User login

Detached parents: How to help

While most of the parents you will see in your office will be thoughtful, engaged, and even anxious, occasionally you will encounter parents who seem detached from their children. Spending just a few extra minutes to understand this detachment could mean an enormous difference in the psychological health and developmental well-being of your patient.

It is striking when you see it: Flat affect, little eye contact, no questions or comments. If the parents seem unconnected to their children, it is worth being curious about it. Whether they are constantly on their phones or just disengaged, you should start by directing a question straight to them. Perhaps a question about the child’s sleep, appetite, or school performance is a good place to start. You would like to assess their knowledge of the child’s development, performance at school, friendships, and interests, to ensure that they are up to date and paying attention.

Once alone, you might start by offering your impression of how the child is doing, then observe that you noticed that they (the parents) seem quiet or distant. The following questions should help you better understand the nature of their detachment.

Depression

Ask about how they are sleeping. If the child is very young or the parents have a difficult work schedule, they might simply be sleep deprived, which you might help them address. Difficulty sleeping also can be a symptom of depression. Have they noticed any changes in their appetite or energy? Is it harder to concentrate? Have they felt more tearful, sad, or irritable? Have they noticed that they don’t get as much pleasure from things that usually bring them joy? Do they worry about being a burden to others? Major depressive disorder is relatively common, affecting as many as one in five women in the postpartum period and one in ten women generally.

Men experience depression at about half that rate, according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is a condition that can cause feelings of guilt and shame, so many suffer silently, missing the chance for treatment and raising the risk for suicide. Infants of depressed mothers often appear listless and may be fussier about sleeping and eating, which can exacerbate poor attachment with their parents, and lead to problems in later years, including anxiety, mood, or behavioral problems. A parent’s depression, particularly in the postpartum period, represents a serious threat to the child’s healthy development and well-being.

Tell the parents that what they have described to you sounds like it could be a depressive episode and that depression has a serious impact on the whole family. Offer that their primary care physicians can evaluate and treat depression, or learn about other resources in your community that you can refer them to for accessible care.

Overwhelming stress

Is the newborn or special needs child feeling like more responsibility than the parents can handle? Where do the parents find support? Has there been a recent job loss or has there been a financial setback for the family? Is a spouse ill, or are they also caring for an aging parent? Has there been a separation from the spouse? Many adults face multiple significant stresses at the same time. It is not uncommon for working parents to be in “soldiering on” mode, just surviving. But this takes a toll on being present and engaged with the children, and puts them at risk for depression and substance abuse.

Traumatic stress

Have they recently experienced a crime or accident, the unexpected loss of a loved one, or threats or abuse at home? They may be grieving, or may be experiencing symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder that lead them to appear distant and detached. Grief will improve with time, but they may benefit from extra support or from assistance with their responsibilities (a leave from work or more child care). If they have experienced a traumatic stress, they will need a clinical evaluation for potential treatment options. If they are being threatened or abused at home, you need to find out if their children have witnessed the abuse or may be victims as well. You can offer these parents resources for survivors of domestic abuse and speak with them about your obligation to file with your state’s agency responsible for children’s welfare. It is critical that you listen to any concerns they may have about this filing, from losing their children to enraging their abusers.

A detached parent may make a child feel worried, worthless, or guilty. There is no substitute for a loving, engaged parent, and your brief interventions to help a parent reconnect with the child will be invaluable.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected]

While most of the parents you will see in your office will be thoughtful, engaged, and even anxious, occasionally you will encounter parents who seem detached from their children. Spending just a few extra minutes to understand this detachment could mean an enormous difference in the psychological health and developmental well-being of your patient.

It is striking when you see it: Flat affect, little eye contact, no questions or comments. If the parents seem unconnected to their children, it is worth being curious about it. Whether they are constantly on their phones or just disengaged, you should start by directing a question straight to them. Perhaps a question about the child’s sleep, appetite, or school performance is a good place to start. You would like to assess their knowledge of the child’s development, performance at school, friendships, and interests, to ensure that they are up to date and paying attention.

Once alone, you might start by offering your impression of how the child is doing, then observe that you noticed that they (the parents) seem quiet or distant. The following questions should help you better understand the nature of their detachment.

Depression

Ask about how they are sleeping. If the child is very young or the parents have a difficult work schedule, they might simply be sleep deprived, which you might help them address. Difficulty sleeping also can be a symptom of depression. Have they noticed any changes in their appetite or energy? Is it harder to concentrate? Have they felt more tearful, sad, or irritable? Have they noticed that they don’t get as much pleasure from things that usually bring them joy? Do they worry about being a burden to others? Major depressive disorder is relatively common, affecting as many as one in five women in the postpartum period and one in ten women generally.

Men experience depression at about half that rate, according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is a condition that can cause feelings of guilt and shame, so many suffer silently, missing the chance for treatment and raising the risk for suicide. Infants of depressed mothers often appear listless and may be fussier about sleeping and eating, which can exacerbate poor attachment with their parents, and lead to problems in later years, including anxiety, mood, or behavioral problems. A parent’s depression, particularly in the postpartum period, represents a serious threat to the child’s healthy development and well-being.

Tell the parents that what they have described to you sounds like it could be a depressive episode and that depression has a serious impact on the whole family. Offer that their primary care physicians can evaluate and treat depression, or learn about other resources in your community that you can refer them to for accessible care.

Overwhelming stress

Is the newborn or special needs child feeling like more responsibility than the parents can handle? Where do the parents find support? Has there been a recent job loss or has there been a financial setback for the family? Is a spouse ill, or are they also caring for an aging parent? Has there been a separation from the spouse? Many adults face multiple significant stresses at the same time. It is not uncommon for working parents to be in “soldiering on” mode, just surviving. But this takes a toll on being present and engaged with the children, and puts them at risk for depression and substance abuse.

Traumatic stress

Have they recently experienced a crime or accident, the unexpected loss of a loved one, or threats or abuse at home? They may be grieving, or may be experiencing symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder that lead them to appear distant and detached. Grief will improve with time, but they may benefit from extra support or from assistance with their responsibilities (a leave from work or more child care). If they have experienced a traumatic stress, they will need a clinical evaluation for potential treatment options. If they are being threatened or abused at home, you need to find out if their children have witnessed the abuse or may be victims as well. You can offer these parents resources for survivors of domestic abuse and speak with them about your obligation to file with your state’s agency responsible for children’s welfare. It is critical that you listen to any concerns they may have about this filing, from losing their children to enraging their abusers.

