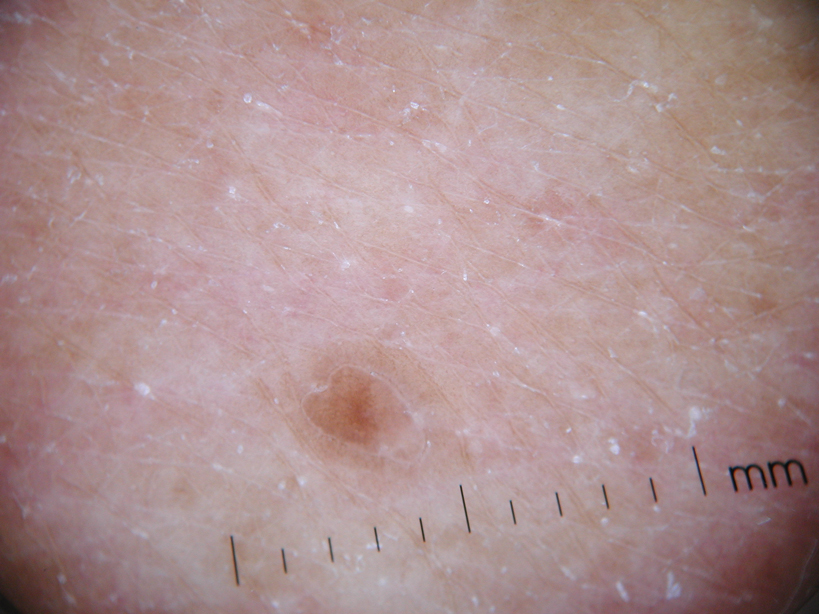

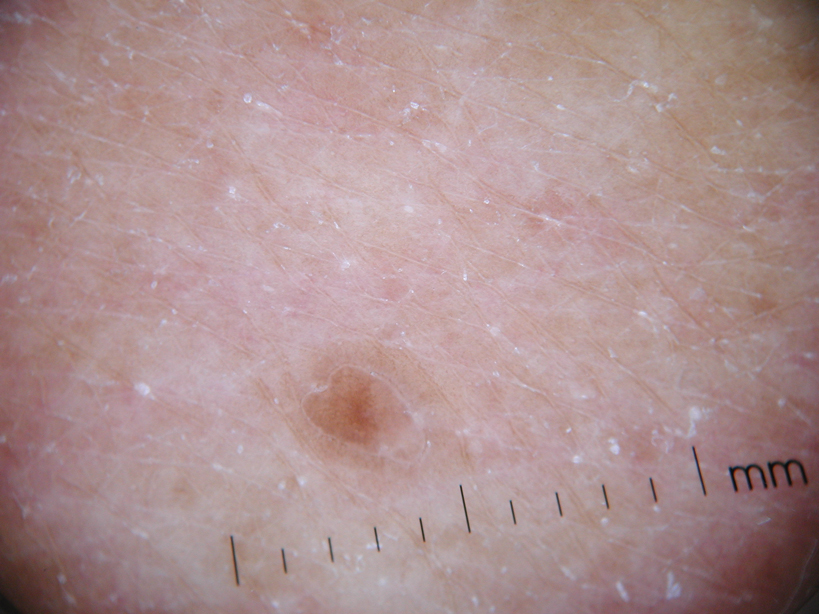

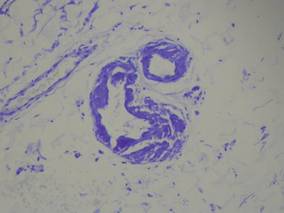

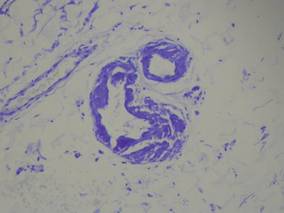

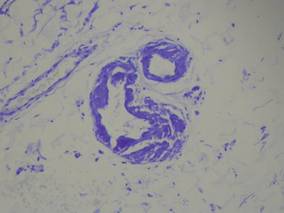

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

A 78-year-old man with Fitzpatrick skin type III presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of a pruritic, erythematous, papular eruption on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs of 5 years’ duration. His medications include clonazepam, lisinopril, allopurinol, omeprazole, tramadol, and mirtazapine. The lesions did not respond to topical corticosteroids; however, the pruritus improved with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments. Review of systems did not reveal any abnormalities. The patient’s medical history included gout, hypertension, anxiety, esophageal stricture, and emphysema. He reported a history of tanning salon use at least 3 times weekly for 7 years. After initial consultation, the patient was treated with clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% twice daily and hydroxyzine 10 mg 3 times daily. Following 1 month of treatment, the eruption did not improve. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left upper arm revealed a dense infiltrate in the upper dermis with prominent parakeratosis, lymphocytes, and numerous eosinophils, suggestive of a drug eruption. As a result, allopurinol was discontinued as a causative agent; however, the eruption presented prior to taking allopurinol. Because the patient experienced intense pruritus, he was started on NB-UVB treatments. After 14 treatments of NB-UVB 3 times weekly, the patient noticed some improvement with respect to pruritus, but the lesions did not resolve. A complete blood cell count indicated 7.6% eosinophils (reference range, 0%–5%). Liver function tests, complete metabolic profile, and renal function were within reference range. Lisinopril was then discontinued as a likely culprit for persistent drug eruption; however, new lesions continued to develop.

“Something Abnormal” on a Chest X-ray

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a fairly large (4 x 6 cm) right paratracheal mass of unclear etiology. This type of finding warrants further evaluation with contrasted CT.

Fortunately for this patient, a subsequent study demonstrated a slightly enlarged thyroid gland. This correlated with the radiographic

finding.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a fairly large (4 x 6 cm) right paratracheal mass of unclear etiology. This type of finding warrants further evaluation with contrasted CT.

Fortunately for this patient, a subsequent study demonstrated a slightly enlarged thyroid gland. This correlated with the radiographic

finding.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a fairly large (4 x 6 cm) right paratracheal mass of unclear etiology. This type of finding warrants further evaluation with contrasted CT.

Fortunately for this patient, a subsequent study demonstrated a slightly enlarged thyroid gland. This correlated with the radiographic

finding.

You are doing preoperative orders on a patient scheduled for surgery tomorrow morning. The patient is a 75-year-old woman who was admitted with an acute left subdural hematoma after sustaining a ground-level fall. Her medical history is significant for hypertension and diabetes. Social history is unremarkable. She is neurologically intact except for occasional confusion and aphasia. She moves all her extremities well. As you review her lab results, one of the nurses mentions that the radiology department called about “something abnormal” on the patient’s chest radiograph. You pull up the patient’s portable chest radiograph on the computer to review. What is your impression?

Itchy Lesion Heralds Pervasive Problem

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (choice “b”), a common and very distinctive eruption related to human herpesvirus 6 and 7.

Allergic reaction to methotrexate (choice “a”), while far from unknown, does not resemble pityriasis rosea. It also would not be limited to such a relatively small area.

Pityriasis rosea is often designated as “fungal infection” (choice “c”) by the uninitiated. However, the lesions of dermatophytosis would be round, with a leading scaly edge, and unlikely to be found in this distribution.

Secondary syphilis (choice “d”) is a major item in the pityriasis rosea differential, but it almost always involves the palms and soles and the lesions would be round (not oval) scaly brown papules. Furthermore, assuming we have an honest patient, we’re also missing a source for sexually transmitted infection.

DISCUSSION

One could hardly ask for a more classic case of pityriasis rosea (PR), which primarily affects patients ages 14 to 40. Alas, that being said, one cannot depend on seeing all these clues in every PR patient.

For example, the herald patch (also known as the mother patch) is missing in at least half of cases. In others, the lesions are smaller, sparser, and more papular (especially in young black patients). The condition may even be confined to intertriginous areas (eg, the groin and/or axillae); this is known as inverse PR.

While salmon-colored scaly lesions are considered a classic presentation, PR can present with darker ovoid macules that have minimal scale and, rarely, become bullous. Involvement above the neck is rare.

What is consistent and dependable among signs of PR is the centripetal scale, seen even in the smallest lesions. This scale is so fine that the old dermatology texts called it “cigarette paper” scale or “scurf.”

After decades of speculation, researchers finally provided strong evidence of the probable cause of PR: replication of human herpesvirus 6 and 7, present in mono-

nuclear cells of lesional skin. Though universally acquired in childhood, these viruses are thought to remain latent until reactivated, leading to viremia.

Itching can be moderately severe in a minority of cases. Most patients, such as this one, are not bothered much by the condition once they understand its self-limited nature. They usually are not happy, however, to learn that it could persist for nine weeks or more, whether treated or not.

UV light exposure can be helpful in hastening PR’s departure, and topical corticosteroids (class III or IV; eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) can help control the itching. Neither oral nor topical antihistamines will help, since PR is not a histamine-mediated problem.

If the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy could at least rule out the more serious items in the differential, which include syphilis, drug rash, and psoriasis. In cases in which fungal origin is a possibility, a quick KOH prep will settle the issue. However, it must be remembered that one doesn’t just “get” a fungal infection. There has to be a source (animal, child), and that source is usually identified with minimal history taking.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (choice “b”), a common and very distinctive eruption related to human herpesvirus 6 and 7.

Allergic reaction to methotrexate (choice “a”), while far from unknown, does not resemble pityriasis rosea. It also would not be limited to such a relatively small area.

Pityriasis rosea is often designated as “fungal infection” (choice “c”) by the uninitiated. However, the lesions of dermatophytosis would be round, with a leading scaly edge, and unlikely to be found in this distribution.

Secondary syphilis (choice “d”) is a major item in the pityriasis rosea differential, but it almost always involves the palms and soles and the lesions would be round (not oval) scaly brown papules. Furthermore, assuming we have an honest patient, we’re also missing a source for sexually transmitted infection.

DISCUSSION

One could hardly ask for a more classic case of pityriasis rosea (PR), which primarily affects patients ages 14 to 40. Alas, that being said, one cannot depend on seeing all these clues in every PR patient.

For example, the herald patch (also known as the mother patch) is missing in at least half of cases. In others, the lesions are smaller, sparser, and more papular (especially in young black patients). The condition may even be confined to intertriginous areas (eg, the groin and/or axillae); this is known as inverse PR.

While salmon-colored scaly lesions are considered a classic presentation, PR can present with darker ovoid macules that have minimal scale and, rarely, become bullous. Involvement above the neck is rare.

What is consistent and dependable among signs of PR is the centripetal scale, seen even in the smallest lesions. This scale is so fine that the old dermatology texts called it “cigarette paper” scale or “scurf.”

After decades of speculation, researchers finally provided strong evidence of the probable cause of PR: replication of human herpesvirus 6 and 7, present in mono-

nuclear cells of lesional skin. Though universally acquired in childhood, these viruses are thought to remain latent until reactivated, leading to viremia.

Itching can be moderately severe in a minority of cases. Most patients, such as this one, are not bothered much by the condition once they understand its self-limited nature. They usually are not happy, however, to learn that it could persist for nine weeks or more, whether treated or not.

UV light exposure can be helpful in hastening PR’s departure, and topical corticosteroids (class III or IV; eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) can help control the itching. Neither oral nor topical antihistamines will help, since PR is not a histamine-mediated problem.

If the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy could at least rule out the more serious items in the differential, which include syphilis, drug rash, and psoriasis. In cases in which fungal origin is a possibility, a quick KOH prep will settle the issue. However, it must be remembered that one doesn’t just “get” a fungal infection. There has to be a source (animal, child), and that source is usually identified with minimal history taking.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (choice “b”), a common and very distinctive eruption related to human herpesvirus 6 and 7.

Allergic reaction to methotrexate (choice “a”), while far from unknown, does not resemble pityriasis rosea. It also would not be limited to such a relatively small area.

Pityriasis rosea is often designated as “fungal infection” (choice “c”) by the uninitiated. However, the lesions of dermatophytosis would be round, with a leading scaly edge, and unlikely to be found in this distribution.

Secondary syphilis (choice “d”) is a major item in the pityriasis rosea differential, but it almost always involves the palms and soles and the lesions would be round (not oval) scaly brown papules. Furthermore, assuming we have an honest patient, we’re also missing a source for sexually transmitted infection.

DISCUSSION

One could hardly ask for a more classic case of pityriasis rosea (PR), which primarily affects patients ages 14 to 40. Alas, that being said, one cannot depend on seeing all these clues in every PR patient.

For example, the herald patch (also known as the mother patch) is missing in at least half of cases. In others, the lesions are smaller, sparser, and more papular (especially in young black patients). The condition may even be confined to intertriginous areas (eg, the groin and/or axillae); this is known as inverse PR.

While salmon-colored scaly lesions are considered a classic presentation, PR can present with darker ovoid macules that have minimal scale and, rarely, become bullous. Involvement above the neck is rare.

What is consistent and dependable among signs of PR is the centripetal scale, seen even in the smallest lesions. This scale is so fine that the old dermatology texts called it “cigarette paper” scale or “scurf.”

After decades of speculation, researchers finally provided strong evidence of the probable cause of PR: replication of human herpesvirus 6 and 7, present in mono-

nuclear cells of lesional skin. Though universally acquired in childhood, these viruses are thought to remain latent until reactivated, leading to viremia.

Itching can be moderately severe in a minority of cases. Most patients, such as this one, are not bothered much by the condition once they understand its self-limited nature. They usually are not happy, however, to learn that it could persist for nine weeks or more, whether treated or not.

UV light exposure can be helpful in hastening PR’s departure, and topical corticosteroids (class III or IV; eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) can help control the itching. Neither oral nor topical antihistamines will help, since PR is not a histamine-mediated problem.

If the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy could at least rule out the more serious items in the differential, which include syphilis, drug rash, and psoriasis. In cases in which fungal origin is a possibility, a quick KOH prep will settle the issue. However, it must be remembered that one doesn’t just “get” a fungal infection. There has to be a source (animal, child), and that source is usually identified with minimal history taking.