A detached parent may make a child feel worried, worthless, or guilty. There is no substitute for a loving, engaged parent, and your brief interventions to help a parent reconnect with the child will be invaluable.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected]

While most of the parents you will see in your office will be thoughtful, engaged, and even anxious, occasionally you will encounter parents who seem detached from their children. Spending just a few extra minutes to understand this detachment could mean an enormous difference in the psychological health and developmental well-being of your patient.

It is striking when you see it: Flat affect, little eye contact, no questions or comments. If the parents seem unconnected to their children, it is worth being curious about it. Whether they are constantly on their phones or just disengaged, you should start by directing a question straight to them. Perhaps a question about the child’s sleep, appetite, or school performance is a good place to start. You would like to assess their knowledge of the child’s development, performance at school, friendships, and interests, to ensure that they are up to date and paying attention.

Once alone, you might start by offering your impression of how the child is doing, then observe that you noticed that they (the parents) seem quiet or distant. The following questions should help you better understand the nature of their detachment.

Depression

Ask about how they are sleeping. If the child is very young or the parents have a difficult work schedule, they might simply be sleep deprived, which you might help them address. Difficulty sleeping also can be a symptom of depression. Have they noticed any changes in their appetite or energy? Is it harder to concentrate? Have they felt more tearful, sad, or irritable? Have they noticed that they don’t get as much pleasure from things that usually bring them joy? Do they worry about being a burden to others? Major depressive disorder is relatively common, affecting as many as one in five women in the postpartum period and one in ten women generally.

Men experience depression at about half that rate, according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is a condition that can cause feelings of guilt and shame, so many suffer silently, missing the chance for treatment and raising the risk for suicide. Infants of depressed mothers often appear listless and may be fussier about sleeping and eating, which can exacerbate poor attachment with their parents, and lead to problems in later years, including anxiety, mood, or behavioral problems. A parent’s depression, particularly in the postpartum period, represents a serious threat to the child’s healthy development and well-being.

Tell the parents that what they have described to you sounds like it could be a depressive episode and that depression has a serious impact on the whole family. Offer that their primary care physicians can evaluate and treat depression, or learn about other resources in your community that you can refer them to for accessible care.

Overwhelming stress

Is the newborn or special needs child feeling like more responsibility than the parents can handle? Where do the parents find support? Has there been a recent job loss or has there been a financial setback for the family? Is a spouse ill, or are they also caring for an aging parent? Has there been a separation from the spouse? Many adults face multiple significant stresses at the same time. It is not uncommon for working parents to be in “soldiering on” mode, just surviving. But this takes a toll on being present and engaged with the children, and puts them at risk for depression and substance abuse.

Traumatic stress

Have they recently experienced a crime or accident, the unexpected loss of a loved one, or threats or abuse at home? They may be grieving, or may be experiencing symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder that lead them to appear distant and detached. Grief will improve with time, but they may benefit from extra support or from assistance with their responsibilities (a leave from work or more child care). If they have experienced a traumatic stress, they will need a clinical evaluation for potential treatment options. If they are being threatened or abused at home, you need to find out if their children have witnessed the abuse or may be victims as well. You can offer these parents resources for survivors of domestic abuse and speak with them about your obligation to file with your state’s agency responsible for children’s welfare. It is critical that you listen to any concerns they may have about this filing, from losing their children to enraging their abusers.

A detached parent may make a child feel worried, worthless, or guilty. There is no substitute for a loving, engaged parent, and your brief interventions to help a parent reconnect with the child will be invaluable.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected]

Under his IDH2: Epigenetic drivers of clonal hematopoiesis

The world has surely changed in recent years, leading television and Hollywood to recreate many former works of postapocalyptic fiction. Watching the recent Hulu drama “The Handmaid’s Tale” leads many to make modern-day comparisons, but to this hematologist the connection is bone deep.

Hematopoietic stem cells face a century of carefully regulated symmetric division. They are tasked with the mission to generate the heterogeneous and environmentally responsive progenitor populations that will undergo coordinated differentiation and maturation.1

Within this epic battle of Gilead, much like hematopoiesis, there is a hierarchy within the Sons of Jacob. At the top there are few who drive leukemogenicity and require no other co-conspirators. MLL fusions and core binding factor are the Commanders that can overthrow the regulated governance of normal marrow homeostasis. Other myeloid disease alleles are soldiers of Gilead (i.e. FLT3-ITD, IDH1, IDH2, NPM1c, Spliceosome/Cohesin). Their individual characteristics can influence the natural history of the disease and define its strengths and weaknesses, particularly as new targeted therapies are developed.

Recently, Jongen-Lavrencic et al. reported that all disease alleles that persist as minimal residual disease after induction have a negative influence on outcome, except for three – DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1.2 What do we make of the “DTA” mutations? Are they the “Eye” – spies embedded in the polyclonal background of the marrow – intrinsically wired with malevolent intent? Are they the innocent, abused Handmaids – reprogrammed by inflammatory “Aunts” at the marrow’s Red Center and forced to clonally procreate? Previous works have suggested the latter, that persistence of mutations in genes found in clonal hematopoiesis (CH) do not portend an equivalent risk of relapse.3,4

A more encompassing question remains as to the equivalency of CH in the absence of a hematopoietic tumor versus CH postleukemia therapy. Comparisons to small cell lymphomas after successful treatment of transformed disease are disingenuous; CH is not itself a malignant state.5 Forty months of median follow-up for post-AML CH is simply not enough time. Work presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology by Jaiswal et al. showed that the approximately 1% risk of transformation per year was consistent over a 20-year period of follow up in the Swedish Nurse’s Study.

The recent work in the New England Journal of Medicine adds to the growing understanding of CH, but requires the test of time to know if these cells are truly innocent Handmaids or the Eye in a red cloak. I’ll be exploring these issues and taking your questions during a live Twitter Q&A on June 14 at noon ET. Follow me at @TheDoctorIsVin and @HematologyNews1 for more details. Blessed be the fruit.

Dr. Viny is with the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, N.Y., where he is a clinical instructor, is on the staff of the leukemia service, and is a clinical researcher in the Ross Levine Lab.