Two weeks ago, an itchy rash appeared on a man’s back before spreading to his chest and neck. He has never experienced anything like it before, and no one else in his household is similarly affected. He denies night sweats, fever, and malaise but reports that he was recently diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. His rheumatologist started him on methotrexate (12.5 mg/wk) after extensive labwork (complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and hepatitis profile) was performed. He denies any history of high-risk sexual behavior or exposure, exposure to animals or children, or history of foreign travel. The patient, who appears well, is afebrile and in no distress. The original lesion, on his upper left back, is distinctly pinkish brown and round, with an odd fine scale around its inner rim, and measures about 3 cm in diameter. Elsewhere, examination reveals about 15 more lesions. All are oval but similarly pinkish brown, averaging about 2 cm in their long axis. These smaller lesions form a necklace-like configuration, paralleling the natural skin lines of the neck. Each lesion has central scaling identical to that of the original back lesion. Examination of the patient’s palms and soles fails to reveal any cutaneous abnormalities. Likewise, examination of the oral cavity is normal. No palpable nodes are felt around the neck, in the axillae, or in the groin.

A Visiting Grandma Feels Short of Breath

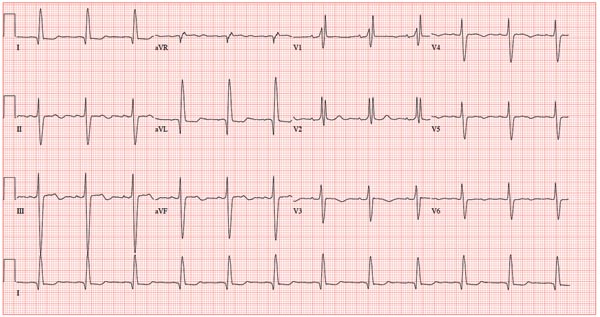

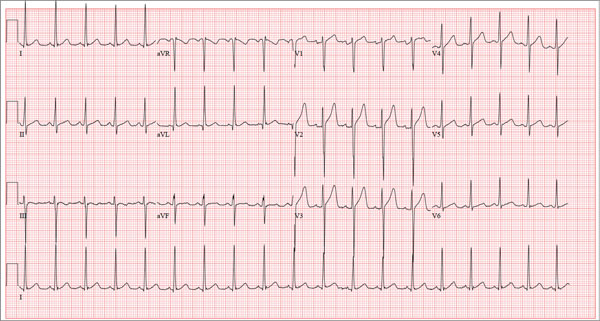

ANSWER

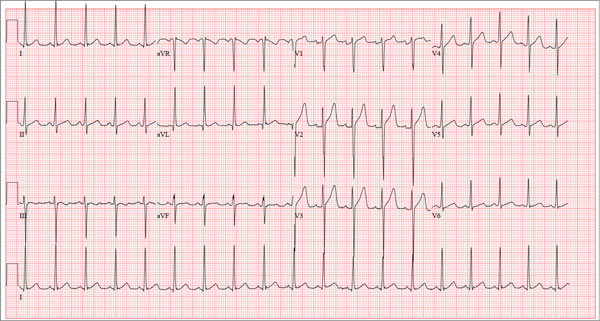

This ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). RBBB and LAFB are consistent with bifascicular block.

Criteria for an RBBB include a prolonged total QRS complex of 120 ms or longer and an RSR’ complex (“rabbit ears”) in lead V1. LAFB criteria include a QRS of normal duration with an S wave greater than an R wave in leads II, III, and aVF and left-axis deviation (–48° in this case).

The astute reader may question the disparity between RBBB and LAFB, since the criteria for the former include a prolonged QRS interval and the criteria for the latter include a normal QRS interval. It should be noted that the requirements for QRS duration for RBBB vary.

Bifascicular block (RBBB and either LAFB or left posterior fascicular block [LPFB]) is indicative of more advanced conduction system disease. However, it is not an indication for permanent pacemaker placement in an asymptomatic patient.

This patient was treated for a community-acquired right lower lobe pneumonia and a UTI.

ANSWER

This ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). RBBB and LAFB are consistent with bifascicular block.

Criteria for an RBBB include a prolonged total QRS complex of 120 ms or longer and an RSR’ complex (“rabbit ears”) in lead V1. LAFB criteria include a QRS of normal duration with an S wave greater than an R wave in leads II, III, and aVF and left-axis deviation (–48° in this case).

The astute reader may question the disparity between RBBB and LAFB, since the criteria for the former include a prolonged QRS interval and the criteria for the latter include a normal QRS interval. It should be noted that the requirements for QRS duration for RBBB vary.

Bifascicular block (RBBB and either LAFB or left posterior fascicular block [LPFB]) is indicative of more advanced conduction system disease. However, it is not an indication for permanent pacemaker placement in an asymptomatic patient.

This patient was treated for a community-acquired right lower lobe pneumonia and a UTI.

ANSWER

This ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). RBBB and LAFB are consistent with bifascicular block.

Criteria for an RBBB include a prolonged total QRS complex of 120 ms or longer and an RSR’ complex (“rabbit ears”) in lead V1. LAFB criteria include a QRS of normal duration with an S wave greater than an R wave in leads II, III, and aVF and left-axis deviation (–48° in this case).

The astute reader may question the disparity between RBBB and LAFB, since the criteria for the former include a prolonged QRS interval and the criteria for the latter include a normal QRS interval. It should be noted that the requirements for QRS duration for RBBB vary.

Bifascicular block (RBBB and either LAFB or left posterior fascicular block [LPFB]) is indicative of more advanced conduction system disease. However, it is not an indication for permanent pacemaker placement in an asymptomatic patient.

This patient was treated for a community-acquired right lower lobe pneumonia and a UTI.

A 78-year-old woman presents to your urgent care clinic with a four-day history of lethargy. She lives in another state but currently is visiting her granddaughter, who happens to be your clinic manager. She says she felt weak prior to her trip but thought it was probably due to a urinary tract infection (UTI). Yesterday, however, she started feeling short of breath. The patient denies chest pain, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or productive cough. She reports feeling feverish this morning but did not record her temperature, adding that it seemed to subside after she got dressed. Her medical history is positive for frequent UTIs, a remote cholecystectomy, hypothyroidism, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. According to the patient’s daughter, who is present, her mother’s cardiologist recently mentioned some “funny” findings on an ECG; she didn’t really understand his explanation but they were told “not to worry.” The patient, a retired schoolteacher, lives in an assisted living center. She is independent and has been a widow for 14 years, since her husband died of an acute MI. She has two children who are in good health. She has never smoked, rarely consumes alcohol, and has never used recreational or homeopathic drugs. Her current medications include warfarin, levothyroxine, and conjugated estrogen. She was taking amiodarone for rhythm control of atrial fibrillation but stopped six months ago when her skin started turning blue. She is allergic to penicillin, which causes a true anaphylactic reaction, according to her daughter. Review of systems is positive for an infrequent, nonproductive cough, sun sensitivity due to amiodarone use, and infrequent burning with urination. Physical exam reveals a thin, elderly woman in no distress. Her blood pressure is 152/88 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1 with an infrequent, nonproductive cough; O2 saturation, 94% on room air; and temperature, 99°F. She is 5 ft 4 in tall and weighs 114 lb. Pertinent findings on physical exam include corrective lenses, pearly white skin with a blue hue on the nose and ears secondary to long-term amiodarone therapy, no evidence of thyromegaly or jugular distention, a regular rate and rhythm with a soft midsystolic murmur of mitral regurgitation, and no extra heart sounds. Her lungs are remarkable for consolidation in the right lower lobe, with crackles that change with coughing. Her abdomen is soft and nontender, and there is no peripheral edema. Her neurologic exam is intact. She is alert, attentive, and very witty in her responses to questions. Laboratory data include urinalysis findings suggestive of a UTI, a white blood cell count of 9.8 x 103/μL, and a hematocrit of 35%. A chest x-ray shows evidence of consolidation in the right lower lobe, which the radiologist says is strongly suggestive of pneumonia. An ECG shows a ventricular rate of 71 beats/min; PR interval, 152 ms; QRS duration, 142 ms; QT/QTc interval, 476/517 ms; P axis, 76°; R axis, –48°; and T axis, 161°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Nontender Nodules on the Lower Lip

The Diagnosis: Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

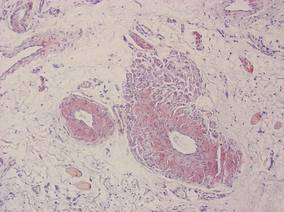

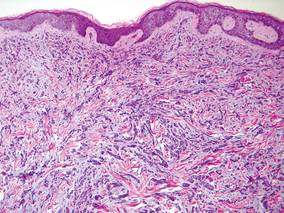

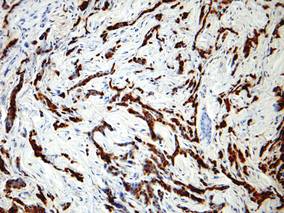

Our patient presented with multiple firm waxy nodules on the mucosal surface of the lower lip. Excision biopsy showed thickening of blood vessel walls with abundant amorphous material that was consistent with amyloid. Further staining with Congo red demonstrated brick red amorphous material within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (Figure 1), and crystal violet stain showed metachromasia (Figure 2). Fine needle aspiration of the abdominal fat-pad showed amyloid. The final diagnosis was primary systemic amyloidosis (PSA).

|

| Figure 1. Congo red staining showed a brick red appearance of amyloid within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 2. Crystal violet staining around the blood vessels showed metachromasia (original magnification ×100). |

Amyloid is an ubiquitous fibrillar protein arranged in a cross-beta-pleated sheet that is confirmed with x-ray crystallography.1,2 More than 25 variants of amyloid have been identified.3 Pathologic deposition of amyloid-derived material results in a variable spectrum of clinical findings, collectively known as amyloidosis, with presentations ranging from nonspecific fever or fatigue to frank organ failure, depending on the organ involved. In PSA, immunoglobulin light chains are deposited throughout the body. Associated conditions include malignant or benign monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, malignant lymphoma, heavy chain disease, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.2,4 The most commonly involved organ systems are the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. When patients present with unexplained heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or renal insufficiency, amyloidosis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.3

Cutaneous lesions of PSA tend to be vascular due to amyloid infiltration of blood vessel walls, manifesting as petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, or nonhealing ulcers. Pinch purpura frequently are seen in the periorbital region after minor trauma and are recognized as a clinical indicator of PSA.2,4 Xerostomia from amyloid infiltrates in salivary glands is extremely common, and cases of amyloid in the eyes, bones, and thyroid gland have been reported.2 Macroglossia is seen in 12% to 40% of cases; coupled with xerostomia, it can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.2,5

Systemic amyloidosis can be further divided into primary (idiopathic or multiple myeloma associated) or secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions or infections; the key difference is the protein from which the abnormal amyloid is derived.1,4 The presence of cutaneous amyloidosis renders the need to rule out systemic disease because amyloidosis may be a purely localized or systemic process.4 Nodular amyloidosis is a localized form of amyloid that also has immunoglobulin light chain deposits and clinically appears exactly the same as PSA; however, the deposits are restricted to the skin.1,2,4,5

Characteristic biopsy findings in cutaneous amyloidosis include amorphous orange-red amyloid deposits on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. The gold standard for amyloid detection is apple green birefringence under polarized light with Congo red stain or electron microscopy.6,7 Other stains used to identify amyloid include crystal violet, methyl violet, periodic acid–Schiff, Sirius red, pagoda red, Dylon stain, and thioflavine T.1,2 Confirmation of systemic disease can be accomplished by fine needle aspiration of abdominal fat-pads or rectal mucosal biopsies.1,3,4 Biopsy of accessory salivary glands also has been reported to be very sensitive and specific.2

Treatment options remain limited; localized cutaneous disease may respond to topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or phototherapy. Primary systemic amyloidosis can be treated with a combination of steroids, melphalan, or colchicine often followed by autologous stem cell transplantation8; however, these regimens are not always curative and patients often have a poor prognosis.1

1. Black MM, Upjohn E, Albert S. Amyloidosis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:623-631.

2. Steciuk A, Dompmartin A, Troussard X, et al. Cutaneous amyloidosis and possible association with systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:127-132.

3. Picken MM. Amyloidosis-where are we now and where are we heading? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:545-551.

4. Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Vogt T, et al. Cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidoses with cutaneous involvement. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:152-160.

5. Breathnach SM. Amyloid and amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):1-16.

6. Li WM. Histopathology of primary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:30-35.

7. Lin CS, Wong CK. Electron microscopy of primary and secondary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:36-45.

8. Dember LM. Modern treatment of amyloidosis: unresolved questions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:469-472.

The Diagnosis: Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Our patient presented with multiple firm waxy nodules on the mucosal surface of the lower lip. Excision biopsy showed thickening of blood vessel walls with abundant amorphous material that was consistent with amyloid. Further staining with Congo red demonstrated brick red amorphous material within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (Figure 1), and crystal violet stain showed metachromasia (Figure 2). Fine needle aspiration of the abdominal fat-pad showed amyloid. The final diagnosis was primary systemic amyloidosis (PSA).

|

| Figure 1. Congo red staining showed a brick red appearance of amyloid within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 2. Crystal violet staining around the blood vessels showed metachromasia (original magnification ×100). |

Amyloid is an ubiquitous fibrillar protein arranged in a cross-beta-pleated sheet that is confirmed with x-ray crystallography.1,2 More than 25 variants of amyloid have been identified.3 Pathologic deposition of amyloid-derived material results in a variable spectrum of clinical findings, collectively known as amyloidosis, with presentations ranging from nonspecific fever or fatigue to frank organ failure, depending on the organ involved. In PSA, immunoglobulin light chains are deposited throughout the body. Associated conditions include malignant or benign monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, malignant lymphoma, heavy chain disease, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.2,4 The most commonly involved organ systems are the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. When patients present with unexplained heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or renal insufficiency, amyloidosis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.3