References

1. Orkin SH and Zon L. Cell. 2008 Feb 22;132(4):631-44.

2. Jongen-Lavrencic M et al. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:1189-99.

3. Bhatnagar B et al. Br J Haematol. 2016 Oct;175(2):226-36.

4. Shlush LI et al. Nature. 2017;547:104-8.

5. Bowman RL et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2018 Feb 1;22(2):157-70.

The world has surely changed in recent years, leading television and Hollywood to recreate many former works of postapocalyptic fiction. Watching the recent Hulu drama “The Handmaid’s Tale” leads many to make modern-day comparisons, but to this hematologist the connection is bone deep.

Hematopoietic stem cells face a century of carefully regulated symmetric division. They are tasked with the mission to generate the heterogeneous and environmentally responsive progenitor populations that will undergo coordinated differentiation and maturation.1

Within this epic battle of Gilead, much like hematopoiesis, there is a hierarchy within the Sons of Jacob. At the top there are few who drive leukemogenicity and require no other co-conspirators. MLL fusions and core binding factor are the Commanders that can overthrow the regulated governance of normal marrow homeostasis. Other myeloid disease alleles are soldiers of Gilead (i.e. FLT3-ITD, IDH1, IDH2, NPM1c, Spliceosome/Cohesin). Their individual characteristics can influence the natural history of the disease and define its strengths and weaknesses, particularly as new targeted therapies are developed.

Recently, Jongen-Lavrencic et al. reported that all disease alleles that persist as minimal residual disease after induction have a negative influence on outcome, except for three – DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1.2 What do we make of the “DTA” mutations? Are they the “Eye” – spies embedded in the polyclonal background of the marrow – intrinsically wired with malevolent intent? Are they the innocent, abused Handmaids – reprogrammed by inflammatory “Aunts” at the marrow’s Red Center and forced to clonally procreate? Previous works have suggested the latter, that persistence of mutations in genes found in clonal hematopoiesis (CH) do not portend an equivalent risk of relapse.3,4

A more encompassing question remains as to the equivalency of CH in the absence of a hematopoietic tumor versus CH postleukemia therapy. Comparisons to small cell lymphomas after successful treatment of transformed disease are disingenuous; CH is not itself a malignant state.5 Forty months of median follow-up for post-AML CH is simply not enough time. Work presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology by Jaiswal et al. showed that the approximately 1% risk of transformation per year was consistent over a 20-year period of follow up in the Swedish Nurse’s Study.

The recent work in the New England Journal of Medicine adds to the growing understanding of CH, but requires the test of time to know if these cells are truly innocent Handmaids or the Eye in a red cloak. I’ll be exploring these issues and taking your questions during a live Twitter Q&A on June 14 at noon ET. Follow me at @TheDoctorIsVin and @HematologyNews1 for more details. Blessed be the fruit.

Dr. Viny is with the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, N.Y., where he is a clinical instructor, is on the staff of the leukemia service, and is a clinical researcher in the Ross Levine Lab.

References

1. Orkin SH and Zon L. Cell. 2008 Feb 22;132(4):631-44.

2. Jongen-Lavrencic M et al. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:1189-99.

3. Bhatnagar B et al. Br J Haematol. 2016 Oct;175(2):226-36.

4. Shlush LI et al. Nature. 2017;547:104-8.

5. Bowman RL et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2018 Feb 1;22(2):157-70.

The world has surely changed in recent years, leading television and Hollywood to recreate many former works of postapocalyptic fiction. Watching the recent Hulu drama “The Handmaid’s Tale” leads many to make modern-day comparisons, but to this hematologist the connection is bone deep.

Hematopoietic stem cells face a century of carefully regulated symmetric division. They are tasked with the mission to generate the heterogeneous and environmentally responsive progenitor populations that will undergo coordinated differentiation and maturation.1

Within this epic battle of Gilead, much like hematopoiesis, there is a hierarchy within the Sons of Jacob. At the top there are few who drive leukemogenicity and require no other co-conspirators. MLL fusions and core binding factor are the Commanders that can overthrow the regulated governance of normal marrow homeostasis. Other myeloid disease alleles are soldiers of Gilead (i.e. FLT3-ITD, IDH1, IDH2, NPM1c, Spliceosome/Cohesin). Their individual characteristics can influence the natural history of the disease and define its strengths and weaknesses, particularly as new targeted therapies are developed.

Recently, Jongen-Lavrencic et al. reported that all disease alleles that persist as minimal residual disease after induction have a negative influence on outcome, except for three – DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1.2 What do we make of the “DTA” mutations? Are they the “Eye” – spies embedded in the polyclonal background of the marrow – intrinsically wired with malevolent intent? Are they the innocent, abused Handmaids – reprogrammed by inflammatory “Aunts” at the marrow’s Red Center and forced to clonally procreate? Previous works have suggested the latter, that persistence of mutations in genes found in clonal hematopoiesis (CH) do not portend an equivalent risk of relapse.3,4

A more encompassing question remains as to the equivalency of CH in the absence of a hematopoietic tumor versus CH postleukemia therapy. Comparisons to small cell lymphomas after successful treatment of transformed disease are disingenuous; CH is not itself a malignant state.5 Forty months of median follow-up for post-AML CH is simply not enough time. Work presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology by Jaiswal et al. showed that the approximately 1% risk of transformation per year was consistent over a 20-year period of follow up in the Swedish Nurse’s Study.

The recent work in the New England Journal of Medicine adds to the growing understanding of CH, but requires the test of time to know if these cells are truly innocent Handmaids or the Eye in a red cloak. I’ll be exploring these issues and taking your questions during a live Twitter Q&A on June 14 at noon ET. Follow me at @TheDoctorIsVin and @HematologyNews1 for more details. Blessed be the fruit.

Dr. Viny is with the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, N.Y., where he is a clinical instructor, is on the staff of the leukemia service, and is a clinical researcher in the Ross Levine Lab.