Cutaneous lesions of PSA tend to be vascular due to amyloid infiltration of blood vessel walls, manifesting as petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, or nonhealing ulcers. Pinch purpura frequently are seen in the periorbital region after minor trauma and are recognized as a clinical indicator of PSA.2,4 Xerostomia from amyloid infiltrates in salivary glands is extremely common, and cases of amyloid in the eyes, bones, and thyroid gland have been reported.2 Macroglossia is seen in 12% to 40% of cases; coupled with xerostomia, it can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.2,5

Systemic amyloidosis can be further divided into primary (idiopathic or multiple myeloma associated) or secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions or infections; the key difference is the protein from which the abnormal amyloid is derived.1,4 The presence of cutaneous amyloidosis renders the need to rule out systemic disease because amyloidosis may be a purely localized or systemic process.4 Nodular amyloidosis is a localized form of amyloid that also has immunoglobulin light chain deposits and clinically appears exactly the same as PSA; however, the deposits are restricted to the skin.1,2,4,5

Characteristic biopsy findings in cutaneous amyloidosis include amorphous orange-red amyloid deposits on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. The gold standard for amyloid detection is apple green birefringence under polarized light with Congo red stain or electron microscopy.6,7 Other stains used to identify amyloid include crystal violet, methyl violet, periodic acid–Schiff, Sirius red, pagoda red, Dylon stain, and thioflavine T.1,2 Confirmation of systemic disease can be accomplished by fine needle aspiration of abdominal fat-pads or rectal mucosal biopsies.1,3,4 Biopsy of accessory salivary glands also has been reported to be very sensitive and specific.2

Treatment options remain limited; localized cutaneous disease may respond to topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or phototherapy. Primary systemic amyloidosis can be treated with a combination of steroids, melphalan, or colchicine often followed by autologous stem cell transplantation8; however, these regimens are not always curative and patients often have a poor prognosis.1

The Diagnosis: Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Our patient presented with multiple firm waxy nodules on the mucosal surface of the lower lip. Excision biopsy showed thickening of blood vessel walls with abundant amorphous material that was consistent with amyloid. Further staining with Congo red demonstrated brick red amorphous material within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (Figure 1), and crystal violet stain showed metachromasia (Figure 2). Fine needle aspiration of the abdominal fat-pad showed amyloid. The final diagnosis was primary systemic amyloidosis (PSA).

|

| Figure 1. Congo red staining showed a brick red appearance of amyloid within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 2. Crystal violet staining around the blood vessels showed metachromasia (original magnification ×100). |

Amyloid is an ubiquitous fibrillar protein arranged in a cross-beta-pleated sheet that is confirmed with x-ray crystallography.1,2 More than 25 variants of amyloid have been identified.3 Pathologic deposition of amyloid-derived material results in a variable spectrum of clinical findings, collectively known as amyloidosis, with presentations ranging from nonspecific fever or fatigue to frank organ failure, depending on the organ involved. In PSA, immunoglobulin light chains are deposited throughout the body. Associated conditions include malignant or benign monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, malignant lymphoma, heavy chain disease, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.2,4 The most commonly involved organ systems are the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. When patients present with unexplained heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or renal insufficiency, amyloidosis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.3

Cutaneous lesions of PSA tend to be vascular due to amyloid infiltration of blood vessel walls, manifesting as petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, or nonhealing ulcers. Pinch purpura frequently are seen in the periorbital region after minor trauma and are recognized as a clinical indicator of PSA.2,4 Xerostomia from amyloid infiltrates in salivary glands is extremely common, and cases of amyloid in the eyes, bones, and thyroid gland have been reported.2 Macroglossia is seen in 12% to 40% of cases; coupled with xerostomia, it can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.2,5

Systemic amyloidosis can be further divided into primary (idiopathic or multiple myeloma associated) or secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions or infections; the key difference is the protein from which the abnormal amyloid is derived.1,4 The presence of cutaneous amyloidosis renders the need to rule out systemic disease because amyloidosis may be a purely localized or systemic process.4 Nodular amyloidosis is a localized form of amyloid that also has immunoglobulin light chain deposits and clinically appears exactly the same as PSA; however, the deposits are restricted to the skin.1,2,4,5

Characteristic biopsy findings in cutaneous amyloidosis include amorphous orange-red amyloid deposits on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. The gold standard for amyloid detection is apple green birefringence under polarized light with Congo red stain or electron microscopy.6,7 Other stains used to identify amyloid include crystal violet, methyl violet, periodic acid–Schiff, Sirius red, pagoda red, Dylon stain, and thioflavine T.1,2 Confirmation of systemic disease can be accomplished by fine needle aspiration of abdominal fat-pads or rectal mucosal biopsies.1,3,4 Biopsy of accessory salivary glands also has been reported to be very sensitive and specific.2

Treatment options remain limited; localized cutaneous disease may respond to topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or phototherapy. Primary systemic amyloidosis can be treated with a combination of steroids, melphalan, or colchicine often followed by autologous stem cell transplantation8; however, these regimens are not always curative and patients often have a poor prognosis.1

1. Black MM, Upjohn E, Albert S. Amyloidosis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:623-631.

2. Steciuk A, Dompmartin A, Troussard X, et al. Cutaneous amyloidosis and possible association with systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:127-132.

3. Picken MM. Amyloidosis-where are we now and where are we heading? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:545-551.

4. Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Vogt T, et al. Cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidoses with cutaneous involvement. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:152-160.

5. Breathnach SM. Amyloid and amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):1-16.

6. Li WM. Histopathology of primary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:30-35.

7. Lin CS, Wong CK. Electron microscopy of primary and secondary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:36-45.

8. Dember LM. Modern treatment of amyloidosis: unresolved questions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:469-472.

1. Black MM, Upjohn E, Albert S. Amyloidosis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:623-631.

2. Steciuk A, Dompmartin A, Troussard X, et al. Cutaneous amyloidosis and possible association with systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:127-132.

3. Picken MM. Amyloidosis-where are we now and where are we heading? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:545-551.

4. Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Vogt T, et al. Cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidoses with cutaneous involvement. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:152-160.

5. Breathnach SM. Amyloid and amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):1-16.

6. Li WM. Histopathology of primary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:30-35.

7. Lin CS, Wong CK. Electron microscopy of primary and secondary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:36-45.

8. Dember LM. Modern treatment of amyloidosis: unresolved questions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:469-472.

A 71-year-old woman presented with multiple 3×3-mm, firm, nontender nodules of 3 years’ duration on the mucosal surface of the lower lip that gradually enlarged. There was no macroglossia on presentation. The lip nodules were asymptomatic; however, they did interfere with eating and drinking, necessitating the use of a straw. Her medical history was remarkable for emphysema that required supplemental oxygen, rheumatoid arthritis, orthostatic hypotension, renal insufficiency, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and Sjögren syndrome. She also had a recent thyroidectomy due to multiple thyroid nodules. An excision biopsy was performed of the lip nodules.