References

1. Orkin SH and Zon L. Cell. 2008 Feb 22;132(4):631-44.

2. Jongen-Lavrencic M et al. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:1189-99.

3. Bhatnagar B et al. Br J Haematol. 2016 Oct;175(2):226-36.

4. Shlush LI et al. Nature. 2017;547:104-8.

5. Bowman RL et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2018 Feb 1;22(2):157-70.

Kawasaki disease: New info to enhance our index of suspicion

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

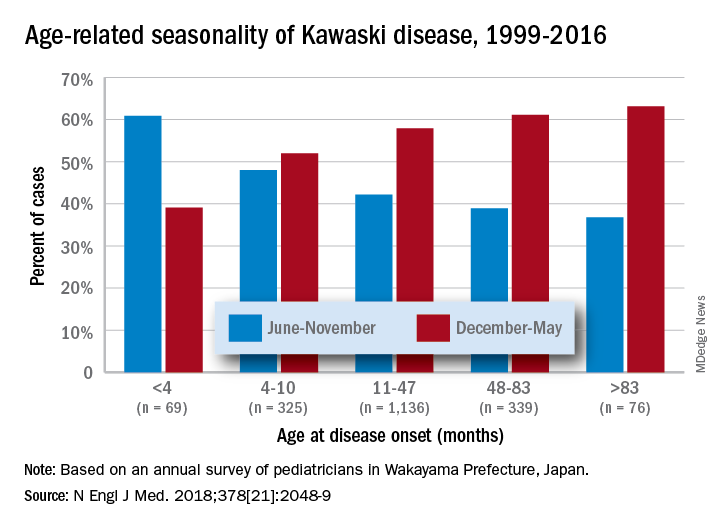

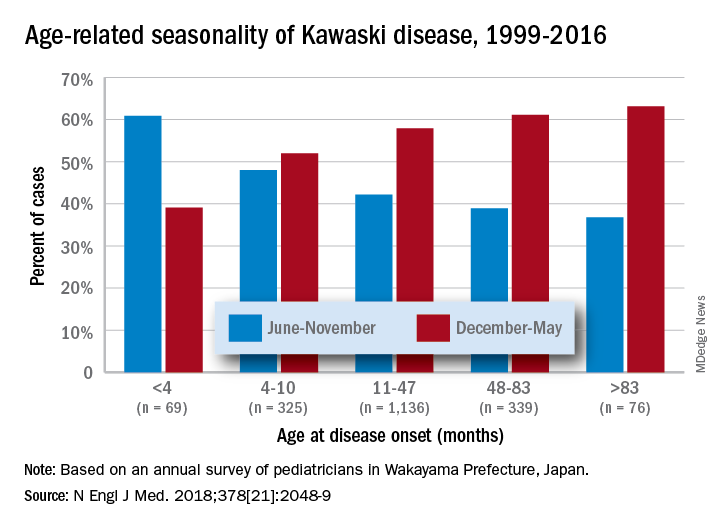

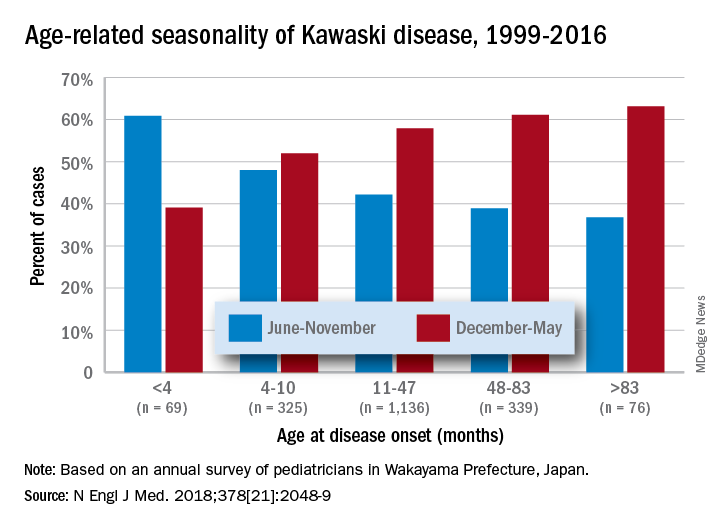

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Practice management pearls: Advice from seasoned doctors for residents looking to start a practice

The notion that residency training falls short when it comes to preparing residents and doctors for starting their own practice is a common thread across the board, whether you’re just getting started or have been managing your own practice for years. I did a survey on LinkedIn and over 50 dermatology and plastic surgery colleagues generously provided their own personal insights and words of wisdom to help young doctors avoid common practice management problems.

I could not quote everyone, but here are some of the best tips that I received:

Choose your staff carefully – and invest in the right candidates

One of the biggest pieces of practice management advice that doctors had to offer was to hire the right employees from the beginning, even if that means spending a little more time in the hiring process. This will eliminate headaches and frustration later.

In his own practice in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla., Dr. Lickstein has chosen a stable group of staff members who are, “first and foremost, nice, compassionate, and mature,” he said. “They need to be able to relate to cosmetic and medical patients of all ages. My office manager screens them, and then we have potential candidates shadow us for at least a half-day in the office. Afterward, we seek feedback from the current staff. I also try and talk with the candidate for a while, because I’ve found that once you get them to loosen up, you can get an actual sense of how they really are.”

Along the same lines, Cincinnati plastic surgeon Alex Donath, MD, suggests incentivizing employees and giving them an active role in the hiring process. “Give everyone in the office a chance to meet new employee candidates,” he said, “as that will both give the employees a sense of involvement in the process and allow more opportunities to catch glimpses of poor interpersonal skills that could hurt your reputation.”

Many doctors stressed the importance of the interview process, detailed job descriptions, a 60-day trial period, and background checks prior to hiring. This advice goes along with the famous quote “Be slow to hire and quick to fire (in the first 60 days)” that I have seen in many business books.

Foster teamwork

Another important aspect of managing your practice is building a sense of teamwork and camaraderie among employees and other doctors. Sean Weiss, MD, a facial plastic surgeon in New Orleans, has a great team-building tip that he uses daily.

“I plan a daily morning huddle with my staff. During the huddle, we review the prior day’s performance, those patients that need following up on, and whether or not the prior day’s goals were met. We then review the patient list for the current day to identify patient needs. We look specifically for ways to improve efficiency and avoid slowing down the work flow. We also try to identify opportunities to cross-promote our offerings to increase awareness of our services. In about 10 minutes, the entire team becomes focused and ready for a productive day.”

For Lacey Elwyn, DO, making staff feel appreciated can be as simple as telling them thank you on a regular basis. “The success of a dermatology practice encompasses every staff member of the team,” Dr. Elwyn, a medical and cosmetic dermatologist in South Florida, said. “The physician should respect and value all staff members. Tell them when they are doing a great job and tell them that you appreciate them every day, but also let them know right away when something is wrong.”