Tender Subcutaneous Nodules on the Back and Shoulders

The Diagnosis: Prostate Cancer Metastases

Cutaneous involvement of visceral tumors can occur indirectly, with the tumor causing changes in the skin without the presence of tumor cells (ie, paraneoplastic processes), or directly, with the presence of tumor cells in the skin (ie, metastasis).1 Cutaneous metastases from solid primary tumors are uncommon. The incidence of metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies ranges from 0.3% to 9.0%.2 The most common primary internal tumors to metastasize to the skin are those arising from the breasts, lungs, colon, ovaries, and head and neck.3 Although prostate cancer is the most common cancer in males (making up 28% of new cancer diagnoses), excluding basal and squamous cell skin cancers, it rarely metastasizes to the skin, representing less than 1% of all cutaneous metastasis.4,5

There are 4 proposed mechanisms for metastatic dissemination to the skin: (1) direct invasion from underlying neoplasm; (2) implantation from a surgical scar; (3) spread through the lymphatics; and/or (4) hematogenous spread. The most common sites of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis are the inguinal area, penis, and lower abdomen,2 which is likely due to spread via the lymphatic drainage. Cutaneous metastasis to distant sites such as the scalp or chest, as in our patient, may be secondary to hematogenous spread.

Generally, cutaneous metastases from visceral malignancies manifest as urticaria or a nonspecific macular rash.2 However, prostate cancer cutaneous metastases commonly present as papules or subcutaneous nodules but also can have inflammatory, cicatricial, sclerodermoid, telangiectatic, or zosteriform morphologies.2,5,6 The lesions of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases are typically well-circumscribed, flesh-colored or pink to red, oval plaques or nodules ranging in size from several millimeters to a few centimeters.2 The cutaneous lesions generally are multiple and can be localized or diffuse in distribution. The clinical differential diagnosis is broad in patients undergoing systemic treatment of prostate cancer and often includes drug reaction, cutaneous lymphoma, atypical mycobacterial or deep fungal infection, or paraneoplastic dermatosis.

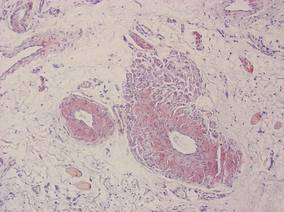

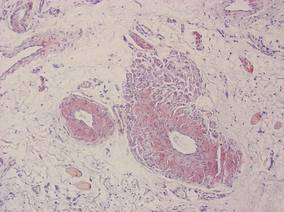

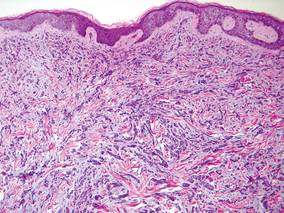

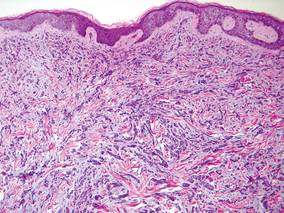

Laboratory studies often reveal an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, a glycoprotein that functions in the liquefaction of seminal fluid made primarily by the prostate, often in benign hypertrophic and malignant prostatic processes.7 Definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis can be established by histologic examination. Excisional or punch biopsy is preferred over superficial shave biopsy. Metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma often reveals infiltrative growth of disorganized atypical epithelial cells along collagen bundles in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 1).2,8 The presence of lymphovascular invasion further increases the suspicion of metastasis. Metastatic lesions may resemble the primary lesion; however, they are often poorly differentiated, making histologic comparison difficult.

|

| Figure 1. Biopsy revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. Atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were present (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

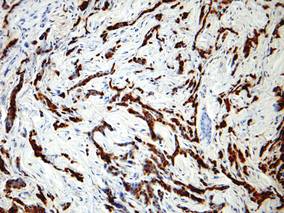

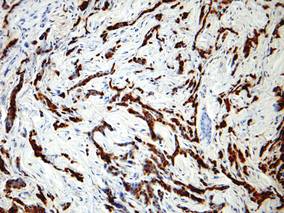

| Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for prostate-specific antigen and focally positive for prostate-specific acid phosphatase (original magnification ×100). |

The diagnosis is confirmed immunohistochemically with PSA and/or prostate-specific acid phosphatase immunostaining (Figure 2), which together have nearly 100% specificity for prostate adenocarcinomas.9 Although rare, PSA and or prostate-specific acid phosphatase may be weakly positive in nephrogenic adenoma.10 Another biomarker, urinary prostate cancer antigen 3, is being evaluated to identify men with indolent prostate cancer.11 It is unknown how useful this marker will be in the immunohistochemical identification of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases.

A large review of reported cases of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies revealed that the majority of patients had known systemic disease but enjoyed a good performance status at the time of diagnosis.2 As such, skin metastases may serve as the initial indicator of visceral recurrence. Prostate cancer is second only to lung cancer as the deadliest cancer in males,4 and cutaneous metastasis garners a particularly poor prognosis. The mean survival time after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis is 7 months.8 Therefore, treatment of cutaneous metastases is largely palliative, including local excision and intralesional chemotherapy.

1. Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:73-98.

2. Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

3. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29:1298-1307.

4. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

5. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-182.

6. Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600.

7. Tosoian J, Loeb S. PSA and beyond: the past, present, and future of investigative biomarkers for prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1919-1931.

8. Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684.

9. Nadji M, Tabei SZ, Castro A, et al. Prostate-specific antigen: an immunohistochemical marker for prostatic neoplasms. Cancer. 1981;48:1229-1232.

10. Paner GP, Luthringer DJ, Amin MB. Best practice in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: prostate carcinoma and its mimics in needle core biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1388-1396.

11. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3669-3676.

The Diagnosis: Prostate Cancer Metastases

Cutaneous involvement of visceral tumors can occur indirectly, with the tumor causing changes in the skin without the presence of tumor cells (ie, paraneoplastic processes), or directly, with the presence of tumor cells in the skin (ie, metastasis).1 Cutaneous metastases from solid primary tumors are uncommon. The incidence of metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies ranges from 0.3% to 9.0%.2 The most common primary internal tumors to metastasize to the skin are those arising from the breasts, lungs, colon, ovaries, and head and neck.3 Although prostate cancer is the most common cancer in males (making up 28% of new cancer diagnoses), excluding basal and squamous cell skin cancers, it rarely metastasizes to the skin, representing less than 1% of all cutaneous metastasis.4,5

There are 4 proposed mechanisms for metastatic dissemination to the skin: (1) direct invasion from underlying neoplasm; (2) implantation from a surgical scar; (3) spread through the lymphatics; and/or (4) hematogenous spread. The most common sites of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis are the inguinal area, penis, and lower abdomen,2 which is likely due to spread via the lymphatic drainage. Cutaneous metastasis to distant sites such as the scalp or chest, as in our patient, may be secondary to hematogenous spread.

Generally, cutaneous metastases from visceral malignancies manifest as urticaria or a nonspecific macular rash.2 However, prostate cancer cutaneous metastases commonly present as papules or subcutaneous nodules but also can have inflammatory, cicatricial, sclerodermoid, telangiectatic, or zosteriform morphologies.2,5,6 The lesions of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases are typically well-circumscribed, flesh-colored or pink to red, oval plaques or nodules ranging in size from several millimeters to a few centimeters.2 The cutaneous lesions generally are multiple and can be localized or diffuse in distribution. The clinical differential diagnosis is broad in patients undergoing systemic treatment of prostate cancer and often includes drug reaction, cutaneous lymphoma, atypical mycobacterial or deep fungal infection, or paraneoplastic dermatosis.