Don’t forget about patient education

Janet Trowbridge, MD, PhD, who practices in Edmond, Wash., expressed a great point that not only do patients need to be educated about their medical or cosmetic concerns, but they also need to be educated about the way that health care works in general. “I would say that 50% of my time as a physician is spent educating patients not about their disease, but about how medicine works – or doesn’t work,” she said. “I am constantly amazed by how little the average person understands about how health care is delivered. I talk about copays, coinsurance, annual deductibles, and why their prescriptions are not being covered. Patients feel that the system has let them down.”

Play the dual role of doctor and businessperson

At the end of the day, if you are managing your own practice, you must be able to split your time and skill set between being a physician and being a businessperson. Having realized the importance of the business aspect of running a practice, Justin Bryant, DO, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon in Walled Lake, Mich., enrolled in a dual-degree program during medical school in order to obtain his MBA.

“That investment already has proven priceless, as I’ve helped attendings and colleagues with their practice in marketing, finance, technology, and simply in translating business terms and contracts with physicians,” he said. “Although I don’t think it’s necessary for all physicians to pursue an MBA, and it’s not the answer to every business problem in the field of medicine, when applied, it can be very powerful!”

Build and protect your online reputation

Now more than ever, it is imperative to build and protect your online reputation, as online reviews can make or break your business. For plastic surgeon Nirmal Nathan, MD, in Plantation, Fla., managing your reputation is one of the most important considerations when starting a practice. “I would tell residents to start early on reputation management,” he said. “Reviews are so important, even with patients referred by word of mouth. Good reputation management also allows you to quickly ramp up if you decide to move your practice location.”

A large portion of building your online reputation now as to do with what you post (and don’t post) on social media. For Haena Kim, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon practicing in Walnut Creek, Calif., figuring out how you would like others to perceive you is the first step.

“In this day and age of social media,” she said, “it’s so hard not to feel the pressure to follow the crowd and be the loudest person out there, and it’s incredibly hard to be patient with your practice growth. It’s important to figure out how you want to present yourself and what you want patients to come away with.”

Sweat the small stuff

Seemingly small administrative and business-related tasks can quickly add up and create much larger problems if not addressed early on. Tito Vasquez, MD, who practices in Southport, Conn., summed this up with an excellent piece of advice to remember: “Sweat the small stuff now, so you don’t have to sweat over the big stuff later.”

In terms of the “small stuff” you’ll need to manage, Dr. Vasquez points to items such as learning local economics and politics, daily finances, office regulations, and documentation, investment and planning, internal and external marketing, and human resources. “While most of us would view this as mundane or at least secondary to the craft we learn,” he said, “it will actually take far greater importance to taking care of patients if you really want your business to succeed and thrive.”

Another essential aspect of business planning that may seem daunting or mundane to many doctors when first starting out is putting together the necessary training manuals to effectively run your practice. Robert Bader, MD, stressed the importance of creating manuals for the front office, back office, Material Safety Data Sheets, and Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

“This is the time, while you have some extra time, to take an active role in forming the foundation of your practice,” Dr. Bader of Deerfield Beach, Fla., said. “Set aside time every year to go over and make necessary changes to these manuals.”

Make decisions now that reflect long-term goals

When you start your practice, deciding on a location might seem like a secondary detail, but the fact of the matter is that location will ultimately play a large role in the future of your business and your life. Beverly Hills, Calif., plastic surgeon John Layke, DO, suggested “choosing where you would like to live, and then building a practice around that location. Being happy in the area you live will make a big difference,” he says. “No one will ultimately be happy making $1 million-plus per year if they are miserable living in the area. In the beginning, share office space with reputable people where you become ‘visible,’ then build the office of your dreams when you are ready.”

Summary

I was amazed at the number of responses that I received in response to this survey. It is my goal to help doctors mentor each other on these important issues so that we do not all have to recreate the wheel. Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to participate in these surveys or if you want to see the results of them. I want to wish the residents who are graduating and going into their own practice the best of luck. My final advice is to reach out for help – it’s obvious that many people are willing to provide advice.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. She is the author of the monthly “Cosmeceutical Critique” column in Dermatology News.

The notion that residency training falls short when it comes to preparing residents and doctors for starting their own practice is a common thread across the board, whether you’re just getting started or have been managing your own practice for years. I did a survey on LinkedIn and over 50 dermatology and plastic surgery colleagues generously provided their own personal insights and words of wisdom to help young doctors avoid common practice management problems.

I could not quote everyone, but here are some of the best tips that I received:

Choose your staff carefully – and invest in the right candidates

One of the biggest pieces of practice management advice that doctors had to offer was to hire the right employees from the beginning, even if that means spending a little more time in the hiring process. This will eliminate headaches and frustration later.

In his own practice in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla., Dr. Lickstein has chosen a stable group of staff members who are, “first and foremost, nice, compassionate, and mature,” he said. “They need to be able to relate to cosmetic and medical patients of all ages. My office manager screens them, and then we have potential candidates shadow us for at least a half-day in the office. Afterward, we seek feedback from the current staff. I also try and talk with the candidate for a while, because I’ve found that once you get them to loosen up, you can get an actual sense of how they really are.”

Along the same lines, Cincinnati plastic surgeon Alex Donath, MD, suggests incentivizing employees and giving them an active role in the hiring process. “Give everyone in the office a chance to meet new employee candidates,” he said, “as that will both give the employees a sense of involvement in the process and allow more opportunities to catch glimpses of poor interpersonal skills that could hurt your reputation.”

Many doctors stressed the importance of the interview process, detailed job descriptions, a 60-day trial period, and background checks prior to hiring. This advice goes along with the famous quote “Be slow to hire and quick to fire (in the first 60 days)” that I have seen in many business books.

Foster teamwork

Another important aspect of managing your practice is building a sense of teamwork and camaraderie among employees and other doctors. Sean Weiss, MD, a facial plastic surgeon in New Orleans, has a great team-building tip that he uses daily.

“I plan a daily morning huddle with my staff. During the huddle, we review the prior day’s performance, those patients that need following up on, and whether or not the prior day’s goals were met. We then review the patient list for the current day to identify patient needs. We look specifically for ways to improve efficiency and avoid slowing down the work flow. We also try to identify opportunities to cross-promote our offerings to increase awareness of our services. In about 10 minutes, the entire team becomes focused and ready for a productive day.”