Laboratory studies often reveal an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, a glycoprotein that functions in the liquefaction of seminal fluid made primarily by the prostate, often in benign hypertrophic and malignant prostatic processes.7 Definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis can be established by histologic examination. Excisional or punch biopsy is preferred over superficial shave biopsy. Metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma often reveals infiltrative growth of disorganized atypical epithelial cells along collagen bundles in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 1).2,8 The presence of lymphovascular invasion further increases the suspicion of metastasis. Metastatic lesions may resemble the primary lesion; however, they are often poorly differentiated, making histologic comparison difficult.

|

| Figure 1. Biopsy revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. Atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were present (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for prostate-specific antigen and focally positive for prostate-specific acid phosphatase (original magnification ×100). |

The diagnosis is confirmed immunohistochemically with PSA and/or prostate-specific acid phosphatase immunostaining (Figure 2), which together have nearly 100% specificity for prostate adenocarcinomas.9 Although rare, PSA and or prostate-specific acid phosphatase may be weakly positive in nephrogenic adenoma.10 Another biomarker, urinary prostate cancer antigen 3, is being evaluated to identify men with indolent prostate cancer.11 It is unknown how useful this marker will be in the immunohistochemical identification of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases.

A large review of reported cases of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies revealed that the majority of patients had known systemic disease but enjoyed a good performance status at the time of diagnosis.2 As such, skin metastases may serve as the initial indicator of visceral recurrence. Prostate cancer is second only to lung cancer as the deadliest cancer in males,4 and cutaneous metastasis garners a particularly poor prognosis. The mean survival time after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis is 7 months.8 Therefore, treatment of cutaneous metastases is largely palliative, including local excision and intralesional chemotherapy.

The Diagnosis: Prostate Cancer Metastases

Cutaneous involvement of visceral tumors can occur indirectly, with the tumor causing changes in the skin without the presence of tumor cells (ie, paraneoplastic processes), or directly, with the presence of tumor cells in the skin (ie, metastasis).1 Cutaneous metastases from solid primary tumors are uncommon. The incidence of metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies ranges from 0.3% to 9.0%.2 The most common primary internal tumors to metastasize to the skin are those arising from the breasts, lungs, colon, ovaries, and head and neck.3 Although prostate cancer is the most common cancer in males (making up 28% of new cancer diagnoses), excluding basal and squamous cell skin cancers, it rarely metastasizes to the skin, representing less than 1% of all cutaneous metastasis.4,5

There are 4 proposed mechanisms for metastatic dissemination to the skin: (1) direct invasion from underlying neoplasm; (2) implantation from a surgical scar; (3) spread through the lymphatics; and/or (4) hematogenous spread. The most common sites of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis are the inguinal area, penis, and lower abdomen,2 which is likely due to spread via the lymphatic drainage. Cutaneous metastasis to distant sites such as the scalp or chest, as in our patient, may be secondary to hematogenous spread.

Generally, cutaneous metastases from visceral malignancies manifest as urticaria or a nonspecific macular rash.2 However, prostate cancer cutaneous metastases commonly present as papules or subcutaneous nodules but also can have inflammatory, cicatricial, sclerodermoid, telangiectatic, or zosteriform morphologies.2,5,6 The lesions of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases are typically well-circumscribed, flesh-colored or pink to red, oval plaques or nodules ranging in size from several millimeters to a few centimeters.2 The cutaneous lesions generally are multiple and can be localized or diffuse in distribution. The clinical differential diagnosis is broad in patients undergoing systemic treatment of prostate cancer and often includes drug reaction, cutaneous lymphoma, atypical mycobacterial or deep fungal infection, or paraneoplastic dermatosis.

Laboratory studies often reveal an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, a glycoprotein that functions in the liquefaction of seminal fluid made primarily by the prostate, often in benign hypertrophic and malignant prostatic processes.7 Definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis can be established by histologic examination. Excisional or punch biopsy is preferred over superficial shave biopsy. Metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma often reveals infiltrative growth of disorganized atypical epithelial cells along collagen bundles in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 1).2,8 The presence of lymphovascular invasion further increases the suspicion of metastasis. Metastatic lesions may resemble the primary lesion; however, they are often poorly differentiated, making histologic comparison difficult.

|

| Figure 1. Biopsy revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. Atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were present (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for prostate-specific antigen and focally positive for prostate-specific acid phosphatase (original magnification ×100). |

The diagnosis is confirmed immunohistochemically with PSA and/or prostate-specific acid phosphatase immunostaining (Figure 2), which together have nearly 100% specificity for prostate adenocarcinomas.9 Although rare, PSA and or prostate-specific acid phosphatase may be weakly positive in nephrogenic adenoma.10 Another biomarker, urinary prostate cancer antigen 3, is being evaluated to identify men with indolent prostate cancer.11 It is unknown how useful this marker will be in the immunohistochemical identification of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases.

A large review of reported cases of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies revealed that the majority of patients had known systemic disease but enjoyed a good performance status at the time of diagnosis.2 As such, skin metastases may serve as the initial indicator of visceral recurrence. Prostate cancer is second only to lung cancer as the deadliest cancer in males,4 and cutaneous metastasis garners a particularly poor prognosis. The mean survival time after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis is 7 months.8 Therefore, treatment of cutaneous metastases is largely palliative, including local excision and intralesional chemotherapy.

1. Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:73-98.

2. Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

3. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29:1298-1307.

4. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

5. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-182.

6. Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600.

7. Tosoian J, Loeb S. PSA and beyond: the past, present, and future of investigative biomarkers for prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1919-1931.

8. Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684.

9. Nadji M, Tabei SZ, Castro A, et al. Prostate-specific antigen: an immunohistochemical marker for prostatic neoplasms. Cancer. 1981;48:1229-1232.

10. Paner GP, Luthringer DJ, Amin MB. Best practice in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: prostate carcinoma and its mimics in needle core biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1388-1396.

11. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3669-3676.

1. Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:73-98.

2. Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

3. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29:1298-1307.

4. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

5. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-182.

6. Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600.

7. Tosoian J, Loeb S. PSA and beyond: the past, present, and future of investigative biomarkers for prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1919-1931.

8. Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684.

9. Nadji M, Tabei SZ, Castro A, et al. Prostate-specific antigen: an immunohistochemical marker for prostatic neoplasms. Cancer. 1981;48:1229-1232.

10. Paner GP, Luthringer DJ, Amin MB. Best practice in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: prostate carcinoma and its mimics in needle core biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1388-1396.

11. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3669-3676.

A 57-year-old cachectic man with a history of metastatic, hormone-refractory adenocarcinoma of the prostate presented with multiple tender subcutaneous nodules on the back and shoulders that developed over the course of 12 months. During that time, he was treated with cyclophosphamide, leuprolide acetate, bicalutamide, zoledronic acid, and filgrastim. A punch biopsy specimen obtained from the left shoulder revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. The atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were observed.