For Lacey Elwyn, DO, making staff feel appreciated can be as simple as telling them thank you on a regular basis. “The success of a dermatology practice encompasses every staff member of the team,” Dr. Elwyn, a medical and cosmetic dermatologist in South Florida, said. “The physician should respect and value all staff members. Tell them when they are doing a great job and tell them that you appreciate them every day, but also let them know right away when something is wrong.”

Don’t forget about patient education

Janet Trowbridge, MD, PhD, who practices in Edmond, Wash., expressed a great point that not only do patients need to be educated about their medical or cosmetic concerns, but they also need to be educated about the way that health care works in general. “I would say that 50% of my time as a physician is spent educating patients not about their disease, but about how medicine works – or doesn’t work,” she said. “I am constantly amazed by how little the average person understands about how health care is delivered. I talk about copays, coinsurance, annual deductibles, and why their prescriptions are not being covered. Patients feel that the system has let them down.”

Play the dual role of doctor and businessperson

At the end of the day, if you are managing your own practice, you must be able to split your time and skill set between being a physician and being a businessperson. Having realized the importance of the business aspect of running a practice, Justin Bryant, DO, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon in Walled Lake, Mich., enrolled in a dual-degree program during medical school in order to obtain his MBA.

“That investment already has proven priceless, as I’ve helped attendings and colleagues with their practice in marketing, finance, technology, and simply in translating business terms and contracts with physicians,” he said. “Although I don’t think it’s necessary for all physicians to pursue an MBA, and it’s not the answer to every business problem in the field of medicine, when applied, it can be very powerful!”

Build and protect your online reputation

Now more than ever, it is imperative to build and protect your online reputation, as online reviews can make or break your business. For plastic surgeon Nirmal Nathan, MD, in Plantation, Fla., managing your reputation is one of the most important considerations when starting a practice. “I would tell residents to start early on reputation management,” he said. “Reviews are so important, even with patients referred by word of mouth. Good reputation management also allows you to quickly ramp up if you decide to move your practice location.”

A large portion of building your online reputation now as to do with what you post (and don’t post) on social media. For Haena Kim, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon practicing in Walnut Creek, Calif., figuring out how you would like others to perceive you is the first step.

“In this day and age of social media,” she said, “it’s so hard not to feel the pressure to follow the crowd and be the loudest person out there, and it’s incredibly hard to be patient with your practice growth. It’s important to figure out how you want to present yourself and what you want patients to come away with.”

Sweat the small stuff

Seemingly small administrative and business-related tasks can quickly add up and create much larger problems if not addressed early on. Tito Vasquez, MD, who practices in Southport, Conn., summed this up with an excellent piece of advice to remember: “Sweat the small stuff now, so you don’t have to sweat over the big stuff later.”

In terms of the “small stuff” you’ll need to manage, Dr. Vasquez points to items such as learning local economics and politics, daily finances, office regulations, and documentation, investment and planning, internal and external marketing, and human resources. “While most of us would view this as mundane or at least secondary to the craft we learn,” he said, “it will actually take far greater importance to taking care of patients if you really want your business to succeed and thrive.”

Another essential aspect of business planning that may seem daunting or mundane to many doctors when first starting out is putting together the necessary training manuals to effectively run your practice. Robert Bader, MD, stressed the importance of creating manuals for the front office, back office, Material Safety Data Sheets, and Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

“This is the time, while you have some extra time, to take an active role in forming the foundation of your practice,” Dr. Bader of Deerfield Beach, Fla., said. “Set aside time every year to go over and make necessary changes to these manuals.”

Make decisions now that reflect long-term goals

When you start your practice, deciding on a location might seem like a secondary detail, but the fact of the matter is that location will ultimately play a large role in the future of your business and your life. Beverly Hills, Calif., plastic surgeon John Layke, DO, suggested “choosing where you would like to live, and then building a practice around that location. Being happy in the area you live will make a big difference,” he says. “No one will ultimately be happy making $1 million-plus per year if they are miserable living in the area. In the beginning, share office space with reputable people where you become ‘visible,’ then build the office of your dreams when you are ready.”

Summary

I was amazed at the number of responses that I received in response to this survey. It is my goal to help doctors mentor each other on these important issues so that we do not all have to recreate the wheel. Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to participate in these surveys or if you want to see the results of them. I want to wish the residents who are graduating and going into their own practice the best of luck. My final advice is to reach out for help – it’s obvious that many people are willing to provide advice.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. She is the author of the monthly “Cosmeceutical Critique” column in Dermatology News.

The notion that residency training falls short when it comes to preparing residents and doctors for starting their own practice is a common thread across the board, whether you’re just getting started or have been managing your own practice for years. I did a survey on LinkedIn and over 50 dermatology and plastic surgery colleagues generously provided their own personal insights and words of wisdom to help young doctors avoid common practice management problems.

I could not quote everyone, but here are some of the best tips that I received:

Choose your staff carefully – and invest in the right candidates

One of the biggest pieces of practice management advice that doctors had to offer was to hire the right employees from the beginning, even if that means spending a little more time in the hiring process. This will eliminate headaches and frustration later.

In his own practice in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla., Dr. Lickstein has chosen a stable group of staff members who are, “first and foremost, nice, compassionate, and mature,” he said. “They need to be able to relate to cosmetic and medical patients of all ages. My office manager screens them, and then we have potential candidates shadow us for at least a half-day in the office. Afterward, we seek feedback from the current staff. I also try and talk with the candidate for a while, because I’ve found that once you get them to loosen up, you can get an actual sense of how they really are.”

Along the same lines, Cincinnati plastic surgeon Alex Donath, MD, suggests incentivizing employees and giving them an active role in the hiring process. “Give everyone in the office a chance to meet new employee candidates,” he said, “as that will both give the employees a sense of involvement in the process and allow more opportunities to catch glimpses of poor interpersonal skills that could hurt your reputation.”

Many doctors stressed the importance of the interview process, detailed job descriptions, a 60-day trial period, and background checks prior to hiring. This advice goes along with the famous quote “Be slow to hire and quick to fire (in the first 60 days)” that I have seen in many business books.