Shedding of the Fingernails

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis

The nail changes were characteristic of onychomadesis. Systemic illness in this patient most likely resulted in temporary arrest of nail matrix activity, leading to separation of the proximal nail plate from the proximal nail fold, which gave rise to a deep transverse sulcus.1 Conversely, Beau lines are characterized by transverse grooves that move distally as the nail grows. Onychomadesis also is seen in pemphigus vulgaris, which could be due to an autoimmune disease inhibiting normal nail plate growth and development of blisters beneath the nail causing detachment of the nail plate.2 Drug-induced Beau lines or onychomadesis are most frequently caused by chemotherapeutic agents (taxanes) and retinoids, which reflect an arrest in epithelial proliferation.3 Familial cases also have been described.4 Management of the nail abnormality should focus on the underlying medical problem or triggering factor. In our patient, hypertension and kidney disease were managed by a low-salt diet, oral antihypertensives, and iron replacement.

1. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

2. Engineer L, Norton LA, Ahmed AR. Nail involvement in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:529-535.

3. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

4. Mehra A, Murphy RJ, Wilson BB. Idiopathic familial onychomadesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):349-350.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis

The nail changes were characteristic of onychomadesis. Systemic illness in this patient most likely resulted in temporary arrest of nail matrix activity, leading to separation of the proximal nail plate from the proximal nail fold, which gave rise to a deep transverse sulcus.1 Conversely, Beau lines are characterized by transverse grooves that move distally as the nail grows. Onychomadesis also is seen in pemphigus vulgaris, which could be due to an autoimmune disease inhibiting normal nail plate growth and development of blisters beneath the nail causing detachment of the nail plate.2 Drug-induced Beau lines or onychomadesis are most frequently caused by chemotherapeutic agents (taxanes) and retinoids, which reflect an arrest in epithelial proliferation.3 Familial cases also have been described.4 Management of the nail abnormality should focus on the underlying medical problem or triggering factor. In our patient, hypertension and kidney disease were managed by a low-salt diet, oral antihypertensives, and iron replacement.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis

The nail changes were characteristic of onychomadesis. Systemic illness in this patient most likely resulted in temporary arrest of nail matrix activity, leading to separation of the proximal nail plate from the proximal nail fold, which gave rise to a deep transverse sulcus.1 Conversely, Beau lines are characterized by transverse grooves that move distally as the nail grows. Onychomadesis also is seen in pemphigus vulgaris, which could be due to an autoimmune disease inhibiting normal nail plate growth and development of blisters beneath the nail causing detachment of the nail plate.2 Drug-induced Beau lines or onychomadesis are most frequently caused by chemotherapeutic agents (taxanes) and retinoids, which reflect an arrest in epithelial proliferation.3 Familial cases also have been described.4 Management of the nail abnormality should focus on the underlying medical problem or triggering factor. In our patient, hypertension and kidney disease were managed by a low-salt diet, oral antihypertensives, and iron replacement.

1. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

2. Engineer L, Norton LA, Ahmed AR. Nail involvement in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:529-535.

3. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

4. Mehra A, Murphy RJ, Wilson BB. Idiopathic familial onychomadesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):349-350.

1. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

2. Engineer L, Norton LA, Ahmed AR. Nail involvement in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:529-535.

3. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

4. Mehra A, Murphy RJ, Wilson BB. Idiopathic familial onychomadesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):349-350.

A 70-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with abnormal-appearing fingernails of 6 months’ duration. Clinical examination showed complete shedding of the proximal nail plate and separation from the nail bed involving all the fingernails. There also was thickening of the distal nail plate. The patient also had diffuse thinning of the hair on the scalp. She had chronic kidney disease, likely from hypertensive nephrosclerosis, that was complicated by iron-deficient anemia. No new systemic medication had been given.

Man Falls on Buttocks

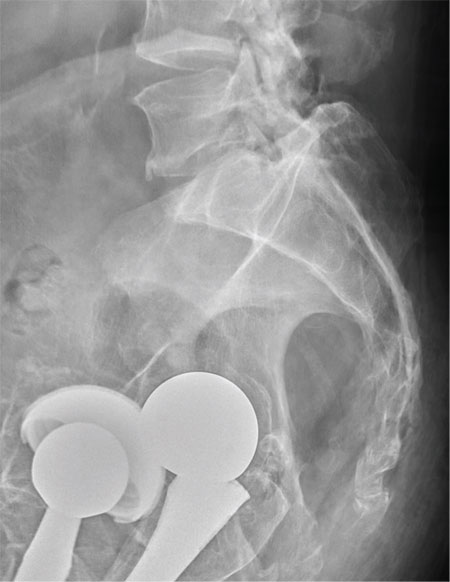

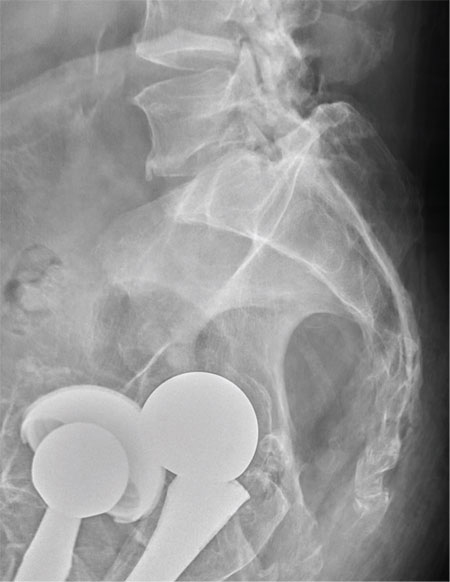

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

A 75-year-old man presents to the urgent care center for evaluation of pain in his buttocks after a fall. He states he was walking when his “legs gave out” and he hit the ground. He landed squarely on his buttocks, causing immediate pain. He was eventually able to get up with some assistance. He denies any current weakness or any bowel or bladder complaints. His medical/surgical history is significant for coronary artery disease, hypertension, and bilateral hip replacements. Physical exam reveals an elderly male who is uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. His vital signs are stable. He has moderate point tenderness over his sacrum but is able to move all his extremities well, with normal strength. Radiograph of his sacrum/coccyx is shown. What is your impression?

Does Young Athlete Have Cause for Concern?

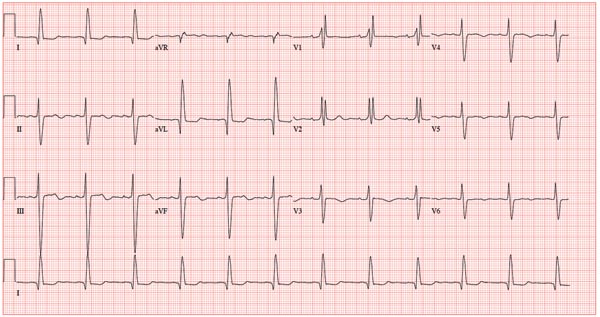

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.

The patient and his parents were reassured as to the young man’s condition but decided to seek a second opinion.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.