Foster teamwork

Another important aspect of managing your practice is building a sense of teamwork and camaraderie among employees and other doctors. Sean Weiss, MD, a facial plastic surgeon in New Orleans, has a great team-building tip that he uses daily.

“I plan a daily morning huddle with my staff. During the huddle, we review the prior day’s performance, those patients that need following up on, and whether or not the prior day’s goals were met. We then review the patient list for the current day to identify patient needs. We look specifically for ways to improve efficiency and avoid slowing down the work flow. We also try to identify opportunities to cross-promote our offerings to increase awareness of our services. In about 10 minutes, the entire team becomes focused and ready for a productive day.”

For Lacey Elwyn, DO, making staff feel appreciated can be as simple as telling them thank you on a regular basis. “The success of a dermatology practice encompasses every staff member of the team,” Dr. Elwyn, a medical and cosmetic dermatologist in South Florida, said. “The physician should respect and value all staff members. Tell them when they are doing a great job and tell them that you appreciate them every day, but also let them know right away when something is wrong.”

Don’t forget about patient education

Janet Trowbridge, MD, PhD, who practices in Edmond, Wash., expressed a great point that not only do patients need to be educated about their medical or cosmetic concerns, but they also need to be educated about the way that health care works in general. “I would say that 50% of my time as a physician is spent educating patients not about their disease, but about how medicine works – or doesn’t work,” she said. “I am constantly amazed by how little the average person understands about how health care is delivered. I talk about copays, coinsurance, annual deductibles, and why their prescriptions are not being covered. Patients feel that the system has let them down.”

Play the dual role of doctor and businessperson

At the end of the day, if you are managing your own practice, you must be able to split your time and skill set between being a physician and being a businessperson. Having realized the importance of the business aspect of running a practice, Justin Bryant, DO, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon in Walled Lake, Mich., enrolled in a dual-degree program during medical school in order to obtain his MBA.

“That investment already has proven priceless, as I’ve helped attendings and colleagues with their practice in marketing, finance, technology, and simply in translating business terms and contracts with physicians,” he said. “Although I don’t think it’s necessary for all physicians to pursue an MBA, and it’s not the answer to every business problem in the field of medicine, when applied, it can be very powerful!”

Build and protect your online reputation

Now more than ever, it is imperative to build and protect your online reputation, as online reviews can make or break your business. For plastic surgeon Nirmal Nathan, MD, in Plantation, Fla., managing your reputation is one of the most important considerations when starting a practice. “I would tell residents to start early on reputation management,” he said. “Reviews are so important, even with patients referred by word of mouth. Good reputation management also allows you to quickly ramp up if you decide to move your practice location.”

A large portion of building your online reputation now as to do with what you post (and don’t post) on social media. For Haena Kim, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon practicing in Walnut Creek, Calif., figuring out how you would like others to perceive you is the first step.

“In this day and age of social media,” she said, “it’s so hard not to feel the pressure to follow the crowd and be the loudest person out there, and it’s incredibly hard to be patient with your practice growth. It’s important to figure out how you want to present yourself and what you want patients to come away with.”

Sweat the small stuff

Seemingly small administrative and business-related tasks can quickly add up and create much larger problems if not addressed early on. Tito Vasquez, MD, who practices in Southport, Conn., summed this up with an excellent piece of advice to remember: “Sweat the small stuff now, so you don’t have to sweat over the big stuff later.”

In terms of the “small stuff” you’ll need to manage, Dr. Vasquez points to items such as learning local economics and politics, daily finances, office regulations, and documentation, investment and planning, internal and external marketing, and human resources. “While most of us would view this as mundane or at least secondary to the craft we learn,” he said, “it will actually take far greater importance to taking care of patients if you really want your business to succeed and thrive.”

Another essential aspect of business planning that may seem daunting or mundane to many doctors when first starting out is putting together the necessary training manuals to effectively run your practice. Robert Bader, MD, stressed the importance of creating manuals for the front office, back office, Material Safety Data Sheets, and Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

“This is the time, while you have some extra time, to take an active role in forming the foundation of your practice,” Dr. Bader of Deerfield Beach, Fla., said. “Set aside time every year to go over and make necessary changes to these manuals.”

Make decisions now that reflect long-term goals

When you start your practice, deciding on a location might seem like a secondary detail, but the fact of the matter is that location will ultimately play a large role in the future of your business and your life. Beverly Hills, Calif., plastic surgeon John Layke, DO, suggested “choosing where you would like to live, and then building a practice around that location. Being happy in the area you live will make a big difference,” he says. “No one will ultimately be happy making $1 million-plus per year if they are miserable living in the area. In the beginning, share office space with reputable people where you become ‘visible,’ then build the office of your dreams when you are ready.”

Summary

I was amazed at the number of responses that I received in response to this survey. It is my goal to help doctors mentor each other on these important issues so that we do not all have to recreate the wheel. Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to participate in these surveys or if you want to see the results of them. I want to wish the residents who are graduating and going into their own practice the best of luck. My final advice is to reach out for help – it’s obvious that many people are willing to provide advice.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. She is the author of the monthly “Cosmeceutical Critique” column in Dermatology News.

Emergency contraception ... and our duty to inform

In 2013, the emergency contraception containing levonorgestrel, most commonly known as Plan B, became available for purchase without prescription or age restriction. Yet, 5 years later, many adolescents and teens remain misinformed or uninformed completely. For the scope of this article, only levonorgestrel will be discussed, acknowledging that ulipristal acetate (Ella) is also an emergency contraception by prescription.

As providers we all recognize the challenges of engaging a teen patient long enough to have a meaningful conversation on health and wellness. There are even greater challenges when it comes to discussing sexual activity and sexually transmitted diseases. So the thought of discussing prevention of unwanted pregnancy may be daunting for most of us.

This topic has many layers. First and foremost, it touches on a hotly debated topic of where life begins, and emergency contraception may be thought to cross that line. Awareness of the option of emergency contraception is thought to give a free pass to promiscuous behavior. Some just feel there is not enough research to support the safe use of these products in adolescents. As with most things, taking the time to educate ourselves on the facts usually alleviates the conflicts.

Understanding levonorgestrel mechanism of action is important in clarifying its position in the prolife debate. The International Consortium for Emergency Contraception and the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetrics consider that inhibition or delay of ovulation is levonorgestrel’s mechanism of action, and that it does not prevent implantation of a fertilized egg. If taken after ovulation has occurred, it is ineffective in preventing pregnancy.1,2

Levonorgestrel emergency contraception was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1999 under the brand name Plan B by Teva Women’s Health, then later Next Choice (Watson Pharma) was released. Initially, it was prescribed to be taken as a 0.75-mg tab within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse and repeated in 12 hours. Further studies revealed taking a 1.5-mg tab once was just as effective with no significant increase in adverse effects and Plan B One-Step was released.3

The Catholic Health Association presented a paper clarifying that levonorgestrel is not a postfertilization contraceptive (abortifacient), hopefully preventing delay of its use in victims of sexual assault seen in Catholic health care facilities.4

Safety for this product since its release has shown no deaths or serious complications.2 The most common side effect is nausea, usually without vomiting.2 Antinausea medication given 1 hour before can be helpful but is not routinely used. The length of menstrual cycle is shorter if given early in cycle but it may be lengthened by 2 days if taken post ovulation. It is not intended for repeated use, but 11 studies showed no adverse effects when it was used repeatedly in the same ovulatory cycle, and it was shown to be safe.2

For women whose emergency contraception failed, one study of 332 pregnant women who had used levonorgestrel found no teratogenic effect or risk of birth defects.5 Although it is not contraindicated in breastfeeding mothers, it was recommended that patients discontinue breastfeeding for 8 hours post ingestion. Recognized contraindications to oral contraceptives do not apply to levonorgestrel, given the temporary and relative low exposure to the hormone.3

As for efficacy, timing is of the essence. As stated previously, if not taken before ovulation has occurred, it is ineffective. If taken within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, one study showed levonorgestrel would prevent 85% of pregnancies that otherwise might have occurred.3 Although the package insert says it must taken within 72 hours, studies have shown protection up to 120 hours post coitus, but that efficacy declines with every hour. Body mass index also may play a role in effectiveness, but the studies have been varied and more research is required before a determination is made.2

The annual well visit is the opportune time to educate parents and teens about abstinence, sex, sexually transmitted infections, and emergency contraception. Parents need to know the statistics of teen pregnancy and rates of STIs so they can be informed and further these conversations at home. should they find themselves in this dilemma. The websites not-2-late.com and bedsider.org are excellent sources of information on emergency contraception.

Keep in mind that 10% of all unintended pregnancies occur from nonconsensual intercourse so knowing what options are available is critical. Whether you give a handout with the information or undertake a more in-depth conversation during well visits, this is vital information that can change a person’s life.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. “Emergency Contraception: Questions And Answers For Decision-Makers,” International Consortium for Emergency Contraception, 2013.

2. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Dec;57(4):741-50.

3. Pediatrics 2012;130:1174-82.

4. Health Progress. 2010 Jan-Feb. 59-61.

5. Hum Reprod. 2009 Jul;24(7):1605-11.

6. Contraception. 2016 Feb;93(2):145-52.

In 2013, the emergency contraception containing levonorgestrel, most commonly known as Plan B, became available for purchase without prescription or age restriction. Yet, 5 years later, many adolescents and teens remain misinformed or uninformed completely. For the scope of this article, only levonorgestrel will be discussed, acknowledging that ulipristal acetate (Ella) is also an emergency contraception by prescription.

As providers we all recognize the challenges of engaging a teen patient long enough to have a meaningful conversation on health and wellness. There are even greater challenges when it comes to discussing sexual activity and sexually transmitted diseases. So the thought of discussing prevention of unwanted pregnancy may be daunting for most of us.

This topic has many layers. First and foremost, it touches on a hotly debated topic of where life begins, and emergency contraception may be thought to cross that line. Awareness of the option of emergency contraception is thought to give a free pass to promiscuous behavior. Some just feel there is not enough research to support the safe use of these products in adolescents. As with most things, taking the time to educate ourselves on the facts usually alleviates the conflicts.

Understanding levonorgestrel mechanism of action is important in clarifying its position in the prolife debate. The International Consortium for Emergency Contraception and the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetrics consider that inhibition or delay of ovulation is levonorgestrel’s mechanism of action, and that it does not prevent implantation of a fertilized egg. If taken after ovulation has occurred, it is ineffective in preventing pregnancy.1,2

Levonorgestrel emergency contraception was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1999 under the brand name Plan B by Teva Women’s Health, then later Next Choice (Watson Pharma) was released. Initially, it was prescribed to be taken as a 0.75-mg tab within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse and repeated in 12 hours. Further studies revealed taking a 1.5-mg tab once was just as effective with no significant increase in adverse effects and Plan B One-Step was released.3

The Catholic Health Association presented a paper clarifying that levonorgestrel is not a postfertilization contraceptive (abortifacient), hopefully preventing delay of its use in victims of sexual assault seen in Catholic health care facilities.4

Safety for this product since its release has shown no deaths or serious complications.2 The most common side effect is nausea, usually without vomiting.2 Antinausea medication given 1 hour before can be helpful but is not routinely used. The length of menstrual cycle is shorter if given early in cycle but it may be lengthened by 2 days if taken post ovulation. It is not intended for repeated use, but 11 studies showed no adverse effects when it was used repeatedly in the same ovulatory cycle, and it was shown to be safe.2

For women whose emergency contraception failed, one study of 332 pregnant women who had used levonorgestrel found no teratogenic effect or risk of birth defects.5 Although it is not contraindicated in breastfeeding mothers, it was recommended that patients discontinue breastfeeding for 8 hours post ingestion. Recognized contraindications to oral contraceptives do not apply to levonorgestrel, given the temporary and relative low exposure to the hormone.3

As for efficacy, timing is of the essence. As stated previously, if not taken before ovulation has occurred, it is ineffective. If taken within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, one study showed levonorgestrel would prevent 85% of pregnancies that otherwise might have occurred.3 Although the package insert says it must taken within 72 hours, studies have shown protection up to 120 hours post coitus, but that efficacy declines with every hour. Body mass index also may play a role in effectiveness, but the studies have been varied and more research is required before a determination is made.2

The annual well visit is the opportune time to educate parents and teens about abstinence, sex, sexually transmitted infections, and emergency contraception. Parents need to know the statistics of teen pregnancy and rates of STIs so they can be informed and further these conversations at home. should they find themselves in this dilemma. The websites not-2-late.com and bedsider.org are excellent sources of information on emergency contraception.